Abstract

Alfalfa is a high-quality forage crop whose viscoelastic properties strongly influence the performance of baling, pickup, and stacking operations. In this study, small alfalfa block specimens were tested using a universal testing machine to investigate stress relaxation and creep behaviors under different moisture contents (12%, 15%, 18%), densities (100, 150, 200 kg/m3), and maximum compressive stresses (8, 12, 16 kPa). Experimental data were fitted using viscoelastic models for parameter analysis. Results indicated that the relaxation response consisted of a rapid attenuation followed by a slow stabilization phase. The five-element Maxwell model achieved a higher fitting accuracy (coefficient of determination, R2 > 0.997) than the three-element model. The creep process exhibited three stages, including instantaneous elastic deformation, decelerated creep, and steady-state deformation, and it was accurately represented by the five-element Kelvin model (R2 > 0.998). Increasing moisture content reduced stiffness, while moderate moisture improved viscosity and shape retention. Higher density enhanced blocks compactness, stiffness, and damping characteristics, resulting in smaller deformation. The viscoelastic response to compressive stress showed moderate enhancement followed by attenuation under overload, with the best recovery and deformation resistance observed at 12 kPa. These findings elucidate the viscoelastic behavior of alfalfa blocks and provide theoretical support and engineering guidance for evaluating bale stability and optimizing pickup–clamping parameters.

1. Introduction

Alfalfa is one of the most important high-quality forage crops in modern livestock production, and its harvest is typically performed using mechanized baling to facilitate transportation and storage [1]. Among various bale types, large rectangular bales have become increasingly popular due to their compact structure, high handling efficiency, and ease of stacking [2,3]. However, during the processes of baling, clamping, handling, and stacking, bales often experience deformation or loosening under external loads, which compromises structural stability and increases forage loss, ultimately affecting the efficiency and quality of mechanized operations [4].

Previous studies have shown that the mechanical response of forage bales exhibits typical viscoelastic behavior, which plays a significant role in determining bale forming quality, pickup efficiency, and stacking stability. During stacking and storage, bales are often subjected to sustained compressive loads. Such long-term loading induces pronounced creep deformation, leading to continuous shape changes and decreased structural integrity of the stacked bales. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the viscoelastic response of alfalfa bales under compressive loading is essential for improving the stability of clamping and handling operations, minimizing forage losses, and providing theoretical support for the optimization and design of mechanized equipment used in baling, pickup, and stacking processes.

Extensive research has been conducted on the compressive properties and constitutive modeling of crop straws, hay, and other fibrous or porous agricultural materials. Du et al. [5] analyzed the effects of compression density and moisture content on the stress relaxation behavior of sorghum straw using response surface methodology. Chen et al. [6] examined the influence of moisture content, maximum compressive stress, and feeding rate on the stability of corn-stalk bales under different compression conditions. Talebi et al. [7] investigated the compression and relaxation behavior of sulfate hay and revealed that moisture level, feeding rate, and loading condition significantly affect its viscoelastic response. These studies indicate that the relaxation and creep behavior of bales are closely related to moisture content, density, and stress levels.

To characterize the viscoelastic behavior of crop materials under complex loading conditions, many researchers have employed combined Maxwell and Kelvin models to describe stress relaxation and creep behavior. Jia et al. [8] applied the Burgers and Wiechert-B constitutive models to analyze the pressure-holding and shape-retention stages of compressed corn-stalk blocks, revealing the influence of stabilization processes on post-compaction density and dimensional stability. Fang et al. [9] investigated the compression and relaxation behavior of alfalfa round bales using multiple compression models and a generalized Maxwell model, considering moisture content, feed rate, and roller speed. Joyner et al. [10] proposed a combined generalized Maxwell–plastic element model to predict and characterize the uniaxial compression and stress relaxation of sugarcane residue with high accuracy.

Although these studies provide valuable insights into the viscoelasticity of crop materials, research specifically focused on rectangular alfalfa bales during clamping and handling remains limited. Most existing works address general straw materials or round-bale forming processes, without systematically linking relaxation and creep behavior to the entire sequence of clamping, handling, and stacking operations. Consequently, there is a lack of comprehensive data and models to guide the mechanical modeling and operational optimization of alfalfa bale handling systems.

Therefore, this study focuses on formed alfalfa blocks and systematically investigates their stress relaxation and creep behavior under compressive loading conditions relevant to mechanized picking and handling operations. Stress relaxation and creep tests were conducted to analyze the time-dependent mechanical responses of alfalfa blocks under different moisture contents, densities, and maximum compressive stress levels. Experimental data were fitted using generalized viscoelastic constitutive models to quantitatively characterize the variation in key viscoelastic parameters and to reveal the effects of critical operating parameters on relaxation and creep behavior. The objective of this study is to provide experimental evidence and engineering guidance for evaluating the structural stability of rectangular alfalfa bales during clamping and handling operations and for optimizing the operating parameters of clamping devices, thereby improving the stability and quality of mechanized forage operations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Equipment

The alfalfa used in this study was harvested and baled in 2024 in Binzhou City, Shandong Province, China. According to the ASABE standard S358.2 [11], the moisture content of the alfalfa was determined using a drying oven method, yielding an average value of approximately 14.7%. The mean stem length was about 10.7 cm. The test specimens were prepared by compacting the forage into square blocks with fixed dimensions of 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm using a custom-designed steel mold, which were used to represent the material state of alfalfa after bale formation. During specimen preparation, since the specimen volume was predetermined, the required filling mass was calculated based on the target density and evenly divided into several portions. These portions were successively placed into the mold in layers, and a multiple-step compaction procedure was applied to complete the formation of the alfalfa blocks, thereby improving the uniformity of internal density distribution and ensuring specimen consistency.

One side of the mold was fitted with a transparent acrylic plate, which allowed direct observation of the deformation behavior of the stems during compression. For moisture conditioning, low-moisture samples were obtained by natural air-drying, and the moisture content was measured every 15 min to ensure precision. Medium- and high-moisture samples were prepared by uniformly spraying water onto the dried forage, which was then sealed in airtight plastic bags and stored at 4 °C for 24 h to achieve moisture equilibrium. The amount of water added was calculated using the following equation [12]:

where is the mass of water to be added (g), is the initial sample mass (g), is the initial moisture content (%), and is the target moisture content (%).

