Abstract

Romania faces a double challenge in the swine production sector. On one hand, the European Union’s environmental agenda demands that member states drastically reduce both the carbon footprint and the use of antibiotics in animal husbandry by 2030. On the other hand, the Romanian swine industry still grapples with long-standing internal issues such as excessive fragmentation, a strong dependence on imported piglets and feed materials, and a clear shortage of modern management experience. This study set out to explore how the ADKAR model can serve as a structured approach to help commercial swine farms in Romania transition toward sustainability. To gather relevant data, researchers distributed a five-point Likert-scale questionnaire to 83 farm managers, out of the 361 officially registered commercial swine farms. The instrument was designed to assess how each farm positioned itself across the five ADKAR dimensions. The results revealed that most Romanian farm managers are highly aware of the need for change and show a generally positive attitude toward adopting sustainable practices. However, there remain considerable knowledge gaps and practical limitations, which continue to act as major barriers to effective implementation. The composite ADKAR-S Index, which measures the “sustainability maturity” of each farm, displayed a strong positive correlation with economic performance, particularly the profit margin (r ≈ 0.45, p < 0.001), and a significant negative correlation with antimicrobial use (r ≈ −0.50, p < 0.001). Simply put, farms that are better prepared for organizational transformation tend to perform better financially while also reducing their environmental footprint. The findings suggest that policy efforts should prioritize human capital development, especially through training programs and reinforcement systems such as continuous monitoring and staff incentives, to ensure that sustainable practices are not only adopted but also maintained in the long run.

1. Introduction

The swine farming industry is now facing stronger sustainability challenges than ever before. Within the European Union, the Farm to Fork Strategy has introduced highly ambitious targets, aiming, for example, to halve the sales of antimicrobials used in livestock by 2030 [1]. At the same time, there are broader objectives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and achieve full climate neutrality by 2050 [2,3]. The livestock sector, and especially swine production, finds itself at the center of this transition, since pork continues to be the main type of meat both produced and eaten across the EU, with an average of about 32.5 kg consumed per person every year [4]. Even if swine production is not counted among the major sources of greenhouse gases within the livestock sector, it nonetheless adds a noticeable amount to the overall emissions profile. Most of this comes from methane and nitrous oxide, which are, more or less unavoidably, released during the processes of manure collection and storage. In response, European producers are under growing pressure to adopt practices that can shrink their environmental footprint [5]. Current strategies concentrate mainly on improving feeding systems by using more local and low-carbon feed ingredients, and on developing better manure management solutions such as covered storage lagoons or biogas units. These two directions have been repeatedly identified as some of the most effective ways to reduce emissions coming from swine farms [6].

The organizational landscape of Romania’s swine industry remains markedly fragmented, both with respect to the number of holdings and to how livestock is distributed across them. When examined at the level of individual farms, Romania records the highest incidence of very small-scale pig operations in the European Union; roughly 63% of all registered holdings maintain only a handful of animals, sometimes no more than two or three. Viewed from the standpoint of herd distribution, a substantial proportion of national pig stocks continues to be raised in units numbering fewer than ten head, whereas only a comparatively minor segment of the country’s total herd is kept in farms exceeding 400 animals. This constitutes, in fact, the lowest presence of large-scale production units among EU member states, a detail which is often overlooked in policy debates.

By contrast, member states such as Denmark or Germany exhibit a near-reversed structure: despite having far fewer individual farms, more than 90% of their pigs are concentrated within large, industrialized production systems. The divergence between these models is considerable and has implications, not always fully appreciated, for both competitiveness and the capacity to implement more advanced sustainability measures [7]. Such fragmentation leads to major differences in performance and know-how. A few vertically integrated companies operate alongside a vast number of small family farms, many of which have limited capital and little access to modern innovations. During the past twenty years, a mix of economic crises and animal health issues has further worsened the decline of domestic pork production. National herds fell by nearly 29% between 2007 and 2016, forcing the country to rely more and more on imported piglets, meat, and processed pork to cover local demand. In some years, as many as 20–30% of fattened piglets were brought from abroad [7].

This dependence on imports goes beyond live pigs, because it also includes critical inputs like premium genetic material and protein sources such as soybean meal, which are essential for compound feed. The reasons are quite complex. On one hand, Romanian farms have not managed to develop strong breeding programs or sufficient feed production capacity. On the other hand, the public policies and investments that could have supported these efforts have not always been well-targeted. For example, much of the European funding available in the 2014–2020 period for livestock development ended up being directed toward fattening farms instead of breeding operations, which only deepened the reliance on imported piglets and genetics [8].

An additional structural element that warrants careful consideration is the well-established principle of economies of scale, extensively reported in livestock sectors across Central and Eastern Europe. Larger and more vertically coordinated operations are typically able to spread fixed expenditures over higher output volumes, negotiate more advantageous prices for feed or veterinary services, and employ staff with a level of specialization that smaller family farms rarely can sustain. By contrast, very small holdings tend to incur persistently high production costs per unit and, consequently, exhibit lower margins of profitability, irrespective of how capable their management may be. This scale-related effect operates independently from managerial competence and must therefore be accounted for otherwise; comparisons of performance across different farm sizes risk leading to misleading interpretations [9].

All these factors create a landscape where most stakeholders agree that moving toward sustainability is necessary, but putting that transformation into practice remains a tough task. Changing a conventional farm into a sustainable one means more than just buying greener technology. It requires a deep shift in mentality and management culture, something that resembles turning a large ship in the opposite direction. It takes patience, coordination, and determined leadership.

The literature dedicated to agricultural innovation underlines that adopting sustainable practices is far from a purely technical or economic decision. It is, in fact, a deeply human and organizational process that depends on attitudes, perceptions, and even the social environment within which farmers operate. Research focused on behavioral change among farmers has shown that how individuals perceive environmental risks, their personal and external motivations, and the amount of information they have access to can all influence how successfully they apply new methods, such as reducing antibiotic use, improving biosecurity, or managing farm waste more efficiently [10,11].

In recent years, scholars have started paying growing attention to how theories from business change management could be adapted and applied to the farming context [12]. One of the most relevant frameworks in this respect is the ADKAR model, which includes five key components of change: Awareness, or recognizing that change is necessary; Desire, meaning the will to take part in that change; Knowledge, which refers to understanding the process itself; Ability, the practical capacity to carry it out; and Reinforcement, the effort to maintain the results over time [13]. Originally designed for corporate use, this model has gradually been extended beyond its initial boundaries and is now used to guide transformation processes in other fields as well.

Later studies have shown that the ADKAR model can also be effectively applied in medical and veterinary domains to analyze and encourage behavioral change, both at an individual and organizational level [14,15,16,17]. For example, Houben and colleagues (2020) used ADKAR to categorize farmers according to how willing they were to reduce antibiotic use in livestock [11]. Their research revealed that this approach can highlight which specific barriers stand in the way of safer practices, whether it is a lack of awareness about the problem or a weak motivational drive to change.

The findings from these studies suggest that the ADKAR framework can act as a genuinely useful tool for diagnosing challenges within the agricultural sector. It allows researchers and practitioners to see more clearly where along the path of change things start to go wrong. In some cases, farmers might simply not realize the necessity of change during the awareness phase, while others may hesitate to act because of financial pressures or long-standing cultural habits. There are also situations where the problem lies in a lack of technical training or weak managerial skills, which limit their ability to actually apply what they have learned. And even when new practices are introduced, many farms find it hard to keep them going in the long run, often because they do not have proper systems in place to reinforce or reward these behaviors over time.

