Abstract

Background/Objectives: The resin infiltration protocol was introduced as a minimally invasive approach for the treatment of incipient carious lesions using low-viscosity resins with high penetration coefficient. This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of resin infiltration in hypomineralized anterior teeth of paediatric patients, based on aesthetic improvement, colour change (ΔE), and visual perception. The risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa and physiotherapy evidence database scales. The level of evidence was assessed using the grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation tool. Methods: The following five databases were searched: Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane, and PubMed. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023405299). Results: The search identified 130 preliminary references related to the population, intervention, control, and outcome question, identified from the PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane databases, respectively. In addition, two items were added from the grey literature. Ten articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in the qualitative analyses, and only three studies were included in the quantitative analyses. Positive results regarding stain-size reduction and colour improvement with resin infiltration (Icon®; DMG, Hamburg, Germany), were reported in moderately severe lesions. Luminosity increased immediately after treatment, and the mean difference in total color change (ΔE), T0–T1 was significant (ΔE, 5.45; confidence interval, 1.94 to 8.96; p < 0.01). The most favourable clinical outcomes were observed following the initial resin infiltration. Moreover, the results were maintained at the 6 month follow-up. Conclusions: Infiltration resin can successfully mask white or white/creamy opacities characteristic MIH affected enamel, similar to those in carious enamel for which it was designed. It yields acceptable aesthetic results in anterior teeth with mild to moderate MIH lesions. Lack of predictability is the main limitation of this therapeutic option.

1. Introduction

Several studies have evaluated enamel defects such as amelogenesis imperfecta, fluorosis, and hypoplasia. However, molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH) has recently attracted the interest of many researchers in this field. The term MIH was introduced in 2001 to describe defects affecting one or more permanent first molars, with or without involvement of the anterior teeth. The European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry, recognized this condition as a pathology in 2003; the term MIH was accepted, and diagnostic criteria were established [1], and further refined in more recent clinical and epidemiological studies [2,3,4,5]. Molar-Incisor Hypomineralization (MIH) is defined as qualitative defects resulting from alterations in the mineralization or maturation phase of the teeth. These defects manifest in the area of the tooth corresponding to the developmental stage at which the disorder occurs [6]. The precursor agents of these defects have not yet been determined. Numerous researchers have identified associated factors; however, despite being a prevalent condition worldwide, no consensus has been reached regarding a single etiological factor or a group of factors necessary to cause this pathology [6]. Unlike other developmental defects of the enamel, hypomineralization is a multifactorial qualitative defect with a genetic component that makes treatment challenging [7]. Clinically, the affected teeth show an alteration in enamel translucency, with color variations ranging from white to yellow or brown and boundaries clearly distinguishable from the unaffected enamel areas. Owing to the porosity of these defects, the enamel can sometimes be easily detached under masticatory forces [8]. MIH lesions in molars extend throughout the entire thickness of the enamel, starting at the Amelocemental Junction (ACJ) and ending at the surface enamel [9]. Scanning electron microscopy has allowed for the determination that enamel affected by MIH exhibits less dense prismatic structures, partial loss of prismatic patterns, loosely packed crystals, less defined prism edges, more pronounced interprismatic spaces, and wider regions of the sheath [10]. The main histological difference between the white spot lesion caused by incipient caries and MIH lesions is the depth of involvement, greater internal porosity, the variable thickness of the outer hypomineralized layer, and the presence of organic content [11]. Enamel defects typical of MIH usually affect the cusps of the molars and the incisal edges of the incisors. The severity of enamel hypomineralization can vary not only between patients but also within the same patient, which allows lesions to be classified into different stages [12]. Patients with MIH often have associated problems, such as aesthetic concerns, loss of restorations, need for re-interventions, and hypersensitivity, resulting in a decreased quality of life [6]. Owing to the higher visibility, lesions affecting the anterior teeth directly influence the dental aesthetics and quality of life of paediatric patients and pose a significant challenge for dentists. Furthermore, owing to the growing interest in the treatment of opacities in the anterior teeth, contemporary aesthetic requirements, and increasing acceptance of minimally invasive therapies, patients with MIH seek more effective and predictable conservative alternatives for the treatment of enamel as soon as root maturation has been completed, typically after 9 years, with a median of 11 years [13]. Other non-invasive and minimally invasive approaches have been proposed for the management of MIH-related anterior lesions, including topical fluoride varnishes and calcium- and phosphate-based remineralizing agents such as CPP-ACP. However, these approaches mainly aim to improve mineral content and reduce hypersensitivity, with limited and unpredictable aesthetic outcomes in demarcated opacities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Conservative treatment options for MIH-affected anterior teeth.

Resin infiltration, which was introduced as a minimally invasive approach for the treatment of incipient carious lesions, has also been applied to hypomineralization lesions. Its mechanism of action is based on the masking principle. This principle is based on light scattering changes within the lesions, where the refractive indices (IR) of the different media (1.62 healthy enamel, 1.33 aqueous medium or 1.0 air) are changed. Therefore, porous enamel lesions lose their whitish appearance when filled. The infiltrated lesion has a refractive index more comparable to that of healthy enamel, resembling each other. Consequently, this treatment can be used not only to stop carious lesions, which was its initial indication, but also to improve the aesthetic appearance of enamel defects on the buccal surfaces of anterior teeth [14]. However, studies on its usefulness are limited, and consensus regarding the protocol for resin in-filtration in hypomineralized anterior teeth is lacking.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the efficacy of a marketed resin infiltrant (Icon®; DMG, Hamburg, Germany) for the treatment of hypomineralized lesions in anterior teeth, focusing on primary outcomes related to aesthetic masking, colour change (ΔE values), and visual perception after treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

Protocol Registration: A systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 recommendations [15]. Data are reported according to the structure and content outlined in the 27 items included in the statement. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023405299; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023405299. accessed on 6 May 2024), and the PRISMA checklist (Supplementary Materials) was used to guide the systematic review process.

