The Role of Corporate Governance in Shaping Sustainable Practices and Economic Outcomes in Small- and Medium-Sized Farms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Formulation of Hypotheses

2.1. Corporate Governance and Sustainable Practices

2.2. Sustainable Practices and Economic Performance

3. Analytical Methodology

3.1. Analysis Procedure

3.2. Data

4. Results

4.1. Factor Analysis

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

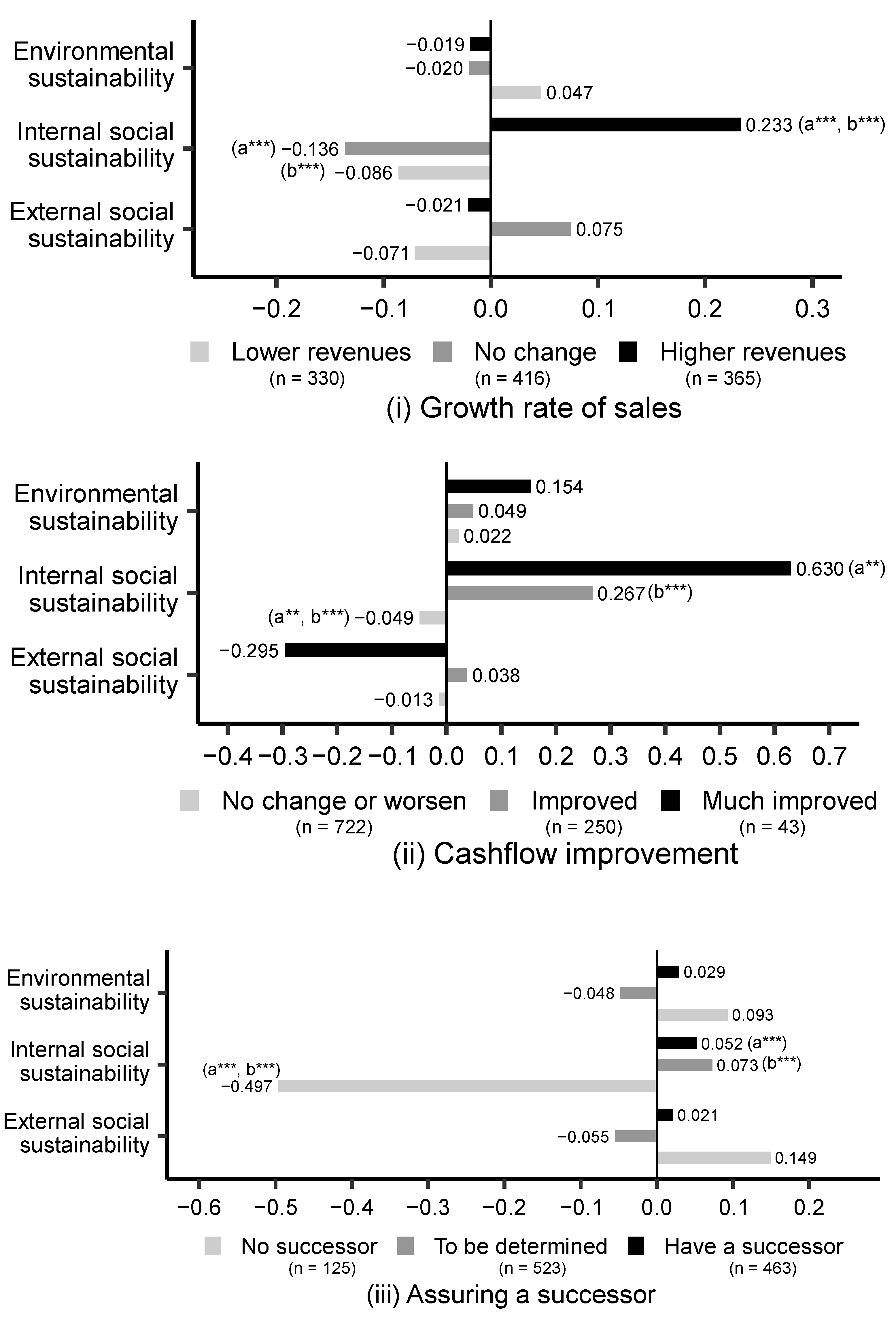

4.3. Relationship Between Sustainable Practices and Economic Performance

5. Discussion

5.1. Contrasting Sustainability–Governance Links

5.2. Practical Implication

5.3. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | environmental, social, and governance |

