Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a major cause of skin aging, leading to oxidation and cleavage of collagen that supports skin structure. Previous studies have demonstrated that Magnolia officinalis var. officinalis (M. officinalis) dry extract reduces mitochondria-enriched ROS production and improves senescence-related phenotypes in vitro. However, its effects on human skin aging have not been investigated. In this study, we conducted both in vitro and clinical trials using an M. officinalis liquid extract, which can be directly applied to cosmetic formulations. The M. officinalis liquid extract restored mitochondrial function and reduced mitochondria-enriched ROS production. Furthermore, M. officinalis liquid extract activated mitophagy, which removes defective mitochondria, a major source of ROS production. In clinical trials, the M. officinalis liquid extract reduced the mean depth of neck wrinkles by 12.73% and the maximum depth by 17.44%. It also reduced the mean roughness (Ra), root mean square roughness (Rq), and maximum depth of roughness (Rmax) by 12.73%, 10.16%, and 10.81%, respectively. Furthermore, the key to the skin-improving effects of M. officinalis liquid extract lies in its ability to increase skin elasticity by 3.76% and brighten skin tone by 0.76%. In conclusion, this study identified a novel mechanism by which M. officinalis liquid extract rejuvenates skin aging. M. officinalis can be utilized as a cosmetic ingredient to improve skin aging and therapeutic candidate for the development of anti-aging treatments.

1. Introduction

Cellular senescence is a process characterized by the permanent cessation of cell division and the decline in organelle function. Mitochondria, one of these organelles, undergo structural changes with senescence, increasing in size and volume while decreasing in function [1]. Specifically, mitochondrial dysfunction induces electron leakage from the electron transport chain (ETC), generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) [2]. Excessive ROS production in mitochondria induces a detrimental cycle that further damages mitochondria [2]. Thus, excessive ROS damages the structure and function of organelles other than mitochondria, ultimately leading to senescence [3]. While controlling ROS generation in mitochondria is recognized as crucial for senescence rejuvenation, effective methods to control ROS formation have not yet been identified, and further research in this area is needed.

The skin, the outermost organ of the body, consists of the epidermis, composed of epithelial tissue, and the dermis, composed of connective tissue [4]. Collagen, a protein that makes up about 90% of the dermal layer, is essential for providing a structural framework and contributing to the skin’s shape and elasticity [5]. A prominent aspect of skin aging is collagen loss, leading to skin wrinkles [6]. Although several factors are known to cause skin aging, mitochondrial dysfunction is considered the main cause of skin aging. Specifically, mitochondrial dysfunction leads to excessive production of mitochondrial ROS, which in turn activates collagen-degrading enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases, thereby promoting the breakdown of collagen [7,8]. Excessive levels of ROS also promote oxidative damage to collagen, leading to destabilization and breakdown of collagen–elastin fiber assemblies in the dermal extracellular matrix [8]. For example, vitamin C, an antioxidant that reduces free radical production, protects collagen in skin tissues, thereby maintaining skin elasticity [9]. Niacinamide, a form of vitamin B3, is an antioxidant that protects the skin from free radical damage and improves skin texture [10]. Antioxidant–based approaches have been used as a key strategy to improve skin aging, and further research in this area will help promote skin health.

Magnolia officinalis var. officinalis (M. officinalis) is distributed in East Asia, with significant populations in China, Japan, and Korea. M. officinalis has been widely used in traditional Chinese medicine due to its well-known anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties [11]. While many plant extracts are known to possess antioxidant or anti-aging properties, M. officinalis stands out from these common free radical scavengers by its ability to reduce mitochondrial ROS in addition to scavenging ROS inside and outside the cell [12]. M. officinalis’s ability to reduce mitochondrial ROS plays a key role in restoring mitochondrial function and enhancing its rejuvenating effects [12]. Furthermore, the key active ingredients of M. officinalis (e.g., magnolol and honokiol) modulate several senescence-related pathways, including nuclear factor kappa B and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, suggesting broad potential for controlling the underlying causes of senescence [13,14]. These properties suggest that M. officinalis may offer a mechanism of action advantage over conventional antioxidants, which primarily act as direct free radical scavengers.

Mitophagy offers a unique advantage in that it provides precise and selective quality control for mitochondria [15]. Unlike conventional autophagy, which degrades entire cellular components, mitophagy selectively removes only dysfunctional mitochondria. Mitophagy is a key mechanism for maintaining mitochondrial function and homeostasis. Furthermore, by timely removing dysfunctional mitochondria, it prevents cell death by blocking the release of harmful stress signals and apoptotic factors [15]. Given these cellular roles, the regulation of mitophagy may be an effective strategy to restore mitochondrial function.

The use of natural products in cosmetics is increasing due to their minimal adverse effects on the human skin [16]. To be used as cosmetic ingredients, natural products are manufactured in dry or liquid form through processes such as cold pressing, carbon dioxide extraction, steeping, infiltration, and solvent extraction. Each extract is diluted to a sufficient amount to provide the intended effects, such as moisturizing, anti-aging, or antioxidant effects, before being added to cosmetic formulations. Among these extracts, liquid extracts are preferred over dry extracts in cosmetic formulations because they can be added directly to cosmetic formulations without prior dissolution [17]. Furthermore, liquid extracts are manufactured using standardized manufacturing protocols, maintaining a consistent concentration of active ingredients, reducing variation in cosmetic production compared to dry extracts [18]. For example, liquid extracts are mixed in various cosmetic bases at concentrations ranging from 0.1% to 3%.

One tool for identifying mitochondrial ROS is dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123). Rhodamine 123, a fluorescent dye that selectively stains mitochondria, is reduced to create DHR123 [19]. Cationic rhodamine 123, which is employed to quantify mitochondrial ROS, is produced when DHR123 binds to mitochondrial hydroxyl radicals. However, DHR123 is also susceptible to nonspecific oxidation by various ROS and may respond to ROS other than mitochondrial ROS. Therefore, another mitochondria-specific dye, MitoSOX, was designed to detect mitochondrial ROS. MitoSOX is composed of a superoxide anion-sensitive dihydroethidium compound attached to a triphenylphosphonium moiety found in the mitochondrial matrix [20]. MitoSOX quantifies mitochondrial ROS by binding to superoxide anions in the mitochondrial matrix and oxidizing to a cationic dihydroethidium complex.

This study was conducted to determine whether M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in improving skin aging. M. officinalis liquid extract reduced the production of ROS in mitochondria, thereby exhibiting anti-aging effects on human skin. This study presents a novel mechanism by which M. officinalis liquid extract rejuvenates skin aging, and this could be utilized as a new approach for treating it.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

The cell lines presented in Table 1 were used in the experiments. Human dermal fibroblasts were serially passaged in the medium and culture conditions presented in Table 1. At each passage, cell counts were measured using a Cedex HiRes Analyzer (05650216001; Roche, Basel, Switzerland), which was used to calculate the population doubling time (PD). Based on PD measurements, cells exhibiting a PD greater than 14 days were classified as senescent fibroblasts, whereas cells with a PD of less than 2 days were classified as young fibroblasts, as previously reported [21].

Table 1.

Information about the cell line.

2.2. Preparation of M. officinalis Liquid Extract

The bark of M. officinalis (Pure Mind, Yeongcheon, Republic of Korea) was extracted by refluxing with 70% ethanol at 60 °C for 3 h at a solid-to-solvent ratio of 1:8 (w/v). A 5 μm filter was used to filter the extract first, followed by a 0.45 μm filter. Butylene glycol (Amorepacific Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to dissolve the filtrate. The mixture was then concentrated at 60 °C. Polyglyceryl–10 oleate (Taiyo Kagaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was added to the concentrate in a volume ratio of 8:2. After stirring at 80 °C for 30 min, the mixture was diluted fivefold with filtered water. 1,2–Hexanediol (SHD62; SHINSUNG Composites, Jincheon, Republic of Korea) was added to the dilution to a final concentration of 2%. The final mixture was sterilized using a 0.22 μm syringe filter (S25LT022AP1HN–B1H; Hyundai Micro Co., Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea). For in vitro testing, the filtrate was diluted in medium to concentrations of 0.03%, 0.05%, and 0.1%.

2.3. Preparation of a Cream Containing M. officinalis Liquid Extract

For the clinical test, the cream base contained purified water, butylene glycol, glycerin, cyclohexasiloxane, cyclopentasiloxane, cetearyl alcohol, cetearyl glucoside, cetyl ethylhexanoate, betaine, 1,2-hexanediol, sodium acrylate/acryloyldimethyltaurate copolymer, isohexadecane, polysorbate 80, β-glucan, sodium hyaluronate, polysorbate 60, glyceryl stearate, PEG–100 stearate, tocopheryl acetate, lavender oil, allantoin, xanthan gum, and disodium EDTA. A cream without M. officinalis liquid extract was used as a vehicle group, and a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) was applied to the test group.

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis of ROS, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP), Autophagy Flux, Mitochondrial Mass and Autofluorescence

Senescent fibroblasts were treated with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, and 0.1%) at 4–day intervals for 12 days. Flow cytometric analysis for ROS, MMP, mitochondrial mass, and autofluorescence was performed according to the conditions in Table 2. Specifically, autofluorescence was measured by incubating cells in dye-free medium for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by detection using the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) channel (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 525 nm). Autophagy flux was measured according to the following procedure. Senescent fibroblasts were cultured overnight at 37 °C in medium containing 20 µM chloroquine (CQ; C6628; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Then, the senescent fibroblasts were exposed to CYTO–ID®–containing medium (ENZ–51031–0050; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) at 37 °C for 30 min. [Cyto–ID® FITC mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (with CQ)—Cyto–ID® unstained FITC MFI (with CQ)]—[Cyto–ID® stained FITC MFI (without CQ)—Cyto–ID® unstained FITC MFI (without CQ)] is autophagic flux.

