Abstract

In the face of the growing water crisis and current environmental pressures, rural communities with a tourism vocation face significant challenges in preserving their ecological and cultural integrity. These communities, whose livelihoods depend on their interaction with tourism dynamics and their territory, constitute a complex system in which sustainability challenges cannot be addressed in isolation. This study develops a systemic diagnosis of La Magdalena Atlitic, a rural community located in the south of Mexico City, through the application of the Viable System Model (VSM), complemented by the principles of agile governance. The objective is to understand how social enterprises contribute to sustainable water management through their tourism products and services. Drawing on field visits, semi structured interviews and participatory workshops, three operational units sustaining the system in focus were identified. The findings show that although these units are dynamic, weaknesses persist in coordination, control and auditing, which limits the feedback capacity of the system under study. The integration of agile governance reveals the community’s potential to transform reactive practices into efficient mechanisms, strengthening collaboration and participatory decision-making. This approach demonstrates that the synergy between the VSM and agile governance promotes water sustainability and the resilience of socio ecological systems.

1. Introduction

Ensuring the supply of drinking water in cities whose population exceeds their carrying capacity [1,2] is becoming an increasingly complex task. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as part of the 2030 Agenda, have facilitated the implementation of actions and strategies focused on global sustainability, while also providing significant statistical data at national and regional levels.

According to the United Nations [3], within the framework of SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, it was reported in 2022 that 43% of the population in Mexico had access to safely managed drinking water services. In contrast, data from 2023 indicated that only 57% of the monitored water bodies in Mexico had an adequate quality for human consumption, while 41% of the country’s water resources were managed through an integrated approach.

These data make visible the mixed outlook regarding the progress and the limitations that persist in Mexico in achieving sustainable water management. In relation to this, overtourism can intensify the situation, as its dynamics alter the environment, particularly water resources. It is also important to note that the country ranks among the ten destinations with the highest volume of international tourism [4], generating both benefits and detriments when additional actors are integrated into this complex dynamic.

Specifically, Mexico City, with an estimated population of 9.2 million inhabitants in 2020 [5], embodies these challenges: overpopulation and overtourism, which unfold daily in environmentally weakened natural areas. The metropolis is subdivided into sixteen boroughs, each with distinctive cultural and socio-economic characteristics. Additionally, the city contains a total of fifty rural communities that add a further layer of diversity to its structure [6]. This complexity reflects the richness and heterogeneity of the urban–rural fabric that inhabits the city, presenting specific challenges regarding water management and tourism dynamics, where different realities and needs become intertwined simultaneously.

Some studies highlight that when tourism is developed under approaches centred on socio-environmental benefit, it can help address the challenges derived from overtourism [7,8]. Within this framework, social entrepreneurship emerges as a natural complement, as it promotes initiatives that combine local development with environmental conservation, jointly contributing to the creation of more sustainable tourism services and products [9]. The continuity of rural tourism in areas with water bodies depends directly on the management of the natural and human resources that sustain the ecological dynamics of the territory. Understanding how social enterprises organise themselves to preserve water resources while maintaining sustainable tourism activities has become a central challenge for these communities.

The aim of this research is to develop a systemic diagnosis of the social enterprises in the rural community located in the south of Mexico City known as La Magdalena Atlitic (LMA), identifying how their structures and decision-making processes promote and support sustainable water management through practices that adapt to current socio-environmental challenges. The research is organised as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature to contextualise the system under study; Section 3 outlines the methodological framework, study area, and data collection process; Section 4 presents the diagnosis and its integration with agile governance; Section 5 develops a critical discussion of the literature consulted and the findings obtained; and finally, Section 6 offers the main contributions and limitations.

2. Literature Review

Entrepreneurship concept has its roots in the late eighteenth century with Adam Smith [10], who introduced the words ‘projector’ and ‘undertaker’ to describe individuals performing administrative and managerial functions within individual projects. This recognition of actors engaged in innovation and economic activity led other economic theorists such as Say, Mill, Marshall and Schumpeter [11,12,13,14], to expand and consolidate the concept.

This conceptual evolution reflects how entrepreneurship has been understood as a higher-order activity linked to innovation, risk-taking and the capacity to generate structural change within the economy and society. Nowadays, entrepreneurship continues to be part of a complex system directly influenced by factors such as the environment, public policies, government strategies, and society. It is even considered that national culture plays a significant role in the way entrepreneurship is practised and developed [15].

As a result of these multiple influences, the role of entrepreneurship has been reconsidered, shifting its focus towards the social sphere and the generation of collective benefit. Although there is currently no universally accepted definition of the term ‘social entrepreneurship’, the literature acknowledges contributions such as that of Dees [16], who defines it as the identification and exploitation of opportunities for transformative social change by visionary individuals.

Although there are different interpretations regarding its social scope, the literature highlights its value, as it emerges from the application of innovative approaches oriented towards sustainability [17]. It is also recognised that social entrepreneurship addresses local challenges using the resources of individuals (entrepreneurs) with the aim of offering solutions and driving transformations to real problems [18].

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship and Its Link to Rural Tourism

Particular attention is given to the ways in which rural communities confront contemporary challenges, as their modes of organisation, their relationships with the natural environment, and their communal practices directly influence their capacity to adapt and sustain their livelihoods. Their connection with social entrepreneurship lies in the fact that most rural communities become tourist destinations due to their high socio-cultural and ecological value, which serves as a significant motivation for visitors.

Building on this, the tourism products and services developed by entrepreneurs aim not only to generate income but also to strengthen and preserve their cultural identity, while maintaining sustainability in their activities and safeguarding the natural resources on which they depend [19]. Social entrepreneurship can foster creative environments within these communities, as the projects they generate are oriented towards improving their reality in the face of challenges, particularly in environmental conservation, water stewardship, and cultural revitalisation [20]. An example of this can be observed in Iran [21], where social enterprises have significantly contributed to transforming tourism dynamics towards a more sustainable model.

These practices strengthen the local economy, enabling the achievement of both social and international goals such as the SDGs. The study of such cases in rural communities with a tourism vocation provides valuable insights for the design of policies and the implementation of practices that foster rural tourism rather than reproducing mass tourism [22,23]. Spain, which combines densely populated cities with rural communities affected by urban expansion, have found in rural tourism a solution that requires the implementation of rural adaptation policies to avoid compromising the environment [24].

