Abstract

Gallium nitride (GaN)-based high electron mobility transistors (HEMTs) are pivotal for next-generation power-switching applications, but their reliability under high electric fields remains constrained by lattice mismatches and high dislocation densities in heterogeneous substrates. Herein, we systematically investigate the electrical performance and reliability of GaN-on-GaN HEMTs in comparison to conventional GaN-on-SiC HEMTs via DC characterization, reverse gate step stress, off-state drain step stress, and on-state electrical stress tests. Notably, the homogeneous epitaxial structure of GaN-on-GaN devices reduces dislocation density by 83.3% and minimizes initial tensile stress, which is obtained through HRXRD and Raman spectroscopy. The GaN-on-GaN HEMTs exhibit a record BFOM of 950 MW/cm2, enabled by a low specific on-resistance (RON-SP) of 0.6 mΩ·cm2 and a high breakdown voltage (BV) of 755 V. They withstand gate voltages up to −200 V and drain voltages beyond 200 V without significant degradation, whereas GaN-on-SiC HEMTs fail at −95 V (reverse gate stress) and 150 V (off-state drain stress). The reduced dislocation density suppresses leakage channels and defect-induced degradation, as confirmed by post-stress Schottky/transfer characteristics and Frenkel–Poole emission analysis. These findings establish GaN-on-GaN technology as a transformative solution for power electronics, offering a unique combination of high efficiency and long-term stability for demanding high-voltage applications.

1. Introduction

Gallium nitride (GaN)-based high electron mobility transistors (HEMTs) have emerged as cornerstone devices for next-generation microwave and power switching systems, leveraging their inherent advantages of a high electron saturation velocity (~2 × 107 cm/s), dense two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG, ~1 × 1013 cm−2), and a robust critical electric field (~3.3 MV/cm)—properties that far outperform traditional silicon (Si) and silicon carbide (SiC) power devices [1,2,3]. With the rapid development of electric vehicles (EVs), renewable energy inverters, and industrial power converters, there is an urgent demand for power semiconductors that combine high breakdown voltage (BV), low on-resistance, and long-term reliability under extreme operating conditions—requirements that GaN HEMTs are uniquely positioned to meet, yet their full potential remains constrained by material and structural limitations [4,5].

For decades, GaN HEMTs have been predominantly fabricated on heterogeneous substrates (e.g., 4H-SiC or Si) due to the high cost and scalability challenges of free-standing GaN (FS-GaN) substrates [6,7,8]. However, lattice mismatches (e.g., ~3.5% between GaN and 4H-SiC) and thermal expansion coefficient differences (e.g., ~50% mismatch between GaN and Si) between the AlGaN/GaN epitaxial stack and heterogeneous substrates inevitably induce high-density crystal defects, including threading dislocations and stacking faults [9]. These defects elevate the dislocation density to ~108–109 cm−2, which not only increases specific on-resistance (RON-SP) and off-state leakage currents, but also induces a severe current collapse under dynamic operation—issues that lead to increased power loss, thermal runaway, and even premature device failure in high-voltage systems, limiting the adoption of GaN HEMTs in mission-critical applications [10,11].

To address these challenges, FS-GaN substrates have gained traction in recent years, enabling homoepitaxial growth of AlGaN/GaN stacks that minimize lattice mismatch and reduce the dislocation density [12,13,14,15]. Our prior work introduced a Fe/C co-doped GaN buffer layer design that effectively mitigates interfacial charge accumulation and suppresses buffer leakage in GaN-on-GaN HEMTs, demonstrating their potential for radio frequency (RF) and power-switching applications [16]. However, the literature on GaN-on-GaN HEMTs remains limited in two key aspects: first, most studies focus solely on static DC performance (e.g., BV and RON-SP) and lack systematic evaluation of reliability under multi-stress conditions (reverse gate bias, off-state drain stress, and on-state power dissipation) that devices encounter in real-world operation; second, the direct correlation between dislocation density (a critical material quality metric) and stress-induced degradation mechanisms has not been fully established, leaving a gap in understanding how to optimize epitaxial structures for enhanced robustness.

In this study, we aim to fill these gaps by systematically investigating the electrical performance and reliability of GaN-on-GaN HEMTs in comparison to conventional GaN-on-SiC devices. We quantify dislocation density via high-resolution X-ray diffraction (HRXRD) and link it to device behavior under diverse stress tests, while also characterizing epitaxial strain via Raman spectroscopy to elucidate the role of initial structural stress in degradation. By focusing on both material-level properties and device-level reliability, this work not only validates the superiority of GaN-on-GaN technology but also provides a roadmap for optimizing GaN HEMTs for high-voltage, high-reliability power electronics applications.

