Abstract

As the global context for sustainable actions increases continuously, understanding the psychological and demographic factors that influence green purchase intention (GPI) is vital for promoting sustainable consumer behavior. This study addresses the gap in the literature regarding how age affects sustainability consciousness (SC) and then influences GPI. The study employs a multidimensional construct measuring perception of people’s attitudes, knowledge, and behavior with respect to the economic, social, and environmental domain. The purpose of the study was to examine the direct and indirect effects of age on GPI through the mediators of sustainability knowledge (SKNOW), sustainability attitude (SATT), and sustainable behavior (SBEH). A serial mediation model (Model 6) developed by Hayes was applied using the PROCESS macro in SPSS version 26. Data were collected from a general adult population with purchasing power who independently make purchasing decisions in their household from Varazdin County, located in the northern part of the Republic of Croatia, representing different age groups and analyzed to test the hypothesis. In total 323 respondents participated. Results revealed that age had no direct effect on GPI, but significant indirect effects were found through the serial mediation. Specifically, the older groups showed stronger sustainability behavior, which significantly predicted GPI. The findings support the multidimensional structure of SC and highlight the importance of educational and behavioral strategies in promoting sustainable consumption, particularly tailored to specific age groups. This research contributes to sustainability and consumer behavior literature by demonstrating how age influences green purchase intention through serial mediation pathways.

1. Introduction

Recent research by Deloitte reveals that consumers are increasingly adopting sustainable habits. Data show [1] that the shift towards more sustainable consumer behavior is limited by accessibility and affordability. Also, the business sector has entered a serious new phase focusing on sustainable business in order to address the challenges of environmental pollution, climate change, and social issues, which is seen in the increase in reporting about their sustainability. In this context, the concept of green purchase intention plays a significant part in sustainability behavior since it refers to a person’s likelihood to choose environmentally friendly products [2]. In terms of generations, younger and older individuals may be concerned about sustainability, but their behaviors often differ due to established habits or distinct life experiences. Understanding how age influences sustainability consciousness helps in tailoring strategies to promote sustainable behaviors across all age groups.

Despite the growing interest in the area of sustainability research, a research gap lies in the understanding of how sustainability consciousness translates into green purchase intention from the perspective of a person’s age. Evidence from the literature shows diverse results on the impact of age on sustainability [3]. There are studies that examine consumer demographics (age, gender, educational level, etc.) impacting green purchase intention. Most of the mediators in this relation that have been analyzed are through green purchase attitude [4], environmental awareness and health consciousness [5], or control variables in the study analyzing green marketing strategies [6]. Ref. [7] examined the effect of gender on student sustainability consciousness. Further, Ref. [8] investigated the impact of demographic factors on tourists’ sustainability consciousness and awareness of sustainable tourism on purchasing behavior.

However, there are no studies examining how and why age affects green purchase intention through the serial mediation effect. The limited number of studies directly examining how and why age affects green purchase intention through sustainability consciousness can be explained by the fact that most previous research on sustainable consumption has tended to treat age as a control variable rather than as an independent variable worthy of deeper theoretical exploration. Also, the mechanisms through which age influences sustainability and behavior are underexplored or have been focused on one mediator. Understanding how age influences consumer attitudes and decision making regarding sustainability is crucial for managers who create strategies for different market segments, which may include different consumer preferences due to age differences. Therefore, the paper examines how age influences a person’s awareness of sustainability issues. It also explores whether greater knowledge about sustainability leads to a positive attitude toward green products, potentially making them more favorable toward green choices. A positive attitude toward sustainability leads to more environmental behaviors, like green practice support. Finally, these behaviors strengthen the intention to purchase environmentally friendly products or services.

The goal of the research is to analyze the effect of age on green purchase intention by using the serial mediation model to understand the process through which an independent variable (age) influences a dependent variable (green purchase intention) through mediating variables that work in a sequence.

2. Sustainability Consciousness and the Role of Age

In recent years, sustainability gained significant attention at the political, legal, and economic levels of EU countries and beyond. To live and act sustainably, it is essential for everyone to develop a consciousness around sustainability. Consequently, influencing people’s participation and their impact on sustainability is crucial for achieving the sustainable development of society as a whole. Creating awareness about sustainability is vital, and it is necessary to educate all stakeholders on the very concept of sustainable development. The concept of sustainability consciousness (SC) examines the impact of people’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on sustainable development. This concept has been tested and developed by [9]. The primary goal of sustainability consciousness (SC) is to promote the sustainable growth and development of the entire society by enhancing awareness of the global sustainability objectives through changes in people’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, thereby enabling individuals to act and live sustainably. UNESCO defined and established the term education for sustainable development (ESD), stating that “ESD empowers people with the knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, and behaviors to live in a way that is good for the environment, economy, and society. It encourages people to make smart, responsible choices that help create a better future for everyone” [10]. ESD is an SDG, i.e., an indicator which “measures how well global citizenship education and ESD are integrated into national education policies, curricula, teacher education, and student assessments” [11]. Thus, sustainability conscientiousness is closely related to ESD. Recent research increasingly focuses on understanding the concept of sustainability consciousness (SC) and how it can be achieved. This research also examines the impact of sustainability attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors on the pursuit of sustainable development within society.

By examining the concept of sustainability awareness, authors [12] explored the ecological, economic, and social dimensions of sustainable development. They highlighted sustainability consciousness as a combination of knowledge, attitude, and behavior concerning sustainability. Furthermore, a study [13] demonstrates that sustainability knowledge and attitudes significantly influence sustainability-related behaviors, with sustainability attitudes having a more pronounced impact.

A survey conducted on tourists proves that awareness of sustainability plays a key role in shaping their behavior, particularly regarding the desire and need to buy green products. This, in turn, influences their ecological attitudes and behaviors [14].

