Conventional and Advanced Processing Techniques and Their Effect on the Nutritional Quality and Antinutritional Factors of Pearl Millet Grains: The Impact on Metabolic Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pearl Millet Processing Techniques and the Impact on Metabolic Health

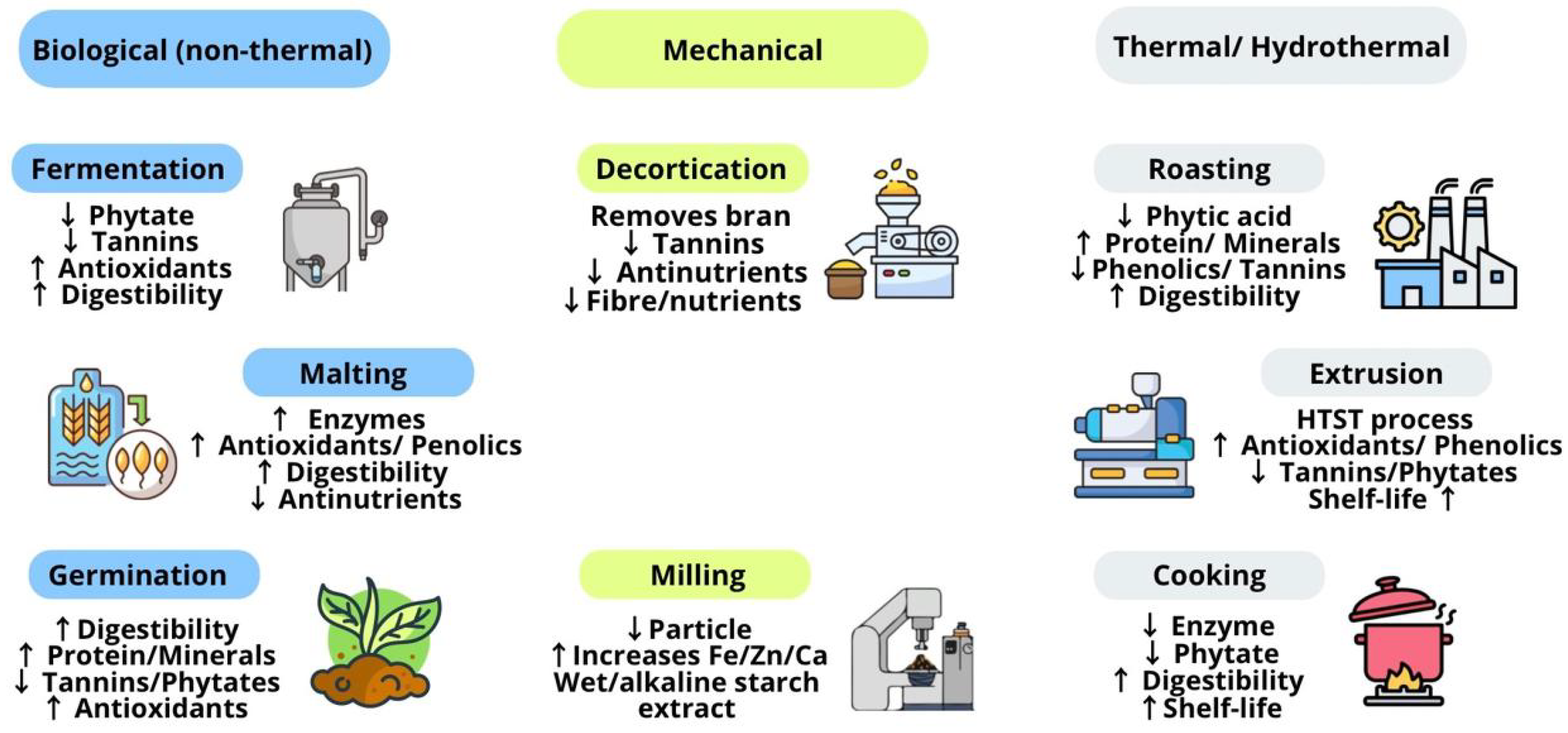

3.2. Conventional Techniques

3.2.1. Non-Thermal

Biological

- (a)

- Fermentation

- (b)

- Malting

- (c)

- Germination

Mechanical

- (a)

- Decortication

- (b)

- Milling

3.2.2. Thermal and Hydrothermal

- (a)

- Cooking

- (b)

- Roasting

- (c)

