Abstract

This paper presents a scalable and low-cost Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) architecture designed to enhance learning in university-level courses, with a particular focus on supporting students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated considerable potential in educational contexts; however, their adoption is often limited by computational costs and the need for stable broadband access, issues that disproportionately affect low-income learners. To address this challenge, we propose a lightweight, mobile, and friendly RAG system that integrates the LLaMA language model with the Milvus vector database, enabling efficient on device retrieval and context-grounded generation using only modest hardware resources. The system was implemented in a university-level Data Mining course and evaluated over four semesters using a quasi-experimental design with randomized assignment to experimental and control groups. Students in the experimental group had voluntary access to the RAG assistant, while the control group followed the same instructional schedule without exposure to the tool. The results show statistically significant improvements in academic performance for the experimental group, with p < 0.01 in the first semester and p < 0.001 in the subsequent three semesters. Effect sizes, measured using Hedges g to account for small cohort sizes, increased from 0.56 (moderate) to 1.52 (extremely large), demonstrating a clear and growing pedagogical impact over time. Qualitative feedback further indicates increased learner autonomy, confidence, and engagement. These findings highlight the potential of mobile RAG architectures to deliver equitable, high-quality AI support to students regardless of socioeconomic status. The proposed solution offers a practical engineering pathway for institutions seeking inclusive, scalable, and resource-efficient approaches to AI-enhanced education.

1. Introduction

Due to the rapid evolution of digital learning technologies, a persistent digital divide continues to affect students from low-income backgrounds, who often lack access to personal computers or stable broadband connectivity. UNESCO reports that socioeconomic disparities significantly limit students’ ability to benefit from digital educational resources, particularly in regions where household device ownership remains uneven [1]. Nevertheless, global mobile statistics indicate that over 75% of learners in low-resource contexts own or share access to a smartphone, making mobile-first educational solutions a viable and equitable strategy for reducing digital exclusion [2,3]. Designing a RAG-based learning assistant that is lightweight, low-cost, and optimized for mobile deployment therefore addresses an urgent need: enabling students with limited technological means to access AI-augmented academic support without requiring high-end hardware or continuous cloud access.

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) has opened new possibilities for enhancing teaching and learning processes in higher education [4]. Beyond automation and analytics, AI technologies are reshaping how students interact with educational content, promoting adaptive, personalized, and self-regulated learning experiences [5,6]. Among these emerging technologies, Retrieval Augmented Generation systems, which combine large language models with vector databases, have shown potential to bridge the gap between static instructional materials and dynamic, context-aware support for learners [7,8].

In traditional classroom settings, students often face challenges when attempting to connect lecture materials, practice exercises, and theoretical foundations. This difficulty is especially evident in technically complex courses, such as Data Mining in our case, where conceptual comprehension, programming, and algorithmic application must coexist. By integrating a RAG-based assistant capable of retrieving, contextualizing, and generating relevant information from lecture slides, study guides, and recorded sessions, it becomes possible to reinforce students’ ability to explore and internalize course knowledge more effectively [9,10].

Recent advances in LLM architectures, such as LLaMA and GPT-based models, coupled with open source vector databases like Milvus, have facilitated the practical deployment of RAG systems in educational environments [11,12]. Such systems retrieve semantically relevant course segments and synthesize explanations contextualized to the specific academic content, offering individualized learning support and increasing accessibility [10,13].

This work presents the implementation and evaluation of an AI-augmented pedagogical system designed to support learning in a university-level Data Mining course. The proposed system integrates the LLaMA large language model with Milvus, an open-source vector database, to create a RAG architecture tailored to course-specific instructional content. Over four academic semesters, the system was deployed for an experimental student group, while a control group continued using traditional materials under identical instructional conditions.

Results demonstrated a consistent and statistically significant improvement in the academic performance of students who voluntarily engaged with the RAG system, suggesting that sustained exposure to AI-enhanced environments contributes to deeper conceptual mastery [14,15,16,17].

From an applied engineering perspective, this study focuses on the design, deployment, and validation of a mobile-first Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) architecture under real-world resource constraints. Rather than proposing new learning algorithms, the contribution lies in demonstrating how existing AI components can be systematically integrated into a low-cost, scalable system that is feasible to deploy in higher-education environments with limited computational infrastructure.