The sustainability consciousness (SC) construct was developed and operationalized by [9] and the definition of the SC construct relates to the situation where people are aware of the sustainability phenomena. Authors created a multidimensional construct, i.e., questionnaire, that gathers information about people’s attitudes, knowledge, and behavior in the economic, social, and environmental area [9].

The role of age in sustainability consciousness is important as different age groups may exhibit different sustainable behaviors and decisions. Research indicates a positive correlation between age groups and a green attitude, specifically in terms of sustainability consciousness related to green purchasing intentions. For example, Generation Z is often perceived as more sustainability conscious due to greater exposure to social media [15] even in the context of developing countries [16]. This trend is particularly evident in the food industry, where some categories of Generation Z buyers (sustainable activists and believers) prefer healthy product aspects [17]. Additionally, Generation Z travelers who have the tendency to use low-carbon transportation have an affinity to stay in low-carbon hotels [18]. Studies demonstrate that, as individuals age, their increasing levels of education and maturity contribute significantly to a raised awareness of sustainability, which is particularly relevant to sustainable tourism [8]. The study on gender differences regarding the sustainability consciousness between boys and girls reveals a gap in students’ sustainability consciousness that increases throughout the age span [7]. Research by [19] proves that there are age differences in terms of preserving natural resources and raw materials as well as endangering the environment, with older individuals displaying more inclination to the aforementioned issues. Research by [20] describes that Millennials are the most sensitive generation when it comes to sustainability. The research by [21] proves that individuals, in this case Gen Z and Millennials, who have an attitude towards sustainability and environmental issues buy products and brands that are in line with their values of responsible production. Ref. [22] also confirms that Millennials prefer and seek sustainable products. The same was also confirmed by [4] where the 18–30 age group has a stronger intention for green purchases compared to other age groups. Ref. [23] also proves that millennials in India show a high concern for the environment and express a willingness and positive attitude towards buying green products and services. Millennials show that the experience of green products and their ecological labeling are key factors regarding green purchase intentions [24]. Research conducted on those aged 18–30 years regarding the effect of ecological impact and ecological knowledge on green purchase intention confirms that ecological impact and knowledge are key in determining the green involvement of young consumers [25]. Researchers [26] examined the attitudes and trust levels of Generation X and Generation Y concerning green purchase intentions. Their study revealed that the intention to purchase eco-friendly products significantly influences the environmentally conscious buying behavior of both generations. However, environmental knowledge specifically impacts Generation Y’s intention to buy green products. Authors [27] proved the positive effects of Generation Z’s attitude towards green purchasing, as well as knowledge about green activities among Generation Z. Additionally, younger and more educated individuals, particularly men, tend to support green purchases. In contrast, older and wealthier individuals are more likely to buy green products [28]. An interesting study conducted among young consumers [29] confirmed the influence of social media on consumers’ buying intention for ecological products, while knowledge about ecological products did not affect or mediate intention to buy green. It appears that most of the research investigating the role of age in sustainability consciousness regarding green consumption refers to the Millennial age group.

Cross-sectional studies across various cultural contexts have highlighted the importance of sustainability consciousness and its relationship with pro-environmental behaviors. In Portugal, a study validating the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ) on 630 participants aged 17 to 83 showed strong reliability and clear links between sustainability knowledge, attitudes, and real-world sustainable practices, indicating its usefulness for education, policy development, and research initiatives [30]. In the Netherlands, research among 388 older adults living in the community in The Hague examined beliefs, behaviors, and financial aspects related to sustainability, revealing generally positive scores across districts and identifying six distinct typologies of older adults, each differing in sustainability beliefs, behaviors, and financial capacity [31]. In Turkey, a study of 440 sports science students aged 18–26 found that demographic variables such as age, gender, and academic achievement significantly influenced sustainability consciousness and environmental behaviors, with higher sustainability knowledge consistently predicting pro-environmental engagement [32]. In Egypt, research among nursing students from three universities showed that more than half were unfamiliar with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and relied mainly on social media for information, while older students, those from rural areas, and those with greater financial stability or familiarity with the SDGs demonstrated higher sustainability awareness [33].

In the context of Croatian territory, the findings indicate that rural Croatians demonstrate moderate engagement in pro-environmental behavior. Resource conscious behaviors, including energy and waste conservation, frugality, and self-sufficiency, are more prevalent than eco-active behaviors that involve public participation and green consumerism. Environmental concern, biocentric attitudes, subjective well-being, and age emerged as the strongest predictors of both types of pro-environmental behavior. This signifies that ecological values, practical considerations, and cultural–economic motivations collectively shape environmental engagement in rural communities [34]. Further, we found in the study of [35] that that perceptions of whether environmental protection is sufficiently prioritized in Croatia did not significantly differ across education levels. However, attitudes toward waste management varied based on educational attainment, with individuals holding higher degrees exhibiting slightly more critical views. Notable differences were observed between high school graduates, university graduates, and those with postgraduate education, while no clear distinctions were seen between high school and university graduates. Overall, the findings suggest that educational background influences perspectives on environmental preservation and waste management. The sample predominantly consisted of females, with the largest group aged 18 to 26 years. Another study from [36] investigated gender differences in pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in Croatia using an online survey of 263 adults. Results showed that women displayed higher environmental concern, stronger support for recycling, and greater awareness of health implications related to ecological issues. The findings highlight the influence of gender on environmental consciousness and underscore the importance of considering gender in sustainability policies and interventions.

In order to validate the model, following a literature review, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1.

Age is positively related to green purchase intention.

H2.

The relationship between age and green purchase intention is mediated by sustainability knowledge.

H3.

The relationship between age and green purchase intention is mediated by sustainability attitude.

H4.

The relationship between age and green purchase intention is mediated by sustainability behaviors.