| SME | small- and medium-sized enterprise |

| CG | corporate governance |

| CSR | corporate social responsibility |

| SEW | socioemotional wealth |

| RBV | resource-based view |

| VRIO | value, rarity, inimitability, and organization |

| CSV | creating shared value |

| CFI | comparative fit index |

| GFI | goodness-of-fit index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| RMSEA | root mean square error of approximation |

| SRMR | standardized root mean square residual |

References

- Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. Global Sustainable Investment Review. Available online: https://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/GSIA-Report-2022.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Martín-Moreno, J.; Khan, S.A.; Hussain, N. Socio-emotional Wealth and Corporate Responses to Environmental Hostility: Are Family Firms More Stakeholder Oriented? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 30, 1003–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memili, E.; Fang, H.; Koc, B.; Yildirim-Öktem, Ö.; Sonmez, S. Sustainability Practices of Family Firms: The Interplay between Family Ownership and Long-Term Orientation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, S. Drivers of Proactive Environmental Strategy in Family Firms. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirole, J. Corporate Governance. Econometrica 2001, 69, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M.A.; Jo, H. Corporate Governance and CSR Nexus. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. The Causal Effect of Corporate Governance on Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, J.; Duran, P.; Gómez-Mejía, L.; Sanchez-Bueno, M.J. Socioemotional Wealth and Family Firm Performance: A Meta-Analytic Integration. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2023, 14, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Zanhour, M.; Keshishian, T. Peculiar Strengths and Relational Attributes of SMEs in the Context of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 87, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.J.; Pavelin, S. Corporate Reputation and Social Performance: The Importance of Fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How Does Corporate Social Responsibility Contribute to Firm Financial Performance? The Mediating Role of Competitive Advantage, Reputation, and Customer Satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyder, M.; Theuvsen, L. Determinants and Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility in German Agribusiness: A PLS Model. Agribusiness 2012, 28, 400–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, H.; Theuvsen, L. Corporate Social Responsibility: Exploring a Framework for the Agribusiness Sector. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2017, 30, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Makri, M.; Kintana, M.L. Diversification Decisions in Family-controlled Firms. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.G., Jr.; Whetten, D.A. Family Firms and Social Responsibility: Preliminary Evidence from the S&P 500. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Larraza-Kintana, M.; Garcés-Galdeano, L.; Berrone, P. Are Family Firms Really More Socially Responsible? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1295–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.C.; Watson, J.; Woodliff, D. Corporate Governance Quality and CSR Disclosures. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, H.; Kessler, A.; Rusch, T.; Suess-Reyes, J.; Weismeier-Sammer, D. Capturing the Familiness of Family Businesses: Development of the Family Influence Familiness Scale (FIFS). Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 709–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Haynes, K.T.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.L.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-Controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbach de Castro, L.R.; Aguilera, R.V.; Crespí-Cladera, R. Family Firms and Compliance: Reconciling the Conflicting Predictions Within the Socioemotional Wealth Perspective. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2017, 30, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swab, R.G.; Sherlock, C.; Markin, E.; Dibrell, C. “SEW” What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? A Review of Socioemotional Wealth and a Way Forward. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2020, 33, 424–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, C.; Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional Wealth and Proactive Stakeholder Engagement: Why Family-Controlled Firms Care More about Their Stakeholders. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1153–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Larraza-Kintana, M. Socioemotional Wealth and Corporate Responses to Institutional Pressures: Do Family-Controlled Firms Pollute Less? Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 82–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M.; Uyar, A. Green Logistics Performance and Sustainability Reporting Practices of the Logistics Sector: The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavana, G.; Gottardo, P.; Moisello, A.M. Sustainability Reporting in Family Firms: A Panel Data Analysis. Sustainability 2017, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L.; Jaskiewicz, P. Do Family Firms Have Better Reputations than Non-Family Firms? An Integration of Socioemotional Wealth and Social Identity Theories. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krechovská, M.; Procházková, P.T. Sustainability and Its Integration into Corporate Governance Focusing on Corporate Performance Management and Reporting. Procedia Eng. 2014, 69, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebacq, T.; Baret, P.V.; Stilmant, D. Sustainability Indicators for Livestock Farming. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meul, M.; Passel, S.; Nevens, F.; Dessein, J.; Rogge, E.; Mulier, A.; Hauwermeiren, A. MOTIFS: A Monitoring Tool for Integrated Farm Sustainability. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 28, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calker, K.J.; Berentsen, P.B.M.; Giesen, G.W.J.; Huirne, R.B.M. Identifying and Ranking Attributes That Determine Sustainability in Dutch Dairy Farming. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures TCFD. Implementing the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. 2021. Available online: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/07/2021-TCFD-Implementing_Guidance.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Japan Exchange Group; Tokyo Stock Exchange. Practical Handbook for ESG Disclosure. 2020. Available online: https://www.jpx.co.jp/english/corporate/sustainability/esg-investment/handbook/b5b4pj000003dkeo-att/handbook.