Featured Application

The multi-criteria evaluation tool developed in this study provides researchers, food manufacturers, and innovation stakeholders with a practical method for rapidly assessing the sustainability potential of circular economy valorisation processes. It enables early identification of environmental, economic, and social hotspots using minimal data requirements, supporting strategic decision-making before investing in detailed life cycle assessment or pilot-scale experimentation. The tool can be applied to compare alternative by-product valorisation routes, prioritise research and development (R&D) options, and guide the design of resource-efficient, scalable, and regulation-compliant solutions within the agri-food sector. Its structured approach is especially valuable for projects seeking to transform residues into high-value products, such as functional ingredients, supplements, or extended-shelf-life foods, within the broader framework of sustainable and circular food systems.

Abstract

Circular economy (CE) strategies in the agri-food sector hold strong potential for reducing waste, enhancing resource efficiency, and promoting sustainable value creation. However, early-stage assessment of innovative valorisation pathways remains challenging due to limited data availability and heterogeneous sustainability trade-offs. This study presents a multi-criteria evaluation tool designed to identify sustainability hotspots and support the preliminary screening of CE solutions based on easily obtainable information. The tool combines a structured literature review with expert-based scoring across environmental (ENV), economic (EC), and social (SOC) dimensions. Its applicability was demonstrated through the following three case studies: (i) reconstitution of cheese approaching expiration, (ii) extraction of polyphenols from grape-wine residues via subcritical water extraction, and (iii) biodegradable mulching film production from grape-wine pomace. Results show that the tool successfully differentiates sustainability performance across value chain areas Residue, Final Product, and Process (RES, FP, and PRO) and reveals critical gaps requiring further investigation. Scenario 3 achieved the higher overall score (69.7%) due to fewer regulatory constraints, whereas Scenarios 1 and 2 (61.2% and 54.5%, respectively) are penalised due to the more regulations for human consumption. The proposed tool offers a practical and efficient method to support researchers and industry stakeholders in identifying CE strategies with the highest potential for sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The urgency of transitioning towards circularity in the agri-food sector is increasingly evident amid the dual pressures of resource scarcity and environmental degradation. Circular economy principles aim to minimise waste and pollution, foster the continuous use of materials, and regenerate natural systems by creating closed-loop systems. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a thriving circular food economy can encompass strategies that “design out waste and pollution, keep products and materials in use, and regenerate natural systems” [1]. This framework allows for a comprehensive approach to managing food residues, transforming them from mere disposal into a resource that can be repurposed or recycled, thus promoting sustainability across the food supply chain [2,3]. The implications extend beyond immediate waste management concerns; they also align directly with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) associated with responsible consumption and production [4]. Lemaire and Limbourg argue that redesigning food supply networks to improve efficiency can yield considerable environmental benefits, emphasising the importance of optimising processes, reducing packaging, and enhancing byproduct utilisation [4].

Resource limitations have intensified calls for circular economies, as these frameworks encourage the closure of material loops; promoting recycling and reuse enhances both economic and environmental resilience. Hysa et al. illustrate that effective circular economy measures can enhance economic growth while ensuring sustainability, highlighting the interdependence between resource productivity, environmental innovation, and economic outcomes [5]. Álava et al. argue that adopting a circular view in agriculture can help tackle the substantial energy and environmental costs linked to traditional production methods, positioning sustainable agriculture as a mechanism to ensure long-term viability [6]. This perspective is echoed by Matysik-Pejas et al., who highlight that the circular economy is not merely a waste management strategy but a paradigm shift essential for optimising resource use under conditions of scarcity, climate change, and increased food demand [7].

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) emerges as a pivotal tool for evaluating the environmental performance of agriculture through a circular-economy lens. Pausta et al. emphasise the need for a proactive approach that integrates LCA in nutrient recovery from wastewater, illustrating how circular practices can enhance environmental sustainability and resource efficiency within agricultural systems [8]. Moreover, Luthin et al. provide an integrated framework for circular life cycle sustainability assessment, highlighting the importance of coupling LCA with indicators of circularity to effectively quantify the environmental impacts of agri-food production systems [9].

The relationship between circularity and sustainability is multifaceted; CE practices are intrinsically linked to broader sustainable development goals. Notably, Schroeder et al. indicate that circular economy practices are crucial for achieving targets related to sustainable consumption and production, clean water, affordable energy, and economic growth [10].

Research further highlights specific synergies between circularity and sustainability, wherein CE can mitigate environmental impacts by promoting practices such as resource efficiency, waste reduction, and renewable energy utilisation [11,12]. The comprehensive review by Castro et al. found that maximising resource lifecycles significantly reduces adverse environmental effects, reinforcing the argument for adopting circular economy frameworks as a viable alternative to conventional linear models [13].

Moreover, integrating circular economy principles into specific agricultural sectors, such as olive oil production, has been shown to enhance the resilience and sustainability of these systems, demonstrating a clear relationship between circular practices and improved outcomes [14]. The comprehensive adoption of CE frameworks fosters more efficient resource management, reduced emissions, and a sustainable approach that respects environmental boundaries [15].

Despite the positive aspects, implementing circular economy practices entails specific challenges. The trade-offs inherent in various CE strategies can result in differing impacts across sustainability dimensions, as explored by Ünal and Sinha [16]. This highlights the necessity for firms to carefully analyse how their circular strategies align with overall sustainability goals.

A variety of analytical methods have been developed to evaluate sustainability and circularity, each differing in scope, data requirements, and level of system detail. Among the most widely used are Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Environmentally Extended Input–Output Analysis (EEIOA). While both aim to provide comprehensive sustainability evaluations, LCA requires a large amount of detailed data on material and physical flows (for Life Cycle Inventory) and emission fate (for Life Cycle Impact Assessment), making it data- and time-intensive. EEIOA, in contrast, models systems based on economic flows, resulting in a less detailed but broader representation of sustainability interactions. Material Flow Analysis (MFA) provides an even more aggregated perspective, describing systems in terms of their material inputs and outputs over space and time, typically without incorporating social aspects. Methods such as emergy and exergy analyses focus mainly on environmental and energy-related dimensions. At the same time, operational research (OR) and complex systems approaches—although theoretically capable of detailed analyses—are often limited by computational constraints and data intensity [17].

Given these challenges, there is a clear need for a preliminary assessment approach that relies on a limited set of easily obtainable data to guide research and decision-making in identifying sustainable circular economy (CE) strategies. The present study aims to (i) identify key processes that represent potential hotspots in the sustainability performance of CE solutions and (ii) develop a preliminary sustainability evaluation framework capable of supporting the early-stage selection and optimisation of circular strategies. This approach provides a pragmatic pathway to narrow the research focus and allocate resources to the most promising and sustainable CE solutions [5,11,12,16,18,19,20].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

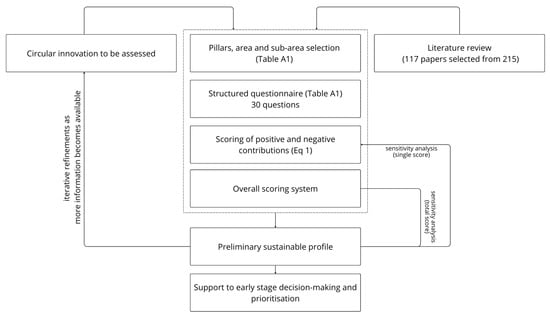

A literature review was conducted to identify the key phases within the value-enhancement process that may compromise its overall sustainability. The aim was to pinpoint potential critical areas that could negatively affect environmental, economic, or social performance. To ensure a comprehensive and evidence-based review, the Scite AI platform and Scopus were used to search and analyse peer-reviewed articles published between 2020 and 2025, enabling the identification of highly cited and contextually relevant studies. Keyword combinations included terms related to the circular economy and food by-product valorisation (e.g., “circular economy”, “food by-products”, “food waste valorisation”), as well as early-stage innovation contexts (e.g., “early-stage assessment”, “low TRL”, “ex-ante sustainability assessment”). The query returned a set of 225 peer-reviewed publications, from which 117 studies were selected and reported in Table A1. This approach facilitated efficient screening and verification of citation contexts, ensuring that the selected sources were credible and aligned with the goal of the current work, as shown in Figure 1. Based on the literature review, three main areas—residue (RES), final product (FP), and process (PRO)—were identified. Across these areas, a total of eight sub-areas were defined: regulations (REG), logistics (LOG), economy of the residue (ER), economy of the process (EP), market (MKT), solvents (SOL), process efficiency (EFF), and waste (WAS). Each area and sub-area was analysed with respect to its potential impact on the three sustainability pillars (SP): environmental (ENV), economic (EC), and social (SOC). The results collected by the questionnaire were subsequently classified both by sustainability dimension and by area to allow a comprehensive cross-analysis of sustainability relevance across phases. The results of this classification are summarised in Table A1, which provides an overview of the distribution of the literature and the relative contribution of each process area and sub-area to sustainability performance.

