Antidiabetic Agents as Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Therapies in Neurological and Cardiovascular Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neuro-Cardiovascular Pathology

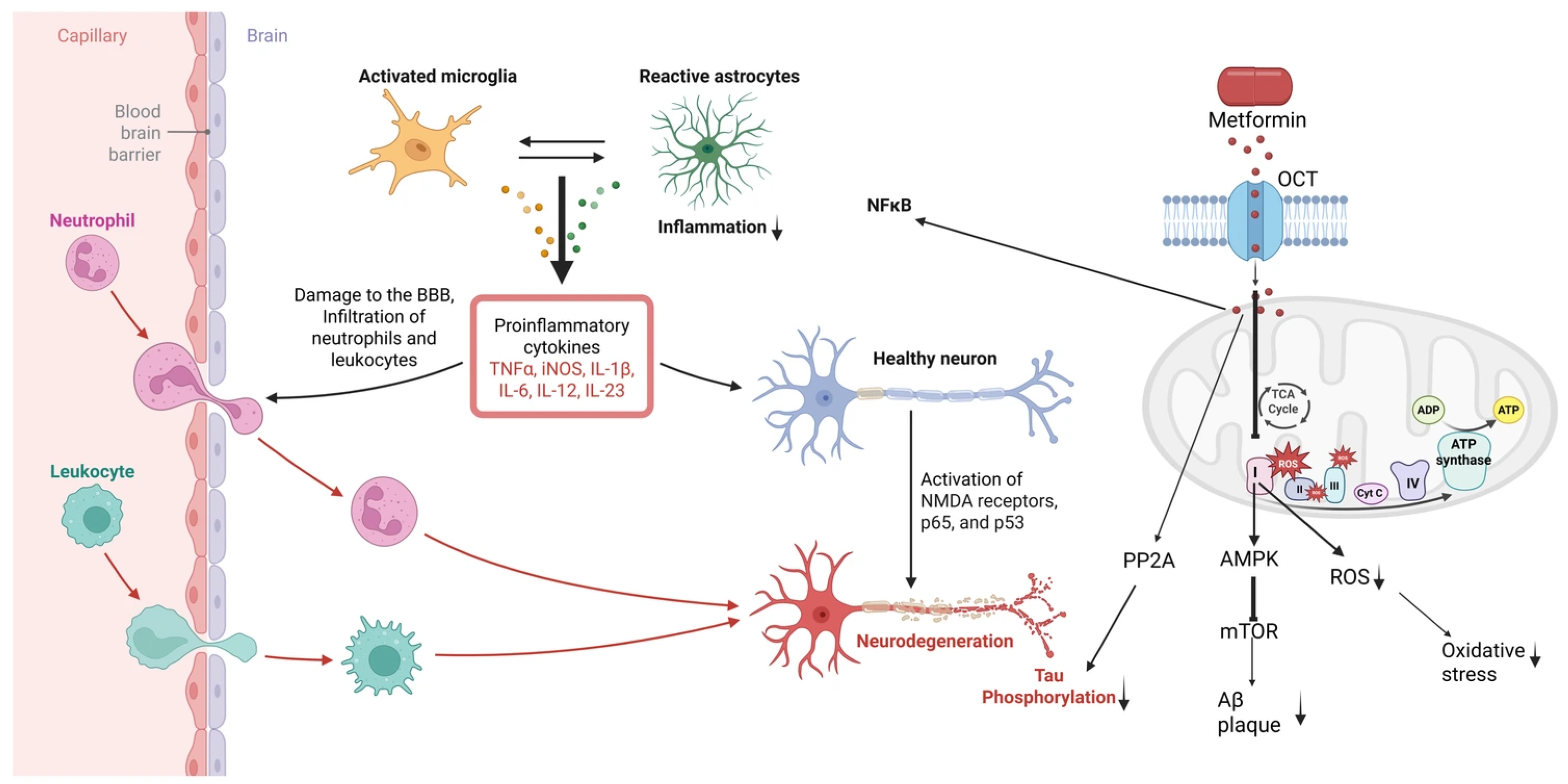

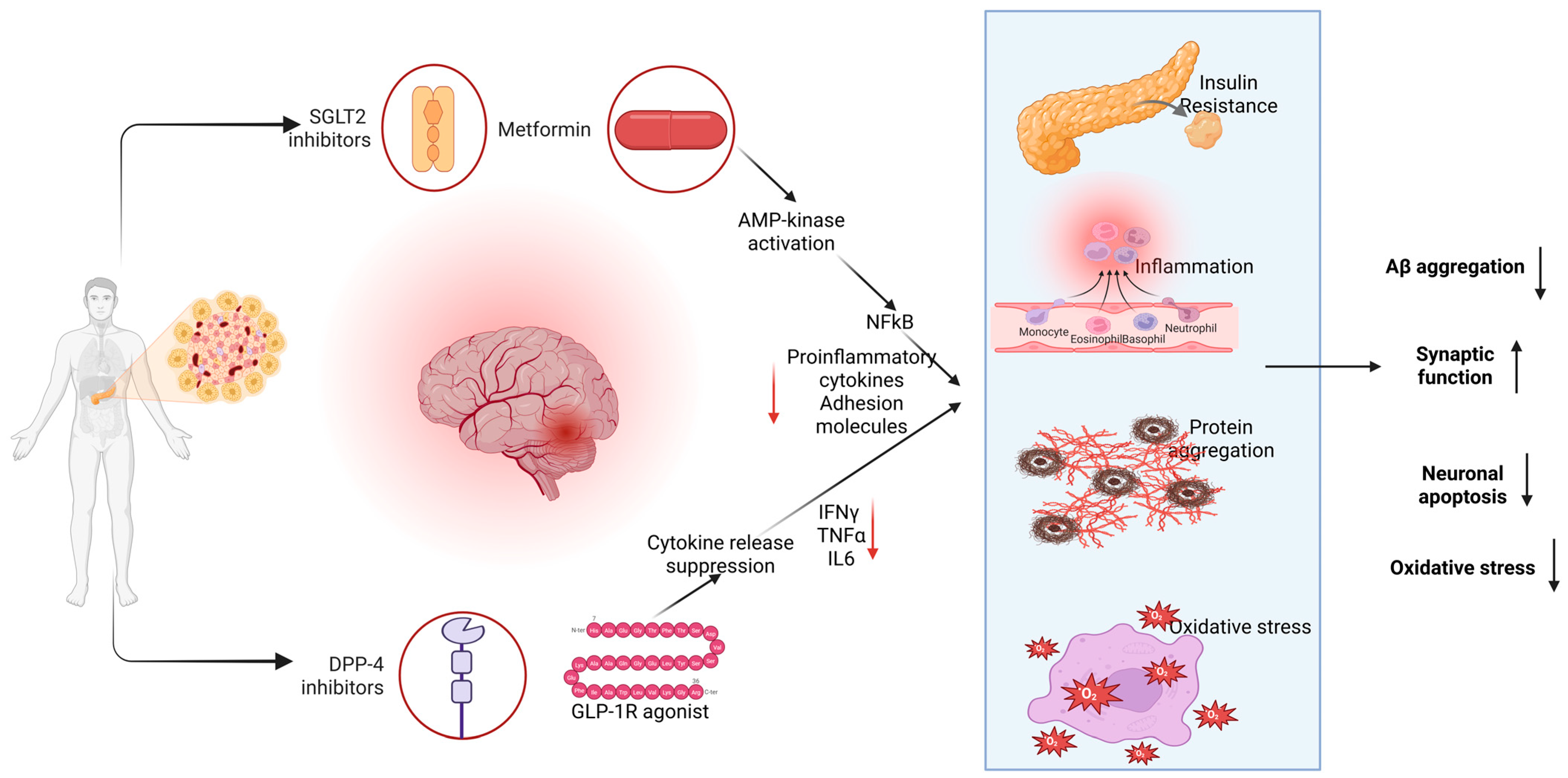

