Abstract

The Yucca genus encompasses about 50 species native to North America. Species within the Yucca genus have been used in traditional medicine to treat pathologies related to inflammation. Despite its historical use and the popular notion of its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, there is a limited amount of research on this genus. To better understand these properties, this work aimed to analyze phytochemical composition through documentary research. This will provide a better understanding of the molecules and the mechanisms of action that confer such antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. About 92 phytochemicals present within the genus have reported antioxidant or anti-inflammatory effects. It has been suggested that the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties are mainly generated through its free radical scavenging activity, the inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolism, the decrease in TNF-α (Tumor necrosis factor-α), IL-6 (Interleukin-6), iNOS (Inducible nitric oxide synthase), and IL-1β (Interleukin 1β) concentration, the increase of GPx (Glutathione peroxidase), CAT (Catalase), and SOD (Superoxide dismutase) concentration, and the inhibition of the MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase), and NF-κB (Nuclear factor kappa B), and the activation of the Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor) signaling pathway. These studies provide evidence of its use in traditional medicine against pathologies related to inflammation. However, more models and studies are needed to properly understand the activity of most plants within the genus, its potency, and the feasibility of its use to help manage or treat chronic inflammation.

1. Introduction

The Yucca genus belongs to the Agavoideae subfamily, a subfamily that is commonly used in traditional medicine thanks to its anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antiparasitic properties [1]. It encompasses about 40 to 50 species, most of which are native to southern North America. These plants have been used for centuries to treat different ailments [2]. These benefits led to the approval by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) of the use of Yucca species in various products, especially in dietary supplements [3]. These benefits have attracted research into the genus, which has demonstrated the presence of many biological properties [2].

One of Yucca’s most notable properties is its anti-inflammatory activity. Inflammation is a physiological procedure generated by the immune system in response to tissue injury, stress, pathogens, or toxic compounds [4]. However, in some cases, inflammation can become harmful to the body, such as chronic inflammatory diseases [5], and in those cases, the inflammatory response must be suppressed. The inflammatory process generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which can cause oxidative stress [5]. Oxidative stress occurs when those oxidative molecules surpass the antioxidant system, and this will damage or affect the function of proteins, lipids, DNA, or RNA [6]; for the same reason, treatment with antioxidants has been shown to help treat inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease [7].

Treatment against these diseases is usually anti-inflammatory. Unfortunately, there are some drug-induced side effects that make some treatments inadequate [7], and there has been a tendency to use traditional plant-based remedies to partially treat inflammatory diseases. Some of these plants have been Yucca species, as they are popularly used to treat arthritis since they counteract some effects of this disease. All of the biological properties of plants are due to the high concentration of phytochemicals [2]. However, to better understand the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities within the genus, it is necessary to understand the phytochemical composition and how they act.

Therefore, the objective of this work is to research the phytochemical composition of the species and the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of these molecules. The literature was explored during the period from 2000 to 2022, although the oldest papers were used for the historical context. In this way, it will be possible to know the possible molecules responsible for these effects and their mechanisms of action.

2. Yucca Genus

Yucca species are native from North and Central America [8], and these plants are tolerant to drought, wind, and salt, which is why most of these species thrive in the arid zones of the USA and Mexico [9]. The genus is known for its obligate pollination mutualism with Yucca moths, where the moths provide Yucca with pollen while using the flower to oviposit [8]. Hybridization is common among species, which makes species classification difficult [10].

The literature indicates that the Yucca genus is composed of about 50 species. In particular, “The Plant List” establishes 49 species with an “accepted” status [11]. Although each species has each morphological characteristic, in general, they are long-lived perennials, tree-shaped, with white flowers, and sword-shaped leaves that grow in rosettes [8].

3. Ethnobotanical Use

Since ancient times, Yucca species have been used by natives for many purposes. Some species, such as Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies, were used for bowstrings, nets, ropes, mats, sandals, and clothing [12]. It is also used as food; an example is that in eastern Costa Rica, there is a tradition where they eat the Itabo flower (Yucca elephantipes Regel) at Easter [13]. Most importantly, these species have been used in traditional medicine. The Cheyenne cultures used Yucca glauca Nutt to stimulate hair growth, and in skin conditions [14]. New Mexico healers use it to treat asthma and headaches [15]. There are also more modern claims of its ethnobotanical use to treat asthma, rheumatism, gonorrhea, sunburns, arthritis, etc. [2,16].

These ethnobotanical uses have led to the emergence of research on their biological activities. Starting in 1975, it was tested as a treatment to manage arthritis [17]. Ever since, hypocholesterolemic activity [18], antimicrobial activity [19], antiprotozoal activity [20], antioxidant activity [21], anti-inflammatory activity [16], and many others have been tested for this genus. The literature especially highlights its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity. As mentioned before, all these properties are generated through phytochemicals. Therefore, knowing these molecules allows us to gain a better understanding of their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity.

4. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities

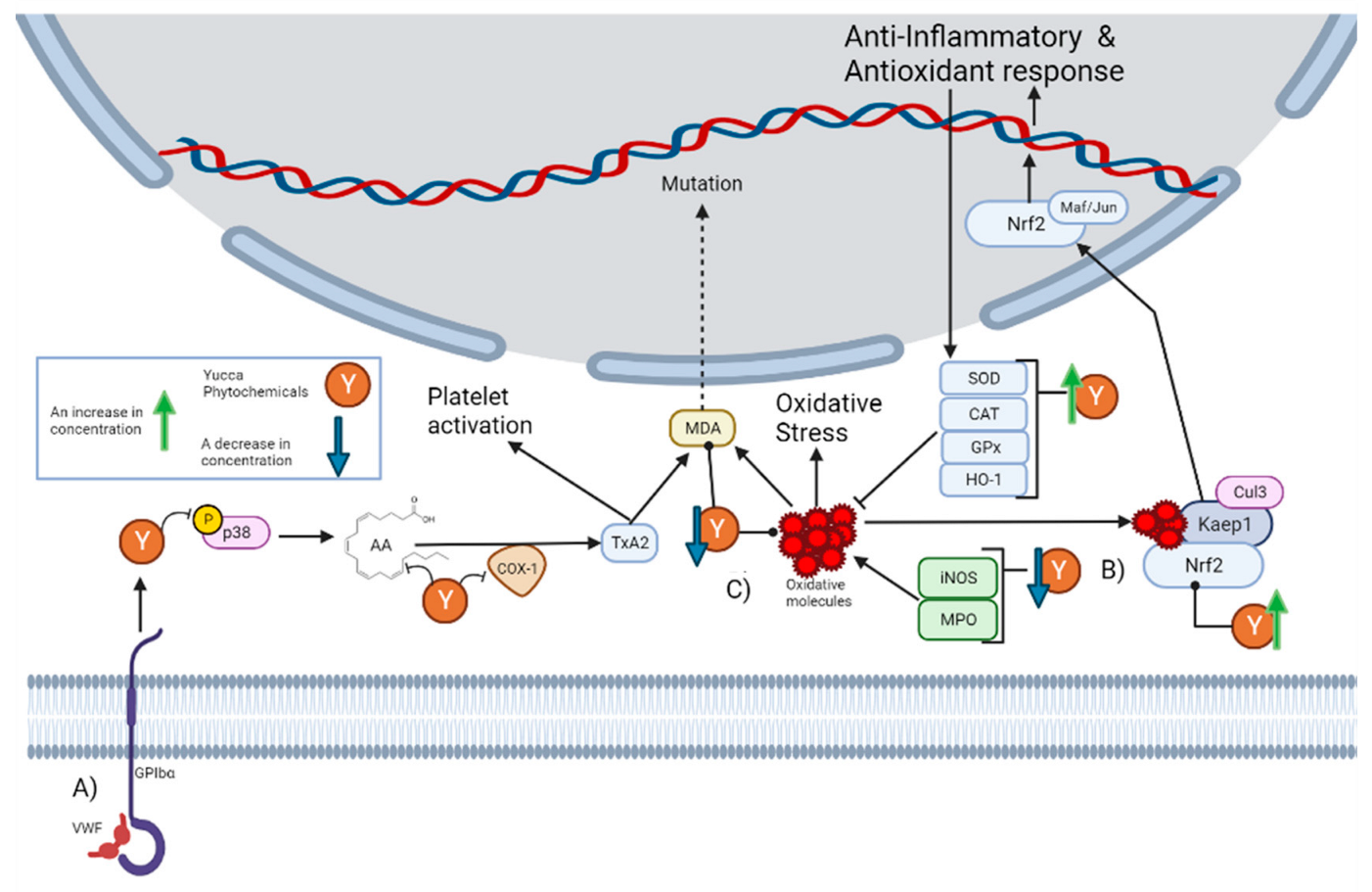

Despite historical ethnobotanical use, its continuous mention in the literature, and the popular notion of its anti-inflammatory properties, a minimal number of current studies have explored these properties. The most mentioned activity in the literature is the anti-platelet effect of Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies. Platelets are specialized blood cells that play an important role in inflammation. Platelets are capable of upregulating leukocyte functions and releasing proinflammatory cytokines [22]. It has been reported that alcoholic extract from Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies significantly decreases the various steps of thrombin-platelet activation [23]. The platelet activation pathway begins with stimulation originating from the von Willebrand factor (VWF) to the platelet adhesion receptor glycoprotein (GPIbα), which generates the phosphorylation of P38. This leads to the subsequent release of arachidonic acid (AA), which is then converted into the platelet activator thromboxane A2 (TxA2) by cyclo-oxygenase 1 (COX-1) [24]. As can be seen in Section 5, there are phytochemicals within the genus that can interrupt this pathway. First, n-3 fatty acids can prevent the generation of arachidonic acids [25]. Then, there are molecules that can decrease the concentration of p38, while others inhibit its phosphorylation. There are also molecules that inhibit COX-1 activity and others that decrease its concentration. In fact, it has been reported that the alcoholic extract from Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies inhibits COX-1 and COX-2 (Cyclooxygenase-2) in vitro [26]. This is graphically represented in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