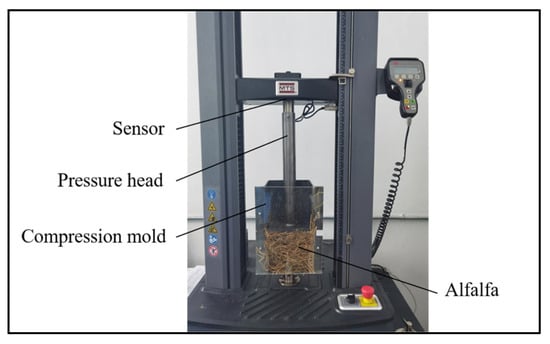

The compression tests were conducted using an E43.104 electronic universal testing machine (maximum load capacity of 10 kN), manufactured by MTS Systems Corporation (Shenzhen, China), and equipped with a force sensor of ±0.5% accuracy. The displacement was continuously monitored by an encoder with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. Each specimen was placed in a steel mold with dimensions of 150 × 150 × 300 mm, and a rigid compression platen with a cross-section of 149 × 149 mm was employed to ensure uniform loading. The entire testing system was computer-controlled, allowing real-time acquisition of time, load, and displacement data throughout the compression process. The experimental setup, including the universal testing machine and the compression fixture, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Compression test device.

2.2. Experimental Design

In this study, moisture content, density, and compressive stress were selected as the key experimental variables, as they directly influence the viscoelastic behavior and internal pore structure of alfalfa bales [13,14]. Moisture content during baling is typically maintained at approximately 14–16% [15]. Accordingly, three levels (12%, 15%, and 18%) were adopted to represent common conditions ranging from relatively dry to moderately moist bales. Bale density determines fiber contact compactness and is closely associated with structural stability, compressive strength, and clamping durability. Based on technical specifications for alfalfa bale production, three density levels, 100, 150, and 200 kg/m3, were selected to cover typical practical operating ranges [16].The maximum compressive stress was set to 8, 12, and 16 kPa. Among these, 12 kPa was defined as the reference level based on force analysis under practical clamping and handling conditions. A typical 500 kg large rectangular alfalfa bale was considered [17], assuming symmetric lifting by clamping arms on both sides. Under given friction conditions, the minimum clamping force required to prevent slippage was estimated using static equilibrium and converted into an equivalent average compressive stress of approximately 12 kPa. The other two levels represent insufficient (8 kPa) and safe (16 kPa) clamping conditions.

In this study, the applied compressive stress was calculated as the ratio of the applied force to the frontal area of the specimen. This definition was adopted to characterize the macroscopic mechanical response of formed alfalfa blocks under compressive loading conditions associated with clamping operations. Each experimental condition was repeated three times, and the average values were used for analysis.

2.3. Stress Relaxation Test

Stress relaxation tests were performed under a constant strain loading mode to characterize the time-dependent mechanical response of formed alfalfa blocks under clamping and handling conditions. The loading rate was set to 80 mm min−1 [18], which represents the typical rapid loading characteristics experienced by bales during mechanical clamping and handling operations. Once the target stress level was reached, the displacement was held constant for 60 s before unloading the compression head [19]. This holding duration was determined based on the typical operation time required for a single bale from gripping to stacking during field operations and was sufficient to capture the most pronounced initial stage of stress decay in alfalfa materials.

The stress–time decay curve was recorded to characterize the reduction in load-bearing capacity under constant deformation conditions. Analysis of the stress relaxation behavior provides insights into the internal friction mechanisms and structural rearrangement of fiber assemblies within the bale under external loading.

2.4. Creep Test

Creep tests were performed under a constant stress loading mode. Samples were loaded to the target stress level and maintained for 60 s, after which the compression head was unloaded. The time-dependent strain was recorded to analyze deformation behavior under sustained loading. Creep behavior reflects the delayed deformation of formed alfalfa blocks under constant load [20], which is critical for assessing the structural stability of bales during stacking and long-term storage.

2.5. Viscoelastic Modeling

Constitutive models for viscoelastic materials have been extensively studied. The classical Maxwell model, consisting of a spring and a dashpot in series, accurately captures both elastic and viscous deformation [21]. The generalized Maxwell model, composed of multiple Maxwell units in parallel, is widely used to describe stress relaxation behavior and to determine material parameters such as the elastic modulus during the relaxation process [14,22,23]. In this study, stress–time curves obtained from experiments were fitted using the generalized Maxwell model to characterize relaxation behavior.

The Kelvin model, consisting of a spring and a dashpot in parallel, and its generalized form, which comprises an instantaneous spring in series with multiple Kelvin units, can capture time-dependent deformation at multiple scales [24,25]. To describe the creep behavior of alfalfa bales under constant loading and form a complementary model framework with the characterization of relaxation characteristics, the generalized Kelvin model was employed to fit the experimental strain–time curves. It should be noted that under clamping, handling, and short-term load-holding conditions after bale formation, the viscoelastic models employed in this study are not intended to describe the large irreversible elastoplastic deformations involved in the bale compaction and forming stage. Instead, they are used to effectively characterize the stress relaxation and creep behavior of alfalfa blocks within the stress range considered in this study.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments in this study were independently repeated three times. The repeatability and reliability of the experimental data were evaluated using the coefficient of variation (CV). Experimental data were fitted using the nonlinear fitting module of Origin 8.0 software based on the Levenberg–Marquardt least-squares algorithm [26]. For the modeling analysis of stress relaxation and creep curves, the fitting accuracy of the models was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2) and the root mean square error (RMSE). The model showing better fitting performance was subsequently applied to analyze the experimental data obtained under different moisture contents, densities, and maximum compressive stress levels. The corresponding viscoelastic parameters were determined, and the effects of these factors on the viscoelastic response of alfalfa blocks were investigated through comparisons of the model parameters.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Compression Process Analysis

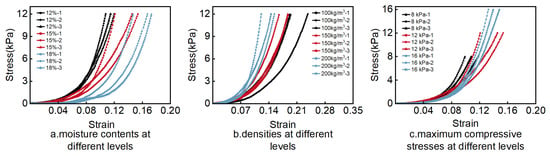

Alfalfa block exhibited typical nonlinear viscoelastic behavior under uniaxial compression. Figure 2 presents the stress–strain curves under varying moisture contents (12%, 15%, 18%), densities (100, 150, 200 kg/m3), and maximum compressive stresses (8, 12, 16 kPa). Overall, the curve trends were consistent across the different factors. During the initial stage of compression, stress increased gradually, primarily due to the elimination of inter-stem voids and the progressive contact between fibers. In the later stage, stress rose sharply, which can be attributed to fiber interlocking, adhesion, and even structural damage [27].

Figure 2.

Stress–strain curves obtained under various compression conditions.

As shown in Figure 2a, significant differences in stress–strain behavior were observed for samples with 12%, 15%, and 18% moisture content. At the same stress, higher moisture content samples exhibited larger strains, indicating that the structure deforms more readily. This behavior is primarily caused by the lubricating and softening effects of water on the internal block structure [28], which enhance inter-fiber sliding while facilitating fiber misalignment and local collapse during compression [29].

