Study on the Interaction Mechanism Between Sandy Soils and Soil Loosening Device in Xinjiang Cotton Fields Based on the Discrete Element Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structure and Working Principle of the SLD

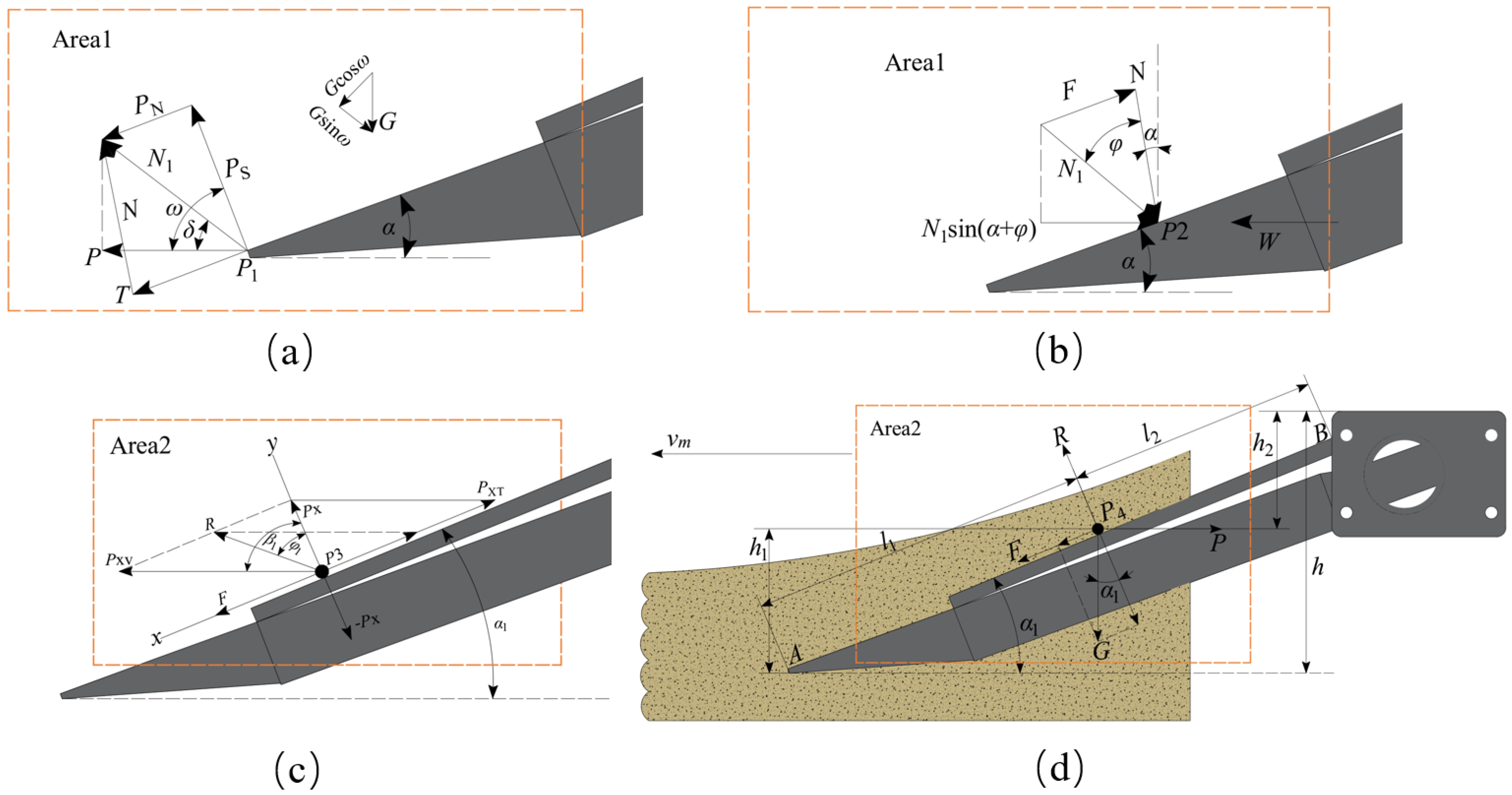

2.2. Stress Analysis of SLD

2.3. Discrete Element Modeling of Interactions Between Cotton Field Sandy Soil and SLD

2.3.1. Establishment of DEM Model for Cotton Field Sandy Soil

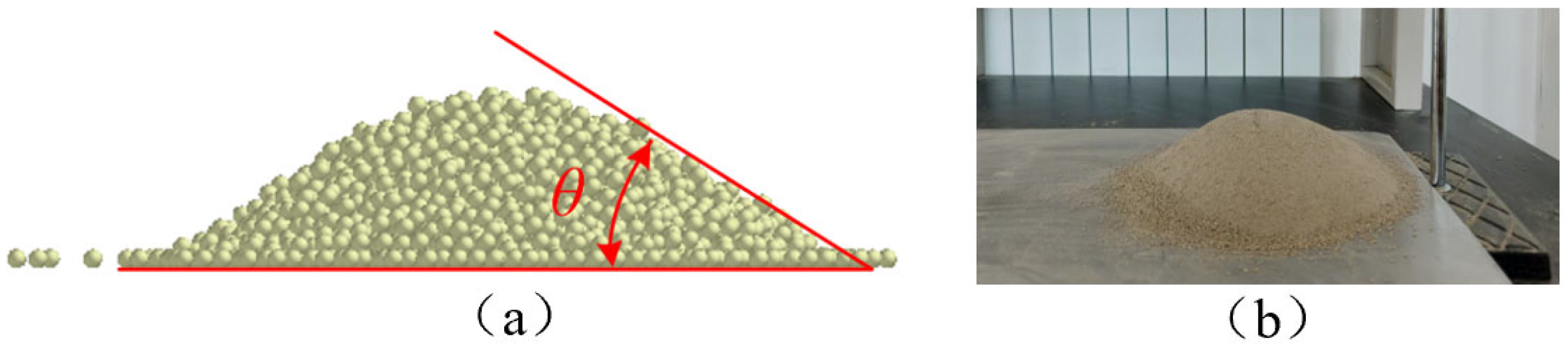