Considering that there is still a small amount of knowledge about how swine farms in Romania are managing their internal transition toward more sustainable practices, this study aims to bring a fresh and original contribution by using the ADKAR model as a lens for analysis. The core aim of this study is to examine how far sustainability principles have been genuinely embedded in the everyday activities of swine farms and to assess the level of readiness these farms show when it comes to adopting change. The analysis follows the five key phases defined by the ADKAR model, each representing a step in the broader process of transformation, from the first moment of recognizing the need for change to the gradual and continuous reinforcement of sustainable practices over time.

- The study first aims to identify the internal factors that either slow down or encourage sustainable transformation within Romanian swine farms. This is performed by looking closely at how farm managers and technical staff perceive the need for change (Awareness), what motivates or discourages them from adopting sustainable practices (Desire), the level of knowledge and skills they currently possess in relation to environmentally friendly technologies (Knowledge and Ability), and finally, how well the implemented changes are maintained over time (Reinforcement).

- A second objective is to build a composite indicator called the ADKAR-Sustainability Index (ADKAR-S). This tool is meant to measure how “mature” a farm is in terms of organizational sustainability, based on the scores obtained across the five ADKAR dimensions. The index serves a dual purpose: on one hand, it can be used to compare farms at different stages of transformation, and on the other, it allows researchers to track how progress evolves as farms move toward more sustainable operations.

- Lastly, the study investigates the connection between the ADKAR stages and actual farm performance, by analyzing how readiness for change (as reflected by the ADKAR-S index and its individual components) relates to measurable outcomes, both economic, such as productivity and profitability, and environmental, like lower antibiotic consumption, improved manure management, or compliance with ecological standards. Through this analysis, the hypothesis being tested is that farms showing a higher level of readiness for sustainability tend to achieve stronger financial and environmental results.

Through these objectives, the present research draws attention to an aspect that has often been neglected in the broader attempts to make Romanian agriculture more sustainable, the human and organizational side of transformation. Rather than seeing farms simply as technical units that can become “greener” through financial investment and equipment upgrades, this study views them as living communities made up of people, where genuine change depends on leadership, organizational culture, and a deep understanding of how individuals think and react to transformation.

To ensure that the study is presented clearly and logically, while also allowing it to be replicated or used as a model for future research, the paper follows the IMRAD structure. This format was chosen to provide both scientific rigor and practical value for those working in the agricultural sector or involved in policy development. Accordingly, the following parts describe the methodology employed, the results obtained, the interpretation of these findings within a wider context, and finally, the key conclusions that can guide future practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

The research took place over six months, from January to June 2025, and included farms located in twenty counties across Romania, ensuring a wide geographical and structural diversity. Data collection involved direct collaboration with farm managers, who completed the standardized questionnaires either online or during on-site visits, depending on their accessibility and preference.

Once all responses had been gathered, the research team carefully reviewed each questionnaire to ensure that the answers were complete and coherent. Any unclear or missing responses were double-checked through follow-up communication with participants, helping to avoid inconsistencies that might have affected the results. After this stage, all data were anonymized to protect the identity of respondents and their farms, ensuring strict compliance with ethical research standards.

The finalized dataset then underwent a meticulous process of data cleaning and validation, aimed at removing possible entry errors and verifying logical consistency between variables. Statistical processing and analysis were performed during May and June 2025 using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26). This stage included the preparation of descriptive summaries, reliability testing, and the application of advanced analytical models, which together formed the empirical basis for the findings presented in this study.

By the end of 2024, official records indicated the existence of approximately 361 commercial swine farms across Romania, excluding the many small-scale subsistence households that raise pigs primarily for self-consumption. Out of this total, 83 farms, representing about 23% of the national number, agreed to take part in the study voluntarily. The participation rate is considered satisfactory for this type of research, as it provided both statistical reliability and regional diversity [18]. The farms included in the analysis were distributed across 20 different counties. In order to ensure the quality and relevance of the data, specific inclusion criteria were established before sampling. Only farms maintaining herds of at least 50 pigs and engaged in commercial activities, meaning production destined for sale on the market, were eligible for participation. This ensured that respondents held significant managerial or decision-making responsibilities and were directly involved in complying with the regulatory and biosecurity requirements imposed on commercial livestock operations.

Participation in the survey was fully voluntary and conducted under strict conditions of anonymity. Before completing the questionnaire, every manager provided informed consent, acknowledging their understanding of the study’s purpose and the confidentiality measures in place, because ethical integrity was a central concern throughout the research process. At the same time, all data collected throughout the study were handled in accordance with the ethical standards of research and the applicable European data protection regulations. In compliance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation (EU) 2016/679), all responses were stored securely on encrypted cloud-based servers (Google Drive), accessible only to the research team.

2.2. Questionnaire and Measured Variables

The empirical component of the study relied primarily on a structured questionnaire, elaborated in accordance with the internal logic of the ADKAR framework for organizational change. The instrument comprised 25 statements, grouped across the five ADKAR dimensions: Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement. This meant that each construct could be captured through a small but coherent set of indicators. Respondents evaluated every item using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), a format that made it possible to convert subjective perceptions into quantifiable data amenable to statistical analyses.

The development of the questionnaire was grounded in a broad review of scholarly contributions on sustainable agricultural practices [19,20,21,22], behavioral dynamics in farm management [10,23,24], and the theoretical underpinnings of organizational change processes [25,26,27]. Its eventual formulation was subsequently adjusted to the particularities of the Romanian swine sector, with special attention regarding issues that practitioners themselves identify as pressing biosecurity protocols, waste and manure handling, reduced reliance on antibiotics, and the training of on-farm personnel [28,29,30].

Awareness refers to the degree to which farm managers acknowledge the environmental and regulatory pressures shaping contemporary livestock production, including the implications of emissions, waste flows, and EU-level strategies. An illustrative item is: like “We are aware of the environmental impact our farm generates, such as emissions or waste, and we know that these must be reduced” or “We understand the requirements set by recent European policies, like the Farm to Fork Strategy, regarding the limitation of antibiotics and emissions.”, though a few respondents appeared to interpret this statement more narrowly than intended.

Desire captures motivational forces, the willingness of decision makers and staff to actually engage in sustainability-oriented change. Items in this category explore whether the actors involved feel personally committed to adopting greener practices despite short-term inconveniences or operational slow-downs; for instance: Our management is willing to dedicate time and resources to adopt more environmentally friendly practices” and “Our employees are motivated to test new methods that improve sustainability, even if this initially means extra effort”.

Knowledge concerns the extent of understanding regarding the technical and managerial requirements of sustainability transitions. This dimension encompasses familiarity with antibiotic-reducing strategies, updated feeding technologies, manure treatment options, and animal welfare standards. Items ask how much training respondents have received or, sometimes, how confident they feel about applying ecological practices.

Ability reflects the tangible capacity of farms to implement these practices in daily routines. It includes access to equipment, financial means, qualified staff, and adequate infrastructure.

