Performance Evaluation of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycled Aggregates in Mortar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Cement

2.1.2. Aggregates

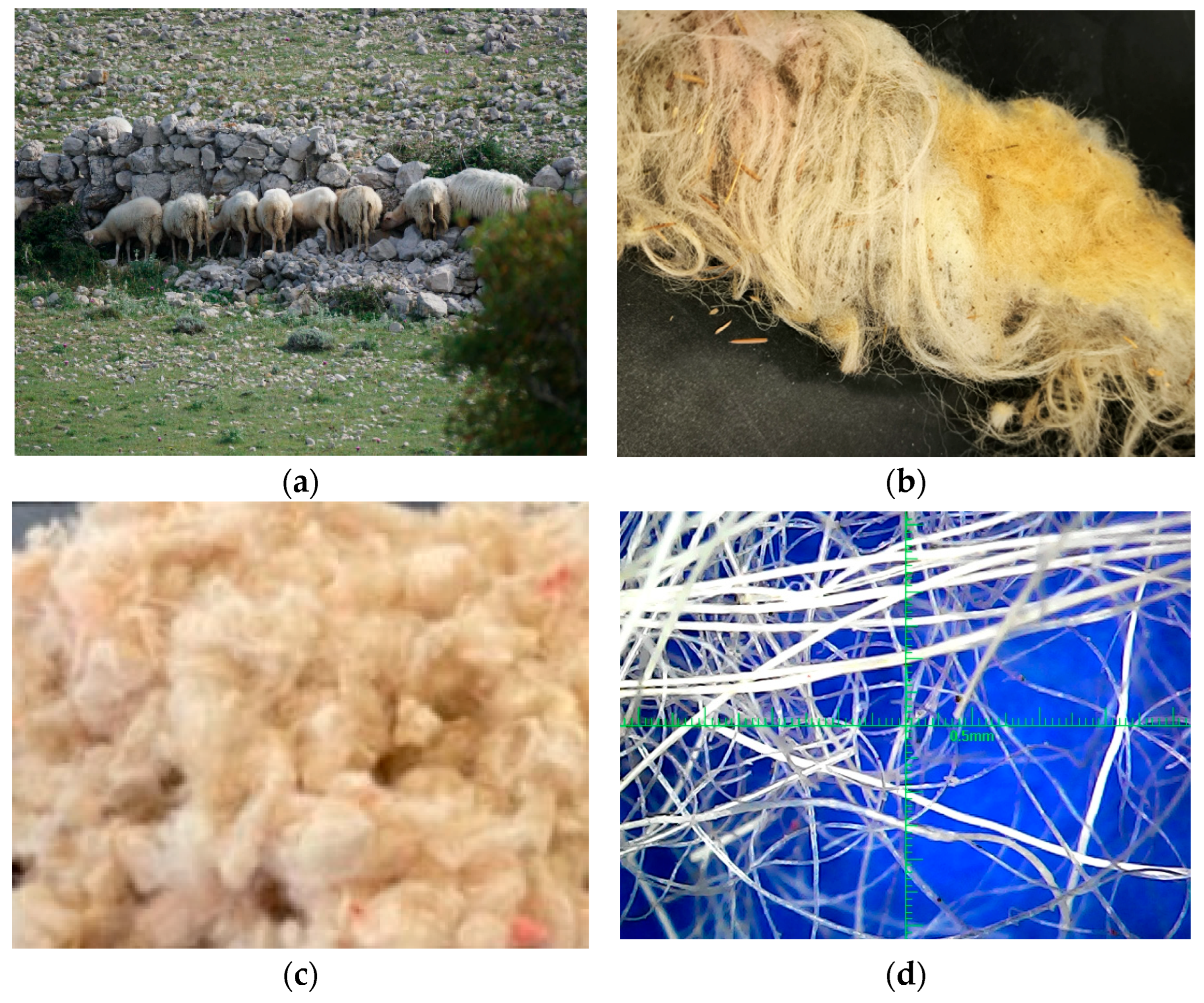

2.1.3. Sheep Wool Fibers

2.1.4. Design of Mortar Composition

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Mixing Procedure and Specimen Preparation

2.2.2. Consistency of Fresh Mortars

2.2.3. Three-Point Bending

2.2.4. Compressive Strength

2.2.5. Microstructure of Mortars

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mortar Workability

Influence of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycle Aggregates on Fresh Mortar Workability