Green Purchase Intention

As sustainability becomes increasingly important in both business and everyday life, consumers are becoming more aware of the consequences of rapid societal and economic development, particularly its negative effects. From environmental pollution to the ever-increasing destruction of nature and the impact on human health, consumers are starting to act more responsibly and green regarding their consumption. Being conscious and responsible in green purchasing reflects an individual’s willingness to engage in environmentally friendly behavior by preferring green products over traditional ones. Ecological, i.e., green, products have a less harmful effect on the environment but also on human health, so more and more consumers are turning to green purchase. The study [37] showed that theory of planned behavior (TPB) and theory of reasoned action (TRA) have been confirmed as factors that have a positive and significant impact on the purchase intention of green products. This is closely connected to the sustainability consciousness (SC) framework where people’s attitudes, knowledge, and behavior as interrelated components of an individual’s sustainability orientation, regarding the economic, social, and environmental area, also have an impact on green purchase intention. This structure aligns closely with both TPB and TRA which conceptualize attitudes as key predictors of behavioral intentions and subsequent actions. In SC, sustainability knowledge can be understood as an antecedent shaping cognitive evaluation, similar to the role of beliefs in TPB and TRA. The attitudes dimension of the SC framework corresponds directly to behavioral attitudes in TPB and TRA, influencing the likelihood of forming pro-sustainable intentions. The behavior scale in SC reflects the observable outcome predicted by these theories, emphasizing that sustainable consciousness should translate into real action. Although this SC framework does not explicitly include subjective norms or perceived behavioral control from theories, the psychological mechanisms it measures are compatible with those constructs.

According to [2], consumers’ individual characteristics, cognitive factors, and social factors are the main factors influencing consumers’ green purchase intention. Research [38] shows that environmental consciousness, green promotion, and social influence are significant indicators of green purchase intention. Research by [39] examines the factors that motivate consumers to make green purchases, and with the help of factor analysis, they determined that the following are motivational factors: (1) environmental concern, perceived consumer effectiveness, consumer knowledge; (2) laws and regulation; and (3) promotional tools. The influence of consumer attitudes on green purchase intention and behavior has been supported by [40], while Ref. [41] found no significant impact of consumer attitudes on green purchase intention. Ref. [42] demonstrated that age and other demographic factors (such as gender, level of education, level of income, and presence of children in the household) are related to green purchase intention. Likewise, it was confirmed by [43] that age had a significant impact on the purchase intention of eco-friendly products. Ref. [4] also confirmed that age has a significant influence on green purchase attitudes, while Ref. [44] shows that younger consumers are more likely to purchase green products.

Based on the literature analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5.

The relationship between age and green purchase intention is serially mediated by sustainability knowledge, attitude, and behaviors.

3. Methodology

Research Design

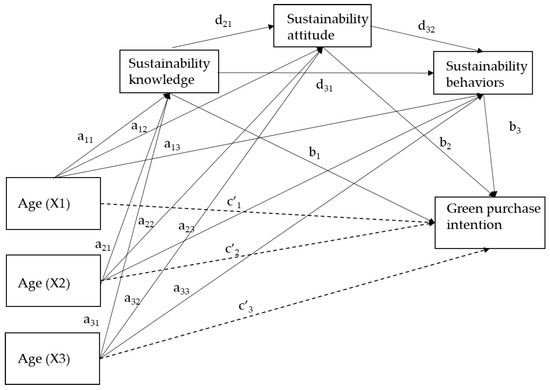

The theoretical model is constructed as a causal chain; therefore, a serial mediation model was the appropriate model to examine the set relations. The PROCESS macro was used, Model 6, to analyze serial mediation effects [45]. The model represents many distinct effects between age and green purchase intention (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model showing the causal relations between age and sustainability consciousness construct on green purchase intention.

The research model suggests that age is related to green purchase intention first through a sequential model involving three mediators; mediator one (M1), representing sustainability knowledge (SKNOW), which influences mediator two (M2), sustainability attitude (SATT), which in turn affects mediator three (M3), sustainability behaviors (SBEH) predicting green purchase intention (GPI). To test the significance of the indirect effects, a bootstrap sample (N = 5000) was used to calculate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. A mediation path was considered significant if the 95% bootstrap confidence interval (BootLLCI–BootULCI) did not include zero. In contrast, when zero lies within the confidence interval, the indirect effect is not significant, meaning that the mediation path is unsupported [45].

For testing the serial mediation model, the independent variable X (AGE) is treated as an ordinal independent variable with four age groups. The program itself uses indicator coding (dummy) where one group serves as reference group [45]. In this analysis, the reference group (X0) represents respondents aged 18–26 years, while the other groups are coded as X1 (27–35 years), X2 (36–44 years), and X3 (45 years and above). This coding allows comparison of each age category’s effect on the mediators and the dependent variable relative to the youngest group. The mediating variables SKNOW (M1), SATT (M2), and SBEH (M3) were measured using the Sustainability Consciousness Scale developed by [9]. Each construct was measured with relevant items on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes toward sustainable knowledge, attitude, and behaviors. The dependent variable (Y), green purchase intention (GPI), was measured using four items adapted from [46], also on a five-point Likert scale, where higher scores indicate stronger intention to purchase environmentally friendly products. To prepare the variable for the serial mediation analysis, the composite SKNOW, SATT, SBEH and GPI score were mean centered prior to analysis. Mean centering was applied to reduce potential multicollinearity among mediating variables and to facilitate more meaningful interpretation of indirect effects within the presented framework [46,47].

A survey on the general population was conducted in Croatia between June and September 2023. It includes the general adult population from Varazdin County, located in the northern part of the Republic of Croatia, with purchasing power who independently make purchasing decisions in their household. Croatia has 21 counties, including the City of Zagreb. The questionnaire was developed and distributed randomly on a social platform through a public Facebook group with approximately 1400 members focused on local community matters with a request to answer the voluntary, anonymous survey about their perception of sustainability and green purchase intention. Finally, 323 responses were collected. The survey consisted of demographic questions (sex, age, education, and income level) and 27 items measuring the sustainability consciousness dimensions, along with 4 items assessing green purchase intention which can be found in Appendix A.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Participants

The sample consists of 323 participants who have completed the survey (Table 1). Among 323 respondents, 65% are female participants and 35% are male participants. Most of the participants (63%) are in the age group aged 18 to 26 years. Additionally, 23% are between 27 and 35 years old, while 6% are between 36 and 44 years old. Eight percent of respondents are older than 45. The distribution shows greater participation of younger individuals.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

Half of the participants have finished high school (53%), 28% undergraduate study, 14% graduate study, 3% postgraduate study, and only 2% have only completed elementary school. In terms of income, 42% have a monthly payment under EUR 750, 34% between EUR 751 and 1200, 17% between EUR 1201 and 2150, 2% between EUR 2151 and 2600, and 5% receive more than EUR 2600 per month.

