A Study on the Site Selection of Offshore Photovoltaics in the Northwest Pacific Coastal Waters Based on GIS and Fuzzy-AHP

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

2.2. Data Sources and Preprocessing

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Assessment of Solar Power Generation Potential

2.3.2. Spatial Exclusion Analysis

2.3.3. FAHP Weight Determination and Comprehensive Suitability Evaluation

Basis for the Selection of Evaluation Indicators

- (1)

- Literature Review and Best Practices

- (2)

- Characteristics of the Northwest Pacific Region

Evaluation Criteria System

- (1)

- Power Generation Potential

- (2)

- Wave Conditions

- (3)

- Water Depth

- (4)

- Distance to Shore

- (5)

- Distance to Marine Protected Areas

- (6)

- Distance to Ports

- (7)

- Distance to Airports

Determination of Criteria Weights Based on FAHP

3. Results

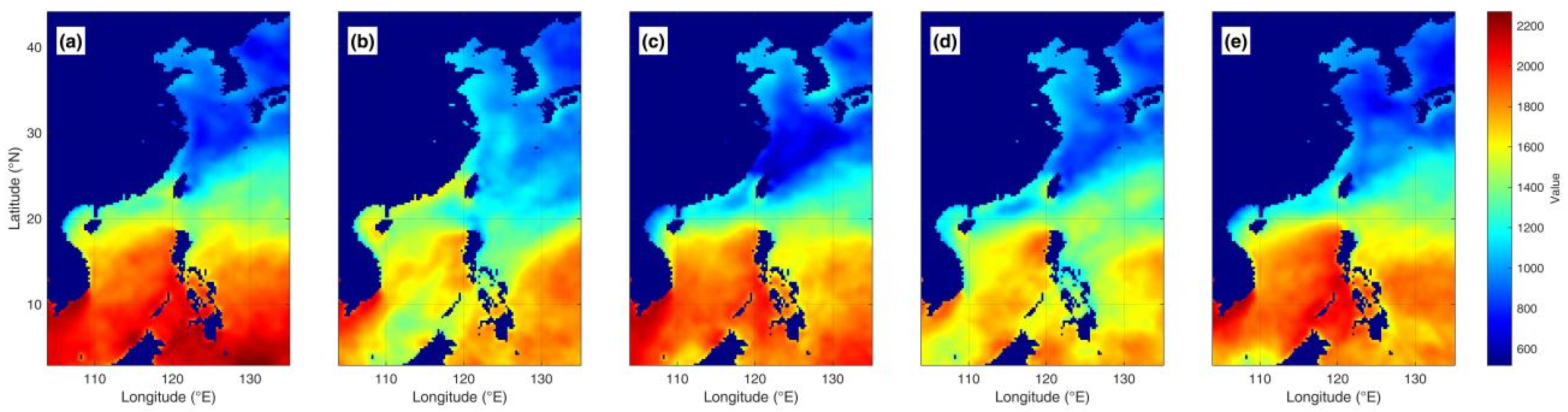

3.1. Distribution of Photovoltaic Power Generation Potential

3.2. Spatial Exclusion Results

3.3. Comprehensive Suitability Evaluation Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Patterns of Site Selection Results and Underlying Driving Mechanisms

4.2. Comparison with Existing Studies and Facilities, and Framework Validation

4.3. Robustness, Uncertainty, and Limitations of the Methodology

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| FAHP | Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| PV | photovoltaic |

| OFPVs | offshore photovoltaics |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