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Device Structure and Fabrication Process

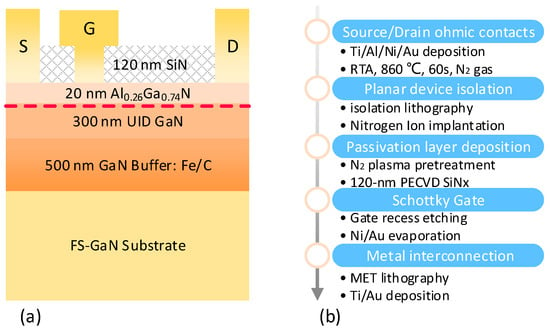

Figure 1a presents the cross-sectional structure of GaN HEMTs grown on a two-inch FS-GaN substrate. The epitaxial stack consists of a 20 nm Al0.26Ga0.74N barrier layer, a 300 nm unintentionally doped (UID) GaN channel layer, a 500 nm Fe/C co-doped GaN buffer layer, and a 350 μm thick FS-GaN substrate. For comparative analysis, the same epitaxial structure was grown on a three-inch SiC substrate (GaN-on-SiC) via Metal Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition (MOCVD), with a 60 nm AlN nucleation layer inserted to improve epitaxial quality. Hall effect measurements prior to device fabrication yielded carrier concentrations of 1.1 × 1013 cm−2 (GaN-on-SiC) and 1.0 × 1013 cm−2 (GaN-on-GaN), along with electron mobilities of 1570 cm2/V·s and 1680 cm2/V·s, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) The schematic cross-sectional structure of the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs. (b) Process flow for the fabricated GaN HEMTs in this work.

Both device types were fabricated by using an identical process flow to isolate substrate-induced effects. As illustrated in Figure 1b, the fabrication sequence began with the deposition of Ti/Al/Ni/Au layers for source/drain ohmic contacts, followed by rapid thermal annealing (RTA) at 860 °C in a N2 atmosphere for 60 s. Planar isolation was achieved via multi-energy nitrogen ion implantation after lithography. The wafer surface was pretreated with N2 plasma before depositing a 120 nm SiNx passivation layer, using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). The gate foot defined by lithography was opened using CF4-based plasma etching, followed by a T-shaped Ni/Au gate geometry for the Schottky contact. Ti/Au metal interconnections (MET) were formed as the final step. The standard device dimensions were as follows: gate-source spacing (Lgs) = 1.25 μm, gate length (Lg) = 0.5 μm, and source-drain spacing (Lsd) = 8 μm. For reliability tests, devices with uniform dimensions (Lgs = Lgd = Lg = 1 μm) were used to ensure consistent stress conditions. Based on the current experimental data, the growth process of GaN-on-GaN structures (using MOCVD) exhibits excellent compatibility with the growth processes of GaN structure on SiC substrates. Furthermore, the actual fabrication processes for both devices are performed on the same production line, demonstrating process compatibility. This proved that the MOCVD-based growth/fabrication process offers favorable affordability.

2.2. Epitaxial Material Characterization

HRXRD was employed to evaluate the crystalline quality of the AlGaN/GaN epitaxial layers, with full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) values of the (002) and (102) planes measured to calculate dislocation densities [12]. The total dislocation density (Ddis), screw dislocation density (Dscrew), and edge dislocation density (Dedge) were derived using the following equations [17]:

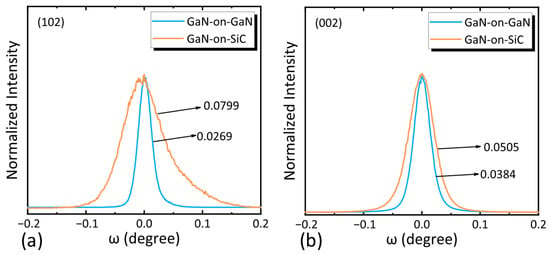

where bscrew = 0.52 nm and bedge = 0.32 nm are the Burgers vector lengths and β denotes the FWHM values from the XRD rocking curves. The rocking curves for the two samples are shown in Figure 2. The GaN-on-SiC structure exhibited FWHM values of 182 arcsec (002) and 288 arcsec (102), corresponding to a total dislocation density of 2.35 × 108 cm−2. In contrast, the GaN-on-GaN structure showed narrower FWHM values (125 arcsec for (002) and 97 arcsec for (102)), resulting in a significantly lower total dislocation density of 3.93 × 107 cm−2—an 83.3% reduction compared to GaN-on-SiC structure. This confirms the superior lattice matching and crystalline quality of homoepitaxial GaN-on-GaN structures.

Figure 2.

Rocking curves of the (a) (102) plane and (b) (002) plane in the GaN-on-GaN structure and the GaN-on-SiC structure.

Raman spectroscopy was used to characterize the strain state of the AlGaN barrier and GaN buffer layers, with the E2 (TO) mode employed as a strain marker. The stress (σ) was calculated using the following [18]:

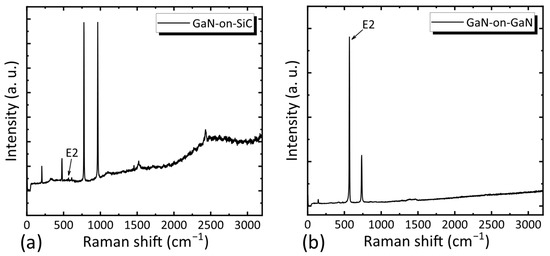

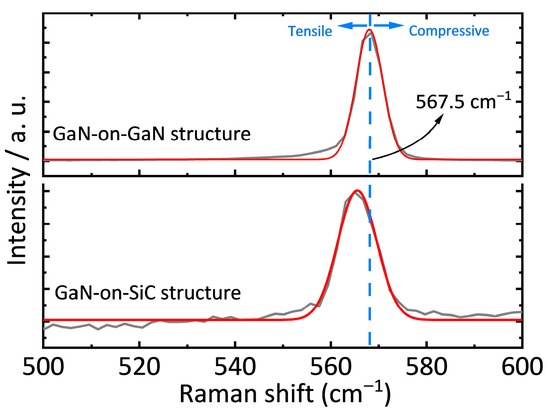

where Δω = ωmeasured − ωstress-free, ωstress-free = 567.5 cm−1 [19] and k = −3.4 cm−1GPa−1 (stress coefficient for GaN [20]). The full Raman spectra of the two samples are shown in Figure 3. To highlight the details of the E2 mode Raman peak, the Raman spectrum near 567.5 cm−1 has been magnified, as illustrated in Figure 4. The GaN-on-GaN structure exhibited a Raman peak at 567.6 cm−1, corresponding to a near-stress-free state (−0.03 GPa). In contrast, the GaN-on-SiC structure showed a peak shift to 565.5 cm−1, indicating significant tensile stress (0.59 GPa) arising from thermal mismatch and lattice mismatch. The AlGaN layer in the GaN-on-GaN structure experienced only lattice mismatch-induced tensile stress, whereas the GaN-on-SiC structure accumulated additional residual tensile stress from the GaN layer—further highlighting the structural advantage of FS-GaN substrates.

Figure 3.

Raman spectrum of the (a) GaN-on-SiC structure and the (b) GaN-on-GaN structure.

Figure 4.

Raman shifts in GaN film in the GaN-on-GaN structure and the GaN-on-SiC structure.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. DC Characterization

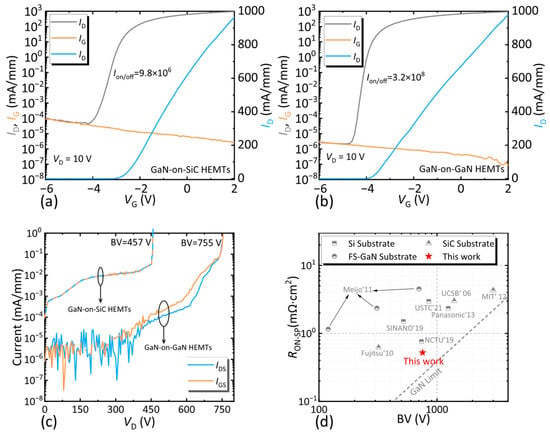

DC electrical properties were measured using Keithley B1500A and B1505A semiconductor device analyzers (Keithley Instruments (now part of Tektronix, Inc.), Solon, OH, USA). Figure 5a,b show the linear and semi-logarithmic transfer characteristics of the GaN-on-SiC and GaN-on-GaN HEMTs, respectively, measured at a drain bias (VD) of 10 V. For the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs, the off-state drain leakage current (ID, OFF) at VG = −6 V was 9.8 × 10−5 mA/mm, the maximum saturated drain current density (ID, max) at VG = 2 V was 960 mA/mm, and the on/off current ratio (Ion/off) was 9.8 × 106. The GaN-on-GaN HEMTs exhibited a much lower ID, OFF (2.6 × 10−6 mA/mm), a comparable ID, max (979 mA/mm), and a significantly higher Ion/off (3.2 × 108). This improvement in off-state performance is attributed to reduced dislocation density—dislocations act as conductive channels in GaN HEMTs, and their minimization effectively suppresses leakage currents [21]. The breakdown voltage (BV) was extracted under a leakage current criterion of 1 mA/mm (Figure 5c). GaN-on-GaN HEMTs with Lsd = 8 μm achieved a BV of 755 V, whereas GaN-on-SiC HEMTs of the same dimensions reached a maximum BV of 457 V. The superior breakdown performance stems from the lattice-matched homoepitaxial structure, which eliminates defect-induced leakage paths. Combined with the low RON-SP of 0.6 mΩ·cm2, the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs achieved a BFOM of 950 MW/cm2 (calculated as BFOM = BV 2/RON-SP)—the highest value reported to date for GaN-on-GaN HEMTs (Figure 5d) [22,23,24,25,26,27], underscoring their potential for high-efficiency power switching.

Figure 5.

The linear and semi-log scale of ID–VG transfer performance of (a) the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs and (b) the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs. (c) BV of GaN HEMTs on different substrates with Lsd = 8 μm. (d) Comparison of RON-SP versus BV from different research groups.

3.2. Reverse Gate Step Stress Characterization

Firstly, reverse gate step stress tests were performed to evaluate the device’s reliability under high electric fields, with a focus on degradation induced by the reverse piezoelectric effect [28]. During testing, VD = vs. = 0 V, and the gate voltage (VG) was stepped from 0 V to −200 V in increments of −5 V every 5 min. Gate current (IG), source current (IS), and drain current (ID) were monitored continuously, with a critical voltage (Vcritical) defined as being the point where current noise was detected [28].