Table 2.

Flow cytometry conditions.

2.5. Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) and Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) Analysis

An XFe96 flux analyzer (Aglient Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to examine OCR and ECAR. The Seahorse XF Mito Stress Kit (103015–100; Aglient Technology) and the Seahorse XF Glycolytic Rate Assay Kit (103344–100; Aglient Technology) were used to measure OCR and ECAR, respectively. OCR and ECAR analyses were performed according to the company protocol.

2.6. Fluorescence Analysis of Mitophagy

Immunofluorescence was carried out under the guidelines listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Immunofluorescence conditions.

2.7. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

qPCR was carried out as previously mentioned [22]. Table 4 shows the information about primers.

Table 4.

Sequence information of primers used in qPCR.

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

The protocol outlined in Table 5 was followed while performing the Western blot analysis. Image J (Version 1.54p, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to evaluate the Western blot quantitatively.

Table 5.

Western blot conditions.

2.9. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis

The honokiol and magnolol content of the M. officinalis liquid extract was analyzed using HPLC (Agilent 1200, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The HPLC column utilized was a Capcell Pak C18 4.6 × 250 mm column (a Shiseido, Osaka, Japan). Methanol was used to dilute the M. officinalis liquid extract to a concentration of 1 mg/mL. 50 mL methanol was used to dissolve either 4.0 mg honokiol (42612; Sigma) or 3.5 mg magnolol (Y0001289; Sigma) to create a standard solution.

2.10. Clinical Trials

For the clinical experiment, twenty-one Korean women (mean age 56.86 ± 4.94 years) took part. The clinical trial protocol (approval number: DEF-HAAET070(1)-25087) was authorized by Dermapro Co., Ltd.’s Institutional Review Board in Seoul, Republic of Korea. The clinical trial protocol was registered with the Clinical Trial Information Service of the National Institute of Health, Republic of Korea (KCT00100008). The clinical trial protocol was performed in accordance with Dermapro Co., Ltd.’s standard operating procedures and good clinical practice. The period of the clinical trial was from 7 April 2025 to 16 May 2025. The subject selection process excluded participants having skin abnormalities in the test area, such as spots, acne, erythema, or telangiectasia. Written consent for participation was obtained prior to the clinical trial’s commencement. Participants were informed of its goal and procedures. To objectively assess efficacy, the clinical trial was designed using randomized, double-blind methods. Specifically, randomization was performed using methods such as block randomization to assign subjects to different treatment groups without bias. Moreover, the double-blind method ensured that neither the investigators nor the participants knew which product was being administered. For 4 weeks, participants applied a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) twice daily, in the morning and the evening. Participants were given 20 min to acclimate in a controlled setting with a temperature of 22 °C ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 50 ± 5% before the measurements. During the 4-week period, no tolerance and adverse effects were observed in participants who received the vehicle cream or the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%).

2.11. Measurement of Neck Wrinkles

Neck wrinkles were measured using ANTERA® CS (Miravex Limited, Dublin, Ireland). Two-dimensional or three-dimensional image analysis was performed in the same area at the start of treatment and 4 weeks later to determine wrinkle depth. Images of the left and right neck areas were taken, and wrinkle patterns (depth and maximum depth) were analyzed.

2.12. Measurements of Skin Elasticity

A cutometer (MPA580; Courage and Khazaka Electronic, Cologne, Germany) was used to assess the elasticity of the skin. The measurement’s basic concepts are suction and extension. The apparatus pulls the skin in the direction of the probe hole while maintaining a steady negative pressure of 450 mbar for two seconds. After that, the negative pressure is stopped for two seconds to give the skin time to regain its natural contour. The onset/onset cycle is repeated three times for every measurement cycle. The left and right cheeks were used to test the suppleness of the skin.

2.13. Measurements of Skin Texture

Skin texture was measured with an atomic force microscope (Veeco, Plainview, NY, USA). The cheek areas on both sides were measured. Mean roughness (Ra), root mean square roughness (Rq), and maximum depth of roughness (Rmax) were analyzed following the previous study [23].

2.14. Measurements of Skin Complexion

Skin complexion was measured with a spectrophotometer® CM–2500d (Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). The cheek areas on both sides were measured. Skin brightness (L* value) was analyzed following the previous study [24].

2.15. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using an IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Student’s t-test, two–way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, RM-ANOVA, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to examine variability between parametric data sets. Specifically, when a significant main effect was detected in RM-ANOVA, post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni correction method to correct for multiple comparisons. Cohen’s d using pooled standard deviation was used to examine the effect size.

3. Results

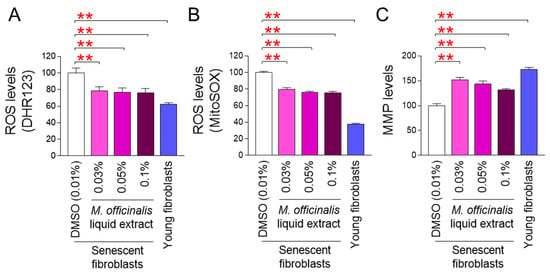

3.1. M. officinalis Liquid Extract Ameliorates Mitochondrial Function

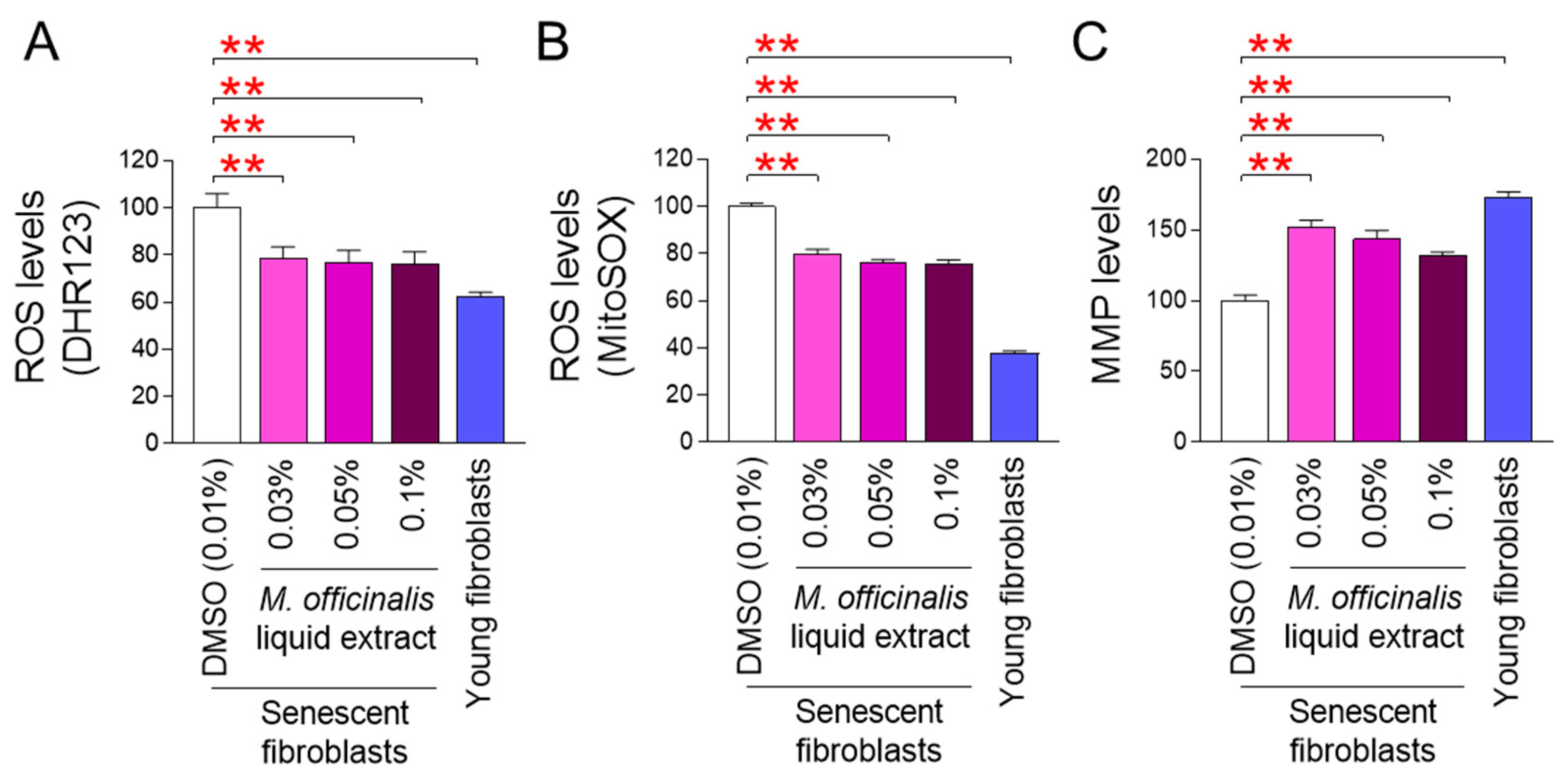

In a previous study, we found that the dry extract of M. officinalis ameliorated senescence by inhibiting mitochondria-enriched ROS production in senescent fibroblasts [12]. Based on these previous results, we hypothesized that M. officinalis liquid extract might have the potential to rejuvenate aged skin in clinical trials. To test this hypothesis, M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, and 0.1%) suitable for use in cosmetic formulations was prepared. We then examined whether these liquid extracts had antioxidant effects on senescent fibroblasts similar to those of the dry extract used in our previous study. Subsequently, the effects of M. officinalis liquid extract on mitochondria-enriched ROS levels were assessed by measuring the amounts of hydroxyl radicals and superoxide using DHR123 and MitoSOX, respectively. Young fibroblasts were used as a positive control. Mitochondria-enriched ROS levels in young fibroblasts were significantly lower than those in DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts (Figure 1A,B). Moreover, mitochondria-enriched ROS levels in senescent fibroblasts treated with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%) were significantly reduced compared to those in senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO (Figure 1A,B). These results suggest that M. officinalis liquid extract, as a precursor of cosmetic formulations, reduced mitochondria-enriched ROS production.

