Featured Application

As shown in the introduction to this article, there are few studies that combine research on mechanical and recycling properties. The research we describe may therefore motivate further studies in this area in response to the pursuit of sustainable development in product design.

Abstract

In order to comply with the principle of sustainable development in product design, in addition to the mechanical properties of products, recycling properties should also be taken into account at the early stages of design. This paper explores the interplay between mechanical and recycling properties in product design in order to achieve a compromise between these design aspects. The research included typical metrics used to evaluate a product for its mechanical and recycling properties. The tests were carried out on a lap connection made in four variants: as a two-bolt, three-bolt, two-rivet and three-rivet connection. It was demonstrated that the stiffness of bolted connections is significantly lower compared to equivalent riveted connections. On the other hand, using three rivets instead of two in a connection yields better results in terms of load-bearing capacity compared to a similar increase in the number of fasteners in a bolted connection. The results demonstrate the impact of material structure of components and dismantling operations on the financial performance of the recycling process in relation to the assessment of recycling aspects in product design.

1. Introduction

Product design (PD) is a complex process and requires multi-faceted conceptual modelling [1]. This is particularly evident in the case of advanced products manufactured in mechanical engineering [2,3,4]. Taking environmental issues into account in PD is crucial to focusing efforts on sustainable development. These efforts, known as eco-design [5], address environmental aspects in two general ways.

The first way relies on a life cycle approach, including Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Life Cycle Engineering (LCE), which allows for a comprehensive assessment of the environmental and economic impacts at every stage of a product or system’s life cycle—from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal [6,7,8]. LCA helps identify high-carbon stages, enabling designers to prevent the spread of impact and optimise sustainability performance.

The second way is a quantitative assessment of PD variants with special measures. There are a lot of suggestions for these measures in the literature. Sodhi et al. [9] came up with the Unfastening Effort Index (UFI), which estimates the total effort needed to disconnect different types of fasteners. Vanegas et al. [10] defined product disassembly time as the sum of six categories of disassembly related tasks. Martínez Leal et al. [11] developed a product recyclability index that aggregates compatibility, diversity and recyclability of materials. Dostatni [12] and Dostatni et al. [13] proposed another measure, based on aggregating the diversity of materials and connections regarding the recycling target. de Aguiar et al. [14] propounded a set of indexes that are divided into two groups—disassembly and material recycling.

In the PD process, in addition to the need to consider the recycling of product components at the end of their life cycle [15,16,17,18], typical design, manufacturing and operational aspects also need to be considered [19,20,21,22,23]. The aim is to optimise processes to guarantee quality and safety standards for components with the least possible impact on the environment. One of the strategies being implemented is the introduction of new materials and their combinations. In this context, the connections between different components are of great importance, as they affect the weight, mechanical properties and production costs of the structures manufactured [24,25]. At the same time, designing for disassembly is one of the proposed solutions, and fasteners are one of the factors that have the greatest impact on product disassembly. An example model that allows to determine which of several alternatives meets the requirements for assembly, in-use, servicing and disassembly is shown by Jeandin and Mascle [26]. Wang et al. [27], on the other hand, developed a method for planning selective disassembly sequences that takes destructive operations into account to improve product recyclability and operational efficiency.

One of the primary types of detachable connections between components in products are bolted connections. Their strength can vary significantly depending on the assembly method [28,29,30]. Therefore, developing a concept for the configuration of such connections is an important stage in their design. Other basic connections used in PD, but which are not detachable, are riveted connections. The selection of assembly methods during the PD stage is becoming increasingly crucial, among other things, for the sustainable recycling of high-purity metals due to existing recycling practices [31,32,33]. Although other methods of combining components in a way that allows them to be disassembled are also used, these two groups of connections (i.e., bolted and riveted connections) are most chosen (compare with [34,35,36]).

There are numerous publications on design, modelling, calculation and testing of the mechanical properties of bolted and riveted connections. A considerable number of these are summarised, for example, in the latest literature reviews or extensive introductions to articles devoted to this subject [37,38,39,40,41,42].

Conversely, very few articles have been published recently on the recycling of bolted and riveted connections and products created using such connections. Kreilis and Zeltins [43] described the behaviour of repurposed construction components with reconditioned bolted connections under cyclic and limit loads. The implementation of bolted connections for the assembly, disassembly and reuse of lightweight external walls has been demonstrated by Kitayama and Iuorio [44]. Liu et al. [45] conducted 3 tests on the dismantling of a fully sized frame construction composed of bolt−and–ball connections. Their research revealed that the recycling rates of structural components cycles were 100%, 98.62% and 92.9%, respectively. After three cycles, the failure rate of high-strength bolts used was 16.56%. Dai et al. [46] suggested a system of detachable beam-to-beam connections to allow for the reuse of their components. Soo et al. [47,48] examined the influence of connection technology on the recyclability of end-of-life vehicles, considering bolted connections present in them. LCA was also carried out to evaluate the environmental impact of recycling different types of aluminium scrap from this type of vehicle with varying levels of contamination. The results were then used to develop eco-design guidelines aimed at improving the quality and increasing the quantity of recycled aluminium. The influence of interleaving made of recycled polystyrene nanofibres on the quasi-static properties of carbon-to-carbon composite bolted and hybrid adhesive-bolted connections under tensile load was assessed by Tınastepe et al. [49].

