Abstract

Background: Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) have emerged as innovative tools in healthcare, particularly using diagnostic and interventional imaging methods, offering new avenues for enhancing patient care and procedural outcomes. Their applications range from improving preoperative planning and pain management to providing advanced procedural support and training. Despite their growing integration into clinical practice, evidence of their cost-effectiveness and specific clinical benefits when using radiological tools remains limited. This review aims to map the current landscape of VR and AR applications using radiological modalities and highlight areas for future research. Objective: This scoping review explores the clinical applications of VR and AR in different radiological fields, aiming at assessing target areas, cost-effectiveness, and benefits of these technologies. Methods: We conducted a comprehensive literature search using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework. A total of 15 primary studies were included, covering diverse populations and applications of VR and AR. Results: In total, 15 studies (N = 781 patients) were included, with sample sizes ranging from 6 to 120. These studies highlighted various clinical applications of VR and AR, including imaging-guided preoperative planning, pain management, and procedural support. Although several studies demonstrated improvements in patient experiences and diagnostic accuracy, cost-effectiveness data were lacking. Notably, 47% of the studies focused exclusively on pediatric populations (N = 363), and 33% were randomized controlled trials. Quality assessment using the STARD criteria revealed that 60% of studies were rated as good (score > 12), 27% as fair (score 10–12), and 13% as suboptimal (score < 10), with inter-reader reliability showing substantial agreement (ICC = 0.76; 95% CI: 0.64–0.91). Out of 15 included studies, only 6 (40%) reported statistically significant improvements in patient experiences, with the remaining studies reporting positive trends (e.g., feasibility, usability, improved planning). Individual studies demonstrated significant benefits of VR interventions; for instance, one study reported a reduction in distress scores by a mean of 3.0 (95% CI: 1.0–5.0) and a decreased need for parental presence (risk ratio 0.3; 95% CI: 0.1–0.7; p < 0.001) compared to conventional methods. Conclusions: VR and AR technologies hold promise in enhancing patient care and procedural outcomes. Future research should focus on the cost-effectiveness of these technologies and identify specific target populations that would benefit the most. Additionally, adherence to the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) guidelines should be encouraged to ensure transparent and comprehensive reporting in VR and AR studies.

1. Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are technological advancements extensively used in entertainment, sports, gaming, and simulation [1]. VR and AR hold the potential to revolutionize how clinicians manage healthcare conditions and how patients undergo diagnostic testing and therapeutic procedures. These technologies can assist healthcare professionals in addressing cognitive challenges related to patient treatment and planning, managing phobias, alleviating pain, addressing other disease-related symptoms, and planning complex virtual surgeries [2], thereby enabling more cost-effective decision-making in patient care.

VR is characterized by immersing the user in a simulation, specifically in a three-dimensional computer-generated environment [3]. Within this environment, users have no visualization of the world outside the virtual environment; sensory input is provided through a head-mounted display, replacing the user’s native surroundings. As a result, users perceive themselves as experiencing a non-physical virtual world [3,4,5]. In contrast, AR does not entirely eliminate the real world from the user’s view [4]. Instead, virtual objects and structures are superimposed onto the “real world” via a head-mounted display or another type of interface, enabling users to interact simultaneously with both real and virtual elements [6,7].

Competitive markets and advances in hardware and software have driven down the costs of VR and AR technologies, facilitating their integration into various medical applications such as medical education, procedural planning, and therapeutic interventions.

Current and future applications of VR and AR include providing alternative approaches to 3D printing allowing radiologists to interact with images in a 3D format, aiding in a better informed decision-making process; (2) facilitating the understanding of anatomic relationships for diagnosis, interventional radiology procedures and surgical planning of complex health conditions; (3) assisting in real-time reconstructions (e.g., AR superimpositions onto patients during vascular interventions); (4) enhancing image interpretation in radiology reading rooms [8]; (5) serving as relaxation or distraction therapy to reduce pain and anxiety in patients, particularly as an alternative to medication [3]; (6) offering interactive VR and AR simulations for education and training on challenging anatomical concepts [4]; (7) expediting review and analysis of imaging data for clinical research [9]; (8) enabling remote monitoring and treatment of patients [9].

Despite the availability of scoping and systematic reviews on medical education applications of VR and AR [10,11,12] and the effect of VR on pain, anxiety, and fear among emergency department patients [13], and of papers on clinical applications of VR and AR in radiology on an unstructured or narrative basis [3,4,9,14], to our knowledge, no previous scoping or systematic review has specifically addressed their clinical applications in the pediatric or adult population. Of note, the pediatric population can particularly benefit from these technologies due to behavioral challenges during imaging.

The purpose of this scoping review is to assess the current state of knowledge on non-education-based applications of VR and AR in radiology in pediatric and adult populations. A comprehensive understanding of the current applicability of VR and AR in the medical field should guide further investigations into their value in specific areas of medicine, support the development of evidence-based guidelines, and highlight gaps in the literature concerning their use for both patients and healthcare professionals. Hence, the overarching study questions of this scoping review are:

- What are the target areas of non-educational clinical applications of VR and AR in the pediatric and adult populations?

- Are VR and AR cost-effective strategies in the clinical or surgical management of patients compared with traditional strategies?

- What are the benefits of utilizing these novel technologies in the proposed population, including their impact on the accuracy of diagnostic tests?

2. Methods

The Research Ethics Board of our institution waived approval due to the public domain nature of the primary studies included in this review.