3.2. Flexural Strength

Influence of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycle Aggregates on Flexural Strength

3.3. Specific Fracture Energy

Influence of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycle Aggregates on Specific Fracture Energy

3.4. Compressive Strength

Influence of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycle Aggregates on Compressive Strength

3.5. Mortar Microstructure

Influence of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycle Aggregates on Mortar Microstructure

4. Conclusions

- Regarding the workability of fresh mortar, with the selected fiber dosage (0.1% by mass) and recycled aggregate replacement ratio (30%), all fresh mortars remained workable and suitable for casting with vibration.

- Flexural test results indicate that sheep wool fibers are particularly effective in compensating for the brittleness of standard mortars, thereby improving their ductility under bending.

- Compressive strength results show that the influence of sheep wool fibers on compressive strength cannot be generalized and must be assessed according to aggregate characteristics and matrix composition.

- Statistical evaluation confirmed that statistically significant differences between mortars for flow value, compressive strength, peak flexural strength, and specific fracture energy (p < 0.001 in all cases) are inherent to mortar design rather than experimental scatter.

- Effect size analysis showed that mortar composition explains the majority of the observed variability (η2 ≈ 0.79 to 0.95), supporting the reported increases in compressive strength for selected mortars and clearly identifying fiber incorporation as the dominant parameter influencing specific fracture energy.

- Overall, the results confirm that sheep wool fiber micro-reinforcement is the dominant parameter controlling fracture energy, while recycled aggregate incorporation does not compromise fracture performance, supporting the development of sustainable, high-toughness cementitious composites.

