1. Introduction

Nickel-based superalloys, such as Inconel 718 and Inconel 738, are favorable groups of materials for high-temperature applications such as gas turbine blades, discs, shafts, etc., due to their unique combination of high strength, fatigue, creep, oxidation and corrosion properties [

1,

2]. Although they are highly resistant to oxidation and corrosion, there is a certain upper temperature limit for the usage of these materials. It is a never-ending desire to increase the service temperatures of these alloys which benefits from higher oxidation resistance. Aluminizing is one of the ways of increasing the oxidation resistance of nickel-based superalloys by forming a β-NiAl layer on their surfaces [

3,

4]. When exposed to high-temperature, this β-NiAl layer gets oxidized to form an Al

2O

3 scale in which diffusivity of oxygen is very low [

5]. By this way, penetration of oxygen into the nickel-based superalloy substrate is slowed and hence its service life is improved. In the literature, there are various methods to produce an aluminide coating such as pack aluminizing [

6], high and low activity aluminizing by chemical vapor deposition [

3,

4], slurry aluminizing [

7] and hot-dip aluminizing [

8]. Each method produces different microstructures with characteristic properties which affect the service life of the substrate significantly.

The beneficial effects of pack and hot-dip aluminizing methods on the oxidation of Inconel 718 and 738 alloys were previously studied. Kalaycı investigated the isothermal oxidation performance of hot dip aluminized Inconel 718 at 1000 °C for 1, 6, 48, 192, and 336 h. It was observed that Inconel 718 with an Al

2O

3 scale showed better oxidation resistance compared to Inconel 718 with a Cr

2O

3 scale [

9]. In the case of Inconel 738, Bai et al. studied the isothermal oxidation performance of aluminized Inconel 738LC samples by pack cementation method at 850, 1000, 1100, and 1200 °C for 288 h. It was observed that aluminized Inconel 738LC samples showed better oxidation resistance even at 1100 °C [

10].

Compared with conventional pack or hot-dip aluminizing, high/low-activity CVD aluminizing provides superior control over Al activity, enabling the formation of a uniform and compositionally precise NiAl diffusion layer. This method produces a cleaner coating without halide residues, offers better thickness controllability, and results in a more adherent β-NiAl layer with reduced porosity and improved oxidation resistance.

As presented above, while there are several studies on the oxidation behavior of pack and hot-dip aluminized Inconel 718 and Inconel 738 alloys, investigations on the CVD aluminized samples are extremely limited. With this motivation, the current study focuses on the effect of high activity CVD aluminizing on the oxidation resistances of Inconel 718 and Inconel 738LC superalloys within the temperature range of 925–1050 °C, which is conventionally considered above the typical service temperatures of these alloys. It is of interest to see how these two different alloys would respond to oxidation after being aluminized under the same conditions so that the role of substrate composition on the oxidation resistance can be delineated. To the best of authors’ knowledge, there is no study in open literature where the oxidation behavior of bare and high-activity CVD-aluminized Inconel 718 and Inconel 738LC alloys were investigated and compared under such conditions.

3. Results

Results of the oxidation tests of bare samples are given in

Table 3. At 950 °C, the Inconel 718 sample experienced a weight gain of 8.5 g/m

2 and that of the Inconel 738LC sample was 12.1 g/m

2. However, increasing the oxidation temperature to 1050 °C reversed the weight gains into significant weight losses for both samples. The Inconel 718 sample suffered a weight loss of 54.2 g/m

2, while the loss of Inconel 738LC sample was 35.6 g/m

2. The fact that the weight change values became negative after testing at 1050 °C indicates evaporative loss to be discussed later in

Section 4.1.