Population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes (PICO): This review was performed to answer the PICO question: Does the application of resin infiltration (Icon®) (I) improve aesthetics and visual perception (O) in paediatric patients (P) with hypomineralized anterior teeth when compared with the baseline (pre-treatment) condition (C)?

Therefore, this systematic review primarily evaluates the effectiveness of resin infiltration using before–after and single-arm study designs, rather than comparisons with parallel control groups.

Search strategy: The Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane, and PubMed electronic databases were searched to identify the most relevant studies published up to March 2024. Additionally, the reference lists of the retrieved studies were examined to identify other potentially eligible studies that did not appear in the preliminary database search. The search strategy was designed by considering previous studies in the field and the most cited descriptors. The keywords used to identify articles were as follows:

- P: ‘pediatric* dentistr*’ or ‘paediatr* dentistr*’ or child* or infant* or bab* or boy* or kid* or preschool* or newborn*;

- I: ICON® or infiltration* or ‘dent* infiltration*’ or infiltrant* or ‘hydrocloric acid’ or ‘chemical erosion’;

- C:‘MIH’ or ‘molar incisor hypomineralization*’ or ‘molar incisor hypomineralisation*’ or hipomineralization* or ‘tooth hypomineralization’ or ‘enamel defect*’ or ‘enamel opacity’;

- Q: ‘quality of life’ or esthetic*.

Truncations and quotation marks were used in each database. The general search strategy was as follows: (((ALL = (‘Pediatric* dentistr*’ or ‘paediatr* dentistr*’ or child* or infant* or bab* or boy* or kid* or preschool* or newborn*)) AND ALL = (ICON® or infiltration* or ‘dent* infiltration*’ or ‘infiltrant’ or hydrochloric)) AND ALL = (‘MIH’ or ‘molar incisor hypomineralization*’ or ‘molar incisor hypomineralisation*’ or ‘hyomineralization*’ or ‘tooth hypomineralization’ or ‘enamel defect*’ or ‘enamel opacity’)) AND ALL = (‘Quality of life’ or esthetic*).

Eligibility criteria: We included studies in which hypomineralization defects in the anterior teeth of paediatric patients were treated using (Icon®; DMG, Hamburg, Germany) infiltration resin. The inclusion criteria were human studies in which infiltration resins were used as the sole treatment and the outcome was evaluated qualitatively or quantitatively. Randomized clinical trials, longitudinal studies, and retrospective and prospective cohort or case–control studies were included. No restrictions were placed on the year of publication or language.

Study selection: The references identified using the search strategy were exported from each database to Mendeley v2.109.0reference management software (Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands) to check for duplicates. After discarding duplicates, two reviewers (MD-CR and MA-VR) independently evaluated the titles and abstracts of all the identified articles. In case of disagreement, a third author (M-CP) was consulted. If the abstract did not provide sufficient information for a decision, the full text of the article was reviewed. Finally, articles that met the requirements were included in the study. Studies were included in the meta-analysis only when complete quantitative data were available.

Data extraction: The following main variables were recorded for each article: author and year of publication, study type, sample size (number of patients and number of teeth), and demographic variables (sex and age). Regarding the diagnostic variables, the use of a questionnaire for assessing the quality of life and aesthetic perception of the participants and the methods used for diagnosing the degree and severity of MIH and the lesion color were recorded. Finally, the most relevant results regarding the effects of infiltration and follow-up duration of each study were collected. Outcomes related to enamel hardness, fracture resistance, hypersensitivity reduction, or structural reinforcement were not considered primary outcomes and were recorded only when reported as ancillary information.

Risk of bias/quality assessment of individual studies: The Newcastle–Ottawa [16] and physiotherapy evidence database (PEDro) scales were used to evaluate the quality of observational [17,18] and experimental or external-control-arm studies [19,20], respectively. Disagreements between the two investigators were resolved by consensus, and the third investigator was consulted in cases of doubt.

Level (certainty) of evidence: The grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation tool was used in the meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of treating hypomineralization lesions in the anterior teeth with resin infiltration and to analyse aesthetic improvement and changes in visual perception after treatment. This scale provides a structured and objective framework for evaluating the quality of scientific evidence and strength of recommendations, enables a systematic and transparent assessment of the meta-analysis results, and ensures reproducibility of the findings [21].

Statistical analysis: The mean differences in delta E, at three time points (T0 before treatment; T1 after treatment; and T6 6-month follow-up) were used to determine the mean difference between the different time points, employing a calculator for continuous variables based on the mean, standard deviation (SD), and sample size (Table 2). A meta-analysis was conducted using a random effects model with the inverse variance method. The effect size was estimated as the mean of the mean differences in mean delta E between T1–T0 and T6–T0. Forest plots of the meta-analyses were presented. A meta-analysis by subgroups was performed to assess the existence of a significant difference between the two time points using the Q-test. Publication bias was not calculated for this study due to the small number of articles available [22]. All statistical analyses were carried out using R software v. 4.3.3 with the package for meta mean: meta-analyses of single means. No formal sample size calculation was performed for the meta-analysis, as this study was limited to the number of eligible studies available in the literature that met the predefined inclusion criteria. Studies were included in the quantitative synthesis only when sufficient and comparable numerical data were reported, including mean ΔE values, standard deviations, and sample sizes at comparable time points. The reduced number of studies included in the meta-analysis reflects limitations in data availability within the existing evidence rather than a selective inclusion strategy.

Table 2.

