Abstract

The Xiannüshan Fault Zone, located in the southwestern part of the Huangling Anticline within the Three Gorges Reservoir area of Hubei Province, is one of the largest and most complex faults in the region. The geological structures of its different segments vary significantly. Previous studies have primarily focused on the northern segment and often relied on single geophysical methods, which are insufficient for detailed characterization of the entire fault zone. Based on existing geological data, field reconnaissance results, and the geological characteristics of different segments of the fault zone, we employed multiple geophysical methods for a varied investigation: shallow seismic reflection in the northern segment; a combination of waterborne seismic exploration and microtremor survey in the middle segment; and high-density resistivity in the southern segment. The integrated approach revealed the spatial extent, fault geometry, and activity characteristics of each segment, confirming that the Xiannüshan Fault Zone is a pre-Quaternary structure dominated by thrusting. The findings provide a critical scientific basis for regional seismic hazard assessment and disaster mitigation planning, while also establishing a technical framework with significant practical application value for detailed fault characterization in geologically complex environments.

1. Introduction

The Xiannüshan Fault Zone is located in the southwestern part of the Huangling Anticline. Composed of several faults striking NW 340–350° (nearly north–south), it has a total length of approximately 90 km and is one of the largest and most structurally complex active faults in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Early studies divided the Xiannüshan Fault Zone into three segments: the northern segment (Xiannüshan Fault in the narrow sense), the middle segment (Duzhenwan Fault), and the southern segment (Qiaogou Fault) [1,2]. In recent years, enhanced microseismic activity around the Xiannüshan Fault Zone has drawn considerable attention to the relationship between this fault and local seismicity. However, previous investigations have mainly concentrated on the northern segment of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone, addressing the northward extension of the fault across the Yangtze River [3,4], reservoir-induced seismicity and associated geological hazards (e.g., landslides and collapses) [5,6,7,8], as well as analyses of fault gouge materials [9,10]. Relatively few studies have examined the deep and shallow structure at the northern end of the fault or the activity of the middle and southern segments, leaving a gap in the regional seismic hazard knowledge. Therefore, investigating the fault characteristics and tectonic development of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone is particularly important for regional earthquake preparedness and mitigation.

In recent years, geophysical detection technologies have become indispensable tools for fault investigation [11,12,13,14]. Commonly used techniques in engineering [15,16,17] include the high-density resistivity method [18,19,20], shallow seismic reflection [21,22,23], and microtremor survey [24,25,26,27]. Both single-method applications [28,29,30,31] and integrated geophysical approaches [13,32,33] have been successfully applied to fault investigations worldwide, yielding reliable results. However, geological and topographic conditions, as well as the surrounding environment, often constrain the effectiveness of geophysical methods. Consequently, no single method can fully meet all investigation needs, making it essential to select appropriate techniques according to the local geological setting.

In summary, based on available geological and geophysical data [4,34,35], this study selects appropriate geophysical exploration methods according to the specific characteristics of different segments of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone. The study area in the northern segment is located in the urban area, with relatively flat terrain and partial bedrock outcrops. Ground hardening, industrial and civil electrical interference limit the effectiveness of electrical and microtremor surveys. Thus, we adopted the active-source shallow seismic reflection method. The study area in the middle segment features intense terrain dissection, alternating distribution of land and water areas, and a large research scope. Due to restrictions on the deployment of vibrator trucks and the implementation of long-line electrical surveys, we adopted microtremor surveys in land areas. We also deployed a controlled marine seismic line in water areas to comprehensively constrain the strike and spatial location of the fault. The study area in the southern segment is dominated by mountainous terrain, with shorter survey lines, making shallow seismic reflection and microtremor methods less applicable. Therefore, we use the high-density resistivity method to detect the fault structure.

