Abstract

Genetically modified (GM) forage crops engineered to accumulate elevated levels of lipids offer potential benefits for ruminant nutrition and greenhouse gas mitigation. However, robust and reproducible workflows for producing, harvesting, and preserving GM forage biomass under containment remain a critical bottleneck, particularly where regulatory constraints preclude field-scale evaluation. Here, we describe a controlled-environment workflow for the repeated cultivation, harvesting, and ensiling of GM high-metabolizable-energy (HME) perennial ryegrass and corresponding null controls. Plants were grown under greenhouse containment, subjected to multiple regrowth cycles, and harvested biomass was wilted and ensiled using small-scale laboratory silos. Silage fermentation characteristics, total lipid content, and fatty acid (FA) composition were assessed following short- and long-term storage. Over 16 months, approximately 130 kg dry matter (DM) of each genotype was produced across multiple harvests and ensiling batches. Seasonal variation strongly influenced herbage composition, with water-soluble carbohydrate concentrations 4–5-fold higher in spring–summer than autumn–winter. Following ensiling, HME silage consistently retained elevated FA content compared with null controls (4.85% vs. 2.75% DM) and higher gross energy (18.1 vs. 17.5 MJ kg−1 DM). FA profiling indicated that major FA classes in HME were preserved across storage durations. After 342 days of storage, HME silage maintained 76% higher FA content, 4% greater DM digestibility, and 0.3–0.8 MJ kg−1 DM higher metabolizable energy. Both genotypes exhibited good fermentation quality, with pH consistently below 4.1 and adequate lactic acid production. This study does not evaluate animal performance or methane mitigation outcomes but establishes a practical and reproducible methodology for generating characterized GM silage material under containment suitable for subsequent in vivo studies, addressing a key translational gap between GM forage development and animal-based evaluation.

1. Introduction

Genetically modified (GM) plants with high-metabolizable energy (HME) represent a major advance in plant nutritional improvement [1,2,3,4]. In perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.), this trait was designed to increase potential metabolizable energy (ME) via increased lipid-derived gross energy (GE), rather than directly measuring ME, and results in foliar fatty acid (FA) content up to 80% higher than conventional cultivars, corresponding to approximately 1 MJ kg−1 dry matter (DM) higher GE. This increase in foliar lipid content is achieved by enhanced triacylglycerol biosynthesis via overexpression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1, together with reduced lipid turnover associated with stabilization of lipid droplets by an engineered cysteine-oleosin [4]. Field validation studies in the United States have demonstrated that HME ryegrass can maintain elevated leaf FA and GE under repeated defoliation and agronomic conditions representative of managed perennial pasture systems [5], supporting its potential to improve forage energy density.

Elevated lipid content in forages has also been proposed as a strategy to influence rumen fermentation and potentially reduce enteric methane (CH4) emissions. Dietary lipids are known to affect methanogenesis through multiple mechanisms, including shifts in rumen microbial populations and hydrogen utilization; however, these effects are dose-dependent and strongly influenced by diet composition and intake context [6]. Based on prediction equations and in vitro evidence, increased FA content in HME ryegrass has been hypothesized to reduce enteric CH4 emissions; however, empirical in vivo validation of CH4 mitigation by HME ryegrass remains limited [7]. Translating increased GE into ME and validating any mitigation potential requires in vivo animal studies, as intake regulation, rumen adaptation, and digestibility can substantially influence outcomes [8,9].

In New Zealand (NZ), AgResearch maintains world-class infrastructure for CH4 measurement in ruminants, including sheep and cattle respiration chambers. However, GM organisms are regulated under the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996, which requires that GM forage for research purposes be produced under physical containment [10]. These regulatory constraints present practical challenges for generating sufficient quantities of high-quality GM forage material while preserving key compositional traits required for animal evaluation.

Herbage utilization methods strongly influence forage composition and downstream animal responses. While fresh forage offers immediate nutrient availability, ensiling provides storage stability and enables accumulation of biomass across multiple harvests. Alternative preservation methods such as freezing or haymaking are impractical or undesirable for high-lipid forages under containment due to scale limitations and increased lipid oxidation [11,12,13]. Ensiling therefore represents the most practical and containment-compatible approach for preserving HME ryegrass biomass for animal studies, and previous work indicates that a substantial proportion of FA can be retained during this process [7].

Thus, this study focuses on methodological development by establishing a reproducible, containment-compatible workflow for producing, ensiling, and storing GM HME ryegrass suitable for downstream animal-based evaluation, rather than testing agronomic or nutritional treatment effects. This enables controlled animal studies to be conducted in compliance with regulatory requirements while acknowledging inherent environmental variability.

The present study addresses this gap by developing and evaluating a contained greenhouse-based workflow for the repeated cultivation, harvesting, and ensiling of GM HME ryegrass. Specifically, we aimed to: (i) establish a reproducible method for producing silage from GM ryegrass grown under containment; (ii) assess the retention and compositional stability of total lipids and FA classes following short- and long-term ensiling; and (iii) generate characterized silage material suitable for subsequent animal feeding and CH4 mitigation studies. This study is intentionally methodological in scope and does not evaluate animal performance or CH4 emissions but provides a practical framework to support the translational evaluation of GM forage crops from plant biotechnology to animal-based research.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment complied with law and regulations concerning the use of GM materials in research in NZ, administered by the NZ Ministry of Primary Industries. The material was grown in the AgResearch Grasslands Research Centre, greenhouse containment facilities (40°22′49.4″ S 175°36′52.1″ E) in the period from August 2022 to April 2024.

2.1. Experimental Design and Replication

Plants grown in individual pots constituted the biological experimental units for plant growth and herbage composition measurements. Repeated harvests from the same plants were treated as temporal observations and not as independent biological replicates. For all silage-related analyses, individual laboratory silos constituted the experimental units. Harvested material from multiple plants within a harvest was homogenized prior to ensiling, and each silo was treated as an independent analytical replicate.

2.2. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

From August 2022, the plants used in this experiment were germinated from populations of T4 homozygous HME and T4 null seed on trays filled with Daltons® Seed Mix in a controlled environment room, maintained at 22 °C, humidity at 65–70%, and a light intensity of 500–1000 µmol m−2 s−1 with a 10 h photoperiod. After two weeks, the seedlings were supplied with a standard soluble fertilizer solution (Yates™ Thrive, DuluxGroup Pty Limited, Gracefield, New Zealand), consisting of 1 g/L at a rate of 200 mL/tray (30 × 45 cm2, 100 seedlings). Subsequently, the 4-week-old seedlings were transplanted into 1.2 L plastic planter bags filled with Daltons® Premium Potting Mix and grown on tables (40 pots/m2) in a containment greenhouse. The tables were lined with a 5 mm thick absorbance sheet for capillary irrigation.

Following three weeks of propagation, the first harvest was conducted (October 2022); this included all material 5–6 cm above the soil surface. Following the harvest, the plants were fertilized with a solution of 1.5 g/L Yates™ Thrive All Purpose Soluble Fertilizer at the rate of 15 L per 200 pots, applied by watering can and administered the day after harvesting. Subsequent harvests occurred at 3-week intervals by cutting foliage to a stubble height of 5–6 cm, culminating with the seventh harvest.

Following the seventh harvest, a 2–3-week gap was implemented for greenhouse sanitation (Table 1) prior to replacement with a new set of plants. This schedule ensured optimal growth conditions and systematic maintenance throughout the cultivation process.

Table 1.

Insecticides and fungicides registered for use on pastures and forage crops in New Zealand [14].

It has to be noted that plants were initially established in 1.2 L pots and subsequently transferred to 1.8 L pots (from March 2023) to prevent root restriction during later growth stages. Pot size was consistent within each greenhouse round and was treated as a fixed factor in statistical analyses. Therefore, any variation associated with pot size is captured by the greenhouse round random effect in the model.

2.3. Greenhouse Space and Irrigation System

Two greenhouses (A and B) were utilized to grow HME and null ryegrass. The genotypes were cultivated on alternating tables to minimize environmental variations such as light, temperature, and airflow. Greenhouse A provided a total table area of 100 m2. The first section (40 m2) operated for 16 months (October 2022 to January 2024), accommodating 800 HME ryegrass plants and 800 null plants. The second section (60 m2) operated for 9 months (May 2023 onward), accommodating 1200 HME ryegrass plants and 1200 null plants. Greenhouse B operated for 14 months (December 2022 to January 2024), providing 40 m2 table area for 800 HME ryegrass plants and 800 null plants.

