Abstract

Scandium (Sc)-doped aluminum nitride (AlN) thin films are critical for high-frequency, high-power surface acoustic wave (SAW) devices. A composite Sc doping strategy for AlN thin films is proposed, which combines magnetron sputtering pre-doping with post-doping via ion implantation to achieve gradient doping and tailor microstructural characteristics. The crystal structure, surface composition, and microstructural defects of the films were characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Results indicate that the Sc content in pre-doped ScAlN films was optimized from below 10 at.% to above 30 at.%, while the films maintained a stable (002) preferred orientation. XPS analysis confirmed the formation of Sc-N bonds, and EDS mapping revealed a gradient distribution of Sc within the subsurface region, extending to a depth of approximately 200 nm. High-resolution TEM revealed localized lattice distortions and surface amorphization induced by ion implantation. This work demonstrates the feasibility of ion implantation as a supplementary doping technique, offering theoretical insights for developing AlN films with high Sc doping concentrations and structural stability. These findings hold significant potential for optimizing the performance of high-frequency, high-power SAW devices.

1. Introduction

Aluminum nitride (AlN), a III-V group wide-bandgap semiconductor material, exhibits considerable application potential in surface acoustic wave (SAW) devices due to its excellent piezoelectric properties, high thermal conductivity, and chemical stability [1,2,3]. In heterostructures with diamond substrates, the high acoustic velocity and thermal conductivity of diamond are combined with piezoelectric AlN thin films. This integration can significantly enhance the high-frequency response and reliability of devices, offering considerable potential for 5G communication and high-frequency sensors [4]. However, the piezoelectric performance of AlN often requires enhancement through doping [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Among various dopants, Scandium (Sc) has demonstrated particularly notable improvements, making it a research focus [11,12,13,14].

Current methods for incorporating Sc into AlN thin films typically involve introducing a Sc target [12] or using Al-Sc alloy targets [13] during magnetron sputtering. Although Sc-doped AlN (ScAlN) enhances device performance by increasing the piezoelectric coefficient, its application is limited by structural instability. When the Sc atomic ratio exceeds 43 at.% among metal atoms (i.e., Sc0.43Al0.57N), a phase transformation from the wurtzite structure to the zinc-blende phase occurs, degrading the (002) preferred orientation and diminishing piezoelectric properties [14]. This limitation restricts further enhancement of piezoelectric performance in ScAlN films. An alternative approach to improve the piezoelectric properties of AlN films is ion implantation, which can induce tensile strain along the c-axis direction in the wurtzite AlN lattice, thereby enhancing piezoelectric polarization [15,16,17,18].

This study employs a combined strategy of pre-doping via magnetron sputtering and post-doping via Sc ion implantation to achieve Sc doping levels beyond those attainable by conventional sputtering alone. The effects of ion implantation on film surface composition and microstructure of the films are systematically investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This research provides fundamental insights for further enhancing the performance of high-frequency, high-power SAW devices.

2. Experimental

AlN thin films were deposited using a magnetron sputtering system (MSP-300B). High-purity Al (99.999%), Sc (99.99%), and Titanium (Ti, 99.999%) targets with a diameter of 80 mm were employed. The process gases were argon (Ar, 99.999%) and nitrogen (N2, 99.999%). The substrates consisted of single-side polished polycrystalline diamond with a root mean square roughness of approximately 2.3 nm (20 μm × 20 μm). Prior to deposition, the substrates were ultrasonically cleaned in acetone, anhydrous ethanol, and deionized water for 10 min each. An ion implanter (CHZ-2600) was used for Sc ion implantation.

After cleaning, the diamond substrates were loaded into the sputtering chamber, which was evacuated and heated. When the chamber pressure decreased below 5 × 10−5 Pa, Ar gas was introduced. The Ti target was sputtered for 15 min to remove oxygen in chamber, followed by 10 min of pre-sputtering of the Al and Sc targets to eliminate surface contaminants. N2 gas was then introduced to initiate AlN film deposition under the following conditions (Table 1): Al target power of 450 W, Sc target power of 175 W, Ar/N2 gas flow ratio of 21:6, sputtering pressure of 0.4 Pa, and substrate temperature of 500 °C. After deposition, the AlN/diamond or ScAlN/diamond samples were naturally cooled in the chamber. Subsequent Sc ion implantation was conducted with an acceleration voltage of 30 keV and a flux of 5 × 1016 cm−2, followed by annealing at 800 °C for 1 h to alleviate implantation-induced damage.