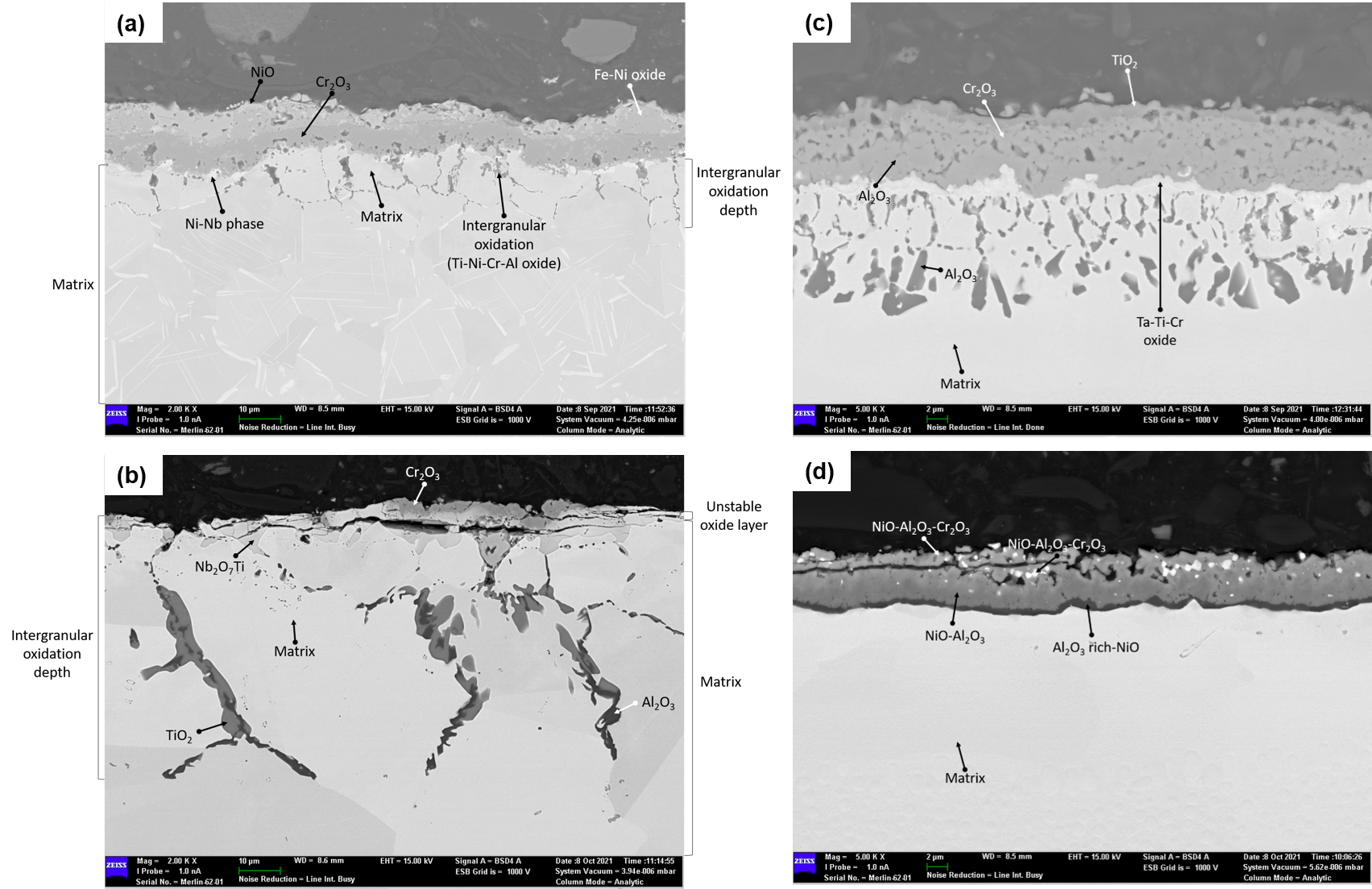

A cross-sectional SEM image of the bare Inconel 718 sample oxidized at 925 °C is given in

Figure 1a. A non-uniform and cracked NiO layer was detected at the top of the sample. The average thickness of this layer is 3.4 µm. A Fe-Ni oxide with a thickness of 5.0 µm was formed under the NiO layer. Cr

2O

3 layer was observed under the Fe-Ni oxide. The average thickness of the Cr

2O

3 layer is 6.3 µm. Ni-Nb oxide formed under the Cr

2O

3 layer at some regions. In addition to the oxides formed on the top, internal oxidation of Ti-Ni-Cr-Al is also observed in this sample. The average depth of internal oxidation reached to 9.30 µm.

A cross-sectional SEM image of the bare 718 sample oxidized at 1050 °C is given in

Figure 1b. A non-uniform oxide layer was observed on the top. The formed scale, mainly Cr

2O

3, was cracked, delaminated, and discontinuous. In addition to Cr

2O

3, Nb

2O

7Ti is also observed at the top region. Intergranular oxidation occurred under these surface oxides. Main products of intergranular oxidation are determined to be TiO

2 and Al

2O

3. The average depth of internal oxidation in this sample was 55.45 µm, which is significantly deeper than the value for the sample tested at 925 °C (9.30 µm).

In

Figure 1c, a cross-sectional SEM image of bare Inconel 738LC sample oxidized at 925 °C is given. The very top layer consists of TiO

2 while Cr

2O

3 and Al

2O

3 are present under this layer. This is followed by oxides of Ta-Ti-Cr. Also, formation of islands of Al

2O

3, i.e., internal oxidation, is observed to a significant degree in the matrix.

