Colpocleisis—Still a Valuable Option: A Point of Technique

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surgical Procedure of the Modified LFC with Purse-String Sutures

- (1)

- Placement of a 16-gauge indwelling catheter.

- (2)

- Two identical vertical rectangles are marked anteriorly and posteriorly, closely from the apex to the vaginal introitus, but not further than 3 cm from the meatus urethrae externus. These rectangles should be approximately 3 cm apart, which corresponds to the urethrovesical junction. The suburethral part is not excised in anticipation of the need for a future tension-free vaginal tape in case of stress urinary incontinence.

- (3)

- The vagina is infiltrated with saline or a local anaesthetic. This step helps to separate the epithelium from the endopelvic fascia and optimise dissection.

- (4)

- Denudation of the rectangles. Only the epithelium should be excised in order to conserve as much of the endopelvic fascia as possible. Careful haemostasis is applied using bipolar forceps and tampons.

- (5)

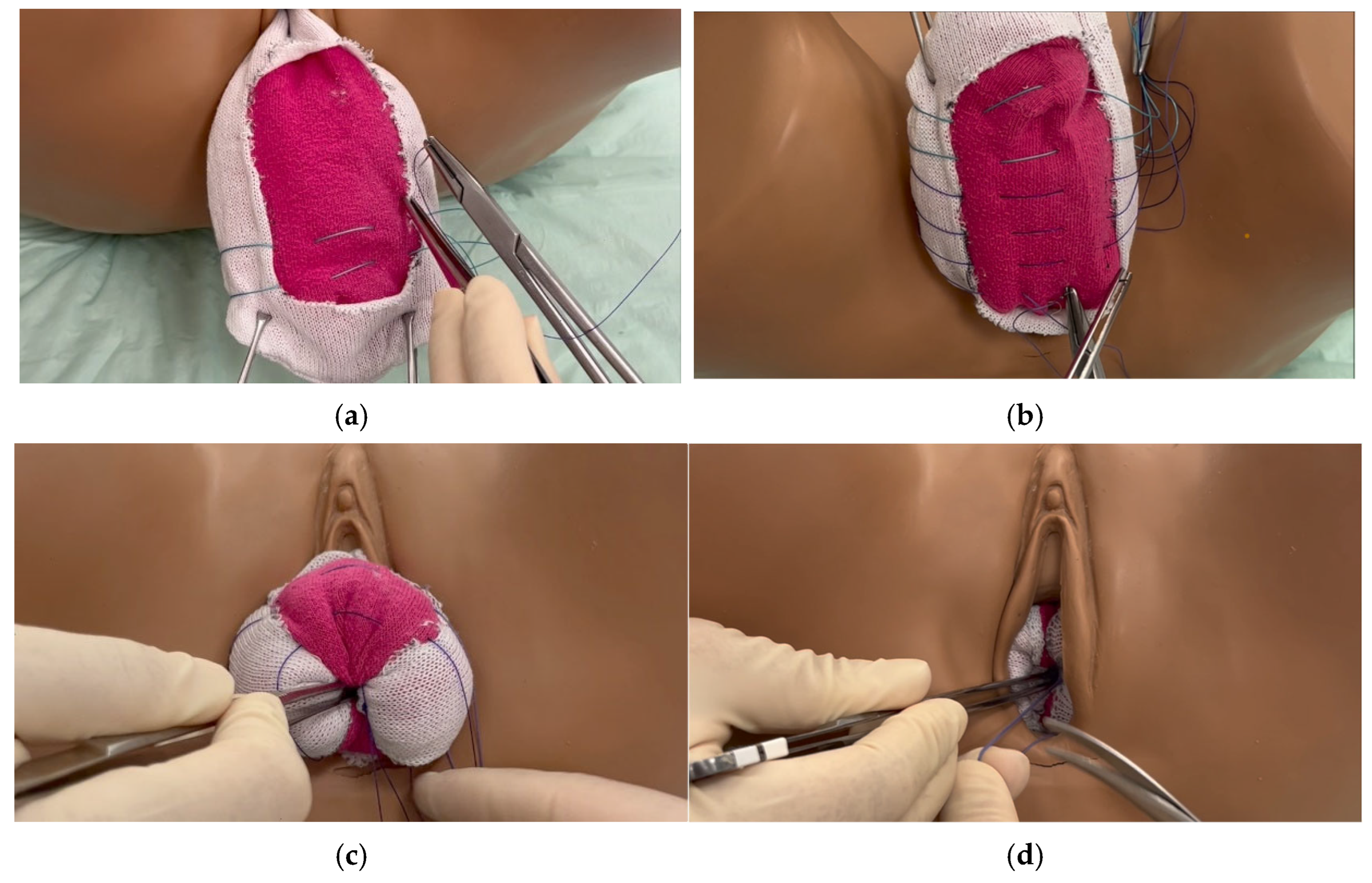

- Close the vagina using purse-string sutures running from the right border to the left border of the anterior part of the rectangle, and then from the left border to the right border of the posterior part of the rectangle (Figure 1a,b). The first suture, made of non-absorbable thread, Ethibond® Excel 2-0 (Polyester; Ethicon, LLC., Somerset County, NJ, USA), is placed at the distal end of the cervix. Depending on the length of the vagina, another suture can be placed 1 cm apart to ensure stability. In extensive urogenital atrophy with thin endopelvic fascia, absorbable sutures are used to avoid perforation.

- (6)

- Further sutures with PDS™ II 2-0 (polydioxanone; 2-0 Ethicon, Somerset County, NJ, USA) are placed in the same manner, approximately 1 cm apart. The sutures must be placed deep in the tissue to ensure stability. The position of the sutures should not be too close together to avoid difficulty in knotting, nor should they be too far apart for stability reasons. Distally, fast-resorbable sutures Vicryl® 2-0 (Polyglactin 910; Ethicon, Somerset County, NJ, USA) are used. A total of 5–10 sutures will be placed according to the length of the vagina.

- (7)

- The most apical, and therefore distal, suture will be knotted first. The vagina will be inverted by applying pressure to the tissue with a blunt instrument (Figure 1c) and bringing the anterior and posterior parts together. All sutures will be knotted from distally to proximally. At the end, the vagina will be completely inverted (Figure 1d).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barber, M.D. Measuring Pelvic Organ Prolapse: An Evolution. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2024, 35, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perucchini, D.; DeLancey, J.O.; Ashton-Miller, J.A.; Peschers, U.; Kataria, T. Age effects on urethral striated muscle. I. Changes in number and diameter of striated muscle fibers in the ventral urethra. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, D.; Mohr, S.; Nowakowski, L.; Mueller, M.D.; Kuhn, A. A prospective cohort trial evaluating sexual function after urethral diverticulectomy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 272, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bump, R.C.; Mattiasson, A.; Bø, K.; Brubaker, L.P.; DeLancey, J.O.; Klarskov, P.; Shull, B.L.; Smith, A.R. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 175, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, A.; Bapst, D.; Stadlmayr, W.; Vits, K.; Mueller, M.D. Sexual and organ function in patients with symptomatic prolapse: Are pessaries helpful? Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 1914–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque Coelho, S.C.; Brito, L.G.O.; de Araujo, C.C.; Juliato, C.R.T. Factors associated with unsuccessful pessary fitting in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: Systematic review and metanalysis. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2020, 39, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.M.; Matthews, C.A.; Conover, M.M.; Pate, V.; Jonsson Funk, M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, K. The surgical anatomy of the vaginaefixatio sacrospinalis vaginalis. A contribution to the surgical treatment of vaginal blind pouch prolapse. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1968, 28, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, H.A.; Tomeszko, J.E.; Sand, P.K. Anterior sacrospinous vaginal vault suspension for prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 95, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFort, L. Novel procedure for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Bull Gene Ther. 1877, 92, 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- LA, N. Einige Worte über die mediale Vaginalnaht als Mittel zur Beseitigung des Gebärmuttervorfalls. Zentralbl Gynaekol 1881, 3, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorflinger, A.; Monga, A. Voiding dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 13, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L.; Fall, M.; Griffiths, D.; Rosier, P.; Ulmsten, U.; van Kerrebroeck, P.; Victor, A.; Wein, A.; Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002, 21, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.J.; Walters, M.D.; Unger, C.A. Perioperative adverse events associated with colpocleisis for uterovaginal and posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 501.e1–501.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.M.; Zhang, M.X.; Zhao, L.; Han, B.; Xu, P.; Xue, M. The Starling mechanism of the urinary bladder contractile function and the influence of hyperglycemia on diabetic rats. J Diabetes Complicat. 2010, 24, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villiger, A.S.; Hoehn, D.; Ruggeri, G.; Vaineau, C.; Nirgianakis, K.; Imboden, S.; Kuhn, A.; Mueller, M.D. Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodker, B.; Lose, G. Postoperative urinary retention in gynecologic patients. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2003, 14, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, M.; Manodoro, S.; Cola, A.; Palmieri, S.; Spelzini, F.; Milani, R. Risk factors for persistent, de novo and overall overactive bladder syndrome after surgical prolapse repair. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 233, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakatta, E.G. Arterial and cardiac aging: Major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part III: Cellular and molecular clues to heart and arterial aging. Circulation 2003, 107, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Ao, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Peng, L.; Chen, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, T. Efficacy and safety of Le Fort colpocleisis in the treatment of stage III-IV pelvic organ prolapse. BMC Women′s Health 2024, 24, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerbak-Andersen, M.; Klarskov, N.; Husby, K.R. Colpocleisis: Reoperation risk and risk of uterine and vaginal cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023, 34, 2495–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Hu, C.; Hua, K. Relationship of advanced glycation end products and their receptor to pelvic organ prolapse. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 2288–2299. [Google Scholar]