Further, reliability of the scale and data validity were checked. Reliability of the scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha for the SKNOW scale (nine items) shows a good scale (α = 0.815), the SBEH construct with nine items has a good reliability (α = 0.790), as does GPI (α = 0.884), while SATT (α = 0.674) has a lower reliability, which is slightly below the acceptable threshold of 0.70. Examination of the “Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted” statistics indicated that removing one item improved reliability to 0.797, suggesting that this one item reduced the internal consistency of the construct. Therefore, the problematic item was excluded, and the final eight-item scale was retained for further analyses. The revised scale of SATT demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.797).

Further, validity of the questionnaire is presented in Table 2. Validity was preliminarily assessed using Pearson correlation analysis.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

All variables were positively and significantly correlated (p < 0.01) and consistent with theoretical expectations. SKNOW was strongly associated with SATT (r = 0.581) and moderately related to SBEH (r = 0.331) and GPI (r = 0.296). These results indicate that the scales are internally consistent and suitable for further analysis.

Results in Table 3 indicate that respondents have high sustainability knowledge (SKNOW) as well as attitudes toward sustainability (SATT). Sustainability behavior (SBEH) is lower, indicating that respondents are aware of sustainability but may not behave sustainably. GPI has the highest standard deviation among the analyzed variables, which probably indicates that not all respondents have the intention to buy greener equally.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for measured constructs SKNOW, SATT, SBEH, and GPI.

4.2. The Results of the Serial Mediation Analysis

To test the set hypothesis, we performed a regression analysis, and the results are presented in Table 4. Hypothesis H1 tested the total effect of age on green purchase intention (c’). Since there are four age groups, three age groups (X1, X2, X3) are interpreted with reference to one reference group (X0, age 18–26), therefore, we have three total effects (c’1, c’2, and c’3). After performing regression analysis, this relation was found to be non-significant for all three groups: X1 (b = −0.007, SE = 0.088, p = 0.941), X2 (b = −0.013, SE = 0.148, p = 0.929), and X3 (b = −0.177, SE = 0.140, p = 0.205) in reference to the younger group. Thus, H1 is not supported, and age does not directly influence green purchase intention.

Table 4.

Regression model of the effect of different age groups on green purchase intention among the general population.

Further, we analyzed the relative indirect effect of age affecting sustainability knowledge, which then influences green purchase intention. The effect was not significant for all groups, since zero lies within the confidence interval, X1 (b = 0.006, BootLLCI = −0.012, BootULCI = 0.035), X2 (b = 0.014, BootLLCI = −0.023, BootULCI = 0.060), X3 (b = 0.026, BootLLCI = −0.040, BootULCI = 0.098). H2 is not supported since sustainability knowledge does not mediate the path between age and green purchase intention.

Hypothesis H3 states that sustainability attitude mediates the relationship between age and green purchase intention. The significance test of this indirect effect shows that age did not predict sustainability attitude for X1 (b = 0.042, BootLLCI = −0.024, BootULCI = 0.062), X2 (b = −0.018, BootLLCI = −0.085, BootULCI = 0.042), and X3 (b = 0.011, BootLLCI = −0.052, BootULCI = 0.083). Therefore, H3 is not supported.

H4 states that the relationship between age and green purchase intention is mediated by sustainability behaviors. The significance test of relative indirect effect shows that age predicts sustainability behaviors and that sustainability behaviors do predict green purchase intention in two older groups, X2 (b = 0.130, BootLLCI = 0.018, BootULCI = 0.250) and X3 (b = 0.267, BootLLCI = 0.158, BootULCI = 0.400), as the confidence interval excludes zero, supporting H4.

Likewise, the indirect effect of age on green purchase intention through the mediation of sustainability knowledge, sustainability attitude, and sustainability behaviors was significant for X2 (b = 0.024, BootLLCI = 0.001, BootULCI = 0.055) and X3 (b = 0.045, BootLLCI = 0.019, BootULCI = 0.080). Therefore, the results of the analysis show that age matters and is positively associated with green purchase intention through all three mediators, differing by age group. Thus, H5 is supported. Findings revealed that 33% of the variance in green purchase intention is explained by all three mediators and age.

5. Discussion

This research examines the relationship between age, sustainability knowledge, sustainability attitude, and sustainability behaviors, in relation to green purchase intention among the adult population residing in Varazdin County in Croatia, using serial multiple mediation analysis. The analysis results in Table 5 indicate that, in comparison with the reference group (age 18–26), the relative total effect (c) of age on GPI was not significant for all groups since zero falls between the lower and upper CIs. This was also found for the relative direct effect of age on GPI (c’).

Table 5.

Total and direct relative effects.

Table 6 shows key bootstrap relative results for indirect effects. Those results indicate that, when using the reference group (age 18–26), age influences GPI only through mediator SBEH, and this mediation is significant for older age groups X2 (path a23b3) and X3 (path a33b3) since lower and upper CIs are above zero. Further, relative indirect effects through SKNOW for all age groups (paths: a11b1, a21b1, a31b1) are not significant as well as for the mediator SATT (paths: a12b2, a22b2, a32b2). A detailed table of regression coefficients and the bootstrap indirect effect estimates (95% CI) for every age group path to each mediator can be found in Appendix B.

Table 6.

