Methyl Gallate Enhances Post-Thaw Boar Sperm Quality by Alleviating Oxidative Stress and Preserving Mitochondrial Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Reagents and Freezing Extenders

2.2. Semen Collection and Processing

2.3. Sperm Cryopreservation and Thawing

2.4. Assessment of Sperm Motility (CASA System)

2.5. Thermo-Resistance Test (TRT)

2.6. Assessment of Sperm Plasma Membrane and Acrosome Integrity

2.7. Assessment of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP)

2.8. Determination of Sperm ATP Content

2.9. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Levels

2.10. Determination of Total Antioxidant Capacity (T-AOC) and Malondialdehyde (MDA) Levels

2.11. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

2.12. Assessment of Sperm Apoptosis

2.13. Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.14. Western Blot Analysis

2.15. In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. MG Improved Post-Thaw Sperm Motility Parameters

3.2. MG Enhanced Post-Thaw Sperm Heat Tolerance

3.3. MG Increased Post-Thaw Acrosome and Plasma Membrane Integrity

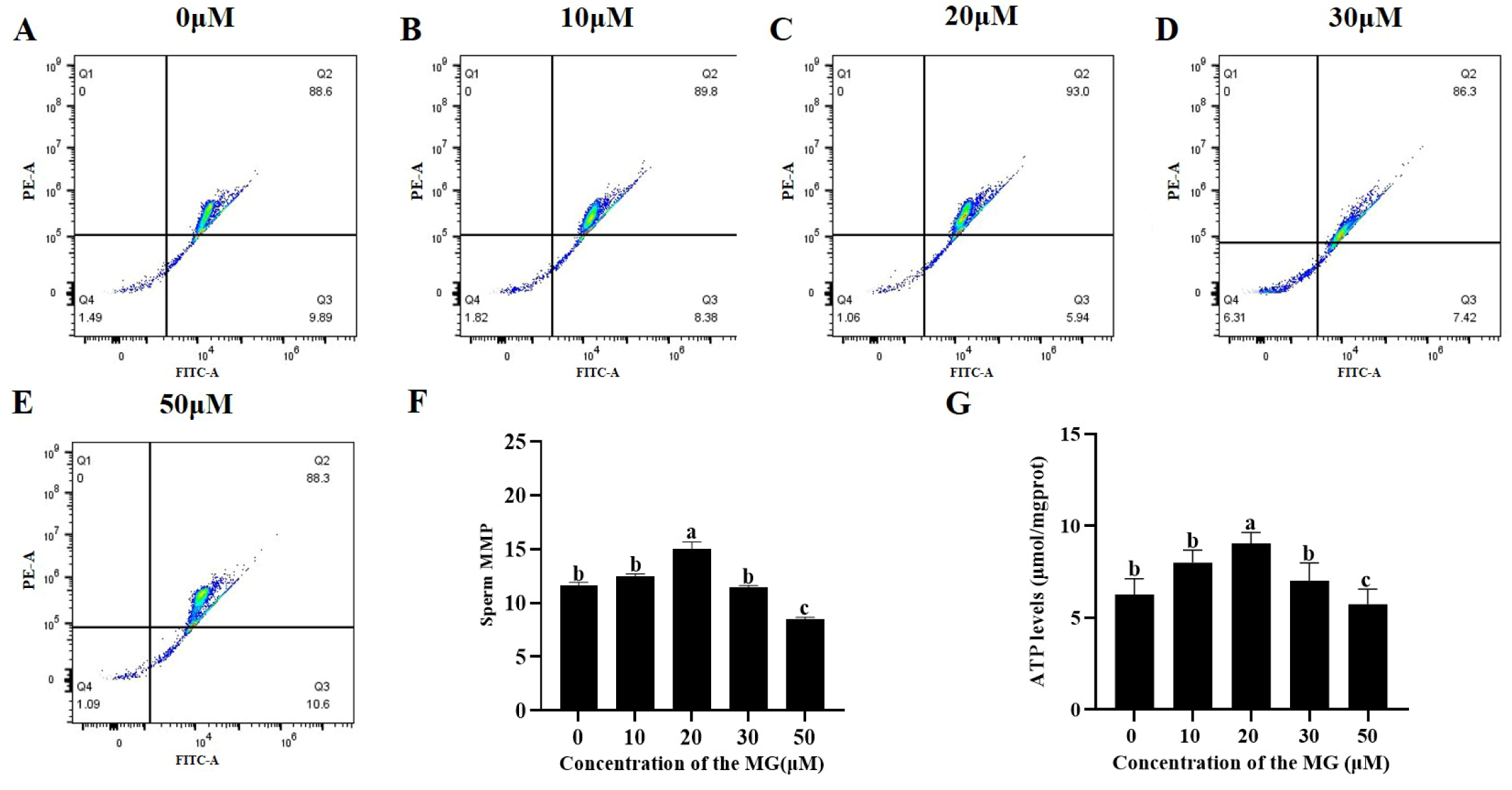

3.4. MG Elevated Post-Thaw Sperm MMP and ATP Levels

3.5. MG Reduced Post-Thaw Sperm Oxidative Stress Levels

3.6. MG Enhanced Post-Thaw Sperm Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

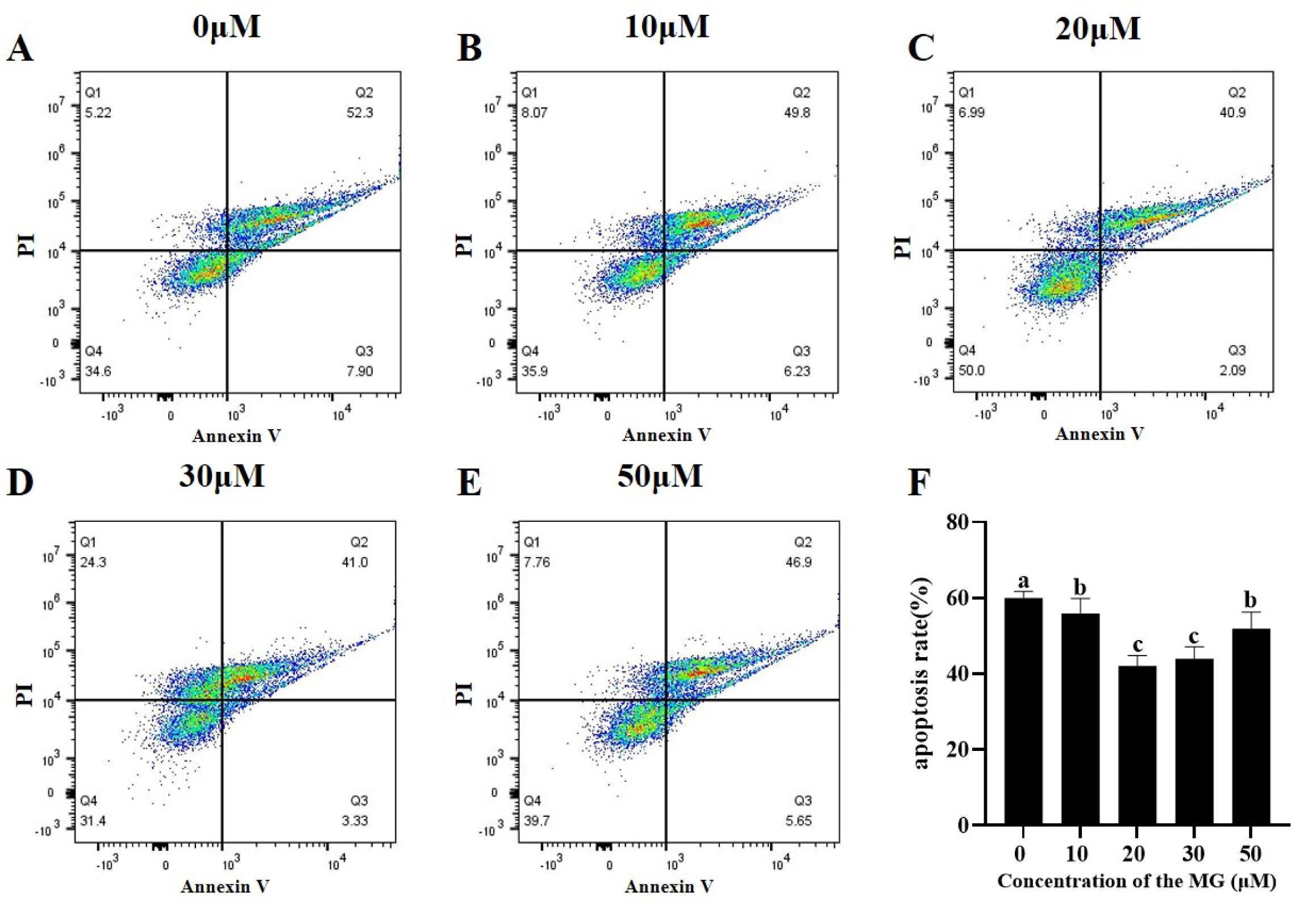

3.7. MG Decreased Post-Thaw Sperm Apoptosis Levels

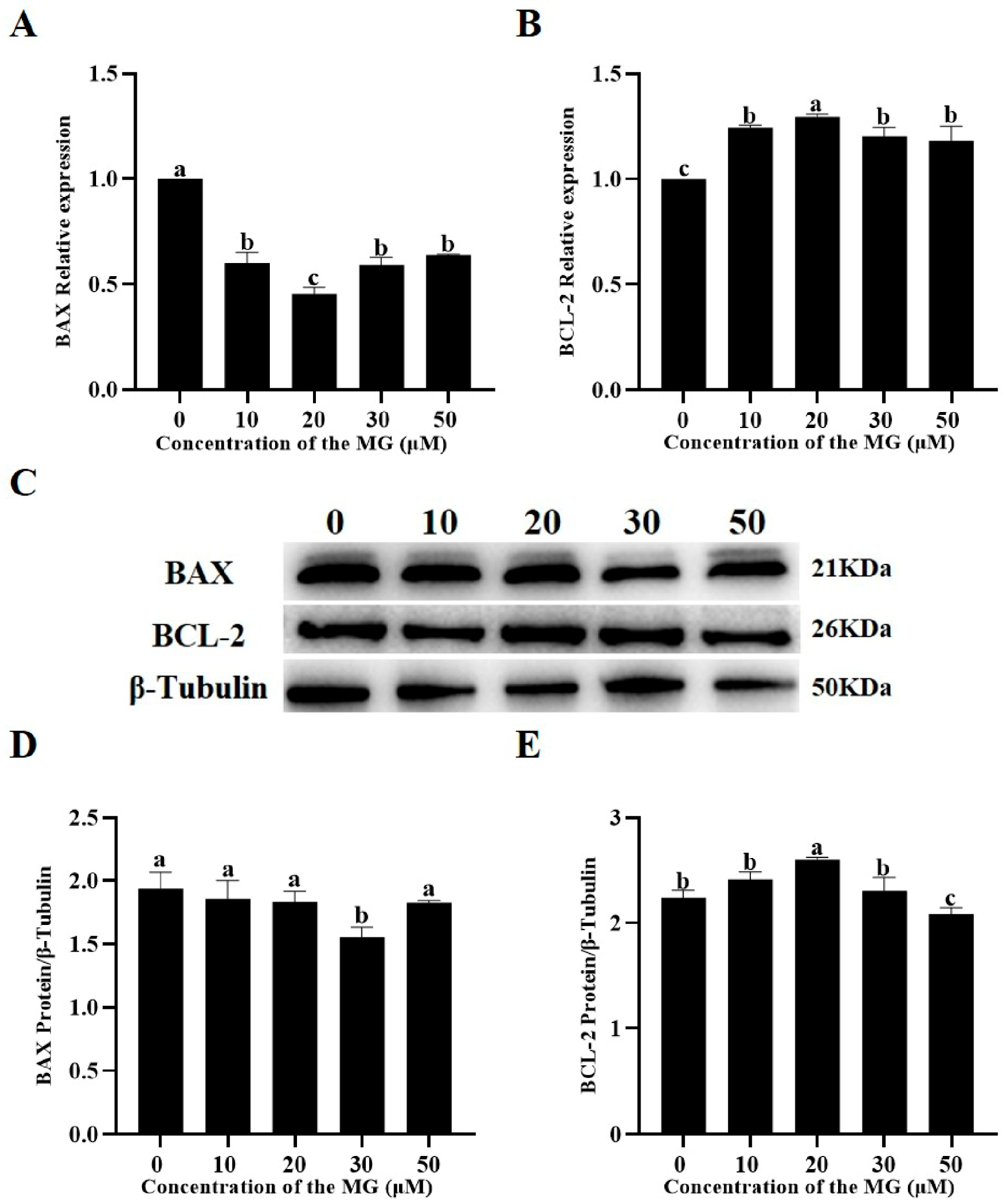

3.8. MG Modulated Apoptosis-Related Gene and Protein Expression in Post-Thaw Sperm

3.9. MG Improved Post-Thaw Sperm Fertilization Capacity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, S.; Yang, L.; Gao, L.; Ning, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W. The effect of combined cryoprotectants on the cryotolerance of boar sperm. Anim. Biosci. 2025, 38, 2111–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolarin, A.; Berndtson, J.; Tejerina, F.; Cobos, S.; Pomarino, C.; D’Alessio, F.; Blackburn, H.; Kaeoket, K. Boar semen cryopreservation: State of the art, and international trade vision. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 269, 107496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezo, F.; Romero, F.; Zambrano, F.; Sanchez, R.S. Preservation of boar semen: An update. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2019, 54, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waberski, D.; Riesenbeck, A.; Schulze, M.; Weitze, K.F.; Johnson, L. Application of preserved boar semen for artificial insemination: Past, present and future challenges. Theriogenology 2019, 137, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanez-Ortiz, I.; Catalan, J.; Rodriguez-Gil, J.E.; Miro, J.; Yeste, M. Advances in sperm cryopreservation in farm animals: Cattle, horse, pig and sheep. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 246, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Qiu, S.; Chen, X.; Cai, B.; Xie, H. Freeze-thawing impairs the motility, plasma membrane integrity and mitochondria function of boar spermatozoa through generating excessive ROS. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, C.; Scarlata, E. OXIDATIVE STRESS AND REPRODUCTIVE FUNCTION: The protection of mammalian spermatozoa against oxidative stress. Reproduction 2022, 164, F67–F78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Min, L.; Li, Y.; Lang, Y.; Hoque, S.A.M.; Adetunji, A.O.; Zhu, Z. Beneficial Effect of Proline Supplementation on Goat Spermatozoa Quality during Cryopreservation. Animals 2022, 12, 2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, A.; Bakos, H.W.; Aitken, R.J. Sperm cryopreservation: Current status and future developments. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2023, 35, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianese, R.; Pierantoni, R. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production Alters Sperm Quality. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, C.; Sohail, T.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Damage to Mitochondria During the Cryopreservation, Causing ROS Leakage, Leading to Oxidative Stress and Decreased Quality of Ram Sperm. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2024, 59, e14737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrabi, S.W.; Ara, A.; Saharan, A.; Jaffar, M.; Gugnani, N.; Esteves, S.C. Sperm DNA Fragmentation: Causes, evaluation and management in male infertility. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2024, 28, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Shi, W.; Fang, Y.; Xu, C.; Deng, Z.; Feng, W.; Shi, D. The Effects of Limonin, Myo-Inositol, and L-Proline on the Cryopreservation of Debao Boar Semen. Animals 2025, 15, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujoana, T.C.; Sehlabela, L.D.; Mabelebele, M.; Sebola, N.A. The potential significance of antioxidants in livestock reproduction: Sperm viability and cryopreservation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 267, 107512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Rubio, F.; Soria-Meneses, P.J.; Jurado-Campos, A.; Bartolome-Garcia, J.; Gomez-Rubio, V.; Soler, A.J.; Arroyo-Jimenez, M.M.; Santander-Ortega, M.J.; Plaza-Oliver, M.; Lozano, M.V.; et al. Nanotechnology in reproduction: Vitamin E nanoemulsions for reducing oxidative stress in sperm cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, A.J.; Bakos, H.W.; Aitken, R.J. Addition of Vitamin C Mitigates the Loss of Antioxidant Capacity, Vitality and DNA Integrity in Cryopreserved Human Semen Samples. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeoket, K.; Chanapiwat, P. The Beneficial Effect of Resveratrol on the Quality of Frozen-Thawed Boar Sperm. Animals 2023, 13, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.; Tanga, B.M.; Fang, X.; Seong, G.; Saadeldin, I.M.; Qamar, A.Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.; Park, Y.; Nabeel, A.H.T.; et al. Cryopreservation of Pig Semen Using a Quercetin-Supplemented Freezing Extender. Life 2022, 12, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Min, L.; Cao, H.; Adetunji, A.O.; Zhou, K.; Zhu, Z. Pyrroloquinoline Quinone Improved Boar Sperm Quality via Maintaining Mitochondrial Function During Cryopreservation. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, E.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Sperm freezing damage: The role of regulated cell death. