Abstract

Location estimation is significant in this era of the Internet of Things (IoT). Satellite and cellular signals are often blocked indoors, prompting researchers to explore alternative wireless technologies for indoor positioning. Among these, Wi-Fi Received Signal Strength (RSS) with fingerprinting is dominant in large, multi-floor buildings due to its existing infrastructure, acceptable accuracy, low cost, easy deployment, and scalability. This study aims to systematically search and review the literature on the use of real Wi-Fi RSS fingerprints for indoor localization or positioning in large, multi-floor buildings, in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, to identify current trends, performance, and gaps. Our findings highlight three main public datasets in this fields (covering areas over 10,000 sq.m). Recent trends indicate the widespread adoption of Deep Learning (DL) techniques, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Stacked Autoencoders (SAEs). While buildings (in the same vicinity) and their respective floors are accurately identified, the maximum average error remains around 7 m. A notable gap is the lack of public datasets with detailed room or zone information. This review intends to serve as a guide for future researchers looking to improve indoor location estimation in large, multi-floor structures such as universities, hospitals, and malls.

1. Introduction

Location and context-based services are widespread in today’s digital age. The development of satellite and cellular positioning applications has revolutionized how we interact with the physical outdoor environment. However, factors such as non-line-of-sight, multipath, attenuation, blind spots, and interference block these satellite and cellular signals indoors, limiting their effectiveness. To tackle these issues, many wireless technologies and techniques are being explored for indoor location estimation, due to their significant market potential, which can be up to four times larger than outdoor [1]. Options include Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, Zigbee, Ultrawideband, LoRaWAN, RFID, ultrasound, and magnetic fields, while standard techniques include Time of Arrival, Angle of Arrival, Fingerprinting, Time Difference of Arrival, and Lateration. Currently, Wi-Fi Fingerprinting using Received Signal Strength (RSS) is the dominant approach in large buildings because it provides acceptable accuracy, pre-built infrastructure, low cost, easy deployment, and scalability [2]. The preference of RSS over Channel State Information (CSI), which yields higher accuracy due to more detailed data, mainly stems from RSS being more accessible on everyday Wi-Fi devices.

Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting, scene analysis, or radio mapping works in two main phases: the offline acquisition phase and the online positioning phase. During the offline phase, Wi-Fi RSS values from access points (APs) are systematically collected at designated known location reference points (RPs) within the area of interest to create a database, also known as a radio map. Then, during the online positioning phase, a Wi-Fi RSS receiving device, known as a tag, is placed at an unknown location to generate an RSS fingerprint for that specific spot. This fingerprint is then carefully matched with the existing database of location-RSS fingerprints. By matching the generated fingerprint with the database, accurate location information of the tag can be determined, allowing it to be precisely positioned within the target area.

Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting-based indoor localization faces several challenges, including multipath effects, device heterogeneity, and a lack of standardization [3]. Multipath arises from the reflection, refraction, and diffraction of Wi-Fi signals by various static and dynamic objects in indoor environments, causing significant RSS fluctuations and potential mismatches in location information during the online stage. Device heterogeneity, caused by differences in hardware from various Wi-Fi receiver manufacturers, results in different RSS values received by multiple devices from the same APs at identical locations and times. Additionally, the absence of standardization makes it difficult to compare different methodologies within the field. Most researchers conduct private experiments, which complicate the replication and comparison of results. Public datasets often lack detailed location information, making them less suitable for practical use. High-quality public datasets with a greater number of APs and RPs are crucial for achieving greater accuracy [4]. While standard datasets are frequently used in machine learning for effective comparison, their availability in the indoor localization domain remains limited.

Despite the challenges, Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting remains the primary method for indoor localization in large multi-floor buildings. This work reviews indoor localization solutions using Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting in large multi-floor buildings. The main contributions of this review are as follows: (i) identifying and summarizing articles related to Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting-based indoor localization in large multi-floor buildings (mainly areas over 10,000 sq.m) and (ii) discussing current trends, performance, and gaps in existing research.

2. Related Works

Indoor location systems (ILS), along with their working principles, applications, and challenges, are summarized in [5]. Techniques and technologies for IoT-based applications are prioritized in [6]. Authors in [6] divide techniques into range-based (geometric) and range-free (non-geometric). Technologies are classified based on frequency, ranging from mechanical (Hz) to MEMS, electrical, magnetic, acoustic, RF, and light (THz). Collaborative ILS (CILS), which is based on cooperation, is systematically reviewed in [7]. ILS using smartphone RF technology is discussed in [8]. While the ILS related to floor identification is reviewed in [9], ILS designed for multi-floor environments is surveyed in [10]. Combining smartphones and floor identification, Ref. [11] reviews techniques for smartphone-based floor positioning that go beyond RF technology alone, including sensors such as barometers embedded in modern smartphones. Refs. [10,11] classifies multi-floor environments based on their structure as either full-floor laminate or atrium spaces.

Wi-Fi is an RF technology operating in the GHz range. Fundamental concepts and the evolution of Wi-Fi-based ILS, along with some case studies, are discussed in [12]. Fingerprinting is a range-free (non-geometric) technique that has advantages over range-based approaches in non-line-of-sight conditions. A comprehensive review of deep learning (DL) methods in fingerprinting-based ILS is conducted in [3]. Wi-Fi fingerprinting is prevalent in multi-floor buildings, especially in full-floor laminate structures. An overview of Wi-Fi fingerprinting-based ILS, including general working principles and positioning algorithms, is presented in [2], while an introduction to Wi-Fi fingerprinting, covering performance metrics and recent trends, is provided in [1]. An in-depth review of Wi-Fi fingerprinting studies is offered, focusing on two main areas: advanced localization techniques and efficient system deployment [13]. Advanced localization methods utilize temporal or spatial signal patterns, user collaboration, and motion sensors, while efficient system deployment aims to reduce site survey effort, fluctuations, heterogeneity, and energy consumption. Although collaborative Wi-Fi fingerprinting-based ILS seems promising, it requires at least two devices in the vicinity and additional resources.

Wi-Fi fingerprinting solutions that do not require prior calibration, such as crowdsourcing and augmentation, are examined, comparing their performance against traditional and new performance criteria [14]. This approach supports efficient system deployment by reducing site survey efforts, as in [13]. A comprehensive review of deep learning (DL)-based Wi-Fi ILS, mainly fingerprinting, is presented in [15]. Commonly used DL models include CNNs, RNNs, and LSTMs. Additionally, a review of publicly available Wi-Fi fingerprinting datasets is given in [16], along with a survey of key DL methods employed in Wi-Fi fingerprinting in [17]. Wi-Fi signals encompass RSSI, CSI, RTT, and others, with RSSI being the most prevalent in Wi-Fi fingerprinting-based ILS. According to [16], nearly 95% of the reviewed datasets focus on Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting. An overview of machine learning (ML)- based ILS using Wi-Fi RSSI fingerprints is provided in [4]. While DL mainly involves feature extraction and positioning [17], ML encompasses preprocessing, augmentation, positioning, and post-processing [4]. Refs. [15,17] find CNN to be the most promising option. A survey addressing the main research challenges in implementing Wi-Fi-based ILS on smartphones, chiefly RSSI fingerprinting, is discussed in [18]. Unlike the studies mentioned, this review will concentrate on non-collaborative Wi-Fi fingerprinting-based ILS in multi-floor buildings. Mainly, large buildings with an experimental surface area exceeding 10,000 sq.m will be examined. Additionally, smartphone-based systems and full-floor laminate spaces will form the primary focus of the study.

