Abstract

Effective placement of liquid bioproducts in the root zone is essential for improving plant health and productivity in organic strawberry cultivation, yet subsurface application is often constrained by soil compaction typical of perennial production systems. This study evaluated the penetration behaviour of a fluorescent tracer solution applied using a newly developed subsurface applicator equipped with a disc coulter and integrated with an interrow cultivator. Field experiments were conducted on loamy sand prepared at three compaction levels: COMPACTED, NATURAL and LOOSE. Liquid distribution was assessed using UV fluorescence imaging and quantitative image analysis in ImageJ, enabling measurement of both penetration depth and cross-sectional wetted area. Soil physical properties including bulk density, porosity, hydraulic conductivity (permeability), water-holding capacity, and mechanical resistance were analyzed alongside liquid infiltration patterns. Results showed that soil compaction substantially limited both the depth and spread of the injected liquid, whereas loosening the soil prior to application significantly enhanced bioproduct placement within the target 15–20 cm root zone. Correlation analysis confirmed strong relationships between soil structure and liquid behaviour. The integrated loosening–application system demonstrates considerable potential for precise, efficient in-soil delivery of liquid bioproducts in organic strawberry production.

1. Introduction

Strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa), despite the increasing share of production under cover [1], are still commonly cultivated in open-field systems, particularly on small organic farms with limited investment potential. Organic farming is gaining ground among environmentally conscious consumers [2], and its share in the EU’s agricultural land is expected to reach at least 25% by 2030 according to the Farm to Fork (F2F) Strategy of the European Green Deal [3], which aims to make food systems healthy, and environmentally friendly [4]. The F2F Strategy also assumes a significant reduction in the dependency on pesticides and mineral fertilization to ensure that food production has a neutral or positive environmental impact [5]. This can be achieved, among other measures, by replacing or supplementing mineral fertilization with microbial biofertilizers or biostimulants [6,7,8].

In organic strawberry cropping systems, enhancing rhizosphere health by means of beneficial microbial inoculants containing plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) [9,10,11,12] and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) [13,14,15,16] has become an increasingly important strategy for sustainable production. However, successful deployment of such inoculants depends not only on their biological formulation but also critically on the delivery technology that ensures contact of the microbes with the plant root zone and prevents loss through surface exposure or displacement away from the roots.

In strawberry cultivation, the effective colonization of roots by beneficial microbes requires that the inoculant reaches the active root zone rather than remaining on or near the soil surface. Accordingly, the placement of the liquid biostimulant is key. Conventional broadcast or surface-applied methods may leave the inoculant too distant from the roots or subject to rapid loss through desiccation, surface runoff, microbial competition, temperature fluctuations, or UV exposure [17,18,19,20]. In contrast, subsurface application—placing the inoculant near or within the root zone—offers a more direct route to the rhizosphere, potentially improving microbial survival, colonization, and ultimately plant response [21].

Therefore, delivery systems capable of introducing a liquid inoculant into the soil at or close to root depth are of high interest. In the broader literature on fertilizer application, devices and methods for subsurface injection of liquids (nutrients or manure) have been shown to enhance nutrient-use efficiency and reduce losses [22,23,24]. Analogously, for microbial bioformulations, the principle of targeted delivery into the root zone applies. A liquid formulation providing a safe environment for microbial cells is considered an appropriate carrier, as it can accommodate viable and physiologically active cells [25].

Soil structural condition strongly constrains the fate of liquids introduced below the surface. Compaction reduces macroporosity and pore continuity, increases mechanical impedance, and promotes channelized flow through a limited number of preferential pathways, thereby reducing both lateral spreading and saturated hydraulic conductivity [26,27]. Experimental and modelling studies show that increases in bulk density and penetration resistance caused by traffic or consolidation shift pore-size distributions toward smaller and less connected pores and significantly reduce saturated and unsaturated hydraulic conductivity [28,29,30]. In contrast, restoration of structural continuity through loosening or reduced compaction improves pore connectivity and hydraulic conductivity, enabling deeper penetration and wider redistribution of injected liquids [26,28]. Studies on controlled subsurface delivery further demonstrate that soil texture and pore structure dominate spatial liquid distribution following injection, confirming the importance of soil physical conditions for subsurface application performance [23]. Together, these well-established soil physical mechanisms explain why, under realistic field conditions, soil condition frequently governs liquid placement outcomes more strongly than applicator geometry alone.

Yet relatively little has been published specifically on the mechanics of liquid inoculant penetration into soils of varying compaction or bulk density, and on how applicator design influences the distribution of liquid within the soil profile—particularly in the context of microbial rather than nutrient delivery. This gap invites a closer look at existing subsurface fertilizer applicators, their design parameters (opener type, coulter vs. probe vs. wheel injection), and their reported performance in liquid placement and soil penetration.

The mechanized delivery of liquid inputs into the subsurface has been studied in various contexts—primarily nutrient or fertilizer systems, manure injection, and precision-farming implements—and offers useful analogies for microbial inoculant delivery. McLaughlin et al. [31] made a review and tested various soil cultivation implements, such as wide and pointed sweeps, integrated with a fertilizer injector for subsurface applications. These tools are designed to disturb the topsoil layer, and when operated at greater depths, near the plants, they may also damage plant roots. Morrison & Chichester [32] described a rolling coulter that opened a slit in the soil and injected a stream of fertiliser solution into the furrow. Their results showed that coulter-based openers can successfully deliver liquids below the surface while limiting soil disturbance. Other types of subsurface devices include point-injection applicators. Rolling spike-wheel liquid injection systems were developed in the early 1980s as an improved method for applying fertilizer post-emergence [33,34]. Placing fertilizer in the root zone with these systems has been reported to improve N-uptake efficiency over broadcast methods in ridge-tillage corn [35], to maintain high N concentrations at lower rates for optimum early vegetative growth of sugar beet [36], or to increase nutrient-uptake efficiency and crop yield in iceberg lettuce [37]. Data also showed that spike wheels can be successfully used to deliver soil-applied pesticide formulations post-emergence in lettuce crops [38]. In sugar cane, da Silva et al. [22,39] evaluated a soil-punching probe that penetrated beneath the straw layer and provided nutrients near plant roots with minimal disturbance to roots and soil. This subsurface injection system allowed penetration of the liquid into deeper soil layers and minimized nutrient losses compared with surface broadcasting. Applying liquid microbial inoculum to seeds at sowing provides another effective mechanism for placing beneficial microorganisms into the soil, where they are well positioned to colonize seedling roots and protect against soil-borne diseases and pests [40,41]. All the methods mentioned above can also be used to apply liquid microbial inoculants. According to Khan [25], introducing these products subsurface via coulters, spike-wheel injectors, or soil-punching probes may maximize contact with roots and optimize efficacy.

Because bacteria and fungi exhibit a very limited range of dispersal in the soil matrix, these products should be placed as close as possible to the rhizosphere—a critical zone for plant–microbe interactions and nutrient exchange—to establish beneficial relationships of microbes with the strawberry root system [42]. Fungi are generally non-motile, meaning they cannot move independently, whereas most rod-shaped bacteria can move only locally using their own metabolic power through two mechanisms: swarming and swimming. However, on a macro scale, the mobility of bacteria and fungi in soil is limited unless their dispersal is driven by water or vectors (large-scale, passive movement) [43]. Thus, for effective colonization of the rhizosphere by microbial bioinoculants, large-scale passive movement is of greatest importance. In this case, soil moisture and porosity are crucial factors that mediate the movement of liquid carrier of microorganisms in the soil, determining that they have greater opportunities to develop and migrate in loosened, porous soil with higher water content [43]. Therefore, the liquid carrier of microorganisms, unlike liquid mineral fertilizers, should be applied at a relatively high volume to ensure their widest possible dispersal in the soil. Among the described subsurface applicators operating with limited soil and plant root disturbance this condition can best be met with the device based on rolling coulter.