Figure 2b illustrates the effect of initial density (100, 150, 200 kg/m3) on compression behavior under a constant moisture content of 15% and a compressive stress of 12 kPa. The results indicate that increasing density significantly accelerates the slope of the stress–strain curve. High-density samples generated substantial stress at small strains, reflecting superior compressive resistance. This behavior is mainly attributed to the reduced porosity and increased fiber contact at higher densities, which enhances load transfer efficiency [30,31]. Conversely, low-density blocks possess looser structures and higher porosity; their initial compression is dominated by structural rearrangement, resulting in lower resistance and more “compliant” deformation.

As shown in Figure 2c, the stress–strain curves under three maximum compressive stress levels (8, 12, and 16 kPa) are presented for alfalfa blocks with a moisture content of 15% and a density of 200 kg m−3. In the initial compression stage (strain < 0.05), the curves exhibit a high degree of overlap, indicating that the early mechanical response is mainly governed by fiber rearrangement and pore elimination, without pronounced compression hardening. It should be noted that, under the 8 kPa condition, several repeated curves show a slightly higher slope in the low-stress regime. This behavior is primarily attributed to the inherent anisotropy of the internal structure of alfalfa blocks and the high sensitivity of the initial densification stage to contact establishment at the loading surfaces and local variations in fiber packing density. By contrast, under the 12 and 16 kPa conditions, as compression progresses into a deeper densification stage, these early-stage differences are gradually diminished [7]. Overall, the magnitude of this variation is limited, remaining within approximately 5%, which is considered acceptable for engineering analysis. With further loading, the contact area between stems increases and the structure becomes more compact, resulting in evident compression hardening and a marked increase in the slope of the stress–strain curves.

The above analysis indicates that the deformation of alfalfa blocks depends not only on the magnitude of the external load but also on the loading duration and internal structural characteristics [32,33,34]. An increase in moisture content reduces the block stiffness, while higher density enhances its compressive resistance. Moreover, the level of maximum compressive stress determines the degree of compression hardening. These findings provide a structural basis for interpreting the subsequent differences observed in stress relaxation and creep behavior.

3.2. Stress Relaxation Behavior Analysis and Model Representation

3.2.1. Analysis of Stress Relaxation Tests

Before analyzing the stress relaxation behavior, it is noteworthy that slight discrepancies exist among the repeated compression curves. These variations mainly arise from the continuous structural reorganization of the fibrous material during compression, accompanied by the bending, folding, and partial fracture of rod-like particles, which gradually increase the proportion of plastic deformation [35]. Although this process enhances material densification, the randomness of plastic failure and structural rearrangement results in poor repeatability of the compression curves. In contrast, during the subsequent stress relaxation phase, the plastic deformation remains nearly constant and the internal structure becomes relatively stable. The relaxation process is primarily governed by viscoelastic mechanisms, resulting in smoother curves with improved repeatability [8,10].

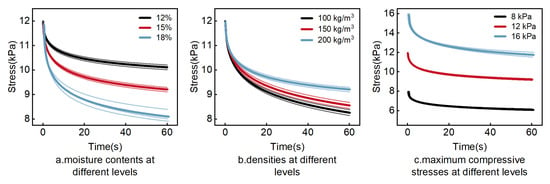

Figure 3 presents the stress relaxation curves of alfalfa block under varying densities (100, 150, 200 kg/m3), moisture contents (12%, 15%, 18%), and maximum compressive stresses (8, 12, 16 kPa). To evaluate data consistency, the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated for each condition, all of which were below 5%, indicating good repeatability and reliable measurements. Across all experimental groups, stress exhibited a clear decay over time, demonstrating typical viscoelastic relaxation behavior. The overall response can be characterized by two stages: an initial rapid stress decay followed by a slower relaxation phase, eventually reaching a quasi-steady state. This behavior is primarily attributed to the time-dependent adjustment of the fiber network structure [36]. In the initial stage, fiber bundles undergo relative sliding and compression-aligned movement to release internal stresses. In the later stage, the limited mobility of fibers and inter-fiber friction impede further sliding, causing the relaxation rate to gradually decrease until stabilization is achieved [14,19].

Figure 3.

Stress relaxation curves under different compression conditions. Thin solid lines represent three repeated tests, and the thick solid line represents the mean curve.

Significant differences in relaxation rate and residual stress levels were observed under different treatment conditions. As shown in Figure 3a, at a fixed density of 200 kg/m3 and compressive stress of 12 kPa, increasing moisture content led to a markedly larger stress relaxation amplitude and a reduction in residual stress proportion. Notably, the 18% moisture sample exhibited the most pronounced decrease in residual stress, indicating that higher moisture levels facilitate more extensive fiber sliding and rearrangement, resulting in rapid release of stored internal energy. Figure 3b illustrates that, under constant moisture content and compressive stress, increasing the density to 200 kg/m3 elevated the overall stress level while slightly reducing relaxation extent. High-density bales possess a more compact internal structure, which restricts fiber rearrangement and sliding, thereby inhibiting rapid stress decay. Furthermore, at identical compressive stress, high-density blocks maintained higher residual stress, demonstrating that structural densification significantly enhances load retention capacity.

The stress relaxation behavior of the alfalfa blocks was markedly influenced by the maximum compressive stress. As shown in Figure 3c, when the initial compressive stress increased from 8 kPa to 16 kPa, the residual stress within the compressed samples became larger [7,19], and the proportion of stress decay during the relaxation process rose substantially. This indicates that higher loading stress intensifies fiber–fiber contact, interlocking, and localized structural damage, thereby accelerating the internal structural rearrangement and energy dissipation during the constant-strain phase [37].

3.2.2. Relaxation Model Fitting and Parameter Comparison

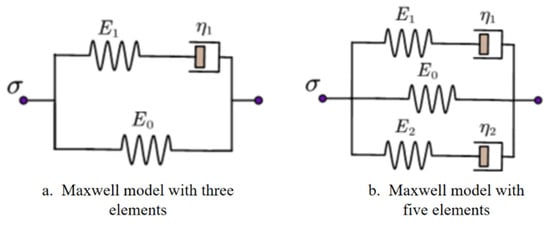

To quantitatively characterize the stress relaxation behavior of alfalfa blocks, constitutive models are commonly employed for mathematical fitting. The generalized Maxwell model has been demonstrated to effectively describe the stress relaxation of plant fiber materials and to extract key parameters such as the instantaneous modulus, delayed modulus, and relaxation times. Considering that alfalfa blocks exhibit both short-term and long-term relaxation characteristics, the present study fitted the experimentally obtained stress–time curves using both a three-element (Figure 4a) and a five-element (Figure 4b) generalized Maxwell model, allowing a comparative assessment of model applicability and fitting accuracy.

Figure 4.

Stress relaxation mechanical model.