2. Regional Geological Tectonic Overview

The Xiannüshan Fault Zone lies within Yichang City, Hubei Province, at the eastern margin of the Western Hunan–Hubei Fold Belt and the southwestern part of the Huangling Anticline. The fault zone starts from Yuyangguan in Wufeng County in the south, extends northward through Qiaogou, Duzhenwan (Changyang County), Qinglinkou, and Huaqiaochang (Zigui County), then via Laolinhe and Zhouping, and finally pinches out in Triassic Jialingjiang Formation limestone north of Huangkou [36]. Previous studies [3,6] indicate that the formation and evolution of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone were controlled by multistage tectonic movements. During the early Yanshan orogeny, the basic framework of the fault zone was established; in the later Yanshan stage, intense differential uplift and subsidence led to rift basin development along the fault and deposition of Cretaceous red beds in those basins. The fault zone remained active during the Himalayan period (Late Cenozoic) through inherited reactivation. Owing to different tectonic positions, the northern, middle, and southern segments exhibit distinct deformation styles [37]: compressional–torsional, thrust (compressional), and extensional–torsional, respectively. Since the Late Cenozoic, regional uplift has reduced differential movement on the fault zone, but it still maintains a certain level of activity. Regionally, structures trend predominantly NW and near EW. Folds are well-developed, especially on the southwestern flank of the Huangling Anticline, with most fold axes trending EW. The Xiannüshan Fault Zone runs mostly through mountainous bedrock terrain, with its easternmost part entering the basin-margin of a Meso-Cenozoic basin.

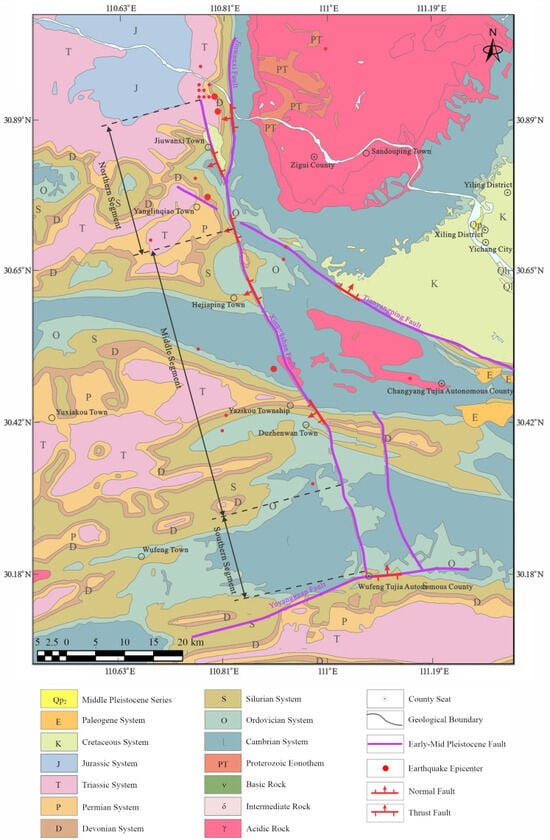

The Xiannüshan Fault Zone has exhibited distinct activity since the Neotectonic Period. Fault scarps and triangular facets are arranged in rows along the fault zone, and landslides and collapses are widespread. Marked differences exist in topography, planation surfaces, and river terraces on both sides of the fault, and the longitudinal gradients of riverbeds also vary significantly [38]. The fault zone can be divided into three segments from north to south (Figure 1), each with distinct characteristics as follows:

Figure 1.

Geological Tectonic Map of the Study Area.

- (1)

- Northern segment (Xiannüshan Fault in the narrow sense, also referred to as the Huangkou Fault) [2]: This approximately 20 km long segment extends from Fengchuiya north of Huangkou (Zigui County) southward through Zhouping and Laolinhe to Majiawan. It transects Upper–Middle Cambrian to Permian strata of the Paleozoic and Cretaceous strata of the Mesozoic. Near Huangkou, the fault strikes NW 330–350°, dipping SW at 35–60°. Along this segment, Paleozoic strata are thrust over the Cretaceous red beds. The fault zone, 2–5 m wide on average (locally exceeding 10 m), is composed of schistose tectonite, mylonitic breccia, and cataclasite. The wall rocks on both sides are steeply tilted, with dips around 80°.