Another example can be found in the rural areas of the Balinese islands in Indonesia, where the use of natural resources is based on principles of preservation and the appreciation of Indigenous knowledge. This approach seeks to meet tourism demand without irreversibly transforming the rural area, thus preventing the negative impacts associated with overtourism [25]. In Miao, China, a study explored the growth of rural tourism and how social enterprises have driven sustainable economic development in the region’s rural areas, particularly benefiting women artisans by improving their income and social standing [26].

In contrast, in Bodaofeng Forest Farm, China, rural tourism fosters a constant negotiation between modernisation and tradition. Through this process, communities reconfigure their identities to integrate into the contemporary tourism economy without abandoning their cultural roots, leading to a complex social transformation [27]. Another study, also conducted in China, revealed that the success of social enterprises largely depends on two factors: 1. Legitimacy, represented by the recognition and acceptance they receive from both the community and governmental institutions, and 2. Social capital, understood as the networks of trust, cooperation, and reciprocity built within the community [28].

In the Philippines, strategies have been implemented to develop social enterprises offering tourism products based on sustainable farms, where visitors engage in educational experiences about ecological farming techniques. These enterprises generate economic and social benefits by promoting environmental education and strengthening community resilience [29]. In the case of Mexico, the implementation of a systemic model has helped social entrepreneurship in rural tourism contexts advance towards the SDGs, fostering collective benefit and cultural strengthening within the community [30].

The connection between social entrepreneurship and rural tourism is particularly relevant because it provides communities with tools to adapt to external pressures through projects that prioritise collective participation and the responsible use of resources [31]. In this way, rural tourism transcends its economic dimension to become a space for social innovation and resilience in the face of current contexts characterised by uncontrolled urbanisation and pressure on water systems.

2.2. Water Management in Rural Communities

The level of water consumption in rural areas varies according to their geographical, social, and economic characteristics, as well as the degree of urbanisation of their surroundings. In the case of rural communities with a tourism vocation, water consumption patterns are usually lower than in urbanised areas [32]. However, it is important to consider the type of tourism dynamic that prevails. Examples include overtourism, sun and beach tourism, rural tourism, religious tourism, and health tourism, among others.

The predominant form of tourism in a community can generate either benefits or negative impacts, depending largely on its intensity and the community’s capacity to manage it. The relevance of this situation lies in the ecological vulnerability of rural territories, which makes the effective coordination of local actors essential [33]. Achieving meaningful results from such coordination will depend on the application of integrated and adaptive approaches that acknowledge the socio-ecological complexity these areas face.

Specifically, tourism dynamics involve substantial water consumption, and implementing public policies related to water conservation and management has become an urgent necessity rather than a genuine transition grounded in collective awareness. It is now essential to advance towards measures that balance tourism development and growth, particularly in natural areas or places characterised by water bodies and river basins [34]. Studies warn that overtourism is the main challenge in rural areas, as it leads to pollution, excessive waste generation, and ecosystem degradation [35].

In this context, adopting sustainable water management emerges as an effective strategy, as it is estimated that it can reduce water consumption in tourism facilities by up to 30%, directly contributing to the reduction of tourism’s environmental impact [36]. Moreover, it is important to identify the role of each actor involved in tourism dynamics in order to achieve meaningful change. Some of these actors include tourism managers and local authorities, who are responsible for designing public policies capable of integrating other stakeholders, both public and private, and anticipating potential unfavourable scenarios [37].

Within this framework, water management in rural communities involves the development of a collaborative governance process in which local actors, community representatives, authorities, tourism managers, and social entrepreneurs actively participate in decision-making [38]. Such involvement helps eliminate practices that treat water resources as elements solely for tourism, instead recognising them as common goods essential for daily life and cultural preservation.

Research has shown that when water management incorporates the voices of rural communities, it leads to integrated and resilient arrangements capable of responding to crises such as prolonged droughts, appropriation, and overexploitation of aquifers. Social enterprises can also play a strategic role in this context, acting as mediators between the demands arising from tourism dynamics and the needs of the community.

This demonstrates that water management in rural areas with a tourism vocation requires a systemic perspective that addresses the immediate pressures of overtourism while anticipating future scenarios associated with climate change and the expansion of urban areas. To achieve this, it is essential to integrate models, practices, and mechanisms that operate across multiple levels of reality, where community initiatives, public policies, and technological innovation converge. Recognising this complexity enables the adoption of water governance frameworks that also ensure sustainability within tourism dynamics and safeguard the wellbeing of present and future generations.

2.3. SDG 6 in the System Under Study

At present, sustainability has become a central axis for the development of daily life. Sustainability seeks to guarantee wellbeing and equity for present and future generations [39]. This approach proposes a vision that aims to balance economic growth, the conservation of natural resources, and human activity. The implementation of sustainable practices in rural tourism becomes essential, as it responds to the challenges that tourism itself generates within these territories.

SDGs 6, 8, and 13 have become guiding principles for the responsible planning and management of tourism. In particular, SDG 6 holds special relevance for rural areas with a tourism vocation, where water management symbolises a basic right for environmental preservation [40]. Integrating this goal into rural life strengthens water governance, understood as a common good, to promote management models that ensure its continued availability and quality.

At the global scale, water consumption associated with tourism constitutes less than 1% of total water use [41], although this percentage can increase significantly in destinations where water supply is limited or seasonal. In rural communities such as LMA, this pressure intensifies during periods of high tourist influx, affecting the territory in a systemic manner.

Several studies emphasise the need to incorporate participatory approaches that align local actions with the principles of SDG 6 [42,43]. Considering the issue addressed in this research, the components presented in Table 1, may represent new lines of inquiry that can be approached from a transdisciplinary perspective.

Table 1.

Components that contribute to the monitoring of SDG 6.

These components are embedded within the system under study, generating contributions that enable rural communities to adapt SDG 6 to their specific contexts. The need to implement water governance models is evident, as they acknowledge that water is the central element linking environmental homeostasis, social cohesion, and the economic viability of the territory.