2.1. Metformin: AMPK-Mediated Anti-Inflammatory/Antioxidant Actions

2.1.1. Preclinical Neurological Evidence

2.1.2. Clinical Data

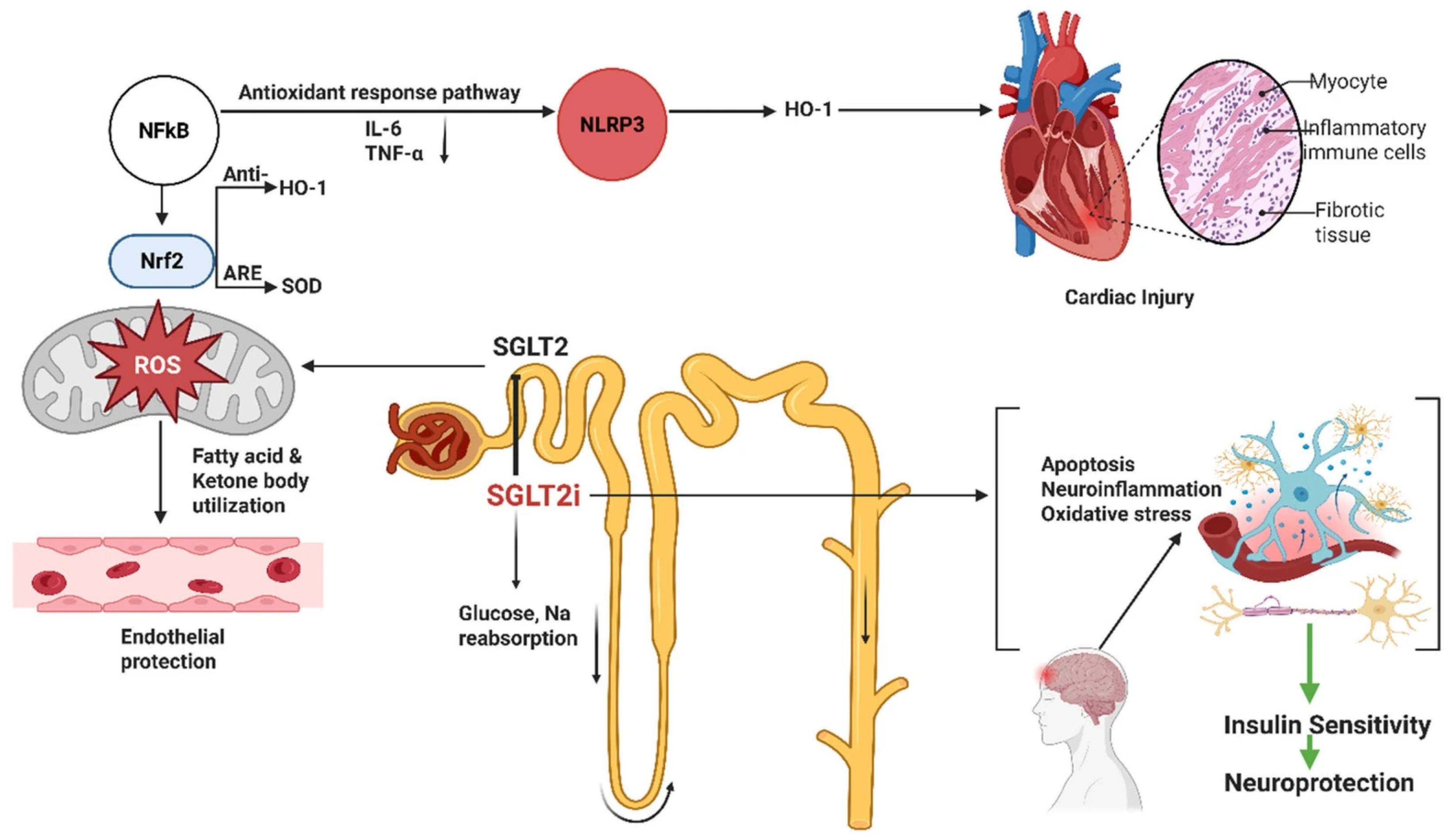

2.2. Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors

2.2.1. Mechanisms

2.2.2. Preclinical Findings

2.2.3. Clinical Evidence

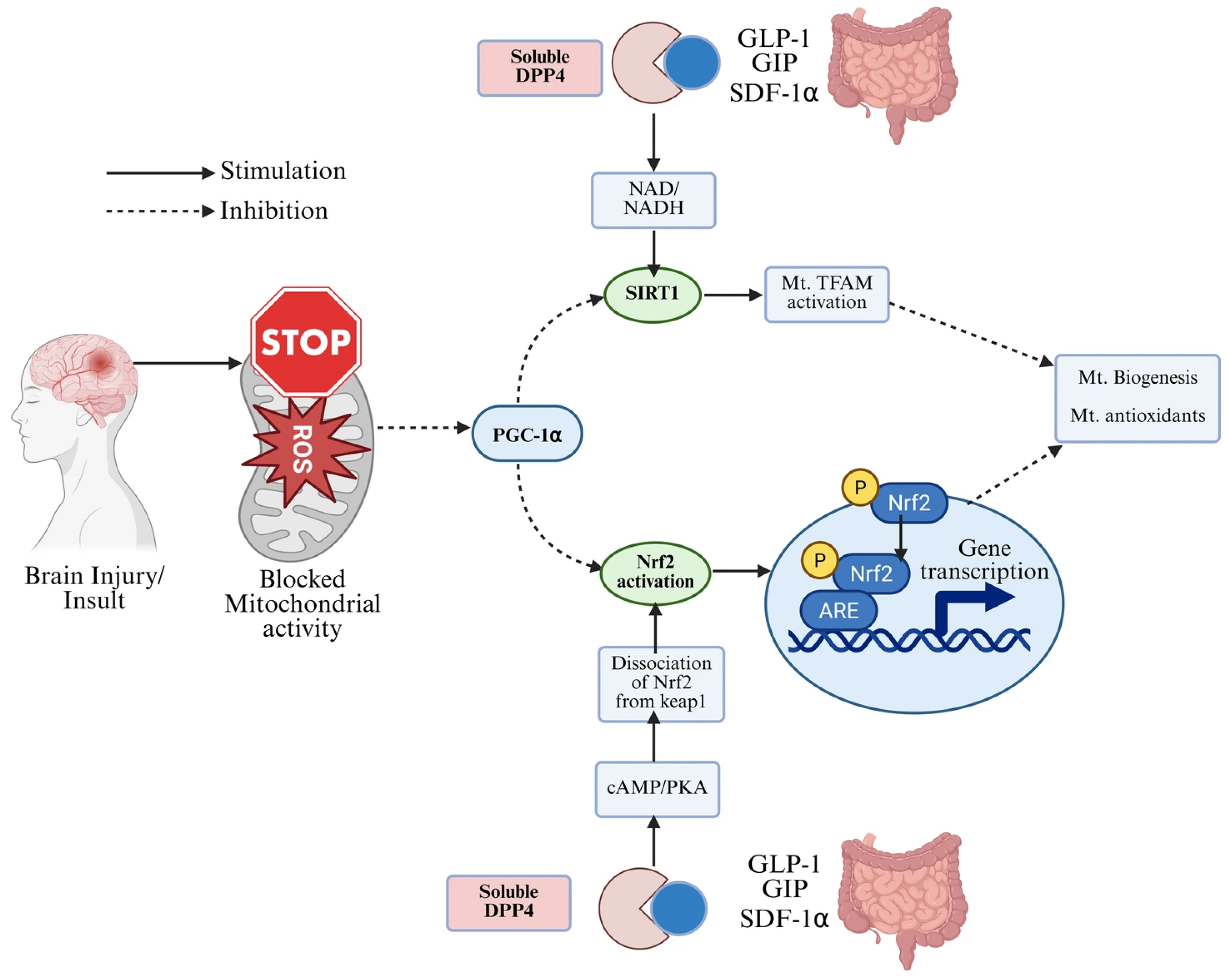