The cross-sectional SEM image of the bare Inconel 738LC sample oxidized at 1050 °C (

Figure 1d) was quite different than that oxidized at 925 °C. First of all, the overall thickness of the oxidized region was thinner. At the top layer, NiO-Al

2O

3-Cr

2O

3 was formed. A NiO-Al

2O

3 layer was observed under this layer where the Al content (hence the Al

2O

3) increased with depth. Different than the 925 °C test, no islands of Al

2O

3 formed at 1050 °C.

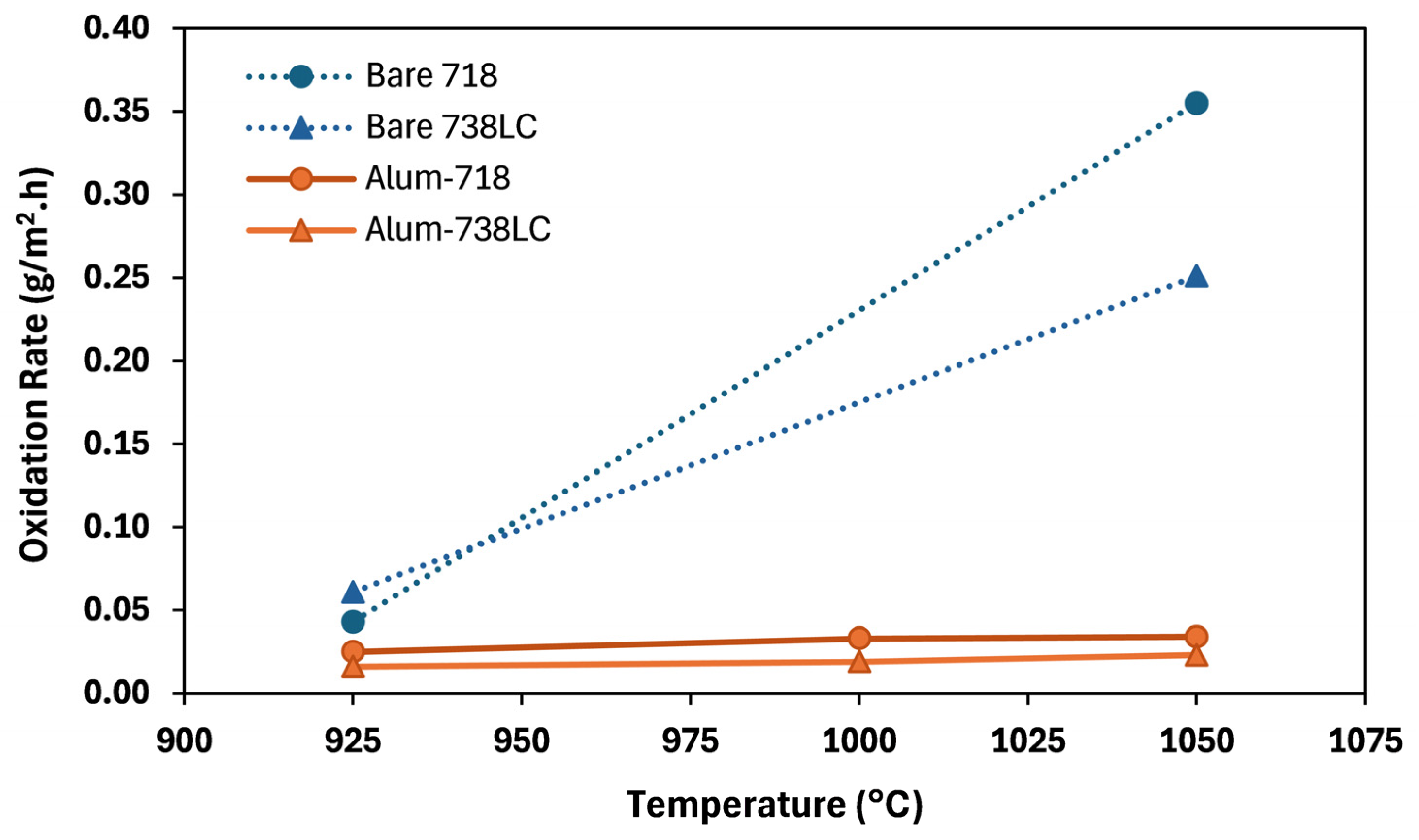

Results of the oxidation tests of aluminized samples are given in

Table 4. For the aluminized Inconel 718 samples, the weight gain after 200 h of oxidation was 5.0 g/m

2 at 925 °C, 6.6 g/m

2 at 1000 °C, and it was 6.8 g/m

2 at 1050 °C. Noticeably lower weight gains were measured in the case of aluminized Inconel 738LC samples; it was 3.1 g/m

2 after testing at 925 °C, 3.7 g/m

2 at 1000 °C and 4.5 g/m

2 at 1050 °C. Comparison of the weight change values of bare vs. aluminized samples (

Table 3 vs.