- (2)

- Middle segment (Duzhenwan Fault) [1]: This approximately 50 km long segment extends from Jinzhutou (Zigui County) in the north through Huaqiao, Qinglinkou, and Duzhenwan, to Huixi (Changyang County) in the south. It strikes NW 335–340°. North of Wanggaoshan, the fault dips southwest, whereas to the south, the fault plane becomes vertical or dips northeast. The Duzhenwan Fault comprises a series of sub-parallel fault strands of varying lengths and scales, forming an incomplete imbricate structure. The fault breccia zone, several to tens of meters wide, mainly consists of cataclasite and porphyroclastic rock. Analyses of horizontal slickensides on the fault surface and a 3–4 km dextral offset of the Changyang Anticline indicate that the fault is characterized by primarily dextral (right-lateral) strike-slip motion with an extensional component.

- (3)

- Southern segment (Qiaogou Fault) [1]: This approximately 12 km long segment extends from Jiuliping (Changyang County) northward to Yuyangguan (Wufeng County) in the south. It strikes 340–350° and has a nearly vertical fault plane. South of Liujiaping, the strike gradually swings to NE 10–20°, dipping east at 50–80°. The fault breccia zone averages approximately 5 m in width and widens to approximately 20 m near Qiaogou. It consists mainly of mylonite, breccia, and cataclasite, with a thin schistose tectonite layer exposed locally. Foliation within the fault rocks trends approximately 10–15° oblique to the fault strike, and striations plunging 47° S indicate dextral (right-lateral) strike-slip motion, with the western block moving northward and the eastern block southward. Further south toward Daponao, the fault trace narrows and terminates.

Seismic activity within the study area exhibits a significant spatial correlation with the Xiannüshan Fault Zone. Earthquakes are mainly concentrated along the northern segment of the fault zone, particularly in the Three Gorges Reservoir area and its surrounding regions. The epicenters of earthquakes are highly consistent with the detected traces of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone. The largest-magnitude earthquake in the study area was the M5.1 Longhuanguan Earthquake, which occurred in Zigui County on 22 May 1979, and its epicenter was also located near the northern segment of the fault zone [39,40].

3. Methodology

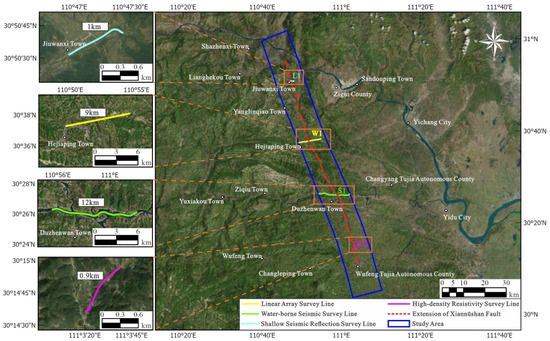

Integrating existing geological and geophysical information with field reconnaissance, nine geophysical survey lines were deployed along the Xiannüshan Fault Zone (Table 1). The lines were distributed in three representative areas (Figure 2) corresponding to the fault’s northern, middle, and southern segments. In the northern segment near Jiuwanxi Town (paved surface, gentle relief), three shallow seismic reflection profiles were arranged (L1, L2, XC3). In the middle segment near Zhangmulei Village and Hejiaping Town (restricted land access and wide river channel), one waterborne seismic profile (S1) and one microtremor linear-array profile (W1) were deployed. In the southern segment near Qiaogou Village, Wufeng County (steep topography, thick Quaternary cover), four high-density resistivity lines were established (GD1–GD4). All survey lines were oriented approximately perpendicular to the fault strike and adjusted to avoid man-made structures, ensuring various and systematic data acquisition.

Table 1.

Data of measuring line in the study area.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the survey line location.