Multiple mediation indirect effects between all age groups and green purchase intention (main bootstrap effects).

Based on Table 6 and a bootstrap CI value (values that do not include zero are significant), a significant indirect path with one mediator is AGE -> SBEH -> GPI for older groups X2 (effect = 0.130, BootLLCI = 0.018, BootULCI = 0.250) and X3 (effect = 0.267, BootLLCI = 0.156, BootULCI = 0.400). Other paths that include one mediator are not significant (AGE -> SKNOW -> GPI and AGE -> SATT -> GPI). Further, analysis shows that the path AGE -> SKNOW -> SATT -> GPI including two mediators is significant for older groups X2 (effect = 0.036, BootLLCI = 0.001, BootULCI = 0.087) and X3 (effect = 0.067, BootLLCI = 0.023, BootULCI = 0.122).

Finally, serial mediation including all three mediators (AGE -> SKNOW -> SATT -> SBEH -> GPI) is significant for older groups X2 and X3. Older group X2 impacts GPI through SKNOW, then passing through SATT and then SBEH (effect = 0.024, BootLLCI = 0.001, BootULCI = 0.055). This path was found to also be significant for the older group X3 (effect = 0.045, BootLLCI = 0.026, BootULCI = 0.080).

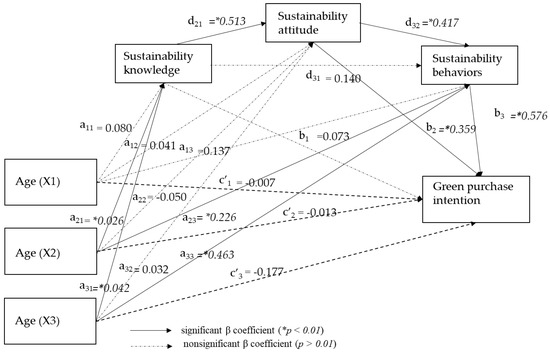

All direct and indirect, as well as significant and non-significant, effects are presented in Figure 2 as paths with significant and non-significant β coefficients.

Figure 2.

Serial mediation analysis results with three mediators (Model 6).

Given that the direct effect of age on GPI was not significant and the indirect effects were significant, the results suggest full mediation.

The findings indicate that age influences green purchase intention primarily through indirect pathways involving sustainability knowledge, attitude, and behavior. The most interesting finding that comes up is that older individuals (age groups X2 and X3) are likely to have more sustainability knowledge and a more positive attitude towards sustainability, which in turn promotes sustainable behaviors and increases green purchase intention. Behavior has the most effect on GPI, while knowledge and attitudes contribute upstream. The mediation model does not show that knowledge or attitudes independently increase green purchase intention unless they first produce sustainable behavior, which is the final mechanism that predicts GPI.

Results of the study indicate higher ecological awareness among older respondents regarding reducing water consumption, preserving biodiversity, and natural disaster preparedness. Likewise, they show higher social and economic awareness regarding peaceful conflict resolution, human rights, and education and recognize the importance of corporate responsibility, fairness, and reducing poverty. Further, older individuals indicate stronger and more consistent sustainability attitudes, especially regarding supporting stricter laws and regulations as well as the importance of taking measures regarding climate change problems. They support sustainable education, concern about protecting future well-being, and reducing waste. Finally, older respondents show higher rates of environmental, social, and economic aspects of sustainable behavior.

The stronger indirect effect of age on green purchase intention through sustainability knowledge, attitude, and behavior may reflect the accumulation of life experience, financial stability, and a greater sense of responsibility toward future generations typically associated with older individuals. As people age, they may become more aware of long-term environmental consequences and adopt values that emphasize preservation and responsible consumption. This aligns with theories of value change suggesting that older adults tend to prioritize altruistic values and care for the environment more strongly than younger age groups such as in the research of [48].

Younger participants, despite being frequently exposed to sustainability messages and education, may encounter what psychologists refer to as the attitude–behavior gap [49]. This means that, while they care about environmental issues and prefer green products, this concern does not always lead to actual purchasing behavior. This gap may result from limited purchasing power, reliance on family decision making, or the influence of convenience and price sensitivity. Therefore, the current findings suggest that sustainability communication strategies for younger generations should focus not only on raising awareness but also on strengthening behavioral intentions through emotional engagement, social media influence, and incentives for sustainable choices.

These interpretations reinforce the role of sustainability consciousness as a process that develops and strengthens with age, integrating cognitive (knowledge), affective (attitude), and behavioral (practice) dimensions that ultimately shape green purchase decisions.

Our results align with the findings of [8,19], who found older groups to be more concerned about environmental impact in sustainable tourism and preservation of resources, indicating that life experience contributes to higher sustainability consciousness. Also, the findings of [28] show that older and more wealthy people buy green products. However, many previous studies indicate younger age groups (Millennials and Generation Z) are prime movers of sustainable consumption ([4,15,18,20,21,27]). Interestingly, results of our study diverge from these earlier studies that identified younger consumers as the main drivers of sustainable purchasing [44]. This difference may arise from contextual factors such as cultural norms, regional economic conditions, or differing levels of sustainability education in Croatia. Moreover, while younger respondents may express higher concern for environmental issues, their consumption choices might still be constrained by affordability or skepticism toward green marketing claims. These contextual contrasts emphasize that age alone cannot fully explain green purchasing behavior but most probably depend on socio-economic and cultural conditions that shape sustainability consciousness.

These results are consistent with previous research conducted in Croatia, which shows that age, environmental concern, and biocentric attitudes are significant predictors of pro-environmental behavior, particularly in rural contexts [34]. This highlights the role of life experience and accumulated knowledge in shaping sustainable consumption. Compared to other studies in Croatia, our findings complement evidence regarding the influence of demographic factors such as education and gender. For example, educational attainment impacts attitudes toward waste management [35], while women tend to exhibit higher levels of environmental concern and engagement [36]. Together, these studies emphasize that environmental consciousness and behavior in Croatia are influenced by a combination of age, education, gender, and socio-cultural contexts.