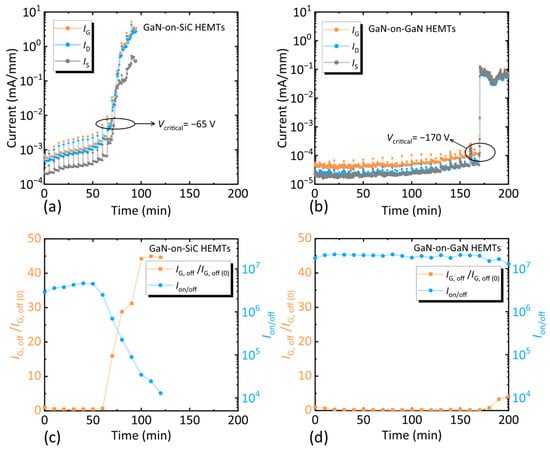

As shown in Figure 6a, GaN-on-SiC HEMTs failed at VG = −95 V, with current noise observed as early as VG = −65 V. In contrast, GaN-on-GaN HEMTs operated stably up to the analyzer’s limit of ±200 V, with current noise detected only at VG = −170 V (Figure 6b). Joh et al. reported that the reliability of the GaN-based HEMTs under a high electric field can be greatly improved by reducing the stress on the epitaxial layer. Thus, the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs can withstand such a high electric field due to the homogeneous epitaxial structure relieving the stress on the epitaxial layer, as demonstrated by Raman spectroscopy [29]. In addition, the several results obtained for both samples had the same change rule: IG ≈ ID + IS. The representative results are shown in Figure 6a,b. Due to the voltage applied to the gate, it was reasonable that IG was always larger than the other two currents for both samples. The difference between ID and IS of the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs was ~0.3 μA/mm before the critical voltage appeared, due to inferior epitaxial quality. On the contrary, due to the high material quality of the GaN-on-GaN structure, the ID and IS of the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs were almost exactly equal during the complete test.

Figure 6.

Changes in IG, IS, and ID of (a) the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs and (b) the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs in reverse gate step stress experiments. Relationship between the Ion/off and normalized IG, off of (c) the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs and (d) the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs as a function of reverse gate step stress, respectively. IG, off/IG, off (0) is defined as the ratio of the IG, off after each step post-stress to the stress-free IG, off.

At the end of each stress step, the Schottky and transfer characteristics of the device were detected to observe the degradation of the device’s performance. The voltage bias for the transfer characteristic was VD = 10 V and VG from −6 V to 2 V. The Ion/off of the device can be obtained from every transfer characteristic. The voltage bias for the Schottky characterization was VD = vs. = 0 V and VG from −10 V to 2 V. We defined the off-state gate current (IG, off) as the gate current at VG = −10 V in the Schottky characteristic. The Ion/off and the IG, off after each step were extracted from the transfer curve and Schottky curve, respectively. Figure 6c,d show the relationship between the Ion/off and IG, off/IG, off (0) of the two devices as a function of reverse gate step stress, respectively. The higher material quality of the GaN-on-GaN structure reduced the current through the AlGaN barrier layer [30,31], so the IG, off of the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs did not change significantly, even if the VG exceeded the Vcritical. As a contrast, the Ion/off of GaN-based HEMTs on the SiC substrate decreased from 2.8 × 106 to 1.3 × 104, while the Ion/off of the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs varied from 1.7 × 107 to 1.3 × 107. The results proved that the homogeneous epitaxial structure had better reliability due to lattice matching.

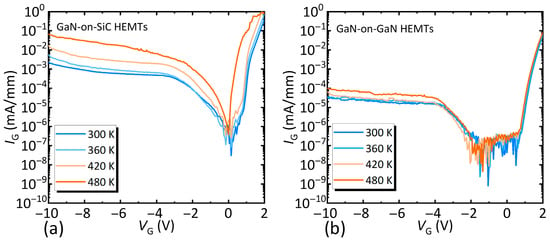

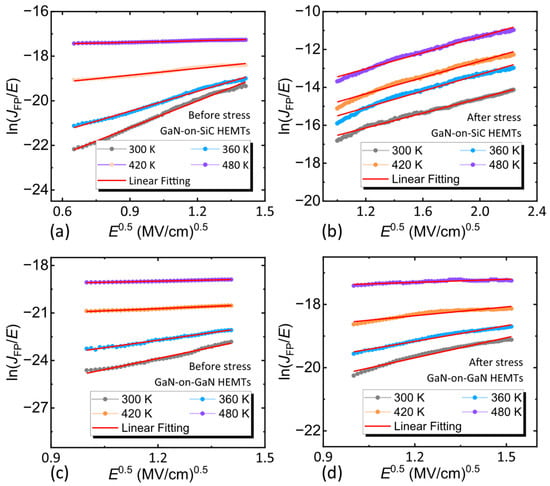

We characterized the thermal stability of the two devices through variable-temperature Schottky characteristics. To ensure both devices were in the same state, the variable-temperature Schottky characteristics were characterized after applying a −50 V gate stress. The temperature increased from 300 K to 480 K in 60 K increments, as shown in Figure 7. The performance of the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs degraded sharply with increasing temperature after applied stress. In contrast, the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs demonstrated very weak temperature dependence in the Schottky characteristics after stressing. This result indicates that the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs maintain excellent thermal stability, even under prolonged electric field stress conditions.