Differences on means.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Flow Diagram

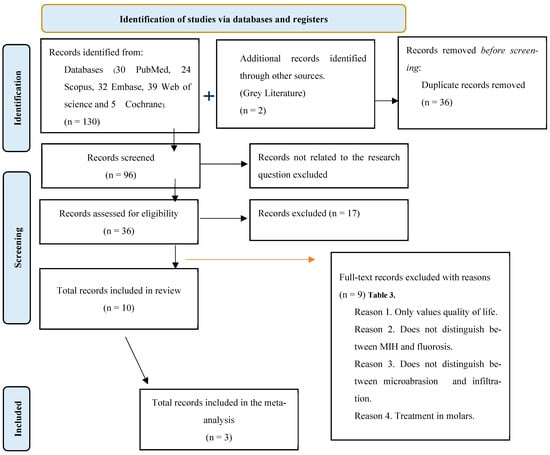

The search identified 130 preliminary references related to the PICO question. After excluding 36 duplicate articles, the remaining 96 were examined. Of these, 60 were excluded after reading the title and abstract because they were not related to the research question. The full texts of 36 articles were assessed for eligibility; 17 articles were excluded, and 19 articles were further evaluated. Of these, nine articles were excluded for various reasons (Table 3). Finally, 10 articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in the qualitative analysis. Only three of these studies were included in the quantitative analyses. The PRISMA flow chart provides an overview of the article selection process (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Reasons for excluding articles.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which includes searches of only databases and registers.

3.2. Quality Characteristics of the Included Studies

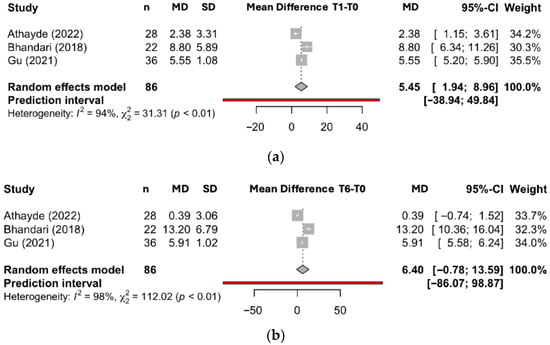

The characteristics of the 10 studies included in the systematic review are summarized in Table 4. The number of patients in the selected studies ranged from a minimum of 12 [25,35] to a maximum of 39 [23]. These data were missing in two studies [24,36]. A total of 300 teeth affected by MIH were treated with infiltration, with a maximum of 36 teeth [25] and a minimum of 9 teeth [36] in a single study. Regarding the distribution according to sex, similar ratios were observed in studies with available data: for example, M:F = 9:14 [20], 7:10 [37], and 22:17 [23]. Moreover, the cohorts mostly included young children. All studies focused on treating permanent anterior teeth with demarcated opacities categorized as MIH. Regarding the selection of teeth to treat according to the degree of involvement and severity of MIH, two studies included teeth with white/creamy opacities [23,35], six included only teeth with white opacities [17,18,20,25], and one study made no reference to the color of the defects [37]. Only one study [19] included teeth with both white/creamy and yellow/brown opacities. The diagnosis of MIH was based on the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry criteria in eight studies [17,20]. In the remaining two studies, the diagnostic criteria were not specified; however, the defects were classified as MIH lesions and the images included in the papers corresponded to MIH lesions [25,35]. Regarding the treatment protocol, eight studies [17,20] followed the manufacturer’s instructions for infiltration as follows: the affected areas were etched for 2 min with 15% hydrochloric acid (Icon Etch, DMG, Hamburg, Germany) and rinsed with air and water spray for 30 s. The lesions were dried by blowing air for 10 s, followed by the application of 99% ethanol (Icon Dry, DMG, Hamburg, Germany) for 30 s. Next, the infiltration resin was applied for 3 min (Icon-Infiltrant; DMG, Hamburg, Germany). After removal of excess using an air spray and dental floss, the resin was polymerized for 40 s. Resin infiltration was repeated with a 60 s infiltration time to allow the resin to penetrate residual porosities. Finally, the resin was polymerized for 40 s and polished with silicone discs and rubber pads. Selected examples of lesions before and after resin infiltration are presented below (Figure 2). In one study, the superficial layer of enamel was “gently” removed using a bur before applying the infiltration protocol [37], and in another study, the infiltration time was extended to 30 min [23]. Alghawe and Raslan, 2024 [19], included two types of etching, single and three applications, to compare the masking effect. Of the 10 studies evaluated, 2, 2, 1, and 5 were retrospective observational studies [17,18], randomized controlled clinical trials [15,19], an in vivo pilot study [37], and clinical trials [17,24,35], respectively. The meta-analysis revealed in T0–T1 a mean difference (MD) of 5.45 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 1.94 to 8.96. This result suggests a statistically significant difference in delta E values between the compared groups, as the confidence interval does not include the null value (0). The effect size is estimated to range from a small difference (1.94) to a considerably larger difference (8.96), indicating some variability across the included studies, but with an overall trend towards a positive difference in delta E. In T6–T0, the meta-analysis revealed a mean difference (MD) of 6.40 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from −0.78 to 13.59. This result indicates a non-significant difference in delta E values between the compared groups, as the confidence interval includes the null value (0). The wide range of the confidence interval, from a negative difference (−0.78) to a positive one (13.59), suggests considerable uncertainty and variability in the effect size across the studies included. Regarding the heterogeneity at T1-T0, the Q-test is 31.3 with a value of p < 0.001, which is confirmed by an I2 value of 94%. On the other hand, between T6–T0, the Q-test is 112, the p < 0.001 with an I2 of 98%, both meta-analyses show a high heterogeneity. The test for subgroups difference using a random effects model is Q = 0.05 and the p-value is 0.816. This indicates that there are no differences between the subgroups.

Table 4.

Summarize characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 2.

Representative clinical appearance of anterior teeth affected by molar–incisor hypomineralization.