The present findings shed light that younger age groups may have knowledge and a positive attitude toward sustainability, but that does not have to lead to sustainable purchase behavior unless supported by behavioral intentions. For example, Refs. [17,18] found that Generation Z prefers green solutions in the food and tourism context, suggesting variability in particular industry domains.

This mediation suggests that, while age may directly reduce green purchase intention, the indirect positive effects via the mediators are significant, resulting in an overall positive influence, which confirms that the applied SC framework highlights the fact that actions of an individual regarding sustainability are driven by internal knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. These results highlight the importance of targeting sustainability knowledge and attitudes to foster sustainable behaviors and enhance green purchase intentions across different age groups. For younger age groups, this can be performed with different reinforcement strategies like green promotions [24] or through social media [15].

Overall, the findings support the sustainability consciousness framework by showing that demographic factors such as age operate through cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral mechanisms to shape green purchase intentions. This reinforces the importance of sustainability education and targeted communication strategies that consider differences depending on a distinct period in a consumer’s life in promoting sustainable consumption.

6. Conclusions

This paper explored the impact of age on green purchase intention (GPI) through the mediating roles of sustainability knowledge (SKNOW), sustainability attitude (SATT), and sustainable behavior (SBEH) within the sustainability consciousness (SC) framework. Although total and direct effects of age on GPI were not found to be significant, the results demonstrated that age significantly affects it indirectly through a serial mediation model, underscoring the critical role of sustainability consciousness as a mediating construct that links demographic characteristics to sustainable behaviors.

The results showed that older individuals (from 36 to 44 and those above 45) demonstrate a stronger effect through SKNOW, SATT, and SBEH, leading to higher GPI, suggesting that life experience may contribute to more sustainable decisions when buying.

Some limitations of the study should be highlighted. The first limitation of the study is that it is a cross-sectional study which is good for measuring prevalence and exploring associations but vulnerable to selection bias. This leads us to the second limitation of the study, which is overrepresentation of younger participants in the sample (63% aged 18–26), while older age groups are underrepresented, especially those aged 36–44 (6%). This introduces potential selection bias and limits the generalizability of the findings to the wider population. Since younger individuals may have different levels of sustainability consciousness, digital literacy, and purchasing power than older consumers, the results might not fully represent the attitudes and behaviors of older age groups but primarily reflect the attitudes of younger individuals. Future research should aim for a more balanced sample across age categories.

Future research may focus on including a broader area of the Republic of Croatia, i.e., more or all counties in the Republic of Croatia. The same thing could be explored in neighboring countries like Slovenia or other EU countries with the goal of making a data comparison. Also, it would be interesting in the future to explore other relationships and investigate additional mediators or moderating factors that may influence these pathways in different specific contexts.

Also, this paper focused on examining sequential directional relationships rather than reciprocal causality among variables. However, future research could employ longitudinal or cross-lagged designs to examine potential bidirectional relationships between sustainability knowledge, attitudes, and behavior over time.

Overall, the study highlights the important role of serial indirect effects in analyzing sustainability; therefore, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how demographic factors interact with psychological and behavioral constructs to influence more environmentally oriented consumption. Sustainable knowledge should be encouraged by educational institutions, organizations, and different kinds of media, especially social media, which is most popular among younger consumers, as sustainable consciousness leads to green purchase intention. This is valuable for governments, policymakers, educators, organizations, and marketers aiming to promote sustainable consumption patterns in different age cohorts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S.; methodology, V.S.; software, V.S.; validation, V.S. and I.M.; formal analysis, V.S.; investigation, I.M.; resources, I.M.; data curation, V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S. and I.M.; writing—review and editing, V.S. and I.M.; visualization, V.S. and I.M.; supervision, V.S.; project administration, I.M.; funding acquisition, V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University North, grant number UNIN-DRUŠ-25-1-1.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| GPI | Green Purchase Intention |

| SC | Sustainability Consciousness |

| SKNOW | Sustainability Knowledge |

| SATT | Sustainability Attitude |

| SBEH | Sustainability Behavior |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| TRA | Theory of Reasoned Action |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Construct questions and sources.

Table A1.

Construct questions and sources.

| 1. Sustainability Consciousness Construct [9] |

|---|

| 1.1. Sustainability knowingness (SKNOW) |

| Likert scale 1 to 5, where 1 is “I do not agree at all” and 5 is “I completely agree”. |

| SAO1: Reducing water consumption is necessary for sustainable development. |

| SAO2: Preserving the variety of living creatures is necessary for sustainable development (preserving biological diversity). |

| SAO3: For sustainable development, people need to be educated in how to protect themselves against natural disasters. |

| SAD1: A culture where conflicts are resolved peacefully through discussion is necessary for sustainable development. |

| SAD2: Respecting human rights is necessary for sustainable development. |

| SAD3: To achieve sustainable development, all the people in the world must have access to good education. |

| SAE1: Sustainable development requires that companies act responsibly towards their employees, customers and suppliers. |

| SAE2: Sustainable development requires a fair distribution of goods and services among people in the world. |

| SAE3: Wiping out poverty in the world is necessary for sustainable development. |

| 1.2. Sustainability attitudes (SATT) |

| Likert scale 1 to 5, where 1 is “I do not agree at all” and 5 is “I completely agree”. |

| SAO1: I think that using more natural resources than we need does not threaten the health and well-being of people in the future. |

| SAO2: I think that we need stricter laws and regulations to protect the environment. |

| SAO3: I think that it is important to take measures against problems which have to do with climate change. |

| SAD1: I think that everyone ought to be given the opportunity to acquire the knowledge, values and skills that are necessary to live sustainably. |

| SAD2: I think that we who are living now should make sure that people in the future enjoy the same quality of life as we do today. |

| SAD3: I think that women and men throughout the world must be given the same opportunities for education and employment. |