Strawberry plants are shallow-rooted. The root system may reach a depth of up to 30–40 cm in sandy soils; however, most roots occupy the top 20 cm of soil, which is also the depth from which root samples are typically collected for analyses of root growth [44]. This also applies to studies on the effects of microbial inoculants on strawberry productivity, in which roots were sampled from the 5–15 cm layer [45]. Thus, the main root mass of interest is concentrated within the upper 20 cm of soil, and this is the zone where microbiological inoculants should be delivered to ensure optimal colonization of the rhizosphere.

The objective of the work described in this paper was to develop a simple, low-cost soil applicator for subsurface placement of liquid microbial inoculants in perennial crops like strawberries and to evaluate its performance in terms of liquid penetration in soils of different compaction levels under typical field conditions found in organic strawberry cultivation rather than to develop a mechanistic soil–tool interaction model. Although motivated by the increasing use of microbial bioproducts, the present study primarily addresses the engineering and soil-physical aspects of subsurface liquid placement. The intention was not to model microbial processes, but to evaluate the capacity of a simple applicator to deliver liquid effectively under realistic soil mechanical conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at the National Institute of Horticultural Research, Skierniewice, Poland. The development of the subsurface applicator for bioproducts was carried out at the Department of AgroEngineering, physical analyses of soil properties were performed at the Department of Plant Cultivation and Fertilization, and field experiments were conducted at the Institute’s Experimental Fields (51°57′58″ N, 20°10′35″ E).

All soil preparation treatments, product applications, soil measurements (including soil compaction and sample collection for property assessment), and observations of application effects were conducted under identical environmental conditions within a single day, thereby minimizing moisture-related variability among compaction treatments. The experiment was performed in undisturbed field soil with natural structure rather than in artificially reconstructed soil, ensuring realistic mechanical behaviour representative of commercial strawberry production conditions.

2.1. Subsurface Applicator

Design requirements for the subsurface applicator of microbiological inoculants were established based on a literature review and agronomic conditions associated with organic strawberry cultivation. The applicator was expected to:

- (1)

- deliver high liquid volumes (at least 1500 L·ha−1),

- (2)

- ensure an application depth of approximately 15 cm, enabling product penetration down to 20 cm in the soil,

- (3)

- minimize soil and root disturbance, and

- (4)

- allow use with both liquid and granular products (e.g., microbiologically enriched biofertilizers) via an appropriate metering system.

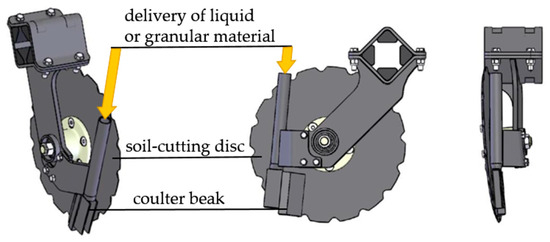

Considering its intended use on small, family-owned organic farms with limited investment potential, the design emphasized simplicity, low cost, and ease of maintenance. Therefore the applicator employs heavy disc coulters from a Fenix-G grass seed drill (Unia Sp. z o.o., Grudziądz, Poland) integrating the soil-cutting disc with a coulter that introduces either liquid or granular material into the soil (Figure 1). The robust structure of the coulters allows cutting through crusted or compacted soil layers typically found in interrows of perennial crops such as strawberries and introducing the bioproduct below the surface without depositing it on top of the soil. The furrow formed behind the coulter is very narrow (approximately 3 cm) and does not require closure by an additional device, ensuring minimal soil disturbance and structural simplicity.

Figure 1.

Disc coulter of the subsurface application of liquid or granular products.

Design parameters of the coulter were selected to reflect commercially available coulter units and agronomically relevant application depth for strawberry roots. The intention was not to optimize geometry but to test whether an existing simple solution can achieve functional subsurface placement.

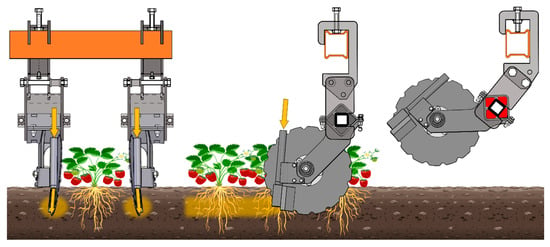

The set of two coulters operating on both sides of the plant row were mounted on the frame of a tractor-mounted inter-row cultivator (1.8 m wide two-row implement) equipped with 20 cm-wide goosefoot shares (Figure 2). This integration was intended to utilize the carrier system of an existing machine, thereby reducing costs and enabling the combined operation of both devices. Such a configuration made it possible to loosen compacted soil in the strawberry interrows immediately before applying liquid microbiological inoculants. The coulter mounting system on the cultivator frame allowed adjustment of spacing, working depth, and transport position, thus enabling cultivator operation without the applicator. When the applicator was positioned for operation and the goosefoot shares were raised, the system allowed liquid application without disturbing the soil surface.

Figure 2.

Subsurface disc coulter applicators in operating and transport positions.

For experimental purposes, the liquid delivery system of the applicator was developed using a set of three compression sprayers with 20 L tanks, supplied with compressed air at 1 MPa from a pressure cylinder containing air at 12 MPa. The liquid from each sprayer tank was delivered to the coulters through throttling orifices, which, in combination with outlet pressure adjustment, enabled precise control of the liquid flow rate.

2.2. Preparation of the Experimental Site

The subsurface applicator was developed for use in traditional, open-field, organic strawberry cultivation, which is a perennial row crop system without annual deep tillage. Such systems are prone to natural soil compaction over time, and the interrow zones experience additional, traffic-induced compaction due to repeated tractor passes. Because the objective of this study was to examine the interaction between the applicator and soils of different compaction levels—specifically the effect of compaction on the penetration of liquid products—the experiment was intentionally conducted on bare soil without plants. The presence of plants would have introduced additional, uncontrolled variation related to root architecture, soil disturbance by roots, and heterogeneous moisture distribution, making it difficult to isolate the soil–applicator interaction.

For this reason, a field with bare, levelled soil was selected. After the winter period, in early spring on the day of the experiment (17 April 2025), no weeds had yet emerged and no spring tillage operations had been conducted. The field was part of a four-year crop rotation and had previously been cultivated with wheat.

Three plots (1.8 m wide and 30 m long) with different soil compaction levels were prepared to conduct the test with the developed applicator for liquid material injection. The soil compaction states were defined and prepared as follows:

- NATURAL—soil cultivated in autumn and left to settle naturally over winter, representing the initial soil compaction.

- LOOSE—soil naturally settled after winter and then loosened using a goosefoot cultivator (20 cm share width) operating at a depth of approximately 15 cm.

- COMPACTED—soil naturally settled after winter and then compacted by repeated tractor wheel passes made in close proximity to each other.

Following the application of the liquid product using the subsurface applicator, as described in the next section, the following experimental operations were conducted on each plot representing the soil compaction levels described above, as detailed in Section 2.3, Section 2.4 and Section 2.5, respectively: (i) assessment of the penetration of the applied product on soil cross-sections at five randomly selected locations (5 replicates); (ii) measurement of soil resistance using a cone penetrometer at two points adjacent to each of the five soil cross-sections (10 replicates); and (iii) collection of soil samples in the immediate vicinity of each of the five soil cross-sections (5 replicates) to determine soil physical properties. Thus, this study, consisting of 3 treatments (experimental plots physically established under defined soil compaction levels) and 5 or10 independent replications per treatment (observations taken at spatially independent, randomly selected locations within each plot), represents a classic balanced one-factor experimental design suitable for one-way ANOVA.

