Abstract

Wildfires increasingly threaten the operation and stability of regional socio-economic systems, where infrastructure, population, and environmental conditions are tightly interconnected. To enhance operational efficiency and strengthen community resilience, this study develops an integrated optimization framework for wildfire evacuation system design based on mixed-integer programming. The model simultaneously determines the locations of primary and secondary shelters and establishes both main and backup evacuation linkages, forming a dual-stage structure that ensures continuous accessibility even under disrupted conditions such as road blockages or fire spread. Wildfire risk indices derived from topographic and environmental data are incorporated to support risk-aware and balanced shelter allocation. A case study of Uiryeong County, South Korea, demonstrates that the proposed framework effectively improves evacuation efficiency and system reliability, producing spatially coherent and adaptive evacuation plans under diverse disruption scenarios. The findings highlight how operation optimization can enhance socio-economic system resilience and sustainability when facing large-scale environmental disruptions.

1. Introduction

Wildfires have been increasing in both frequency and intensity across the globe, causing severe social, economic, and environmental damage [1]. In countries such as the United States, Australia, and Canada, large-scale wildfires have repeatedly resulted in loss of life, property destruction, and long term ecological disruption, and they have also accelerated climate change through massive carbon emissions [2,3,4]. These patterns are largely attributed to climate induced warming, prolonged droughts, and the expansion of urban development into forested areas, which have collectively intensified fire risk in wildland–urban interface (WUI) regions [5,6,7].

South Korea is particularly vulnerable to wildfire damage due to its high forest coverage and complex topography. Approximately 63% of the country’s land area is covered by forests, and nearly half lies within WUI zones [8,9,10]. This geographic structure increases the likelihood that a single wildfire can affect an extensive area, emphasizing the national need for an efficient and systematic evacuation and disaster response strategy.

Wildfire management requires both proactive measures to detect and monitor fires and reactive strategies to protect residents once a fire occurs. Technological advances have greatly improved the proactive aspects of wildfire response, including deep learning-based smoke detection models, drone surveillance systems, and risk mapping methods that integrate topographic and meteorological data [11,12,13]. Ongoing progress in related technologies can further enhance effective disaster management by providing real time data, decision support tools, and optimized coordination during evacuation operations [14]. Nevertheless, ensuring that residents can evacuate efficiently and safely remains a fundamental challenge. Because large-scale wildfires can spread rapidly and threaten multiple communities simultaneously, planning evacuation routes and allocating shelters must be approached as a complex decision making problem that accounts for spatial, temporal, and environmental factors [15].

A recent national report published in South Korea, titled “National response strategies for large-scale wildfires: Lessons from the 2025 Yeongnam wildfire crisis” [16], identified major limitations in the existing wildfire evacuation system and proposed directions for improvement. The report emphasized that current evacuation plans are often confined to small community units, making it difficult to coordinate large-scale evacuations during extreme wildfire events. At the same time, large-scale wildfires can easily extend beyond administrative and geographic boundaries. For example, a massive wildfire that occurred in a province in eastern South Korea in 2025 [17] burned an estimated 99,000 hectares, caused 28 fatalities, and forced approximately 36,000 residents to evacuate, the largest wildfire disaster in the nation’s history. This event clearly demonstrated that localized evacuation plans are insufficient to manage such widespread disasters. Therefore, it is crucial to establish comprehensive, region-wide evacuation strategies capable of addressing the complex and interconnected nature of large-scale wildfire impacts.

In response, this study addresses large-scale wildfire evacuation planning through an optimization-based approach that assumes the evacuation of nearly all residents within a county-scale rural region of Korea. The analysis is applied to Uiryeong County, a rural administrative district with a population of approximately 25,000 residents, representing a typical county-level rural area in Korea. This research verifies the feasibility of large-scale, data-driven evacuation optimization and demonstrates its potential for practical application in regional disaster management.

To this end, a mixed-integer programming (MIP) model is developed to optimize two-stage evacuation under wildfire conditions. In contrast to prior works that focus on single stage shelter selection or route optimization [18,19,20], the proposed model offers the following distinctive features:

- Simultaneous determination of primary and secondary shelters: The model optimizes both short-term (primary) and long-term (secondary) shelter locations within a single integrated framework. Primary shelters serve as immediate, short distance refuges that residents can reach quickly during the initial spread of the wildfire. Secondary shelters are larger and safer facilities designed for long-term accommodation and resource support once the immediate danger subsides. By jointly determining both types of shelters, the model enables a structured and continuous evacuation process that enhances safety and continuity during the transition from primary to secondary shelters.

- Resilient evacuation with main and backup linkages: The model simultaneously optimizes main linkages, representing standard evacuation flows from each residence to the designated primary and secondary shelters, and backup linkages, which serve as alternatives in the event of road blockages or fire spread. This dual linkage structure enhances the resilience and continuity of evacuation operations under uncertain wildfire conditions.

- Risk-aware allocation: Wildfire risk indices, quantified from topographic and environmental factors such as slope, forest density, and proximity to forests, are incorporated into the shelter allocation model. This ensures that shelters in high risk zones are deprioritized, leading to safer and more reliable evacuation planning.

The proposed model addresses the limitations of conventional evacuation approaches by introducing a resilient optimization structure that simultaneously determines primary and secondary shelters while incorporating backup linkages to maintain continuity under uncertain wildfire conditions. A case study conducted in a rural county of Korea applies real topographic and population data to demonstrate the model’s effectiveness and practical applicability. The results highlight its potential to support the development of region-specific, data-driven evacuation strategies that strengthen community resilience against large-scale wildfires.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews previous studies related to wildfire evacuation planning and optimization-based disaster management models. Section 3 introduces the proposed integrated optimization model for the wildfire evacuation planning problem addressed in this study, including the problem definition and model formulation. Section 4 presents a case study conducted in Uiryeong County, Korea, describing the data collection process, model implementation, and key results. Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of the main findings and provides insights for practical applications and future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evacuation Planning: Context and Core Research Themes

Evacuation planning is a fundamental disaster management strategy aimed at minimizing human casualties during both natural and human-induced disasters. As urbanization and climate change have intensified the scale and frequency of such events, the need for effective and timely evacuation system design has become increasingly critical [21,22]. Research on evacuation planning has evolved mainly around three interrelated areas: the analysis of disaster-specific evacuation characteristics [23,24,25], the modeling of human decision-making and behavior [26,27,28], and the design and evaluation of evacuation systems [29,30].

Studies on disaster-specific evacuation characteristics examine how the physical attributes of different hazards, such as floods [25], earthquakes [24], hurricanes [23], and wildfires, shape evacuation requirements for affected populations. In particular, wildfires spread rapidly and are difficult to predict, which necessitates strategies that reduce total egress time and secure timely evacuation under uncertain and dynamic conditions [31,32].

Research on evacuation decision-making and behavior focuses on the cognitive and social factors that influence when and how residents respond to evacuation warnings [33,34]. Variables such as pre-movement time, vehicle usage, and shelter choice preferences are commonly investigated through surveys, structural equation models, and agent-based modeling, enabling more realistic estimation of evacuation demand [35,36]. More recently, studies have incorporated the influence of social networks to model how evacuation decisions propagate within communities, emphasizing the role of communication and peer behavior in shaping collective dynamics [37,38].

Evacuation system design and evaluation address the physical and operational aspects of emergency response, including shelter location [14], optimal routing [39,40], and traffic management [41]. While early studies often assumed static environments, recent approaches integrate simulation and optimization to account for changing traffic conditions, blocked roads, and evolving hazard zones [42,43]. These advances contribute to adaptive, data-driven evacuation systems that can respond effectively to rapidly changing situations.

2.2. Optimization Approaches in Evacuation Planning

Various optimization techniques have been applied to enhance the efficiency of evacuation planning, with particular emphasis on three key decision areas: location, allocation, and routing [29,30]. In practice, work in this field concentrates on determining the optimal placement of evacuation facilities and on developing routing and allocation strategies that minimize overall evacuation time while improving system performance [21].

The facility location problem seeks optimal placement of essential infrastructure, such as evacuation shelters or relief supply centers, in order to minimize total evacuation distance or to determine the minimum number of facilities required to accommodate evacuees [44]. Early studies employed classical formulations such as the p-median and set covering problems [45,46], whereas more recent work has adopted location and allocation models that jointly consider shelter capacity and accessibility [47,48,49]. These models are frequently formulated using MIP and are widely used to optimize the spatial distribution of shelters within a region.

Routing and allocation problems, by contrast, determine how evacuees should be assigned from demand nodes to shelters and which routes they should follow to minimize travel time or congestion. Objectives typically include minimizing total evacuation duration or maximizing the number of evacuees reaching safety within specified time limits [50,51,52]. To capture temporal variation in road capacity and travel speed, network flow models are often employed [53,54]. These formulations represent time-dependent congestion and compute routes that reduce bottlenecks during large-scale evacuations.

Because disaster environments are inherently uncertain and time-dependent, recent optimization research increasingly incorporates uncertainty and dynamic conditions into evacuation models. Uncertainty integration addresses unpredictable elements such as road damage probabilities or fluctuations in evacuation demand. Stochastic optimization generates solutions that perform well on average across multiple scenarios [55,56,57], whereas robust optimization seeks solutions that maintain acceptable performance under worst-case conditions [58,59]. Dynamic integration, in turn, models temporal changes in traffic conditions, road capacity, and hazard boundaries throughout the evacuation process [60,61,62]. A time-expanded network representation explicitly incorporates the time dimension into the network and enables adaptive routing and allocation as conditions evolve [63]. Dynamic network flow models, in particular, are essential for continuously updating evacuation routes and minimizing congestion based on time-varying capacities and real-time information [64].

2.3. Wildfire Evacuation Planning and Optimization Approaches

Wildfires present distinct operational challenges for evacuation planning compared with hurricanes or floods. Fire spread can accelerate quickly and unpredictably under the influence of wind and terrain, which drastically shortens available evacuation time and makes the reduction in egress time critical for survival [65,66]. At the same time, the inflow of firefighting units and the outflow of residents share the same road network and create bidirectional traffic conflicts that reduce effective capacity [67]. Routes may also become blocked or hazardous due to flames and smoke, which requires planners to consider exposure to fire related risk in addition to travel time [64]. In regions with an extensive wildland–urban interface, such as many parts of South Korea, the proximity of forested areas and settlements increases the likelihood of large evacuations and complicates route choice on constrained road networks [9,10]. These characteristics highlight the need for models that capture dynamic, uncertain, and high risk conditions in wildfire contexts [15,68].

Optimization research tailored to wildfires builds on general evacuation models while accounting for rapid spread, uncertain road availability, and tight operational windows. At the tactical level, routing and scheduling formulations determine who moves, when, and along which routes as conditions evolve. Multiobjective MIP models developed in the context of the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires optimize late evacuee movements and resource use under short notice, and follow on work extends this to fleet routing and scheduling with realistic regional constraints [69,70]. Related goal programming approaches coordinate early supported evacuation for vulnerable populations while synchronizing relief distribution over a discretized time horizon [19].

At the strategic level, location models designate destinations before an event. Robust formulations, such as a p-center model under pressure, minimize worst case access distance to shelters across scenario sets that reflect plausible ignition locations and path blockages [18]. Complementary work at province scale identifies a network of wildfire host communities and shows that a relatively small set of hosts can cover a large share of at risk populations, which reduces decision burdens during no notice evacuations [20].

Several studies integrate interdependent decisions and time explicitly. A two-stage stochastic goal programming model couples suppression resource allocation with resident evacuation to reflect their interaction during an event [71]. Post wildfire cascading hazards have been addressed with a two-stage stochastic mixed-integer nonlinear model that schedules evacuation alongside debris flow mitigation [72]. In addition, time expanded network formulations cast wildfire evacuation as a maximum flow over a time grid and integrate fire perimeter information, which enables preplanned routes that can be updated as new data arrive. Trigger-based methods complement these models by combining spread predictions with egress times to indicate when to initiate evacuation [63].

Emerging data driven approaches pair optimization with learning to improve adaptivity. Recent studies leverage satellite imagery, graph neural networks, and multiagent reinforcement learning to generate evacuation paths that update with changing fire conditions. These methods can supply dynamic parameters and route recommendations to integer programming or network flow models in near real time [73].