The stress relaxation equation of the three-element generalized Maxwell model can be described by Equation (2) [38,39]. The five-element generalized Maxwell model extends the three-element model by adding an additional Maxwell element in parallel. Its stress relaxation equation is described by Equation (3) [38,39].

where represents the stress at a maintained strain time of t (s), and is the initial strain. Here, , , and represent the relaxation times of the Maxwell elements, reflecting the stability of the block under sustained deformation. and are the viscosity coefficients, describing energy dissipation due to fiber–fiber friction and internal structural rearrangement. and denote the elastic moduli of the relaxation branches and represent the slow load-bearing capacity of the fiber bundles over longer time scales. reflects the instantaneous rigidity of the block’s fiber skeleton upon loading.

It should be noted that, due to the exponential form of Equation (3), the stress exhibits an asymptotic decay behavior with increasing time and can only approach a stable value rather than completely vanish within a finite duration. This characteristic is an inherent mathematical feature of the generalized Maxwell model and defines its applicability for describing stress relaxation behavior of alfalfa blocks over practical engineering time scales.

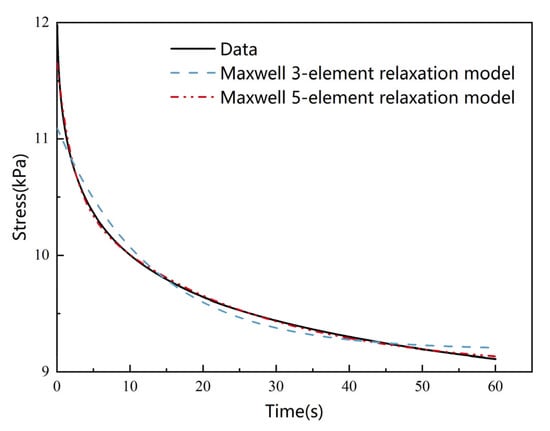

The averaged stress–time data at a moisture content of 15%, a density of 200 kg/m3, and a maximum compressive stress of 12 kPa were fitted using the three-element generalized Maxwell model (Figure 4a) and the five-element generalized Maxwell model (Figure 4b). The fitting results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Fitted curves of stress relaxation models.

The three-element Maxwell model achieved an R2 of 0.973 and an RMSE of 0.0797, indicating that it could adequately capture the stress relaxation behavior of the alfalfa bale. However, noticeable deviations between the fitted and experimental data were still observed.

By contrast, the five-element Maxwell model exhibited a significantly higher goodness of fit (R2 = 0.998) and a lower RMSE (0.0172). The fitting error was significantly reduced, and the residuals exhibited smaller magnitudes and a more uniform distribution. These results demonstrate that the five-element model provides greater fitting stability and accuracy throughout the entire relaxation process. Moreover, the additional viscoelastic element introduced in the five-element Maxwell model has a clear physical interpretation, allowing the model to represent the multi-stage relaxation responses of alfalfa at different time scales more realistically. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Du et al. in their study on the stress relaxation characteristics of sweet sorghum [40].Therefore, the five-element generalized Maxwell model was selected to establish the constitutive model for the relaxation stage. By fitting the relaxation curves under different moisture contents, the model parameters were obtained as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Effect of moisture content on the parameters of the five-element generalized Maxwell model.

The stress relaxation curves of alfalfa blocks under different moisture contents were accurately fitted using the five-element generalized Maxwell model, with coefficients of determination (R2) exceeding 0.997, and the fitting accuracy remained stable across all tested moisture conditions. As shown in Table 1, the instantaneous modulus was relatively high at low moisture content (12%), indicating a slower stress decay. In contrast, at high moisture content (18%), the relaxation time and was significantly shortened, and stress was released rapidly within a short duration. This observation suggests that increasing moisture weakens the instantaneous load-bearing capacity of the block and facilitates internal fiber slippage, leading to greater elastic deformation at the initial loading stage [41,42]. This trend is consistent with the findings of Talebi et al. on timothy hay [7], who reported that high-moisture samples exhibited approximately 10% greater stress relaxation compared to low-moisture samples, confirming that moisture is a key factor enhancing the viscoelastic response of plant-based materials.

At moderate moisture content (15%), the viscosity coefficient reached its maximum value. This behavior is closely associated with the microstructural arrangement of fibers and the distribution of moisture within the block. Under moderate moisture conditions, an appropriate amount of water within the fiber interstices enhances inter-fiber friction and promotes more uniform stress transmission, thereby restricting the free slippage of fiber bundles and resulting in greater damping and energy dissipation capacity. However, excessive moisture forms a lubrication layer at fiber interfaces [43], which reduces inter-fiber entanglement and frictional resistance, accelerates internal slippage, and consequently manifests as shortened relaxation times and reduced viscous resistance [40]. This pattern indicates that, in practical baling and handling operations, maintaining an optimal moisture level not only mitigates block deformation but also enhances the sustained stability of the clamping arms during gripping and transport.

The stress relaxation behavior of alfalfa blocks under different densities was well characterized by the five-element generalized Maxwell model, with coefficients of determination (R2) all exceeding 0.998. As shown in Table 2, as the density increased from 100 to 200 kg/m3, both the delayed elastic moduli ( and ) and the instantaneous modulus () exhibited significant increases. This trend indicates that structural densification markedly enhances the instantaneous load-bearing capacity and overall stiffness, resulting in a stronger resistance to stress relaxation during the initial loading stage. Meanwhile, the viscosity coefficients ( and ) also increased substantially with density, implying that higher compaction intensifies inter-fiber friction and internal flow resistance.

Table 2.

Effect of density on the parameters of the five-element generalized Maxwell model.

These variations suggest that increasing density leads to tighter fiber packing, reduced porosity, and constrained fiber rearrangement within the block, thereby producing a high-stiffness–high-damping viscoelastic response [44,45]. Such a structural advantage is beneficial for maintaining bale integrity and mechanical stability during clamping and handling operations, effectively reducing instability and energy loss caused by deformation during transport.

Table 3 presents the stress relaxation parameters of alfalfa blocks under different compressive stress levels. When the stress increased from 8 kPa to 12 kPa, both the instantaneous modulus () and the delayed modulus ( and ) increased. The viscosity coefficient ( and ) also became larger. This indicates that moderate loading improved the contact and interlocking between fibers. The block could carry the load more effectively and maintained a more stable internal structure.

Table 3.

Effect of maximum compressive stress on the parameters of the five-element generalized Maxwell model.

However, when the stress further increased to 16 kPa, both modulus and viscosity decreased sharply. Excessive stress caused internal structural damage and accelerated stress relaxation. As a result, the load-holding capacity weakened [46,47]. Jia et al. [8] found a similar trend in corn stalk blocks, where higher compressive stress enhanced elastic, viscoelastic, and viscous properties. The different response observed in alfalfa may be due to its more flexible fiber structure and compact texture, which make it sensitive to damage under high stress. The viscoelastic response of alfalfa showed a clear nonlinear dependence on compressive stress. The maximum compressive stress was around 12 kPa, where the block can achieve relatively high load-bearing capacity while avoiding structural damage.