3. Materials and Methods

This review is conducted following the guidelines outlined in [19]. A refined search matrix is developed to optimize the search process. The SCOPUS and IEEE Xplore databases are used to identify relevant publications. For the SCOPUS database, a search is performed in the article title, abstract, and keywords fields, using the following search string: (indoor OR in-door OR in-building W/2 location* OR localiz* OR localis* OR position* OR navigat* OR track* OR SLAM OR “simultaneous locali*”) AND (wifi OR wi-fi OR “wireless fidelity” OR “wireless fidelities” OR WLAN OR “wireless local area network*” OR “wi—fi” W/2 fingerprint* OR “scene analysis” OR map* OR “radio map*”) AND (building* W/1 floor OR multistory OR multistorey OR office OR university OR college). In contrast, for the IEEE Xplore database, search is conducted in all fields, using the search string: (“indoor” AND (“loca*” OR “position*” OR “navigat*” OR “track*”) AND (“wifi” OR “wi-fi”) AND “fingerprint*” AND “building”).

The selection of articles is based solely on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The first criterion considers the technology used. Articles using Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting met the inclusion criteria based on technology, while those using other technologies, such as Wi-Fi CSI, Bluetooth, Dead Reckoning, Geomagnetic, as well as those involving fusion with Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting, are excluded. The second criterion is related to the Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting dataset. Articles involving multi-floor buildings or large-scale structures (generally covering areas greater than 10,000 sq.m) met the inclusion criteria, whereas those involving small-scale environments and articles related to the fingerprint augmentation or artificial fingerprints are excluded. Finally, function is used as an inclusion criterion. Articles focusing on performance metric improvement, such as accuracy, localization time, and complexity, met the inclusion criteria, while articles related to security, safety, or privacy were excluded. These criteria were selected to focus on the performance of Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting in large, multi-floor buildings, so that other technologies, smaller areas and protective measures can be further investigated in the near future for enhancements while integrating them primarily with Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting.

4. Results

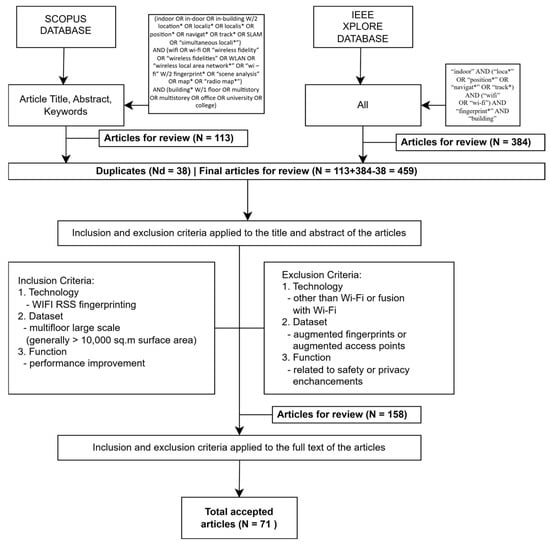

The search index yielded a total of 113 results from SCOPUS and 384 from IEEE Xplore. Out of 497 articles, 38 duplicates are identified and removed, leaving 459 articles for screening. These articles are then subjected to title and abstract screening using the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in 158 selected articles. The same criteria are applied to the full texts of these 158 articles, yielding 71 studies. Figure 1 illustrates the search and filtering strategy flow diagram. The reviewed papers can be broadly categorized into studies using private datasets only and studies utilizing public datasets either solely or on top of private datasets.

Figure 1.

Search and filtering strategy flow diagram.

Various evaluation metrics are used in the domain for measuring how well the indoor localization system performs, such as accuracy, position error, complexity, localization time, cost, scalability and robustness. Accuracy and position error (PE) are often used metrics for evaluation. Accuracy is defined as the number of correct predictions over the total number of predictions. Mainly, Building Accuracy (BA) and Floor Accuracy (FA) are used to indicate the number of correct predictions for the respective categories over the total. Although some studies have included room accuracy as well, due to limited studies with these metrics, we have limited our findings to BA and FA only. PE is defined as the Euclidean distance between the predicted coordinate and the actual ground truth coordinate. Some studies include localization time in milliseconds; however, due to the limitation of Wi-Fi scanning time (seconds), most studies focus on BA, FA, and PE.

4.1. Private Datasets

A particle filter, combined with pedestrians’ motion, previous location states such as floor, position, person’s heading, and movement, is used on a private dataset, achieving an error of around 1.8 m [20]. Unlike prior studies, which are mainly conducted on personal computers, experiments utilized smartphones, marking the early use of smartphones for indoor localization using Wi-Fi fingerprinting. However, the coverage is limited to a small area. The study primarily focuses on location estimation for navigation applications used by smartphone users. Logical errors, like indistinguishability from the opposite side of walls, are addressed by incorporating building interior structures through a graph and Bayesian approach, resulting in floor accuracy of up to 97% and a position error of about 2.89 m in a private dataset [21]. Experiments indicate reduced errors in higher frequency Wi-Fi bands (5 GHz signals performed better than 2.4 GHz) while increasing accuracy, especially with virtual access points (VAPs) [22]. K nearest neighbor (kNN) is employed for positioning in their private experiment, resulting in a position error of roughly 10 m. The authors note that, although researchers aim to develop an algorithm or framework capable of indoor localization, such a solution may not always exist, as different floors might require different algorithms or frameworks to achieve optimal accuracy. Long-term accuracy is examined through measurements taken at three-year intervals [23]. However, during this period, the university significantly upgraded its Wi-Fi access points (APs). The primary objective is to verify accuracy when the AP configuration is changed, with the indoor environment (building structure, rooms, and furniture layout) remaining constant. Their findings show complete failure in location estimation when the AP configuration is altered with new APs. Additionally, the authors suggested that accuracy declines over time and recommended ongoing updates to the fingerprinting database to sustain consistent accuracy levels. Similar to [22], they propose combining higher-frequency Wi-Fi bands and VAPs, along with frequent database updates, to enhance overall system performance. kNN applied to a private dataset achieves a floor accuracy of up to 100% and a 6 m position error.

Database correlation methods are applied to a private dataset of a 12-floor university building, attaining up to 84% floor accuracy and a maximum of 4.7 m in position error [24]. A detailed indoor localization ecosystem for an area of more than 450,000 sq.m is done, including designing, mapping, fingerprint collection, system setup, testing, and launching [25]. kWNN, along with other strategies, is used for classification on a private dataset, achieving an accuracy of up to 99.60% and a position error of up to 6 m. A decrease in accuracy over time is identified as the primary issue. Feedback from users shows that they are more tolerant of delays than incorrect location. Despite collecting updated fingerprints in the background while the app is used, accuracy severely declines in their case. Weighted centroid and fingerprint clustering, utilizing a k-means method, is employed for faster and simpler estimation, making them applicable to resource-constrained devices; however, these simple techniques trade off accuracy [26]. Their study on a private dataset shows floor accuracy up to 99.44%. The authors state that APs deployed in most buildings are not centralized; hence, their locations are not known in total. A thresholding strategy is used to lower complexity while achieving a high floor accuracy of 86% on a private dataset [27]. Although this work deviates from the recommended procedure in [28], it achieves good results by utilizing only 14% of the dataset. Their method involves constructing a new database using the database reduction technique, which selects only ‘significant’ APs. A hierarchical tree based on a real building’s structure and a private dataset is experimented with using double-weighted similarity-based neighbor classification, achieving 90% accuracy in room or zone identification and 2 m position error [29]. Stacked autoencoder (SAE) is used on a private dataset, achieving 85.58% zone accuracy with a test time of not more than 0.26 s [30]. An adaptive localization system for a large-scale multibuilding environment is tested on a private testbed covering 486,000 sq.m [31]. An AP miss detector and filter algorithm are implemented in the online phase to enhance overall system performance. Their experiments demonstrated 100% building and floor level accuracy, with an average position error of 0.12 m.