Figure 7.

The variable-temperature Schottky characteristics of (a) the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs and (b) the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs after applying a −50 V gate stress.

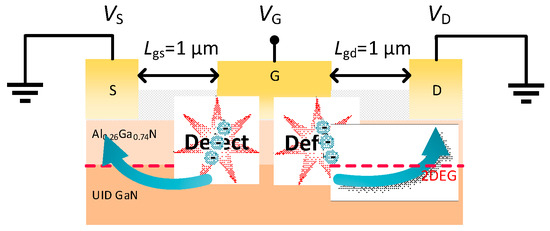

It has been reported that the inverse piezoelectric effect of the device can produce defects at the edge of the gate [32], resulting in leakage, as shown in Figure 8. To investigate the gate leakage after the occurrence of inverse piezoelectric effect, variable-temperature (temperature was increased from 300 K to 480 K in 60 K steps) Schottky characterization was performed on free-state devices and devices that just reached Vcritical. The Frenkel–Poole (FP) emission mechanism related to dislocation (extracted from the inverse plateau region of the Schottky curve) and Fowler–Nordheim (FN) tunneling mechanism (extracted from the inverse linear region of the Schottky curve) were extracted [33,34]. Because the FN tunneling mechanism was mostly determined by characteristics such as the thickness of the AlGaN barrier layer, the FN tunneling fitting curve of the two devices did not differ significantly before and after stress [35], and the results of the FP emission fitting curves were shown in Figure 9. Obviously, after the inverse piezoelectric effect, the FP emission mechanism of the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs was enhanced, whereas the gate leakage current mechanism of the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs was almost unchanged. This proved that the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs did not introduce too many defect states after the inverse piezoelectric effect occurred, which also explained why the Ion/off and the IG, off of the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs changed little after reaching the Vcritical. This result proved that the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs had better reliability than the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs, due to the superior quality of the epitaxial structure.

Figure 8.

Schematic of leakage after the occurrence of inverse piezoelectric effect. The arrow indicates the direction of the leakage.

Figure 9.

The FP emission fitting curves of the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs (a) before and (b) after stress. The FP emission fitting curves of the GaN-on- GaN HEMTs (c) before and (d) after stress.

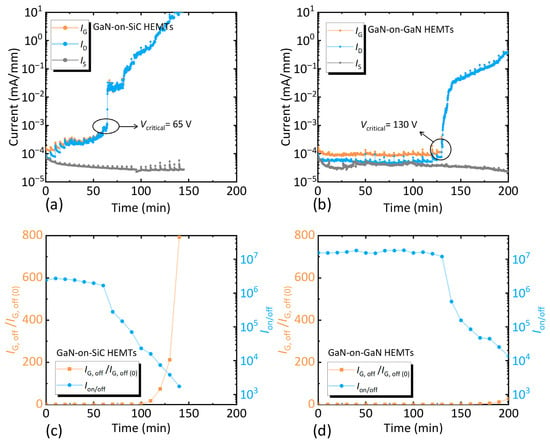

3.3. Off-State Drain Step Stress Characterization

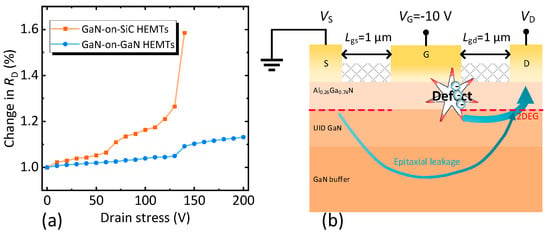

In addition, off-state drain step stress tests were conducted to assess reliability under high drain electric fields. For three-terminal devices, vs. was grounded, VG = −10 V, and VD was incrementally increased by 5 V every 5 min. The variation in three-terminal currents with drain stress was shown in Figure 10a,b. GaN-on-GaN HEMTs exhibited a Vcritical nearly twice that of GaN-on-SiC HEMTs, with GaN-on-SiC devices failing at VD = 150 V and GaN-on-GaN devices operating stably up to the analyzer’s maximum VD of 200 V. As shown in Figure 10c,d, post-stress transfer and Schottky characteristics indicated that performance degradation accelerated beyond Vcritical for both devices, but the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs suffered from more severe deterioration.

Analysis of leakage mechanisms in reverse gate step stress testing had already concluded that progressively intensifying stress introduced conductive defects into the AlGaN barrier layer. In the case of off-state drain step stress, further analysis of drain resistance (RD) revealed the origin of the device degradation. The relationship between RD and drain bias voltage of the two devices was extracted, as shown in Figure 11a. In this work, RD was measured by adopting the gate current injection method with IGinj = 10 mA/mm [36,37]. Obviously, the RD of the two devices increased with the drain stress, which was consistent with past reports [29].