References

- Liu, J.; Ma, X.; Lu, C. A three-stage framework for optimal site selection of hybrid offshore wind-photovoltaic-wave-hydrogen energy system: A case study of China. Energy 2024, 313, 133723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Xu, C.; Zhou, J. A decision framework of offshore wind power station site selection using a PROMETHEE method under intuitionistic fuzzy environment: A case in China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 184, 105016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, J.; Jin, X.; Shi, J.; Chan, N.W.; Tan, M.L.; Lin, X.; Ma, X.; Lin, X.; Zheng, K.; et al. The Impact of Offshore Photovoltaic Utilization on Resources and Environment Using Spatial Information Technology. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Ma, Z.; Liu, T.; Zheng, C.; Wang, H. Innovations and development trends in offshore floating photovoltaic systems: A comprehensive review. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Lin, P. Offshore solar photovoltaic potential in the seas around China. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Gao, J.; Liu, H.; He, P. Locations appraisal framework for floating photovoltaic power plants based on relative-entropy measure and improved hesitant fuzzy linguistic dematel-promethee method. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 215, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Fan, J.; Lv, J.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, M. A decision framework of offshore photovoltaic power station site selection based on Pythagorean fuzzy Electre-III method. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2024, 16, 023502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Lozano, J.M.; Ramos-Escudero, A.; Gil-García, I.C.; García-Cascales, M.S.; Molina-García, A. A GIS-based offshore wind site selection model using fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making with application to the case of the Gulf of Maine. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 210, 118371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Gamal, A.; Chakrabortty, R.K.; Ryan, M. A new hybrid multi-criteria decision-making approach for location selection of sustainable offshore wind energy stations: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercan, E.; Tapkın, S.; Latinopoulos, D.; Dereli, M.A.; Tsiropoulos, A.; Ak, M.F. A GIS-based multi-criteria model for offshore wind energy power plants site selection in both sides of the Aegean Sea. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Etemad-Shahidi, A.; Stewart, R.A.; Sanjari, M.J.; Hayward, J.A.; Nicholson, R.C. Co-located offshore wind and floating solar farms: A systematic quantitative literature review of site selection criteria. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 50, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías-Paredes, L.; Gastón-Romeo, M. A new methodology to easy integrate complementarity criteria in the resource assessment process for hybrid power plants: Offshore wind and floating PV. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karipoğlu, F.; Ozturk, S.; Efe, B. A GIS-based FAHP and FEDAS analysis framework for suitable site selection of a hybrid offshore wind and solar power plant. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 77, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Nascimento, M.M.; Shadman, M.; Silva, C.; de Freitas Assad, L.P.; Estefen, S.F.; Landau, L. Offshore wind and solar complementarity in Brazil: A theoretical and technical potential assessment. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 270, 116194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L. Simplified method for predicting photovoltaic array output. Sol. Energy 1981, 27, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.B. Effect of Temperature and Wind Speed on Efficiency of PV Module. ResearchGate 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340226677_Effect_of_Temperature_and_Wind_Speed_on_Efficiency_of_PV_Module (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Charles Lawrence Kamuyu, W.; Lim, J.R.; Won, C.S.; Ahn, H.K. Prediction Model of Photovoltaic Module Temperature for Power Performance of Floating PVs. Energies 2018, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; An, T.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, R. Development and reform of marine spatial planning in China under the new territorial spatial planning system. Mar. Dev. 2024, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Asanza, S.; Quiros-Tortos, J.; Franco, J.F. Optimal site selection for photovoltaic power plants using a GIS-based multi-criteria decision making and spatial overlay with electric load. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panesar, A.; Sampson, O. Environmental impact of energy storage technologies and future renewable grids. J. Energy Storage 2026, 152, 120501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagiona, D.G.; Tzekakis, G.; Loukogeorgaki, E.; Karanikolas, N. Site Selection of Offshore Solar Farm Deployment in the Aegean Sea, Greece. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yao, L.; Zhou, C. Assessment of offshore wind-solar energy potentials and spatial layout optimization in mainland China. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H.; Yin, G.; Bao, Y.; Dong, Q.; Liu, Y. Site selection for hybrid offshore wind and wave power plants using a four-stage framework: A case study in Hainan, China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 218, 106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Pinto, S.; Stokkermans, J. Assessment of the potential of different floating solar technologies—Overview and analysis of different case studies. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 211, 112747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Kong, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Yao, Y. Lifetime and power generation evaluation of offshore floating photovoltaic systems considering wave motion and photovoltaic module degradation rates. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 526, 146659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, H. Experimental study on hydrodynamic performance and power generation efficiency of a moored dual-pontoon offshore floating photovoltaic system. Ocean Eng. 2025, 339, 122140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Lozano, J.M.; Henggeler Antunes, C.; García-Cascales, M.S.; Dias, L.C. GIS-based photovoltaic solar farms site selection using ELECTRE-TRI: Evaluating the case for Torre Pacheco, Murcia, Southeast of Spain. Renew. Energy 2014, 66, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Z. Analysis of hydroelastic response and failure mechanisms of floating offshore photovoltaic under wind and wave. Ocean Eng. 2025, 328, 121028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Gao, J.; Liu, H.; He, P. A hybrid fuzzy investment assessment framework for offshore wind-photovoltaic-hydrogen storage project. J. Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacul, L.-A.; Ferrancullo, D.; Gallano, R.; Fadriquela, K.-J.; Mendez, K.-J.; Morada, J.-R.; Morgado, J.-K.; Gacu, J. GIS-Based Identification of Flood Risk Zone in a Rural Municipality Using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP). Rev. Int. De Géomatique 2024, 33, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorollahi, Y.; Ghenaatpisheh Senani, A.; Fadaei, A.; Simaee, M.; Moltames, R. A framework for GIS-based site selection and technical potential evaluation of PV solar farm using Fuzzy-Boolean logic and AHP multi-criteria decision-making approach. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwi Putra, M.S.; Andryana, S.; Fauziah; Gunaryati, A. Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process Method to Determine the Quality of Gemstones. Adv. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 2018, 9094380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, M.; Lian, J.; Yao, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Xue, R. A framework to identify guano on photovoltaic modules in offshore floating photovoltaic power plants. Sol. Energy 2024, 274, 112598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, R.W. The analytic hierarchy process—What it is and how it is used. Math. Model. 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, B.; Workineh, T. Site Suitability Analysis of Solar PV Power Generation in South Gondar, Amhara Region. J. Energy 2020, 2020, 3519257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, D.; Yahaya, I.I.; Pan, H. Assessment of site suitability for centralized photovoltaic power stations in Northwest China’s six provinces. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyridonidou, S.; Vagiona, D.G. A systematic review of site-selection procedures of PV and CSP technologies. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 2947–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanka Vasuki, S.; Levell, J.; Santbergen, R.; Isabella, O. A technical review on the energy yield estimation of offshore floating photovoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 216, 115596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezarat, H.; Sereshki, F.; Ataei, M. Ranking of geological risks in mechanized tunneling by using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP). Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 50, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Category | Specific Parameters | Data Source | Original Resolution (Spatial/Temporal) | Application in This Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource data | Total solar radiation, Wind speed (10 m), Sea surface temperature (SST) | ERA5 reanalysis dataset (ECMWF) [14] | 0.25° × 0.25°, Hourly | Stage 1: Calculating solar power generation potential. |