Figure 1.

Conceptual workflow of the proposed early-stage screening tool.

2.2. Questionnaire Development

A questionnaire was subsequently developed to investigate further the critical points identified in the structured literature review. Each question was explicitly linked to (i) a specific main area within the value-enhancement process, (ii) a specific sub-area, and (iii) to the SP. The questionnaire is designed to evaluate the sustainability performance of each process through qualitative judgments expressed on different scales as follows: (i) a binary scale (Yes/No), (ii) a Likert 1–3 scale, and (iii) a Likert 1–5 scale. For each question, an additional “I do not know” option is provided; this response is conservatively treated as a negative contribution in the scoring procedure. These responses were subsequently converted into a score from 0 to 1, enabling the transformation of expert-based qualitative insights into a structured, comparable dataset. The score S was calculated using Equation (1).

where P and N represent the positive and negative contributions of the answer to a question, and C is the completeness, a parameter used to determine if further investigation is needed for a specific valorisation process since sufficient information about the process itself is not available or provided. The completeness C assumes a value of 1 in all cases except when an answer “I do not know” is provided: in this case, a value of 0 is given. The score was calculated, assigning higher weights to positive contributions, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scores the value for each possible answer in the questionnaire.

Equation (1) was developed to reflect the logic of early-stage innovation screening, where the presence of enabling conditions and positive opportunities is often more informative than the precise quantification of risks. Positive contributions were therefore assigned a higher weight than negative ones, while the completeness factor (C) was introduced to penalise scores derived from insufficient information and to explicitly signal the need for further investigation. This weighting structure reflects a logical priority in innovation assessment: the capacity to create value and opportunity is more important than the capacity to avoid cost and risk. The values 0.7 and 0.3 were chosen to indicate that positive evidence is approximately twice as influential as the absence of negative evidence. Alternative weightings (0.5/0.5, 0.6/0.4, and 0.8/0.2) have been considered and assessed via sensitivity analysis.

Based on the collected responses, it was possible to determine a preliminary sustainability level for each CE measure, supporting the early-stage identification of processes with the highest potential for sustainable value enhancement by calculating the average of the scores for the questions related to ENV, EC, and SOC pillars. It should be noted that the SOC dimension has fewer indicators than the environmental and economic dimensions. This reflects an intrinsic limitation of early-stage CE assessments, where social impacts are often more context-dependent, qualitative, and difficult to quantify in the absence of mature value chains, consolidated organisational structures, or stable market deployment. Indicators such as employment creation, local community acceptance, or worker skill upgrading are highly dependent on scale, governance structure, and territorial context, and therefore difficult to robustly assess at an early innovation stage. Consequently, SOC indicators in this framework are intended to capture potential social implications rather than fully developed social performance outcomes.

Moreover, scores were calculated for each area/sub-area compartment, and the average score for each area was then determined. The total score was calculated as a weighted average of the RES, FP, and PRO areas’ scores, using weights of 0.3, 0.3, and 0.4, respectively. This approach assigns slightly greater importance to the process area than to the other two. In fact, it reflects the central role of the transformation stage in determining the net environmental footprint. Given that the residue characteristics are often fixed and product specifications are market-driven, the process stage represents the primary area for technical optimisation and impact mitigation. For the waste-related sub-area (WAS), a dedicated weighting approach was applied to account for the presence and relevance of additional waste streams generated along the valorisation pathway. The WAS is originally composed of six questions (see Appendix A), but the effective number of questions considered in the score calculation depends on whether additional waste is generated during the process (Q21). When no additional waste is produced, the scoring is based on a reduced set of questions, and the indicator related to waste generation during the process (Q21) is assigned a higher weight to reflect its dominant role in determining the environmental relevance of the sub-area. Conversely, when additional waste is generated, the weighting scheme is distributed across multiple waste-related aspects, including waste generation, valorisation potential, and hazardousness (Q21–Q24), while the contribution of the yield-related indicator (Q22) is modulated according to the relative amount of valorised material, as defined in Equation (2).

Indicators related to waste generated prior to the valorisation process (Q19–Q20) are always included with a lower and constant weight, reflecting their indirect influence on the overall sustainability performance. This approach ensures that the scoring system dynamically adjusts the relevance of waste-related indicators in line with the actual waste intensity of the valorisation pathway. Similarly, solvent-related questions are conditionally included in the analysis: when no solvent is used in the process (Q26), solvent-specific indicators (Q27–Q30) are excluded from the score calculation.

2.3. Questionnaire Administration

The primary objective of this phase was to assess the tool’s ability to identify the most promising circular economy (CE) solutions, namely those capable of generating consistent benefits across the three dimensions of sustainability, as a proof-of-concept rather than as a statistically representative survey. The questionnaire was applied as a proof-of-concept by the authors of the manuscript. The authors have formal academic training and research experience in sustainability assessment, circular economy, and agri-food processing, and are actively involved in applied projects on circular valorisation of food by-products. Their role was not that of independent external judges, but of informed users applying the tool to real case studies to test its operational applicability, internal coherence, and capacity to highlight sustainability hotspots and information gaps.

The questionnaire (Table A1) was developed as a methodological component of the proposed tool and was not administered to external human participants. Therefore, no data were collected from human subjects. No personal, sensitive, or identifiable data from third parties was involved. The questionnaire was tested by collecting information from three research activities in which circularity-oriented innovations were tested and implemented. Scenario 1 (SC1): The first valorisation process considered in this study is associated with the valorisation through upcycling of a cheese close to the expiration date. The process consists of the upcycling reconstitution of the product, which allows the extension of the shelf life. The cheese reconfiguration process was assumed to take place under conventional food-processing conditions, without introducing novel unit operations beyond those already used in dairy processing. For this process the following answers were provided as follows: (i) the residue is produced constantly during the year in all main Italian macro areas (north, south, centre); (ii) the FP has the same regulations as the main product; (iii) no other valorisations currently exist for this residue; and (iv) the process follows all regulations related to food production in terms of safety.

Scenario 2 (SC2): The second valorisation process considered is the extraction from wine residues of polyphenols with a sub-critical water extraction, as reported in [21,22]. Briefly, 180 °C and 11.5 bar for 30 min at 150 rpm using vacuum-dried grape stalks. For this process, the following answers were provided as follows: (i) the FP was considered a food supplement; (ii) the process follows all regulations related to food supplement production in terms of safety; (iii) water was not considered as a solvent; and (iv) grape stalks were considered unperishable.

Scenario 3 (SC3): The third valorisation process considered wine waste products, specifically grape pomace, used as a filler for a biodegradable mulching film. For this process, the following points were identified as follows: (i) the residue is generated during a specific period of the year across all major Italian macro-areas (North, Centre, and South); (ii) the process complies with all regulations related to food supplement production in terms of safety; and (iii) the residue is considered perishable but does not need to be stabilised for storage.

The parameters considered in the two scenarios were not used as quantitative inputs in the scoring system but served to contextualise the qualitative assessment.

2.4. Data Analysis

The responses were represented using R (version 4.4.3, R Core Team, 2025, Vienna, Austria) and the R Studio software (Version 2024.12.1; Posit Team, 2025, Boston, MA, USA). Results were synthesised in a matrix showing, for each combination of area × sub-area pillar, the corresponding share of positive outcomes. The visualisation adopted a colour-coded scale to enhance interpretability: from red (low share of positive outcomes) to green (high share). The colour scale was centred at 50% (yellow), with labels displaying the exact percentage of positive responses. The completeness grade was also shown for each compartment with a black or grey dot, indicating a completeness of less than or equal to 0.8 and greater than 0.8, respectively. The score for each sustainability pillar was also calculated and visualised as coloured graph bars in the same colour scale as for the matrix.