- Fessel, G.; Li, Y.; Diederich, V.; Guizar-Sicairos, M.; Schneider, P.; Sell, D.R.; Monnier, V.M.; Snedeker, J.G. Advanced glycation end-products reduce collagen molecular sliding to affect collagen fibril damage mechanisms but not stiffness. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, B.L.; Popiel, P.; Toaff, M.C.; Drugge, E.; Bielawski, A.; Sacks, A.; Bibi, M.; Friedman-Ciment, R.; LeBron, K.; Alishahian, L.; et al. Permanent Compared With Absorbable Suture in Apical Prolapse Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall n = 88 | LFC n = 49 | TC n = 39 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |||

| Age at Surgery (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 82 ± 7 | 84 ± 7 | 80 ± 6.5 |

| Age > 80 n (%) | 56 (64%) | 36 (73%) | 20 (51%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) Mean ± SD | 24.6 ± 4.8 | 24.7 ± 4.9 | 24.4 ± 4.7 |

| Diabetes—Yes n (%) | 14 (16%) | 8 (16%) | 6 (15%) |

| Number of Deliveries a Mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 2.0 |

| Smoker—Yes a n (%) | 4 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Previous Prolapse Surgery—Yes n (%) | 42 (48%) | 16 (33%) | 26 (67%) |

| Additional Surgery—Yes n (%) | 37 (42%) | 19 (39%) | 18 (46%) |

| Residual Urine—Yes—n (%) a | 39 (45%) | 22 (47%) | 17 (44%) |

| Catheter—Yes n (%) a | 16 (18%) | 9 (19%) | 7 (18%) |

| Incontinence—n (%) | |||

| None | 45 (51%) | 24 (50%) | 20 (51%) |

| Stress | 14 (16%) | 9 (19%) | 5 (13%) |

| Overactive | 9 (10%) | 5 (10%) | 4 (10%) |

| Mixed | 20 (23%) | 10 (21%) | 10 (26%) |

| POP-Q Score Baseline | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| 0—n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1—n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2—n (%) | 4 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (5%) |