This study makes three main contributions. First, it proposes a reusable, scalable, and low-cost mobile Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) architecture and deployment pattern, specifically designed for higher-education contexts with limited computational and economic resources. Second, it reports a longitudinal, four-semester quasi-experimental evaluation of the system in a university-level Data Mining course, providing empirical evidence of its pedagogical effectiveness over time. Third, it analyzes how sustained voluntary interaction with a context-grounded AI assistant influences academic performance, learner autonomy, and engagement under identical instructional conditions.

Based on these contributions, the study addresses the following research questions: (RQ1) Does sustained access to a mobile RAG-based learning assistant lead to statistically significant improvements in academic performance compared to traditional instruction alone? (RQ2) How does prolonged exposure to a context-grounded AI assistant affect the magnitude of learning gains over multiple semesters? (RQ3) Can a low-cost, mobile-first RAG architecture provide effective and equitable AI-augmented learning support without altering instructional design or assessment practices?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides the theoretical background on RAG systems and discusses related studies; Section 3 details the research methodology, including system architecture and experimental design; Section 4 presents and interprets the empirical findings; Section 5 discusses the results and their pedagogical implications; and Section 6 concludes with pedagogical implications and recommendations for future research.

2. Background

2.1. The Emergence of Retrieval-Augmented Generation

Recent progress in LLMs has enabled remarkable natural-language reasoning and generative capabilities; however, these models still exhibit factual inaccuracies and limited domain adaptability. RAG has emerged as a hybrid paradigm that combines information retrieval with generative modeling to address these limitations [7,18].

In RAG architectures, a user’s query is converted into an embedding vector, which is matched against a pre-indexed corpus stored in a vector database. The retrieved segments are concatenated with the prompt before being processed by the LLM, producing a grounded response that leverages both parametric and external knowledge [8]. This mechanism has gained attention across domains such as biomedical question answering, customer support, and education, due to its ability to deliver context-aware and content-validated explanations [10].

2.2. Vector Databases and Semantic Retrieval

Unlike traditional keyword search systems, vector databases store dense numerical representations of documents that capture semantic similarity rather than lexical overlap. This property allows a RAG system to retrieve conceptually related materials even when phrased differently by learners [12]. Modern solutions such as Milvus [11] and Weaviate support high-dimensional approximate nearest-neighbour search, scalable indexing, and metadata filtering, all crucial for educational deployments requiring low latency and continual updates. The choice of vector database and embedding model strongly influences retrieval accuracy, which in turn affects the pedagogical value of generated responses [15]. Empirical research has confirmed that semantic retrieval combined with course-specific corpora enhances both factual precision and student trust in AI explanations [17,19].

2.3. Applications of RAG in Education

Within educational contexts, RAG systems are being explored as intelligent tutors, automated feedback agents, and personalized study companions [20]. A recent systematic review in Computers & Education concluded that retrieval-augmented LLMs improved factual accuracy and contextual relevance of feedback in higher-education settings [8]. In [17] demonstrated that combining in-context learning with retrieval augmentation yielded higher-quality automatically generated questions aligned with curriculum objectives. Other works, such as TutorLLM [10], highlight how integrating RAG with knowledge-tracing algorithms allows the generation of adaptive learning recommendations based on individual student histories. For technically demanding subjects like Data Mining, such systems can alleviate the cognitive burden of connecting theoretical concepts, programming, and algorithmic applications. According to [21] enabling students to query lecture slides, practical guides, and recorded sessions through a RAG interface, instructors extend the learning process beyond scheduled class time, supporting self-regulated and inquiry-based learning.

Although RAG systems show promise, their adoption is often constrained by socioeconomic and technological disparities among students. UNESCO reports that learners from low-income households frequently lack access to personal computers or reliable broadband, limiting their ability to use conventional digital learning tools [22]. However, global analyses by the GSMA and Pew Research Center indicate that smartphone ownership is significantly higher than computer ownership, even in underserved populations, with mobile devices serving as the primary internet access point for millions of students worldwide [2,3]. These findings underscore the necessity of designing RAG systems that are lightweight, mobile-compatible, and low-cost, ensuring equitable access to AI-augmented learning support regardless of economic background.

2.4. Pedagogical Implications

The introduction of RAG into instructional practice represents a shift toward AI-augmented pedagogy, where human teaching is complemented (rather than replaced) by intelligent digital scaffolds [14,23]. In this paradigm, the instructor remains the epistemic authority, while the RAG system facilitates exploration, reflection, and immediate clarification. This aligns closely with constructivist and connectivist learning theories that emphasize active engagement and personalized meaning-making [24]. The integration of RAG also enhances feedback immediacy, a factor strongly correlated with learning retention and motivation [9]. When students receive contextualized responses directly drawn from validated instructional resources, their confidence in self-study improves, contributing to a cycle of reinforcement and deeper understanding [25].