2.1. Study Design Framework

The Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-ScR) [15] were used to define the study cohort characteristics, study design, and methods. PRISMA-ScR is not a quality assessment tool, but instead it is designed to ensure transparent reporting in systematic reviews. The PICO eligibility criteria are summarized in Table 1. The Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (S) [16] were applied to assess the reporting quality of the literature included in this review. Although STARD is primarily for diagnostic accuracy, we selected it to assess reporting transparency across heterogeneous study designs. Items that were not applicable (e.g., reference-standard criteria) were marked N/A in the checklist.

Table 1.

PICOS eligibility criteria for included studies.

2.2. Search and Data Collection Strategies

The initial electronic literature search was conducted by two independent reviewers (T.O. and H.B.) with the assistance of an experienced staff librarian (Q.M.) and was later updated by an independent reviewer (S.M.L.) with another staff librarian (J.C.). Studies were identified using a predefined list of search terms tailored for MEDLINE OvidSP (US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), EMBASE (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and the Cochrane Library from 1 January 2000 to 30 January 2025. Manual screening of reference lists from the included studies was also conducted.

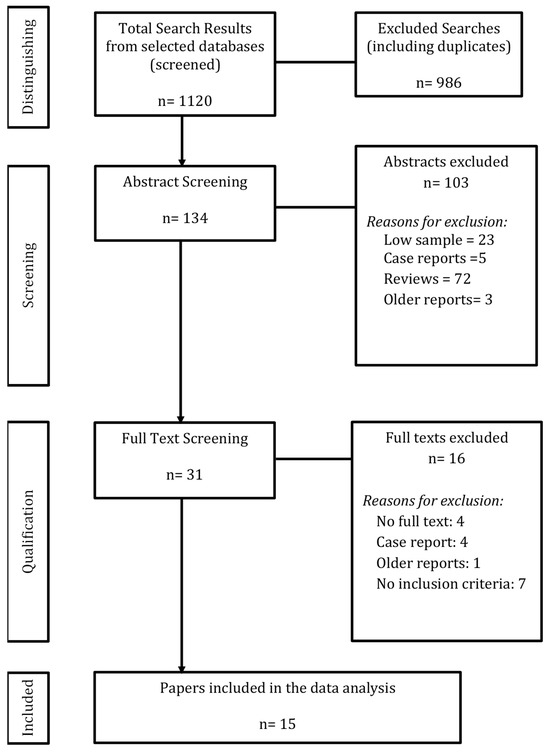

Search terms were adapted for each database’s vocabulary, using combinations such as (virtual reality OR augmented reality) AND (diagnostic imaging OR radiology) AND (pediatrics OR infant OR child OR adolescent). Additional age-specific text search terms were applied. Details of the search strategy are available in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature search output and study identification.

2.3. Study Selection Process

Titles and abstracts were independently screened for inclusion by three reviewers (T.O., H.B., and S.M.L.) to determine eligibility. Full articles were read by reviewers for final inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by a senior reviewer (A.S.D.), an experienced epidemiologist and radiologist with over 20 years of expertise, who acted as a tiebreaker.

Papers with consensus among reviewers were included in the review. Following the resolution of discrepancies, full-text articles of the selected abstracts were retrieved. These articles were then assessed using predetermined eligibility criteria. The initial batch was reviewed by T.O. and H.B., while the updated batch was reviewed by S.M.L., with calibration sessions involving A.S.D. for systematic consistency. Details of the selection process are illustrated in Figure 1.

2.4. Eligibility Criteria for Primary Studies

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (a) clinical studies or case series with 6 or more subjects: (b) use of virtual reality as a clinical (e.g., pre-operative planning), interventional (e.g., as an analgesic or relaxation method, ultrasound-guided anesthesia), alternative therapy (e.g., as an alternative to 3D printing in radiology) or training tool to an imaging diagnostic test or imaging-guided procedure or that used imaging as an outcome measure; (c) be written in English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, Korean, or Italian; (d) be PubMed-indexed.

Exclusion criteria included non-human studies, publications prior to 2000 (to focus on newer technologies), abstracts from scientific meetings, editorials, personal opinions, letters to the editor, protocols, case reports, and reviews. We did not restrict inclusion by age group; both pediatric and adult clinical imaging applications of VR/AR were eligible. The fact that 7 of the 15 included studies (47%) focused exclusively on pediatric populations emerged post hoc during data extraction rather than being an a priori focus.

2.5. Data Extraction, Analysis and Critical Appraisal

Following the final selection, data extraction and critical appraisal were performed. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist [9] was used to guide the database of study characteristics for the included studies.

The Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) checklist [16] was used to assess reporting quality and methodology of selected primary papers. The original 2015 STARD [16] has a 34-point maximum for the sum of the 30 essential items (all articles receiving a score of 1), taking into account that items 10, 12, 13 and 21 are dichotomous (i.e., a, b for each item) and items 10b, 11, 12a/b, 13a/b; 14–17; 22; 23, 24, 25 are related to a reference standard which was not used in most primary studies of this review; a modified maximum score of 20 was used to assess reporting quality of included primary articles. Scores were categorized as follows: (a) good quality: >12; (b) fair quality: 10–12; (c) suboptimal quality: <10. The papers were independently assessed, reviewed and scored by the reviewers (S.M.L., T.O. and H.B). Any discrepancies in scoring, where consensus was not achieved, was discussed and resolved by the tiebreaker (A.S.D.).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

STARD scoring was designated as follows: 1, fully meets condition; 0.5, partially meets condition; 0, does not meet condition; N/A, not applicable. STARD scores were categorized as follows: (a) excellent quality: >15; (b) good quality: >12; (c) fair quality: 10–12; (d) suboptimal quality: <10.