2.4. Research Gap and Contributions

Recent studies on wildfire evacuations have advanced routing, scheduling, and simulation under dynamic traffic and evolving fire conditions. However, three gaps remain salient for large-scale evacuation planning in wildland–urban interface regions.

First, most optimization-based approaches either predesignate host communities or optimize a single tier of shelters, rather than jointly determining short term and long term destinations within one framework. For example, province scale studies identify networks of host communities for strategic evacuation but do not co-optimize immediate and sustained shelters in tandem [20]. Hierarchical shelter configurations have been explored in general disaster contexts, yet wildfire specific models that simultaneously optimize both tiers and their assignments are scarce [74].

Second, resilience is usually pursued through stochastic or robust routing and through real time re-routing on time expanded networks, but explicit main and backup assignments across shelter tiers are rarely embedded as structural decisions. Prior work on bushfire evacuations optimizes vehicle routing and scheduling under uncertainty and demonstrates the value of alternative routing, while recoverable robust formulations integrate location, allocation, and evacuation with recourse [69,70,75]. Time expanded network models with integrated wildfire information further enable rapid updates, yet they do not pre-specify paired main and contingency linkages across tiers [63].

Third, although wildfire risk indices and susceptibility maps are used in assessment and preparedness, they are less often internalized in location allocation and routing objectives or constraints for evacuation design. Recent studies quantify compound risk from wildfire exposure and limited shelter access and show how risk indices can guide planning [76], and multi hazard shelter studies integrate susceptibility maps into optimization [77]. Still, wildfire specific optimization that embeds shelter level risk directly in the decision model remains limited [78].

To address these gaps, this study proposes an integrated optimization model that (i) Jointly determines primary and secondary shelters and their allocations in a single two-stage model, (ii) Plans resilient evacuations by assigning main and backup linkages across both tiers so that flows can be shifted when conditions deteriorate, and (iii) Incorporates a shelter risk index so that high risk facilities are deprioritized in location and allocation decisions. The framework is tailored to wildfire contexts and is implemented and evaluated with real regional data from Korea in a systematic county-scale case study.

3. Integrated Optimization Model of Wildfire Evacuation Planning

This section defines the wildfire evacuation planning problem addressed in this study, presents the optimization model developed to solve it, and states the key assumptions and structural components of the proposed model.

3.1. Problem Description

South Korea has recently experienced several large-scale wildfires that forced entire counties and small cities to evacuate. These events highlight the need for a systematic model capable of managing wide-area population movements under rapidly evolving wildfire conditions. The objective of this study is to design a resilient evacuation system that minimizes exposure and ensures resident safety when extensive rural regions are affected.

Evacuation operations are organized at the village unit level, where each village, typically comprising several dozen to several hundred residents, serves as a single evacuation unit. This scale reflects the social and administrative structure of rural counties and enables coordinated evacuation planning tailored to small communities.

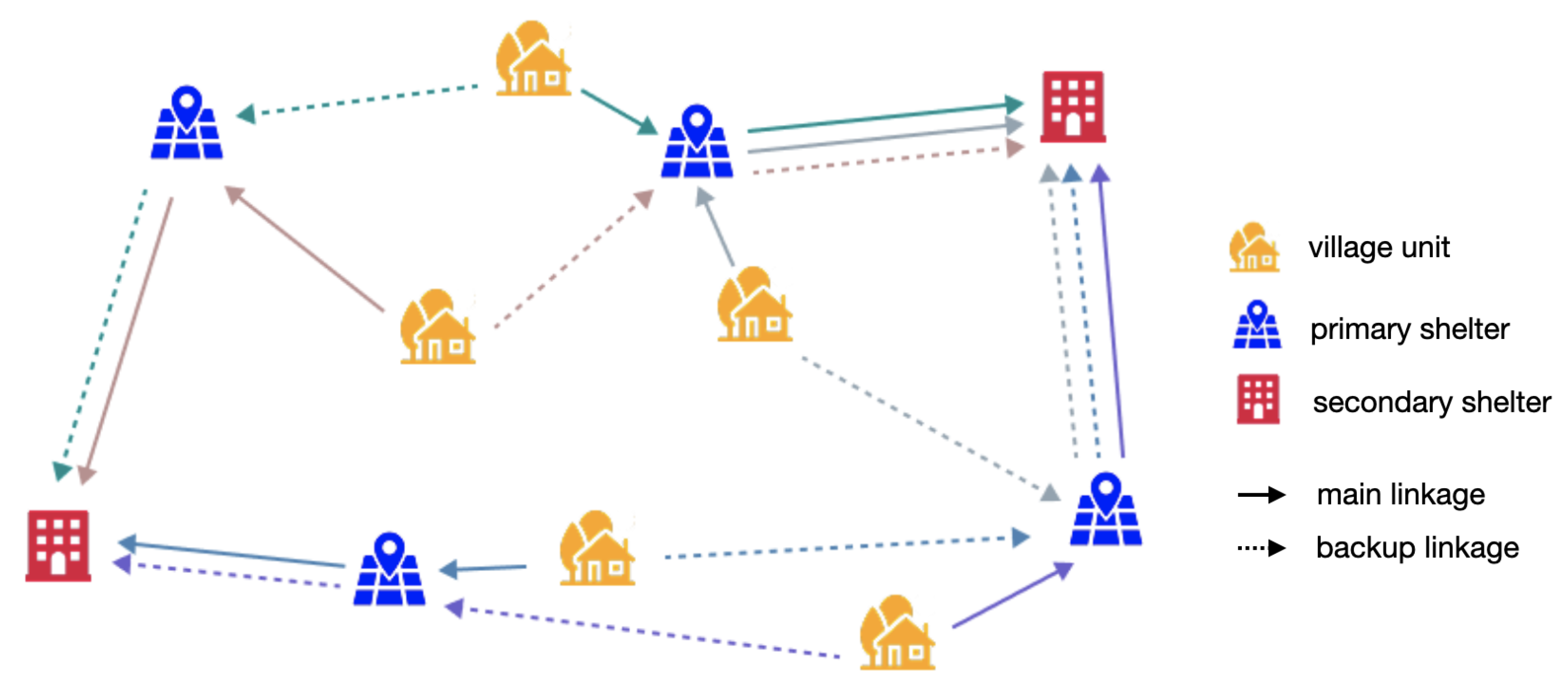

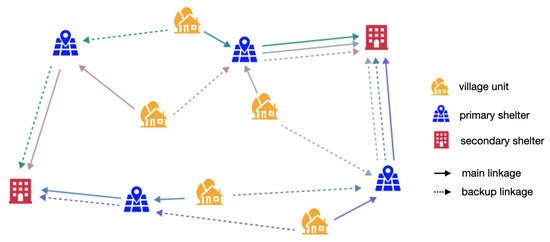

The model assumes a two-stage evacuation process (Figure 1). In the first stage, village residents move to nearby primary shelters that provide immediate safety during the early phase of fire expansion. Such facilities are open and easily accessible spaces, for example parking lots, public squares, or vacant grounds, that residents can reach quickly on foot or by the most accessible means. In the second stage, evacuees are transported from primary shelters to secondary shelters by large vehicles. Secondary shelters are larger, enclosed facilities such as schools, community centers, or gymnasiums that support longer stays and essential services after the immediate danger subsides. Villages that already contain a designated secondary shelter are considered sufficiently safe and therefore do not require a second transfer, whereas other villages are assigned to appropriate secondary shelters identified by the model.

Figure 1.

Illustration of two-stage wildfire evacuation. Each arrow color indicates the evacuation routes from a different village unit.

This two-tier structure is particularly rational in wildfire contexts because the time available for evacuation is highly limited and road conditions can deteriorate rapidly. Immediate relocation to a nearby open space drastically reduces exposure risk during the critical early minutes of fire spread, while the subsequent transfer to well-equipped facilities allows for organized management, medical support, and longer-term accommodation once the situation stabilizes. Moreover, designating primary shelters as intermediate collection points facilitates the coordination and dispatch of transport vehicles to secondary shelters, enabling a more orderly and efficient large-scale transfer process. This staged configuration aligns with the dynamic nature of wildfire threats and the limited mobility in rural regions, ensuring that evacuation remains both timely and operationally feasible.

Both primary and secondary shelters are selected from predefined candidate sets, and their selection simultaneously balances distance, capacity, network connectivity, and wildfire risk. Unlike sequential approaches that determine shelter types in separate steps, the proposed model jointly optimizes the locations of both shelter tiers to achieve spatial balance and minimize the overall evacuation burden.

Because shelters, particularly those located near forests, can themselves be threatened, each primary shelter candidate is evaluated using a quantitative wildfire risk index derived from topographic and environmental variables such as slope, elevation, vegetation, and proximity to forest edges. This index is embedded in the model to discourage or exclude high-risk candidates and promote safer allocations.

Potential disruptions to evacuation linkages caused by fire spread, smoke, or road damage are also explicitly considered. Each village is assigned a main evacuation linkage and a backup linkage. The main linkage represents the standard connection from the village to its designated primary and secondary shelters, while the backup linkage provides an alternative route if the main linkage becomes inaccessible. As illustrated in Figure 1, solid arrows indicate main linkages and dashed arrows represent backup linkages, visually highlighting the dual-linkage structure of the proposed system. To maintain reliability, a portion of shelter capacity is reserved to accommodate evacuees redirected from disrupted linkages. This dual linkage structure enhances the resilience and adaptability of evacuation operations under dynamic wildfire conditions.

In summary, the problem involves determining the locations of primary and secondary shelters, assigning villages to both shelter tiers, and establishing main and backup linkages while satisfying capacity, distance, connectivity, and wildfire risk constraints. The objective is to minimize overall evacuation burden while accounting for risk factors and ensuring reliable and practical operations across a wide rural region. The proposed model provides a comprehensive and resilient framework for wildfire evacuation system design, supporting practical decision-making for large-scale rural areas.

3.2. Optimization Model

Building on the problem described in the previous subsection, we formulate the wildfire evacuation planning problem as an MIP model. The model simultaneously determines primary and secondary shelter locations, village to shelter assignments, and main and backup linkages within a single mathematical framework. The objective is to minimize total evacuation distance, subject to risk aware constraints on shelter safety, accessibility, capacity, and connectivity. In this way, the model serves as a data-driven and resilient decision support tool for optimizing wide-area evacuation planning under complex and uncertain wildfire conditions.

The mathematical symbols, sets, parameters, and decision variables used in the formulation are summarized in Table 1 for reference.

Table 1.

Notations.

The optimization model for the wildfire evacuation problem is then presented as follows.

The objective Function (1) minimizes the total evacuation distance for all residents by simultaneously considering the distances from each village to its assigned primary and secondary shelters. The weighting factor controls the relative importance of the secondary evacuation distance compared to the primary evacuation distance, allowing balanced consideration of both short-range and long-range movements within the overall evacuation process.

Constraints (2) and (3) ensure that each village selects exactly one main and one backup linkage, each representing a unique combination of a primary and a secondary shelter pair. Constraint (4) guarantees that the same primary shelter cannot be selected simultaneously by both the main and backup linkages of a given village. This prevents the duplication of evacuation flows through a single primary shelter and ensures route diversification, which enhances robustness under uncertain wildfire conditions.

Constraints (5) and (6) impose capacity restrictions on primary and secondary shelters, respectively. The total number of evacuees assigned to a shelter cannot exceed its maximum capacity. The parameter represents a buffer ratio between 0 and 1 that accounts for the uncertainty of actual evacuee inflows through backup linkages. Because the number of residents who may eventually use backup routes cannot be precisely predicted due to wildfire-induced road blockages or shelter inaccessibility, a fraction of the population assigned to backup linkages is conservatively included in the capacity calculations to secure sufficient margin for possible emergency relocations under rapidly changing fire conditions.

Constraints (7) and (8) regulate the allowable travel distance of backup linkages relative to the main linkages. The parameter defines the maximum acceptable ratio between backup and main evacuation distances for both primary and secondary shelter connections. Since backup routes are generally longer than main routes, is set as a constant greater than one to ensure that the backup travel distance remains within a reasonable range under emergency conditions.