2.3. DPP-4 Inhibitors

2.3.1. Neurological Effects

2.3.2. Clinical Studies

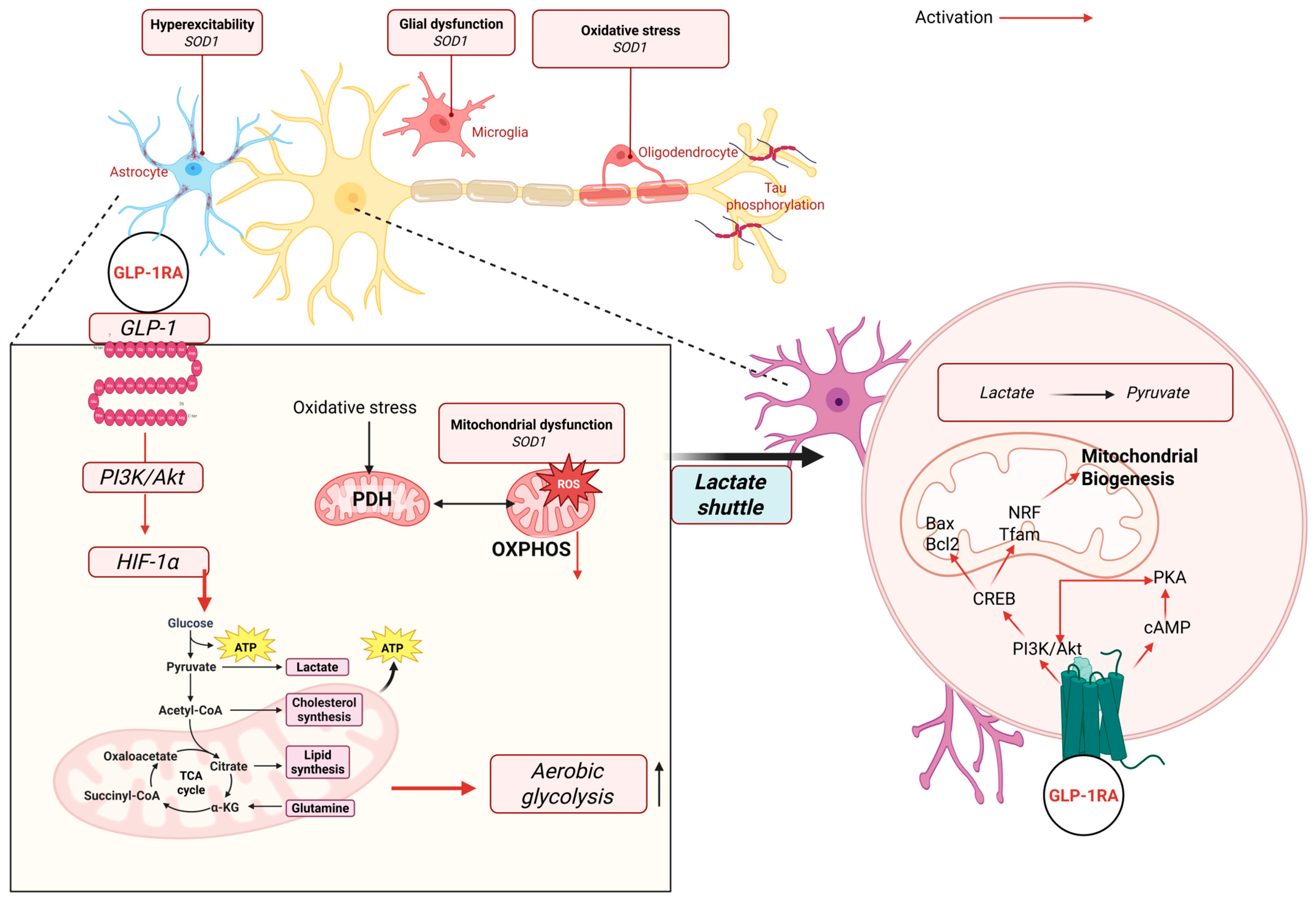

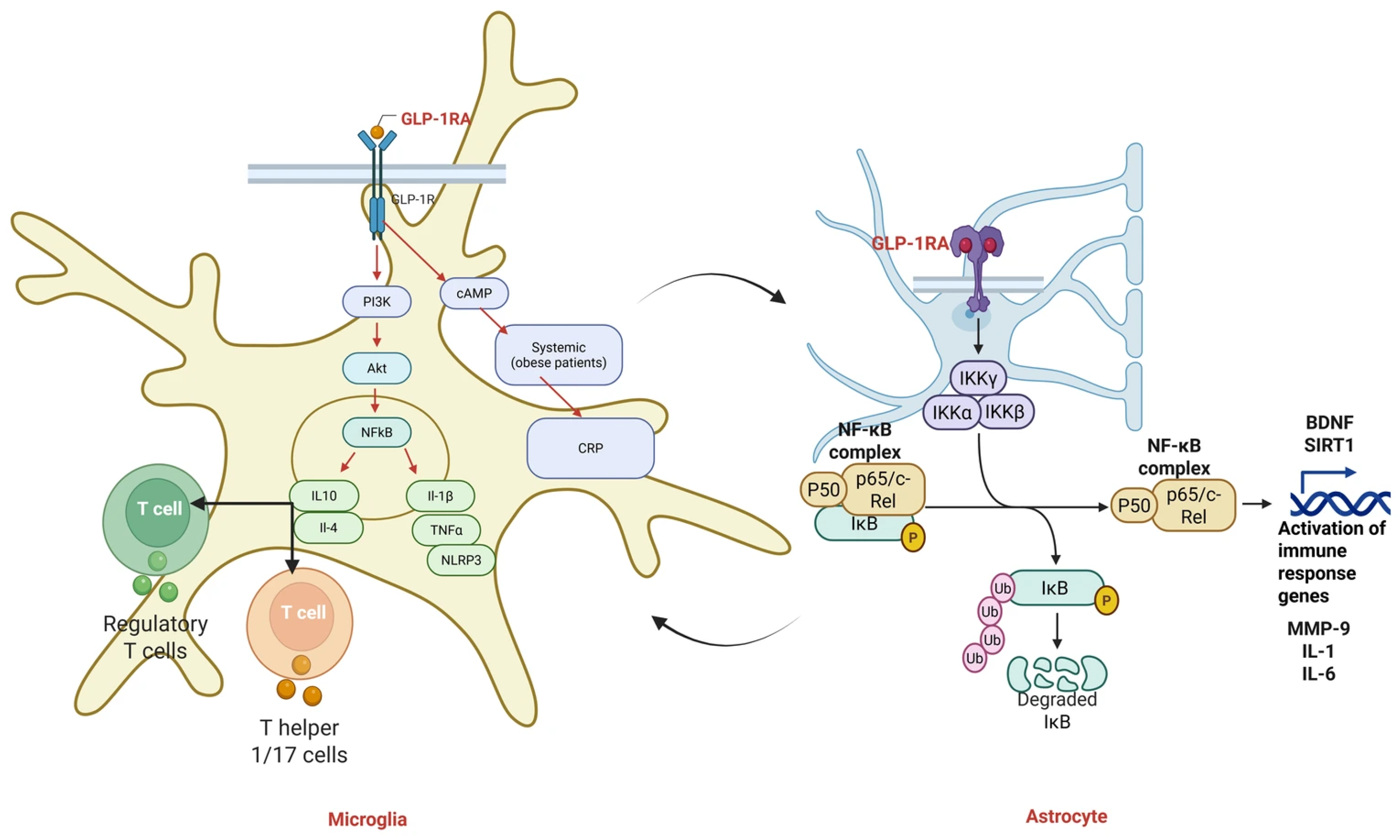

2.4. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

2.4.1. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Mechanisms of GLP-1 Receptor