The stress relaxation curves under different moisture contents, densities, and compressive stresses were all well fitted by the five-element generalized Maxwell model. This confirms that the model can accurately describe the viscoelastic behavior of fibrous biomass. Increasing the moisture content reduced the instantaneous modulus but increased the delayed modulus. This reflects a transition from a rigidity-dominated response to a fluidity-dominated one. Increasing the block density raised both modulus and viscosity coefficients, showing stronger resistance to stress relaxation. This means the material became more rigid and less deformable. The influence of compressive stress was nonlinear. Optimal viscoelastic properties are observed at approximately 12 kPa.

Overall, the relaxation characteristics of alfalfa bales are influenced not only by moisture content and density but also exhibit pronounced stress sensitivity, revealing a viscoelastic mechanism governed by a coupled “rigidity–viscosity” interaction.

3.3. Creep Behavior Analysis and Model Representation

3.3.1. Analysis of Creep Tests

To evaluate data consistency, the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated for each condition, all of which were below 10%, indicating good experimental repeatability and reliable measurements. During the creep process, the deformation of alfalfa stem material was mainly governed by viscoelastic mechanisms. However, under sustained loading, gradual internal damage accumulation and irreversible deformation occurred, leading to a slight increase in the proportion of plastic strain [48].Consequently, the creep curves exhibited slightly lower repeatability than the stress relaxation curves, but the overall differences remained small, confirming the good consistency and reliability of the experimental data.

During the constant strain stage, the primary reaction force originated from the interactions among internal fibers within the block. To simplify the modeling and computation, the friction between the block and the wall was neglected [8,24].

Overall, the strain gradually increased with time and eventually reached a steady state. In the initial stage, the material exhibited a rapid instantaneous deformation, followed by a progressively decreasing strain rate until stabilization. This behavior indicates that the internal fiber network of the alfalfa block underwent rapid rearrangement and close contact at the onset of compression. Subsequently, the frictional resistance and interfacial bonding between fibers restricted further deformation, resulting in a gradual transition to structural stability. Such a trend is consistent with the viscoelastic deformation behavior observed in most fibrous plant materials [14,49].

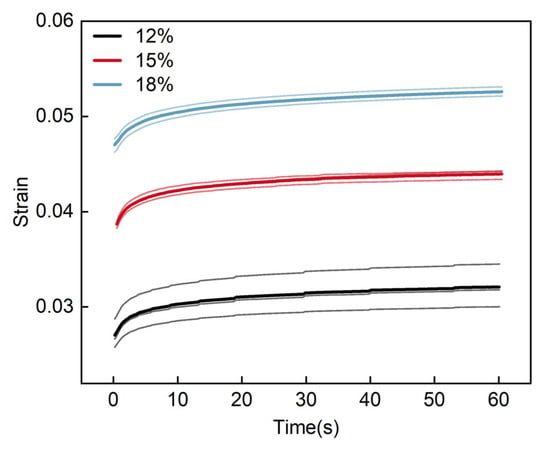

As shown in Figure 6, under identical stress and density conditions, the deformation of the alfalfa block increased significantly with higher moisture content. The initial deformation was more pronounced, suggesting that the block became more susceptible to compression.

Figure 6.

Creep curves under different moisture contents. Thin solid lines represent three repeated tests, and the thick solid line represents the mean curve.

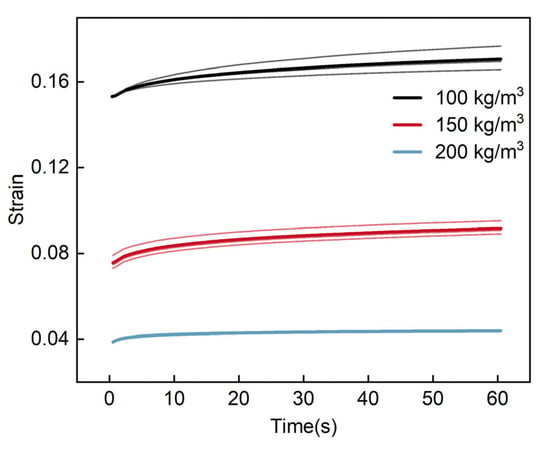

Figure 7 illustrates that as the density increased from 100 kg/m3 to 200 kg/m3, the initial strain markedly decreased, and the creep curve exhibited a lower growth rate. This finding indicates that a higher density leads to a more compact structure with reduced porosity and smaller interparticle compression spaces. Consequently, the slow structural adjustment during creep was suppressed, enhancing the resistance to deformation.

Figure 7.

Creep curves under different densities. Thin solid lines represent three repeated tests, and the thick solid line represents the mean curve.

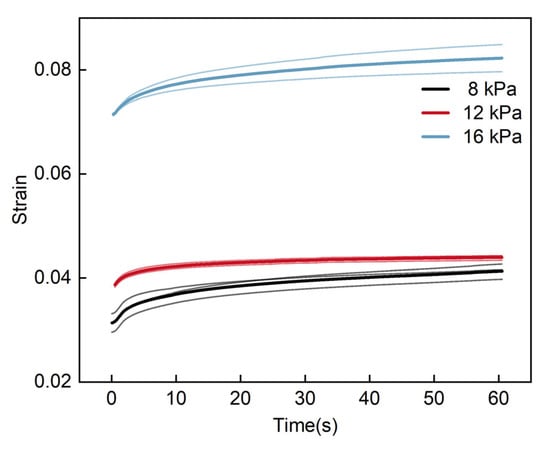

As presented in Figure 8, at a moisture content of 15% and density of 200 kg/m3, a higher compressive stress resulted in a larger initial strain. Greater loading stress induced more significant deformation. During the 60 s loading period, the strain at 16 kPa was much higher than that of other groups, suggesting that the block structure became looser under higher initial compression, allowing more internal rearrangement. However, during the subsequent holding phase, the creep strain did not increase monotonically with stress. At 12 kPa, the creep strain was relatively lower than that at 8 kPa and 16 kPa, indicating that the block exhibited greater structural stability under this intermediate stress level.

Figure 8.

Creep curves under different maximum compressive stresses. Thin solid lines represent three repeated tests, and the thick solid line represents the mean curve.

3.3.2. Creep Model Fitting and Parameter Comparison

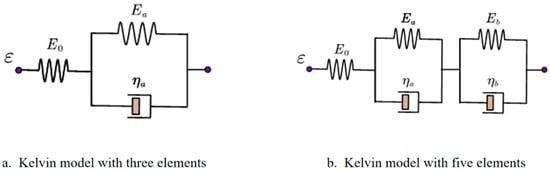

Accordingly, to quantitatively characterize the creep behavior of alfalfa under constant load, the three-element and five-element generalized Kelvin models were employed for fitting. Both models can effectively describe the instantaneous elastic response, delayed elastic relaxation, and viscous flow behavior, and have been widely applied in the study of mechanical properties of plant fibers and biomass materials [8].

