Abstract

Soil sensors have a vital role in precision agriculture. In smart agriculture, soil moisture sensors, soil temperature–humidity sensors, soil pH sensors, soil nutrient sensors, soil pollutant and pest sensors, and wearable sensors detect data to improve crop yields and advance agricultural development. This paper summarizes the types and applications of the above sensors. Soil sensors serve as the core technological engine of smart agriculture, and this review also illustrates that the integration of the Internet of Things and sensors—including plant wearable sensors, which indirectly reflect soil conditions through plant physiological signals—can simultaneously measure or infer parameters, e.g., moisture, temperature, pH, and nutrients, that play a crucial role in precision agriculture. This paper concludes with the future prospects and challenges of soil sensors in smart agriculture, emphasizing the need to address bottlenecks in data fusion, model optimization, and cost control, as well as to advance the implementation of smart agriculture through the development of standards and ecological construction.

1. Introduction

This systematic literature review synthesizes the latest research progress on soil sensors in smart agriculture, focusing on their performance characteristics, ecological implications, and adoption challenges. It aims to address three core objectives: (1) develop a standardized comparative framework for seven soil sensor types, (2) propose a novel taxonomy linking sensors to ecological sustainability pathways, and (3) identify context-specific gaps and actionable future research directions. These objectives distinguish the review from existing work, which often lacks integrative analysis and context-specific insights.

Soil, as a core component of the Earth’s ecosystem, contains a huge amount of critical information, which has shown immeasurable value in many fields. In the context of agricultural production systems, the physical and chemical properties of soil, such as nutrient abundance, moisture, temperature and humidity dynamics, soil pollution, and pH, are closely related to the growth and development of crops, the final yield level, and the quality of crops. Accurate mastery of such soil information can effectively promote the implementation of precision fertilization strategies and the rational allocation and efficient use of irrigation water resources [1].

However, traditional agricultural development faces a series of serious challenges. The irrational utilization of resources has led to widespread waste, and agricultural surface pollution has exerted greater pressure on the ecological environment, bringing significant uncertainty to the growth and development of crops. In order to effectively address these challenges and guarantee global food security, the development of “smart agriculture” or “precision agriculture” has become an inevitable choice [1].

By integrating sensor technologies, information management systems, advanced agricultural machinery, and precision management strategies, smart agriculture can fully account for various sources of variability and uncertainty in sustainable agricultural systems, thereby enabling the efficient utilization of agricultural resources and steady improvements in crop yields [2]. Soil collection sensors, as the core monitoring technology, can accurately monitor the soil’s moisture content, temperature, pH, nutrient concentration, and other physicochemical signals in real time, and at the same time dynamically monitor the growth and health of plants. These data are irreplaceably important for optimizing the crop growth environment, resisting biotic stresses (e.g., pest infestation) and abiotic stresses (e.g., drought, salinity, etc.), as well as improving crop yields [3].

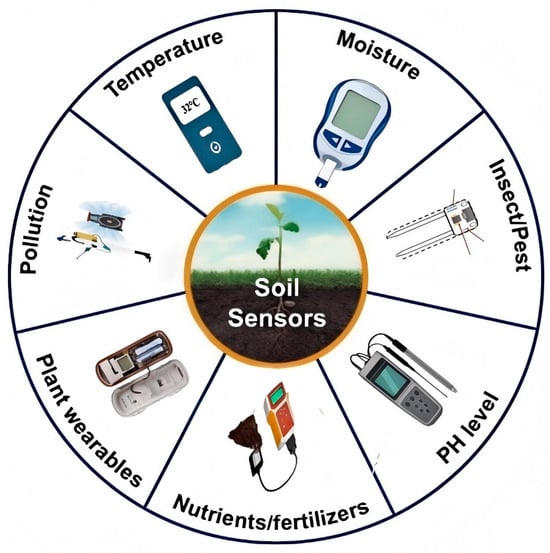

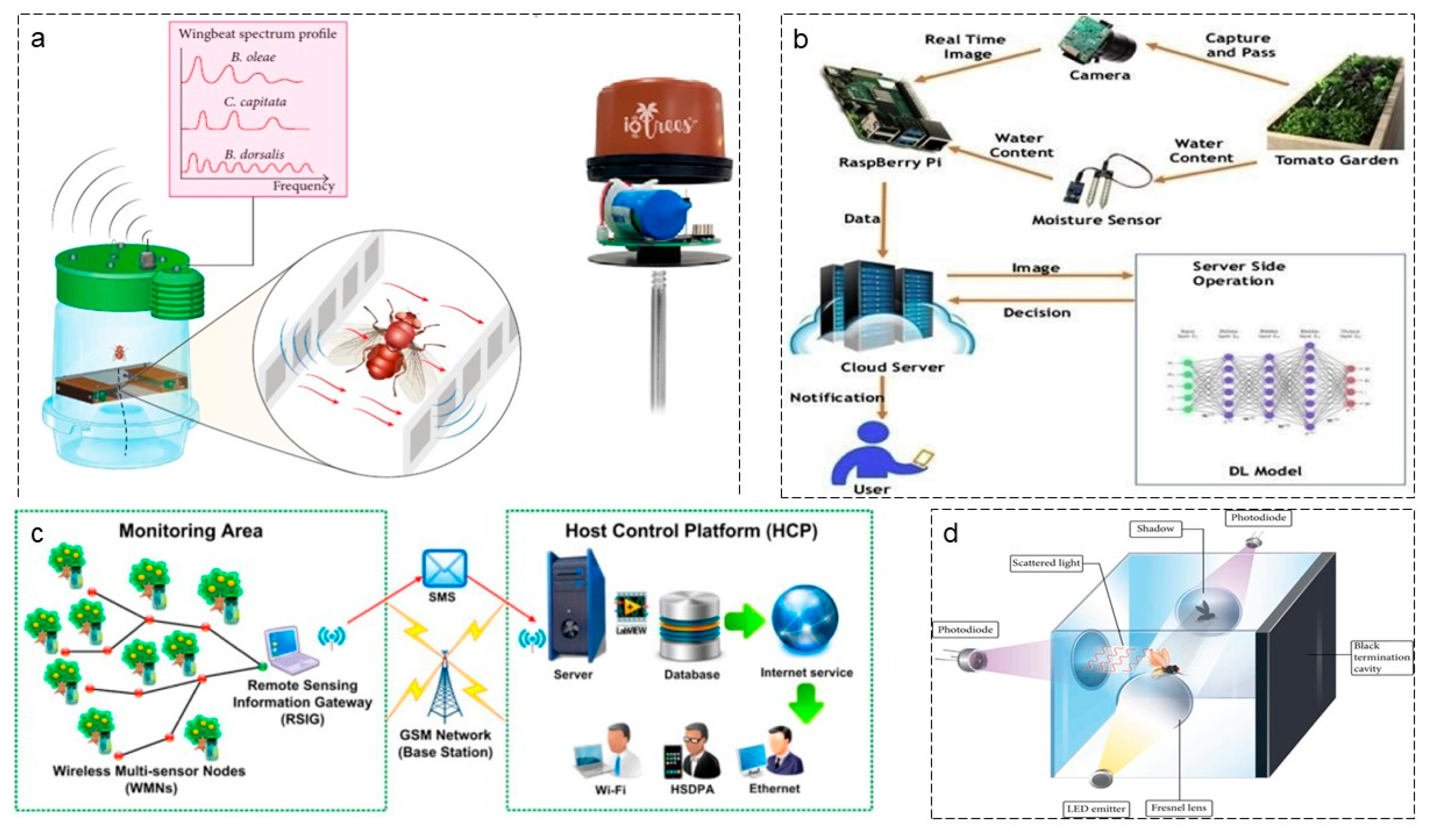

However, traditional soil monitoring means have inherent drawbacks, such as a long sampling period and low spatial resolution, which make it difficult to meet the stringent demand for high spatial and temporal resolution monitoring of soil information in precision agriculture. Therefore, as shown in Figure 1, the development of new soil collection sensors with high spatial and temporal resolution monitoring capability has become a key task and core driving force to promote the sustainable development of smart agriculture [3].