An adaptive algorithm based on k-means clustering for floor identification is developed and tested on a private dataset with a testbed surface area greater than 140,000 sq.m, achieving floor accuracy up to 97.84% [32]. Two novel designs, a two-step reliable feature selector and a multitask collaborative positioning model, are used on a private dataset, achieving accuracy of 99.90% and 99.40% for building and floor, respectively, and achieving position error up to 1.8 m [33]. Emphasis on eliminating mobile hotspots or unstable signal sources is given to privately collected data, and different machine learning algorithms (KNN and RF) are used for positioning [34]. Three multi-floor buildings are tested, with fingerprints collected primarily on a 1.5 sq.m grid. Forty fingerprints are taken at every RP, ten in each direction, resulting in an average position error of around 6 m. An automatic fingerprint collection with integrated information from a smart campus environment is presented [35]. A smart campus, which provides details of each student and staff member’s upcoming activities, such as a lecture in a specific lecture hall at a particular time, utilizes integrated information with a campus app to collect Wi-Fi fingerprints. It combines methods for filtering outliers if the conditions are not met. Experiments are conducted using a private dataset, which includes both manual and automated collection. Despite the advantage of automatic fingerprint collection without overhead, the smart campus environment required would incur capital costs and operational expenses, which may hinder the method’s adoption by a broad audience. Table 1 shows a summary of reviewed articles that experimented with private datasets only.

Table 1.

Summary of reviewed articles experimenting with private datasets only.

4.2. Public Datasets

Public datasets usage can be further divided into studies using machine learning algorithms, deep learning algorithms and other algorithms. The public datasets found were (covering areas over 10,000 sq.m): UJIIndoorLoc [36], Tampere [37], and UTSIndoorLoc [38] (mentioned as UJI, TUT and UTS, respectively). The UJI is the primary public dataset for the domain. It is still one of the largest datasets with a variety of parameters. It covers an area of 108,703 sq.m and includes three buildings in the same vicinity. There are 21,049 fingerprints, where 19,938 are for training, and 1111 are for testing, with over 933 RPs and 520 APs. An important factor is that the testing points were taken four months after the training points, ensuring data independence. The dataset consists of 520 RSS features and 9 other features, including longitude, latitude, floor number, building identification number, space representation number, user identification, phone identification and timestamp. Ten samples for each RP were recorded, with each room having one RP in the middle of the room and another RP adjacent to the outside of the door. The authors have acknowledged that, due to limited access, they recorded only the outside of the door RP for most rooms.

The TUT is one of the first completely crowd-sourced datasets in the domain. It covers an area of 22,750 sq.m with one building and five floors. The number of samples recorded is 4648, with 15% of the data used as the training set and 85% as the testing set, reflecting real-life scenarios. Samples were taken at random places instead of a fixed RP, and the number of samples taken per place is only one, contrary to a manually collected dataset, where the number of samples is higher per RP. There are 922 APs in the dataset with local xy coordinates and floor heights. The UTS is one of the first high-rise building datasets in the domain. It covers 44,000 sq.m surface area with a single building and 16 floors. The total sample size is 9494, with 9107 as the training set and 387 as the testing set. While the number of APs is 589, the number of RPs is 1840. It features local xy coordinates, floor identification number and other information with a time stamp. The information regarding the UTS is limited as it has been provided as a supplementary dataset rather than main dataset like the UJI and TUT.

4.2.1. Machine Learning Algorithms

A comprehensive study that includes different distance metrics, representation of raw data, and thresholding strategies is conducted [28]. The kNN positioning algorithm used in Wi-Fi fingerprinting generally employs Euclidean distance; however, alternative distance measures are also available, such as Manhattan distance, which is more suitable for indoor localization where there is limited movement and non-line-of-sight conditions. Their study compares 51 distance metrics along with four different representations of raw fingerprint data and the thresholding effect on accuracy. Their analysis reveals powedata representation and no use of thresholding at all, yielding the best results. Their experiments on UJI show a floor accuracy of up to 95.20% and a position error of 6.19 m. Extremely randomized trees are used in UJI, achieving 100% accuracy on building identification, 91.44% accuracy on floor identification, and 10.12 m error in positioning coordinates [39]. A confidence measure to reflect the uncertainty of the prediction is experimented with using UJI and kNN as a localizing algorithm, yielding up to 99.40% accuracy in building identification and up to 78.20% accuracy in floor identification [40]. Gaussian mixture model-based soft clustering and random decision forest ensembles for hybrid indoor localization are used on UJI, achieving 85% accuracy on room identification and 6.29 m error in positioning coordinates [41]. Although room information is provided in UJI, authors have mentioned that due to limited access inside the rooms, fingerprints are only taken outside the rooms, near the entrance doors, for most of the rooms in the dataset. Hence, the achieved accuracy most probably does not reflect the practical accuracy that can be obtained for room localization.

kNN with similarity measures is applied on UJI and TUT, reaching a building accuracy of 99.92% on UJI, a floor accuracy of 97.47% on UJI, and position errors of 8 m and 4 m in UJI and TUT, respectively [42]. This similarity measure approach does not require fingerprints to be arranged into vectors of equal length for distance calculations, thereby reducing system complexity. It shifts the traditional use of fingerprints, which is typical in machine learning and deep learning. Contrasting with the recommendation in [28] and similar to [27], fingerprint reduction is performed by selecting features on the UJI [43]. Six different machine learning algorithms are trained, achieving a building accuracy of up to 99.90%, floor accuracy of 99.61%, and room accuracy of 90%. Various machine learning algorithms are investigated using mean and median filtering for preprocessing in UJI [44]. WKNN-based localization, utilizing k-means clustering to further improve precision, is tested on UJI [45]. The impact of changing the default RSS value, typically +100 dBm, is investigated. Maximum accuracy is achieved at −95 dBm, with a building accuracy of 99.46%, a floor accuracy of 91.27%, and a position error of 8.62 m. Building upon the work in [46], a two-label hierarchical extreme learning machine is applied to UJI, TUT, and UTS, yielding floor accuracies of 96.31%, 94.81%, and 95.36%, respectively [47]. The position errors obtained are up to 5.5 m, 8.73 m, and 6.43 m for UJI, TUT, and UTS, respectively. An extreme gradient boosting-based machine learning scheme is used on UJI and TUT, resulting in 100% building accuracy on UJI, 99.20%, and 97.03% floor accuracy on UJI and TUT, respectively, and 4.93 m and 7.02 m position error on UJI and TUT, respectively [48]. A database clustering method based on signal distance and position distance, along with the WKNN algorithm for localization, is tested on UJI, achieving a floor accuracy of 87.70% and a position error of 6.84 m [49].

Samples are sorted into positive samples, relatively close to each other, and negative samples, relatively far from each other, to create new relative features [50]. These features are then trained on traditional machine learning algorithms for the classification of individual buildings in UJI. An approach using neural networks, consisting of a sequence of algorithms to narrow down the location solutions to smaller spaces, is tested on UJI, yielding building and floor accuracies of 100% and 95.52%, respectively, and a position error of 9.68 m [51]. A machine learning based framework, which, when trained on one building, could be used in another building, a different idea from [22], which mentions the requirement of even different models in a single building for other floors, is used on UJI, achieving 94.15% floor accuracy and 8.45 m position error [52]. Only 5% of the UJI dataset is utilized to train algorithms, as their method only requires access to the strongest signal access points for estimation. A distance metric learning k-nearest neighbor-based method is used on UJI, achieving 98.52% floor accuracy and 6.93 m position error [53]. KNN, RF, and ANN, coupled with optimization algorithms such as gradient descent and grid search, are used on UJI, resulting in up to 100% and 90.50% accuracy on building and floor identification, respectively [54]. Table 2 shows a summary of reviewed articles experimenting with public datasets using machine learning.