The three-element generalized Kelvin model (Figure 9a) consists of an instantaneous spring and a Kelvin unit, which can describe the instantaneous deformation and the delayed deformation with a single time scale. Its constitutive equation is expressed as Equation (4) [8,25]. The five-element generalized Kelvin model (Figure 9b) is developed by adding an additional Kelvin unit to the three-element model. It includes two sets of retardation moduli and viscosity coefficients, and its constitutive equation is expressed as Equation (5) [25,50].

where is the constant stress, is the instantaneous elastic modulus, and (i = 1, 2) denote the elastic modulus and viscosity coefficients of the respective viscoelastic branches, and represent the retardation times, which reflect the delayed elastic behavior on multiple time scales.

Figure 9.

Creep mechanical model.

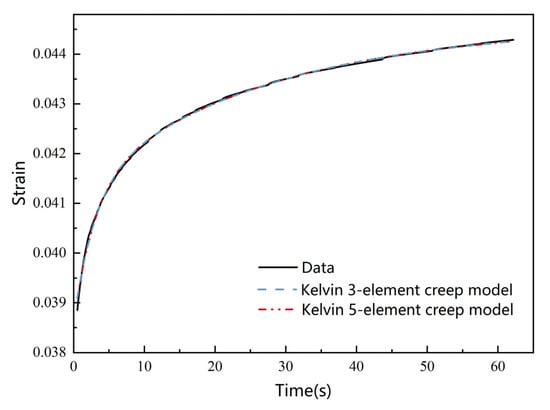

The averaged experimental data obtained under a moisture content of 15%, density of 200 kg/m3, and maximum compressive stress of 12 kPa were fitted using the three-element generalized Kelvin model (Figure 9a) and the five-element generalized Kelvin model (Figure 9b). The fitting results are presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Fitted curves of creep models.

As shown in Figure 10, both models accurately described the strain–time response of alfalfa blocks under uniaxial compression, and the fitted curves exhibited a high degree of agreement with the experimental data. However, in terms of goodness of fit, the three-element Kelvin model yielded an R2 of 0.980 and an RMSE of 1.50 × 10−4, whereas the five-element Kelvin model achieved a significantly higher R2 of 0.999 and a much lower RMSE of 2.87 × 10−5, reflecting a substantially smaller prediction error in engineering terms. This result demonstrates that the five-element Kelvin model provides a markedly better fit to the creep data and offers superior fitting accuracy and stability throughout the entire creep process, thereby enabling a more accurate representation of the viscoelastic creep behavior of alfalfa blocks.

The three-element model contains only one viscoelastic element, which can capture a single creep process. As a result, it tends to deviate in the initial stage of rapid strain growth and the later stage of slow deformation. In contrast, the five-element model includes two viscoelastic units, enabling it to characterize both the short-term rapid creep and long-term slow creep behaviors. This dual response better represents the complex multiscale structure of alfalfa blocks.

Therefore, the five-element generalized Kelvin model provides a more reasonable and accurate description of the viscoelastic response of alfalfa blocks during compression. The fitting parameters of the five-element generalized Kelvin model for the three single-factor series (moisture content, density, and maximum compressive stress) are summarized in the following tables, with the fitting accuracy remaining stable across all tested conditions.

The creep parameters of alfalfa at different moisture contents are shown in Table 4. As the moisture content increased from 12% to 18%, the instantaneous elastic modulus () gradually decreased, indicating a reduction in structural stiffness and a higher tendency for deformation during the initial loading stage. The delayed elastic modulus () first increased and then decreased, while showed a continuous downward trend. Excessive moisture weakened the material’s resistance to long-term deformation under sustained loading [47,51].

Table 4.

Effect of moisture content the parameters of the five-element generalized Kelvin model.

The viscosity coefficients ( and ) remained relatively high, reaching their maximum at 15% moisture content. At moderate moisture levels, the internal friction and damping effect within the block were enhanced, which helped maintain its shape. Meanwhile, the retardation time constants ( and ) increased with moisture content, suggesting that strain stabilization occurred more slowly and the material exhibited a more pronounced viscoelastic lag effect under high moisture conditions.

Overall, the effect of moisture content on the creep behavior of alfalfa can be summarized as elasticity weakening—viscosity strengthening. At a moderate moisture content (around 15%), the block maintained suitable stiffness while providing good buffering capacity. However, excessive moisture led to reduced structural stability, which may compromise the safety and integrity of bale stacking and transportation operations.

As shown in Table 5, with increasing density, the instantaneous elastic modulus () and the delayed elastic moduli ( and ) increased significantly. The alfalfa blocks became more compact under compression, with reduced pore space and enhanced inter-fiber support and interlocking, thereby improving their resistance to both instantaneous and long-term deformation. Meanwhile, the retardation time constants ( and ) decreased at higher densities, indicating that the compacted structure reached a stable creep stage more rapidly. This is consistent with the characteristics of closely packed fibers and limited deformation space under high-density conditions [14].

Table 5.

Effect of density on the parameters of the five-element generalized Kelvin model.

The viscosity coefficients ( and ) also increased markedly with density. Higher density led to larger contact areas between stems and stronger frictional interactions, resulting in greater viscous damping effects. This finding differs from some studies based on the Burgers model, in which η decreases with increasing density [12,24]. The difference mainly arises from the distinct model definitions: in the generalized Kelvin model, η represents recoverable damping capability, whereas in the Burgers model, η typically denotes irreversible viscous resistance. Therefore, the observed increase in η under high-density conditions reasonably reflects the high-damping and low-flow characteristics of alfalfa under strong compaction, suggesting enhanced viscoelastic delay and energy dissipation during clamping and handling.

This synergistic effect of “stiffness enhancement and damping reinforcement” is the fundamental reason for the improved creep performance of high-density blocks. Due to their compact structure, high-density bales better resist deformation during clamping and maintain their shape more effectively during stacking. Thus, appropriately increasing bale density during the baling process can balance clamping stability and structural protection, thereby improving pickup efficiency.

The variation in loading force does not fundamentally alter the intrinsic physical properties of the material [12,24], but it significantly affects its macroscopic compression response. The creep characteristic parameters of alfalfa under different maximum compressive stresses are presented in Table 6. As the maximum compressive stress increased from 8 kPa to 12 kPa, the instantaneous elastic modulus (), delayed elastic moduli ( and ), and viscosity coefficients ( and ) all increased notably. This indicates that a moderate load contributes to compacting the fiber network, thereby enhancing the material’s instantaneous resistance to deformation and its long-term load-bearing capacity [8]. However, when the compressive stress was further increased to 16 kPa, these parameters decreased, suggesting that excessive loading caused damage to the fiber structure, reducing the number of effective load-bearing paths and consequently weakening the overall stiffness [47].