Reinforcement addresses whether sustainability behaviors are sustained over time through monitoring routines, internal rules, incentive systems, or periodic audits. Representative items include statements such as: “We monitor environmental indicators such as energy and water use, emissions, and antibiotic consumption to track progress toward our goals,” or “We offer recognition and rewards to employees who actively follow and promote sustainable practices.” In a few cases, respondents left this item blank, which complicates the interpretation.

Together, these components provide a multidimensional depiction of organizational readiness for sustainability, even if respondents, at times, understood the distinctions between dimensions in slightly different ways than the model would strictly prefer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structure of the ADKAR questionnaire for assessing sustainability readiness in Romanian swine farms.

For each of the five ADKAR components, a composite score was determined by calculating the average value of the five individual items corresponding to that particular dimension. This procedure produced a score that could vary between 1 and 5 for each area of the model. The internal consistency of the items was verified using Cronbach’s alpha, which recorded values ranging from 0.70 to 0.85. These results confirmed that the items within each dimension were coherent and reliable, making it statistically sound to use their mean value as a single summary indicator for analysis.

Beyond the evaluation of individual components, an overall indicator was constructed to reflect the general level of sustainability readiness across the surveyed farms. This measure, named the ADKAR-Sustainability Index (ADKAR-S), was obtained through a simple arithmetic mean of the five component scores, Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement, divided by five. The resulting index, therefore, also ranged from 1 to 5, providing a global picture of each farm’s maturity level in its transition toward sustainable management (Table 2).

Table 2.

Calculation of ADKAR scores and the overall ADKAR-S index.

The interpretation of the five ADKAR dimensions provides a clear overview of how ready Romanian swine farms are for the transition toward sustainable practices. Scores, ranging from 1 to 5, reflect each farm’s stage of development in terms of awareness, motivation, knowledge, ability, and reinforcement of change.

A high Awareness score shows that managers and staff understand the farm’s environmental impact and the urgency of aligning with European sustainability goals, while low values reveal weak information and limited understanding. Desire measures the willingness to act; scores above 4 display strong motivation and openness to adopting eco-friendly practices, whereas lower scores indicate hesitation or resistance. Knowledge highlights how well managers and workers grasp sustainable technologies and regulations; high scores show strong competence, while low ones suggest a need for better training. Ability evaluates the farm’s capacity to apply that knowledge in practice. High-scoring farms possess adequate resources and skilled personnel, while low scores reveal financial or operational barriers. Finally, Reinforcement examines how change is maintained over time through monitoring systems, incentives, or management support, with high values indicating stable progress and low ones a risk of regression.

To summarize these findings, the ADKAR-S Index was calculated as the mean of the five dimensions. Scores between 4.01 and 5.00 denote a mature, sustainable organization; 3.01–4.00 an intermediate stage; 2.01–3.00 an early phase; and below 2.00 clear resistance to change. Overall, the index provides a concise picture of each farm’s sustainability maturity and helps identify the areas where targeted support or policy intervention is most needed. To prevent any confusion in how the concept is understood, it should be pointed out that the ADKAR-S Index does not actually tell us how sustainable a farm is at the moment. What the indicator captures, more precisely, is the farm’s organizational readiness and its (sometimes uneven) capacity to take up, apply, and then maintain environmentally responsible practices. Even though farms that already started to introduce sustainable measures tend in many cases to score higher, this shouldn’t be read as a measure of their present sustainability. The index refers mainly to potential and the degree of preparedness for change, not to the sustainability results that have been achieved already, which are another type of evaluation altogether.

2.3. Performance Indicators Measured

Besides the perception-based information obtained through the questionnaire, participants were also asked to share factual data about their farm’s recent performance. This allowed for a comparison between actual outcomes and the results derived from the ADKAR scores. Two key performance indicators were selected as the most relevant for this purpose and were consistently included in the analysis.

Economic performance was represented by the operating profit margin (expressed as a percentage) for the latest available fiscal year, 2022. This figure was either directly reported by the farm manager or, when not available, estimated using data on revenues and operating expenses. The choice of profit margin instead of total profit was intentional, as it provides a fair basis for comparing farms of different sizes and production capacities.

Environmental and health performance was assessed through the level of antimicrobial use, quantified as the number of Defined Daily Doses (DDD) of antibiotics administered per 100 animals annually. Farm managers provided information on the average number of antibiotic treatments administered each month, which was then extrapolated to estimate an annual DDD value. This indicator is particularly important, since reducing antibiotic use in livestock farming remains a central objective of sustainable agriculture. Lower antimicrobial use not only contributes to public health by minimizing antimicrobial resistance but also serves as a good reflection of animal welfare and biosecurity conditions within the farm.

It is important to note that self-reported data can carry certain limitations. Respondents may have estimated figures or lack precise records. To minimize bias, all participants were reassured about the confidentiality of their responses and encouraged to report information as accurately and truthfully as possible.

Additionally, around 40 farms, roughly half of the total sample, also provided complementary performance data, such as feed conversion ratios, mortality rates, and estimates of ammonia emissions. However, these additional indicators were too inconsistently reported to allow meaningful statistical testing. As a result, the analysis focused exclusively on the two indicators that were available for all farms, ensuring a consistent and reliable comparison (Table 3).

Table 3.

Objective farm performance indicators used for correlation with ADKAR dimensions.

All performance indicators collected from the participating farms were statistically correlated with the overall ADKAR-S Index, as well as with each of its five individual components, to explore possible connections between organizational readiness for change and actual sustainability outcomes. The operating profit margin was used to represent short-term financial efficiency, offering a direct measure of how effectively each farm managed its production and resources. Meanwhile, the intensity of antimicrobial use acted as a central environmental and animal health indicator, reflecting progress toward responsible farming practices and biosecurity improvement.

Although the data relied partly on self-reported figures, strict confidentiality and full respondent anonymity were guaranteed throughout the process. These measures encouraged open and sincere participation, helping to minimize potential reporting bias and strengthen the credibility and reliability of the findings.

2.4. Data Analysis

The collected questionnaire data were processed and analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 26. As a first step, an exploratory analysis was carried out to check data quality and completeness. The dataset showed no major missing responses, and in a few isolated cases where an item had not been answered, the mean substitution method was applied to replace the missing value. This ensured the integrity of the dataset and allowed for consistent statistical processing.

Next, the internal reliability of each ADKAR subscale was assessed. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.70 to 0.85 across the five dimensions, indicating that the internal consistency of the scales was satisfactory and that the items within each dimension measured the same underlying construct. To further confirm the structure of the instrument, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed using varimax rotation on all 25 items. The purpose was to verify whether the items naturally clustered into the five theoretical categories: Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index had a value of 0.79, suggesting good sampling adequacy, while Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), which indicated that the correlation matrix was appropriate for factor analysis. The EFA results revealed five distinct factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining approximately 68% of the total variance. The pattern of loadings corresponded closely to the theoretical structure of the ADKAR framework. Most items loaded strongly (above 0.6) on their intended factor, and only one item showed a modest secondary loading, which did not alter the overall interpretation.

Taken together, these findings confirmed that the questionnaire items were well-aligned with the theoretical model. The factor structure and reliability coefficients provided solid evidence of construct validity, meaning that the scales successfully captured the intended dimensions of the ADKAR model within the context of Romanian swine farms.

To meet the research objectives, the data analysis was conducted step by step, following a structured but practical approach that allowed both descriptive and inferential interpretation of results.