This figure illustrates how the Yucca genus phytochemicals influence anti-inflammatory and antioxidant processes through: (A) The platelet activation pathway begins with VWF binding to the GPIbα, which generates the phosphorylation of p38. This leads to the subsequent release of AA, which is converted by COX-1 to the platelet activator TxA2, forming MDA as a residue. MDA can react with DNA-inducing mutations. Yucca genus phytochemicals can interrupt this pathway by preventing the generation of arachidonic acid, decreasing the concentration of p38, or inhibiting its phosphorylation and COX-1 activity. (B) Yucca genus phytochemicals have the capacity to eliminate oxidative stress. This is due to the upregulation of HO-1, GPx, CAT, and SOD. By reducing the concentration of MPO and iNOS. The free radical scavenging activity of many Yucca genus phytochemicals reduces the concentration of oxidative molecules, such as MDA. (C) Nrf2 is regulated by Keap1 and the Cul3 ubiquitin E3 ligase complex. Nrf2 can be activated by oxidative molecules that modify the cysteine residues of Keap1. Once Nrf2 is free, it translocates to the nucleus, and heterodimerizes with small Maf or Jun proteins to generate an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory response. Yucca genus phytochemicals can activate this pathway. The figure was created with BioRender.com.

The anti-inflammatory effect of Yucca gloriosa L., specifically its inhibitory potential against Ovalbumin-Induced Airway Hyperresponsiveness in mice [16] has also been reported. Thus, the alcoholic extract of Yucca gloriosa L. was administered orally at doses of 50, 100, or 200 mg/kg for 7 days 1 h before each sensitization with ovalbumin. Pretreatment with Yucca gloriosa L. significantly decreased the concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, interleukin-13 (IL-13), and leucocyte count.A similar effect to that reported for various phytochemicals found within the genus, as can be seen in Section 5. Repeated exposure to ovalbumin mimics the symptoms of asthma [27]. Thus, it suggests a possible use of Yucca gloriosa L. against asthma.

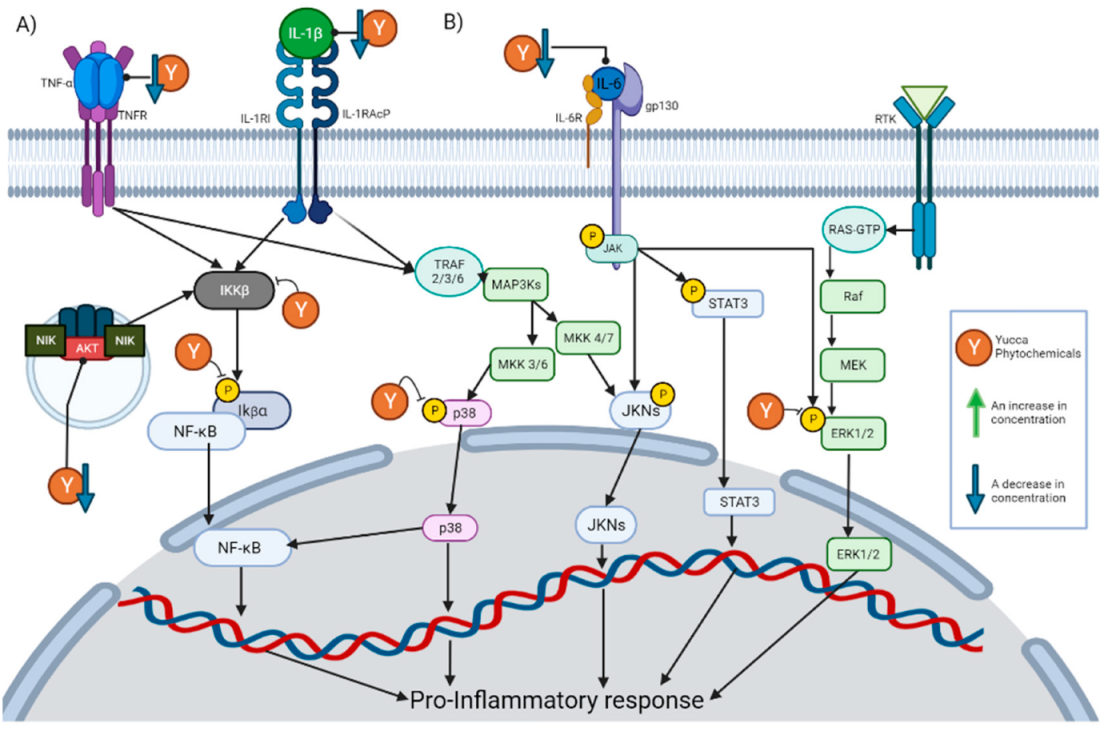

Specifically, the decrease in the TNF-α concentration is the effect with the highest incidence within these compounds. This is expected due to the key role that it plays in inflammation. TNF-α is released by a wide variety of immune cells so that it can bind to its receptors and activate different pathways. Once TNF-α has bound to its receptor, it promotes the formation of a complex capable of activating IκBα kinase (IKK) [28]. Once activated, IKK will phosphorylate IκB (Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B), which would cause the degradation of IκB and the release of NF-κB [29]. The release of NF-κB will allow its nuclear translocation and the activation of said signaling cascade. There are other pathways that can be induced by TNF-α, such as the c-Jun amino terminal kinase (JNK), p38-MAPK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and AKT pathways [28]. Inhibition of all these pathways has also been reported for the phytochemicals described in Section 5. This is graphically represented in Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

This figure illustrates how the Yucca genus phytochemicals influence anti-inflammatory and antioxidant processes through: (A) The NF-kB pathway can be canonically activated by cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1 β, or uncanonically by the endosome complex containing NIK, AKT, and MAC. The pathway begins in the activation of IKK β, which phosphorylate IκBα. This results in the release of NF-kB dimers, translocating to the nucleus and activating the transcription of proinflammatory proteins. Yucca genus phytochemicals can interrupt this pathway by reducing the concentration of TNF-α, IL-1, and AKT, or the inhibition of IKK activation and phosphorylation IκBα. (B) There are 3 MAPK pathways, the ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAP kinase. The p38 MAPK pathway begins the activation of receptors, such as TNFR or the IL1R superfamily. This activation will generate the phosphorylation of TRAF 2/3/6 which in turn activates MAP3Ks, which phosphorylates MKK3 or MKK6, and those molecules will activate p38. P38 positively regulates a pro-inflammatory response. In addition, p38 partially modulates the activation of the basal transcription factors that interact with NF-κB. Yucca genus phytochemicals can reduce p38 phosphorylation, inhibiting the signaling pathway. The activation of JNK begins with the phosphorylation of MAP3Ks, which subsequently phosphorylates MKK7 or MKK4, and then phosphorylates the JNK kinases. JNK positively regulates a pro-inflammatory response. IL-6 can activate JNK pathway and STAT3 pathways by activating membrane-bound gp130, which will cause JAK enzymes to phosphorylate proteins such as STAT3. Yucca genus phytochemicals decrease the activation of this pathway. ERK1/2 signaling begins with the binding of a ligand to the RTK; this will activate the G-protein known as Ras. Ras directly binds to Raf and activates it, then Raf activates MEK, and MEK phosphorylates ERK1/2 so it can enter the nucleus and activate transcription factors. Yucca genus phytochemicals have the capacity to suppress this signaling pathway. The figure was created with BioRender.com.

Another of the effects with a high incidence is a decrease in the concentration of IL-6. IL-6 exerts its activity by binding to the IL-6 receptor, thereby activating membrane-bound gp130. This causes JAK enzymes to phosphorylate gp130, thus generating docking sites for proteins, such as STAT3, to bind to and be phosphorylated by JAK enzymes [30]. In this way, signaling pathways, such as MAPK and JAK/STAT3, are initiated. This is graphically represented in Figure 2B.