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozimic, S.; Ban-Frangez, H.; Stimpfel, M. Sperm Cryopreservation Today: Approaches, Efficiency, and Pitfalls. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 4716–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berean, D.I.; Bogdan, L.M.; Cimpean, R. Advancements in Understanding and Enhancing Antioxidant-Mediated Sperm Cryopreservation in Small Ruminants: Challenges and Perspectives. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Huang, Q.; Zou, L.; Wei, P.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y. Methyl gallate: Review of pharmacological activity. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 194, 106849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, S.; Siew, Y.; Yew, H.; He, Y.; Poh, K.; Tsai, Y.; Ng, S.; Tan, W.; Chong, T.; Lim, C.S.E.; et al. Effects of Leea indica leaf extracts and its phytoconstituents on natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity in human ovarian cancer. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Weng, P. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effect of (-)-epigallocatechin 3-O-(3-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG3′′Me) from Chinese oolong tea. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2014, 62, 10046–10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, B.; Lv, C.; Zhu, X.; Naren, Q.; Xu, D.; Chen, H.; Wu, F. Methyl gallate prevents oxidative stress induced apoptosis and ECM degradation in chondrocytes via restoring Sirt3 mediated autophagy and ameliorates osteoarthritis progression. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 114, 109489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas, E.C.; Correa, L.B.; Padua, T.D.A.; Costa, T.E.M.M.; Mazzei, J.L.; Heringer, A.P.; Bizarro, C.A.; Kaplan, M.A.C.; Figueiredo, M.R.; Henriques, M.G. Anti-inflammatory effect of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi hydroalcoholic extract on neutrophil migration in zymosan-induced arthritis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 175, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, N.S.; Cascaes, M.M.; Da Silva Santos, L.; de Oliveira, M.S.; Das Gracas Bichara Zoghbi, M.; Araujo, I.S.; Uetanabaro, A.P.T.; de Aguiar Andrade, E.H.; Guilhon, G.M.S.P. Flavanone Glycosides, Triterpenes, Volatile Compounds and Antimicrobial Activity of Miconia minutiflora (Bonpl.) DC. (Melastomataceae). Molecules 2022, 27, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Safwan, S.; Cheng, M.; Liao, T.; Cheng, L.; Chen, T.; Kuo, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lee, C. Protective Evaluation of Compounds Extracted from Root of Rhodiola rosea L. against Methylglyoxal-Induced Toxicity in a Neuronal Cell Line. Molecules 2020, 25, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, W.K.; Park, H.S.; Ham, I.H.; Oh, M.; Namkoong, H.; Kim, H.K.; Hwang, D.W.; Hur, S.Y.; Kim, T.E.; Park, Y.G.; et al. Methyl gallate and chemicals structurally related to methyl gallate protect human umbilical vein endothelial cells from oxidative stress. Exp. Mol. Med. 2005, 37, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.J.; Jung, H.J.; Park, C.H.; Yokozawa, T.; Jeong, J. Root Bark of Paeonia suffruticosa Extract and Its Component Methyl Gallate Possess Peroxynitrite Scavenging Activity and Anti-inflammatory Properties through NF-kappaB Inhibition in LPS-treated Mice. Molecules 2019, 24, 3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, B.; Kim, K. Antioxidant activity and protective effect of methyl gallate against t-BHP induced oxidative stress through inhibiting ROS production. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 31, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas-Maynou, J.; Mateo-Otero, Y.; Delgado-Bermudez, A.; Bucci, D.; Tamanini, C.; Yeste, M.; Barranco, I. Role of exogenous antioxidants on the performance and function of pig sperm after preservation in liquid and frozen states: A systematic review. Theriogenology 2021, 173, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, H.; Wang, X.; Hu, K.; Zuo, X.; Li, H.; Diao, Z.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Z. Effects of Mogroside V on Quality and Antioxidant Activity of Boar Frozen-Thawed Sperm. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almubarak, A.; Lee, S.; Yu, I.; Jeon, Y. Effects of Nobiletin supplementation on the freezing diluent on porcine sperm cryo-survival and subsequent in vitro embryo development. Theriogenology 2024, 214, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mili, B.; Chutia, T.; Buragohain, L.; Palanisammi, A.; Kumaresan, A. Liquid storage of boar semen: Current approaches to reducing sperm damage using antioxidants and nanotechnology. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 278, 107871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galarza, D.A.; Jaramillo, J.; Amon, N.; Campoverde, B.; Aguirre, B.; Taboada, J.; Samaniego, X.; Duma, M. Effect of resveratrol supplementation in conventional slow and ultra-rapid freezing media on the quality and fertility of bull sperm. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 266, 107495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Bian, X.; Ding, C.; Wu, T.; Li, D.; Zhou, J. Ameliorative effect of silymarin on the quality of frozen-thawed boar spermatozoa. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2023, 58, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Jahan, S.; Riaz, M.; Khan, B.T.; Ijaz, M.U. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) addition as an antioxidant in a cryo-diluent media improves microscopic parameters, and fertility potential, and alleviates oxidative stress parameters of buffalo spermatozoa. Cryobiology 2020, 97, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, S.; Dada, R. Oxidative stress: Major executioner in disease pathology, role in sperm DNA damage and preventive strategies. Front. Biosci. (Schol. Ed.) 2017, 9, 420–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, X.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Chao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Nie, H.; Zhu, W.; Tan, Y.; et al. Improving native human sperm freezing protection by using a modified vitrification method. Asian J. Androl. 2021, 23, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vazquez, F.A.; Gadea, J.; Matas, C.; Holt, W.V. Importance of sperm morphology during sperm transport and fertilization in mammals. Asian J. Androl. 