- Extrusion

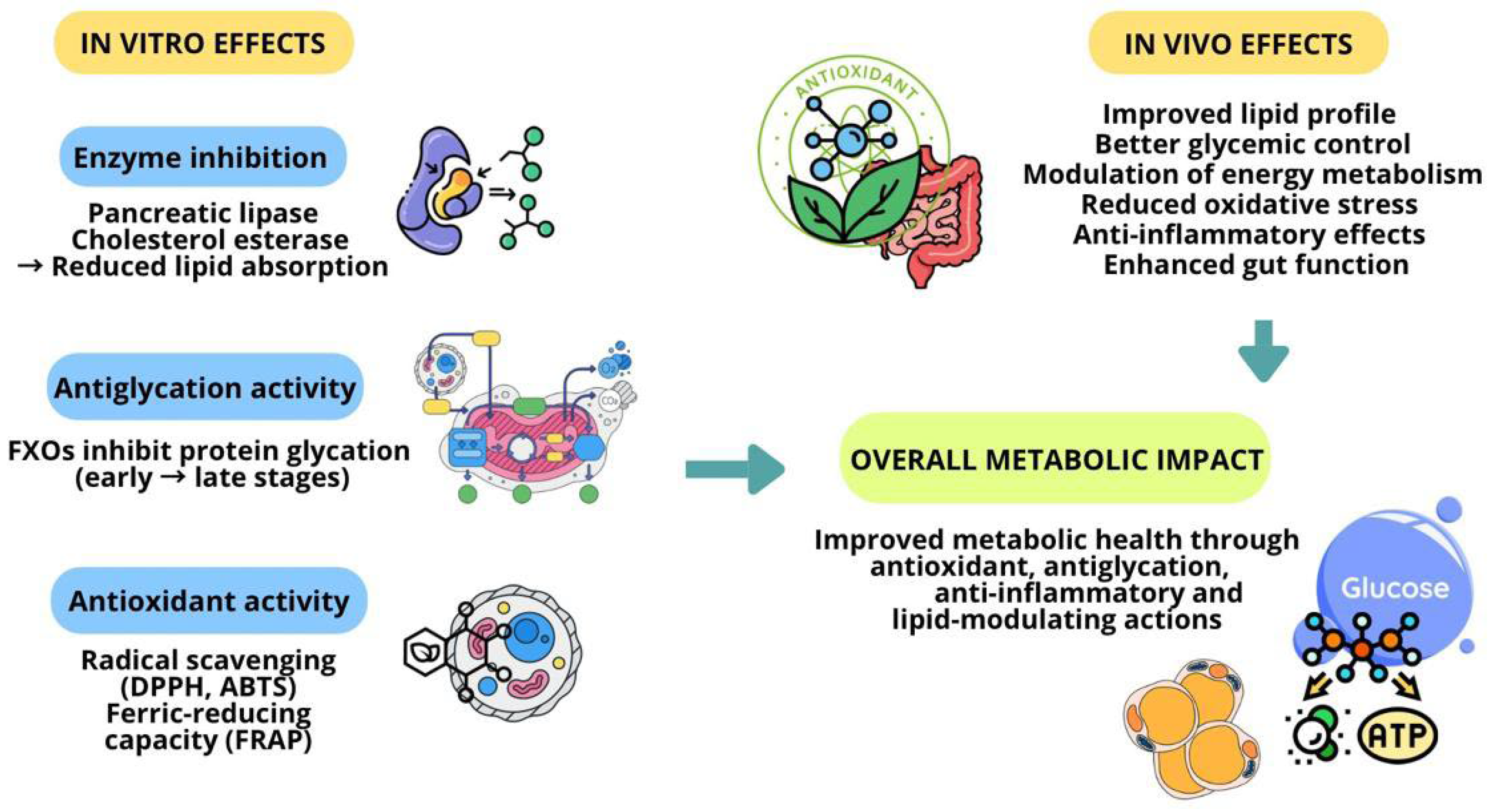

3.3. Conventional Techniques: The Impact on Metabolic Health (In Vivo and In Vitro Studies)

- (a)

- Anti-Obesogenic and Antidiabetic Activities

- (b)

- Anti-Inflammatory Activity

- (c)

- Gut Health

- (d)

- Hepatoprotective and Antidyslipidaemic Activity

- (e)

- Antioxidant Activity

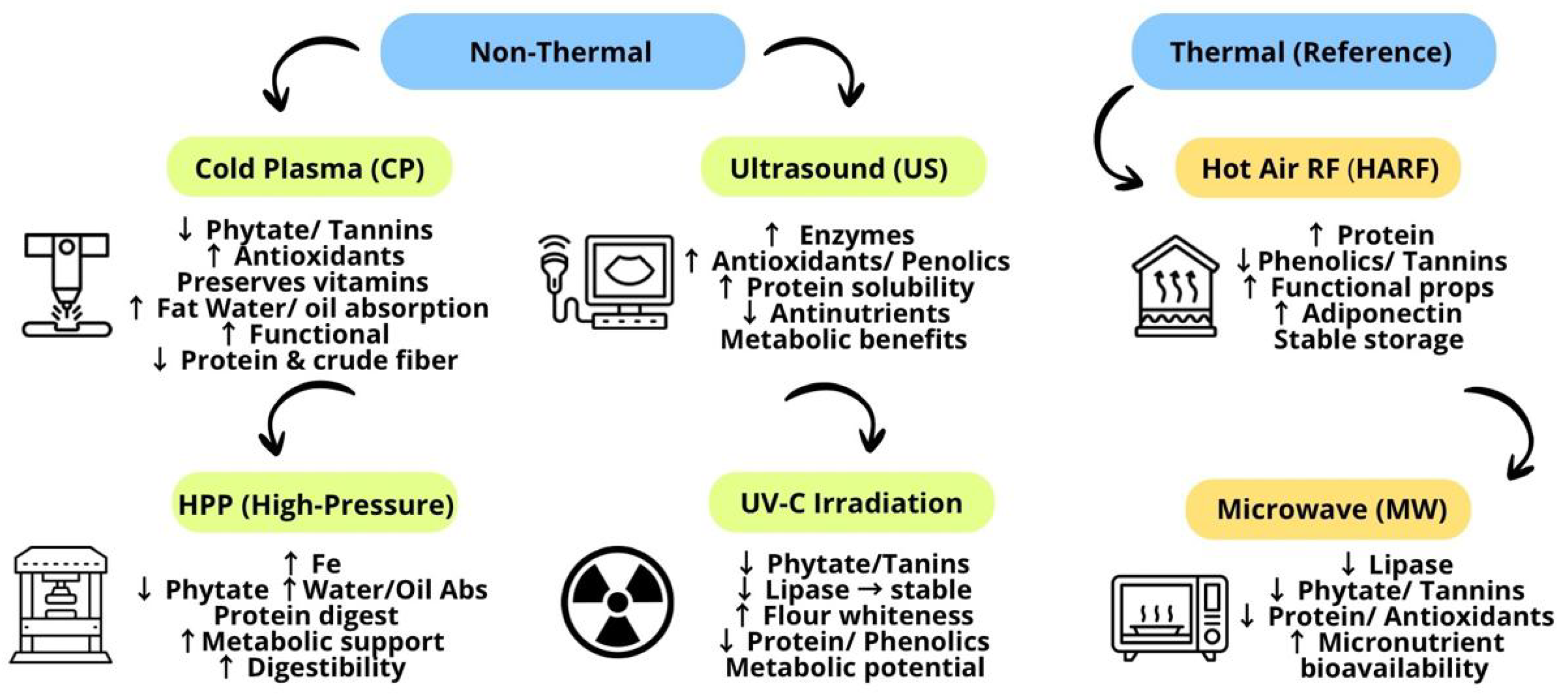

3.4. Advanced Techniques: Innovative Perspectives

3.4.1. Non-Thermal

- (a)

- Cold Plasma (CP)

- (b)

- Ultrasound or Ultrasonication (US)

- (c)

- High-Pressure (HPP)