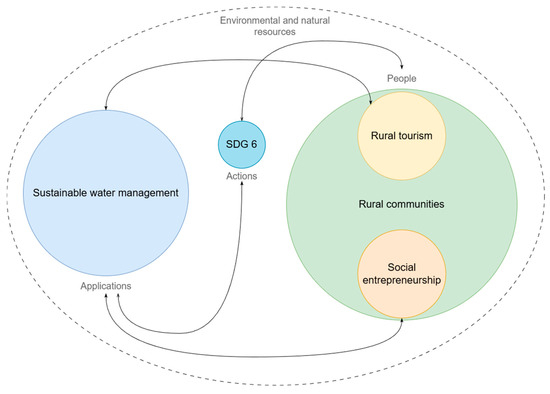

In this regard, the literature reviewed thus far clearly identifies the role of social entrepreneurship, which is recognised as a node connecting these dimensions. It drives the economic activities of rural tourism while also possessing the collective capacity to support water conservation, particularly in territories where the tourism offering depends directly on the quality and availability of water resources. Figure 1 is the result of a synthesis of this relationship between social entrepreneurship, rural tourism, and sustainable water management as an integrated feedback system that strengthens community resilience and organisational viability.

Figure 1.

Systemic relationship among components converging within a shared environment. Source: Author’s own work.

The relationship between social entrepreneurship, rural tourism, and water management is neither accidental nor secondary; it constitutes the central structure of the socio-ecological system of the territory. The products and services generated by social enterprises align with sustainability principles through concrete practices that protect the water resources upon which tourism activity depends.

For this reason, this research takes social entrepreneurship as its point of departure to understand how rural communities construct their own governance mechanisms, define their collective agreements, confront external pressures, and collectively adapt the principles of SDG 6 to their territorial reality, or whether such mechanisms are still absent or fragmented. This can be understood by recognising the organisational functions of these enterprises within the system under study.

2.4. Agile Governance

The agility is understood as the capacity and speed of adaptation of an organisation to respond more effectively to environmental changes [44], this concept has gained relevance within complex human activity systems. This complexity compels organisations to adopt this approach due to its advantages, as it enables them to maintain an agile capacity that strengthens their connections with other levels of reality (macro-, meso-, and microenvironments).

Traditional literature on corporate governance focuses primarily on structures that are easy to measure in terms of size and composition, as well as on cost reduction, which may obscure other relevant aspects such as adaptive capacity [45]. This limitation has given rise to emerging concepts such as agile governance, understood as the ability of organisations to balance control and flexibility in decision-making by adapting their governance processes to enhance the quality of those decisions.

The implementation of flexible governance models that eliminate hierarchical structures and promote collective participation enables responses aligned with the organisation’s continuous learning [46]. Possessing this characteristic enhances organisational performance, particularly in those seeking to remain viable over time. Agile governance also benefits social enterprises, even when they are not formally established organisations, as it strengthens their connection with the environment while fostering adaptability and the capacity to generate meaningful structural transformations. Governance is key to making this possible, as it can create systems and processes that are self-managed voluntarily [47].

This approach involves interdisciplinary collaboration, transparency, review, and distribution cycles, and is characterised by open information flows. It translates into processes where trust, reciprocity, and cooperation function as regulatory mechanisms, replacing organisational rigidity with responsible autonomy that remains coherent with its social purpose.

Models such as Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM) [48] offer a connection between viability and organisational structure. This model proposes that a system’s viability depends on the balance of five interrelated subsystems that ensure internal cohesion and the capacity to respond to changing environmental conditions. The VSM enables organisations to maintain stability without losing autonomy or operational flexibility.

Agile governance complements this model by introducing the dynamism required for the system to remain both viable and adaptive, bringing fluidity and openness to the VSM methodology. Together, these perspectives provide a more comprehensive understanding of the organisation as a living system capable of learning and transformation.

The conditions of rural environments could benefit from this integration, as social enterprises face constant tension between cultural preservation, environmental sustainability, and the pursuit of economic wellbeing. Analysing their functioning through the complementarity of the VSM would improve the understanding of their integration and development.

Systems thinking thus becomes a framework for promoting viable organisational systems that are aware of their environment and capable of self-transformation. This theoretical foundation establishes the basis for addressing, in the following section, the diagnostic process of social enterprises in LMA.

3. Method

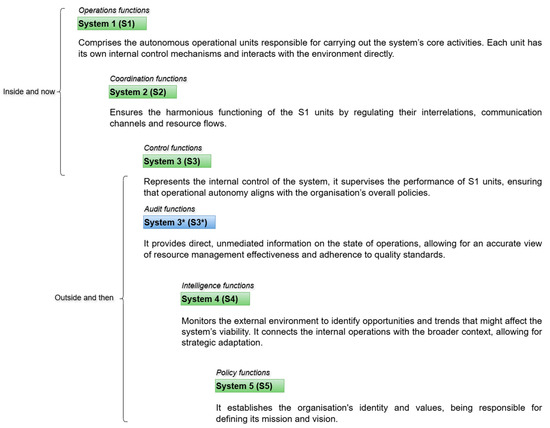

The VSM, developed by Beer [48], was designed to ensure the sustainability and adaptability of organisations operating in environments characterised by complexity and constant change. Its core principle asserts that every system must possess a set of essential functions that allow it to maintain internal stability while adapting to external dynamics. The model is structured around five interconnected systems (Figure 2), each performing a distinct but complementary role.

Figure 2.

Functions of the systems within the VSM. Source: [49,50].

Each system represents essential functions that every organisation must have to adapt effectively to its environment and ensure long-term sustainability. A viable and sustainable organisation is one that is capable of existing independently without detaching from its ecological and social focus, while remaining aligned with the needs of future generations [51].

Through the interaction of its systems, the model offers a cybernetic lens that allows autonomy to emerge and be sustained. In this study, the VSM was complemented with the agile governance approach, introducing a dynamic layer that helps reveal how social enterprises learn collectively and reorganise their structures in response to change.

This combination helps close the distance between everyday operations and strategic purpose, connecting the specific roles of each system in the VSM with agile practices. When these two perspectives meet, the system is better able to stay balanced and to adapt with resilience as conditions around it become more complex and uncertain.

The strength of this model lies in its ability to help organisations remain viable over time. This makes it especially useful for studying social enterprises rooted in rural communities with a tourism vocation, where environmental and social pressures demand adaptive responses that can protect both local identity and cultural integrity.