To optimize growth conditions for each greenhouse, the irrigation system was adjusted based on growing seasons. During summer months (December–February), cultivation tables were irrigated twice daily using 40 min intervals with an automated capillary system. The irrigation regime was reduced to 30 min once daily during winter months (June–August). During spring (September–November) and autumn (March–May), irrigation was adjusted to 20 min twice daily. Irrigation volumes were determined empirically to avoid visible water stress and maintain consistent plant growth, rather than being adjusted based on direct measurements of substrate moisture or plant water status.

2.4. Fertilization

Given that this material will be fed to animals, it is important not to supply excess N, as this would lead to “luxury consumption” by the plant, resulting in excessive nitrate levels in the leaves [15], which can be toxic to the animal consuming it. Our fertilizer regime using a solution of 1.5 g/L Yates™ Thrive (DuluxGroup Pty Limited, New Zealand) at a rate of 15 L per 200 pots, at 3-week intervals, was designed to provide the 190 kg N ha−1 y−1 allowable limit plus replace the N removed at each harvest, ensuing uniform nitrogen availability and assimilation across genotypes during vegetative growth [16]. Fertilizer inputs were applied at a consistent rate per plant throughout the experiment and were not adjusted over time. Foliar total nitrogen content, measured at each harvest, declined progressively over subsequent harvests within a round, indicating a gradual decrease in nutrient availability that may contribute to observed compositional changes. As root biomass accumulated over time, the amount of liquid fertilizer received per plant effectively decreased with successive applications, which likely contributed to reduced plant growth at later harvests.

2.5. Pest Management

Powdery mildew, aphids, thrips, and sciarid fly do not typically create issues under field conditions. However, in greenhouse environments, which are characterized by high humidity, limited air circulation, and consistently moderate temperatures, they can become problematic, resulting in major challenges when cultivating ryegrass indoors [17]. We modified the spatial arrangement to improve airflow along benches, reducing powdery mildew incidence. Electric fans were installed to accelerate airflow, effectively reducing powdery mildew infestation. Table 1 provides a list of insecticides and fungicides that are registered for use on pasture and forage crops in NZ and were used by us during the course of producing the ensiled materials. All chemical applications were conducted by approved handlers in accordance with regulations [14].

Between plant replacement cycles (after completion of the seventh harvest), cultivation tables were thoroughly cleaned one week before filling new propagation pots. Since many aphids and sciarid flies likely originate from soil and drainage systems, drains were bleached and soil treated with diflubenzuron (Table 1) prior to planting.

2.6. Ensiling Processes

The herbage material of each genotype was thoroughly mixed and manually cut into lengths ranging from 2 to 5 cm. Fresh harvests underwent subsampling and immediate freezing in liquid nitrogen, followed by storage at −80 °C for subsequent chemical analysis. The remaining material was wilted overnight at 20−22 °C, reducing the weight to approximately 50% of fresh weight, equivalent to roughly 30% DM. To promote silage fermentation, the wilted material was inoculated with a LAB solution (Ecosyl MTD/1 inoculant, Ecosyl Products Inc., Byron, IL, USA; 1.54 × 1011 cfu/g) at a recommended application rate of 106 CFUs per gram of wilted material.

Table sugar was added at 50 g kg−1 wilted fresh weight to standardize fermentation in small-scale laboratory silos, including both HME and null material. This approach was used to minimize confounding effects arising from seasonal and developmental variability in endogenous water-soluble carbohydrate (WSC) concentrations of greenhouse-grown ryegrass. Accordingly, the ensiling system was designed to support comparative assessment of genotype effects under a controlled fermentation environment, rather than to simulate commercial ensiling practice. While this addition may affect the absolute concentrations of fermentation end-products, it was applied uniformly and therefore does not confound comparisons between HME and null silage. Both LAB and sugar solutions were uniformly mixed with the wilted ryegrass. About 50 g of the completed premixed material underwent subsampling, vacuum packing, and was subsequently used for chemical analysis at 50–80 days of silage fermentation (unless otherwise indicated). The remaining material (5–20 kg, depending on season and harvest number) was placed into a vacuum bag (100–120 μm thickness), from which air was evacuated using a vacuum sealer (RHVS1, Russell Hobbs, Failsworth, UK). The vacuum process was repeated with a second outer bag. Silage packets were stored in a dimly lit environment at room temperature for a minimum of 30 days [7] and could be preserved for up to 2 years [18].

While many laboratory-scale silage studies employ buckets or fixed-volume vessels to simulate on-farm conditions [19,20], Johnson et al. [21] demonstrated that vacuum-packed polythene bags provide a cost-effective and flexible method for ensiling forage, allowing higher throughput and more consistent packing compared to fixed-volume vessels. This approach has been widely adopted in silage research due to its advantages in handling small sample sizes and controlling fermentation conditions. We selected vacuum bags because they accommodated variable harvest yields, allowed efficient air removal (minimizing potential spoilage at exposed surfaces), and enabled visual inspection of silage without disrupting the sample. Furthermore, it was possible to subsample and re-vacuum, enabling the material to be maintained until use in animal feeding trials. This method ensured consistent preservation while maintaining experimental control over storage conditions.

A total of 56 silage batches were produced (28 HME and 28 null).

For general chemical analysis of silage (Table 2), subsamples from 12 HME silage batches and 12 null silage batches were randomly selected (8 from Glasshouse A and 4 from Glasshouse B) and sampled between 50 and 80 days after ensiling (DAS). Independent selection for this analysis did not account for sequential harvests or seasonal effects and was intended to provide a representative snapshot of silage quality across containment facilities.

Table 2.

Production and chemical analysis of silage from null and HME genotypes.

For long-term storage stability analyses (Table 3), silos were randomly selected across greenhouse facilities, sequential harvests, and seasons. To maintain paired comparisons, when an HME silo was selected, the corresponding null-genotype silo produced on the same day and under identical ensiling conditions was selected as its matched pair. Each selected silo was subsampled at 52 DAS, re-vacuum sealed, and subsequently resampled at 342 DAS, such that measurements at both time points were obtained from the same silo batches.

Table 3.

Comparison of silage quality after long-term storage.

2.7. Chemical Analyses

Chemical analyses were conducted on silage material sampled at defined storage intervals, as described in Section 2.6, with each silo representing one analytical replicate. Depending on the intended analysis, silage subsamples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C or over-dried at 65 °C for a minimum of 3 days and then stored at room temperature.

Silage DM was determined by weighing prior to and again after the oven-drying process. For freeze-dried samples, silages were subjected to a 3-day freeze-drying process and stored at −80 °C until subsequent analysis.

FA and total carbon and N were analyzed from the oven-dried samples after they were powdered. The determination of FA employed the fatty acid methyl ester analysis (FAMEs) technique and quantification via GC-FID [25,26]. The FAMEs analysis was tailored to only quantify the C16–C18 lipids since we had previously shown that these account for 98.5% of leaf lipids that are influenced by HME [4].

Total carbon and total N were determined using an elemental analyzer (Vario Max Cube, Elementar, Hesse, Germany). Crude protein was subsequently calculated on the assumption that the average N content of proteins is 16% (i.e., N × 6.25). Additional analyses, such as neutral detergent fiber (NDF, Tecator Fibertec, AOAC 2002.04), GE (bomb calorimeter), and in vitro enzymatic dry matter digestibility (DMD) [24], were conducted on freeze-dried and powdered material by the accredited nutrition laboratory at Massey University (Palmerston North, New Zealand).

Predicted ME was estimated from the equation ME1 (MJ/kg DM) = 0.153 × DMD (%) − 1.057, as reported by Auldist et al. [22], and ME2 (MJ/kg DM) = GE × DMD (kg/kg DM) × 0.82, where 0.82 represents a typical digestible energy-to-ME conversion factor [23].

WSC were extracted and quantified from 25 mg DM samples of freeze-dried plant material using the method described by Parsons et al. [27]. The soluble extract contained fructose, glucose, sucrose and fructans of a low degree of polymerization, referred to as the low molecular weight fraction (LMW). Fructans of a high molecular weight fraction (HMW) were extracted by twice mixing the remaining insoluble residue with 1 mL of water and centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 15 min), then removing the supernatant. WSCs were analyzed in LMW and HMW fractions using the anthrone method [28]. LMW were calibrated against a series of known concentrations of sucrose, and HMW were calibrated using inulin standards. All samples and standards were determined as a mean value of duplicate assays.