2.4.2. Preclinical Neuroprotection

2.4.3. Cardiovascular and Stroke Effects

2.4.4. Clinical Studies in Neurology

3. Therapeutic Opportunities in Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Disorders

3.1. Neuroinflammation

3.2. Neurodegeneration (AD/PD)

3.3. Ischemic Stroke

3.4. Cardiovascular Disease: Atheroprotection and Heart Failure

3.4.1. Atherosclerosis

3.4.2. Heart Failure and Myocardial Injury

3.4.3. Clinical Trials

4. Future Directions and Emerging Therapies

5. Implications for Longevity and Healthy Aging

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Chen, W.W.; Zhang, X.; Huang, W.J. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 3391–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, S.; Frenis, K.; Oelze, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Kuntic, M.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Helmstädter, J.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; et al. Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Major Triggers for Cardiovascular Disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7092151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, U.C.; Bhol, N.K.; Swain, S.K.; Samal, R.R.; Nayak, P.K.; Raina, V.; Panda, S.K.; Kerry, R.G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. Oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders: Mechanisms and implications. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.L.; Zecca, L.; Hong, J.-S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: Uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madamanchi, N.R.; Vendrov, A.; Runge, M.S. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rena, G.; Hardie, D.G.; Pearson, E.R. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, K.A.; Sharma, S.; Sifat, A.E.; Zhang, Y.; Patel, D.K.; Cucullo, L.; Abbruscato, T.J. Metformin ameliorates neuroinflammatory environment for neurons and astrocytes during in vitro and in vivo stroke and tobacco smoke chemical exposure: Role of Nrf2 activation. Redox Biol. 2024, 75, 103266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, M.; Pasbakhsh, P.; Shabani, M.; Nekoonam, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Fathi, F.; Abouzaripour, M.; Mohamed, W.; Zibara, K.; Kashani, I.R.; et al. Metformin therapy attenuates pro-inflammatory microglia by inhibiting NF-κB in cuprizone demyelinating mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 1732–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, K. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling modulates microglial activation and neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2016, 13, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Yan, B.; Yoo, K.Y. Anti-inflammatory properties of GLP-1 receptor signaling in microglia. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A.R.; Morrison, V.L.; Levin, D.; Mohan, M.; Forteath, C.; Beall, C.; McNeilly, A.D.; Balfour, D.J.K.; Savinko, T.; Wong, A.K.F.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of metformin irrespective of diabetes status. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y.; Meschiari, C.A.; Jung, M.; Lindsey, M.L. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Myocardial Infarction and Heart Failure. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017, 147, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaddagh, A.; Martin, S.S.; Leucker, T.M.; Michos, E.D.; Blaha, M.J.; Lowenstein, C.J.; Jones, S.R.; Toth, P.P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, D.; Mao, Q.; Xia, H. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uruk, G.; Mocanu, E.; Shaw, A.E.; Bamburg, J.R.; Swanson, R.A. Cofilactin rod formation mediates inflammation-induced neurite degeneration. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.; Li, S.; Gao, F.; Xue, G. The role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases: Current understanding and future therapeutic targets. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1347987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Yamada, N. GLP-1 receptor activation preserves blood-brain barrier integrity after ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2014, 34, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Hölscher, C. GLP-1 receptor agonists as neuroprotective agents: A systematic review. Trends Neurosci. 2020, 43, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Perry, T.; Kindy, M.S.; Harvey, B.K.; Tweedie, D.; Holloway, H.W.; Powers, K.; Shen, H.; Egan, J.M.; Sambamurti, K.; et al. GLP-1 receptor stimulation preserves neurons in cellular and rodent models of stroke and Parkinsonism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaisar, M.A.; Villalba, H.; Prasad, S.; Liles, T.; Sifat, A.E.; Sajja, R.K.; Abbruscato, T.J.; Cucullo, L. Offsetting the impact of smoking and e-cigarette vaping on the cerebrovascular system and stroke injury: Is Metformin a viable countermeasure? Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascolo, A.; Scavone, C.; Scisciola, L.; Chiodini, P.; Capuano, A.; Paolisso, G. SGLT-2 inhibitors reduce the risk of cerebrovascular/cardiovascular outcomes and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of retrospective cohort studies. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 172, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.K.; Ibrahim, R.; Mee, X.C.; Abdelnabi, M.; Pham, H.N.; Habib, E.; Farina, J.; Lee, J.Z.; Lester, S.J.; Scott, L.; et al. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors and Stroke Risk in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2025, 36, 1826–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Katsiki, N.; Butler, A.E.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of antidiabetic drugs on NLRP3 inflammasome activity, with a focus on diabetic kidneys. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mir, M.Y.; Nogueira, V.; Fontaine, E. Metformin activates AMPK through inhibition of mitochondrial complex I. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoda, K.; Young, J.L.; Zirlik, A.; MacFarlane, L.A.; Tsuboi, N.; Gerdes, N.; Schönbeck, U.; Libby, P. Metformin inhibits proinflammatory responses and nuclear factor-κB in human vascular wall cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, W.A.; Law, R.E. Metformin improves vascular function through KLF2-dependent mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 1126–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Sena, C.M.; Matafome, P.; Louro, T.; Nunes, E.; Fernandes, R.; Seica, R.M. Metformin restores endothelial function in aorta of diabetic rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Xie, F.; Xiao, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhong, J.; Huang, D.; Chen, J.; Wei, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhong, T. Metformin: A Potential Candidate for Targeting Aging Mechanisms. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Aylor, K.W.; Chai, W.; Barrett, E.J.; Liu, Z. Metformin prevents endothelial oxidative stress and microvascular insulin resistance during obesity development in male rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 322, E293–E306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, R.; Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Pan, T.; Zhang, R.; Liu, B.; Chen, E.; Tang, Y.; Qu, H. Metformin ameliorates endotoxemia-induced endothelial pro-inflammatory responses via AMPK-dependent mediation of HDAC5 and KLF2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemgulyte, G.; Tanaka, S.; Hide, I.; Sakai, N.; Pampuscenko, K.; Borutaite, V.; Rastenyte, D. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Post-Stroke Metformin Treatment Using Permanent Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion in Rats. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Nemati, M.; Zandvakili, R.; Jafarzadeh, A. Modulation of M1 and M2 macrophage polarization by metformin: Implications for inflammatory diseases and malignant tumors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 151, 114345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venna, V.R.; Li, J.; Hammond, M.D.; Mancini, N.S.; McCullough, L.D. Chronic metformin treatment improves post-stroke angiogenesis and recovery after experimental stroke. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 2129–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Y.; Sheng, X.L.; Li, C.J.; Qin, T.; He, R.D.; Dai, G.Y.; Cao, Y.; Lu, H.B.; Duan, C.Y.; Hu, J.Z. Metformin promotes angiogenesis and functional recovery in aged mice after spinal cord injury by adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.; Kong, X.; Sun, X.; He, X.; Zhang, L.; Gong, Z.; Huang, J.; Xu, B.; Long, D.; Li, J.; et al. Metformin prevents amyloid plaque deposition and memory impairment in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Res. Bull. 2013, 96, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gallagher, D.; DeVito, L.M.; Cancino, G.I.; Tsui, D.; He, L.; Keller, G.M.; Frankland, P.W.; Kaplan, D.R.; Miller, F.D. Metformin activates atypical PKC-CBP pathway to enhance adult hippocampal neurogenesis via AMPK. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Myers, R.; Li, Y. Metformin mitigates mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal apoptosis after experimental traumatic brain injury via PI3K/Akt. Brain Res. 2016, 1642, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, E.A.B.; Livingston, J.; Flores, E.G.; Khan, M.; Kandavel, H.; Morshead, C.M. Metformin treatment reduces inflammation, dysmyelination and disease severity in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res. 2024, 1822, 148648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.R.; Gao, Q.Y.; Liu, C.L.; Bai, L.Y.; Li, T.; Wei, F.L. Exploring the Pharmacological Potential of Metformin for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 838173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Su, B.; Ahmadi-Abhari, S.; Kapogiannis, D.; Tzoulaki, I.; Riboli, E.; Middleton, L. Dementia risk in patients with type 2 diabetes: Comparing metformin with no pharmacological treatment. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 5681–5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Hao, J.; Tao, F.; Feng, Q.; Song, Y.; Zeng, B. Association of Metformin use with risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 1992–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderami, A.; Shariati, B.; Zarghami, M.; Aliasgharian, A.; Ghazaiean, M.; Darvishi-Khezri, H. Metformin and Cognitive Performance in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: An Umbrella Review. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2025, 45, e12528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, Y.; Sohn, J.H.; Sung, J.H.; Han, S.W.; Lee, M.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.J.; Mo, H.J.; Yu, K.H.; et al. Effects of Prior Metformin Use on Stroke Outcomes in Diabetes Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Receiving Endovascular Treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, J.R.; Rossing, P.R.; Campbell, I.W. Metformin and cardiorenal outcomes in diabetes: A reappraisal. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020, 22, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, T.; Galiero, R.; Caturano, A.; Vetrano, E.; Rinaldi, L.; Coviello, F.; Di Martino, A.; Albanese, G.; Marfella, R.; Sardu, C.; et al. Effects of Metformin in Heart Failure: From Pathophysiological Rationale to Clinical Evidence. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Luo, F.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, J.; Zhu, J. Effect of metformin on the clinical outcomes of stroke in patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e092214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Taka, E.; Darling-Reed, S.; Soliman, K.F.A. Neuroprotective Effects of Metformin Through the Modulation of Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress. Cells 2025, 14, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.L.; Verma, S.; Braunwald, E. The DAPA-HF Trial: A Momentous Victory in the War against Heart Failure. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 847–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.R.; Zhu, F.Y.; Zhou, R. SGLT2 inhibitors for alleviating heart failure through non-hypoglycemic mechanisms. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1494882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopaschuk, G.D.; Verma, S. Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Benefits of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors: A State-of-the-Art Review. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Li, D.; Zhang, J. SGLT2 inhibition reduces markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2021, 12, 1669–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Steven, S.; Kuntic, M.; Munzel, T.; Daiber, A. Modern antidiabetic therapy by sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors against cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 77, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, I.; Karakuyu, N.F.; Karabacak, P.; Milletsever, A.; Kolay, O.; Baysal, G.; Asci, H. Effect of dapagliflozin on sepsis-induced kidney injury in a rat model: Modulation of the NLRP3 pathway. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2025, 47, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodzon-Norwicz, M.; Kogut, P.; Sowa-Kucma, M.; Gala-Bladzinska, A. What a Modern Physician Should Know About microRNAs in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Yan, B. Empagliflozin alleviates doxorubicin-induced myocardial injury by inhibiting RIP3-dependent TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 242 Pt 1, 117277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maik, M.; Ibtisam, M.; Sheikh, S.; Malik, M.; Ihsan, A.; Arham, M.; Haq, U.; Parveen, A. The Role of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Atherosclerosis: A Systematic Review. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2025, 15, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannarella, R.; Rubulotta, M.; Cannarella, V.; La Vignera, S.; Calogero, A.E. A holistic view of SGLT2 inhibitors: From cardio-renal management to cognitive and andrological aspects. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 138, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, M.E.; Helvaci, O.; Yildirim, T.; Merhametsiz, O.; Sezer, S. Potential Role of SGLT-2 Inhibitors in Improving Allograft Function and Reducing Rejection in Kidney Transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2025, 39, e70233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stielow, M.; Fijalkowski, L.; Alaburda, A.; Grzesk, G.; Grzesk, E.; Nowaczyk, J.; Nowaczyk, A. SGLT2 Inhibitors: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Outcomes in Cardiology and Diabetology. Molecules 2025, 30, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelsalam, R.M.; Hamam, H.W.; Eissa, N.M.; El-Sahar, A.E.; Essam, R.M. Empagliflozin Dampens Doxorubicin-Induced Chemobrain in Rats: The Possible Involvement of Oxidative Stress and PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-kappaB/TNF-alpha Signaling Pathways. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 3480–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa-Nguanmoo, P.; Tanajak, P.; Kerdphoo, S.; Jaiwongkam, T.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. SGLT2-inhibitor and DPP-4 inhibitor improve brain function via attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, inflammation, and apoptosis in HFD-induced obese rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 333, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedosugova, L.V.; Markina, Y.V.; Bochkareva, L.A.; Kuzina, I.A.; Petunina, N.A.; Yudina, I.Y.; Kirichenko, T.V. Inflammatory Mechanisms of Diabetes and Its Vascular Complications. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, G.; Basso, M.G.; Pennacchio, A.R.; Cocciola, E.; Pintus, C.; Cuffaro, M.; Profita, M.; Rizzo, G.; Sferruzza, M.; Tuttolomondo, A. The Potential Impact of SGLT2-I in Diabetic Foot Prevention: Promising Pathophysiologic Implications, State of the Art, and Future Perspectives-A Narrative Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.M.; Chang, N.C.; Lin, S.Z. Dapagliflozin, a selective SGLT2 Inhibitor, attenuated cardiac fibrosis by regulating the macrophage polarization via STAT3 signaling in infarcted rat hearts. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 104, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F. Empagliflozin improves cardiac function in rats with chronic heart failure. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinman, B.; Lachin, J.M.; Inzucchi, S.E. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, B.; Perkovic, V.; Mahaffey, K.W.; de Zeeuw, D.; Fulcher, G.; Erondu, N.; Shaw, W.; Law, G.; Desai, M.; Matthews, D.R.; et al. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Sabatine, M.S. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. Reply. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1881–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kober, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Belohlavek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, K.F.; Chen, Y.L.; Chiou, T.T.; Chu, T.H.; Li, L.C.; Ng, H.Y.; Lee, W.C.; Lee, C.T. Emergence of SGLT2 Inhibitors as Powerful Antioxidants in Human Diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Zhong, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Xiao, X. The effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on biomarkers of inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1045235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Qin, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, J. Effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on inflammatory markers and oxygen consumption in non-diabetic patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI: A parallel design single blind controlled trial. Heart Lung 2025, 73, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronka, M.; Krzeminska, J.; Mlynarska, E.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. The Influence of Lifestyle and Treatment on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Bea, S.; Ko, H.Y.; Kim, W.J.; Cho, Y.M.; Shin, J.Y. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors, Dulaglutide, and Risk for Dementia: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilis, P.; Sagris, M.; Oikonomou, E.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Siasos, G.; Tsioufis, K.; Tousoulis, D. The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Novel Antidiabetic Agents. Life 2022, 12, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myasoedova, V.A.; Bozzi, M.; Valerio, V.; Moschetta, D.; Massaiu, I.; Rusconi, V.; Di Napoli, D.; Ciccarelli, M.; Parisi, V.; Agostoni, P.; et al. Anti-Inflammation and Anti-Oxidation: The Key to Unlocking the Cardiovascular Potential of SGLT2 Inhibitors and GLP1 Receptor Agonists. Antioxidants 2023, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourris, K.C.; Yao, H.; Jerums, G.; Cooper, M.E.; Ekinci, E.I.; Coughlan, M.T. Can Targeting the Incretin Pathway Dampen RAGE-Mediated Events in Diabetic Nephropathy? Curr. Drug Targets 2016, 17, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.T.; Kabir, Y. Pathophysiological Links Between Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases: At the Biochemical and Molecular Levels. In Levels, Frontiers in Cardiovascular Drug Discovery; Bentham Science Publisher: Singapore, 2022; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sottero, B.; Gargiulo, S.; Russo, I.; Barale, C.; Poli, G.; Cavalot, F. Postprandial Dysmetabolism and Oxidative Stress in Type 2 Diabetes: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Med. Res. Rev. 2015, 35, 968–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, S.; Al-Harrasi, A. Macrophage modulation with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors: A new frontier for treating diabetic cardiomyopathy? World J. Diabetes 2024, 15, 1847–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlovic, K.T.; Anderluh, M.; Smelcerovic, A. Mechanisms of beneficial effects of DPP-4 inhibitors as a promising perspective for the prevention/treatment of the disruption of cardio-cerebrovascular homeostasis. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1642333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, J.; Yao, X.; Ding, H.; Gu, A.; Zhou, Z. Neuroprotective effects of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor on Alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1361651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicinski, M.; Gorski, K.; Walczak, M.; Wodkiewicz, E.; Slupski, M.; Pawlak-Osinska, K.; Malinowski, B. Neuroprotective Properties of Linagliptin: Focus on Biochemical Mechanisms in Cerebral Ischemia, Vascular Dysfunction and Certain Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirica, B.M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Braunwald, E.; Steg, P.G.; Davidson, J.; Hirshberg, B.; Ohman, P.; Frederich, R.; Wiviott, S.D.; Hoffman, E.B.; et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.B.; Cannon, C.P.; Heller, S.R.; Nissen, S.E.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Bakris, G.L.; Perez, A.T.; Fleck, P.R.; Mehta, C.R.; Kupfer, S.; et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.B.; Bethel, M.A.; Armstrong, P.W.; Buse, J.B.; Engel, S.S.; Garg, J.; Josse, R.; Kaufman, K.D.; Koglin, J.; Korn, S.; et al. Effect of Sitagliptin on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, N.; Yang, W.; Watada, H.; Ji, L.; Schnaidt, S.; Pfarr, E.; Okamura, T.; Johansen, O.E.; George, J.T.; von Eynatten, M.; et al. Linagliptin and cardiorenal outcomes in Asians with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established cardiovascular and/or kidney disease: Subgroup analysis of the randomized CARMELINA((R)) trial. Diabetol. Int. 2020, 11, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, S.H. Dapagliflozin suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome and improves cognition in diabetic rats. Neuropharmacology 2020, 162, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Maanvi; Kumari, S.; Deshmukh, R. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4(DPP4) inhibitors stride up the management of Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 939, 175426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Agathokleous, E.; Kapoor, R.; Dhawan, G.; Kozumbo, W.J.; Calabrese, V. Metformin-enhances resilience via hormesis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 71, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelde, F. Impact of DPP-4 Inhibitors in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure: An In-Depth Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, E.J. Extra-Glycemic Effects of Anti-Diabetic Medications: Two Birds with One Stone? Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 37, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cork, S.C.; Richards, J.E.; Holt, M.K.; Gribble, F.M.; Reimann, F.; Trapp, S. Distribution and characterisation of Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor expressing cells in the mouse brain. Mol. Metab. 2015, 4, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmstadter, J.; Frenis, K.; Filippou, K.; Grill, A.; Dib, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Pawelke, F.; Kus, K.; Kroller-Schon, S.; Oelze, M.; et al. Endothelial GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1) Receptor Mediates Cardiovascular Protection by Liraglutide In Mice With Experimental Arterial Hypertension. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mei, A.; Wei, Y.; Li, C.; Qian, H.; Min, X.; Yang, H.; Dong, L.; Rao, X.; Zhong, J. GLP-1 receptor agonist as a modulator of innate immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 997578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Dong, N.; Min, X.; Liu, X.; Yu, Q.; Yuan, K.; Yue, H.; et al. GLP-1 analogue liraglutide attenuates CIH-induced cognitive deficits by inhibiting oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis via the Nrf2/HO-1 and MAPK/NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 142 Pt B, 113222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.S.; Jun, H.S. Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 on Oxidative Stress and Nrf2 Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Liu, M.; Lu, Z.; Hu, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Cai, F.; et al. Activation of AMPK by GLP-1R agonists mitigates Alzheimer-related phenotypes in transgenic mice. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urkon, M.; Ferencz, E.; Szasz, J.A.; Szabo, M.I.M.; Orban-Kis, K.; Szatmari, S.; Nagy, E.E. Antidiabetic GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Have Neuroprotective Properties in Experimental Animal Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, S.F.; Pusapati, S.; Anwar, M.S.; Lohana, D.; Kumar, P.; Nandula, S.A.; Nawaz, F.K.; Tracey, K.; Yang, H.; LeRoith, D.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1: A multi-faceted anti-inflammatory agent. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Tan, S.; Lin, Y.; Liao, S.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist reduces inflammation and blood-brain barrier breakdown in an astrocyte-dependent manner in experimental stroke. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Shao, S. Exenatide regulates Th17/Treg balance via PI3K/Akt/FoxO1 pathway in db/db mice. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, G.; Gomes Moreira, D.; Richner, M.; Mutsaers, H.A.M.; Ferreira, N.; Jan, A. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Neurodegeneration: Neurovascular Unit in the Spotlight. Cells 2022, 11, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M. From metabolism to mind: The expanding role of the GLP-1 receptor in neurotherapeutics. Neurotherapeutics 2025, 22, e00712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B. Transcriptomics and proteomics characterizing the antioxidant mechanisms of semaglutide in diabetic mice with cognitive impairment. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 55, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; He, Y.; Yang, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhang, M. Semaglutide ameliorates diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction in mouse model of type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Wu, T.; Dai, J.; Zhai, Z.; Cai, J.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Sun, T. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in experimental Alzheimer’s disease models: A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1205207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Hao, Y.; Liu, H.; Gao, F. The immunomodulatory effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists in neurogenerative diseases and ischemic stroke treatment. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1525623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Yang, S.; Guo, F.; Zheng, B.; Wang, J. Tirzepatide mitigates Stroke-Induced Blood-Brain barrier disruption by modulating Claudin-1 and C/EBP-alpha pathways. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josey, K.; Liu, W.; Warsavage, T.; Medici, M.; Kvist, K.; Derington, C.G.; Reusch, J.E.B.; Ghosh, D.; Raghavan, S. Real-world cardiovascular effects of liraglutide: Transportability analysis of the LEADER trial. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Husain, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Shen, Z.; Vilsboll, T.; Ge, J. Effect of semaglutide versus placebo on cardiorenal outcomes by prior cardiovascular disease and baseline body mass index: Pooled post hoc analysis of SUSTAIN 6 and PIONEER 6. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 5706–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alammari, N.; Alshehri, A.; Al Khalaf, A.; Alamri, R.A.; Alhalal, N.; Sultan, M.A.; Ogran, N.; Aljohani, R.M.S.; Alasmari, S.M.S.; Alsharif, S.B.; et al. Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on incidence and outcomes of ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 4387–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIsaac, R.J. Semaglutide: A key medication for managing cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome. Future Cardiol. 2025, 21, 663–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gejl, M.; Brock, B.; Egefjord, L.; Vang, K.; Rungby, J.; Gjedde, A. Blood-Brain Glucose Transfer in Alzheimer’s disease: Effect of GLP-1 Analog Treatment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.; Nassar, O.; Abosheaishaa, H.; Misra, A. Comparative outcomes of systemic diseases in people with type 2 diabetes, or obesity alone treated with and without GLP-1 receptor agonists: A retrospective cohort study from the Global Collaborative Network: Author list. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2025, 48, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukierman-Yaffe, T.; Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Diaz, R.; Garcia-Perez, L.E.; Lakshmanan, M.; Bethel, A.; Xavier, D.; Probstfield, J.; Riddle, M.C.; et al. Effect of dulaglutide on cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes: An exploratory analysis of the REWIND trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A.; Rosanbalm, S.; Leinonen, M.; Olanow, C.W.; To, D.; Bell, A.; Lee, D.; Chang, J.; Dubow, J.; Dhall, R.