3.1. Study Area

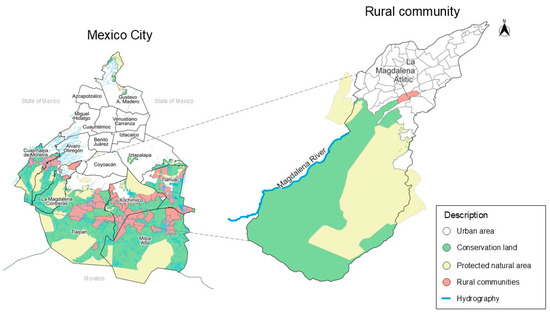

For this research, the study area selected was LMA, located within the borough of La Magdalena Contreras (Figure 3), which covers an area of 63.4 km2. This rural community maintains a close relationship with the Magdalena River, considered the last living river in Mexico City, with a total length of 28.2 km from its source to its confluence with the Churubusco River, of which 14.8 km are situated within conservation land [52].

Figure 3.

Multi-scale map of Mexico City and the rural community under study. Source: Author’s own work based on INEGI [53] data. Note. Spanish place names are kept as they correspond to the official identification of the boroughs in Mexico City.

The conservation land within the borough covers approximately 2993 hectares of forest and provides around 19.7 million cubic metres of water per year, supplying approximately 78,500 inhabitants of the borough and its neighbouring areas. This constitutes an environment of high ecological value that supports essential environmental processes for human life (Table 2), making LMA a fundamental actor in sustainable water management due to its direct relationship with the river.

Table 2.

Division by zones of the Magdalena River.

The areas surrounding the Magdalena River display significant differences, with marked contrasts between conservation and degradation caused by the urban expansion. These contrasts reveal the interrelations between ecological processes and local social dynamics, forming the context in which the social enterprises of LMA have emerged. These enterprises work to strengthen community cohesion through the tourism experiences and products they share with visitors. At the same time, they strive to build forms of local governance that can respond with resilience to the socio-environmental pressures brought about by overtourism.

3.2. Instruments

This research focuses on LMA (Figure 3) and seeks to understand its strengths, limitations, and adaptive capacity in facing the pressures of overtourism and its effects on the Magdalena River. From this perspective, it becomes possible to evaluate how the existing governance mechanisms operate in practice and how agile they are when responding to shifts in tourist demand, ecological conditions, and other external factors.

To collect information, field visits were conducted throughout 2024, complemented by virtual sessions held in August and September 2025, as shown in Table 3. These activities made it possible to carry out semi-structured interviews, direct observation, and participatory workshops with local actors from LMA, including community representatives, entrepreneurs, and members of the Centro de Estudios de la Cuenca del Río Magdalena (CE), a social organisation dedicated to the dissemination and study of the Magdalena River basin.

Table 3.

Data collection instruments.

The combination of these instruments facilitated the documentation of organisational dynamics and practices related to water management and rural tourism, becoming a key step in engaging the community in the research process. The full questionnaire used in the semi structured interviews can be consulted in Appendix A.

4. VSM Diagnosis

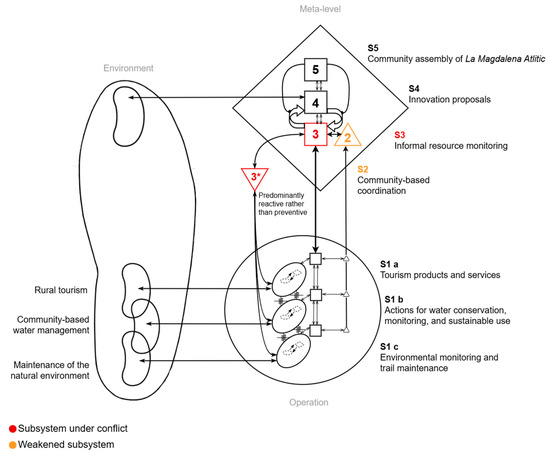

The application of the VSM reveals the organisational structure existing within the social enterprises associated with tourism and water management. This model (Figure 4) illustrates how they currently operate within a complex scenario.

Figure 4.

VSM of the system under study. Source: Author’s own work.

The diagnosis shows that social enterprises operate as the core operational component of the system, which are structured in the following operational units:

- S1a: Rural tourism initiatives and the provision of local products and services such as guided tours, food and craft sales, hiking, and cultural experiences.

- S1b: All activities focused on the care, monitoring, and use of the water resource in Magdalena River, including channel cleaning and agreements on water use among rural community.

- S1c: Practices that promotes environmental maintenance through reforestation and the cleaning of trails within Los Dinamos Park (conservation land).

Each of these units performs autonomous yet interdependent functions, linked through informal communication and collaborative agreements. Together, they constitute the productive structure that sustains the system under study.

S2 shows the synchronisation and coordination mechanisms among the operational units (S1a, S1b and S1c), designed to prevent conflicts and redundancies. This corresponds to the community-level coordination processes that regulate interactions between the operational systems. The diagnosis revealed that such coordination relies heavily on individual commitment and mutual trust among community members, which makes it vulnerable to internal tensions and the lack of formal procedures. Despite the existence of a local collaboration network, communication among its members remains inefficient, leaving the system weakened by both internal and external disruptions.

During the interviews, one entrepreneur remarked, “Sometimes too many people arrive at once, but since only a few of us know the routes, the trails deteriorate because people wander off elsewhere.” Other members of the community noted that the river is an essential part of their work, yet it is not always possible to keep it clean: “If the water flows down dirty, people no longer want to come to see the river. They only walk around the food stalls and the viewpoint, and that affects our income.”

S3 is in a fragile condition that reflects the system’s limitations in sustaining a culture of sustainability. Control activities, such as monitoring the use of water within tourism dynamics and maintaining the surrounding environment, are carried out based on informal agreements and collective supervision that relies more on the goodwill of those involved than on official and standardised mechanisms. During a field visit, it was observed that supervision practices operate through verbal agreements. A member of the community explained, “We do not have an exact record of the water we use. I am not aware of one. I think we simply rely on how the river flows.” This type of evidence illustrates why the system responds reactively to environmental changes.

The management of both the enterprises and the water resource also follows this reactive logic, with actions taken in response to contingencies such as a decrease in river flow, the accumulation of waste along trails, or conflicts among tourism service providers. This lack of monitoring and performance evaluation instruments prevents the availability of accurate data on water consumption in LMA and on the environmental impacts generated by mass tourism, or even rural tourism if they existed, directly hindering agile decision-making and effective feedback to higher subsystems.