Table 4) clearly shows that aluminizing is very effective in protecting the Inconel substrates.

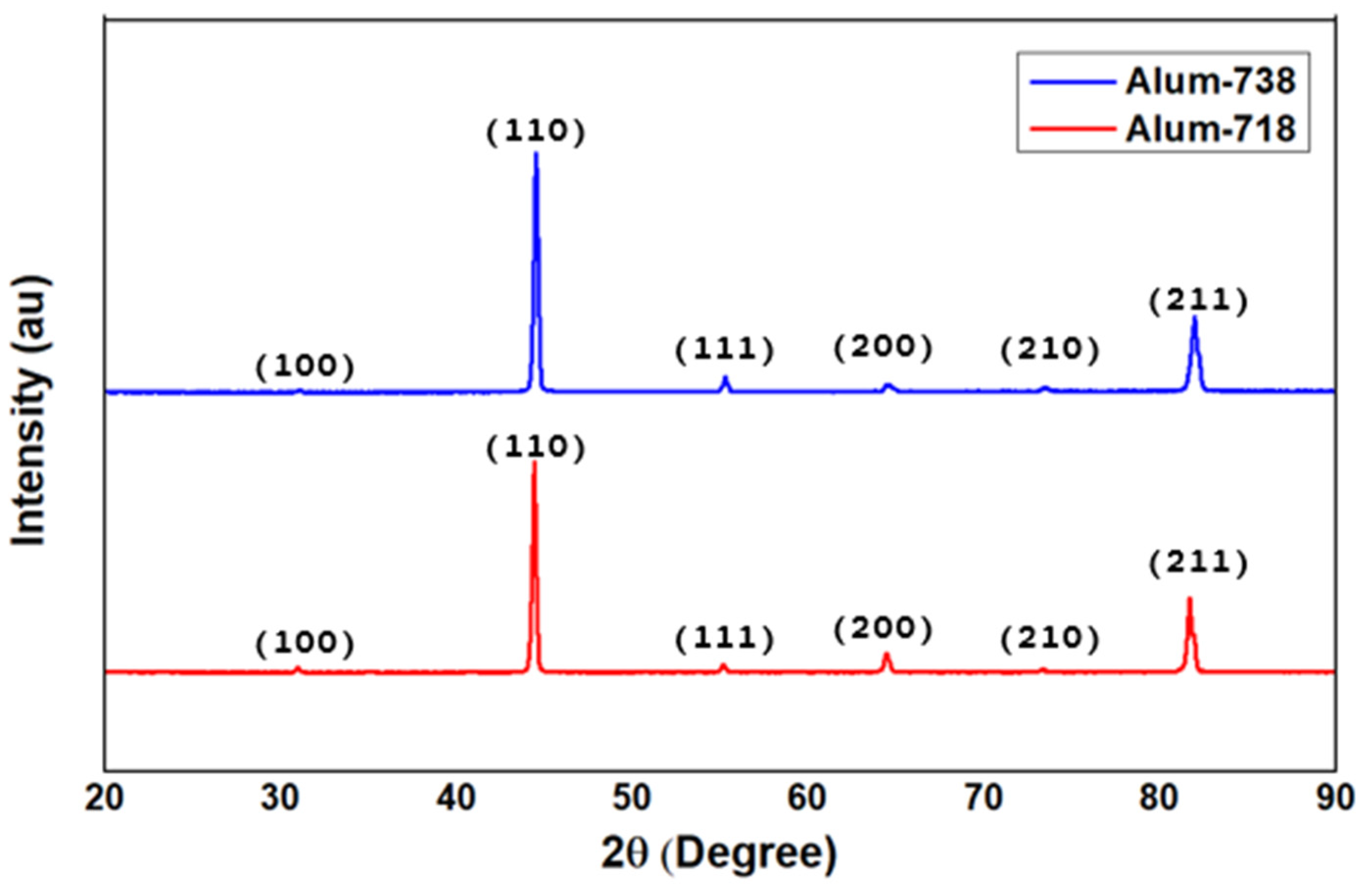

The XRD patterns of the aluminized samples are given in

Figure 2. The presence of β-NiAl (PDF 33-0948) phase is confirmed for both series of samples when compared with reference B-NiAl [

13].