- (d)

- Ultraviolet (UV) Irradiation

3.4.2. Thermal

- (a)

- Hot-Air-Assisted Radio Frequency (HARF)

- (b)

- Microwave (MW)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pang, G.; Xie, J.; Chen, Q.; Hu, Z. Energy Intake, Metabolic Homeostasis, and Human Health. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2014, 3, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkin, A. The Key Role of Micronutrients. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anil, P.; Nitin, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumari, A.; Chhikara, N. In Functional Foods; Chhikara, N., Panghal, A., Chaudhary, G., Eds.; Food Function and Health Benefits of Functional Foods. Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 419–441. ISBN 978-1-119-77556-0. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, C.D.A.; Lira, J.B.D.; Magalhães, A.L.R.; Silva, T.G.F.D.; Gois, G.C.; Andrade, A.P.D.; Araújo, G.G.L.D.; Campos, F.S. Pearl Millet Cultivation with Brackish Water and Organic Fertilizer Alters Soil Properties. Ciênc. Anim. Bras. 2021, 22, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Martins, A.M.; Pessanha, K.L.F.; Pacheco, S.; Rodrigues, J.A.S.; Carvalho, C.W.P. Potential Use of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) in Brazil: Food Security, Processing, Health Benefits and Nutritional Products. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoro, J.M.V.; Martinez, O.D.M.; Grancieri, M.; Toledo, R.C.L.; Dias Martins, A.M.; Dias, D.M.; Carvalho, C.W.P.; Martino, H.S.D. Germinated Millet Flour (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) Reduces Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Liver Steatosis in Rats Fed with High-Fat High-Fructose Diet. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 99, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Singh, R.; Sehrawat, R.; Kaur, B.P.; Upadhyay, A. Pearl Millet Processing: A Review. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 48, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, N.A.N.; Siliveru, K.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Bhatt, Y.; Netravati, B.P.; Gurikar, C. Modern Processing of Indian Millets: A Perspective on Changes in Nutritional Properties. Foods 2022, 11, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharat, S.; Medina-Meza, I.G.; Kowalski, R.J.; Hosamani, A.; Ramachandra, C.T.; Hiregoudar, S.; Ganjyal, G.M. Extrusion Processing Characteristics of Whole Grain Flours of Select Major Millets (Foxtail, Finger, and Pearl). Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 114, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, P.; Nikhanj, P. A Review on Processing Technologies for Value Added Millet Products. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Umapathy, V.R.; Vengadassalapathy, S.; Hussain, S.F.J.; Rajagopal, P.; Jayaraman, S.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Palanisamy, C.P.; Gopinath, K. A Review of the Potential Consequences of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) for Diabetes Mellitus and Other Biomedical Applications. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, A.I.; Arigbede, T.I.; Makanjuola, S.A.; Oyebode, E.T. Nutritional Compositions, Bioactive Properties, and in-Vivo Glycemic Indices of Amaranth-Based Optimized Multigrain Snack Bar Products. Meas. Food 2022, 7, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, S.; Kumar, M.; Siroha, A.K.; Kennedy, J.F.; Dhull, S.B.; Whiteside, W.S. Pearl Millet Grain as an Emerging Source of Starch: A Review on Its Structure, Physicochemical Properties, Functionalization, and Industrial Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 260, 117776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, M.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kumar, M.; Pal Singh, S.; Krishnan, V.; Kansal, R.; Verma, R.; Yadav, V.K.; Dahuja, A.; Ahlawat, S.P.; et al. Nutritional Composition Patterns and Application of Multivariate Analysis to Evaluate Indigenous Pearl Millet ((Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) Germplasm. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 103, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Rakshit, G.; Singh, R.P.; Garse, S.; Khan, J.; Chakraborty, S. Dietary Polyphenols: Review on Chemistry/Sources, Bioavailability/Metabolism, Antioxidant Effects, and Their Role in Disease Management. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nani, A.; Belarbi, M.; Ksouri-Megdiche, W.; Abdoul-Azize, S.; Benammar, C.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Hichami, A.; Khan, N.A. Effects of Polyphenols and Lipids from Pennisetum glaucum Grains on T-Cell Activation: Modulation of Ca2+ and ERK1/ERK2 Signaling. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.R.N. Pearl Miller: Overview. Encycl. Food Grains 2016, 1, 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.K.; Gangoliya, S.S.; Singh, N.K. Reduction of Phytic Acid and Enhancement of Bioavailable Micronutrients in Food Grains. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babić Leko, M.; Gunjača, I.; Pleić, N.; Zemunik, T. Environmental Factors Affecting Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone and Thyroid Hormone Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.M.; Sebola, N.A.; Mabelebele, M. The Nutritional Use of Millet Grain for Food and Feed: A Review. Agric. Food Secur. 2021, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, F.A.P.; Bondarczuk, B.A.; Gomes, L.D.C.; Jardim, L.D.C.; Corrêa, R.G.D.F.; Baierle, I.C. Advances in Food Quality Management Driven by Industry 4.0: A Systematic Review-Based Framework. Foods 2025, 14, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selladurai, M.; Pulivarthi, M.K.; Raj, A.S.; Iftikhar, M.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Siliveru, K. Considerations for Gluten Free Foods—Pearl and Finger Millet Processing and Market Demand. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2023, 6, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nengparmoi, T.H.; Ghorband, A.S.; Yadav, P.; Sahu, R.; Anbarasan, S.; Reddy, V.S.; Panotra, N. Pearl Millet Processing Methods and Products: An In-Depth Analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2024, 16, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.K.; Malakar, S.; Kumari, S.; Pawar, K.; Kokane, S.B.; Suri, S.; Arora, V.K. Impact of Ultrasound Treatment on Millets—Quality Assessment and Implications: A Review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 7632–7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundassery, A.; Ramaswamy, J.; Natarajan, T.; Haridas, S.; Nedungadi, P. Modern and Conventional Processing Technologies and Their Impact on the Quality of Different Millets. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 2441–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naraharasetti, B.; Chakraborty, S.; Siliveru, K.; Prasad, P.V.V. Thermal and Nonthermal Processing of Pearl Millet Flour: Impact on Microbial Safety, Enzymatic Stability, Nutrients, Functional Properties, and Shelf-Life Extension. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Sharma, D.K.; Arora, A. Prospects of Indian Traditional Fermented Food as Functional Foods. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 88, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Sharma, S.; Singh, B. Modulation in the Bio-Functional & Technological Characteristics, in Vitro Digestibility, Structural and Molecular Interactions during Bioprocessing of Proso Millet (Panicum miliaceum L.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 107, 104372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaza, M.; Shumoy, H.; Muchuweti, M.; Vandamme, P.; Raes, K. Iron and Zinc Bioaccessibility of Fermented Maize, Sorghum and Millets from Five Locations in Zimbabwe. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, A.A.M.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Babiker, E.E.; Ibrahim, M.A.E.M. Effect of Supplementation and Cooking on in Vitro Protein Digestibility and Anti-Nutrients of Pearl Millet Flour. Am. J. Food Sci. Health 2015, 1, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Alwohaibi, A.A.A.; Ali, A.A.; Sakr, S.S.; Mohamed Ahmed, I.A.; Alhomaid, R.M.; Alsaleem, K.A.; Aladhadh, M.; Barakat, H.; Hassan, M.F.Y. Valorization of Different Dairy By-Products to Produce a Functional Dairy–Millet Beverage Fermented with Lactobacillus Paracasei as an Adjunct Culture. Fermentation 2023, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salar, R.K.; Purewal, S.S.; Sandhu, K.S. Fermented Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) with in Vitro DNA Damage Protection Activity, Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Potential. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, D.; Cecchi, L.; Pieraccini, G.; Palchetti, E.; Innocenti, M.; Mulinacci, N. Steryl Ferulates Composition in Twenty-Two Millet Samples: Do “Microwave Popping” and Fermentation Affect Their Content? Food Chem. 2022, 391, 133222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriele, M.; Cavallero, A.; Tomassi, E.; Arouna, N.; Árvay, J.; Longo, V.; Pucci, L. Assessment of Sourdough Fermentation Impact on the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Pearl Millet from Burkina Faso. Foods 2024, 13, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Bhatt, S.; Agrawal, H.; Dadwal, V.; Gupta, M. Effect of Fermentation Conditions on Nutritional and Phytochemical Constituents of Pearl Millet Flour (Pennisetum glaucum) Using Response Surface Methodology. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.B.; Qiao, Z.; Godspower, H.N.; Omedi, J.O.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M.; Rao, Z. Antioxidant and Biotechnological Potential of Pediococcus Pentosaceus RZ01 and Lacticaseibacillus Paracasei RZ02 in a Millet-Based Fermented Substrate. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2023, 3, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi, J.A.; Obadina, A.O.; Adebo, O.A.; Kayitesi, E. Comparison of Nutritional Quality and Sensory Acceptability of Biscuits Obtained from Native, Fermented, and Malted Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) Flour. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, S.A.; Badejo, A.A.; Osundahunsi, O.F.; Edema, M.O. Effect of Preprocessing Techniques on Pearl Millet Flour and Changes in Technological Properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olamiti, G.; Takalani, T.K.; Beswa, D.; Jideani, A.I.O. Effect of Malting and Fermentation on Colour, Thermal Properties, Functional Groups and Crystallinity Level of Flours from Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) and Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). Heliyon 2020, 6, e05467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salar, R.K.; Purewal, S.S.; Bhatti, M.S. Optimization of Extraction Conditions and Enhancement of Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Pearl Millet Fermented with Aspergillus Awamori MTCC-548. Resour.-Effic. Technol. 2016, 2, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, D.; Bellumori, M.; Pucci, L.; Gabriele, M.; Longo, V.; Paoli, P.; Melani, F.; Mulinacci, N.; Innocenti, M. Does Fermentation Really Increase the Phenolic Content in Cereals? A Study on Millet. Foods 2020, 9, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urooj, A. Impact of Household Processing Methods on the Nutritional Characteristics of Pearl Millet (Pennisetumtyphoideum): A Review. MOJ Food Process. Technol. 2017, 4, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, A.; Priyadarshini, C.G.P. Millet Derived Bioactive Peptides: A Review on Their Functional Properties and Health Benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3342–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, L.; Hou, D.; Liaqat, H.; Shen, Q. Millet: A Review of Its Nutritional and Functional Changes during Processing. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purewal, S.S.; Sandhu, K.S.; Salar, R.K.; Kaur, P. Fermented Pearl Millet: A Product with Enhanced Bioactive Compounds and DNA Damage Protection Activity. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Agrawal, S.; Balasubramanian, A.; Maji, S.; Shit, S.; Biswas, P.; Ghosh, S.; Islam, S.S.; Dey, S. Structural Analysis of a Water Insoluble Polysaccharide from Pearl Millet and Evaluating Its Prebiotic Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Zheng, F.; Zeng, X. Yeast β-Glucan, a Potential Prebiotic, Showed a Similar Probiotic Activity to Inulin. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10386–10396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibidapo, O.; Henshaw, F.; Shittu, T.; Afolabi, W. Bioactive Components of Malted Millet (Pennisetum glaucum), Soy Residue “Okara” and Wheat Flour and Their Antioxidant Properties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 1886–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, F.; Jideani, V.A.; Obilana, A.O. Nutritional, Biochemical, and Functional Properties of Pearl Millet and Moringa Oleifera Leaf Powder Composite Meal Powders. Foods 2024, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Panigrahi, C.; Mishra, H.N. Formulation and Characterization of a Low-Cost High-Energy Grain-Based Beverage Premix: A Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm Approach. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Garg, A.P. Effect of Germination on the Physicochemical and Antinutritional Properties of Finger Millet (Eleusine coracana), Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum), and Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). Pharma Innov. J. 2023, 12, 4763–4772. [Google Scholar]