2.3. Soil Application of Liquid Material

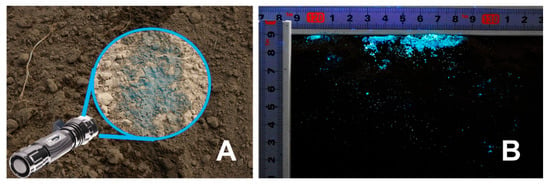

Following the preparation of experimental plots with different soil compaction levels, the liquid material in form of 2% aqueous solution of fluorescent tracer UView (METOS by PESSL Instruments, Weiz, Austria) was applied using two alternative application methods (Figure 3): (1) on-surface application with a high-flow, narrow-angle TeeJet nozzle TPU #60JET SS 4060 (Spraying Systems Co., Wheaton, IL, USA) discharging the liquid onto the soil surface from a height of approximately 15 cm and thereby wetting a narrow strip of soil approximately 10 cm wide, and (2) subsurface application using the developed coulter-based applicator.

Figure 3.

Application of UV tracer performed by two methods: (A) on-surface application with high-flow nozzles TeeJet TPU #60JET (in circles); (B) subsurface application with disc coulters.

Both applicators were attached to the frame of a tractor-mounted inter-row cultivator and supplied from a common liquid delivery system operating at 0.6 MPa (Figure 4). To ensure an identical flow rate (6.75 L·min−1) for both methods, an orifice disc with a 3 mm hole was installed in the hose coupling feeding the subsurface applicator. Consequently, an equal application rate of 1500 L·ha−1 was achieved at a travel speed of 6 km·h−1, assuming two nozzles or two coulters per strawberry row (row spacing 0.9 m).

Figure 4.

Compression tanks of the applicators’ liquid supply system mounted on interrow cultivator.

The fluorescent tracer was used as a conservative physical proxy for liquid movement only. It does not replicate microbial aggregation, rheology, or biological interaction with soil. Therefore, conclusions relate strictly to liquid placement and infiltration, not to microbial survival or colonization.

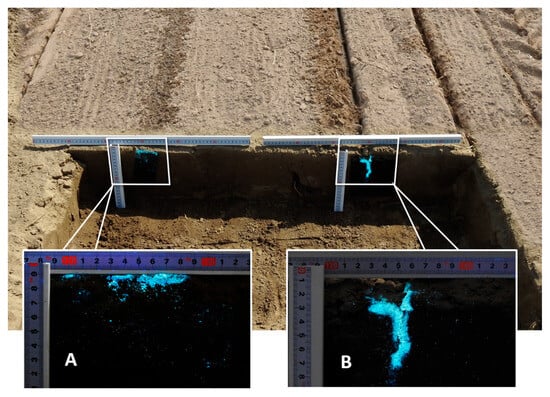

Following application, the liquid was allowed to infiltrate and disperse in the soil for 15 min. Thereafter, five soil cross-sections (depth 20 cm) per plot and per method were prepared to assess liquid penetration using UV imaging of the fluorescent tracer (Figure 5). Images were captured under a black tent to ensure darkness, while the soil cross-sections were illuminated with a 365 nm UV light source (Alonefire torch; 3 × LED, 36 W; Shenzhen Shiwang Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China).

Figure 5.

Soil cross-section with scale to take UV images of fluorescent tracer penetrating the soil profile (experimental plot of COMPACTED soil): (A) on-surface application with high-flow nozzle TeeJet TPU #60JET; (B) subsurface application with disc coulter.

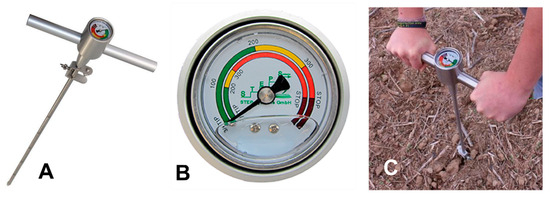

2.4. Soil Compaction Measurement

Soil compaction was measured in two locations adjacent to each of the five soil profile sections per plot, resulting in ten measurements for each of the three plots representing different soil compaction levels, taken near the sites of liquid penetration assessment.

The measurements were performed according to the ASABE Standard S313.3 [46] using a portable manual cone penetrometer (Soil Compaction Tester, STEP Systems GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany) (Figure 6) that provides a qualitative estimation of soil firmness by measuring the mechanical resistance of the soil to cone penetration. The instrument consisted of a graduated steel rod with a 13 mm conical tip and an analog pressure gauge displaying penetration resistance as pressure expressed in pounds per square inch (PSI), convertible to MPa. During measurement, the probe was manually inserted into the soil to a maximum depth of 50 cm, and readings were recorded at 5 cm intervals corresponding to the marked graduations on the rod.

Figure 6.

Cone penetrometer used for measurements of soil resistance (MPa) representing soil compactness: (A) general view; (B) analogue pressure gauge identifying soil resistance; (C) manual pushing the penetrator rod into soil.

This method provides a reliable field-based indication of relative soil compaction and strength and is widely used in soil physical studies [47].

2.5. Determination of Soil Physical Properties

Soil samples were collected adjacent to each of the five soil profile sections (5 replicates) within each of the three plots representing the tested compaction conditions, in order to determine the soil physical properties most strongly affected by soil compaction: bulk density, porosity, and field water capacity. Samples were taken from the arable layer at a depth of 15 cm using standard metal cylinders with a diameter of 5 cm and a height of 5 cm. Soil from the NATURAL plot was additionally used to determine soil properties assumed to be representative of all plots, including granulometry, organic matter content, organic carbon content, pH, and moisture at the time of application.

The undisturbed samples were placed in a sand apparatus (Eijkelkamp, Giesbeek, The Netherlands), saturated with water, and then subjected to a suction level of −3.2 cm H2O, corresponding to field water capacity. After completion of the measurements in the sand apparatus, the samples were dried at 105 °C.

Porosity, bulk density, and water content were calculated according to the equations provided in the standard PN-EN 13041:2011 [48]. Organic matter (OM, %) content was determined after ignition of the samples using the method described in the standard PN-EN 13039:2011 [49], and organic carbon (OC, %) content was calculated using the conversion factor according to Equation (1) [50]:

Undisturbed soil samples for determining soil permeability were collected in metal rings with a diameter of 5.7 cm and a length of 6.0 cm. Permeability was measured using an automatic laboratory permeameter Chameleon 2816G1/G5 (Soilmoisture Equipment Corp., Santa Barbara, CA, USA), which determines the saturated hydraulic conductivity (KSAT, mm·min−1), a measure of the rate at which water moves through the soil [51]. It was calculated according to Equation (2) [52]:

where

Ac—reservoir cross-sectional area (calculated from the reservoir inside diameter D = 51.3 mm),

As—sample cross-sectional area (calculated from the sample ring inside diameter d = 53.8 mm),

L—sample length (length of sample ring L = 60.0 mm),

b—coefficient of the fitted exponential function describing the decrease of overhead pressure H (water height) over time t: H = A·ebt.

2.6. Evaluation of UV Images

Following the acquisition of photographic documentation of soil cross-sections during the field experiments, UV image analysis was conducted to assess the extent of liquid penetration and spread within soils of different compaction levels. A preliminary examination of UV images showed that on-surface application did not allow assessment of liquid penetration into the soil profile. During this application, with the nozzle flow rate 6.75 L·min−1, resulting in 10 cm wetting swath, soil aggregates were only slightly moistened, corresponding to approximately 0.7 mm of rainfall (0.675 L·m−2), which prevented visible infiltration (Figure 7). Consequently, only images obtained from subsurface application were analyzed, where a distinct and continuous trace of soil moistened by UV tracer was observed despite the low application rate (0.0675 L·m−1 along the coulter path).

Figure 7.

UV image of on-surface applied fluorescent tracer slightly wetting the outer soil particles: (A) UV illuminated top view of soil surface in ambient light; (B) UV illuminated soil cross-section under darkness.