Figure 1.

M. officinalis liquid extract ameliorates mitochondrial function. (A,B) Mitochondria-enriched ROS levels were measured in senescent fibroblasts administered with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. Use of DHR123 (A) and MitoSOX (B) for flow cytometry. Young fibroblasts were used as positive control. ** p < 0.01, Student’s t-test. Mean ± S.D., n = 3 as biological replicates. (C) MMP levels were assessed in senescent fibroblasts administered with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. Young fibroblasts were used as positive control. ** p < 0.01, Student’s t-test. Mean ± S.D., n = 3 as biological replicates.

Since the most prominent mitochondrial damage induced by ROS is a reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), we evaluated the effect of M. officinalis liquid extract on MMP. Young fibroblasts, used as a positive control, showed significantly higher MMP levels than senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO (Figure 1C). Furthermore, the MMP levels of senescent fibroblasts treated with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%) were significantly upregulated compared to those of senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO (Figure 1C). These results suggest that M. officinalis liquid extract increases MMP by lowering mitochondria-enriched ROS production.

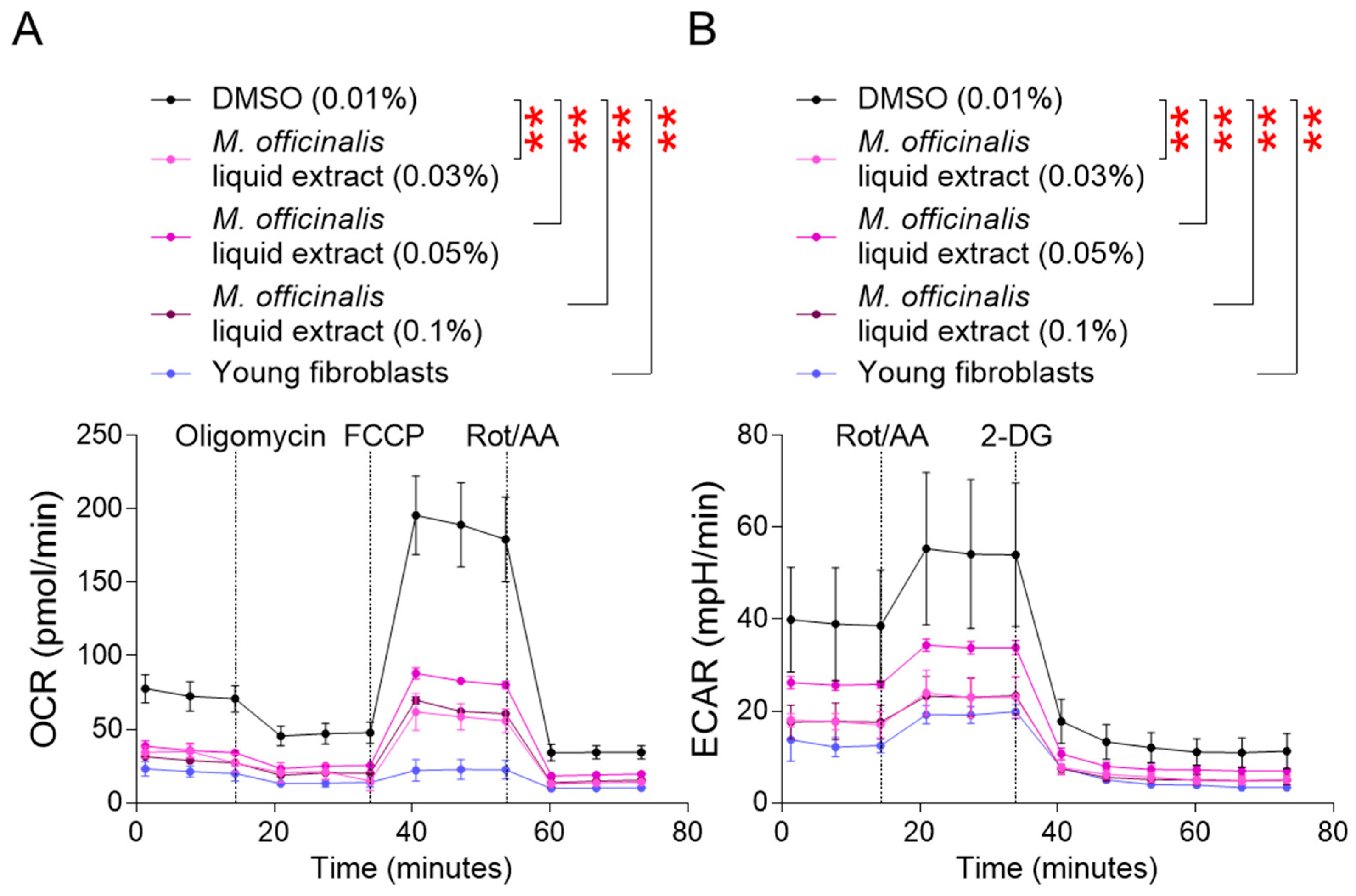

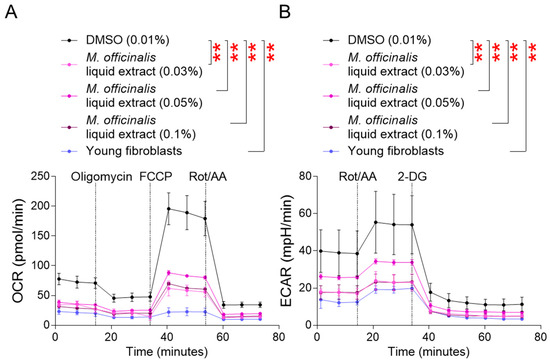

3.2. M. officinalis Liquid Extract Restores Mitochondrial Metabolic Function

MMP is generated during oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in mitochondria. After confirming the impact of M. officinalis liquid extract on upregulating MMP, the oxygen consumption rate (OCR), a marker of OXPHOS efficiency, was examined [25]. OCR was evaluated sequentially after administration of oligomycin, carbonyl cyanide–p–trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), and rotenone/antimycin A. The OCR of young fibroblasts was significantly lower than that of senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO, indicating that young fibroblasts consume less oxygen due to efficient OXPHOS (Figure 2A). Furthermore, senescent fibroblasts treated with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%) showed a significantly lower OCR than DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts, suggesting that M. officinalis liquid extract increased OXPHOS efficiency (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

M. officinalis liquid extract restores mitochondrial metabolic function. (A) Oxygen consumption rate (OCR; pmol/min) was measured in senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. Young fibroblasts were used as positive control. ** p < 0.01, two–way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Means ± S.D., n = 3 as biological replicates. (B) Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR; mpH/min) was measured in senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. Young fibroblasts were used as positive control. ** p < 0.01, two–way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Means ± S.D., n = 3 as biological replicates.

Increased OXPHOS efficiency reduces the reliance on glycolysis [25]. The finding that M. officinalis liquid extract upregulates OXPHOS efficiency prompted us to study the reliance on glycolysis by measuring the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) [25]. ECAR was measured before and after rotenone/antimycin A and 2–deoxy–D–glucose (2–DG) treatment [25]. Young fibroblasts’ ECAR was significantly lower than that of DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts, suggesting that young fibroblasts rely less on glycolysis than do senescent fibroblasts (Figure 2B). Additionally, the ECAR of senescent fibroblasts treated with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%) was significantly reduced compared to that of DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts, indicating that the M. officinalis liquid extract decreased the reliance on glycolysis (Figure 2B).