3.1. Shallow Seismic Reflection Exploration

The shallow seismic reflection method relies on contrasts in elastic properties and density within subsurface formations. Artificially generated seismic waves are recorded to capture reflections from stratigraphic interfaces, allowing inference of subsurface structure and geometry, and delineation of concealed faults or layers, thereby meeting the objectives of seismic exploration [41,42,43].

For this shallow seismic reflection survey, a SmartSolo IGU-16HR seismograph system (Mianyuan Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) equipped with built-in 5 Hz DT-SOLO geophones was employed. Seismic energy was generated using a WTC5112TZY vibroseis (5-ton vibrator) (Beibei Petroleum Geophysical Special Vehicle Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Baoding, China); the sweep ranged from 10 to 110 Hz with a sweep duration of 12 s. On the line XC3, a 40 kg weight-drop hammer source was additionally used to enhance shallow reflections. Lines L1 and L2 adopted an asymmetric split-spread shooting geometry, while line XC3 employed single-ended shooting. The detailed acquisition parameters for each line are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of shallow seismic reflection acquisition.

The study processed the shallow seismic reflection data using Geogiga Seismic Pro. We first edited the shot gathers by removing bad traces, outliers, and first arrivals. We applied frequency, velocity, and one-dimensional filters to suppress surface waves, low-frequency noise, and linear interference, and to enhance reflection energy. We then performed refraction and residual static corrections to compensate for elevation effects and near-surface velocity heterogeneity. We applied deconvolution to improve temporal resolution. We conducted velocity analysis using velocity scans and semblance spectra to determine stacking velocities, which we used for normal moveout correction and stacking. After stacking, we applied f–x random noise attenuation and post-stack migration to correctly position reflectors and improve fault imaging.

3.2. Waterborne Seismic Exploration

The basic principle of waterborne seismic exploration is the same as that of shallow seismic reflection: a controlled seismic source is activated in water to generate seismic waves; as the waves propagate underwater and encounter interfaces with contrasts in acoustic impedance, reflections are produced. The reflected signals are received by a streamer cable towed behind the vessel, transmitted along the cable to the onboard recording system, and subsequently processed, analyzed, and interpreted to delineate underwater stratigraphic structures and geological bodies [44,45].

For the waterborne seismic survey, an HMS-620M dual electromagnetic air-gun system (Falmouth Scientific, Pocasset, MA, USA) was used as the seismic source, generating low-frequency acoustic signals between 70 and 700 Hz. The receiving system consisted of a Geometrics MicroEel 24 digital marine streamer (Geometrics, San Jose, CA, USA). Acquisition parameters for the S1 survey line are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Acquisition parameters of waterborne seismic survey.

The study the waterborne seismic data using GEOGIGA v10.0 seismic reflection software. We first organized the raw data by matching shot gathers with GPS positions, grouping valid segments by acquisition time, and removing records acquired off-line or during vessel turns. We established the correspondence between channel numbers and spatial positions and generated navigation tracks. Based on test lines, we defined the processing flow and parameters. We applied combined one- and two-dimensional filtering to suppress noise and enhance reflection signals. We performed velocity analysis using velocity scans and spectra, followed by normal moveout correction, deconvolution, multiple suppression, time-variant filtering, stacking, and post-stack migration. We applied depth-related amplitude compensation to generate time and depth sections. We then calculated trace coordinates and along-line distances, picked major reflection horizons, and converted time sections to depth using velocity constraints derived from borehole data and reflection waveform characteristics. This workflow produced the final interpreted waterborne seismic profiles.

3.3. Microtremor Survey

The microtremor survey method is based on the theory of stationary random vibration. Ambient microtremor signals (from natural or cultural sources) are recorded and processed to extract surface-wave dispersion curves (Rayleigh wave dispersion). By inverting these dispersion curves, the shear-wave velocity profile of the subsurface is obtained, and the stratigraphic structure of the subsurface soil layers can be inferred [46,47]. Common array configurations for microtremor surveys include linear, triangular, and T-shaped arrays; in this study, we adopted a flexible linear array arrangement.