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of NLY01 in early untreated Parkinson’s disease: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holscher, C. Protective properties of GLP-1 and associated peptide hormones in neurodegenerative disorders. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiang, Q.; Li, N.; Feng, P.; Wei, W.; Holscher, C. Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-Based Therapies in Ischemic Stroke: An Update Based on Preclinical Research. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 844697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Lopez, T. Peripheral Inflammation and Insulin Resistance: Their Impact on Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity and Glia Activation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Luo, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Tang, J.; Qing, L. Metformin induces M2 polarization via AMPK/PGC-1alpha/PPAR-gamma pathway to improve peripheral nerve regeneration. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 3778–3792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geranmayeh, M.H.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Saeedi, N.; Farhoudi, M. Metformin-dependent variation of microglia phenotype dictates pericytes maturation under oxygen-glucose deprivation. Tissue Barriers 2022, 10, 2018928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Lin, X.; Lin, R.; Chen, Z.; Miao, C.; Wang, Y.; Deng, X.; Lin, J.; Lin, S.; Weng, S.; et al. Effectively alleviate rheumatoid arthritis via maintaining redox balance, inducing macrophage repolarization and restoring homeostasis of fibroblast-like synoviocytes by metformin-derived carbon dots. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiazza, F.; Tammen, H.; Pintana, H.; Lietzau, G.; Collino, M.; Nystrom, T.; Klein, T.; Darsalia, V.; Patrone, C. The effect of DPP-4 inhibition to improve functional outcome after stroke is mediated by the SDF-1alpha/CXCR4 pathway. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, W.; Behnammanesh, G.; Peyton, K.J. Effects of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors on Vascular Cell Function and Arterial Remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, M.; Tu, X.; Mo, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Wang, F.; Kim, Y.B.; Huang, C.; Chen, L.; et al. Dietary Polyphenols as Anti-Aging Agents: Targeting the Hallmarks of Aging. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, L.P.; Thao, G.; Chitre, T.; Rojas, E.D.; Nguyen Fricko, M.; Domingo, V.; Budginas, B.; Guerrero, L.C.; Ghatas, M.; Arani, N.T.; et al. A System-Based Review on Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists: Benefits vs Risks. Cureus 2025, 17, e78575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelle, M.C.; Zaffina, I.; Giofre, F.; Pujia, R.; Arturi, F. Potential Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in the Treatment of Cognitive Decline and Dementia in Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, L.C.R.; Luizon, M.R.; Gomes, K.B. Exploring the Role of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Receptors 2025, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.T.; Chen, J.H.; Hu, C.J. Role of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, A.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, J.E. Neuroprotective roles of SGLT2 and DPP4 inhibitors: Modulating ketone metabolism and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome in T2D induced Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 390, 115271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelopoulou, E.; Piperi, C. DPP-4 inhibitors: A promising therapeutic approach against Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Su, C.; Qiao, C.; Bian, Y.; Ding, J.; Hu, G. Metformin Prevents Dopaminergic Neuron Death in MPTP/P-Induced Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease via Autophagy and Mitochondrial ROS Clearance. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 19, pyw047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, M.; Grand, M.K.; Arvedsen, J.; Meaidi, A.; Morch, L.S. GLP-1 Agonists as Potential Neuromodulators in Development of Parkinson’s Disease: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2025, 32, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lv, S.; Miao, M.; Chen, W.M.; Wu, S.Y.; Zhang, J. Evaluating GLP-1 receptor agonists versus metformin as first-line therapy for reducing dementia risk in type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2025, 13, e004902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Cheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Wei, S.; Zhou, X.; Qin, Z.; Jia, J.; Zhen, X. Improvement of functional recovery by chronic metformin treatment is associated with enhanced alternative activation of microglia/macrophages and increased angiogenesis and neurogenesis following experimental stroke. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014, 40, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hamed, F.A.; Elewa, H. Potential Therapeutic Effects of Sodium Glucose-linked Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in Stroke. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, e242–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, M.; Pal, R.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Nair, K. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Risk of Adverse Cerebrovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 1806–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Nie, C.; Pan, S.; Wang, B.; Hong, X.; Xi, S.; Bai, J.; Yu, M.; Liu, J.; Yang, W. Co-administration of hydrogen and metformin exerts cardioprotective effects by inhibiting pyroptosis and fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 183, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescariu, S.A.; Elagez, A.; Nallapati, B.; Bratosin, F.; Bucur, A.; Negru, A.; Gaita, L.; Citu, I.M.; Popa, Z.L.; Barata, P.I. Examining the Impact of Ertugliflozin on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saud, S.A. Effectiveness of Empagliflozin in Treating Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Systematic Review. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2025, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheen, A.J. Cardiovascular outcome studies in type 2 diabetes: Comparison between SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 143, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Xu, X.; Guo, Y. Dapagliflozin improves cardiac function and reduces adverse events in myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis in diabetic and non-diabetic populations. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1594861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNair, B.D.; Polson, S.M.; Shorthill, S.K.; Yusifov, A.; Walker, L.A.; Weiser-Evans, M.C.M.; Kovacs, E.J.; Bruns, D.R. Metformin protects against pulmonary hypertension-induced right ventricular dysfunction in an age- and sex-specific manner independent of cardiac AMPK. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2023, 325, H278–H292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deedwania, P.; Acharya, T. Cardiovascular Protection with Anti-hyperglycemic Agents. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2019, 19, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lewinski, D.; Kolesnik, E.; Wallner, M.; Resl, M.; Sourij, H. New Antihyperglycemic Drugs and Heart Failure: Synopsis of Basic and Clinical Data. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1253425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Holscher, C. Neuroprotective effects of a triple GLP-1/GIP/glucagon receptor agonist in the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2018, 1678, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, A.; Roux, C.W.L.; Viljoen, A. The Road towards Triple Agonists: Glucagon-Like Peptide 1, Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide and Glucagon Receptor—An Update. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 39, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Li, M.; Wong, S.; Le, G.H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Valentino, K.; Dri, C.E.; McIntyre, R.S. Are Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists Central Nervous System (CNS) Penetrant: A Narrative Review. Neurol. Ther. 2025, 14, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiz, A.; Filion, K.B.; Tsoukas, M.A.; Yu, O.H.Y.; Peters, T.M.; Eisenberg, M.J. The expanding role of GLP-1 receptor agonists: A narrative review of current evidence and future directions. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 86, 103363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Xiao, J.; Long, Y.; Cao, T.; Lin, C.; Hei, G.; Wang, W.; Kang, D.; Huang, J.; Shao, T.; et al. Metformin-improved cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia is correlated with activation of tricarboxylic acid cycle and restored functional connectivity of hippocampus. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lv, S.; Miao, M.; Chen, W.M.; Wu, S.Y.; Zhang, J. Comparative study of SGLT2 inhibitors and metformin: Evaluating first-line therapies for dementia prevention in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2025, 51, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabhai, T.; Zingel, R.; Bohlken, J.; Kostev, K. Association between SGLT2 inhibitor therapy and prolonged dementia-free survival in older adults with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective cohort study from Germany. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 229, 112430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trial/Study | Focus | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| EXAMINE | CVOT (Alogliptin) | MACE-neutral |