In addition to these proinflammatory mediators, treatment with Yucca gloriosa L. also decreased the concentration of the oxidative markers nitric oxide (NO), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and malonaldehyde (MDA) [16]. As can be seen in Section 5, the decrease in NO concentration is frequently mentioned, as in Yuccaol A [28]. NO acts as a mediator of inflammatory processes. It is synthesized by the enzymes nitric oxide synthase (NOS) from L-arginine, especially in the context of inflammation; the inducible isoform of NOS (iNOS) is mainly responsible for its production [31]. Although there are several pathways that result in the expression of iNOS, the literature highlights that the transcription factors NF-kB and STAT-1α are essential for its expression in most cases [32]. The main role of NO in inflammation is to react with superoxide anions to form peroxynitrite [31]. However, it is also involved in some regulatory mechanisms since it can react with transition metals or induce nitrosylation within proteins and regulate their activity [31]. Excessive production of NO is present in pathologies, such as hypertension or atherosclerosis [33]. The ability to inhibit iNOS expression stands out due to Yuccaol C, a molecule proper to the genus that has the capacity to reduce the expression of iNOS in J774.A1 macrophages at 1 µM [34]. There are also other phytochemicals within the genus that produce the same effect (Figure 1B).

In addition to NO reduction, many phytochemicals also reported a significant capacity for reducing the concentration of MDA and MPO, known biomarkers of oxidative stress. MPO is a key enzyme in the elimination of pathogens within phagolysosomes of neutrophils, since it generates powerful oxidizing species, such as hypochlorous acid (HOCl), from the catalysis of the reaction of chloride with hydrogen peroxide [35]. HOCl can generate modifications against pathogens’ lipids, DNA, and proteins, but due to this activity, it can also damage host tissue and is involved in inflammatory diseases, such as atherosclerosis [36]. HOCL can react with phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) and form PE-monochloramine or PE-dichloramine, which are plausible initiators of lipid peroxidation [37]. Lipid peroxidation is the process by which oxidants attack lipids, especially polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), in the lipid membrane [38]. The peroxidation of PUFAs forms lipid peroxides, which are unstable and decompose to a series of compounds, such as MDA. MDA is formed by the decomposition of arachidonic acid AA during the biosynthesis of TxA2 or by bicyclic endoperoxides during polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation [38]. MDA levels are a widely used indicator of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, and high levels are associated with various health disorders, such as in lung cancer patients or glaucoma patients [39]. This may be due to the fact that MDA reacts with DNA to form adducts, which have been reported to frequently induce mutations in oncogenes [40]; this is graphically represented in Figure 1A.

There are other reports of the antioxidant activity of the Yucca genus against oxidative stress. A commercially available food additive known as Sarsaponin 30® has been reported to have a protective effect against nitrite-induced oxidative stress in rats [41]. Rats were pretreated with Sarsaponin 30® for 4 weeks prior to the nitrite intoxication in doses of 100 ppm. Said pretreatment reduced the concentrations of MDA and NO in the tissue and in glutathione (Figure 1B).

In addition to rats, dietary supplementation with Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies a has also shown antioxidant capacity against oxidative stress in fish. In Oreochromis niloticus Biodust®; other food additives from Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies alleviate growth arrest, intestinal dysfunction, and oxidative damage induced by heat stress [42]. This is done by the downregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, TNF-α, IL-1β, and interleukin 8 (IL-8), as well as by enhancing the Nrf2 signaling pathway. As can be seen in Section 5, the decrease of IL-1β concentration is an effect well represented through phytochemicals within the genus. IL-1 refers to two separate cytokine genes, IL-1α and IL-1β, that bind to the same receptors and stimulate similar proinflammatory signals [43]. For IL-1β to be excreted, its precursor must be processed by caspase-1 from the NALP3 inflammasome and excreted by the ATP/P2X7R influx [44]. In the same way, within the described phytochemicals of the genus, there are reports of the ability to inhibit NALP3 inflammasome formation, which would prevent the excretion of IL-1β. Once excreted, it will exert its activity by binding to the extracellular IL-1 type I receptor (IL-1RI), which will lead to the recruitment of IL-1R accessory protein (IL-1RAcP) and other adapters, and thus activate the NFκB, JNK, ERK, or MPAK signaling pathways [43], and this graphical represented in Figure 2A.

Another case with fish was with Cyprinus carpio, where they were fed an extract of Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies at doses of 200 or 400 mg/kg for 8 weeks, which improved their growth and intestinal antioxidant status [45]. This is due to an increase in the mRNA levels of GPx, CAT, SOD, and Nrf2, in addition to a reduction in the levels of IL-1β and IL-6. GPx, CAT, and SOD are known as front-line antioxidant defense systems. This is because ROS molecules are the most abundant oxidizing molecules within cells, especially molecules such as superoxide anions. Moreover, SOD can transform these superoxide anion molecules into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and O2, so that subsequently CAT or GPx catalyzes the reduction of H2O2 to water, thus eliminating the oxidative danger of these molecules [46]. It should be noted that the increase in these antioxidant enzymes is one of the most reported effects within the phytochemicals reported in Section 5, as many managed to increase the concentration of these 3 enzymes (Figure 1B).

As it can be seen through Section 5 that the reported effect of Yucca extracts, the main pathways involved in its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect are the inhibition of MAPK, and NF-κB, and the activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway.

4.1. Inhibition of NF-κB Signaling Pathway

The NF-κB is a family of transcription factors that coordinate one of the most common proinflammatory signaling pathways. Within the phytochemicals in Section 5, there is constant mention of the inhibition of this pathway (Figure 2A). The family of NF-κB has 5 members: RelA, c-Rel, RelB, p50, and p52. RelA, RelB, and c-Rel share a transactivation domain that makes them capable of promoting transcriptional activation, while p50 and p52 act as coactivators [47]. There are 2 variations of this pathway, the canonical one where RelA and p50 are responsible for promoting the transcription of target genes, and in the non-canonical RelB and p52 [48].

The canonical NF-kB pathway is primarily a response to proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1, and it has an important role in chronic inflammatory diseases [49]. The pathway begins with the activation of receptors, such as TNFR and IL-1RI, which will generate a series of steps resulting in the activation of IKKβ [48]. The IKKβ will phosphorylation IκBα, which results in the release of the sequestered RelA-p50 dimers. Once these dimers translocate to the nucleus, they activate the transcription of receptors and proinflammatory cytokines involved in the inflammatory response [48]. As mentioned above, the inhibition of IKK activation and phosphorylation IκBα are an abundant effect between phytochemicals described in Section 5.

The non-canonical NF-kB pathway begins with the activation of the TNFR superfamily members, or the formation of an endosome complex containing NIK, AKT, and MAC, to stabilize and accumulate NIK. The NIK (NF-kB inducing kinase) with IKKα will induce the phosphorylation of the precursor of p52, resulting in the formation of RelB/p52 dimer [49].

4.2. Inhibition of the MAPK Signaling Pathway

The MAPK superfamily is one of the major mechanisms used in signaling pathways and is characterized by its activation through the dual phosphorylation on adjacent threonine and tyrosine residues [50]. In inflammation, the activation of receptors triggers the MAPK pathways, and transcription factors are phosphorylated and activated, such as NF-κB [51]. There are 3 well-known MAPK pathways, the ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAP kinase, all of which activate proinflammatory stimuli [52]. ERK1/2 signaling begins with the binding of a ligand to the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK); this activates G-protein kwon as Ras. Ras directly binds to Raf and activates it, then Raf activates MEK, and MEK phosphorylates ERK1/2 so it can enter the nucleus and activate transcription factors [53]. As can be seen in Section 5, there are molecules within the Yucca genus that have shown the capacity to suppress this signaling pathway.

The p38 MAPK pathway begins the activation of receptors, such as toll-like receptors, TNFR, or the IL1R superfamily, to inflammatory stimuli. This activation generates the phosphorylation of TRAF 2/3/6 (TNF receptor-associated factor), which in turn activates MAP3Ks, such as TAK1. Then, MAP3K phosphorylates MKK3 or MKK6, and those molecules activate p38 [54]. Many of the pro-inflammatory responses, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and COX-2, are positively regulated by p38 [51]. This pathway can regulate the NF-κB-dependent gene expression because p38 partially modulates the activation of basal transcription factors that interact with NF-κB [51]. Phytochemicals within the Yucca genus can reduce p38 phosphorylation and inhibit the signaling pathway.

There are 3 types of JNK proteins JNK1 (encoded by MAPK8), JNK2 (encoded by MAPK9), and JNK3 (encoded by MAPK10), where JNK1 and JNK2 are found in almost all cells [55]. This signaling pathway, as the other two can be triggered by proinflammatory cytokines. The activation of JNK begins with the phosphorylation of MAP3Ks, which subsequently phosphorylates MKK7 or MKK4, and then phosphorylates the JNK kinases [56]. JNK regulates the activity and maturation of T cells, as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, and therefore this pathway is related to chronic inflammatory disorders [57]. Within the genus, there are molecules that decrease the activation of this pathway (Figure 2B).