- A comparative benchmarking of all mortars against R0 (increase ↑ or decrease ↓) is shown in Table 4. It reveals consistent reductions in flow for all modified mortars (−4% to −31%), particularly in wool fiber micro-reinforced mortars. While compressive and peak flexural strengths show mortar-dependent changes, the most significant effect is observed in specific fracture energy, which increases by more than one order of magnitude in all wool fiber micro-reinforced mortars (+966% to +1233%), indicating a pronounced improvement in post-crack behavior despite reduced workability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Junior, G.A.F.; Leite, J.C.T.; Mendez, G.d.P.; Haddad, A.N.; Silva, J.A.F.; da Costa, B.B.F. A Review of the Characteristics of Recycled Aggregates and the Mechanical Properties of Concrete Produced by Replacing Natural Coarse Aggregates with Recycled Ones—Fostering Resilient and Sustainable Infrastructures. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, A.; Vocciante, M. Improved management of water resources in process industry by accounting for fluctuations of water content in feed streams and products. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 39, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.; Zafar, M.S.; Nazir, M.R.; Cirrincione, L.; Vocciante, M. Comparative mechanical performance evaluation of recycled brick aggregate concrete and natural aggregate concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 116, 114702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, M.; Iversen, L.L.; Best, J.; Franks, D.M.; Hackney, C.R.; Latrubesse, E.M.; Tusting, L.S. Sand, gravel, and UN sustainable development goals: Confict, synergies, and pathways forward. One Earth 2021, 4, 1095–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.L.S.; Anjos, M.A.S.; Nóbrega, A.K.C.; Pereira, J.E.S.; Ledesma, E.F. The role of powder content of the recycled aggregates of CDW in the behaviour of rendering mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 208, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Stakeholder-associated factors influencing construction and demolition waste management: A systematic review. Buildings 2021, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaze, M.H.; Shrivastava, S. Development and performance evaluation of recycled brick waste-based geopolymer brick for improved physcio-mechanical, brick-bond and durability properties. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherman, I.-E.; Lakatos, E.-S.; Clinci, S.D.; Lungu, F.; Constandoiu, V.V.; Cioca, L.I.; Rada, E.C. Circularity Outlines in the Construction and Demolition Waste Management: A Literature Review. Recycling 2023, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spišáková, M.; Mésároš, P.; Mandičák, T. Construction Waste Audit in the Framework of Sustainable Waste Management in Construction Projects—Case Study. Buildings 2021, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, O.F. Sustainable concrete with recycled brick and ceramic aggregates: A statistical validation and performance evaluation. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Min, Z.; Lin, Q.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, M.; Feng, A.; et al. Mechanical and microstructural properties of glass powder-modified recycled brick-concrete aggregate concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jin, S.; Cheng, P.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z. Study on Mechanical Properties and Carbon Emission Analysis of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Brick Aggregate Concrete. Polymers 2024, 16, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouna, Y.; Suryanto, B. Recycled Aggregate Concrete: Effect of Supplementary Cementitious Materials and Potential for Supporting Sustainable Construction. Materials 2025, 18, 5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.B.; Sampaio, C.H.; Moncunill, J.O.; Lima, M.M.D.; Herrera La Rosa, G.T.; Veras, M.M.; Ambrós, W.M.; Cazacliu, B.G.; Solsona, A. Reuse of Coarse Aggregates Recovered from Demolished Concrete Through the Jigging Concentration Process in New Concrete Formulations. Materials 2025, 18, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Hou, P.; Zhou, L.; Golewski, G.L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, T. The fracture performance of modified recycled concrete: Influence of recycled aggregate and recycled powder. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2026, 331, 111709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Luo, S.; Liu, S.; Shao, J.; He, Y.; Li, Y. Effect of emulsifier on the interface structure and performance of reclaimed asphalt pavement aggregate cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.K.; Sahdeo, S.K.; Ransinchung RN, G.D.; Praveen Kumar, P. Performance of cement mortar mixes containing fine reclaimed asphalt pavement aggregates and zinc waste. Adv. Cem. Res. 2024, 36, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, G.; Michelacci, A.; Manzi, S.; Bignozzi, M.C. Assessment of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) as recycled aggregate for concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, S.; Blankson, M.A. Environmental performance and mechanical analysis of concrete containing recycled asphalt pavement (RAP) and waste precast concrete as aggregate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 264, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Mahmoud, E.; Khodair, Y.; Patibandla, V.C. Fresh, mechanical, and durability characteristics of self-consolidating concrete incorporating recycled asphalt pavements. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2014, 26, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, M.; Sanchez, A.; Gil, A.; Araya-Letelier, G.; Burbano-Garcia, C.; Silva, Y.F. Use of animal fiber-reinforcement in construction materials: A review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, G.; Arvindh Seshadri, S.; Devnani, G.L.; Sanjay, M.R.; Siengchin, S.; Prakash Maran, J.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Karuppiah, P.; Mariadhas, V.A.; Sivarajasekar, N.; et al. Environment friendly, renewable and sustainable poly lactic acid (PLA) based natural fiber reinforced composites—A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Hossain, M.S.; Ahmed, S.; Sarwaruddin Chowdhury, A.M. Fabrication and characterization of eco-friendly composite materials from natural animal fibers. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parashar, S.; Chawla, V.K. A systematic review on sustainable green fibre reinforced composite and their analytical models. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 6541–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.A.; Antonio, J. Animal-based waste for building acoustic applications: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleutério, T.; Trota, M.J.; Meirelles, M.G.; Vasconcelos, H.C. A Review of Natural Fibers: Classification, Composition, Extraction, Treatments, and Applications. Fibers 2025, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, T.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. A review of the recent developments in biocomposites based on natural fibres and their application perspectives. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 77, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.S.; Azum, N.; Khan, A.; Rub, M.A.; Hassan, M.I.; Fatima, K.; Asiri, A.M. Green Composites Based on Animal Fiber and Their Applications for a Sustainable Future. Polymers 2023, 15, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midolo, G.; Porto, S.M.C.; Cascone, G.; Valenti, F. Sheep Wool Waste Availability for Potential Sustainable Re-Use and Valorization: A GIS-Based Model. Agriculture 2024, 14, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlato, M.C.M.; Porto, S.M.C.; Valenti, F. Assessment of sheep wool waste as new resource for green building elements. Build. Environ. 2022, 225, 109596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- HRT Magazin. Available online: https://magazin.hrt.hr/price-iz-hrvatske/ovcja-vuna-postala-ekoloska-prijetnja-zbog-nedostatka-sustavnog-zbrinjavanja-11478185 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009, Laying Down Health Rules as Regards Animal By-Products and Derived Products not Intended for Human Consumption and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1774/2002 (Animal By-Products Regulation). 21 October 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009R1069 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Regulation (EU) No 142/2011 of 25 February 2011, Implementing Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying Down Health Rules as Regards Animal By-Products and Derived Products Not Intended for Human Consumption and Implementing Council Directive 97/78/EC as Regards Certain Samples and Items Exempt from Veterinary Checks at the Border Under that Directive (Text with EEA Relevance). 25 February 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32011R0142 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Wani, I.A.; Kumar, R.u.R. Experimental investigation on using sheep wool as fiber reinforcement in concrete giving increment in overall strength. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 4405–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, R.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Mohammadhosseini, H.; Mohamed, A.M.; Siddika, A.; Alrshoudi, F.; Alaskar, A. Utilization of sheep wool as potential fibrous materials in the production of concrete composites. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 30, 101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, R. Enhanced acoustic properties of concrete composites comprising modified waste sheep wool fibers. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 56, 104815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapulionienė, R.; Vaitkus, S.; Vėjelis, S. Development and research of thermal-acoustical insulating materials based on natural fibres and polylactide binder. Mater. Sci. Forum 2017, 908, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U.; Iannace, G. Acoustic Characterization of Natural Fibers for Sound Absorption Applications. Build. Environ. 2015, 94, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dénes, O.; Florea, I.; Manea, D.L. Utilization of sheep wool as a building material. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 32, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantilli, A.P.; Jóźwiak-Niedźwiedzka, D. Influence of Portland cement alkalinity on wool reinforced mortar. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Constr. Mater. 2020, 174, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantilli, A.P.; Jóźwiak-Niedźwiedzka, D. The effect of hydraulic cements on the flexural behavior of wool reinforced mortars. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Bio-Based Building Materials, Belfast, UK, 26–28 June 2019; Volume 37, pp. 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, B.; Shaji, S.; Jafri, M.; Raj, R.S.; Anand, N.; Lubloy, E. Natural and synthetic fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete subjected to standard fire temperature. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruehansapong, S.; Khamput, P.; Yoddumrong, P.; Kroehong, W.; Thuadao, V.; Abdulmatin, A.; Senawang, W.; Pulngern, T. Enhancement of recycled aggregate concrete properties through the incorporation of nanosilica and natural fibers. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Játiva, F.; Tamayo, J.M.; Silva, T.; Granja, O.; Cabrera, R.; Arce, X.; Guadalupe, L.; Guillen, M.; Koenders, E.; Lantsoght, E. Experiments on concrete test beams with recycled aggregates and natural fibers. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 64, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corscadden, K.W.; Biggs, J.N.; Stiles, D.K. Sheep’s wool insulation: A sustainable alternative use for a renewable resource? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 86, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffner, H.; Popescu, C. Chapter 8 Wool fibres. In Handbook of Natural Fibres, Types, Properties and Factors Affecting Breeding and Cultivation; Kozłowski, R., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak-Niedźwiedzka, D.; Fantilli, A.P. Wool-Reinforced Cement Based Composites. Materials 2020, 13, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.H.; Ho, M.C. Toxicity characteristics of commercially manufactured insulation materials for building applications in Taiwan. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1:2011; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. The European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Nexe Group. Grend CEM II/A-M(S-V) 42.5 N Technical Instructions. Available online: https://www.nexe.hr/en/products/cement/grand/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- EN 196-6:2018; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 6: Determination of Fineness. The European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- EN 1097-6: 2022; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. The European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- EN 933-1:1997; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates—Part 1: Determination of Particle Size Distribution—Sieving Method. The European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1997.