S3*, in turn, is in a state of conflict, as no external correction mechanisms were identified, nor the occasional involvement of governmental institutions such as the administrative authorities of La Magdalena Contreras Borough or the environmental and tourism departments at their various levels. The absence of these processes limits the potential of S3* and restricts the ability to understand the current state of the system under study from an external perspective.

It is also important to consider other external actors from the academic and social spheres. In this regard, the role of the CE (comprising both local residents of LMA and external participants) stands out, as it sustains much of S3*’s functioning by providing external information that stimulates internal improvement and reconfigures the links among subsystems. Examples of this include technical assistance in socio-environmental projects, joint clean-up campaigns, and meetings to define water use boundaries. These activities introduce more structured control practices and promote transparency in resource management.

S4 represents the organisational and adaptive intelligence of the system under study, responsible for environmental observation, anticipation of change, and the generation of innovation. Within this subsystem, practices of collective learning were identified, emerging from the interaction between social enterprises and the aforementioned external actors (academic institutions and environmental organisations).

In this system, it was possible to recognise the articulation of local practice with technical and scientific knowledge, alongside the creation of strategies for water management, improvement of tourism services, and environmental conservation. This organisational intelligence also integrates local knowledge with traditional practices and the accumulated experience of the community, a fundamental aspect for agile governance, which recognises learning as a distributed and collaborative process.

Likewise, to strengthen systemic viability, S4 could consolidate internal intelligence mechanisms that do not rely exclusively on projects initiated by governmental institutions. A strategy applicable to this context would be the creation of community learning spaces, where the results of local experiences and management agreements are recorded and shared as part of a collective memory.

S5, which represents the system’s identity and overarching purpose, was recognised in the community assembly of LMA. This assembly serves as a collective space where rules are agreed upon, decisions about resource use are validated, and the actions of local enterprises are guided toward a shared goal, protecting the Magdalena River and curbing overtourism to secure the continuity of rural and other low-impact tourism activities.

These two core pillars of the system play not only a normative but also an ontological and cultural role, nurturing the sense of belonging and mutual care that gives legitimacy to collective action. Yet, this balance is not static, it can shift as community conditions evolve, sometimes placing pressure on the LMA assembly to pursue goals that differ from those initially shared. Overcoming these systemic distortions will require the creation of agile processes that can redirect reactive tendencies and restore adaptive learning within the community. As in S4, bringing agile governance into this kind of setting helps replace rigid hierarchies with more participatory ways of working. It encourages continuous learning, where decisions are revisited and adjusted as environmental and social conditions evolve.

The diagnosis also showed that the system under study faces a constant challenge, keeping all actors aligned and cohesive. Tensions often arise between those who seek to strengthen rural tourism and those who view it as a potential threat to environmental balance. These opposing views suggest that the system’s identity is not fixed but rather in a state of ongoing redefinition. From a cybernetic standpoint, such tension should not be seen as a weakness but as a sign of evolution, a process through which the community learns to embrace diversity while avoiding fragmentation.

The synthesis of the five systems allowed know that the viability of the system under study depends on its capacity to balance autonomy and cohesion. S3, S3* and S2 present weaknesses and structural conflicts that limit feedback and the generation of reliable information for decision-making. This situation helps to explain why management practices are still largely intuitive and reactive instead of preventive or strategic.

Proposed Integration of Agile Governance into the VSM

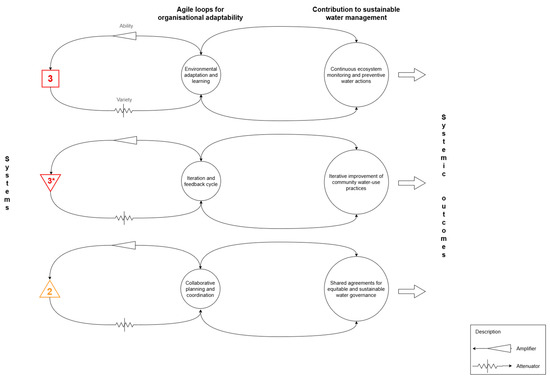

Agile governance helps communities make better decisions when facing complex and changing conditions. In practical terms, it means that the system can adjust its strategies as environmental pressures or tourism demand shift, while still preserving a shared sense of identity. Figure 5 shows how the principles of agile governance are woven into the VSM, offering a way to strengthen the system under study.

Figure 5.

Systemic integration of agile governance. Source: Author’s own work.

S2, S3, and S3*, identified in the diagnosis as weak and conflict-prone, are each linked to an agile loop designed to improve coordination, control, and learning processes within the community. These loops make it possible to visualise the transition from a reactive system to one oriented towards collaborative action and continuous improvement.

Each agile loop acts as a mechanism that helps the organisation stay viable amid environmental and tourism-related changes. It encourages people to co-create solutions and make decisions together. Through this process, the system becomes more flexible, sparks innovation, and nurtures collective learning, all elements that, working in unison, enhance its overall effectiveness.

The integration of agile loops strengthens sustainable water management by helping the system anticipate, coordinate, and adapt to environmental and social change.

- The first loop, associated with S3, reinforces the system’s connection to its environment by enabling early detection of changes affecting the Magdalena River and promoting preventive actions to support its conservation. This aligns with the system’s ability to readjust its strategies as environmental conditions or tourist demand vary. For instance, during peak tourist seasons, the community may organise environmental committees or volunteer days to clean the river and forest, optimise water use in tourism services, and strengthen communication among enterprises. These collective activities function as improvement iterations that consolidate a more preventive and less reactive governance.

- The second loop, linked to S3*, tries to replace the reactive tendency with processes of review, learning, and continuous improvement, which are characteristic of agile approaches. Through this dynamic, local actors are able to regularly review how water resources are monitored and maintained, recognising which actions have worked and which ones need to be improved. This process helps redefine priorities, redirect resources, and strengthen coordination among the groups involved in water use and conservation.

- The third loop, connected to S2, encourages cooperation among local enterprises and actors through flexible agreements, shared planning, and rotating responsibilities, avoiding the creation of rigid hierarchies. These dynamics are similar to community planning meetings, where local teams coordinate tourism, conservation, and environmental education activities. For instance, when tourist demand suddenly rises, the community organises shifts, adjusts routes, or rearranges visitor logistics, showing a self-organising process that reflects both agile principles and the sustainable use of water in the territory.