4.3. Activation of the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway

Nrf2 is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory proteins, and it is considered a modulator of species longevity [58]. Its anti-inflammatory effect is due to an indirect control of NF-kB activity and a direct control of IL-6 and IL-1β expression [59]. In fact, under normal inflammatory conditions, Nrf2 expression is activated by NF-kB to initiate a slow response that can stop the NF-kB inflammatory response [60]. Nrf2 is considered the major regulator against oxidative stress, as it regulates the expression of antioxidant response element genes, such as SOD, GPx, NADP(H) quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1), and heme oxygenase (HO-1) [61]. It also regulates Phase II of xenobiotic metabolism, where it transforms carcinogenic intermediates, generated by Phase I of xenobiotic metabolism, into less toxic metabolites [62].

Nrf2 is regulated by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) and the Cullin 3 (Cul3) ubiquitin E3 ligase complex. Keap1 sequester Nrf2 and functions as an adaptor, so the Cul3 complex ubiquitinates Nrf2 to facilitate its proteasomal degradation [63]. Nrf2 can be activated by oxidative molecules modifying the cysteine residues of Keap1, stabilizing Nrf2-Keap1 interaction, and preventing Nrf2 ubiquitination [61,64]. Therefore, new Nrf2 could be synthetized without Kaep1 being able to sequester it. Nrf2 binds to Keap1 through a high-affinity ETGE motif, so proteins with this motif can interact with Keap1 and prevent Nrf2 sequestering [64]. Once Nrf2 is free, it translocates to the nucleus, and heterodimerizes with small Maf or Jun proteins to upregulate or inhibit target genes [61]. The activation of this pathway is one of the most reported effects throughout this genus of phytochemicals, by increasing the concentration of Nrf2 or inhibiting Keap1 (Figure 1B).

One gene regulated by Nrf2 is HO-1 (Heme oxygenase 1). The main function of HO-1 is to catalyze Haem (an iron-containing porphyrin) degradation; it uses cytochrome P450 reductase to transform Haem, NADPH, and O2 to biliverdin, carbon monoxide, ferrous iron (Fe2+), NADP+, and H2O [65]. However, it has also been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties. They have been shown to help chronic inflammation, along with Nrf2, to inhibit the adhesion of inflammatory cells by downregulating the expression of cell adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) [60]. This could explain the ability of some reported phytochemicals to decrease the expression of VCAM1.

4.4. Free Radical Scavenging Activity

Finally, there are relatively abundant reports in the literature on extracts from the Yucca genus with free radical scavenging activity in vitro. Yucca aloifolia L. leaf extracts with MeOH, CHCl3, EtOAc, nBuOH, and n-hexane solvent were tested for their radical scavenging activity [66]. Were Yucca aloifolia L. MeOH showed the highest potential by having an activity versus control of 74% in the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay and an inhibition of 64% in the linoleic acid peroxidation assay. Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies radical scavenging activity was tested with TEAC (Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity) assay and had trolox equivalents (TE) values of 1.78 [67,68] and 5.78 mM [69], respectively. Yucca baccata Torr. butanolic extract showed a 29.18 (μg TE/mg) in DPPH assay, 121.8 (μg TE/mg) in TEAC assay, 33.41 (μg TE/mg) in ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, and 156.84 in oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay [70]. These reports are consistent with the radical scavenging activity observed in phytochemicals observed in Section 5 (Figure 1B).

5. Phytochemistry

For thousands of years, mankind has used plants to treat various ailments. This knowledge has been passed down through hundreds of generations and remains the main form of health care for more than 4 billion people today [71]. Phytochemicals naturally protect the plant from environmental hazards, pathogenic attacks, or grant characteristics, such as its aroma and flavor. Due to these functions’, plants have the capability to produce a wide range of molecules, where factors such as soil pH, light, temperature, or stress will change its chemical composition [71]. Many of these molecules will have similar proprieties, especially those that are closely related.

Due to that, in recent years, there has been a trend in countries such as China where plants are being used to generate new drugs. Some phytochemicals are able to modulate inflammation and oxidative stress at the same time, since these two physiological phenomena often share the same pathways and intensify each other. An example of this is that ROS can act as an inflammatory signaling molecule, and in turn, inflammation can induce oxidative stress and reduce cellular antioxidant capacity [72].

Out of the documentary research, 365 molecules were found in the literature, of which 92 had antioxidant or anti-inflammatory reported activity. Of these molecules, 51 can be classified as Phenolic Compounds, 13 as Glycosides, 7 as Saponins, 9 as Fatty acids, 5 as Terpenes, 3 as Tocopherol, 2 as Dicarboxylic acid, 1 as Phytosterol, and Xanthones. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities reported in the literature of the phytochemicals found in the Yucca genus can be seen through Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3, Section 5.4 and Section 5.5

5.1. Phenolic Compounds

Phenolic compounds are phytochemicals that are characterized as containing an aromatic ring bonded to some hydroxyl groups in their structure. Plants can produce a wide variety of phenolic compounds [73]. These compounds play an important role in defense mechanisms against pathogens and stress conditions, such as drought, salinity, and UV [74]. This role is due, in part, to the structural capacity to capture free radicals and chelate metals, which protect the plant from oxidizing molecules [73]. These molecules maintain this antioxidant capacity when consumed, but as can be seen in Table 1, this is not the only reason behind their antioxidant or anti-inflammatory properties. Many of these molecules can downregulate inflammatory pathways, such as NF-kB, and upregulate antioxidant pathways, such as Nrf-2. A behavior that has been described similarly to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, the most commonly used drugs against inflammation [75].

Table 1.

Some of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of the phenolic compounds of the Yucca genus reported in the literature.

Within the Yucca genus, there is great diversity and concentration of phenolic compounds. Specifically, unique phenolic derivatives with potent antioxidant activity have been found in Yucca gloriosa L. (gloriosaols) and Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies (yuccaols) [34,69]. Among these unique molecules of the genus, Yuccaol C stands out because it prevents NF-kB activation and inhibits iNOS expression and NO release in a dose-dependent manner [34].

5.2. Saponins

Saponins are amphiphilic compounds that have a saccharide chain attached to a steroid or triterpenoid [157]. These compounds are involved in plant development and protection, where they are synthesized in response to pathogens, insects, or herbivores [158]. They are found in legume seeds in the human diet, and various positive effects on health are attributed to them [157]. In fact, since 1950, these molecules have been used to produce steroidal hormones and drugs [159]. As can be seen in Table 2, saponins have the capacity to decrease the levels of proinflammatory cytokines, especially steroidal saponins, due to their similarity to steroid hormones. This similarity allows some saponins to act as agonists to the glucocorticoid receptor, which generates glucocorticoid-like effects [160]. These types of molecules are found in a high content within the Yucca genus and are widely used in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries [161]. As with the phenolic compounds, in Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies, new saponins have been found: Yucca spirostanosides [162].

Table 2.

Some of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of saponins of the Yucca genus reported in the literature.

5.3. Glycosides

Glycosides are a large structurally diverse group of phytochemicals; they have 2 units a small metabolite (aglycone) and a sugar (glycone) [176]. When plants add sugar to small metabolites, it improves their biodistribution, metabolism, and storage [177]. Most of its biological activities come from the “small metabolite”, but the addition of sugar will change the magnitude of the activity. An example of this is that rutin (Quercetin 3-rutinoside) has higher anti-inflammatory activity than its aglycone part, quercetin [178]. This difference may be due to its absorption and metabolism, where glycosides are mostly absorbed in the small intestine after deglycosylation, which allows the metabolite to enter the liver and then be excreted to the blood [179]. As can be seen in Table 3, its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity is well known.

Table 3.

Some of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Glycosides of the Yucca genus reported in the literature.

5.4. Fatty Acids

Fatty acids are lipid structures composed of a long carbon chain with a carboxyl group at one end and a methyl group at the other end [201]. If this structure has a double bond, it is classified as “Unsaturated fatty acids”. Plants mainly produce unsaturated fatty acids. These can be synthesized by plants as part of the various defense systems against biotic and abiotic stresses [202]. Fatty acids also function as modulators of cell membranes, as energy reserves, as extracellular barriers, and as precursors of signaling molecules [203]. As can be seen in Table 4, their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties are well known. This effect depends on the position of the first double bond within the carbon chain. If it occurs in the sixth (n-6), it will be considered pro-inflammatory because it is a precursor of arachidonic acid [25]. If it occurs in the third (n-3), it will be considered anti-inflammatory because it will compete as a substrate for n-6 metabolism [25]. On the other hand, these structures are susceptible to oxidize, and for the same reason, they work as antioxidants. Within the Yucca genus, it has been reported that Yucca aloifolia variegate L. contains more saturated fatty acids than unsaturated, constituted mainly by palmitic acid and palmitoleic acid [87].

Table 4.

Some of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of fatty acids of the Yucca genus reported in the literature.