2016, 18, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Q.; Huang, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Chen, G.; Li, K.; Ai, J. Influence of Different Quality Sperm on Early Embryo Morphokinetic Parameters and Cleavage Patterns: A Retrospective Time-lapse Study. Curr. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Kalo, D.; Zeron, Y.; Roth, Z. Progressive motility—A potential predictive parameter for semen fertilization capacity in bovines. Zygote 2016, 24, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaloga, G.P. Narrative Review of n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation upon Immune Functions, Resolution Molecules and Lipid Peroxidation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Sheng, N.; Zhao, A.Z.; Dai, J. Perfluorooctanoic acid exposure alters polyunsaturated fatty acid composition, induces oxidative stress and activates the AKT/AMPK pathway in mouse epididymis. Chemosphere 2016, 158, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Jin, X.; Shi, X.; Lin, J.; Yue, S.; Zhou, J. Effects of astaxanthin on plasma membrane function and fertility of boar sperm during cryopreservation. Theriogenology 2021, 164, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohideen, K.; Chandrasekar, K.; Ramsridhar, S.; Rajkumar, C.; Ghosh, S.; Dhungel, S. Assessment of Oxidative Stress by the Estimation of Lipid Peroxidation Marker Malondialdehyde (MDA) in Patients with Chronic Periodontitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Dent. 2023, 2023, 6014706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Feng, T.; Wu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Wu, M.; Pang, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, A.; Zhang, D.; et al. The role of total antioxidant capacity and malondialdehyde of seminal plasma in the association between air pollution and sperm quality. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 335, 122324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyethodi, R.R.; Sirohi, A.S.; Karthik, S.; Tyagi, S.; Perumal, P.; Singh, U.; Sharma, A.; Kundu, A. Role of seminal MDA, ROS, and antioxidants in cryopreservation and their kinetics under the influence of ejaculatory abstinence in bovine semen. Cryobiology 2021, 98, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, E.; Nikzad, H.; Karimian, M. Oxidative stress and male infertility: Current knowledge of pathophysiology and role of antioxidant therapy in disease management. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Qu, J.; Zhan, Y.; Wu, X.; Qiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Li, B. Evaluation of intracellularly targeted engineered antioxidant fusion proteins SOD-LCA2 and Prx-LCA2 as promising therapeutic combinations for alleviating and restoring pulmonary oxidative damage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.; Liu, T.; Chia, Y.; Chern, C.; Lu, F.; Chuang, M.; Mau, S.; Chen, S.; Syu, Y.; Chen, C. Protective effect of methyl gallate from Toona sinensis (Meliaceae) against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage in MDCK cells. Food. Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, F. Chemical Basis of Reactive Oxygen Species Reactivity and Involvement in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Sharma, R.; Assidi, M.; Abuzenadah, A.M.; Alshahrani, S.