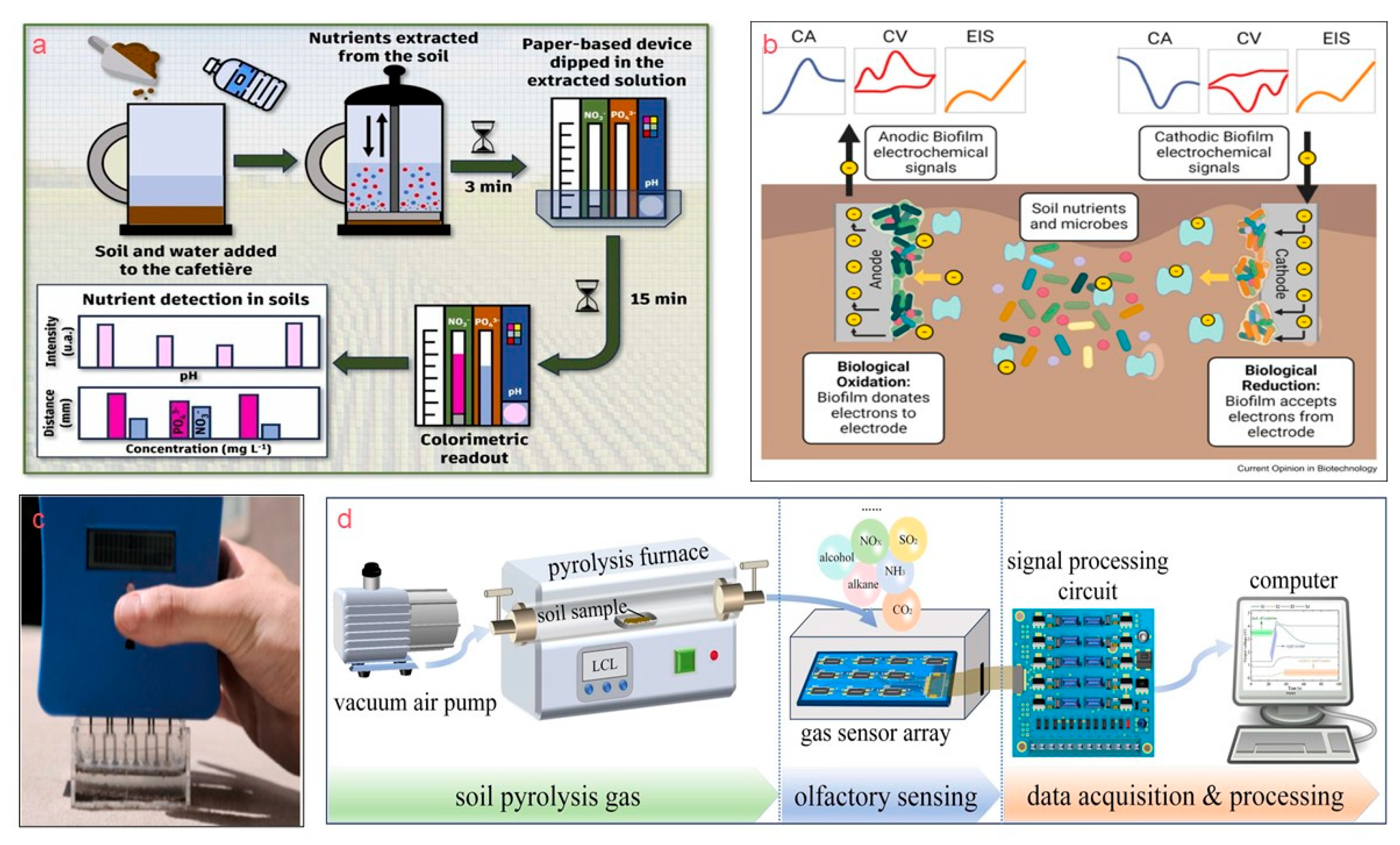

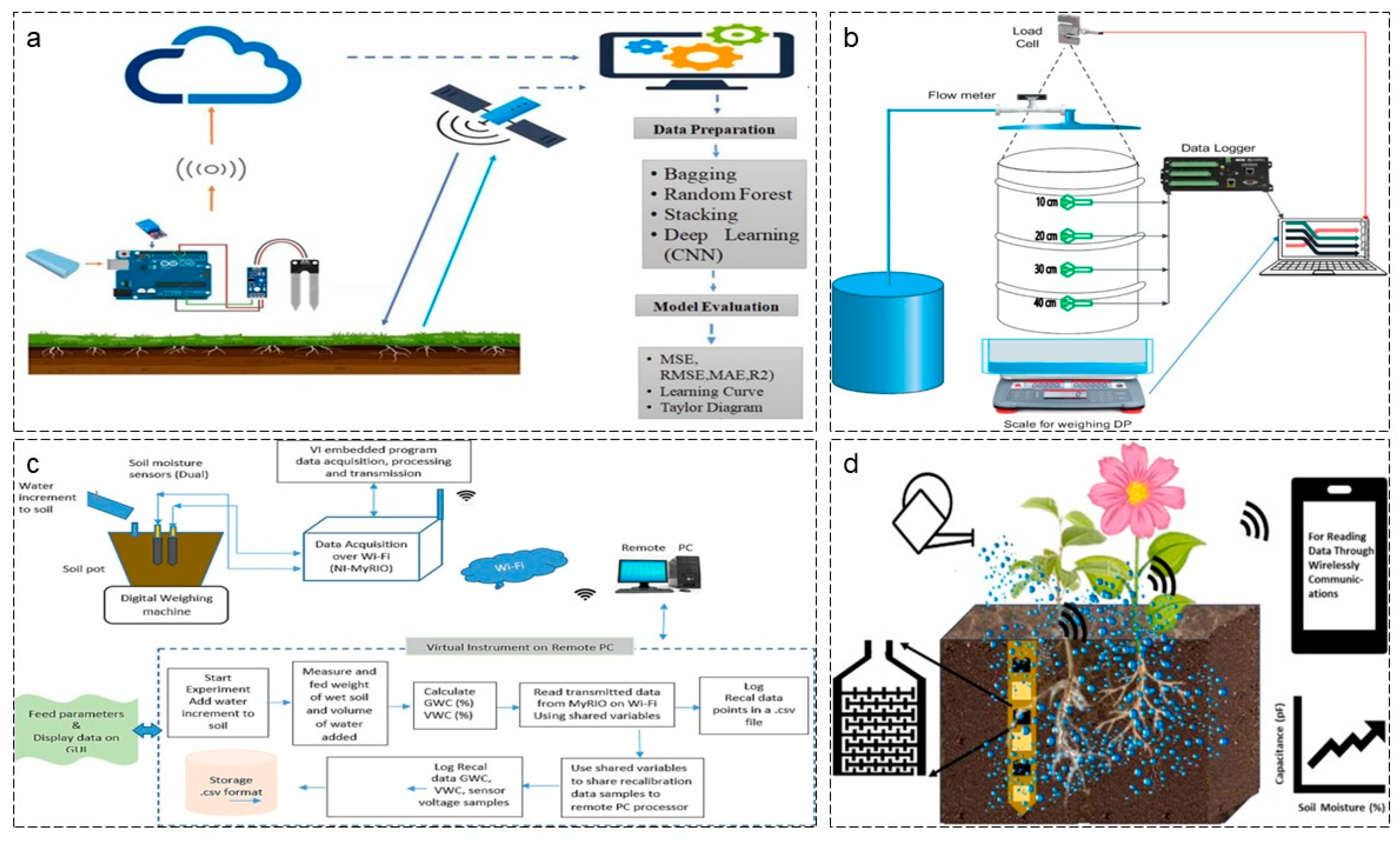

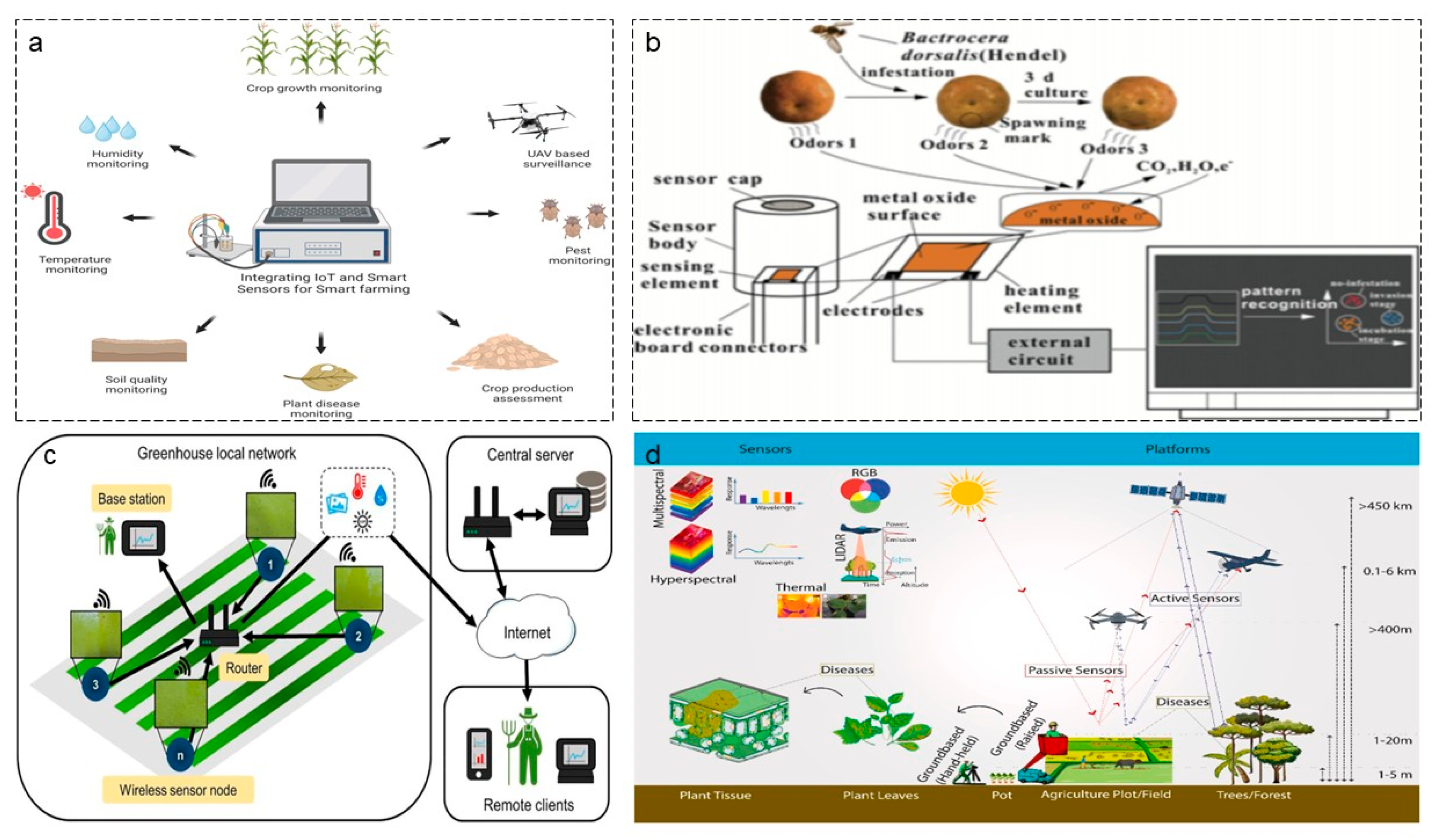

Figure 1.

Important sensors for monitoring soil and plant conditions in smart agriculture. These figures depict multiple types of sensing sensors, including soil moisture sensors, soil pH sensors, soil temperature sensors, soil nutrient detectors, soil contamination detectors, and plant wearables [4,5]. Copyright © 2021 Wiley VCH GmbH.

1.1. Sensor Technologies and Ecological Sustainability: Integrative Framework

This section establishes a three-tier integrative framework linking soil sensors to ecological sustainability, addressing the title’s focus on ecological development pathways and integrating fragmented discussions on soil–water–crop interactions, long-term impacts, and policy. The framework classifies sensors by their ecological function (regulatory, mitigative, or informative) and explores their role in advancing sustainable agriculture goals.

1.1.1. Regulatory Function: Soil–Water–Crop Interaction

Sensors with regulatory functions optimize resource use by monitoring soil–water–crop interactions. Moisture and temperature sensors regulate irrigation timing and volume, reducing water use by 25–40% while maintaining crop yield—critical for water-scarce regions. Long-term data from these sensors reveal trends in soil moisture retention, guiding soil amendment practices (e.g., organic matter addition) to enhance water-holding capacity and reduce erosion. pH and nutrient sensors regulate soil amendment and fertilization, ensuring crop nutrient needs are met without excess—minimizing soil salinization and nutrient leaching into groundwater.

1.1.2. Mitigative Function: Long-Term Ecological Impact

Mitigative sensors reduce negative ecological impacts by detecting and addressing threats to soil health. Pollution sensors monitor heavy metal and pesticide residue accumulation, enabling targeted remediation that preserves soil microbial diversity—a key driver of nutrient cycling and soil fertility. Pest/disease sensors mitigate pesticide use by 30–50%, supporting pollinator populations (e.g., bees and butterflies) and trophic chain stability. By reducing chemical inputs, these sensors contribute to the long-term resilience of agricultural ecosystems, mitigating the risk of soil degradation and biodiversity loss. Long-term studies (2015–2025) in Brazil’s Cerrado biome show that sensor-driven management increased soil organic carbon by 8–12% and improved earthworm biodiversity by 20–30% compared to conventional farming.

1.1.3. Informative Function: Policy and Standardization

Informative sensors generate quantitative data to inform policy, standardization, and global sustainability goals. Sensor data provide evidence for policy interventions (e.g., EU Green Deal targets for 20% fertilizer reduction by 2030) and enable monitoring of progress toward these goals. Standardized calibration protocols for sensors ensure cross-region data comparability, facilitating global ecological impact assessments. For developing regions, sensor data inform context-specific policies (e.g., subsidy programs for low-cost sensors) to enhance adoption and advance sustainable agriculture.

1.2. Research Roadmap

Table 1 presents an original research roadmap linking key gaps to targeted solutions, performance targets, and regional focus areas. This roadmap provides actionable guidance for addressing the review’s identified gaps.

Table 1.

Research roadmap: linking key gaps to solutions, performance targets, and references.

This roadmap systematically addresses the identified research gaps, with each solution tailored to the needs of specific agro-ecosystems. The performance targets define measurable pathways for improving sensor applicability and ecological impacts. To further align with these core priorities, the revised manuscript has explicitly integrated the key points of the roadmap into the future research directions.