5.5. Other Phytochemicals

Among the phytochemicals that were found at a lower frequency, the terpenes stand out with the anti-inflammatory effect. Terpenes are the most abundant and diverse class of phytochemicals; structurally, they are made up of isoprene molecules (Table 5). They have a wide range of functions, from primarily being part of plant structures to being quinones in electron transfer [215]. On the other hand, tocopherols stand out for their antioxidant activity. These molecules are exclusively synthesized in photosynthetic organisms and consist of a chromanol head group with one, two, or three methyl groups, and an isoprenoid [216]. α-Tocopherol is the major vitamin E component and one of the most important antioxidant regulatory mechanisms [217].

Table 5.

Some of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of other phytochemicals of the Yucca genus reported in the literature.

5.6. Availability of Reported Phytochemicals

It is worth noting that the presence by itself of phytochemicals does not guarantee that it will generate the desired biological effect. As with drugs, the quantity of the phytochemical dictates its efficacy. There are many factors that could alter the quantity of phytochemicals. Phytochemicals are mostly generated in response to external stimuli [71]. Thus, all external stimuli alter the synthesis of phytochemicals. In the same way, there will be differences depending on the tissue. In addition, plant tissue may undergo postharvest changes [244]. Then, the extraction of phytochemicals will alter the availability. Here, factors such as the solvent, temperature, time, and pH, among others, will influence the type and amount of phytochemicals obtained [245]. In general, there are a small number of reports assessing the quantity of Yucca phytochemicals in the literature. The same is true regarding the difference between extraction and improvement in phytochemical concentration. Within the reports included here, the great variability caused by the factors previously described is notorious. This can be seen in Table 6. Specifically, the difference can be seen when comparing the quantity of resveratrol, 3,3’,5,5’-tetrahydroxy-4-methoxystilbene, Yuccaol A, and Yuccaol C obtained between both extraction methods. Despite the differences in concentrations and types of phytochemicals, the presence of multiple phytochemicals with similar biological effects would suggest a robustness that would allow for the prevalence of their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity.

Table 6.

Quantity of reported phytochemicals in the Yucca genus.

Finally, another important factor related to the availability of phytochemicals is microbiota. The gut microbiota metabolizes most molecules consumed, including drugs or phytochemicals. In the intestine, phytochemicals are degraded by microbes and absorbed by tissues [246]. Some phytochemicals need to be metabolized by the gut microbiota in order to generate its biological effect [247]. Poorly absorptive phytochemicals can undergo structural modifications that improve their bioavailability [246,247]. This especially applies to glycosides, as mentioned above. Glycosides have low bioavailability and bioactivity until their aglycone is deglycosylated by gut microbiota [246,247]. This modification through gut microbiota has been reported to have a role in some antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. This is especially true through Nrf2, as the genus Lactobacillus capable of stimulating its activation through small molecules [248]. One example of this is the biotransformation of caffeic acid, a phytochemical that can be found in the Yucca, into 4-vinyl-catechol. This is an activator of Nrf2 [249]. It has also been reported that treatment with pre-fermented Angelica sinensis activates Nrf2 signaling better than treatment with non-fermented Angelica sinensis in mice [250]. It also increases the level of bacteria related to Nrf2 signaling, such as Lactobacillus. Thus, the fermentation of phytochemicals through bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, is key for the efficient activation of Nfr2. From the abundance of reports on Yucca phytochemicals activating Nrf2, it could be assumed that other phytochemicals follow the pathway of phytochemicals and are metabolized by bacteria into Nrf2 activators.

6. Future Perspectives

Although there is research on the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of the Yucca genus, there are still many unknowns to be resolved. First, most of the research related to the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties has only focused on Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies and Yucca gloriosa L. [22,23,27,42]. It is worth noting that, within these 2 species, phytochemicals endemic to the genus have been found. Some of these have shown a particular effect against inflammation and oxidative stress [31]. Therefore, it could be expected to find other phytochemicals with similar structures among the other species. It has been reported that metabolomics can be used in taxonomical classifications [251]. If there are molecules that have a similar structure, it is very possible that they have a quite similar effect. This is based on the similarity principle, where similar molecules exhibit similar biological activity [252]. Thus, within the 50 species, there could be molecules with greater anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential. Thus, there are unexplored unknowns related to most Yucca species. More specifically, to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and phytochemicals.

However, even with the favorable results of the research done with Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies and Yucca gloriosa L., further study of its use against inflammatory diseases is still needed. In particular, in vitro studies rarely cope with the complexity of human diseases [253]. From what could be found in the literature, only a few disease models have been used to study the therapeutic potential of Yucca, such as ovalbumin-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice [27]. Similarly, the efficacy and potency of different Yucca extracts have not been compared. Nor has its effect been compared with that of known treatments. Therefore, the study of Yucca genus against established models of inflammatory diseases is another field without much exploration. Finally, since the discovery of Yuccaol C and its mechanism of action against NO synthesis [31]. There has not been much research done on this topic. This is surprising since it is found in relatively large proportions within Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies and Yucca gloriosa L., as can be seen in Table 1. In addition to its reported efficiency, against the NF-kB pathway [31]. Thus, there is another unexplored Yucca topic. For the same reason, although there is favorable evidence on the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacity of Yucca genus. There is still a lot of research to be done before being able to describe the genus or its phytochemicals as an alternative to treat inflammatory diseases.

7. Conclusions

Yucca genus encompasses about 40 to 50 species, natives of southern North America. For centuries, it has been used to treat pathologies such as asthma, rheumatism, gonorrhea, sunburns, arthritis, etc. The ethnobotanical use led to the testing of many biological activities, where its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory excels. Unfortunately, there are a limited number of studies, so knowing its composition will provide a better understanding of the molecules responsible for these properties. This is because it is known that the medicinal use of plants is due to its phytochemicals. The documentary research found 92 phytochemicals with reported antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Most of these molecules can be classified as phenolic compounds, glycosides, saponins, or fatty acids. Within these molecules, phytochemicals, such as Yuccaol C, stand out because they are original to the genus and have significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties are mainly generated through free radical scavenging activity, the inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolism, the inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB, and the activation of Nrf2 signaling pathway. The NF-kB pathway is mainly inhibited by phytochemicals through the inhibition of IKK activation and phosphorylation IκBα, and the decrease of NF-kB concentration. The MAPK pathways are mainly inhibited by reducing p38, JNK, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Nrf2 is activated by increasing its concentration or inhibiting Keap1. However, there is evidence of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of some species within the genus, and although it is not abundant, the fact that a great variety of the phytochemicals that compose it present the same activities allows us to assess these properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.C. and A.Z.M.S.; A.M. and M.M.M.Y.E.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.C., M.M.M.Y.E. and A.Z.M.S.; A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.Z.M.S., A.M. and P.D.P.; visualization, A.Z.M.S.; supervision, M.M.M.Y.E. and A.Z.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is contained and referenced within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1β |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| MDA | Malonaldehyde |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| 8-oxo-dG | 8-Oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| TEAC | Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity |

| NLRP3 | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing domain 3 of pyrin |

| PDE4 | Phosphodiesterase 4 |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| LPO | Lipid Peroxidation |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| IκBα | Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MIP-2 | Macrophage inflammatory protein 2 |

| IKK | IkB kinase |

| JNK | c-Jun amino terminal kinase |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| GST | Glutathione-S-transferase |

| CRP | Reactive C-protein |

| PAR-1 | Protease-activated receptor 1 |

| TXB2 | Thromboxane B2 |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| COX-1 | Cyclooxygenase-1 |

| VCAM1 | Vascular cell adhesion protein 1 |

| VWF | von Willebrand factor |

| GPIbα | platelet adhesion receptor glycoprotein |

| AA | arachidonic acid |

| TxA2 | Thromboxane A2 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin-13 |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| PEs | Phosphatidylethanolamines |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| IL-1RI | IL-1 type I receptor |

| IL-1RAcP | IL-1R accessory protein |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| NIK | NF-kB inducing kinase |

| TRAF | TNF receptor-associated factor |

| RTK | Receptor tyrosine kinase |

| Cul3 | Cullin 3 |

| NQO1 | NADP(H) quinone oxidoreductase |

| ORAC | Oxygen radical absorbance capacity |

| DPPH | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

References

- Karamova, N.; Gumerova, S.; Hassan, G.O.; Abdul-Hafeez, E.Y.; Ibrahim, O.H.M.; Orabi, M.A.A.; Ilinskaya, O. Antioxidant and Antimutagenic Potential of Extracts of Some Agavaceae Family Plants. Bionanoscience 2016, 6, 591–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. Yucca: A medicinally significant genus with manifold therapeutic attributes. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2012, 2, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kaur, D.; Sethi, A.; Chandrahas; Saini, A.; Chandra, M. Effect of Dietary Supplementation of Yucca schidigera Extract on the Performance and Litter Quality of Broilers in Winter Season. Anim. Nutr. Feed. Technol. 2016, 16, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, R.S.; Ortiz, B.L.S.; Pereira, A.C.M.; Keita, H.; Carvalho, J.C.T. Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil: A review of its phytochemistry, anti-inflammatory activity, and mechanisms of action involved. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 229, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory Responses and Inflamma-tion-Associated Diseases in Organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.I.C.; Elghandour, M.M.M.Y.; Khusro, A.; Alcala-Canto, Y.; Tirado-González, D.N.; Barbabosa-Pliego, A.; Salem, A.Z.M. Dietary Supplements of Vitamins E, C, and β-Carotene to Reduce Oxidative Stress in Horses: An Overview. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2022, 110, 103863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, T.; Kim, D.H.; Lim, B.O. Natural Products as a Source of Anti-Inflammatory Agents Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Molecules 2013, 18, 7253–7270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ramírez, Y.; Palomeque-Carlín, A.; Chávez Ortiz, L.I.; de la Rosa-Carrillo, M.D.L.; Pérez-Molphe-Balch, E. Micropropagation of Yucca Species. Plant Cell Cult. Protoc. 2018, 1815, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Pellmyr, O. Yuccas, Yucca Moths, and Coevolution: A Review. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2003, 90, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguiarte, L.E.; Leebens-Mack, J.; Heyduk, K. Editorial: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives for Agavoideae Research: Agave, Yucca and Related Taxa. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 687596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Plant List. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/ (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Anderson, M.K.; Keeley, J.E. Native Peoples’ Relationship to the California Chaparral. In Valuing Chaparral; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 79–121. [Google Scholar]

