Abstract

In scaled laser-driven magnetized liner inertial fusion (MagLIF), externally applied magnetic fields improve energy coupling by suppressing electron thermal conduction, enhancing Joule heating, and increasing -particle energy deposition. However, confinement can be significantly degraded by magnetic flux transport, dominated by resistive diffusion, and more critically, the Nernst effect. One-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic simulations demonstrate that increasing the applied field generally enhances neutron yield, but when the Nernst effect is included, the benefit of stronger magnetization diminishes. Stagnation is achieved at 2.72 ns, yielding a peak temperature of 2.17 keV and a neutron production of . When the Nernst effect is taken into account, the neutron yield decreases by 57.3% compared with the case without it under an initial magnetic field of 10 T. During the implosion, the magnetic field in the fuel gradually diffuses outward into the outer liner. By stagnation, the magnetic flux of fuel has decreased by 33.8%. Based on the characteristics of the Nernst effect, an optimized initial magnetic field of approximately 6 T is identified, which yields an about 2.5 times higher neutron yield than the unmagnetized case. These findings emphasize the key role of magnetic–energy coupling in target performance and provide guidance for the design and scaling of magnetized targets.

1. Introduction

Magnetized liner inertial fusion (MagLIF) is a magneto-inertial fusion (MIF) concept that combines aspects of inertial confinement fusion (ICF) with applied magnetic fields to enhance energy coupling, and confinement [1,2,3]. In MagLIF, the fuel is preheated and magnetized prior to cylindrical compression, enabling implosions at lower velocities [4] (∼100 km/s) than are required in unmagnetized ICF (∼300 km/s), while also reducing convergence ratio demands [5]. Lowering the implosion velocity has minimal impact on the fuel’s areal density, enhances energy gain, and reduces sensitivity to instabilities, but necessitates higher temperatures [6]. The applied axial magnetic field suppresses electron thermal conduction [7] and allows nearly adiabatic compression. Consequently, compared with traditional ICF, MagLIF offers a more energy-efficient path toward ignition. As a result, magnetized plasmas require lower areal densities () for self-heating compared to unmagnetized fuel [8,9].

MagLIF has shown considerable promise in both simulations and experiments [10]. High-gain designs with cryogenic deuterium-tritium (DT) layers predict gains exceeding 100 [11]. Integrated experiments at Sandia’s Z facility have achieved average ion temperatures as high as [12,13], while the neutron yield increased by over an order of magnitude, reaching neutrons [14]. Scaled laser-driven MagLIF studies at OMEGA [15,16] employ parylene-N (CH) liners that are about ten times smaller, improving diagnostic access and providing insight into performance scaling with drive energy [17,18]. To compensate diagnostic capabilities, the areal density () in cylindrical implosions can be inferred from the ratio of secondary DT neutrons to primary DD neutrons [19]. Moreover, the beneficial effect of magnetization arises only if the magnetic pressure is negligible relative to the fuel pressure [20]. Magnetized targets driven by heavy-ion accelerator facility (HIAF [21]) are also under exploration [22], leveraging volumetric heating and longer implosion timescales [23,24]. These experiments highlight the progress of MagLIF and inform performance scaling and diagnostics.

A central challenge for scaling MagLIF is magnetic flux loss during compression, arising from resistive diffusion and the Nernst effect [25,26]. The Nernst effect, driven by perpendicular temperature gradients, convects magnetic flux outward and weakens confinement [4,5]. These processes can substantially reduce confinement and limit yield enhancement through energy coupling. A deeper understanding of this process is not only critical for interpreting current scaled experiments, but also essential for extending MagLIF to larger targets and for exploring heavy-ion–driven MagLIF concepts.

In this work, scaled laser-driven MagLIF with a CH liner is investigated, focusing on the interplay between magnetic field transport and thermal conduction under MagLIF-relevant conditions. A radiation magnetohydrodynamic model is employed to assess the impact of magnetic fields on neutron yield and to identify scaling trends with applied field strength. Before conducting the simulations, the contributions of both the Nernst and diffusion terms are quantitatively evaluated. Based on the theoretical formulations, an initial analytical assessment was conducted to evaluate the relative significance of the Nernst and diffusion terms. The analysis considered two representative plasma densities: one corresponding to the initial phase prior to preheating, and the other at stagnation. Evaluation of the corresponding Hall parameters and the ratio of the Nernst to diffusion term revealed that the Nernst effect becomes progressively more dominant as compression proceeds. Further investigation into the role of Ohmic heating feedback was carried out through scale analysis of characteristic time and length scales. The results indicate that in the scaled laser-Driven MagLIF configuration, Ohmic heating exerts only a minor influence, suggesting that the conversion of magnetic energy into internal energy via this mechanism is negligible under the present conditions. Full-scale simulations of the implosion process were subsequently performed, with optimization of the initial magnetic field. An initial field of 6 T was found to maximize the neutron yield, producing an enhancement of approximately 2.5 times compared to other configurations. These findings refine the understanding of the implosion dynamics and provide quantitative insight into the roles of transport and heating mechanisms in laser-driven magnetized implosions.

2. Physical Model

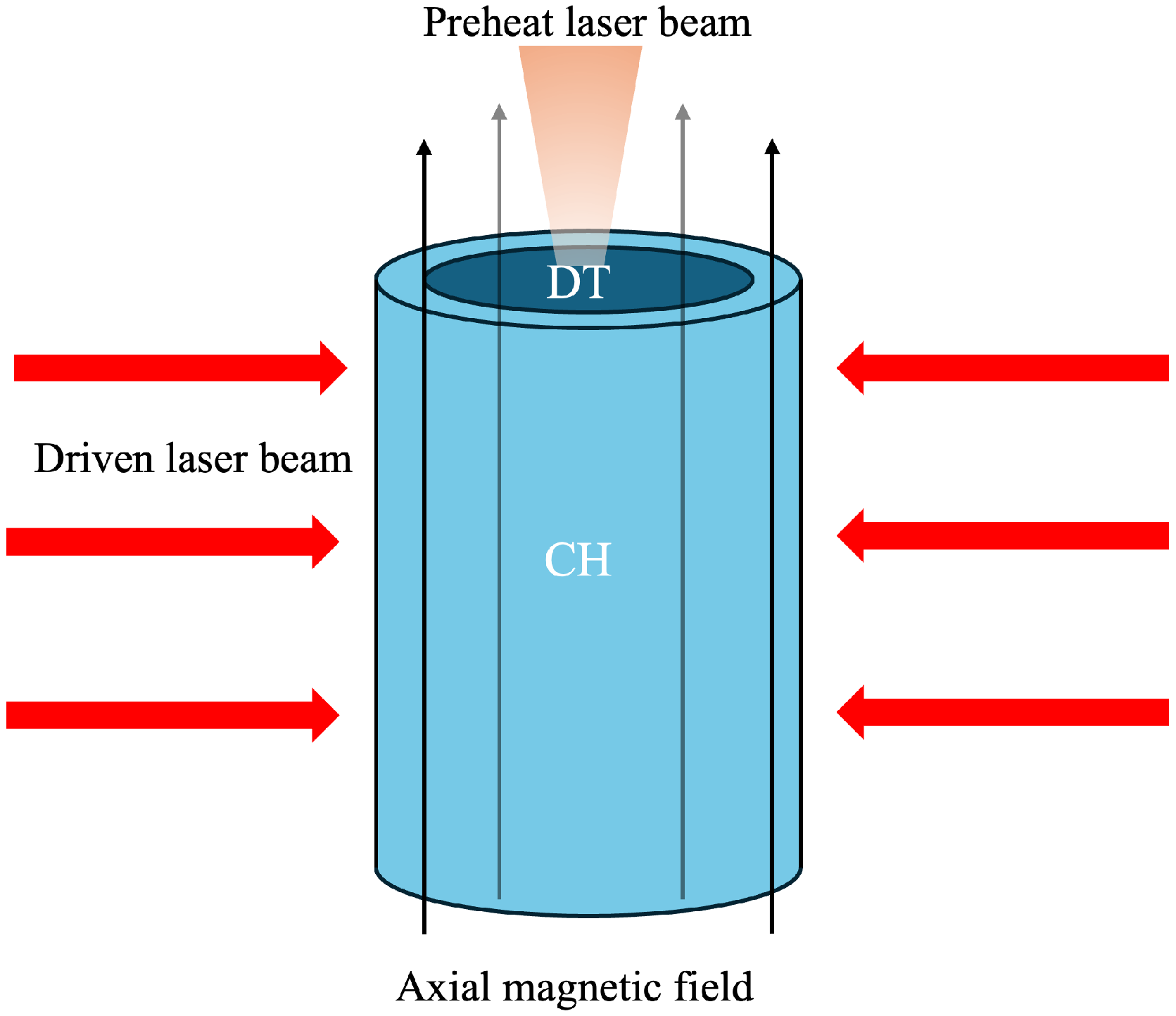

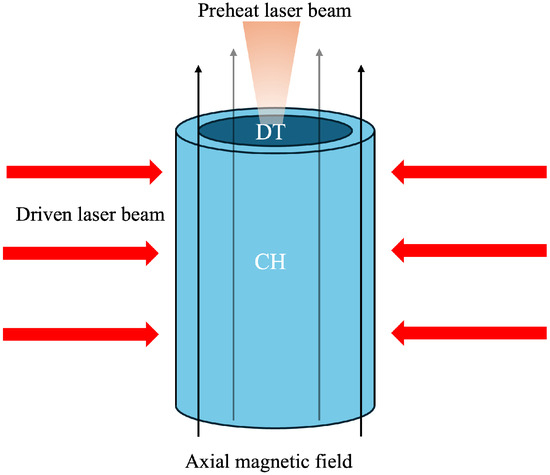

Magnetic transport in scaled laser-driven MagLIF has been incorporated into the one-dimensional, Lagrangian radiation magnetohydrodynamics code MULTI-IFE [27,28]. The target is composed of two layers, a parylene-N (CH) pusher layer (liner) and a DT fuel layer, as schematically shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the scaled laser-driven MagLIF concept.

