Abstract

The recent rise in anti-globalization sentiment has renewed interest in how tariffs influence the location decisions of multinational enterprises (MNEs). However, these decisions have also been reshaped by ongoing geopolitical tensions-a factor that remains underexplored in the existing literature. In this study, we construct a panel dataset comprising 283,272 country-country-industry observations spanning the years 2009 to 2021. The data are drawn from the WITS, BvD, World Bank, and GDELT databases. Using fixed-effects regression, fixed-effects logit, and fixed-effects negative binomial models, we examine how MNEs respond to tariffs under varying levels of geopolitical risk. Our analysis yields three key insights. First, in contexts of low or no geopolitical risk, higher tariffs increase the likelihood of international investment by MNEs, consistent with the “tariff jumping” hypothesis. However, under high geopolitical risk, this effect disappears-regardless of tariff levels, MNEs are not more likely to invest abroad. Second, tariff increases can escalate low levels of geopolitical tension between home and host countries, further discouraging international investment. In contrast, high levels of geopolitical risk are not significantly correlated with tariff changes. Third, when low-level geopolitical tensions arise, MNEs may redirect investment to neighboring countries or major trading partners of the host country as a way to access its market indirectly.

1. Introduction

Events such as Brexit, the U.S.-China trade war, and the escalation of reciprocal tariff policies reflect a growing anti-globalization trend [1]. These developments have triggered a vigorous debate in both academic and policy circles over whether tariffs can effectively promote the reshoring of manufacturing activities [2]. Proponents argue that tariffs can incentivize tariff-jumping foreign direct investment (FDI), whereby firms invest directly in foreign markets to circumvent trade barriers [3,4]. In contrast, critics contend that higher tariffs increase the cost of imported intermediate goods, thereby reducing the effectiveness of tariffs in influencing the location decisions of multinational enterprises (MNEs) [5]. Yet discussions of MNE location choices that consider geopolitical risks remain incomplete. Without incorporating geopolitical risk (GPR) into the analysis, the true impact of tariffs on FDI decisions cannot be fully understood.

The intensification of geopolitical tensions has fundamentally reshaped the investment strategies of multinational enterprises (MNEs) [6]. Following the outbreak of the U.S.-China trade war, bilateral foreign direct investment (FDI) between the two countries declined sharply. According to data from the U.S. International Trade Administration, U.S. direct investment in China fell from USD 7.267 billion in 2019 to USD 5.131 billion in 2023. Meanwhile, China’s direct investment in the United States experienced an even greater decline, dropping from USD 3.618 billion in 2019 to a net outflow of USD −2.369 billion in 2023.

At the global level, FDI flows have also declined dramatically amid rising geopolitical risks [7]. In 2022, global FDI fell by 12%, and in 2023 it continued to decline by another 2%, reaching USD 1.3 trillion. Excluding short-term fluctuations in a few European economies, the overall global FDI contraction still exceeded 10%. This pattern stands in stark contrast to the surge in Japanese investment in the United States during the U.S.-Japan trade conflicts several decades ago.

Another salient feature of the current landscape is the rise of “friendshoring,” as firms seek to avoid geopolitical risks. Influenced by the U.S.-China trade war, countries and regions such as Mexico and ASEAN have increasingly emerged as key destinations for international investment seeking to mitigate geopolitical exposure, becoming critical alternative nodes in global supply chains. To circumvent tariff and non-tariff barriers, many multinational firms operating in China have adopted a “China + 1” strategy, relocating portions of their production to ASEAN and Latin America. Notably, these investment decisions often appear suboptimal when evaluated within a traditional cost-benefit framework [8]. Instead, they reflect strategic responses by firms to actual or anticipated geopolitical risks.

Traditional location choice theories place cost-benefit considerations at the core of MNEs’ decision-making. However, these theories overlook the essential heterogeneity in firms’ locational behavior under varying levels of geopolitical risk. When geopolitical risk is high, MNEs may find it difficult to enter host-country markets; under such circumstances, even strong locational advantages or tariff jumping incentives are unlikely to translate into tangible benefits for the firm. Traditional location choice theories place the cost-benefit considerations of multinational enterprises at the center of analysis. However, these theories largely overlook the fundamental differences in MNEs’ location decisions under varying levels of geopolitical risk. When geopolitical risks are high, multinational enterprises may face significant barriers to entering host-country markets. In such circumstances, even strong locational advantages or tariff jumping incentives are unlikely to translate into tangible business benefits. To address these limitations, this study incorporates tariffs and geopolitical risks into a unified theoretical framework to analyze how MNEs make location choices when facing different levels of geopolitical risk and tariff barriers. The structure of the paper is as follows. In the literature review, we summarize two strands of research: (1) studies examining the impact of tariffs on the location choices of MNEs, and (2) studies investigating the role of geopolitical risks in shaping these decisions. In the theoretical framework section, we develop an analytical model grounded in the Ownership-Location-Internalization (OLI) paradigm, extending it to explicitly incorporate tariff and geopolitical risk. We formalize this model mathematically to clarify the logic of location choices under these dual influences and derive the core assumptions of the paper. In the empirical analysis section, we test these hypotheses using panel data. Finally, the conclusion discusses the paper’s theoretical contributions and offers policy implications based on our findings.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Location Choice of Multinational Enterprises Under Tariff Shocks

Tariffs can incentivize multinational enterprises (MNEs) to shift from exporting to investing directly in foreign markets—a strategy commonly referred to as “tariff jumping” [3]. Blonigen (2002) [9] analyzing U.S. anti-dumping case data from 1980 to 1990, finds that the probability of MNEs investing in the United States increases significantly following anti-dumping accusations. He further argues that tariff jumping behavior is more prevalent among industrialized countries with extensive international experience. For example, Japan demonstrates a significantly stronger tariff jumping response than other countries in the sample, a pattern attributed to its mature global operational capacity.

However, bilateral tariffs do not necessarily stimulate investment solely between the two countries involved. When the cost of direct investment is prohibitively high, MNEs may instead choose to relocate production to a third country-typically one with lower trade barriers-commonly described as a “tariff haven.” In this way, the impact of tariff shocks can extend beyond the initiating countries, propagating through global production networks, particularly those embedded in global value chains (GVCs).