3.3. Quality Assessment

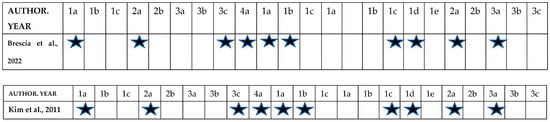

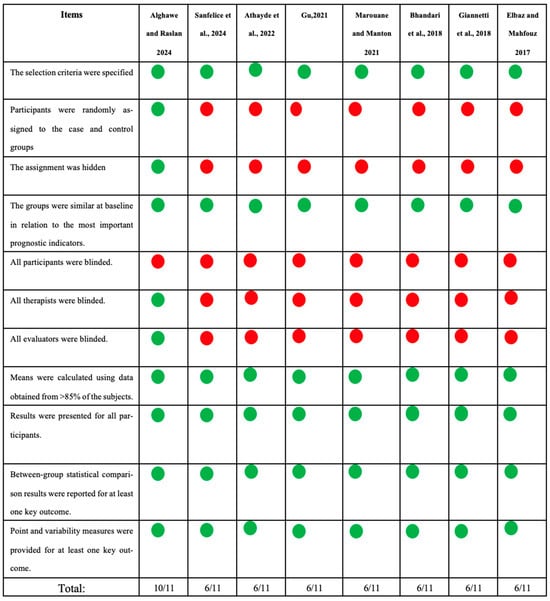

The quality of the studies was independently assessed by the same investigators. Observational and case–control studies [17,18] were evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (Figure 3) [16]. The scores obtained suggested moderate-to-low quality. However, for experimental and external-control-arm studies (Figure 4) [17,20] the PEDro scale scores suggested moderate-to-high quality.

Figure 3.

Quality of cohort studies assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment form for case–control studies. Selection. (1) Is the case definition adequate?: (a) Yes, with independent validation (one star); (b) Yes, e.g., record linkage or based on self-report; (c) No description. (2) Representativeness of the cases: (a) Consecutive or obviously representative series of cases (one star); (b) Potential for selection biases or not stated. (3) Selection of controls: (a) Community controls (one star); (b) Hospital controls; (c) No description. (4) Definition of controls: (a) No history of disease (endpoint) (one star); (b) No description of source. (5) Comparability of cases and controls controlled for confounders based on the design or analysis: (i) Controls for age (one star); Controls for other factors (list). (ii) Cohorts controlled for confounders are not comparable based on the design or analysis. (6) Exposure: (1) Ascertainment of exposure: (a) Secure record (e.g., surgical record) (one star); (b) Structured interview with blinding of case/control status (one star); (c) Interview without blinded of case/control status; (d) Written self-report or medical record only; (e) No description; (2) Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls: Yes (one star). No (3) Non-response rate: (a) Same rate for both groups (one star); (b) Non-respondents described; (c) Rate different between cases and controls with no description [17,18].

Figure 4.

Quality of experimental and external-control-arm studies assessed using the physiotherapy evidence database scale [19,20,23,24,25,35,36,37]. Green circle: yes; red circle: no.

3.4. Qualitative Synthesis

Analysis of the opacity and aesthetics: Four studies analyzed the changes in opacity after resin infiltration and the achieved aesthetic improvement, based on a direct on-screen clinical assessment of standardized patient photographs using the Fédération Dentaire Internationale colour-match scale [17,35] or simple scales such as total, partial, and no masking [23] or total attenuation, partial attenuation, and no change [36]. Most studies analyzed the results using standardized treatment photographs using image-analysis software. The most common approach was quantitative analysis of aesthetic improvement on standardized photographs using the classic CIELab* system [24,25]. Spectrophotometry was highlighted as an objective numerical analysis tool [19,25]. In one study, a quantitative analysis was conducted on standardized photographs of teeth that were transilluminated to detect lesion homogeneity and infiltration pattern [37]. ElBaz and Mahfouz, 2017 [20], were the only group to analyze opacity modifications using grayscale on periapical radiographs. The programs used for image processing were Photoshop CC for Mac (Photoshop CC for Mac v.23; San Jose, CA, USA), USA) [19,23], ImageJ v1.53 (Institutions of the United States National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) [37], an image analyzing Photoshop program [20] and Image I-solution v.1.x (IMT tech; Seoul, Republic of Korea).

3.5. Quantitative Synthesis

Figure 5 presents the results of the quantitative analyses of the studies by [23,24,25]. Estimation of the I2 value revealed the existence of heterogeneity (I2 = 94%; p < 0.01). Regarding the change in luminosity from T0 to T1 (Figure 5a), ΔE increased by 5.45 (confidence interval [CI], 1.94 to 8.96). The estimation was considered significant. Regarding the change in luminosity between T0 to T6 (Figure 5b), the I2 value indicated the presence of heterogeneity (I2 = 98%; p < 0.02). ΔE increased by 6.40 (CI, −0.78 to 13.59). The estimation was not significant. Given the limited number of studies included and the high heterogeneity observed, the results of the meta-analysis should be interpreted as exploratory.

Figure 5.

(a) Meta-analysis of delta E (mean T1–T0 difference). (b) Meta-analysis of delta E (mean T6–T0 difference) [23,24,25].

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to synthesize the available information on the effectiveness of the infiltration technique, as a minimally invasive option, for the treatment of hypomineralization defects in the anterior teeth of pediatric patients. It is important to clarify that the primary outcomes evaluated in this systematic review were aesthetic masking, colour change (ΔE), and visual perception, as directly reported in the included studies. Other outcomes frequently discussed in the literature, such as enamel hardness, fracture resistance, hypersensitivity reduction, and structural reinforcement, were not directly assessed in the analyzed studies and are therefore presented exclusively as supportive or contextual evidence derived from external sources. In compliance with this strict requirement, only 10 studies in which anterior teeth of patients diagnosed with MIH were included to analyze the efficacy of the infiltration technique. As the structure and composition of MIH lesions differ from those of other color defects, such as incipient carious lesions and fluorosis [26], a distinction emphasized in foundational MIH diagnostic research [4] and prevalence reviews [7,10,38,39,40]. The resin infiltration protocol was introduced as a minimally invasive approach for the treatment of incipient carious lesions using low-viscosity resins with high penetration coefficient, such as (Icon®; DMG, Hamburg, Germany). Subsequently, this protocol was applied to fluorotic lesions, with case-based evidence on aesthetic improvement in fluorosis available in recent clinical reports [41]. White-spot lesions of initial enamel caries and fluorotic defects are characterized by subsurface porosity, although the surface layer remains relatively intact or even hypermineralized [42]. These characteristics differ completely from those of MIH lesions [43], whose structural heterogeneity and developmental pathophysiology have been extensively summarized in recent narrative reviews [44].