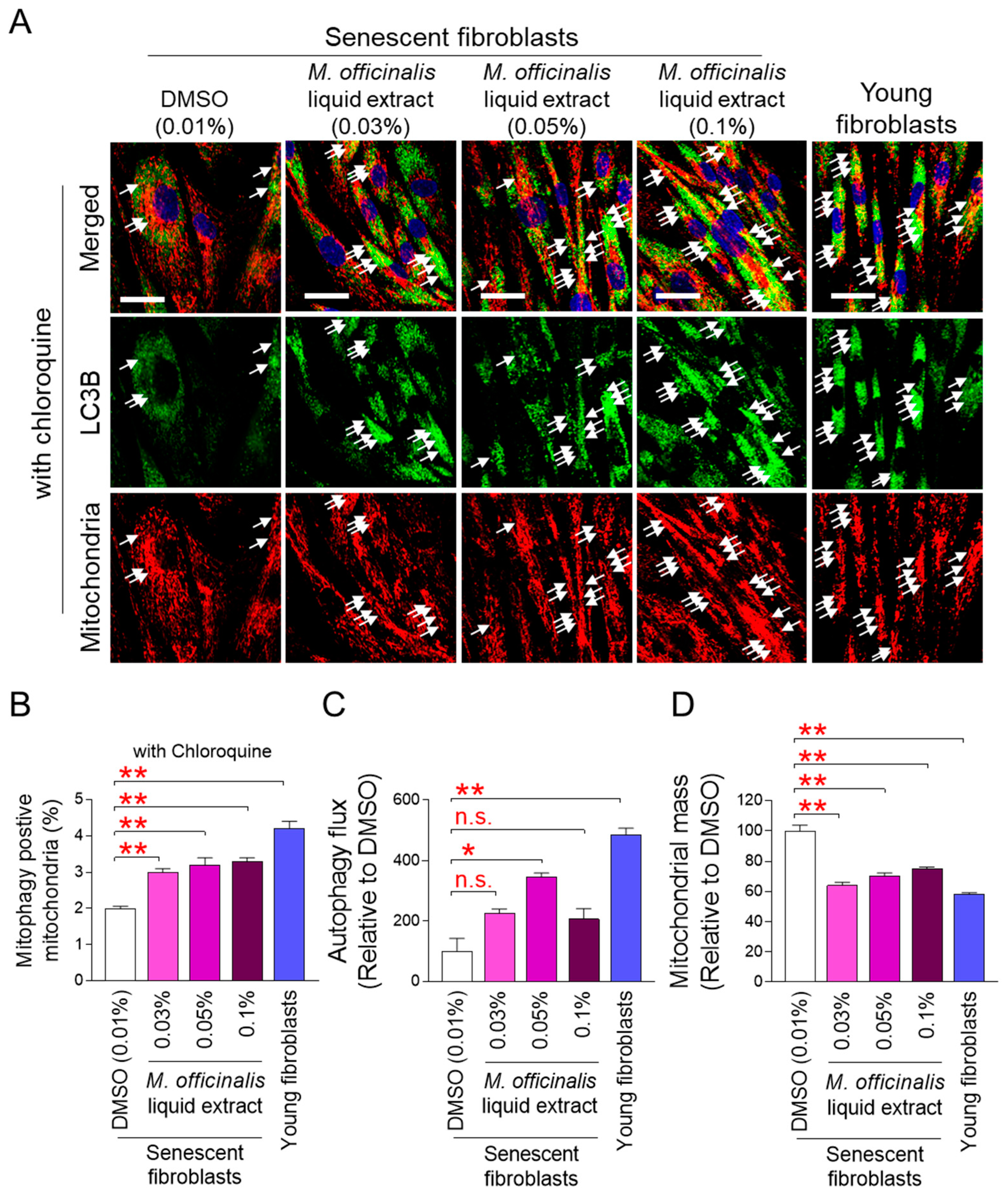

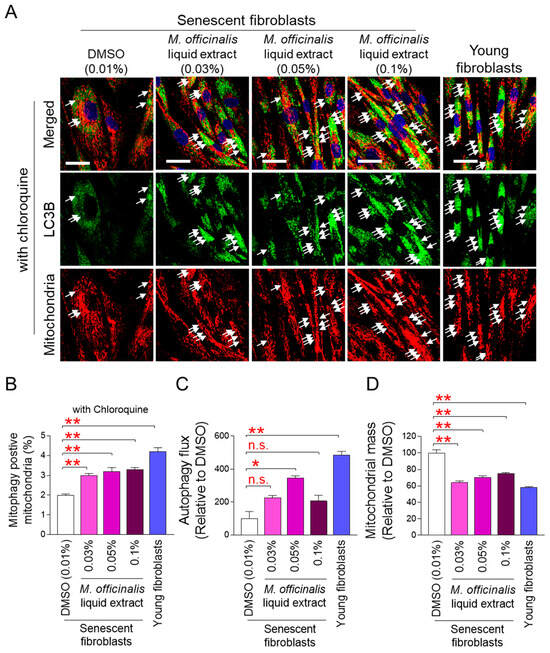

3.3. M. officinalis Liquid Extract Induces Restoration of Mitophagy and Autophagy Activity

The finding that M. officinalis liquid extract restores mitochondrial function led to further investigation into the mechanism by which M. officinalis liquid extract exerts this effect. Mitophagy removes damaged mitochondria and restores mitochondrial function [26]. Therefore, we hypothesized that M. officinalis liquid extract restores mitochondrial function by activating mitophagy. Because mitophagy specifically removes defective mitochondria using autophagosomes [26], this was assessed by examining the co-localization of the autophagosome membrane protein microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B–light chain 3B (LC3B) with mitochondria. Young fibroblasts exhibited a significant increase in the co-localization compared to DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts (Figure S1; white arrows). After senescent fibroblasts were treated with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%), the co-localization significantly increased compared to DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts (Figure S1; white arrows). To further confirm the role of M. officinalis liquid extract in mitophagy, we included a group treated with chloroquine (CQ). CQ induces autophagosome accumulation by disrupting lysosomal pH, which increases the co-localization of LC3B and mitochondria. CQ treatment increased colocalization in both young and senescent fibroblasts, providing proof of concept for the effect of CQ (Figure 3A,B; white arrows). Furthermore, senescent fibroblasts co-treated with CQ and M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%) showed the significant increase in the co-localization compared to senescent fibroblasts co-treated with CQ and DMSO (Figure 3A,B; white arrows). These results suggest that M. officinalis liquid extract promotes mitophagy activation.

Figure 3.

M. officinalis liquid extract induces restoration of mitophagy and autophagy activity. (A,B) Immunostaining for LC3B (green) and mitochondria (red). Senescent fibroblasts were treated with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. Young fibroblasts were used as positive control. 20 μM chloroquine was added to cells 24 h before immunofluorescence analysis. Scale bar 10 μm. Mitophagy is indicated by a white arrow. ** p < 0.01, Student’s t-test. Mean ± S.D., n = 3 as biological replicates. (C,D) Autophagy flux or mitochondrial mass was assessed in senescent fibroblasts administered with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. Young fibroblasts were used as positive control. n.s. (not significant), * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, Student’s t-test. Mean ± S.D., n = 3 as biological replicates.

Next, we measured autophagic flux to quantify mitophagy activation by the M. officinalis liquid extract. Autophagic flux is the rate at which autophagy removes damaged organelles [27]. Young fibroblasts exhibited significantly higher autophagic flux than DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts, indicating active removal of damaged organelles by autophagy (Figure 3C). Treatment of senescent fibroblasts with the M. officinalis liquid extract at concentrations of 0.03% and 0.1% increased autophagic flux compared to DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts (Figure 3C). Notably, treatment of senescent fibroblasts with the M. officinalis liquid extract at a concentration of 0.05% significantly increased autophagic flux compared to DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts, suggesting that M. officinalis liquid extract at 0.05% concentration was more effective in increasing autophagy flux than other concentrations. (Figure 3C).

Because autophagy flux is the rate at which organelles, including damaged mitochondria, are removed, we measured mitochondrial mass to determine whether mitophagy removes damaged mitochondria. Compared to DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts, young fibroblasts exhibited significantly less mitochondrial mass (Figure 3D). When senescent fibroblasts were administered with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%), mitochondrial mass was significantly decreased compared with DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts (Figure 3D). These results suggest that mitophagy activation by M. officinalis liquid extract plays a key role in reducing mitochondrial mass in senescent fibroblasts.