A well-documented case is the restructuring of the global clothing industry. The clothing sector represents a typical buyer-driven GVC, in which high-value-added activities such as branding, marketing, and retailing are concentrated in major consumer markets like Western Europe and the United States, while low-value-added labor-intensive production is carried out in developing labor-abundant countries. Changes in trade policy-such as tariffs and quotas-have repeatedly altered this global production configuration [10]. In the early 2000s, the removal of tariffs and quotas on Chinese exports spurred a significant rise in China’s clothing exports to the United States [11]. However, since 2016, in response to rising tariffs, many MNEs in the clothing industry have reoriented production toward South and Southeast Asian countries.

Amid the broader anti-globalization trend, the issue of tariff jumping has reemerged as a focal point in scholarly and policy discussions. Chahine et al. (2021) [12] find a significant increase in both the number and share of M&A transactions targeting U.S. firms following the election of Donald Trump—evidence consistent with firms strategically responding to anticipated protectionist policies.

Beyond direct investment incentives, tariffs can exert wider and more indirect effects through global value chains. Gereffi et al. (2021) [13] argue that tariff shocks may ripple across GVCs, prompting MNEs to diversify their sourcing strategies in order to mitigate heightened uncertainty. This adjustment process may benefit low- and middle-income countries by encouraging the geographic dispersion of production. In such volatile trade environments, MNEs must contend not only with rising tariffs and non-tariff barriers but also with frequent shifts in trade policy and related risks [14].

Recent rounds of reciprocal tariff negotiations-especially since 2025-have posed serious challenges to the operational stability of MNEs. In response, firms have adopted strategies to strengthen supply chain resilience and flexibility. One prominent example is the “China + 1” strategy, where firms maintain a presence in China while simultaneously establishing or expanding production in other Asian countries. This approach helps insulate operations from geopolitical shocks. MNEs also leverage subsidiaries in alternative locations to preserve supply chain continuity and sustain relationships with suppliers and customers.

In summary, while much of the existing literature has focused on the direct effects of tariffs on MNEs’ location choices-primarily through the lens of the tariff jumping hypothesis-indirect effects remain underexplored. Trade protectionism and tariff conflicts may not only influence where MNEs invest, but also reshape their broader location strategies, restructure global supply and value chains and reconfigure international production networks. Moreover, the uncertainty generated by tariff policy may produce consequences akin to those associated with geopolitical risks-an area that warrants greater attention in both theoretical and empirical research.

2.2. Geopolitical Risks and Location Choices of Multinational Enterprises

Geopolitical risks (GPR)—defined as political, economic, and environmental threats arising from conflict, violence, power struggles, and international tensions [15]—are widely recognized as a major barrier to international investment. According to the World Bank, developing economies attracted only $435 billion in FDI in 2023, the lowest level since 2005. High-income economies fared even worse, receiving just $336 billion-their lowest level since 1996. This global decline in investment activity is closely associated with rising geopolitical tensions [16]. GPR not only exposes multinational subsidiaries to financial losses but may also lead to the forced suspension or cancellation of international investment projects [17].

Traditional location theories typically explain these decisions through cost-benefit analyses, while global production network (GPN) theory emphasizes the importance of inter-firm relationships and network structures. However, both approaches largely neglect the role of geopolitical risk in shaping MNEs’ location strategies.

With the shift toward post-Fordist production, academic attention has increasingly focused on the role of GPNs and global value chains (GVCs) in structuring the spatial strategies of MNEs [13]. Location decisions are no longer seen as isolated decisions made by individual firms, but rather as embedded within broader transnational networks of production and exchange [18]. Lead firms—those that coordinate and govern production networks—often play a decisive role in determining where suppliers and partners locate their operations. Consequently, MNEs’ location strategies are shaped not only by market and cost factors but also by their relational position within the global production system.

Major external shocks-such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the U.S.-China trade war-have reshaped global production networks [19]. As a result, the criteria guiding MNEs’ location decisions have expanded beyond traditional cost-benefit considerations to incorporate network relationships and risk exposure. First, geopolitical risk is closely related to the increase in entry barriers for foreign investors. For example, following the onset of the U.S.-China trade war in 2018, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) significantly broadened its national security reviews, leading to the termination of numerous planned mergers and acquisitions involving Chinese firms. Second, geopolitical instability can diminish long-term profitability. After Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, the total value of assets held by U.S. subsidiaries in Russia declined by 23.1% relative to pre-crisis levels [20], a decline largely driven by the depreciation of the ruble [21].

Deseatnicov et al. (2023) [21] find that prior to 2014, German MNEs exhibited a relatively high tolerance for currency risk in Russia, often reinvesting profits and expanding operations during episodes of ruble depreciation. However, after the 2014 crisis, these firms adopted a more risk-averse approach, increasingly repatriating profits and reducing exposure in response to currency instability that eroded the real value of earnings.

It is also important to note that during periods of geopolitical conflict, MNEs face not only challenges from host governments but also rising scrutiny and political pressure from their home countries. Public opinion and national political sentiment can significantly constrain firms ‘strategic options abroad [22].

In summary, geopolitical risks can increase entry barriers and disrupt ongoing production and commercial activities for MNEs operating in affected host countries. This leads to two key outcomes: (a) a reduced likelihood of MNEs’ entry into high-risk markets, and (b) a tendency among MNEs to adopt a re-outsourcing strategies that shift investment toward countries with lower geopolitical risks.

Geopolitical conflicts vary in severity, ranging from low-level incidents—such as condemnations, diplomatic downgrades, rejections, threats, and protests—to high-level conflicts including territorial occupations and the use of conventional military forces. MNEs adjust their strategies according to the degree of geopolitical risk they face [23]. Therefore, we advocate for a more nuanced, severity-based classification of geopolitical risks.