The problem of recycling aluminium sheets joined with self-piercing rivets is addressed in [50,51,52]. Whereas steel rivets employed in typical self-piercing riveting are separated from the aluminium alloy sheets during recycling, this is not required for aluminium alloy rivets. The connected sheets and rivets are recycled directly, as they are formed from the same material. LCA model and a life cycle cost assessment model for automotive components connected by welding, bonding and riveting techniques are discussed in [53]. Here, the environmental and cost impacts of the chosen technique were looked at based on energy use and material flows. Optimising the recycling process for roof edge profiles with shape memory alloy fasteners is covered in [54]. Matsui et al. [55] proposed fibre-reinforced thermoplastic rivets, which are easy to recycle, for creating grass fibre-reinforced plastic connections.

A flexible system for the remanufacturing of electric vehicle batteries based on human–robot collaboration and a neural network algorithm, which aims to solve the problems associated with the uncertain process of dismantling and remanufacturing in the recycling of electric vehicle batteries, has been proposed by Yin et al. [56]. The design of such batteries involves, among other things, bolted and riveted connections, the presence of which has been taken into account in the system. Gaye et al. [57] have published a proposal for another information system to support decision-making on optimal recycling, for example in the aviation sector, where components are connected by both bolts and rivets.

The review [58] confirmed that there are insufficient comparisons of different technologies for combining components made of different materials in the literature. The studies presented therein mainly refer to mechanical aspects rather than economic ones. Furthermore, recycling aspects and life cycle analysis are not sufficiently addressed in the literature [59]. Therefore, there is insufficient data to select the appropriate combining technique, which would allow recommendations to be made to designers. To fill this gap, our article examines the relationships between mechanical and recycling properties of selected types of connections.

The aim of the article was to investigate how changing the number of fasteners in a connection affects the recycling and mechanical properties of the connection, and whether these properties vary concurrently. As a product to be considered, an example of a connection made once as a bolted connection and once as a riveted connection was selected. The research focused on verifying the equivalence of various structural designs for these connections in terms of different design aspects (i.e., mechanical and recycling). Computer-Aided Design (CAD) [60,61,62] and Finite Element Method (FEM) calculations [62,63,64] were used as engineering tools in the preparation of the article.

The presented article differs significantly from our previous publications. In [18], an approach to assessing the recyclability of products using the Recycling Product Model (RPM) was described. However, recycling analysis was not combined there with mechanical analysis. Both mechanical and recycling analyses have already been considered in [59]. Nevertheless, this article extends the research described in [59] to models with a variable number of fasteners and subjected to shear forces.

The originality of the presented research stems from the combination of mechanical and recycling analyses during the development of new products using bolted and/or riveted connections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Tested Connections

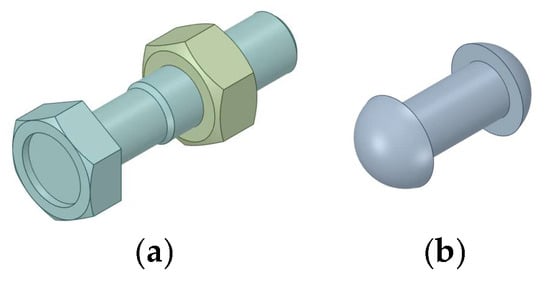

The tested assemblies were composed of two plates connected with M10 bolts (ISO 4015 M10 × 40 [65]) mounted with clearance and appropriate nuts (ISO 4032 M10 [66]) or solid round-head rivets with a diameter of 10 mm (DIN 124–A 10 × 34 [67]) mounted without clearance [68,69]. The dimensions of each plate are 100 mm × 100 mm × 10 mm. Selected connections made using two or three fasteners are shown in Figure 1, while solid models of fasteners are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

View of the analysed connection variants: (a) Connection using 2 bolts (Variant 1a); (b) Connection using 3 bolts (Variant 1b); (c) Connection using 2 rivets (Variant 2a); (d) Connection using 3 rivets (Variant 2b).

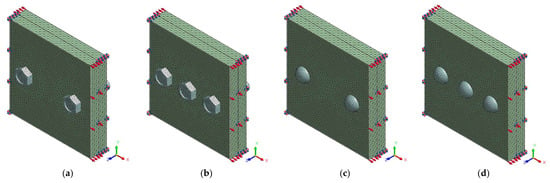

Figure 2.

Solid models of the fasteners: (a) Bolt-nut unit; (b) Round head rivet.

Both the plates and rivets were made of S275N (1.0490) structural steel [70]. The bolts and nuts, on the other hand, were made of C45 (1.0503) non-alloy steel [71] and treated to achieve mechanical properties of classes 8.8 and 8, respectively [72,73,74].

2.2. Finite Element Modelling Method

FEM calculations were performed by means of the Midas NFX 2023 R1 system (MIDASoft, Inc., New York, NY, USA). The model components were assigned to the materials specified in Section 2.1, the properties of which are summed up in Table 1.

Table 1.

Material properties of the connection models [75,76].

The High-Speed Tetra Mesher [77] was applied to construct the meshes for specific models. To enhance the contact quality between the connected elements, a mesh with varying density was applied to separate parts. Nevertheless, the side length of the finite element did not exceed 2.5 mm in any case.