MIH defects usually affect the entire thickness of the enamel, starting at the amelodentinal junction and ending at the superficial enamel. However, all histological studies have been performed on extracted molars, and structural differences in the incisor lesions cannot be ruled out. The main histological differences from incipient carious lesions, for which the infiltration technique was designed, seem to be the depth of involvement, greater internal porosity, variable thickness of the external hypermineralized layer, and presence of organic content [10]. These characteristics are consistent with the microstructural findings described by Neboda et al. [10], and they aligned with updated etiological syntheses [39]. These factors affect the penetrability of the infiltrating resin, which compromises the predictability of the outcomes of this therapeutic approach. The reviewed articles mostly included white and creamy/white opacities, which are less porous and more similar to normal enamel than yellow and brown opacities, which are associated with a decrease in mineral content of up to 11% and 28%, respectively, compared with healthy enamel [27]. However, white opacities have a higher luminance intensity and appear whiter than white post-orthodontic lesions and healthy enamel. This makes them difficult to mask, a challenge also highlighted in aesthetic infiltration studies such as that of Mazur et al. [34] and reflected in patient-reported aesthetic outcomes [32]. Most reviewed studies reported an improvement in the appearance of all treated teeth, and only one study [25] reported that the appearance of 7 of the 20 treated teeth remained unchanged. Despite these variations, the conclusions drawn from the reviewed studies affirm that infiltration is a valid alternative for improving hypomineralised anterior teethowing to its low invasiveness. However, the lack of predictability and need to adapt the protocol when treating teeth diagnosed with MIH were consistently cited as major problems [23] a concern echoed in comparative assessments of microabrasion and infiltration [43,45].

Regarding the infiltration protocol, nine of the ten included studies followed the manufacturer’s instructions for resin infiltration. However, resin penetrability in hypomineralization lesions is different compared with that in incipient carious and fluorosis lesions owing to the variable depth and porosity, higher organic components, and variable thickness of the hypermineralized layer. Therefore, in one study [23] the original protocol was modified by increasing the infiltration time to 30 min, which improved the percentage of total lesion masking. Moreover, ref. [19] compared two application methods according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The location, extent, and homogeneity of the hypomineralization defect influence the aesthetic outcome of infiltration. In one study which evaluated the degree of homogeneity [23], heterogeneous lesions had lower porosity and higher mineral content, thus requiring a longer infiltration time. In addition, hypomineralization lesions have a higher organic protein content; therefore, Crombie proposed deproteinization prior to infiltration [6]. However, no significant improvement in outcomes was observed [37] which aligns with findings from later resin–enamel interaction studies [32], and with systematic evaluations of resin infiltration in non-cavitated lesions [45].

Regarding the evaluation of aesthetic outcomes, the criteria used to establish the validity and efficacy of this technique differed between studies. Three studies used only qualitative criteria [17,35,36], five used only quantitative criteria [20,25,36,37], and two used both qualitative and quantitative criteria [19,23]. Among the qualitative criteria, visual assessment of the defect characteristics using standardized photographs according to the Fédération Dentaire Internationale scale stands out, yielding the following results: 66.67% excellent, 20.83% good, 8.3% sufficient, and 4.2% insufficient [17]. This reliance on photographic evaluation is consistent with methodological observations regarding shade-matching variability [46].