- Corrales, V.M.S. Léxico Relativo al Ámbito Del Tamal En Costa Rica. Káñina Rev. Artes Letras 2006, 30, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier, G.R. Ethnobotany of the Northern Cheyenne: Medicinal Plants. Masters Thesis, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, T.K.; Lim, T.K. Yucca Filamentosa. Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants. Flowers 2014, 7, 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Duraiswamy, B.; Muthureddy Nataraj, S.K.; Rama Satyanarayana Raju, K.; Babu, U.V. Inhibitory Potential of Yucca Gloriosa, L. Extract and Isolated Gloriosaol Isomeric Mixture on Ovalbumin Induced Airway Hyperresponsiveness in Balb/C Mice. Clin. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, R.; Bellew, B.A.; Bellew, J.G. Yucca Plant Saponin in the Management of Arthritis. J. Appl. Nutr. 1975, 17, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-W.; Park, S.-K.; Kang, S.; Kang, H.-C.; Oh, H.-J.; Bae, C.-Y.; Bae, D.-H. Hypocholesterolemic Property OfYucca Schidigera AndQuillaja Saponaria Extracts in Human Body. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2003, 26, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-García, G.J.; Quintana-Romero, L.A.; Morales-Figueroa, G.G.; Esparza-Romero, J.; Pérez-Morales, R.; López-Mata, M.A.; Juárez, J.; Sánchez-Escalante, J.J.; Peralta, E.; Quihui-Cota, L. Effect of Yucca Baccata Butanolic Extract on the Shelf Life of Chicken and Development of an Antimicrobial Packaging for Beef. Food Control. 2021, 127, 108142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Trujillo, R.C.L. Characterization and Evaluation of yucca baccata saponins against giardia intestinalis trophozoites in vitro. Doctoral Thesis, Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, Mazatlán Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mokbli, S.; Nehdi, I.A.; Sbihi, H.M.; Tan, C.P.; Al-Resayes, S.I.; Rashid, U. Yucca Aloifolia Seed Oil: A New Source of Bioactive Compounds. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.R.; Storey, R.F. The Role of Platelets in Inflammation. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 114, 449–458. [Google Scholar]

- Olas, B.; Wachowicz, B.; Stochmal, A.; Oleszek, W. Inhibition of Blood Platelet Adhesion and Secretion by Different Phenolics from Yucca Schidigera Roezl. Bark. Nutrition 2005, 21, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, B.; Marks, D.C.; van der Wal, D.E. Not All (N) SAID and Done: Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Paracetamol Intake on Platelets. Res. Pr. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion-Letellier, R.; Savoye, G.; Ghosh, S. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Inflammation. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzig, E.M.; Oleszek, W.; Stochmal, A.; Kunert, O.; Bauer, R. Influence of Phenolic Constituents from Yucca Schidigera Bark on Arachidonate Metabolism in Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 8885–8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casaro, M.; Souza, V.R.; Oliveira, F.A.; Ferreira, C.M. OVA-Induced Allergic Airway Inflammation Mouse Model. In Pre-Clinical Models: Techniques and Protocols; Guest, P.C., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1916, pp. 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Verpoorte, R.; Korthout, H.A.A.J.; Mustafa, N.R. Phytochemicals as a Potential Source for TNF-α Inhibitors. Phytochem. Rev. 2013, 12, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israël, A. The IKK Complex: An Integrator of All Signals That Activate NF-ΚB? Trends Cell. Biol. 2000, 10, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.E.; O’Keefe, R.A.; Grandis, J.R. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 Signalling Axis in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, R.; Lahti, A.; Kankaanranta, H.; Moilanen, E. Nitric Oxide Production and Signaling in Inflammation. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 2005, 4, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautz, A.; Art, J.; Hahn, S.; Nowag, S.; Voss, C.; Kleinert, H. Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide 2010, 23, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, L.; Lorin, J.; Zeller, M.; Guilland, J.-C.; Lorgis, L.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Nitric Oxide Synthase Inhibition and Oxi-dative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: Possible Therapeutic Targets? Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 140, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzocco, S.; Piacente, S.; Pizza, C.; Oleszek, W.; Stochmal, A.; Pinto, A.; Sorrentino, R.; Autore, G. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by yuccaol C from Yucca schidigera roezl. Life Sci. 2004, 75, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.L.; Davies, M.J. Role of Myeloperoxidase and Oxidant Formation in the Extracellular Environment in Inflamma-tion-Induced Tissue Damage. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 172, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, E.; Furtmüller, P.G.; Sattler, W.; Obinger, C. Myeloperoxidase: A Target for New Drug Development? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 152, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, Y.; Kiyokawa, H.; Kimura, Y.; Kato, Y.; Tsuchiya, K.; Terao, J. Hypochlorous Acid-Derived Modification of Phospho-lipids: Characterization of Aminophospholipids as Regulatory Molecules for Lipid Peroxidation. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 14201–14211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondial-dehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Z.; Karthigesu, I.P.; Singh, P.; Rupinder, K. Use of Malondialdehyde as a Biomarker for Assessing Oxidative Stress in Different Disease Pathologies: A Review. Iran J. Public Health 2014, 43, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marnett, L.J. Oxy radicals, lipid peroxidation and DNA damage. Toxicology 2002, 181, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigerci, H.; Fidan, A.F.; Konuk, M.; Yuksel, H.; Kucukkurt, I.; Eryavuz, A.; Sozbilir, N.B. The protective potential of Yucca schidigera (Sarsaponin 30®) against nitrite-induced oxidative stress in rats. J. Nat. Med. 2009, 63, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, R.; Dai, Z.; Wang, C.; Wu, Z. Dietary supplementation with Yucca schidigera extract alleviated heat stress-induced unfolded protein response and oxidative stress in the intestine of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 219, 112299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, C.; Lamacchia, C.; Palmer, G. IL-1 pathways in inflammation and human diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Wasiliew, P.; Kracht, M. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) Processing Pathway. Sci. Signal 2010, 3, cm2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, D.; Fan, Z.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wang, G.; Zhu, Z. Effect of Yucca schidigera extract on the growth performance, intestinal antioxidant status, immune response, and tight junctions of mirror carp (Cyprinus carpio). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2020, 103, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culhuac, E.B.; Elghandour, M.M.M.Y.; Adegbeye, M.J.; Barbabosa-Pliego, A.; Salem, A.Z.M. Influence of Dietary Selenium on the Oxidative Stress in Horses. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2022, 201, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smale, S.T. Dimer-specific Regulatory Mechanisms within the NF-κB Family of Transcription Factors. Immunol. Rev. 2012, 246, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. Targeting NF-ΚB Pathway for the Therapy of Diseases: Mechanism and Clinical Study. Signal Transduct. Target 2020, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, T. The Nuclear Factor NF-ΚB Pathway in Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a001651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbabi, S.; Maier, R. v Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, S74–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, B. MAPK signalling pathways as molecular targets for anti-inflammatory therapy—from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic benefits. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1754, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Silva, M.; Diniz, F.F.; Gomes, G.N.; Bahia, D. The Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway: Role in Immune Evasion by Trypanosomatids. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Liu, M.; Ji, B.; Bai, B.; Cheng, B.; Wang, C. Role of the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 Signaling Pathway in Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamer, E.; Corrêa, S.A.L. The P38MAPK-MK2 Signaling Axis as a Critical Link Between Inflammation and Synaptic Trans-mission. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 635636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.F.; Nebreda, Á.R. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.G.; Aziz, N.; Cho, J.Y. MKK7, the essential regulator of JNK signaling involved in cancer cell survival: A newly emerging anticancer therapeutic target. Ther. Adv. Med Oncol. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.K.; Rashid, F.; Bragg, J.; A Ibdah, J. Role of the JNK signal transduction pathway in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loboda, A.; Damulewicz, M.; Pyza, E.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: An evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3221–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.P.; Pellmyr, O.; Raguso, R.A. Strong Conservation of Floral Scent Composition in Two Allopatric Yuccas. J. Chem. Ecol. 2006, 32, 2657–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, A.; Manda, G.; Hassan, A.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Barbas, C.; Daiber, A.; Ghezzi, P.; León, R.; López, M.G.; Oliva, B.; et al. Transcription Factor NRF2 as a Therapeutic Target for Chronic Diseases: A Systems Medicine Approach. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018, 70, 348–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Ci, X. Role of Nrf2 and Its Activators in Respiratory Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7090534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Su, Z.; Kong, A.-N.T. The Complexity of the Nrf2 Pathway: Beyond the Antioxidant Response. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1401–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Irfan, H.M.; Jahan, S.; Shahzad, M.; Latif, M.B. Nerolidol: A Potential Approach in Rheumatoid Arthritis through Reduction of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, NF-KB, COX-2 and Antioxidant Effect in CFA-Induced Arthritic Model. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Islas, C.A.; Maldonado, P.D. Canonical and Non-Canonical Mechanisms of Nrf2 Activation. Pharm. Res. 2018, 134, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.K.; Fitzgerald, H.K.; Dunne, A. Regulation of Inflammation by the Antioxidant Haem Oxygenase. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, Z.; Nasir, R.; Asim, M.; Fozia, A.; Munawar, I.; Muhammad, M.; Muhammad, S. Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Antifungal Activities and Phytochemical Analysis of Dagger (Yucca Aloifolia) Leaves Extracts. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Piacente, S.; Pizza, C.; Oleszek, W. Saponins and Phenolics of Yucca Schidigera Roezl: Chemistry and Bioactivity. Phytochem. Rev. 2005, 4, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacente, S.; Montoro, P.; Oleszek, W.; Pizza, C. Yucca s Chidigera Bark: Phenolic Constituents and Antioxidant Activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassarello, C.; Bifulco, G.; Montoro, P.; Skhirtladze, A.; Benidze, M.; Kemertelidze, E.; Pizza, C.; Piacente, S. Yucca Gloriosa: A Source of Phenolic Derivatives with Strong Antioxidant Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 6636–6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Figueroa, G.-G.; Pereo-Vega, G.D.; Reyna-Murrieta, M.E.; Pérez-Morales, R.; López-Mata, M.A.; Sánchez-Escalante, J.J.; Tapia-Rodriguez, M.R.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Juárez, J.; Quihui-Cota, L. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties of Extracts of Yucca Baccata, a Plant of Northwestern Mexico, against Pathogenic Bacteria. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 9158836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, G.A. Phytochemistry and Traditional Medicine–A Revolution in Process. Phytochem. Lett. 2011, 4, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Sun, Y.; Tsao, R. Paradigm Shift in Phytochemicals Research: Evolution from Antioxidant Capacity to Anti-Inflammatory Effect and to Roles in Gut Health and Metabolic Syndrome. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 8551–8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, M.M.; Lima, V.S.; Junior, M.R.M. Phenolic Compounds: Structure, Classification, and Antioxidant Power. In Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Abedin, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Das, S. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Plant-Defensive Mechanisms. Plant Phenolics Sustain. Agric. 2020, 1, 517–532. [Google Scholar]