| SAVOR-TIMI 53 | CVOT (Saxagliptin) | MACE-neutral; ↑ HF risk |

| TECOS | CVOT (Sitagliptin) | CV-safe |

| CAROLINA | Linagliptin vs. Glimepiride | Non-inferior on MACE |

| CARMELINA | CV/Kidney (Linagliptin) | No ↑ risk; renal safety |

| Kim et al. (2019) [89] | Dementia incidence | ↓ Risk in DPP-4i users |

| Maanvi et al. (2022) [90] | Parkinson & cognition | Reviews ↓ incidence data |

| Calabrese et al. (2021) [91] | Aging, T2DM, neuro | Metformin + DPP-4i ↓ Parkinson risk |

| Epelde (2024) [92] | CV & neuro review | Need for neuro RCTs |

| Drug Class | Study | Sample Size | Cognitive/Dementia Outcome | Effect Size (HR, OR, Score) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1RA (liraglutide) | Mild Alzheimer’s RCT (6months) | N = 38 | Stabilized brain glucose metabolism (FDG-PET) vs. placebo; no difference in cognitive test scores | Δ FDG-PET decline: −0.024 vs. −0.039 SUVR | p ≈ 0.01 for PET; NS for cognition |

| GLP-1RA (dulaglutide) | REWIND post hoc cognitive analysis | N = 8828 | Slower cognitive decline on composite cognitive score compared to placebo | Mean difference: −0.058 | p = 0.026 |

| GLP-1RA | Observational dementia cohorts (older adults with T2D) | N = 50,000–200,000 | Lower incidence of dementia compared with non-GLP-1 users | HR 0.75–0.82 | p < 0.05 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors (class) | Observational dementia cohort (T2D + metformin) | N ≈ 30,000 | Lower risk of dementia vs. other regimens; slower cognitive decline | HR 0.75–0.85 | p < 0.05 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors (class) | Parkinson’s risk cohort | N ≈ 20,000 | Reduced incidence of Parkinson’s disease | ~15–20% risk reduction | p < 0.05 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors (EXAMINE, SAVOR, TECOS) | CVOTs with cognitive outcomes not measured | N = 5000–16,500 | No cognitive endpoints measured | - | - |

| Drug Clas | Key Neuroprotective Mechanism | Observed/Proposed Benefits | Major Limitations & Challenges | Translational Opportunities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin | Activates AMPK, suppresses mTOR, enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, reduces oxidative stress and inflammation | ↓ Aβ and tau phosphorylation; ↑ autophagy; improved neuronal metabolism and cognitive performance (in preclinical studies) | Limited BBB penetration; inconsistent clinical outcomes; risk of lactic acidosis in renal impairment; unclear long-term safety in non-diabetics | Develop brain-penetrant analogs; combine with lifestyle/metabolic interventions; biomarker-guided prevention trials |

| GLP-1R Agonists | Activates GLP-1R → cAMP/PKA pathway; anti-inflammatory; anti-apoptotic; enhances synaptic plasticity | ↓ Microglial activation, ↓ Aβ, ↓ tau pathology, ↑ cognition; dual benefit for cardiovascular health | Injectable route; GI side effects; high cost; uncertain CNS exposure in humans | Optimize CNS delivery (intranasal/analog design); evaluate long-term neurovascular effects in ongoing AD trials (EVOKE/EVOKE+) |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | ↓ Glucose toxicity, ↓ oxidative stress, improves mitochondrial function and BBB integrity | Improved cognitive outcomes in diabetic patients; ↑ cerebral perfusion; ↓ inflammation | Limited mechanistic CNS data; dehydration and ketoacidosis risk; low BBB penetration | Conduct dedicated cognitive trials; study neurovascular coupling and ketone metabolism; explore brain-targeted analogs |

| DPP-4 Inhibitors | ↑ Endogenous GLP-1, ↓ cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6), ↑ Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response | ↓ Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress; potential neurovascular protection | Modest CNS penetration; indirect mechanism may limit efficacy; minimal cognitive clinical data | Combine with GLP-1R agonists for additive benefit; biomarker validation for inflammation/oxidative stress modulation |

| TZDs (PPARy agonists) | Activates PPARγ → inhibits NF-κB, reduces oxidative stress and glial activation | ↓ Neuroinflammation; improved mitochondrial function and vascular health | Mixed clinical trial outcomes; weight gain, edema, cardiac risk | Develop selective PPARγ modulators; stratify trials by insulin resistance and inflammatory biomarkers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raut, S.; Cucullo, L. Antidiabetic Agents as Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Therapies in Neurological and Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121490

Raut S, Cucullo L. Antidiabetic Agents as Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Therapies in Neurological and Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121490

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaut, Snehal, and Luca Cucullo. 2025. "Antidiabetic Agents as Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Therapies in Neurological and Cardiovascular Diseases" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121490

APA StyleRaut, S., & Cucullo, L. (2025). Antidiabetic Agents as Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Therapies in Neurological and Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121490