STARD agreement levels were defined as: total agreement, identical scores by both reviewers; partial agreement, scores differed by 0.5 points (e.g., 0 and 0.5); no agreement, full score difference (e.g., 0 and 1). Inter-rater reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) to evaluate agreement between reviewers’ STARD scores. As per Altman et al. [18] based on 95% confidence intervals of ICCs, values >0.80 indicated excellent inter-reader reliability; values 0.61–0.80, substantial reliability; values 0.41–0.60, moderate reliability and values ≤0.40, poor reliability.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The search yielded 1120 references, from which 986 duplicates and disparate studies were removed. A total of 134 studies underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 103 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, 31 studies were assessed for full-text eligibility, and 16 were excluded as described in Figure 1. Ultimately, 15 studies were included in the scoping review: 9 (60%) focused on pre-operative planning and 6 (40%) on interventions. The 15 included primary studies encompassed a total of 781 patients. However, due to the lack of standardized reporting of demographic details, a comprehensive age analysis was not feasible. Only 60% of studies specified participant sex, and 0% reported ethnicity. The average, median, and range for age of patients of included primary studies are reported in this review as they appeared in the original articles.

The summary characteristics of the primary studies and participants are presented in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 2.

Study and Patient Characteristics.

Table 3.

Intervention details and Key findings.

Table 4.

Study Design and Outcomes.

Table 5.

Technical Setup and Intervention Type.

3.2. Primary Studies’ Research Design

Most primary studies (33%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Sample sizes across all studies were small (ranging from 6 to 120 patients). Furthermore, psychometric properties [18] were not applied to measurements or scales used in these studies.

- -

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective design: 5 studies (33.3%) [22,24,25,27,33], including one single-blinded study [33].

- -

- Descriptive/case series (6–10 patients): 5 studies (33.3%) [19,20,23,26,31].

- -

- Protocol development/virtual modeling for specific clinical indications (>10 patients): 3 studies (20%) [29,30,32].

- -

- Non-RCT cross-sectional study with a control group: 1 study (6.7%) [29].

There was substantial variability in study design, power calculations, and sample sizes across studies. The greatest variability was observed within case series, with sample sizes ranging from 6 patients in studies by Ieiri and Souzaki [19,20] to 120 participants in Ryu’s paper [25].

Seven of the 15 studies (47%) focused exclusively on pediatric populations (N = 363 patients), including studies by Ieiri et al., Souzaki et al., Zhao et al., Han et al., Milano et al., Stunden et al., Ryu et al. [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Patient ages ranged from 0.1 month to 15 years. However, demographic reporting was inconsistent, with some studies failing to mention patient sex [21,23,26,27,28].

3.3. Reporting Quality of Primary Studies (Using STARD)

The overall quality of reporting, as assessed using the STARD guidelines [16], was deemed good/acceptable. Of the studies included in this review, 27% were considered as presenting with excellent quality scores (scores > 15) [22,24,27,33], 40% as good/acceptable quality (scores > 12) [21,23,25,28,29,32], 20% were considered as of fair quality (scores ≥ 10 and ≤12) [19,26,30] and 13% were classified as presenting with suboptimal quality (scores < 10) [20,31] (Table 6).

Table 6.

Standard for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) consensus scores for primary studies of this review.

Several sections of the primary studies were suboptimally reported, including intended sample size, flow diagrams, registration information, and full protocol access. Suboptimally reported sections included:

- -

- Title or Abstract and Introduction: item 1: identification of the study as a diagnostic accuracy study using at least one measure of accuracy: no papers met this criterion.

- -

- Methods (Study Design, Participants, Test Methods, Analysis): item 6: eligibility criteria: 4/15 studies scored 0; item 8: reporting where and when eligible participants were identified: 3/15 scored 0, and 2/15 scored 0.5; item 9: participant recruitment methods (e.g., consecutive, random, convenience): only 8/15 (53.3%) studies provided details; item 18: intended sample size and determination method: only 5/15 (33.3%) studies provided this information.

- -

- Results (Participants, Tests): item 19: flow diagrams of participant selection: only 6/15 studies (40%) included diagrams; item 20: 10/15 (66.6%) scored 1, 2/15 (13.3%) scored 0.5 for demographic and clinical characteristics.

- -

- Discussion: item 26: 2/15 (13.3%) papers scored zero on consensus for not adequately presenting study limitations.

- -

- Other Information: item 28: 7/15 (46.7%) did not present a registration number or the name of a registry. This may be because only 5 papers (33%) were classified as clinical studies; item 29: only 4/15 (26.7%) studies mentioned where the full protocol could be accessed; item 30: 5/15 papers (33.3%) did not list sources of funding or other forms of support.

- -

- The final STARD scores of the papers are presented in Table 6. Supplementary Table S1 shows the full STARD breakdown of items per study.

3.4. Inter-Reader Reliability of STARD Scoring

Inter-reader agreement for STARD scoring was substantial, with an ICC of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.64–0.91) for the 15 reviewed studies. The most frequent disagreements occurred on methods items—particularly STARD item 6 (eligibility criteria), item 8 (where and when participants were identified), and item 9 (recruitment methods)—each showing initial reviewer differences of 0.5 point. All were reconciled through consensus with the senior reviewer.