2.3.2. Soil Angle of Repose Simulation (ARS) Experiment

2.3.3. Calibration of Soil Parameters in Cotton Fields

2.3.4. Calibration and Validation of Simulation Parameters

2.4. Soil Model Validation

2.4.1. Soil Angle of Repose Validation

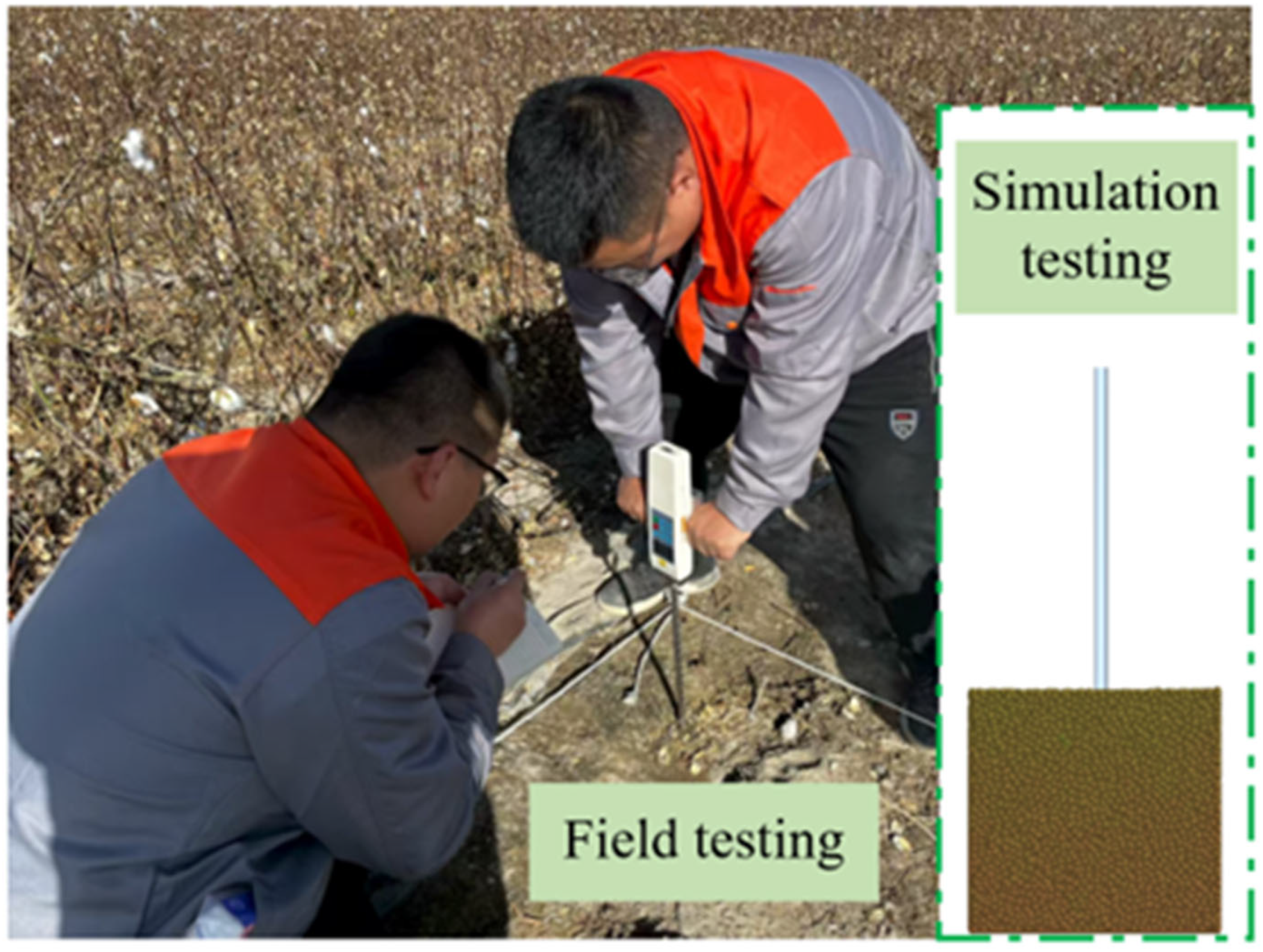

2.4.2. Validation of Soil Firmness Using the Cone Penetration Test

2.5. Soil-Lift Device-Soil Interaction Model

2.6. Field Trials

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Calibration of Soil Parameters