- Terbag, L.; Souilah, R.; Belhadi, B.; Lemgharbi, M.; Djabali, D.; Nadjemi, B. Effects of Extractable Protein Hydrolysates, Lipids, and Polyphenolic Compounds from Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) Whole Grain Flours on Starch Digestibility. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2020, 20, 16922–16940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Chauhan, E.; Sarita, S. Effects of Processing (Germination and Popping) on the Nutritional and Anti-Nutritional Properties of Finger Millet (Eleusine coracana). Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2018, 6, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoro, J.M.V.; Grancieri, M.; Oliveira, L.A.; Lucia, C.M.D.; De Carvalho, I.M.M.; Bragagnolo, F.S.; Rostagno, M.A.; Glahn, R.P.; Carvalho, C.W.P.; Da Silva, B.P.; et al. Chemical Composition and in Vitro Iron Bioavailability of Extruded and Open-Pan Cooked Germinated and Ungerminated Pearl Whole Millet “Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br. Food Chem. 2024, 457, 140170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.J.; Srinivasa Rao, P. Characterization and Multivariate Analysis of Decortication-Induced Changes in Pearl Millet. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 125, 105788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, F.; Icard-Vernière, C.; Guyot, J.-P.; Picq, C.; Diawara, B.; Mouquet-Rivier, C. Changes in Micro- and Macronutrient Composition of Pearl Millet and White Sorghum during in Field versus Laboratory Decortication. J. Cereal Sci. 2011, 54, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.K.; Meena, S.; Joshi, M.; Dhotre, A.V. Nutritional and Functional Exploration of Pearl Millet and Its Processing and Utilization: An Overview. Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompagni, E.; Orozco-Arroyo, G.; Cominelli, E.; Gangashetty, P.I.; Grando, S.; Kwaku Zu, T.T.; Daminati, M.G.; Nielsen, E.; Sparvoli, F. Antinutritional Factors in Pearl Millet Grains: Phytate and Goitrogens Content Variability and Molecular Characterization of Genes Involved in Their Pathways. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Vinutha, T.; Kumar, R.R.; Ansheef Ali, T.P.; Kumar, S.S.; Arun Kumar, T.V.; Aradwad, P.; Sahoo, P.K.; Meena, M.C.; Singh, S.P.; et al. Effect of Different Degrees of Decortication on Pearl Millet Flour Shelf Life, Iron and Zinc Content. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 127, 105927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Asrani, P.; Ansheef Ali, T.P.; Kumar, R.D.; Vinutha, T.; Veda, K.; Kumari, S.; Sachdev, A.; Singh, S.P.; Satyavathi, C.T.; et al. Rancidity Matrix: Development of Biochemical Indicators for Analysing the Keeping Quality of Pearl Millet Flour. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 2147–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Martins, A.M.; Trombete, F.M.; Cappato, L.P.; Chávez, D.W.H.; Santos, M.B.; Carvalho, C.W.P. Processing, Composition, and Technological Properties of Decorticated, Sprouted, and Extruded Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. BR.) Flours. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latha Ravi, J.; Rana, S.S. Maximizing the Nutritional Benefits and Prolonging the Shelf Life of Millets through Effective Processing Techniques: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 38327–38347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emson, B. Cereal Technology. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2003, 18, 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Hotz, C.; Gibson, R.S. Traditional Food-Processing and Preparation Practices to Enhance the Bioavailability of Micronutrients in Plant-Based Diets1. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1097–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, A.C.; Davies, M.I.J.; Moore, H.L. Back to the Grindstone? The Archaeological Potential of Grinding-Stone Studies in Africa with Reference to Contemporary Grinding Practices in Marakwet, Northwest Kenya. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2017, 34, 415–435, Erratum in Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2017, 34, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Meera, M.S. Monitoring Bioaccessibility of Iron and Zinc in Pearl Millet Grain after Sequential Milling. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Tian, Y.; Dhital, S. Starch and Starchy Food Products; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Singh, R.; Upadhyay, A.; Giri, B.S. Application and Functional Properties of Millet Starch: Wet Milling Extraction Process and Different Modification Approaches. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sruthi, N.U.; Rao, P.S. Effect of Processing on Storage Stability of Millet Flour: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, P.; Sundaresan, T.; Kamdi, H.S.; Singh, S.M.; Joshi, T.J.; Rao, P.S. Engineering Interventions, Challenges, and Strategies in Processing and Utilization of Pearl Millet. Food Humanit. 2025, 5, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.; Vanga , S.K.; Wang, J.; Orsat , V.; Raghavan, V. Millets for Food Security in the Context of ClimateChange: A Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2228. [Google Scholar]