Table 1.

Sputtering parameters of AlN and pre-doped ScAlN thin films deposited on diamond substrates.

The thickness of the deposited (Sc)AlN film measured by a step profiler (Bruker DektakXT, Karlsruhe, Germany) was approximately 1 μm. The crystalline orientation of the AlN films was characterized using X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D2 Phaser, Karlsruhe, Germany). Elemental composition and chemical states of the Sc-doped AlN films were analyzed by an XPS instrument (Thermo Scientific K-Alpha, East Grinstead, UK). The microstructure and composition of focused ion beam (FIB)-prepared cross-sectional samples were investigated using a TEM system (FEI Tecnai G2 F30, Hillsboro, OR, USA). And EDS mapping with an acceleration voltage of 20 keV was employed to further determine the gradient distribution of Sc doping.

3. Results and Discussion

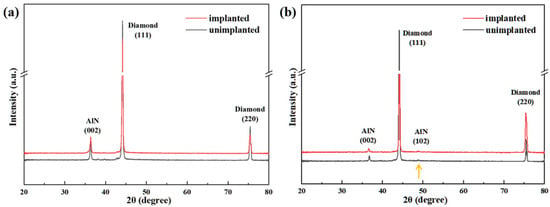

Figure 1 presents the XRD patterns of AlN and pre-doped ScAlN thin films before and after Sc implantation. Both films retained a (002) preferred orientation after implantation, with no detectable diffraction peaks corresponding to secondary phases such as zinc-blende AlN or Sc-based compounds. The position of the AlN (002) peak remained unchanged, suggesting that ion implantation under the current parameters did not induce significant lattice expansion/contraction or phase transitions in the underlying wurtzite structure. A very weak diffraction peak, possibly corresponding to the AlN (102) plane, was observed in the Sc-implanted ScAlN sample (indicated by the arrow in Figure 1b). This suggests minimal alteration of the overall films. Ion implantation primarily modifies a thin surface layer. However, due to the deep penetration depth of X-rays, the XRD patterns are dominated by strong diffraction from the diamond substrate and the bulk of the film. Since XRD signals represent a volume-averaged structural information, the technique is relatively insensitive to localized structural changes in shallow surface regions [19,20]. Therefore, complementary analysis using surface-sensitive techniques is necessary.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of (a) AlN thin films and (b) pre-doped ScAlN thin films before and after Sc implantation. Arrows indicate very weak peaks that may correspond to the (102) plane of AlN.

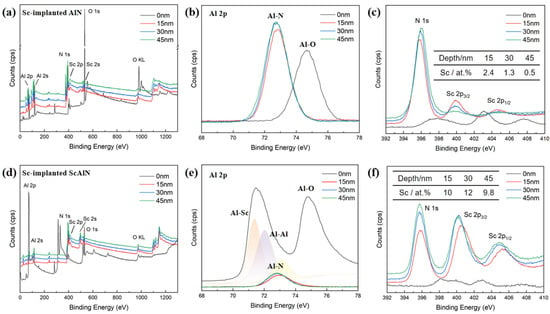

To characterize the chemical state and depth distribution of the doped Sc, layer-by-layer XPS analysis was performed with incremental argon ion sputtering. Etching was conducted at 15 nm intervals, as calibrated using a sputtering rate of approximately 0.1 nm/s determined from a reference AlN sample. It should be noted that these depth measurements are estimates, as sputtering rates may vary across different materials and with composition. Three successive etching cycles were performed on both Sc-implanted AlN and ScAlN thin films, with full survey scans and high-resolution narrow scans of the Al 2p, Sc 2p, and N 1s core levels, acquired at each stage as shown in Figure 2. All XPS spectra were calibrated using a standard C 1s peak at 284.8 eV and N 1s peak at 396.0 eV. Firstly, a prominent O 1s peak was observed on the non-etched surface, which significantly attenuated after sputtering (Figure 2a,d). This indicates the presence of a surface oxide layer from ambient oxygen adsorption, contrasting with the substantially lower oxygen content in the bulk material. Compared to the Sc-implanted AlN sample, a systematic shift toward lower binding energy existed in ScAlN film. This was probably due to changes in the local chemical environment of Al atoms when Sc substitutes for Al, leading to a redistribution of electron density.