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Bilal, F.M.; Zaman, R.; Sarraj, D.; Khalid, F. Examining the Extent of and Drivers for Materiality Assessment Disclosures in Sustainability Reports. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 965–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. Firm Performance: The Interactions of Corporate Social Performance with Innovation and Industry Differentiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. A Resource-Based Perspective on Corporate Environmental Performance and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 40, 534–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The Corporate Social Performance--Financial Performance Link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.-T.A.; Velez-Ocampo, J.; Alejandra, G.-P.M. A Literature Review on the Causality between Sustainability and Corporate Reputation: What Goes First? Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate Responsibility and Financial Performance: The Role of Intangible Resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Fernández-Salinero, S.; Topa, G. Sustainability in Organizations: Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility and Spanish Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A. Sustainability Reporting and Agriculture Industries’ Performance: Worldwide Evidence. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 12, 769–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Wright, C. Fashion or Future: Does Creating Shared Value Pay? Account. Financ. 2018, 58, 1111–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Dharwadkar, R. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Moderating Roles of Attainment Discrepancy and Organization Slack. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2011, 19, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Menghwar, P.S.; Daood, A. Creating Shared Value: A Systematic Review, Synthesis and Integrative Perspective. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikefe, G.; Zubairu, U.; Araga, S.; Maitala, F.; Ediuku, E.; Anyebe, D. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) by Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): A Systematic Review. Small Bus. Int. Rev. 2020, 4, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamajón, L.G.; Font, X. Corporate Social Responsibility in Tourism Small and Medium Enterprises Evidence from Europe and Latin America. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 7, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems Guidelines; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i3957e (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Global Reporting Initiative Standards. GRI 13: Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fishing Sectors. 2022. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/media/i0jjkpze/gri13_aafsectors_2022_faqs_post-launch.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Ryabota, V.; Alexey, K.V.; Helen, C.; Axel, K. SME Governance Guidebook. 2019. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2010/sme-governance-guidebook (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- The Small and Medium Enterprise Agency. Guidelines on Governance for theUtilization of Equity Finance by SMEs. 2023. Available online: https://www.chusho.meti.go.jp/koukai/kenkyukai/equityfinance/guidance/guidance_02.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- De Olde, E.M.; Oudshoorn, F.W.; Sørensen, C.A.G.; Bokkers, E.A.M.; De Boer, I.J.M. Assessing sustainability at farm-level: Lessons learned from a comparison of tools in practice. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 66, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). Agricultural Products Sustainability Accounting Standard; Sustainability Accounting Standards Board: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://sasb.ifrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CN0101_Agricultural-Products_Standard.pdf?hsCtaTracking=2ee1eab1-6d47-4639-8f4f-8d4a02ab9d0a%7C57ebbaaf-38b3-4b72-aa66-ba31aca0b686 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Holgado-Tello, F.P.; Chacón-Moscoso, S.; Barbero-García, I.; Vila-Abad, E. Polychoric versus Pearson Correlations in Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Ordinal Variables. Qual. Quant. 2010, 44, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouillette-Alarie, S.; Babchishin, K.M.; Hanson, R.K.; Helmus, L.-M. Latent Constructs of the Static-99R and Static-2002R: A Three-Factor Solution: A Three-Factor Solution. Assessment 2016, 23, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messineo, L.; Allegra, M.; Seta, L. Self-Reported Motivation for Choosing Nursing Studies: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, J.C.; Allen, D.G.; Scarpello, V. Factor Retention Decisions in Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Tutorial on Parallel Analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2004, 7, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagnoli, E.; Velicer, W.F. Relation of Sample Size to the Stability of Component Patterns. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Watkins, D.; Harris, N.; Spicer, K. The Relationship between Succession Issues and Business Performance: Evidence from UK Family SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2004, 10, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruta, D. Japan’s Elderly Small Business Managers: Performance and Succession. J. Asian Econ. 2020, 66, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2009; pp. 89–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, S.; Yagi, H.; Garrod, G. Determinants of Farm Diversification: Entrepreneurship, Marketing Capability and Family Management. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2020, 32, 607–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesios, C.; Skouloudis, A.; Dey, P.K.; Abdelaziz, F.B.; Kantartzis, A.; Evangelinos, K. Impact of Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises Sustainability Practices and Performance on Economic Growth from a Managerial Perspective: Modeling Considerations and Empirical Analysis Results. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneirson, J.F. Green Is Good: Sustainability, Profitability, and a New Paradigm for Corporate Governance. Lowa Law Rev. 2009, 94, 987–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Del Baldo, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Governance in Italian SMEs: The Experience of Some “Spirited Businesses”. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howorth, C.; Kemp, M.; Governance in Family Businesses: Evidence and Implications. IFB Research Foundation. 2019. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/64dcaa8b96fc07122c799a2f/t/6532813fcdcba16dcfed82a8/1697808739220/governance-in-family-businesses-evidence-and-implications_web.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