3.5. Summary of Data from Primary Studies

Out of 15 included studies, 6 (40%) reported statistically significant improvements in patient experiences (Han et al., 2019, [22]; Ryu et al., 2021, [25]; Yang et al., 2019, [33]; Nambi et al., 2020, [27]; Sadri et al., 2023, [28]; Chuan et al., 2023, [29]). The remaining 9 (60%) studies reported positive trends (e.g., feasibility, usability, improved planning) but without statistical testing or without reaching significance (Kockro et al., 2000, [30]; Hohlweg-Majert et al., 2005, [31]; Qui et al., 2010, [32]; Ieiri et al., 2012, [19]; Souzaki et al., 2013, [30]; Zhao et al., 2015, [21]; Simpfendorfer et al., 2016, [26]; Milano et al., 2021, [23]; Stunden et al., 2021, [24]). Specifically, this scoping review aimed to address the following overarching questions:

Target areas of clinical applications of VR and AR in the pediatric and adult populations:

Clinical applications of VR and AR reported in the primary studies primarily related to pre-surgical planning.

In pediatric populations, Milano et al. [23] explored the advantages of enhanced 3D visualization for complex cardiac surgery planning, Han et al. [22] and Ryu et al. [25] each showed that immersive VR education can reduce pediatric anxiety and procedural times during chest radiography.

In adult populations, Kockro et al. [30] tested new intraoperative software. In more recent investigations, Chuan et al. [29] designed a high-fidelity VR trainer for teaching ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia skills to adults.

Evaluating both children and adults, Qui et al. [32] assessed the effectiveness of image processing in pre-surgical planning. Whereas Zhao et al. [21] reported on the intraoperative support provided by VR in patients aged 1–20 months, Simpfendorfer et al. [26] did so in adults. As direct clinical interventions, VR was compared to conventional therapies in studies by Yang et al. and Nambi et al. [27,33]. Yang evaluated adolescents and adults (age range, 14–62 years) in the VR group and young to senior adults (age range, 20–65 years) in the non-VR group. Nambi, on the other hand, assessed young adults (age range, 18–25 years) only, whereas Sadri et al. [28] further demonstrated the potential of AR overlays to reduce contrast use during cerebral embolic protection in TAVR without prolonging the procedure.

Concerning the overarching question #1 of this scoping review (“What are the target areas of non-educational clinical applications of VR and AR in the pediatric and adult populations?”), the studies of this review employed different methods for planning, patient preparation and procedural guidance.

1. Planning And Pre-Operative Visualization

Primary studies of this review demonstrated how VR/AR enhanced pre-surgical planning by improving visualization of complex anatomy. In children and adults, Kockro et al. [30] applied the costly VIVIAN VR system for neurosurgical planning, enabling intuitive spatial navigation but requiring significant resources. Similarly, in a mixed aged population (patients aged 4–70 years), Qui et al. [32] used VR stereoscopic tractography for glioma surgery, achieving trajectory optimization and safer resections and Hohlweg-Majert [31] applied VR in craniofacial reconstruction across a broad mixed population (infants to adults). In pediatric populations, Milano et al. [23] showed that VR provided more cost-effective visualization compared to 3D printing for congenital cardiac surgery.

2. Patient Preparation And Anxiety Reduction

The results of this review showed that pediatric patients benefited most clearly from VR interventions aimed at anxiety reduction, while adult populations showed improvements in surgical anxiety and rehabilitation support. Immersive VR interventions consistently reduced anxiety and improved patient experiences, particularly in pediatric radiology. Han et al. [22] and Ryu et al. [25] demonstrated statistically significant reductions in distress during pediatric chest radiography, with shorter procedure times and less parental presence required. Yang et al. [33] reported similar benefits in a mixed aged population of children and adults undergoing arthroscopic knee surgery, with improved preoperative anxiety scores. Nambi et al. [27], on the other hand, used VR rehabilitation in young adults with chronic low back pain, reporting both imaging and biochemical improvements.

3. Procedural Support And Training

VR and AR provided tangible procedural benefits across populations. Pediatric applications focused on intraoperative visualization, while adult applications extended to interventional radiology and anesthesia training. In primary studies of this review, AR and VR systems were applied to real-time procedural support and skill training. Souzaki et al. [20] used AR overlays in pediatric oncology to assist with tumor localization during surgery. Stunden [24] and Chuan [29] developed VR training systems for ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia, showing performance improvements in both novice and experienced adult clinicians.

Cost-effectiveness of VR and AR in clinical or surgical management of patients compared to conventional strategies

While most studies of this scoping review did not provide formal economic analyses, four studies offered insights into cost implications of VR or AR in clinical applications.

Sadri et al. [28] examined the cost-effectiveness and procedural improvements offered by AR during cerebral embolic protection (CEP) in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) of adults. The study demonstrated that AR significantly reduced the need for contrast angiography during procedures, resulting in lower contrast volume usage without increasing procedure times. The reduction in contrast used also minimized the risks of contrast-induced complications, such as nephropathy, providing additional long-term health benefits. The authors emphasized that while AR systems may involve substantial initial investment, the reduction in contrast usage, procedure times, and improved physician confidence make AR a cost-effective solution in procedural interventions.