Table 2.

Summary of reviewed articles experimenting with public datasets using machine learning.

4.2.2. Deep Learning Algorithms

The usage of deep learning algorithms can be further subdivided into studies using CNN and other DL algorithms. A single-layer convolutional neural network (CNN) is trained to assess the effect of varying hyperparameters on UJI, achieving 89.90% floor accuracy [55]. This study demonstrates an early application of deep learning for indoor localization. SAE with a one-dimensional CNN is used on UJI, TUT, and UTS [38]. Their experiments achieved up to 100% accuracy in building identification on UJI, while achieving 96.03%, 94.22%, and 94.57% accuracy in floor identification on UJI, TUT, and UTS, respectively. The position errors found are up to 11.78 m, 10.88 m, and 7.60 m on UJI, TUT, and UTS, respectively. This work also introduces the UTSIndoorLoc dataset. Early work of [38], SAE with one-dimensional CNN is used on UJI and TUT, achieving 95.92% and 94% floor-level accuracy, respectively, along with 100% building accuracy on UJI [56]. A unified approach, based on training a single neural network to classify the building/floor and predict the position in a single forward pass of the network, is used [57]. SAE and CNN are utilized for estimation on UJI, TUT, and UTS, resulting in floor accuracies of 94.7%, 94.6%, and 95.3%, respectively, and position errors of 7.32 m, 7.07 m, and 7.30 m, respectively. A lightweight combination of CNN and ELM, suitable for resource-constrained devices, is used in twelve fingerprinting datasets that provide quick and accurate classification [58].

An image-based approach using a 2D-CNN classifier is used on UJI, achieving 97.69% floor accuracy [59]. An ELM autoencoder with a two-dimensional CNN is used on the UJI and TUT datasets to achieve floor accuracy up to 96.31% and 95.30%, respectively, and position error up to 8.34 m and 7.96 m, respectively [60]. A federated learning framework based on CNN and an autoencoder is used on UJI [61]. A hierarchical-based framework with a feedforward neural network and a CNN is used on UJI, with floor accuracy up to 93% and position error up to 8.19 m [62]. A combination of wavelet transform for data preprocessing and CNN as a positioning model is used on UJI, with building and floor accuracy up to 99.91% and 95.96% respectively [63]. A light CNN-based method using edge computing is evaluated on an Android smartphone [64]. Their method achieved a building accuracy of 99.4% on the UJI dataset. Floor accuracy and position error in UJI, TUT, and UTS are up to 90.5%, 88.9%, and 92%, respectively, with corresponding errors of 9.5 m, 10.24 m, and 7.7 m, respectively. On the UJI dataset, their model achieved a building accuracy of up to 99%, a floor accuracy of over 90%, and a position error of 9.5 m, with a model size of 0.5 MB and an inference time of 51 microseconds. A CNN combined with an autoencoder-based method is evaluated on UJI and TUT, achieving a floor hit rate of 95.58% on UJI and a position error of up to 4.55 m and 8.13 m on UJI and TUT, respectively [65].

A lightweight 2D-CNN that can be implemented in resource-constrained devices is used on UJI, TUT, and UTS, resulting in up to 94.33%, 91.32%, and 94.85% floor accuracy, respectively [66]. SAE, attention mechanisms, and CNNs are used on UJI, achieving building and floor level accuracy of 99.80% and 99.30% respectively, and 6.41 m position error [67]. A hierarchical stagewise training framework with DNN and CNN is experimented with on UJI and UTS, achieving 100% building accuracy on UJI, as well as 94.42% and 95.1% floor accuracy, and 8.71 m and 7.87 m position errors in UJI and UTS, respectively [68]. A plug-and-play-based knowledge transfer framework is studied and tested on UJI, TUT, and UTS, yielding position errors of up to 10.79 m, 7.73 m, and 6.30 m, respectively [69]. Table 3 shows a summary of reviewed articles experimenting with public datasets using CNN.

Table 3.

Summary of reviewed articles experimenting with public datasets using CNN.

Stacked autoencoders (SAE) are used on UJI, achieving 98% accuracy on floor identification [70]. Two consecutive multi-layer perceptrons are used for building and floor identification in UJI, achieving 100% and 84.33% accuracy, respectively [71]. Authors make an excellent remark on the requirement for controlling the inaccuracy of the positioning system, mentioning that if a user’s destination is building B’s third floor from building A’s third floor, it is better for the user to go to the second floor of building B rather than any floor of building A. Furthermore, considering user effort, even going to Building B’s fourth floor requires a greater expenditure of time and energy, given the traditional route between the two buildings. These minor details, such as the structure of the buildings and shortest routes, can help increase the system’s accuracy and reliability. This is implemented on [21], which utilizes the building structure in its experiment to achieve better accuracy. Deep neural networks with stacked autoencoders (SAE) are used in UJI, achieving 98% accuracy on floor identification [72]. A single-input, multiple-output DNN, along with stacked autoencoders (SAE), is used on TUT, achieving 94% accuracy in floor identification [73].

Extending the application of [30] to UJI, the authors use SAE to achieve 100%, 99.66%, and 83.47% accuracy on building, floor, and room, respectively [74]. The extreme learning machine (ELM) and KNN-based system are tested on UJI, achieving 100% and 95.41% accuracy on building and floor, respectively, and the position error found is up to 6.40 m [75]. A localization system based on SAE is used on UJI to achieve floor accuracy up to 96% [76]. A variational autoencoder with deep reinforcement learning is used on UJI for positioning, achieving an error of up to 4.65 m [77]. ELM and SAE are used on UJI to achieve a floor accuracy of 98.13% [46]. Recurrent neural networks are used in UJI, achieving 100% building accuracy, 95.23% floor accuracy, and 8.62 m position error [78]. A Markov decision-based localization system utilizing deep reinforcement learning is employed on UJI and UTS, achieving a localization time of approximately 8 milliseconds [79]. Deep learning is applied in UJI and TUT, resulting in up to 99.56% building accuracy, 92.62% floor accuracy, and 9.07 m position error in UJI [80]. Graph neural networks are utilized to leverage geometric information in fingerprints on UJI, achieving accuracies of up to 99% and 92% in building and floor identification, respectively [81]. The authors have proposed a method for constructing the graph using only fingerprints, rather than an actual floor plan, thereby reducing costs. Hierarchical-based deep neural networks are trained on UJI and TUT, resulting in floor accuracies of 93.88% and 98.06%, respectively, and position errors of 11.27 m and 13.21 m, respectively, with an average inference time of 8 milliseconds [82].