| Variables | Mean | Standard | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation | ||||

| Number of employees | 19.25 | 20.25 | (persons) includes those working who are full-time part-time employees | |

| Years in operation | 23.19 | 13.76 | (years) calculated from the year of establishment as a corporation | |

| Population density | 0.85 | 1.38 | (1000 persons/km2) | |

| Business diversification | 2.06 | 1.65 | Number of businesses related to agriculture | |

| Sustainable corporate governance | 4.37 | 3.12 | Total of the following 13 items | |

| Break down | Top managers | |||

| Identifies social and environmental issues | 0.38 | 1 = Firm adopts this practice. | ||

| Analyzes and understands the effects | 0.46 | |||

| Includes sustainable practices in management philosophy | 0.36 | |||

| Includes sustainable practices in the business strategy and planning | 0.41 | |||

| Sets specific goals for sustainable practices | 0.25 | |||

| Emphasizes the firm’s social responsibility | 0.49 | |||

| Takes the lead in implementing sustainable practices | 0.43 | |||

| Clarifies responsibilities and authority vis-a-vis sustainable practices | 0.21 | |||

| Evaluates the track record of sustainable practices | 0.19 | |||

| Revises future plans and policies based on track record | 0.37 | |||

| Employees | ||||

| Understands the purposes and effects of sustainable practices | 0.33 | |||

| Proactively partakes in sustainable practices | 0.23 | |||

| Proactively proposes approaches to improve sustainable practices | 0.28 | |||

| Expected successor not a family member | 0.10 | 1 = Successor is nominated outside family | ||

| Farm type | Paddy farming | 0.35 | 1 = Firm adopts this farm type. | |

| Outdoor vegetable growing | 0.18 | |||

| Greenhouse vegetable growing | 0.18 | |||

| Fruit growing | 0.09 | |||

| Cattle or cow raising | 0.08 | |||

| Pig or poultry raising | 0.12 | |||

| Sustainable Practices | Items | Mean | Factor Loading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Social | External Social | Environmental | |||

| Response to climate change | (1) Installation of energy-saving facilities/machinery/smart devices, (2) reduction of methane emissions, (3) use of renewable energy, and (4) carbon retention in farmland | 0.79 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| Water and soil conservation | (1) Installation of water-saving technologies, (2) soil maintenance through crop rotation, (3) efforts to reduce the use of farm chemicals and chemical fertilizers, (4) prevention of soil runoff, and (5) use of manure | 1.44 | 0.06 | −0.19 | 0.90 |