Taken together, these loops foster collective learning and strengthen the system’s ability to stay viable, turning water management into a process that feels both proactive and resilient. The aim of this proposal is to support the community’s transition from a reactive mode of operation to one shaped by agile governance, a space where water sustainability is not merely maintained but constantly reimagined in response to the complex realities that surround it.

These agile loops offer a concrete way of contributing to the aims of SDG 6. As feedback, coordination, and water governance mechanisms become stronger, the community gradually shapes an organisational model that protects the quality and availability of its water while sustaining its long-term viability. In practice, this experience illustrates how systemic and agile approaches can turn into practical pathways for advancing SDG 6 at the local level, helping to close the gap between global sustainability goals and the everyday realities of rural communities.

5. Discussion

The diagnosis carried out through the VSM helped reveal the main strengths, weaknesses, and tensions within the social tourism enterprises of LMA, along with their potential to promote sustainable water management through their organisational practices. These findings are consistent with earlier studies that have applied organisational cybernetics to community-based and complex systems [55,56,57], showing that the use of the VSM can strengthen organisational resilience.

The findings revealed that the operational subsystems S1a, S1b, and S1c maintain strong interconnections, integrating economic, ecological, and cultural activities that sustain the community as a whole. However, this strength has not yet translated into effective coordination, control, and auditing mechanisms (S2, S3, and S3*). Consequently, information gaps remain, disrupting communication flows among units and limiting collective learning processes.

These systemic pathologies can be reframed as opportunities to evolve towards states of homeostasis and organisational balance. The integration of agile governance provided a pathway to overcoming structural rigidity and operational limitations, reinforcing collective learning processes within the system. Through participatory mechanisms, social enterprises can adjust their tourism products and services in response to the complexity of their environment, for instance, by reconfiguring operations during fluctuating tourist seasons or adapting practices to changes in the Magdalena River’s water flow.

The intelligence (S4) and identity (S5) systems stood out as vital processes that nurture community resilience through continuous learning. The S4 acts as a bridge between the community and its external environment, fostering partnerships with universities, environmental organisations, and institutional actors. This highlights the need to consolidate an organisational intelligence capable of sustaining innovation beyond temporary external interventions. Building such intelligence ensures that the community’s development remains internally driven, contextually relevant, and adaptable to environmental and social shifts. The S5, in turn, embodies the identity and overarching purpose of the system, manifested through the community assembly that safeguards the coherence of collective values.

At this level, agile governance reinforces the teleology of the system under study, enabling the integration of autonomy and flexibility, both essential principles of organisational viability as outlined by Beer [50]. The coexistence of multiple actors (entrepreneurs, local authorities, and tourists), within the same systemic environment revealed the pressing need to reinforce communication and feedback among them. When these connections improve, coordination becomes smoother, mutual understanding deepens, and responsibility in decision-making starts to be genuinely shared.

The findings obtained are supported by the instruments used for data collection. The voices of the community, expressed in comments such as “we, as a community, cannot live within its territory but we can manage it”, “many only want to make money by taking people to the fourth ‘Dinamo’ or further up the river”, “there are no clear agreements”, made it possible to contrast the systemic diagnosis with real practices and to reveal conflicts and weaknesses within the system under study.

Currently, information within the system circulates in a fragmented way, with few formal feedback mechanisms, which limits the community’s capacity to make well-informed and timely decisions. Introducing agile tools such as periodic system reviews, simplified monitoring indicators, and collaborative work cycles among community members could improve traceability in decision-making and strengthen water resource management.

The community operates in a partial state of viability, while the operational systems display vitality and ongoing activity, the management systems require further development to attain long-term autonomy and stability. This imbalance exposes structural weaknesses that constrain the system’s ability to remain coherent and to adapt to changing circumstances.

The connection between the VSM and agile governance opens the door to designing organisations that are alive, self-reflective, and resilient, where a shared sense of identity becomes the thread that ties collective action to sustainable water management. When systemic principles meet agile practices, communities like LMA can shape mechanisms that remain structured yet adaptable, capable of responding proactively and with sensitivity to the environmental and social dynamics of their context.

Within the Systemic Approach, this transition introduces a necessary dynamic element, the ‘how’ to achieve homeostasis grounded in the teleology of the system under study. It encourages the strengthening of the community’s organisational capacity and collective learning, allowing it to thrive amid complexity while remaining faithful to its ecological and cultural purpose.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the application of the VSM, together with the principles of agile governance, constitutes an effective tool for diagnosing the organisational viability of social enterprises in rural communities with a tourism vocation such as LMA. This approach identified the mechanisms that enhance the activities and processes of social enterprises and how these can foster more sustainable water management within tourism dynamics.

The findings are also supported by the literature reviewed, which shows that the central axis of community organisation in rural territories depends largely on the adoption of sustainability and collective learning. The studies consulted also indicate that in contexts of this nature, where the environment constitutes a fundamental basis for economic activity, as in the case of rural tourism, it is crucial to ensure community resilience through the real implementation of mechanisms and activities capable of coordinating and generating agreements [58,59].

These demands for adaptation become an opportunity to apply the VSM as an agent of change. In this case, the model indicated that resilience depends on the system’s capacity to coordinate its operational units, anticipate change and maintain a shared identity. For example, the tensions identified between mass tourism, the community and water revealed the need to strengthen these functions (coordination (S2), control (S3) and intelligence (S4)).

Highlighting the results obtained in each system of the model, S1 holds an important position within the system under study, as it encompasses the economic, ecological and cultural activities that sustain community life in LMA. Likewise, the weaknesses and conflicts detected in S2 and S3 demonstrate the need to shift from a reactive stance to preventive and strategic management, based on reliable information and continuous feedback for the community. This is related to S3*, which has not yet been able to consolidate itself as an external auditing mechanism capable of responding to the issues identified.

S4 and S5 also show significant progress in the creation of adaptive processes and in the unification of the system’s teleology. Organisational intelligence is reflected in the collective work of the CE, while the community assembly reinforces the identity of the system under study. It is important to note that both systems require the formalisation of learning processes that ensure their continuity beyond the success of social enterprises in rural tourism.