Constraint (9) limits the overall wildfire risk level of the selected primary shelters. It restricts the population-weighted sum of wildfire risk indices to an upper bound , ensuring that shelters located in high-risk areas are discouraged from selection. Since primary shelters are typically situated closer to forested zones than secondary shelters, it is essential to consider the relative wildfire risk of each site when determining evacuation linkages and shelter assignments. The wildfire risk index is expressed between 0 and 1, representing the relative risk level of each primary shelter, and the upper bound also ranges between 0 and 1, indicating the allowable average risk level among all selected primary shelters.

Constraints (10) and (11) restrict shelter operation decisions based on their connection to main evacuation routes. In this model, a shelter can be selected ( or ) only when it is assigned through at least one main linkage. Shelters connected solely through backup linkages are not activated in the evacuation plan, since maintaining facilities that are never used in normal evacuation scenarios would impose unnecessary administrative and financial burdens. This condition reflects a practical planning principle that shelters are operated only when they serve as primary evacuation destinations.

Constraints (12)–(15) ensure logical consistency between shelter selection and linkage decisions by allowing a village to be connected only to primary or secondary shelters that are selected for inclusion in the evacuation plan.

Constraint (16) limits the total number of secondary shelters to a predefined upper bound , reflecting practical constraints in operating large-scale evacuation facilities. Because secondary shelters are designed to accommodate a significant number of evacuees within urban or centralized areas, their establishment requires considerable resources such as budget, personnel, and logistics. This constraint therefore ensures that the total number of secondary shelters remains within a feasible and manageable range.

Finally, Constraints (17)–(19) define the binary nature of all decision variables. Overall, the proposed model provides an integrated optimization framework that jointly determines the locations and assignments of primary and secondary shelters while incorporating capacity limits, wildfire risk levels, and operational constraints. By accounting for both main and backup linkages, the model supports practical and resilient evacuation planning for large-scale wildfire events.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed simultaneous optimization framework, we conducted a preliminary test comparing it with a sequential optimization Benchmark. This benchmark approach decomposes the problem into two phases: it first solves an optimization problem to assign primary shelters solely based on immediate proximity, fixes these decisions, and subsequently allocates secondary shelters. Given the high computational complexity of the original formulation, this test was performed on a small-scale instance (), which represents a subset of the dataset analyzed in the subsequent case study section. The results illustrated the clear trade-offs involved in the optimization process. The sequential method achieved the minimum possible primary evacuation distance but led to a drastic increase in the secondary evacuation distance due to disjointed decision-making. In contrast, the integrated model accepted a compromise in the first stage to achieve global efficiency. Specifically, while the integrated model resulted in an increase in the primary evacuation distance by approximately 34% compared to the sequential benchmark, it achieved a substantial reduction of 33% in the secondary evacuation distance. Consequently, this trade-off led to an overall 12% reduction in the total weighted objective value. This outcome confirms that optimizing the entire hierarchical network simultaneously is essential for ensuring overall system efficiency, justifying the integrated formulation despite its computational demands.

3.3. Model Simplification

The original formulation, which explicitly models the full linkage structure between villages, primary shelters, and secondary shelters, includes two types of three-dimensional assignment variables: for main evacuation linkages and for backup linkages. Given the size of the study region and the number of candidate shelters, the full model contains an extremely large number of decision variables and constraints, resulting in very high computational complexity. As a result, solving the model with standard MIP solvers becomes infeasible for large-scale regional applications. To overcome this limitation, a simplified formulation is developed to reduce the dimensionality of the problem while maintaining its key structural characteristics.

In the simplified model, each three-dimensional variable is decomposed into two independent sets of binary variables corresponding to each evacuation stage. Specifically, and represent the main and backup assignments between village i and primary shelter j, while and represent the corresponding main and backup assignments between village i and secondary shelter k. This decomposition significantly decreases the number of decision variables from to , making the problem computationally tractable while preserving the two-stage evacuation structure and the main–backup relationship.

Since the explicit linkage between primary and secondary shelters is no longer available, the direct distance between them cannot be computed. To approximate this, the model defines a modified secondary evacuation distance representing the second-stage travel from each village to a secondary shelter:

where is the primary shelter nearest to village i. Thus, indicates the secondary evacuation distance from village i to secondary shelter k, measured as the distance between its nearest primary shelter and the corresponding secondary shelter. Since the distance between primary and secondary shelters is generally longer than that between villages and primary shelters, and residents tend to evacuate to one of the nearby primary shelters, this approximation is expected to have a limited effect on the overall objective function while substantially reducing the computational complexity of the model.

Accordingly, the new objective function minimizes the population-weighted sum of the first- and second-stage evacuation distances as follows:

A similar structure is applied for backup linkages using and , with corresponding constraints defined in the same way as in the original model. Based on these revised decision variables and the approximated distance parameter , the complete formulation of the simplified model is presented as follows.

All constraints in the simplified model are direct transformations of those in the original formulation, rewritten using the newly defined variables and distance parameters. Specifically, constraints (23)–(26) correspond to (2) and (3), defining the assignment of villages to shelters in both evacuation stages. Constraint (27) corresponds to (4), which prevents each village from being simultaneously assigned to the same primary shelter in both the main and backup linkages. Constraints (28) and (29) are derived from (5) and (6), representing the capacity limits of primary and secondary shelters. Constraints (30) and (31) correspond to (7) and (8), ensuring reasonable backup linkage distances relative to the main routes. Constraint (32) corresponds to (9), which incorporates the wildfire risk level into the primary shelter selection process. Constraints (33) and (34) are derived from (10) and (11), linking shelter selection variables to their usage decisions. Constraints (35)–(38) correspond to (12)–(15), defining the logical consistency between the selection and assignment variables for both primary and secondary shelters. Constraint (39) corresponds to (16), which restricts the total number of secondary shelters that can be established. Finally, constraints (40)–(43) correspond to (17)–(19), specifying the binary nature of the decision variables.

This simplified formulation maintains the essential logic of multi-stage and multi-linkage evacuation planning while achieving a substantial reduction in computational complexity, enabling practical application to large-scale regional evacuation problems.

To validate the approximation of secondary evacuation distances, we analyzed a small-scale test instance. While total objective values exhibited high variability due to the small instance size, two key observations confirmed the structural validity of the model. First, the simplified model consistently prioritized closer primary shelters, effectively capturing the hierarchical evacuation logic. Second, we compared the approximated secondary evacuation distances utilized in the objective function against the actual travel distances corresponding to the derived evacuation plan. The analysis revealed that the deviation was approximately less than 5%. This high accuracy demonstrates that the simplified formulation provides a precise representation of the network, justifying its use for computationally tractable large-scale planning.

4. Case Study

This section applies the proposed optimization model to a real-world case study of Uiryeong County, Korea, to demonstrate its effectiveness and practical applicability for large-scale wildfire evacuation planning.

4.1. Study Area Description

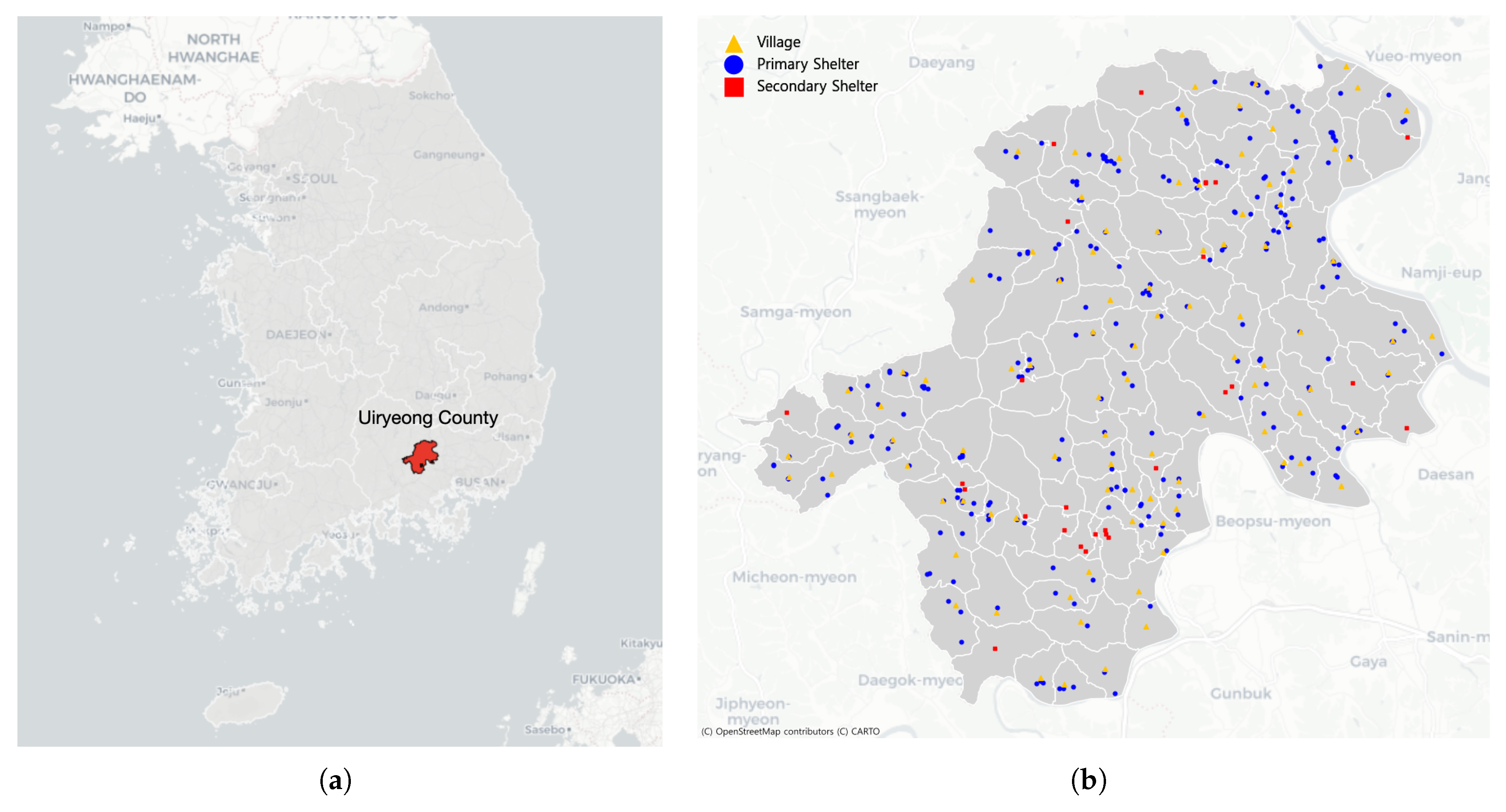

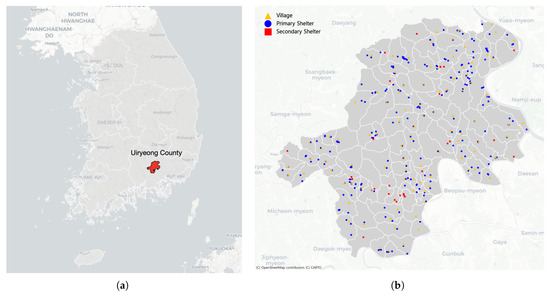

Uiryeong County, located in Gyeongsangnam-do Province in southeastern Korea and shown in Figure 2a, was selected as the study area for model implementation. The county has a population of approximately 25,000 and covers an area of about 480 km2, with more than 60% of the land classified as forested or mountainous. The terrain is characterized by narrow valleys surrounded by steep hills, and residential villages are dispersed along major roads and river basins. This geographical configuration, combined with limited transportation infrastructure, makes the region highly susceptible to wildfire propagation, as fires can spread rapidly along ridgelines and wind corridors connecting forested areas to settlements.

Figure 2.

(a) Geographical location of Uiryeong County. (b) Spatial distribution of villages and shelter candidates. Data source: © OpenStreetMap contributors, ODbL.

In recent years, several large-scale wildfires in neighboring provinces have shown that even sparsely populated counties can experience substantial evacuation demands under extreme fire conditions. Uiryeong County consists of one central town and several rural townships, each containing multiple administrative villages that collectively reflect the spatial and demographic characteristics of a typical county-level region in Korea. These features present significant challenges for coordinated and efficient evacuation planning.