3.2. Central Composite Design Experimental Parameter Optimization Results

3.2.1. Analysis of the Effect of Interaction Factors on SDC

3.2.2. Response Surface Analysis

3.2.3. Parameter Optimization

3.3. DEM Simulation Results

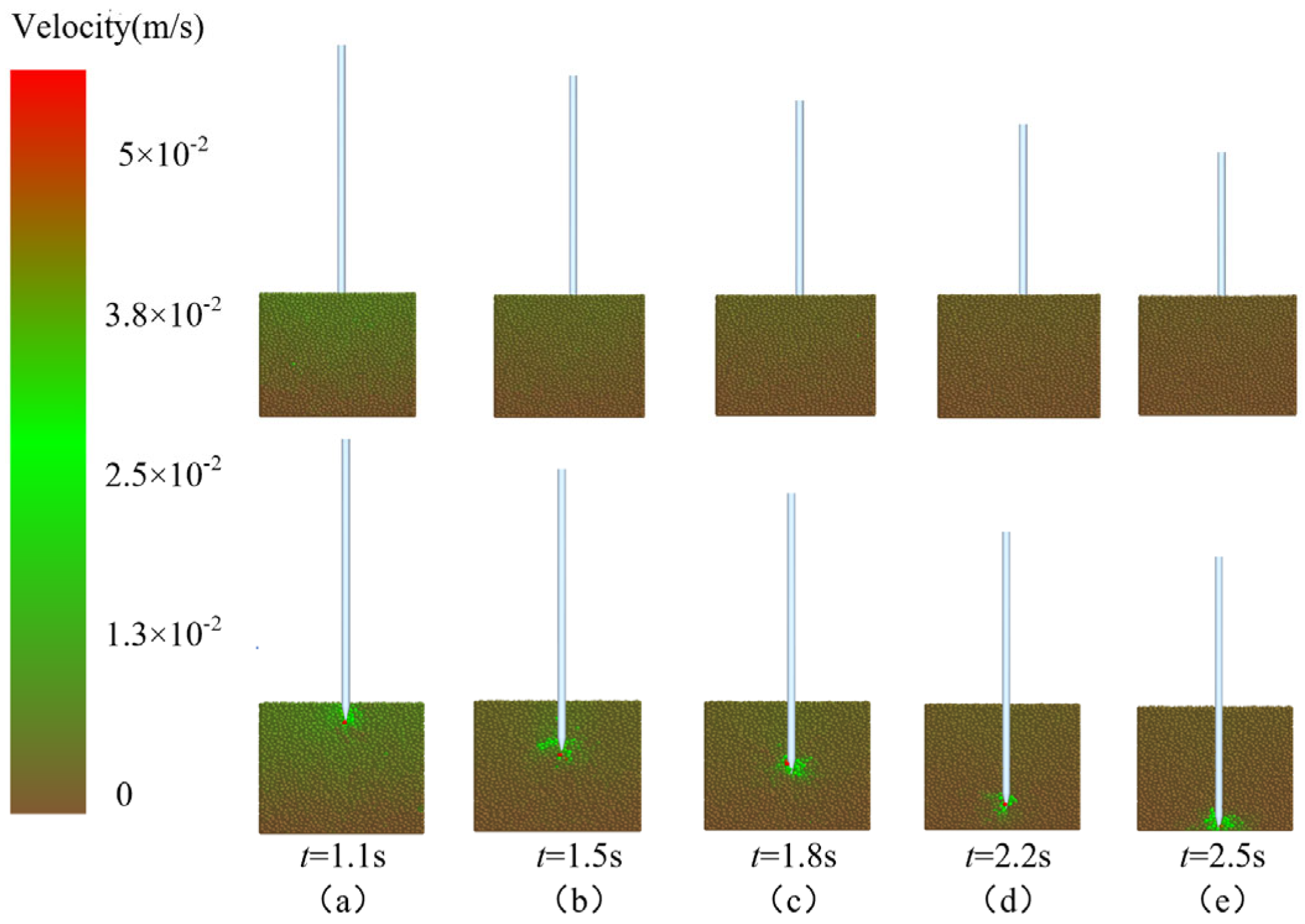

3.3.1. Soil Disturbance Process

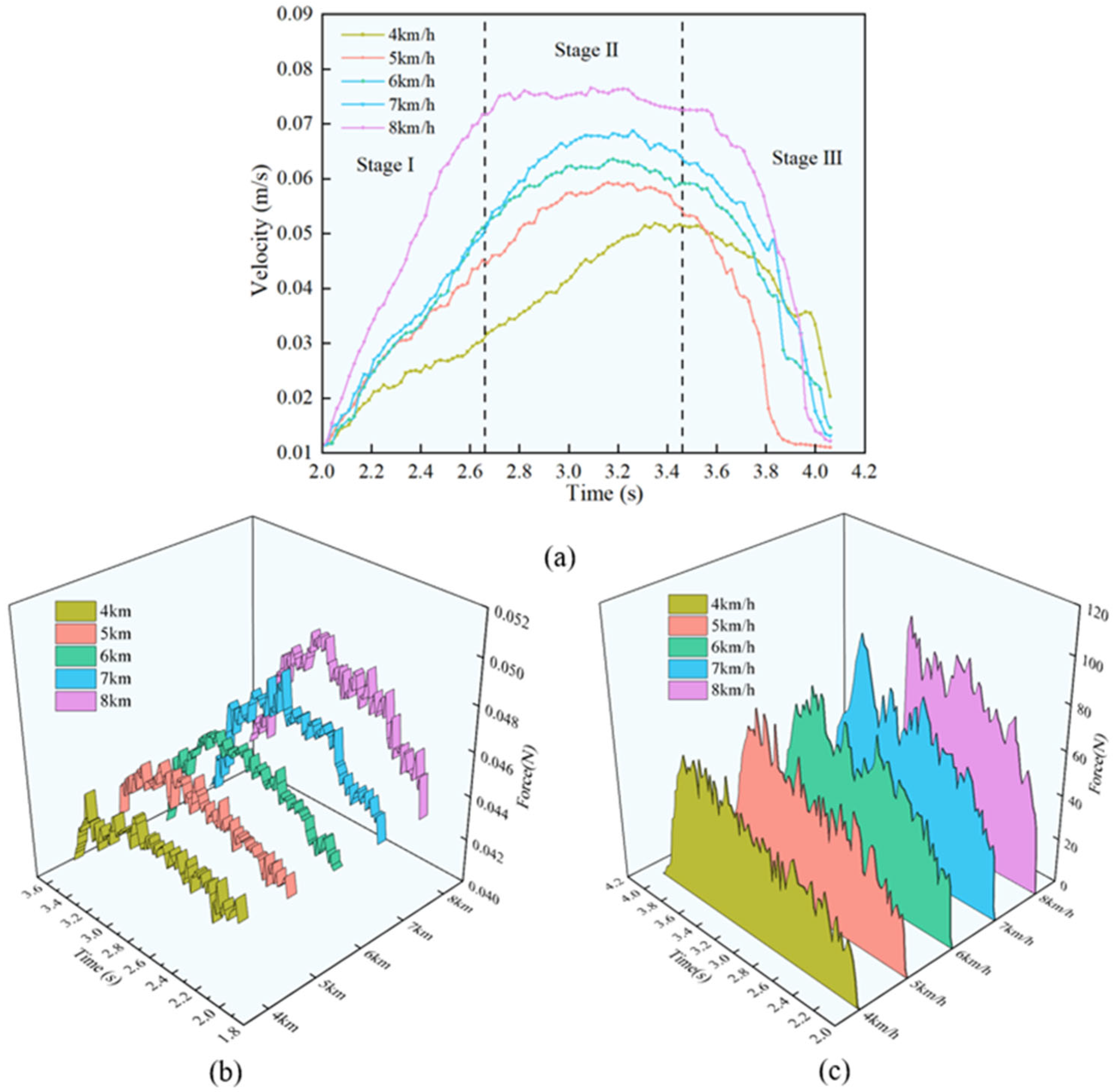

3.3.2. Movement of Soil Particles During Operation

3.3.3. Force Analysis of Soil Particles During Operation

3.3.4. Force Analysis of the SLD

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Z.Y.; Wang, X.S.; Liu, D.W.; Xie, F.P.; Ashwehmbom, L.G.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Tang, Q.J. Calibration of discrete element parameters and experimental verification for modelling subsurface soils. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 212, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.C.; Ding, K.Q.; Xia, J.J.; Zhang, G.Z.; Wang, Y.; Kang, Q.X.; Tang, N.R.; Liu, W.R. Calibration of disturbed-saturated paddy soil discrete element parameters based on slump test. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.L.; Hu, J.R.; Liu, H.R.; Ren, L.Z.; Zhou, M.L.; Yang, Q.Z.; Li, B.; Chen, X.G. Parameter calibration and experiment of the discrete element contact model of water-containing sandy soil particles. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.L.; Tang, Z.H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, J.B.; Meng, X.J.; Liang, Y.C. Calibration of the discrete element parameters for the soil model of cotton field after plowing in Xinjiang of China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Niu, C.; Yan, C.G.; Tan, H.C.; Xu, L.M. Discrete element method optimisation of a scraper to remove soil from ridges formed to cold-proof grapevines. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 210, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xu, L.M.; Xu, S.C.; Tan, H.C.; Song, J.F.; Shen, C.C. Wear study on flexible brush-type soil removal component for removing soil used to protect grapevines against cold. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 228, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, X.C.; Cheng, X.P.; Wei, Z.C.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, K.L. The impact of ‘T’-shaped furrow opener of no-tillage seeder on straw and soil based on discrete element method. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xia, J.F.; Zheng, K.; Liu, G.Y.; Wei, Y.S.; Liu, Z.Y.; Li, P.L.; Liu, H.P. Construction and analysis of a discrete element model for calculating friction resistance of the typical rotary blades. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Li, X.Y.; Hu, B.; Gu, T.L.; Wang, Z.J.; Wang, H.L. Analysis of the resistance reduction mechanism of potato bionic digging shovels in clay and heavy soil conditions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Yu, S.Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, L.X. Study on rotary tillage cutting simulations and energy consumption predictions of sandy ground soil in a Xinjiang cotton field. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.X.; Qu, H.; Liu, X.F.; Zhang, H.C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L. Design and experiment of spade tooth film lifting device for residual film recycling machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.M.; Wang, S.G.; Yan, L.M.; Wang, N.N.; Di, M.L.; Du, J.W. Design and experiment of loosen shovel installed on plastic film collecting machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2016, 47, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Jian, J.M.; Tian, Y.T.; Sun, F.C.; Zhang, M.J.; Wang, S.G. Analysis and experiment of filming mechanism of rotary film-lifting device of residual film recycling machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2018, 49, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.L. Research on the Mechanism and Device for Film Surface Cleaning and Stubble Crushing of Corn Stubble Land in Hexi Irrigation District; Gansu Agricultural University: Gansu, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Lu, T.; Zheng, S.; Tian, Y.; Han, M.M.; Tai, M.H.; He, X.N.; Li, H.X.; Wang, D.W.; Zhao, Z. Parameter calibration method for discrete element simulation of soil–wheat crop residues in saline–alkali coastal land. Agriculture 2025, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Huang, S.H.; Yang, C.Y.; Liu, S.L.; Wang, K.L.; Lu, Y.P.; Wang, J.S. Calibration and testing of discrete element simulation parameters for ultrasonic vibration-cutter-soil