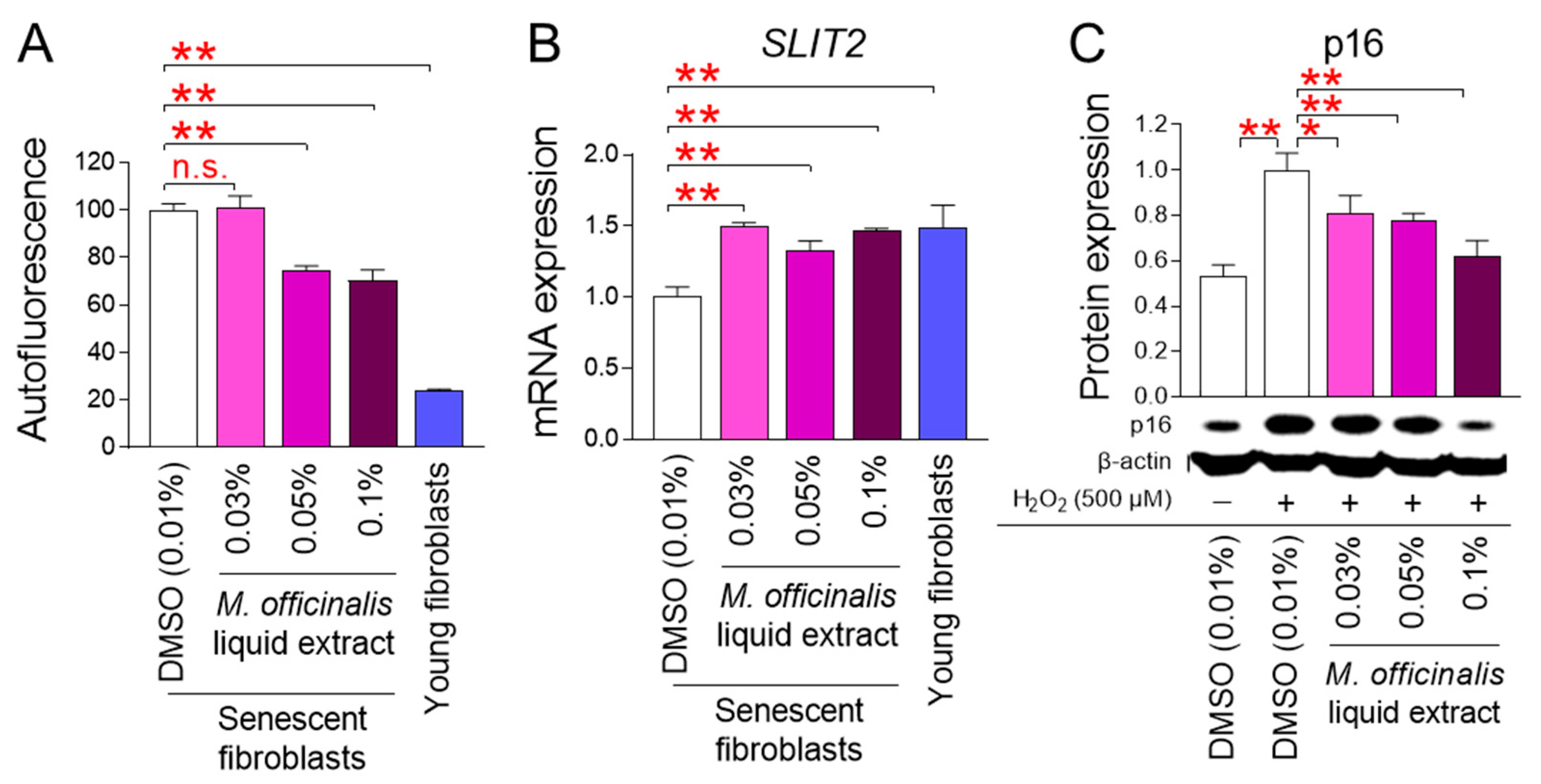

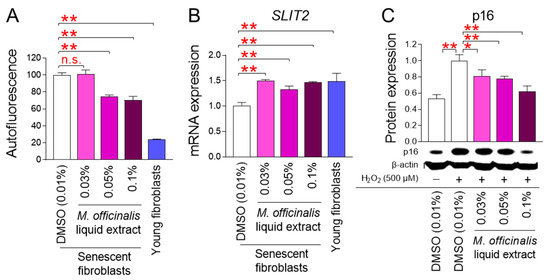

3.4. M. officinalis Liquid Extract Rejuvenates Senescence-Associated Phenotypes

Restoration of mitochondrial function is essential for rejuvenating senescence [2]. The finding that M. officinalis liquid extract restores mitochondrial function prompted us to evaluate the effects of M. officinalis liquid extract on senescence. We assessed the impact of M. officinalis liquid extract on the quantity of lipofuscin, a cross-linked protein residue produced during senescence by iron-catalyzed oxidation [28]. Lipofuscin was assessed by measuring autofluorescence [28]. Young fibroblasts exhibited significantly lower autofluorescence than DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts (Figure 4A). Treatment of senescent fibroblasts with M. officinalis liquid extract at a concentration of 0.03% did not reduce autofluorescence compared to DMSO–treated senescent fibroblasts (Figure 4A). However, when senescent fibroblasts were administered with the M. officinalis liquid extract at concentrations of 0.05% and 0.1%, autofluorescence was significantly reduced compared to senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO (Figure 4A). These results suggest that autofluorescence was not effectively reduced when senescent fibroblasts were treated with the low concentration (0.03%) of the M. officinalis liquid extract, whereas autofluorescence was effectively reduced when senescent fibroblasts were administered with high concentrations (0.05% and 0.1%).

Figure 4.

M. officinalis liquid extract rejuvenates senescence-associated phenotypes. (A,B) Autofluorescence (A) or SLIT2 expression (B) was assessed in senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. Young fibroblasts were used as positive control. n.s. (not significant), ** p < 0.01, Student’s t-test. Mean ± S.D., n = 3 as biological replicates. (C) Expression levels of p16 protein after exposure to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Then, cells were administered with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. Young fibroblasts were used as positive control. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, Student’s t-test. Mean ± S.D., n = 3 as biological replicates.

Slit–inducing ligand 2 (SLIT2) controls cell–cell connections to aid in the regeneration of skin tissue [29,30]. Since upregulation of SLIT2 expression increases tissue regeneration capacity and improves skin barrier function, we investigated the impact of M. officinalis liquid extract on SLIT2 expression. Young fibroblasts showed significantly higher SLIT2 expression than senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO, suggesting the efficient tissue regeneration capacity of young fibroblasts (Figure 4B). When senescent fibroblasts were administered with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%), SLIT2 expression increased compared to senescent fibroblasts treated with DMSO (Figure 4B). These results suggest that M. officinalis liquid extract promotes regenerative capacity and contributes to the senescence rejuvenation. However, overexpression of SLIT2 can promote skin tumorigenesis [30]. Therefore, while restoring SLIT2 levels in senescent fibroblasts may be desirable, increasing SLIT2 levels in young fibroblasts may be detrimental. Therefore, to rule out these side effects, we examined the expression of SLIT2 in young fibroblasts treated with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. When young fibroblasts were treated with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, and 0.1%), SLIT2 expression did not increase compared to young fibroblasts treated with DMSO (Figure S3). These results indicate that M. officinalis liquid extract does not promote SLIT2 expression in young fibroblasts, and thus is unlikely to lead to skin tumorigenesis.

Exposure to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a type of ROS, can induce stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS) [31]. SIPS is a form of senescence that exhibits characteristics similar to replicative senescence [32]. A model that investigates the expression of p16, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, after induction of SIPS using H2O2 has been widely used in senescence research [33]. In this study, young fibroblasts were treated with H2O2 to induce senescence. Then, we evaluated whether M. officinalis liquid extract could rejuvenate SIPS. Treatment of young fibroblasts with 500 μM H2O2 significantly increased p16 expression compared to the untreated group, suggesting that H2O2 induces SIPS (Figure 4C). When H2O2-induced fibroblasts were treated with M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05%, 0.1%), p16 expression was significantly reduced compared with H2O2-induced fibroblasts (Figure 4C). These results suggest that M. officinalis liquid extract is also effective in restoring SIPS.

The discovery that M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in rejuvenating senescence-associated phenotypes led us to provide the basic phytochemical profile of M. officinalis liquid extract. M. officinalis extract was known to be rich in bioactive phytochemicals, primarily lignans (magnolol & honokiol) along with phenolic compounds, alkaloids, and essential oils [11]. Two primary ingredients, honokiol and magnolol, have been known to have antioxidant effects [34]. Honokiol, a biphenolic lignan, has powerful antioxidant effects that may be beneficial in neuroprotection, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumorigenic applications [35]. Magnolol is a biphenyl derivative that acts as an oxygen radical scavenger through redox reactions. Therefore, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted to evaluate how much honokiol and magnolol were present in the M. officinalis liquid extract. The HPLC peak of the M. officinalis liquid extract matched the honokiol standard, and the amount of honokiol present in the M. officinalis liquid extract was 12.20% (Figure S2). This result was very similar to the standard value of 14.2% from previous tests [36]. The HPLC peak of the M. officinalis liquid extract matched the magnolol standard, and its amount was 6.29% of the total extract (Figure S2). This result was similar to values from previous tests (0.78–7.65%) [37].

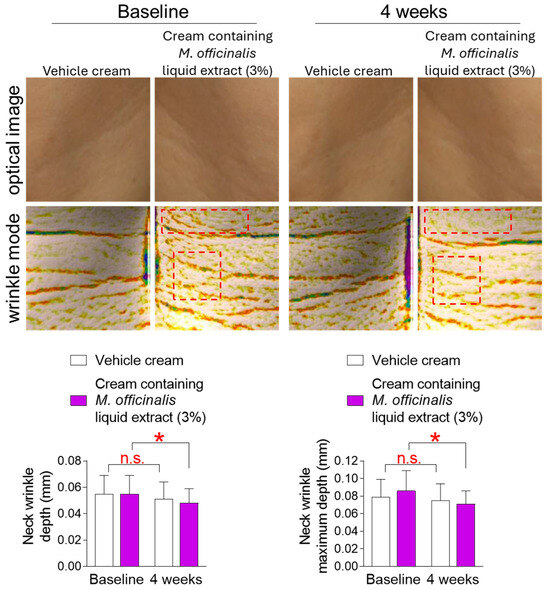

3.5. The Cream Containing M. officinalis Liquid Extract Is Effective in Reducing Neck Wrinkles

The discovery that M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in senescence rejuvenation in vitro led to a clinical trial to determine whether it also has anti-aging effects on human skin. The skin of the face and neck is more easily exposed to the external environment than other skin areas [38]. In particular, the skin of the neck is thinner than the facial skin, making it more prone to wrinkles [38]. Therefore, we investigated changes in neck wrinkles after topical application of a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) to the neck of participants for 4 weeks. The mean and maximum depth of neck wrinkles in participants who received the vehicle cream did not significantly decrease compared to baseline (Figure 5). Specifically, in participants who received the vehicle cream, the effect sizes for neck wrinkle depth and neck wrinkle maximum depth were 0.32 and 0.22, respectively, indicating a small effect size (Table S1). However, the mean and maximum depths of neck wrinkles in participants who received the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) were significantly reduced by 12.73% and 17.44%, respectively, compared to baseline (Figure 5). Specifically, in participants who received the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%), the effect sizes for neck wrinkle depth and neck wrinkle maximum depth were 0.65 and 0.78, respectively, indicating a modest magnitude of change (Table S1). These results indicate that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in reducing neck wrinkles.

Figure 5.

The cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in reducing neck wrinkles. Images of the left and right neck areas were taken after the topical application of a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) to the neck of participants for 4 weeks. The mean and maximum depth of neck wrinkles were measured on the same area at the start of treatment (baseline) and 4 weeks later (4 weeks). Red dotted box: Representative areas showing improvement in neck wrinkles before and after treatment. n.s. (not significant), * p < 0.05, RM-ANOVA. Mean ± S.D., n = 21. Details for graphs (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, sample size, and effect size) were shown in Table S1.