In our radiation magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) model, several key physics relevant to magnetized target are available: two-component plasma hydrodynamics (ions and electrons), laser deposition, multigroup radiation transport, thermonuclear burn, -particle transport, thermal diffusion, and magnetic field evolution. These equations are solved in one-dimensional Lagrangian coordinates.

2.1. Governing Equations

The following integral equations describe the evolution of mass density , fluid velocity , specific internal energy e, and magnetic field :

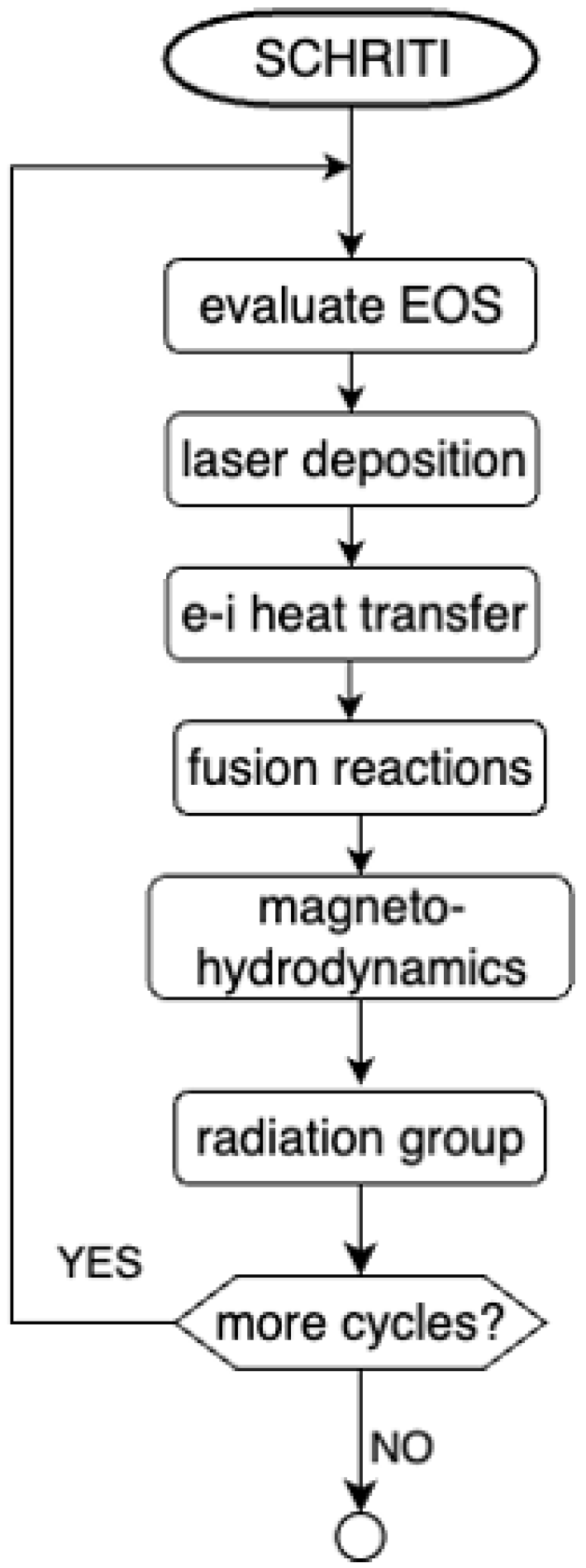

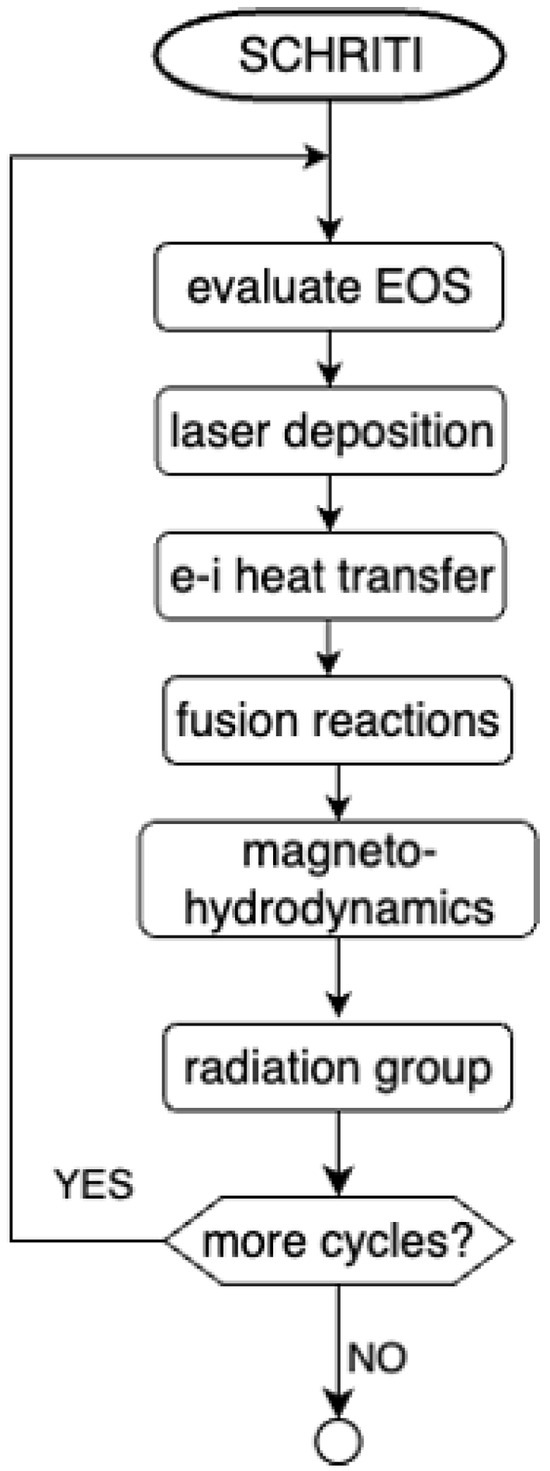

where V is the control volume moving with the fluid, is its boundary surface, and is the boundary of surface S. These integrals forms are suitable for Lagrangian discretization in MULTI-IFE code. Here, is the magnetic stress tensor, is the matter pressure tensor, is the electric field in the frame moving with the fluid, is the current density, and are the heat flux and radiation transport, respectively, and is the permeability. c is the speed of light, is the Planck mean opacity, is the normalized emissivity, and is the Planckian energy density. In radiation transfer Equations (6) and (7), these radiation parameters can be obtained from atomic physics models and computed using the SNOP code [29,30]. The diagram of the MULTI code is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the MULTI-IFE code.

The driven laser beam is defined as a normal incidence laser, in the Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) approximation. The pulse time shape is defined as a constant profile. With normal incidence, the laser light propagates until the critical surface. This work is based on a one-dimensional (1D) simulation, which represents a relatively idealized scenario. As such, it does not account for the effects of instabilities such as Rayleigh–Taylor. These instabilities would degrade implosion performance, leading to results that fall short of those predicted by 1D simulations.

2.2. Relevant Parameter Space for MagLIF

The expressions of magnetic field and electric field are further derived. The momentum interchange of electrons with ions is made up, in the linear approximation, of a frictional force () and a thermal force () [31]. The coefficients and are tensorial quantities that depend on the magnitude and direction of the magnetic field. Neglecting electron inertia (), the conservation of the electric momentum equation, which is based on Equation (2) in integral form, is expressed as

Expressing the density of current as , and as the Hall term is neglected in comparison to the frictional force, the generalized Ohm’s law is obtained:

The derivation details of resistive diffusion and the Nernst effect can be found in reference [5]. The axial magnetic field is decomposed into frozen-in, diffusive, and Nernst components:

where is the resistivity coefficient appearing in the diffusion term, and is the Nernst coefficient:

with .

The evolution of the magnetic field is governed by both advection with the bulk plasma flow (frozen-in flow) and transport processes. The first term in Equation (10) represents magnetic flux advection with the ideal fluid motion. The second term corresponds to magnetic diffusion, arising from electron collisions. The third term describes the Nernst effect, where perpendicular heat flux drives additional magnetic flux transport. These mechanisms also appear in the energy equation through the divergence of the heat flux, highlighting the intrinsic coupling between thermal transport and magnetic field evolution. In cylindrical geometry, magnetic diffusion and Nernst advection dominate flux loss, thereby reducing charged-particle confinement and degrading implosion performance.