interaction model. Agriculture 2024, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Xin, Z.B.; Yuan, J.; Gao, Z.H.; Tian, Y.; Xia, C.; Liu, X.M.; Wang, D.W. Calibration of discrete element simulation parameters and model construction for the interaction between coastal saline alkali soil and soil-engaging components. Agriculture 2024, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.T.; You, Y.; Yang, D.Q.; Wang, D.C.; Hui, Y.T.; Li, D.Y.; Wu, H.H. Calibration and verification of discrete element parameters of surface soil in camellia oleifera forest. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Wang, J.L.; Liu, M.; Wang, P.Y.; Fu, D.P.; Feng, W.Z.; Chu, L.D.; Ning, Y.C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.J. Parameter calibration for discrete element simulation of the interaction between loose soil and thrown components after ginseng land tillage. Processes 2024, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Shen, K.; Guo, Y.; Xiong, H.B.; Lin, J.Z. Discrete element simulations of flexible ribbon-like particles. Powder Technol. 2023, 429, 118950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, G.Q.; Li, M.Y.; Li, S.F.; Zhou, L.M.; Liang, J.; Xie, X.L.; Hou, B.H. Optimization of transplanting mechanism working parameters based on a coupled machine-soil-pot seedling model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 238, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Z.; Zhang, Q.K.; Huang, Y.X.; Ji, J.T. An efficient method for determining DEM parameters of a loose cohesive soil modelled using hysteretic spring and linear cohesion contact models. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 215, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Duan, W.W.; Li, Z.Q.; Zhu, Y.J.; Li, D.F.; Liu, Z.; Xu, W.X.; Xiao, M.H.; Zhu, L. A CFD–DEM model for simulating mechanical responses of saturated paddy soil: Model development and experimental verification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 110896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.P.; Wassgren, C.; Ambrose, R.P.K. Development and validation of a DEM model for predicting impact damage of maize kernels. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 224, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.X.; Liao, Q.X.; Wang, X.F.; Kang, Y.; Du, W.B.; Zhang, Q.S. Exploring straw movement through the simulation of shovel-type seedbed preparation machine-straw-soil interaction using the DEM-MBD coupling method. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Diao, P.S.; Zhang, Y.P.; Li, X.H.; Zhao, Y.L.; Zhao, H.D. Design and performance evaluation of notched type discs for application in no-till seeding process using discrete element method and field trials. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 257, 104222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.Y.; Zeng, Z.W.; Gong, H.; Zhou, Y.H.; Qi, L.; Zhen, W.B. Simulation of tensile behavior of tobacco leaf using the discrete element method (DEM). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.T.; Wang, B.B.; He, Z.; Shi, Y.G.; Li, K.; Cui, Y.J.; Yang, Q.C. Fast and precise DEM parameter calibration for Cucurbita ficifolia seeds. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 236, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Luo, Z.T.; Hao, Z.H.; Zheng, E.L.; Yao, H.P.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.C. Investigation on tillage resistance and soil disturbance in wet adhesive soil using discrete element method with three-layer soil-plough coupling model. Powder Technol. 2024, 436, 119463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.C.; Shen, C.C.; Ma, J.L.; Wu, C.L.; Xu, L.M.; Ma, S. The reduction of energy consumption and soil disturbance mechanisms in trenching using biomimetic blades. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 230, 109887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.P.; Li, Z.Z.; Wang, X.; Li, J.Y.; Chen, J.L.; Zhou, H. Parameter optimization and numerical analysis of the double disc digging shovel for corn root-soil complex. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.B.; Wang, Q.J.; Xu, D.J.; Li, H.W.; He, J.; Lu, C.Y. Design and experimental research on the counter roll differential speed solid organic fertilizer crusher based on DEM. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 107748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Soil | Steel | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (kg/m−3) | 1.63 × 103 | 7.27 × 107 | Measurement |