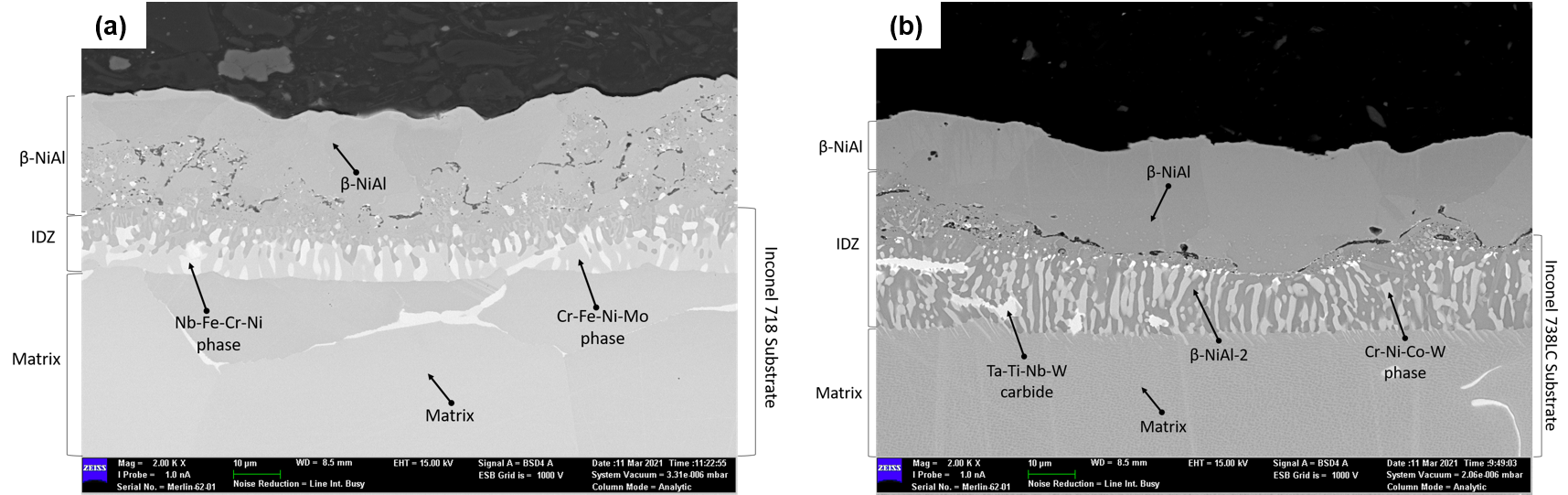

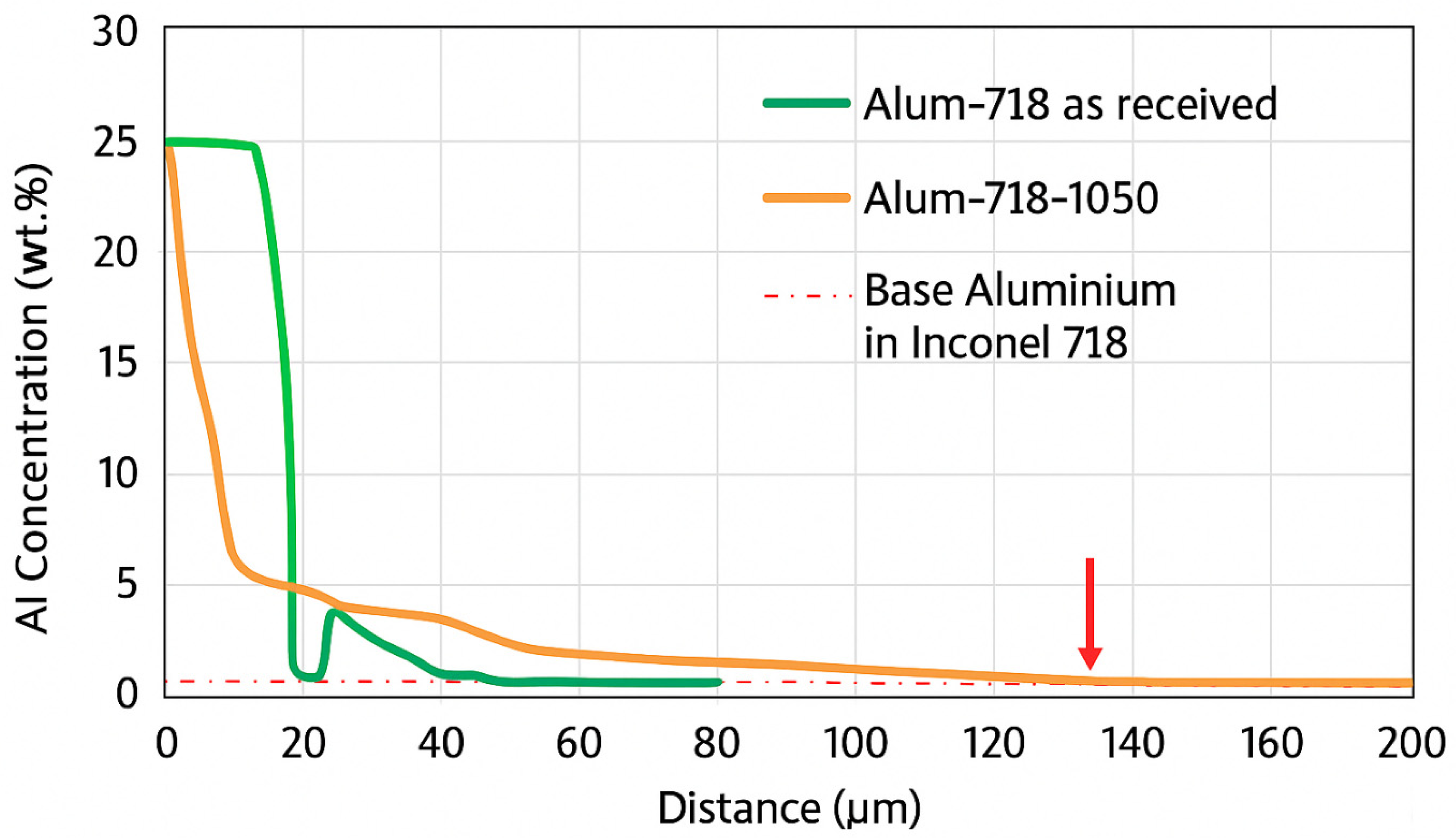

A cross-sectional SEM image of the aluminized 718 sample before an oxidation test (i.e., in as-aluminized condition) is given in

Figure 3a. At the top surface, β-NiAl phase was observed. The average thickness of the β-NiAl layer is 25.4 μm. An interdiffusion zone (IDZ) with a thickness of 11.9 μm was detected under the β-NiAl layer. Nb-Fe-Cr-Ni and Cr-Fe-Ni-Mo phases were present at IDZ.