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Single Score and Total Score Weights

A deterministic sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the robustness of scenario rankings to changes in the single score and main area weights. Three alternative weighting coefficients were tested for the single score, and four alternative weighting schemes were tested for the total score, reflecting different decision-making perspectives (equal importance, process-oriented, residue-oriented, and market-oriented). Total sustainability scores were recalculated accordingly. A residue-driven scenario was tested to reflect decision contexts where feedstock availability and regulatory status represent the primary selection criteria, while a market-oriented scenario was included to represent decision contexts in which the economic value, stability, and market eligibility of the final product constitute the primary drivers for innovation selection, as is often the case for industrial stakeholders and investors.

2.6. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative Artificial Intelligence tools (ChatGPT v3.5, OpenAI, 2025; Grammarly v.1.2) were used exclusively for language editing and translation of manuscript text. No GenAI tools were used for data generation, analysis, or interpretation.

3. Results and Discussion

Results are presented in two steps: first, a structural overview of the applied questionnaire is provided to contextualise the analysis; second, the comparative sustainability performance of the two scenarios is discussed.

The application of the proposed evaluation tool involved the collection of information through a structured questionnaire composed of 30 questions, as derived from the literature review and described in Section 2. These questions were distributed across the three main process areas (RES, FP, and PRO) and the associated sub-areas to support the interpretation of the scenario-based results. Table A1 shows all the questions selected, starting from the literature review, with all the references associated with each question to justify the choice. Table A1 also includes Area, Processes, and Pillars related to every single question. When analysed by sustainability pillar, the applied questionnaire predominantly focused on economic (26 questions) and environmental (19 questions) aspects, while social considerations were captured through a smaller set of indicators (6 questions). This distribution influenced the sensitivity of the tool in differentiating ENV and EC performance between scenarios. Table 2 summarises the distribution of questions across the identified processes, providing a structural reference for the interpretation of the sustainability matrices presented later in this section. Fifteen questions were formulated as binary questions (yes, no), while the rest were formulated as Likert scales: two questions were in a Likert 1–3 scale, and 13 questions were in a Likert 1–5 scale.

Table 2.

Sub-Area number of questions.

The sensitivity analysis conducted on the weights used to calculate the single score for each question yields a total score ranging from 62.6% to 60.5% in SC1, from 55.0% to 54.3% in SC2, and from 71.7% to 68.8% in SC3. In all cases, increasing the weight on the positive contribution slightly reduced the overall score, indicating that the average positive contributions are marginally lower than the benefit derived from the absence of negative contributions. Importantly, SC3 > SC1 > SC2 for all tested weight values, and the difference between scenarios remains relatively stable. This suggests that the qualitative conclusion—namely, that SC3 and SC1 yield a higher valorisation score than SC2—is robust with respect to the specific choice of aggregation weight. Thus, the model’s ranking of scenarios does not critically depend on whether a weight of 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, or 0.8 is used for P in the scoring function.

The sensitivity analysis of the weights used to calculate the total score for each scenario is summarised in Table 3 and shows that the proposed tool is robust to reasonable variations in weighting schemes. While the preferred scenario depends on decision-maker priorities, the analysis confirms that differences between scenarios are structurally driven by regulatory, logistical, and technological factors rather than artefacts of arbitrary weighting. Under the residue-driven weighting scheme, the ranking of scenarios remained unchanged, with SC3 and SC1 outperforming SC2. This result reflects the strong structural differences between the scenarios in terms of residue availability, regulatory status, and perishability. Under the market-oriented weighting scheme, SC2 outperformed SC1, reflecting the higher stability and market potential of the polyphenol-based product compared to a reconstituted cheese product with limited shelf life.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis on the weights and scenario ranking.

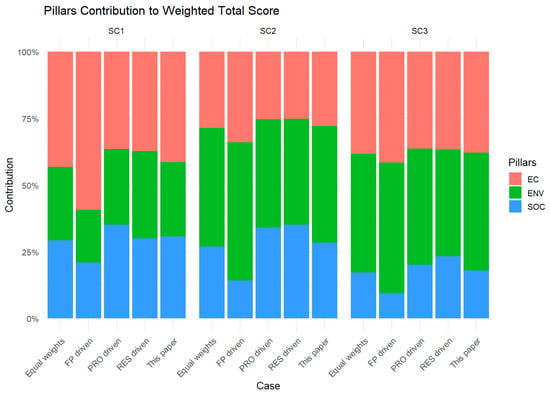

Figure 2 shows the sensitivity results of ENV, EC, and SOC pillar contributions to changes in area weighting schemes for SC1, SC2, and SC3. Overall, the results show that while the absolute contribution of each pillar varies with the adopted weighting scheme, the dominant sustainability dimensions and the relative balance among pillars remain largely consistent within each scenario, indicating a reasonable robustness of the tool.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity of the sustainability pillar scores (economic—EC, environmental—ENV, and social—SOC) to changes in area weighting schemes for SC1 (cheese near expiration), SC2 (polyphenol extraction from wine residues), and SC3 (biodegradable mulching film from wine residues).

For SC1, the results obtained using the weighting scheme proposed in this paper show a predominant economic contribution (EC ≈ 41%), followed by the social (SOC ≈ 31%) and environmental (ENV ≈ 28%) pillars. A very similar distribution is observed under the equal-weight scheme, suggesting that the baseline weighting does not strongly bias the results toward a specific pillar. When the process-driven (PRO-driven) weighting is applied, the social pillar becomes more prominent (SOC ≈ 35%), reflecting the stronger emphasis of process-related aspects on organisational, operational, and workforce-related dimensions. In contrast, the final-product-driven (FP-driven) scheme markedly amplifies the economic contribution (EC ≈ 59%), while reducing both environmental and social contributions. This highlights how market-related and product performance criteria tend to dominate sustainability outcomes when final product aspects are prioritised. Conversely, the residue-driven (RES-driven) scheme increases the environmental contribution (ENV ≈ 33%), confirming that residue-related criteria are more closely associated with environmental performance. Despite these shifts, the overall balance among pillars remains coherent, and no inversion of sustainability dominance occurs.

In SC2, the environmental pillar is dominant across all weighting schemes, with ENV contributions ranging from approximately 40% to 52%. Under the baseline and equal-weight schemes, ENV accounts for around 44–45% of the total score, while EC and SOC contribute more evenly but at lower levels. The FP-driven scheme further reinforces the environmental dominance (ENV ≈ 52%), while simultaneously reducing the social contribution to its lowest level (SOC ≈ 14%). This indicates that, for SC2, product-oriented criteria primarily capture environmental benefits, while social aspects are comparatively weaker or less explicitly addressed. The PRO-driven and RES-driven schemes both increase the relative importance of the social pillar (SOC ≈ 34–35%), suggesting that process organisation and residue management play a significant role in enhancing social sustainability in this scenario. Importantly, the persistence of environmental dominance across all schemes suggests that SC2 is intrinsically environmentally oriented, regardless of the adopted weighting assumptions.

For SC3, the results indicate a dual dominance of environmental and economic pillars, with ENV contributions consistently around 44–49% and EC contributions between 36% and 42% under most schemes. The social pillar systematically contributes the least, particularly under the FP-driven scheme (SOC ≈ 9%), highlighting a potential weakness of this scenario in terms of social sustainability. As in the other scenarios, the FP-driven weighting accentuates economic and environmental contributions at the expense of social aspects, whereas the PRO-driven and RES-driven schemes partially rebalance the results by increasing the social contribution (SOC ≈ 20–23%). Nonetheless, even under these schemes, social performance remains secondary, indicating a structural limitation of SC3 rather than an artefact of weighting choices.

Across all three scenarios, the sensitivity analysis shows that changes in weighting schemes affect the magnitude of pillar contributions but not the overall sustainability profile of each scenario. Scenarios characterised by strong environmental or economic performance retain these features under all tested schemes, supporting the robustness of the tool for early-stage screening purposes. The analysis also confirms the complementarity of the weighting schemes: FP-driven weights emphasise market and economic performance, RES-driven weights highlight environmental benefits, and PRO-driven weights tend to strengthen social contributions. This behaviour is consistent with the conceptual design of the tool and demonstrates its ability to make trade-offs between sustainability pillars explicit. Overall, these results reinforce the suitability of the proposed framework as an exploratory, decision-support tool, capable of revealing how strategic priorities influence sustainability outcomes while maintaining coherent and interpretable results under different assumptions.