| Exclusion criteria | Water depth (Bathymetry) | GEBCO | 15 arc-seconds (~500 m) | Stage 2 (exclusion): Exclude areas with depth < 10 m and >50 m. |

| Exclusion criteria | Marine protected areas (MPAs) | European Environment Agency | Vector polygons | Stage 2: Exclude areas <1 km from MPAs. |

| Exclusion criteria | Active faults | National Earthquake Data Center | Vector lines | Stage 2: Exclude areas <2 km from active faults. |

| Exclusion criteria | Offshore oil and gas platforms | Global Energy Monitor | Vector points | Stage 2: Exclude areas <0.5 km from platforms. |

| Exclusion criteria | Airports | GitCode/open-source toolkit | Vector points | Stage 2: Exclude areas <15 km from airports. |

| Exclusion criteria | Major ports | OpenStreetMap (OSM)/Ministry of Transport data | Vector points | Stage 2: Exclude areas <3 km from ports. |

| Exclusion criteria | Coastline | GSHHG (NOAA) | Vector lines | Stage 2: Calculate distance to shore; exclude areas <10 km and >50 km. |

| Exclusion criteria | Power generation potential | Generated from Stage 1 resource data | 0.25° × 0.25° | Stage 3: Used as a continuous evaluation factor. |

| Exclusion criteria | Water depth | GEBCO | 15 arc-seconds (~500 m) | Stage 3: Used as a continuous evaluation factor. |

| Exclusion criteria | Wave parameters (Significant wave height) | ERA5 reanalysis dataset (ECMWF) [14] | 0.25° × 0.25° | Stage 3: Used as “wave conditions” factor. |

| Exclusion criteria | Distance to shore | Calculated via GIS Euclidean distance from coastline | Raster (derived) | Stage 3: Used as “Distance to shore” factor. |

| Exclusion criteria | Distance to ports | Calculated via GIS Euclidean distance from ports | Raster (derived) | Stage 3: Used as “distance to ports” factor. |

| Exclusion criteria | Distance to airports | Calculated via GIS Euclidean distance from airports | Raster (derived) | Stage 3: Used as “distance to airports” factor. |

| Exclusion criteria | Distance to MPAs | Calculated via GIS Euclidean distance from MPAs | Raster (derived) | Stage 3: Used as “distance to MPAs” factor. |

| Exclusion Criterion | Threshold (Buffer Range) | Basis for Determination |

|---|---|---|

| Marine protected areas | <1 km | Referring to the general environmental management practices in maritime engineering construction [21], a safety buffer zone is established to minimize the potential disturbance to the ecosystem of the protected area during installation and maintenance activities [3,22]. |

| Active faults | <2 km | The distance of 2 km is a general measure to avoid potential risks to fixed or floating structures from geological disasters (such as tsunamis or seafloor instability caused by earthquakes) [23,24]. |

| Oil and gas platforms | <0.5 km | The threshold of 0.5 km is to avoid conflicts with the operational areas of offshore oil and gas facilities (such as safety zones and helicopter landing areas), and it complies with the standard safety distances for offshore facilities [1,13]. |