Moreover, the interaction between tariffs and geopolitical risks warrants greater attention. Both may represent different manifestations of deteriorating international relations. In the context of major global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and the U.S.-China trade war, survival amid heightened uncertainty has become a central challenge for MNEs. Firms must now account for not only the benefits of tariff avoidance but also the broader instability and policy unpredictability associated with worsening bilateral relations.

Despite the growing importance of these issues, existing literature offers limited analysis of these complex dynamics linking geopolitical risks, trade policy, and firm strategy. We argue that geopolitical risks GPR must be explicitly integrated into the current frameworks of tariff jumping theory and theories of multinational enterprises’ location choice to better reflect the realities of the contemporary global economy.

3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

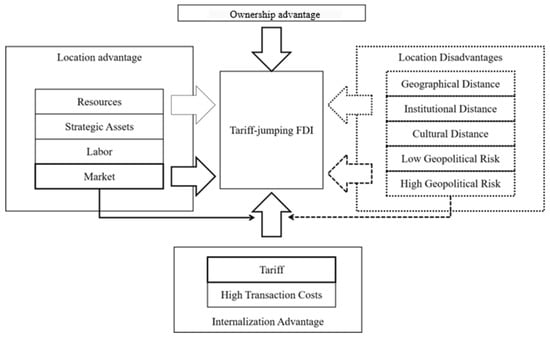

The OLI paradigm provides a robust analytical framework for understanding “tariff jumping” foreign direct investment (FDI) [24]. This study extends the “tariff jumping” theory by incorporating geopolitical risk factors, as illustrated in Figure 1. The FDI activities of multinational enterprises (MNEs) are shaped by ownership advantages, location advantages, and internalization advantages. From the perspective of ownership advantages, these advantages determine whether an MNE possesses the capability to engage in international production. Only firms endowed with ownership advantages can effectively establish themselves in host-country markets. Such advantages primarily stem from firm-level heterogeneity. Geopolitical risks at the national level may indirectly influence an MNE’s ownership advantages by altering the external environment in which these firm-specific assets generate value.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for multinational enterprises’ location choices considering both tariff and GPR.

From the perspective of internalization advantages, tariffs are closely related to the trade-off between exporting and undertaking international investment. When tariffs rise, the marginal cost of exporting increases, making international production a means of avoiding tariff-related expenses. Consequently, MNEs may shift from exporting to investing directly abroad. Transaction costs constitute another crucial component of internalization advantages, playing a decisive role in the choice between exporting and FDI. These costs are affected by factors such as the complexity of transactions and the degree to which knowledge can be codified. When market-based transaction costs become excessively high, firms tend to favor intra-firm transactions, rendering FDI more profitable than exports. Moreover, geopolitical risks may also affect MNEs’ internalization advantages. Under heightened geopolitical risk, MNEs are more likely to enter host-country markets through exports rather than through direct investment, as exports are more flexible than direct investment under geopolitical risks, and exports face fewer fixed costs.

From the perspective of location advantages, international investment can be broadly categorized into resource-seeking, market-seeking, efficiency-seeking, and strategic asset-seeking types [24]. Accordingly, cross-border investment is typically driven by the pursuit of host-country resources—such as natural endowments, market size, labor supply, strategic assets, and production efficiency. Among these, market-related advantages are particularly important in stimulating tariff-jumping FDI.

However, host countries may also exhibit location disadvantages. When factor costs are high or when substantial geographical, cultural, or institutional distance exists between the home and host countries, MNEs face additional costs in undertaking FDI. For instance, higher labor costs in the host country raise production expenses, greater geographical distance increases transportation costs, and institutional or cultural differences elevate transaction costs.

Geopolitical risk represents a critical dimension of location disadvantage, as elevated geopolitical tensions impose significant additional costs on international production. During periods of low-intensity geopolitical conflict—such as diplomatic condemnations, downgrades of relations, refusals, threats, or protests—MNEs may encounter public resistance within the host country. Such incidents can increase labor, sales, and transaction costs, thereby reducing the expected returns on FDI.

We also rigorously derived the hypothesis through mathematical models. The detailed derivation process can be found in the Supplementary File SA.

In this paper, we classify scenarios into nine categories based on varying tariff levels and degrees of geopolitical risk, which we discuss in detail below.

Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1:

Geopolitical risk exerts a negative impact on the international production of multinational enterprises (MNEs).

H2:

Tariffs have a positive effect on the international production of multinational enterprises (MNEs).

H2a:

When geopolitical risk is low, tariffs positively influence the international production of multinational enterprises.

H2b:

When geopolitical risk is high, tariffs do not have a significant effect on the international production of multinational enterprises.

- Scenario 1: No bilateral tariffs and no geopolitical risks.

When there are neither tariffs nor geopolitical risks, the external environment for multinational enterprises’ location decisions closely aligns with the neoclassical assumptions. Traditional location theory offers strong explanatory power in this scenario. MNEs choose locations based on the benefits provided by host country advantages and the costs associated with various dimensions of proximity. Considering internalization advantages, firms decide on entry modes such as exporting, outsourcing, joint ventures, franchising, direct investment, or strategic alliances. In this context, the absence of tariffs on intermediate goods removes incentives for tariff-jumping FDI. Examples include investments from mainland China to Hong Kong, investments within the European Union, and the United Kingdom’s investments in some former British colonies.

- Scenario 2: Low bilateral tariffs and no geopolitical risks.

In this scenario, MNEs’ international investment decisions are not disrupted by unexpected geopolitical risks. However, the incentive for tariff jumping remains low, and location choice continues to follow neoclassical logic. From the post-war period through the early 21st century, many cross-border investments among developed countries fit this category-for instance, investments between the United States and Europe.

- Scenario 3: High bilateral tariffs and no geopolitical risks.