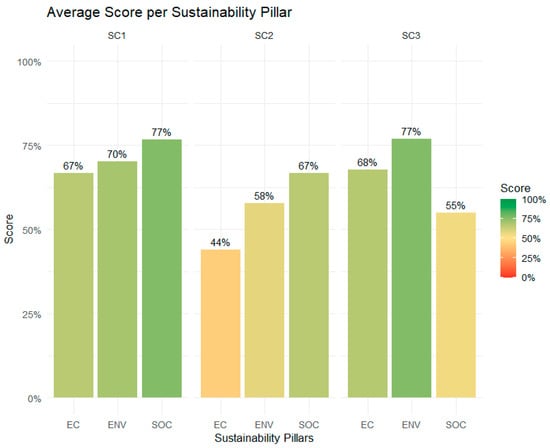

The answers are reported in Table A1, in columns SC1, SC2, and SC3. Figure 3 shows the score for each SP for both scenarios considered in this study. The researcher’s level of knowledge when considering the three SPs is good enough to avoid the need for further investigation, except for ENV in SC2. In SC1 and SC2 cases, SOC is the category with the higher score, and EC is the worst. This trend is not observed for SC3, where a score of 55% is obtained. This score reflects the nature of the valorisation process, where the researcher indicates the absence of a potential partner company.

Figure 3.

Sustainability pillars scores (economic—EC, environmental—ENV, and social—SOC) for Scenario 1 (cheese near expiration) and Scenario 2 (polyphenol extraction from wine residues). Bar colours and the colour scale represent the share of positive outcomes using a red–yellow–green gradient centred at 50%.

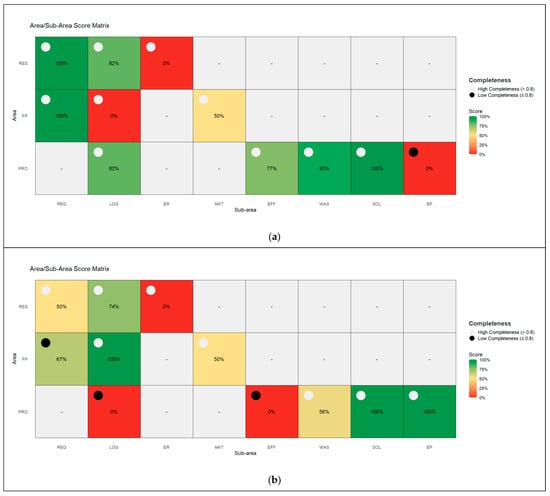

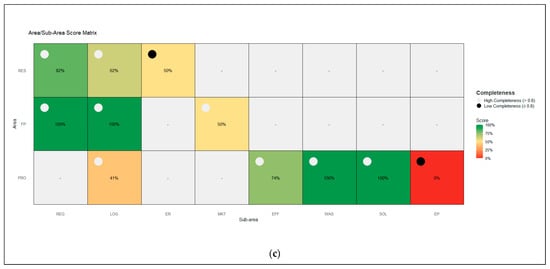

When considering the area/processes clustered matrix shown in Figure 4, it is possible to see that some of the investigated processes need further investigation to promote the innovation of the valorisation process, as indicated by the black dots in the upper left corner of each area/sub-area compartment.

Figure 4.

Area × sub-area sustainability matrix for Scenario 1 (a), Scenario 2 (b), and Scenario 3 (c) showing the percentage of positive expert responses. Black and grey dots indicate completeness levels ≤ 0.8 and >0.8, respectively.

SC2 requires additional investigation across the LOG, EFF, and REG sub-areas, whereas SC1 needs further analysis only within the EP. SC3 instead needs further investigations in both the economy of the residue (ER) and of the product (EP). SC1 includes a compartment with a 0% score in all three assessment areas, while SC2 presents two compartments scoring 0%, and SC3 presents only the EP compartment with a score of 0%. Overall, as shown in Table 4, the three areas exhibit a generally satisfactory performance. Despite containing the same number of compartments with a 0% score, SC1 nonetheless achieves a slightly higher overall score than SC2 (61.2% vs. 54.5%).

Table 4.

Area scores and the weighted average total of Scenario 1, 2, and 3.

Considering the RES area, SC1 and SC3 perform better than SC2. This difference arises from the fact that grape-wine residues are already valorised through established pathways, such as distillation, which reduces the relative attractiveness of alternative valorisation options. In contrast, no comparable valorisation routes currently exist for cheese approaching its expiration date.

In contrast, SC2 (together with SC3) performs better in the FP area, despite a higher level of uncertainty. This outcome is mainly due to the intrinsic nature of the valorisation process: the upcycling of a fresh product results in a product that remains fresh and therefore retains a limited shelf life compared to a stable, polyphenol-rich product or a biodegradable mulching film.

Finally, the PRO area yields better results for SC1 than for SC2 and SC3. In SC1, the valorisation process can be implemented within existing facilities using already available equipment, requiring primarily organisational and logistical adaptations rather than substantial technological upgrades. By contrast, in SC2, the current standard valorisation route is distillation, and alternative uses of grape-wine residues would require dedicated processing technologies and additional infrastructural investments, which may hinder large-scale deployment. Finally, in SC3, the current valorisation is still at lab scale, requiring additional investment to scale up the process.

Treating “I do not know” responses as the worst-case contribution represents a conservative assumption that may penalise low-TRL innovations, where information scarcity is intrinsic. This choice was made deliberately to emphasise uncertainty and guide further data collection rather than to provide definitive sustainability scores.

The growing interest in CE strategies has led to a rapid expansion of assessment tools aimed at evaluating circularity and sustainability performance. However, the recent literature highlights that, despite this methodological richness, decision-makers still face significant difficulties in selecting appropriate tools, particularly at early stages of valorisation processes characterised by limited data availability and low technological maturity [23]. Recent reviews emphasise that sustainability assessment of circular processes frequently relies on the integration of methods such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Life Cycle Costing (LCC), and Social LCA to overcome the limitations of single-method approaches [23]. While these integrated frameworks provide robust and comprehensive evaluations, they generally require detailed inventories, consolidated process configurations, and substantial analytical effort, making them less suitable for preliminary screening. Similarly, studies focusing on LCA-supported circular design strategies confirm the effectiveness of LCA in identifying environmental hotspots and trade-offs but also point to methodological inconsistencies, data limitations, and reduced applicability in early design or innovation phases [24]. In most cases, existing approaches are applied ex post to validate selected strategies, rather than ex ante to support prioritisation among alternative valorisation pathways. The tool proposed in this study addresses this gap by offering a qualitative, multi-dimensional screening framework explicitly designed for early-stage CE applications. Rather than replacing integrated assessment methods, it complements them by enabling an initial prioritisation of scenarios before engaging in data-intensive analyses. Unlike many circularity metrics that focus mainly on material efficiency or end-of-life performance, the framework explicitly incorporates organisational and logistical aspects, in line with recent calls for more system-oriented CE assessments [23].

From a methodological standpoint, the tool proved effective in capturing how the same area can differ in relevance across valorisation pathways. The analysis of completeness levels also showed that the tool is capable of highlighting where additional expert knowledge or empirical data are needed. A key strength of the proposed tool lies in its ability to transform qualitative expert judgements into structured, quantitative indicators. This is particularly valuable in early stages of innovation, where detailed LCA or techno-economic analysis may be impractical. Rather than replacing LCA, the proposed tool functions as a pre-screening mechanism that reduces the number of candidate options requiring full life-cycle analysis. By emphasising the relative importance of positive contributions over the avoidance of negative impacts, the scoring system aligns with the innovation-oriented logic of CE strategies.