Certain operating systems, such as the Virtual Intracranial Visualization and Navigation (VIVIAN) System used in Kockro et al.’s study of children and adults [30], provided advanced visualization but was resource-intensive and costly due to specialized equipment and programming. Conversely, Yang et al.’s study of children and adults [33] utilized commercially available head-mounted displays (HTC VIVE), which are head-mounted hardware and software displays/systems, more affordable financially. These systems have become increasingly less expensive since the time of the study’s publication, potentially enhancing their accessibility for broader clinical use. Milano et al. [23] commented that VR was less costly than 3D printing for complex congenital cardiac surgical planning in a pediatric population. Therefore, cost-effectiveness varied, with commercial VR showing overall a lower cost potential compared to specialized platforms.

Benefits of using VR and AR, including implementation of the accuracy of diagnostic tests

Nambi et al. stated that “virtual reality training is widely used because it reduces the difficulty of rehabilitation and increases participant safety” [27]. Yang et al.’s study reported significant improvements in APAIS (Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale) scores for assessing preoperative anxiety in the VR group compared to the control group [33]. Furthermore, studies by Ieiri, Souzaki, and Milano [19,20,23] demonstrated the benefits of VR-assisted surgical planning. Their findings highlighted accurate identification, successful imaging guidance, and precise resection planning facilitated by VR.

The VR studies described in the primary papers of this review encompassed diverse applications, ranging from clinical interventions aimed at improving patient care to educational programs for training and skill development. Similarly, AR studies revealed versatile applications, with a strong focus on enhancing clinical procedures and providing educational guidance across various medical and surgical contexts. This was compared to conventional training exercises combined with Swiss ball rehabilitation over a four-week period. Zhao et al. [21] evaluated MR virtual endoscopy (MRVE), a virtual imaging technology that enables the visualization of the inner surface of lumina. MRVE was used to identify pathological changes in the cerebral ventricles and measure lumen diameters in hydrocephalus patients. Simpfendorfer et al. [26] employed intraoperative cone-beam CT images with AR guidance to ensure safe resection lines in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy procedures. Yang et al. [33] introduced a preoperative VR experience using 3D-reconstructed knee MRIs for patients undergoing arthroscopic knee surgery. This intervention reduced preoperative anxiety and improved patient satisfaction, underscoring the clinical utility of VR in enhancing the preoperative care experience.

Nambi et al. [27] implemented balance exercise training using the ProKin system, focusing on core stability in university football players with chronic low back pain. Beyond these examples, Chuan et al. [29] developed a high-fidelity VR trainer for ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (UGRA), demonstrating improved skill acquisition among novice practitioners and reinforcing VR’s potential to enhance procedural accuracy and confidence. Han et al. [22] and Ryu et al. [25] similarly showed that immersive VR education decreases anxiety and distress in pediatric patients undergoing chest radiography, thereby reducing procedure time and potentially improving the quality of imaging. Meanwhile, Sadri et al. [28] highlighted how AR overlays can offer precise visualization of patient-specific anatomy in TAVR procedures, minimizing contrast usage without increasing procedure time. Collectively, these findings underscore the significant benefits of VR and AR in achieving more accurate diagnostics, improved safety, and higher procedural efficiency.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

This scoping review identified published literature on the use of VR and AR as clinical or surgical imaging-based aid tools, for both pediatric and adults populations. Several studies highlighted the potential of these immersive technologies to enhance surgical planning, reduce patient anxiety, and improve procedural efficiency.

4.2. Population

Different types of treatments applied virtual reality experiences. Hohlweg-Majert et al. in Navigational Maxillofacial Surgery Employing Virtual Models [26] assessed the benefit of using VR in patients ranging from 3 weeks to 80 years. This article specifically informed readers on how virtual reality reacts in a preoperative environment and as an intraoperative navigational tool. Most of our research had no intention of restricting themselves to specific populations or age categories since we wanted to learn about the benefits of using this unique technology. Because we only found fifteen papers that addressed the research questions of this scoring system, we concluded that VR and AR are at critical stages of evaluation compared to existing technologies. There are many factors to consider when identifying target audiences, evaluating outcomes such as patient health and clinician benefits, and assessing the feasibility and resources for translation and implementation into clinical practice. As a result, we felt it was critical not to limit our target group, and we thought it was necessary to consider the total influence of VR and AR on all populations.

4.3. Improvement of Population Health and Experiences of Care

Our scoping study assessed new services that are now available due to advances in virtual reality technology, which may help all physicians to deal with complex surgeries. VR can facilitate the performance of procedures for distal radius fractures which are typically challenging. VR/AR allows the surgeon to do a more effective procedure because it affords a better view of the distal radius, which has a small diameter. The use of virtual reality increased the surgeon’s anatomic prediction capability as anticipating the final placement of the distal radius post osteotomy favored the use of a CT virtual reality environment [34]. The improved patient experience in alleviating pain and anxiety in procedures is demonstrated. It will be important in the future to create more objective criteria guidelines concerning patients’ experiences during VT/AR procedures for different age groups, including patients for whom VR can be challenging to tolerate such as older patients and persons with phobias. Additionally, VR has been shown to alleviate pain or anxiety, an effect that Han et al. [22] and Ryu et al. [25] both demonstrated in pediatric patients undergoing radiographic exams. By immersing children in a virtual environment before or during a procedure, these studies reported less distress, shorter procedure times, and higher patient (and parental) satisfaction.

From a training standpoint, Chuan et al. [29] showed that novice anesthesiologists learning ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia via VR-based training could achieve more accurate skill acquisition and improved procedural confidence. Collectively, these examples suggest that VR or AR can improve health outcomes and care experiences by fostering higher provider proficiency and supporting patients whether by lowering anxiety in children or boosting operator skill in complex tasks. However, future research should establish objective guidelines on how VR/AR influences patient and provider experiences, with attention to populations (e.g., older adults, patients with phobias) who might find immersive technologies more challenging.