Descriptive statistics. In the first stage, the mean values, standard deviations, and score distributions were calculated for each ADKAR dimension, as well as for the overall ADKAR-S Index. Additionally, the percentage of respondents whose average score fell below certain cut-off points (for example, ≤3) was determined to pinpoint which specific aspects of change readiness showed the largest weaknesses or gaps across farms.

Group comparisons. The next stage involved examining whether the ADKAR scores differed significantly across categories of farms. To do this, independent-sample t-tests and one-way ANOVA were used. Farms were classified according to several criteria: herd size (small < 100 head, medium 100–400 head, large > 400 head), ownership type (family-run versus investor-owned), and geographical region. This approach aimed to reveal possible patterns, such as whether larger, more professionalized farms tended to perform better in Knowledge and Ability due to greater access to resources, trained staff, or technological innovation.

Correlations among variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was used to explore linear associations between the ADKAR dimensions (both individually and combined) and the two main performance indicators, profit margin and antibiotic usage intensity. In addition, correlations among the ADKAR components themselves were examined. For example, the analysis tested whether Awareness was strongly associated with Desire, suggesting that a high understanding of sustainability issues tends to generate motivation, or whether Knowledge correlated with Ability, implying that farms with stronger know-how are also more capable of applying it in practice.

Multiple regression analysis. To investigate the potential predictive relationships more deeply, two multiple linear regression models were developed. In the first, profit margin was the dependent variable, while the five ADKAR dimensions were used as predictors, with farm size included as a control variable. The goal was to determine which specific components of change readiness had the strongest influence on financial performance. In the second model, antimicrobial use (log-transformed for normalization) served as the dependent variable, again with the ADKAR dimensions as predictors and farm size controlled.

A stepwise regression method was employed to retain only the most relevant predictors, given the relatively modest sample size (n = 83), which represents a ratio of roughly 1:16 between the sample size and the total number of variables, adequate, though close to the lower recommended limit. As a precaution, results were interpreted conservatively to avoid overfitting or inflated significance. The standard significance threshold was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), while stronger effects were reported at p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 when applicable.

3. Results

3.1. General ADKAR Profile of the Studied Farms

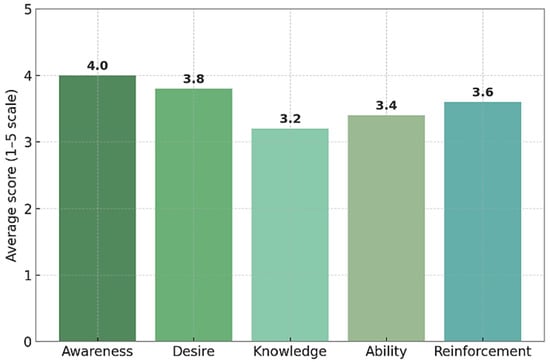

The descriptive analysis showed that there were clear variations between the different components of the ADKAR model across the surveyed farms. Among these, Awareness, the understanding of the need for change, recorded the highest average values, reaching roughly 4.0 ± 0.5 on a scale from 1 to 5. This suggests that most farm managers are well informed about the importance of sustainability and understand both the regulatory and market pressures that increasingly require farms to adopt more responsible production methods. Only a small share of respondents, around 15%, scored 3 or lower, reflecting limited understanding or a weaker perception of the urgency for change.

The Desire dimension also showed encouraging results, with an overall average of about 3.8 ± 0.6, indicating that most participants expressed genuine motivation to adopt sustainable measures. Their willingness appeared to be driven by several factors: personal beliefs, expectations of long-term benefits such as cost savings or improved competitiveness, and, in some cases, compliance with new legal or market standards. Nevertheless, a small group, approximately one-fifth of the sample, showed hesitation or low enthusiasm toward change. This variability in attitudes might be linked to factors such as differences in age, education level, or the farm’s financial situation, which often shape how open managers are to innovation and sustainability transitions.

In contrast with the high levels recorded for awareness and desire, the results for the components linked to knowledge and ability were notably lower. The Knowledge dimension registered the weakest average score, around 3.2 ± 0.7, pointing to significant gaps in both technical understanding and managerial competence when it comes to sustainable farming practices. Nearly half of the respondents (approximately 45%) scored 3 or below in this category, which clearly indicates that a large share of farms still face serious informational and educational barriers that hinder their progress toward sustainability.

The Ability component, which reflects how well farms can translate knowledge into actual practice, showed only a slightly better result, with an average of 3.4 ± 0.6 and roughly 40% of farms scoring below 3. These findings suggest that many farms struggle not only with limited knowledge but also with practical constraints such as a lack of investment capital, insufficiently trained workers, or outdated infrastructure. In other words, even where the motivation to change exists, the capacity to act effectively often remains limited by external and operational factors.

The Reinforcement dimension displayed a more moderate pattern, with an average score of 3.6 ± 0.5. Only about 30% of farms fell below the threshold of 3, suggesting that a growing number of farms have already started developing internal systems to maintain newly adopted practices. These include measures like monitoring resource use, enforcing internal procedures, or introducing performance incentives. Still, ensuring that these improvements persist over the long term remains a common challenge for most operations.

Figure 1 graphically presents the differences between the average scores of the ADKAR dimensions, making evident the strong contrast between the relatively high awareness and desire levels on one side and the much weaker knowledge and ability components on the other.

Figure 1.

Average ADKAR component score.

The results of the principal component analysis (PCA) carried out on the questionnaire data confirmed that the items grouped themselves according to the five theoretical dimensions proposed by the ADKAR framework. This outcome demonstrates that the structure of the model remained stable and logically consistent when applied to the specific context of Romanian swine farms. The result is important because it supports the validity of using the composite ADKAR-S Index as a reliable indicator of organizational readiness for sustainable change.

When calculated individually for each farm, the ADKAR-S Index values ranged from a minimum of 2.5 to a maximum of 4.6 on a 1-to-5 scale. The average score was 3.60, with a standard deviation of 0.52, suggesting moderate variability among farms. The data distribution followed an approximately normal pattern, as indicated by the Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 0.18), but with a slight negative skew (skewness = −0.45). In practical terms, this means that a larger number of farms scored toward the upper end of the scale, showing a generally good level of preparedness for sustainability-oriented change rather than falling into the lower, less-prepared category.

Despite these encouraging results, only a small fraction of farms could be truly described as leaders in sustainability. Specifically, five farms, representing about 6% of the total sample, achieved ADKAR-S values higher than 4.3, which reflects consistently strong performance across all five dimensions of change. At the other end of the spectrum, seven farms (roughly 8%) scored below 3.0, indicating major weaknesses in several areas, especially in knowledge, practical ability, and reinforcement mechanisms. These findings suggest that, while most farms are on the right path, there is still a noticeable gap between the top performers and those struggling to implement sustainable management practices effectively.

3.2. Differences Between Farm Categories

The analysis explored whether the ADKAR scores varied systematically based on farm size and ownership structure. The ANOVA results revealed that size was indeed an important differentiating factor, with statistically significant differences across several of the ADKAR dimensions. For example, large farms (over 400 head) obtained noticeably higher mean scores for the Knowledge component, averaging around 3.8, compared to small farms (less than 100 head, mean ≈ 3.0, p < 0.01) and medium-sized farms (100–400 head, mean ≈ 3.3, p < 0.05). A similar pattern appeared for Ability, where larger farms also performed better, reaching an average of about 3.9, compared to roughly 3.1 for smaller holdings (p < 0.01).