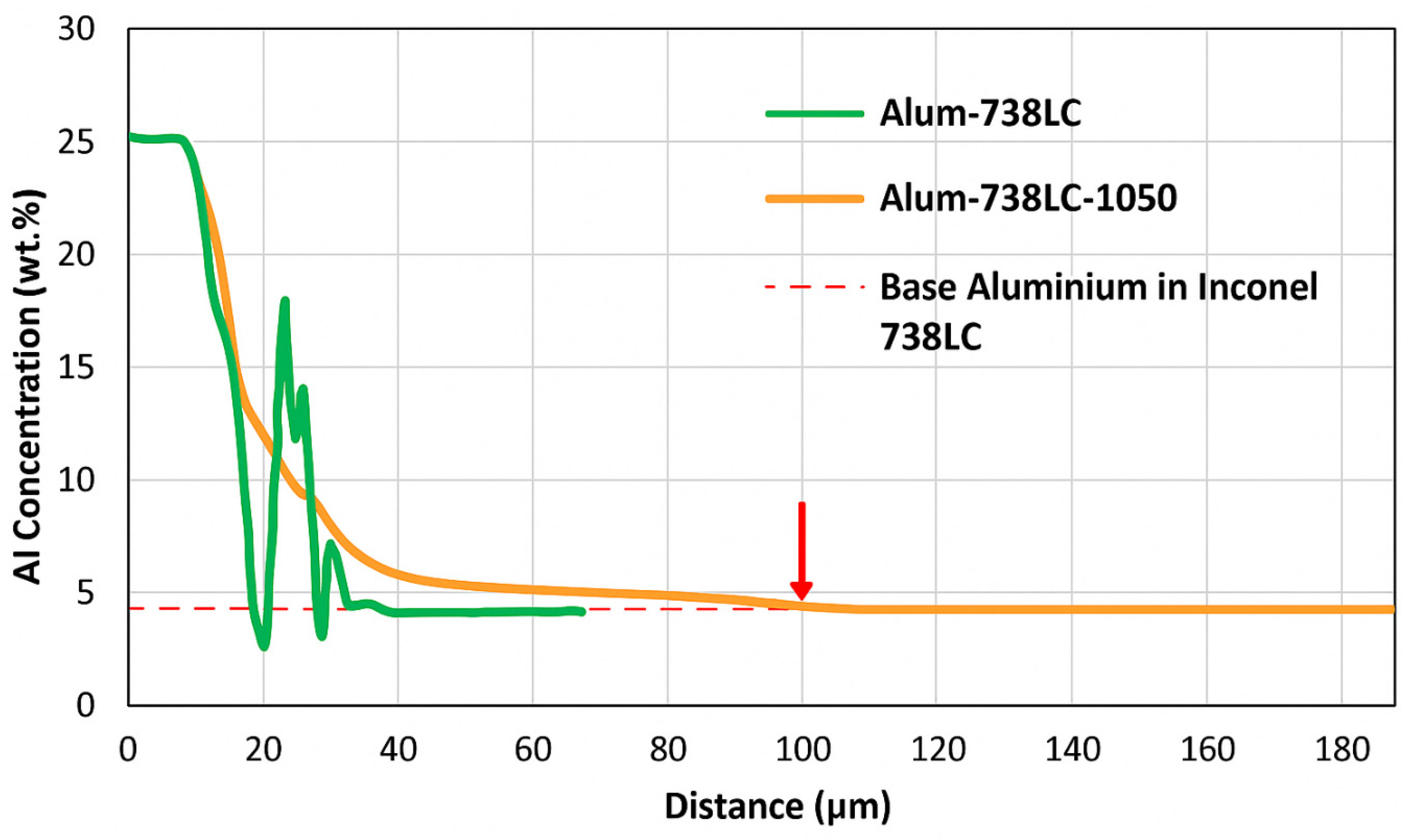

In

Figure 3b, a cross-sectional image of the as-aluminized 738LC sample can be seen. At the top, β-NiAl phase with a thickness of 24.2 µm was formed. Again an IDZ was formed under the β-NiAl layer. Average thickness of IDZ is about 16.8 µm. There were three different microstructural constituents in the IDZ of this sample: Ta-Ti-Nb-W carbides, β-NiAl, and Cr-Ni-Co-W phases.