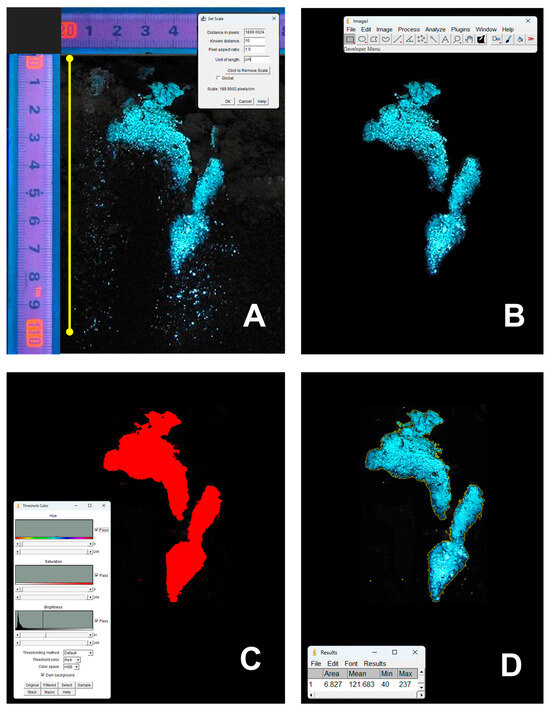

Image preparation for analysis consisted of cropping the region of interest using Microsoft Photos application (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The images were then processed in the open-source software ImageJ 1.54r, a Java-based image processing program developed in the public domain by the National Institutes of Health and the Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA) [53]. The analysis included the following steps (Figure 8A–D):

Figure 8.

Steps of UV image analysis performed using the ImageJ application: (A) scale setting on raw image; (B) retouching: manual removal of artifacts; (C) object segmentation based on manual thresholding; (D) determining area of the segmented (fluorescent) object.

- (i)

- scale setting—spatial calibration of each image using a known scale visible in the photo;

- (ii)

- retouching—manual removal of small “drifting artifacts,” i.e., fluorescent soil particles displaced from the wet region during cross-section preparation;

- (iii)

- object segmentation—separation of fluorescent areas from the background by applying manual thresholding to distinguish foreground objects (fluorescent liquid) from the background;

- (iv)

- area calculation—determination of the area of segmented objects based on the number of foreground pixels converted to physical units (cm2) using the calibrated scale.

In addition to measuring the area of the wetted zone, image calibration also enabled the measurement of the maximum depth of subsurface liquid penetration in soils of different compaction levels. Both parameters were used to evaluate the extent of liquid penetration and spread within the soil profile.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data were statistically analyzed by software STATISTICA 13.3 (StatSoft Polska Sp. z o.o., Kraków, Poland). The analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of p < 0.05 was performed to separate means and detect significant differences. For each tested effect, within each soil compaction treatment, five or ten measurements were taken at spatially independent locations in the field. These locations served as true experimental replicates, ensuring independence of observations and validating the use of one-way ANOVA for treatment comparisons.

A series of correlation analyses were performed to construct a correlation matrix using the Pearson correlation coefficients (r ∈ [−1, 1]) to determine the strength and direction of linear relationships between the tested variables, and the corresponding p-values were calculated to assess the statistical significance of the correlations at the 5% significance level.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Compaction

Based on the granulometric composition of the collected and analyzed soil samples, the topsoil at the experimental site was classified as loamy sand according to the Soil Science Society of Poland (SSSP). It contained 18% silt, 6% clay, and 76% sand. The organic matter and organic carbon contents, analyzed according to the standard PN-EN 13039:2011 [49], were 1.86% and 1.04%, respectively. The soil pH was 6.4, and the moisture content on the day of application was 7.78%.

Among the experimental plots, only the one designated as NATURAL represented soil in its undisturbed condition after the winter period. On the remaining two plots, soil was either compacted (COMPACTED) or loosened (LOOSE) to obtain three distinct compaction levels.

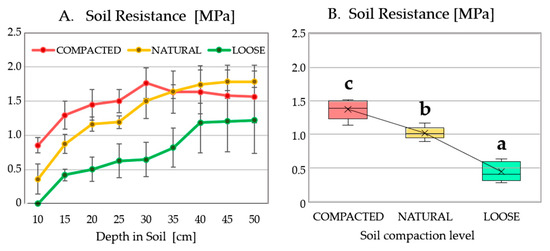

Soil resistance measured with the cone penetrometer clearly differentiated these levels (Figure 9A). In the COMPACTED plot, penetration resistance increased sharply with depth and consistently exceeded the values recorded for the NATURAL and LOOSE plots. NATURAL soil showed intermediate resistance, whereas LOOSE soil displayed the lowest and most uniform resistance profile throughout the 10–30 cm depth range.

Figure 9.

Soil resistance (MPa) on three experimental plots with compaction levels defined as COMPACTED, NATURAL, and LOOSE: (A) mean values with standard deviation bars of soil resistance measured using a manual cone penetrometer (13 mm cone tip) to a depth of 50 cm; (B) mean values based on records taken every 5 cm from 10 to 30 cm soil depth. Means labelled by the same letter do not differ significantly according to Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Mean resistance values differed significantly among all treatments (p < 0.05), confirming that the field preparation successfully established distinct soil mechanical conditions for evaluating liquid penetration (Figure 9B).

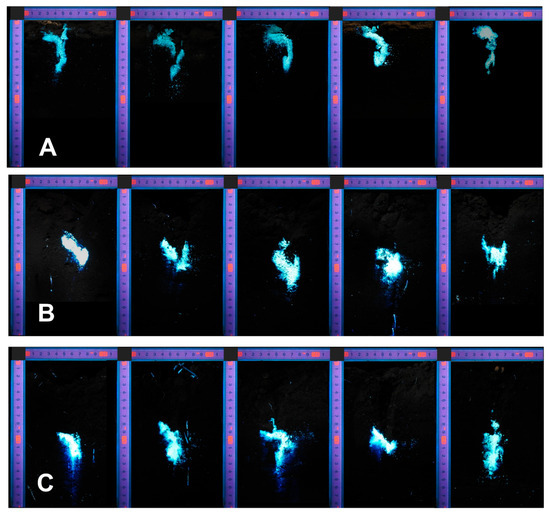

3.2. Penetration of Liquid Product in Soil

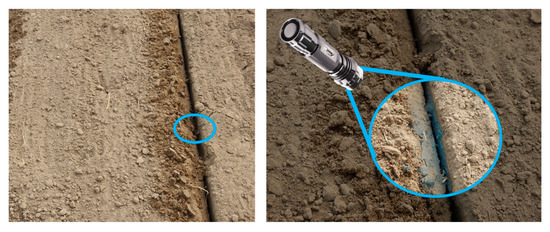

UV imaging revealed clear differences in the behaviour of the subsurface-applied liquid tracer among the compaction levels (Figure 10). In COMPACTED soil (Figure 10A), the liquid remained confined to a shallow and narrow zone directly beneath the coulter slit, with very limited lateral or vertical dispersion. The fluorescent signal was visible from the soil surface down to the coulter operating depth. Due to the high firmness of this soil, the furrow was not fully closed, leaving part of the liquid deposit exposed near the upper edge of the slit (Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Images of soil cross-sections illuminated under UV light after subsurface application of a UV tracer aqueous solution to soils of different compaction levels: (A) COMPACTED; (B) NATURAL; (C) LOOSE. Image analysis performed using the ImageJ application was used to determine the depth of soil penetration and the cross-sectional area of liquid distribution within the soil profile.

Figure 11.

On COMPACTED soil the furrow made by the disc coulter applicator was not fully closed, leaving part of the liquid deposit, near the upper edge of the narrow slit, exposed and seen when illuminated by UV light.

In NATURAL soil (Figure 10B), penetration depth and spreading area were greater, resulting in a wider wetted pattern. The furrow was fully closed several centimetres above the wetted zone, indicating more favourable soil deformability.

In LOOSE soil (Figure 10C), the wetted zone was the widest and penetrated deepest into the profile, reflecting low mechanical impedance, high pore continuity, and greater soil displacement caused by the coulter. This facilitated both lateral spreading and vertical descent of the liquid.