NH4+–N extraction involved using approximately 20 mg of freeze-dried sample homogenized with 0.5 mL of 0.1 M HCl and 0.25 mL of chloroform, as outlined by Hachiya and Okamoto [29], without any modifications. The determination of ammonium followed the method detailed by Bräutigam et al. [30].

Volatile FAs (VFAs) were extracted from 5 g of fresh silage in 50 mL of deionized water by blending to create a slurry, followed by incubation in a closed container with shaking at 130 rpm at room temperature for 1 h. The extract was filtered through a 100 μm mesh and stored at −80 °C until analysis. VFA concentrations were determined using GC-MS following an established method described by Ghidotti et al. [31].

Lactic acid (LA) was determined in approximately 100 mg of fresh silage that was ground to fine powder while maintaining the sample in liquid nitrogen. One milliliter of deionized water was added and homogenized until the mixture formed a slurry. The slurry was transferred to an ice-cold 2 mL Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 14,000 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The resulting 25 μL soluble fraction was then used in a reaction mix with FeCl3 solution, as demonstrated by Borshchevskaya et al. [32].

Silage pH was determined using a calibrated pH meter (Accumet™, AE150, Fisher Scientific, Auckland, New Zealand) from a subsample of 15 g of fresh silage homogenized with 50 mL of deionized water, as described by Cherney and Cherney [33]. The homogenized plant material (fresh herbage or silage) was filtered, and the water extract was weighed, transferred into a plastic vessel with a magnetic stirrer and titrated to pH 3.0 with 0.1 M HCl to release the bicarbonate ion as carbon dioxide. The water extract was then titrated up to pH 6.0 with 0.1 M NaOH. From this, the buffering capacity (BC) was calculated using the Milliequivalents of NaOH required to raise the pH of the water extract from 4.0 (±0.02) to 6.0 (±0.03) after correction for the titration value of a water blank [34]. The BC and pH values of samples were determined as a mean of duplicate assays.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models implemented in R (version 4.5.1) using the lme4 and lmerTest packages and/or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with genotype as the main effect. Where applicable, genotype and storage duration were treated as fixed effects. Season was treated as either a fixed or random effect depending on the analysis, reflecting whether seasonal differences were of direct interest or served to capture environmental variation across greenhouse rounds. Pot (plant), greenhouse round, and silo were included as random effects as appropriate to account for repeated measures and the hierarchical experimental structure [35,36]. Therefore, repeated harvests from the same plants were treated as temporal observations rather than independent biological replicates. Model assumptions were evaluated by inspection of residual plots. Estimated marginal means were calculated using the emmeans package, with Tukey adjustment applied for multiple comparisons, with significance assessed at p < 0.05. Error bars and ranges given are standard error of the mean.

3. Results

3.1. Seasonal Effects on Biomass Production Under Containment

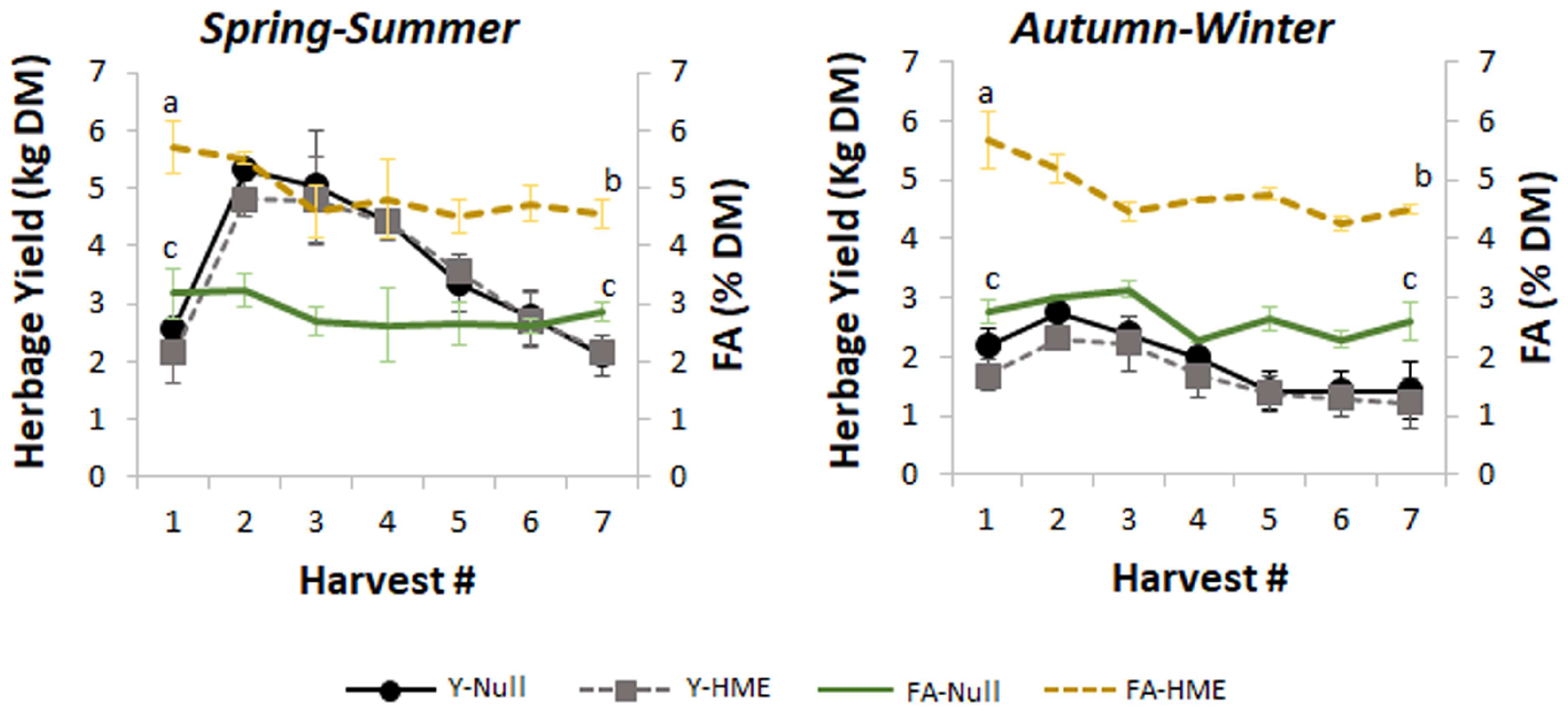

Foliage from HME ryegrass and corresponding nulls was hand harvested from two containment greenhouse facilities, with a combined cultivated area of 140 m2. Figure 1 presents the herbage yield of HME and null ryegrass across seven consecutive harvests with a three-week regrowth interval, comparing results between spring–summer and autumn–winter growing seasons. No significant difference in yield (kg DM) per harvest was observed between the two genotypes in either greenhouse.

Figure 1.

Seasonal variation in herbage yield and fatty acid (FA) content across multiple harvests. Left panel shows spring–summer period and right panel shows autumn–winter period. Data represent mean between two greenhouse harvests of yield (kg dry matter (DM), left y-axis) and FA content (% DM, right y-axis) ± standard error of the mean for null (solid lines) and HME (dashed lines) genotypes across seven sequential harvests. Letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences in FA levels between the first and the last harvest within each season. Yield peaks occurred at harvest 2–3 in spring–summer but remained relatively stable and lower during autumn–winter. FA content showed no different seasonal patterns, with higher and more variable levels in HME compared to null.

Higher biomass accumulation was observed during the spring–summer period compared with the autumn–winter period (p < 0.01). During the spring–summer cultivation period of 2022–2023, in both greenhouses, a notable decline in herbage growth rate was observed after the third harvests (Figure 1). As anticipated, the autumn–winter season showed reduced but stable herbage yields, indicating the grass’s ability to maintain production in controlled greenhouse conditions, even under suboptimal irradiance.

3.2. Herbage FA Content

Herbage FA contents in null plants remained stable across seven consecutive harvests with a three-week regrowth interval, showing no significant differences between spring–summer and autumn–winter growing seasons (Figure 1, green lines). However, herbage FA contents in HME plants decreased by approximately 0.5% of DM from the first to seventh harvest (Figure 1, gold dashed lines).

3.3. Seasonal Effects on Herbage Composition Prior to Ensiling

Fresh herbage DM content—approximately 10–15% DM for both HME and null ryegrass—did not significantly differ between genotypes.

In this study, BC was numerically lower in fresh HME herbage (576 ± 23.2 mmoles/kg DM) compared to null herbage (586 ± 28.0 mmoles/kg DM).