- Ambriz-Pérez, D.L.; Leyva-López, N.; Gutierrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Heredia, J.B. Phenolic Compounds: Natural Alternative in Inflammation Treatment. A Review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1131412. [Google Scholar]

- Ememe, M.U.; Mshelia, W.P.; Ayo, J.O. Ameliorative Effects of Resveratrol on Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2015, 35, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Avila, J.G.; de Vivar, A.R.; Garcı́a, A.M.; Marı́n, J.C.; Aranda, E.; Céspedes, C.L. Antioxidant and Insect Growth Regulatory Activities of Stilbenes and Extracts from Yucca Periculosa. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoro, P.; Skhirtladze, A.; Bassarello, C.; Perrone, A.; Kemertelidze, E.; Pizza, C.; Piacente, S. Determination of Phenolic Compounds in Yucca Gloriosa Bark and Root by LC–MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 47, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez-Trujillo, N.; Monribot-Villanueva, J.L.; Jiménez-Fernández, V.M.; Suárez-Montaño, R.; Aguilar-Colorado, Á.S.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Jiménez, M. Phytochemical Characterization of Izote (Yucca Elephantipes) Flowers. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2018, 91, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Yu, H.; Huang, S.; Zhu, P. Resveratrol Protects against TNF-α-Induced Injury in Human Umbilical Endothelial Cells through Promoting Sirtuin-1-Induced Repression of NF-KB and P38 MAPK. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zykova, T.A.; Zhu, F.; Zhai, X.; Ma, W.; Ermakova, S.P.; Lee, K.W.; Bode, A.M.; Dong, Z. Resveratrol Directly Targets COX-2 to Inhibit Carcinogenesis. Molecular Carcinogenesis: Published in cooperation with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center 2008, 47, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Dai, F.; Li, G.-H.; Chen, X.-M.; Li, Y.-R.; Wang, S.-Q.; Ren, D.-M.; Wang, X.-N.; Lou, H.-X.; Zhou, B. Trans-4, 4′-Dihydroxystilbene Ameliorates Cigarette Smoke-Induced Progression of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease via Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response. Free. Radic Biol. Med. 2020, 152, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.-J.; Liu, X.-D.; Qian, Y.-P.; Shang, Y.-J.; Li, X.-Z.; Dai, F.; Fang, J.-G.; Jin, X.-L.; Zhou, B. 4, 4′-Dihydroxy-Trans-Stilbene, a Resveratrol Analogue, Exhibited Enhanced Antioxidant Activity and Cytotoxicity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B.; Wachowicz, B.; Nowak, P.; Stochmal, A.; Oleszek, W.; Glowacki, R.; Bald, E. Comparative Studies of the Antioxidant Effects of a Naturally Occurring Resveratrol Analogue–Trans-3, 3′, 5, 5′-Tetrahydroxy-4′-Methoxystilbene and Resveratrol–against Oxidation and Nitration of Biomolecules in Blood Platelets. Cell. Biol. Toxicol. 2008, 24, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Luo, T.; Weng, A.; Huang, X.; Yao, Y.; Fu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, A.; Li, X.; Chen, D. Gallic Acid Alleviates Gouty Arthritis by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Pyroptosis through Enhancing Nrf2 Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 580593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, N.G.M.; El-Sherbeni, S.A.; El-Kadem, A.H.; Elekhnawy, E.; El-Masry, T.A.; Elmongy, E.I.; Altwaijry, N.; Negm, W.A. Elucidation of the Metabolite Profile of Yucca Gigantea and Assessment of Its Cytotoxic, Antimicrobial, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Molecules 2022, 27, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, A.M.; Basam, S.M.; Marzouk, H.S.; El-Hawary, S. LC–MS/MS and GC–MS Profiling as Well as the Antimicrobial Effect of Leaves of Selected Yucca Species Introduced to Egypt. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JIANG, D.; ZHANG, M.; ZHANG, Q.; CHEN, Y.; WU, W.; Xiang, M.U.; Wu, C. Influence of Gallic Acid on Porcine Neutrophils Phosphodiesterase 4, IL-6, TNF-α and Rat Arthritis Model. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lyu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhong, D.; Xu, Z.; He, F.; Huang, G. Chlorogenic Acid Inhibits BAFF Expression in Collagen-Induced Arthritis and Human Synoviocyte MH7A Cells by Modulating the Activation of the NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 8042097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Raouf, O.M.; El-Sayed, E.M.; Manie, M.F. Cinnamic Acid and Cinnamaldehyde Ameliorate Cisplatin-induced Splenotoxicity in Rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2015, 29, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikram, M.; Muhammad, T.; Rehman, S.U.; Khan, A.; Jo, M.G.; Ali, T.; Kim, M.O. Hesperetin Confers Neuroprotection by Regulating Nrf2/TLR4/NF-ΚB Signaling in an Aβ Mouse Model. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 6293–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.H.; Kim, M.E.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.-D.; Lee, J.S. Hesperetin Inhibits Neuroinflammation on Microglia by Suppressing Inflammatory Cytokines and MAPK Pathways. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2019, 42, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, A.; Azizi, S. Effects of Naringenin on Experimentally Induced Rheumatoid Arthritis in Wistar Rats. Arch. Razi. Inst. 2021, 76, 903. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.Y.; Kim, G.-Y.; Choi, Y.H. Naringenin Attenuates the Release of Pro-Inflammatory Mediators from Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated BV2 Microglia by Inactivating Nuclear Factor-ΚB and Inhibiting Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Tsilioni, I.; Taliou, A.; Francis, K.; Theoharides, T.C. Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, Who Improved with a Luteolin-Containing Dietary Formulation, Show Reduced Serum Levels of TNF and IL. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5, e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyagbemi, A.A.; Omobowale, T.O.; Ola-Davies, O.E.; Asenuga, E.R.; Ajibade, T.O.; Adejumobi, O.A.; Afolabi, J.M.; Ogunpolu, B.S.; Falayi, O.O.; Saba, A.B. Luteolin-mediated Kim-1/NF-kB/Nrf2 Signaling Pathways Protects Sodium Fluoride-induced Hypertension and Cardiovascular Complications. Biofactors 2018, 44, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciello, F.; di Pino, A.; Rolesi, R.; Troiani, D.; Paludetti, G.; Grassi, C.; Fetoni, A.R. Anti-Oxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Caffeic Acid: In Vivo Evidences in a Model of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 143, 111555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, İ. Antioxidant Activity of Caffeic Acid (3, 4-Dihydroxycinnamic Acid). Toxicology 2006, 217, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.-C.; Zhang, H.-B.; Gu, C.-D.; Guo, S.-D.; Li, G.; Lian, R.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, G.-Q. Protective Effect of Acacetin on Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury via Its Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Activity. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018, 41, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Wu, K.; Wang, M.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Deng, R. Antioxidant Activities and Chemical Constituents of Flavonoids from the Flower of Paeonia Ostii. Molecules 2016, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Y.; Toledo, R.T. Major Flavonoids in Grape Seeds and Skins: Antioxidant Capacity of Catechin, Epicatechin, and Gallic. Acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Chen, S. Antioxidant Activity and Mechanism of Protocatechuic Acid in Vitro. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2011, 1, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lende, A.B.; Kshirsagar, A.D.; Deshpande, A.D.; Muley, M.M.; Patil, R.R.; Bafna, P.A.; Naik, S.R. Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Activity of Protocatechuic Acid in Rats and Mice. Inflammopharmacology 2011, 19, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabelo, T.K.; Guimaraes, A.G.; Oliveira, M.A.; Gasparotto, J.; Serafini, M.R.; de Souza Araújo, A.A.; Quintans-Junior, L.J.