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Sabanegh, E. Characterizing semen parameters and their association with reactive oxygen species in infertile men. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2014, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Schatten, H.; Sun, Q. Sperm mitochondria in reproduction: Good or bad and where do they go? J. Genet. Genom. 2013, 40, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppers, A.J.; De Iuliis, G.N.; Finnie, J.M.; Mclaughlin, E.A.; Aitken, R.J. Significance of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in the generation of oxidative stress in spermatozoa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 3199–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Baker, M.A. Oxidative stress, sperm survival and fertility control. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2006, 250, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, T.M.; Gaglani, A.; Agarwal, A. Implication of apoptosis in sperm cryoinjury. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2010, 21, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Berghe, T.V.; Vandenabeele, P.; Kroemer, G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renault, T.T.; Dejean, L.M.; Manon, S. A brewing understanding of the regulation of Bax function by Bcl-xL and Bcl-2. Mech. Ageing. Dev. 2017, 161, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Oh, H.J.; Liu, H.; Kim, M.K. Schisandrin B protects boar spermatozoa against oxidative damage and increases their fertilization ability during in vitro storage. Theriogenology 2023, 198, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, F.; Khoshsokhan Muzaffar, M.; Jannatifar, R. The association of sperm BAX and BCL-2 gene expression with reproductive outcome in Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia cases undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A case-control study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2024, 22, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapanidou, V.; Tsantarliotou, M.P.; Feidantsis, K.; Tzekaki, E.E.; Kourousekos, G.; Lavrentiadou, S.N. Supplementing Freezing Medium with Crocin Exerts a Protective Effect on Bovine Spermatozoa Through the Modulation of a Heat Shock-Mediated Apoptotic Pathway. Molecules 2025, 30, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Chang, Y.; Wei, P.; Hung, C.; Wang, W. Methyl gallate, gallic acid-derived compound, inhibit cell proliferation through increasing ROS production and apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, S.; Xu, B.; Yan, X.; Zhang, J.; Su, R. Sperm Membrane Stability: In-Depth Analysis from Structural Basis to Functional Regulation. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalthur, G.; Raj, S.; Thiyagarajan, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, P.; Adiga, S.K. Vitamin E supplementation in semen-freezing medium improves the motility and protects sperm from freeze-thaw-induced DNA damage. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1149–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Accession Number | Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | ||