Thermal energy and magnetic flux losses are studied in dense, collisional DT plasmas compressed by a laser-driven liner. In such plasmas, the thermal pressure () far exceeds the magnetic pressure, i.e.,

with typical values n∼∼∼ at stagnation.

The electron Hall parameter is correspondingly large:

where is the Coulomb logarithm.

Thus, the magnetic field evolution in laser-driven MagLIF can be understood in terms of three key processes: frozen-in advection with the bulk plasma, resistive diffusion due to collisions, and Nernst advection driven by electron heat flow. Together, these determine the coupling between magnetic fields and electron thermal transport.

2.3. Numerical Discretization in Axial Magnetic Field

During the magnetic-flux-transport step, the axial field B is firstly updated based on resistive diffusion and the Nernst term. Symbolically, the flux across each interface can be written as

where is Lagrangian cell length. The following space-discretized equation for the magnetic field is derived:

Magnetic-flux conservation is then enforced by ensuring that flux leaving one cell enters the adjacent cell:

Hence, the magnetic field is updated via these two steps. More derivation details and benchmark tests of magnetic field can be found in our previous manuscript [32].

2.4. Magnetic Flux Transport

In laser-driven MagLIF, the fuel is bounded by a colder liner of effectively infinite heat capacity, where the magnetic field is much weaker at stagnation. The liner, therefore, acts as a sink for both thermal energy and magnetic flux escaping from the fuel. Parametric studies based on Equations (11) and (12) capture the evolution of the diffusion and Nernst coefficients.

During compression, magnetic field, density and temperature can be estimated from flux and mass conservation, scaling with the convergence ratio , (, ), where , , and are the initial values. The parametric analysis focuses on the regime and .

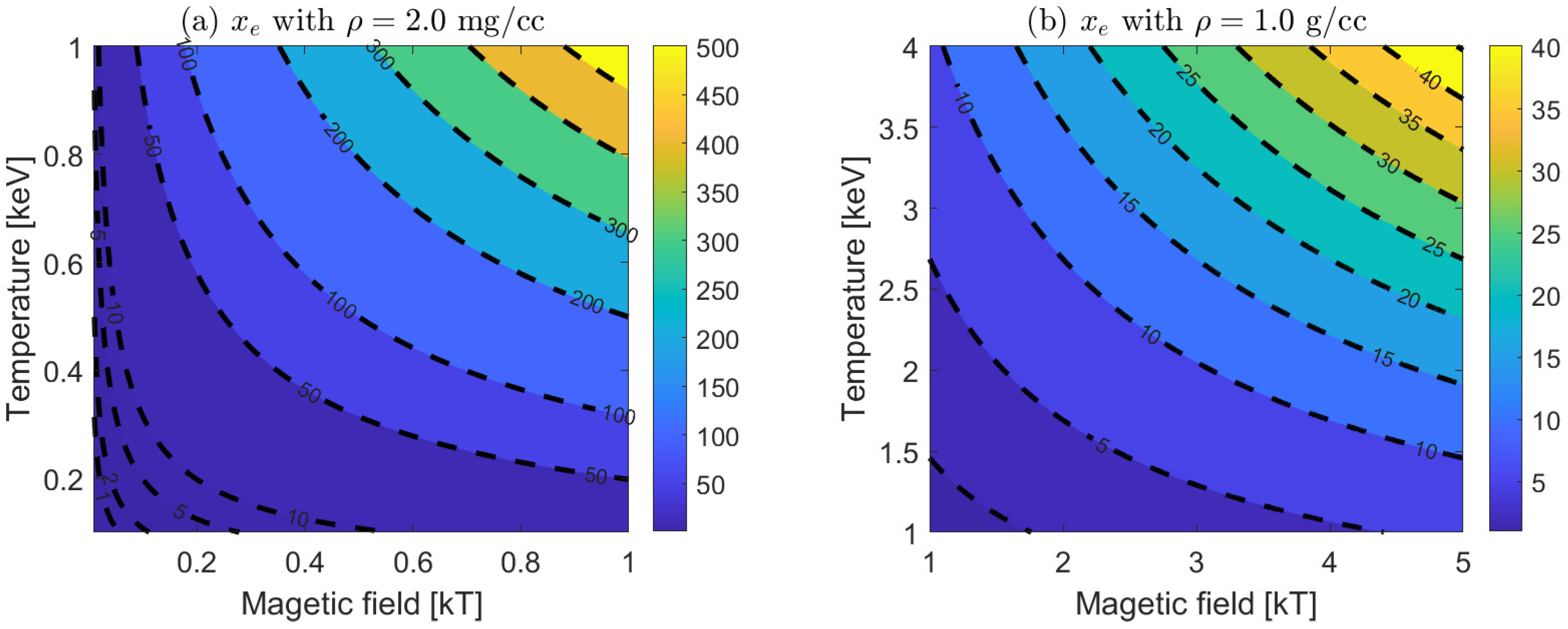

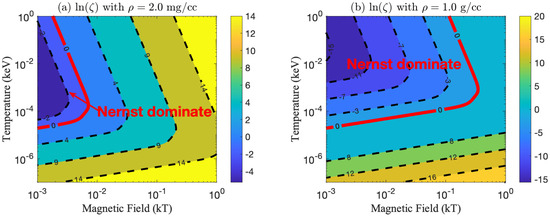

Two representative stages are considered: (a) the early compression phase, with , and (b) stagnation, where DT fuel reaches . Figure 3 shows the evolution of the dimensionless Hall parameter over the calculated B–T parameter space.

Figure 3.

Contour profile of the with varying magnetic field and temperature. (a) Plasma density corresponding to the initial fuel density ; (b) plasma density corresponding to the fuel density at stagnation.

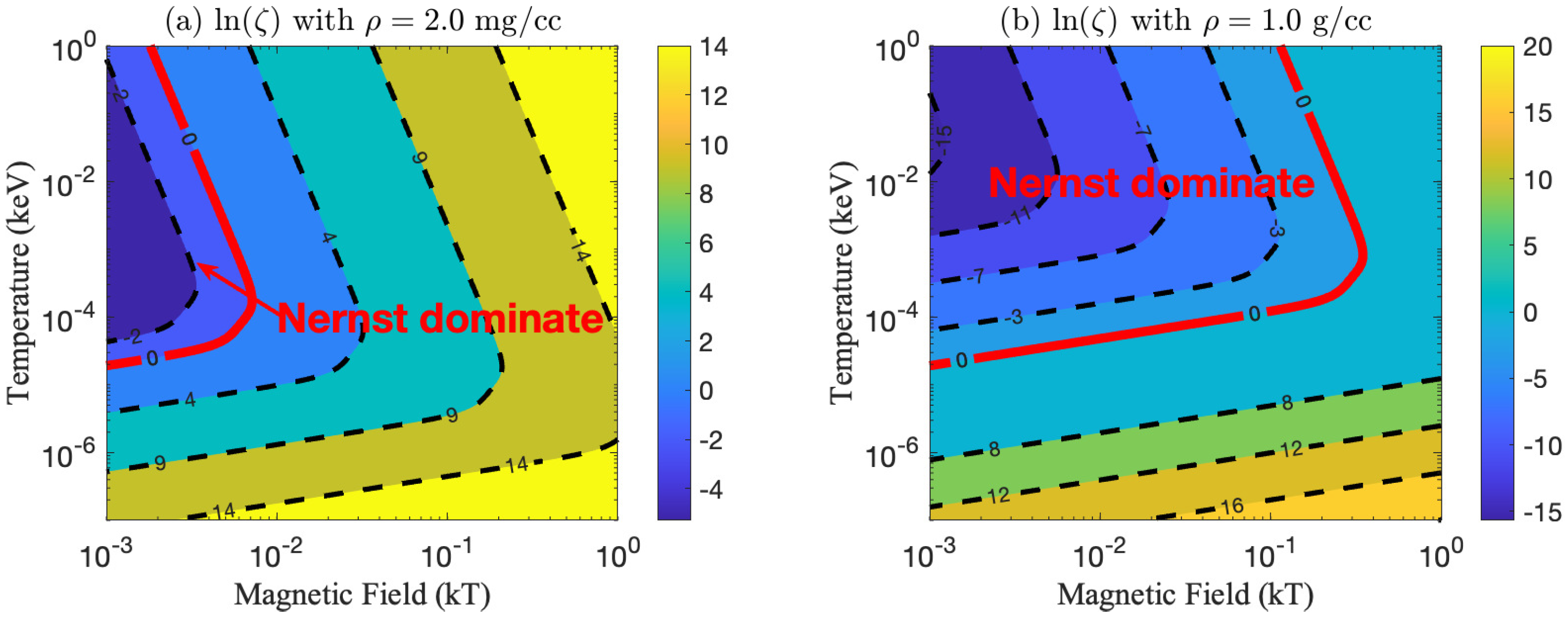

To assess the relative importance of diffusion versus Nernst effect, a non-dimensional expression is defined as , and is shown in Equation (18),