- Raffaelli, D.; Vujasinović, E. Influence of breeding conditions and sheep breeds on quantity and quality of wool in Croatia—Investigations of lstrian–Cres region. Stočarstvo 1994, 48, 443–459. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/163795 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Gelana, D.; Kebede, G.; Feleke, L. Investigation on Effects of Sheep Wool fiber on Properties of C-25 Concrete. Saudi J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 3, 156–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmogahzy, Y.E. 8—Fibers. In The Textile Institute Book Series, Engineering Textiles, 2nd ed.; Elmogahzy, Y.E., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2020; pp. 191–222. ISBN 9780081024881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 196-1:2003; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 1: Determination of Strength. The European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- EN 1015-3:1999/A1:2004; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 3: Determination of Consistence of Fresh Mortar (by Flow Table). The European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- EN 1015-11:2019; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 11: Determination of Flexural and Compressive Strength of Hardened Mortar. The European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- de Lima, N.G.; Figueiredo, F.B.; de Vargas Junior, F.M.; Figueiredo, N.L.B. Analysis of the physical and mechanical properties of mortar with the incorporation of natural wool fiber from Pantanal sheep. Cad. Pedagógico 2025, 22, e14946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elawadly, N. Eco-Friendly Sustainable Concrete with Recycled Crushed Red Bricks: Evaluating Mechanical Performance and Durability. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. Innov. 2022, 5, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juradin, S.; Boko, I.; Netinger Grubeša, I.; Jozić, D.; Mrakovčić, D. Influence of Different treatment and amount of Spanish broom and hemp fibres on the mechanical properties of reinforced cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | CEM II/A-M(S-V) 42.5 N | EN 197-1 Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 3.0 | |