| 3—n (%) | 35 (40%) | 20 (41%) | 15 (38%) |

| 4—n (%) | 49 (56%) | 27 (55%) | 22 (56%) |

| Surgery Summary | |||

| Surgery Time (mins) a Mean ± SD | 94 ± 38 | 84 ± 34 | 107 ± 41 |

| Anaesthesia Type n (%) | |||

| Spinal | 27 (31%) | 19 (39%) | 8 (21%) |

| General | 56 (64%) | 27 (55%) | 29 (74%) |

| Peridural | 2 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) |

| Local | 3 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (3%) |

| Thread Type n (%) *a | |||

| Absorbable and Non-Absorbable | 62 (77%) | 27 (63%) | 35 (92%) |

| Absorbable Only | 19 (23%) | 16 (37%) | 3 (8%) |

| Additional Surgery—Yes n (%) | 37 (42%) | 19 (39%) | 18 (46%) |

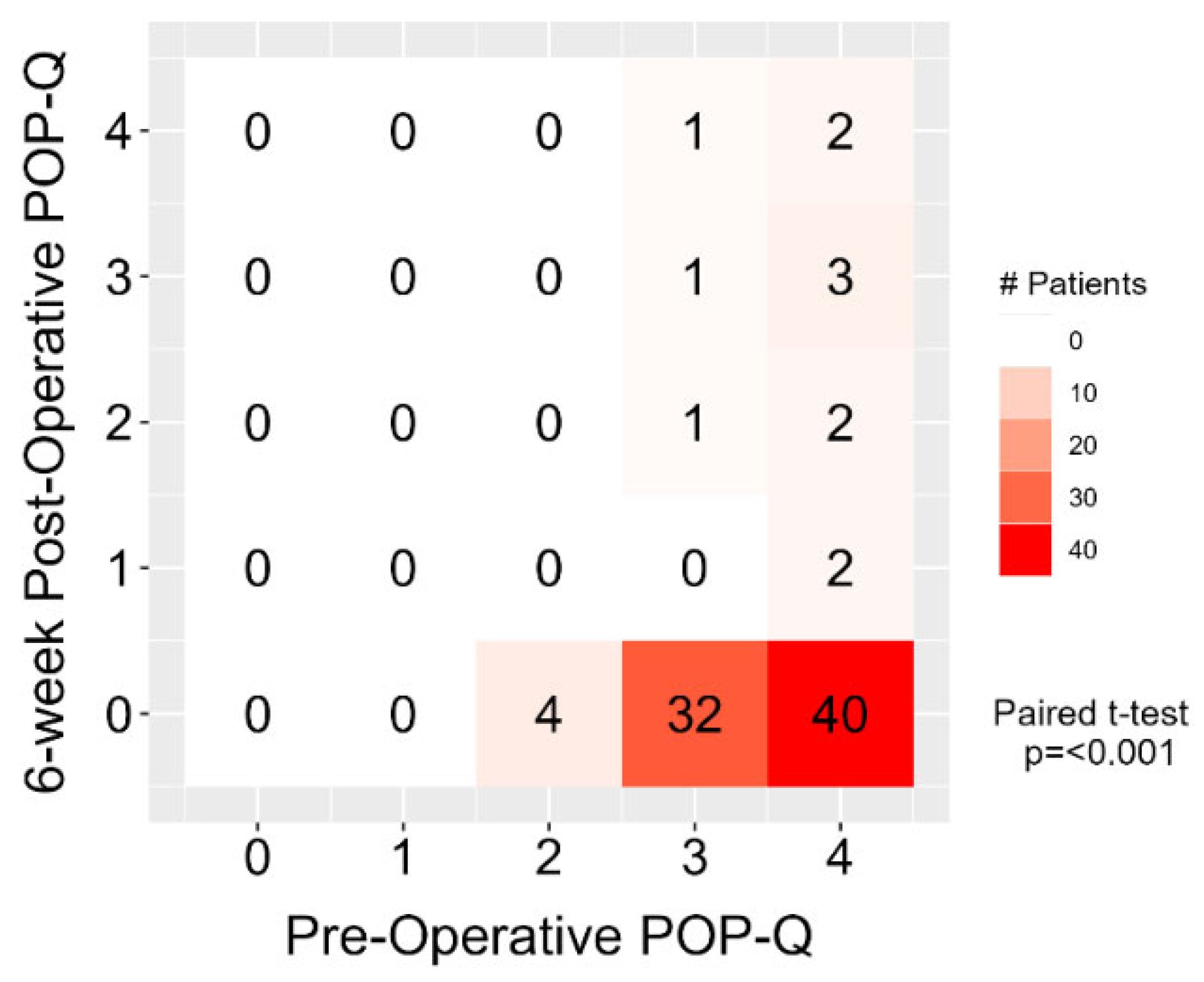

| Metric | Baseline | 6 Weeks Post-Surgery | Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POP-Q Stage (6 weeks) | n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | Adj. Difference [p-value] |

| All Patients | 88 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 88 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | −3.2 (−3.4, −3.0) [<0.001] a |

| Le-Fort Colpocleisis | 49 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 49 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.3 (−0.2, 0.7) [0.21] b |

| Total Colpocleisis | 39 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 39 | 0.5 ± 1.2 | |

| No Previous Prolapse Surgery | 46 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 46 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.5 (0.1, 0.9) [0.02] b |

| Previous Prolapse Surgery | 42 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 42 | 0.6 ± 1.3 | |

| Absorbable Threads Only | 19 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 19 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.0 (−0.5, 0.5) [0.9] b |

| Non-Absorbable and Absorbable Threads | 62 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 62 | 0.3 ± 0.9 | |

| Patients with No Previous Prolapse Surgery c | |||||

| Le-Fort Colpocleisis | 33 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 33 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.2) [0.24] b |

| Total Colpocleisis | 13 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 13 | 0 ± 0 | |

| Patients with Previous Prolapse Surgery c | |||||

| Le-Fort Colpocleisis | 16 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 16 | 0.3 ± 1 | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.2) [0.30] b |

| Total Colpocleisis | 26 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 26 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | |

| Residual Urine—Yes n (%) | n = 86 | n = 78 | Adj. Difference [p-value] | ||

| All Patients | 39 (45%) | 14 (18%) | [<0.001] d | ||

| Le-Fort Colpocleisis | 22 (47%) | 5 (12%) | 3.1 (0.8, 12.3) [0.10] e | ||

| Total Colpocleisis | 17 (44%) | 9 (25%) | |||

| No Previous Prolapse Surgery | 18 (40%) | 4 (11%) | 2.7 (0.8, 11.6) [0.14] e | ||

| Previous Prolapse Surgery | 21 (51%) | 10 (24%) | |||

| Incontinence n (%) | n = 88 | n = 80 | [p-value] | ||

| No Incontinence | 45 (51%) | 61 (76%) | [<0.001] d | ||

| Incontinence | 43 (49%) | 19 (24%) | |||

| Metric | Summary | Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|

| POP-Q Stage (Last Follow-Up) a | n | Mean ± SD | Adj. Difference [p-value] b |

| Baseline | 51 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | −3.0 (−3.3, −2.7) [<0.001] (Follow-up to Baseline) |

| 6-Week Post Surgery | 51 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | |

| Last Follow-up Visit (days) Median, IQR (73, 452) | 51 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | |

| Recurrence Rate—% | n | n (%) | Adj. Difference [p-value] c |

| All patients | 88 | 14 (16%) | - |

| Le-Fort Colpocleisis | 49 | 5 (10%) | 2.4 (0.8, 8.7) [0.15] |

| Total Colpocleisis | 39 | 9 (23%) | |

| No Previous Prolapse Surgery | 46 | 3 (7%) | 5.4 (1.5, 26.8) [0.02] |

| Previous Prolapse Surgery | 42 | 11 (26%) | |

| Absorbable Threads Only | 19 | 3 (16%) | 0.9 (0.2, 4.5) [0.89] |

| Non-Absorbable and Absorbable Threads | 62 | 9 (15%) | |

| No Diabetes | 74 | 9 (12%) | 4.0 (1.0, 14.8) [0.04] |

| Diabetes | 14 | 5 (36%) | |

| Age ≤ 80 | 32 | 5 (16%) | 1.2 (0.4, 4.6) [0.76] |

| Age > 80 | 56 | 9 (16%) | |

| Deliveries ≤ 2 | 39 | 8 (21%) | 0.8 (0.2, 2.5) [0.65] |

| Deliveries > 2 | 41 | 5 (12%) | |

| Non-Smoker | 80 | 14 (18%) | - d |

| Smoker | 4 | 0 (0%) | |

| BMI < 25 | 52 | 9 (17%) | 0.6 (0.2, 2.0) [0.40] |

| BMI ≥ 25 | 36 | 5 (14%) | |

| Incontinence at Baseline | Improving After Surgery n (%) | Worsening After Surgery n (%) | No Change n (%) | No Follow-Up Test n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Incontinence (n = 45) | - | 3 (7%) | 40 (89%) | 2 (4%) |

| Stress Incontinence (n= 14) | 6 (43%) | 1 (7%) | 4 (29%) | 3 (21%) |

| Urge Incontinence (n = 9) | 4 (44%) | 1 (11%) | 3 (33%) | 1 (11%) |

| Mixed Incontinence (n = 20) | 17 (85%) | - | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) |

| LFC | TC | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 5) | Patients (n = 8) | ||

| Grade I | |||

| 0 | 1 | surveillance |

| Grade II | |||

| 3 | 4 | antibiotics |

| 0 | 1 | antibiotics |

| 1 | 1 | transfusion |

| Grade III | |||

| Grade IIIa | |||

| 1 | 0 | indwelling catheter |

| Grade IIIb | |||

| 0 | 1 | revision |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoehn, D.; Egli, H.; Marak, M.C.; Ryu, G.; Villiger, A.-S.; Ruggeri, G.; Mueller, M.D.; Kuhn, A. Colpocleisis—Still a Valuable Option: A Point of Technique. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207433

Hoehn D, Egli H, Marak MC, Ryu G, Villiger A-S, Ruggeri G, Mueller MD, Kuhn A. Colpocleisis—Still a Valuable Option: A Point of Technique. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207433

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoehn, Diana, Hannes Egli, Martin Chase Marak, Gloria Ryu, Anna-Sophie Villiger, Giovanni Ruggeri, Michael David Mueller, and Annette Kuhn. 2025. "Colpocleisis—Still a Valuable Option: A Point of Technique" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207433

APA StyleHoehn, D., Egli, H., Marak, M. C., Ryu, G., Villiger, A.-S., Ruggeri, G., Mueller, M. D., & Kuhn, A. (2025). Colpocleisis—Still a Valuable Option: A Point of Technique. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207433