Since the research in this article did not focus on a thorough analysis of changes in bolt and rivet forces during initial loading of the connection and under operating condition, no initial loading of fasteners was implemented in the models. Furthermore, the precise clamping stress value in riveted connections is commonly not known [78], and experimental studies would be required to determine it [79]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the clamping stresses in rivets are not as substantial as for pre-tensioned bolts. Bolt clamping was modelled by including contact connections between the bolt heads and the plate BH, and between the nuts and the plate N. Likewise, rivet clamping was modelled by including contact connections between the corresponding rivet heads and the plates.

‘General’ contact elements were applied between the plates, whereas ‘Welded’ contact elements were applied between the other pairs of parts to be connected [77]. These include the following pairs: bolt head—plate BH; nut—plate N; bolt—nut; upper rivet head—plate BH; lower rivet head—plate N; and rivet shanks—connected plates.

Assumed values of the ‘General’ contact elements parameters are as follows [80,81]:

- Normal stiffness coefficient of 10;

- Tangential stiffness coefficient of 1;

- Static friction coefficient of 0.14.

The use of ‘Welded’ contact elements prevented the parts from displacing relative to each other [81].

Mesh parameters for the assumed variants of connections are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mesh parameters for the assumed connection variants.

Discrete models of individual connection variants, together with a demonstration of how they are constrained and loaded, are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Discrete models of the connection: (a) Variant 1a; (b) Variant 1b; (c) Variant 2a; (d) Variant 2b.

In all cases, the models were constrained by removing all degrees of freedom in the nodes located on the outer surfaces of the plates (the constraints are marked in blue and pink) and loaded with shear forces (marked with red arrows).

The calculation process was divided into two stages. In the first stage, the stiffness of the connection was examined for each of its variants. In this case, it was assumed that the cross-section of a single bolt and a single rivet could be approximated to 25π mm2, and it was assumed that the permissible shear stresses for both bolts and rivets were 140 MPa. Then, based on the shear strength of the bolts/rivets, the shear force Fs was determined to be 7π kN for two fasteners and 10.5π kN for three fasteners. The shear force was applied in 10 steps each time.

In the second stage, the load-bearing capacity of the connection was examined, i.e., the maximum shear force that the connection can transfer in each of its variants was determined. In the analysis of riveted connections, the strength of the connection against surface pressure was omitted, because in the case of rivets whose shank diameter is smaller than the thickness of the connected plates multiplied by 1.6, as is the case here, the decisive criterion is shear strength [82]. The calculations were performed using the Nonlinear Static Analysis module with a geometrical non-linearity setting [59].

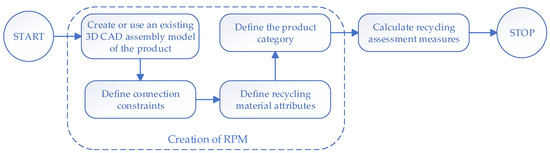

2.3. Method of Applying the Recycling Product Model

The quantitative assessment of a product’s recyclability involves a wide range of input data. It includes elements such as the type and number of connections or the recyclability of the materials used in the product. Some authors propose manual analysis of the product to assess these attributes [83]. Standard 3D CAD models do not represent these attributes to the full extent necessary for automatic assessment. For this reason, RPM was used to assess recyclability. RPM [18] extends the standard 3D CAD assembly model with a set of attributes necessary for product recycling assessment. The type and number of connections are described by connection constraints, which are a functional representation of all connections used in the product. Material recyclability attributes are implemented as an extension of the standard 3D CAD material library. These elements (connection constraints and material recycling attributes) together with the product category define RPM of the product [18]. RPM reflects the recycling properties of a product and enables the direct calculation of recycling assessment measures. The RPM creation process is presented in Figure 4, and detailed information on RPM can be found in [18].

Figure 4.

RPM creation process as the input data for recycling assessment measures.

In order to perform a quantitative assessment of the recyclability of the variants evaluated in this study (Figure 1), RPM was defined for all variants. It was assumed that all threaded connections would be dismantled. The dismantling time assessment was estimated based on a set of measurements of threaded connection dismantling operations. In the case of variants with riveted connections, no disassembly will be carried out due to the uniformity of the materials of the connections and the connected parts. The definitions of connection restrictions are presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 3.

Connection constraints and model dismantling attributes in Variant 1a.

Table 4.

Connection constraints and model dismantling attributes in Variant 1b.

Table 5.

Connection constraints and model dismantling attributes in Variant 2a.

Table 6.

Connection constraints and model dismantling attributes in Variant 2b.

The recycling assessment of the variants was based on two elements: a financial analysis of the recycling process and a quantitative measurement of PD from a recycling perspective.

The profit from recycling components is calculated using the following formula:

where mp is the mass of the component [kg]; cr is the unit material recycling profit [currency unit (c.u.)/kg].

The cost of recycling operations is estimated using the following formula:

where t is the dismantling time [s]; l is the unit labour cost [currency unit (c.u.)/h].

The sum of the profits from all recycled components and the cost of all recycling operations gives the total profit from recycling, calculated according to the formula:

For the purposes of the study unit material recycling profits were obtained from the recycling company [84]. It was assumed that the unit labour cost, due to the skills required to carry out the dismantling operation, is based on the minimum renumeration per hour in Poland [85].