Figure 2.

XPS survey spectra of (a–c) Sc-implanted AlN and (d–f) Sc-implanted ScAlN thin films at relative etching depths of 0 nm, 15 nm, 30 nm, and 45 nm. The Al-Sc peak, Al-Al peak, and Al-N peak in (e) are fitted, divided by different colors. The embedded tables in (c,f) refer to the atomic ratio of Sc, quantified by peak area.

High-resolution Al 2p spectra from the AlN films (Figure 2b) exhibit distinct chemical shifts corresponding to different depth profiles. The surface measurement shows a binding energy of 74.65 eV, exhibiting a 1.80 eV positive shift relative to the bulk value (72.75–72.82 eV) observed in etched samples. This shift correlates with surface oxidation, where atmospheric oxygen forms Al-O bonds [21,22]. The post-etching binding energy aligns with reference values (~73.50 eV) for stoichiometric AlN [23], confirming the predominance of Al-N bonding in the bulk material. Interestingly, the Al 2p spectrum on the non-etched surface of Sc-implanted ScAlN films exhibits greater complexity (Figure 2e). In addition to the Al-O component, a strong peak appears at around 72.30 eV. Considering the high Sc concentration on the surface, this peak is unlikely to be pure metallic Al. Instead, it is attributed to Al atoms in a modified chemical environment induced by Sc doping. Sc incorporation can lead to the formation of nitrogen vacancies and local charge redistribution [24]. Al atoms adjacent to Sc or nitrogen vacancies experience increased electron density, resulting in a lower binding energy compared to Al in a perfect Al-N4 lattice. High-resolution deconvolution fitting of the spectrum resolves it into three components: a Al-Sc component at ~71.60 eV (potentially Al influenced by nearby Sc atoms), a component at ~72.30 eV (metallic Al associated with nitrogen vacancy complexes), and the dominant Al-N lattice component at ~73.50 eV. Quantitative analysis revealed a progressive increase in Al 2p peak area from 19.78 to 23.43 with increasing etching depth from 15 nm to 45 nm.

The Sc 2p core-level spectra are crucial for confirming Sc incorporation and its chemical state (Figure 2c,f). The Sc 2p3/2 peak position is found around 400.8–401.2 eV, which is significantly lower than that typical for Sc2O3 (~402.0 eV) and aligns well with reported values for Sc-N bonds in nitride environments [25,26]. This confirms that the implanted Sc is predominantly bonded to nitrogen, rather than forming oxides. Notably, the Sc 2p peaks in Sc-implanted ScAlN films (Figure 2f) exhibited substantially greater intensity than those in Sc-implanted AlN films (Figure 2c), confirming effective Sc incorporation via the combined doping strategy. Approximately 12 at.% of implanted Sc was measured with increasing relative depth from 15 nm to 45 nm, higher than the 2.4 at.% in AlN without pre-doping. These observations indicate that the effective depth of Sc ion implantation exceeds 45 nm, while the majority of implanted-Sc concentrate within the near-surface region (approximately 30 nm depth). This comparative analysis confirms that ion implantation effectively enhances the Sc doping concentration in both material systems.