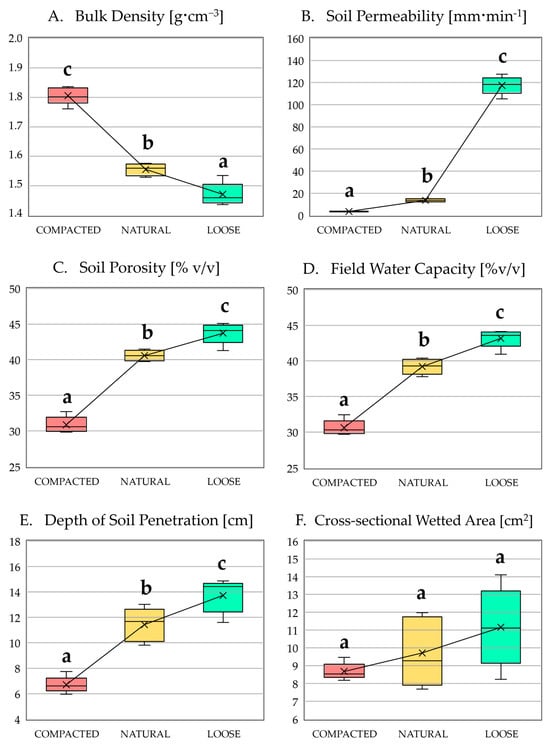

3.3. Soil Properties as Affected by Soil Compaction

The three compaction treatments differed markedly in physical soil properties (Figure 12). Bulk density was highest in the COMPACTED soil, intermediate in the NATURAL treatment, and lowest in the LOOSE soil (Figure 12A).

Figure 12.

Soil properties: (A) bulk density, (B) permeability (saturated hydraulic conductivity KSAT), (C) porosity, and (D) field water capacity, as well as the effects of subsurface application of a liquid product: (E) depth of penetration and (F) cross-sectional wetted area identified in soils with different compaction levels defined as COMPACTED, NATURAL, and LOOSE. Means labelled by the same letter do not differ significantly according to Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Permeability, represented by saturated hydraulic conductivity (KSAT) showed the opposite trend (Figure 12B). This pattern corresponded well with soil porosity (Figure 12C), which decreased with compaction.

Unexpectedly, field water capacity (Figure 12D) also decreased with increasing compaction, which may reflect aggregate destruction and blockage of water-holding micropores. All soil property differences among treatments were statistically significant.

The physical soil properties explained the observed behaviour of the subsurface-applied liquid. The coulter penetrated deepest into the LOOSE soil, where low bulk density and high porosity allowed greater tool immersion and larger void spaces facilitated fluid movement. In contrast, COMPACTED soil, with reduced deformability and high mechanical resistance, restricted tool penetration, causing shallower liquid placement. Accordingly, penetration depth was greatest in LOOSE soil and lowest in COMPACTED soil, with all differences statistically significant (Figure 12E). This demonstrates a strong dependence of application depth on soil compaction level, consistent with soil resistance measurements (Figure 9).

A similar pattern was observed for the wetted cross-sectional area (Figure 12F), although in this case the effect was expressed only as a trend. The lack of statistical significance resulted primarily from the high variability of values in NATURAL and LOOSE soils, which was markedly greater than in COMPACTED soil. In compacted soil, the subsurface applicator produced a narrower and more stable slit with limited soil displacement, resulting in more consistent wetted areas.

In contrast, when the coulter moves through loose soil, it interacts with a weakly consolidated matrix rich in macropores and easily deformable aggregates. This leads to irregular and highly variable soil displacement, causing the injected liquid to spread more randomly. Although the wetted area was generally larger in loose soil than in compacted soil, the variability was too high for the differences to reach statistical significance.

These results demonstrate that the performance of the coulter-based subsurface application system is highly sensitive to soil mechanical conditions: bulk density, pore structure, and hydraulic conductivity strongly influence the depth of liquid placement and the spatial pattern of its dispersion.

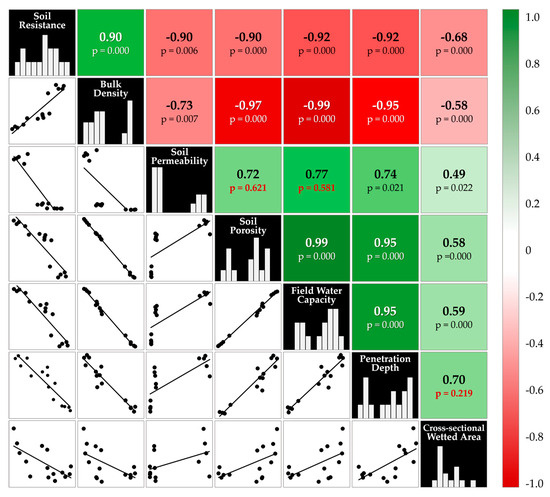

3.4. Relationships Between Tested Variables–Correlation Matrix

To better understand how soil physical properties jointly influence the behaviour of subsurface-applied liquid, a correlation matrix was constructed (Figure 13). In the presented correlation matrix, the lower triangle displays scatterplots for each pair of variables, the diagonal shows histograms of individual variables, and the upper triangle presents a heatmap with a colour gradient representing the strength and direction of correlations, with green indicating positive correlations and red indicating negative correlations. The strength of each relationship is expressed numerically by the Pearson correlation coefficient (r ∈ [−1, 1]), accompanied by the corresponding p-value indicating the statistical significance of the correlation (p > 0.05 denotes a non-significant relationship at the 5% level).

Figure 13.

Correlation matrix showing relationships among the measured variables. The lower triangle displays scatterplots for each pair of variables, the diagonal shows histograms of individual variables, and the upper triangle presents a heat map with Pearson correlation coefficients (r ∈ [−1, 1]) accompanied by the corresponding p-values indicating the statistical significance of each relationship at the 5% level. Variables included in the matrix are: soil resistance (MPa), bulk density (g·cm−3), soil permeability (saturated hydraulic conductivity KSAT; mm·min−1), soil porosity (% v/v), field water capacity (% v/v), liquid penetration depth (cm), and cross-sectional wetted area (cm2).

The correlation matrix showed strong and consistent relationships among the measured soil physical parameters modified by the level of soil compaction and indicators of the fate of liquid in soil. Penetration depth was very strongly and positively correlated with soil porosity and field water capacity, and very strongly negatively correlated with bulk density and soil resistance. These patterns indicate that mechanical loosening and aeration of soil through tillage, which increase porosity, reduce bulk density, and lower mechanical resistance, facilitate deeper placement of the subsurface-applied liquid.

Cross-sectional wetted area showed moderate positive correlations with porosity and field water capacity and a moderate negative correlation with bulk density and penetration resistance. Its correlation with penetration depth was also moderate but did not reach statistical significance, likely due to the high variability of wetted area in NATURAL and LOOSE soils observed earlier (Figure 12F). Thus, the data do not support a significant association between the depth of liquid injection and the extent of its lateral spreading in the soil.

Soil compaction-related variables -bulk density and penetration resistance, strongly positively correlated themselves—were very strongly negatively correlated with porosity, hydraulic conductivity (permeability), and field water capacity, confirming the expected structural and hydraulic consequences of soil compaction. Their correlations with liquid penetration depth were also strong and negative. Correlation with wetted area was also negative but considerably weaker reflecting the variable and irregular spreading patterns created by the coulter in loose soils.

Altogether, these correlations confirm that the extent of liquid penetration following subsurface application is primarily governed by soil structural attributes depending on soil compaction level. The results highlight that mechanical soil conditions, especially density, porosity, and resistance, are critical determinants of the effective spatial distribution of liquid products such as microbial inoculants, particularly in coarse-textured soils like the loamy sand tested in this study.

4. Discussion

The present study evaluated the penetration behaviour of a liquid bioproduct applied into soil using an innovative subsurface applicator integrated with a disc-coulter and an interrow loosening cultivator designed for organic strawberry cultivation. The discussion of the obtained results is framed in the context of the increasing importance of microbial and biologically active products in environmentally sustainable horticultural production systems, the challenges posed by subsurface application of liquids into compacted soils typical of perennial crops, and the methodological and technological innovations developed in this research.