A quantitative assessment of PD from a recycling perspective was carried out using the Total Type of Fastener Index (Total TFI), calculated as:

where is the value for the i-th connection used in the product for i = 1, 2, 3, …, n.

is a real number between 1 and 4 that reflects the difficulty of dismantling a connection of a given type. A higher TFI value reflects greater difficulty in dismantling. This measure was proposed by de Aguiar et al. [14] and is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

TFI values for typical connections.

The product category has been set as ‘Default’ for all variants analysed. The recycling assessment of the connection variants was conducted in the Autodesk Inventor 3D CAD system, version 2021, with an add-in enabling the definition of RPM and the calculation of recycling assessment indicators [18].

3. Results

3.1. FEM Calculation Results

In the case of stiffness analysis, the comparison of calculation results for different connection variants was performed on the basis of the following magnitudes:

- Average displacement of the plates in the x-axis due to force Fs—dpx;

- Shear stiffness of the connection—ks;

- Maximum shear stresses in the connection model—σs.

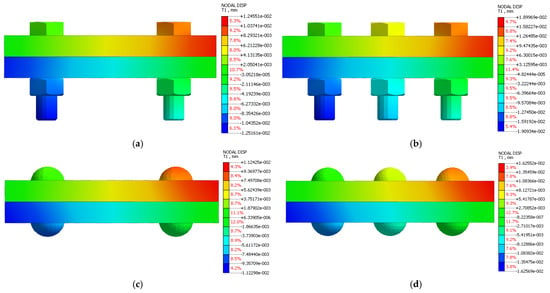

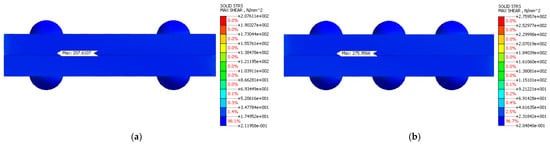

The average displacement of the plates in the x-axis under the influence of the shear force was computed as the arithmetic mean of the displacements at all nodes located on the surfaces to which the shear force was applied. In order to highlight the differences in the distribution of displacements for individual connection variants, Figure 5 shows maps of displacements for individual connection variants under the influence of force Fs.

Figure 5.

Displacement maps of the connection under the influence of force Fs obtained for: (a) Variant 1a; (b) Variant 1b; (c) Variant 2a; (d) Variant 2b.

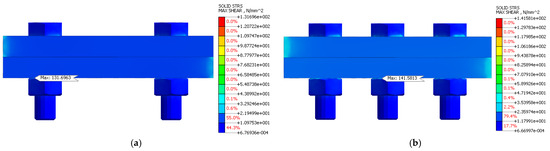

Figure 6 and Figure 7 shows the shear stress maps for individual connection variants under the influence of force Fs.

Figure 6.

Shear stress maps of the connection under the influence of force Fs obtained for: (a) Variant 1a; (b) Variant 1b.

Figure 7.

Shear stress maps of the connection under the influence of force Fs obtained for: (a) Variant 2a; (b) Variant 2b.

The stiffness of the connection was identified based on the equation:

The values of the compared magnitudes calculated for different connection variants are presented in Table 8. Based on these results, it is possible to confirm the inherently superior stiffness properties of riveted connections in comparison with bolted connections, as also evidenced, for instance, in [59,86].

Table 8.

Specified stiffness properties of the connection variants.

The deformations occurring in riveted connections are smaller than in bolted connections. In none of the cases did the maximum shear stresses exceed the shear strength values for the materials used (see Table 1).

In the second stage, the load-bearing capacity of the connection was examined, i.e., the maximum shear force Fs max that the connection can transfer in each of its variants was determined. The values obtained for this force are compiled in Table 9.

Table 9.

Specified maximum shear forces for the connection variants.

Since the fasteners tested in individual connection variants were made of different materials (see Table 1), the load-bearing capacities of these connections should only be compared with regard to a specific type of fastener. In the case of the riveted connection with two rivets, the force Fs max was 29 kN, and in the case of the same connection with three rivets, this force increased by approx. 13.8%. In contrast, in the case of the two-bolt connection, the force Fs max reached 125 kN, and in the case of the same connection with three bolts, this force amounted to approx. 3.2% more.

3.2. Product Recycling Properties

Profits from material recycling generally depend on material diversity and the relationship between material recycling unit profits. For variants with higher material diversity (1a and 1b), the material recycling profit is on average 30% higher than for variants without material diversity (2a and 2b). This is also evident from the relationship between material recycling unit profits—the material unit profit for bolts and nuts is about 5 times higher than the material unit profit for plates. The cost of dismantling slightly compounds the profits from materials, but does not significantly change the profitability of recycling for individual connection variants. This is due to the low amount of work required to carry out dismantling operations in the case of connections according to Variants 1a and 1b. Variants without dismantling operations (2a and 2b) are still less profitable in comparison to variants with dismantling operations (1a and 1b). The financial results of the recycling process are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Financial results of the recycling process.

The theoretical overall difficulty of dismantling the examined connection variants is expressed by the Total TFI values, which are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Total TFI values for Variants 1a to 2b.

For variants with more dismantling operations (2a and 2b), the Total TFI value is significantly higher than for variants with less problematic dismantling operations (1a and 1b). This reveals an inverse relationship between theoretical overall difficulty and the financial results of the dismantling process.