| Local ecosystem conservation | (1) Protection of plant and animal habitats, (2) organic farming, (3) securing new plant and animal habitats, and (4) integrated pest and weed management | 0.57 | −0.06 | 0.28 | 0.57 |

| Resource recycling agriculture | (1) Implementation of crop–livestock integration and (2) use of crop residue | 0.64 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.46 |

| Rural landscape conservation | (1) Beautification of the rural landscape, (2) introduction of ornamental/landscape crops, and (3) solving farmland abandon | 0.77 | −0.02 | 0.28 | 0.49 |

| Efficient use of local resources | (1) Development of businesses that uses local products and (2) development of businesses through agriculture-commerce-industry collaboration | 0.46 | −0.08 | 0.76 | 0.07 |

| Product safety | (1) Supervision of production using Good Agricultural Practice (GAP), (2) traceability assurance, and (3) supervision of agricultural product processing | 0.96 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.33 |

| Care farming | (1) Hiring of persons with disabilities, (2) employment and social rehabilitation assistance, and (3) hiring of persons who require care | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.54 | −0.01 |

| Promotion of food education | (1) Supply of agricultural products to school lunches, (2) participation in food education-related events, (3) agricultural experience farms, and (4) lectures related to food education | 0.93 | −0.01 | 0.62 | 0.15 |

| Consideration for animal welfare | (1) Consultations with veterinarians, (2) implementation of pasturage and open-space breeding, (3) health management of livestock barns, (4) observation and alleviation of stress behaviors, and 5) assurance of adequate breeding space in livestock barns | 0.59 | 0.24 | 0.28 | -0.35 |

| Development of the community and food culture | (1) Production of traditional agricultural products, (2) participating in traditional events related to farming and food, and (3) initiatives regarding traditional farming methods | 0.27 | −0.22 | 0.82 | 0.15 |

| Food poverty and access to food | (1) Participation in food banks, (2) participation in children’s cafeterias, and (3) programs and support for mobile sales and home delivery businesses | 0.28 | −0.03 | 0.69 | −0.01 |

| Workplace safety | (1) Participation in training on accident prevention and (2) development of an accident prevention manual | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.23 |

| Improved treatment of employees | (1) Regular salary raises, (2) enhancement of employee benefits, and (3) improvement of the annual paid leave system | 1.61 | 0.89 | −0.23 | 0.05 |

| Improved health conditions for employees | (1) Periodic health examinations and (2) measures addressing mental health considerations | 0.92 | 0.93 | −0.18 | 0.02 |

| Employee participation in management | (1) Notification of the management strategy/plan, (2) participation in important decision-making events, (3) disclosure of management and financial data, and (4) implementation of an evaluation system aligned with business plans | 1.07 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.13 |

| Human resource investment | (1) Regular training implementation, (2) support for participation in external training, and (3) assignment of mentors | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Hiring of diverse employees | Regular employment of (1) women, (2) foreign nationals, (3) people with disabilities, and (4) promotion of these people to managerial positions | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.11 | −0.04 |

| Cumulative proportion of variance explained | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.50 | ||

| General Corporate Governance (GCG) | Selection Percentage | Factor Loading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCG_ Broad | GCG_ Vision | GCG_ Executives | ||

| My farm | ||||

| Determines a management philosophy | 55.3 | −0.10 | 0.72 | 0.09 |

| Determines policies and principles when acting in accordance with the management philosophy | 25.0 | −0.06 | 1.13 | −0.18 |

| Formulates a long-term management plan and presents it to executives and employees | 23.6 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.03 |

| Holds regular meetings of executives | 29.3 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.77 |

| Promotes non-family members to executive positions | 22.1 | −0.17 | −0.05 | 0.87 |

| Sets clear responsibilities for executives | 22.6 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.51 |

| Gathers information on the legal system with regard to environmental protection and social issues | 13.9 | 0.44 | 0.19 | −0.02 |

| Understands and observes laws related to employment and the firm’s operations | 33.2 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Investigates the risks affecting business continuity | 25.5 | 0.88 | −0.12 | −0.11 |