Table 6.

Effect of maximum compressive stress on the parameters of the five-element generalized Kelvin model.

The retardation time constants ( and ) were shorter under moderate stress, indicating that the structure reached a steady-state creep stage more rapidly. In contrast, both low and high stress levels led to prolonged retardation times, corresponding, respectively, to incomplete compaction and structural damage resulting in slow deformation. The effect of maximum compressive stress on the creep characteristics of alfalfa blocks thus follows a trend of moderate enhancement but overload weakening, which is consistent with the results observed in the stress relaxation experiments. During pickup and clamping operations, an appropriate load can effectively improve the stiffness and damping performance of alfalfa blocks, ensuring structural stability while reducing mechanical damage and material loss.

Integrating the results of compression, relaxation, and creep experiments and their corresponding viscoelastic modeling, it is evident that the mechanical response of alfalfa blocks is significantly influenced by moisture content, density, and compressive stress. As the moisture content increases, the inter-fiber bonding strength weakens and internal friction resistance decreases, making the bale more prone to slow deformation or slippage induced by stress relaxation during clamping and handling. Therefore, during harvesting and picking operations, the moisture content should be maintained at a moderate level (approximately 15%) to balance compaction effectiveness and structural stability. Excessive moisture may lead to large deformation, while overly low moisture increases brittleness and compromises structural integrity.

Increasing density significantly enhances the internal compactness and stability of bales, resulting in more uniform stress distribution and reduced deformation during picking and handling. Hence, during the baling process, appropriately increasing the compaction density can produce structurally stable bales, thereby improving bale quality and subsequent operational efficiency.

The viscoelastic response of alfalfa blocks under different maximum compressive stresses exhibits a clear nonlinear behavior. Experimental results show that at a compressive stress of 12 kPa, both viscosity and elasticity parameters reach their peak values, indicating optimal structural resilience and deformation resistance, which are conditions ideal for mechanical picking. In contrast, excessive compressive stress (>16 kPa) can damage the fibrous structure and cause irreversible deformation, reducing stability during subsequent clamping operations. Therefore, during baling and clamping, the applied stress should be carefully selected based on operational requirements to achieve a balance between structural stability and energy efficiency.

During stress relaxation and creep tests, the initial rapid deformation of the blocks occurs within approximately 2 s. As noted by Yang, in engineering tests, the stress relaxation time t is generally taken to exceed 3T [52]. To balance practical operational efficiency, an initial relaxation period of approximately 6 s after clamping allows the rapid relaxation stage to complete before handling, thereby reducing sliding and bale scattering caused by stress decay. This finding has direct practical implications for clamping, handling, and stacking of large square alfalfa bales, providing theoretical guidance for mechanical design and optimization of operational parameters.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the mechanical behavior of alfalfa blocks under clamping and handling conditions by analyzing their uniaxial compression stress relaxation and creep characteristics at different moisture contents, compression densities, and loading stresses. Using generalized viscoelastic models, the time-dependent viscoelastic response of alfalfa blocks was characterized. The results indicate that excessive moisture content reduces load-bearing capacity and intensifies time-dependent deformation, whereas at a moderate moisture level (approximately 15%), alfalfa blocks maintain relatively high load-bearing capacity while effectively dissipating energy, which is beneficial for structural stability during clamping and handling. High-density alfalfa blocks exhibit a combined high-stiffness and high-damping response, as structural densification significantly enhances stiffness and energy dissipation capacity, thereby improving shape stability under loading.

The viscoelastic behavior of alfalfa blocks shows a pronounced nonlinear dependence on compressive stress. At an appropriate maximum compressive stress of approximately 12 kPa, both elastic modulus and viscosity parameters reach relatively high levels, indicating optimal structural stability, whereas excessive stress tends to induce fiber slippage and irreversible deformation, which is detrimental to clamping stability. In addition, experimental results reveal a pronounced rapid deformation stage during the initial loading period. This suggests that, in practical clamping operations, a short stabilization period (approximately 2 s) should be allowed after clamping before handling to reduce the risk of slippage and bale disintegration caused by stress decay. Overall, these findings provide direct mechanical guidance for compaction parameter selection, clamping force control, and structural design of alfalfa bale handling equipment, contributing to improved operational stability and engineering reliability.

It should be noted that the conclusions of this study are primarily based on single-factor experiments conducted under limited operating conditions and linear viscoelastic modeling assumptions, which do not fully account for irreversible plastic deformation and structural damage under high compression levels. These factors define the applicability of the present results under complex loading conditions. Future research may incorporate nonlinear viscoelastic constitutive models and integrate discrete element and finite element simulations to develop coupled moisture–density–stress frameworks for more accurate prediction of viscoelastic responses, thereby providing theoretical support for structural optimization and engineering design in bale compaction, handling, and storage processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., Q.F. and Y.L.; methodology, H.X. and X.Y.; software, H.X. and X.Y.; validation, H.X. and X.Y.; formal analysis, J.H. and H.X.; investigation, J.H. and Y.L.; resources, Q.F. and J.F.; data curation, J.H. and H.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H. and Q.F.; writing—review and editing, J.H. and Y.L.; visualization, X.Y. and J.F.; supervision, Y.L. and J.F.; project administration, Q.F.; funding acquisition, Q.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the project of the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFD2001904) and the Graduate Innovation Fund of Jilin University (Grant No. 2025CX185).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are extended to the research team members for their valuable help in sample preparation, mechanical testing, and result analysis, as well as to the experts who offered constructive comments during manuscript revision. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Borreani, G.; Bisaglia, C.; Tabacco, E. Effects of a new-concept wrapping system on alfalfa round-bale silage. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; He, C.; Wu, H.; You, Y.; Wang, G. Review of Alfalfa Full-mechanized Production Technology. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coblentz, W.K.; Akins, M.S. Silage review: Recent advances and future technologies for baled silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4075–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Mou, X.; Sun, Y.; Geng, D.; Wang, C.; Zhao, N. Experimental study on influencing factors of bale stability. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2021, 42, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Guo, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Jin, M.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Experimental study on stress relaxation characteristics and parameter optimization of forage sweet sorghum stalks. J. China Agric. Univ. 2019, 24, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Jia, H.; Li, M.; Zhao, J.; Deng, J.; Fu, J.; Yuan, H. Mechanism of restraining maize stalk block springback under pressure maintenance/strain maintenance. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, S.; Tabil, L.; Opoku, A.; Shaw, M. Compression and relaxation properties of timothy hay. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2011, 4, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Chen, T.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Yuan, H. Effects of Pressure Maintenance and Strain Maintenance during Compression on Subsequent Dimensional Stability and Density after Relaxation of Blocks of Chopped Corn Straw. Bioresources 2020, 15, 3717–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, A.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Gao, J.; Li, H. Stress relaxation behavior and modeling of alfalfa during rotary compression. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2018, 34, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo-Zuniga, J.; Casanova, F.; Jaime Garcia, J. Visco-elastic-plastic model to represent the compression behaviour of sugarcane agricultural residue. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 212, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASAE S358.2; Moisture Measurement—Forages. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2008.