At the quantitative level, the repeated use of Icon-Etch cycles on white/creamy opacities provided better results than did a single application. A single application of Icon-Etch on yellow/brown opacities resulted in the least effective color matching with the adjacent healthy enamel [19], in agreement with the color-matching differences documented by Gençer et al. [33] and Mazur et al. [34]. These outcomes are consistent with findings from controlled clinical evaluations of developmental enamel defects [47]. Athayde et al., 2022 [23], reported a significant difference in luminosity between healthy tissue and opacities 15 min after infiltration. The mean ΔE immediately after treatment was 4.07 (standard deviation, 3.07) in the test group and 7.35 (standard deviation, 3.54) in the control group (p < 0.01). Bhandari et al., 2018 [24], reported a general reduction in tooth whiteness based on the differences in colour measurements (ΔE). Additionally, Gu, 2021 [25], reported a reduction in the lesion area, and a significant decrease in colour difference (ΔE) between the defect and healthy tissue after infiltration (p < 0.001). These results align with early experimental data on resin infiltration optical behavior [14]. The results of our meta-analysis are consistent with the findings of [23,25], who reported a significant difference between the luminosity values before (T0) and immediately after treatment (T1). However, no significant difference was observed between the values before (T0) and at the 6-month follow-up (T6). This proves the stability of the results and rules out the possibility of an improvement in the effect of infiltration over time. The results should be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of studies available. In addition, the large heterogeneity observed increases the uncertainty of the T6 results. The high heterogeneity observed across studies may be explained by several factors, including differences in MIH severity, lesion colour, extent and homogeneity of opacities, variations in resin infiltration protocols, differences in outcome assessment methods, and heterogeneity in follow-up duration. These methodological and clinical differences limit the robustness of pooled estimates and reinforce the need for cautious interpretation of quantitative results. For this reason, to mitigate this heterogeneity, a random effects model has been used. Resin infiltration is irreversible. Once the infiltrant has been applied and light-cured, a second infiltration to improve the result is not possible because some of the subsurface pores are blocked by the resin. If the aesthetics do not improve, it may be necessary to use more invasive approaches, such as partial or total removal of the infiltrated lesion, followed by restoration with composite resin [37], a sequence comparable to restorative strategies described for more severe developmental defects [41]. Therefore, success depends on a correct initial diagnosis in which the color, location, and extent of the opacities are carefully evaluated. In the reviewed studies, standardized photographs were proposed as the main diagnostic tool for the initial categorization of opacities, and transillumination and spectrophotometry were used an as additional diagnostic tools. The use of transillumination allows for the estimation of the depth and better qualitative visualization of the peripheral extent or area of the opacities. However, Marouanne and Manton questioned the usefulness of trans-illumination in the analysis of hypomineralization lesions, arguing that the information provided was limited, contributing to the evaluation of the dimensions and depth of only one surface of the lesion, leaving others unexamined [37]. Similarly, the use of a spectrophotometer for quantitative analysis before and after opacity treatment was questioned by Athayde et al. because of the irregular shape of the lesions [23]. The authors did not consider spectrophotometry useful for such an analysis because the probe tip of the device has a fixed round shape with a diameter of 5 mm. In many cases, it is impossible to place the tip over the opacity without touching a healthy area, and vice versa. Therefore, according to most of the reviewed studies, photographs, which are easily obtainable, are considered essential for the initial diagnosis to achieve optimal results. Several advantages of resin infiltration have been described in the included studies. In addition to enhancing aesthetics, resin infiltration can improve the mechanical properties of teeth affected by enamel hypomineralization. According to Crombie et al., 2014 [6], resin infiltration in MIH lesions results in an increase in the Vickers microhardness, a finding further supported by long-term enamel behavior observations [37]. Nogueira et al. [31] demonstrated that resin infiltration reduced the risk of enamel fracture and positively influenced the structural integrity of affected teeth. Regarding enamel reinforcement, infiltration is more effective than fluoride varnish application is and significantly reduces post-eruptive breakage by 6.1% [31]. Although the infiltration of hypomineralised enamel may be limited due to the unpredictable pattern, the benefits of the resin-infiltration technique include increased enamel hardness and flexural strength and decreased tooth hypersensitivity. Hypersensitivity improves after the first resin application and is maintained at subsequent follow-up visits [48]. However, ref. [23] claimed that some undesirable side effects, such as dental and gingival pain, soft-tissue damage, and a bitter taste immediately after infiltration, can occur after treatment with the icon system (Icon®; DMG, Hamburg, Germany); however, these effects were not observed in any of the studies reviewed. Furthermore, the infiltrate resin has been described as a microinvasive material: it fills, strengthens and stabilizes demineralized enamel without sacrificing healthy tooth structure. There is no need to remove opacities by rotary instrumentation prior to infiltration. Advantages that can be directly transferred to the treatment of HMI lesions [13], also noted in clinical evaluations of enamel defects [43]. Considering that resin infiltration may have additional benefits for hypomineralised enamel such as reduced permeability and increased hardness and strength [27], further studies testing protocols with modified etching techniques and longer application times are required. The scarcity of articles and lack of consensus among the authors regarding the protocol for resin infiltration in hypomineralised anterior teeth led to the decision to collect all available studies on the subject, including those of lower quality in terms of the quality of scientific evidence, which is a weakness of this study. To obtain results with greater clinical applicability, clinical trials with standardized protocols for diagnosis and resin application are required. To achieve the best results with resin infiltration of hypomineralization defects in the anterior teeth, accurate diagnosis of the characteristics and depth of the lesion is necessary. Although resin infiltration improves the aesthetics and is well-accepted by families, possible modifications to adapt the protocol to the structural characteristics of MIH defects should be further explored. These modifications could include increased conditioning or etching time, longer solvent and infiltration resin application times, development of resins with greater penetrability, and combination with other materials for more predictable and reproducible results, as already suggested by studies exploring variable lesion morphology [30,49].

Recent evidence also supports alternative minimally invasive approaches for the management of enamel defects in paediatric patients. A randomized clinical trial by Scribante et al. [50] evaluated the remineralising effect of biomimetic hydroxyapatite in children and adolescents, demonstrating improvements in enamel quality and aesthetics. Although biomimetic hydroxyapatite acts through remineralisation rather than masking and pore infiltration, this approach represents a conservative, non-invasive strategy that may be considered complementary or alternative, particularly in cases where resin infiltration shows limited predictability. This review has several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. First, the number of available studies specifically addressing resin infiltration in MIH-affected anterior teeth was limited, and the included studies showed considerable heterogeneity in study design, diagnostic criteria, outcome measures, and follow-up periods [51,52].

In addition, differences in aesthetic assessment methods, ranging from qualitative photographic evaluations to quantitative colorimetric analyses, reduce comparability across studies and may introduce measurement bias. The inclusion of studies with lower methodological quality, although necessary due to the scarcity of evidence, further limits the strength of the conclusions. Although the risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa and PEDro scales and the certainty of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE approach, the overall certainty of evidence for the primary outcomes ranged from low to moderate. This is mainly due to methodological limitations of the included studies, small sample sizes, and short follow-up periods. Consequently, the conclusions of this review should be interpreted with caution. An important limitation of this study is the small number of studies included in the meta-analysis (n = 3), which reduces statistical power. In addition, the high heterogeneity observed across studies (I2 = 94–98%) limits the reliability and generalizability of the pooled estimates. These findings should therefore be interpreted with caution, and the quantitative results should be considered exploratory. The observed heterogeneity may be partially explained by differences in MIH severity, lesion characteristics, treatment protocols, outcome assessment methods, and follow-up duration among the included studies. Despite these limitations, the results have important implications for clinical practice, as they support resin infiltration as a minimally invasive option for improving the aesthetics and mechanical properties of hypomineralised anterior teeth when careful case selection is performed. From a policy perspective, the findings highlight the need for the development of standardized diagnostic and treatment protocols for MIH-related aesthetic defects. Future research should focus on well-designed randomized controlled trials with standardized outcome measures, longer follow-up periods, and protocol modifications tailored to the specific microstructural characteristics of MIH lesions, in order to improve predictability and strengthen the evidence base for clinical decision-making.