| Sets financial goals other than sales | 14.0 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| Presents financial data to related stakeholders other than financial institutions | 19.4 | 0.54 | −0.02 | 0.19 |

| Ties executive compensation to economic performance | 17.1 | 0.58 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Has formulated and is executing plans for management succession | 9.4 | 0.59 | −0.01 | −0.10 |

| Cumulative proportion of variance explained | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.49 | |

| Explanatory Variables | Explained Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable CG | Environmental Sustainability | Internal Social Sustainability | External Social Sustainability | ||||||

| Coef. | p-Value | Coef. | p-Value | Coef. | p-Value | Coef. | p-Value | ||

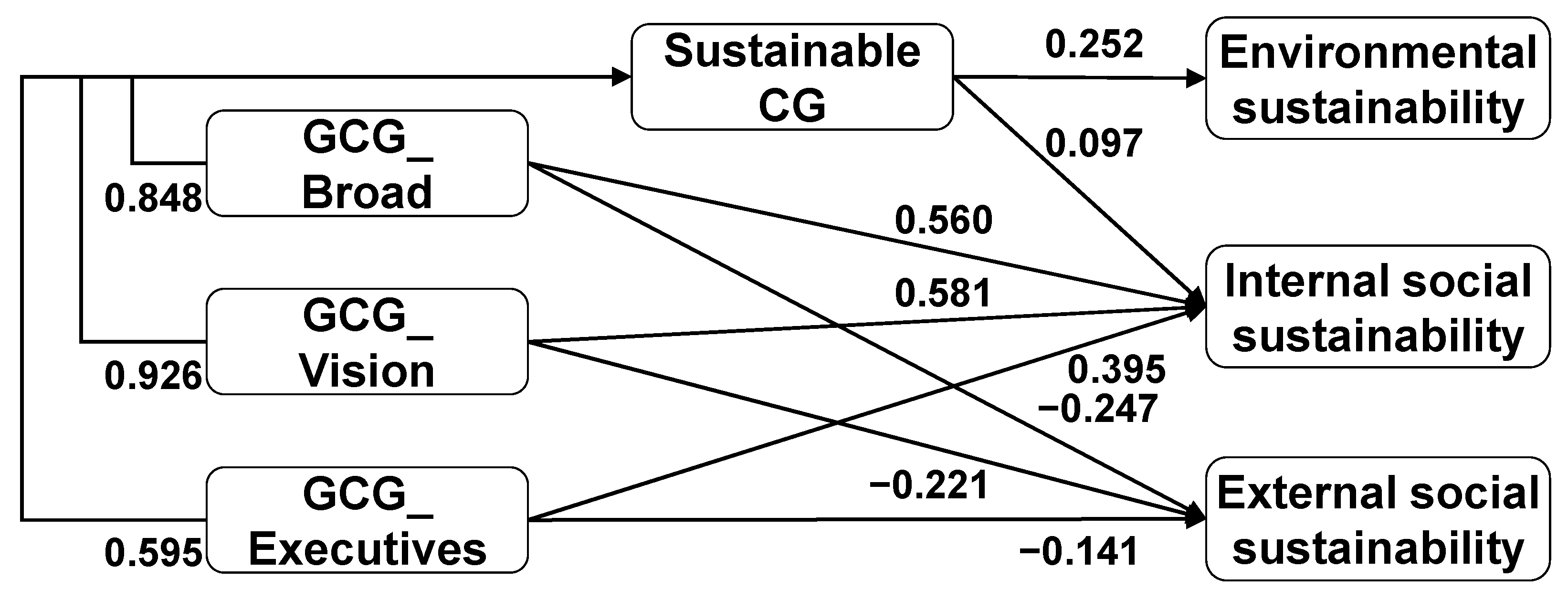

| CG | GCG_Broad | 0.848 (0.039) | <0.001 *** | −0.001 (0.057) | 0.990 | 0.560 (0.048) | <0.001 *** | −0.247 (0.061) | <0.001 *** |

| GCG_Vision | 0.926 (0.040) | <0.001 *** | −0.008 (0.062) | 0.902 | 0.581 (0.051) | <0.001 *** | −0.221 (0.067) | 0.001 ** | |