A multi-level feature extraction and autoregressive location estimation approach is used for real-time location requests, which includes a feature encoder and a location decoder [83]. Their experiments on UJI showed a floor accuracy of up to 95.30% and a position error of up to 7.65 m. SAE and an attention-based long short-term memory framework are used on UJI, TUT, and UTS, achieving position errors of up to 8.28 m, 9.52 m, and 6.48 m, respectively [84]. A federated graph learning approach, utilizing a graph convolutional network via normalized averaging with regularization, is employed on UJI, achieving 99% and 87.80% building and floor accuracy, respectively [85]. A gradient boosting neural network and an LSTM network are used on UJI and TUT, achieving 100% building accuracy on UJI, 95.23% and 95.34% floor accuracy, and 7.82 m and 6.89 m position error in UJI and TUT, respectively [86]. A novel method integrating Fuzzy C-means clustering with deep learning autoencoders is used on UJI, achieving up to 99.80% and 99.53% building and floor accuracy, respectively, and a position error of up to 3.26 m [87]. A DNN-based approach is used on UJI and UTS, achieving 100% building accuracy on UJI, 94.69% and 96.39% floor accuracy, and 5.08 m and 4.29 m position error in UJI and UTS, respectively [88]. Table 4 shows a summary of reviewed articles experimenting with public datasets using DL algorithms other than CNN.

Table 4.

Summary of reviewed articles experimenting with public datasets using DL algorithms other than CNN.

4.2.3. Others

The shortcomings of Euclidean distance, such as its significance only when there is a line-of-sight, obstacles, and floor transitions, which can lead to logical errors, are addressed by developing procedures to minimize localization errors [89]. Results on the UJI dataset show a building accuracy of up to 100%, a floor accuracy of 96.25%, and a position error of 8.34 m. The authors mention that there is a lack of standard evaluation procedures due to these logical errors, which disable credible comparisons between various studies conducted in the indoor localization domain. A more accurate measure of positioning error could be the length of the pedestrian path that connects the estimated position to the true position. A graph-based correlation approach is used on TUT to achieve a floor accuracy of 96.93% and a position error of 8.12 m [90]. A weighted fusion-based efficient clustering strategy on individual buildings of UJI is tested, showing an increase in accuracy while new features are used [91]. The position error obtained is up to 6.5 m, and the average localization time is 8 milliseconds. A novel probabilistic model based on classical likelihood estimation is tested on UJI, resulting in up to 6.94 m position error [92]. Table 5 shows a summary of reviewed articles experimenting with public datasets and other algorithms beyond ML and DL.

Table 5.

Summary of reviewed articles experimenting with public datasets using other algorithms than ML and DL.

5. Discussion

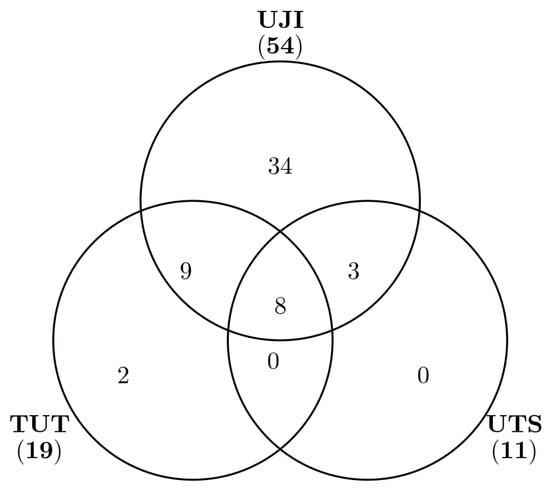

Many studies experiment with their own private datasets of varying sizes. Older studies primarily relied solely on their private datasets, while the trend now shifts toward using both private and public datasets to validate their positioning methods. 15 out of 71 studies use only a private dataset for evaluation. Three main public datasets are frequently used, each covering areas over 10,000 sq.m: UJIIndoorLoc (UJI), Tampere (TUT), and UTSIndoorLoc (UTS). UJI is a multi-building, multi-floor dataset that includes three adjacent buildings, each with 4–5 floors, covering an area of 108,703 sq.m. It is the largest publicly available Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting dataset to date, collected manually in 2014 by multiple users using various mobile devices to ensure the quality of the fingerprint. TUT is a crowdsourced dataset from a single building with five floors, collected in 2017, covering 22,750 sq.m. UTS was collected manually in 2019 and features a single building with 16 floors, representing a city-based university building with an area of 44,000 sq.m. Of the 71 studies, 54 used the UJI, 19 used the TUT, and 11 used the UTS. Additionally, 9 studies utilized only UJI and TUT, while 3 used only UJI and UTS. Eight studies used all three datasets. Figure 2 displays the Venn diagram of the public datasets used.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of the number of studies utilizing public datasets.

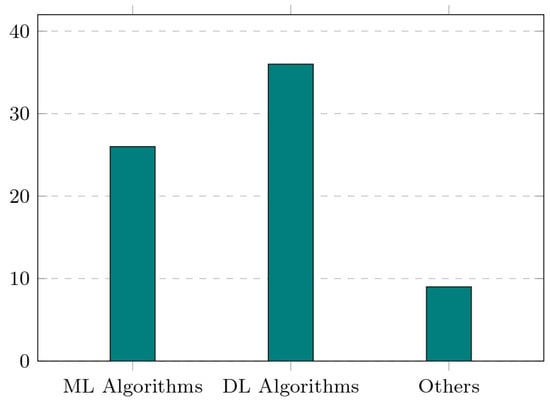

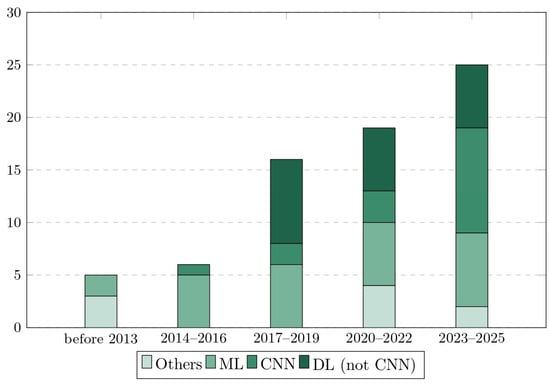

Most studies chose machine learning (ML) or deep learning (DL) methods for positioning or used them in preprocessing. Overall, 36 studies have implemented DL algorithms, 26 have used ML algorithms, and 9 have employed other types of algorithms, as shown in Figure 3. Few studies have explored graph, similarity, or correlation-based approaches without ML or DL. K-nearest neighbor (kNN) is often the standard benchmarking algorithm for dataset evaluation. 10 studies have used kNN for testing or applied a variant to improve performance. While many other ML algorithms, such as linear regression, support vector machines, gradient boosting, random forests, and decision trees, have been used, DL algorithms are the most common. Mainly, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Stacked Autoencoders (SAEs) are employed. A total of 16 studies utilize CNNs, 15 use SAEs, and 5 incorporate both CNNs and SAEs into their systems. The increasing use of DL algorithms like CNNs and SAEs seems to be driven by the lower calibration effort required to process fingerprints and their high accuracy. Figure 4 shows the usage of different algorithms over the years. The trend clearly indicates an increase in the use of CNN over the years, with the highest use in recent years.

Figure 3.

Usage of ML, DL and other algorithms.

Figure 4.

Trend of using different algorithms by year.

Main metrics include accuracy, maximum position error, and inference or localization time. For accuracy, building, floor, and room identification are used. Only a few studies focus on room identification and inference or localization time. Although UJI fingerprints contain room-level information, the authors clearly state that most data are collected outside the room due to limited access in many of the building’s rooms. A few studies experimenting with UJI’s room identification have achieved an average accuracy of 85%, but these results do not fully reflect real-world conditions. This might be why many studies do not consider UJI’s room-level location information. Additionally, regarding inference or localization time, few studies report times of around 8 milliseconds. However, the Wi-Fi scanning time, in seconds, increases overall localization time in order of seconds.