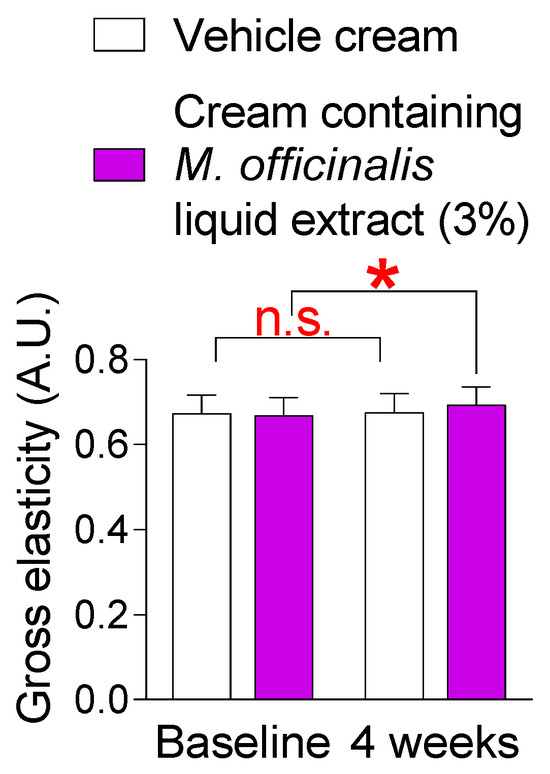

3.6. The Cream Containing M. officinalis Liquid Extract Is Effective in Enhancing Skin Elasticity

Loss of skin elasticity is a precursor to wrinkles [39]. Our discovery that a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract was effective in reducing neck wrinkles led us to investigate its effect on skin elasticity, a precursor to wrinkles. Here, changes in skin elasticity were observed after topical application of a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) to the participants’ skin for 4 weeks. The skin elasticity of participants who received the vehicle cream did not significantly increase compared to the baseline (Figure 6). Specifically, in participants who received the vehicle cream, the effect size for the skin elasticity was −0.08, indicating a negligible effect size (Table S2). However, the skin elasticity of participants who received the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) significantly increased by 3.76% compared to the baseline (Figure 6). Specifically, in participants who received the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%), the effect size for the skin elasticity was −0.59, indicating a moderate effect size (Table S2). These results suggest that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in improving skin elasticity.

Figure 6.

The cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in enhancing skin elasticity. The skin elasticity was measured after the topical application of a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) to the skin of participants for 4 weeks. The elasticity of left and right cheeks was measured on the same area at the start of treatment (baseline) and 4 weeks later (4 weeks). n.s. (not significant), * p < 0.05, RM-ANOVA. Mean ± S.D., n = 21. Details for graphs (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, sample size, and effect size) were shown in Table S2.

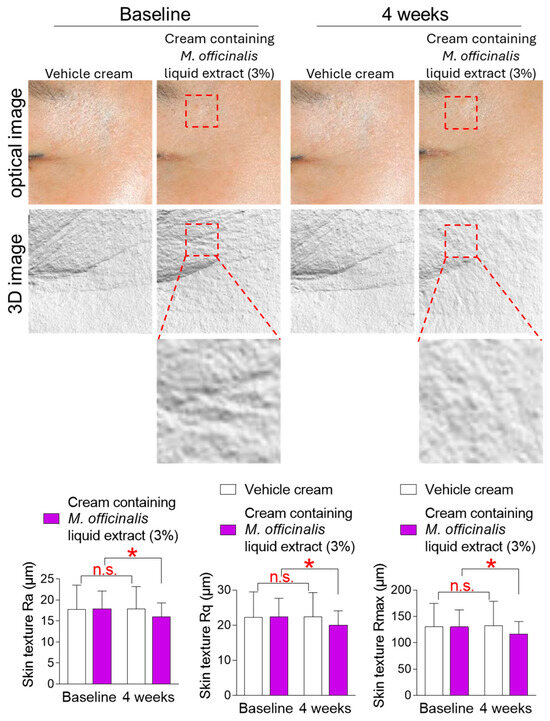

3.7. The Cream Containing M. officinalis Liquid Extract Is Effective in Improving Skin Texture

An uneven or rough skin surface is caused by age–related changes, such as skin wrinkling, that alter the skin surface [40]. The mean roughness (Ra), root mean square roughness (Rq), and maximum depth of roughness (Rmax) are parameters used to quantify surface texture. Here, changes in skin texture were observed after the topical application of a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) around participants’ cheeks for 4 weeks. Ra, Rq, and Rmax in participants who received the vehicle cream did not decrease significantly compared to baseline (Figure 7). Specifically, in participants who received the vehicle cream, effect sizes for Ra, Rq, and Rmax were 0.035, 0.055, and 0.090, respectively, indicating negligible effect sizes (Table S3). However, in participants who received the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%), Ra, Rq, and Rmax were significantly reduced by 12.73%, 10.16%, and 10.81%, respectively, compared to baseline (Figure 7). Specifically, in participants who received the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%), effect sizes for Ra, Rq, and Rmax were 0.48, 0.48, and 0.50, respectively, indicating moderate effect sizes (Table S3). These results suggest that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in making the skin surface smoother and more uniform.

Figure 7.

The cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in improving skin texture. Images of the left and right cheek areas were taken after the topical application of a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) around the cheeks of participants for 4 weeks. The mean roughness (Ra), root mean square roughness (Rq), and maximum depth of roughness (Rmax) were measured on the same area at the start of treatment (baseline) and 4 weeks later (4 weeks). Red dotted box: Representative areas showing improvement in skin texture before and after treatment. n.s. (not significant), * p < 0.05, RM-ANOVA. Mean ± S.D., n = 21. Details for graphs (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, sample size, and effect size) were shown in Table S3.

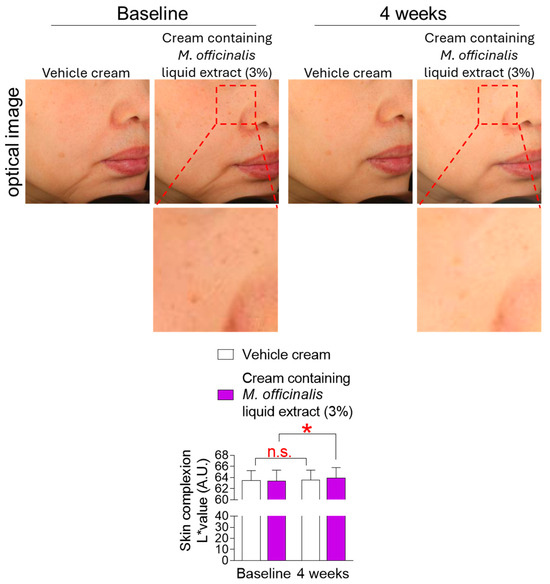

3.8. The Cream Containing M. officinalis Liquid Extract Is Effective in Improving Skin Complexion

Skin complexion refers to the overall condition of the skin, including both the skin’s natural color and the color beneath the skin’s surface [41]. Hyperpigmentation is a darkening of the skin color caused by increased melanin production in melanocytes during the aging process [41]. Skin flushing is another characteristic of skin aging, resulting from the loss of collagen and vascular elasticity in the dermis [6]. The L* value is a parameter used to quantify the degree of skin complexion [42]. Specifically, the L* value represents the skin’s brightness, with higher values indicating lighter skin and lower values indicating darker skin. Here, the degree of skin complexion was observed after the topical application of a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) to participants’ cheeks for 4 weeks. The L* value of participants receiving the vehicle cream did not significantly increase compared to baseline (Figure 8). Specifically, in participants who received the vehicle cream, the effect size for the L* value was −0.07, indicating a negligible effect size (Table S4). However, the L* value of participants receiving the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) significantly increased by 0.76% compared to baseline (Figure 8). Specifically, in participants who received the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%), the effect size for the L* value was −0.25, indicating a moderate amount of change (Table S4). These data indicate that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in whitening skin.

Figure 8.

The cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract is effective in improving skin complexion. Images of the left and right cheek areas were taken after the topical application of a vehicle cream or a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%) around the cheeks of participants for 4 weeks. The L* value was measured in the same area at the start of treatment (baseline) and 4 weeks later (4 weeks). Red dotted box: Representative areas showing improvement in skin complexion before and after treatment. n.s. (not significant), * p < 0.05, RM-ANOVA. Mean ± S.D., n = 21. Details for graphs (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, sample size, and effect size) were shown in Table S4.

4. Discussion

One of the main causes of skin aging is oxidative stress caused by ROS [43]. ROS weakens the collagen that makes up the dermal layer, compromising the structural integrity of subcutaneous tissue [7]. Furthermore, ROS weakens the proteins and phospholipids that make up cell membranes, compromising cell structure. The instability or unpaired electrons of ROS can further exacerbate their detrimental effects on skin aging [44]. This property allows ROS to steal electrons from nearby molecules, triggering an oxidative chain reaction in nearby tissues [44]. Therefore, ROS causes significant damage to the skin, thereby exacerbating skin aging [8]. In this study, we found that M. officinalis liquid extract restored mitochondrial function, thereby reducing mitochondria-enriched ROS levels. Specifically, upregulation of OXPHOS efficiency and downregulation of glycolysis dependence suggest that M. officinalis liquid extract restored mitochondrial function. In subsequent clinical trials, M. officinalis liquid extract improved skin elasticity loss caused by ROS-induced collagen–elastin chain scission and collagen oxidation. Here, we propose that reducing mitochondria-enriched ROS production using M. officinalis liquid extract may be the first step in reducing skin damage, thereby rejuvenating skin aging.