| GCG_Executives | 0.595 (0.035) | <0.001 *** | 0.003 (0.046) | 0.948 | 0.395 (0.041) | <0.001 *** | −0.141 (0.050) | 0.004 ** | |

| Sustainable CG | 0.252 (0.033) | <0.001 *** | 0.097 (0.033) | 0.003 ** | 0.053 (0.039) | 0.169 | |||

| covariates | Log (no. of executives and employees) | 0.008 (0.028) | 0.774 | −0.120 (0.028) | <0.001 *** | 0.224 (0.032) | <0.001 *** | −0.043 (0.036) | 0.242 |

| No. of years in operation | −0.066 (0.025) | 0.009 ** | −0.071 (0.027) | 0.009 ** | 0.037 (0.026) | 0.163 | −0.008 (0.029) | 0.777 | |

| Outdoor vegetable growing | −0.007 (0.029) | 0.818 | 0.027 (0.032) | 0.379 | 0.011 (0.031) | 0.723 | −0.011 (0.039) | 0.738 | |

| Greenhouse vegetable growing | −0.065 (0.029) | 0.027 * | −0.077 (0.034) | 0.014 * | −0.053 (0.034) | 0.118 | 0.089 (0.029) | 0.025 * | |

| Fruit farming | 0.007 (0.028) | 0.790 | −0.077 (0.026) | 0.005 ** | 0.022 (0.023) | 0.338 | 0.037 (0.030) | 0.200 | |

| Cattle or cow raising | −0.018 (0.025) | 0.484 | −0.166 (0.025) | <0.001 *** | 0.052 (0.028) | 0.061 | 0.090 (0.036) | 0.002 ** | |

| Pig or poultry raising | 0.011 (0.029) | 0.707 | −0.339 (0.028) | 0.000 *** | 0.012 (0.031) | 0.695 | 0.221 (0.034) | <0.001 *** | |

| Expected successor not a family member | −0.027 (0.025) | 0.266 | −0.009 (0.029) | 0.751 | 0.059 (0.033) | 0.068 | |||

| Business diversification | 0.095 (0.029) | 0.001 ** | −0.130 (0.029) | <0.001 *** | 0.242 (0.033) | <0.001 *** | |||

| Population density | −0.084 (0.037) | 0.025 * | −0.011 (0.038) | 0.768 | 0.101 (0.044) | 0.022 * | |||

| Population density 2 | 0.058 (0.023) | 0.012 ** | 0.017 (0.026) | 0.508 | −0.080 (0.028) | 0.005 ** | |||

| chi-square/df = 3.640; CFI = 0.995; GFI = 0.995; TLI = 0.930; RMSEA = 0.049; SRMR = 0.007 | |||||||||

| Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Internal Social | External Social | Environmental | Internal Social | External Social | Environmental | Internal Social | External Social | |

| (Sustainability) | (Sustainability) | (Sustainability) | |||||||

| GCG_ Broad | −0.001 | 0.560 *** | −0.247 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.083 ** | 0.045 | 0.213 *** | 0.643 *** | −0.202 *** |

| GCG_ Vision | −0.008 | 0.581 *** | −0.221 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.090 ** | 0.049 | 0.226 *** | 0.671 *** | −0.172 ** |

| GCG_ Executives | 0.003 | 0.395 *** | −0.141 ** | 0.150 *** | 0.058 ** | 0.032 | 0.153 *** | 0.452 *** | −0.110 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshida, S. The Role of Corporate Governance in Shaping Sustainable Practices and Economic Outcomes in Small- and Medium-Sized Farms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177810

Yoshida S. The Role of Corporate Governance in Shaping Sustainable Practices and Economic Outcomes in Small- and Medium-Sized Farms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):7810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177810

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshida, Shingo. 2025. "The Role of Corporate Governance in Shaping Sustainable Practices and Economic Outcomes in Small- and Medium-Sized Farms" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 7810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177810

APA StyleYoshida, S. (2025). The Role of Corporate Governance in Shaping Sustainable Practices and Economic Outcomes in Small- and Medium-Sized Farms. Sustainability, 17(17), 7810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177810