This scenario presents the strongest motivation for tariff jumping by MNEs. When high tariff costs coincide with significant location advantages in the host country, direct investment offers substantial benefits over exporting. Japan’s direct investment in the United States during the Japan-U.S. trade war exemplifies this case. After World War II, the U.S. and Japan maintained a relatively stable and long-term diplomatic relationship, with few large-scale geopolitical conflicts. Before 1990, the geopolitical risk index between the two countries was only 3.424. Meanwhile, the trade conflict persisted for years, prompting some Japanese firms to upgrade their production toward higher value-added segments as part of tariff jumping strategies [13]. For example, in response to the Voluntary Export Restraints (VER) of the 1980s (a voluntary export restraint (VER) is a trade restriction on the quantity of a good that an exporting country is allowed to export to another country; this limit is self-imposed by the exporting country), Japanese automakers expanded investment in the U.S. and shifted toward producing luxury vehicles with higher added value.

- Scenario 4: No bilateral tariffs and low geopolitical risk.

Although geopolitical tensions have not escalated into violent conflict, and multinational enterprises (MNEs) have not yet faced extreme risks such as asset confiscation, nationalization, embargoes, or war, low geopolitical risk indicates that tensions between countries may escalate to high-level risks. This uncertainty can increase the production and operational costs for MNEs. Public resistance in host countries raises the marginal cost of international production. Moreover, if overseas subsidiaries are unable to operate normally, fixed assets such as factories and equipment may have to be sold at a loss-a situation especially harmful for capital-intensive firms.

- Scenario 5: Low bilateral tariffs and low geopolitical risks.

Under low tariff conditions, MNEs generally lack strong incentives to engage in tariff jumping. However, even low-level geopolitical risks can influence their location decisions. It is important to note that the combination of low tariffs and low geopolitical risks may signal an unstable geopolitical environment. In anticipation of possible tariff increases, MNEs may adjust their strategies in advance. For instance, the surge in foreign investment following Brexit was partly driven by firms’ concerns about future tariff uncertainties [25], despite relatively stable relations between the UK and EU countries. Using the synthetic control method, Thomas et al. (2020) [26] estimated that the Brexit referendum led to a 17% increase in the number of UK foreign investment transactions in the remaining 27 EU member states.

- Scenario 6: High bilateral tariffs and low geopolitical risk.

When facing high tariffs, MNEs have a stronger incentive to engage in tariff jumping. However, if investment barriers or geopolitical risks exist, firms may adopt strategies to reduce exposure. One common approach is to invest in nearby countries with more stable or friendly relations-these may be nearshore countries relative to both home and host nations-by establishing subsidiaries to manage uncertainty. This strategy offers two key benefits: (1) in the event of serious conflict between home and host countries, MNEs can shift part of their production to these alternative locations; (2) they can circumvent tariff barriers by routing products through subsidiaries in third countries.

- Scenario 7: No bilateral tariffs and high geopolitical risk.

In this scenario, the potential risks of international investment are high, but this does not mean that investment ceases entirely. Such investments often play an important role in maintaining and strengthening state relations. For example, China’s investment in Pakistan fits this case. Although China and Pakistan maintain relatively close diplomatic ties and have signed the China-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement (CPFTA) (the China-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement (CPFTA) is a free trade agreement (FTA) between the People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan that seeks to increase trade and strengthen the partnership between the two countries. Earlier agreements in the economic and trade relationship include the Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA) in 2003, the Early Harvest Program (EHP) in 2006, and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in 2015), under which Pakistan enjoys reduced or zero tariffs on certain Chinese imports. Pakistan’s geopolitical risks have remained high for an extended period. This continues to affect the operations of Chinese multinational enterprises in Pakistan. For instance, in 2018, the attack on the Chinese Consulate in Karachi caused the geopolitical risk index between the two countries to rise to 7.642. In 2024, the Chinese-funded Port Qasim Power Generation Company suffered a terrorist attack near Karachi’s Jinnah International Airport, pushing the geopolitical risk index to 7.720. Chinese investments in Pakistan are mainly carried out by state-owned enterprises, with notable projects including the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

- Scenario 8: Low bilateral tariffs and high geopolitical risks.

Here, the risks of international investment are very high, greatly reducing the likelihood that multinational enterprises will enter the local market. For example, anti-Chinese violence in Vietnam in 2014 raised the geopolitical risk index to 7.266. In the same year, China’s direct investment flow into Vietnam declined by 30.72%. Since 2019, as a result of the US-China. trade war, many Chinese firms have moved production to Vietnam. Due to concerns over geopolitical risks and incomplete local supply chains, Chinese multinationals generally relocate low-value-added activities such as assembly to Vietnam, while key intermediate products continue to be imported from mainland China [8].

- Scenario 9: High bilateral tariffs and high geopolitical risk.

Although the motivation to engage in tariff jumping is strong in this scenario, high geopolitical risks may nullify the tariff jumping hypothesis. Multinational enterprises seldom choose to invest in highly unstable host countries. For example, following the Iranian Revolution of 1978–1979 [27] and the imposition of U.S. sanctions starting in 1980, the Iranian automobile industry decoupled from Western multinationals. By 1980, automobile production in Iran had dropped by 73% compared to 1977 [28].

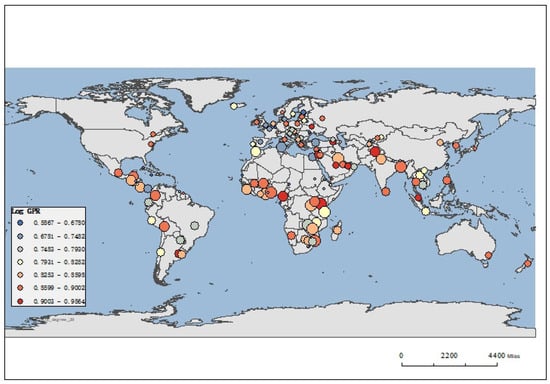

We present Figure 2 based on countries’ geopolitical risk (GPR) indices and tariff levels in 2021. In the figure, the size of each dot represents the magnitude of tariffs, while the color gradient reflects the level of geopolitical risk. As shown in Figure 2, high tariffs are often associated with moderate to high geopolitical risk. This pattern is particularly evident in regions such as East Africa and the Middle East, where both tariffs and geopolitical risk are elevated. In contrast, most European countries exhibit relatively low levels of both geopolitical risk and tariffs.