These disparities align with the broader economic logic observed in livestock systems, where advantages associated with economies of scale are repeatedly documented. In most cases, larger production units are able to operate with significantly lower costs per unit and, as a consequence, tend to obtain more favorable economic results, irrespective of the particular managerial style or preferences employed on the farm.

These findings indicate that both farm size and the degree of professionalization seem to play a key role in shaping a farm’s readiness for change. Larger farms are often better organized, more capitalized, and sometimes vertically integrated usually benefit from trained personnel such as veterinarians, livestock engineers, and farm managers. They also tend to have access to specialized consulting services, training programs, and the financial resources needed to modernize infrastructure and adopt advanced technologies. Such advantages explain their stronger performance in Knowledge and Ability.

By contrast, smaller farms, which are typically family-run operations, face considerable limitations. They rarely have the same level of access to formal training, financial instruments, or professional guidance, and instead rely heavily on accumulated practical experience or advice from informal local networks. Despite these structural challenges, interestingly, no major differences were found between farm sizes when it came to Awareness and Desire (mean values roughly between 3.8 and 4.0; p > 0.1). This means that smaller farms are just as aware of sustainability challenges and equally motivated to improve, even if their resources are much more limited. The barriers for them appear later in the process, when knowledge, skills, or capital are required to move from intention to action.

For the Reinforcement dimension, large farms again displayed slightly higher average values (around 3.8) compared to small ones (about 3.4), although the difference was only marginally significant (p = 0.08). This still suggests a meaningful tendency: bigger farms are generally more capable of establishing systems that monitor performance, maintain consistency, and formalize change. These farms are more likely to have internal departments or designated personnel responsible for environmental compliance or quality assurance, structures that are typically absent in small holdings, where the owner or manager usually handles everything personally (Table 4).

Table 4.

Differences in ADKAR component scores by farm size category.

Farm size appeared to have a strong effect on the Knowledge and Ability dimensions, with larger and more professionalized farms scoring noticeably higher than small or medium-sized ones. This difference likely reflects the structural benefits that come with scale; larger farms usually have access to specialized staff, regular training opportunities, and more stable financial resources. These advantages naturally translate into greater technical competence and a stronger capacity to implement new sustainable practices.

On the other hand, Awareness and Desire remained high across all farm categories, suggesting that the motivation to adopt environmentally responsible practices is widespread, even among smaller, family-operated holdings. Managers of small farms appear just as conscious of sustainability challenges and equally committed to making improvements, despite facing more limited means to do so.

For the Reinforcement component, the trend was more modest. Larger farms tended to have slightly higher scores, reflecting their ability to introduce more formalized monitoring and auditing systems. However, this advantage was not particularly strong, implying that while big farms may be better organized, the consolidation of sustainable practices still depends on continuous effort, regardless of size.

3.3. The Type of Ownership

Within Romania’s swine industry, the term vertical integration usually describes those corporate or investor-owned systems where several stages of the production chain—breeding, fattening, feed manufacture, veterinary services, and sometimes even slaughter or basic processing- are organized under the same managerial umbrella. This type of structure stands in quite a sharp contrast with the smaller, family-type farms, which most of the time handle only the fattening phase and must depend on outside suppliers for piglets, feed, and, not rarely, for technical or veterinary support.

The analysis of ownership type, comparing independent farms with those belonging to corporate groups or foreign investors, revealed no major differences across most of the ADKAR dimensions. Although farms operating within company networks or supported by external investment tended to record slightly higher averages for Knowledge and Ability, these variations were minor and did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that while corporate farms may benefit from more structured management systems and better access to training or modern technologies, these advantages are not yet strong enough to create a meaningful gap in overall change readiness compared with independent producers.

Likewise, geographical location did not appear to significantly affect ADKAR scores. The only observable trend was a mild tendency for farms in western Romania, particularly those situated in the Banat and Crișana regions, to report slightly higher values for Awareness and Desire. One possible explanation is that these farms operate closer to Western European markets, where sustainability requirements and consumer expectations are generally higher, and this proximity may influence managerial attitudes and exposure to best practices. However, this observation should be interpreted with caution, as the number of respondents per region was relatively small and not evenly distributed across the country (Table 5).

Table 5.

Differences in ADKAR component scores by ownership type and geographical region.

The ownership structure of the farms seemed to have only a minor impact on their ADKAR results. Farms owned by corporations or foreign investors showed slightly higher average scores for Knowledge and Ability, yet these differences were small and not statistically significant, which means that the overall level of readiness for change was largely comparable across ownership types. In general, both independent and company-managed farms appear to share a similar understanding of sustainability and a comparable willingness to adapt.

The dimensions of Awareness and Desire were consistently strong regardless of who owned the farm or where it was located. A modest upward trend was observed among farms in western Romania, which could be explained by their greater exposure to European Union sustainability policies and by closer contact with Western-style agricultural systems. However, this tendency should be interpreted with some caution, given the limited number of farms per region.

Taken together, the findings suggest that both independent holdings and corporate farms demonstrate a comparable commitment to the transition toward sustainable practices. The slight advantages found in larger or Western-region farms likely reflect differences in access to resources, training, and proximity to more competitive and sustainability-driven markets rather than any fundamental difference in motivation or attitude.

3.4. Correlation Between ADKAR and Performance

One of the most important findings of this research is the clear link between how ready farms are to change, as reflected by their ADKAR scores, and their overall economic and environmental performance. The Pearson correlation analysis, summarized in the following table, revealed a statistically significant positive relationship between the ADKAR-S Index and the operating profit margin (r = +0.45, p < 0.001). In simpler terms, farms that show higher readiness for sustainable transformation also tend to perform better financially. Although some producers may still believe that adopting sustainable practices increases costs and reduces competitiveness, the results here suggest quite the opposite. The data point toward a reinforcing effect, where farms that focus on reducing waste, improving energy use, and strengthening animal health management often succeed in lowering long-term expenses and boosting productivity. Over time, these improvements translate into higher profit margins, demonstrating that economic efficiency and sustainability can, in fact, go hand in hand (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation between ADKAR dimensions and farm performance indicators.

The findings point to a strong and consistent link between how prepared farms are for organizational change and their overall profitability. The ADKAR-S Index (r = +0.45, p < 0.001) displayed the most pronounced correlation, indicating that farms that actively engage in sustainability, by building awareness, expanding knowledge, and improving their ability to act, tend to achieve both environmental and financial gains. In practice, these farms not only manage to lower ecological risks but also translate their efforts into better economic performance, showing that responsible management and profitability can successfully coexist.