Therefore, Uiryeong County was chosen as a representative case study to test the proposed optimization model, as it embodies the key geographical, administrative, and infrastructural attributes of many wildfire-prone rural counties in Korea and provides a realistic setting for evaluating scalable and resilient evacuation planning strategies.

4.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

In this study, each administrative village within Uiryeong County was defined as a single evacuation unit, represented by the set I. A total of 116 villages were initially identified within the county, among which 20 villages located in urbanized or otherwise safe areas sufficiently distant from forest boundaries were excluded from the evacuation analysis. Consequently, 96 villages were used as effective evacuation units in the model. Villages in this region typically consist of several dozen to a few hundred residents and serve as the smallest administrative and social units for emergency coordination. This level of granularity provides a practical basis for community-scale evacuation planning.

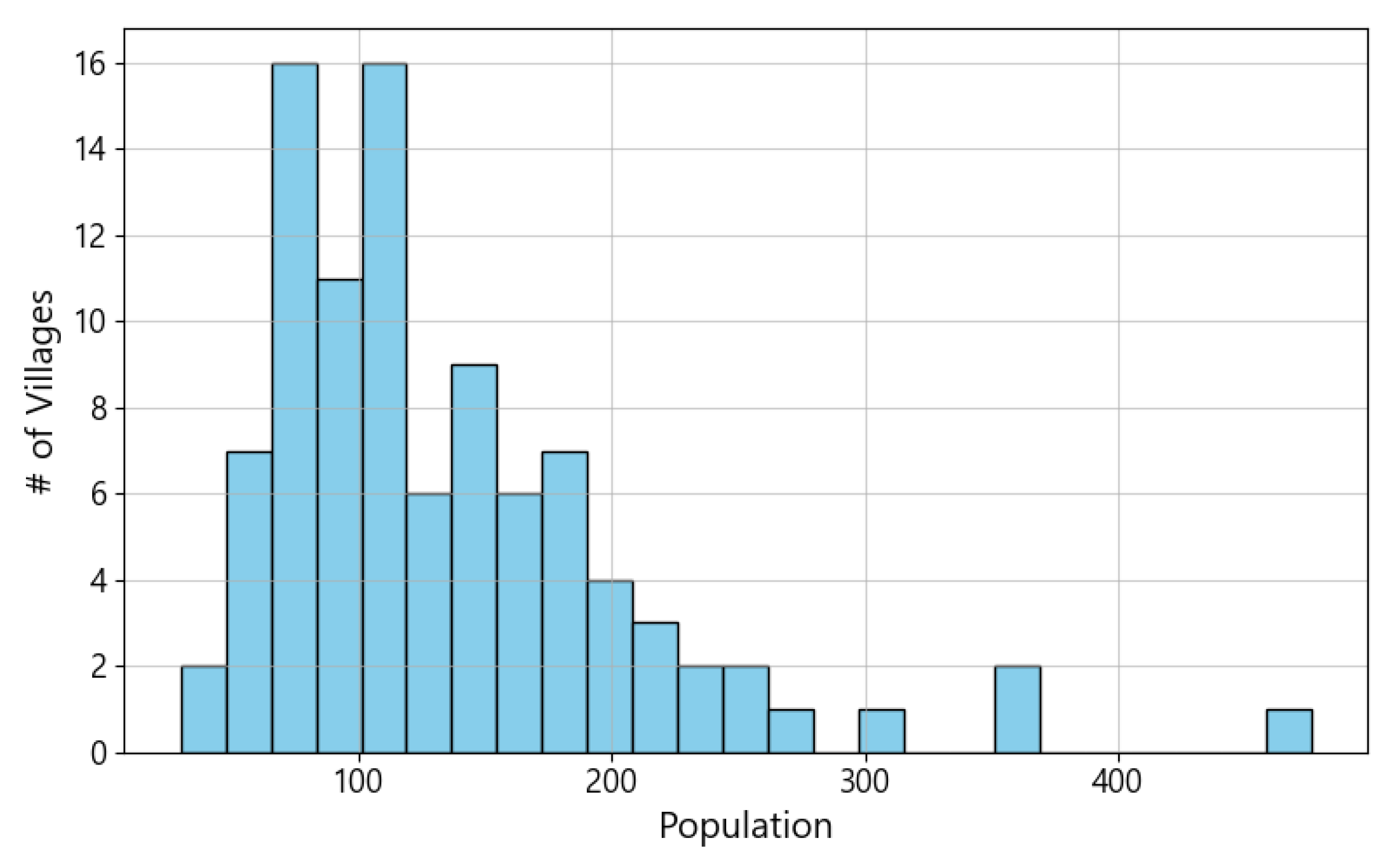

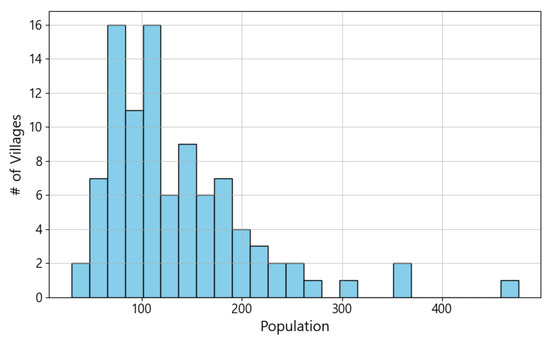

Population data for each village, denoted as , were obtained from the most recent census published by Statistics Korea (KOSTAT) [79], representing the number of residents requiring evacuation from each village. Figure 3 presents the distribution of , highlighting the variation in population size among villages. The main residential clusters within each village were identified from high-resolution settlement data and used as representative points for computing travel distances to shelter candidates, ensuring that the spatial configuration of the model accurately reflects the actual population distribution.

Figure 3.

Population distribution by village unit, where # denotes the number of villages.

Candidate primary shelters, represented by the set J, were identified through spatial inspection of Google Earth and Naver Map satellite imagery [80,81]. A total of 235 candidate sites () were identified across the study area. These shelters are defined as outdoor spaces that can be reached on foot from nearby residential areas, providing immediate refuge during the early phase of a wildfire. Typical examples include community centers, parking lots, schoolyards, small parks, and public plazas located within or near residential zones. Their primary role is to ensure rapid and safe temporary protection while residents prepare for relocation to larger, more secure secondary shelters. The capacity of each primary shelter, denoted as , was estimated based on the open-space area measured from the same satellite imagery. The usable area for each site was converted into an estimated capacity based on the “Guidelines for the Designation and Management of Earthquake Outdoor Evacuation Areas” established by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety (MOIS) of South Korea [82]. These guidelines stipulate a minimum area of approximately 0.825 per person (calculated as 3.3 for 4 persons), which is specifically intended for short-term stays during earthquake evacuations. In this study, we adopted a standard of 1 per person, consistent with previous Korean evacuation analyses [83], which satisfies this government requirement while providing a slight margin. It is important to note that these shelters are designated primarily as temporary assembly points for immediate safety during the acute phase of a wildfire; thus, this high-density standard is feasible for short-term stays.

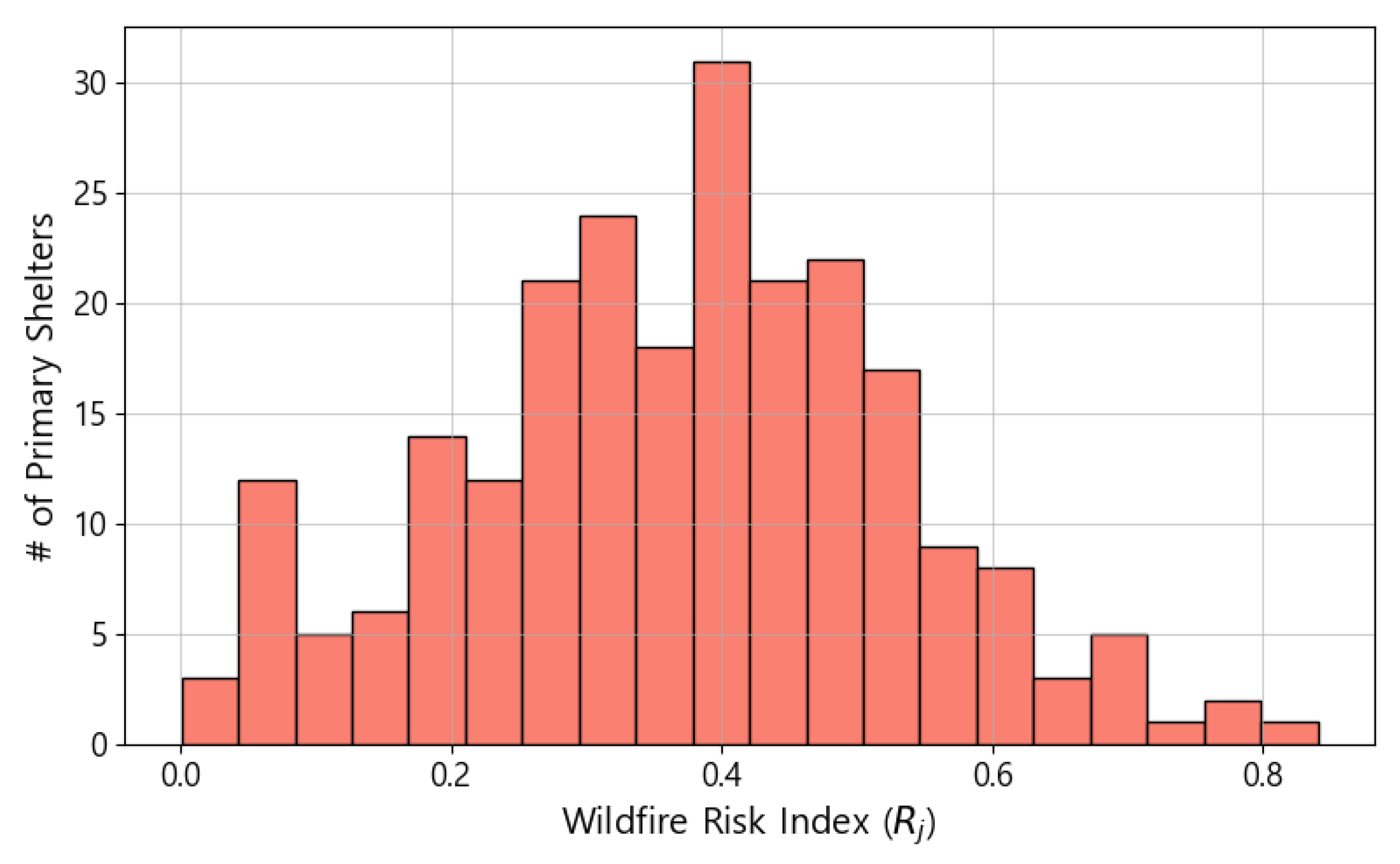

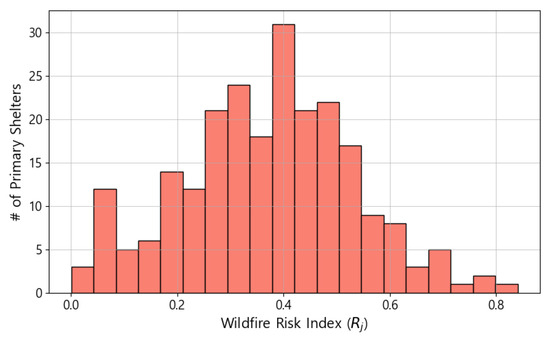

Because primary shelters are outdoor facilities, their safety is directly influenced by surrounding environmental conditions that affect wildfire spread. To incorporate this factor, a wildfire risk index() was developed for each candidate primary shelter using four spatial indicators: (1) proximity to the nearest forest, (2) forest density within a 100 m radius, (3) local slope, and (4) proximity to the nearest river or water body. These indicators collectively represent vegetation, topographic, and hydrological characteristics associated with wildfire exposure.

Spatial datasets were obtained from publicly available national geospatial data sources [84,85,86]. All indicators were standardized to values between 0 and 1, where higher values indicate greater wildfire susceptibility. The wildfire risk index for each primary shelter was calculated as follows:

where , , , and represent normalized indicator values corresponding to proximity to forests, forest density, slope, and proximity to rivers, respectively.