4. Discussion

Owing to the clearance between the bolts and the holes in the connected plates, the stiffness of bolted connections was substantially reduced compared to the equivalent riveted connections. For two fasteners positioned in line with the direction of the shear force, the relative difference in the connection stiffness was nearly 13.8%. In contrast, for three fasteners positioned in line with the direction of the shear force, this difference increased to 19.5%. This is also confirmed by the greater displacements under the influence of force Fs in the bolted connection variants compared to the riveted connection variants (Figure 5).

The direct contact between rivets and plates in riveted connection models resulted in higher maximum shear stresses compared to corresponding bolted connections (Figure 6 and Figure 7). An increase in these stresses of approximately 57.6% was observed for connections with two fasteners and almost 95% for connections with three fasteners.

Assessing the results of the load-bearing capacity analysis of individual connection variants, it can be concluded that the use of three rivets instead of two resulted in a significant increase in the maximum shear force destroying the connection by approx. 13.8%. Adding a third bolt to the connection did not produce the same effect. The maximum destructive shear force for the connection with three bolts increased by only approx. 3.2% compared to the connection with two bolts.

The final financial results of the recycling process, represented by the Total recycling profit, are a combination of income from the sale of dismantled components and the labour required for dismantling. For the variants analysed, the variants without dismantling operations were on average 60% less profitable than the variants with dismantling operations. Furthermore, recycling connections in the three-fastener variant is 33.3% more cost-effective than recycling connections in the two-fastener variant, regardless of the type of fastener.

A comparison of the results of mechanical and recycling analyses provides some guidance for designers of bolted and riveted connections. Taking into account the results of stiffness and load-bearing capacity analyses of individual connection variants, it should be concluded that, wherever reasonable, it is more advantageous to use riveted connections than bolted ones. However, considering the results of the analysis of connection variants in terms of their recyclability, it is more advantageous to use bolted connections as representatives of detachable connections.

In order to merge the benefits of bolted and riveted connections, one could explore the possibility of creating a hybrid connection using both fastener types (bolts and rivets). An analysis of such connections was attempted, for instance, in [87].

In the study presented, two limitations can be highlighted. The first one relates to the ignoring of factors such as the influence of the preload of fasteners on the strength of the connection [88,89] or fatigue from external loads [90]. The second one relies on not including the energy aspects of the recycling process. It was assumened that recycling operations do not involve any energy consumption. This assumption may not be fufilled, especially for operations conducted with the use of equipment requiring power supply.

5. Conclusions

Finite element analysis has indicated that the stiffness of bolted connections is substantially reduced compared to equivalent riveted connections because of the loose fit of bolts in the plate holes and the tight fit of rivets in the plate holes. This is particularly evident in the greater displacements observed in models of the connection with bolts. Thus, in terms of stiffness, better parameters are obtained for riveted connections. However, it should be remembered that for these connections (due to the assembly method, including the type of fit used), there are greater shear stresses. Therefore, attention should be paid to the appropriate selection of material for rivets in this case.

An additional advantage of riveted connections over bolted connections was observed during the load-bearing capacity analysis. Using three rivets instead of two in a connection yields much better results in terms of load-bearing capacity compared to a similar increase in the number of fasteners in a bolted connection.

In view of the above, the analysis of the stiffness and load-bearing capacity of the individual connection variants shows that it is more advantageous to use riveted connections than bolted ones. Conversely, analysing the connection variants in terms of their recyclability leads to the opposite conclusions. The rivet connection variants were significantly less cost-effective than the bolted connection variants. However, regardless of the type of fastener, recycling connections in the three-fastener variant is more cost-effective than recycling connections in the two-fastener variant.

RPM can be applied mainly at two stages of the product life cycle. The first stage is PD, during which the future properties of the product can be represented and evaluated. The second stage is the end-of-life stage, during which various variant of product dismantling can be analysed.

The overall benefit of the presented research results is the proposal to combine mechanical and recycling analyses when creating new products using bolted and/or riveted connections. As part of the extension of the research, the optimisation of the position of fastener may be integrated into discussions on improving the mechanical properties of the connection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.G. and J.D.; methodology, R.G. and J.D.; software, R.G. and J.D.; validation, R.G. and J.D.; formal analysis, R.G. and J.D.; investigation, R.G. and J.D.; resources, R.G. and J.D.; data curation, R.G. and J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G. and J.D.; writing—review and editing, R.G. and J.D.; visualisation, R.G. and J.D.; supervision, J.D.; project administration, R.G.; funding acquisition, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted with support from statutory activity financed by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (0613/SBAD/4940).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this paper:

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCE | Life Cycle Engineering |

| PD | Product design |

| RPM | Recycling Product Model |

| TFI | Type of Fastener Index |

| UFI | Unfastening Effort Index |

References

- Chen, Z.; Wan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Valera-Medina, A. A knowledge graph-supported information fusion approach for multi-faceted conceptual modelling. Inf. Fusion 2024, 101, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzejda, R. Modelling Nonlinear Multi-Bolted Connections: A Case of Operational Condition. In Proceedings of the 15th International Scientific Conference ‘Engineering for Rural Development 2016’, Jelgava, Latvia, 25–27 May 2016; pp. 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone, A.G.; Massei, M.; Gotelli, M.; Ferrari, R.; De Paoli, A.; Giovannetti, A.; Nguyen, V.P. Digital twin modeling for machine vision testing in autonomous systems. In Modelling and Simulation for Autonomous Systems; Mazal, J., Fagiolinii, A., Vasik, P., Pacillo, F., Bruzzone, A., Pickl, S., Stodola, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 14615, pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, M.; Kurylo, J.; Dang, P.H. Camera based AI models used with LiDAR data for improvement of detected object parameters. In Modelling and Simulation for Autonomous Systems; Mazal, J., Fagiolinii, A., Vasik, P., Pacillo, F., Bruzzone, A., Pickl, S., Stodola, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 14615, pp. 287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Diakun, J.; Dostatni, E. End-of-life design aid in PLM environment using agent technology. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2020, 68, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN ISO 14040; Environmental Management, Life Cycle Assessment, Principles and Framework. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2009.

- PN-EN ISO 14044; Environmental Management, Life Cycle Assessment, Requirements and Guidelines. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2009.

- Hauschild, M.Z.; Herrmann, C.; Kara, S. An integrated framework for Life Cycle Engineering. Procedia CIRP 2017, 61, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, R.; Sonnenberg, M.; Das, S. Evaluating the unfastening effort in design for disassembly and serviceability. J. Eng. Des. 2004, 15, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, P.; Peeters, J.R.; Cattrysse, D.; Tecchio, P.; Ardente, F.; Mathieux, F.; Dewulf, W.; Duflou, J.R. Ease of disassembly of products to support circular economy strategies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Leal, J.; Pompidou, S.; Charbuillet, C.; Perry, N. Design for and from recycling: A circular ecodesign approach to improve the circular economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostatni, E. Recycling assessment measures implemented in the system. In Ecodesign of Products in CAD 3D Environment with the Use of Agent Technology; Dostatni, E., Ed.; Publishing House of Poznan University of Technology: Poznan, Poland, 2014; pp. 89–93. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Dostatni, E.; Diakun, J.; Grajewski, D.; Wichniarek, R.; Karwasz, A. Multi-agent system to support decision-making process in design for recycling. Soft Comput. 2016, 20, 4347–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aguiar, J.; de Oliveira, L.; da Silva, J.O.; Bond, D.; Scalice, R.K.; Becker, D. A design tool to diagnose product recyclability during product design phase. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakun, J.; Dostatni, E.; Rojek, I.; Rybacki, P. Recycling-oriented analysis of domestic vacuum cleaner. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2198, 012061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Iuorio, O. Disassembly and reuse of structural members in steel-framed buildings: State-of-the-art review of connection systems and future research trends. J. Archit. Eng. 2023, 29, 03123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilavantar, S.S.; Suthar, S.; Chaitanya, B.; Chiranth, A.; Ravindra, R. Sustainability by reverse joints in steel structures (Demountable modular shear connection). Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2023, 319, 549–580. [Google Scholar]

- Diakun, J. Recycling Product Model and its application for quantitative assessment of product recycling properties. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, S.; Zmarzły, P. Influence of raceway waviness on the level of vibration in rolling-element bearings. Bull. Polish Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2017, 65, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozdrzykowski, K.; Grządziel, Z.; Grzejda, R.; Stępień, M. Determination of geometrical deviations of large-size crankshafts with limited detection possibilities resulting from the assumed measuring conditions. Energies 2023, 16, 4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, M.; Kurylo, J.; Braun, J.; Berger, G.S.; Mendes, J.; Lima, J. Using LiDAR data as image for AI to recognize objects in the mobile robot operational environment. In Optimization, Learning Algorithms and Applications; Pereira, A.I., Mendes, A., Fernandes, F.P., Pacheco, M.F., Coelho, J.P., Lima, J., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1982, pp. 118–131. [Google Scholar]