3.5. Antimicrobial Use

The analysis revealed a strong negative relationship between antimicrobial use (expressed as DDD per 100 animals) and the ADKAR-S Index (r = −0.50, p < 0.001). Simply put, farms that scored higher in overall readiness for change tended to use significantly fewer antibiotics. This finding reinforces the idea that effective internal change management contributes directly to healthier herds and more environmentally responsible farming practices. This relationship likely stems from the fact that farms with a higher level of organizational maturity have already begun to adopt alternative disease-prevention strategies, including vaccination programs, improved hygiene and biosecurity procedures, and more balanced feeding systems. Such preventive approaches naturally reduce dependence on antibiotic treatments and align with broader sustainability goals. Table 2 illustrates these correlations numerically, both showing strong statistical significance (p < 0.01). Among the individual ADKAR dimensions, Knowledge and Ability displayed the most pronounced associations with reduced antibiotic use (both around r ≈ −0.48, p < 0.001), suggesting that technical competence and practical capacity are the key factors driving behavioral change in this area. On the other hand, Desire and Reinforcement showed the strongest links with profitability (approximately r ≈ +0.40 and r ≈ +0.38, respectively, p < 0.01), indicating that motivation and ongoing support systems are essential for maintaining efficient and profitable operations. While Awareness remains a critical foundation for any sustainability initiative, it did not exhibit an equally strong direct correlation with measurable performance indicators. This is understandable: awareness alone, though necessary, is not enough to produce tangible outcomes. Most farm managers were already aware of sustainability challenges, but what truly distinguished the higher-performing farms was their ability to translate that awareness into concrete actions, reflected in the other ADKAR components (Table 7).

Table 7.

Correlations between ADKAR components, profitability, and antimicrobial use.

The results clearly show a twofold impact of how ready farms are to manage change. On the economic side, farms that display stronger organizational readiness tend to achieve higher profit margins, while on the environmental side, they also manage to cut down on antibiotic use. The most pronounced relationship was a strong negative correlation (r = −0.50, p < 0.001) between the ADKAR-S Index and antimicrobial consumption, confirming that farms committed to sustainability are not only improving their own productivity but also contributing to broader goals of animal and public health protection.

Looking more closely at the individual elements of the ADKAR model, the dimensions of Knowledge and Ability showed the most substantial influence on reducing antibiotic dependence. This finding suggests that real progress toward sustainable livestock production depends less on good intentions and more on the presence of solid technical understanding and the practical ability to apply it. In short, knowing what to do and having the means to do it effectively make the biggest difference in limiting antimicrobial use and moving the sector toward healthier, more responsible production systems.

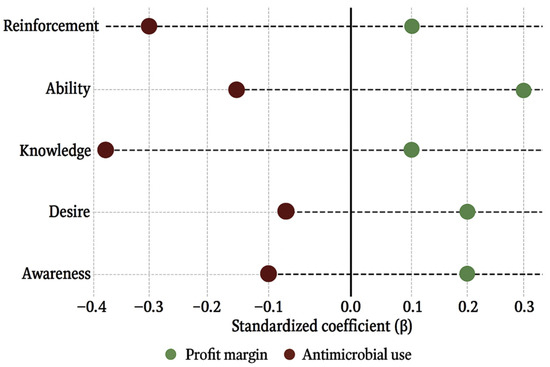

To explore these relationships in more depth, a series of multiple regression analyses was performed to identify which specific factors within the ADKAR framework had the strongest impact on farm performance. The regression model for profitability (adjusted R2 = 0.28, p < 0.001) highlighted two significant predictors: Ability (standardized coefficient β = +0.30, p = 0.005) and Desire (β = +0.22, p = 0.03). None of the other components reached statistical significance at the conventional 0.05 threshold. Interestingly, farm size, which was included as a control variable, did not show any meaningful effect. This pattern indicates that the farms’ practical capacity to apply changes and the internal motivation of their managers together explain a notable share of the differences in profitability across the sample. From a practical standpoint, this result makes intuitive sense. Having awareness or theoretical knowledge is not enough to generate profit on its own. What truly matters is the ability to turn that understanding into concrete actions and the determination to take those first, often difficult, steps toward change. Farms that combine competence with motivation are simply more efficient and adaptable, which translates into stronger financial outcomes. The regression model for antibiotic use provided even clearer insights, explaining a larger portion of variance (adjusted R2 = 0.42, p < 0.001). The two factors that showed the strongest and most statistically significant effects in reducing antimicrobial dependence were Knowledge (β = −0.38, p = 0.001) and Reinforcement (β = −0.29, p = 0.008). The negative direction of these coefficients means that higher scores in these areas correspond to lower antibiotic usage across farms. This finding aligns perfectly with expectations. Farms that possess solid technical knowledge, particularly about preventive medicine, vaccination programs, and alternative treatments, and that maintain consistent oversight through reinforcement mechanisms, such as routine veterinary reviews or strict hygiene and biosecurity controls, are precisely the ones that manage to reduce antibiotic reliance in practice. In other words, both know-how and consistent follow-up appear essential for transforming good intentions into measurable health and environmental improvements (Table 8).

Table 8.

Multiple regression results for farm performance indicators.

Figure 2 provides a visual summary of the standardized regression coefficients (β) estimated for each of the ADKAR components across the two performance models. In the figure, the green markers correspond to the predictors associated with profit margin, while the red markers represent the factors that influence antimicrobial use. The horizontal placement of each marker shows both the direction and the intensity of its effect.

Figure 2.

Scatter representation of ADKAR effects on farm performance.

As can be seen, Ability and Desire stand out as the strongest positive contributors to profitability, suggesting that farms with motivated management and solid implementation capacity tend to perform better financially. On the other hand, Knowledge and Reinforcement emerge as the key elements negatively associated with antibiotic consumption, highlighting their essential role in guiding farms toward healthier and more sustainable production systems. In short, farms that combine competence, motivation, and consistent monitoring practices not only achieve better economic outcomes but also demonstrate a real commitment to reducing their environmental and public health footprint.

In conclusion, the quantitative findings strongly confirm the study’s main assumptions. The data clearly reveal a consistent difference between how aware and motivated farm managers are and how much actual knowledge and capacity they possess to put sustainable practices into effect. This imbalance is visible in the many difficulties that farms face when trying to turn sustainability goals into concrete actions.

Still, in those farms where this gap has been successfully reduced, particularly the ones with higher scores in Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement, the positive effects are easy to observe. These farms tend to perform better not only economically, through higher profit margins, but also environmentally, by relying less on antibiotics and applying more responsible production methods.

4. Discussion

4.1. The ADKAR Profile of Romanian Swine Farms in Comparison with the International Context

This study represents the first attempt to quantitatively evaluate how prepared Romanian swine farms are to transition toward sustainability, using a structured and evidence-based analytical model. The results show that awareness of environmental and regulatory issues is already quite high, and that most farm managers display an overall positive mindset toward change. This is a noteworthy and encouraging result, suggesting that information campaigns and policy messages about the environmental consequences of livestock production, as well as the European Union’s ambitious goals, such as the 50% reduction in antibiotic use by 2030, have reached the farming community effectively [1].

Equally important, the relatively high scores recorded for Desire reflect the presence of genuine motivation at the micro level. Many Romanian farmers appear willing to take part in the shift toward sustainability, perceiving it less as a bureaucratic obligation and more as an opportunity to improve their farms and secure long-term competitiveness. This shows a change in mentality: sustainability is no longer viewed as an external pressure, but increasingly as an essential part of responsible farm management.

When compared with similar studies from Western Europe, these results show interesting differences. For example, Houben and colleagues (2020) found that in Belgium and the Netherlands, nearly 57% of surveyed farmers reported perceptual or motivational barriers to reducing antibiotic use [11]. In contrast, the proportion of Romanian farmers with low Desire scores was around 20%, suggesting that active resistance to change is far less common. This finding could indicate that Romanian producers, despite more limited resources, are more willing to comply with emerging sustainability norms.