- Siroha, A.K.; Sandhu, K.S. Effect of Heat Processing on the Antioxidant Properties of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) Cultivars. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Sehgal, S.; Kawatra, A. The Role of Dry Heat Treatment in Improving the Shelf Life of Pearl Millet Flour. Nutr. Health 2002, 16, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhati, D.; Bhatnagar, V.; Acharya, V. Effect of Pre-Milling Processing Techniques on Pearl Millet Grains with Special Reference to in-Vitro Iron Availability. Asian J. Dairy Food Res. 2016, 35, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmaja, P.G.; Kalaisekar, A.; Venkateswarlu, R.; Shwetha, S.; Rao, B.D.; Tonapi, V.A. Thermal Treatment in Combination with Laminated Packaging under Modified Atmosphere Enhances the Shelf Life of Pearl Millet Flour. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinutha, T.; Kumar, D.; Bansal, N.; Krishnan, V.; Goswami, S.; Kumar, R.R.; Kundu, A.; Poondia, V.; Rudra, S.G.; Muthusamy, V.; et al. Thermal Treatments Reduce Rancidity and Modulate Structural and Digestive Properties of Starch in Pearl Millet Flour. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 195, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadina, A.; Ishola, I.O.; Adekoya, I.O.; Soares, A.G.; De Carvalho, C.W.P.; Barboza, H.T. Nutritional and Physico-Chemical Properties of Flour from Native and Roasted Whole Grain Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum [L.] R. Br.). J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 70, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalgaonkar, K.; Jha, S.K.; Sharma, D.K. Effect of Thermal Treatments on the Storage Life of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) Flour. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 86, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kate, A.; Singh, A. Processing Technology for Value Addition in Millets. In Millets and Millet Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, I.; Kaur, A. Development of a Convenient, Nutritious Ready to Cook Packaged Product Using Millets with a Batch Scale Process Development for a Small-Scale Enterprise. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duodu, K.G. Effects of Processing on Phenolic Phytochemicals in Cereals and Legumes. Cereal Foods World 2014, 59, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.B.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Osman, G.A.; Babiker, E.E. Effect of Processing Treatments Followed by Fermentation on Protein Content and Digestibility of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum typhoideum) Cultivars. Pak. J. Nutr. 2006, 5, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, R.; Chandra, Y.K.; Raviraj, S.C. Development and Quality Evaluation of Little Millet (Panicum sumatrense) Based Extruded Product. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 3457–3463. [Google Scholar]