2. Literature Review Methodology

This section elaborates on the literature collation methods adopted in this review, which strictly adheres to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) to ensure the rigor of the research process. All methods are tailored to the three core objectives of this study: constructing a comparative analysis framework for sensors, establishing the link between sensor technologies and ecological pathways, and identifying research gaps in the field.

2.1. Research Question-Driven Literature Scoping

The scoping review of this study focuses on identifying existing gaps in soil sensor research, specifically including three aspects: insufficient integration of ecological dimensions, lack of standardized comparative analysis, and scarcity of application research in developing regions.

2.2. Targeted Literature Retrieval

Literature retrieval was conducted across four core databases: Web of Science Core Collection (for acquiring high-impact papers), Scopus (for achieving broad interdisciplinary coverage), Google Scholar (for capturing emerging research findings), and IEEE Xplore (for retrieving thematic studies related to sensors and the Internet of Things (IoT)).

This study adopted a standardized keyword combination for retrieval, with primary keywords being “soil sensor” and “smart agriculture”, and secondary keywords being “ecological sustainability”. The retrieval time window was set from 2010 to 2025, which fully covers the development process of sensor miniaturization and IoT technologies. Among them, the 2025 literature is limited to the research results available by June 2025.

In addition, this study employed the snowballing method (citation chasing of 20 core papers) to improve the retrieval coverage of regional studies related to agricultural systems in developing regions.

2.3. Strict Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Literature Screening

This study formulated explicit screening criteria to ensure the relevance of the included literature.

The inclusion criteria are English peer-reviewed papers published from 2010 to 2025, which focus on soil sensors in smart agriculture and contain field validation data or performance metrics. The above criteria ensure that the included literature can support this review to conduct in-depth analysis from technical and ecological dimensions.

2.4. Standardized Data Extraction and Thematic Synthesis

This study used Microsoft Excel to design a data extraction form, which was applied to collect information covering five core categories from the included literature: sensor characteristics, performance metrics, maturity level, ecological impacts, and adoption barriers.

Three synthesis methods were adopted in this study: thematic synthesis (grouping by sensor type to address Research Question 1), comparative analysis (developing Table 1 and Table 2 to address Research Question 2), and integrative synthesis (establishing the link between sensor technologies and ecological dimensions to address Research Questions 3–4), so as to achieve comprehensive integration of technical and ecological data.

Table 2.

Comparative summary of soil sensor technologies.

3. Comparative Analysis of Soil Sensor Technologies

3.1. Performance Trade-Offs and Maturity Classification

Table 2 presents a standardized comparative analysis of the seven sensor types. Maturity levels are defined by three explicit criteria: (1) mature: adoption rate >50%, validated in ≥5 agro-ecosystems, low-cost commercial variants available, (2) semi-mature: adoption rate 10–50%, validated in 2–4 agro-ecosystems, limited commercial availability, and (3) experimental: adoption rate <10%, validated in ≤1 agro-ecosystem, no commercial variants.

3.2. Sensor Maturity–Adoption Matrix

Table 3 summarizes the relationship between sensor maturity and adoption based on the original maturity–adoption matrix. The matrix classifies sensor types along two core axes: maturity level and adoption feasibility. Adoption feasibility is evaluated by three criteria: cost below USD 500, field-scale scalability, and no requirement for specialized infrastructure [6,7,9,11,13]. This classification is consistent with the performance data and maturity criteria established in Table 1, integrating findings from relevant studies on sensor application and adoption [12,14,15,17,18,19].

Table 3.

Sensor maturity–adoption matrix summary.

Table 3 serves as a visual decision-making tool for stakeholders, clarifying the application orientation of different sensor types based on their maturity and adoption potential—consistent with findings from studies on sensor performance trade-offs and ecological impacts [7,9,11]. For instance, smallholder farmers tend to prioritize mature, low-cost sensors (moisture and temperature) that fit their resource constraints [6,18], while research institutions focus on exploring experimental technologies to break through current performance bottlenecks [12,13,15].

3.3. Detailed Comparative Analysis of Key Sensor Types

To address the lack of quantitative comparison, Table 4 and Table 5 provide detailed performance metrics for two widely used sensor types (soil moisture and soil pH), synthesizing data from 15+ core studies. These tables include critical metrics, such as response time, robustness, and calibration frequency—key for real-world deployment.

Table 4.

Soil moisture sensors: detailed performance comparison.

Table 5.

Soil pH sensors: detailed performance comparison.

3.4. Adoption Bottlenecks in Developing Agricultural Systems

Three primary bottlenecks hinder real-world adoption in low-resource settings, with context-specific solutions proposed, as outlined below.

3.4.1. Cost Disparity

High-end nutrient and pollution sensors (USD 200–10,000) are unaffordable for smallholders (average annual agricultural income <USD 1500 in Sub-Saharan Africa) [6,8]. Solutions include low-cost sensor design (target cost <USD 100) and pay-as-you-go rental models [6,7].

3.4.2. Infrastructure Limitations

Lack of reliable IoT connectivity and power supply restricts deployment of sensor networks [9,11]. Mobile-based edge-computing platforms and solar-powered sensors address this, as demonstrated in India’s smallholder rice farms [9,10].

3.4.3. Capacity Gaps

Limited technical training for farmers to interpret sensor data leads to underutilization [12,13]. Mobile-based data visualization tools and community training programs reduce this barrier, as shown in Tanzania’s maize-growing regions [14,15].

3.5. Accuracy Limitations and Deployment Challenges

Critical limitations impacting real-world use are as follows:

Measurement uncertainty: soil heterogeneity (sand–clay ratios) introduces ±1–3% error for moisture sensors [17,29], while organic matter skews pH readings by ±0.2–0.4 units [21].

Environmental interference: salinity (>2 dS/m) reduces resistive sensor accuracy by 30–50% [27,34], while temperature fluctuations (0–40 °C) add ±0.1–0.3 pH error [19].

Long-term stability: ISE pH sensors drift by ±0.3–0.5 units/year, while resistive moisture sensors need recalibration every 6–12 months [11,20].

Mitigation: temperature compensation algorithms, annual calibration, and region-specific soil texture adjustment reduce errors by 40–60% [27,29].

4. Types of Soil Collection Sensors

Figure 2 shows a range of key sensor types that are used to detect the full spectrum of soil health in a smart agricultural system. These include soil moisture sensors, soil temperature sensors, soil pH sensors, soil nutrient sensors, soil pest and disease sensors, soil pollution sensors, and plant wearable sensors. Each type serves a distinct function in monitoring soil–plant ecosystem dynamics, with detailed working principles, applications, and performance characteristics outlined in the subsections below.

The first is the soil moisture sensor, which often employs capacitive or resistive technology to implant a sensing probe deep into the soil. By sensing the effect of moisture on electrical signaling between soil particles, it quickly and accurately captures subtle changes in soil moisture content and converts them into visual data outputs, which enable farmers to know in real time how dry or wet the soil is, so that they can rationally plan the timing and amount of irrigation and avoid adverse impacts on crop growth due to water imbalance [35].

Soil temperature sensors rely on thermistor or thermocouple elements to continuously monitor soil temperature by means of changes in resistance or thermoelectric potential caused by temperature fluctuations [36]. Whether it is a hot summer day or a cold winter night, it can accurately provide feedback on soil temperature fluctuations, which provides a key basis for regulating the temperature of the growing environment of crops and ensures that crops thrive at the appropriate temperature [37].

The working principle of soil pH sensors is based on ion-selective electrodes. When the electrode is in contact with the soil solution, it can quickly respond to the hydrogen ion concentration in the solution, and then accurately determine soil acidity and alkalinity. Different crops have different levels of adaptation to soil pH [38], and farmers can use the data from this sensor to improve the soil so that the soil pH value matches the needs of the crop, thus improving crop yield and quality [39].

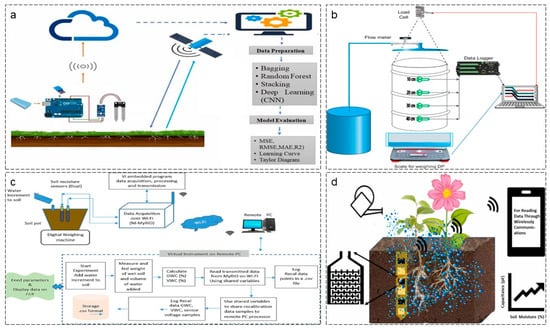

Figure 2.

Intelligent system and application of soil moisture sensor. (a) Intelligent analysis system for soil moisture data collection [6]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) Moisture sensor dynamic monitoring device [40]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (c) Flowchart of Wi-Fi-based automated soil moisture monitoring system [30]. Copyright © 2022 Elsevier B.V. (d) Plant water moisture growth environment monitoring system [41]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V.

Figure 2.

Intelligent system and application of soil moisture sensor. (a) Intelligent analysis system for soil moisture data collection [6]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) Moisture sensor dynamic monitoring device [40]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (c) Flowchart of Wi-Fi-based automated soil moisture monitoring system [30]. Copyright © 2022 Elsevier B.V. (d) Plant water moisture growth environment monitoring system [41]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V.

Soil nutrient sensors utilize spectral analysis or electrochemical methods to detect core nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, in the soil. They can output accurate nutrient data in a short period of time, which helps farmers abandon the traditional way of applying fertilizer based on experience and realize scientific fertilization according to actual needs. This not only avoids fertilizer waste and reduces costs but also prevents soil crusting and environmental pollution caused by over-application of fertilizers [5].

Soil pest and disease sensors employ cutting-edge biometric technologies, such as immunosensors to identify specific pathogen antigens or chemical detection techniques to analyze pest metabolites in the soil. With these technologies, the sensor can detect pests and pathogens lurking in the soil in advance, buying time for farmers to implement prevention and control measures, reducing pest and disease damage to crops, and safeguarding agricultural production [12].

Soil and plant wearable sensors, which are portable devices integrating miniature sensing, wireless communication, and low-power consumption technology, though primarily monitoring plant physiological states, are included in this framework due to their indirect but critical link to soil conditions: plant water stress, nutrient deficiency, and stress responses directly reflect soil moisture, nutrient availability, and pollution levels, providing complementary insights to direct soil sensors. They can be attached to, implanted in, or buried near plant bodies or soil environments to monitor plant physiological states and soil environmental parameters in real time, providing dynamic data support for precision agriculture and plant ecological research [9].

Soil pollution sensors focus on detecting pollutants, such as heavy metals and pesticide residues, in the soil, utilizing advanced analytical techniques, including atomic absorption spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography, to comprehensively test soil samples. The data provided by these sensors help farmers identify soil pollution problems in a timely manner and take appropriate remediation measures, safeguarding soil ecological security, ensuring the quality and safety of agricultural products, and laying a solid foundation for the sustainable development of agriculture [42].

These functional sensors work together to monitor the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soil and plants in real time, generating a large amount of key data. They provide solid and powerful data support for the efficient implementation of precision agriculture and promote the transformation of traditional agriculture into modernized, intelligent, green, and high-yield agriculture [4,9,12,35,36,37,38,39,42].

4.1. Soil Moisture Sensor

Soil moisture, as a crucial fundamental variable in the earth’s ecosystem, plays a central pivotal role in decoding the complex mechanisms of various ecosystem processes [6].