A possible explanation for this pattern lies in the growing awareness that regulatory changes are inevitable, leading some farmers to prefer early adaptation rather than late compliance. In addition, the influence of large integrated companies that have already implemented higher sustainability standards appears to play an important role. By setting an example through improved management and transparency, these corporate actors may indirectly encourage smaller farms to follow the same path, fostering a gradual but steady cultural shift toward more sustainable farming practices.

By contrast, the lack of technical knowledge and practical skills identified in this study remains a major obstacle to achieving sustainability in Romanian swine farming. These deficiencies seem to represent the main bottleneck in the transition process. Comparable findings were reported by Houben et al. (2020), who observed that around 70% of farmers had insufficient knowledge and roughly 52% lacked the hands-on abilities required to effectively reduce antibiotic use [11]. These figures are very similar to those recorded in our own sample, where about 45% of respondents scored low for Knowledge and 40% for Ability.

The recurring message across contexts is clear: most farmers understand why change is needed and genuinely want to take part in it, yet they often lack the know-how and management capacity to put that desire into practice. This situation is not unique to Romania but reflects a broader pattern across European livestock systems. However, in Romania’s case, the challenge is likely amplified by financial limitations, restricted access to investment funds, and insufficient support for modernization, which further constrain the ability to act on sustainability intentions.

These findings strongly underline that improving knowledge transfer mechanisms and providing more hands-on, practice-oriented training should be top priorities for both policymakers and industry stakeholders. Without this bridge between motivation and implementation, the transition to sustainable livestock farming will remain uneven and slower than expected.

4.2. Barriers and Facilitators of Change

We consider mandatory the understanding of the existing gap between motivation and effective implementation, and how it might be reduced, and one of the most important explanations lies in the structural composition of the swine farming sector. Romanian swine production is still highly fragmented, with a large number of small, family-operated farms. This fragmentation slows down the spread of innovation and reduces the overall efficiency of knowledge transfer. Small farms typically lack access to specialized consultancy, technical assistance, or adequate financial support, which makes it difficult for them to adopt new technologies, such as advanced manure management systems, or to introduce more rigorous procedures like biosecurity and welfare protocols.

For example, a small 50-sow farm run by an older farmer often finds it challenging to interpret complex European regulations or to apply modern technologies on its own. In contrast, large, integrated farms, which in Romania represent only about one-third of the national herd (compared with roughly 90% in Western Europe) [7], recorded much higher Knowledge and Ability scores in this study. These farms benefit from economies of scale, allowing them to employ specialized professionals, invest in training, and access European funding with far fewer administrative or financial barriers.

In short, farm size appears to act as a facilitator of change, while very small-scale production functions as a constraint. This structural imbalance must be acknowledged in the design of agricultural policies. Training and extension programs should focus primarily on smallholders, ideally by promoting associative models that can encourage information sharing, reduce isolation, and improve collective access to resources. Strengthening such networks could help bridge the capability gap between small and large producers, making the transition toward sustainable swine farming both more inclusive and more effective.

Another important barrier that emerges from the data is the strong dependence of Romanian farms on imports and the insufficient development of local infrastructure for several key production stages. As mentioned earlier, Romania continues to import large volumes of piglets for fattening as well as genetic material from abroad [8], which shows that the breeding sector of the national swine industry remains poorly structured and underdeveloped.

This situation is not just an economic challenge but also one rooted in limited technical knowledge and experience. Modern breeding management, including artificial insemination, genetic selection, and strict health monitoring within breeding nuclei, requires specialized expertise that has been slow to develop domestically. Over the past decades, only a small number of Romanian farmers have had access to the kind of training or resources needed to manage these processes effectively.

As a result, many farms remain caught in a self-perpetuating cycle: without the knowledge or resources to improve their own breeding capacity, they are forced to keep purchasing piglets from foreign suppliers. However, this dependence itself prevents them from building the technical know-how needed to become self-sufficient. In effect, the more they rely on imports, the less they invest in developing internal expertise, which reinforces their long-term technological and economic dependency.

Viewed through the lens of the ADKAR model, this problem becomes even clearer. The low values recorded for Knowledge and Ability reflect precisely the inability of many farms to overcome such structural traps. Without improving these dimensions by building competencies, fostering innovation, and investing in breeding capacity, Romanian swine farms will struggle to achieve true sustainability and operational independence.

4.3. The ADKAR Role in Facilitating ESG Implementation

A key conceptual issue highlighted by this study concerns how ESG principles—Environmental, Social, and Governance—can be effectively translated into daily practice at the farm level [31,32]. While ESG provides a broad, strategic framework at the policy or corporate scale [33], its true implementation within agriculture depends heavily on people, habits, and internal management systems [34,35]. In this regard, the ADKAR model proves particularly valuable because it directly mirrors and complements the structure of the three ESG pillars.

The Awareness dimension connects most strongly to the Environmental pillar, since it reflects how conscious farmers are of the ecological footprint of their operations. At the same time, it also extends into the Social domain, as awareness includes understanding the farm’s impact on local communities, like odor management, water pollution risks, or the welfare of workers and animals.

The Desire component bridges both Social and Governance aspects. The motivation to change can emerge from public expectations and community pressures (S) or from the influence of regulations and incentives that fall under Governance (G). For instance, the willingness to comply with environmental standards or to seek voluntary certifications demonstrates both internal governance maturity and concern for social reputation.

Knowledge and Ability relate closely to Governance, as they depend on structured management practices that support training, partnership development, and investment planning. Yet they also have a clear Social component, reflecting the strength of human capital and the openness of organizational culture. A farm’s ability to evolve ultimately depends on its people and how well management can harness their skills.

Finally, Reinforcement aligns almost entirely with the Governance pillar. It involves the creation of policies, transparent monitoring systems, periodic evaluations, and reporting practices that help sustain change over time. In the farms analyzed, the relatively low Reinforcement scores reveal an area of concern: many lack proper monitoring mechanisms for tracking ESG performance. Some managers, for example, admitted, “We haven’t checked our exact energy use in years; we just know the bills keep going up,” illustrating how weak data systems can undermine long-term sustainability goals.

In this context, the ADKAR model can serve as a roadmap for embedding ESG principles within farm operations. First comes Awareness, understanding why ESG matters. Then Desire, which builds motivation by showing the benefits of ESG adoption. The next steps are Knowledge and Ability, which require training and hands-on guidance on eco-practices, animal welfare, or community engagement. Finally, Reinforcement ensures that these changes are institutionalized through stable policies and continuous evaluation.

The results of this study confirm that farms moving in this direction, those with higher ADKAR-S scores, are already showing measurable benefits: reduced indirect emissions, better resource efficiency, and steady or even improved profitability. This balance between environmental responsibility and economic viability is essential, as sustainable transformation can only endure if it remains financially realistic for farmers in the long term (Table 9).

Table 9.

Conceptual alignment between ADKAR dimensions and ESG pillars in sustainable farm management.

This conceptual framework illustrates how the ADKAR model can turn the broad ideas of ESG into practical, measurable actions at the farm level. Each of its components plays a role in weaving sustainability into the everyday functioning of an agricultural business, from raising awareness about environmental and social impacts to strengthening governance practices that ensure these improvements last over time.