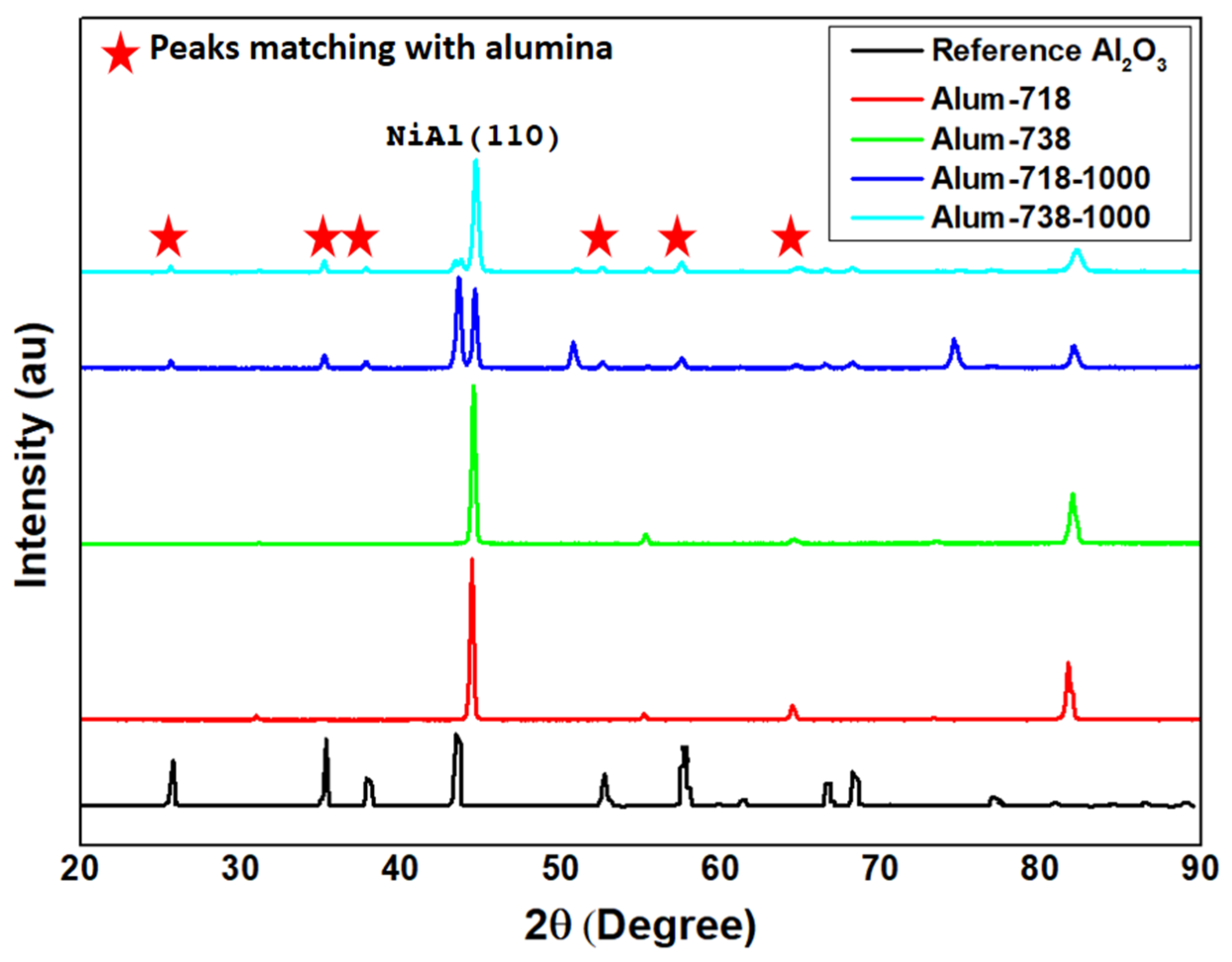

The XRD patterns of the aluminized samples oxidized at 1000 °C are given in

Figure 4. As expected, the peaks were dominantly from the α-Al

2O

3 (PDF 46-1212) [

14] scale formed during oxidation. In addition, some NiAl peaks were also observed.

A cross-sectional SEM image of the aluminized 718 sample which was oxidized at 925 °C can be seen in

Figure 5a. An Al

2O

3 scale with an average thickness of 2.8 µm was formed. β-NiAl layer with an average thickness of 18.49 µm comes under the Al

2O

3 scale. A Cr-Fe-Ni-Mo region was formed under the β-NiAl layer. The average thickness of Cr-Fe-Ni-Mo region was 7.4 µm. Nb-Cr-Mo-Ni particles were observed between the Cr-Fe-Ni-Mo and β-NiAl regions.

Figure 5b shows the cross-sectional SEM image of the aluminized 718 sample oxidized at 1000 °C. At the top a thicker Al

2O

3 scale with an average thickness 3.6 µm was formed. There were some cracks and voids in this layer. β-NiAl and other Ni-rich phases were observed under the Al

2O

3 scale. Nb-Mo-Cr particles were formed under the Ni-rich and β-NiAl phases.

In

Figure 5c, a cross-sectional SEM image of the aluminized 718 sample oxidized at 1050 °C is given. At the top Al

2O

3 partially covered the surface. The Al

2O

3 scale had many cracks and separated parts. The average thickness of Al

2O

3 layer was 3.3 µm. There were Ni-Cr-Fe phases under the Al

2O

3 layer. Also, some Nb-Mo-Cr particles are observed at regions close to the surface.

A cross-sectional SEM image of the aluminized 738LC sample which was oxidized at 925 °C can be seen in

Figure 5d. At the top, an Al

2O

3 layer was formed. Average thickness of the Al