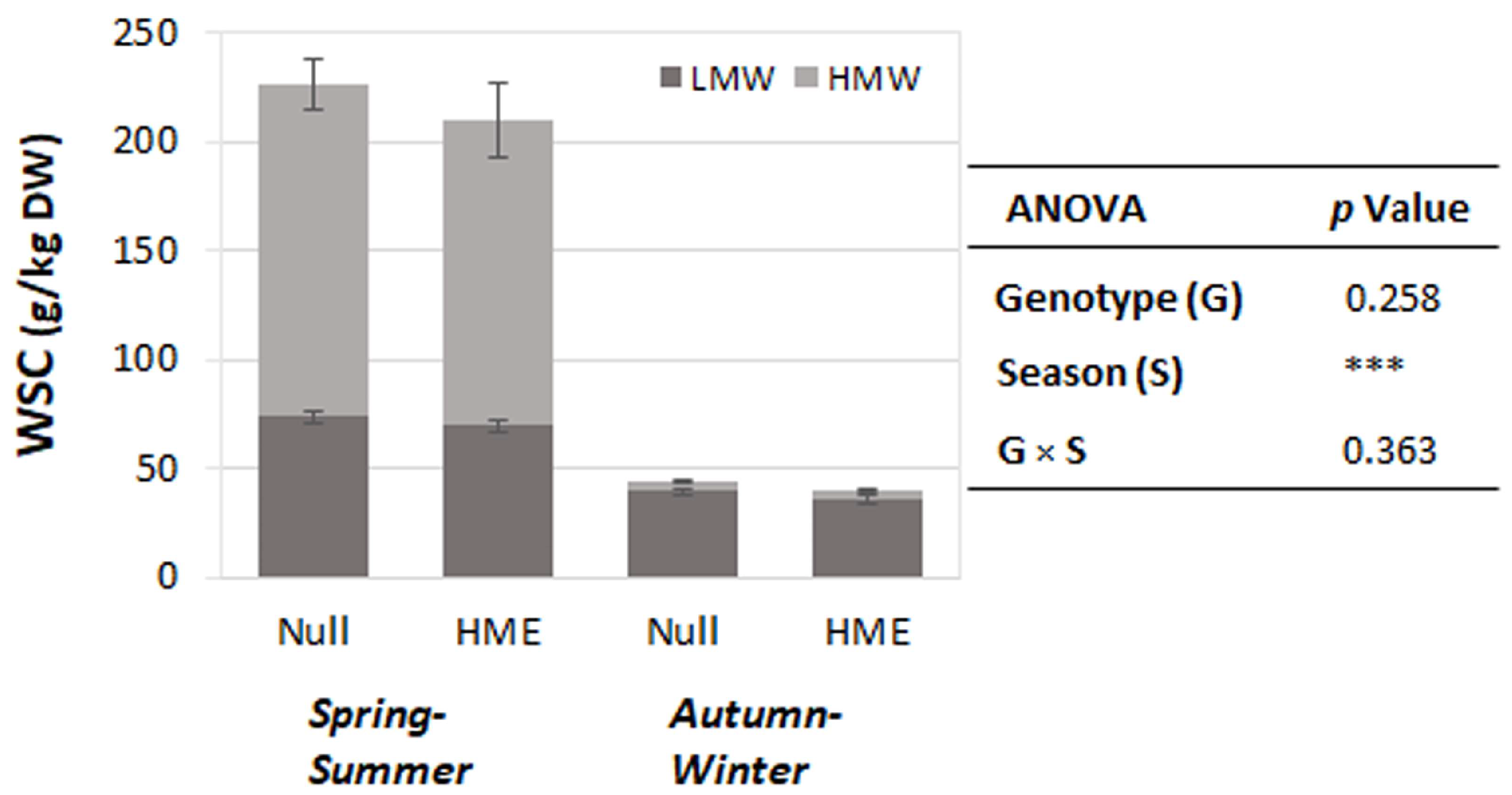

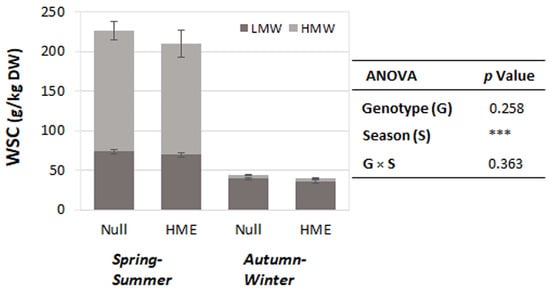

Ryegrass herbage was harvested in the morning, specifically between 9 and 10:30 am. WSC content during this period was relatively low in autumn–winter, with greater accumulation of high-molecular-weight WSCs across both genotypes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Water-soluble carbohydrate (WSC) content in two genotypes across seasonal periods. Stacked bars show mean WSC content (g/kg dry weight) ± standard error of the mean for low molecular weight (LMW, dark grey) and high molecular weight (HMW, light grey) fractions in null and HME genotypes during spring–summer and autumn–winter seasons. Analysis of variation (ANOVA) indicates highly significant seasonal effects (*** p < 0.001), with no significant genotype effects (p = 0.258) or genotype × season interaction (p = 0.363). Total WSC content was approximately 4–5 times higher during spring–summer compared to autumn–winter periods for both genotypes.