- Sobowale, S.S.; Kewuyemi, Y.O.; Olayanju, A.T. Process Optimization of Extrusion Variables and Effects on Some Quality and Sensory Characteristics of Extruded Snacks from Whole Pearl Millet-Based Flour. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Ascheri, J.L.; Bazan Colque, J.L.; Borsoi, L.M.; Ramirez Ascheri, D.P.; Melendez Arevalo, A.; Moreira Da Silva, E.M. Extrusion Cooking using Fruits Peels, Whole Cereals and Grains. Glob. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pessanha, K.L.F.; Menezes, J.P.D.; Silva, A.D.A.; Ferreira, M.V.D.S.; Takeiti, C.Y.; Carvalho, C.W.P. Impact of Whole Millet Extruded Flour on the Physicochemical Properties and Antihyperglycemic Activity of Gluten Free Bread. LWT 2021, 147, 111495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessanha, K.L.F.; Santos, M.B.; de Grandi Castro Freitas-Sá, D.; Takeiti, C.Y.; Carvalho, C.W.P. Impact of Whole Millet Extruded Flour on the Physicochemical Properties and Antihyperglycemic Activity of Gluten Free Pasta. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoro, J.M.V.; Martinez, O.D.M.; Grancieri, M.; Toledo, R.C.L.; Binoti, M.L.; Martins, A.M.D.; Carvalho, C.W.P.; Lisboa, P.C.; Martino, H.S.D. Germinated Millet Flour (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. BR.) Improves Adipogenesis and Glucose Metabolism and Maintains Thyroid Function In Vivo. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 6083–6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.-J.; Won, Y.-S.; Kim, E.-K.; Park, S.-I.; Lee, S.J. Free Radicals and Their Impact on Health and Antioxidant Defenses: A Review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurutas, E.B. The Importance of Antioxidants Which Play the Role in Cellular Response against Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress: Current State. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. The Prevention and Control the Type-2 Diabetes by Changing Lifestyle and Dietary Pattern. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2014, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Verma, P.; Saha, S.; Singh, B.; Vinutha, T.; Kumar, R.R.; Kulshreshta, A.; Singh, S.P.; Sathyavathi, T.; Sachdev, A.; et al. Polyphenol-Enriched Extract from Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) Inhibits Key Enzymes Involved in Post Prandial Hyper Glycemia (α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase) and Regulates Hepatic Glucose Uptake. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 43, 102411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, R.; Kaya, A.C.; Goren, H.; Akincioglu, M.; Topal, Z.; Bingol, K.; Cetin Çakmak, S.B.; Ozturk Sarikaya, L.; Durmaz, S. Alwasel Anticholinergic, Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Activities of Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) Bark Extracts: Polyphenol Contents Analysis by LC-MS/MS. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 1511–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruygur, N.; Koçyiğit, U.M.; Taslimi, P.; Atas, M.E.H.M.E.T.; Tekin, M.; Gülçin, İ. Screening the in Vitro Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anticholinesterase, Antidiabetic Activities of Endemic Achillea Cucullata (Asteraceae) Ethanol Extract. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 120, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Martins, A.M.; Cappato, L.P.; Da Costa Mattos, M.; Rodrigues, F.N.; Pacheco, S.; Carvalho, C.W.P. Impacts of Ohmic Heating on Decorticated and Whole Pearl Millet Grains Compared to Open-Pan Cooking. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 85, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, S.; Kane-Potaka, J.; Tsusaka, T.W.; Botha, R.; Rajendran, A.; Givens, D.I.; Parasannanavar, D.J.; Subramaniam, K.; Prasad, K.D.V.; Vetriventhan, M.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Potential of Millets for Managing and Reducing the Risk of Developing Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 687428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada, N.H.; Tanko, Y.; Gidado, N.M. Antidiabetic Effect of Fermented Pennisetum glaucum (Millet) Supplement in Alloxan Induced Hyperglycemic Wistar Rats. Bayero J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2016, 9, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Melo, S.R.; Dos Santos, L.R.; Da Cunha Soares, T.; Cardoso, B.E.P.; Da Silva Dias, T.M.; Morais, J.B.S.; De Paiva Sousa, M.; De Sousa, T.G.V.; Da Silva, N.C.; Da Silva, L.D.; et al. Participation of Magnesium in the Secretion and Signaling Pathways of Insulin: An Updated Review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 3545–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zou, H.; Huo, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, Y. Emerging Roles of Selenium on Metabolism and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1027629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillehoj, H.; Liu, Y.; Calsamiglia, S. Phytochemicals as Antibiotic Alternatives to Promote Growth and Enhance Host Health. Veter. Res. 2018, 49, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-J.; Lai, Y.-H.; Manne, R.K.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Sarbassov, D.; Lin, H.-K. Akt: A Key Transducer in Cancer. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 76, Erratum in J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 30, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Cardoso, K.; Comitato, R.; Ginés, I. Protective Effect of Proanthocyanidins in a Rat Model of Mild Intestinal Inflammation and Impaired Intestinal Permeability Induced by LPS. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1800720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, L.; Miguélez, E.M.; Villar, C.J. Bioavailability of Dietary Polyphenols and Gut Microbiota Metabolism: Antimicrobial Properties. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 905215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, C.B.; Tokas, J.; Yadav, D.; Winters, A.; Singh, R.B.; Yadav, R.; Gangashetty, P.I.; Srivastava, R.K.; Yadav, R.S. Identifying Anti-Oxidant Biosynthesis Genes in Pearl Millet [Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.] Using Genome—Wide Association Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 599649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavhare, S.D. Millets as a Dietary Supplement for Managing Chemotherapy Induced Side Effects. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2024, 15, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoro, J.M.V.; Da Silva, L.A.; De São José, V.P.B.; Willis, N.B.; Toledo, R.C.L.; Grancieri, M.; Carvalho, C.W.P.; Pierre, J.F.; Da Silva, B.P.; Martino, H.S.D. Processed Pearl Millet Improves the Morphology and Gut Microbiota in Wistar Rats. Foods 2025, 14, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas-Barberan, F.A.; Selma, M.V.; Espín, J.C. Polyphenols’ Gut Microbiota Metabolites: Bioactives or Biomarkers? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3593–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoro, J.M.V.; Grancieri, M.; Gomes, M.J.C.; Toledo, R.C.L.; De São José, V.P.B.; Mantovani, H.C.; Carvalho, C.W.P.; Da Silva, B.P.; Martino, H.S.D. Germinated Millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) Flour Improved the Gut Function and Its Microbiota Composition in Rats Fed with High-Fat High-Fructose Diet. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, N.S.; Alshammari, G.M.; El-Ansary, A.; Yagoub, A.E.A.; Amina, M.; Saleh, A.; Yahya, M.A. Anti-Hyperlipidemia, Hypoglycemic, and Hepatoprotective Impacts of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) Grains and Their Ethanol Extract on Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, D.; Cecchi, L.; Pieraccini, G.; Venturi, M.; Galli, V.; Reggio, M.; Di Gioia, D.; Furlanetto, S.; Orlandini, S.; Innocenti, M.; et al. Millet Fermented by Different Combinations of Yeasts and Lactobacilli: Effects on Phenolic Composition, Starch, Mineral Content and Prebiotic Activity. Foods 2023, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rajoriya, D.; Obalesh, I.S.; Harish Prashanth, K.V.; Chaudhari, S.R.; Mutturi, S.; Mazumder, K.; Eligar, S.M. Arabinoxylan from Pearl Millet Bran: Optimized Extraction, Structural Characterization, and Its Bioactivities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, M.N.; Akhtar, M.S. Blood Pressure Lowering Effect of Pennisetum glaucum in Rats. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2015, 10, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukar, K.A.O.; Abdalla, R.I.; Humeda, H.S.; Alameen, A.O.; Mubarak, E.I. Effect of Pearl Millet on Glycaemic Control and Lipid Profile in Streptozocin Induced Diabetic Wistar Rat Model. Asian J. Med. Health 2020, 18, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Panesar, P.S.; Kaur, B.; Riar, C.S. Hydrothermal Extraction of Dietary Fiber from Pearl Millet Bran: Optimization, Physico-Chemical, Structural and Functional Characterization. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 1536–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, A.; Cherif, A.; Sakouhi, F.; Boukhchina, S.; Radhouane, L. Fatty Acids, Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Potential of Pearl Millet Oil. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf. 2020, 15, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Patar, S.; Sharma, A.; Bhateria, R.; Kumar Bhardwaj, A.; Kashyap, R.; Bhukal, S. Surface Modified Novel Synthesis of Spirulina Assisted Mesoporous TiO2@CTAB Nanocomposite Employed for Efficient Removal of Chromium (VI) in Wastewater. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 679, 161309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Tiwari, P. Millets: The Untapped and Underutilized Nutritious Functional Foods. Plant Arch. 2019, 19, 875–883. [Google Scholar]