Mitochondria are highly dynamic cellular organelles that constantly undergo cell division and fusion. However, dysfunctional mitochondria fail to reintegrate into the mitochondrial network and are eliminated through autophagy [23]. Maintaining cellular homeostasis relies on the selective removal of damaged mitochondria through mitophagy, as damaged mitochondria have a reduced ability to generate ATP and increase ROS production [24]. In this study, we found that the M. officinalis liquid extract stimulates mitophagy. M. officinalis liquid extract may contribute to reducing mitochondria-enriched ROS levels by removing dysfunctional mitochondria through this mitophagy activation effect. However, pharmacological or genetic inhibition experiments have not been conducted to confirm the necessity of the mitophagy activation by M. officinalis liquid extract. If such experiments were conducted, they would provide evidence that mitophagy induced by M. officinalis liquid extract is essential for reducing mitochondria-enriched ROS. Direct evidence of the effect of M. officinalis liquid extract on mitochondria-enriched ROS would provide a theoretical basis for its application in the treatment of skin aging.

Skin wrinkles are major visual indicators of skin aging [45]. Wrinkles are caused by damage and degradation of collagen and elastin, which are essential for maintaining skin elasticity [45,46]. In senescent fibroblasts, impaired mitophagy leads to the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, which in turn triggers excessive mitochondrial ROS production, promoting oxidative damage and collagen degradation [47]. Conversely, restoring mitophagy activates a cytoprotective mechanism that reduces wrinkle severity by removing damaged mitochondria and maintaining the structural integrity of the extracellular matrix [48,49]. Previous studies have shown that M. officinalis dry extract promotes skin regeneration, demonstrating upregulation of genes associated with skin regeneration and downregulation of genes associated with collagen degradation [12]. However, previous studies were limited to in vitro studies and did not directly investigate the effect of M. officinalis in vivo. This study investigated the effects of a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract on skin wrinkles. Topical application of a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract was effective in reducing the average and maximum wrinkle depths on the neck. These beneficial effects are further supported by the result showing that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract increases skin elasticity, which plays a key role in preventing wrinkles [46]. This study is the first to demonstrate that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract can improve skin wrinkles by increasing skin elasticity. Although this study suggests that M. officinalis liquid extract may reverse signs of skin wrinkles, further studies are needed to confirm the direct effects of M. officinalis liquid extract on mitophagy activation, mitochondria-enriched ROS reduction, and subsequent improvement of wrinkles.

Skin quality encompasses the overall condition of the skin, including its texture and complexion [50]. Skin texture refers to the feel of the skin surface (e.g., smooth or rough), whereas skin complexion refers to the overall color and tone of the skin [50]. Previous studies have shown that M. officinalis dry extract increases skin turnover, which plays a crucial role in maintaining skin texture [12]. Furthermore, M. officinalis dry extract has been shown to reduce skin hyperpigmentation by decreasing the expression of genes that induce skin hyperpigmentation and increasing the expression of genes that reduce skin hyperpigmentation [12]. Based on these findings, this study investigated the effects of the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract on skin texture and complexion. Topical application of the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract significantly reduced all indices used to quantify skin texture. Furthermore, the cream showed both improved skin color and tone. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract improves skin texture and complexion, suggesting its potential as a high-quality cosmetic ingredient.

The clinical results of this study suggest that M. officinalis liquid extract can contribute to the recovery of skin aging. The reduction in neck wrinkle depth suggests that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract significantly improves morphological deterioration of skin caused by aging. Specifically, the results based on objective indicators such as skin texture and complexion suggest that the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract has a positive effect on the overall skin appearance. This study will serve as a touchstone for the development of cosmetics effective in improving skin aging. If this study is validated in a broader clinical setting in the future, the potential of M. officinalis liquid extract as a cosmetic ingredient will be further expanded.

The reduction in mitochondrial ROS demonstrated in fibroblast-based experiments is proposed to underlie the clinical improvements observed in this study. However, biomarkers such as mitochondrial ROS have not been evaluated in human skin. Therefore, future clinical studies should directly assess biomarkers linked to the mechanisms identified in fibroblast-based experiments within human skin to determine whether these mechanistic effects are reproducible in a clinical context. Such an approach would help establish the mechanistic findings from fibroblast-based experiments as direct evidence supporting clinical improvement.

In cell-based experiments, M. officinalis liquid extract was used at concentrations of 0.03%, 0.05%, and 0.1%, while the clinical study used a 3% concentration. This difference is due to the fact that in cell-based experiments, the active ingredient is directly exposed to cells, allowing it to be effective even at relatively low concentrations. Conversely, topical application to human skin has limited penetration and bioavailability, necessitating higher concentrations [51]. However, further research is needed to determine the optimal concentration of M. officinalis liquid extract in a cream that can penetrate the skin barrier and exert physiological effects. Establishing an optimal concentration that satisfies efficacy is expected to strengthen the scientific basis for the use of M. officinalis liquid extract in anti-aging skincare.

The 0.76% increase in L* values observed in participants using the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract was statistically significant, suggesting an improvement in skin tone. However, the magnitude of this change is small and may not be noticeable outside of a controlled laboratory setting [52]. Furthermore, the observed increase may not reach the threshold considered clinically significant in cosmetic dermatology [53]. Therefore, the practical significance of this result should be interpreted cautiously. Further studies are needed to elucidate the effect of cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract on skin complexion by simultaneously measuring the a* value, which indicates the degree of skin redness, and the b* value, which indicates the degree of skin yellowness, in addition to the L* value.

The in vitro experiments in this study were conducted using three biological replicates, a method commonly used in studies investigating biological effects [54,55]. However, this limited sample size reduces statistical power and increases the risk of false-positive results, especially when measuring multiple comparisons [56]. Therefore, future studies should use larger sample sizes and apply appropriate corrections for multiple comparisons to improve the reproducibility of the results.

There are several considerations when interpreting the results of this clinical study. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 21) may limit the statistical power of the study results. Therefore, larger studies are needed to confirm the reproducibility of the observed skin aging improvement effects. Second, the study subjects consisted of a single ethnic group. Because skin structure and response to topical treatments may vary by ethnicity, it is uncertain whether these results can be applied to other populations. Future studies that include a more diverse ethnic group are needed to assess the broad applicability of the results. Third, the study period was relatively short. While significant improvements in skin aging indicators were observed during the 4-week intervention period, long-term studies are needed to assess the sustained efficacy and safety of a cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract (3%).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found that M. officinalis liquid extract restored mitochondrial function and reduced mitochondria-enriched ROS production. Furthermore, activating mitophagy to remove defective mitochondria was one of the strategies by which M. officinalis liquid extract reduced mitochondria-enriched ROS production. In a clinical study, the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract improved morphological indicators of skin aging by improving neck wrinkles. Furthermore, the cream containing M. officinalis liquid extract improved skin texture and complexion, thereby enhancing overall skin appearance. M. officinalis liquid extract has antioxidant properties that help alleviate skin aging and show promise as a next-generation anti-aging cosmetic ingredient.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cosmetics13010022/s1, Figure S1: Immunostaining for LC3B (green) and mitochondria (red); Figure S2: Identification of honokiol and magnolol from M. officinalis liquid extracts; Figure S3: SLIT2 expression was assessed in young fibroblasts treated with DMSO (0.01%) or M. officinalis liquid extract (0.03%, 0.05% and 0.1%) every 4 days for 12 days. n.s. (not significant), Student’s t-test. Mean ± S.D., n = 3; Table S1: Details for graphs shown in Figure 5 (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, sample size, and effect size); Table S2: Details for graphs shown in Figure 6 (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, sample size, and effect size); Table S3: Details for graphs shown in Figure 7 (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, sample size, and effect size); Table S4: Details for graphs shown in Figure 8 (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, sample size, and effect size).