- Osipowicz, T. Evaluation of the environmental and operating parameters of a modern compression-ignition engine running on vegetable fuels with a catalytic additive. Catalysts 2025, 15, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipowicz, T.; Grzejda, R. Influence of wear of precision pair components in modern fuel injectors on the operating and environmental performance of a compression-ignition engine. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2025, 22, 12614–12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Fang, H.; Li, B.; Wang, F. Stability analysis and full-scale test of a new recyclable supporting structure for underground ecological granaries. Eng. Struct. 2019, 192, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, F.; Palaia, D.; Ambrogio, G. Energy consumption and CO2 emissions of joining processes for manufacturing hybrid structures. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeandin, T.; Mascle, C. A new model to select fasteners in design for disassembly. Procedia CIRP 2016, 40, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Gu, P. Selective disassembly planning for the end-of-life product. Procedia CIRP 2017, 60, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachowski, B.; Gutkowski, W. Effect of damaged circular flange-bolted connections on behaviour of tall towers, modelled by multilevel substructuring. Eng. Struct. 2016, 111, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszak, P. Prediction of the durability of a gasket operating in a bolted-flange-joint subjected to cyclic bending. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 120, 105027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzejda, R.; Parus, A. Health assessment of a multi-bolted connection due to removing selected bolts. FME Trans. 2021, 49, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schaik, A.; Reuter, M.A. The use of fuzzy rule models to link automotive design to recycling rate calculation. Miner. Eng. 2007, 20, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabah, S.; Laefer, D.F.; Hong, L.T.; Huynh, M.P.; Le, J.-L.; Martin, T.; Matis, P.; McGetrick, P.; Schultz, A.; Shemshadian, M.E.; et al. Introduction of the intermeshed steel connection—A new universal steel connection. Buildings 2020, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaleiro, M.; Conde, B.; González-Gaya, C.; Barros, B. Removable, reconfigurable, and sustainable steel structures: A state-of-the-art review of clamp-based steel connections. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.B.; Remmerswaal, J.A.M.; Brezet, J.C.; van Schaik, A.; Reuter, M.A. A simulation model of the comminution–liberation of recycling streams: Relationships between product design and the liberation of materials during recycling. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2005, 75, 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M.; van Schaik, A. Thermodynamic metrics for measuring the “sustainability” of design for recycling. JOM 2008, 60, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.; Shao, L. Non-traditional mechanical connection mode and its application in lightweight of automobile. World Sci. Res. J. 2018, 4, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Grzejda, R. New method of modelling nonlinear multi-bolted systems. In Advances in Mechanics: Theoretical, Computational and Interdisciplinary Issues, 1st ed.; Kleiber, M., Burczyński, T., Wilde, K., Gorski, J., Winkelmann, K., Smakosz, Ł., Eds.; CRC Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Masendorf, L.; Wächter, M.; Esderts, A.; Otroshi, M.; Meschut, G. Service life estimation of self-piercing riveted joints by linear damage accumulation. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2021, 44, 1637–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.A.N.; Trabasso, L.G. Riveting-induced deformations in metallic aeronautical structures—A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 135, 1089–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yue, Q.; Chen, H. Comparison of non-destructive testing methods of bolted joint status in steel structures. Measurement 2025, 242, 116318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbel, A.; Manitcaia, V.; Machniewicz, T. Influence of rivet material and squeeze force on the riveting process and residual stresses in riveted joints used in aircraft structures. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2025, 73, e154721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Gkantou, M.; Nikitas, G.; Ferentinou, M.; Bras, A.; Riley, M. A review of recent developments in structural elements of modular steel building systems. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreilis, J.; Zeltins, E. Reuse of Steel Structural Elements with Bolted Connections. In Proceedings of the 6th International Scientific Conference ‘Research for Environment and Civil Engineering Development 17’, Jelgava, Latvia, 2–3 November 2017; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama, S.; Iuorio, O. Using bolted connections for the construction, de-construction and reuse of lightweight exterior infill walls: Experimental study. Archit. Struct. Constr. 2024, 4, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Chen, Z. Damage analysis and mechanical performance evaluation of frame structures in recycling. Structures 2024, 66, 106906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Yang, J.; Lam, D.; Sheehan, T.; Zhou, K. Experiment and numerical modelling of a demountable steel connection system for reuse. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 198, 107534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, V.K.; Compston, P.; Doolan, M. The influence of joint technologies on ELV recyclability. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, V.K.; Peeters, J.; Paraskevas, D.; Compston, P.; Doolan, M.; Duflou, J.R. Sustainable aluminium recycling of end-of-life products: A joining techniques perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tınastepe, M.T.; Kaybal, H.B.; Ulus, H.; Erdal, M.O.; Çetin, M.E.; Avcı, A. Quasi-Static tensile loading performance of bonded, bolted, and hybrid bonded-bolted carbon-to-carbon composite joints: Effect of recycled polystyrene nanofiber interleaving. Compos. Struct. 2023, 323, 117445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, Y.; Kato, T.; Mori, K. Aluminium alloy self-pierce riveting for joining of aluminium alloy sheets. Key Eng. Mater. 2009, 410–411, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.-H.; Porcaro, R.; Langseth, M.; Hanssen, A.-G. Self-piercing riveting connections using aluminium rivets. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2010, 47, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Abe, Y. A review on mechanical joining of aluminium and high strength steel sheets by plastic deformation. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2018, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, J.M.; McKinstry, K.C.; Baek, C.; Horvath, A.; Dornfeld, D. Multi-objective analysis on joining technologies. In Leveraging Technology for a Sustainable World; Dornfeld, D.A., Linke, B.S., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann, C.; Fleczok, B.; Lygin, K.; Meier, H. Optimizing the Recycling Process of a Roof Edge Profile by Using Shape Memory Alloy Connecting Elements. In Proceedings of the ASME 2014 Conference on Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems, Newport, RI, USA, 8–10 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, T.; Matsushita, Y.; Matsumoto, Y. Mechanical behavior of GFRP connection using FRTP rivets. Materials 2021, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Xiao, J.; Wang, G. Human-Robot Collaboration Re-Manufacturing for Uncertain Disassembly in Retired Battery Recycling. In Proceedings of the 5th World Conference on Mechanical Engineering and Intelligent Manufacturing, Ma’anshan, China, 18–20 November 2022; pp. 595–598. [Google Scholar]

- Gaye, K.; Gardoni, M.; Coulibaly, A. System of Decision-Making Assistance for the Recycling Manufactured Products. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–10 March 2016; pp. 844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, J.; Weeber, M.; Boehner, J.; Steinhilper, R. Assessment strategies for composite-metal joining technologies—A review. Procedia CIRP 2016, 50, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakun, J.; Grzejda, R. Product design analysis with regard to recycling and selected mechanical properties. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miatliuk, K.; Lukaszewicz, A.; Siemieniako, F. Coordination method in design of forming operations of hierarchical solid objects. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–17 October 2008; pp. 2724–2727. [Google Scholar]