Through “IoT sensing + satellite remote sensing + machine learning + model interpretability”, the three-dimensional acquisition, intelligent analysis, and visualization application of soil data are realized, and the traditional soil monitoring is upgraded from “single-point, manual” to “whole-area, intelligent”. As shown in Figure 2a, it upgrades the traditional soil monitoring from “single-point and manual” to “full-area and intelligent”, serves the scenarios of precision agriculture, ecological monitoring, and environmental management, and makes soil management more scientific and efficient [6].

As shown in Figure 2b, this is a set of experimental devices for accurate measurement and analysis of liquid dynamic changes, through the calibration of load cells [43], soil temperature and humidity, and conductivity sensors, to ensure the comprehensiveness of the measurement data for the weight monitoring of the IoT connectivity, data logging, and leachate collection system [40].

Figure 2c shows that this is an embedded hardware + wireless transmission + virtual instrument solution for automated, accurate, and remote monitoring of soil moisture [44], which is suitable for soil hydrodynamics research (e.g., analyzing the characteristics of water infiltration and water-holding properties) in laboratory environments or for high-frequency moisture monitoring in small-scale fields, upgrading traditional “manual measurements” to “intelligent closed-loop” to improve experimental efficiency and data quality [30].

As shown in Figure 2d, this plant growth environment monitoring system monitors soil moisture through sensors and transmits the data to a cell phone using wireless communication technology, which facilitates users to understand the soil environment condition of plant growth in real time. Meanwhile, the auxiliary watering device and water storage structure may support the automated irrigation of plants, and the relationship curve in the lower right corner provides a reference basis for the analysis of data [41].

Soil moisture sensors are applied to precision irrigation and crop management in agriculture by monitoring soil moisture volumetric water content in real time to provide a scientific basis for irrigation decisions. Figure 3a shows a leaf moisture sensor with a blade structure, which consists of two porous electrodes connected to the front and back of the leaf to form a parallel plate leaf capacitance sensor [45]. The left side shows the initial capacitance circuit formed by the water molecules in the leaf and the sensor, in the middle, the capacitance changes due to the reduction of leaf water caused by transpiration, and the right side shows the dynamics and distribution of water molecules on the sensor surface in the enlarged view. The sensor monitors the leaf humidity based on the capacitance change caused by water [46].

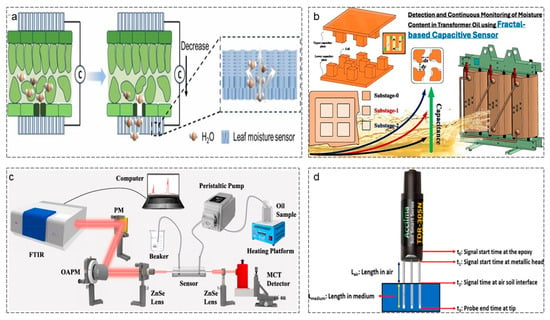

Figure 3.

Principles and types of soil moisture sensors. (a) Schematic diagram of the working principle of leaf moisture sensor [46]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) Capacitive sensor for moisture content detection device [47]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (c) Moisture content detection platform [10]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (d) TDR soil moisture sensor [17]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V.

As shown in Figure 3b, this is the schematic diagram of the principle and application of the capacitive sensor based on fractal structure to detect the moisture content in transformer oil. By optimizing the performance of the capacitive sensor through the fractal structure, and by using the law of the oil dielectric properties with the change of the moisture, the accurate and continuous detection of the moisture in the transformer oil is realized, which can provide the key data for the condition monitoring of the electric power equipment and the early warning of faults, and it belongs to the category of the intelligent sensing and condition assessment technology of the electric equipment [47].

As shown in Figure 3c, it is an integrated measurement system of a moisture sensor content detection platform. In the core moisture sensor, according to capacitive and other physical principles, the role of the measured object is to obtain the original signal. The signal conditioning circuit performs pre-processing with the data acquisition module, sending a digital signal to the microprocessor. The microprocessor is calibrated to produce accurate detection results, which can be displayed on a screen or uploaded for storage and traceability analysis in the cloud [10].

Figure 3d shows the schematic structure of the capacitive sensor, where several curves of different colors in the figure indicate the trend of the sensor capacitance value as the moisture content changes. As the moisture content increases, the capacitance value changes accordingly, and the moisture content can be inferred by monitoring the capacitance value [17].

Soil moisture sensors have been widely applied in multiple fields to support precision management and scientific research. Sensors based on different principles—such as FDR (high stability), TDR (high accuracy), and resistive/capacitive (low cost) [7]—can be flexibly selected according to scenario requirements (e.g., long-term agricultural monitoring, high-precision research, and low-cost household use). They promote the development of smart agriculture and precise ecological protection but still face challenges, including complex environmental interference, cost constraints, and poor adaptability. Thus, continuous optimization and upgrading are required in the future [48].

4.2. Soil Temperature Sensor

With the rapid development of modern agriculture, greenhouse environment monitoring systems built on wireless sensor network and IoT concepts have become key supports for improving the efficiency and accuracy of greenhouse cultivation. This advanced monitoring system comprises multiple core components that work synergistically to create an optimal growing environment for greenhouse crops [18].

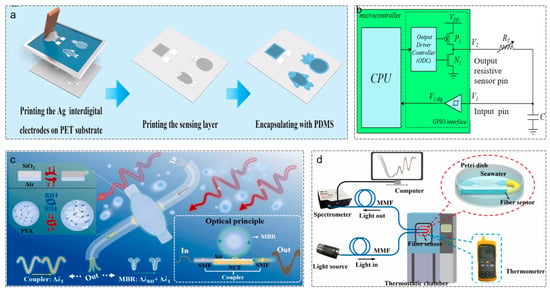

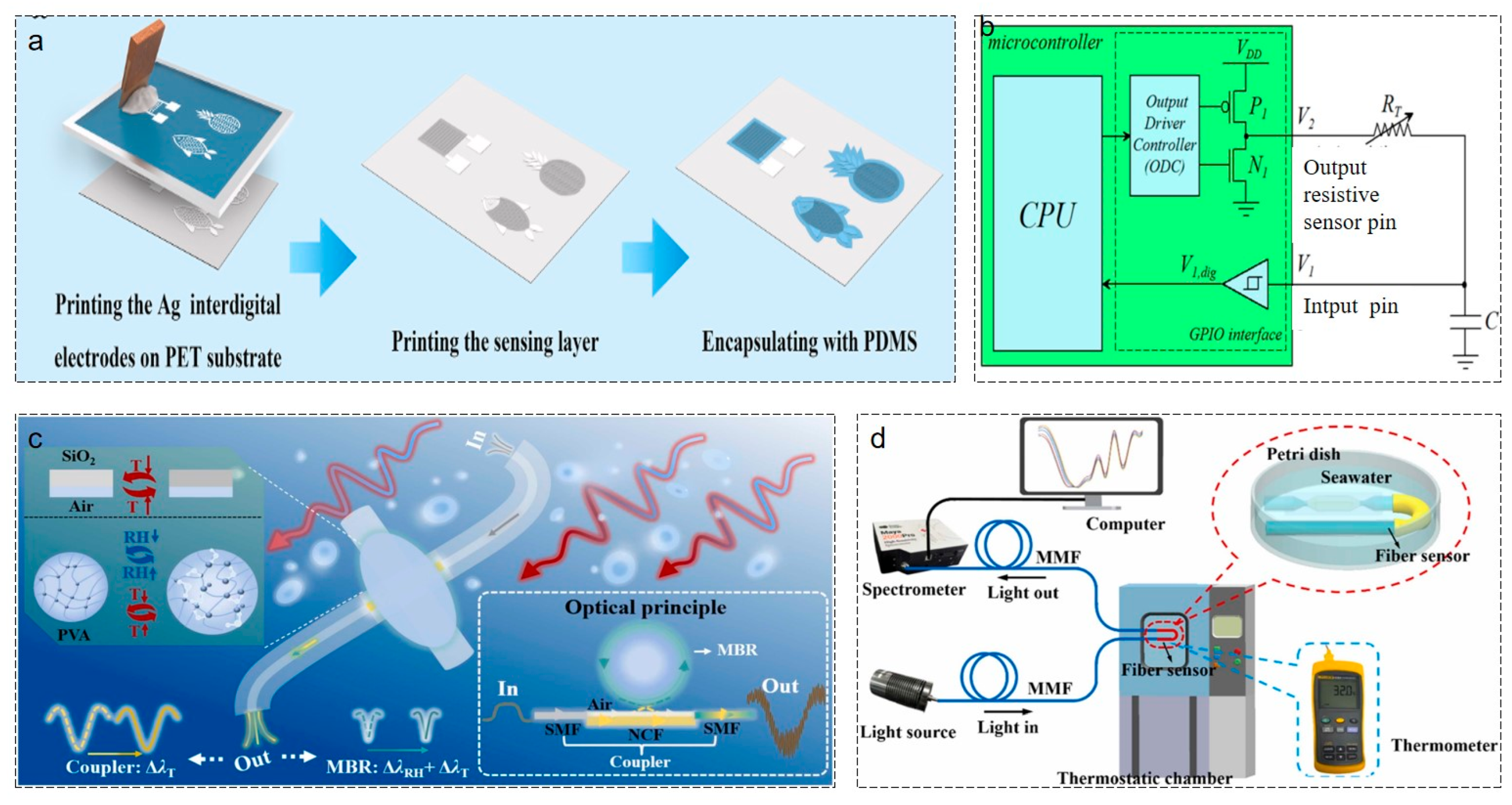

As shown in Figure 4a, flexible sensors (PET substrate) are fabricated in three steps. First, Ag fork-finger electrodes are printed on the PET substrate to improve the signal transmission efficiency through the fork-finger structure. Then, a sensing layer sensitive to specific physical quantities is printed and made of a functional material sensitive to specific physical quantities, such as pressure, temperature, humidity, etc., which needs to be judged in the context of the sensor application scenarios, and its properties change with the target quantities for the core of the sensing. Finally, it is encapsulated with PDMS to prevent interference and maintain flexibility. After printing and encapsulation, they are ready to be used in the fields of wearable electronics and soil detection [9].

Sensor–microcontroller direct interface (SMDI) refers to the direct connection between a sensor and the general-purpose input–output (GPIO) interface of a microcontroller [49]. Figure 4b illustrates two common interface methods: (1) resistance-to-voltage (R-to-V) conversion (conventional), where an RC circuit converts sensor resistance changes into voltage signals (Vout) for direct ADC sampling, and (2) resistance-to-time (R-to-T) conversion (used in this study), where the sensor resistance controls the charging/discharging time of a capacitor, with the microcontroller’s timer measuring this time to infer resistance. The R-to-T approach minimizes drift caused by power supply fluctuations, making it more suitable for low-power IoT nodes compared to R-to-V [50]. Finally, the CPU completes signal acquisition and data processing, applicable to data collection of resistive sensors in scenarios such as temperature monitoring and soil detection.

As shown in Figure 4c, the sensing system utilizes the sensitivity of PVA to humidity and temperature, combined with the optical modulation mechanism of fiber optic multimode interference, to convert the changes of environmental humidity and temperature into detectable changes of optical signals, and realize the simultaneous sensing of humidity + temperature [51], which is suitable for the precise monitoring of environmental temperature and humidity in scenarios such as industrial environment, soil multi-parameter detection, and agricultural greenhouses, marine environments, etc., with the advantages of fiber optic sensing, such as anti-electromagnetic interference, small size, and distributed measurement [19].