Figure 2.

Country blocks classified by two dimensions: tariffs and geopolitical risk.

4. Method and Data

4.1. Core Explanatory Variables

Explained Variable

The number of outbound investment and mergers and acquisitions OFDIijt is based on the BvD-ORBIS database and is the number of investing enterprises as the explained variable. OFDijkt represents the number of investments made by multinational enterprises in industry k in country i into subsidiaries in country j in year t. The BvD-ORBIS database encompasses basic information on billions of firms worldwide.

Geopolitical risk LnGPRijt: The core explanatory variables in this study are sourced from the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT), developed by Google. This database collects news reports from major mainstream media outlets in nearly 200 countries, covering more than 100 languages since 1979, and accounts for 98.4% of global news coverage. Its three primary news sources are the Associated Press, Agence France-Presse, and Xinhua News Agency. Using natural language processing (NLP) technology, GDELT extracts key information from news articles, including time, individuals, topics, event types, participants, locations, and media tone. The database is updated every 15 min. For English-language news, relevant information is extracted directly using NLP, while non-English news is first translated into English before processing.

Geopolitical risk index in this study is constructed as follows: A GDELT project is created in Google BigQuery, Google Cloud Platform’s big data query system. SQL queries are used to filter news reports that mention both China and the host country, with duplicate reports removed based on the news source URL. GDELT employs the Conflict and Mediation Event Observations (CAMEO) event and actor codebook. Following the method of Federo and Bustamante et al. (2022) [29], we classify event types into 20 categories based on the CAMEO codes provided by GDELT, and assign corresponding Goldstein scores ranging from −10 to 10 (see Supplementary File SB for full correspondence). Conflict events have Goldstein scores below zero, while cooperation events have scores above zero. To measure geopolitical risk, this paper uses conflict events with Goldstein scores less than zero occurring between the home country of firm i (China) and host country j in year t as a proxy. The absolute value of the score indicates the severity of geopolitical risk faced by multinational enterprises in the host country. Since our panel data is annual, we sum the product of the reporting frequency and corresponding Goldstein scores for all relevant events from 1 January to 31 December of year t, then take the natural logarithm of this sum. A higher absolute Goldstein score and a greater number of unique reports indicate a higher geopolitical risk index between China and the host country.

Tariff, Tariffijkt, we calculated the country-country-industry tariff data based on the WITS database. We weighted the tariff data in the WITS database to obtain the simple mean data, and merged the tariff data of different commodities into 26 standard industries. The corresponding relationship refers to the corresponding method in the UNCTAD database. Finally, we can obtain the average export tariff of industry k in country i to country j.

4.2. Control Variables

Total output, denoted as Exportijkt, is derived from the EORA26 database. It represents the total export value from industry k in country i to country j used to satisfy the intermediate and final product demand in country j. The natural logarithm of this value is taken to construct the control variable Exportijkt.

Labor advantage, denoted as Laborit, follows Dunning(2001) [24] classification of multinational enterprises’ motivations for overseas investment, which include natural resource seeking, labor seeking, market seeking, efficiency seeking, and strategic asset seeking. To control for the labor impact on multinational enterprises’ investment, we use the total labor force of country i in year t, sourced from the World Bank. Following the World Bank’s definition, the total labor force includes all individuals aged 15 and above who meet the International Labour Organization’s criteria for the economically active population, i.e., those engaged in producing goods and services. The natural logarithm of labor force is used as the control variable.

Market advantage, denoted as PrGDPit, controls for the effect of market size on multinational enterprises’ location choice. We take the natural logarithm of per capita GDP (current US dollars) of country i in year t plus one, using data from the World Bank.

Resource advantage, denoted as Resourceit, is proxied by the total natural resource rent as a percentage of GDP for country i in year t, with data obtained from the World Bank. According to the World Bank, total natural resource rent includes the sum of rents from oil, natural gas, coal (hard and soft), minerals, and forests.

4.3. Empirical Model

The empirical model is based on the formula in the theoretical model (see Supplementary File SA).

The profit of a multinational enterprise in industry k from country i operating in country j is given by

Therefore, we can conclude that the probability of multinational enterprises in industry k of country i entering the market of country j is negatively correlated with geopolitical risk.

It can be seen that:

When multinational enterprises enter the host country market, changes in their international production output are proportional to changes in exports and changes in tariffs .

From this, we conclude that:

Among them, represents the number of companies invested in country j by multinational enterprises in industry k of country i in year t. represents the total exports of multinational enterprises in industry k of country i to country j in year t. represents the average tariff of exports from industry k of country i to country j, and represents the geopolitical risk index of country i and country j in year t. represents the fixed effect of home country-host country-industry. represents the control variable. Since the addition of time fixed effects in the panel logit model and the panel negative binomial model may increase the regression bias, it is not included in our model . First, we regressed the investment quantity. In order to reduce the heteroskedasticity problem, we logarithmized the explained variables and performed fixed-effect regression. The regression equation is as follows:

Since the dependent variable is count data, a negative binomial model or a Poisson model is required. However, the mean of the dependent variable is much smaller than the variance, which does not conform to the Poisson distribution assumption. Therefore, we use a panel negative binomial model for robustness testing.

The panel negative binomial model is set as:

Among them, represents all explanatory variables, including core explanatory variables , , and control variables, and represents the overdispersion parameter.

Since there are too many zero values in the explained variable, accounting for 98.87% of the whole sample, the dependent variable after logarithmization still deviates seriously from the normal distribution and may have zero inflation problem. Models that help solve the zero-inflation problem include the zero-inflated negative binomial model and the fixed effect logit model. Since the zero-inflated negative binomial model cannot control the fixed effect, we use the fixed effect logit model for robustness test. The panel Logit model is set as:

5. Results

We coded all country1-country2-industry groups and, after excluding groups with severe data deficiencies, obtained a final sample of 283,272 groups comprising panel data from 2009 to 2021. Observations where country1 and country2 were identical were excluded.