Author Contributions

Y.H.L., E.Y.J., Y.H.K., S.O., Y.B.,. S.S.S. and J.T.P. Investigation: Y.H.L., E.Y.J., Y.H.K., S.O., J.H.P., J.H.Y., Y.J.L., D.K., B.S., M.K., S.Y.K. and H.W.K. Data curation: J.H.P., J.H.Y., Y.J.L., D.K., B.S., M.K., S.Y.K. and H.W.K. Writing—original draft: Y.H.L., E.Y.J., Y.H.K., S.O., Y.B., S.S.S. and J.T.P. Writing—review & editing: J.H.P., J.H.Y., Y.J.L., D.K., B.S., M.K., S.Y.K. and H.W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (RS–2023–KH140816, RS–2025–02303821).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials. Paraphrasing tool (https://quillbot.com/) was used for language polishing. https://quillbot.com/paraphrasing-tool (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Eun Young Jeong, So Yeon Kim and Song Seok Shin are employees of Hyundai Bioland Co., Ltd. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Miwa, S.; Kashyap, S.; Chini, E.; von Zglinicki, T. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cell senescence and aging. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e158447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, H.; Song, E.S.; Kuk, M.U.; Joo, J.; Oh, S.; Kwon, H.W.; Park, J.T.; Park, S.C. Targeting Mitochondrial Metabolism as a Strategy to Treat Senescence. Cells 2021, 10, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, C.; Marchi, S.; Simoes, I.C.M.; Ren, Z.; Morciano, G.; Perrone, M.; Patalas-Krawczyk, P.; Borchard, S.; Jędrak, P.; Pierzynowska, K.; et al. Mitochondria and Reactive Oxygen Species in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 340, 209–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.M. Skin barrier function. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008, 8, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boismal, F.; Serror, K.; Dobos, G.; Zuelgaray, E.; Bensussan, A.; Michel, L. Skin aging: Pathophysiology and innovative therapies. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.; Khan, A.; Gupta, M. Skin Ageing: Pathophysiology and Current Market Treatment Approaches. Curr. Aging Sci. 2020, 13, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, N.H.A.; Abdulla, S.K.; Ali, N.M.; Ahmed, V.A.; Hasan, A.H.; Qadir, E.E. Role of antioxidants in skin aging and the molecular mechanism of ROS: A comprehensive review. Asp. Mol. Med. 2025, 5, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaccio, F.; D’Arino, A.; Caputo, S.; Bellei, B. Focus on the Contribution of Oxidative Stress in Skin Aging. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullar, J.M.; Carr, A.C.; Vissers, M.C.M. The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.C. Mechanistic Basis and Clinical Evidence for the Applications of Nicotinamide (Niacinamide) to Control Skin Aging and Pigmentation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poivre, M.; Duez, P. Biological activity and toxicity of the Chinese herb Magnolia officinalis Rehder & E. Wilson (Houpo) and its constituents. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B 2017, 18, 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H.; Jeong, E.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, J.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Nam, Y.K.; Cha, S.Y.; Park, J.S.; et al. Identification of senescence rejuvenation mechanism of Magnolia officinalis extract including honokiol as a core ingredient. Aging 2025, 17, 497–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwil, M.; Dzida, K.; Terlecka, P.; Gruľová, D.; Matraszek-Gawron, R.; Terlecki, K.; Kasprzyk, A.; Kostryco, M. Antibacterial, Photoprotective, Anti-Inflammatory, and Selected Anticancer Properties of Honokiol Extracted from Plants of the Genus Magnolia and Used in the Treatment of Dermatological Problems—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, X.; Shi, W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, M.; Huang, H.; Wu, L. Insights on the Multifunctional Activities of Magnolol. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1847130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Chen, X.; Du, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, T.; Luo, S. Mitophagy in Cell Death Regulation: Insights into Mechanisms and Disease Implications. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-K. Natural products in cosmetics. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2022, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Jiang, Z.; Lin, X.; Wei, X. Application of plant extracts cosmetics in the field of anti-aging. J. Dermatol. Sci. Cosmet. Technol. 2024, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Q.; Yang, S.; Wang, C. Advancing herbal medicine: Enhancing product quality and safety through robust quality control practices. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1265178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, L.M.; Chappell, J.B. Dihydrorhodamine 123: A fluorescent probe for superoxide generation? Eur. J. Biochem. 1993, 217, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffman, M.E.; Kauffman, M.K.; Traore, K.; Zhu, H.; Trush, M.A.; Jia, Z.; Li, Y.R. MitoSOX-Based Flow Cytometry for Detecting Mitochondrial ROS. React. Oxyg. Species 2016, 2, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.E.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, T.J.; Kang, H.Y. Senescent fibroblasts drive ageing pigmentation: A potential therapeutic target for senile lentigo. Theranostics 2018, 8, 4620–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.J.; Song, E.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, K.S.; So, B.; Park, J.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Kim, D.; Kim, M.; Kwon, H.W.; et al. Dehydroacteoside rejuvenates senescence via TVP23C-CDRT4 regulation. Exp. Gerontol. 2025, 207, 112800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, X.; Huang, R.; Yan, K.; Wang, M.; Liu, W.; Zeng, X.; Ren, X.; Gong, H. Characterization of morphological and chemical changes using atomic force microscopy and metabolism assays: The relationship between surface wax and skin greasiness in apple fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1489005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piérard, G.E. EEMCO guidance for the assessment of skin colour. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 1998, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plitzko, B.; Loesgen, S. Measurement of Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) and Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) in Culture Cells for Assessment of the Energy Metabolism. Bio-Protocol 2018, 8, e2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Faitg, J.; Auwerx, J.; Ferrucci, L.; D’Amico, D. Mitophagy in human health, ageing and disease. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 2047–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J. Autophagy and mitophagy in cellular damage control. Redox Biol. 2013, 1, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davan-Wetton, C.S.A.; Montero-Melendez, T. An optimised protocol for the detection of lipofuscin, a versatile and quantifiable marker of cellular senescence. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lee, Y.K.; Park, S.S.; Park, S.H.; Eom, S.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, W.J.; Jang, J.; Seo, D.; Kang, H.Y.; et al. Mid-old cells are a potential target for anti-aging interventions in the elderly. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Lan, H.; Ye, J.; Li, W.; Wei, P.; Yang, Y.; Guo, S.; Lan, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Slit2 promotes tumor growth and invasion in chemically induced skin carcinogenesis. Lab. Investig. 2014, 94, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieńkowska, N.; Bartosz, G.; Pichla, M.; Grzesik-Pietrasiewicz, M.; Gruchala, M.; Sadowska-Bartosz, I. Effect of antioxidants on the H2O2-induced premature senescence of human fibroblasts. Aging 2020, 12, 1910–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, O.; Medrano, E.E.; von Zglinicki, T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS) of human diploid fibroblasts and melanocytes. Exp. Gerontol. 2000, 35, 927–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasymchuk, M.; Robinson, G.I.; Kovalchuk, O.; Kovalchuk, I. Modeling of the Senescence-Associated Phenotype in Human Skin Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.L.; Man, K.M.; Huang, P.H.; Chen, W.C.; Chen, D.C.; Cheng, Y.W.; Liu, P.L.; Chou, M.C.; Chen, Y.H. Honokiol and magnolol as multifunctional antioxidative molecules for dermatologic disorders. Molecules 2010, 15, 6452–6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Nandni; Bedi, N. Honokiol as a next-generation phytotherapeutic: Anticancer, neuroprotective, and nanomedicine perspectives. Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 2025, 17, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B. The Cardioprotective Effect of Magnolia officinalis and Its Major Bioactive Chemical Constituents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rempel, V.; Fuchs, A.; Hinz, S.; Karcz, T.; Lehr, M.; Koetter, U.; Müller, C.E. Magnolia Extract, Magnolol, and Metabolites: Activation of Cannabinoid CB2 Receptors and Blockade of the Related GPR55. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Cho, G.; Won, N.G.; Cho, J. Age-related changes in skin bio-mechanical properties: The neck skin compared with the cheek and forearm skin in Korean females. Ski. Res. Technol. 2013, 19, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, T.; Haketa, K.; Hotta, M.; Kitahara, T. Loss of skin elasticity precedes to rapid increase of wrinkle levels. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2007, 47, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Varela-Gómez, F.; Sandoval-García, A.; Valeria Cabrera-Rios, K. Signs of skin aging: A review. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2024, 12, 2674–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Park, T.J.; Kang, H.Y. Skin-Aging Pigmentation: Who Is the Real Enemy? Cells 2022, 11, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, B.C.K.; Dyer, E.B.; Feig, J.L.; Chien, A.L.; Del Bino, S. Research Techniques Made Simple: Cutaneous Colorimetry: A Reliable Technique for Objective Skin Color Measurement. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 3–12.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljšak, B.; Dahmane, R. Free radicals and extrinsic skin aging. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 135206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, K.; Tsuruta, D. What Are Reactive Oxygen Species, Free Radicals, and Oxidative Stress in Skin Diseases? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, R.S.; Bin Dayel, S.; Abahussein, O.; El-Sherbiny, A.A. Influences on Skin and Intrinsic Aging: Biological, Environmental, and Therapeutic Insights. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e16688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, L.; Bernstein, E.F.; Weiss, A.S.; Bates, D.; Humphrey, S.; Silberberg, M.; Daniels, R. Clinical Relevance of Elastin in the Structure and Function of Skin. Aesthetic Surg. J. Open Forum 2021, 3, ojab019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, T.; Li, R.; Gao, T. Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Skin Homeostasis: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Le, J.; Xiao, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, W.; Otsuki, K.; Li, W.; Xu, J.; Feng, F.; Zhang, J. Hyperoside Promotes Mitochondrial Autophagy Through the miR-361-5p/PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway, Thereby Improving UVB-Induced Photoaging. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Charareh, P.; Lei, X.; Zhong, J.L. Autophagy: Multiple Mechanisms to Protect Skin from Ultraviolet Radiation-Driven Photoaging. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8135985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, S.; Manson Brown, S.; Cross, S.J.; Mehta, R. Defining Skin Quality: Clinical Relevance, Terminology, and Assessment. Dermatol. Surg. 2021, 47, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, S.; Baek, M.; Bin, B.H. Skin Structure, Physiology, and Pathology in Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouvardos, P.; Spyropoulou, N.; Polyzois, G. Perceptibility and acceptability thresholds of simulated facial skin color differences. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2018, 62, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, H.; Lin, W.; Dong, Y.; Li, L.; Yi, F.; Meng, Q.; Li, Y.; He, Y. Statistical analysis of age-related skin parameters. Technol. Health Care 2021, 29, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udén, P.; Robinson, P.H.; Mateos, G.G.; Blank, R. Use of replicates in statistical analyses in papers submitted for publication in Animal Feed Science and Technology. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 171, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharkin, S.O.; Kim, K.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Page, G.P.; Allison, D.B. Optimal allocation of replicates for measurement evaluation studies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2006, 4, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, C.C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; Serdar, M.A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: Simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Med. 2021, 31, 010502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.