| Shear modulus (Pa) | 1× 106 | 7.83 × 103 | Measurement |

| Poisson ratio | 0.36 | 0.35 | Measurement |

| Soil-steel CRC | 0.42 | [4] | |

| Soil-steel CSF | 0.51 | [4] | |

| Soil-steel CRF | 0.32 | [4] | |

| Factor | −1 | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil CCR XC | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.75 |

| Soil SFC XS | 0.16 | 0.50 | 0.84 |

| Soil RFC XR | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.49 |

| Soil SEC XE | 0 | 4.5 | 9 |

| Test Number | Factor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XC | XS | XR | XE | θS (°) | Y% | |

| 1 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 0 | 31.3 | 9.17 |

| 2 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 39.2 | 13.76 |

| 3 | 0.15 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 38.8 | 12.59 |

| 4 | 0.75 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 31.4 | 8.88 |

| 5 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0 | 30.6 | 11.20 |

| 6 | 0.15 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 0 | 34.3 | 0.46 |

| 7 | 0.15 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 4.5 | 30.2 | 12.36 |

| 8 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 4.5 | 26.9 | 21.94 |

| 9 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 34.5 | 0.12 |

| 10 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 35.8 | 3.89 |

| 11 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 35.7 | 3.60 |

| 12 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.49 | 0 | 33.5 | 2.79 |

| 13 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 32.5 | 5.69 |

| 14 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0 | 34.2 | 0.75 |

| 15 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.49 | 4.5 | 31.5 | 8.59 |

| 16 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 4.5 | 39.5 | 14.63 |

| 17 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 9 | 36.7 | 6.50 |

| 18 | 0.15 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 9 | 39.6 | 14.92 |

| 19 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 9 | 29.7 | 13.81 |

| 20 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 34.7 | 0.70 |

| 21 | 0.15 | 0.5 | 0.49 | 4.5 | 38.7 | 12.30 |

| 22 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.49 | 4.5 | 34.5 | 0.12 |

| 23 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.49 | 9 | 39.6 | 14.92 |

| 24 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 0 | 30.8 | 10.62 |

| 25 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 9 | 35.6 | 3.31 |

| 26 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 4.5 | 29.8 | 13.52 |

| 27 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 4.5 | 29.4 | 14.68 |

| 28 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 9 | 31.6 | 8.30 |

| 29 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 29.5 | 14.39 |

| Source | SS | DF | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 355.08 | 14 | 25.36 | 18.98 | <0.0001 ** |