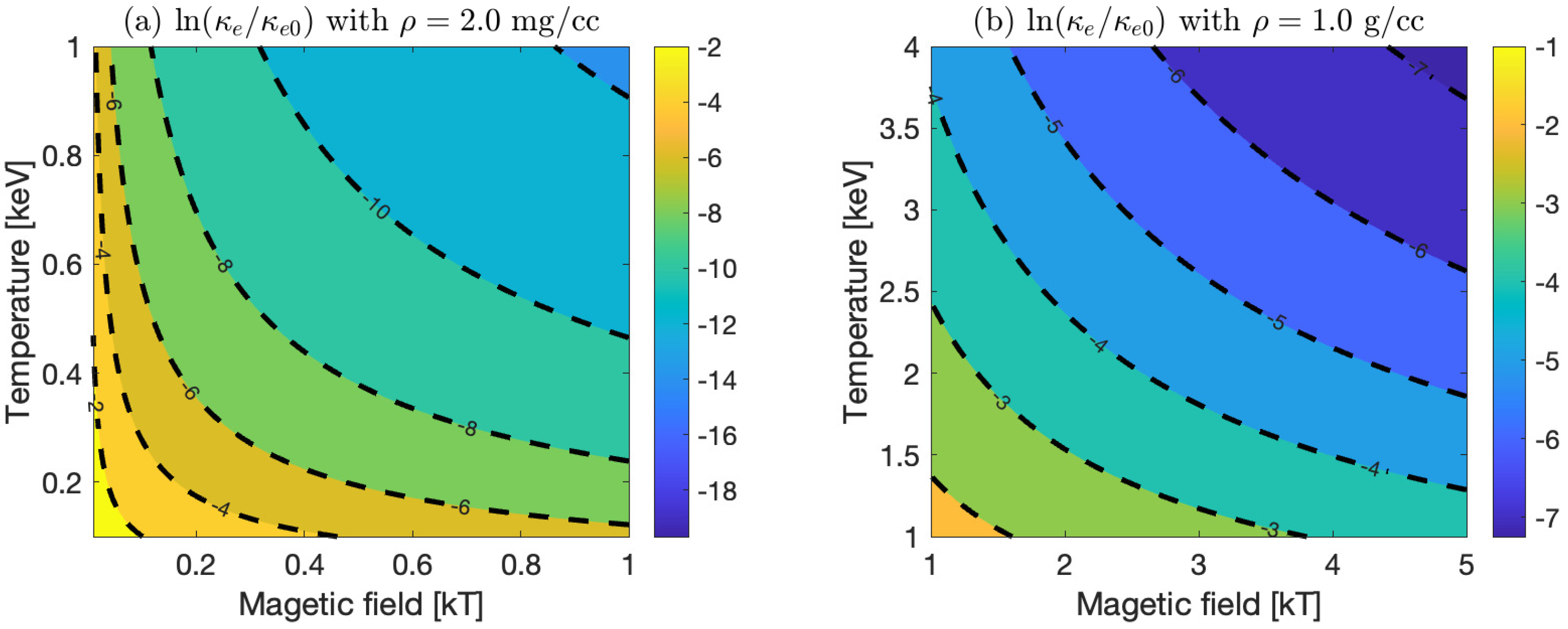

The non-dimensional number demonstrates that the thermal force has less effect on an extreme magnetization regime (). As illustrated in Figure 4, the number is not linearly related to the magnetic field B and temperature T, since the resistivity and thermoelectric coefficients depend on both B and T. Figure 4a shows the case for a typical initial fuel density of , while Figure 4b shows the case for a compressed fuel density. The magnitude for the non-dimensional number can be estimated within the scaled laser-driven MagLIF plasma parameter space. The dark blue region in Figure 4 corresponds to the Nernst-effect-dominated region. Whether in the initial or compressed state, the Nernst effect is important in a weakly magnetized regime. By estimating the dimensionless number , the Nernst effect influences the entire compression process of MagLIF, particularly in the relatively weakly magnetized region, such as the whole fuel in the early stages of compression and the fuel edge in the stagnation time.

Figure 4.

Contour profile of the with varying magnetic field and temperature. (a) Plasma density corresponding to the initial fuel density ; (b) Plasma density corresponding to the fuel density at stagnation. The region (the darker-shaded zone within the red boundary) indicates , where is the Nernst effect larger than the frictional effect.

2.5. Energy Coupling

In a magnetized target, the applied magnetic field serves several purposes, most notably suppressing electron thermal conduction. The field-dependent conductivity [33] is

with , . Figure 5 shows the normalized conductivity over the same B–T range considered previously. Here, is the unmagnetized conductivity at the same varing T with . In both early compression and stagnation, electron conductivity is significantly reduced by the applied field. Suppression is more pronounced at stagnation due to the higher density and stronger magnetization.

Figure 5.

Contour profile of the with varying magnetic field and temperature. (a) Plasma density corresponding to the initial fuel density ; (b) Plasma density corresponding to the fuel density at stagnation.

The potential role of Ohmic dissipation is estimated through the characteristic timescale for magnetic energy conversion into thermal energy:

where is plasma resistivity, is the permeability of free space, and is the current scale length. This timescale is independent of B for uniform fields and currents.

For laser-driven MagLIF, with compression times of ∼ ns, Ohmic heating is negligible: Spitzer resistivity gives ns≫ compression time. Thus, Joule heating contributes little to energy coupling at current scales. However, in larger targets with longer compression times, Ohmic dissipation could become significant, representing a direction for future investigation.

3. Simulation

Laser-driven MagLIF involves multiple coupled physical processes. A cylindrical parylene-N (CH) ablator filled with DT fuel is accelerated by laser drive. Fuel premagnetization and preheating reduce the required radial convergence, while the liner implodes and converts stored energy into radial kinetic energy, creating extreme plasma conditions at stagnation. The applied magnetic field reduces electron thermal conductivity and enhances -particle deposition, thereby facilitating ignition and burn. Integrated implosions are simulated here using the one-dimensional cylindrical radiation–magnetohydrodynamic code MULTI-IFE. Thermodynamic properties (e.g., pressures, energies) are modeled with the QEOS equation of state [31], and opacities are obtained from an atomic-physics-based opacity model [29].

The target consists of a parylene-N liner (, thickness mm, outer radius mm, length 10 mm), surrounding a DT fuel column of radius mm at an initial density of . The drive pulse, taken from Refs. [15,34], has a duration of ns. Three main steps in implosion are modeled:

1. Fuel magnetization: an initial axial field of 10 T is applied.

2. Preheating: the fuel is preheated to ∼200 eV prior to compression.

3. Compression: laser-driven ablation generates a radial implosion, coupling magnetic insulation with heat transport and -particle dynamics.

The reference parameters are summarized in Table 1. Laser drive refers to the laser energy delivered to the target by the beam. The laser is modeled using the WKB approximation at normal incidence. The target configuration was chosen with reference to the design employed in experiments conducted on the OMEGA facility. With ∼ lower energy, OMEGA requires a MagLIF target ∼ smaller than that on Z. The laser pulse shape, we will use a square-shaped pulse. The laser parameters employed correspond to a 440 nm wavelength. The initial magnetic field is 10 T. The radius of the inner fuel layer is 0.27 mm, while the thickness of the outer CH shell is 30 m.

Table 1.

Parameters of the reference laser-driven MagLIF target.