Due to excessive locational disadvantages arising from large geographical, cultural, and institutional distances, or due to limited locational advantages, a substantial number of country1-country2-industry groups are structurally unable to engage in international direct investment. The zero values corresponding to such cases are thus structural zeros, rather than random. In contrast, some pairs may have the potential for FDI but did not engage in cross-border investment in particular years; these are random observational zeros. The coexistence of both structural and random zeros results in a severe zero-inflation problem in the dependent variable.

To address this issue, we employed three complementary empirical strategies: the zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) model, the fixed-effects negative binomial model, and the two-part model. Each of these approaches has distinct advantages and limitations when dealing with zero-inflated dependent variables.

The two-part model and the fixed-effects negative binomial regression model allow for the inclusion of fixed effects; however, the fixed-effects negative binomial model cannot explicitly correct for zero inflation. The two-part model, on the other hand, assumes independence between the two stages—investment occurrence and investment magnitude—thus potentially neglecting the correlation between these processes. In contrast, the ZINB model effectively accounts for zero inflation but does not allow for fixed effects, making it difficult to control for time-invariant unobserved bilateral heterogeneity. For panel data involving -country pairs and time dimensions, this limitation may lead to omitted variable bias.

Therefore, we report results from all three models to ensure cross-validation and robustness. The empirical results are consistent with our theoretical expectations: the number of multinational enterprises is positively associated with export volume and tariff levels, but negatively associated with geopolitical risk. This finding suggests that while avoiding trade barriers may encourage multinational enterprises to undertake foreign investment, geopolitical risks pose significant obstacles. These results provide strong support for Hypothesis H1.

The two-part model consists of two stages. The first stage determines whether international investment occurs, while the second stage determines the number of FDI firms conditional on investment occurrence. The first stage employs a fixed-effects logit model, and the second stage applies a fixed-effects linear regression model (XTREG). The first stage can only capture the probability of FDI occurrence, but not the intensity of FDI. To address potential heteroskedasticity, the dependent variable in the second-stage regression is transformed using the natural logarithm of outward FDI, denoted as lnOFDIijkt.

In the first-stage model, the dependent variable of the fixed-effects logit regression is a binary indicator derived from OFDIijkt: It equals 0 if OFDIijkt = 0, and 1 otherwise. We performed Hausman tests for the fixed-effects logit, fixed-effects linear, and fixed-effects negative binomial models to compare fixed- and random-effects specifications (Table 1). The results consistently support the fixed-effects specification. Accordingly, Table 1 reports the results of the regression analyses. The findings indicate that tariffs may promote foreign direct investment (FDI) by multinational enterprises (MNEs), whereas geopolitical risk tends to hinder it. These results are statistically significant and robust across the two-part model, zero-inflated negative binomial regression, and fixed-effects negative binomial regression models. The main regression results support both Hypothesis H1 and Hypothesis H2.

Table 1.

The impact of geopolitical risk on multinational enterprises’ international direct investment: baseline regression model.

According to the two-part model, a 1% increase in tariffs between specific industries and country pairs raises the probability that MNEs will enter the host country by 2.4% (Table 2). Once MNEs have entered the host country, a 1% increase in tariffs leads to a 2.2% increase in the number of subsidiaries established. From the perspective of geopolitical risk, a 1% increase in the geopolitical risk index significantly reduces the probability of MNEs entering a host country by 15.51%. After entry, a 1% increase in geopolitical risk results in a modest 1.1% decline in the number of subsidiaries established by MNEs.

Table 2.

Mediation test of the effect of tariffs on international direct investment through geopolitical risk.

To test the mediating effect of tariffs, we use the geopolitical risk (GPR) index as the dependent variable and tariffs as the key explanatory variable in a panel logit model. Given the clear heterogeneity of geopolitical conflict events, we distinguish between low-level and high-level conflicts. Low-level events-such as condemnation, reduction in diplomatic relations, rejection, threats, and protests-are often significantly associated with tariffs between two countries. For example, a sudden tariff increase may trigger protests or condemnation. Tariffs can also be used as a tool to reduce diplomatic relations or exert mutual threats. In contrast, high-level conflict events-such as territorial occupation and the use of conventional military force-show a relatively weak correlation with tariffs, as tariff disputes rarely escalate to such severe conflicts.

According to the Geopolitical Risk (GPR) Index, events involving territorial occupation or the use of military force have Goldstein scores greater than or equal to 7, while lower-level conflict events such as diplomatic condemnations or downgrading of relations fall within the range of 4 to 7. Tariffs and non-tariff barriers are also typically categorized as manifestations of low-level geopolitical risks. Accordingly, we classify events with a GPR score above 7 as high-level geopolitical risks (GPRH), those with scores between 4 and 7 as low-level geopolitical risks (GPRL), and those with scores below 3 as indicating the absence of geopolitical risk.

Specifically, when the Goldstein score of the GPR index between country i and country j in year t is greater than or equal to 7, we set GPRH = 1, and GPRH = 0 otherwise. When the score is greater than 4 and less than or equal to 7, we set GPRL = 1, and GPRL = 0 otherwise. To avoid overlapping classifications, we exclude country pairs experiencing high-risk events from the GPRL sample and those experiencing low-risk events from the GPRH sample.

Our results indicate that both GPRH and GPRL exert a negative effect on foreign direct investment (FDI). This finding suggests that high-level geopolitical risks—such as wars and embargoes—and low-level geopolitical risks—such as regulatory changes, sanctions, and export controls—significantly reduce multinational enterprises’ direct investment. Mediation analysis further reveals that tariffs may increase low-level geopolitical risks, thereby reducing the likelihood of multinational firms investing in host countries. However, tariffs are not significantly associated with high-level geopolitical risks. The empirical results reported in Columns (2) and (3) of Table 2 show a significant positive relationship between tariffs and GPRL, whereas the relationship between tariffs and GPRH is statistically insignificant.