A single-component nodal seismograph system (SmartSolo IGU-16HR, Calgary, AB, Canada) was employed for the microtremor survey to ensure high-resolution signal recording. The system operated in continuous mode. Detailed acquisition parameters for line W1 are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Microtremor survey acquisition parameter.

The study processed the microtremor data using the frequency–Bessel (F–J) transform to extract fundamental-mode Rayleigh-wave dispersion and invert near-surface S-wave velocity structures. We preprocessed the continuous records by removing the mean and trend and applying band-pass filtering to ensure signal stability. We segmented the data into 30 s windows and computed spatial cross-spectra between station pairs. We stacked the spectra to enhance surface-wave energy and improve spectral resolution. We then applied the F–J transform to obtain frequency–phase velocity energy spectra. To account for lateral heterogeneity, we constructed multiple subarrays with different apertures using a random partition strategy and stacked their dispersion spectra to balance high-frequency resolution and low-frequency penetration. We extracted fundamental dispersion curves using the DisperNet program and performed one-dimensional S-wave velocity inversion with a genetic algorithm, yielding an average shear-wave velocity structure down to approximately 800 m depth.

3.4. High-Density Resistivity Method

The high-density resistivity method is essentially an array-based electrical prospecting technique based on resistivity contrasts between rock and soil. By analyzing the distribution pattern of conduction currents in the subsurface when an electric field is applied, the method determines subsurface geological structures [48,49].

The high-density resistivity survey was conducted using a WGMD-9 high-density resistivity system (Chongqing Benteng Digital Control, Chongqing Benteng Digital Control Technology Institute, Chongqing, China) integrated with a WDA-1 multi-channel DC resistivity instrument and distributed cables. The system was powered by three 144 V battery packs. A tablet-controlled multi-channel switching unit automatically selected current injection and potential measurement electrodes. To minimize electrode contact resistance, salt water was poured at each electrode site and multiple electrodes were connected in parallel. The electrode configurations and acquisition parameters for the survey lines are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Survey line acquisition parameters.

The study preprocessed the electrical resistivity data by editing the records, identifying and removing bad data points, and checking electrode positions and elevation information to ensure data consistency. We used Surfer to plot apparent resistivity contour maps and profiles to examine data coverage, anomaly distribution, and potential noise. We then performed two-dimensional resistivity inversion using the ResIPy v3.5.5 software. We selected appropriate smoothing parameters and mesh discretization and applied iterative inversion until convergence. We evaluated the inversion results using residuals, RMS errors, and data–model fits to assess model stability. Finally, we interpreted resistivity anomalies by integrating the inversion profiles with regional geology, lithological resistivity characteristics, and shallow structural information, and delineated fault zones, fault gouge, and lithological boundaries.

4. Characterization Results

We acquired three shallow seismic reflection lines (L1, L2, XC3) in the northern segment of the Xiannüshan Fault, detecting three fault breakpoints (FP1-1, FP1-2, FP1-3). Among these, breakpoint FP1-3 is identified on line L2, with a burial depth of approximately 110 m. At this location, fault F1-3 exhibits the characteristics of a thrust fault, with an apparent dip direction to the west. Given the relatively lower imaging quality of line L2, this study primarily focuses on lines L1 and XC3.