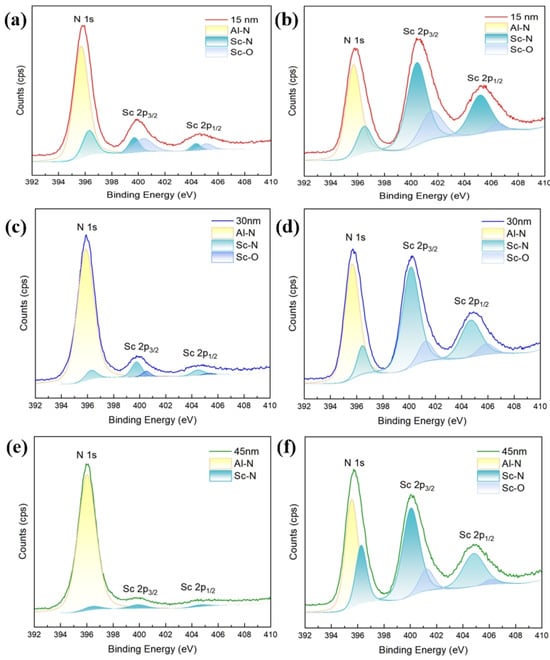

The N 1s spectra offer complementary information (Figure 3). For the Sc-implanted AlN film, the N 1s peak is dominated by the Al-N component at ~397.0 eV. A slight shift or broadening with depth is minimal, consistent with Sc being a minor dopant. The gradual reduction in Sc content at greater depths, combined with potential Sc-N bonding configurations in shallower regions, enhances the relative intensity of Al-N signals in deeper layers. For the Sc-implanted ScAlN films, the situation is exactly the opposite. The N 1s peak devolves into two components: the main Al-N component and a Sc-N component at a slightly lower binding energy (~396.7 eV). As the etching depth increases, the Sc-N components (396.7 eV) gradually strengthen, indicating that more Sc atoms are replacing Al atoms, achieving effective Sc doping.

Figure 3.

N 1S and Sc 2p core level spectra of (a,c,e) Sc-implanted AlN and (b,d,f) Sc-implanted ScAlN thin films at relative etching depths of 15 nm, 30 nm and 45 nm.

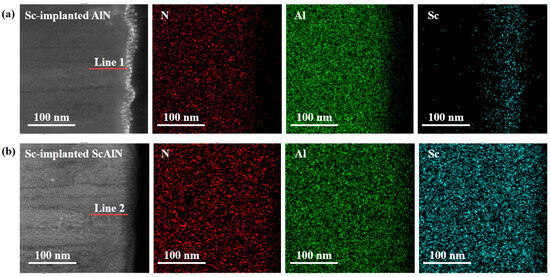

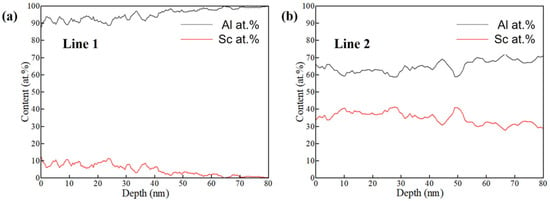

Cross-sectional specimens of the two Sc-implanted thin films were prepared using FIB and characterized by TEM and EDS to determine elemental distribution. EDS mapping images from surface regions (within ~200 nm depth) of both samples are displayed in Figure 4. In Sc-implanted AlN films, the implanted Sc predominantly resides within the 0–50 nm subsurface region (Figure 4a), exhibiting a characteristic Gaussian distribution profile typical of ion implantation processes [27]. Quantitative analysis of the EDS line scans (Figure 5) reveals distinct Sc incorporation characteristics. The average Sc atomic ratio remained below 10 at.% in Sc-implanted AlN films. And the Sc concentration decreases to near-zero levels beyond 70 nm depth. In contrast, for Sc-implanted ScAlN films, the measured Sc atomic ratio increased to above 30 at.%, representing a significant enhancement. It is noteworthy that the discrepancy in Sc concentration values between XPS (~10 at.%) and EDS (>30 at.%) for the Sc-implanted ScAlN film is attributed to their different sampling volumes [28,29]. The XPS quantification reflects the Sc concentration within the top ~5–10 nm, whereas the EDS value averages the concentration over the top ~200 nm. Therefore, above EDS findings demonstrate good consistency with the XPS compositional analysis.

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional EDS elemental mapping along the film growth direction for (a) Sc-implanted AlN thin film and (b) Sc-implanted ScAlN thin film.

Figure 5.

Cross-sectional EDS line-scan profiles for (a) Sc-implanted AlN thin films and (b) Sc-implanted ScAlN thin films. Line 1 and line 2 start at approximately 100 nm above the actual surface along the film growth direction.

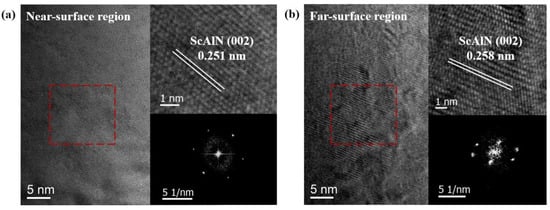

High-resolution TEM was employed to investigate the ion implantation-induced microstructural changes in the Sc-implanted ScAlN film (Figure 6). The most prominent effect is surface amorphization. Within the top ~5 nm (Figure 6a), clear lattice fringes are absent, and the contrast is relatively uniform, indicating a completely amorphized layer. This is a common consequence of ion bombardment due to the displacement of atoms from their lattice sites [30]. No sharp interface exists between this amorphous layer and the crystalline region beneath, suggesting a transition zone. At deeper regions (Figure 6b), the film remains crystalline but contains numerous defects. Localized lattice distortions, interruptions in fringe continuity, and contrast variations are evident. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) patterns from these regions (insets) confirm crystallinity but with diffuse spots, indicating strain and disorder.