Based on the target areas of clinical applications of VR/AR of this review, the information from primary studies focused more on the benefit of VR utilization from the physician’s perspective as they would be able to better understand the 3D reconstructed MR images.

Yang et al. [33] looked at the effect of VR experience in 3D reconstructed magnetic resonance images on anxious patients undergoing arthroscopic knee surgery. Because most adults realize the realities of undergoing surgery, this form of virtual reality usage would be more acceptable as a pediatric intervention. Nambi et al. [27] observed a study in which the age range was 18–25 years old and determined the radiological and biochemical effects of VR training in football players with persistent back pain. This is an example of proper VR use in a young-adult population, where VR is used to meet the needs of this specific population. Finally, Qui et al. [32] examine the potential clinical applications of presurgical 3D environments in patients with brain gliomas near motor circuits. The participants in this study ranged from 4 to 70 years old. The average age, however, was 46 (+/−17.98). This study is an excellent example of VR being used in people who have more severe acquired health consequences due to simply living longer. Therefore, our broad target group enabled us to examine the benefits of this unique technique across all specified demographics. However, future studies must define whether VR would be more effective for specific populations.

4.4. VR Technology

Few research papers suggested whether or not VR was a cost-effective intervention choice during our scoping analysis. For example, the VR technology utilized in Kockro et al. [30] was VIVIAN (Virtual Intracranial Visualization and Navigation). The VIVIAN system enables users to interact with complex imaging data rapidly, completely, and intuitively; nevertheless, when discussing the VIVIAN system’s cost, the study revealed that it was a costly operating system. Milano et al.’s study [23] also mentioned need for cost-effect evaluation in the future but deemed VR costs to be lower than 3D printing in pre-surgical planning. All the other studies made no mention of how VR affects expenses or how the VR system can help to lower intervention costs. As a result, given that the bulk of the studies we discovered focused on VR intervention, we propose that future research and development should concentrate on the cost of VR. For example, VR and AR anxiety reduction equipment, or cost-effective presurgical technology that can replace existing high-maintenance equipment, are intriguing research avenues to study.

4.5. Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) of Primary Studies

Our review found modest compliance with the STARD checklist, with only 19/34 (56%) of checklist sub-items being reported across studies. Since most primary papers did not follow traditional randomized controlled trial designs or include a reference standard for estimation of diagnostic accuracy indexes, most studies lacked reference standards in their design, precluding the assessment of STARD sub-items related to a reference standard (test methods: 10b, 11, 12a/b, 13a/b; analysis: 14–17; results (participants): 21b; 22; results (test results): 23, 24, 25) which were deemed inapplicable to the analysis of the data of primary studies of this review.

Additionally, many studies failed to report variability between VR and non-VR groups (item 17) or adverse events (item 25). These gaps highlight challenges in identifying biases and ensuring transparency in research reporting. Improved adherence to STARD guidelines is necessary to reduce bias and enhance replicability and peer approval of future studies.

Some of the included studies lacked rigorous research designs, such as reference standards for assessment of diagnostic test accuracy, limiting the assessment of STARD items. Furthermore, the restricted sample sizes and case series’ characteristics of many of the included studies reduced the reliability and external validity of conclusions. The considerable variability in statistical methodologies also hindered result aggregation. Approximately 40% of studies exhibited fair or suboptimal reporting quality, highlighting the need for more robust research design in future studies. The shift from case series and personal experiences toward robust clinical trials with rigorous methodology is vital for advancing the field.

5. Limitations

This scoping review is subject to several limitations. Although we screened 1120 records, ultimately only 15 studies met our predefined eligibility criteria. This small sample size limits the breadth and generalizability of our findings and likely reflects both the novelty of clinical VR/AR applications in radiology and our strict inclusion criteria. We searched only three databases (MEDLINE OvidSP, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library) and did not include gray literature or trial registries, so some relevant studies may have been missed. The fact that the primary studies had heterogeneous research designs ranging from randomized clinical trials to small case series made the synthesis of this scoping review challenging and a meta-analysis of data not feasible. Further, demographic reporting was incomplete, with only 60% of studies reporting participant sex, none reporting ethnicity, and an inconsistent presentation of age data, precluding meaningful subgroup analysis. As reported by the authors, 40% of studies lacked flow diagrams, 47% did not provide a trial registration number and one-third did not report funding sources. Inclusion/exclusion criteria and recruitment methods of selected primary papers were often unclear and psychometric properties of the scales used were not validated or reported. Our language restriction (English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, Korean, Italian) introduces potential publication bias. We limited our search to publications through 30 January 2025, so very recent work is not captured. Finally, we did not perform a formal risk-of-bias assessment beyond reporting transparency, which constrains our ability to evaluate methodological quality across heterogeneous study designs.

6. Future Directions

Although current studies demonstrate promise for VR/AR in procedural planning, anxiety reduction, and training, the field remains nascent. Going forward, larger multicenter randomized trials are needed to confirm clinical efficacy and to embed rigorous cost–utility analyses alongside patient-level outcomes. Standardizing demographic and reporting elements, using PRISMA-ScR for scoping reviews and STARD for diagnostic accuracy studies, will allow consistent capture of age, gender, ethnicity, and comorbidity data, and improve comparability across studies.