4.1. Relevance of Bioproduct Application in Organic Strawberry Cultivation

Organic strawberry production relies extensively on biological products such as microbial inoculants, biostimulants, and organic fertilizers that support plant health without reliance on synthetic chemicals. Many of these materials act most effectively when placed in the root zone, where microbial interactions, nutrient cycling, and root colonization are most active [54,55]. Their performance therefore depends not only on the product itself but also on the method of delivering it to the biologically active part of the soil profile. The ability to place such products below the soil surface while avoiding root damage is especially important in strawberry cultivation, where a large proportion of the root system is concentrated in the upper soil layers (commonly within ~15–20 cm) depending on soil type and management. The present research addressed this challenge by developing equipment capable of precise, minimally intrusive subsurface application.

The selected soil type—loamy sand—represents one of the most common soils used for commercial strawberry production in Central and Eastern Europe. Its relatively low organic matter content and coarse texture make it prone to compaction, particularly in perennial plantations subjected to repeated machinery traffic. Conducting the experiment on loamy sand therefore reflects realistic agronomic conditions and increases the practical relevance of the outcomes [26].

4.2. Challenges of Subsurface Liquid Application in Compacted Soils

Perennial strawberry plantings accumulate traffic-induced compaction over time. Compacted soils exhibit reduced total porosity, loss of macropores, high mechanical impedance, and diminished hydraulic conductivity [26]. Numerous studies have shown that elevated penetration resistance restricts root elongation and creates challenges for soil-engaging tools [56]. Under these conditions, subsurface applicators face difficulty creating slots that allow the injected liquid to disperse adequately, and instead the fluid tends to follow narrow channels with limited lateral migration.

The present results confirm this pattern. In the COMPACTED soil, the injected liquid remained confined to a shallow and narrow area directly beneath the coulter track. Limited spreading is consistent with the measured reduction in porosity and hydraulic conductivity and the sharp increase in mechanical resistance. Importantly, this suggests that even when mechanical settings prescribe a particular injection depth, the soil itself may prevent the implement from reaching the intended depth or from generating adequate space for dispersion [46,47].

From a soil physics perspective, the restricted penetration observed in COMPACTED soil is consistent with reduced macroporosity, disrupted pore connectivity, and elevated mechanical impedance, all of which limit both tool insertion depth and hydraulic flow paths. In compacted soil, water movement occurs mainly through a reduced number of small and poorly connected pores, causing injected liquid to remain concentrated near the injection point rather than dispersing freely. This highlights that the success of subsurface application depends not only on equipment settings, but fundamentally on soil structural condition.

4.3. Innovation of the Subsurface Applicator Integrated with a Loosening Cultivator

To overcome these limitations, the applicator was designed as an integrated system combining a disc coulter with a shallow interrow loosening cultivator. Pre-loosening the soil reduces bulk density and mechanical impedance, increases pore continuity, and reintroduces air-filled macropores [26], thereby improving the soil’s capacity to accept injected liquids. Such integrated systems have been proposed in the context of fertilizer banding and manure injection, but have not previously been systematically evaluated for organic strawberry cultivation and the delivery of microbial bioproducts.

The results of this study strongly support the benefits of this design. In the LOOSE soil—representing conditions created by the cultivator—the liquid penetrated significantly deeper and spread more widely compared with NATURAL and COMPACTED soil. Most notably, the applicator was able to reliably deliver the liquid into the 15–20 cm rooting zone of the strawberry crop without causing root damage, which is a key agronomic requirement and the depth where effective rhizosphere colonization is desired. This depth corresponded closely to the soil volume loosened by the cultivator, demonstrating that the combined action of loosening plus injection in a single pass offers a highly effective strategy. The observation that combined tillage + application produced the best placement is thus supported by the present data and aligns with agronomic expectations for shallow-rooted perennial crops [26,56].

This finding has important practical implications. If soil is compacted, performing subsurface application without prior loosening may yield poor coverage within the root zone. In contrast, performing a loosening operation immediately before injection clearly enhances the placement of the liquid and improves its distribution within the soil matrix. The integrated equipment allows for both operations to be carried out simultaneously, reducing energy costs and minimizing soil disturbance—an important principle of sustainable and organic agriculture.

The beneficial effect of soil loosening can therefore be interpreted as both mechanical and hydraulic: mechanically, reduced resistance allows deeper tool insertion. Hydraulically, increased pore volume and pore continuity promote liquid redistribution. While no mechanistic model is developed in this study, the observed response pattern is consistent with established concepts of water flow in porous media, where infiltration and lateral spreading increase with porosity and hydraulic conductivity. The results thus demonstrate that soil condition, rather than applicator geometry alone, is the primary determinant of in-soil liquid behaviour under practical operating conditions.

4.4. Innovation of the Assessment Method: UV-Based Image Analysis

A methodological advancement of this research is the use of UV fluorescence imaging, combined with systematic image analysis in ImageJ, to quantify the depth and cross-sectional area of liquid penetration. Traditional tracer methods (dyes) and visual scoring are useful but often lack the quantitative reproducibility required for detailed comparison. UV fluorescent tracers provide high-contrast localisation under controlled illumination, and ImageJ [57] offers robust, well-documented tools for segmentation, thresholding and area quantification. Similar image-based approaches have been applied successfully to dye-stained soil profiles to characterize preferential flow and wetted area [58]. In our case, the workflow (cropping, artifact removal, manual threshold segmentation, pixel-to-area conversion) produced objective data suitable for statistical processing and for inclusion in the correlation matrix.

4.5. Interpretation of Soil Properties in Relation to Liquid Penetration

The contrasting soil properties among the three soil treatments explain the observed differences in liquid penetration. In LOOSE soil, lower bulk density and higher porosity facilitated deeper tool penetration and enhanced fluid movement. These structural improvements also increased saturated hydraulic conductivity, providing pathways for more extensive lateral wetting. Such effects are consistent with established knowledge that macropores and structural voids dominate water flow in coarse-textured soils [27].

The image analysis workflow applied to UV images produced consistent segmentation of the fluorescent traces. Quantification showed that both penetration depth and wetted area decreased with increasing soil compaction, confirming that reduced macroporosity and higher mechanical resistance limit liquid movement following subsurface application.

In compacted soil, limited porosity and high mechanical impedance restricted flow, resulting in shallow and narrow wetted patterns. Interestingly, the wetted cross-sectional area exhibited greater variability in NATURAL and LOOSE soils, while values in COMPACTED soil remained relatively uniform. This pattern can be explained by the different modes of soil deformation induced by the coulter. In compacted soil, displacement is constrained and follows predictable rupture planes, resulting in a narrower and more stable slit. In loose soil, the coulter displaces soil more irregularly, redistributing aggregates in a random fashion and creating non-uniform pore spaces. This heterogeneity contributes to the high variability of wetted areas observed in the more porous soil treatments.

4.6. Role of the Correlation Matrix in Identifying Key Relationships

Correlation matrices are widely recognized as powerful tools for examining multivariate patterns, offering a compact yet information-rich view of how multiple variables interact within a system. Their ability to highlight dominant associations and reveal structural relationships makes them particularly useful for interpreting complex experimental datasets [59,60].

The correlation matrix provided integrative insight into the relationships among soil physical properties and liquid penetration behaviour. As expected, penetration depth was strongly positively correlated with porosity and negatively correlated with bulk density and soil resistance. These relationships confirm that soil structural properties govern the ability of the tool to reach the planted depth and the ability of the liquid to move through the pore network.

The wetted cross-sectional area showed more moderate correlations with soil properties, and its lack of significant correlation with penetration depth reflects the inherently variable nature of liquid spreading in loosely structured soil. The correlation analysis thus offered a comprehensive interpretation of the experimental results, reinforcing the conclusion that mechanical soil conditions are the dominant factor influencing the effectiveness of subsurface liquid application.

4.7. Practical Implications for Organic Strawberry Management

Taken together, the results show that soil physical conditions play a decisive role in determining the success of subsurface liquid applications. A key practical outcome is that the best placement of the bioproduct—into the 15–20 cm root zone without damaging the roots—is achieved when application is performed simultaneously with soil loosening using the cultivator. This ensures adequate penetration depth and favourable spreading conditions.