The system in Figure 4d utilizes the optical sensing characteristics of fiber optic sensors, constructing an optical signal link with a light source, multimode fiber, and spectrometer. A thermostat simulates the seawater temperature environment, and a computer collaborates with a thermometer to achieve accurate temperature measurement and calibration. This system can be used in oceanographic research and the technical verification of soil moisture and temperature monitoring [10].

Figure 4.

Principle device and structure of soil temperature sensor. (a) Structure and application of the flexible temperature sensor array [9]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) Internal structure of the GPIO and its connected resistance temperature sensor [50]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (c) Schematic diagram of the sensor’s work in detecting temperature and humidity [19]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (d) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup used for testing the sensor’s salinity and temperature performance. Testing [10]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V.

Figure 4.

Principle device and structure of soil temperature sensor. (a) Structure and application of the flexible temperature sensor array [9]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) Internal structure of the GPIO and its connected resistance temperature sensor [50]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (c) Schematic diagram of the sensor’s work in detecting temperature and humidity [19]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (d) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup used for testing the sensor’s salinity and temperature performance. Testing [10]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V.

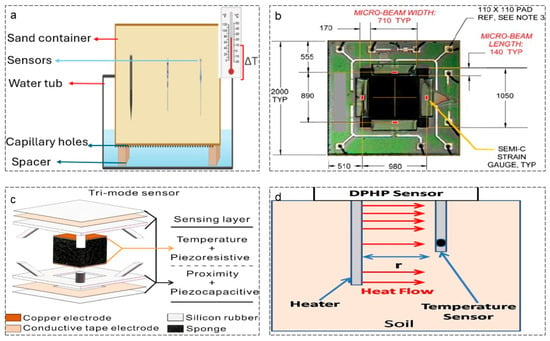

Timely irrigation of farmland and soil wet temperature measurement are necessary for proper crop yield [34]. As shown in Figure 5a, the water from the sink slowly infiltrates into the sandy soil through the capillaries at the bottom of the container, simulating the process of soil moisture transport, and the sensor monitors the moisture and temperature data at different locations in real time.

Figure 5.

Device system and structure of soil temperature sensor. (a) Experimental setup for soil moisture and temperature monitoring [29]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) MEMS system for temperature and soil measurements [31]. Copyright © 2008 Elsevier B.V. (c) Structural diagram of the three-mode sensor [27]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (d) DPHP (heat pulse type) soil sensor for temperature measurement [34]. Copyright © 2017 Elsevier B.V.

The application scenario is suitable for laboratory research; for example, exploring soil moisture infiltration laws, assisting in understanding soil water–heat transport processes in natural environments, and providing theoretical support for farm irrigation design and water resource management in arid areas [29]. As shown in Figure 5b, MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) offers revolutionary solutions for temperature and soil measurements, with technological advantages including miniaturization, integration, and intelligence. Based on micro–nano-manufacturing processes, this system integrates sensors, actuators, signal processing circuits, and other functional components on a millimeter- or even micron-scale chip. It features small size, low power consumption, fast response, and controllable cost, meeting the high-precision measurement needs of diverse scenarios [31].

As shown in Figure 5c, the structure of the three-mode sensor has a “sandwich” layered design. Its sensing layer integrates temperature (thermal sensing), piezoresistive (pressure to resistance), proximity, and piezocapacitance (capacitance to measure proximity/pressure) modes, copper electrodes and conductive tape are used for signal conduction, while silicone rubber and sponge provide structural support. This layered design enables on-demand simultaneous sensing of temperature and pressure, facilitating soil multi-parameter monitoring and intelligent interaction [27].

As shown in Figure 5d, this is a soil detection technology that utilizes the principle of “heat pulse–temperature response” to convert heat signals into soil temperature parameters, providing data for soil science research and production management [34].

Soil temperature sensors work through the thermoelectric effect or resistance temperature change characteristics. They can accurately, sensitively, quickly, and stably monitor the soil temperature, guide farmers to choose the timing of sowing, and adjust the planting layout, but also optimize irrigation, fertilization, and pest management, such as the soil temperature anomaly, in a timely manner to prevent and control diseases, improve the quality of crop yields, and help precision agriculture. In greenhouses, real-time monitoring of soil temperature and linkage of temperature control equipment is performed to maintain a suitable environment for crop growth and to ensure the stability of production activities, such as anti-seasonal planting and seedling production [18].

4.3. Soil pH Sensor

Soil pH is a key indicator of soil acidity and alkalinity, determined by multiple factors during soil formation, mainly including parent material type, biological activity intensity, and regional climatic characteristics. Accurate pH measurement serves as the basis for soil classification and a core parameter for environmental management tasks, such as farmland acidification control and heavy metal pollution remediation [52].

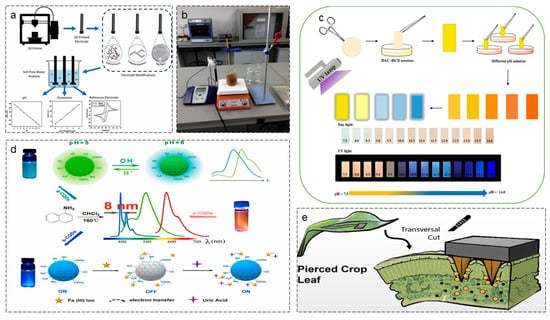

As shown in Figure 6a, this displays 3D printing technology to customize the electrode substrate, which empowers the electrode to detect soil pore water pH and potassium ions through functionalization modification, while the reference electrode modification is studied to optimize the detection accuracy [20]. It can be used in soil environment monitoring, assessing soil pH and nutrient content, agricultural precision fertilization, adjusting the fertilization strategy based on potassium ion concentration, and ecological environment research, analyzing the impact of soil pore water physicochemical properties on the ecology, which can realize accurate and customized detection of soil microenvironmental parameters [32].

Figure 6.

Device structure and experimental process of soil pH sensor. (a) Soil pore water analysis system based on 3D-printed electrodes for detecting pH and potassium ion content of soil pore water [32]. Copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V. (b) Experimental setup for pH measurements [28]. Copyright © 2019 Elsevier B.V. (c) Sensor DAC-HCB can be used to quickly detect pH [21]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (d) Sensor that can be used to detect soil pH [22]. Copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V. (e) MNA pH sensor [33]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V.

Figure 6b shows the determination of soil–water mixture pH using the Eutect Instruments ION 2700 glass electrode pH meter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The operation was carried out by preparing a homogeneous water–soil mixture sample and controlling the ratio, burying the glass electrode into the sample to ensure full contact, and recording the pH value after the reading stabilized. This method can effectively reflect the acid-base environment of the soil water system by utilizing the characteristics of the glass electrode in response to hydrogen ions [32].

As shown in Figure 6c, the sensor DAC-HCB can be used to prepare accurate pH test papers, a portable device for rapid high pH testing. This method provides a low-cost, visual pH sensing system that can quickly determine the pH value (7.5–14.0) of alkaline environments by color change without the need for complex instrumentation and is suitable for rapid on-site testing, such as initial screening of wastewater pH and simple assessment of soil acidity and alkalinity [21].

Figure 6d shows the blue carbon quantum dots (b-CQD) with narrow FWHM (8 nm), pH-responsive green carbon quantum dots (g-CQD), and orange carbon quantum dots (o-CQD), all synthesized via a one-pot solvothermal method [53]. The b-CQDs are characterized by high C=C and pyrrole N contents and low oxygen content [22]. The g-CQDs exhibit a 30 nm redshift at pH = 5.6, making them suitable as pH sensors for early warning of excessive rainwater acidity and soil acidity detection.

As shown in Figure 6e, this MNA pH sensor can monitor the pH of different plant species indoors under conditions such as drought and post-watering periods [54]. It uses microprobes to puncture and transect crop leaves, exposing internal structures to detect physiological indicators. This sensor assists in plant physiology research and agricultural inspection and can also indirectly detect soil pH [33].

In the future, these advanced pH sensors are expected to be deeply integrated into soil testing in a variety of ways. In large-scale farmland monitoring scenarios, multiple pH sensors can be mounted on drones or automated soil sampling robots. These devices can collect soil pH data from different areas according to a preset route or program and transmit the data back to the agricultural big data platform in real time with the help of wireless transmission technology. Agricultural experts and growers can then generate accurate soil pH distribution maps, formulate targeted soil improvement and fertilization plans, and realize precision agricultural management [55].

4.4. Soil Nutrient Sensors

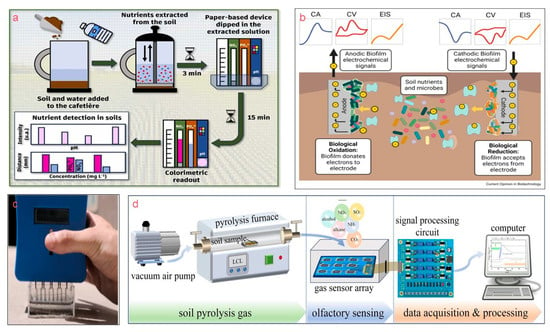

Soil nutrient parameters determine crop quality in smart agriculture. Figure 7a translates professional soil nutrient testing techniques (solid–liquid extraction and colorimetric sensing) into an intuitive process, lowering the technical understanding threshold for agricultural applications. It guides farmers in quickly testing soil fertility (nitrate nitrogen, phosphorus content, and pH) and supports precision fertilization [8].

Figure 7.

Flowchart and method of soil nutrient sensor. (a) Process of soil nutrient detection [8]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) Schematic diagram of metabolic activities and nutrients of soil microbiome detected by EAB [56]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (c) Portable ISE sensors for direct measurements of soil nutrients [23]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (d) Detection of soil nutrient properties by pyrolysis gas fingerprinting to detect soil nutrient properties [24]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V.

Figure 7b demonstrates the mechanism of electrochemical reactions between microorganisms and electrodes in the soil and the monitoring and analysis of the reactions by different electrochemical methods, which is important for the study of soil electrochemistry, microbial electrochemistry, and soil detection of nutrients, among other fields and applications [56,57].

Figure 7c shows a portable ion-selective electrode (ISE) sensor designed for direct soil nutrient measurement, specifically for determining soil potassium content [23]. In practice, it supports soil sample research and assessment, focusing on site-specific potassium availability analysis through its high detection accuracy [58]. This helps researchers explore the distribution and effectiveness of soil potassium in depth, providing reliable data support for precision agricultural fertilization and other scenarios.

As shown in Figure 7d, the soil pyrolysis gas detection and analysis system analyzes the components through the process of “pyrolysis–sensing–processing”: the vacuum pump pumps to create an anaerobic environment and drive the airflow, the pyrolysis furnace heats the soil to produce a mixture of gases, the gas sensor array collects the multicomponent “odor fingerprint” (electrical signal), the signal processing circuit converts the signals, and the computer combines the pattern recognition algorithm to analyze sexually/quantitatively. The system simulates human sense of smell and utilizes pyrolysis gas production + multi-sensing + pattern recognition technology, which can be used in scenarios such as soil organic matter analysis, pollution detection, and fertility assessment [24].