Combined with the conclusion of the reverse gate step stress, the degradation mechanism of the devices under a high field condition was obtained. When VD < Vcritical, the trapping of AlGaN barrier layer in the active region increased with the electric field, resulting in RD gradually increasing with the bias voltage [29]. Since the homogeneous epitaxial structure had a higher material quality, the RD of the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs increased more slowly than that of the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs. The main leakage channel at this time was the impurities in the buffer and the original existing defects [30], as shown in Figure 11b. When VD > Vcritical, lattice defects were introduced into the AlGaN barrier layer due to the inverse piezoelectric effect [38]. Emerging defects not only enhanced the trapping but also formed conductive channels [30]. As illustrated in Figure 11b, the main leakage channel at this time occurred in the AlGaN barrier layer between the gate and the drain, resulting in a simultaneous increase in IG and ID for both devices in the off-state drain step stress test. At the same time, the RD tended to increase sharply with increasing drain stress, due to electrons trapped by the defects formed in the AlGaN barrier layer [39]. As a result, the Ion/off of the two devices decreased rapidly and the performance of the off-state (e.g., IG, off) deteriorated sharply. In the whole process, because the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs were lattice-matched, they had a higher Vcritical, beyond which the device did not immediately fail. The lattice-matched structure delayed this degradation, confirming their robust epitaxial quality.

Figure 10.

Changes in IG, IS, and ID of (a) the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs and (b) the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs in off-state drain step stress experiments. Relationship between the Ion/off and IG, off/IG, off (0) of (c) the GaN-on-SiC HEMTs and (d) the GaN-on-GaN HEMTs as a function of off-state step drain stress, respectively. IG, off/IG, off (0) is defined as the ratio of the IG, off after each step post-stress to the stress-free IG, off.

Figure 11.

(a) The relationship between drain resistance (RD) and drain bias voltage of the two devices. (b) Schematic diagram of leakage of devices at a high field. The arrow indicates the direction of the leakage.

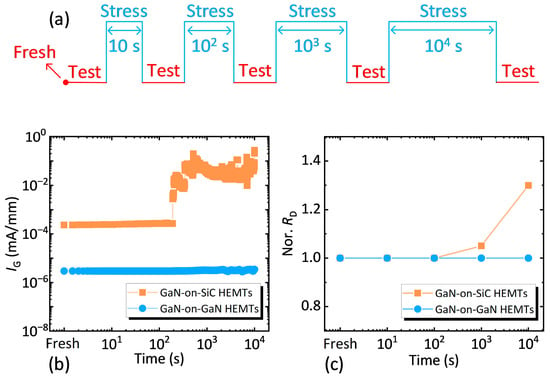

3.4. On-State Electrical Stress Characterization

Furthermore, on-state electrical stress tests were performed to simulate real-world operating conditions, where devices are exposed to both high voltage and current. Stress was applied at VD = 30 V and VG = 0 V for durations of 10 s, 100 s, 1000 s, and 10,000 s, respectively. Static electrical characteristics and RD were evaluated pre- and post-stress. The schematic diagram of the on-state stress reliability experiment for the device is illustrated in Figure 12a.

Figure 12.

(a) Schematic of the on-state stress test setup for both samples. Relationship between (b) IG and (c) normalized RD with on-state stress time for both samples. Normalized RD is defined as the ratio of the RD after each step-stress to the stress-free RD.