| Blaine surface (m2g−1) | 0.36 | |

| Initial setting time (min) | 190 | ≥60 |

| Dimensional stability (mm) | 0.5 | ≤10 |

| Compressive strength at 2 days (MPa) | 23 | ≥10 |

| Compressive strength at 28 days (MPa) | 55 | ≥42.5 ≤ 62.5 |

| SO3 (%) | 3.3 | ≤3.5 |

| Cl (%) | 0.007 | ≤0.10 |

| Aggregate | Density (kg/m3) | Absorption (%) | Fines (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NA | 2650 | 3.08 | 5.49 |

| RCA | 2560 | 3.40 | 6.71 |

| RAA | 2460 | 3.63 | 8.74 |

| RBA | 2467 | 5.64 | 8.82 |

| Mortar | w/c | Cement (g) | Natural Aggregate (g) | Recycled Aggregate (g) | Sheep Wool Fibers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (wt% Mix) | (% Vol.) | |||||

| R0 | 0.50 | 450 | 1350 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R0-W | 0.50 | 450 | 1350 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| RC | 0.50 | 450 | 945 | 405 | 0 | 0 |

| RA | 0.50 | 450 | 945 | 405 | 0 | 0 |

| RB | 0.50 | 450 | 945 | 405 | 0 | 0 |

| RC-W | 0.50 | 450 | 945 | 405 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| RA-W | 0.50 | 450 | 945 | 405 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| RB-W | 0.50 | 450 | 945 | 405 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| RM-W | 0.50 | 450 | 945 | 405 1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Mortar | Flow | Compressive Strength | Flexural Strength (Peak) | Specific Fracture Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0-W | ↓ (−6%) | ↓ (−18%) | ↓ (−10%) | ↑ (+1070%) |

| RC | ↓ (−24%) | ↑ (+30%) | ↑ (+20%) | ↑ (+30%) |

| RA | ↓ (−10%) | ↓ (−5%) | ↓ (−7%) | ↑ (+29%) |

| RB | ↓ (−4%) | ↑ (+18%) | ↑ (+22%) | ↑ (+14%) |

| RC-W | ↓ (−31%) | ≈ | ↓ (−7%) | ↑ (+1153%) |

| RA-W | ↓ (−25%) | ↓ (−25%) | ↓ (−27%) | ↑ (+966%) |

| RB-W | ↓ (−18%) | ↑ (+24%) | ↓ (−3%) | ↑ (+1233%) |

| RM-W | ↓ (−24%) | ↑ (+10%) | ↓ (−4%) | ↑ (+1105%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mrakovčić, S.; Juradin, S.; Netinger Grubeša, I.; Kramarić, D. Performance Evaluation of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycled Aggregates in Mortar. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020962

Mrakovčić S, Juradin S, Netinger Grubeša I, Kramarić D. Performance Evaluation of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycled Aggregates in Mortar. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):962. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020962

Chicago/Turabian StyleMrakovčić, Silvija, Sandra Juradin, Ivanka Netinger Grubeša, and Dalibor Kramarić. 2026. "Performance Evaluation of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycled Aggregates in Mortar" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020962

APA StyleMrakovčić, S., Juradin, S., Netinger Grubeša, I., & Kramarić, D. (2026). Performance Evaluation of Sheep Wool Fibers and Recycled Aggregates in Mortar. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020962