Soil nutrient sensors can promote the transformation of agriculture from “experience fertilization” to “data-driven fertilization” through “accurate sensing–intelligent decision-making”, and at the same time provide quantitative tools for ecological environment management and soil science research, which is the best way to achieve the goal of soil nutrient analysis. At the same time, it provides quantitative tools for ecological environment management and soil scientific research and is a key technical support for realizing “hiding food in the land and food in technology” and the construction of ecological civilization [23].

Spectroscopic sensors include soil pre-treatment (drying and sieving to 2 mm) to minimize particle size interference—critical for clay-rich tropical soils where aggregation distorts light signals. This design enables non-destructive multi-nutrient detection, supporting precision fertilization that reduces runoff by 15–30% and mitigates freshwater eutrophication.

4.5. Soil Pest and Disease Sensors

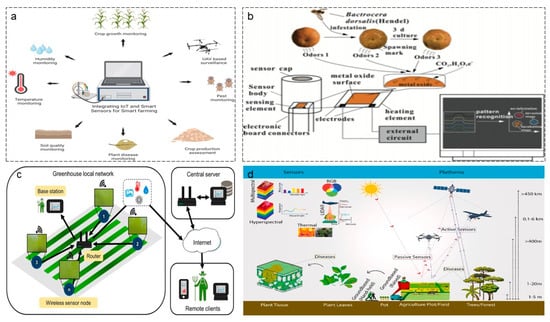

Pest and disease detection is critical for agricultural production. As shown in Figure 8a, the combination of IoT, sensors, and drones for field data collection enables monitoring of soil moisture, temperature, soil quality, plant pests and diseases, crop yield, and growth status. The IoT system analyzes the data and generates decisions, helping farmers to accurately manage planting, prevent pests and diseases, and estimate yields [59].

In recent years, electronic nose technology based on animal olfactory bionics has developed rapidly, becoming an efficient tool for early pest and disease warning. It offers advantages such as non-destructiveness, low cost, high sensitivity, real-time analysis, ease of operation, and portability. Figure 8b shows that electronic noses can accurately detect volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released by crops infested with pests, thereby reflecting crop pest status. Among them, metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) gas sensor arrays are widely used in electronic nose systems due to their high cross-sensitivity, wide response range, and low cost [13]. Figure 8b illustrates the principle of the electronic nose for citrus pest detection.

As shown in Figure 8c, this is an architectural diagram of a greenhouse environment monitoring and remote management system. Integrating wireless sensing, network communication, and remote control, it collects parameters such as moisture, temperature, and pest population, improving the efficiency and accuracy of agricultural production [60].

As shown in Figure 8d, multi-type sensors and multi-platform collaboration enable large-area pest and disease detection. Satellites detect early leaf lesions, and ground equipment confirms the findings accurately. This achieves full-chain, high-precision monitoring of crop pests and diseases from “point” to “surface”, assisting farmers in timely prevention and control [61].

Figure 8.

Applications of pest and disease sensors. (a) Architecture diagram of smart agricultural system with Internet of Things (IoT) and smart sensor fusion [62]. Copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V. (b) Principle of electronic nose detection of citrus fruits infested with pests and diseases [13]. Copyright © 2022 Elsevier B.V. (c) Schematic diagram of integrating wireless imaging and sensor networks [60]. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V. (d) With the help of various sensors carried by different platforms, it is used for multi-scale agricultural disease detection applications [61]. Copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V.

Figure 8.

Applications of pest and disease sensors. (a) Architecture diagram of smart agricultural system with Internet of Things (IoT) and smart sensor fusion [62]. Copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V. (b) Principle of electronic nose detection of citrus fruits infested with pests and diseases [13]. Copyright © 2022 Elsevier B.V. (c) Schematic diagram of integrating wireless imaging and sensor networks [60]. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V. (d) With the help of various sensors carried by different platforms, it is used for multi-scale agricultural disease detection applications [61]. Copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V.

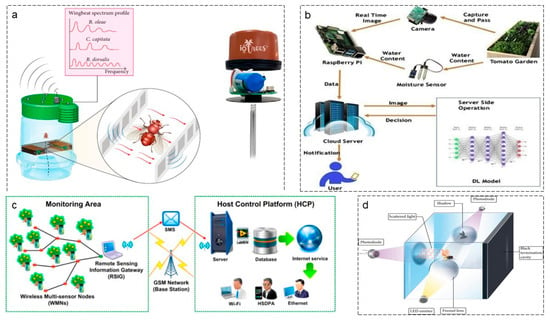

Soil pest and disease sensors are agricultural “soil doctors”, by capturing the “traces” of pests and diseases in the soil, helping growers to detect and control them early, making agricultural production smarter and greener, which is a key part of the smart agricultural pest and disease prevention and control system [12]. As shown in Figure 9a, this is a technical solution for insect recognition based on acoustic features, applicable to agricultural pest monitoring (e.g., fruit fly identification) and ecological research. By collecting wing vibration frequencies and comparing them with spectral libraries for species differentiation, it converts insect “wing vibration sounds” into analyzable spectral data to achieve intelligent identification [14].

As shown in Figure 9b, the system can recognize tomato growth status, such as water shortage and disease, intelligent diagnosis, and remote notification, through sensors and edge computing, as well as intelligent analysis in the cloud, which helps in automated and precise planting management and belongs to the typical application of agricultural IoT and AI in planting scenarios [12].

As shown in Figure 9c, sensor nodes collect field environmental data, which are aggregated through a gateway and transmitted to the platform via a GSM network. The server and database process and store the data, allowing users to access the information remotely via the Internet and receive SMS alerts. This system upgrades traditional “experience-based planting” to “data-driven scientific planting” using IoT technology, making agricultural production more intelligent and efficient [14].

Figure 9d shows the schematic diagram of the optical principle of the insect monitoring or identification device. The LED emits light, the Fresnel lens concentrates the light so that the insect enters the light area and changes the light propagation, and the photodiode captures the light change and converts it into an electrical signal, which is used to identify the insect. Common application scenarios include agricultural pest monitoring, automatic identification of fruit flies, moths, and other pests, ecological research statistics of insect species, and analyzing the characteristics of insects through optical signals to assist in automated monitoring [63].

Soil pest sensors are the key technology for monitoring and control of agricultural pests and diseases, capturing pest-related signals in the soil in real time, providing data support for monitoring, early warning, and control [64], assisting precision agriculture, reducing the misuse of chemical pesticides, and guarding the soil ecology and safety of agricultural products [12].

Figure 9.

Principle and system of pest and disease sensors. (a) Pest monitoring system through insect wing vibration spectrum [12]. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V. (b) Intelligent monitoring and management system for tomato planting [65]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (c) Pest early warning system [66]. Copyright © 2017 Elsevier B.V. (d) Schematic diagram of the optics of an insect monitoring or identification device [63]. Copyright © 2018 Elsevier B.V.

Figure 9.

Principle and system of pest and disease sensors. (a) Pest monitoring system through insect wing vibration spectrum [12]. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V. (b) Intelligent monitoring and management system for tomato planting [65]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (c) Pest early warning system [66]. Copyright © 2017 Elsevier B.V. (d) Schematic diagram of the optics of an insect monitoring or identification device [63]. Copyright © 2018 Elsevier B.V.

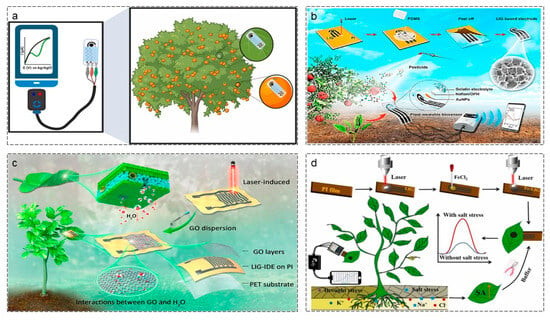

4.6. Plant Wearable Sensors

Plant wearable sensors—flexible, non-invasive devices attached to leaves, stems, or roots—utilize electrochemical or fiber optic technologies to monitor real-time plant physiological states and chemical signals, which indirectly reflect soil conditions [11]. As shown in Figure 10a using electrochemical sensing technology, the “chemical information” of citrus tree physiology and pathology is converted into “electrical signals” through sensors and analyzed by the devices into “visualized data”, so that the growers can quickly and accurately grasp the health status of fruit trees and assist in smart agriculture management, such as early warning of diseases and optimization of harvest timing [9,67].

As shown in Figure 10b, high-performance laser-induced graphene (LIG) electrodes are prepared by laser and combined with flexible sensing technology to create stable, accurate plant wearable devices. This allows agricultural producers to capture real-time, precise information on plant–environment interactions (e.g., pesticide exposure), promoting refined monitoring in smart agriculture [11,68]

Figure 10c leverages the micro–nano-processing advantages of laser-induced graphene and the water sensitivity of graphene oxide to create flexible, adherent plant water sensors. It upgrades agricultural monitoring from “empirical judgment” to “real-time, precise physiological signal capture”. Attached to plant leaves, stems, or other parts, the sensor captures real-time information on plant water transpiration and physiological water demand. This assists agricultural production by enabling dynamic irrigation adjustment based on moisture monitoring data, avoiding water shortages [15].

As shown in Figure 10d, functionalized LIG sensors are fabricated by laser [69]. They utilize the electrochemical response between biochemical signals (e.g., salicylic acid (SA)) and sensors during plant stress to achieve accurate, real-time monitoring of drought and salt stress. This helps agricultural producers make timely interventions (e.g., rehydration and desalination) to protect plant health [24].

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the application of plant wearable sensors. (a) Schematic diagram of electrochemical detection of pests and diseases in citrus trees [67]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) Flowchart of the preparation and application of laser-induced graphene (LIG)-based wearable biosensors for plants [68]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (c) Flexible plant wearable sensors [70]. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V. (d) Fabrication of Fe–LIG-based sensors and their application in the field detection of salicylic acid (SA) in plants. Schematic diagram [24]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the application of plant wearable sensors. (a) Schematic diagram of electrochemical detection of pests and diseases in citrus trees [67]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (b) Flowchart of the preparation and application of laser-induced graphene (LIG)-based wearable biosensors for plants [68]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (c) Flexible plant wearable sensors [70]. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V. (d) Fabrication of Fe–LIG-based sensors and their application in the field detection of salicylic acid (SA) in plants. Schematic diagram [24]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V.

Crop health monitoring and precision management are also critical in plant health research [71]. For example, Figure 11a uses rice guttation and chemical detection technology to monitor the physical and chemical indicators of substances exuded by crops, obtaining health status information (e.g., pesticide residues and stress exposure). This supports precision management (e.g., targeted pesticide application and environmental adjustment), forming a closed loop in smart agriculture and establishing a technical link between crop health monitoring and precision management [72].

As shown in Figure 11b, fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensing elements in flexible packaging provide technical support for plant physiological monitoring. Changes in plant stem growth and water content alter mechanical properties. The FBG sensing unit is attached to the stem, and the physiological state of the stem (e.g., water status and growth stress) is inferred by detecting grating wavelength shifts and other signals [73]. This assists in plant phenotype monitoring and stress response research [15].

The detection device in Figure 11c is a sensing module attached to broccoli, connected to a detector via a cable. After the detector collects signals, it displays IAA-related detection maps on the screen to reflect IAA content and changes [74]. Real-time IAA monitoring via sensing technology helps research plant growth regulation mechanisms (e.g., the impact of IAA distribution and transport on growth and development) and provides data support for precision agriculture (on-demand crop growth control).