2.5. Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Due these benefits, there are open challenges. Retrieval accuracy depends heavily on corpus quality; poorly chunked or outdated materials can produce misleading responses. Moreover, while RAG reduces hallucination frequency, LLMs may still generate plausible yet incorrect information [26]. Maintaining transparency, updating content regularly, and establishing institutional policies for AI use are critical to ensuring trustworthiness in educational applications [27].

Ethical issues such as intellectual property rights over indexed materials and the preservation of student privacy during interaction logging must also be addressed [28]. Ensuring that AI systems operate within institutional and legal boundaries is essential for their adoption in higher education.

2.6. Relevance to the Present Study

The present research builds on this growing body of work by evaluating a RAG-based assistant specifically designed for a university-level Data Mining course. By combining Milvus for semantic retrieval and LLaMA for generative synthesis, the system indexes authentic instructional content—slides, practice guides, and recorded lectures—to deliver targeted, contextually grounded feedback. The experimental results, analyzed over four semesters, provide empirical evidence of how sustained exposure to AI-augmented learning environments can strengthen academic performance, complementing existing literature that has so far been largely exploratory or short-term in scope [7,8,21].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Objectives

This research employed a quasi-experimental longitudinal design to evaluate the pedagogical effect of a RAG system in higher education. The primary objective was to determine whether sustained exposure to an AI-augmented learning assistant improves academic performance and conceptual understanding in a Data Mining course.

Two student groups were compared across four consecutive semesters:

- Experimental group: students who had voluntary access to the RAG-based assistant.

- Control group: students following the same curriculum and instructor but unaware of the RAG system.

Random assignment was conducted at the individual student level during course enrollment. Students registered in parallel sections of the same course, which were randomly designated as experimental or control prior to the beginning of the semester.

It is important to note that no additional or modified lessons were prepared for the experimental group. Both experimental and control groups followed the same syllabus, instructional materials, lesson plans, and assessment instruments, delivered by the same instructor. The RAG-based assistant was offered exclusively as an optional supplementary tool to the experimental group, without any changes to instructional strategies, learning objectives, or evaluation criteria.

Groups were randomly formed at enrollment to ensure comparable baseline abilities. The instructor, learning materials, and assessment methods were identical, isolating the RAG assistant as the only differentiating variable.

3.2. System Architecture Overview

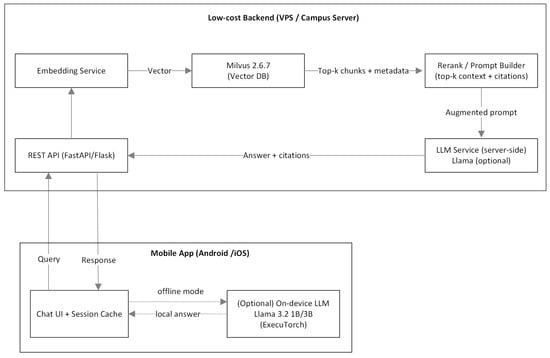

The proposed RAG-based assistant was designed to prioritize low-cost deployment and mobile accessibility. As illustrated in Figure 1, the system follows a modular open-source architecture that decouples user interaction, retrieval, and generation into lightweight and scalable components. The architecture is organized around two primary layers:

- Mobile Application Layer: This layer provides the user interface through which students interact with the system using their smartphones. The mobile application handles query submission, session management, and response visualization. Depending on device capabilities and connectivity conditions, the generative component based on the LLaMA (Meta Platforms, Menlo Park, CA, USA) large language model may execute either locally on the device (via optimized and quantized inference) or remotely through the backend services. This design enables flexible deployment across heterogeneous mobile hardware while maintaining low computational overhead.

- Low-Cost Backend Layer: This layer hosts the retrieval and orchestration services. Course materials, including lecture slides, study guides, and transcripts of recorded sessions, are preprocessed, embedded, and indexed in Milvus (Zilliz, San Mateo, CA, USA), an open-source vector database that supports high-dimensional semantic search and efficient approximate nearest-neighbor retrieval. Upon receiving a student query, the backend computes the corresponding embedding, retrieves the most relevant content segments from Milvus, and constructs an augmented prompt that is subsequently passed to the generative model. This separation of concerns allows the system to scale efficiently while keeping infrastructure costs minimal.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the RAG-based learning assistant.