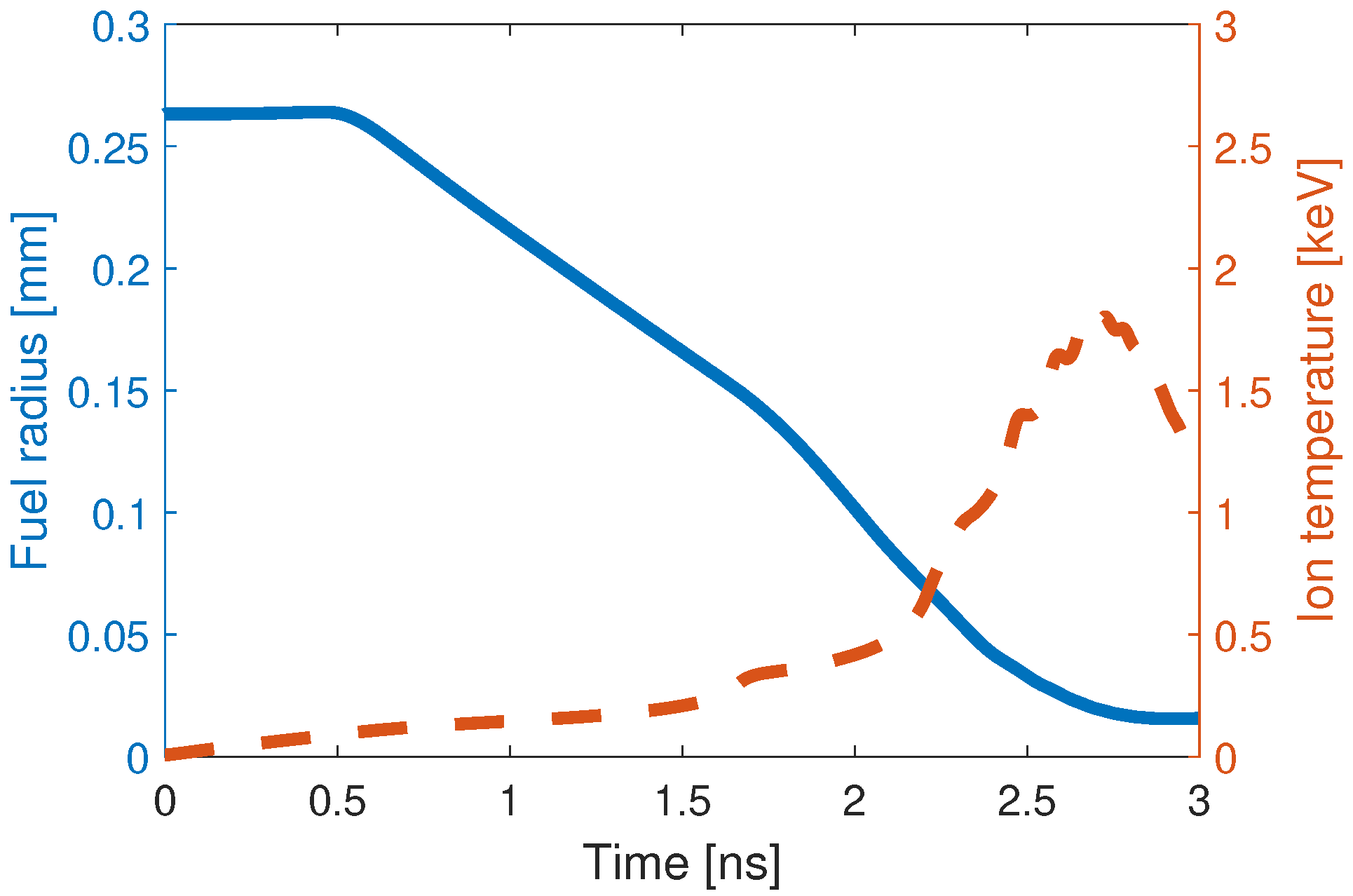

Ignition occurs when -heating exceeds radiative cooling, conductive losses, and work. With fuel premagnetization and preheating, thermal conductivity is reduced and the required convergence lowered. Figure 6 shows the evolution of fuel radius and mean ion temperature in the ideal magnetized case (only frozen-in-flow included). As shown in Figure 6, the first 0.5 ns corresponds to the preheating stage, during which the fuel is heated to a temperature of approximately 200 eV. This is followed by the implosion compression stage, which lasts for 1.5 ns. Compression proceeds until stagnation at ns, when the DT density reaches with a convergence ratio of 17. The corresponding neutron yield is ∼. Key performance metrics are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Evolution of fuel outer radius and mean ion temperature for a 30-m CH liner containing DT fuel ( mg/cc) under a 1.5 ns drive pulse with initial T.

Table 2.

Performance of the reference magnetized MagLIF implosion.