We classify the sample into three groups based on the geopolitical risk index between countries (Table 3). Countries that experienced high-level geopolitical risk events (GPRH) during the study period are assigned to the GPRH group; those that experienced low-level geopolitical risk events (GPRL) are assigned to the GPRL group; and countries with no recorded geopolitical risk events during the period form the GPRN group. The results indicate that in both the GPRL and GPRN groups, increases in tariffs significantly promote FDI. These findings are consistent and robust across the panel fixed-effects regression model, panel logit model, and panel negative binomial model. However, in the GPRH group, tariff increases have a limited effect on promoting FDI, and in the panel logit model, tariffs do not significantly affect FDI. These results support hypothesis H2a and confirm hypothesis H2b.

Table 3.

Heterogeneity regression models based on groups classified by geopolitical risk.

We investigate the spillover effects of geopolitical risks within the global production network using the variable GPRH_EXijkt. GPRH_EXijkt equals 1 if the home country i has high-level geopolitical risks with the largest import partner of host country j in year t, and 0 otherwise (Table 4). GPRH_EXijkt is similarly defined for low-level geopolitical risks. The findings indicate that geopolitical risks encourage investment in these key import source countries.

Table 4.

The impact of geopolitical risk on multinational enterprises’ international direct investment: spillover effect model.

Since the geopolitical risk index based on media-text data may not fully capture the geopolitical risks perceived by firms, we conducted a robustness check by replacing the original index with an alternative measure developed in the latest research by Caldara and Iacoviello (2023) [30]. The geopolitical risk index constructed by Caldara and Iacoviello (2023) [30] is particularly well-suited to analyzing corporate investment decisions, as it supplements aggregate indicators with measures of geopolitical risk observed at the industry and firm levels (Table 5). However, this index also presents certain limitations in our context, as it captures country-specific rather than bilateral geopolitical risks. Therefore, in our robustness analysis, we use this index to measure the host country’s geopolitical risk. The results of this robustness test show that, after replacing the explanatory variable, the estimated coefficients remain statistically significant and consistent with the baseline model. These findings further support Hypotheses H1 and H2.

Table 5.

Endogeneity test and robustness test.

Because both tariffs and geopolitical risk may be simultaneously influenced by unobserved factors, and international investment may, in turn, affect geopolitical risk (reverse causality), we also address potential endogeneity concerns by employing a two-stage least squares (2SLS) panel regression using the occurrence of high-level geopolitical conflict events as an instrumental variable (IV). The choice of this IV is justified by two conditions:

(1) Relevance: High-level geopolitical conflict events are strongly correlated with the geopolitical risk index-empirically, the correlation coefficient exceeds 0.85. (2) Exogeneity: Such events (e.g., wars, embargoes, or large-scale violent conflicts) are exogenous to firms’ FDI decisions. While they directly affect cross-border investment by altering the geopolitical environment, the reverse effect of FDI on such conflicts is negligible. Furthermore, as shown in Table 2, both empirical results and logical reasoning suggest that low-level geopolitical risks may interact with tariffs—for example, tariffs can both provoke opposition and serve as a retaliatory tool in response to diplomatic deterioration. However, since World War II, tariff disputes have rarely escalated into violent conflict, a pattern supported by the empirical evidence in Table 2.

Based on these considerations, we employ high-level geopolitical conflict events as the instrumental variable in the 2SLS panel estimation. The results remain robust and continue to support Hypotheses H1 and H2. Moreover, the Hausman test confirms that the 2SLS panel model performs better than the fixed-effects model, further validating the robustness of our findings.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

We constructed a panel dataset comprising 283,272 country-to-country-industry groups over the period 2009–2021, based on data from the WITS database, BvD database, World Bank database, and GDELT database. The results from fixed effects regression, fixed effects logit, and fixed effects negative binomial models show that:

- (1)

- International investment is closely related to exports, tariffs, and geopolitical risks. Tariffs have a positive effect on international investment, while geopolitical risks exert a negative effect.

- (2)

- When there are no geopolitical risks or only low-level geopolitical risks between the home and host countries, the empirical evidence supports the tariff jumping hypothesis: tariffs significantly increase the likelihood of multinational enterprises investing in the host country. However, when high-level geopolitical risks are present, the tariff jumping hypothesis no longer holds, as tariffs show no significant effect on the probability of international investment.

- (3)

- Mediation analysis indicates that tariffs may increase low-level geopolitical risks, which further reduce the probability of multinational enterprises investing abroad. There is no significant relationship between tariffs and high-level geopolitical risks, likely because tariff disputes rarely escalate into wars, property confiscations, or other severe conflicts.

- (4)

- Low-level geopolitical risks produce spillover effects. When such risks occur between the home and host countries, multinational enterprises tend to increase investment in countries bordering the host country or in the host country’s largest importers. In contrast, high-level geopolitical risks do not generate such spillovers.

Against the backdrop of major geopolitical conflicts such as the U.S.-China trade war and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the guiding logic of location decisions has evolved from a simple cost-benefit framework to a more complex cost-benefit relationship-risk framework. Under heightened geopolitical risks, multinational enterprises (MNEs) have shifted their investment strategies from nearshoring to friendshoring. For example, following the COVID-19 pandemic and the onset of the U.S.-China trade war, many European and American MNEs investing in China adopted a “China + 1” strategy—establishing subsidiaries in neighboring countries that maintain friendly relations with their home countries to hedge against uncertainties. When U.S.-China relations remain tense or supply chain risks emerge, firms can rely on friendshoring to sustain their production networks.

Such strategies cannot be adequately explained by traditional location theories and reveal the limitations of the tariff jumping hypothesis. In fact, despite the prolonged trade war, Chinese investment in the United States declined sharply between 2019 and 2021, likely due to escalating geopolitical risks and uncertainties. Therefore, we argue that geopolitical risk should be incorporated into the theoretical framework of tariff jumping to better capture how MNEs adjust their location choices under varying levels of geopolitical risk (Helpman and Elhanan2006) [31] (Adarkwah, Gilbert Kofi et al., 2024) [32].