By transferring vector storage and retrieval operations to a centralized backend while enabling mobile-friendly interaction and optional on-device inference, the proposed architecture achieves a balanced trade-off between performance, accessibility, and cost. This design is particularly suitable for educational contexts with limited computational resources, where students primarily rely on smartphones as their main access point to digital learning environments.

Design choices were guided by low-cost deployment and mobile accessibility constraints. LLaMA 3.2 (1B/3B) was selected because it supports efficient quantized inference and can be deployed either on-device for lightweight requests or on a low-cost backend for more demanding queries. Milvus was chosen as an open-source vector database with strong community support and efficient approximate nearest-neighbor retrieval at scale. HNSW indexing was used due to its favorable latency–accuracy trade-off for semantic search under limited compute resources. Instructional materials were chunked into 512-token segments to balance retrieval granularity, context relevance, and prompt length constraints. Finally, the hybrid inference strategy enables robust user experience across heterogeneous mobile devices and connectivity conditions while minimizing infrastructure cost.

To support reproducibility and clarify deployment constraints, Table 1 summarizes model versions, inference mode, embedding configuration, and representative minimum hardware assumptions (mid-range mobile devices and a low-cost backend that can operate in CPU-only mode).

Table 1.

RAG System Implementation Parameters.

Table 1 summarizes the main technical parameters of the proposed RAG system, including model versions, embedding dimensionality, inference mode, and representative hardware configurations, to facilitate reproducibility.

3.3. RAG System Workflow and Processing Pipeline

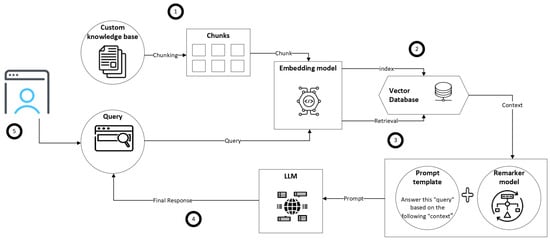

The proposed RAG system follows a structured processing pipeline composed of five sequential stages (Figure 2), designed to ensure efficient retrieval, contextual grounding, and low computational overhead. This modular workflow supports scalability and facilitates deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Figure 2.

RAG System workflow.

- Preprocessing and Indexing: Instructional materials (including lecture slides, practice guides, and transcripts of recorded sessions) were segmented into fixed-length chunks of 512 tokens. Each segment was transformed into a dense vector representation using Sentence-Transformers. To support traceability and contextual filtering, metadata such as topic, session date, and source document were associated with each chunk.

- Vector Storage: The resulting embeddings were indexed in Milvus using Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) graphs, enabling efficient approximate nearest-neighbor search over high-dimensional vector spaces. This indexing strategy provides a favorable trade-off between retrieval accuracy and latency, which is critical for real-time educational interactions.

- Retrieval Phase: When a student submits a query through the mobile application, the query is embedded using the same encoder and compared against the indexed vectors stored in Milvus. The system retrieves the top-k most semantically similar content segments, ensuring that subsequent generation is grounded in course-specific and instructor-validated materials.

- Augmentation and Generation: The retrieved content segments are concatenated with the original user query to form an augmented prompt. This prompt is then passed to the LLaMA large language model, which generates a response conditioned on both the query and the retrieved context. This retrieval augmented approach reduces hallucination and improves alignment with the instructional corpus.

- Interface Layer: The generated response is returned to the user through a lightweight web interface implemented using Flask and Streamlit. The interface provides a chat-style interaction within the existing learning platform, supporting session continuity and facilitating seamless integration into the students’ regular study workflow.

3.4. Data Collection and Implementation Phases

The system was deployed across four academic semesters. Data collected included:

- Usage metrics: number of accesses per student, average queries, and session duration.

- Academic performance: normalized grades on a 0–1 scale from assignments and exams.

- Qualitative feedback: voluntary student comments regarding perceived usefulness and ease of use.

Access to the RAG application was restricted to students in the experimental group; however, its use was entirely voluntary, allowing participants to decide whether and how frequently to engage with the system without any academic obligation or penalty.

System logs indicated progressive adoption, with mean usage increasing from 11.7 to 32.8 accesses per student between the first and fourth semesters.

The reported usage metrics (number of accesses, average queries, and session duration) are presented as descriptive indicators of system adoption and engagement trends. These variables were not used as predictive or ranked indicators of learning outcomes, as higher usage or longer sessions do not necessarily imply deeper understanding or better performance.