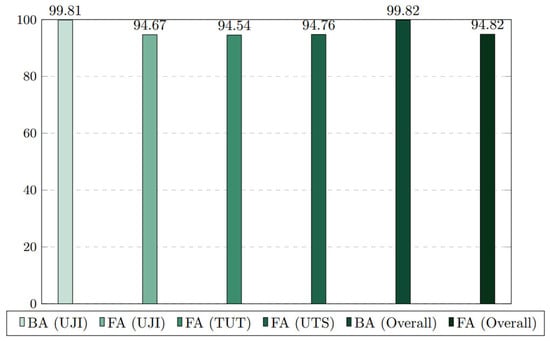

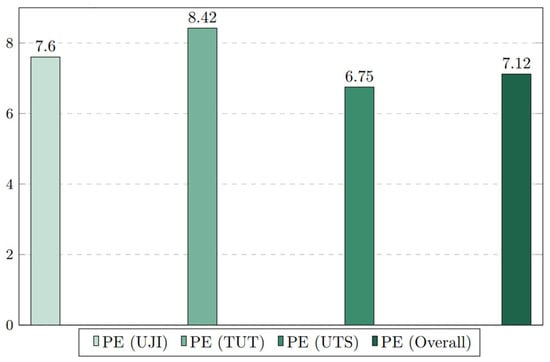

Out of the three public datasets—UJI, TUT, and UTS—UJI is the only one with multiple buildings. Our review reveals a mean accuracy of 99.81% in building identification on the UJI dataset. The mean floor identification accuracy for UJI, TUT, and UTS is 94.67%, 94.54%, and 94.76%, respectively. Furthermore, our review shows a mean maximum position error of 7.60 m, 8.42 m, and 6.75 m for UJI, TUT, and UTS, respectively. Overall, across all 71 studies, the mean accuracy for building and floor identification is 99.82% and 94.82%, respectively. Additionally, the overall mean maximum positioning error is 7.12 m. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show mean building and floor accuracies, and mean maximum position errors.

Figure 5.

Mean building and floor identification accuracy (%).

Figure 6.

Mean maximum position error in meters.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically searched and reviewed published research on Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting-based indoor location estimation in large multi-floor buildings from January 2009 to August 2025 using the SCOPUS and IEEE Xplore databases. It shows that there are mainly three popular public databases used in the area: UJIIndoorLoc (UJI), Tampere (TUT), and UTSIndoorLoc (UTS) datasets. The recent trend is towards the use of deep learning algorithms, such as CNNs and SAEs, across various parts of the localization process. Building accuracy, floor accuracy, and maximum position error are the three main performance metrics. The average building and floor accuracies are approximately 100% and 95%, respectively, while the average maximum positioning error is around 7 m. While building, floor, and position accuracy seem impressive, studies on room- or zone-level accuracy are required, as position estimates might jump over a room or even a floor in some cases, which hinders the overall accuracy of the system. Availability of only three main datasets delays the acceptability of methodologies in the domain. Furthermore, the quality of the dataset with a variety of essential features, generalization for floors without calibration and standardizing metrics must be given importance.

As shown in our methodology, we used different search indexes and fields for the SCOPUS and IEEE Xplore databases. This was to maximize the number of relevant articles taken for a timely review. Additionally, we acknowledge the importance of sensor fusion and its crucial role in improving practical localization; however, the primary focus for this study was to investigate Wi-Fi alone in larger areas at this point, so hybrid technologies can be investigated further to enhance the performance of Wi-Fi systems. For future researchers, we recommend delving into finer granularity than floor-level localization. This could be either zone-level localization or room-level localization. Furthermore, while DL algorithms provide finer accuracy, their computational requirements are higher. DL microarchitectures that require low computational resources need to be explicitly investigated for ILS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, I.N.; writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, S.S. and C.R.; funding acquisition, S.S. and I.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian Research Training Programme (RTP) Post-graduate Research Scholarship Award, and “The APC was funded by a waiver on my Principal Supervisor”. The Australian Government awarded the scholarship.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets used in this research are publicly available Kaggle, Zenodo and Github.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the doctoral research under the Research Training Programme (RTP) scholarship opportunity. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and comments on this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| RSS | Received Signal Strength |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| SAE | Stacked Autoencoder |

| CSI | Channel State Information |

| AP | Access Point |

| RP | Reference Point |

| VAP | Virtual Access Point |

| kNN | K-Nearest Neighbor |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| UJI | UJIIndoorLoc Dataset |

| TUT | Tampere Dataset |

| UTS | UTSIndoorLoc Dataset |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| BA | Building Accuracy |

| FA | Floor Accuracy |

| RA | Room Accuracy |

| PE | Position Error |

| ILS | Indoor Location System |

| CILS | Collaborative Indoor Location System |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