Several recent studies in the sustainability and circular economy literature have developed and applied multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) frameworks to support valorisation and circular strategies in agricultural or waste management contexts. For example, Lombardi & Todella (2023) review MCDA applications for agricultural waste management, highlighting how indicator-based methods support sustainability evaluation of treatment and valorisation options [25]. Similarly, Coluccia et al. (2024) explore MCDM to prioritise circular strategies in agri-food systems [26], and Pamučar et al. (2022) apply MCDM to prioritise barriers to converting agricultural residues into building materials [27]. The tool proposed in this study differs from existing circular economy (CE) assessment frameworks in both scope and purpose. While some established approaches aim to provide a comprehensive, quantitative measurement of corporate circularity across multiple dimensions [26], the present tool is designed as an early-stage, exploratory screening instrument to support preliminary decision-making regarding circular innovation options. Multi-level frameworks based on multi-criteria decision-making methods (such as AHP combined with aggregation models) are primarily intended to assess, compare, and benchmark the overall circularity performance of firms. These approaches require structured data collection, a predefined set of indicators, and a sufficient level of data availability and maturity within the organisation. By contrast, the tool proposed here is explicitly designed to operate under conditions of uncertainty, partial information, and early innovation stages, where detailed data are often unavailable or unreliable. Accordingly, rather than aiming at precise measurement or formal benchmarking, the purpose of the tool is to highlight potential sustainability hotspots, identify information gaps, and support the initial selection of the most promising circular economy solutions. It therefore serves a complementary function to more comprehensive assessment frameworks: it can be used upstream to orient strategic reflection and prioritisation before more resource-intensive and data-demanding evaluation tools are applied.

In this sense, the proposed tool should not be interpreted as an alternative to existing multi-level CE assessment models, but as a preliminary decision-support layer that facilitates their subsequent and more targeted use. A recent critical review of sustainability integration into early-stage product development highlights the scarcity of practical, multi-criteria decision-making tools that effectively balance environmental, economic, and social sustainability when data are limited [28]. The review highlights the challenge of managing trade-offs and uncertainties in early innovation contexts, noting that few frameworks comprehensively address these issues. The screening tool proposed in this manuscript directly responds to these gaps by integrating a structured questionnaire, a completeness parameter to signal information gaps, and a sensitivity analysis to explore trade-offs across sustainability pillars, thereby offering an operational early-stage assessment framework that is otherwise underrepresented in the literature.

The sensitivity analysis shows that the proposed tool is robust with respect to reasonable variations in weighting schemes. While the preferred scenario depends on decision-maker priorities, the analysis confirms that differences between scenarios are structurally driven by regulatory, logistical, and technological factors rather than artefacts of arbitrary weighting. The stability of results under residue-driven weighting indicates that upstream constraints related to feedstock characteristics exert a dominant influence on the overall sustainability performance at early innovation stages.

The tool, therefore, acts as a decision-support mechanism that can guide researchers, firms, and policymakers towards valorisation options with the highest potential sustainability performance. Nonetheless, some limitations should be acknowledged. The tool relies on expert judgement, which may carry subjectivity and depend on the specific knowledge domain of the respondents. Formal testing of internal consistency and construct validity was not conducted, as the tool is intended as a qualitative screening instrument rather than a psychometric scale. Moreover, while the weighting system is rationally structured, it still reflects methodological choices that may evolve as new validation studies become available. Future refinements may include sensitivity analyses on weights, integration of semi-quantitative LCA indicators, and enlargement of the expert pool to enhance representativeness and for a formal validation. Overall, the results illustrate that the proposed tool can effectively complement more data-intensive sustainability assessment methods, helping narrow the set of viable CE strategies before committing resources to in-depth analysis.

4. Conclusions

This study developed and applied a multi-criteria evaluation tool to support the early-stage sustainability assessment of circular economy valorisation processes. By integrating literature-derived sustainability drivers with expert-based qualitative scoring across environmental, economic, and social dimensions, the framework enables a rapid and structured screening of innovative circular solutions under conditions of limited data availability.

Application to three contrasting agri-food case studies demonstrated the tool’s ability to perform the following: (i) identify sustainability hotspots and data gaps at an early stage, (ii) distinguish the influence of regulatory, logistical, and technological constraints across alternative valorisation pathways, and (iii) support the prioritisation of circular economy options with higher potential for sustainable value creation. SC3—which features an agricultural product—achieved a higher score than SC1 and SC2. This is likely because the products in the latter scenarios are intended for human consumption and are therefore subject to stricter regulatory constraints. The sensitivity analysis further confirmed the robustness of the results with respect to reasonable variations in weighting schemes, indicating that scenario rankings are driven primarily by structural characteristics rather than methodological artefacts.

Nevertheless, this study presents some limitations. First, the tool relies on expert judgement, which may introduce subjectivity and depend on the knowledge and experience of the respondents. Second, the qualitative and early-stage nature of the assessment does not allow for direct comparison with fully quantitative LCA or techno-economic results. Third, the limited number of social indicators reflects the difficulty of assessing social impacts prior to large-scale implementation.

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the circular economy literature by bridging the gap between high-level conceptual frameworks and data-intensive sustainability assessment methods. The proposed tool operationalises circular economy principles into a structured, multi-dimensional screening framework that explicitly accounts for process maturity, regulatory context, and organisational feasibility. From a practical standpoint, the tool can support researchers, technology developers, and industry stakeholders in prioritising valorisation pathways before committing resources to detailed analyses or pilot-scale investments. For example, it can be used by food manufacturers to compare alternative by-product uses, by R&D managers to identify sustainability hotspots at low TRLs, or by policymakers to screen circular economy projects for funding eligibility.

While the tool was tested within the agri-food sector, its underlying structure—based on residue characteristics, process configuration, market and regulatory conditions, and sustainability pillars—is not sector-specific. As such, the framework can be readily adapted to other contexts where by-product valorisation and circular innovation are relevant, including the bio-based industry, chemicals, construction materials, textiles, and waste management systems.

Future research will focus on validating the tool across a broader range of case studies and sectors, expanding the expert pool, and progressively integrating semi-quantitative indicators from life cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis. In this way, the proposed framework can function as a versatile pre-screening instrument that complements established sustainability assessment methods and supports informed decision-making across diverse circular economy applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; methodology, L.L. and D.V.; software, D.V.; validation, L.L., M.T., and D.V.; formal analysis, D.V. and S.W.K.; investigation, D.V. and S.W.K.; resources, D.V., L.L., and S.W.K.; data curation, D.V. and L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L., D.V., N.A.S., M.T., E.M., and S.W.K.; visualisation, D.V.; supervision, L.L.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “ON Foods—Research and innovation network on food and nutrition Sustainability, Safety and Security—Working ON Foods” grant number PE0000003. CUP B83C22005120006 is funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 04 Component 2 Investment 1.5—NextGenerationEU, Call for tender n. 3277 dated 30/12/2021. Award Number: 0001052, dated 23/06/2022. This work was also supported by the Project National Center for the Development of New Technologies in Agriculture (Agritech), funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4—Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n. 3175 of 18 December 2021 of the Italian Ministry of University and Research, funded by the European Union, NextGenerationEU, Project code_CN 00000022, Concession Decree No. 1032 of 17 June 2022, adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Doctoral School on the Agro-Food System (Agrisystem) of the Università Cattolica Del Sacro Cuore (Italy), ON Foods—Research and innovation network on food and nutrition Sustainability, and the Project National Center for the Development of New Technologies in Agriculture (Agritech).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SP | Sustainability Pillars |

| ENV | Environment |

| EC | Economy |

| SOC | Social |

| RES | Residue |

| FP | Final Product |

| PRO | Process |

| REG | Regulations |

| LOG | Logistics |

| ER | Residue economy |

| MKT | Market |

| EFF | Efficiency |

| WAS | Waste |

| EP | Process economy |

| SOL | Solvent |

| IDN | I do not know |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire used for the multi-criteria evaluation tool, including process areas (A), sub-areas (S-A), economy (EC), environmental (ENV), and society (SOC) sustainability pillars, references (Ref.), and expert scores for Scenario 1 (SC1) and Scenario 2 (SC2). RES: residue; FP: final product; PRO: process; REG: regulations; LOG: logistics; ER: residue economy; MKT: market; EFF: efficiency; WAS: waste; EP: process economy; SOL: solvent; IDN: I do not know. The symbol # represents the question number.

Table A1.