- Łukaszewicz, A.; Miatliuk, K. Reverse engineering approach for object with free-form surfaces using standard surface-solid parametric CAD system. Solid. State Phenom. 2009, 147–149, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszak, P.; Grzejda, R. Symmetric and asymmetric semi-metallic gasket cores and their effect on the tightness level of the bolted flange joint. Materials 2025, 18, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenica, P.; Powałka, B.; Grzejda, R. Assessment of modal parameters of a building structure model. Springer Proc. Math. Stat. 2016, 181, 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, M.; Kosiuczenko, K. Evaluation of TAERO UGV structural collision resistance using FEM analysis. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2025, 73, e153431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN ISO 4015; Fasteners, Hexagon Head Bolts with Reduced Shank (Shank Diameter ≈ Pitch Diameter), Product Grade B. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- PN-EN ISO 4032; Fasteners, Hexagon Regular Nuts (Style 1). Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2024.

- DIN 124; Steel Round Head Rivets, Nominal Diameters from 10 mm to 36 mm. German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2011.

- Correia, J.A.F.O.; da Silva, A.L.L.; Xin, H.; Lesiuk, G.; Zhu, S.-P.; de Jesus, A.M.P.; Fernandes, A.A. Fatigue performance prediction of S235 base steel plates in the riveted connections. Structures 2021, 30, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Zhang, Q.; Xiong, L.; Li, J.; Bu, Y.; Bao, Y. A unified evaluation method for fatigue resistance of riveted joints based on structural stress approach. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 160, 106871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 10025-3; Hot Rolled Products of Structural Steels, Part 3: Technical Delivery Conditions for Normalized/Normalized Rolled Weldable Fine Grain Structural Steels. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2019.

- PN-EN ISO 683-1; Heat-Treatable Steels, Alloy Steels and Free-Cutting Steels, Part 1: Non-Alloy Steels for Quenching and Tempering. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2018.

- PN-EN 1515-1; Flanges and Their Joints, Bolting, Part 1: Selection of Bolting. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2002.

- PN-EN ISO 898-1; Mechanical Properties of Fasteners Made of Carbon Steel and Alloy Steel, Part 1: Bolts, Screws and Studs with Specified Property Classes, Coarse Thread and Fine Pitch Thread. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2013.

- PN-EN ISO 898-6; Mechanical Properties of Fasteners, Part 6: Nuts with Specified Proof Load Values, Fine Pitch Thread. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2003.

- EN 1.0490 (S275N) Non-Alloy Steel. Available online: https://www.makeitfrom.com/material-properties/EN-1.0490-S275N-Non-Alloy-Steel (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- EN 1.0503 (C45) Non-Alloy Steel. Available online: https://www.makeitfrom.com/material-properties/EN-1.0503-C45-Non-Alloy-Steel (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Midas NFX Manuals and Tutorials. Available online: https://midassupport.jitbit.com/helpdesk/KB/View/32637163-midas-nfx-manuals-and-tutorials (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- de Jesus, A.M.P.; da Silva, A.L.L.; Correia, J.A.F.O. Fatigue of riveted and bolted joints made of puddle iron—A numerical approach. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 102, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonetti, D.; Maljaars, J.; Pasquarelli, G.; Brando, G. Rivet clamping force of as-built hot-riveted connections in steel bridges. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2020, 167, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesik, W. Effect of the machine parts surface topography features on the machine service. Mechanik 2015, 88, 587–593. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzejda, R.; Perz, R. Compressive strength analysis of a steel bolted connection under bolt loss conditions. Commun. Sci. Lett. Univ. Žilina 2022, 24, B319–B327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoć, A.; Spałek, J. Fundamentals of Machine Design, Volume 1. Structural Calculations, Tolerances and Fits, Connections; Scientific Publishing House PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Desai, A.; Mital, A. Evaluation of disassemblability to enable design for disassembly in mass production. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2003, 32, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrap Metal Purchase. Available online: https://www.ekosylwia.pl/cennik (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 12 September 2024 on the Minimum Remuneration and the Minimum Hourly Rate in 2025. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20240001362 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Satheesh Kumar, K.V.; Selvakumar, P.; Jagadeeswari, R.; Dharmaraj, M.; Uvanshankar, K.R.; Yogeswaran, B. Stress analysis of riveted and bolted joints using analytical and experimental approach. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 42, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski, K. The Bearing Capacity of Hybrid Bolted and Riveted Joints in Steel Bridge Structures. In Proceedings of the XIV International Conference on Metal Structures, Poznan, Poland, 16–18 June 2021; pp. 342–348. [Google Scholar]

- Zacal, J.; Pavlik, J.; Kunzova, I. Influence of shape of pressure vessel shell on bolt working load and tightness. MM Sci. J. 2021, 6, 5448–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacal, J.; Folta, Z.; Struz, J.; Trochta, M. Influence of symmetry of tightened parts on the force in a bolted joint. Symmetry 2023, 15, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, P.; Curtarello, A.; Maiorana, E.; Pellegrino, C. A review of the fatigue strength of shear bolted connections. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2019, 19, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.