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Gelain, D.P. Shikimic Acid Inhibits LPS-Induced Cellular pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Attenuates Mechanical Hyperalgesia in Mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 39, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ramírez, Y.; Cabañas-García, E.; Areche, C.; Trejo-Tapia, G.; Pérez-Molphe-Balch, E.; Gómez-Aguirre, Y.A. Callus Induction and Phytochemical Profiling of Yucca Carnerosana (Trel.) McKelvey Obtained from in Vitro Cultures. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quim. 2021, 20, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokdad-Bzeouich, I.; Mustapha, N.; Sassi, A.; Bedoui, A.; Ghoul, M.; Ghedira, K.; Chekir-Ghedira, L. Investigation of Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Eriodictyol through Its Cellular Anti-Oxidant Activity. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Guo, H.; Huang, Y.A.N.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X. Eriodictyol, a Plant Flavonoid, Attenuates LPS induced Acute Lung Injury through Its Antioxidative and Anti inflammatory Activity. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 2259–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Chen, C.; Hsu, C.; Chen, C.; Tsai, Y. Antioxidant Properties of Scopoletin Isolated from Sinomonium Acutum. Phytother. Res. 2003, 17, 823–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Dai, Y.; Hao, H.; Pan, R.; Yao, X.; Wang, Z. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Scopoletin and Underlying Mechanisms. Pharm. Biol. 2008, 46, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, R.; Lucena, C.; Macho, A.; Calzado, M.A.; Blanco-Molina, M.; Minassi, A.; Appendino, G.; Muñoz, E. Immunosuppressive Activity of Capsaicinoids: Capsiate Derived from Sweet Peppers Inhibits NF-κB Activation and Is a Potent Antiinflammatory Compound in Vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002, 32, 1753–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Kang, K.A.; Zhang, R.; Piao, M.J.; Jo, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kang, S.S.; Lee, J.S.; Park, D.H.; Hyun, J.W. Myricetin Suppresses Oxidative Stress-Induced Cell Damage via Both Direct and Indirect Antioxidant Action. Env. Toxicol. Pharm. 2010, 29, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Hu, S.; Su, Z.; Wang, Q.; Meng, G.; Guo, T.; Zhang, J.; Gao, P. Myricetin Attenuates LPS-Induced Inflammation in RAW 264.7 Macrophages and Mouse Models. Future Med. Chem. 2018, 10, 2253–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.H.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, J.H. Antioxidant and Apoptosis-Inducing Activities of Ellagic Acid. Anticancer. Res. 2006, 26, 3601–3606. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, P.; Hsu, C.; Yin, M. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Coagulatory Activities of Caffeic Acid and Ellagic Acid in Cardiac Tissue of Diabetic Mice. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Beltrán, S.; Espada, S.; Orozco-Ibarra, M.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Cuadrado, A. Nordihydroguaiaretic Acid Activates the Antioxidant Pathway Nrf2/HO-1 and Protects Cerebellar Granule Neurons against Oxidative Stress. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 447, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-J.; Kukita, A.; Watanabe, T.; Takano, T.; Qu, P.; Sanematsu, K.; Ninomiya, Y.; Kukita, T. Nordihydroguaiaretic Acid Inhibition of NFATc1 Suppresses Osteoclastogenesis and Arthritis Bone Destruction in Rats. Lab. Investig. 2012, 92, 1777–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, A.; Martins, M.; Silva, P.; Garrido, E.M.; Garrido, J.; Firuzi, O.; Miri, R.; Saso, L.; Borges, F. Dietary Phenolic Acids and Derivatives. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Activity of Sinapic Acid and Its Alkyl Esters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11273–11280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, K.-J.; Koh, D.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Park, S.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Kim, D.-G.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, K.-T. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Sinapic Acid through the Suppression of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase, Cyclooxygase-2, and Proinflammatory Cytokines Expressions via Nuclear Factor-ΚB Inactivation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 10265–10272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soulage, C.; Soares, A.F.; Girotti, C.; Zarrouki, B.; Demarne, F.E.; Lagarde, M.; Géloën, A. Antioxidant Effect of Cirsimarin, a Flavonoid Extracted from Microtea Debilis. Phytopharm. Ther. Values II 2008, 20, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, Z.; Chang, X.; Xue, H.; Yahefu, W.; Zhang, X. 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic Acid Prevents Acute APAP-Induced Liver Injury by Increasing Phase II and Antioxidant Enzymes in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Li, W.; Tsubouchi, R.; Haneda, M.; Murakami, K.; Takeuchi, F.; Nisimoto, Y.; Yoshino, M. Rosmarinic Acid Inhibits the Formation of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species in RAW264. 7 Macrophages. Free Radic. Res. 2005, 39, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Zu, Y.; Lu, Q. Effects of Rosmarinic Acid on Liver and Kidney Antioxidant Enzymes, Lipid Peroxidation and Tissue Ultrastructure in Aging Mice. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, J.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Song, Z. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Psoralen in Human Periodontal Ligament Cells via Estrogen Receptor Signaling Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Al-Ani, M.K.; Sha, Y.; Chi, Q.; Dong, N.; Yang, L.; Xu, K. Psoralen Protects Chondrocytes, Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Effects on Synoviocytes, and Attenuates Monosodium Iodoacetate-Induced Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Guo, X.; Lin, L.; Lin, M.; Gong, Y.; Ying, B.; Huang, M. Effects of Angelicin on Ovalbumin (OVA)-Induced Airway Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Asthma. Inflammation 2016, 39, 1876–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Sun, G.; Gao, H.; Li, R.; Soromou, L.-W.; Chen, N.; Deng, Y.-H.; Feng, H. Angelicin Regulates LPS-Induced Inflammation via Inhibiting MAPK/NF-ΚB Pathways. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 185, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Ho, T.-Y.; Lee, E.-J.; Su, S.-Y.; Tang, N.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-L. Ferulic Acid Reduces Cerebral Infarct through Its Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Effects Following Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2008, 36, 1105–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-K.; Chung, Y.-C.; Hyun, C.-G. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of 6-Methylcoumarin in LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Macrophages via Regulation of MAPK and NF-ΚB Signaling Pathways. Molecules 2021, 26, 5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S.; Kim, E.-N.; Jeong, G.-S. Ameliorative Effect of Citropten Isolated from Citrus Aurantifolia Peel Extract as a Modulator of T Cell and Intestinal Epithelial Cell Activity in DSS-Induced Colitis. Molecules 2022, 27, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Ni, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, H.; Xiang, H.; Sui, H.; Shang, D. Emodin Attenuates Severe Acute Pancreatitis via Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Inflammation 2019, 42, 2129–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhao, L.; Mei, H.; Zhang, S.-L.; Huang, Z.-H.; Duan, Y.-Y.; Ye, P. Exploration of Emodin to Treat Alpha-Naphthylisothiocyanate-Induced Cholestatic Hepatitis via Anti-Inflammatory Pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 590, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Gong, F.-L.; Zhao, G.-B.; Li, J. Chrysin Suppressed Inflammatory Responses and the Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Pathway after Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 12270–12279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpavalli, G.; Kalaiarasi, P.; Veeramani, C.; Pugalendi, K.V. Effect of Chrysin on Hepatoprotective and Antioxidant Status in D-Galactosamine-Induced Hepatitis in Rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 631, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]