| BCL-2 | XM_003121700.3 | GGCAACCCATCCTGGCACCT | AACTCATCGCCCGCCTCCCT |

| BAX | XM_003355975.2 | GCCGAAATGTTTGCTGACGG | CGAAGGAAGTCCAGCGTCCA |

| GAPDH | NM_001206359.1 | CACGATGGTGAAGGTCGGAG | TTGACTGTGCCGTGGAACTT |

| Parameters | 0 μM | 10 μM | 20 μM | 30 μM | 50 μM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM (%) | 75.03 ± 1.86 c | 81.57 ± 0.83 a | 82.59 ± 1.00 a | 78.11 ± 0.87 b | 73.01 ± 0.35 d |

| PM (%) | 53.93 ± 0.33 d | 57.26 ± 0.52 b | 63.30 ± 0.44 a | 55.19 ± 0.54 c | 52.57 ± 0.58 d |

| VSL (μm/s) | 23.22 ± 0.34 b | 23.58 ± 0.57 b | 25.75 ± 0.98 a | 25.85 ± 0.70 a | 21.46 ± 0.27 c |

| VCL (μm/s) | 49.81 ± 0.22 b | 52.16 ± 0.65 b | 55.74 ± 0.89 a | 52.70 ± 1.34 ab | 47.55 ± 0.36 c |

| VAP (μm/s) | 36.98 ± 1.12 ab | 36.12 ± 1.02 ab | 37.75 ± 1.06 a | 37.66 ± 1.05 a | 33.98 ± 0.26 c |

| ALH (μm) | 15.66 ± 1.69 b | 15.38 ± 0.84 b | 15.98 ± 1.49 a | 15.96 ± 0.63 a | 14.90 ± 0.43 b |