| Major ports | <3 km | The threshold of 3 km is intended to avoid spatial conflicts with the busy shipping lanes in and out of ports, ensuring the safety of navigation and the normal operation of port activities. This distance refers to the typical range of port safety operation zones and high-density navigation areas [5,24]. |

| Airports | <15 km | Based on the regulations of the International Civil Aviation Organization and national airspace management provisions, large-scale reflection from photovoltaic systems may cause visual interference to pilots. The threshold of 15 km refers to the general safety distance recommendations for similar renewable energy projects (especially large-scale photovoltaic and solar thermal power stations) and complies with strict aviation safety standards [20]. |

| Water depth | <10 m or >50 m | The lower limit of 10 m is intended to avoid ecologically sensitive intertidal zones, seagrass beds, and coral reef areas; the upper limit of 50 m is based on the economic threshold of the anchoring systems and mooring technologies of mainstream floating photovoltaic platforms. Construction and maintenance costs will significantly increase beyond this depth [23,25]. |

| Distance to shore | <10 km or >50 km | The lower limit of 10 km is designed to reduce impacts on coastal scenery, fishing activities, and tourism. The upper limit of 50 km is based on an analysis of the balance between submarine cable transmission losses and costs [1,5,25]. |

| AHP Normal Scale | AHP Reciprocal Scale | Definition | FAHP TFN Scale | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Equal importance | (1, 1, 1) | Criteria are equally important. |

| 3 | 1/3 | Moderate importance | (2, 3, 4) | One criterion is slightly more important. |

| 5 | 1/5 | Strong importance | (4, 5, 6) | One criterion is strongly more important. |

| 7 | 1/7 | Very strong importance | (6, 7, 8) | One criterion is very strongly more important. |

| 9 | 1/9 | Extreme importance | (9, 9, 9) | One criterion is extremely more important. |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | 1/2, 1/4, 1/6, 1/8 | Intermediate values | (1,2,3); (3,4,5)… | Used to compromise between two judgments. |

| Criterion | Symbol | Final Weight | Rank | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power potential | C1 | 0.3498 | 1 | Core Driving Factor |

| Water depth | C2 | 0.1880 | 2 | Key Technical Factor |

| Distance to MPAs | C3 | 0.1430 | 3 | Compliance Factor |

| Distance to shore | C4 | 0.0853 | 4 | Cost-Sensitive Factor |

| Wave height | C5 | 0.0832 | 5 | Risk-Sensitive Factor |

| Distance to airports | C6 | 0.0782 | 6 | Safety Factor |

| Distance to ports | C7 | 0.0724 | 7 | Cost Factor |

| Criterion | Highly Suitable (90–100) | Suitable (80–90) | Moderately Suitable (70–80) | Low Suitability (60–70) | Unsuitable (<60) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance to shore (km) | 10–20 | 20–30 | 30–40 | 40–50 | <10, >50 |

| Waves (m) | 0–1 | 1–1.5 | 1.5–2 | 2–2.5 | >2.5 |

| Power potential (kwh/m2) | >350 | 300–350 | 250–300 | 200–250 | <200 |

| Distance to marine protected areas (km) | >15 | 10–15 | 5–10 | 1–5 | <1 |

| Distance to airports (km) | >30 | 25–30 | 20–25 | 15–20 | <15 |

| Distance to ports (km) | 20–35 | 15–20; 35–40 | 10–15; 40–45 | 3–10; 45–50 | <3, >50 |

| Water depth (m) | 10–20 | 20–30 | 30–40 | 40–50 | <10, >50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, Z.; Wang, Q.; Xie, B.; Lv, D.; Hu, K.; Zheng, K.; Wang, J.; Yue, X.; Chen, J. A Study on the Site Selection of Offshore Photovoltaics in the Northwest Pacific Coastal Waters Based on GIS and Fuzzy-AHP. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031300

Feng Z, Wang Q, Xie B, Lv D, Hu K, Zheng K, Wang J, Yue X, Chen J. A Study on the Site Selection of Offshore Photovoltaics in the Northwest Pacific Coastal Waters Based on GIS and Fuzzy-AHP. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031300

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Zhenzhou, Qi Wang, Bo Xie, Duian Lv, Kaixiang Hu, Kaixuan Zheng, Juan Wang, Xihe Yue, and Jijing Chen. 2026. "A Study on the Site Selection of Offshore Photovoltaics in the Northwest Pacific Coastal Waters Based on GIS and Fuzzy-AHP" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031300

APA StyleFeng, Z., Wang, Q., Xie, B., Lv, D., Hu, K., Zheng, K., Wang, J., Yue, X., & Chen, J. (2026). A Study on the Site Selection of Offshore Photovoltaics in the Northwest Pacific Coastal Waters Based on GIS and Fuzzy-AHP. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031300