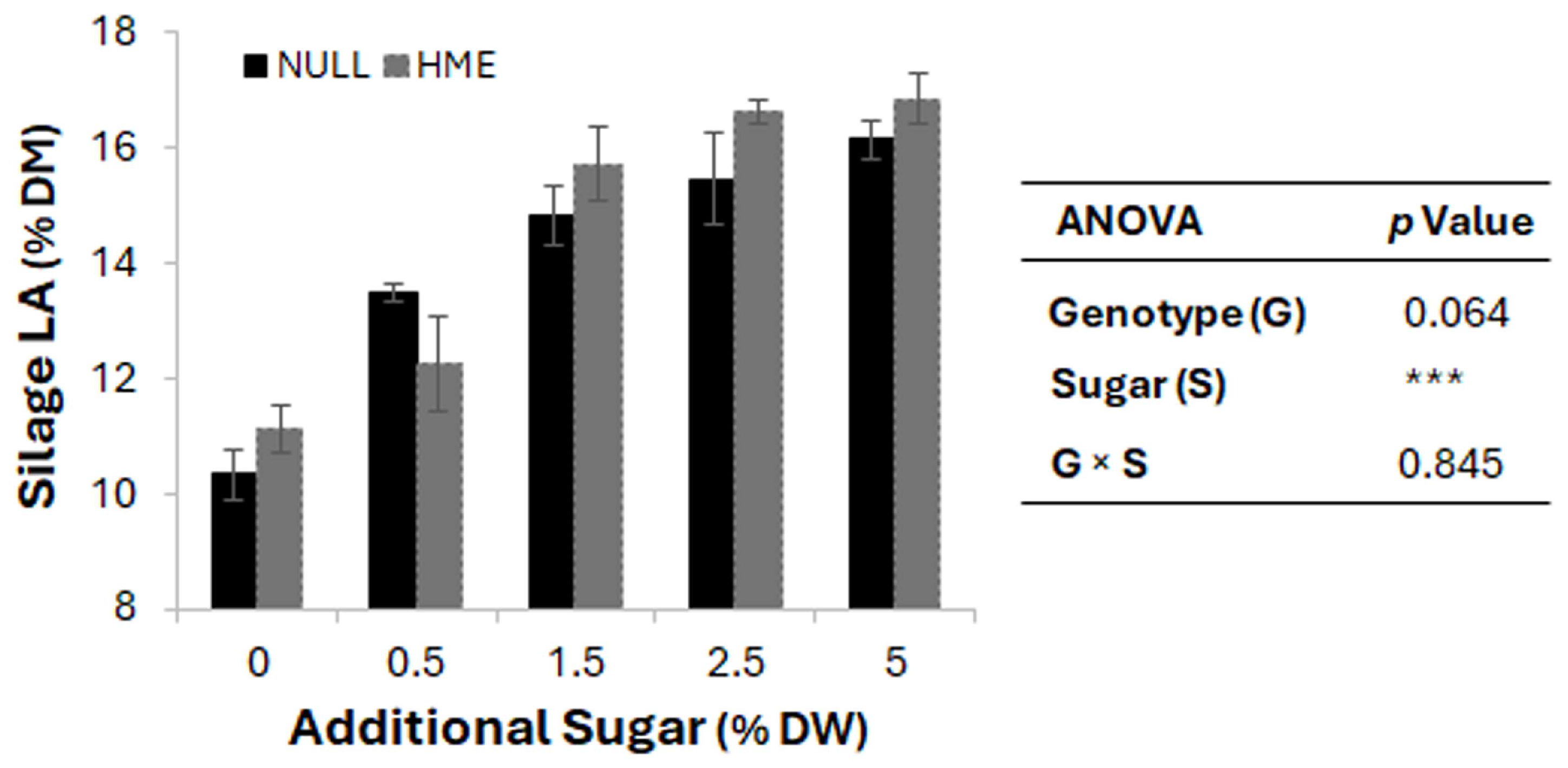

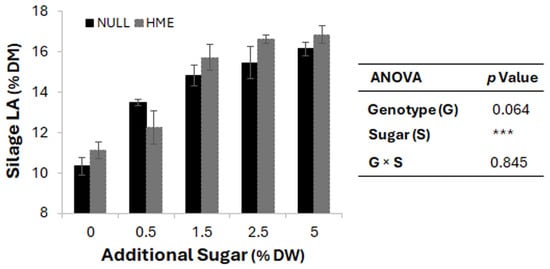

3.4. Effect of Sugar Supplementation on Ensiling

Table sugar was added at 5% of wilted weight to all batches, compensating for seasonal variation in WSC levels and ensuring complete fermentation across all ryegrass material. To evaluate the impact of WSC levels on silage fermentation, an experiment was conducted where null and HME herbage were supplemented with sugar concentrations ranging from 0% to 5% of DM. As shown in Figure 3, increasing sugar levels resulted in a gradual increase in LA content (after 30 days of silage fermentation)—from ~10.5% to 16.5% DM—in both genotypes. HME silage showed numerically higher LA production across all sugar concentrations. Analysis of variance revealed that sugar supplementation rate had a highly significant effect (p < 0.001) on LA production, whereas genotype effect (p = 0.064), and genotype × sugar interaction (p = 0.845) were not significant.

Figure 3.

Effect of additional sugar concentration on silage lactic acid content. Bars represent mean silage lactic acid (LA) percentage dry matter (% DM) ± standard error of the mean for null (black bars) and HME (grey bars) genotypes across increasing sugar concentrations (0, 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, and 5% dry weight) added during the ensiling process. Analysis of variation (ANOVA) shows significant effects of sugar treatment (*** p < 0.001), with marginally significant genotype effects (p = 0.064) and no genotype × sugar interaction (p = 0.845).

3.5. Silage Production and Energy Quality Improvements

While both ryegrass genotypes achieved similar total silage yield (138 kg DM for null vs. 131 kg DM for HME), DM content (~30%), crude protein, N content and silage pH value (~4–4.2), the analysis revealed several significant genotype-specific differences (Table 2).

FA content was averaged from 12 randomly selected silage batches (50–80 days after silo packing). The FA content was significantly higher in the HME genotype than the null (4.85% vs. 2.75% DM, p < 0.001), representing a 76% increase (Table 2). Calculation details are provided in the footer of Table 2. Carbon content was also slightly, but significantly, elevated in HME (43.3% vs. 42.5% DM, p < 0.05). GE was also significantly greater (18.1 vs. 17.5 MJ/kg DM, p < 0.001). Differences in DMD and NDF were, however, not statistically significant. Both predicted ME improvements were numerically higher in HME silage, although the predicted ME did not differ significantly between HME and null silage (p = 0.7035 for predicted ME1 and p = 0.0581 for predicted ME2, Table 2).

3.6. Fermentation Characteristics

The acetic acid (HAc) content was significantly lower in HME silage (0.83% DM) compared to null silage (1.58% DM; p < 0.001) (Table 2). This value in HME silage falls slightly below the typical range for HAc concentrations in grass forage (1–3%) [37]. Butyric acid in both silages was within the expected range of 0.1–0.5% DM, and no other VFAs were detected in the silage of either genotype.

LA levels and pH did not differ significantly between genotypes. Other fermentation and compositional parameters, including BC and NH4+–N, also showed no significant differences between the two genotypes (Table 2).

3.7. Silage Quality After Long-Term Storage

Storage duration influenced silage fermentation and composition (Table 3). DM content remained relatively stable over time, and pH values across all storage periods stayed within the optimal range for both genotypes, consistently below 4.1.

HME silage maintained significantly higher FA levels than null silage at both 52 and 342 DAS, with a stable difference of 2.1–2.4% DM (Table 3). HME silage contained 5.75% FA compared to 3.59% in null silage; after 342 DAS, the difference was 5.17% vs. 2.80% DM. The FA loss between 52 and 342 DAS was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

FA composition was significantly affected by genotype and storage duration. At 52 DAS, HME silage had higher proportions of C18:1 (8.90% vs. 0.72%) and C18:2 (21.0% vs. 6.97%) and lower proportions of C16:0 (11.2% vs. 14.8%) and C18:3 (55.6% vs. 74.0%) compared with null silage. By 342 DAS, null silage showed increased C16:0, C16:1, and C18:0 and reduced C18:3, while HME silage maintained a relatively stable FA profile with enrichment of C18:1 and C18:2.

GE was significantly higher in HME compared to the null at both storage intervals (Table 3). DMD increased significantly in HME compared to null after prolonged storage, resulting in higher predicted ME for HME silage (10.8–11.6 MJ/kg DM) than null silage (10.5–10.8 MJ/kg DM; p < 0.05).

HAc levels were consistently lower in HME silage across storage periods. BC declined over time in both silages, from ~775–838 mmol/kg DM at 52 days to ~404–417 mmol/kg DM after 342 days. LA content declined from 16.2% to 10.8% DM in null silage and from 16.9% to 11.7% DM in HME silage.

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility of Producing GM Ryegrass Silage Under Containment

This study demonstrates the practical feasibility of producing and ensiling GM HME perennial ryegrass under physical containment over an extended production period. Despite regulatory constraints that preclude field cultivation, repeated greenhouse-based production cycles generated sufficient biomass to support ensiling, compositional characterization, and downstream material requirements. Unlike field-grown ryegrass, plants cultivated in controlled environments are subject to conditions that may affect key fermentation parameters such as DM, BC, and WSC levels. BC describes how resistant forage is to pH change, and forages with higher BC require more acid production (and thus more WSC) to achieve preservation pH [37]. Additionally, harvesting in the morning, especially during autumn–winter when sunrise is delayed, may limit WSC accumulation and influence fermentation potential [25]. Silage quality was considered acceptable, as indicated by pH values within the target range, high LA concentrations, and VFA profiles consistent with successful fermentation. This quality was achieved consistently across genotypes and storage durations, indicating that containment-compatible ensiling protocols can preserve forage material suitable for subsequent animal-based studies.

The capacity to accumulate biomass across multiple harvests and greenhouse rounds is particularly relevant for jurisdictions operating under strict GM containment regulations [10]. By enabling the production and preservation of GM forage material in a compact and stable format, the workflow presented here addresses a key translational barrier between plant biotechnology development and animal evaluation [38,39,40]. Few studies have progressed genetically modified forage traits beyond molecular or agronomic assessment to controlled animal evaluation, particularly under containment conditions [2]. Although GM crops such as herbicide-tolerant maize and soybean have been evaluated in animal feeding studies for safety and nutritional equivalence, the literature on transgenic forage plants evaluated in livestock feeding experiments remains limited [2,41]. This relative paucity of controlled trials reinforces the translational significance and novelty of the present study.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that these results demonstrate technical feasibility, fermentation performance, and compositional stability of HME ryegrass during ensiling and extended storage; they do not fully simulate commercial field production systems. Under field conditions, environmental variability may result in greater or lesser responses in traits such as biomass production, WSC accumulation, and FA content, which could in turn influence fermentation dynamics and nutritional outcomes [18,37].

4.2. Seasonal Variation, Pot Limitation, and Repeated Harvesting Effects

The decline in biomass production across seven sequential harvests, including reduced tillering rate, suggests increasing constraints on water and nutrient availability as roots approached pot capacity [42]. Increasing pot volume partially alleviated these constraints; however, further increases were logistically impractical, and pot depth may also have contributed to growth limitation [43]. These constraints are inherent to long-term greenhouse cultivation and were accounted for statistically as temporal, not independent, observations. Additionally, the higher biomass observed during the spring–summer period may reflect more favorable growing conditions, including higher temperatures and longer daylight hours; however, these factors were not directly tested in the present study [44].