- Mudgil, P.; Alblooshi, M.; Singh, B.P.; Devarajan, A.R.; Maqsood, S. Pearl Millet Protein Hydrolysates Exhibiting Effective In-Vitro Antioxidant, Antidiabetic and Anti-Lipidemic Properties as Potential Functional Food Ingredient. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 3264–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howles, P.N.; Carter, C.P.; Hui, D.Y. Dietary Free and Esterified Cholesterol Absorption in Cholesterol Esterase (Bile Salt-Stimulated Lipase) Gene-Targeted Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 7196–7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Eligar, S.M. Bioactive Feruloylated Xylooligosaccharides Derived from Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) Bran with Antiglycation and Antioxidant Properties. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 5695–5706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, D.; Froehling, A.; Jaeger, H.; Reineke, K.; Schlueter, O.; Schoessler, K. Emerging Technologies in Food Processing. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 203–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouryieh, H.A. Novel and Emerging Technologies Used by the U.S. Food Processing Industry. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 67, 102559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.; Eldridge, A.L.; Hartmann, C.; Klassen, P.; Ingram, J.; Meijer, G.W. Benefits and Challenges of Food Processing in the Context of Food Systems, Value Chains and Sustainable Development Goals. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 153, 104703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H.B.; Annapure, U.S.; Deshmukh, R.R. Non-Thermal Technologies for Food Processing. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 657090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokusoglu, O. Introduction to Innovative Food Processing and Technology. Nat. Sci. Discov. 2015, 1, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dong, X.; Wang, J.; Raghavan, V. Critical Reviews and Recent Advances of Novel Non-Thermal Processing Techniques on the Modification of Food Allergens. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokeswari, R.; Sharanyakanth, P.S.; Jaspin, S.; Mahendran, R. Cold Plasma Effects on Changes in Physical, Nutritional, Hydration, and Pasting Properties of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum). IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2021, 49, 1745–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Niranjan, T.; Patel, G.; Kheto, A.; Tiwari, B.K.; Dwivedi, M. Impact of Cold Plasma Treatment on Nutritional, Antinutritional, Functional, Thermal, Rheological, and Structural Properties of Pearl Millet Flour. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolouie, H.; Mohammadifar, M.A.; Ghomi, H.; Hashemi, M. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Manipulation of Proteins in Food Systems. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2583–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charu, C.; Vignesh, S.; Chidanand, D.V.; Mahendran, R.; Baskaran, N. Impact of Cold Plasma on Pearl and Barnyard Millets’ Microbial Quality, Antioxidant Status, and Nutritional Composition. Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthewman, M.C.; Costa-Pinto, R. Macronutrients, Minerals, Vitamins and Energy. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 24, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, A.-L.; Pouteau, E.; Marquez, D.; Yilmaz, C.; Scholey, A. Vitamins and Minerals for Energy, Fatigue and Cognition: A Narrative Review of the Biochemical and Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2020, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheltova, A.A.; Kharitonova, M.V.; Iezhitsa, I.N.; Spasov, A.A. Magnesium Deficiency and Oxidative Stress: An Update. Bio-Medicine 2016, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, J.B.S.; Severo, J.S.; Santos, L.R.D.; De Sousa Melo, S.R.; De Oliveira Santos, R.; De Oliveira, A.R.S.; Cruz, K.J.C.; Do Nascimento Marreiro, D. Role of Magnesium in Oxidative Stress in Individuals with Obesity. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 176, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.S.; Bao, B. Molecular Mechanisms of Zinc as a Pro-Antioxidant Mediator: Clinical Therapeutic Implications. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, N.; Mor, R.S.; Kumar, K.; Sharanagat, V.S. Advances in Application of Ultrasound in Food Processing: A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 70, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidhyalakshmi, R.; Prabhasankar, P.; Meera, M.S. Ultrasonication Assisted Pearl Millet Starch-Germ Complexing: Evaluation of Starch Characteristics and Its Influence on Glycaemic Index of Bread. J. Cereal Sci. 2023, 112, 103686, Erratum in J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 119, 104000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidhyalakshmi, R.; Meera, M.S. Dry Heat and Ultrasonication Treatment of Pearl Millet Flour: Effect on Thermal, Structural, and in-Vitro Digestibility Properties of Starch. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 2858–2868, Erratum in J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arp, C.G.; Correa, M.J.; Ferrero, C. Resistant Starches: A Smart Alternative for the Development of Functional Bread and Other Starch-Based Foods. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 121, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaltham, M.S.; Qasem, A.A.; Ibraheem, M.A.; Hassan, A.B. Exploring Ultrasonic Energy Followed by Natural Fermentation Processing to Enhance Functional Properties and Bioactive Compounds in Millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) Grains. Fermentation 2024, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešlo, D.; Golubić, N.; Rastija, V.; Agić, D.; Karnaš, M.; Šubarić, D.; Lučić, B. Antioxidant Activity, Metabolism, and Bioavailability of Polyphenols in the Diet of Animals. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himashree, P.; Mahendran, R. Effect of High-Pressure Soaking on the Physicochemical, Nutritional, and Techno-Functional Properties of Pearl Millets. Sustain. Food Technol. 2025, 3, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Jin, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yue, J.; Song, X.; Zhao, Y. Impact of Continuous or Cycle High Hydrostatic Pressure on the Ultrastructure and Digestibility of Rice Starch Granules. J. Cereal Sci. 2014, 60, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.N.; Vicente, A.A. Environmental Impact of Novel Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies in Food Processing. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1936–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, K.R.; Buvaneswaran, M.; Bhavana, M.R.; Sinija, V.R.; Rawson, A.; Hema, V. Effects of Ultrasound and High-Pressure Assisted Extraction of Pearl Millet Protein Isolate: Functional, Digestibility, and Structural Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 289, 138877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashanth, P.; Joshi, T.J.; Singh, S.M.; Rao, P.S. Effect of UV-C Treatment on Proximate Composition, Antinutrients and Flour Properties of Pearl Millet Flour. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 1645–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarrakula, S.; Mummaleti, G.; Toleti, K.S.; Saravanan, S. Functional Characteristics and Storage Stability of Hot Air Assisted Radio Frequency Treated Pearl Millet. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2024, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, T.; Joshi, J.; Rao, P.S. Characterisation and Multivariate Analysis of Changes in Quality Attributes of Microwave-Treated Pearl Millet Flour. J. Cereal Sci. 2025, 121, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.B.; Von Hoersten, D.; Mohamed Ahmed, I.A. Effect of Radio Frequency Heat Treatment on Protein Profile and Functional Properties of Maize Grain. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Johnson, J.; Gao, M.; Tang, J.; Powers, J.R.; Wang, S. Developing Hot Air-Assisted Radio Frequency Drying for In-Shell Macadamia Nuts. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.D.; Hirsch, K.R.; Park, S.; Kim, I.-Y.; Gwin, J.A.; Pasiakos, S.M.; Wolfe, R.R.; Ferrando, A.A. Essential Amino Acids and Protein Synthesis: Insights into Maximizing the Muscle and Whole-Body Response to Feeding. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Huenchullan, S.F.; Tam, C.S.; Ban, L.A.; Ehrenfeld-Slater, P.; Mclennan, S.V.; Twigg, S.M. Skeletal Muscle Adiponectin Induction in Obesity and Exercise. Metabolism 2020, 102, 154008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira Moura, L.d.S.; Guimarães, R.d.C.A.; Inada, A.C.; Donadon, J.R.; Pott, A.; Ferreira, R.d.S.; Fernandes, C.D.P.; Costa, C.d.M.; Moura, F.d.S.; Freitas, K.d.C.; et al. Conventional and Advanced Processing Techniques and Their Effect on the Nutritional Quality and Antinutritional Factors of Pearl Millet Grains: The Impact on Metabolic Health. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121460