References

- Xia, S.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, G.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Z. Indoor fingerprint positioning based on Wi-Fi: An overview. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Wang, L. Overview of WiFi fingerprinting-based indoor positioning. IET Commun. 2022, 16, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhomayani, F.; Mahoor, M.H. Deep learning methods for fingerprint-based indoor positioning: A review. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2020, 14, 129–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Choe, S.; Punmiya, R. Machine Learning Based Indoor Localization Using Wi-Fi RSSI Fingerprints: An Overview. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 127150–127174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafari, F.; Gkelias, A.; Leung, K.K. A Survey of Indoor Localization Systems and Technologies. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2568–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguntala, G.; Abd-Alhameed, R.; Jones, S.; Noras, J.; Patwary, M.; Rodriguez, J. Indoor location identification technologies for real-time IoT-based applications: An inclusive survey. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2018, 30, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascacio, P.; Casteleyn, S.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Lohan, E.S.; Nurmi, J. Collaborative indoor positioning systems: A systematic review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, S.; Pyun, J.-Y. A survey of smartphone-based indoor positioning system using RF-based wireless technologies. Sensors 2020, 20, 7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, I.; Zikria, Y.B.; Garg, S.; Hur, S.; Park, Y.; Guizani, M. Enabling Technologies and Techniques for Floor Identification. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.; Harras, K.A.; Youssef, M. A Survey of Indoor Localization Systems for Multi-Floor Environments. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 146396–146432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fu, M.; Wang, J.; Luo, H.; Sun, L.; Ma, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Huang, R.; Li, X. Recent advances in floor positioning based on smartphone. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2023, 214, 112813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retscher, G. Fundamental Concepts and Evolution of Wi-Fi User Localization: An Overview Based on Different Case Studies. Sensors 2020, 20, 5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chan, S.-H.G. Wi-Fi fingerprint-based indoor positioning: Recent advances and comparisons. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 18, 466–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.K.M.M.; Soh, W.-S. A survey of calibration-free indoor positioning systems. Comput. Commun. 2015, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhu, F.; Bu, J.; Dua, X. The State of the Art of Deep Learning-Based Wi-Fi Indoor Positioning: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 27076–27098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Nguyen, K.A.; Luo, Z. A Review of Open Access WiFi Fingerprinting Datasets for Indoor Positioning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 167970–167989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Nguyen, K.A.; Luo, Z. A survey of deep learning approaches for WiFi-based indoor positioning. J. Inf. Telecommun. 2022, 6, 163–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Chowdhury, C. A survey on ubiquitous WiFi-based indoor localization system for smartphone users from implementation perspectives. CCF Trans. Pervasive Comput. Interact. 2022, 4, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Choi, E.; Oh, H. Observation and motion models for indoor pedestrian tracking. In Proceedings of the 2012 2nd International Conference on Digital Information and Communication Technology and its Applications, DICTAP 2012, Bangkok, Thailand, 16–18 May 2012; pp. 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Sang, N. Enhanced wi-fi fingerprinting with building structure and user orientation. In Proceedings of the 2012 8th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Sensor Networks, MSN 2012, Chengdu, China, 14–16 December 2012; pp. 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshad, A.; Li, J.; Marina, M.K.; Garcia, F.J. A microscopic look at WiFi fingerprinting for indoor mobile phone localization in diverse environments. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation, IPIN 2013, Montbeliard-Belfort, France, 28–31 October 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Talvitie, J.; Lohan, E.S. On the fingerprints dynamics in WLAN indoor localization. In Proceedings of the 2013 13th International Conference on ITS Telecommunications, ITST 2013, Tampere, Finland, 5–7 November 2013; pp. 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.S.; Lovisolo, L.; de Campos, M.L.R. Search space reduction in DCM positioning using unsupervised clustering. In Proceedings of the 2013 10th Workshop on Positioning, Navigation and Communication (WPNC), Dresden, Germany, 20–21 March 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Jung, S.; Lee, M.; Yoon, G. Building a Practical Wi-Fi-Based Indoor Navigation System. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2014, 13, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, A.; Valkama, M.; Lohan, E.-S. K-means fingerprint clustering for low-complexity floor estimation in indoor mobile localization. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Globecom Workshops, GC Wkshps 2015—Proceedings, San Diego, CA, USA, 6–10 December 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.A.; Dashti, M.; Zhang, J. Floor determination for positioning in multi-story building. In Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference, WCNC, Istanbul, Turkey, 6–9 April 2014; pp. 2540–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sospedra, J.; Montoliu, R.; Trilles, S.; Belmonte, Ó.; Huerta, J. Comprehensive analysis of distance and similarity measures for Wi-Fi fingerprinting indoor positioning systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 9263–9278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. HILLS: Hierarchical Indoor Localization for Large-Scale Architectural Complex. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Singapore, 17–20 November 2018; pp. 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BelMannoubi, S.; Touati, H. Deep Neural Networks for Indoor Localization Using WiFi Fingerprints. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference, MSPN 2019, Mohammedia, Morocco, 23–24 April 2019; pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongsuteera, T.; Rojviboonchai, K. Adaptive Indoor Localization System for Large-Scale Area. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 8847–8865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Luo, H.; Zhao, F.; Tian, H.; Huang, J.; Crivello, A. Floor Identification in Large-Scale Environments with Wi-Fi Autonomous Block Models. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, J.; Liu, X.; He, X. Secure and Reliable Indoor Localization Based on Multitask Collaborative Learning for Large-Scale Buildings. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 22291–22303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckner, M.; Sowik, S.; Brida, P. Selection of Signal Sources Influence at Indoor Positioning System. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwijaksara, M.H.; Darmawan, I.B.S.; Angelina, M.A.; Partogi, S.R.; Arfiansyah, L.; Wibisono, A. Low Overhead Wi-Fi Fingerprinting-based Indoor Positioning for Evacuation Support System during Disaster in Smart Campus. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Industry 4.0, Artificial Intelligence, and Communications Technology (IAICT), Bali, Indonesia, 3–5 July 2025; pp. 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sospedra, J.; Montoliu, R.; Martínez-Usó, A.; Avariento, J.P.; Arnau, T.J.; Benedito-Bordonau, M.; Huerta, J. UJIIndoorLoc: A new multi-building and multi-floor database for WLAN fingerprint-based indoor localization problems. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Busan, Republic of Korea, 27–30 October 2014; pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohan, E.S.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Leppäkoski, H.; Richter, P.; Peng, Z.; Huerta, J. Wi-Fi crowdsourced fingerprinting dataset for indoor positioning. Data 2017, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Fan, X.; Xiang, C.; Ye, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Yang, N.; Fang, G. A Novel Convolutional Neural Network Based Indoor Localization Framework With WiFi Fingerprinting. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 110698–110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.T.; Islam, M.M. Extremely randomized trees for Wi-Fi fingerprint-based indoor positioning. In Proceedings of the 2015 18th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology, ICCIT 2015, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 21–23 December 2015; pp. 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.A. A performance guaranteed indoor positioning system using conformal prediction and the wifi signal strength. J. Inf. Telecommun. 2017, 1, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, B.A.; Akbar, A.H.; Shafiq, O. HybLoc: Hybrid Indoor Wi-Fi Localization Using Soft Clustering-Based Random Decision Forest Ensembles. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 38251–38272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wieser, A. CDM: Compound Dissimilarity Measure and an Application to Fingerprinting-Based Positioning. In Proceedings of the IPIN 2018—9th International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation, Nantes, France, 24–27 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolo, G.H.; Sampaio, I.G.B.; Viterbo, J. Feature selection on database optimization for Wi-Fi fingerprint indoor positioning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 159, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, M.W.; Umair, M.Y.; Mirza, A.; Rao, F.; Wakeel, A.; Akram, S.; Subhan, F.; Khan, W.Z. Enhanced fingerprinting based indoor positioning using machine learning. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 69, 1631–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; De Lacerda, R.; Fiorina, J. WKNN indoor Wi-Fi localization method using k-means clustering based radio mapping. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 93rd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2021-Spring), Helsinki, Finland, 25–28 April 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitaleshi, A.; Jazayeriy, H.; Kazemitabar, S.J. WiFi Fingerprinting based Floor Detection with Hierarchical Extreme Learning Machine. In Proceedings of the 2020 10h International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering, ICCKE 2020, Mashhad, Iran, 29–30 October 2020; pp. 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitaleshi, A.; Jazayeriy, H.; Kazemitabar, J. Affinity propagation clustering-aided two-label hierarchical extreme learning machine for Wi-Fi fingerprinting-based indoor positioning. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2022, 13, 3303–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Choe, S.; Punmiya, R.; Kaur, N. XGBLoc: XGBoost-Based Indoor Localization in Multi-Building Multi-Floor Environments. Sensors 2022, 22, 6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Fukunaga, H.; Ishizuka, R.; Li, T.; Tateno, S. Multi-floor Positioning Method based on RSSI in Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 61st Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers (SICE), Kumamoto, Japan, 6–9 September 2022; pp. 