This target depth is consistent with strawberry root architecture—most absorbing roots are concentrated within the upper 10–20 cm—and with agronomic evidence that deep placement in the root zone (≈15–20 cm) improves nutrient/bioproduct uptake and placement efficiency compared with surface application [61,62].

The innovative applicator therefore offers a promising solution for organic strawberry systems, enabling precise placement, improved efficiency of bioproducts, and reduced operational costs through combined tillage and application.

4.8. Limitations of the Study

This study was designed as a practical performance assessment, and several limitations should be acknowledged. Only one soil type (loamy sand) was tested, which limits direct extrapolation to heavier soils. Compaction levels were created by mechanical means and quantified via penetration resistance and bulk density, but were not defined by standardized traffic loads. The tracer solution represents liquid movement only and does not simulate the biological behaviour, rheology, or survival dynamics of real microbial formulations. Finally, biological effectiveness and root colonization were not evaluated. As a result, the findings should be interpreted as describing liquid placement performance, not biological efficacy.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that soil compaction has a profound impact on the penetration depth and spreading behaviour of subsurface-applied liquid bioproducts in loamy sand soils commonly used for organic strawberry cultivation. Mechanical loosening prior to application significantly improved both parameters.

The integrated disc-coulter applicator combined with a loosening cultivator proved capable of reliably delivering the liquid into the strawberry rooting zone (15–20 cm) with minimum risk of causing root injury, thereby meeting one of the key agronomic requirements for effective bioproduct delivery. This integrated operation resulted in deeper placement and greater wetted area, confirming that soil structural conditions are essential for successful application.

The use of UV fluorescence imaging and quantitative image analysis provided an accurate and reproducible assessment of liquid distribution, while correlation analysis confirmed strong relationships between soil structure and application outcomes.

Overall, combined tillage and subsurface application in a single pass emerges as an efficient, innovative, and agronomically beneficial approach for improving the performance of liquid bioproducts in organic strawberry production.