2O

3 layer is 2.1 µm. Under the Al

2O

3 layer, a β-NiAl layer with a thickness of about 24.5 µm was present. Ta-Ni-Ti carbides were formed between β-NiAl and IDZ. Under the Ta-Ni-Ti carbides, IDZ can be observed. IDZ mainly consisted of β-NiAl phase. Average thickness of IDZ is 15.5 µm. A Cr-Ni-Co acicular phase with a thickness of 11.4 µm was formed under the IDZ. Ta-Ti-Nb carbides were observed in the acicular phase region.

A cross-sectional SEM image of the aluminized 738LC sample oxidized at 1000 °C is seen in

Figure 5e. An Al

2O

3 layer with an average thickness of 2.2 µm was formed at the top. Under the Al

2O

3 layer, β-NiAl layer with a thickness of 28.1 µm was observed. IDZ was observed under the β-NiAl layer. The average thickness of IDZ is 20.1 µm. Ni-Al-Co-Ti phase was seen between the β-NiAl and IDZ. In IDZ, Ta-Ti-Nb-Ni carbides and Cr-Ni-Co-W phases were observed. Under the IDZ, acicular Ni-Cr-Co-Ti region with a thickness of 9.8 µm was seen.

Finally, an SEM image of the aluminized 738LC sample oxidized at 1050 °C is given in

Figure 5f. As in all tested aluminized samples, an Al

2O

3 layer was formed at the top. Average thickness of the Al

2O

3 layer is 2.0 µm. Under the Al

2O

3 layer, a partial covering β-NiAl layer with a thickness of 12.9 µm was observed. Ti-Ta-Nb carbides were seen between the Al

2O

3 and β-NiAl layers. IDZ formed under the β-NiAl layer. The average thickness of IDZ is 17.6 µm. Two different carbides formed in the IDZ as Cr carbide and Ta-Ti-Nb carbide.

One general observation for all aluminized samples is the fact that they did not suffer from internal oxidation as some of the bare samples did.