- Lei, M.; Lei, J.; Luo, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; You, B. Compression Creep Characteristics of Crushed Sugarcane End-Leaves. Bioresources 2024, 19, 4486–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wei, K.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ma, F.; Liu, D. Optimization of process parameters for multi-frequency rapid compression molding of corn stalk silk used for forage. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C. Study on Compression Properties and Rheological Characteristics of Straw Blocks. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NY/T 4338-2023; Technical Specification for Alfalfa Hay-Making. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs: Beijing, China, 2023.

- DB15/T 2664-2022; Technical Regulations for Alfalfa Baling Production. Market Supervision and Administration Bureau of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region: Hohhot, China, 2022.

- Zhang, H.; Liu, T.; Lian, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. Analysis of the Development Prospects of Wrapped Silage Feed Made from Alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Cereal Feed Ind. 2023, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. Experimental Study and Numerical Simulation on Cold Compression Molding of Straw Pellet Fuel. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Wang, D.; Tabil, L.G.; Wang, G. Compression and relaxation properties of selected biomass for briquetting. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 148, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, I.; Fitz, C.; Hofbauer, W.; Klatecki, M.; Krick, B.; Krueger, N.; Krus, M.; Minke, G.; Otto, F.; Scharmer, D. Grundlagen zur Bauaufsichtlichen Anerkennung der Strohballenbauweise-Weiterentwicklung der Lasttragenden Konstruktionsart und Optimierung der Bauphysikalischen Performance; Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt: Osnabrück, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nona, K.D.; Lenaerts, B.; Kayacan, E.; Saeys, W. Bulk compression characteristics of straw and hay. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 118, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, K.; Bilanski, W. Stress relaxation of alfalfa under constant displacement. Trans. ASAE 1991, 34, 2491–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, N.; Chen, L.; Huang, G.; He, C.; Han, L. Grey relation analysis of lignocellulose content and compression stress relaxation of corn stalk. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2011, 42, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Study on Open Compression Creep Test of Crushed Corn Stalks. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Pan, J. Introduction to Agricultural Rheology; Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 1990; pp. 49–63, ISBN/ISSN 7109012107. [Google Scholar]

- Theerarattananoon, K.; Xu, F.; Wilson, J.; Ballard, R.; Mckinney, L.; Staggenborg, S.; Vadlani, P.; Pei, Z.; Wang, D. Physical properties of pellets made from sorghum stalk, corn stover, wheat straw, and big bluestem. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q. Study on Mechanical Properties of Alfalfa and King Grass and Development of a Flexible Cutting Test Bench. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Taian, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H. Multiscale Mechanical Analysis and Parameter Optimization of Alfalfa Compression Molding. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Wear Analysis and Experimental Study of Alfalfa Compression Molding Die Based on EDEM. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maraldi, M.; Molari, L.; Regazzi, N.; Molari, G. Analysis of the parameters affecting the mechanical behaviour of straw bales under compression. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 160, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Lei, D.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z. Stress Relaxation Characteristics of Crushed Cane Tail Straw. BioResources 2023, 18, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cai, D.; Xie, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Chen, L. Parameters Calibration of Discrete Element Model for Corn Stalk Powder Compression Simulation. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-J.; Lei, T.-Z.; Xu, G.-Y.; Shen, S.-Q.; Liu, J.-W. Experimental study of stress relaxation in the process of cold molding with straw. BioResources 2009, 4, 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, W.; Han, L.; Xiao, W.; Liu, X. Effects of different pretreatments on compression molding of wheat straw and mechanism analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 251, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Ma, P.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Hui, Y.; You, Y.; Wang, D. A review of research progress in the compaction of major crop waste by mechanical equipment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 213, 115484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, L.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Qi, W.; Lei, T. Effects of Different Biomass Types on Pellet Qualities and Processing Energy Consumption. Agriculture 2025, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Tabil, L.G.; Sokhansanj, S. Effects of compressive force, particle size and moisture content on mechanical properties of biomass pellets from grasses. Biomass Bioenergy 2006, 30, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herak, D.; Kabutey, A.; Choteborsky, R.; Petru, M.; Sigalingging, R. Mathematical models describing the relaxation behaviour of Jatropha curcas L. bulk seeds under axial compression. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 131, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liao, N.; Xing, L.; Han, L. Description of Wheat Straw Relaxation Behavior Based on a Fractional-Order Constitutive Model. Agron. J. 2013, 105, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wang, C.; Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Jin, M.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Stress Relaxation Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Sweet Sorghum: Experimental Study. Bioresources 2018, 13, 8761–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Arnavat, M.; Shang, L.; Sárossy, Z.; Ahrenfeldt, J.; Henriksen, U.B. From a single pellet press to a bench scale pellet mill—Pelletizing six different biomass feedstocks. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 142, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, N.; García-Maraver, A.; Zamorano, M. Influence of densification parameters on quality properties of rice straw pellets. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 138, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Fang, X.; Li, L. Effect of different moisture contents on flow ability parameters of chopped rice straw. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2013, 44, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- McAfee, J.R.; Shinners, K.J.; Friede, J.F.; Walters, C.P. Creating high-density large square bales by recompression. Trans. ASABE 2019, 62, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasick, G.T.; Liu, J. Lab scale studies of miscanthus mechanical conditioning and bale compression. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 200, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lei, T.; Shen, S.; Zhang, Q. Specific Energy Consumption Regression and Process Parameters Optimization in Wet-Briquetting of Rice Straw at Normal Temperature. Bioresources 2013, 8, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, W.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y. Effects of Wet Soybean Dregs on Forming Relaxation Ratio, Maximum Compressive Force and Specific Energy Consumption of Corn Stover Pellets. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, G.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y. Experimental study on creep properties prediction of reed bales based on SVR and MLP. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Yu, Z. Creep Characteristics of Corn Straw Particles Simulated Based on Burgers Model. Bioresources 2024, 19, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Liang, S.; Zhang, L. Construction Method of Viscoelastic Constitutive Relation and Application Examples. Mech. Eng. Pract. 2022, 44, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, M.; Wang, M.; Cen, H.; Li, L.; Li, T.; Jing, W.; Li, J.; Wen, B. Experimental Study on Compression and Rheological Properties of Different Licorice Stem Varieties. J. Shihezi Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 41, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Rheology of Agricultural Materials; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 16–55. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.