| WOB (%) | 84.67 ± 4.90 a | 89.58 ± 1.08 a | 86.25 ± 4.05 a | 90.50 ± 1.08 a | 85.67 ± 2.12 b |

| BCF (Hz) | 0.76 ± 0.01 ab | 0.76 ± 0.01 ab | 0.78 ± 0.01 a | 0.77 ± 0.01 ab | 0.74 ± 0.00 c |

| LIN (%) | 43.92 ± 0.68 b | 44.58 ± 0.69 a | 45.92 ± 0.56 a | 45.83 ± 0.76 a | 42.58 ± 0.43 b |

| MAD (°) | 160.45 ± 23.30 bc | 202.37 ± 19.35 ab | 251.10 ± 24.24 a | 195.45 ± 11.37 ab | 145.89 ± 10.79 c |

| STR (%) | 59.58 ± 1.42 b | 63.83 ± 1.81 a | 64.17 ± 0.63 a | 63.58 ± 1.73 a | 56.50 ± 0.50 c |

| Group | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total motility | ||||

| 0 μM | 60.57 ± 0.64 c | 56.52 ± 0.43 c | 51.48 ± 0.77 c | 47.46 ± 0.62 c |

| 10 μM | 66.70 ± 0.61 b | 65.47 ± 0.97 b | 61.17 ± 0.92 b | 56.01 ± 1.34 b |

| 20 μM | 69.82 ± 0.23 a | 67.80 ± 1.39 a | 63.98 ± 0.28 a | 60.81 ± 0.42 a |

| 30 μM | 67.80 ± 0.31 b | 58.88 ± 0.40 c | 56.61 ± 0.05 c | 51.75 ± 0.45 c |

| 50 μM | 63.04 ± 0.19 c | 58.34 ± 0.07 c | 54.64 ± 0.51 c | 50.85 ± 0.30 c |

| Progressive motility | ||||

| 0 μM | 45.23 ± 0.50 c | 42.01 ± 0.41 c | 38.58 ± 0.60 c | 35.95 ± 0.47 c |

| 10 μM | 51.20 ± 0.55 b | 49.10 ± 0.82 b | 45.80 ± 0.75 b | 41.25 ± 0.96 b |

| 20 μM | 54.80 ± 0.20 a | 52.65 ± 1.12 a | 48.25 ± 0.23 a | 44.05 ± 0.31 a |

| 30 μM | 52.37 ± 0.28 b | 44.51 ± 0.35 c | 42.25 ± 0.03 c | 38.52 ± 0.39 c |

| 50 μM | 48.10 ± 0.15 c | 44.05 ± 0.06 c | 40.20 ± 0.38 c | 36.15 ± 0.25 c |

| Groups | No. of Oocytes | No. of Cleaved | Cleavage Rate % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 μM | 220 | 113 | 51.36 ± 1.31 b |

| 20 μM | 269 | 162 | 60.22 ± 1.27 a |

| 50 μM | 285 | 130 | 45.61 ± 1.36 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bu, Y.; Shi, D.; Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, H. Methyl Gallate Enhances Post-Thaw Boar Sperm Quality by Alleviating Oxidative Stress and Preserving Mitochondrial Function. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121465

Bu Y, Shi D, Li J, Jiang X, Chen Y, Wu Z, Li W, Li L, Zhang S, Wei H. Methyl Gallate Enhances Post-Thaw Boar Sperm Quality by Alleviating Oxidative Stress and Preserving Mitochondrial Function. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121465

Chicago/Turabian StyleBu, Yonghui, Deming Shi, Jiahao Li, Xiaoxiang Jiang, Yuhan Chen, Zhenjun Wu, Wanxin Li, Li Li, Shouquan Zhang, and Hengxi Wei. 2025. "Methyl Gallate Enhances Post-Thaw Boar Sperm Quality by Alleviating Oxidative Stress and Preserving Mitochondrial Function" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121465

APA StyleBu, Y., Shi, D., Li, J., Jiang, X., Chen, Y., Wu, Z., Li, W., Li, L., Zhang, S., & Wei, H. (2025). Methyl Gallate Enhances Post-Thaw Boar Sperm Quality by Alleviating Oxidative Stress and Preserving Mitochondrial Function. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121465