5. Conclusions

Based on the available evidence, resin infiltration can be considered a minimally invasive option for masking mild to moderate MIH-related anterior opacities, with acceptable short-term aesthetic outcomes. However, outcome predictability remains limited, and long-term evidence is insufficient. The most favorable clinical outcomes were observed following the initial resin infiltration, and the available evidence suggests that these results are generally maintained at short-term follow-up periods (3–6 months).

Clinical photography, digital image analysis, and transillumination represent affordable and non-invasive tools that may assist clinicians in objectively assessing lesion brightness, extent, and size, as well as the suitability of resin infiltration for masking white or creamy/white MIH opacities. Despite its therapeutic and aesthetic advantages and its conservative nature, the predictability of outcomes remains limited, and evidence regarding long-term stability is still insufficient. Therefore, further well-designed randomized clinical trials with longer follow-up periods are required before broader generalization of these results can be recommended.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16020593/s1, PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.-P. and M.D.C.-R.; methodology, M.C.-P. and M.D.C.-R.; software, M.Á.V.-R.; validation, M.C.-P. and M.D.C.-R.; formal analysis J.M.M.-C.; investigation, M.C.-P. and M.D.C.-R.; resources M.Á.V.-R.; data curation, J.M.M.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.C.-R.; writing—review and editing, M.C.-P.; visualization, M.Á.V.-R.; supervision, M.C.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon reasonable request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI | Central Incisor |

| LI | Lateral Incisor |

| C | Canine |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| EAPD | European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry |

| MIH | Molar Incisor Hypomineralization |

| UV | University of Valencia |

References

- Bekes, K.; Steffen, R.; Krämer, N. Update of the molar incisor hypomineralization: Würzburg concept. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2023, 24, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, M.; Wali Peeran, S.; Nahid Basheer, S.; Ali Peeran, S.; Anwar Naviwala, G.; Badiujjama Birajdar, S. Molar incisor hypomineralization: Prevalence, severity and associated aetiological factors in children seeking dental care at Armed Forces Hospital Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.T.; Alhasan, H.A.; Qari, M.T.; Sabbagh, H.J.; Farsi, N.M. Prevalence and risk factors of molar incisor hypomineralization in the Middle East: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 18, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brejawi, M.S.; Venkiteswaran, A.; Ergieg, S.M.; Sabri, B. Prevalence and severity of molar–incisor hypomineralisation in children in Fujairah, United Arab Emirates. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2023, 24, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, P.; Arima, L.; Abanto, J.; Bönecker, M. Maternal–child health indicators associated with developmental defects of enamel in primary dentition. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 44, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crombie, F.A.; Manton, D.J.; Palamara, J.E.A.; Zalizniak, I.; Cochrane, N.J.; Reynolds, E.C. Characterisation of developmentally hypomineralised human enamel. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, A.; Silva, J.; Elfrink, C.; Lygidakis, N.A.; Mariño, R.J.; Weerheijm, K.L.; Manton, D.J. Molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) training manual for clinical field surveys and practice. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerheijm, K.; Duggal, M.; Mejare, I. Judgement criteria for molar-incisor hypomineralisation in epidemiologic studies. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2003, 4, 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Kilpatrick, M.; Swain, V.; Munroe, R.; Hoffman, M. Transmission electron microscope characterisation of molar-incisor-hypomineralisation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 3187–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neboda, C.; Anthonappa, P.; King, M. Tooth mineral density of different types of hypomineralised molars: A micro-CT analysis. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambetta-Tessini, K.; Mario, R.; Ghanim, A.; Adams, G.; Manton, J. Validation of QLF-D in demarcated hypomineralised lesions quantification. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2017, 8, e12259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preusser, E.; Ferring, V.; Wleklinski, C.; Wetzel, E. Prevalence and severity of molar incisor hypomineralization in a region of Germany. J. Public. Health Dent. 2007, 67, 148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, S.; Zorba, O.; Atalay, A.; Özcan, S.; Demirbuga, S.; Pala, K.; Percin, D.; Ozer, F. Effect of resin infiltration on enamel surface properties and Streptococcus mutans adhesion to artificial enamel lesions. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34, 25–30, Erratum in Dent. Mater. J. 2016, 35, 333.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S.; Meyer-Lueckel, H. Masking of labial white spot lesions by resin infiltration. Quintessence Int. 2009, 40, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 statement: Updated guideline for systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210716121605id_/www3.med.unipmn.it/dispense_ebm/2009-2010/Corso%20Perfezionamento%20EBM_Faggiano/NOS_oxford.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Brescia, V.; Montesani, L.; Fusaroli, D.; Docimo, R.; Di Gennaro, G. Management of enamel defects with resin infiltration: 2-year retrospective study. Children 2022, 9, 1365. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, E.Y.; Jeong, T.S.; Kim, J.W. Evaluation of resin infiltration for masking labial white spot lesions. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2011, 21, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghawe, S.; Raslan, N. Management of permanent incisors affected by Molar-Incisor-Hypomineralisation (MIH) using resin infiltration: A pilot study. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 25, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElBaz, G.; Mahfouz, S. Efficacy of two treatments for masking MIH white spot lesions. Egypt. Dent. J. 2017, 63, 2147–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE guidelines: Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Sutton, A.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Terrin, N.; Jones, D.R.; Lau, J.; Carpenter, J.; Rücker, G.; Harbord, R.M.; Schmid, C.H.; et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athayde, G.D.S.; Reis, P.P.G.D.; Jorge, R.C.; Americano, G.C.A.; Fidalgo, T.K.S.; Soviero, V.M. Masking anterior MIH opacities and esthetic perception in children: RCT. J. Dent. 2022, 123, 104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, R.; Thakur, S.; Singhal, P.; Chauhan, D.; Jayam, C.; Jain, T. Concealment effect of resin infiltration in grade I MIH. J. Conserv. Dent. 2018, 21, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. Esthetic evaluation of resin infiltration for MIH treatment. J. Prev. Treat. Stomatol. Dis. 2021, 29, 689–694. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, J.; Graham, A.; Rodd, H.D.; Albadri, S.; Parekh, S.; Somani, C.; Hosey, M.T.; Taylor, G.D. Molar incisor hypomineralisation: Teaching and assessment across the undergraduate dental curricula in the UK. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 34, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhennawy, K.; Manton, D.J.; Crombie, F.; Zaslansky, P.; Radlanski, R.J.; Jost-Brinkmann, P.G.; Schwendicke, F. Structural, mechanical and chemical evaluation of molar-incisor hypomineralization-affected enamel: A systematic review. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2017, 83, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, C.; Hasmun, N.N.; Elcock, C.; Lawson, J.A.; Vettore, M.V.; Rodd, H.D. Making white spots disappear! Do minimally invasive treatments improve incisor opacities in children with molar-incisor hypomineralisation? Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, M.; Westland, S.; Ndokaj, A.; Nardi, G.M.; Guerra, F.; Ottolenghi, L. In-vivo colour stability of enamel after ICON® treatment at 6 years of follow-up: A prospective single center study. J Dent. 2022, 122, 103943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murri Dello Diago, A.; Cadenaro, M.; Ricchiuto, R.; Banchelli, F.; Spinas, E.; Checchi, V.; Giannetti, L. Hypersensitivity in Molar Incisor Hypomineralization: Superficial Infiltration Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, V.K.C.; Mendes Soares, I.P.; Fragelli, C.M.B.; Boldieri, T.; Manton, D.J.; Bussaneli, D.G.; Cordeiro, R.D.C.L. Structural integrity of MIH-affected teeth after treatment with fluoride varnish or resin infiltration: An 18-Month randomized clinical trial. J. Dent. 2021, 105, 103570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasmun, N.; Vettore, M.V.; Lawson, J.A.; Elcock, C.; Zaitoun, H.; Rodd, H.D. Determinants of children’s oral-health-related quality of life after esthetic treatment of enamel opacities. J. Dent. 2020, 98, 103372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençer, M.D.G.; Kirzioğlu, Z. A comparison of the effectiveness of resin infiltration and microabrasion treatments applied to developmental enamel defects in color masking. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, M.; Westland, S.; Guerra, F.; Corridore, D.; Vichi, M.; Maruotti, A.; Nardi, G.M.; Ottolenghi, L. Objective and subjective aesthetic performance of ICON® treatment for enamel hypomineralization lesions in young adolescents: A retrospective single center study. J. Dent. 2018, 68, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfelice, E.B.; Heck, A.S.; Bittencourt, H.R.; Weber, J.; Burnett, L.H., Jr.; Spohr, A.M. Short-term masking effect of resin infiltrant on mild MIH. Oper. Dent. 2024, 49, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti, L.; Dello Diago, M.; Silingardi, A.; Spinas, G. Superficial infiltration to treat hypomineralised enamel defects: 12-month follow-up. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost Agents 2018, 32, 1335–1338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marouane, O.; Manton, D.J. Influence of lesion characteristics on resin infiltrant application time: Pilot study. J. Dent. 2021, 115, 103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jälevik, B. Prevalence and diagnosis of molar-incisor hypomineralisation: Systematic review. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2010, 11, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garot, E.; Rouas, P.; Somani, C.; Taylor, G.D.; Wong, F.; Lygidakis, N.A. An update of the aetiological factors involved in molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Luengo, S.; Feijóo-García, G.; Miegimolle-Herrero, M.; Gallardo-López, N.E.; Caleya-Zambrano, A.M. Prevalence and clinical presentation of molar incisor hypomineralisation among a population of children in the community of Madrid. BMC Oral. Health 2024, 24, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhayri, S.L.; Alhassani, S.L.; AbdelAleem, N.A. Resin infiltration for esthetic improvement of dental fluorosis: Case report. Cureus 2024, 16, e72493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S.; Meyer-Lueckel, H.; Kielbassa, A.M. Resin infiltration of natural caries lesions. J. Dent. Res. 2007, 86, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, M.; Atlan, A.; Vennat, E.; Tirlet, G.; Attal, J.P. White enamel defects: Diagnosis and anatomopathology. Int. Orthod. 2013, 11, 139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, S.; Chen, T.; Crombie, F.; Manton, D.J.; Silva, M. The Impact of Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation on Children and Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doméjean, S.; Ducamp, R.; Léger, S.; Holmgren, C. Resin infiltration of non-cavitated caries lesions: Systematic review. Med. Princ. Pract. 2015, 24, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, J.; Dong, X.; Qian, J.; He, J.; Qu, X.; Lu, E. A systematic review of visual and instrumental measurements for tooth shade matching. Quintessence Int. 2012, 43, 649–659. [Google Scholar]

- Knösel, M.; Eckstein, A.; Helms, H.J. Durability of esthetic improvement following Icon resin infiltration of multibracket-induced white spot lesions. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 144, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanthathas, K.; Willmot, D.R.; Benson, P.E. Differentiation of developmental vs. post-orthodontic white lesions using image analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2005, 27, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.; Emerenciano, N.G.; Moda, M.D.; Silva, Ú.; Fagundes, T.C.; Danelon, M.; Cunha, R.F. Treatment of molar-incisor hypomineralization: A case report of 11-year clinical follow-up. Oper. Dent. 2023, 48, 121b–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scribante, A.; Cosola, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Genovesi, A.; Battisti, R.A.; Butera, A. Clinical and technological evaluation of the remineralising effect of biomimetic hydroxyapatite in a population aged 6 to 18 years: A randomized clinical trial. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Planells, P.; Acevedo, A. Impact of molar incisor hypomineralization on oral health-related quality of life in children. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 16, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Neta, N.B.; Moura, L.F.A.D.; Cruz, P.F.; Moura, M.S.; Paiva, S.M.; Martins, C.C.; Lima, M.D.D.M.D. Impact of molar-incisor hypomineralization on oral health-related quality of life in schoolchildren. Braz. Oral. Res. 2016, 30, e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.