Future work should focus on systematic studies generating datasets that enable the development of coupled soil–fluid–equipment interaction models, optimization of application parameters through mechanistic or simulation-based approaches, and evaluation of microbial survival and colonization following subsurface application. In addition, future research should examine the real-world effects of subsurface-applied bioproducts, such as microbial inoculants or microbially enriched fertilizers, particularly with respect to their potential to accelerate rhizosphere colonization, improve plant growth, and enhance plant health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.; methodology, G.D.; formal analysis, G.D., J.S.N. and W.Ś.; investigation, G.D., W.Ś. and J.S.N.; resources, G.D.; data curation, G.D., W.Ś. and J.S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D. and J.S.N.; review and editing, G.D., R.H. and A.G.; visualization, G.D.; supervision, G.D.; project administration, G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The European Union and Narodowe Centrum Badań i Rozwoju, Poland (The National Centre for Research and Development), grant number: CORE Organic/III/55/ResBerry/2022 (Project: ResBerry—Resilient organic berry cropping systems through enhanced biodiversity and innovative management strategies).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Waldemar Treder for introducing us to the ImageJ application, as well as the technicians from the Department of Agroengineering and the Department of Plant Cultivation and Fertilization for their professional commitment to the applicator’s development and their contributions to the field and laboratory experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Menzel, C.M. A review of strawberry under protected cultivation: Yields are higher under tunnels than in the open field. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 100, 286–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraboina, R.; Cooper, O.; Amini, M. Segmentation of organic food consumers: A revelation of purchase factors in organic food markets. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103710, ISSN 0969-6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. COM(2020) 381 Final. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0381 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Muska, A.; Pilvere, I.; Viira, A.-H.; Muska, K.; Nipers, A. European Green Deal Objective: Potential Expansion of Organic Farming Areas. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Replies of the European Commission to the European Court of Auditors’ Special Report ‘Organic Farming in the EU: Gaps and Inconsistencies Hamper the Success of the Policy’. 2024. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECAReplies/COM-Replies-SR-2024-19/COM-Replies-SR-2024-19_EN.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Singhalage, I.D.; Seneviratne, G.; Madawala, H.M.S.P.; Wijepala, P.C. Profitability of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa) production with biofilmed biofertilizer application. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 243, 411–413, ISSN 0304-4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Peng, L.; Zhang, H.; Han, L.; Li, Y. Microbial biofertilizers increase fruit aroma content of Fragaria × ananassa by improving photosynthetic efficiency. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 5323–5330, ISSN 1110-0168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreyra-Suarez, D.; García-Depraect, O.; Castro-Muñoz, R. A review on fungal-based biopesticides and biofertilizers production. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116945, ISSN 0147-6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhiman, V.K.; Rana, N.; Dhiman, V.K.; Sharma, P.; Singh, D. Assessing the drought-tolerance and growth-promoting potential of strawberry (fragaria× ananassa duch.) rhizobacteria for consortium bioformulation. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 2024, 33, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Félix, J.D.; Silva, L.R.; Rivera, L.P.; Marcos-García, M.; García-Fraile, P.; Martínez-Molina, E.; Mateos, P.F.; Velázquez, E.; Andrade, P.; Rivas, R. Plants probiotics as a tool to produce highly functional fruits: The case of Phyllobacterium and Vitamin C in strawberries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawula, S.; Daniel, A.I.; Nyawo, N.; Ndlazi, K.; Sibiya, S.; Ntshalintshali, S.; Nzuza, G.; Gokul, A.; Keyster, M.; Klein, A.; et al. Optimizing plant resilience with growth-promoting Rhizobacteria under abiotic and biotic stress conditions. Plant Stress 2025, 17, 100949, ISSN 2667-064X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, M.; Pirlak, L.; Esitken, A.; Dönmez, M.F.; Turan, M.; Sahin, F. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) increase yield, growth and nutrition of strawberry under high-calcareous soil conditions. J. Plant Nutr. 2014, 37, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirdel, M.; Eshghi, S.; Shahsavandi, F.; Fallahi, E. Arbuscular mycorrhiza inoculation mitigates the adverse effects of heat stress on yield and physiological responses in strawberry plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 221, 109629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.R.; Hooker, J.E. Sporulation of Phytophthora fragariae shows greater stimulation by exudates of non-mycorrhizal than by mycorrhizal strawberry roots. Mycol. Res. 2000, 104, 1069–1073, ISSN 0953-7562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhaoui, A.; Taoussi, M.; Laasli, S.-E.; Legrifi, I.; El Mazouni, N.; Meddich, A.; Hijri, M.; Lahlali, R. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and their role in plant disease control: A state-of-the-art. Microbe 2025, 8, 100438, ISSN 2950-1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowicz, V.A. The impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on strawberry tolerance to root damage and drought stress. Pedobiologia 2010, 53, 265–270, ISSN 0031-4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoebitz, M.; López, M.D.; Roldán, A. Bioencapsulation of microbial inoculants for better soil–plant fertilization. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Püschel, D.; Kolaříková, Z.; Šmilauer, P.; Rydlová, J. Survival and long-term infectivity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in peat-based substrates stored under different temperature regimes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 140, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Sánchez, B.; Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Morales-Cedeño, L.R.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.d.C.; Saucedo-Martínez, B.C.; Sánchez-Yáñez, J.M.; Fadiji, A.E.; Babalola, O.O.; Glick, B.R.; Santoyo, G. Bioencapsulation of Microbial Inoculants: Mechanisms, Formulation Types and Application Techniques. Appl. Biosci. 2022, 1, 198–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.P.; Meyer, K.M.; Kelly, T.J.; Choi, Y.W.; Rogers, J.V.; Riggs, K.B.; Willenberg, Z.J. Environmental Persistence of Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus subtilis Spores. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma, R.; Paliwal, J.S.; Chopra, P.; Dogra, D.; Pooniya, V.; Bisaria, V.S.; Swarnalakshmi, K.; Sharma, S. Survival, efficacy and rhizospheric effects of bacterial inoculants on Cajanus cajan. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 240, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.J.; Franco, H.C.J.; Magalhães, P.S.G. Liquid fertilizer application to ratoon cane using a soil-punching method. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 165, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, M.J.; Or, D.; Shokri, N. Localized Delivery of Liquid Fertilizer in Coarse-Textured Soils Using Foam as Carrier. Transp. Porous Media 2022, 143, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, A.; Chattaraj, S.; Mitra, D.; Ganguly, A.; Kumar, R.; Gaur, A.; Mohapatra, P.K.; Santos-Villalobos, S.d.L.; Rani, A.; Thatoi, H. Advances in microbial based bio-inoculum for amelioration of soil health and sustainable crop production. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 7, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Singh, A.V.; Gautam, S.S.; Agarwal, A.; Punetha, A.; Upadhayay, V.K.; Kukreti, B.; Bundela, V.; Jugran, A.K.; Goel, R. Microbial bioformulation: A microbial assisted biostimulating fertilization technique for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1270039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.A.; Anderson, W.K. Soil Compaction in Cropping Systems: A Review of the Nature, Causes and Possible Solutions. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 82, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, N.J. A Review of Non-Equilibrium Water Flow and Solute Transport in Soil Macropores: Principles, Controlling Factors and Consequences for Water Quality. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G.P.; Laudone, G.M.; Gregory, A.S.; Bird, N.R.A.; Matthews, A.G.D.G.; Whalley, W.R. Measurement and simulation of the effect of compaction on the pore structure and saturated hydraulic conductivity of grassland and arable soil. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, W05501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodlu, M.G.; Raoof, A.; Sweijen, T.; van Genuchten, M.T. Effects of sand compaction and mixing on pore structure and the unsaturated soil hydraulic properties. Vadose Zone J. 2016, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbarki, Y.; Gumière, S.J.; Céléncourt, P.; Brédy, J. Study of the effect of the compaction level on the hydrodynamic properties of loamy sand soil in an agricultural context. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1255495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, N.B.; Li, Y.X.; Bittman, S.; Lapen, D.R.; Burtt, S.D.; Patterson, B.S. Draft requirements for contrasting liquid manure injection equipment. Can. Biosyst. Eng. 2006, 48, 2.29–2.37. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, J.E.; Chichester, F.W. Subsurface Fertilizer Applicator for Conservation-Tillage Research. Appl. Eng. Agric. 1988, 4, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.L. Rolling Spoke Wheel Punches in Fertilizer. Farm Show Mag. 1983, 7, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.L.; Colvin, T.S.; Marley, S.J.; Dawelbeit, M.L. A Point-Injector Applicator to Improve Fertilizer Management. Appl. Eng. Agric. 1989, 5, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaylock, A.D.; Cruse, R.M. Ridge-Tillage Corn Response to Point-Injected Nitrogen Fertilizer. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, W.B.; Blaylock, A.D.; Krall, J.M.; Hopkins, B.G.; Ellsworth, J.W. Sugarbeet Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency with Preplant Broadcast, Banded, or Point-Injected Nitrogen Application. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, M.C.; Gayler, R.R. Alternative Systems for Cultivating and Side Dressing Specialty Crops for Improved Nitrogen Use Efficiency. In Proceedings of the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers Annual International Meeting, Orlando, FL, USA, 17–20 July 2016; p. 162456725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, M.C.; Gayler, R.R.; Nolte, K.D. Improving Lettuce Production through Utilization of Spike Wheel Liquid Injection Systems. In Proceedings of the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers Annual International Meeting, Louisville, KY, USA, 7–10 August 2011; p. 1111245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.J.; Magalhães, P.S.G. Modeling and design of an injection dosing system for site-specific management using liquid fertilizer. Precis. Agric. 2019, 20, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, M. Microbial inoculation of seed for improved crop performance: Issues and opportunities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5729–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Wang, Q.; Cao, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, S.; Gong, S. Development and Performance Evaluation of a Precise Application System for Liquid Starter Fertilizer while Sowing Maize. Actuators 2021, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, S.S.; Prasanna, N.L.; Sudhakar, S.; Arvind, M.; Akshaya, C.K.; Nigam, R.; Kumar, S.; Elangovan, M. A Review on Role of Root Exudates in Shaping Plant-Microbe-Pathogen Interactions. J. Adv. Microbiol. 2024, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; van Elsas, J.D. Mechanisms and ecological implications of the movement of bacteria in soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 129, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattner, S.W.; Milinkovic, M.; Arioli, T. Increased growth response of strawberry roots to a commercial extract from Durvillaea potatorum and Ascophyllum nodosum. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2943–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotar, V.K.; Chizhevskaya, E.P.; Vorobyov, N.I.; Bobkova, V.V.; Pomyaksheva, L.V.; Khomyakov, Y.V.; Konovalov, S.N. The Quality and Productivity of Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Improved by the Inoculation of PGPR Bacillus velezensis BS89 in Field Experiments. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASAE S313.3 FEB04; Soil Cone Penetrometer. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/105134072/ASAE-S313-3-Soil-Cone-Penetrometer (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Lowery, B.; Morrison, J.E. Soil Penetrometers and Penetrability. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 4: Physical Methods; Dane, J.H., Topp, G.C., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2002; pp. 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 13041: 2011; Soil Improvers and Growing Media. Determination of Physical Properties—Dry Bulk Density, Air Capacity, Water Capacity, Shrinkage and Total Porosity. PKN—Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. Available online: https://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-13041-2011e.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- PN-EN 13039: 2011; Soil Improvers and Growing Media. Determination of Organic Matter Content and Ash. PKN—Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. Available online: https://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-13039-2011e.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Kuś, J. Glebowa materia organiczna—znaczenie, zawartość i bilansowanie. Stud. I Rap. IUNG-PIB 2015, 45, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, C.; Pachepsky, Y.; Martín, M.Á. Technical note: Saturated hydraulic conductivity and textural heterogeneity of soils. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 3923–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soilmoisture Equipment Corp. 2816G1/G5 Operating Instruction; Soilmoisture Equipment Corp.: Goleta, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 28–29. Available online: https://device.report/m/e6bc44b73e5d544f670b184e570334ee455eefd96694f36576cb118bf16be9ea.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Schroeder, A.B.; Dobson, E.T.A.; Rueden, C.T.; Tomancak, P.; Jug, F.; Eliceiri, K.W. The ImageJ ecosystem: Open-source software for image visualization, processing, and analysis. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, P.; Nelson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural Uses of Plant Biostimulants. Plant Soil 2014, 383, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malusà, E.; Vassilev, N. A Contribution to Set a Legal Framework for Biofertilisers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 6599–6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengough, A.G.; Bransby, M.F.; Hans, J.; McKenna, S.J.; Roberts, T.J.; Valentine, T.A. Root Responses to Soil Physical Conditions; Growth Dynamics from Field to Cell. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Rasband, W.; Eliceiri, K. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, C.; Widemann, B.T.Y.; Lange, H. Image analysis of dye stained patterns in soils. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2013, 15, EGU2013-6150. Available online: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU2013/EGU2013-6150.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Miot, H.A. Correlation analysis in clinical and experimental studies. J. Vasc. Bras. 2018, 17, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graffelman, J.; de Leeuw, J. Improved Approximation and Visualization of the Correlation Matrix. Am. Stat. 2023, 77, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerton, H.M.; Li, B.; Stavridou, E.; Johnson, A.; Karlström, A.; Armitage, A.D.; Martinez-Crucis, A.; Galiano-Arjona, L.; Harrison, N.; Barber-Pérez, N.; et al. Genetic and phenotypic associations between root architecture, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonisation and low phosphate tolerance in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedziński, T.; Rutkowska, B.; Łabętowicz, J.; Szulc, W. Effect of Deep Placement Fertilization on the Distribution of Biomass, Nutrients, and Root System Development in Potato Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).