Oliveira Moura LdS, Guimarães RdCA, Inada AC, Donadon JR, Pott A, Ferreira RdS, Fernandes CDP, Costa CdM, Moura FdS, Freitas KdC, et al. Conventional and Advanced Processing Techniques and Their Effect on the Nutritional Quality and Antinutritional Factors of Pearl Millet Grains: The Impact on Metabolic Health. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121460

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira Moura, Letícia da Silva, Rita de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães, Aline Carla Inada, Juliana Rodrigues Donadon, Arnildo Pott, Rosângela dos Santos Ferreira, Carolina Di Pietro Fernandes, Caroline de Moura Costa, Fernando dos Santos Moura, Karine de Cássia Freitas, and et al. 2025. "Conventional and Advanced Processing Techniques and Their Effect on the Nutritional Quality and Antinutritional Factors of Pearl Millet Grains: The Impact on Metabolic Health" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121460

APA StyleOliveira Moura, L. d. S., Guimarães, R. d. C. A., Inada, A. C., Donadon, J. R., Pott, A., Ferreira, R. d. S., Fernandes, C. D. P., Costa, C. d. M., Moura, F. d. S., Freitas, K. d. C., Bogo, D., do Nascimento, V. A., & Hiane, P. A. (2025). Conventional and Advanced Processing Techniques and Their Effect on the Nutritional Quality and Antinutritional Factors of Pearl Millet Grains: The Impact on Metabolic Health. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121460