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hu, M.; Dong, G. A high available and strong generalization capability data-driven-based wireless fingerprint positioning model. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Big Data and Algorithms (EEBDA), Changchun, China, 24–26 February 2023; pp. 1812–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agah, N.; Evans, B.; Meng, X.; Xu, H. A Local Machine Learning Approach for Fingerprint-based Indoor Localization. In Proceedings of the SoutheastCon 2023, Orlando, FL, USA, 1–16 April 2023; pp. 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimman, S.C.; Alphones, A. DumbLoc: Dumb Indoor Localization Framework Using Wi-Fi Fingerprinting. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 14623–14630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Cui, Y. WIFI Fingerprint Correction for Indoor Localization Based on Distance Metric Learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 36167–36177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S.; Saif, S.; Biswas, S. Optimizing Indoor Positioning: ANN-GD Fusion for Enhanced Accuracy in WiFi Fingerprint-Based Surveillance Systems. SN Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiweiss, A. A mobile indoor positioning system founded on convolutional extraction of learned WLAN fingerprints. In Proceedings of the ICPRAM 2016Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods, Rome, Italy, 24–26 February 2016; pp. 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Fan, X.; He, X.; Xiang, C.; Ye, Q.; Huang, X.; Fang, G.; Chen, L.L.; Qin, J. CNNLoc: Deep-Learning Based Indoor Localization with WiFi Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation (SmartWorld/SCALCOM/UIC/ATC/CBDCom/IOP/SCI), Leicester, UK, 19–23 August 2019; pp. 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, M.; Blankenbach, J. Multi-Task Neural Network for Position Estimation in Large-Scale Indoor Environments. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 26024–26032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Gaibor, D.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Nurmi, J.; Koucheryavy, Y.; Huerta, J. Lightweight Hybrid CNN-ELM Model for Multi-building and Multi-floor Classification. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Localization and GNSS, ICL-GNSS 2022—Proceedings, Tampere, Finland, 7–9 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonny, A.; Kumar, A. Fingerprint Image-Based Multi-Building 3D Indoor Wi-Fi Localization Using Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 National Conference on Communications, NCC 2022, Mumbai, India, 24–27 May 2022; pp. 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitaleshi, A.; Jazayeriy, H.; Kazemitabar, J. EA-CNN: A smart indoor 3D positioning scheme based on Wi-Fi fingerprinting and deep learning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 117, 105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Yang, F.; Cui, N.; Xiong, K.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y. A Federated Learning Framework for Fingerprinting-Based Indoor Localization in Multibuilding and Multifloor Environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 2615–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kim, K.S.; Tang, Z.; Smith, J.S. Stage-Wise and Hierarchical Training of Linked Deep Neural Networks for Large-Scale Multi-Building and Multi-Floor Indoor Localization Based on Wi-Fi Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Symposium on Computing and Networking Workshops, CANDARW 2023, Matsue, Japan, 27–30 November 2023; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Tian, C. Localization of Multi-Building Floors Based on Wavelet-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition, Xiamen, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargar-Barzi, A.; Farahmand, E.; Chatrudi, N.T.; Mahani, A.; Shafique, M. An Edge-Based WiFi Fingerprinting Indoor Localization Using Convolutional Neural Network and Convolutional Auto-Encoder. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 85050–85060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslantas, H.; Okdem, S. Indoor Localization With an Autoencoder-Based Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 46059–46066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, I.; Shahrestani, S.; Ruan, C. Indoor Localization of Resource-Constrained IoT Devices Using Wi-Fi Fingerprinting and Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 Australasian Computer Science Week, Sydney, Australia, 29 January–2 February 2024; pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Miao, F.; Xia, Y.; Zhu, H. Indoor Localization via Deep Learning with Self-Attention and Stacked Denoising Autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Interactive Intelligent Systems and Techniques, IIST 2024, Bhubaneswar, India, 4–5 March 2024; pp. 242–246. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Kim, K.S.; Tang, Z.; Smith, J.S. Hierarchical Stagewise Training of Linked Deep Neural Networks for Multibuilding and Multifloor Indoor Localization Based on Wi-Fi RSSI Fingerprinting. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 23341–23351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.M.; Tran, L.D.; Le, D.V.; Havinga, P.J.M. Multi-Surrogate-Teacher Assistance for Representation Alignment in Fingerprint-Based Indoor Localization. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 6818–6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, M.; Wietrzykowski, J. Low-effort place recognition with WiFi fingerprints using deep learning. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 550, pp. 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.S. Automatic building and floor classification using two consecutive multi-layer perceptron. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems, PyeongChang, Republic of Korea, 17–20 October 2018; pp. 87–91. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85060482800&partnerID=40&md5=7bc80f9f4993342769419b041ee59005 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Joseph, R.; Sasi, S.B. Indoor Positioning Using WiFi Fingerprint. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Circuits and Systems in Digital Enterprise Technology, ICCSDET 2018, Kottayam, India, 21–22 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S. Hybrid building/floor classification and location coordinates regression using a single-input and multi-output deep neural network for large-scale indoor localization based on Wi-Fi fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 2018 6th International Symposium on Computing and Networking Workshops, CANDARW 2018, Takayama, Japan, 27–30 November 2018; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmannoubi, S.; Touati, H.; Snoussi, H. Stacked auto-encoder for scalable indoor localization in wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference, IWCMC 2019, Tangier, Morocco, 24–28 June 2019; pp. 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.; Khir, M.H.B.M.; Djaswadi, G.W.B.; Ramli, N. A Hybrid Model Based on Constraint OSELM, Adaptive Weighted SRC and KNN for Large-Scale Indoor Localization. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 6971–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, B. A wifi positioning algorithm based on deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Conference on Information, Communication and Networks, ICICN 2019, Macao, China, 24–26 April 2019; pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidlovskii, B.; Antsfeld, L. Semi-supervised Variational Autoencoder for WiFi Indoor Localization. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Pisa, Italy, 30 September–3 October 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Elesawi, A.E.; Kim, K.S. Hierarchical Multi-Building And Multi-Floor Indoor Localization Based On Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 9th International Symposium on Computing and Networking Workshops, CANDARW 2021, Matsue, Japan, 23–26 November 2021; pp. 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, F.; Lu, J.; Xu, T.; Huang, C.H.; Bi, J. A Bisection Reinforcement Learning Approach to 3-D Indoor Localization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 6519–6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, M.; Blankenbach, J. Deeplocbox: Reliable fingerprinting-based indoor area localization. Sensors 2021, 21, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezama, F.; González, G.G.; Larroca, F.; Capdehourat, G. Indoor Localization using Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE URUCON, Montevideo, Uruguay, 24–26 November 2021; pp. 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Lim, E. A hierarchical auxiliary deep neural network architecture for large-scale indoor localization based on Wi-Fi fingerprinting [Formula presented]. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 120, 108624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, F.; Shi, M.; Kong, X. Multi-Level Feature Extraction and Autoregressive Prediction Based Wi-Fi Indoor Fingerprint Localization. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC), Chongqing, China, 17–19 November 2023; pp. 1424–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinla, S.L.; Aziz, A.A.; Drieberg, M. SALLoc: An Accurate Target Localization in WiFi-Enabled Indoor Environments via SAE-ALSTM. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 19694–19710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Gao, B.; Xiong, K. FGLNoRe: Federated Graph Learning on Non-IID RF Fingerprints for Building-Floor Positioning. In Proceedings of the ICEIEC 2024—Proceedings of 2024 IEEE 14th International Conference on Electronics Information and Emergency Communication, Beijing, China, 24–25 May 2024; pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gong, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, C. An Efficient and Robust Fingerprint-Based Localization Method for Multiflloor Indoor Environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 3927–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahali, M.I.; Leu, J.S.; Putro, N.A.S.; Prakosa, S.W.; Avian, C. DeepFuzzLoc Positioning: A Unified Fusion of Fuzzy Clustering and Deep Learning for Scalable Indoor Localization Using Wi-Fi RSSI. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint 13th International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems and 25th International Symposium on Advanced Intelligent Systems (SCIS&ISIS), Himeji, Japan, 9–12 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinla, S.L.; Aziz, A.A.; Drieberg, M.; Susanto, M.; Tumian, A.; Yahya, M. An Enhanced Deep Neural Network Approach for WiFi Fingerprinting-Based Multi-Floor Indoor Localization. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Silva, G.M.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Potortì, F.; Moreira, A.; Knauth, S.; Berkvens, R.; Huerta, J. Beyond Euclidean Distance for Error Measurement in Pedestrian Indoor Location. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, W.; Zheng, J.; Xue, M.; Tang, C.; Zimmermann, R. Towards Floor Identification and Pinpointing Position: A Multistory Localization Model with WiFi Fingerprint. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2022, 20, 1484–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, P.; Dahal, K.; Das, P.K. A Novel Weighted Fusion Based Efficient Clustering for Improved Wi-Fi Fingerprint Indoor Positioning. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 4461–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rocha, A.M.; De Oliveira, G.N.; De Souza, L.J.V.; De Lacerda, R. tLoc: A Mathematical Probabilistic Model for Wireless Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Lyon, France, 26–30 August 2024; pp. 2032–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.