3.5. Experimental Procedure

To ensure validity and reliability:

- The same instructor conducted all sessions across semesters.

- Identical assessments (projects, exams, rubrics) were used for both groups.

- No communication occurred between experimental and control cohorts.

At the end of each semester, grades were normalized and analyzed using an independent-samples t-test to evaluate mean differences between groups. Since grade distributions were approximately normal with slight left skewness, this test was appropriate. Additionally, Hedges g was calculated to measure effect size, which provides a bias-corrected estimate suitable for small sample sizes. Given the relatively small cohort sizes in each semester, Hedges g was selected over Cohen’s d to reduce bias in the estimation of effect magnitude.

Simulated data approximation was used solely to reconstruct group-level distributions consistent with observed means, standard deviations, and sample sizes. This approach preserves the validity of group-level statistical tests and effect size estimation (Hedges g), but precludes individual-level analyses.

Across the four semesters, statistically significant improvements were observed for the experimental group, with in the first semester and in the subsequent three semesters. Hedges g increased from 0.56 (moderate) in the first semester to 1.52 (extremely large) in the final semester, indicating a steadily growing magnitude of improvement over time. This corrected effect size measure is appropriate for small cohorts and provides a more accurate estimate of the true educational impact of the RAG system.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

All procedures complied with institutional ethics guidelines. Participation in system use was optional, and data were analyzed in aggregated form only. The indexed corpus included exclusively instructor-generated content, ensuring adherence to copyright and privacy regulations.

3.7. Methodological Limitations

While rigorous, the methodology has limitations:

- Uneven engagement: Not all experimental students interacted equally with the RAG system; higher users tended to exhibit stronger gains.

- Because access to the RAG system was voluntary, a potential self-selection bias cannot be excluded, as more motivated or higher-performing students may have engaged more frequently with the tool. Usage metrics were available only in aggregated form, preventing individual-level correlation or regression analyses between system use and academic performance.

- Due to data protection constraints, individual baseline variables such as prior GPA, programming experience, or demographic characteristics were not available for statistical comparison; this limitation is acknowledged in the interpretation of internal validity.

- Simulated data approximation: The lack of individual-grade access introduces small estimation uncertainties.

- Scope restriction: The study focuses on a single technical course; broader disciplinary replication is needed.

- A further limitation is that engagement metrics were analyzed in aggregated form only, preventing inferential modeling or multi-criteria ranking of usage indicators (e.g., access frequency versus session duration). Future work may explore such analyses using anonymized individual-level data, subject to ethical and legal approval.

In addition, the present study should be interpreted in light of related research on retrieval-augmented generation and AI-assisted learning systems. Prior studies have explored the use of RAG architectures as intelligent tutors or feedback agents in educational settings, often focusing on short-term evaluations, specific learning tasks, or simulated environments [8,9,15,17]. While the proposed mobile-first RAG architecture extends this line of work through longitudinal deployment and real-world validation, direct comparative analyses with alternative RAG designs, model configurations, or instructional contexts were beyond the scope of this study. Future research should therefore examine the generalizability of these findings across disciplines, compare different retrieval and generation strategies, and assess how system-level design choices interact with pedagogical variables in diverse educational environments.

Nevertheless, the controlled design, four-semester span, and consistent statistical outcomes collectively strengthen confidence in the pedagogical effectiveness of the RAG system.

4. Results

4.1. Overview of the Analysis

The evaluation of the RAG-based assistant focused on identifying significant differences in student performance between the experimental group (with access to the RAG system) and the control group (traditional learning only). Across four academic semesters, the same instructor and assessment framework were maintained to ensure pedagogical consistency.

In this study, we distinguish between system-level validation and pedagogical outcomes. System validation focuses on sustained adoption, robustness, and usage trends of the RAG architecture, while learning outcomes are evaluated separately through academic performance metrics and effect size analysis.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics, t-tests for mean comparisons, and calculation of Hedges g to estimate effect size.

4.2. Descriptive Results

Table 2 summarizes the average normalized grades and standard deviations for both groups across the four semesters.

Table 2.

Comparison of Control and Experimental Groups by Semester Using Hedges g.

The results show a clear upward trend in both mean scores and effect sizes. The progressive increase in Hedges g from (moderate) in the first semester to (extremely large) in the final semester indicates that prolonged exposure to the RAG assistant led to cumulative cognitive gains over time. Because Hedges g provides a bias-corrected estimate appropriate for small cohorts, these findings offer strong evidence that sustained interaction with the system meaningfully enhanced students’ learning outcomes, consistent with theories of self-regulated and inquiry-based learning supported by intelligent tutoring systems.