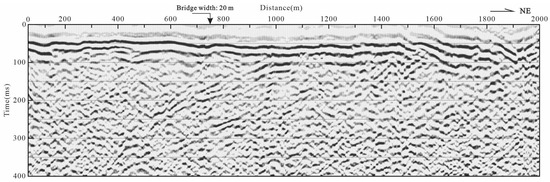

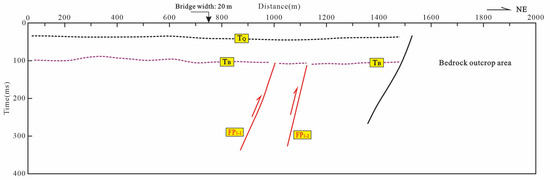

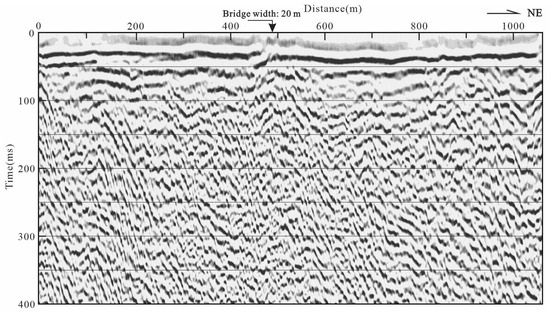

The seismic reflection profile of the L1 survey line is shown in Figure 3, while the corresponding interpreted profile is presented in Figure 4. Based on the reflection characteristics in Figure 3, a strong and continuous reflection corresponding to the base of the Cenozoic (labeled TQ) is clearly identifiable from 0 m to 1500 m along the profile. Beyond 1500 m, the reflections become disorganized, consistent with field observations of bedrock outcrops at the surface. Beneath the TQ horizon, a distinct bedrock reflector (labeled TB) is present; however, in the zone beyond 1500 m, the TB reflections are somewhat disrupted due to exposed bedrock. As illustrated in Figure 4, the TB reflector is vertically offset at approximately 990 m (two-way travel time 83.5 ms) and again at 1116 m (two-way travel time 91 ms) along the line, corresponding to interpreted fault breakpoints FP1-1 and FP1-2, respectively. Comprehensive analysis indicates that Fault F1-1 is a west-dipping thrust fault at FP1-1, displacing the TB horizon, with its upper breakpoint located at a depth of about 90.5 m. Likewise, Fault F1-2 is a west-dipping thrust fault at FP1-2, offsetting the TB horizon with an upper breakpoint at a depth of approximately 107.2 m. Neither fault offsets the TQ horizon near the surface; both terminate within the TB horizon and do not cut the base of the Quaternary deposits.

Figure 3.

Seismic reflection time profile of survey line L1.

Figure 4.

Depth-interpreted profile of survey line L1.

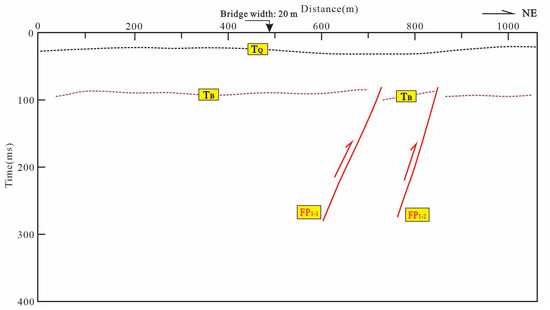

The XC3 survey line was designed as a supplementary line to line L1 to further investigate the fault structure identified on L1. A small-array hammer source was used for detailed imaging of the shallow anomaly zone. The seismic reflection profile of the XC3 survey line is shown in Figure 5, while the corresponding interpreted profile is presented in Figure 6. Similarly to line L1, a strong reflection corresponding to the base of the Cenozoic (TQ) is clearly visible across the entire profile, underlain by a distinct bedrock reflector (TB). Prominent pinch-outs and offsets of the TB reflection are observed near 730 m and 850 m along the line. Correlation with the L1 profile indicates that these offsets correspond to the same fault breakpoints FP1-1 and FP1-2 identified on L1.

Figure 5.

Seismic reflection time profile of survey line XC3.

Figure 6.

Depth-interpreted profile of survey line XC3.