| XC | 127.40 | 1 | 127.40 | 95.33 | <0.0001 ** |

| XS | 6.31 | 1 | 6.31 | 4.72 | 0.0475 * |

| XR | 138.04 | 1 | 138.04 | 103.29 | <0.0001 ** |

| XE | 27.30 | 1 | 27.30 | 20.43 | 0.0005 ** |

| XCXS | 0.5625 | 1 | 0.5625 | 0.4209 | 0.5270 |

| XCXR | 3.80 | 1 | 3.80 | 2.85 | 0.1138 |

| XCXE | 5.06 | 1 | 5.06 | 3.79 | 0.0720 |

| XSXR | 7.29 | 1 | 7.29 | 5.45 | 0.0349 * |

| XSXE | 4.00 | 1 | 4.00 | 2.99 | 0.1056 |

| XRXE | 12.25 | 1 | 12.25 | 9.17 | 0.0090 ** |

| XC2 | 2.56 | 1 | 2.56 | 1.92 | 0.1879 |

| XS2 | 0.5709 | 1 | 0.5709 | 0.4272 | 0.5240 |

| XR2 | 18.82 | 1 | 18.82 | 14.08 | 0.0021 |

| XE2 | 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.9942 |

| Residual | 18.71 | 14 | 1.34 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 11.64 | 10 | 1.16 | 0.6583 | 0.7309 |

| Pure Error | 7.07 | 4 | 1.77 | ||

| Cor Total | 373.79 | 28 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Soil-soil CCR | 0.28 |

| Soil-soil SFC | 0.67 |

| Soil-soil RFC | 0.14 |

| Soil-steel CRC | 0.42 |

| Soil-steel CSF | 0.51 |

| Soil-steel CRF | 0.32 |

| Soil SEC/J/m2 | 6.95 |

| Code | Factor | |

|---|---|---|

| FS XF/(km/h) | SPD XD (mm) | |

| −1.4.14 | 3.17 | 91.72 |

| −1 | 4 | 100 |

| 0 | 6 | 120 |

| 1 | 8 | 140 |

| 1.414 | 8.83 | 148.28 |

| Test Number | XF | XD | Y1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 66.53 |

| 2 | −1 | −1 | 55.61 |

| 3 | 1 | −1 | 65.72 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 68.86 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 67.95 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 68.23 |

| 7 | −1.414 | 0 | 59.87 |

| 8 | 0 | 1.414 | 67.11 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 66.28 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 66.34 |

| 11 | −1 | 1 | 65.55 |

| 12 | 0 | −1.414 | 62.32 |

| 13 | 1.414 | 0 | 69.64 |

| Source | SS | DF | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 176.51 | 5 | 35.30 | 25.12 | 0.0002 ** |

| A | 92.73 | 1 | 92.73 | 65.98 | <0.0001 ** |

| B | 49.27 | 1 | 49.27 | 35.06 | 0.0006 ** |

| AB | 11.56 | 1 | 11.56 | 8.22 | 0.0241 * |

| A2 | 12.78 | 1 | 12.78 | 9.09 | 0.0195 * |

| B2 | 13.16 | 1 | 13.16 | 9.36 | 0.0183 * |

| Residual | 9.84 | 7 | 1.41 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 6.27 | 3 | 2.09 | 2.34 | 0.2144 |

| Pure Error | 3.57 | 4 | 0.8921 | ||

| Cor Total | 186.35 | 12 |

| Test Number | Soil Disturbance Coefficient Y1/% |

|---|---|

| 1 | 63.59 |

| 2 | 62.39 |

| 3 | 64.46 |

| 4 | 66.35 |

| 5 | 61.36 |

| Standard deviation | 1.92% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Shen, S.; Dong, W.; Abudu, S. Study on the Interaction Mechanism Between Sandy Soils and Soil Loosening Device in Xinjiang Cotton Fields Based on the Discrete Element Method. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2587. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242587

Li J, Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhang H, Shen S, Dong W, Abudu S. Study on the Interaction Mechanism Between Sandy Soils and Soil Loosening Device in Xinjiang Cotton Fields Based on the Discrete Element Method. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2587. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242587

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jinming, Jiaxi Zhang, Yichao Wang, Hu Zhang, Shilong Shen, Wenhao Dong, and Shalamu Abudu. 2025. "Study on the Interaction Mechanism Between Sandy Soils and Soil Loosening Device in Xinjiang Cotton Fields Based on the Discrete Element Method" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2587. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242587

APA StyleLi, J., Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., Shen, S., Dong, W., & Abudu, S. (2025). Study on the Interaction Mechanism Between Sandy Soils and Soil Loosening Device in Xinjiang Cotton Fields Based on the Discrete Element Method. Agriculture, 15(24), 2587. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242587