Research should also explore the usability and tolerability of immersive systems in older adults and patients with anxiety disorders to identify adoption barriers. Limited available data from this review suggest that VR/AR cost varies by platform. This highlights a critical research gap requiring robust economic evaluation.

Long-term follow-up is essential to assess skill retention, sustained anxiety reduction, effect on reduction in time of scanning for radiation-bearing imaging techniques and downstream overall healthcare utilization. Finally, implementation science frameworks should be applied to understand real-world barriers (IT infrastructure, staff training needed for staff adoption, workflow integration, reimbursement with the caveat of equipment cost variability, from commercial headset to specialized systems, patient tolerance issues in older adults and phobic individuals [14]), and emerging extensions such as mixed-reality, haptic feedback, and remote telementoring warrant evaluation to expand the clinical utility of VR/AR beyond current use cases.

7. Conclusions

Despite the methodological limitations of this scoping review, our findings suggest that VR holds significant potential to improve medical care. VR enhances imaging quality compared to traditional tools and offers benefits such as reduced preoperative anxiety and improved surgical outcomes. However, insufficient data exists to confirm VR’s cost-effectiveness, STARD guidelines should be more consistently followed to enhance the methodological quality of future studies, and the identification of target populations remains an area for further scientific exploration. Future clinical trials investigating new indications for VR/AR use to address gaps in the current literature and evaluating the cost-effectiveness of VR compared to other imaging and sedation techniques, particularly in vulnerable populations, such as children and older adults, are key for the advancement of the field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14207438/s1, Table S1: Standard for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) consensus scores for primary studies of this review with breakdown consensus scores of items per study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.D.; Data curation, S.M.L., H.C.B., T.O., A.G., B.T.; Formal analysis, S.M.L., H.C.B., T.O., A.S.D.; Investigation, All authors; Methodology, A.S.D.; Project administration, S.M.L., A.S.D.; Resources, A.S.D.; Supervision, A.S.D.; Writing—original draft, S.M.L., H.C.B., T.O., A.S.D.; Writing—review and editing, A.S.D., S.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Given that the information provided in this scoping review is from public domain, it did not fulfill the criteria of our institutional Research Ethics Board to require ethical approval. Under this circumstance, informed consent was waived.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for this study was waived due to the public domain and secondary data analysis characteristics of the study data.

Data Availability Statement

The authors used data from the selected primary studies as available in the public domain. For information about raw data of individual primary studies of this review, we encourage the readers to contact the authors of the primary studies directly.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Department of Diagnostic & Interventional Radiology for internal funding provided to Doria’s salary as investigator of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Andrea S. Doria unrelated to the current manuscript: Not for Profit: Technical Advisory Board of OMERACT, Co-Chair of American Board of Radiology (ACR) Pediatric Imaging Research, Co-Chair of Canadian Association of Radiology (CAN) Society of Pediatric Radiology (SPR), Board of Directors of the Society of Pediatric Radiology (SPR), Chair of the IMACS Whole Body MRI Working Group, Founder & Co-Chair of the MIT Sloan Physicians’ Group. Research Support for other studies: Novo Nordisk (Research Grant), Terry Fox Foundation (Research Grant), PSI Foundation (Research Grant), Society of Pediatric Radiology (Research Grant), Radiological Society of North America (Educational Grant). The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- University of Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Virtual Reality in the Classroom: What Is VR? Research Guides. Available online: https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/c.php?g=607624&p=4938314 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Visualise Creative Limited. Virtual Reality in the Healthcare Industry. VISUALISE. Available online: https://visualise.com/virtual-reality/virtual-reality-healthcare (accessed on 22 September 2017).

- Theingi, S.; Leopold, I.; Ola, T.; Cohen, G.S.; Maresky, H. Virtual Reality as a Non-Pharmacological Adjunct to Reduce the Use of Analgesics in Hospitals. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 2022, 6, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayed, M.; Kadom, N.; Ghobadi, C.; Strauss, B.; Al Dandan, O.; Aggarwal, A.; Anzai, Y.; Griffith, B.; Lazarow, F.; Straus, C.M.; et al. Virtual and augmented reality: Potential applications in radiology. Acta Radiol. 2020, 61, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, J.; Belec, J.; Sheikh, A.; Chepelev, L.; Althobaity, W.; Chow, B.; Mitsouras, D.; Christensen, A.; Rybicki, F.J.; La Russa, D.J. Applying modern virtual and augmented reality technologies to medical images and models. J. Digit. Imaging 2019, 32, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, C.; Stromberga, Z.; Raikos, A.; Stirling, A. The effectiveness of virtual and augmented reality in health sciences and medical anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2017, 10, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasencia, D.M. One step beyond virtual reality: Connecting past and future developments. XRDS 2015, 22, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Mendes, D.; Paulo, S.; Matela, N.; Jorge, J.; Lopes, D. VRRRRoom: Virtual Reality for Radiologists in the Reading Room. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4057–4062. [Google Scholar]