Figure 6.

HRTEM images of Sc-implanted ScAlN thin film. (a) Near-surface region and (b) far-surface region. Insets show magnified views of the red-boxed areas and corresponding Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) patterns.

Lattice spacing measurements from distorted regions revealed variations. While some areas showed the expected (002) d-spacing for AlN (~0.249 nm), others exhibited expanded spacings up to 0.258 nm. This expansion along the c-axis is indicative of tensile strain induced by ion implantation. Such lattice distortion can potentially enhance the piezoelectric response by modifying the polarization state [31]. The dark-contrast regions likely correspond to clusters of point defects or strain fields.

4. Conclusions

The regulatory effects of Sc doping on the composition and structure of AlN thin films were investigated using a combined strategy of magnetron sputtering pre-doping and post-doping ion implantation. Experimental results demonstrated that the combined strategy significantly enhances the Sc doping level in AlN films. After Sc ion implantation, the Sc content in AlN films was below 10% with a decreasing Sc content distribution. For the co-doped ScAlN films, the Sc content increased to above 30 at.% with an optimized gradient distribution of Sc while maintaining a stable (002) preferred orientation in the bulk film. XPS analysis confirmed that the implanted Sc atoms bond with nitrogen (Sc-N bonding) and revealed the complex local chemical environment of Al atoms induced by Sc doping, including evidence for nitrogen vacancy-related states. EDS depth profiling revealed that the Sc distribution extended to a depth of ~200 nm beneath the surface. TEM analysis indicated that implantation introduced certain defects and tensile strain at the near-surface, which are microstructural features that could be engineered to modify functional properties.