Questionnaire used for the multi-criteria evaluation tool, including process areas (A), sub-areas (S-A), economy (EC), environmental (ENV), and society (SOC) sustainability pillars, references (Ref.), and expert scores for Scenario 1 (SC1) and Scenario 2 (SC2). RES: residue; FP: final product; PRO: process; REG: regulations; LOG: logistics; ER: residue economy; MKT: market; EFF: efficiency; WAS: waste; EP: process economy; SOL: solvent; IDN: I do not know. The symbol # represents the question number.

| # | A | S-A | IC | Question | Ref. | SC1 | SC2 | SC3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RES | REG | EC | The residue intended for valorisation has regulatory constraints on its use. | [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] | no | yes | no |

| 2 | RES | REG | EC | The residue intended for the valorisation is legally classified (1) not as a waste; (2) as waste, but at the end of the process will achieve the classification “end of waste” (3) as waste, but you do not know if it will be “end of waste”. | [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | RES | LOG | ENV, EC | The residue intended for valorisation is produced at the national level (1) 1 month/year; (2) 2–4 months/year; (3) 5–7 months/year; (4) months/year; (5) more than >10 months/year. | [33,34,35,36,37,38] | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | RES | LOG | ENV, EC | The residue intended for the valorisation is produced in the selected period of time (1) in a far region; (2) in a different region in a relative close national area; (3) in a different region in the same national area (north, centre, south); (4) in all main national areas (north, centre, south); (5) in all national regions. | [44,45,46,47,48] | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 5 | RES | LOG | ENV, EC, SOC | The residue intended for valorisation is (1) not perishable/fermentable; (2) perishable/fermentable but does not need to be stabilised for storage; (3) perishable/fermentable and needs to be stabilised for storage. | [39,40,41,49,50,51] | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | RES | ER | EC | The residue intended for valorisation (1) has a management cost for the company; (2) is less than 1%; (3) is between 1 and 5%; (4) is between 5 and 10%; (5) is more than 10% of the main product. | [35,37,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 7 | RES | ER | EC | The residue intended for valorisation is already valorised in another process. | [40,60,61,62] | no | yes | IDN |

| 8 | PRO | LOG | ENV, EC | The valorisation process can be carried out: (1) at far companies (>100 km) with specific transportation conditions; (2) at far companies (>100 km) without specific transportation conditions; (3) at close companies with specific transportation conditions; (4) at close companies without specific transportation conditions; (5) within the company. | [13,44,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] | 5 | IDN | 4 |

| 9 | FP | MKT | EC | The final product of the valorisation process can be obtained from other routes. | [37,44,79,80,81] | yes | yes | yes |

| 10 | FP | REG | EC | The final product of the valorisation process is eligible for the market (does not require additional phases and tests). | [82,83,84,85,86] | yes | yes | yes |

| 11 | FP | MKT | EC | The final product of the valorisation process has a recognised market value or application as a secondary raw material. | [87,88,89,90,91,92] | yes | yes | yes |

| 12 | FP | REG | EC | The final product of the valorisation process needs authorisations or certifications to be placed on the market. | [29,93,94,95,96,97] | no | IDN | no |

| 13 | FP | LOG | ENV, EC | The final product of the valorisation process is (1) stable over a very short time (<1 month) in some specific conditions; (2) stable over a short time (<3 months) in some specific conditions; (3) stable over a short time (<3 months) in every conditions; (4) stable over a long time (>6 months) in some specific conditions; (5) stable over a long time (>6 months) in every conditions. | [79,98,99,100,101] | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| 14 | FP | REG | EC | The final product of the valorisation process complies with the applicable safety and quality standards (e.g., REACH, CLP, and HACCP). | [86,94,102,103,104,105,106,107,108] | yes | yes | yes |

| 15 | PRO | EFF | ENV, EC | The valorisation process requires (1) more than double the time and/or steps; (2) more time and/or steps; (3) the same time and/or steps; (4) half the time and/or steps; (5) less than half the time and/or steps of the main product production. | [33,34,35,37,38,39] | 3 | IDN | 5 |

| 16 | PRO | LOG | EC, SOC | Availability of potential partner companies capable of using the enterprise’s by-products as raw materials: (1) no potential partner company; (2) at least 1 potential partner company in a radius >100 km; (3) at least 1 potential partner company in a radius of 100 km; (4) at least 3 potential partner companies in a radius of 100 km; (5) more than 3 potential partner companies in a radius of 100 km. | [44,55,83,94,109,110,111,112] | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 17 | PRO | EFF | EC | The Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of the valorisation process is (1) basic research (TRL 1&2), (2) lab validation (TRL 3&4), (3) Relevant testing (TRL 5&6), (4) operational qualification (TRL 7&8), (5) full deployment (TRL 9). | [39,113,114] | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 18 | PRO | EFF | ENV, EC | The valorisation process (1) is only available at pilot scale; (2) can be further optimised to double the capacity of the pilot; (3) can be further optimised to 5 times capacity of the pilot; (4) can be further optimised to at least 10 times the capacity of the pilot; (5) can be scaled up to industrial scale to exceed 10 times the capacity of a pilot plant. | [62,83,115,116,117,118] | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| 19 | PRO | WAS | ENV, EC | Additional wastes are generated before the valorisation process (e.g., packaging required for transportation). | [44,119,120,121] | yes | no | no |

| 20 | PRO | WAS | ENV, EC | Additional wastes generated before the valorisation process are recyclable. | [122,123,124,125] | yes | - | - |

| 21 | PRO | WAS | ENV, EC | Additional wastes are generated during the valorisation process (e.g., residues of the extraction). | [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40] | no | yes | no |

| 22 | PRO | WAS | ENV, EC | The ratio between valorised product and total residue intended to be valorised is (1) less than 10%, (2) between 10 and 20%, (3) between 20 and 30%, (4) between 30 and 40%, (5) more than 50%. | [126,127,128] | 5 | 1 | - |

| 23 | PRO | WAS | ENV, EC | Additional wastes from the valorisation process (1) cannot be further valorised; (2) can be valorised with high energy consumption; (3) can be potentially valorised; (4) are already considered for further valorisation; (5) can be further valorised (e.g., for energy recovery). | [34,44,62,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136] | - | 5 | - |

| 24 | PRO | WAS | ENV, EC | Additional wastes from the valorisation process should be treated as hazardous/special wastes. | [33,34,35,36] | no | no | - |

| 25 | PRO | EP | ENV, EC | The valorisation process requires (1) more than 200%, (2) between 100% and 150%, (3) between 50 and 100%, (4) between 10 and 50%, (5) less than 10% of the main product cost. | [34,44,135,136] | IDN | 5 | IDN |

| 26 | PRO | SOL | ENV, SOC | Solvents are used in the valorisation process. | [83,86,98,137] | no | no | no |

| 27 | PRO | SOL | ENV, SOC | Chlorinated solvents are used in the valorisation process. | [138,139,140,141,142] | - | - | - |

| 28 | PRO | SOL | ENV, EC | Solvents (1) cannot be recovered; (2) require to recover more than 0.3 kWh/L; (3) require to recover between 0.2 and 0.3 kWh/L; (4) require to recover between 0.2 and 0.1 kWh/L; (5) require to recover less than 0.1 kWh/L. | [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,142,143,144,145] | - | - | - |

| 29 | PRO | SOL | ENV, SOC | Solvents (or other chemicals) needed in the valorisation process are characterised by having R39/23/24/25 phrases. | [33,34,35,36,37,38,39] | - | - | - |

| 30 | PRO | SOL | ENV, SOC | Solvents (or other chemicals) needed in the valorisation process are characterised by having R50/53 phrases. | [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] | - | - | - |