The coefficients in Equation (44) were determined by synthesizing the relative importance of wildfire risk factors as identified in previous quantitative studies using AHP [87,88]. These studies consistently establish a hierarchy where fuel characteristics are the primary drivers of susceptibility, followed by topographic variables. Accordingly, the highest cumulative weights were assigned to vegetation-related variables—proximity to forests (0.35) and local forest density (0.30)—to reflect the dominance of fuel continuity and load in forest–rural interface regions. Slope, which acts as a secondary driver accelerating fire propagation, was assigned a moderate weight (0.20). Conversely, proximity to rivers was given the lowest weight (0.15), acknowledging their potential function as natural firebreaks. While this weighting structure aligns with the empirical consensus, it is noted that future research should aim to further refine these parameters using data-driven approaches to rigorously calibrate the coefficients based on local historical fire data.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of the calculated wildfire risk index values for all candidate primary shelters. Most shelters exhibit moderate risk levels, while a small number show relatively high values, indicating exposure to dense vegetation or steep terrain near forest boundaries.

Figure 4.

Distribution of wildfire risk index () values for primary shelter candidates, where # denotes the number of primary shelters.

Secondary shelters represent large, well-equipped facilities designed to accommodate evacuees for extended periods after the initial wildfire threat has subsided. Unlike primary shelters, which focus on rapid accessibility and short-term safety, secondary shelters are intended to provide long-term protection, essential services, and basic living conditions during extended evacuation periods.

In this study, candidate secondary shelters (K) were selected within urban and peri-urban areas of Uiryeong County. A total of 28 candidate facilities () were identified across the region. Facilities such as schools, indoor gymnasiums, community centers, and other public buildings were considered, as these locations possess the structural capacity and infrastructure to support large numbers of evacuees. Candidate sites were evaluated using publicly available facility information and local building data, focusing on accessibility, service availability, and safety from wildfire exposure. The usable area of each facility was obtained from building data and official records, and the capacity of each secondary shelter () was estimated based on a per-capita area requirement of 3 . This value reflects the temporary housing standard (2.6–3.6 per person) specified in the 2025 Disaster Relief Plan Guideline published by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety [89], representing an appropriate minimum for long-term shelter accommodation in this study.

Figure 2b shows the spatial distribution of all village units (I), primary shelter candidates (J), and secondary shelter candidates (K) within Uiryeong County. Both villages and primary shelters are widely distributed across the rural landscape, reflecting the dispersed settlement pattern of the region. Secondary shelters, shown in red, are concentrated around central and urbanized areas, providing regional hubs for large-scale evacuation support and coordination.

Finally, all distance parameters, including , , and , were calculated as the shortest-path distances between corresponding locations along the existing road network.

4.3. Results and Analysis

All computational experiments were conducted using the simplified MIP model developed in this study. The model was implemented in Python 3.13.2 and solved with Gurobi Optimizer version 12.0. Computations were carried out on a desktop computer equipped with an Intel Core Ultra 5 125H processor and 32 GB of RAM.

The original model was highly complex and computationally intensive. Even after several hours of execution, the solver could not obtain a feasible solution because of the high combinatorial complexity. By contrast, the simplified formulation contained approximately 50,000 binary decision variables and 75,000 constraints, enabling the solver to find an optimal solution within a few seconds. This result demonstrates that the simplified model effectively reduces computational complexity while maintaining the essential structure required for practical evacuation planning at the regional scale.

We now present the results of the case study and discuss the effectiveness of the proposed wildfire evacuation system. Two main analyses are conducted. First, the efficiency and resilience of the evacuation system are evaluated by examining the effects of incorporating main and backup routes, as well as the simultaneous determination of primary and secondary shelters. Second, a sensitivity analysis is performed to assess how variations in the wildfire risk threshold () and the maximum number of secondary shelters () influence the resulting evacuation plans and shelter allocations.

4.3.1. Analysis of Solution Behavior

The proposed optimization model includes five control parameters: , , , , and . These parameters collectively determine the balance between evacuation efficiency, safety, and resilience.

The proposed optimization model includes five control parameters: , , , , and , which collectively determine the balance between evacuation efficiency, safety, and resilience. The weighting coefficient controls the relative importance of the primary and secondary evacuation stages when calculating the total evacuation distance in the objective function. A smaller value places greater emphasis on minimizing the primary-stage travel distance, whereas a larger value increases the influence of the secondary-stage distance. In the Uiryeong County case study, variations in resulted in negligible differences in the overall evacuation distance across both stages. Accordingly, both stages were treated as equally important, and was fixed at for all experiments.

The upper bound on allowable wildfire risk for primary shelters () and the maximum number of secondary shelters () are treated as external constraints rather than tuning parameters. Since their effects are analyzed in the subsequent sensitivity analysis section, both parameters were fixed at their maximum allowable values, namely and , so that they did not impose additional restrictions on the optimization process.

Accordingly, the analysis focused on the remaining two parameters, and , to evaluate the model’s ability to effectively determine the allocation of shelters and the configuration of evacuation linkages. The parameter represents the proportion of evacuees assigned through backup linkages who are reserved within shelter capacity calculations. This parameter reflects the extent to which backup-linkage evacuees are pre-allocated within available capacity to account for potential disruptions during evacuation. The parameter defines the maximum allowable distance ratio of backup linkages relative to the corresponding main linkages, ensuring that backup connections are not excessively longer than the main ones.

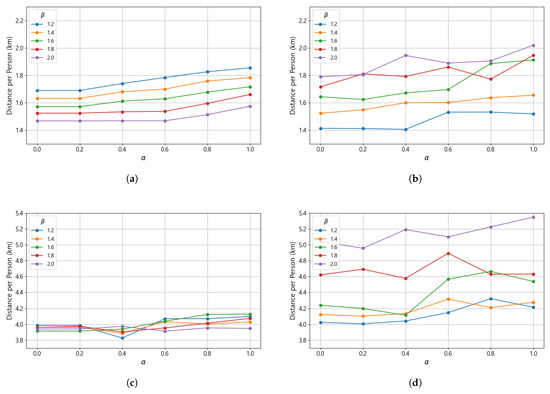

To analyze the effect of these parameters, was varied from to in increments of , and was varied from to in increments of . For each combination of and , the model was solved to optimality, and the resulting evacuation linkages were analyzed in terms of total travel distance and the effectiveness of backup linkage assignments under simulated disruption scenarios.

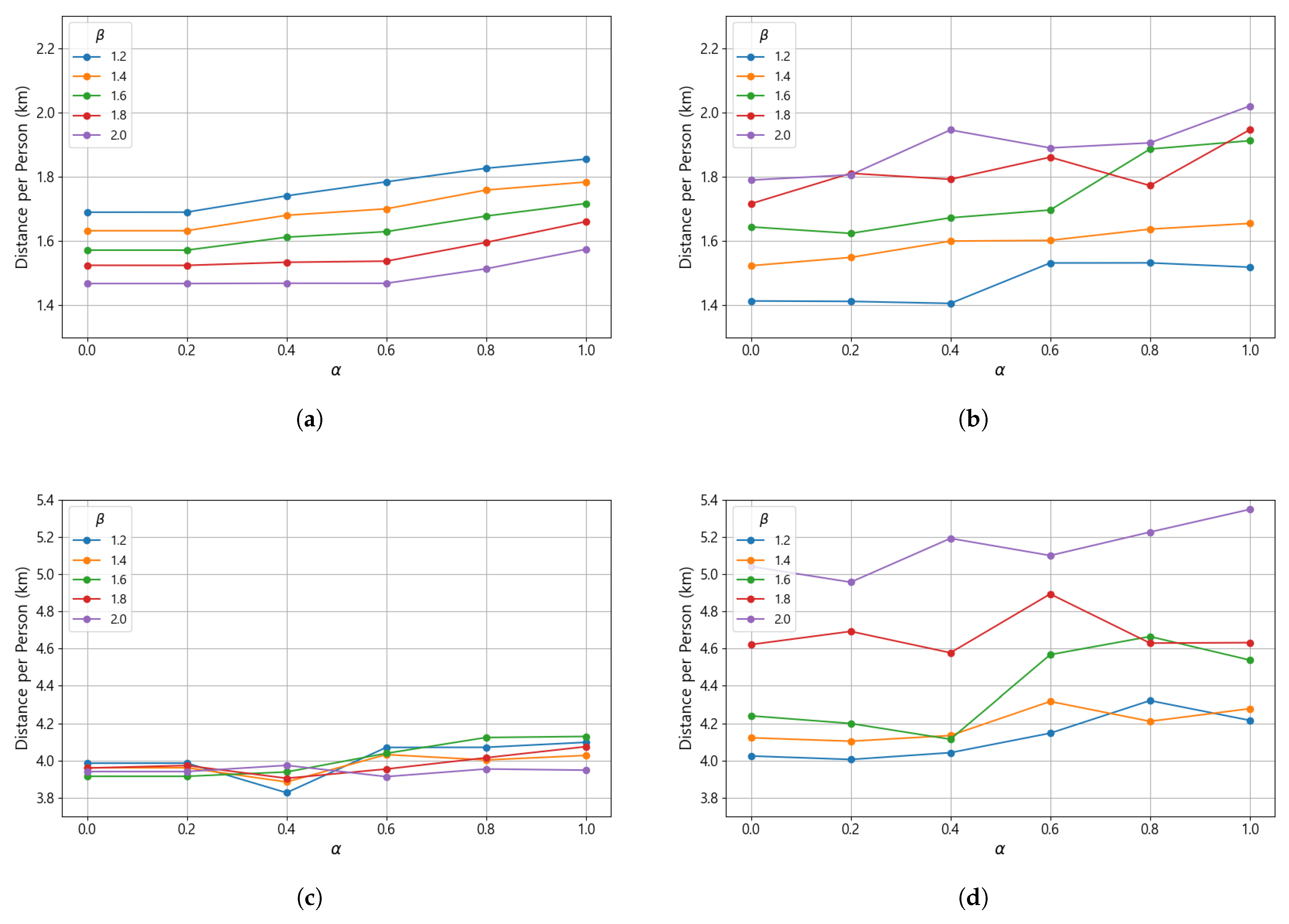

Figure 5 shows how the average travel distance per evacuee changes across the main and backup linkages as the parameters and vary. For this analysis, although the model uses approximated distances between primary and secondary shelters to reduce computational complexity, the travel distances summarized in Figure 5 are based on the actual road network distances computed between the selected shelters. For the main linkages, the average travel distance tends to increase as the value of becomes larger. This occurs because a higher means that a greater portion of each shelter’s capacity is reserved to account for potential use by evacuees assigned to backup linkages. As the reserved capacity expands, the effective capacity available for main-linkage assignments decreases, which forces some villages to be allocated to more distant shelters. Consequently, the overall travel distance for the main linkages increases.

Figure 5.

Changes in average evacuation distances under different combinations of and values. (a) Primary main linkage. (b) Primary backup linkage. (c) Secondary main linkage. (d) Secondary backup linkage.

A similar trend is observed in the backup linkages, since each backup linkage must remain within the distance ratio of its corresponding main linkage. When the main linkages become longer, the backup linkages also tend to increase in length. However, because the travel distance of the backup linkages is not directly included in the objective function, the influence of on backup-linkage distance is weaker compared to that on the main linkages. It is also noted that in some cases, the average distance of backup linkages slightly decreases as increases. This occurs when the redistribution of evacuees among shelters caused by increased reserve capacity results in a more spatially balanced allocation of backup linkages, thereby reducing the travel distance for certain villages.

On the other hand, as the value of increases, the average travel distance of main linkages for both the primary and secondary evacuation stages tends to decrease, while the average travel distance of backup linkages becomes longer. This indicates that when a larger is allowed, backup linkages can extend farther from their corresponding main linkages, enabling the optimization model to assign closer shelters to the main linkages and thereby reduce their travel distance.

An interesting observation is that when is smaller than approximately 1.6, the average travel distance of backup linkages becomes even shorter than that of the main linkages. This occurs because each village has only a limited number of nearby shelter candidates, and in cases where no suitable shelter slightly farther than the one selected for the main linkage is available, the model instead assigns a closer shelter as the backup linkage in order to satisfy the distance constraint imposed by . In the context of the proposed problem, it is generally reasonable for the main linkage to be shorter than the backup linkage, since the backup linkage serves as an alternative connection that is used only when the main linkage becomes inaccessible. Therefore, selecting an appropriate value of is important to ensure that this logical relationship is maintained while preserving realistic backup linkage assignments.