Territories where water is a key attraction for tourism must recognise and respect their carrying capacity. In the case of Los Dinamos Park, these limits are closely linked to the quality and availability of water in the Magdalena River. This aligns with the literature on agile governance, which emphasises that water sustainability requires continuous cycles of learning, review and adaptation. The feedback loops identified in this study illustrate precisely this pathway towards more flexible and participatory governance, reinforcing the idea that SDG 6 is achieved through real organisational processes that promote water stewardship beginning at the local level [60].

The connection between the VSM and agile governance offers an important systemic contribution for understanding how complex human activity systems located in rural communities with a tourism vocation can maintain equilibrium despite the environmental, tourism and urban challenges present in cities that exceed their carrying capacity, such as Mexico City. This study provides empirical evidence that organisational viability in rural contexts does not depend on a formal structure, but on the community’s capacity to self-organise, learn and adapt collectively, conditions fostered by systems thinking.

This research also offers a significant contribution to the systems community by demonstrating that the VSM can be applied in real community settings and that agile governance is an effective means of translating sustainability principles into specific practices. Nevertheless, this work presents certain limitations arising from the limited number of participants, which could be strengthened by including a larger sample, particularly given the size of the rural community. For future research, it is recommended that the VSM be applied in other socio ecological systems, integrating agile governance as a tool for creating or reshaping organisational structures oriented towards sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.P.-M. and R.T.-P.; methodology and validation, R.T.-P. and I.B.-P.; formal analysis, Z.P.-M., R.T.-P. and I.B.-P.; investigation and resources, R.T.-P., Z.P.-M. and E.M.B.-R.; data acquisition, E.M.B.-R. and I.B.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.P.-M., R.T.-P. and E.M.B.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Instituto Politécnico Nacional, México, through the Transdisciplinary Project SIP 3420, granted by the Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado (SIP) and Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI), México.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the members of the La Magdalena Atlitic community for their openness, collaboration, and trust throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This semi structured interview guide (Table A1) was used to collect qualitative information during field visits, virtual sessions, and community workshops LMA. The questions were designed to explore organisational practices, coordination mechanisms, tourism dynamics, and water-related challenges within the rural community and its social enterprises.

Table A1.

Semi-structured interview guide used in the study

Table A1.

Semi-structured interview guide used in the study

| Section 1.Community context and tourism dynamics |

|

| Section 2. Organisationof social enterprises |

|

| Section 3. Coordinationand collective action |

|

| Section 4. Water Management Practices |

|

| Section 5. AdaptiveCapacity and Learning |

|

References

- Xess, S.; Bhargava, D.A. Carrying Capacity of Urban Transportation Networks: A Case Study of Designed Ideal City. In Proceedings of the 7th GoGreen Summit 2021, Manila, Philippines, 4–15 October 2021; Singh, S., Kianmehr, P., Aurifullah, M., Dragomirescu, M., Eds.; pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrino Figueroa, L.J. Dinámica Demográfica, Forma Urbana y Densidad de Población en Ciudades de México, 1990–2020: ¿urbanización Compacta o Dispersa? Estud. Demogr. Urbanos Col. Mex. 2024, 39, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONU Instantánea Del ODS 6 En México. Available online: https://sdg6data.org/es/country-or-area/Mexico#anchor_6.1.1 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- ONU Turismo Los Países Que Más Gastaron en Turismo en 2023. Available online: https://www.untourism.int/es/news/en-2023-con-la-reapertura-de-asia-y-el-pacifico-al-turismo-china-recupero-su-primera-posicion-en-la-clasificacion-de-paises-que-mas-gastan (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Gobierno de México Data México. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/ciudad-de-mexico-cx (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- SEPI. Pueblos Originarios de La Ciudad de México; SEPI: Miami, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Back, A.; Lundmark, L.; Zachrisson, A. Bridging (over) Tourism Geographies: Proposing a Systems Approach in Overtourism Research. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, I.G.B.R.; Suardhana, I.N.; Sutarya, I.G.; Krismawintari, N.P.D. Assessing the Impacts of Overtourism in Bali: Environmental, Socio-Cultural, and Economic Perspectives on Sustainable Tourism. Tour. Divers. Dyn. 2024, 1, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of Tourism Development upon Environmental Sustainability: A Suggested Framework for Sustainable Ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1976 Ed.); University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Economic Theory and Entrepreneurial History. In Explorations in Enterprise; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Say, J.B. Cours Complet d’Economique Politique Pratuque; HardPress: Miami, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, J.S. Principles of Political Economy; Longmans, Green and Co.: London, UK, 1848. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics; Mac-Millan: London, UK, 1890; pp. 1–627. [Google Scholar]