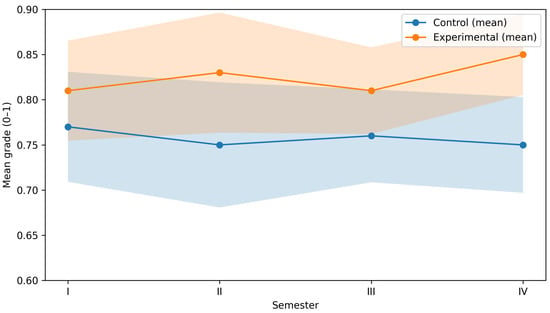

4.3. Statistical Significance and Learning Gains

Figure 3 illustrates the mean grade progression for both groups. The experimental group consistently outperformed the control group across all four semesters. The improvement was statistically significant in every semester, with p < in the first semester and p < in the subsequent three semesters. This confirms that interaction with the RAG assistant had a measurable positive effect on student achievement.

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean grades between control and experimental groups over four semesters. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals of the mean computed using the Student’s t distribution (small cohorts).

The largest improvements were observed from Semester IV onward, which coincides with increased student familiarity and engagement with the tool. This trend aligns with the “learning curve” effect, where repeated exposure to adaptive learning technologies enhances knowledge retention and transfer [25].

4.4. Usage Patterns and Engagement

To better understand the relationship between RAG system usage and academic improvement, system log data were analyzed. Figure 4 depicts the average number of interactions per student across semesters.

Figure 4.

Average number of RAG interactions per student.

Usage metrics are reported to characterize system adoption and engagement behavior over time and are not intended to serve as direct predictors of academic performance. This distinction ensures a clear separation between system robustness and pedagogical effectiveness.

Increased usage corresponded with higher performance, reinforcing the hypothesis that active engagement with AI-supported resources fosters deeper learning. This finding echoes prior research indicating that retrieval-based and feedback-oriented systems enhance conceptual retention and motivation [9,29].

4.5. Qualitative Findings

Open-ended student feedback provided additional insights:

- Students reported greater confidence in tackling algorithmic problems independently.

- The contextual responses helped them connect theoretical concepts with practical exercises and programming.

- Many described the system as “a second instructor always available”, highlighting perceived accessibility benefits.

These qualitative trends underscore the system’s role not only as an informational tool but also as a cognitive scaffold, enhancing autonomy and reducing dependence on synchronous instructor support.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study carry important implications for addressing the digital divide in higher education. Students from low-income households often lack personal computers or stable broadband access, limiting their ability to benefit from existing AI-powered learning tools. However, global data from UNESCO, GSMA, and the Pew Research Center indicate that smartphone ownership is significantly more widespread than computer ownership among economically disadvantaged learners, making mobile devices the primary gateway to digital learning for millions of students. By designing a lightweight RAG architecture capable of running efficiently on mobile devices, this work offers a practical and inclusive engineering response to these structural inequities. The system’s ability to provide high-quality, curriculum-aligned support without requiring high-end hardware demonstrates how AI-based educational technologies can be reimagined to promote fairness, broaden access, and empower students who are traditionally underserved by conventional digital infrastructures.

The quantitative and qualitative results converge on a consistent conclusion: RAG-based systems can substantially improve academic performance and engagement when integrated responsibly into formal instruction.

The use of Hedges g provides a more accurate estimate of effect size for small cohorts, strengthening the validity of the observed longitudinal gains.

Unlike generic LLM chatbots, the system evaluated here provided course-specific, context-grounded responses using verified instructional content indexed through Milvus, which increased trust and learning reliability.

The progressive improvement across semesters supports the argument that sustained exposure to AI-augmented environments cultivates self-regulation and metacognitive growth. These findings align with previous literature demonstrating that retrieval-based learning aids, when embedded in authentic educational contexts, can produce long-term positive learning outcomes [9,29].

However, the success of such implementations depends heavily on instructor oversight, high-quality content curation, and ongoing evaluation of AI-generated explanations to prevent conceptual drift or misinformation. Addressing these elements is essential for maintaining academic integrity in AI-supported education.