The progressive decline in herbage FA concentrations in HME is likely attributable to reaching its pot capacity limit faster than the null plants, consistent with the higher relative root growth rates previously reported for HME ryegrass under standard irradiance [23]. The confined vessel volume used in this study likely imposed limitations on root development, with potential downstream effects on nutrient acquisition, particularly nitrogen uptake [42,43]. Restricted nitrogen availability can influence carbon–nitrogen balance and may constrain lipid biosynthesis, especially in genotypes with elevated carbon demand such as HME lines. In fact, FA accumulation in ryegrass has been shown to respond positively to nitrogen supply [45], given the increased metabolic investment in FA synthesis in HME plants. Together, these findings indicate that pot volume represents a practical constraint in contained HME production rather than a limitation of the genetic trait itself.

Future studies could mitigate these constraints through optimized fertigation strategies, more frequent nutrient replenishment, or the use of soilless cultivation systems to better sustain nutrient availability and root function. Such approaches would allow clearer separation of genotype-driven metabolic effects from artefacts associated with physical root confinement [46,47].

4.3. Seasonal Effects on Water-Soluble Carbohydrates and Ensiling Outcomes

Ryegrass foliage exhibits pronounced diurnal and seasonal fluctuations in non-structural carbohydrates, predominantly WSC, driven by irradiance and temperature [48]. In this study, ryegrass herbage was harvested in the morning (9–10:30 am) to maximize leaf FA content [23], but this timing coincided with relatively low WSC concentrations during autumn–winter, especially under delayed sunrise conditions.

Seasonal differences in WSC content (approximately 50 g kg−1 DM in autumn–winter versus 200–250 g kg−1 DM in spring–summer) have important implications for silage fermentation. WSC availability is a primary determinant of LA production and pH decline during ensiling [49,50,51]. In low-WSC conditions, sugar supplementation or microbial inoculation can improve fermentation outcomes and reduce the risk of spoilage [52,53]. The similar response of both genotypes to sugar supplementation observed here is consistent with previous studies demonstrating substrate-driven enhancement of LAB activity [54,55].

High moisture content and low sugar content can also promote the growth of undesirable microorganisms early in the ensiling process, leading to compromised fermentation quality [54]. It should be noted that the addition of table sugar to promote fermentation complicates direct interpretation of GE and ME differences between genotypes, as the sugar contributed to the overall energy content of both silages. Comparisons of energy content should be interpreted with caution, particularly where GE or ME are discussed, as the addition of external sugar during ensiling may influence absolute energy values. However, the consistently elevated FA content in HME silage—which was not influenced by sugar addition—represents a genuine genotypic difference and may support potential gains in animal productivity through enhanced energy density and altered rumen fermentation [56,57].

4.4. Fatty Acid Retention in HME and Compositional Stability During Ensiling and Storage

Extended storage influenced silage fermentation quality and nutrient composition [37]. The stable DM and pH values indicate that fermentation and preservation were successful across both genotypes. The higher GE and DMD in HME silage translated to increased predicted ME, highlighting the potential nutritional benefits of HME forage even after prolonged storage.

Consistently lower HAc levels in HME silage, alongside the observed decline in BC over time for both silages, indicate that HME modifications did not adversely affect fermentation stability.

The central objective of this study was to determine whether elevated lipid content in HME ryegrass could be retained following ensiling and extended storage under containment. The pronounced differences in FA composition, with HME silage enriched in unsaturated C18:1 and C18:2 and lower saturated FA proportions, suggest that HME modifications confer greater FA stability during storage, whereas polyunsaturated FAs in null silage were preferentially degraded or oxidized over time. Observed shifts in FA composition during storage were consistent with those reported for conventional ryegrass silage [58] and did not negate the lipid advantage of the HME genotype.

FA class distribution was characterized but not optimized, and no inference is made regarding the mitigation efficacy of specific FA classes. Although polyunsaturated and medium-chain FAs have been associated with CH4 suppression [6,59,60], the present study was not designed to assess mitigation outcomes.

Over the two assessed storage durations, while these observations describe trends in fatty acid composition, the underlying mechanisms cannot be determined from only two time points. We acknowledge that more frequent sampling over storage would be required to draw mechanistic conclusions. Such changes in plant FA composition can vary with storage conditions and duration, and observed trends in individual FA classes from only two times points cannot be mechanistically definitive [61].

Rather than implying a mechanistic “protection” against lipid degradation, these results demonstrate relative compositional stability of HME silage with enhanced energy-related traits without compromising silage preservation or quality during extended storage. Elevated FA retention may influence palatability, energy density, and feed value through known effects of lipids on aroma, flavor, and rumen metabolism [5,7,62,63].

4.5. Energy Content, Fermentation Profile, and Implications for Downstream Studies

Extended ensiling can alter fiber structure and protein availability through partial proteolysis and cell-wall modification [64,65]. Although NDF concentrations remained unchanged, the 4% increase in DMD observed in HME silage after prolonged storage suggests modest improvements in degradability, potentially linked to altered carbon partitioning in HME plants [25,66,67].

HME silage exhibited significantly lower HAc concentrations than null silage, while butyric acid remained within acceptable ranges for both genotypes [37]. These differences may reflect altered microbial fermentation dynamics associated with higher lipid content, as certain FAs can inhibit HAc-producing microorganisms [68]. Despite this difference, LA levels, pH and other key fermentation parameters remained stable across storage durations, indicating effective fermentation and long-term stability.

The advantageous characteristics of HME silage for at least a year storage highlights the practical value of the trait. The higher GE and ME contents of HME silage are consistent with previous reports of increased energy density in HME ryegrass [1,4], supporting its suitability for controlled animal evaluation. These findings suggest that HME modification did not adversely impact silage quality or nutritive value. The observed improvements appear to be specifically associated with enhanced energy-related traits rather than broad alterations to fermentation stability or the nutritional profile.

However, sugar supplementation during ensiling across treatments may influence the absolute values of GE and predicted ME reported here. While this approach does not affect the validity of the relative energy differences observed between HME and null genotypes, the absolute ME values should not be interpreted as directly representative of commercial silage systems. Future studies evaluating unsupplemented silages under field-relevant conditions will be important to validate the practical impact of HME forage on energy supply.

4.6. Relevance to Sheep Feeding Trial and Scope Limitations

The silage production system generated approximately 130 kg DM each of HME and null material, which was subsequently used in a controlled sheep feeding trial conducted in AgResearch’s respiration chamber facilities (24 sheep chambers) [69,70]. Based on the FA enrichment levels observed here, empirical prediction equations suggested a theoretical potential reduction in enteric CH4 emissions of approximately 10% [6]. These estimates are derived from empirical models and do not account for ruminal microbial adaptation, voluntary intake responses, or broader diet composition, all of which are known to influence in vivo methane emissions [71].

However, the animal performance and CH4 emission outcomes of that trial are reported separately and are not evaluated here. This study does not attempt to link compositional differences to animal intake, productivity, or CH4 emissions. Such responses depend on complex interactions involving rumen adaptation, intake regulation, and diet digestibility and must be evaluated directly in vivo [6,72].

4.7. Methodological Considerations and Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Pot-based cultivation constrained root volume and may have influenced growth patterns relative to field-grown ryegrass [42,43,73]. As described in Section 2.6, sugar was added to standardize fermentation in small-scale silos under containment conditions. While this approach alters the fermentation environment relative to commercial systems, it may partially obscure intrinsic genotype-related differences in silage composition to be evaluated [74,75]. Only two storage durations were evaluated, limiting inference regarding longer-term stability beyond the periods assessed. In addition, repeated harvests represent temporal measures rather than independent biological replicates and were treated accordingly in the statistical analysis.

It is also important to note that the current analysis was conducted on a subset of 12 (6 HME, and 6 null) silage batches out of total 56 batches, which may limit the generalizability of the results, given the known variability in silage composition across batches and storage conditions [76]. From a feeding trial perspective, it is essential to confirm that these compositional enhancements translate to measurable improvements in animal performance, and particularly reductions in enteric CH4 emissions, as such responses depend on complex interactions between diet composition, intake regulation, and rumen [6,72]. Furthermore, any potential differences in cultivation inputs, management requirements, or environmental tolerances between the HME and null should be assessed to evaluate the broader economic viability and scalability of HME implementation in commercial production systems [5].