From a policy perspective, this study cautions against imposing high tariffs without accounting for geopolitical risks, as such measures do not necessarily lead to reshoring of manufacturing activities. The locational decisions of multinational firms depend not only on production costs, geography, cultural and institutional distance, but also on geopolitical risk. On one hand, rising geopolitical risk has caused a sharp decline in international investment flows, driving globalization toward regionalization and challenging the resilience of supply chains during the restructuring of global value chains. On the other hand, some “pipeline countries” can benefit from this restructuring process. As recipients of friendshoring, certain developing economies have gained significant opportunities to attract foreign investment.

Our findings suggest that when the benefits of tariff jumping are insufficient to offset the additional costs of international investment, firms are likely to avoid overseas expansion. Moreover, raising tariffs may trigger low-level geopolitical conflicts—such as condemnations, diplomatic deterioration, threats, or protests—further reducing the likelihood of investment. More importantly, under high-level geopolitical risks—such as property expropriation, war, embargoes, or other violent conflicts—the tariff jumping hypothesis no longer holds, as firms are unable to bear the prohibitive costs regardless of tariff levels.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems13121086/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.G. and Y.L.; methodology, Z.G. and R.Y.; software, Z.G. and Y.L.; validation, Z.G., Y.L. and R.Y.; formal analysis, Z.G. and R.Y.; investigation, Z.G., R.Y. and Y.L.; data curation, Z.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.G., R.Y. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.G. and Y.L.; visualization, Z.G. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Z.G. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China: 42271180, and the APC was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided as required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

References

- Luo, Y. Illusions of Techno-Nationalism. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 53, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, C.; Mattoo, A.; Mulabdic, A.; Ruta, M. Is US Trade Policy Reshaping Global Supply Chains? J. Int. Econ. 2024, 152, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, M. How Do Technical Barriers to Trade Affect Foreign Direct Investment? Tariff Jumping Versus Regulation Haven Hypotheses. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2020, 52, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z. Production Line Location Strategy for Foreign Manufacturer When Selling in a Market Lag behind in Manufacturing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 198, 110678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, K.; Tsubota, K. Location Choice in Low-Income Countries: Evidence from Japanese Investments in East Asia. J. Asian Econ. 2014, 33, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, J.H.; Kwak, J.; Park, H.-K. ESG as a Nonmarket Strategy to Cope with Geopolitical Tension: Empirical Evidence from Multinationals’ ESG Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2025, 46, 693–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, G.; Gräb, J. Global Financial Market Impact of the Announcement of the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme. J. Financ. Stab. 2016, 26, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chan, D.Y.-T. Geopolitical Risks of Strategic Decoupling and Recoupling in the Mobile Phone Production Shift from China to Vietnam: Evidence from the Sino-US Trade War and COVID-19 Pandemic. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 158, 103028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonigen, B.A. Tariff-Jumping Antidumping Duties. J. Int. Econ. 2002, 57, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Shah, J. A Comparative Analysis of Greening Policies across Supply Chain Structures. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernathy, F.H.; Volpe, A.; Weil, D. The Future of the Apparel and Textile Industries: Prospects and Choices for Public and Private Actors. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 2207–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, S.; Dbouk, W.; El-Helaly, M. M&As and Political Uncertainty: Evidence from the 2016 US Presidential Election. J. Financ. Stab. 2021, 54, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G. Economic Upgrading in Global Value Chains. In Handbook on Global Value Chains; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, H.W. Troubling Economic Geography: New Directions in the Post-Pandemic World. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2023, 48, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Banna, H.; Alam, A.W.; Bhuiyan, M.B.U.; Mokhtar, N.B. Climate Change and Geopolitical Conflicts: The Role of ESG Readiness. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Pham, B.T.; Sala, H. Being an Emerging Economy: To What Extent Do Geopolitical Risks Hamper Technology and FDI Inflows? Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 728–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, V.; Vertinsky, I.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D. Decoupling in International Business: The ‘New’ Vulnerability of Globalization and MNEs’ Response Strategies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 1562–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Dicken, P.; Hess, M.; Coe, N.; Yeung, H.W.-C. Global Production Networks and the Analysis of Economic Development. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2002, 9, 436–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarski, L.; Roscoe, S.; Blome, C.; Schleper, M.C. Geopolitical Disruptions in Global Supply Chains: A State-of-the-Art Literature Review. Prod. Plan. Control. 2025, 36, 536–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenett, S.J.; Pisani, N. Geopolitics, Conflict, and Decoupling: Evidence of Western Divestment from Russia During 2022. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2023, 6, 511–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deseatnicov, I.; Klochko, O. Currency Risk and the Dynamics of German Investors Entry and Exit in Russia. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2023, 55, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holburn, G.L.; Zelner, B.A. Political Capabilities, Policy Risk, and International Investment Strategy: Evidence from the Global Electric Power Generation Industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1290–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, N.M.; Hess, M.; Yeungt, H.W.; Dicken, P.; Henderson, J. ‘Globalizing’ Regional Development: A Global Production Networks Perspective. In Economy; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J.H. The Eclectic (OLI) Paradigm of International Production: Past, Present and Future. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2001, 8, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradlou, H.; Reefke, H.; Skipworth, H.; Roscoe, S. Geopolitical Disruptions and the Manufacturing Location Decision in Multinational Company Supply Chains: A Delphi Study on Brexit. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 102–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breinlich, H.; Leromain, E.; Novy, D.; Sampson, T. Voting with their money: Brexit and outward investment by UK firms. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 124, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuzegar, J. The Islamic Republic of Iran: Reflections on an Emerging Economy; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlínek, P. Geopolitical Decoupling in Global Production Networks. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 100, 138–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federo, R.; Bustamante, X. The Ties That Bind Global Governance: Using Media-Reported Events to Disentangle the Global Interorganizational Network in a Global Pandemic. Soc. Netw. 2022, 70, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldara, D.; Iacoviello, M. Measuring Geopolitical Risk. Am. Econ. Rev. 2022, 112, 1194–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helpman, E. Trade, FDI, and the Organization of Firms. J. Econ. Lit. 2006, 44, 589–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarkwah, G.K.; Dorobantu, S.; Sabel, C.A.; Zilja, F. Geopolitical volatility and subsidiary investments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2024, 45, 2275–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).