In summary, this work verifies the feasibility of ion implantation as a supplementary doping technique. Future efforts may focus on further optimizing the distribution of Sc and crystal defects by adjusting implantation energy, flux, and annealing processes, thereby enabling stable doping at higher concentrations. These findings provide a foundation for developing AlN thin films with both high Sc doping concentrations and structural stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.; methodology, K.H. and L.C.; investigation, X.B.; resources, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y. and X.B.; writing—review and editing, X.Y.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, J.L. and W.W.; project administration, W.W.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ballandras, S.; Courjon, E.; Bernard, F.; Laroche, T.; Clairet, A.; Radu, I. New generation of SAW devices on advanced engineered substrates combining piezoelectric single crystals and silicon. In Proceedings of the 2019 Joint Conference of the IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium and European Frequency and Time Forum (EFTF/IFC), Miami, FL, USA, 14–18 April 2019; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Li, G.; Zhu, Z. Development and application of SAW filter. Micromachines 2022, 13, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Wu, L.; Chang, J.H.; Chang, F.C. SAW modes on ST-X quartz with an AlN layer. Mater. Lett. 2001, 51, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Duan, H. High performance 33.7 GHz surface acoustic wave nanotransducers based on AlScN/diamond/Si layered structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 113, 93502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, M.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, S. A piezoelectric micro machined ultrasonic transducer based hybrid-morph AlScN film. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 2023, 32, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zeng, F.; Tang, G.; Pan, F. Enhancement of piezoelectric response of diluted Ta doped AlN. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 270, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Iwazaki, Y.; Onda, Y.; Nishihara, T.; Sasajima, Y.; Ueda, M. Highly piezoelectric co-doped AlN thin films for wideband FBAR applications. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2015, 62, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Oguchi, H.; Van Minh, L.; Kuwano, H. High-Throughput Investigation of a Lead-Free AlN-Based Piezoelectric Material, (Mg, Hf)xAl1–xN. ACS Comb. Sci. 2017, 19, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, M.; Shigemoto, H.; Fujio, Y.; Nagase, T.; Aida, Y.; Umeda, K.; Akiyama, M. Giant increase in piezoelectric coefficient of AlN by Mg-Nb simultaneous addition and multiple chemical states of Nb. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 112901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor-A-Alam, M.; Olszewski, O.Z.; Campanella, H.; Nolan, M. Large piezoelectric response and ferroelectricity in Li and V/Nb/Ta co-doped w-AlN. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 13, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F. Surface Acoustic Wave Materials and Devices; Scientific Publishers: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fichtner, S.; Wolff, N.; Krishnamurthy, G.; Petraru, A.; Bohse, S.; Lofink, F.; Wagner, B. Identifying and overcoming the interface originating c-axis instability in highly Sc enhanced AlN for piezoelectric micro-electromechanical systems. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 35301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felmetsger, V.; Mikhov, M.; Ramezani, M.; Tabrizian, R. Sputter process optimization for Al 0.7 Sc 0.3 N piezoelectric films. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Glasgow, UK, 6–9 October 2019; p. 2600. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, M.; Kamohara, T.; Kano, K.; Teshigahara, A.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kawahara, N. Enhancement of piezoelectric response in scandium aluminum nitride alloy thin films prepared by dual reactive cosputtering. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, H.; Leveneur, J.; Mitchell, D.R.; Arulkumaran, S.; Ng, G.I.; Alphones, A.; Kennedy, J. Enhancing the piezoelectric modulus of wurtzite AlN by ion beam strain engineering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 12108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, H.; Jovic, V.; Mitchell, D.R.; Leveneur, J.; Anquillare, E.; Smith, K.E.; Kennedy, J. Tuning the electromechanical properties and polarization of aluminium nitride by ion beam-induced point defects. Acta Mater. 2021, 203, 116495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V. The Effect of Helium and Scandium Ion Implantation on the Structural, Vibrational and Piezoelectric Properties of Aluminium Nitride Thin Films. Ph.D. Thesis, Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, H.; Fuchs, F.; Leveneur, J.; Nancarrow, M.; Mitchell, D.R.; Schuster, J.; Kennedy, J. Giant piezoelectricity of deformed aluminum nitride stabilized through noble gas interstitials for energy efficient resonators. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manova, D.; Mändl, S. In situ XRD measurements to explore phase formation in the near surface region. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 126, 200901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Fletcher, I.; Couvertier, Z.C.; Schwab, B.; Gumpher, J.; Schoenfeld, W.V.; Fulford, J. Nucleation of highly uniform AlN thin films by high volume batch ALD on 200 mm platform. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2024, 42, 32401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Nisha; Kumar, P.; Katiyar, R.S. Enhanced Opto-Electrical Properties of Chalcogenide-Rich Tin Selenide Thin Film after Incorporating Sulfur Yielding Tin Sulfoselenide. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202301545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenakin, S.P.; Prada Silvy, R.; Kruse, N. Effect of X-rays on the surface chemical state of Al2O3, V2O5, and aluminovanadate oxide. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 14611–14618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, P.; Cadien, K. XPS analysis of AlN thin films deposited by plasma enhanced atomic layer deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 315, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.D.; Lipnitskii, A.G.; Nguyen, T.K.; Nguyen, T.T. Nitrogen Trapping Ability of Hydrogen-Induced Vacancy and the Effect on the Formation of AlN in Aluminum. Coatings 2017, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atabi, H.A.; Zhang, X.; He, S.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; Rotenberg, E.; Edgar, J.H. Lattice and electronic structure of ScN observed by angle-resolved photo emission spectroscopy measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 121, 182102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudresh, J.; Sandeep, S.; Venugopalrao, S.N.; Nagaraja, K.K. Impact of Sc-doping on structural, phase purity, and dielectric properties of AlN thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 137, 95306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Shibata, T.; Yoshizawa, K.; Uedono, A.; Tokunaga, H.; Palacios, T. Impurity diffusion in ion implanted AlN layers on sapphire substrates by thermal annealing. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 61, 26501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conconi, R.; Ortega, M.M.A.; Nieto, F.; Buono, P.; Capitani, G. TEM-EDS microanalysis: Comparison between different electron sources, accelerating voltages and detection systems. Ultramicroscopy 2025, 276, 114201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougaard, S. Practical guide to the use of backgrounds in quantitative XPS. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2021, 39, 11201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Wu, B.; Zong, W. Atomic-scale observation and prediction of gallium ion implantation induced amorphization on natural diamond surface. Vacuum 2023, 214, 112226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, U.; Sánchez-Rojas, J.L. Piezoelectric properties of sputtered AIN thin films and their applications. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2008, 54, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).