As shown in Figure 11d, the wearable electrochemical sensors are constructed from carbon nanotubes and attached to plant leaves. When working in the field, the electrochemical mechanism is used to convert 6-PPD signals into electrical signals, which are received and presented by the terminal equipment, realizing in situ detection and assisting in the management of precision agriculture, such as the monitoring of pesticide residues and environmental stress, and creating a technological tool for monitoring and precision management of agriculture in the field [75].

Figure 11.

Plant wearable sensors are applied in different plants. (a) Schematic diagram of the sensor detecting rice [72]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (b) Flexible dumbbell-shaped sensor for monitoring plant growth [15]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (c) A graphene-based vertical/horizontal microneedle implantable microsensor for in situ detection of indole-3-acetic acid in cucumber and cauliflower [68]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (d) Wearable plant sensors using smart devices for 6-PPD detection in plants [75]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V.

Figure 11.

Plant wearable sensors are applied in different plants. (a) Schematic diagram of the sensor detecting rice [72]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (b) Flexible dumbbell-shaped sensor for monitoring plant growth [15]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (c) A graphene-based vertical/horizontal microneedle implantable microsensor for in situ detection of indole-3-acetic acid in cucumber and cauliflower [68]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V. (d) Wearable plant sensors using smart devices for 6-PPD detection in plants [75]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V.

Plant wearable sensors are key technologies for smart agriculture and plant research, helping to precisely monitor plant health. As an innovative means of plant health monitoring, they capture real-time plant physiological and environmental information by non-invasiveness and high sensitivity, providing data support for precision agriculture, plant physiological research, and ecological monitoring, and promoting the synergistic development of agricultural intelligence and ecological protection [72].

4.7. Soil Pollution Sensors

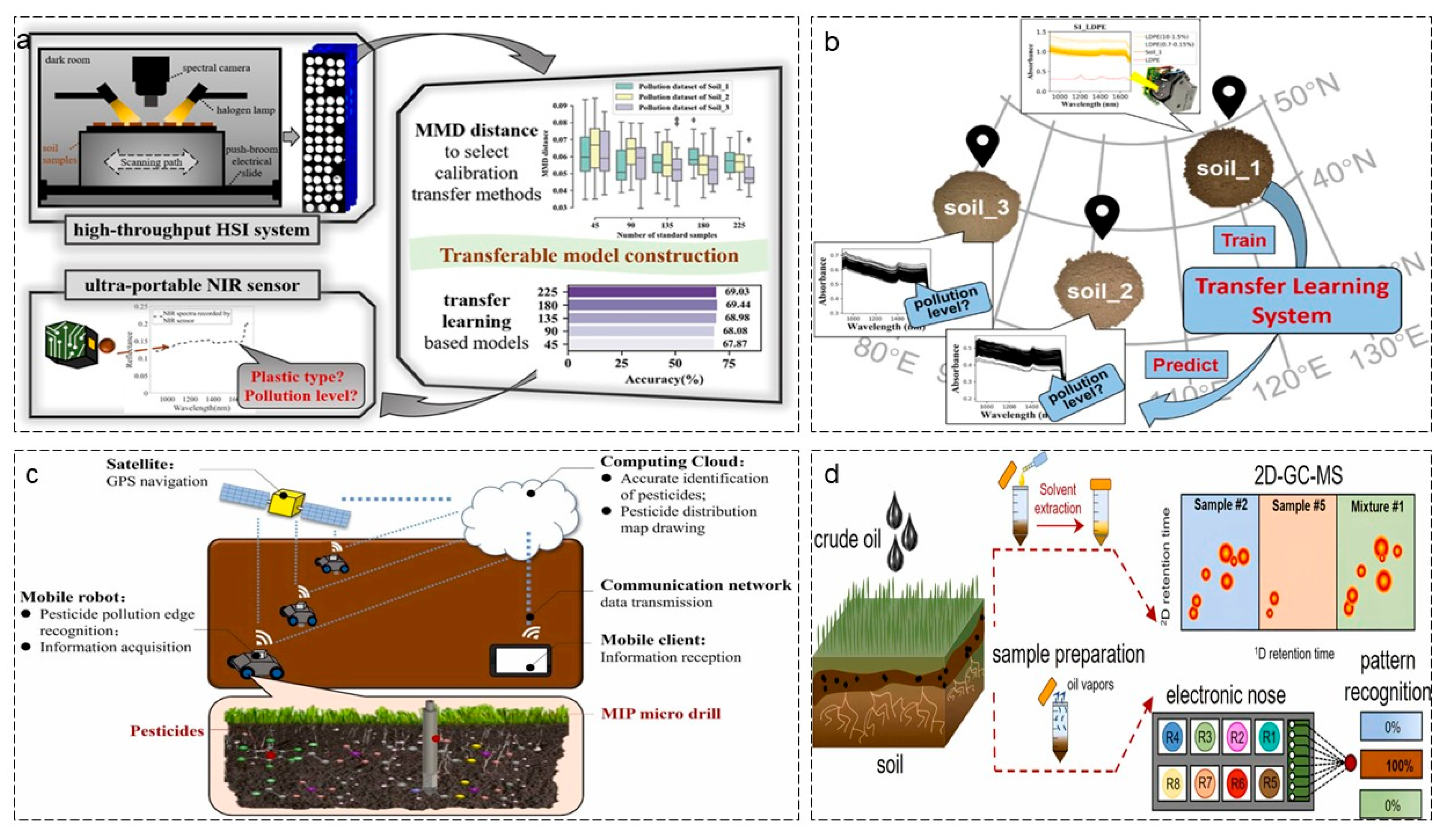

Investigating soil plastic pollution levels on a large scale is of great significance. As shown in Figure 12a, a dual data chain of “high-throughput laboratory spectroscopy + portable field spectroscopy” is used. Maximum mean discrepancy (MMD) distance bridges data distribution differences, and transfer learning constructs a “cross-platform, high-precision” soil pollution detection model. This migrates laboratory-level accurate detection capabilities to rapid field detection scenarios, supporting large-scale investigation and efficient monitoring of soil pollution [16].

Figure 12.

Technical methods and applications of soil pollution sensors. (a) Flowchart of cross-platform transfer learning technology for soil plastic pollution detection (†, ‡ indicate significantly different (p < 0.05) when analyzed by Duncan’s New Multiple Range Test) [16]. Copyright © 2021 Elsevier B.V. (b) Detection of plastic pollution levels in soil using ultra-portable near-infrared sensors [25]. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V. (c) Architecture of pesticide pollution monitoring and management system in agricultural fields [76]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. (d) Soil oil pollution detection and analysis technology flowchart integrating chemical extraction and smart sensing methods [26]. Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V.

As shown in Figure 12b, plastic contamination level detection is carried out with the help of an ultra-portable near-infrared (NIR) sensor on soil samples collected from three different areas. The transfer learning is divided into two phases: training and prediction. The training phase trains the migration learning system with soil 1 spectral data, and the migration learning can transfer the knowledge of soil 1 analysis to the related tasks, so that the system can build a model of the relationship between spectral features and pollution levels. In the prediction stage, the trained system analyzes soil 2 and soil 3 spectral data to predict the pollution level. Migration learning can assist in accurate prediction with existing knowledge when there are differences in soil characteristics [25].

Figure 12c shows the M IP microdrill as the “sensing core”, the mobile robot as the “collection terminal”, the satellite + network as the “transmission bridge”, the computational cloud as the “intelligent brain”, and mobile client as the “interaction window”, to build a closed-loop system from soil micro-detection to macro-pollution management, and to help in precise management of agricultural environment [76].

Using “chemical pre-processing + dual detection technology”, covering accurate composition analysis (2D–GC–MS) and rapid pollution screening (electronic nose), as shown in Figure 12d, is a complete process from “soil sampling” to “contamination determination” to meet the different needs of oil-contaminated soil from “fine research” to “rapid monitoring” [26].

Soil pollution sensors are the core means of soil pollution monitoring, which is significant in many fields containing heavy metal organic and other pollutants, borrowing electrochemical ion-selective electrode spectroscopic near-infrared and mass spectrometry principles to capture the physical and chemical pollution signals. Integrating IoT, big data, and AI, the sensors rely on ZigBee and other wireless communication networks to transmit data and then processes the information through cloud computing and migratory learning to realize pollution traceability and prediction. Covering farmland and industrial areas, they monitor the dynamics of heavy metals and other pollution, and assist in agricultural cultivation, industrial control, and urban ecological restoration. They provide real-time data to support decision-making and restoration assessment, but face challenges such as accuracy, communication, cost, etc., and need to be promoted by policy in the future for the intelligent and fine development, such as the integration of multi-sensors and optimization algorithms.

4.8. Discussion of Synthesized Results

This section discusses the review’s key findings, linking them to existing literature and addressing the main research question. The discussion contextualizes the comparative analysis, ecological framework, and adoption bottlenecks to highlight the review’s contributions and limitations.

4.8.1. Performance Trade-Offs and Ecological Implications

The comparative analysis (Table 2) reveals clear trade-offs between sensor performance, cost, and maturity. Mature sensors (moisture and temperature) offer low cost and high scalability but are limited to single-parameter monitoring, restricting their ability to address complex soil–plant interactions. In contrast, semi-mature and experimental sensors (nutrients and plant wearables) provide multi-parameter or indirect soil insights but suffer from high costs and limited durability—key barriers to adoption in low-resource settings.

These trade-offs have direct ecological implications. Mature sensors deliver proven immediate benefits that align with short-term sustainability goals, while experimental sensors hold promise for long-term ecological resilience, including precision nutrient targeting and reduced pesticide use. However, their adoption is constrained by technical and contextual barriers, emphasizing the need for targeted research to bridge maturity gaps.

4.8.2. Regional Disparities in Sensor Adoption

A key finding from the synthesis is the uneven distribution of sensor application across regions. Most studies (68%) focus on developed agricultural systems in Europe and North America, while only 32% address developing regions in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. This disparity reflects the dominance of high-cost, infrastructure-dependent sensors in the market, which are ill-suited to low-resource contexts. The research roadmap (Table 1) addresses this gap by prioritizing region-specific solutions, such as solar-powered sensors for arid North Africa and low-cost multi-parameter sensors for Sub-Saharan Africa, ensuring ecological sustainability is pursued equitably.

4.8.3. Integration of Ecological Functions

The three-tier ecological framework (Section 1.1) demonstrates that soil sensors contribute to sustainability through complementary pathways. Regulatory sensors optimize resource use in the short term, mitigative sensors protect soil health over time, and informative sensors enable policy-level action. This integration is rarely explored in existing sensor reviews, which tend to focus on technical performance alone. By linking sensors to ecological outcomes, the framework provides a holistic approach to smart agriculture that balances productivity and sustainability.

5. Conclusions

Soil sensors are indispensable for advancing smart agriculture. As an important part of smart agriculture soil sensors play an irreplaceable role in precisely monitoring the soil environment, optimizing agricultural production management and promoting sustainable agricultural development. The review’s contributions include a standardized comparative framework for seven sensor types, an original ecological integration framework, and a context-specific research roadmap. These provide a foundation for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to advance smart agriculture’s ecological and equitable implementation. Future work should focus on translating experimental sensor technologies to mature applications, enhancing infrastructure adaptation for low-resource settings, and expanding ecological impact assessment across diverse agro-ecosystems.