References

- Liaros, S. Circular Food Futures: What Will They Look Like? Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, K.d.S.; Lima, T.A.d.C.; Alves, L.R.; Rios, P.A.D.P.; Motta, W.H. The Circular Economy Approach for Reducing Food Waste: A Systematic Review. Rev. Produção Desenvolv. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigdeloo, M.; Teymourian, T.; Kowsari, E.; Ramakrishna, S.; Ehsani, A. Sustainability and Circular Economy of Food Wastes: Waste Reduction Strategies, Higher Recycling Methods, and Improved Valorization. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2021, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, A.; Limbourg, S. How Can Food Loss and Waste Management Achieve Sustainable Development Goals? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, E.; Kruja, A.; Rehman, N.U.; Laurenti, R. Circular Economy Innovation and Environmental Sustainability Impact on Economic Growth: An Integrated Model for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Álava, F.; Guerrero, F.; Varas Maenza, C.; Solis Barros, T. Circular Economy Vision for Local Development Focused on Waste Derived from Two Agricultural Crops in Ecuador. J. Bus. Entrep. Stud. 2022, 6, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysik-Pejas, R.; Bogusz, M.; Daniek, K.; Szafrańska, M.; Satoła, Ł.; Krasnodębski, A.; Dziekański, P. An Assessment of the Spatial Diversification of Agriculture in the Conditions of the Circular Economy in European Union Countries. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausta, C.M.; Kalbar, P.; Saroj, D. Life Cycle Assessment of Nutrient Recovery Strategies from Domestic Wastewaters to Quantify Environmental Performance and Identification of Trade-Offs. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthin, A.; Traverso, M.; Crawford, R.H. Circular Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment: An Integrated Framework. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, P.; Anggraeni, K.; Weber, U. The Relevance of Circular Economy Practices to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. Green Logistics Practices Toward a Circular Economy: A Way to Sustainable Development. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2024, 15, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamam, M.; Chinnici, G.; Di Vita, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Pecorino, B.; Maesano, G.; D’Amico, M. Circular Economy Models in Agro-Food Systems: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado Castro, A.; Maldonado Castro, J.; Yela Burgos, R.; Moreno Suqilanda, E. Circular Economy and Its Impact on Environmental Sustainability. Cent. Sur 2022, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, E.; Carlucci, D.; Cembalo, L.; Chinnici, G.; D’Amico, M.; Falcone, G.; Giannoccaro, G.; Gulisano, G.; Iofrida, N.; Stempfle, S.; et al. Evaluating Circular Strategies for the Resilience of Agri-Food Business: Evidence from the Olive Oil Supply Chain. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 2748–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodino, S.; Pop, R.; Sterie, C.; Giuca, A.; Dumitru, E. Developing an Evaluation Framework for Circular Agriculture: A Pathway to Sustainable Farming. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Sinha, V.K. Sustainability Trade-Offs in the Circular Economy: A Maturity-Based Framework. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 4662–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzberg, J.; Lonca, G.; Hanes, R.J.; Eberle, A.L.; Carpenter, A.; Heath, G.A. Do We Need a New Sustainability Assessment Method for the Circular Economy? A Critical Literature Review. Front. Sustain. 2021, 1, 620047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jácome, R.A. Vinculación Social En Época de Protestas: Algunos Apuntes Sociológicos–Epistemológicos. Cent. Sur 2022, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Esteva, L.C.; Kasliwal, A.; Kinzler, M.S.; Kim, H.C.; Keoleian, G.A. Circular Economy Framework for Automobiles: Closing Energy and Material Loops. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubelskas, U.; Skvarciany, V. Circular Economy Practices as a Tool for Sustainable Development in the Context of Renewable Energy: What Are the Opportunities for the EU? Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 833–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, P.A.V.; Meyer, S.; Hernández-García, E.; Rebaque, D.; Vilaplana, F.; Chiralt, A. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Extracts from Grape Stalks Obtained with Subcritical Water. Potential Use in Active Food Packaging Development. Food Chem. 2024, 451, 139526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voccia, D.; Milvanni, G.; Leni, G.; Lamastra, L. Life Cycle Assessment and Circular Economy Evaluation of Extraction Techniques: Energy Analysis of Antioxidant Recovery from Wine Residues. Energies 2025, 18, 4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.; Bimpizas-Pinis, M.; Ncube, A.; van Langen, S.K.; Genovese, A.; Zucaro, A.; Fiorentino, G.; Coleman, N.; Ghisellini, P.; Passaro, R.; et al. Integration of Methods for Sustainability Assessment of Potentially Circular Processes—An Innovative Matrix Framework for Businesses and Policymakers. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 507, 144580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsafi, A.; Togiani, A.; Colley, A.; Varis, J.; Horttanainen, M. Life Cycle Assessment in Circular Design Process: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 521, 146188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, P.; Todella, E. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis to Evaluate Sustainability and Circularity in Agricultural Waste Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluccia, B.; Palmi, P.; Krstić, M. A Multi-Level Tool to Support the Circular Economy Decision-Making Process in Agri-Food Entrepreneurship. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1099–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamučar, D.; Behzad, M.; Janosevic, M.; Aburto Araneda, C.A. A Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Framework for Prioritizing and Overcoming Sectoral Barriers in Converting Agricultural Residues to a Building Material. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, T.; Arnold, M.G.; Engesser, S.; Gerald van den Boogaart, K. Integrating Sustainability Facets into the Early Stages of New Product Development Using Multi-Criteria Tools—A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 517, 145834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihwughwavwe, S.I.; Siwe Usiagu, G. A Theoretical Framework for Sustainable Recycling of Polyurethane Foam Waste in Industrial Applications. Eng. Technol. J. 2025, 10, 6847–6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, H.J.M.; Ismael, K.; Abdulla, R.J. Sustainable Recycling of Vehicle Lubricant and Engine Oils for Environmental Protection. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Goals 2025, 1, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, N.S.; Patrício, J. Energy Efficiency and Waste Reduction Through Maintenance Optimization: A Case Study in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Waste 2025, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, C. Evaluation of Circular Skills and Circular Mind-Set of Consumers with the Use of It—Case Study in a Sample of Consumers in Northeast Brazil Compared to a Sample of Internal Stakeholders of an Industry in Transition to the Circular Economy. Int. J. Complement. Altern. Med. 2023, 16, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Singh, S.K. A Life Cycle Approach to Environmental Assessment of Wastewater and Sludge Treatment Processes. Water Environ. J. 2022, 36, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickram, S.; Infant, S.S.; Balamurugan, B.S.; Jayanthi, P.; Sivasubramanian, M. Techno-Economic and Life Cycle Analysis of Biorefineries: Assessing Sustainability and Scalability in the Bioeconomy. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2025, 34, e70077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, A.; Fiorentino, G.; Colella, M.; Ulgiati, S. Upgrading Wineries to Biorefineries within a Circular Economy Perspective: An Italian Case Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, F.; Vignati, J.A.; Marchi, B.; Paoli, R.; Zanoni, S.; Romagnoli, F. Effects of Energy Efficiency Measures in the Beef Cold Chain: A Life Cycle-Based Study. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2021, 25, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjoveanu, G.; Pătrăuțanu, O.A.; Teodosiu, C.; Volf, I. Life Cycle Assessment of Polyphenols Extraction Processes from Waste Biomass. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, M.T.O.V.; Dayarathne, G.L.N. Application of Life Cycle Framework for Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Circular Economy Perspective from Developing Countries. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 899–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musharavati, F.; Sajid, K.; Anwer, I.; Nizami, A.S.; Javed, M.H.; Ahmad, A.; Naqvi, M. Advancing Biodiesel Production System from Mixed Vegetable Oil Waste: A Life Cycle Assessment of Environmental and Economic Outcomes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, G.; Giannetti, B.F.; Agostinho, F.; Liu, G.; Almeida, C.M.V.B. Prioritizing Cleaner Production Actions towards Circularity: Combining LCA and Emergy in the PET Production Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracida-Alvarez, U.R.; Xu, H.; Benavides, P.T.; Wang, M.; Hawkins, T.R. Circular Economy Sustainability Analysis Framework for Plastics: Application for Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) (PET). ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilán, H. Nanomaterials and Their Synthesis for a Sustainable Future. In New Materials for a Circular Economy; Materials Research Forum LLC: Millersville, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 233–310. [Google Scholar]