4.3.2. Effectiveness of Backup Linkages Under Disruption Scenarios

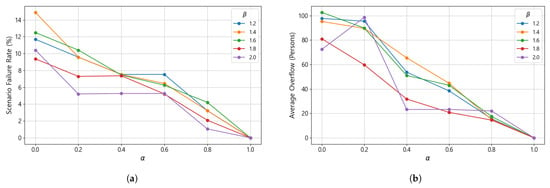

To evaluate the effectiveness of assigning backup linkages to each evacuation unit, a series of disruption scenarios was tested. Each scenario assumes that one primary shelter becomes unavailable, and all evacuees originally assigned to that shelter are redirected to their backup primary shelters. If the resulting reassignment causes any shelter to exceed its capacity, the scenario is classified as a failure. Accordingly, the total number of scenarios equals the number of primary shelters identified in the evacuation plan derived from the optimization model.

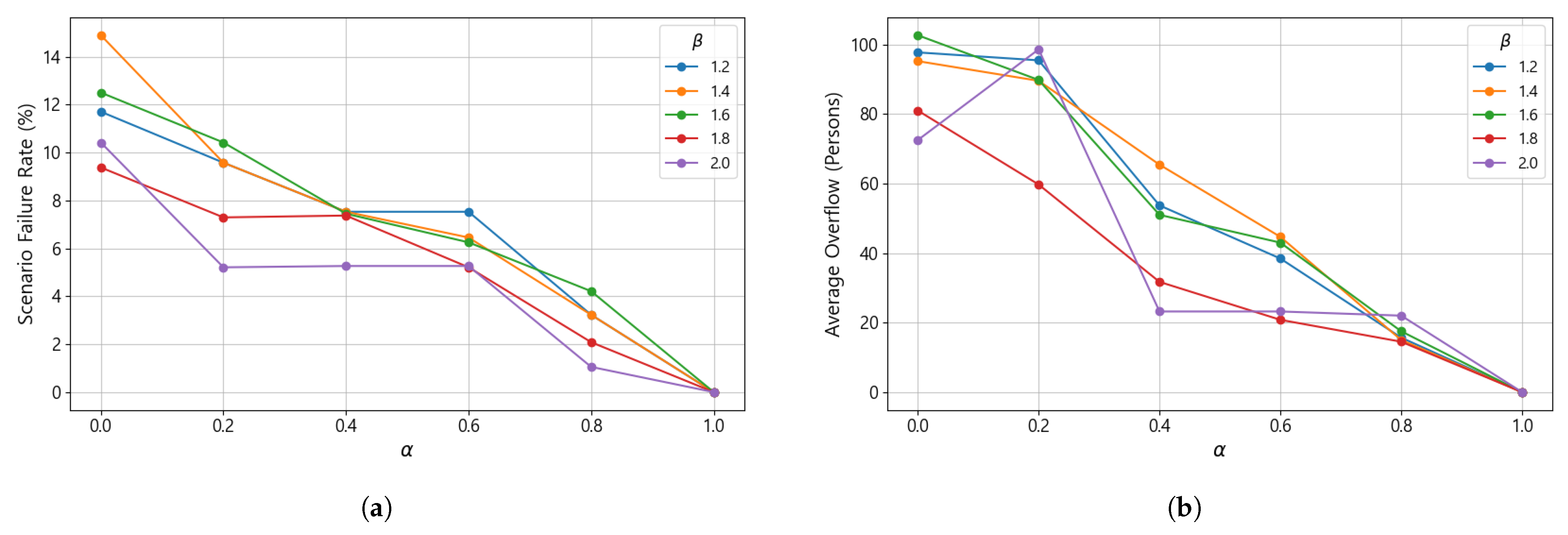

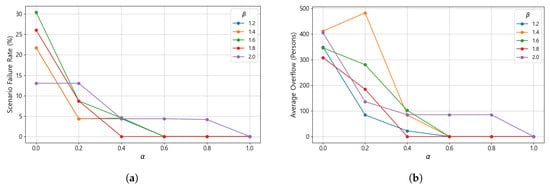

Figure 6a presents the proportion of failure scenarios as and vary, while Figure 6b shows the average number of evacuees exceeding shelter capacity in the failure cases. As shown in the figures, increasing , which represents the proportion of backup-assigned evacuees accounted for in shelter capacity, significantly reduces both the failure rate and the average excess population. Notably, when exceeds 0.6, both indicators drop sharply, indicating that reserving a sufficient portion of shelter capacity for potential rerouting greatly enhances system robustness. Similarly, when exceeds 1.6, the failure rate and excess population decline substantially. This trend is consistent with the result shown in Figure 5, where the average length of backup linkages exceeds that of main linkages once becomes sufficiently large. A higher value relaxes the distance constraint on backup routes, allowing them to extend farther from the main routes. This relaxation increases the number of feasible alternative shelters and consequently enhances the flexibility and robustness of the overall evacuation system.

Figure 6.

Effect of backup linkage allocation under primary-shelter disruption scenarios. (a) Scenario failure rate. (b) Average overflow of shelter capacity in failure cases.

Figure 7 illustrates similar analyses for secondary shelters. Because secondary shelters generally have much larger capacities, the effects of rerouting differ from those observed for primary shelters. As shown in Figure 7a, the failure rate is high (up to 30%) when , but it decreases sharply once increases to around 0.4. When and , no failure scenarios occur. Figure 7b also shows that the average excess population is initially large but drops dramatically when exceeds 0.4. These results indicate that, although secondary shelters are more resilient to disruptions due to their larger capacities, maintaining an appropriate reserve ratio remains essential for effectively absorbing unexpected reassignments under disrupted conditions.

Figure 7.

Effect of backup linkage allocation under secondary-shelter disruption scenarios. (a) Scenario failure rate. (b) Average overflow of shelter capacity in failure cases.

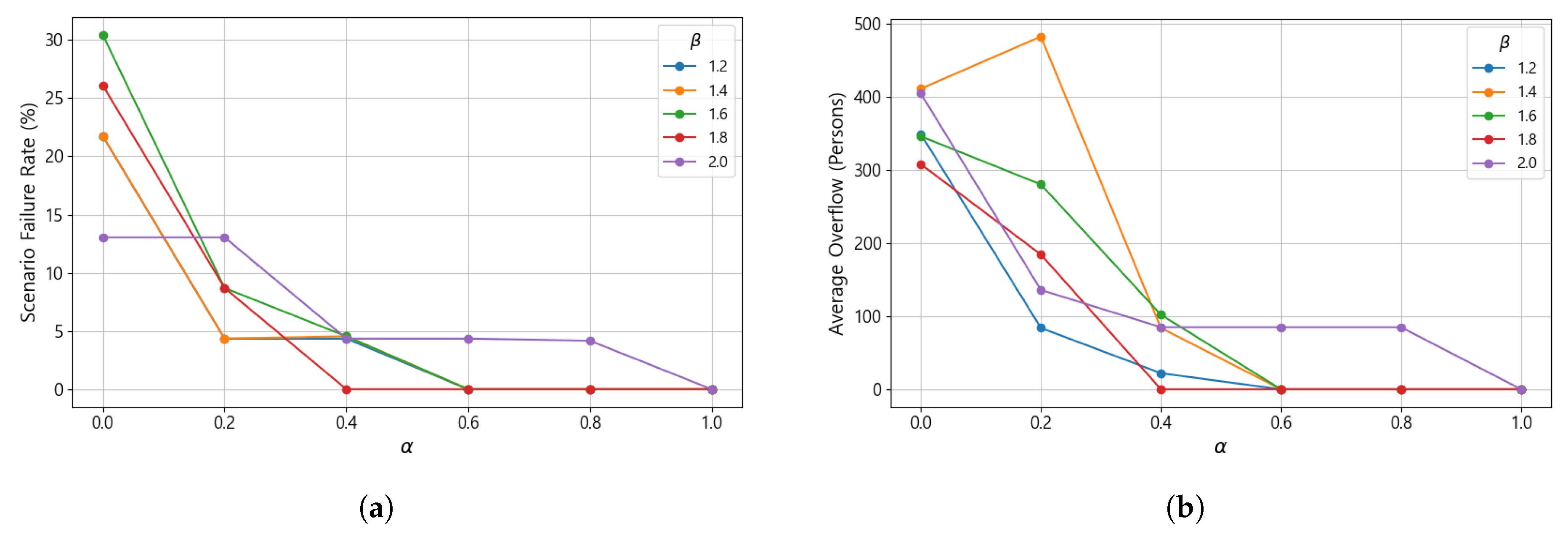

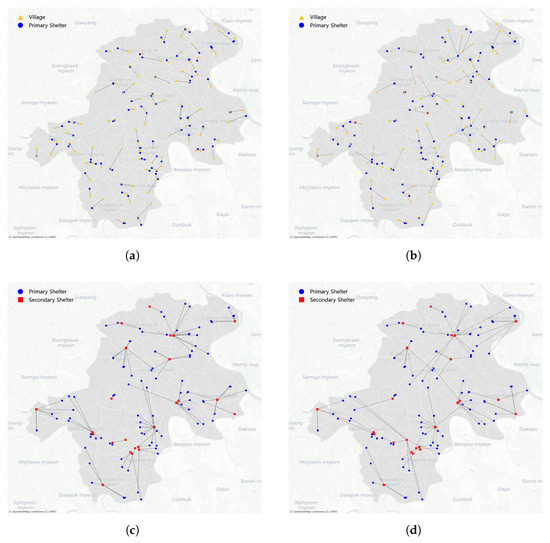

Figure 8 presents the main and backup linkage assignments for both primary and secondary shelters generated by the proposed model. The illustrated evacuation configuration corresponds to the case of and , which was identified as producing stable and effective system performance in the preceding analysis. For clarity of visualization, only the shelters selected and utilized in the optimized evacuation plan are displayed on the map.

Figure 8.

Evacuation shelter allocation obtained with and . (a) Primary main linkage. (b) Primary backup linkage. (c) Secondary main linkage. (d) Secondary backup linkage. Data source: © OpenStreetMap contributors, ODbL.

Figure 8 presents the main and backup linkage assignments for both primary and secondary shelters generated by the proposed model. The illustrated evacuation configuration corresponds to the case of and , which was identified as producing stable and effective system performance in the preceding analysis. For clarity of visualization, only the shelters selected and utilized in the optimized evacuation plan are displayed on the map. Figure 8a,b show the main and backup linkages between villages and primary shelters, while Figure 8c,d illustrate the corresponding linkages between primary and secondary shelters. Overall, the spatial configuration demonstrates that the optimized evacuation network forms locally clustered yet regionally connected shelter linkages, minimizing overall travel distances while ensuring alternative routing options. This pattern indicates that the proposed model successfully integrates spatial efficiency and redundancy, establishing a resilient evacuation structure capable of maintaining accessibility under disruptive conditions.

4.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

In the preceding analyses, the parameters and were treated as external constraints and were not explicitly considered within the model. In this subsection, a sensitivity analysis is conducted to examine how changes in these two parameters affect the evacuation outcomes. Based on the and values (0.6 and 1.8, respectively) that produced stable and effective evacuation results in the previous analysis, these parameters were fixed while and were varied to evaluate their influence on evacuation performance.