| SAE1: I think that companies have a responsibility to reduce the use of packaging and disposable articles. |

| SAE2: I think it is important to reduce poverty. |

| SAE3: I think that companies in rich countries should give employees in poor nations the same conditions as in rich countries. |

| 1.3. Sustainability behavior (SBEH) |

| Likert scale 1 to 5, where 1 is “I do not agree at all” and 5 is “I completely agree”. |

| SBO1: I recycle as much as I can. |

| SBO2: I always separate food waste before putting out the rubbish when I have the chance. |

| SBO3: I have changed my personal lifestyle in order to reduce waste (e.g., throwing away less food or not wasting materials). |

| SBD1: When I use a computer or mobile to chat, to text, to play games and so on, I always treat others as respectfully as I would in real life. |

| SBD2: I support an aid organization or environmental group. |

| SBD3: I show the same respect to men and women, boys and girls. |

| SBE1: I do things which help poor people. |

| SBE2: I often purchase second-hand goods over the internet or in a shop. |

| SBE3: I avoid buying goods from companies with a bad reputation for looking after their employees and the environment. |

| 2. Green Purchase Intention [46] |

| Likert scale 1 to 5, where 1 is “I do not agree at all” and 5 is “I completely agree”. |

| GPI1: I am willing to buy an environmentally friendly product. |

| GPI2: If prices are not different from others, I may purchase environmentally friendly products. |

| GPI3: If qualities are not different from others, I may purchase environmentally friendly products. |

| GPI4: I would consider switching to other products for ecological reasons. |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Regression coefficients and the bootstrap indirect effect estimates (95% CI) for every age contrast.

Table A2.

Regression coefficients and the bootstrap indirect effect estimates (95% CI) for every age contrast.

| Paths from Age (X) to SKNOW (M1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | β | SE | t | p | 95% CI (LLCI, ULCI) |

| Constant | 4.378 | 0.035 | 127.068 | 0.000 | 4.310, 4.446 |

| X0 (18–26 -> X1) | 0.080 | 0.067 | 1.193 | 0.233 | −0.052, 0.212 |

| X2 (X0 -> X2) | 0.026 | 0.035 | −0.040 | 0.098 | −0.028, 0.415 |

| X3 (X0 -> X3) | 0.042 | 0.022 | −0.024 | 0.062 | 0.160, 0.562 |

| Paths from Age (X) to SATT (M2) | |||||

| Constant | 1.984 | 0.192 | 10.341 | 0.000 | 1.607, 2.362 |

| X1 | 0.041 | 0.052 | 0.788 | 0.432 | −0.061, 0.143 |

| X2 | −0.050 | 0.088 | −0.574 | 0.567 | −0.223, 0.122 |

| X3 | 0.032 | 0.081 | 0.394 | 0.694 | −0.127, 0.191 |

| SKNOW (d21) | 0.513 | 0.043 | 11.828 | 0.000 | 0.428, 0.599 |

| Paths from Age (X) to SBEH (M3) | |||||

| Constant | 1.468 | 0.314 | 4.670 | 0.000 | 0.850, 2.087 |

| X1 | 0.137 | 0.0740 | 1.850 | 0.065 | −0.009, 0.282 |

| X2 | 0.226 | 0.124 | 1.817 | 0.070 | −0.019, 0.470 |

| X3 | 0.463 | 0.115 | 4.044 | 0.000 | 0.238, 0.689 |

| SKNOW | 0.140 | 0.074 | 1.901 | 0.058 | −0.005, 0.286 |

| SATT (d32) | 0.417 | 0.080 | 5.249 | 0.000 | 0.261, 0.574 |

| Paths from Age (X) to GPI through (SKNOW, SATT, SBEH) | |||||

| Constant | 0.107 | 0.386 | 0.278 | 0.781 | −0.652, 0.867 |

| X1 | −0.007 | 0.088 | −0.074 | 0.941 | −0.180, 0.167 |

| X2 | −0.013 | 0.148 | −0.089 | 0.929 | −0.305, 0.279 |

| X3 | −0.177 | 0.140 | −1.270 | 0.205 | −0.451, 0.097 |

| SKNOW (b1) | 0.073 | 0.088 | 0.826 | 0.410 | −0.100, 0.246 |

| SATT (b2) | 0.359 | 0.098 | 3.644 | 0.000 | 0.165, 0.552 |

| SBEH (b3) | 0.576 | 0.067 | 8.632 | 0.000 | 0.444, 0.707 |

Source: Authors’ data.