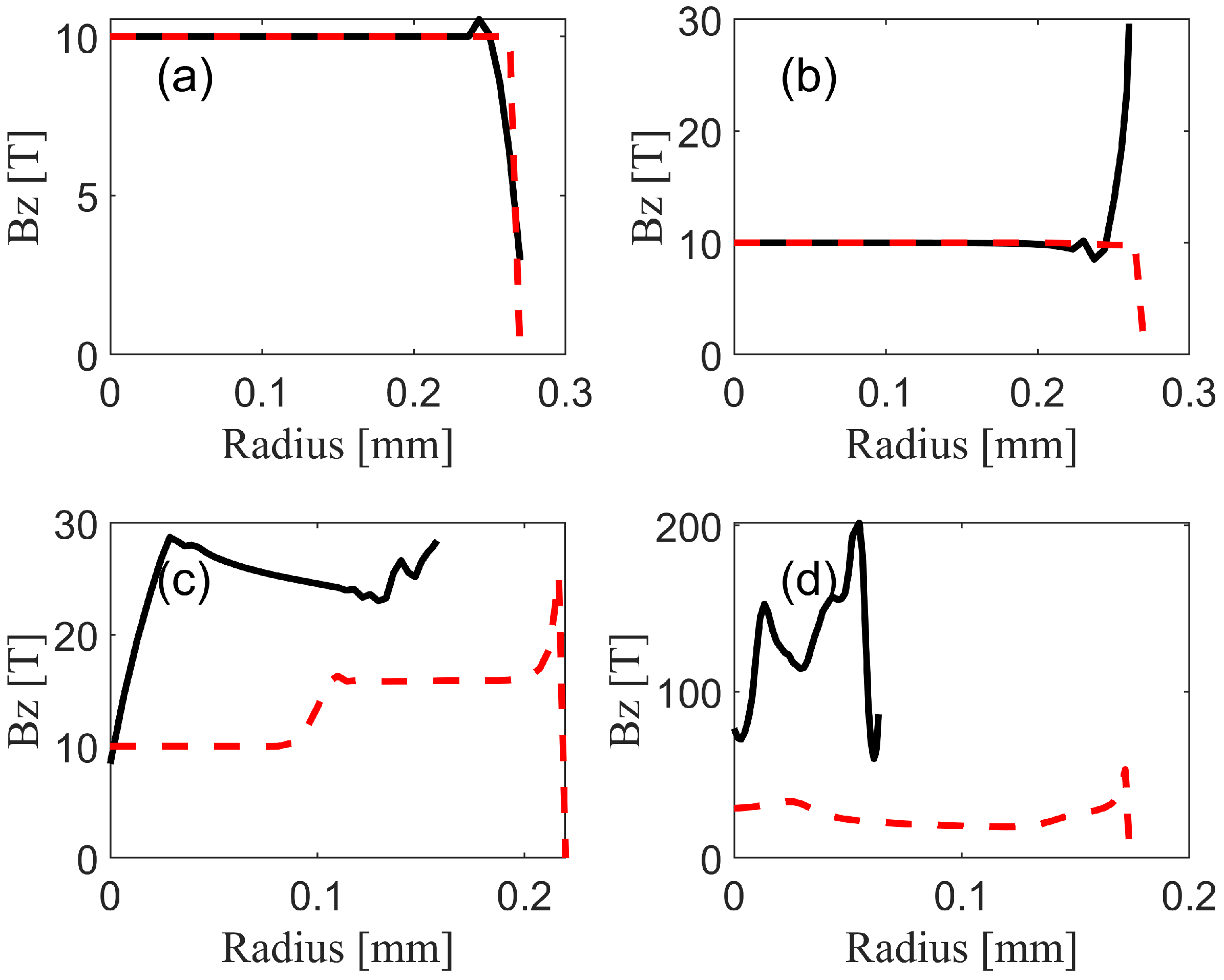

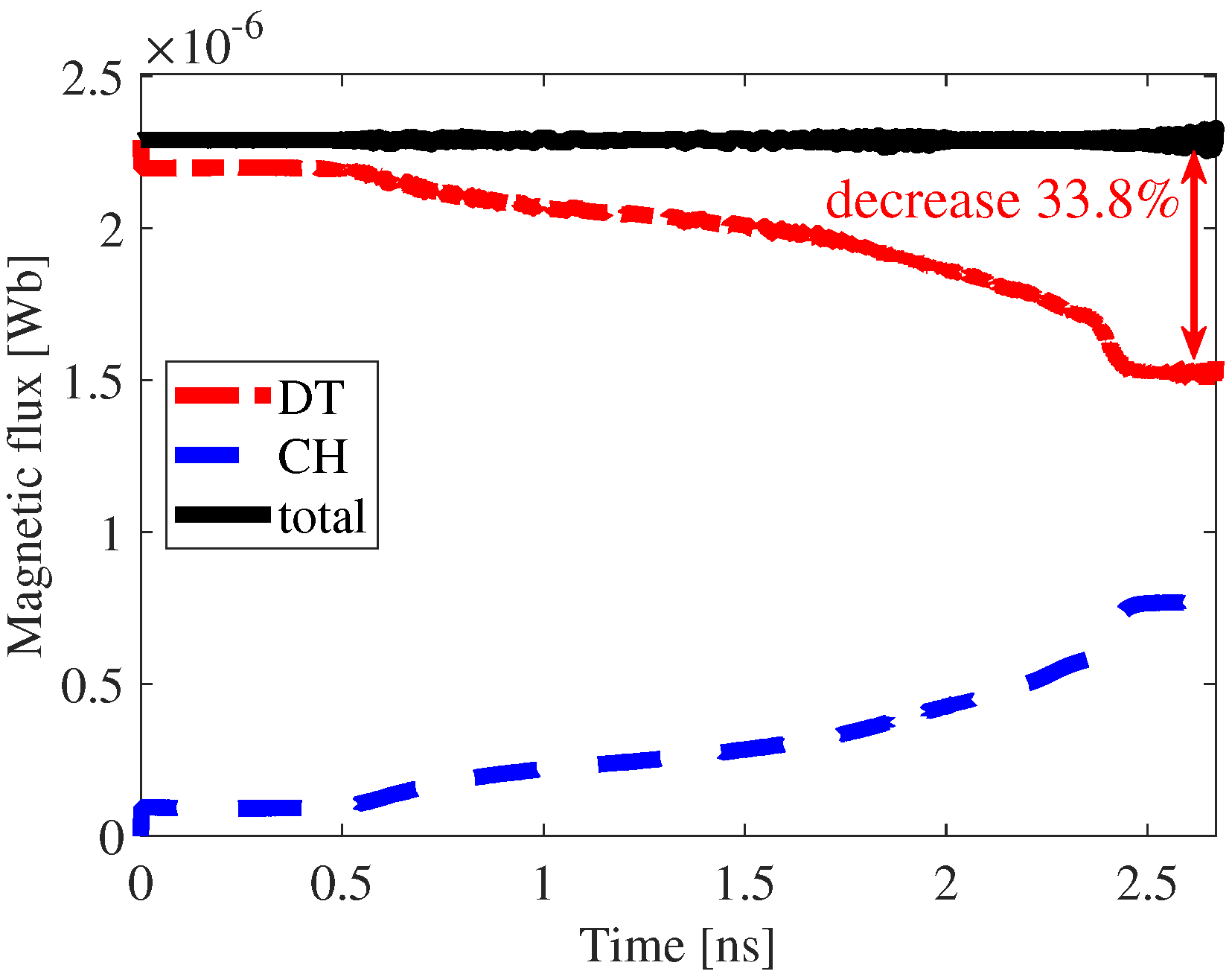

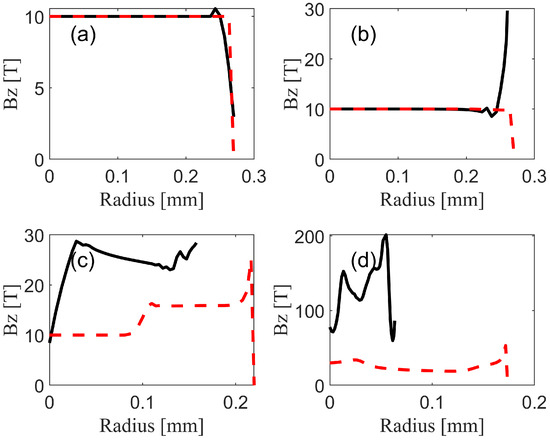

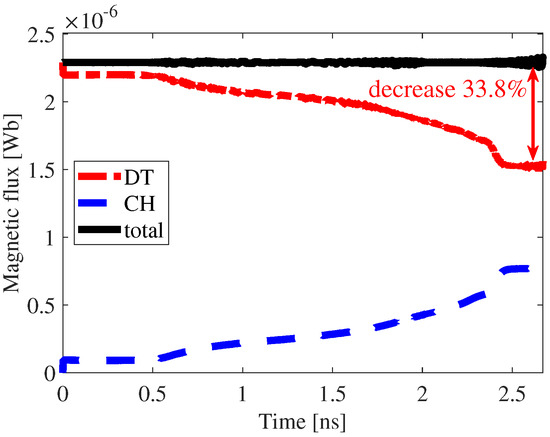

Figure 7 shows the evolution of the magnetic field in the fuel. The black curves represent cases that include the frozen-in, diffusion, and Nernst terms, while the red curves show, for comparison, the cases considering only the frozen-in term. The following describes the data corresponding to the black curve. At the early stage of the implosion (0.001 ns), as shown in Figure 7a, the Nernst and diffusion terms have already transported a portion of the magnetic field toward the boundary, resulting in a small peak. At 0.5 ns, the Nernst and diffusion terms transport the magnetic field toward the boundary, producing a cavitation near . At 1.0 ns, two magnetic peaks form at and : the outer peak results from accumulation near the CH shell due to the Nernst and diffusion terms, while the inner one is caused by shock-induced compression of the fuel, which amplifies the magnetic field through the frozen-in effect. As the shock moves inward, the inner peak shifts to at 1.5 ns. Figure 7 further demonstrates that magnetic flux diffusion reduces the magnetic field pressure and increases the convergence ratio. As shown in Figure 7b–d, the shock in the black curve is positioned closer to the central region than that in the red curve. Figure 8 shows the evolution of the magnetic flux in target. The magnetic flux evolves from an initial value of Wb to Wb by the time of stagnation (2.72 ns). The magnetic flux in the fuel near the metal layer (red curve) is reduced by approximately 33.8% compared to the frozen-in case (black curve in Figure 8), while magnetic flux loss occurs within the fuel, the consequent decrease in magnetic pressure and temperature enhances the overall compression, thereby reshaping the radial magnetic field distribution. The field becomes more tightly compressed, leading to a localized enhancement near the liner.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the magnetic field in the fuel with initial T. Panels (a–d) correspond to 0.01 ns, 0.5 ns, 1.0 ns, and 1.5 ns, respectively. The black curves represent cases that include the frozen-in, diffusion, and Nernst terms, while the red curves show, for comparison, the cases considering only the frozen-in term.

Figure 8.

Evolution of the magnetic flux in target. The black curves represent the total magnetic flux of the whole target. The red and blue curves (including the effects of frozen-in, diffusive, and Nernst terms) correspond to the magnetic flux in the fuel region and the outer CH liner shell, respectively.

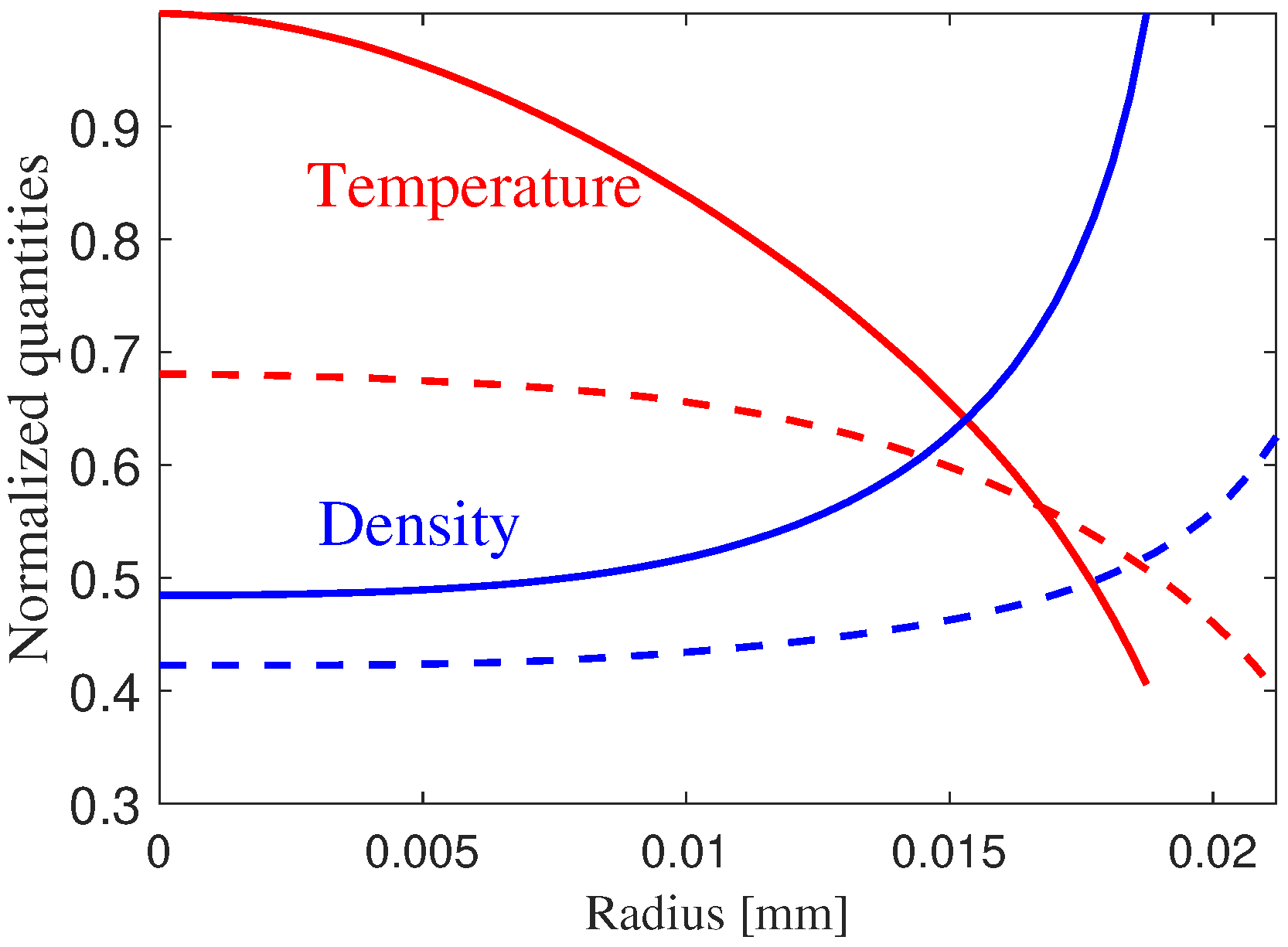

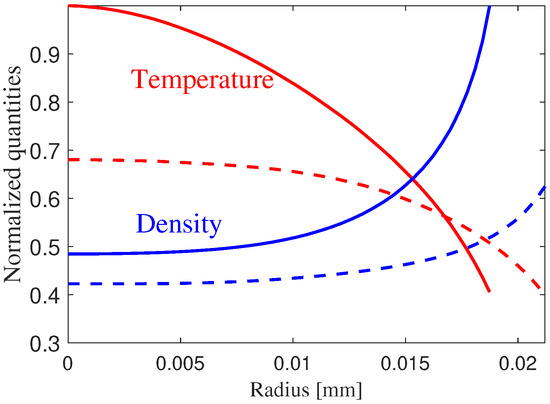

Figure 9 compares fuel profiles at stagnation for the magnetized ( T) and unmagnetized cases. Both exhibit density peaking near the stagnation radius and temperature peaking at the core. In the magnetized case, the core temperature is higher and the density distribution broader, reflecting reduced conduction and improved confinement, as well as a steeper gradient between core and edge. By contrast, the unmagnetized case suffers from stronger thermal losses, yielding a cooler core and flatter density spike. These differences highlight the role of magnetization in sustaining high core temperatures while moderating density gradients.