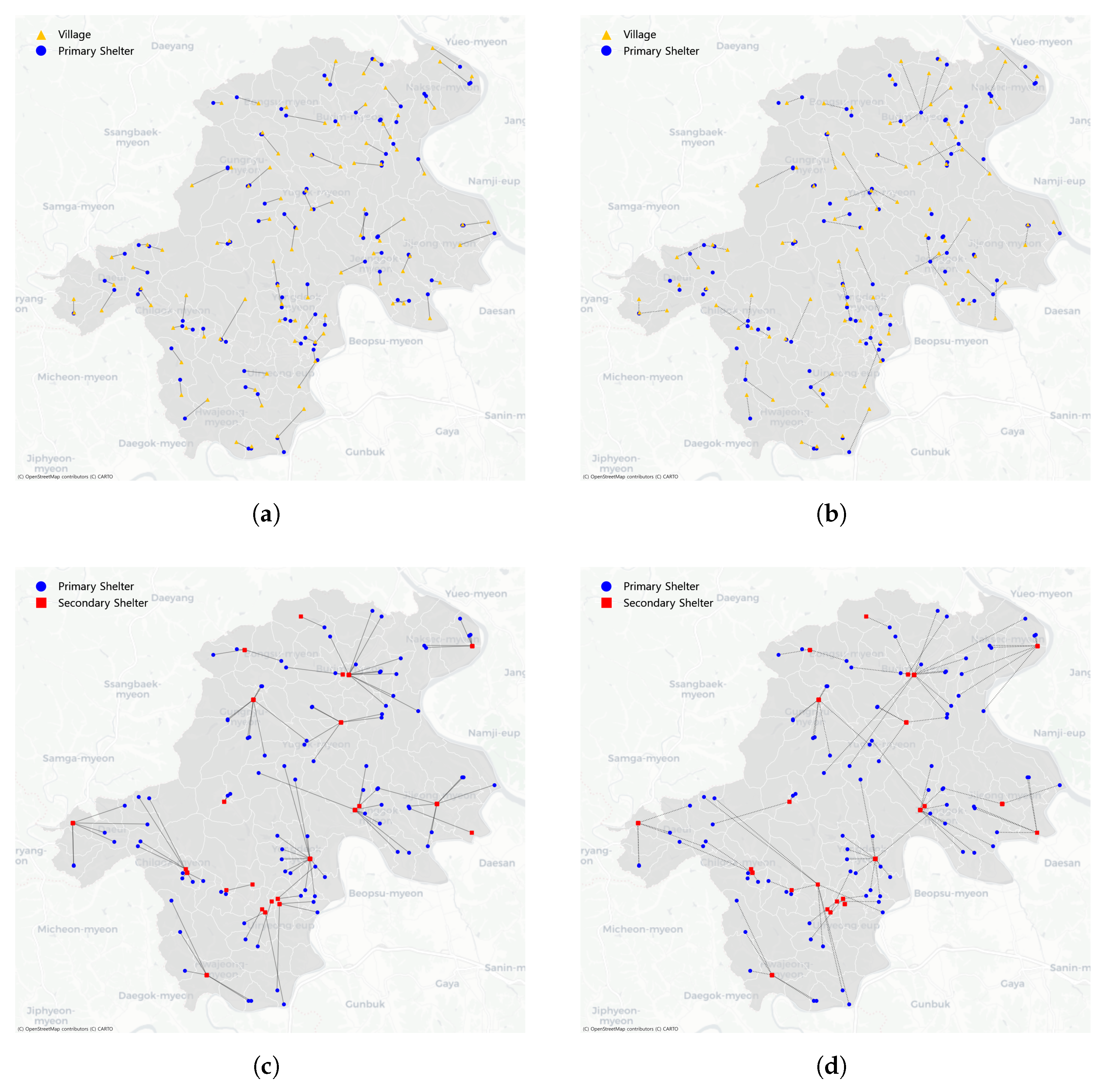

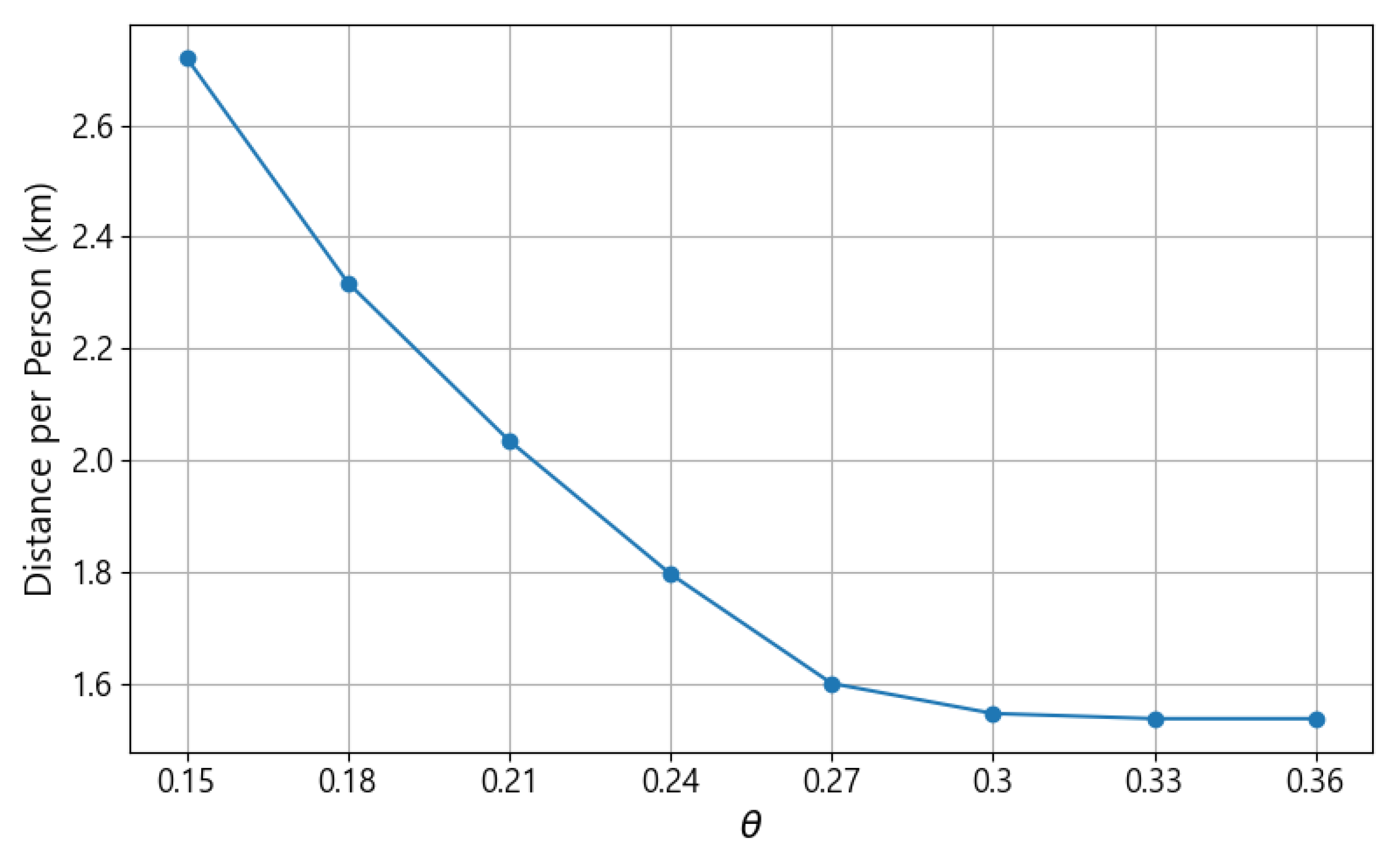

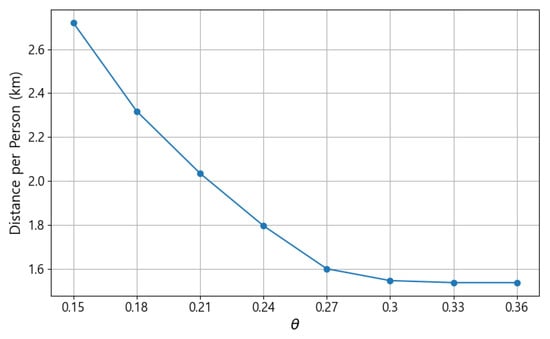

Figure 9 shows how the average evacuation distance per person for primary main linkages changes with different values of , which represents the upper bound of allowable wildfire risk for primary shelters. As increases, indicating a higher tolerance for shelter risk, the average evacuation distance decreases proportionally. When exceeds approximately 0.3, the reduction in distance becomes negligible, suggesting that beyond this point, relaxing the risk constraint no longer contributes to shorter evacuation routes. These results imply that setting around 0.3 provides a reasonable balance between minimizing travel distance and maintaining safety for evacuees at primary shelters. Therefore, this relationship can serve as a practical reference when establishing evacuation plans, helping planners adjust the acceptable risk level and travel distance of evacuees to an appropriate balance in real applications.

Figure 9.

Changes in the average evacuation distance of primary main linkages with varying values.

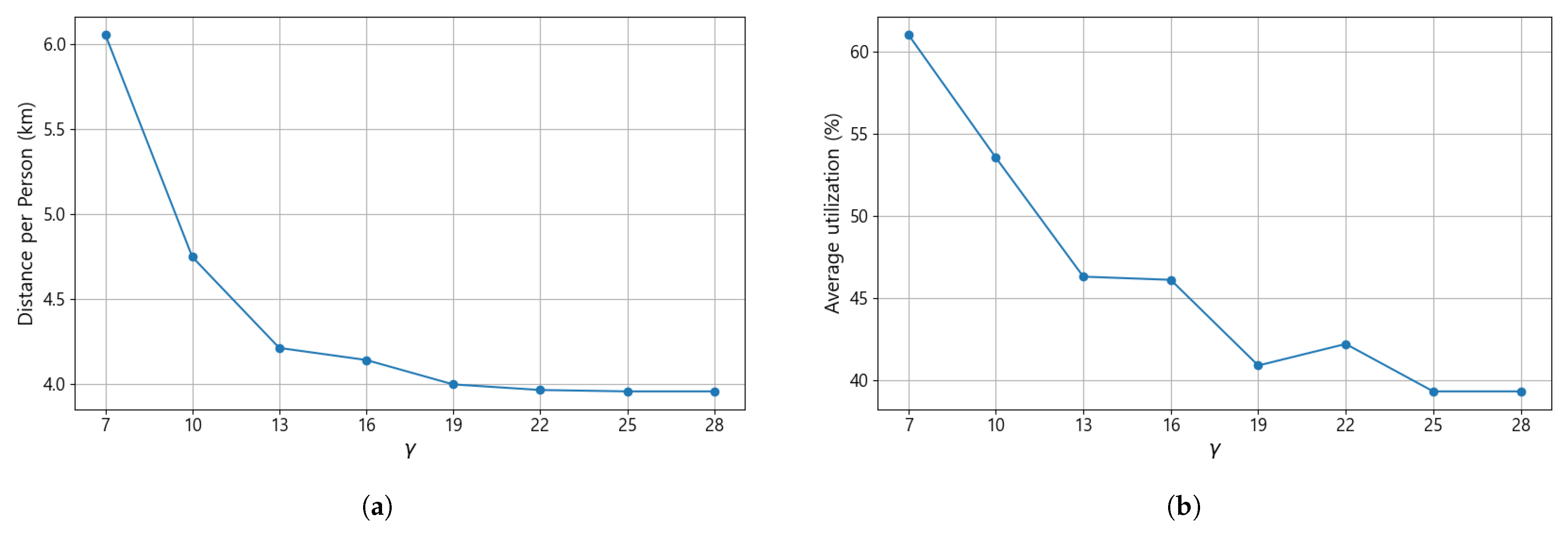

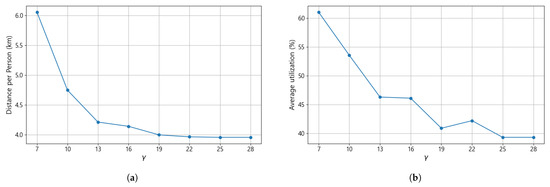

Next, the sensitivity of the model to the maximum number of secondary shelters, , is examined. Since secondary shelters are long-term accommodation facilities that require continuous maintenance and resource allocation, identifying an appropriate number to operate within budgetary and logistical constraints is essential.

Figure 10a illustrates how the average evacuation distance per person from primary to secondary shelters changes as varies. The average distance decreases sharply as increases up to approximately 13, after which it gradually levels off, forming an elbow shape around 19. Beyond this point, additional shelters yield minimal improvement in evacuation distance, indicating diminishing returns from further expansion.

Figure 10.

(a) Changes in the average evacuation distance of secondary main linkages with varying values. (b) Changes in the average utilization of secondary shelters with varying values.