Despite these constraints, the workflow reliably generated well-characterized GM silage of acceptable quality across multiple production cycles. The limitations outlined here reflect practical realities of contained GM research and do not detract from the primary objective of enabling downstream animal-based evaluation.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study systematically demonstrates, for the first time, that multiple cycles of cultivation under contained conditions, ensiling, and prolonged storage do not compromise the lipid advantage of the HME ryegrass genotype. HME silage maintained enhanced FA content, energy density, and stable fermentation characteristics across storage periods, without adversely affecting key nutritional parameters. These findings confirm the robustness of HME traits under controlled production and storage conditions and highlight the potential for developing energy-dense forage for ruminant nutrition. While the workflow established here provides a reliable framework for investigating HME forage traits and silage performance, it has also been successfully applied in an in vivo feeding trial (results published separately), demonstrating practical applicability.

Importantly, this work addresses a key translational gap in GM forage research. The ensiling-based approach provides a practical and scalable means of preserving characterized GM biomass for subsequent in vivo evaluation, remains compliant with regulatory requirements, and is readily adaptable to other GM forage systems requiring contained biomass production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.J.C. and N.J.R. Formal analysis: S.W., P.A. and A.P. Funding acquisition: L.J.C. and N.J.R. Investigation: S.W. and A.P. Methodology: All Authors. Writing—original draft: S.W. Writing—review and editing: S.W., J.K., K.A.R., A.J., L.J.C. and N.J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was funded by the AgResearch Strategic Science Investment Fund through the PRJ0522733 research program.

Informed Consent Statement

Ethics, Consent to Participate, and Consent to Publish declarations: not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jakob Kleinmans was employed by the company Nutriassist Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Beechey-Gradwell, Z.; Winichayakul, S.; Roberts, N. High lipid perennial ryegrass growth under variable nitrogen, water, and carbon dioxide supply. J. N. Z. Grassl. Assoc. 2018, 80, 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, G.; Winichayakul, S.; Roberts, N. Nutritional enhancement of animal feed and forage crops via genetic modification. J. R. Soc. N.Z. 2024, 55, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooney, L.J.; Beechey-Gradwell, Z.; Winichayakul, S.; Ricardson, K.A.; Crowther, T.; Anderson, P.; Scott, R.W.; Bryan, G.; Roberts, N.J. Changes in leaf-level nitrogen partitioning and mesophyll conductance deliver increased photosynthesis for Lolium perenne leaves engineered to accumulate lipid carbon sinks. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 641822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winichayakul, S.; Scott, R.; Roldan, M.; Hatier, J.-H.B.; Livingston, S.; Cookson, R.; Curran, A.C.; Roberts, N.J. In vivo packaging of triacylglycerols enhances Arabidopsis leaf biomass and energy density. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beechey-Gradwell, Z.; Kadam, S.; Bryan, G.; Cooney, L.; Nelson, K.; Richardson, K.; Cookson, R.; Winichayakul, S.; Reid, M.; Anderson, P.; et al. Lolium perenne engineered for elevated leaf lipids exhibit greater energy density in filed canopies under defoliation. Field Crops Res. 2022, 275, 108340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, K.A.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Abadalla, A.L.; Alvarez, C.; Arndt, C.; Becquet, P.; Benchaar, C.; Berndt, A.; Mauricio, R.M.; McAllister, T.A.; et al. Invited review: Current enteric methane mitigation options. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9276–9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winichayakul, S.; Beechey-Gradwell, Z.; Muetzel, S.; Molano, G.; Crother, T.; Lewis, S.; Xue, H.; Bryan, G.; Roberts, N.J. In vitro gas production and rumen fermentation profile of fresh and ensiled genetically modified high metabolizable energy ryegrass. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 2405–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukrouh, S.; Mnaouer, I.; de Souza, P.M.; Hornick, J.-L.; Nilahyane, A.; El Amiri, B.; Hirich, A. Microalgae supplementation improves goat milk composition and fatty acid profile: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2025, 68, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giagnoni, G.; Lund, P.; Johansen, M.; Weisbjerg, M.R. Effect of dietary fat source and concentration on feed intake, enteric methane, and milk production in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, T. New Zealand’s three-decade ban on genetic modification, explained. AgResearch News 2023. Available online: https://www.agresearch.co.nz/news/new-zealands-three-decade-ban-on-genetic-modification-explained/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Monroe, C.F.; Hilton, J.H.; Hodgson, R.E.; King, W.A.; Krauss, W.E. The loss of nutrients in hay and meadow crop silage during storage. J. Diary Sci. 1946, 29, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coblentz, W.K.; Akins, M.S. Silage review: Recent advances and future technologies for baled silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4075–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamudio, D.; Killerby, M.A.; Charley, R.C.; Chevaux, E.; Drouin, P.; Schmidt, R.J.; Bright, J.; Romero, J.J. Factors affecting nutrient losses in hay production. Grass Forage Sci. 2024, 79, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Novachem Agrichemical Manual 2008 & 2009. Agrimedia Ltd., Christchurch. Web Version. Available online: https://www.novachem.co.nz/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Sun, X.; Luo, N.; Longhurst, B.; Luo, J. Fertiliser nitrogen and factors affecting pasture responses. Open Agric. J. 2008, 2, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dairynz.co.nz. 2024. Available online: https://www.dairynz.co.nz/feed/pasture-species/ryegrass/#:~:text=Production%20of%20perennial%20ryegrass%2Dbased,ryegrass%20pastures%20can%20last%20indefinitely (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Goldammer, T. Greenhouse Management: A Guide to Operations and Technology, 3rd ed.; Apex Publishers USA: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2025; ISBN 979-8-89766-348-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes, T.F.; Daniel, J.L.P.; Adesogan, A.T. Silage review: Unique challenges of silages made in hot and cold regions. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4001–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoedtke, S.; Zeyner, A. Comparative evaluation of laboratory-scale silages using standard glass jar silages or vacuum-packed model silages. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 841–849. [Google Scholar]

- Serva, L.; Andrighetto, I.; Segato, S.; Marchesini, G.; Chinello, M.; Magrin, L. Assessment of maize silage quality under different pre-ensiling conditions. Data 2023, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.E.; Merry, R.J.; Davies, D.R.; Kell, D.B.; Theodorou, M.K.; Griffith, G.W. Vacuum packing: A model system for laboratory-scale silage fermentations. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auldist, M.J.; Marett, L.C.; Greenwood, J.S.; Hannah, M.; Jacobs, J.L.; Wales, W.J. Effects of different strategies for feeding supplements on milk production responses in cows grazing a restricted pasture allowance. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, W.P.; Tebbe, A.W. Estimating digestible energy values of feeds and diets and integrating those values into net energy systems. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2018, 3, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roughan, P.G.; Holland, R. Predicting in-vivo digestibility of herbages by exhaustive enzymic hydrolysis of cell walls. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1977, 28, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browse, J.; McCourt, P.J.; Somerville, C.R. Fatty acid composition of leaf lipids determined after combined digestion and fatty acid methyl ester formation from fresh tissue. Anal. Biochem. 1986, 152, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winichayakul, S.; Macknight, R.; Le Lievre, L.; Beechey-Gradwell, Z.; Lee, R.; Cooney, L.; Xue, H.; Crowther, T.; Anderson, P.; Richardson, K.; et al. Insight into the regulatory networks underlying the high lipid perennial ryegrass growth under different irradiances. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, A.; Rasmussen, S.; Xue, H.; Newman, J.; Anderson, C.; Cosgrove, G. Some ‘high sugar grasses’ don’t like it hot. Proc. N. Z. Grassl. Assoc. 2004, 66, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermyn, M.A. New method for determining ketohexoses in the presence of aldohexoses. Nature 1956, 177, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachiya, T.; Okamoto, Y. Simple spectroscopic determination of nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium in Arabidopsis thaliana. Bio-Protocol 2017, 7, e2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bräutigam, A.; Gagneul, D.; Weber, A.P.M. High-throughput colorimetric method for the parallel assay of glyoxylic acid and ammonium in a single extract. Anal. Biochem. 2007, 362, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidotti, M.; Fabbri, D.; Torri, C.; Piccinini, S. Determination of volatile fatty acids in digestate by solvent-extraction with dimethyl carbonate and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1034, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borshchevskaya, L.N.; Gordeeva, T.L.; Kalinina, N.; Sineokii, S.P. Spectrophotometric determination of lactic acid. J. Anal. Chem. 2016, 71, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, J.; Cherney, D. Assessing Silage Quality. Silage Sci. Technol. 2003, 42, 141–198. [Google Scholar]