- Lastrucci, A.; Giansanti, D. Radiological Crossroads: Navigating the Intersection of Virtual Reality and Digital Radiology through a Comprehensive Narrative Review of Reviews. Robotics 2024, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelmini, A.; Duarte, M.; de Assis, A.; Guimarães, J.; Carnevale, F. Virtual reality in interventional radiology education: A systematic review. Radiol. Bras. 2021, 54, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gelmini, A.; Duarte, M.; Silva, M.; Guimarães, J.; Santos, L. Augmented reality in interventional radiology education: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shetty, S.; Bhat, S.; Al Bayatti, S.; Al Kawas, S.; Talaat, W.; El-Kishawi, M.; Al Rawi, N.; Narasimhan, S.; Al-Daghestani, H.; Madi, M.; et al. The Scope of Virtual Reality Simulators in Radiology Education: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e52953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.; Tao, J.; Chen, M.; Peng, Y.; Wu, H.; Yan, Z.; Huang, P. Effects of Virtual Reality on Pain, Anxiety and Fear Among Emergency Department Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2025, 26, e339–e352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Yu, F.; Shi, D.; Shi, J.; Tian, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Q. Application of virtual reality technology in clinical medicine. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 3867–3880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Irwig, L.; Lijmer, J.G.; Moher, D.; Rennie, D.; de Vet, H.C.W.; et al. STARD 2015: An updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 2015, 351, h5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milgram, P.; Takemura, H.; Utsumi, A.; Kishino, F. Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality–virtuality continuum. Proc. SPIE 1994, 2351, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G. Practical Statistics for Medical Research; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1991; pp. 404–408. [Google Scholar]

- Ieiri, S.; Uemura, M.; Konishi, K.; Souzaki, R.; Nagao, Y.; Tsutsumi, N.; Akahoshi, T.; Ohuchida, K.; Ohdaira, T.; Tomikawa, M.; et al. Augmented reality navigation system for laparoscopic splenectomy in children based on preoperative CT image using optical tracking device. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2012, 28, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souzaki, R.; Ieiri, S.; Uemura, M.; Ohuchida, K.; Tomikawa, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; Koga, Y.; Suminoe, A.; Kohashi, K.; Oda, Y.; et al. An augmented reality navigation system for pediatric oncologic surgery based on preoperative CT and MRI images. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2013, 48, 2479–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, J.; Gan, Y.; Liu, J.; Tan, Z.; Liang, G.; Meng, X.; Sun, L.; Cao, W. Application of MR virtual endoscopy in children with hydrocephalus. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 33, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.H.; Park, J.W.; Choi, S.I.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, H.; Yoo, H.J.; Ryu, J.H. Effect of Immersive Virtual Reality Education Before Chest Radiography on Anxiety and Distress Among Pediatric Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Milano, E.G.; Kostolny, M.; Pajaziti, E.; Marek, J.; Regan, W.; Caputo, M.; Luciani, G.B.; Mortensen, K.H.; Cook, A.C.; Schievano, S.; et al. Enhanced 3D visualization for planning biventricular repair of double outlet right ventricle: A pilot study on the advantages of virtual reality. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 2021, 2, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stunden, C.; Stratton, K.; Zakani, S.; Jacob, J. Comparing a Virtual Reality-Based Simulation App (VR-MRI) With a Standard Preparatory Manual and Child Life Program for Improving Success and Reducing Anxiety During Pediatric Medical Imaging: Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e22942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ryu, J.H.; Park, J.W.; Choi, S.I.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, H.; Yoo, H.J.; Han, S.H. Virtual Reality vs. Tablet Video as an Experiential Education Platform for Pediatric Patients Undergoing Chest Radiography: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Simpfendörfer, T.; Gasch, C.; Hatiboglu, G.; Müller, M.; Maier-Hein, L.; Hohenfellner, M.; Teber, D. Intraoperative Computed Tomography Imaging for Navigated Laparoscopic Renal Surgery: First Clinical Experience. J. Endourol. 2016, 30, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambi, G.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Alqahatani, B.A. Radiological (Magnetic Resonance Image and Ultrasound) and biochemical effects of virtual reality training on balance training in football players with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled study. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2021, 34, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadri, S.; Loeb, G.J.; Grinshpoon, A.; Elvezio, C.; Sun, S.H.; Ng, V.G.; Khalique, O.; Moses, J.W.; Einstein, A.J.; Patel, A.J.; et al. First Experience With Augmented Reality Guidance for Cerebral Embolic Protection During TAVR. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chuan, A.; Qian, J.; Bogdanovych, A.; Kumar, A.; McKendrick, M.; McLeod, G. Design and validation of a virtual reality trainer for ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2023, 78, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kockro, R.A.; Serra, L.; Tseng-Tsai, Y.; Chan, C.; Yih-Yian, S.; Gim-Guan, C.; Lee, E.; Hoe, L.Y.; Hern, N.; Nowinski, W.L. Planning and simulation of neurosurgery in a virtual reality environment. Neurosurgery 2000, 46, 118–135, discussion 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohlweg-Majert, B.; Schön, R.; Schmelzeisen, R.; Gellrich, N.C.; Schramm, A. Navigational maxillofacial surgery using virtual models. World J. Surg. 2005, 29, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.S.; Tang, W.J.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, Z.G.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, L.F. Virtual reality presurgical planning for cerebral gliomas adjacent to motor pathways in an integrated 3-D stereoscopic visualization of structural MRI and DTI tractography. Acta Neurochir. 2010, 152, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Ryu, J.J.; Nam, E.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.K. Effects of Preoperative Virtual Reality Magnetic Resonance Imaging on Preoperative Anxiety in Patients Undergoing Arthroscopic Knee Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Study. Arthroscopy 2019, 35, 2394–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, M.; Gabl, M.; Gruber, H.; Jaschke, W.R.; Mallouhi, A. CT virtual reality in the preoperative workup of malunited distal radius fractures: Preliminary results. Eur. Radiol. 2005, 15, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).