During on-state operation, dislocations promote trap formation and electron capture [40], with high temperatures (from VD × ID power dissipation) and bias stress accelerating defect generation [39,41]. As shown in Figure 12b,c, GaN-on-SiC HEMTs exhibited rapid degradation of IG and RD after 1000 s of stress, whereas GaN-on-GaN HEMTs maintained a stable performance throughout the 10,000 s test. This stability is attributed to the low dislocation density of the GaN-on-GaN epitaxial structure, which minimizes trap formation and electron trapping—critical for long-term reliable operation in power-switching applications.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigates the influence of dislocation density on the reliability of GaN HEMTs under high electric fields, comparing GaN-on-GaN and GaN-on-SiC devices through comprehensive electrical and stress tests. GaN-on-GaN HEMTs achieve a record BFOM of 950 MW/cm2, enabled by a high BV of 755 V and a low RON-SP of 0.6 mΩ·cm2. The homoepitaxial structure reduces dislocation density by 83.3% and minimizes initial tensile stress, endowing the devices with exceptional reliability under reverse gate step stress, off-state drain step stress, and on-state electrical stress. These results validate that reducing dislocation density is a key strategy to enhance the performance and reliability of GaN HEMTs, positioning the GaN-on-GaN technology as a transformative solution for advanced power electronics. With its unique combination of high efficiency and robustness, GaN-on-GaN HEMTs hold great promise for demanding applications such as electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and industrial power converters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and M.W.; methodology, S.L.; validation, L.Y., H.L. and B.H.; formal analysis, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, M.W.; supervision, X.M.; project administration, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62234009; in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62574152; in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62090014; in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62188102; in part by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant 2022T150505; in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities XJSJ24053.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meneghini, M.; De Santi, C.; Abid, I.; Buffolo, M.; Cioni, M.; Khadar, R.A.; Nela, L.; Zagni, N.; Chini, A.; Medjdoub, F.; et al. GaN-Based Power Devices: Physics, Reliability, and Perspectives. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 181101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Lai, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, B. GaN Power Integration for High Frequency and High Efficiency Power Applications: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 15529–15542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounika, B.; Ajayan, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Nirmal, D. Recent Developments in Materials, Architectures and Processing of AlGaN/GaN HEMTs for Future RF and Power Electronic Applications: A Critical Review. Micro Nanostruct. 2022, 168, 207317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, H.; Baines, Y.; Beam, E.; Borga, M.; Bouchet, T.; Chalker, P.R.; Charles, M.; Chen, K.J.; Chowdhury, N.; Chu, R.; et al. The 2018 GaN Power Electronics Roadmap. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 163001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Häberlen, O.; Lidow, A.; lin Tsai, C.; Ueda, T.; Uemoto, Y.; Wu, Y. GaN-on-Si Power Technology: Devices and Applications. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2017, 64, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, U.K.; Shen, L.; Kazior, T.E.; Wu, Y.-F. GaN-Based RF Power Devices and Amplifiers. Proc. IEEE 2008, 96, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, J.; Singerl, P. RF GaN-on-Si Powers Wireless Future. Microw. J. 2024, 67, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Jia, F.; Lu, H.; Hou, B.; Zhang, M.; Du, J.; Chang, Q.; Deng, L.; Yu, Q.; Li, S.; et al. Record Power Performance of 33.1 W/Mm with 62.9% PAE at X-Band and 14.4 W/Mm at Ka-Band from AlGaN/GaN/AlN:Fe Heterostucture. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–13 December 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Alshahed, M.; Heuken, L.; Alomari, M.; Cora, I.; Tóth, L.; Pècz, B.; Wächter, C.; Bergunde, T.; Burghartz, J.N. Low-Dispersion, High-Voltage, Low-Leakage GaN HEMTs on Native GaN Substrates. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2018, 65, 2939–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ercan, B.; Ren, C.; Ikeda, H.; Chowdhury, S. A Study on the Impact of Dislocation Density on Leakage Current in Vertical GaN-on-GaN p-n Diodes. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 4206–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.; Kawasaki, S.; Watanabe, H.; Tanaka, A.; Honda, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Iso, K.; Amano, H. Reverse Leakage Mechanism of Dislocation-Free GaN Vertical p-n Diodes. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2023, 44, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.K.; Chao, P.C.; Pizzella, M.T.; Actis, R.; Meharry, D.E.; Nichols, K.B.; Vaudo, R.P.; Xu, X.; Flynn, J.S.; Dion, J.; et al. 9.4-W/Mm Power Density AlGaN-GaN HEMTs on Free-Standing GaN Substrates. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2004, 25, 596–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Feng, C.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Xiao, H.; Wang, X. Room Temperature 2DEG Mobility Above 2350 Cm2/V·s in AlGaN/GaN HEMT Grown on GaN Substrate. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Meng, B.; Wu, M.; Sun, H.; Yang, B.; Yang, L.; Zou, X.; Zhang, M.; Lu, H.; Hou, B.; et al. Enhancing Thermal Dissipation Ability and Electrical Performance in GaN-on-GaN HEMTs through Stepped-Carbon Buffer Design. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 125, 212104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, M.; Yang, L.; Yang, B.; Sun, H.; Zhang, M.; Hou, B.; Lu, H.; Ma, X.; Hao, Y. 15.1 W/Mm Power Density GaN-on-GaN HEMT With High-Gradient Stepped-C Doped Buffer. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2025, 46, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, M.; Yang, L.; Hou, B.; Yu, Q.; Li, S.; Shi, C.; Zhao, W.; Lu, H.; Chen, W.; et al. First Demonstration of State-of-the-Art GaN HEMTs for Power and RF Applications on A Unified Platform with Free-Standing GaN Substrate and Fe/C Co-Doped Buffer. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–7 December 2022; pp. 11.3.1–11.3.4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Wang, C.; Xu, S.; Zheng, X.; He, Y.; Ma, X.; Lu, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Lattice-Matched AlInN/GaN Multi-Channel Heterostructure and HEMTs with Low on-Resistance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 119, 122104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.; Chua, S.J.; Chen, P.; Miao, Z.L. Micro-Raman Investigation of Strain in GaN and AlxGa1−xN/GaN Heterostructures Grown on Si(111). J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 3503–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Huang, L.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, G. Stress and Dislocation Control of GaN Epitaxial Films Grown on Si Substrates and Their Application in High-Performance Light-Emitting Diodes. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 771, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Holtz, M.; Faleev, N.N.; Temkin, H. Dependence of the Stress–Temperature Coefficient on Dislocation Density in Epitaxial GaN Grown on α-Al2O3 and 6H–SiC Substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 95, 1692–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, B.; Shikha, S.; Singh, A.; Kumar, J.; Soni, A.; Dutta Gupta, S.; Raghavan, S.; Shrivastava, M. Time Dependent Shift in SOA Boundary and Early Breakdown of Epi-Stack in AlGaN/ GaN HEMTs Under Fast Cyclic Transient Stress. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2020, 20, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshimura, Y.; Sugiyama, T.; Takeda, K.; Iwaya, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Kamiyama, S.; Akasaki, I.; Amano, H. AlGaN/GaN Heterostructure Field-Effect Transistors on Fe-Doped GaN Substrates with High Breakdown Voltage. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 50, 084102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamura, M.; Ohki, T.; Kikkawa, T.; Imanishi, K.; Imada, T.; Yamada, A.; Hara, N. Enhancement-Mode GaN MIS-HEMTs With n-GaN/i-AlN/n-GaN Triple Cap Layer and High-k Gate Dielectrics. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2010, 31, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S.; Piedra, D.; Sun, M.; Gao, X.; Guo, S.; Palacios, T. 3000-V 4.3-mΩ·Cm2 InAlN/GaN MOSHEMTs With AlGaN Back Barrier. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2012, 33, 982–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C.S.; Dora, Y.; Fichtenbaum, N.; McCarthy, L.; Keller, S.; Mishra, U.K. High-Breakdown Enhancement-Mode AlGaN/GaN HEMTs with Integrated Slant Field-Plate. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Electron Devices Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–13 December 2006; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, M.; Ueda, T.; Tanaka, T.; Ueda, D. GaN on Si Technologies for Power Switching Devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2013, 60, 3053–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Chen, J.-Y.; Han, P.-C.; Lee, M.-W.; Yang, K.-S.; Wang, H.-C.; Chang, P.-C.; Luc, Q.H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Dee, C.-F.; et al. Normally-Off Tri-Gate GaN MIS-HEMTs with 0.76 mΩ·cm2 Specific On-Resistance for Power Device Applications. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2019, 66, 3441–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, J.; del Alamo, J.A. Critical Voltage for Electrical Degradation of GaN High-Electron Mobility Transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2008, 29, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, J.; del Alamo, J.A. Mechanisms for Electrical Degradation of GaN High-Electron Mobility Transistors. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Electron Devices Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–13 December 2006; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, D.A.; Smith, D.J.; Passaseo, A.; Tasco, V.; Stocco, A.; Meneghini, M.; Meneghesso, G.; Zanoni, E. Electroluminescence and Transmission Electron Microscopy Characterization of Reverse-Biased AlGaN/GaN Devices. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2013, 13, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, E.; Danesin, F.; Meneghini, M.; Cetronio, A.; Lanzieri, C.; Peroni, M.; Meneghesso, G. Localized Damage in AlGaN/GaN HEMTs Induced by Reverse-Bias Testing. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2009, 30, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, D.; Kauerauf, T.; Medjdoub, F.; Das, J.; Van Hove, M.; Srivastava, P.; Cheng, K.; Leys, M.; Mertens, R.; Decoutere, S.; et al. A Comprehensive Reliability Investigation of the Voltage-, Temperature- and Device Geometry-Dependence of the Gate Degradation on State-of-the-Art GaN-on-Si HEMTs. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Electron Devices Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–8 December 2010; pp. 20.3.1–20.3.4. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D.; Lu, H.; Cao, D.; Chen, D.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Y. On the Reverse Gate Leakage Current of AlGaN/GaN High Electron Mobility Transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 153503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turuvekere, S.; Karumuri, N.; Rahman, A.A.; Bhattacharya, A.; DasGupta, A.; DasGupta, N. Gate Leakage Mechanisms in AlGaN/GaN and AlInN/GaN HEMTs: Comparison and Modeling. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2013, 60, 3157–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turuvekere, S.; DasGupta, A.; DasGupta, N. Effect of Barrier Layer Thickness on Gate Leakage Current in AlGaN/GaN HEMTs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2015, 62, 3449–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; del Alamo, J.A. Activation Energy of Drain-Current Degradation in GaN HEMTs under High-Power DC Stress. Microelectron. Reliab. 2014, 54, 2668–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; Del Alamo, J.A. Electrical and Structural Degradation of GaN High Electron Mobility Transistors under High-Power and High-Temperature Direct Current Stress. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 117, 025707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghesso, G.; Meneghini, M.; Stocco, A.; Bisi, D.; de Santi, C.; Rossetto, I.; Zanandrea, A.; Rampazzo, F.; Zanoni, E. Degradation of AlGaN/GaN HEMT Devices: Role of Reverse-Bias and Hot Electron Stress. Microelectron. Eng. 2013, 109, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; del Alamo, J.A. Electrical Degradation of InAlN/GaN HEMTs Operating Under ON Conditions. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2016, 63, 3487–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A.Y.; Lee, I.-H. Deep Traps in GaN-Based Structures as Affecting the Performance of GaN Devices. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2015, 94, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.R.; Joshi, V.; Gupta, S.D.; Shrivastava, M. On the Channel Hot-Electron’s Interaction With C-Doped GaN Buffer and Resultant Gate Degradation in AlGaN/GaN HEMTs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2021, 68, 4869–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).