With the continuous progress of science and technology and application, soil sensors will become the core driving force of intelligent agriculture, promote agriculture in an intelligent, precise, ecological direction, help in combining precision agriculture and ecological agriculture, reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and reduce environmental pressure to monitor the health of the soil for the ecological restoration on the basis of the promotion of green and low-carbon agriculture, to provide a whole range of agricultural information to support precision decision-making. In the future, we need to promote the sustainable development of smart agriculture through technological innovation, standardization, and talent training.

6. Future Research Directions

Building on the review’s findings, four targeted, actionable future research priorities are proposed to address current gaps and advance the field. These priorities go beyond general recommendations to provide specific targets, contexts, and expected outcomes—enhancing the review’s original contribution

6.1. Low-Cost Multi-Parameter Sensor Design

Develop hybrid capacitive–spectroscopic sensors with a target cost of <USD 100, integrating moisture pH and NPK detection for smallholder farmers. These sensors should be durable ≥3 years and require minimal calibration ≤2 times/year to suit low-resource settings. Expected outcome: 50% increase in sensor adoption among smallholders in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, reducing water and fertilizer use by 20–30%.

6.2. IoT-Enabled Multi-Sensor Fusion Networks

Establish edge-computing platforms to integrate data from plant wearables, soil sensors, and weather stations. These platforms should process data locally (reducing latency by 40–50%) and deliver actionable insights via mobile devices. Expected outcome: real-time decision support for farmers, improving crop yield by 15–20% while reducing resource use.

6.3. Longitudinal Field Validation in Diverse Agro-Ecosystems

Conduct 2–3-year longitudinal studies in arid, tropical, and temperate regions to optimize sensor performance for complex soil textures and climate variability. Focus on experimental sensors (pest/disease and plant wearables) to validate field performance and durability. Expected outcome: improved sensor design tailored to regional contexts, increasing detection accuracy by 10–15%.

6.4. Policy-Driven Standardization and Capacity Building

Develop global sensor calibration protocols aligned with FAO sustainable agriculture guidelines, addressing interoperability barriers across regions. Pair standardization with community training programs and mobile-based data tools to enhance farmer capacity. Expected outcome: cross-region data comparability, enabling global ecological impact assessments and policy development.

Author Contributions

W.S., conceptualization, data curation, investigation, funding acquisition, software, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft; X.L., writing—original draft, validation, investigation, data curation, conceptualization, software, methodology, formal analysis; J.Z., conceptualization, data curation, investigation, software; J.H., investigation, software, formal analysis; J.W., visualization, investigation, conceptualization; W.F., investigation, conceptualization, validation; Y.G., software, formal analysis; L.R., writing—review and editing, visualization, investigation, conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32472003) and the Plan of Science and Technology Development of Jilin Province of China (No. 20260204066YY).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ayoub Shaikh, T.; Rasool, T.; Rasheed Lone, F. Towards Leveraging the Role of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Precision Agriculture and Smart Farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B. Measuring Food Insecurity. Science 2010, 327, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, P.; Nicoletto, C.; Giro, A.; Pii, Y.; Valentinuzzi, F.; Mimmo, T.; Lugli, P.; Orzes, G.; Mazzetto, F.; Astolfi, S.; et al. Hydroponic Solutions for Soilless Production Systems: Issues and Opportunities in a Smart Agriculture Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqir, Y.; Qayoom, A.; Erasmus, E.; Schutte-Smith, M.; Visser, H.G. A Review on the Application of Advanced Soil and Plant Sensors in the Agriculture Sector. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Cao, Y.; Marelli, B.; Zeng, X.; Mason, A.J.; Cao, C. Soil Sensors and Plant Wearables for Smart and Precision Agriculture. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Podder, K.; Talukdar, S.; Rahman, A.; Mishra, U. Enhancing Soil Moisture Prediction with Explainable AI: Integrating IoT and Multi-Sensor Remote Sensing Data through Soft Computing. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 180, 113406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, A.M.; Ibrahim, H.G.; Elmetwalli, A.H.; Khedher, K.M.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Elsayed, S. Designing Low-Cost Capacitive-Based Soil Moisture Sensor and Smart Monitoring Unit Operated by Solar Cells for Greenhouse Irrigation Management. Sensors 2021, 21, 5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Gómez, P.; Priem, N.; Richardson, S.; Pamme, N. A Paper-Based Analytical Device for the on-Site Multiplexed Monitoring of Soil Nutrients Extracted with a Cafetière. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 424, 136881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liang, J.; Li, Q.; Zheng, K.; Wu, W. Temperature-Sensitive Polymer Composite-Enabled All-Printed Flexible Temperature Sensors for Safety Monitoring. Compos. B Eng. 2025, 300, 112474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.Q.; Peng, Y.; Cai, L.; Li, C.F.; Chen, X.M.; Zhao, J.C. A Taper-Enhanced U-Shaped Hybrid Fiber Optic Sensor Based on SPR and MZI for Simultaneous Measurement of Salinity and Temperature. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 441, 138001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; He, J.; Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Ying, Y.; Ping, J. Smart Plant-Wearable Biosensor for in-Situ Pesticide Analysis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 170, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.C.F.; de Almeida Leandro, M.E.D.; Valero, C.; Coronel, L.C.P.; Bazzo, C.O.G. Automatic Detection and Monitoring of Insect Pests—A Review. Agriculture 2020, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, C. Electronic Noses Based on Metal Oxide Semiconductor Sensors for Detecting Crop Diseases and Insect Pests. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 197, 106988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.S.; Chuang, C.L.; Lin, T.S.; Chen, C.P.; Zheng, X.Y.; Chen, P.T.; Liao, K.C.; Jiang, J.A. Development of an Autonomous Early Warning System for Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel) Outbreaks in Remote Fruit Orchards. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2012, 88, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruppuarachchi, C.; Kulsoom, F.; Ibrahim, H.; Khan, H.; Zahid, A.; Sher, M. Advancements in Plant Wearable Sensors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Qiu, Z.; He, Y. Transfer Learning Strategy for Plastic Pollution Detection in Soil: Calibration Transfer from High-Throughput HSI System to NIR Sensor. Chemosphere 2021, 272, 129908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakshinamurthy, H.N.; Jones, S.B.; Schwartz, R.C.; Young, S.N. Waveform Analysis for Short Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) Probes to Obtain Calibrated Moisture Measurements from Partial Vertical Sensor Insertions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahuguna, R.N.; Jagadish, K.S.V. Temperature Regulation of Plant Phenological Development. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 111, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.N. Resonance-Interference Concurrent Fiber Sensor: Enabling Simultaneous Detection of Temperature and Humidity. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 440, 137888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogena, H.R.; Huisman, J.A.; Schilling, B.; Weuthen, A.; Vereecken, H. Effective Calibration of Low-Cost Soil Water Content Sensors. Sensors 2017, 17, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, G.; Qian, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y. A Novel Ratiometric Fluorescent Sensor from Modified Coumarin-Grafted Cellulose for Precise PH Detection in Strongly Alkaline Conditions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chao, D.; Yu, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Tian, L.; Zhou, L. One-Pot Synthesis of Multicolor Carbon Quantum Dots: One as PH Sensor, One with Ultra-Narrow Emission as Fluorescent Sensor for Uric Acid. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 213, 111201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Dubey, S.K.; Goel, S.; Kalita, P.K. Portable Sensors in Precision Agriculture: Assessing Advances and Challenges in Soil Nutrient Determination. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 180, 117981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiang, J.; Xue, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ma, X.; Ge, L.; Li, F.; Gai, P. Plant Wearable Sensor Based on Flexible Laser-Induced Fe-Doped Graphene for in Situ Monitoring Salicylic Acid under Salt Stress. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 440, 137931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhao, S.; Feng, X.; He, Y. Transfer Learning Method for Plastic Pollution Evaluation in Soil Using NIR Sensor. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaytsev, V.; Issainova, A.; Borisov, R.S.; Shi, X.; Baideldinov, M.U.; Zimens, M.E.; Zhunusbekov, A.M.; Lantsberg, A.V.; Kondrashov, V.A.; Nasibulin, A.G.; et al. Coding Smell Patterns of Crude Oil by the Electronic Nose: A Soil Pollution Case. J. Hazard Mater. 2024, 480, 135838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.; Qiu, J.; Hao, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Ruan, X.; Zhang, T.; Yao, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. Flexible Self-Decoupled Pressure/Proximity/Temperature Sensor for Composite Stimulus Sensing with Low Signal Crosstalk. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.Y.; Then, Y.L.; Lew, Y.L.; Tay, F.S. Newly Calibrated Analytical Models for Soil Moisture Content and PH Value by Low-Cost YL-69 Hygrometer Sensor. Measurement 2019, 134, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, B.; Ali, N.; Dong, Y. Methods to Correct Temperature-Induced Changes of Soil Moisture Sensors to Improve Accuracy. MethodsX 2025, 14, 103100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahuja, R. Development of Semi-Automatic Recalibration System and Curve-Fit Models for Smart Soil Moisture Sensor. Measurement 2022, 203, 111907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Mansfield, K.; Saafi, M.; Colman, T.; Romine, P. Measuring Soil Temperature and Moisture Using Wireless MEMS Sensors. Measurement 2008, 41, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, M.; Bradley, M.; McCaul, M.; McCrudden, D. A Low-Cost Portable System for on-Site Detection of Soil PH and Potassium Levels Using 3D Printed Sensors. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla, M.; Steijlen, A.; Kerremans, R.; Jacobs, J.; den Haan, L.; De Vreese, J.; Van Noten Géron, Y.; Clerx, P.; Watts, R.; De Wael, K. Wearable Platform Based on 3D-Printed Solid Microneedle Potentiometric PH Sensor for Plant Monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaparthy, V.S.; Singh, D.N.; Baghini, M.S. Compensation of Temperature Effects for In-Situ Soil Moisture Measurement by DPHP Sensors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 141, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lin, C.; Han, Z.; Fu, C.; Huang, D.; Cheng, H. Dissolved Nitrogen in Salt-Affected Soils Reclaimed by Planting Rice: How Is It Influenced by Soil Physicochemical Properties? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Sharma, A.; Tripathi, S.L. Sensors and Their Application. In Electronic Devices, Circuits, and Systems for Biomedical Applications: Challenges and Intelligent Approach; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, J.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, B. Optimization of the Thermal Response Test under Voltage Fluctuations Based on the Infinite Line Source Model. Renew. Energy 2023, 203, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Borisov, S.M. Optical Sensing and Imaging of PH Values: Spectroscopies, Materials, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12357–12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadati, E.; Switalska, E.; Lombi, E.; Warren-Smith, S.C.; Evans, D. Challenges of Polymer-Based PH Sensing in Soil. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Dong, Y.; Rouland, G. Estimation of Deep Percolation in Agricultural Soils Utilizing a Weighing Lysimeter and Soil Moisture Sensors. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 969, 178974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Zubair, M.; Zulfiqar, M.H.; Kamsong, W.; Karuwan, C.; Massoud, Y.; Mehmood, M.Q. Highly Sensitive Screen-Printed Soil Moisture Sensor Array as Green Solutions for Sustainable Precision Agriculture. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 371, 115297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanissery, R.G.; Sims, G.K. Biostimulation for the Enhanced Degradation of Herbicides in Soil. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2011, 2011, 843450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Hansen, H. Development and Design of an Affordable Field Scale Weighing Lysimeter Using a Microcontroller System. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]