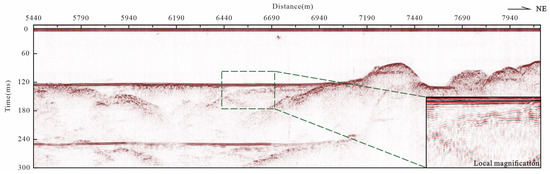

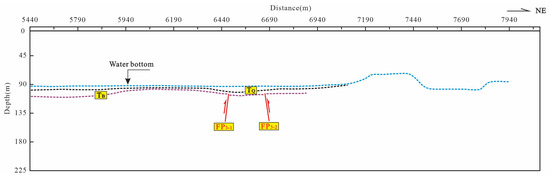

The waterborne seismic line S1, located in the middle segment of the study area, has a total length of 12.97 km, along which three fault breakpoints (FP3-1, FP3-2, and FP3-3) were identified. For interpretation and display purposes, the long profile was divided into five sections: 0–2740 m, 2740–5440 m, 5440–8100 m, 8100–10,840 m, and 10,840–12,980 m. Among these, breakpoint FP3-3 is located in the 8100–10,840 m sections. At this location, fault F3-3 exhibits the characteristics of a normal fault with an apparent dip direction to the west. Given the relatively low imaging quality of the 8100–10,840 m segment of the profile, this study focuses on the 5440–8100 m segment.

Figure 7 shows the seismic reflection time section for the 5440–8100 m portion of line S1, while the corresponding interpreted profile is presented in Figure 8. A strong reflector marking the base of the Cenozoic (TQ) is visible and is underlain by a distinct bedrock reflector (TB). The TB reflection is vertically offset at approximately 6476 m (two-way travel time 137 ms) and 6665 m (137 ms) along the profile, corresponding to fault breakpoints FP3-1 and FP3-2. Fault F3-1 is interpreted as a west-dipping thrust fault at FP3-1, displacing the TB horizon; its upper fault point lies approximately 11 m below the lake floor. Similarly, Fault F3-2 is a east-dipping thrust at FP3-2, with the upper fault point located 11 m below the lake bottom. Both faults offset the TQ reflector near the surface and cut the TB reflector at depth, but their upper terminations do not reach the Quaternary surface.

Figure 7.

Seismic Reflection Time Profile of Line S1 (5440–8100 m Segment).

Figure 8.

Depth Interpretation Profile of Line S1 (5440–8100 m Segment).

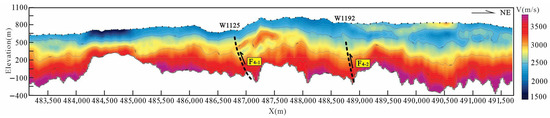

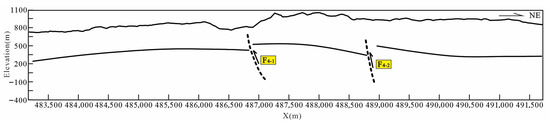

We deployed one microtremor array line (W1) in a key part of the middle segment of the Xiannüshan Fault where a vibroseis truck could not be used. The microtremor survey identified two fault-related anomalies (FP4-1 and FP4-2). Figure 9 shows the shear-wave velocity profile inverted from the microtremor data along line W1. Between horizontal positions 484,113 and 484,966 (in local coordinates), a low-velocity anomaly appears above 100 m depth, with shear velocities around 1605–1850 m/s. Field reconnaissance revealed that this section of the line lies near the Changyang High-Speed Railway Station and runs adjacent to the railway tracks. The high-frequency vibrations from passing trains have likely lowered the measured near-surface velocities and obscured low-frequency (deep-penetrating) signals, resulting in a shallower effective inversion depth in this area. Further along W1, near station W1125 (horizontal coordinate 486,440–487,340), the apparent shear-wave velocity of bedrock decreases laterally, indicating a discontinuity. We interpret a fault F4-1 here in Figure 10, expressed as a thrust fault dipping east. The upper portion of the fault is nearly vertical, and comprehensive analysis suggests this is the main fault of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone in this area. Near station W1192 (coordinate 488,750–489,000), another lateral velocity discontinuity is observed, with higher velocities on the east side. This is inferred to be Fault F4-2, a near-vertical, high-angle thrust fault dipping east. Analysis suggests that F4-2 is a secondary fault within the Xiannüshan Fault Zone.