- Bate, A.F.; Pittaway, L.; Sàndor, D. Unveiling the Influence of National Culture on Entrepreneurship: Systematic Literature Review. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2025, 17, 875–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of “Social Entrepreneurship”; Scientific Research Publishing: Wuhan, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A. The Legitimacy of Social Entrepreneurship: Reflexive Isomorphism in a Pre–Paradigmatic Field. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 611–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.L.; Kothari, T.H.; Shea, M. Patterns of Meaning in the Social Entrepreneurship Literature: A Research Platform. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Martí, I. Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Source of Explanation, Prediction, and Delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Zhu, Z.; Trachung, B.; Golog, D.; Riley, M.; Zhi, L.; Li, L. Communities in Ecosystem Restoration: The Role of Inclusive Values and Local Elites’ Narrative Innovations. People Nat. 2024, 6, 1655–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, A.; Nasrolahi Vosta, L.; Ebrahimi, A.; Jalilvand, M.R. The Contributions of Social Entrepreneurship and Transformational Leadership to Performance. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2019, 39, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan Ayhan, Ç.; Cengiz Taşlı, T.; Özkök, F.; Tatlı, H. Land Use Suitability Analysis of Rural Tourism Activities: Yenice, Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; del Río-Rama, M.D.L.C.; Miranda-Salazar, S.P.; Tierra-Tierra, N.P. Strengthening of Community Tourism Enterprises as a Means of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Community Tourism Development in Chimborazo. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E.; González-Portillo, A. Limiting Rural Tourism: Local Agency and Community-Based Tourism in Andalusia (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2024, 104, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Wang, Y.; Dupre, K.; Putra, I.N.D.; Jin, X. Rural Tourism in Bali: Towards a Conflict-Based Tourism Resource Typology and Management. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 50, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Z. Cultural Heritage as Rural Economic Development: Batik Production amongst China’s Miao Population. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Knight, D.W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zi, M. Rural Tourism and Evolving Identities of Chinese Communities in Forested Areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Huang, K. How Does Social Entrepreneurship Achieve Sustainable Development Goals in Rural Tourism Destinations? The Role of Legitimacy and Social Capital. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 33, 1262–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaye, D.C. Climate Smart Agriculture Edu-Tourism: A Strategy to Sustain Grassroots Pro-Biodiversity Entrepreneurship in the Philippines. In Cultural Sustainable Tourism: A Selection of Research Papers from IEREK Conference on Cultural Sustainable Tourism (CST), Greece 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Tejeida-Padilla, R.; Pérez-Matamoros, Z.; Rodríguez-Escalona, M.L.; Hernández-Simón, L.M.; Badillo-Piña, I. Social Entrepreneurship and SDGs in Rural Tourism Communities: A Systemic Approach in Yecapixtla, Morelos, Mexico. World 2025, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, B. Rural Tourism in China: ‘Root-Seeking’ and Construction of National Identity. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabadzhyan, A.; Figini, P.; García, C.; González, M.M.; Lam-González, Y.E.; León, C.J. Climate Change, Coastal Tourism, and Impact Chains–a Literature Review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2233–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; ElDidi, H.; Masuda, Y.J.; Meinzen-Dick, R.S.; Swallow, K.A.; Ringler, C.; DeMello, N.; Aldous, A. Community-Based Conservation of Freshwater Resources: Learning from a Critical Review of the Literature and Case Studies. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2023, 36, 733–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Lyu, W.; Luo, W.; Yao, W. Analysis of Water Resource Management in Tourism in China Using a Coupling Degree Model. Water Policy 2021, 23, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Overtourism in Rural Areas. In Overtourism; Séraphin, H., Gladkikh, T., Vo Thanh, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 27–43. ISBN 978-3-030-42458-9. [Google Scholar]

- Phong, N.T.; Van Tien, H. Water Resource Management and Island Tourism Development: Insights from Phu Quoc, Kien Giang, Vietnam. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 17835–17856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.Z.; Tejeida, P.R.; Patiño, A.R. La Sistémica Transdisciplinar En La Gestión Sostenible Del Agua En Emprendimientos Sociales Turísticos de Comunidades Rurales de La Ciudad de México. In Avances en Nuevos Modelos del Turismo en México: Sustentabilidad, Cultura e Inclusión Como Ejes del Desarrollo Endógeno; Universidad Panamericana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; pp. 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delves, J.L.; Clark, V.R.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Barker, N.P.; Szarzynski, J.; Tondini, S.; Vidal, J.d.D.; Membretti, A. Scrutinising Multidimensional Challenges in the Maloti-Drakensberg (Lesotho/South Africa). Sustainability 2021, 13, 8511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens III, W.W. The Limits to Growth; Club of Rome: Winterthur, Switzerland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Tian, X.; Wang, H.; Tan, T. Exploration of the Coupling Coordination between Rural Tourism Development and Agricultural Eco-Efficiency in Islands: A Case Study of Hainan Island in China. J. Nat. Conserv. 2025, 84, 126822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.; Dubois, G.; Vergne, L.; Scott, D. Progress in Tourism Management Tourism and Water Use: Supply, Demand, and Security. An International Review. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDGF Objetivo 6: Agua Limpia y Sanamiento. Available online: https://www.sdgfund.org/es/objetivo-6-agua-limpia-y-saneamiento (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Popkova, E.G.; Bogoviz, A.V.; Lobova, S.V.; Delo, P.; Sergi, B.S.; Yankovskaya, V.V. Global Transitions towards Social Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development: A Unique Post-COVID-19 Perspective. Glob. Transit. 2023, 5, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruchten, P. Contextualizing Agile Software Development. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2013, 25, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, C.; Abrantes, B.F. Strategic Adaption (Capabilities) and the Responsiveness to COVID-19’s Business Environmental Threats. In Essentials on Dynamic Capabilities for a Contemporary World; Abrantes, B.F., Madsen, J.L., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-3-031-34814-3. [Google Scholar]

- Calame, P.; Talmant, A.; et Chaussées, I.D.P. L’État Au Cœur: Le Meccano de La Gouvernance; Desclée de Brouwer: Paris, France, 1997; ISBN 2220040542. [Google Scholar]

- Lehn, K. Corporate Governance and Corporate Agility. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. The Heart of the Enterprise; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Brain of the Firm; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. What Is Cybernetics? Kybernetes 2002, 31, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.M.; Walker, J.; Grover, K.; Vachkova, M.V. The Viability and Sustainability Approach to Support Organisational Resilience: Learning in a Recent Case Study in the Health Sector. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2023, 40, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, I.B. Dos Modelos de Gestión En La Historia Del Río Magdalena, Ciudad de México. El Repartimiento Colonial y La Junta de Aguas. Cuicuilco Rev. Cienc. Antropológicas 2018, 25, 111–138. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI México en Cifras. La Magdalena Contreras. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/#collapse-Resumen (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Almeida, L.O.; Jujnovsky, J. The Magdalena River Basin, an Example of a Fundamental Wetland for Mexico City. Rev. Ambiens Techné Et Sci. México 2023, 11, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Lozada, A.C.; Espinosa, A. Corporate Viability and Sustainability: A Case Study in a Mexican Corporation. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2022, 39, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A. Governance for Sustainability: Learning from VSM Practice. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.; Reficco, E.; Martínez, A.; Guzmán, D. A Methodology for Supporting Strategy Implementation Based on the VSM: A Case Study in a Latin-American Multi-National. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Usuga, L.; Camino, F.; Gomez-Casero, G.; Jara Alba, C.A. Rural Tourism Initiatives and Their Relationship to Collaborative Governance and Perceived Value: A Review of Recent Research and Trends. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 34, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.; Praskievicz, S.; McManamay, R.; Saxena, A.; Grimm, K.; Zegre, N.; Bair, L.; Ruddell, B.L.; Rushforth, R. Resilient Riverine Social–Ecological Systems: A New Paradigm to Meet Global Conservation Targets. WIREs Water 2024, 11, e1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoff, C.W.; Borgomeo, E.; Uhlenbrook, S. Rethinking Water for SDG 6. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 346–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).