Farms that achieve higher ADKAR-S scores tend to show stronger alignment with ESG goals in practice. They usually operate with greater efficiency, record lower emissions, and maintain steady or even improved profitability. This combination of outcomes demonstrates that environmental responsibility does not have to come at the expense of economic success; rather, both can evolve side by side when change is consciously managed and reinforced at every level of the organization.

4.4. Original Contributions of the Study

On the academic side, it represents the first large-scale application of the ADKAR model in the field of sustainable agriculture in Romania, showing that the framework is not only conceptually adaptable but also operationally effective in this context. The study developed a clear methodological approach built around an ADKAR-based questionnaire tailored for livestock production and the construction of an ADKAR-S Index, which can be replicated or modified for use in other agricultural sectors or even in neighboring countries facing similar challenges.

The findings demonstrate that although the ADKAR model was originally designed for use in corporate environments, it can successfully capture the complex dynamics of agricultural systems. It translates both farmers’ perceptions and behavioral patterns into measurable insights, while also linking them with hard performance data such as profitability and antibiotic reduction. This adaptability confirms the model’s scientific robustness and its capacity to bridge the gap between human factors and measurable sustainability outcomes.

Another significant contribution lies in uncovering direct correlations between organizational readiness for change and farm performance, reinforcing the idea that sustainability is not achieved by technology alone. While much of the literature on agricultural sustainability continues to emphasize innovations in equipment, feed, or genetics, the human and organizational side of transformation, training, leadership, and communication often remains overlooked.

By providing empirical evidence that these so-called “soft factors” can have just as much impact as financial investments, this study helps reposition people and organizational culture at the heart of sustainable transformation. In doing so, it encourages a more holistic view of sustainability, one that values human competence, management vision, and social cohesion alongside technical progress.

From a practical perspective, the findings of this research can provide valuable guidance for policymakers and for those responsible for shaping future rural development programs. One of the clearest messages emerging from the data is that the main barriers to sustainable transformation lie not in technology itself but in the lack of knowledge and skills. This suggests that public policy should shift focus toward strengthening agricultural advisory services, lifelong learning, and professional consultancy, rather than relying mainly on financial incentives. However, any recommendations drawn from these findings should be approached with caution; otherwise, the interpretation risks becoming a bit too linear. The study’s results indicate that larger and more integrated farms usually obtain higher scores on the Knowledge and Ability dimensions, which suggests they are in a stronger position to take up sustainability practices. Although this pattern might tempt us to conclude that scale and integration somehow guarantee a smoother pathway toward change, such a reading would be an overstatement. If policies lean too heavily in favor of big operators, they may push small and family-run farms further to the margins, narrowing the economic diversity of rural areas and, in some cases, concentrating too much influence in the hands of vertically integrated companies. Those dynamics can erode rural resilience, reduce competition, and weaken agriculture that is anchored in local communities, which is not the direction anyone wants.

This is why measures designed to strengthen sustainability must strike a more delicate balance: supporting professionalized and integrated farms where it makes sense, but also offering targeted help for the independent small and medium ones. Otherwise, gains in environmental performance might come at the cost of local autonomy or the longer-term viability of the mixed production models that many rural regions still rely on.

While capital subsidies remain useful, they are not enough on their own. Future development programs could include intensive training schemes on sustainable farming techniques, tied to measurable outcomes. For instance, a system of “consultancy vouchers” could be introduced, allowing farmers to access specialized advice to evaluate and improve their management practices, technical processes, or biosecurity systems. Such measures would help bridge the persistent gap between willingness to change and the capacity to act effectively.

The ADKAR-S Index developed in this study also has potential practical applications beyond research. It could serve as an evaluation tool for certification authorities, funding agencies, or financial institutions. For example, a bank offering “green” loans to farms could use a simplified ADKAR assessment to determine whether a farm has the organizational maturity and human resources needed to successfully implement the sustainability project it seeks funding for. After all, investing in a biogas facility or renewable energy system has limited value if the farm lacks the trained personnel to operate it efficiently.

Equally important, the study quantifies the positive connection between sustainability and profitability, offering strong, evidence-based arguments to counter the persistent notion that environmental responsibility comes at a financial cost. The data clearly show that farms that have already adopted sustainable practices, such as reducing antibiotic use, improving resource efficiency, or strengthening internal management, perform at least as well as conventional ones, and in many cases even better.

Such findings can be powerfully used in awareness campaigns and farmer outreach initiatives. Messages like “Your peers who cut antibiotic use didn’t lose money, they actually made more” can have a stronger impact than abstract policy statements. In this sense, the study not only informs academic debates but also provides practical tools and persuasive evidence to support the long-term integration of sustainability into agricultural business models.

4.5. Research Limitations

When interpreting the findings of this study, it is important to recognize several inherent limitations that may have influenced the results. First, the sample size, 83 farms, while adequate in relation to the total number of commercial swine farms registered in Romania (361), does not permit complete statistical generalization. There is also a possibility of selection bias. Likely, farms more inclined toward sustainability topics were also those more willing to participate. For instance, many responses came from members of a professional association known for its focus on environmental and animal welfare issues. This could mean that the average scores for Awareness and Desire are slightly higher than what would be found in the general farming population, where some producers might remain indifferent or even resistant to such topics. On the other hand, the opposite scenario is also possible; some of the most advanced or best-performing farms may have chosen not to participate, perhaps to avoid sharing sensitive data, and therefore their practices were not captured. To validate these findings, future research could employ randomized sampling or larger datasets.

Second, some of the variables analyzed were self-reported, especially the performance indicators. This type of data collection can introduce small inaccuracies or reporting biases. Even though anonymity was guaranteed, there remains a chance that certain respondents adjusted their answers slightly, for example, by underreporting antibiotic use to appear more compliant with sustainability norms. To reduce such risks, the questionnaire was carefully phrased in a neutral and non-evaluative tone, emphasizing that the study aimed to collect information, not to judge participants. Logical consistency checks were also carried out (for example, verifying that reported zero antibiotic use did not coincide with abnormally high mortality rates). Fortunately, no major contradictions of this kind were identified. Nonetheless, future studies might benefit from combining survey data with objective sources, such as veterinary prescription records or drug sales data, to ensure more precise validation.

Third, it must be acknowledged that the ADKAR model itself presents certain conceptual simplifications. It divides the process of change into five sequential stages, but in reality, transformation processes are rarely linear. A farmer, for instance, may have limited knowledge yet still manage to implement effective changes with the help of an external consultant. Similarly, reinforcement of new practices does not always arise internally; it can also be externally imposed, through veterinary inspections or regulatory compliance audits.

Also, another important limitation that must be acknowledged concerns the structural effect of economies of scale. Larger farms typically face lower unit costs, stronger bargaining positions for feed and veterinary inputs, and a more efficient use of labor, all of which improve financial indicators regardless of their sustainability orientation or ADKAR profile. Evidence from similarly fragmented systems, such as Poland, shows cost gaps of more than 10% between small and integrated units, suggesting that part of the correlation between ADKAR-S scores and economic performance reflects these built-in advantages rather than change readiness alone.

Smaller farms, by contrast, often rely on fewer antibiotics simply because they manage fewer animals and experience reduced health pressures, or because swine production remains a secondary activity with limited incentives for technological upgrading.