Figure 9.

Ion temperature and density profiles at peak neutron production for magnetized ( T) and unmagnetized cases. Dashed curves denote unmagnetized results. Ion temperature and density are normalized to 2.17 keV and 1.12 g/cc, respectively.

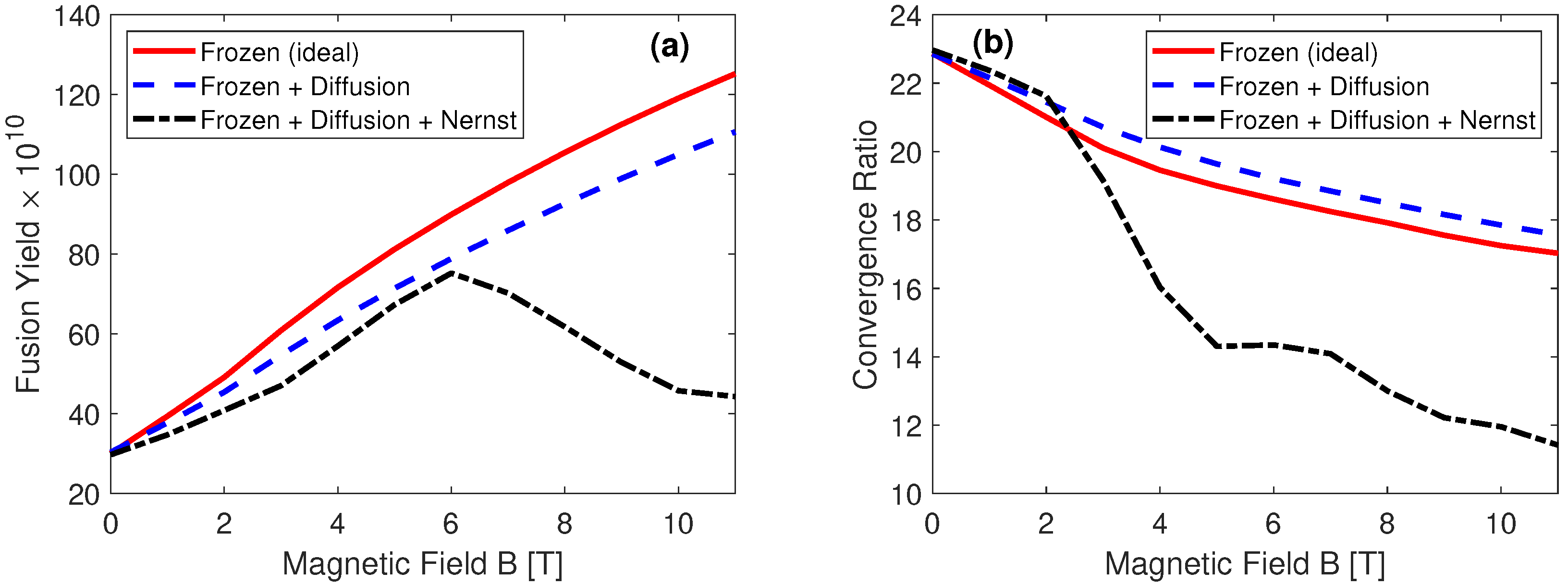

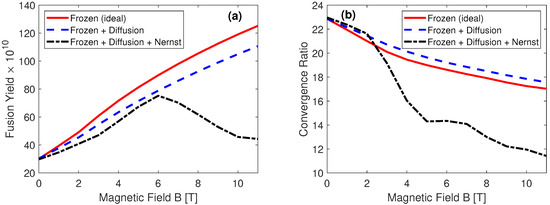

As shown in Figure 10a, in the ideal magnetization case (red curve) the yield increases steadily with field strength, reaching ∼ at T. Including diffusion (blue curve) slightly reduces the maximum yield to ∼. When the Nernst effect is added (green curve), the yield peaks at ∼ near T, roughly 2.5 times higher than the unmagnetized case, and then decreases at higher fields. This reduction stems from stronger Nernst advection at elevated temperatures and yields, which transports magnetic flux outward and diminishes central confinement. Figure 10b further shows that while convergence ratio rises monotonically with B in the ideal and diffusion cases, the yield in the Nernst case no longer follows this trend. This clearly demonstrates that magnetic flux transport by the Nernst effect undermines confinement and suppresses neutron production despite continued geometric compression.

Figure 10.

Neutron yield (a) and convergence ratio (b) as functions of initial axial magnetic field for different transport models.

In the absence of the Nernst term (frozen and frozen + diffusion models), both neutron yield and convergence ratio increase monotonically with the applied field, reflecting the beneficial role of magnetic insulation in suppressing conduction losses and enhancing confinement. When the Nernst effect is included (frozen + diffusion + Nernst model), the trend changes, while the convergence ratio deviates from the other models. This degradation arises from Nernst-driven flux transport away from the hot core, which weakens confinement and offsets the benefits of magnetization. These findings suggest that, although stronger fields (B∼11 T) would continue to benefit confinement in the absence of Nernst transport, the practical optimum shifts to T once Nernst losses are included. In practice, excessively high fields are further constrained by engineering considerations, since solenoids generating such fields obstruct diagnostic access in laser-driven experiments.

To distinguish the role of -particle heating, eight representative cases were simulated, varying the inclusion of magnetic terms, -particle feedback, and associated transport processes (Table 3). For clarity, in the “no ” cases the fusion reaction module is disabled in the numerical model, such that no fusion yield is produced. These cases therefore isolate the effects of transport physics alone.

Table 3.

Results for magnetic-field models with/without -particle deposition.

With -heating included, the frozen-in-flow model gives the highest yield ( cm−1) with keV, a convergence ratio of 17, and stagnation time of 2.72 ns. Adding diffusion reduces the yield slightly ( cm−1), while including both diffusion and the Nernst effect causes a sharp reduction to cm−1, despite a modest increase in peak temperature (2.25 keV). This illustrates that Nernst-driven magnetic flux loss out of the core is the dominant factor limiting confinement at high fields.

In the absence of -heating, all magnetized cases produce zero neutron yield, but still show elevated peak temperatures compared with the unmagnetized cases, underscoring the role of the applied magnetic field in suppressing conductive losses even without burn. Notably, when the Nernst effect is included without -heating, the peak temperature rises further (to 2.28 keV). This reflects the Nernst-driven redistribution of magnetic flux, which causes central magnetic field cavitation while depositing flux toward the outer regions, thereby steepening radial temperature gradients and enhancing edge heating. Across all magnetized cases, the stagnation time remains nearly constant at ∼ ns, whereas unmagnetized cases stagnate earlier (∼ ns). This indicates that stagnation duration is primarily governed by the applied magnetic field, while convergence ratio variations reflect changes in confinement quality.

4. Conclusions

The magnetic field influences on energy coupling in scaled, laser-driven magnetized liner inertial fusion are investigated. Magnetic field transport caused by the Nernst and diffusion effects modifies the energy coupling, prompting a parametric analysis to determine their role during the implosion phase. A one-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic model has also been used to investigate the role of applied magnetic fields in laser-driven MagLIF, with parameters scaled to conditions achievable on the laser facility.

The results show that as the temperature increases, the Nernst effect becomes progressively more dominant, at early compression stage ( mg/cc), than magnetic diffusion because of its strong dependence on the temperature gradient, and this dominance is further amplified at stagnation ( g/cc). The impact of Ohmic heating is minimal, as its characteristic timescale for converting magnetic energy into thermal energy is significantly longer than the approximately 2.5 ns implosion duration.

After establishing the importance of the Nernst effect, its influence during the implosion is further examined via numerical simulations. When the Nernst effect is included, the neutron yield decreases by 57.3% as magnetic flux is transported out of the hot core. With an initial field strength of 10 T, stagnation is achieved at 2.72 ns with a peak temperature of 2.17 keV and a neutron yield of . The final on-axis fuel density reaches 1.19 g/cc, corresponding to a convergence ratio of = 17. During the implosion, the magnetic field in the fuel region gradually diffuses outward into the outer liner, leading to a total magnetic flux loss of 33.8% at stagnation. A parametric sweep of the initial magnetic field strength identifies an optimized field of approximately 6 T, yielding about 2.5 times higher neutron output than the unmagnetized case.

For scaled MagLIF, energy loss processes in the fuel plasma are of central importance to fusion performance. The evolution of the magnetic field can be understood in terms of three key mechanisms: frozen-in convection with the bulk plasma flow, resistive diffusion due to electron collisions, and Nernst advection driven by electron heat flux. Together, these processes determine the coupling between magnetic fields and electron thermal transport, and thereby affect both Joule heating and the spatial distribution of -particle energy deposition. The redistribution of magnetic flux, particularly by the Nernst effect, alters radial confinement profiles and modifies the neutron yield. These results provide guidance for the design of scaled laser-driven MagLIF targets, emphasizing that field optimization is critical to maximizing neutron output.