- Mussinelli, E. Project Quality, Regulation Quality. TECHNE-J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2024, 27, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, R.A.; Obeso, J.L.; Vaidyula, R.R.; López-Cervantes, V.B.; Peralta, R.A.; Marín Rosas, P.; de los Reyes, J.A.; Mullins, C.B.; Ibarra, I.A. From Pollution to Energy Storage: Leveraging Hydrogen Sulfide with SU-101 Cathodes in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2024, 12, 32735–32744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachakis, G.; Malamis, D.; Mai, S.; Barampouti, E.M. Spatial Influence on Waste-to-Energy Sustainability: A Life Cycle Assessment of RDF Transport and Plant Siting. Energies 2025, 18, 6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubi, O.; Murphy, R.; Morse, S. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Waste to Energy Systems in the Developing World: A Review. Environments 2024, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakker, V.; Bakshi, B.R. Designing Value Chains of Plastic and Paper Carrier Bags for a Sustainable and Circular Economy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 16687–16698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes Barrera, G.A.; Gabarrell i Durany, X.; Rieradevall Pons, J.; Guerrero Erazo, J.G. Trends in Global Research on Industrial Parks: A Bibliometric Analysis from 1996–2019. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, C.Q.; Lora, E.E.S.; de Souza, L.L.P.; Leme, M.M.V.; Barros, R.M.; Venturini, O.J. Life Cycle Assessment of Methanol Production from Municipal Solid Waste: Environmental Comparison with Landfilling and Incineration. Resources 2025, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshiya, A.S.; Challa, M.S.; Majji, M.K.; Umme, K.; A., S.; Patibandla, J. ECO-Logic Reactions: Shaping the Future of Sustainable Molecular Science. World J. Curr. Med. Pharm. Res. 2025, 7, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, V.S. Green Chemistry Innovations an Advancing Sustainable Solutions for Environmental Challenges. Environ. Rep. 2022, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, L. Sustainable Side-Stream Management in Swedish Food Processing Companies Using External Actors and Biogas Solutions. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 1073663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Farrell, C.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Harrison, J.; Rooney, D.W. Pyrolysis Kinetic Modelling of Abundant Plastic Waste (PET) and in-Situ Emission Monitoring. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojceska, V.; Parker, N.; Tassou, S.A. Reducing GHG Emissions and Improving Cost Effectiveness via Energy Efficiency Enhancements: A Case Study in a Biscuit Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenara, N.; Gueret, R.; Huertas-Alonso, A.J.; Veettil, U.T.; Sipponen, M.H.; Lizundia, E. Lignin-Chitosan Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Stable Zn Electrodeposition. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 2283–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, E.P.; Gayialis, S.P.; Papadopoulos, G.A.; Papoutsis, G. An Ethereum-Based Distributed Application for Enhancing Food Supply Chain Traceability. Foods 2023, 12, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadhukhan, J.; Dugmore, T.I.J.; Matharu, A.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; Aburto, J.; Rahman, P.K.S.M.; Lynch, J. Perspectives on “Game Changer” Global Challenges for Sustainable 21st Century: Plant-Based Diet, Unavoidable Food Waste Biorefining, and Circular Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Raut, R.D.; Jagtap, S.; Choubey, V.K. Circular Economy Adoption Challenges in the Food Supply Chain for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1334–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutrizio, M.; Dukić, J.; Sabljak, I.; Samardžija, A.; Fučkar, V.B.; Djekić, I.; Jambrak, A.R. Upcycling of Food By-Products and Waste: Nonthermal Green Extractions and Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melas, L.; Batsioula, M.; Malamakis, A.; Patsios, S.I.; Geroliolios, D.; Alexandropoulos, E.; Skoutida, S.; Karkanias, C.; Dedousi, A.; Kritsa, M.Z.; et al. Circular Bioeconomy Practices in the Greek Pig Sector: The Environmental Performance of Bakery Meal as Pig Feed Ingredient. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, V. Life Cycle Assessment Model of Plastic Products: Comparing Environmental Impacts for Different Scenarios in the Production Stage. Polymers 2021, 13, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Güneş, S.; Vilela, A.; Gomes, R. Life-Cycle Assessment in Agri-Food Systems and the Wine Industry—A Circular Economy Perspective. Foods 2025, 14, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Mei, Q. Cost-Effective and Low-Carbon Scalable Recycling of Waste Polyethylene Terephthalate Through Bio-Based Guaiacol-Enhanced Methanolysis. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202503469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciambellotti, A.; Pasini, G.; Baccioli, A.; Ferrari, L.; Barsali, S. Absorption Chillers to Improve the Performance of Small-scale Biomethane Liquefaction Plants. Energies 2022, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, L.; Esnarrizaga, P.E.; Pracucci, A.; Zaffagnini, T.; Cortes, V.G.; Rudenå, A.; Brunklaus, B.; Larraz, J.A. Data-Driven and LCA-Based Framework for Environmental and Circular Assessment of Modular Curtain Walls. J. Facade Des. Eng. 2024, 12, 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, J.; Zambrana-Vásquez, D.; Del-Busto, F.; Círez, F. Social Impact Analysis of Products under a Holistic Approach: A Case Study in the Meat Product Supply Chain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecki, J.; Bojarowicz, E.; Bizon-Górecka, J.; Zaman, U.; Keleş, A.E. Leadership Models in Era of New Technological Challenges in Construction Projects. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachat, A.; Mantalovas, K.; Desbois, T.; Yazoghli-Marzouk, O.; Colas, A.S.; Di Mino, G.; Feraille, A. From Buildings’ End of Life to Aggregate Recycling under a Circular Economic Perspective: A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrucci, L.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. Boosting Circular Economy Solutions in the Construction Sector Using a Life Cycle Assessment. J. Ind. Ecol. 2025, 29, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, R.; Menegaldo, G.; Rocchi, L.; Paolotti, L.; Boggia, A.; Puglia, D. Olive Oil Wastewater Revalorization into a High-Added Value Product: A Biofertilizer Assessment Combining LCA and MCI. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, M.; Jucker, C.; Fusi, M.; Leonardi, M.G.; Daffonchio, D.; Borin, S.; Savoldelli, S.; Crotti, E. Hydrolytic Profile of the Culturable Gut Bacterial Community Associated with Hermetia Illucens. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latterini, F.; Stefanoni, W.; Suardi, A.; Alfano, V.; Bergonzoli, S.; Palmieri, N.; Pari, L. A GIS Approach to Locate a Small Size Biomass Plant Powered by Olive Pruning and to Estimate Supply Chain Costs. Energies 2020, 13, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández, B.N.; Escamilla-Alvarado, C.; Guadalupe Paredes, M.; Albalate-Ramírez, A.; Rodríguez-Valderrama, S.; Magnin, J.-P.; Rivas-García, P. Environmental Impact Assessment of Biohydrogen Production from Orange Peel Waste by Lab-Scale Dark and Photofermentation Processes. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2024, 40, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimaro, D.; Nyangarika, A.; Kivevele, T. Uncovering Socioeconomic Insights of Solar Dryers for Sustainable Agricultural Product Preservation: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalifa, M.; Özdemir, A.; Banar, M. Life Cycle Comparison of the Environmental and Economic Performance of an Informal Low-Capacity Passenger Transport System. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2024, 2678, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sanz-Garrido, C.; Revuelta-Aramburu, M.; Santos-Montes, A.M.; Morales-Polo, C. A Review on Anaerobic Digestate as a Biofertilizer: Characteristics, Production, and Environmental Impacts from a Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, G.; Stillitano, T.; Iofrida, N.; Spada, E.; Bernardi, B.; Gulisano, G.; De Luca, A.I. Life Cycle and Circularity Metrics to Measure the Sustainability of Closed-Loop Agri-Food Pathways. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1014228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, S.P.; Prabawani, B.; Qomariah, A. Circular Initiatives for Industrial Sustainability. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; Volume 317. [Google Scholar]

- Olazabal, I.; Goujon, N.; Mantione, D.; Alvarez-Tirado, M.; Jehanno, C.; Mecerreyes, D.; Sardon, H. From Plastic Waste to New Materials for Energy Storage. Polym. Chem. 2022, 13, 4222–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, K.; Halstead, J.; Small, R.; Young, I. Valorisation of Organicwaste By-Products Using Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia Illucens) as a Bio-Convertor. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.; Mascal, M.; Constant, S.; Claessen, T.; Tosi, P.; Mija, A. The Origin, Composition, and Applications of Industrial Humins—A Review. Green. Chem. 2025, 27, 3136–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassio, F.; Borda, I.E.P.; Talpo, E.; Savina, A.; Rovera, F.; Pieretto, O.; Zarri, D. Assessing Circular Economy Opportunities at the Food Supply Chain Level: The Case of Five Piedmont Product Chains. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Liang, L.; Xie, J.; Zhang, J. Environmental Effects of Technological Improvements in Polysilicon Photovoltaic Systems in China—A Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusaed, A.; Yitmen, I.; Myhren, J.A.; Almssad, A. Assessing the Impact of Recycled Building Materials on Environmental Sustainability and Energy Efficiency: A Comprehensive Framework for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Buildings 2024, 14, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]