- Playne, M.; McDonald, P. The buffering constituents of herbage and of silage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1966, 17, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, X.A.; Donaldson, L.; Correa-Cano, M.E.; Evans, J.; Fisher, D.; Goodwin, C.E.D.; Robinson, B.S.; Hodgson, D.J.; Inger, R. A brief introduction to mixed effects modelling and multi-model inference in ecology. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepho, H.P.; Buchse, A.; Emrich, K. A Hitchhiker’s guide to mixed models for randomized experiments. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2003, 189, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L., Jr.; Shaver, R.D.; Grant, R.J.; Schmidt, R.J. Silage Review: Interpretation of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4020–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA GMO Panel Working Group on Animal Feeding Trials. Safety and nutritional assessment of GM plants and derived food and feed: The role of animal feeding trials. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, S2–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, C.; Macedo, M.; Buha, T.; De Donato, M.; Costas, B.; Mancera, J.M. Genetically modified animal-derived products: From regulations to applications. Animals 2025, 15, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, S.J. Regulatory barriers to improving global food security. Glob. Food Sec. 2020, 26, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, R. The impact of Genetically Modified (GM) crops in modern agriculture: A review. GM Crops Food. 2017, 8, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindh, M.; Hoeber, S.; Weih, M.; Manzoni, S. Interactions of nutrient and water availability control growth and diversity effects in a Salix two-species mixture. Ecohydrology 2022, 15, e2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Bühler, J.; Van Dusschoten, D.; Climent, J.; Postma, J.A. Pot size maters: A meta-analysis of the effects of rooting volume on plant growth. Funct. Plant Biol. 2012, 39, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Niklas, K.J.; Reich, P.B.; Oleksyn, J.; Poot, P.; Mommer, L. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: Meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beechey-Gradwell, Z.; Cooney, L.; Winichayakul, S.; Andrews, M.; Hea, S.Y.; Crowther, T.; Roberts, N. Storing carbon in leaf lipid sinks enhances perennial ryegrass carbon capture especially under high N and elevated CO2. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 2351–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuxun, A.; Xiang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Son, J.E.; Yamada, M.; Yamada, S.; Tagawa, K.; Baiyin, B.; Yang, Q. Soilless cultivation: Precise nutrient provision and growth environment regulation under different substrates. Plants 2025, 14, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fussy, A.; Papenbrock, J. An overview of soil and soilless cultivation techniques—Chances, challenges and the neglected question of sustainability. Plants 2022, 11, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, L.A.; Edwards, G.R.; Bryant, R.H. Diurnal changes in the nutritive composition of four forage species at high and low N fertiliser. J. N. Z. Grassl. Assoc. 2017, 79, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P.; Henderson, A.R. Determination of water-soluble carbohydrates in grass. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1964, 15, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, D.R.; Henderson, A.; Pettersson, K.O.; Lowe, J.F. The effect of addition of sugar and inoculation with two commercial inoculants on the fermentation of lucerne silage in laboratory silos. Grass Forage Sci. 1986, 41, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.J.; Zhang, K.; Ji, R.X.; Chen, X.W.; Wang, J.; Raja, I.H.; Shan, A.S.; Zhang, S. Assessment of nutritional value, aerobic stability and measurement of in vitro fermentation parameters of silage prepared from several leguminous plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, É.B.; Costa, D.M.; Santos, E.M.; Moyer, K.; Hellings, E.; Kung, L., Jr. The effects of Lactobacillus hilgardii 4785 and Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 on the microbiome, fermentation, and aerobic stability of corn silage ensiled for various times. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 104, 10678–10698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Wang, L.; Yu, Z. Effects of different moisture levels and additives on the ensiling characteristics and in vitro digestibility of Stylosanthes silage. Animals 2022, 12, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, C.L.S.; Carvalho, B.F. Silage fermentation-updates focusing on the performance of micro-organisms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 966–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; MacAdam, J.W.; Zhang, Y. Interaction between plants and epiphytic lactic acid bacteria that affect plant silage fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1164904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.J.C.; Grigoletto, N.T.S.; Poletti, G.; Chesini, R.G.; Diepersloot, E.C.; Takiya, C.S.; Ferraretto, L.F.; Rennó, F.P. Impact of decreasing undigested neutral detergent fiber concentration in corn silage–based diets for dairy cows: Nutrient digestibility, ruminal fermentation, feeding behavior, and performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 8462–8475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, W.P. Predicting energy values of feeds. J. Dairy Sci. 1993, 76, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgersma, A.; Ellen, G.; van der Horst, H.; Muuse, B.G.; Boer, H.; Tamminga, S. Comparison of the fatty acid composition of fresh and ensiled perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.), affected by cultivar and regrowth interval. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2003, 108, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Torres, J.N.; Ramírez-Bribiesca, J.E.; Bautista-Martínez, Y.; Crosby-Galván, M.M.; Granados-Rivera, L.D.; Ramírez-Mella, M.; Ruiz-González, A. Stability and effects of protected palmitic acid on in vitro rumen degradability and fermentation in lactating goats. Fermentation 2023, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, K.A.; McGinn, S.M.; Petir, H.V. Methane abatement strategies for cattle: Lipid supplementation of diets. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 87, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdiani, N.; Kolahi, M.; Javaheriyan, M.; Sabaeian, M. Effect of storage conditions on nutritional value, oil content, and oil composition of sesame seeds. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.; Jeronimo, E.; Bessa, R.; Cabrita, A.R. Effect of ensiling and silage additives on fatty acid composition of ryegrass and corn experimental silages. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.A.; Tewoldebrhan, T.A.; Zom, R.L.G.; Cone, J.W.; Hendriks, W.H. Effect of corn silage harvest maturity and concentrate type on milk fatty acid composition of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Kung, L., Jr. Short communication: The effects of dry matter and length of storage on the composition and nutritive value of alfalfa silage. J. Diary Sci. 2016, 99, 5466–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordo, A.; Hernando, B.; Artajona, J.; Fondevila, M. In vitro study of the effect of ensiling length and processing on the nutritive value of maize silages. Animals 2023, 13, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winichayakul, S.; Roberts, N. Toward sustainable crops: Integrating vegetative (non-seed) lipid storage, carbon-nitrogen dynamics, and redox regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1589127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winichayakul, S.; Xue, H.; Richardson, K.A.; Maher, D.; Reid, M.; Robert, N. Lipid storage in green tissues alters redox homeostasis, malate metabolism, phospholipids, and nitrogen partitioning in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 227, 110144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhou, H. Effects of ensiling processes and antioxidants on fatty acid concentrations and compositions in corn silages. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, A.; Molano, G.; Sandoval, E.; Taylor, P.S.; Antwi, C.; Olinga, S.; Cosgrove, G.P. Methane emissions differ between sheep offered a conventional diploid, a high-sugar diploid or a tetraploid perennial ryegrass cultivar at two allowances at three times of the year. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 58, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinares-Patiño, C.; Hunt, C.; Martin, R.; West, J.; Lovejoy, P.; Waghorn, G. Chapter 1: New Zealand Ruminant methane measurement centre, AgResearch, Palmerston North. In Technical Manual on Respiration Chamber Design; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry: Wellington, New Zealand, 2024; Available online: https://www.globalresearchalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/GRA-MAN-Facility-BestPract-2012-ch13.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Moraes, L.; Strathe, A.B.; Fadel, J.G.; Casper, D.P.; Kebreab, E. Prediction of enteric methane emissions from cattle. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 2140–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, C.; Beauchemin, K.A. Can enteric methane emissions from ruminants be lowered without lowering their production? Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166–167, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.A.; Huws, S.A.; Lister, S.J.; Sanderson, R.; Scollan, N.D. Phenotypic variation and relationships between fatty acid concentrations and feed value of perennial ryegrass genotypes from a breeding population. Agronomy 2020, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan-Smith, J.G. As investigation into palatability as a factor responsible for reduced intake of silage by sheep. Anim. Prod. 1990, 50, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtanen, P.; Khalili, H.; Nousiainen, J.I.; Rinne, M.; Jaakkola, S.; Heikkilä, T.; Nousianen, J. Prediction of the relative intake potential of grass silage by dairy cows. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2022, 73, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borreani, G.; Tabacco, E.; Schmidt, R.J.; Holmes, B.J.; Muck, R.E. Silage review: Factors affecting dry matter and quality losses in silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3952–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.