6. Conclusions

This study evaluated a scalable and low-cost RAG architecture designed to support students in an engineering course, with particular attention to learners from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. Across four semesters, students who used the mobile-compatible RAG assistant consistently achieved higher academic performance than those in the control group. Statistically significant improvements were observed in every semester, with p < in the first semester and p < in the subsequent three semesters. Effect sizes, measured using Hedges g, increased from moderate to extremely large, indicating a growing educational impact over time.

From an applied engineering perspective, the main contribution of this work is the validation of a low-cost, mobile-first RAG architecture and deployment pattern that can operate under constrained infrastructure while maintaining responsive retrieval and context-grounded generation. The system-level design decisions, open-source stack, and minimal backend requirements demonstrate real-world feasibility for institutions seeking scalable AI assistance without high-end hardware or proprietary APIs.

These results confirm that sustained exposure to a context-grounded, AI-assisted learning environment can enhance conceptual understanding, strengthen self-regulated learning, and improve overall academic outcomes.

The mobile-first design of the proposed RAG system represents a relevant engineering contribution for institutions seeking equitable access to advanced educational technologies. By reducing computational demands and enabling on-device execution, the system overcomes key barriers associated with traditional AI-based tools that rely on high-performance hardware or costly cloud infrastructures. In doing so, it broadens participation in AI-enhanced learning and supports students who are disproportionately affected by the digital divide.

In addition, our study evaluated the pedagogical effectiveness of a RAG system in higher education through a four-semester quasi-experimental design. The system, which integrated the LLaMA large language model with the Milvus vector database, was applied to a university-level Data Mining course and compared against a control group under identical instructional conditions.

These findings provide empirical evidence that sustained exposure to AI-augmented learning environments enhances conceptual understanding, engagement, and learner autonomy. Such improvements are consistent with recent studies showing that retrieval-based educational systems can reduce cognitive load, promote self-regulated learning, and increase factual accuracy [7,9].

From a pedagogical perspective, this work illustrates that RAG systems can act as scalable cognitive scaffolds, extending instructional presence beyond classroom hours while maintaining epistemic alignment with validated materials. By grounding the model’s generative reasoning in the instructor’s own content, the system preserved academic integrity and avoided the unreliable behavior observed in generic conversational AI models.

Nevertheless, successful implementation of RAG in formal education requires institutional commitment to quality assurance, ethical oversight, and instructor participation. Content must be periodically updated, retrieval pipelines audited for relevance, and student interaction monitored to ensure responsible use. Ethical considerations related to data privacy and intellectual property also remain essential in the deployment of AI-driven tools in higher education [30].

Future Work

Future research should address three main directions:

- Cross-disciplinary validation: applying the system to humanities, social sciences, and engineering courses to evaluate generalizability.

- Adaptive personalization: integrating analytics to dynamically adjust retrieval granularity and feedback depth based on student progress.

- Explainability and trust: developing transparent mechanisms that help students understand why certain answers were retrieved and generated, thus improving trust and accountability.

By combining RAG architectures with pedagogical theory, this research contributes to the foundation of AI-augmented pedagogy, an emerging paradigm where retrieval, reasoning, and human instruction coexist to create adaptive, equitable, and context-aware learning experiences for the next generation of university students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.; methodology, R.B. and F.M.; software, A.P. and P.M.; validation, R.B., F.M., A.P. and P.M.; formal analysis, R.B.; investigation, R.B., A.P. and P.M.; data curation, R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.; writing—review and editing, R.B., A.P. and P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study in accordance with the Ecuadorian Organic Law on Personal Data Protection (Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos Personales, Ecuador). The applicable legal provisions allow the processing of personal data for scientific and academic research purposes when the data are anonymized, non-sensitive, analyzed in aggregated form, and when such processing poses no risk to the rights and freedoms of the data subjects. The study involved non-interventional educational practices, voluntary participation, and did not process any personally identifiable or sensitive data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to legal and ethical restrictions related to data protection regulations, as the study involves anonymized educational data analyzed in aggregated form.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RAG | Retrieval Augmented Generation |