References

- Delloite. The Sustainable Consumer. 2024. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/content/dam/assets-zone2/uk/en/docs/industries/consumer/2024/deloitte-uk-sustainable-consumer-2024.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Zhuang, W.; Xiaoguang, L.; Muhammad, R. On the Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerónimo, H.M.; Henriques, P.L.; de Lacerda, T.C.; da Silva, F.P.; Vieira, P.R. Going green and sustainable: The influence of green HR practices on the organizational rationale for sustainability. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wong, P.P.; Narayanan, E.A. The demographic impact of consumer green purchase intention toward green hotel selection in China. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Wu, Z.; Du, S. Study on the impact of environmental awareness, health consciousness, and individual basic conditions on the consumption intention of green furniture. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Gangwar, V.P.; Dash, G. Green marketing strategies, environmental attitude, and green buying intention: A multi-group analysis in an emerging economy context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The effect of gender on students’ sustainability consciousness: A nationwide Swedish study. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 48, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucgun, G.Ö.; Narci, M.T. The Role of Demographic Factors in Tourists’ Sustainability Consciousness, Sustainable Tourism Awareness and Purchasing Behavior. J. Tour. 2022, 8, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, N.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Berglund, T.; Olsson, D. The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire: The theoretical development and empirical validation of an evaluation instrument for stakeholders working with sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Education for Sustainable Development. 2025. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/education (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. What You Need to Know About Education for Sustainable Development. 2024. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/education/need-know?hub=72522 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Chang Rundgren, S.N. The effect of implementation of education for sustainable development in Swedish compulsory schools–assessing pupils’ sustainability consciousness. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovais, D. Students’ sustainability consciousness with the three dimensions of sustainability: Does the locus of control play a role? Reg. Sustain. 2023, 4, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, Y.; Eksili, N.; Koksal, K.; Celik Caylak, P.; Mir, M.S.; Soomro, A.B. Who Is Buying Green Products? The Roles of Sustainability Consciousness, Environmental Attitude, and Ecotourism Experience in Green Purchasing Intention at Tourism Destinations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confetto, M.G.; Covucci, C.; Addeo, F.; Normando, M. Sustainability advocacy antecedents: How social media content influences sustainable behaviours among Generation Z. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 758–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Ismail, A.; Ghalwash, S. The rise of sustainable consumerism: Evidence from the Egyptian generation Z. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.H.; Tsai, C.H.; Chen, M.H.; Lv, W.Q. US sustainable food market generation Z consumer segments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, F. Interconnected Eco-Consciousness: Gen Z Travelers’ Intentions toward Low-Carbon Transportation and Hotels. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiernik, M.; Ones, B.S.D.; Dilchert, S. Age and environmental sustainability: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 826–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N.; Michaut-Denizeau, A. Are millennials really more sensitive to sustainable luxury? A cross-generational international comparison of sustainability consciousness when buying luxury. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seock, Y.K.; Shin, J.; Yoon, Y. Embracing environmental sustainability consciousness as a catalyst for slow fashion adoption. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 4071–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pookulangara, S.; Shephard, A.; Liu, C. Using theory of reasoned action to explore” slow fashion” consumer behavior. In International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings; Iowa State University Digital Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2016; Volume 73. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, R.; Bisai, S. Factors influencing green purchase behavior of millennials in India. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 29, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.K.; Gupta, A.; Verma, H.; Anand, V.P. Embracing green consumerism: Revisiting the antecedents of green purchase intention for millennials and moderating role of income and gender. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Manag. Inform. 2023, 9, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Rani, V.; Rani, G.; Rani, M. Does individuals’ age matter? A comparative study of generation X and generation Y on green housing purchase intention. Prop. Manag. 2024, 42, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M.N.M.; Jumain, R.S.A.; Yusof, A.; Ahmat, M.A.H.; Kamaruzaman, I.F. Determinants of generation Z green purchase decision: A SEM-PLS approach. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2017, 4, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Nonino, F.; Pompei, A. Which are the determinants of green purchase behaviour? A study of Italian consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2600–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazish, M.; Khan, M.N.; Khan, Z. Environmental sustainability in the digital age: Unraveling the effect of social media on green purchase intention. Young Consum. 2024, 25, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, L.; Sousa, B.B. The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire: Validation Among Portuguese Population. Sustainability 2025, 17, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Dikken, J. Revealing sustainable mindsets among older adults concerning the built environment: The identification of six typologies through a comprehensive survey. Build. Environ. 2024, 256, 111496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraslan, M.; Kir, S.; Turan, M.B.; Iqbal, M. Sustainability Consciousness and Environmental Behaviors: Examining Demographic Differences Among Sports Science Students. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.E.S.; Ghallab, E.; Hassan, R.A.A.; Amin, S.M. Sustainability consciousness among nursing students in Egypt: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puđak, J.; Šimac, B.; Trako Poljak, T. What drives pro-environmental behavior in rural Croatia? The role of environmental attitudes and well-being. Soc. Ecol. Pract. Res. 2025, 7, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandarić, D.; Hunjet, A. Does the Education Level of Consumers Influence Their Recycling and Environmental Protection Attitudes? Evidence From Croatia 2023. Naše Gospod. Our Econ. 2023, 69, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandarić, D. Gender Disparities in Pro-Environmental Attitudes: Implications for Sustainable Business Practices in Croatia. J. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2024, 9, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patino-Toro, O.N.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Palacios-Moya, L.; Uribe-Bedoya, H.; Valencia, J.; Londoño, W.; Gallegos, A.; Bloor, M. Green Purchase Intention Factors: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2356392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Jain, R. Factors influencing green purchase intention and convincing and relational value: An empirical study on gen Z consumers from an Indian perspective. J. Gen. Manag. Res. 2022, 9, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kianpour, K.; Anvari, R.; Jusoh, A.; Othman, M.F. Important motivators for buying green products. Intang. Cap. 2014, 10, 873–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Hua, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, G. Determinants of consumer’s intention to purchase authentic green furniture. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, F.C.; Ahmad, A.Z. The effect of demographic factors on consumer intention to purchase green personal care products. In Proceedings of the INSIGHT 2018 1st International Conference on Religion, Social Sciences and Technological Education, Nilai, Malaysia, 25–26 September 2018; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, I.; Shah, S.M.; Hanceraj, S.; Lohana, S.; Memon, R. The Influence of Age on Purchase Intention of Eco-Friendly Products: Evidence from Hyderabad, Sindh. Int. J. Entrep. Res. 2019, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, P.; Richard, G.G.; Olena, K.; Gusti, A.I. The Influence of Involvement and Attribute Importance on Purchase Intentions for Green Products. In Book Marine Plastics: Innovative Solutions to Tackling Waste; Grimstad, S.M.F., James, N.A., Ottosen, L.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalanon, P.; Chen, J.S.; Le, T.T.Y. Why do we buy green products? An extended theory of the planned behavior model for green product purchase behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.A.; Tix, A.P.; Barron, K.E. Testing Moderator and Mediator Effects in Counseling Psychology Research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantillo, J.; Astorino, L.; Tsana, A. Determinants of pro-environmental attitude and behaviour among European Union (EU) residents: Differences between older and younger generations. Qual. Quant. 2025, 59, 2623–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Janssen, M. How and why does the attitude-behavior gap differ between product categories of sustainable food? Analysis of organic food purchases based on household panel data. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 595636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).