The present work is limited to one-dimensional simulations, which do not account for instabilities and other effects that may influence the implosion performance. In future work, we plan to extend the simulations to two dimensions to provide a more comprehensive analysis.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.C., L.C., Y.S., R.C., J.Y., L.Y. and Z.S.; Software, X.F. and S.C.; Formal analysis, X.F.; Investigation, H.Z., S.C. and L.C.; Writing—original draft, X.F., G.L. and S.C.; Writing—review & editing, X.F., G.L., H.Z., S.C., L.C., Y.S., R.C., J.Y., L.Y. and Z.S.; Funding acquisition, H.Z., S.C., L.C., R.C. and J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2023YFA1608403 and 2022YFA1602500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12205200, 12375237, and U2430208), and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Grant No. RCBS20221008093131086).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study.

References

- Cuneo, M.E.; Herrmann, M.C.; Sinars, D.B.; Slutz, S.A.; Stygar, W.A.; Vesey, R.A.; Sefkow, A.B.; Rochau, G.A.; Chandler, G.A.; Bailey, J.E.; et al. Magnetically driven implosions for inertial confinement fusion at Sandia National Laboratories. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2012, 40, 3222–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemuth, I.R.; Kirkpatrick, R.C. Parameter space for magnetized fuel targets in inertial confinement fusion. Nucl. Fusion 1983, 23, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemuth, I.R.; Widner, M.M. Magnetohydrodynamic behavior of thermonuclear fuel in a preconditioned electron beam imploded target. Phys. Fluids 1981, 24, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutz, S.A.; Herrmann, M.C.; Vesey, R.A.; Sefkow, A.B.; Sinars, D.B.; Rovang, D.C.; Peterson, K.J.; Cuneo, M.E. Pulsed-power-driven cylindrical liner implosions of laser preheated fuel magnetized with an axial field. Phys. Plasmas 2010, 17, 056303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, C.; Ma, Y.; Ramis, R. A two-layer single shell magnetized target for lessening the Nernst effect. Nucl. Fusion 2024, 64, 066027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, R.; Zhou, C. High-density and high-ρR fuel assembly for fast-ignition inertial confinement fusion. Phys. Plasmas 2005, 12, 110702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.Y.; Fiksel, G.; Hohenberger, M.; Knauer, J.P.; Betti, R.; Marshall, F.J.; Meyerhofer, D.D.; Séguin, F.H.; Petrasso, R.D. Fusion yield enhancement in magnetized laser-driven implosions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 035006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.E.; LeChien, K.R.; Lopez, M.R.; Stoltzfus, B.S.; Stygar, W.A.; Lott, J.A.; Corcoran, P.A. Status of the Z pulsed power driver. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Pulsed Power Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 19–23 June 2011; pp. 983–990. [Google Scholar]

- Basko, M.M.; Kemp, A.J.; Meyer-ter-Vehn, J. Ignition conditions for magnetized target fusion in cylindrical geometry. Nucl. Fusion 2000, 40, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager-Elorriaga, D.A.; Gomez, M.R.; Ruiz, D.E.; Slutz, S.A.; Harvey-Thompson, A.J.; Jennings, C.A.; Knapp, P.F.; Schmit, P.F.; Weis, M.R.; Awe, T.J.; et al. An overview of magneto-inertial fusion on the Z machine at Sandia National Laboratories. Nucl. Fusion 2022, 62, 042015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutz, S.A.; Vesey, R.A. High-gain magnetized inertial fusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.R.; Slutz, S.A.; Sefkow, A.B.; Sinars, D.B.; Hahn, K.D.; Hansen, S.B.; Harding, E.; Knapp, P.; Schmit, P.; Jennings, C.; et al. Experimental demonstration of fusion-relevant conditions in magnetized liner inertial fusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 155003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.V.; Welch, D.R.; Madrid, E.A.; Miller, C.L.; Clark, R.E.; Stygar, W.A.; Savage, M.E.; Rochau, G.A.; Bailey, J.E.; Nash, T.J.; et al. Three-dimensional electromagnetic model of the pulsed-power Z-pinch accelerator. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Accel. Beams 2010, 13, 010402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.R.; Slutz, S.A.; Jennings, C.A.; Ampleford, D.J.; Weis, M.R.; Myers, C.E.; Yager-Elorriaga, D.; Hahn, K.; Hansen, S.; Harding, E.; et al. Performance Scaling in Magnetized Liner Inertial Fusion Experiments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 155002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.R.; Barnak, D.H.; Betti, R.; Campbell, E.M.; Chang, P.Y.; Sefkow, A.B.; Peterson, K.J.; Sinars, D.B.; Weis, M.R. Laser-driven magnetized liner inertial fusion. Phys. Plasmas 2017, 24, 062703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnak, D.H.; Davies, J.R.; Betti, R.; Bonino, M.J.; Campbell, E.M.; Glebov, V.Y.; Harding, D.R.; Knauer, J.P.; Regan, S.P.; Sefkow, A.B.; et al. Laser-driven magnetized liner inertial fusion on OMEGA. Phys. Plasmas 2017, 24, 056310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.C.; Barnak, D.H.; Betti, R.; Campbell, E.M.; Chang, P.Y.; Davies, J.R.; Glebov, V.Y.; Knauer, J.P.; Peebles, J.; Regan, S.P.; et al. Measuring implosion velocities in experiments and simulations of laser-driven cylindrical implosions on the OMEGA laser. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2018, 60, 054014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.R.; Bahr, R.E.; Barnak, D.H.; Betti, R.; Bonino, M.J.; Campbell, E.M.; Hansen, E.C.; Harding, D.R.; Peebles, J.L.; Sefkow, A.B.; et al. Laser entrance window transmission and reflection measurements for preheating in magnetized liner inertial fusion. Phys. Plasmas 2018, 25, 062708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.R.; Barnak, D.H.; Betti, R.; Campbell, E.M.; Glebov, V.Y.; Hansen, E.C.; Knauer, J.P.; Peebles, J.L.; Sefkow, A.B. Inferring fuel areal density from secondary neutron yields in laser-driven magnetized liner inertial fusion. Phys. Plasmas 2019, 26, 022705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.C.; Davies, J.R.; Barnak, D.H.; Betti, R.; Campbell, E.M.; Glebov, V.Y.; Knauer, J.P.; Leal, L.S.; Peebles, J.L.; Sefkow, A.B.; et al. Neutron yield enhancement and suppression by magnetization in laser-driven cylindrical implosions. Phys. Plasmas 2020, 27, 062701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Xia, J.W.; Xiao, G.Q.; Xu, H.S.; Sheng, L.N. High intensity heavy ion accelerator facility (hiaf) in china. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 2013, 317, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortov, V.E.; Hoffmann, D.H.; Sharkov, B.Y. Intense ion beams for generating extreme states of matter. Physics-Uspekhi 2008, 51, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basko, M.M. Magnetized implosions driven by intense ion beams. Phys. Plasmas 2000, 7, 4579–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosilevskiy, I. Heavy Ion Beams for Investigation of Thermophysical Properties. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1005.4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutz, S.A. Scaling of magnetized inertial fusion with drive current rise-time. Phys. Plasmas 2018, 25, 082706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutz, S.A.; Stygar, W.A.; Gomez, M.R.; Peterson, K.J.; Sefkow, A.B.; Sinars, D.B.; Vesey, R.A.; Campbell, E.M.; Betti, R. Scaling magnetized liner inertial fusion on Z and future pulsed-power accelerators. Phys. Plasmas 2016, 23, 022702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramis, R.; Meyer-ter-Vehn, J. MULTI-IFE—A one-dimensional computer code for Inertial Fusion Energy (IFE) target simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2016, 203, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Ma, Y.Y.; Wu, F.Y.; Yang, X.H.; Yuan, Y.; Cui, Y.; Ramis, R. Simulations on the multi-shell target ignition driven by radiation pulse in Z-pinch dynamic hohlraum. Chin. Phys. B 2021, 30, 115201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, G.D.; Eidmann, K. An approximate method for calculating Planck and Rosseland mean opacities in hot, dense plasmas. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 1987, 38, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramis, R.; Schmalz, R.; Meyer-ter-Vehn, J. MULTI—A computer code for one-dimensional multigroup radiation hydrodynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1988, 49, 475–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, A.J.; Meyer-ter-Vehn, J. An equation of state code for hot dense matter, based on the QEOS description. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 1998, 415, 674–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, F.; Abril, R.R.; Ma, Y.; Zhuo, H.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, H. A radiation MHD algorithm with Nernst effect for magnetized liner inertial fusion simulations. Phys. Plasmas 2025, 32, 082706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikovich, A.L.; Giuliani, J.L.; Zalesak, S.T. Magnetic flux and heat losses by diffusive, advective, and Nernst effects in magnetized liner inertial fusion-like plasma. Phys. Plasmas 2015, 22, 042702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.R.; Betti, R.; Chang, P.Y.; Fiksel, G. The importance of electrothermal terms in Ohm’s law for magnetized spherical implosions. Phys. Plasmas 2015, 22, 112703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).