| LLM | Large Language Models |

| HNSW | Hierarchical Navigable Small World |

References

- UNESCO. 2023 Global Education Monitoring Report: Technology in Education—A Tool on Whose Terms? 2023. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000385723 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Pew Research Center. Internet, Smartphone and Social Media Use in Advanced Economies 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2022/12/06/internet-smartphone-and-social-media-use-in-advanced-economies-2022/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- GSMA. Mobile Momentum: 5G Connections to Surpass 1 Billion in 2022, Says GSMA. Press Release. 2 March 2022. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/newsroom/press-%release/mobile-momentum-5g-connections-to-surpass-1-billion-in-2022-says-gsma/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Bobadilla, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; Patricio Guisado, M.Á.; Bojorque, R.X. Analysis of scientific production based on trending research topics. An Artificial Intelligence case study. Rev. Española Doc. Científica 2019, 42, e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, F.; Khan, M.N.; Tahir, M.; Addas, A.; Aejaz, S.H. Integrating deep learning techniques for personalized learning pathways in higher education. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Marín, V.I.; Bond, M.; Gouverneur, F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—Where are the educators? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, H. Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.10997. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Hung, K.; Xie, H.; Wang, F.L. Retrieval-augmented generation for educational application: A systematic survey. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swacha, J.; Gracel, M. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Chatbots for Education: A Survey of Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Gu, W.; Yazdanpanah, V.; Shi, L.; Cristea, A.I.; Kiden, S.; Stein, S. TutorLLM: Customizing learning recommendations with knowledge tracing and retrieval-augmented generation. In Proceedings of the IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 8 September 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yi, X.; Guo, R.; Jin, H.; Xu, P.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Guo, X.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; et al. Milvus: A Purpose-Built Vector Data Management System. In Proceedings of the SIGMOD ’21, 2021 International Conference on Management of Data, Virtual, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 2614–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipalus, T. Vector database management systems: Fundamental concepts, use-cases, and current challenges. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2024, 85, 101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Luo, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Yu, S.; Zhang, B.; Cao, J.; Ma, J.; et al. A survey on knowledge-oriented retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.10677. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh Iyer, S. AI-Augmented Pedagogy: Rethinking Teaching and Learning in the Age of Technology. 2024. Available online: https://plu.mx/plum/a/?ssrn_id=5180833 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Lang, G.; Gürpinar, T. AI-Powered Learning Support: A Study of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Chatbot Effectiveness in an Online Course. Inf. Syst. Educ. J. 2025, 23, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusilovsky, P. AI in Education, Learner Control, and Human-AI Collaboration. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 34, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Deroy, A.; Sarkar, S. Leveraging In-Context Learning and Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Automatic Question Generation in Educational Domains. In Proceedings of the FIRE ’24, 16th Annual Meeting of the Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation, Gandhinagar, India, 12–15 December 2025; pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ranjan, R.; Singh, S.N. A comprehensive survey of retrieval-augmented generation (rag): Evolution, current landscape and future directions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.12837. [Google Scholar]

- Ghali, M.K.; Farrag, A.; Won, D.; Jin, Y. Enhancing knowledge retrieval with in-context learning and semantic search through generative AI. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 311, 113047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Li, D. Understanding EFL students’ use of self-made AI chatbots as personalized writing assistance tools: A mixed methods study. System 2024, 124, 103362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. Intelligent Tutoring System Algorithm: Enhance Personalized Learning Experience. In Frontier Computing: Vol 1; Hung, J.C., Yen, N., Chang, J.W., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 431–439. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Surgen Alarmantes Brechas Digitales en el Aprendizaje a Distancia [Surging Alarming Digital Divides in Distance Learning]. Press Release. 21 April 2020. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/es/articles/surgen-alarmantes-brechas-digitales-en-el-aprendizaje-distancia (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Liu, X.; Zhong, B. Integrating generative Artificial Intelligence into student learning: A systematic review from a TPACK perspective. Educ. Res. Rev. 2025, 49, 100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C.; Kennedy, G. Teaching for Quality Learning at University 5e; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aleven, V.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Glenn, R.A.; Koedinger, K.R. Instruction based on adaptive learning technologies. In Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 522–560. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, J.; Qian, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Dou, Z.; Ho, T.Y.; Yu, P.S. Trustworthiness in retrieval-augmented generation systems: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.10102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I.; Bularca, A.R. Artificial Intelligence Governance in Higher Education: The Role of Knowledge-Based Strategies in Fostering Legal Awareness and Ethical Artificial Intelligence Literacy. Societies 2025, 15, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD); Vincent-Lancrin, S.; van der Vlies, R. Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education: Promises and Challenges; OECD Education Working Paper No. 218, 2020; Report; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.T.; Liu, Y.K.; Tsai, Y.C.; Suen, S. Enhancing Python Learning Through Retrieval-Augmented Generation: A Theoretical and Applied Innovation in Generative AI Education. In Innovative Technologies and Learning; Cheng, Y.P., Pedaste, M., Bardone, E., Huang, Y.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Research in Education: Evidence-Based Inquiry; MyEducationLab Series; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.