Figure 10b presents the corresponding changes in the average utilization of secondary shelters. A similar pattern is observed, where the utilization rate converges to about 40% once exceeds 13, and shows little further reduction beyond . Therefore, maintaining the number of secondary shelters within the range of roughly 13–19 can be considered an operationally efficient and realistic strategy, balancing evacuation distance reduction with sustainable utilization levels. Accordingly, both the average evacuation distance and the average utilization rate should be jointly considered when determining the appropriate number of secondary shelters in practical evacuation planning.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed an integrated optimization model for designing a resilient wildfire evacuation system, addressing the need for efficient and coordinated evacuation planning across wide rural regions. The model simultaneously determines primary and secondary shelters and assigns main and backup linkages within a single mixed-integer programming framework. By embedding wildfire risk indices and capacity constraints, it provides a structured and risk-aware approach to large-scale evacuation planning.

The case study of Uiryeong County, South Korea, demonstrated the model’s capability to generate spatially balanced and practically applicable evacuation plans using real demographic and topographic data. The results confirmed that the proposed dual-linkage structure effectively enhances system robustness against potential disruptions such as road blockages or fire spread. The introduction of backup linkages significantly reduced the risk of shelter overload under simulated disruption scenarios, highlighting the importance of redundancy in ensuring continuity and reliability of evacuation operations.

In practical terms, the proposed framework can support local governments and emergency planners in pre-designating shelters, optimizing evacuation assignments, and evaluating the adequacy of existing shelter infrastructure. It also offers a quantitative basis for allocating limited disaster management resources, such as transport vehicles and staff, and for identifying priority areas where new shelters or access roads would most improve evacuation performance. These insights can inform the development of region-specific evacuation guidelines and strengthen community preparedness against large-scale wildfire emergencies.

While this study validated the framework in a rural context, the proposed model is designed to be transferable to diverse geographical settings. For urban applications, the framework can be adapted by recalibrating risk parameters, such as considering building density, and prioritizing road capacity constraints. However, applying this MIP formulation to large-scale urban networks may introduce computational complexity due to the increased number of decision variables. Future research should thus explore heuristic algorithms or decomposition methods to address scalability while ensuring computational efficiency.

Although this study focused on static strategic planning, the proposed framework serves as a powerful pre-planning tool that establishes a robust baseline for disaster management. To fully bridge the gap between strategic design and real-time operations, future research should focus on the sequential integration of optimization and simulation. Specifically, the optimal network configurations and shelter assignments derived from the current MIP model should be utilized as the initial input parameters for dynamic simulations, such as agent-based modeling. This methodological coupling allows for the rigorous evaluation of the system’s robustness under realistic, time-varying conditions. By simulating stochastic factors, such as unpredictable evacuee behavior, sudden traffic bottlenecks, and real-time fire spread, researchers can identify potential vulnerabilities in the pre-optimized network. Furthermore, evolving the framework into a rolling-horizon approach would enable adaptive decision-making, where evacuation routes are iteratively updated based on incoming data. Ultimately, these extensions will transform the model from a static planning document into a comprehensive, dynamic decision-support system capable of guiding resilient evacuation operations in rapidly evolving wildfire environments.

Overall, the proposed model contributes a comprehensive and data-driven decision-support framework for wildfire evacuation planning. Its integration of multi-stage shelter selection, risk considerations, and redundant linkages offers both theoretical and practical advancements in disaster management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and K.K.; methodology, Y.K., K.K. and J.H.; software, Y.K. and K.K.; validation, Y.K., K.K. and J.H.; formal analysis, Y.K., K.K. and J.H.; data curation, Y.K. and K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, J.H.; visualization, Y.K. and K.K.; supervision, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bowman, D.M.; Kolden, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Johnston, F.H.; van der Werf, G.R.; Flannigan, M. Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Kooyman, R.M.; Taylor, C.; Ward, M.; Watson, J.E. Recent Australian wildfires made worse by logging and associated forest management. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.D.; Broader, J.C.; Shaheen, S.A. Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019; Technical Report; UC Institute of Transportation Studies: California, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tymstra, C.; Stocks, B.J.; Cai, X.; Flannigan, M.D. Wildfire management in Canada: Review, challenges and opportunities. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 5, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synolakis, C.E.; Karagiannis, G.M. Wildfire risk management in the era of climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Nexus 2024, 3, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlqvist, J.; Ronchi, E.; Gwynne, S.M.; Kinateder, M.; Rein, G.; Mitchell, H.; Bénichou, N.; Ma, C.; Kimball, A.; Kuligowski, E. The simulation of wildland-urban interface fire evacuation: The WUI-NITY platform. Saf. Sci. 2021, 136, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taccaliti, F.; Marzano, R.; Bell, T.L.; Lingua, E. Wildland–urban interface: Definition and physical fire risk mitigation measures, a systematic review. Fire 2023, 6, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Jang, E.; Im, J.; Kwon, C.; Kim, S. Developing a new hourly forest fire risk index based on catboost in South Korea. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Nam, K.; Lim, H. Is critical infrastructure safe from wildfires? A case study of wildland-industrial and-urban interface areas in South Korea. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 95, 103849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Suh, J.; Baek, M. Climatic and Forest Drivers of Wildfires in South Korea (1980–2024): Trends, Predictions, and the Role of the Wildland–Urban Interface. Forests 2025, 16, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguettaya, A.; Zarzour, H.; Taberkit, A.M.; Kechida, A. A review on early wildfire detection from unmanned aerial vehicles using deep learning-based computer vision algorithms. Signal Process. 2022, 190, 108309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, R.; Akhloufi, M.A. Deep learning approaches for wildland fires using satellite remote sensing data: Detection, mapping, and prediction. Fire 2023, 6, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Perrusquía, A.; Al-Rubaye, S.; Guo, W. Wildfire and smoke early detection for drone applications: A light-weight deep learning approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 136, 108977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amideo, A.E.; Scaparra, M.P.; Kotiadis, K. Optimising shelter location and evacuation routing operations: The critical issues. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, S.N.; Wong, S.D. Systematic review and research gaps on wildfire evacuations: Infrastructure, transportation modes, networks, and planning. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2024, 47, 1364–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Assembly Research Service. National Response Strategies for Large-Scale Wildfires: Lessons from the 2025 Yeongnam Wildfire Crisis; Technical Report; National Assembly Research Service: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. Why Have the Wildfires in S Korea Been So Devastating? 2025. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cp8l60l8ppzo (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Demange, M.; Gabrel, V.; Haddad, M.; Murat, C. A robust p-Center problem under pressure to locate shelters in wildfire context. EURO J. Comput. Optim. 2020, 8, 103–139. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, I.; Ortuño, M.T.; Tirado, G. A goal programming model for early evacuation of vulnerable people and relief distribution during a wildfire. Saf. Sci. 2023, 164, 106117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohi, S.J.; Kim, A.M. Identifying a network of wildfire evacuation host communities. Saf. Sci. 2024, 179, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatseresht, M.; Mansourian, A.; Taleai, M. Evacuation planning using multiobjective evolutionary optimization approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 198, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.R.; Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C. Evacuation from natural disasters: A systematic review of the literature. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 812–839. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.K.; Lindell, M.K.; Prater, C.S. Who leaves and who stays? A review and statistical meta-analysis of hurricane evacuation studies. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 991–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimellaro, G.P.; Ozzello, F.; Vallero, A.; Mahin, S.; Shao, B. Simulating earthquake evacuation using human behavior models. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2017, 46, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H., Jr.; Lim, M.B.; Piantanakulchai, M. A review of recent studies on flood evacuation planning. J. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2013, 10, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, P.J.; Carroll, M.S.; Kumagai, Y. Evacuation behavior during wildfires: Results of three case studies. West. J. Appl. For. 2006, 21, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, T.; Marom, I.; Grimberg, E.; Bekhor, S. Analysis of evacuation behavior in a wildfire event. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahlawi, R.Y.; Akbari, V.; Lawson, G. A systematic review of methodologies for human behavior modelling and routing optimization in large-scale evacuation planning. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 110, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgawad, H.; Abdulhai, B. Emergency evacuation planning as a network design problem: A critical review. Transp. Lett. 2009, 1, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, V. Optimization models for large scale network evacuation planning and management: A literature review. Surv. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2016, 21, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloglazov, A.; Almashor, M.; Abebe, E.; Richter, J.; Steer, K.C.B. Simulation of wildfire evacuation with dynamic factors and model composition. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2016, 60, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, S.; Wilson, R.; Konar, A. Should I stay or should I go now? Or should I wait and see? Influences on wildfire evacuation decisions. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 1390–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, N.; Gladwin, H. Evacuation decision making and behavioral responses: Individual and household. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2007, 8, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuligowski, E. Evacuation decision-making and behavior in wildfires: Past research, current challenges and a future research agenda. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 120, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guanquan, C.; Jinhua, S. The effect of pre-movement time and occupant density on evacuation time. J. Fire Sci. 2006, 24, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.S.; Liao, C.H. Planning emergency shelter locations based on evacuation behavior. Nat. Hazards 2015, 76, 1551–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, A.M.; Ukkusuri, S.V.; Gladwin, H. The role of social networks and information sources on hurricane evacuation decision making. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2017, 18, 04017005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.S.; Grace, R. Influence of social networks and opportunities for social support on evacuation destination decision-making. Saf. Sci. 2022, 147, 105564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Jin, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Intelligent Evacuation route planning algorithm based on maximum flow. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, P.; Chen, J. Optimal emergency evacuation route planning model based on fire prediction data. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, R.; Murray-Tuite, P.; Edara, P.; Triantis, K. Modeling the impact of traffic management strategies on households’ stated evacuation decisions. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2022, 15, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idoudi, H.; Ameli, M.; Van Phu, C.N.; Zargayouna, M.; Rachedi, A. An agent-based dynamic framework for population evacuation management. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 88606–88620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idoudi, H.; Li, W.; Ameli, M.; González, M.C.; Zargayouna, M. Population evacuation in motion: Harnessing disaster evolution for effective dynamic emergency response. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 10, 4804–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonmee, C.; Arimura, M.; Asada, T. Facility location optimization model for emergency humanitarian logistics. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 24, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, W.; Qin, L.; Zhao, X. Site selection models in natural disaster shelters: A review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, A.; Pelegrín, M. p-Median problems. In Location Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kongsomsaksakul, S.; Yang, C.; Chen, A. Shelter location-allocation model for flood evacuation planning. J. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2005, 6, 4237–4252. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Huang, R.; Hu, Q.; Wang, J.; Gao, F. Planning emergency shelters for urban disaster resilience: An integrated location-allocation modeling approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.H.; Pan, Y.J.; Chen, H. Shelter location–allocation problem for disaster evacuation planning: A simulation optimization approach. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 171, 106784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, A.; Smith, J.M. Multi-objective evacuation routing in transportation networks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 198, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Inoue, M. An evacuation route planning for safety route guidance system after natural disaster using multi-objective genetic algorithm. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 96, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, V.; Bandeira, R.; Bandeira, A. A method for evacuation route planning in disaster situations. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 54, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T. A network flow approach to a city emergency evacuation planning. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1996, 27, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamacher, H.W.; Heller, S.; Rupp, B. Flow location (FlowLoc) problems: Dynamic network flows and location models for evacuation planning. Ann. Oper. Res. 2013, 207, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Gao, Z.; Li, S.; Zhou, X. Evacuation planning for disaster responses: A stochastic programming framework. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 69, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, V.; Yaman, H. A stochastic programming approach for shelter location and evacuation planning. RAIRO Oper. Res. Rech. Opér. 2018, 52, 779–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. A two-stage stochastic programming framework for evacuation planning in disaster responses. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 145, 106458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereiduni, M.; Shahanaghi, K. A robust optimization model for distribution and evacuation in the disaster response phase. J. Ind. Eng. Int. 2017, 13, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Mandala, S.R.; Chung, B.D. Evacuation transportation planning under uncertainty: A robust optimization approach. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2009, 9, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrahmani, E.; Delavar, M.R.; Pahlavani, P.; Mostafavi, M.A. Dynamic evacuation routing plan after an earthquake. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2015, 16, 04015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.E.; Kosba, E.; Mahar, K.; Mesbah, S. A framework for emergency-evacuation planning using GIS and DSS. In Information Fusion and Intelligent Geographic Information Systems (IF&IGIS’17) New Frontiers in Information Fusion and Intelligent GIS: From Maritime to Land-Based Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Shahabi, K.; Wilson, J.P. Scalable evacuation routing in a dynamic environment. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 67, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]