Figure 9.

Inverted shear-wave velocity profile of survey line W1.

Figure 10.

Geological interpretation profile of survey line W1.

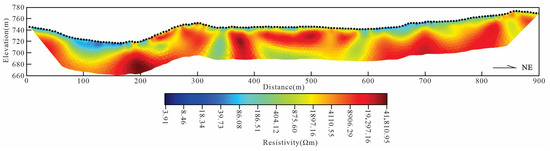

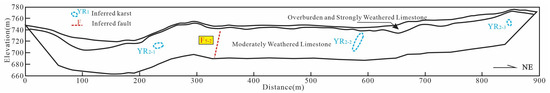

In the southern segment, we carried out four high-density resistivity survey lines (GD1–GD4), detecting four fault breakpoints (FP5-1, FP5-2, FP5-3, and FP5-4). Among these, the faults at breakpoint FP5-1 on line GD1 and breakpoint FP5-3 on line GD3 exhibit a west-dipping orientation. And the fault at breakpoint FP5-4 on line GD4 shows an east-dipping orientation. Although all these lines delineate the fault-related geological features along the southern segment of the Xiannüshan Fault, line GD2 provides the clearest imaging. Therefore, this study focuses primarily on the discussion of line GD2.

The inversion resistivity section of line GD2 is shown in Figure 11, while the corresponding integrated geological profile is presented in Figure 12. According to the inversion results, the effective inversion depth of line GD2 is approximately 80 m. Based on existing geological data, geological information can be assigned to the apparent resistivity section as follows: (1) The surface layer mainly consists of completely and strongly weathered limestone, with a few intermontane valleys covered by Quaternary deposits, exhibiting low apparent resistivity. The underlying bedrock is moderately weathered limestone, generally showing relatively high resistivity with values greater than 1500 Ω·m. (2) At distances of approximately 50 m, 315 m, and 670 m from the starting point of the survey line, zones of low apparent resistivity are observed, which are interpreted as three karst anomalies (YR2-1, YR2-2, and YR2-3). (3) At approximately 570 m from the starting point in Figure 11, the apparent resistivity displays a low-resistivity anomaly flanked by high-resistivity zones. As illustrated in Figure 12, this feature is interpreted as a fault (F5-2) dipping westward, with the upper fault point buried at a depth of approximately 15 m. This fault point is located along the strike direction of the southern segment of the Xiannüshan Fault.

Figure 11.

Inverted color map of survey line GD2.

Figure 12.

Integrated geological profile of survey line GD2.

5. Discussion

- (1)

- This study adopts a “segment-based optimal single-method” detection strategy, tailored to the geological and geomorphological differences in each segment of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone and the constraints of field implementation. On the premise of ensuring the detectability of key targets, this strategy reduces the low signal-to-noise ratio risk of unsuitable methods in complex sites. It also concentrates limited resources on the advantageous methods for each segment, thereby improving the field operability and cost-effectiveness. It should be emphasized that this strategy does not negate the positive role of multi-method co-line joint detection in improving detection accuracy and result reliability. Instead, it provides a more operationally feasible and cost-effective implementation path for concealed fault detection under complex geological conditions. Similar strategies have also been adopted in relevant studies worldwide: Mahmut G. Drahor [50] implemented differentiated geophysical detection schemes based on the specific detection tasks and site constraints of each survey line. Wang Zhihui [51] adopted a segmented research approach in their study area, considering differences in Quaternary overburden thickness, target detection depth, and resolution requirements. Luigi Piccardi [52] reasonably selected different geophysical detection methods according to on-site conditions. These studies indicate that “segment-based optimal selection” of geophysical detection methods, based on research objectives and site conditions, is an effective technical path with strong operability and high resource utilization efficiency.

- (2)

- Influenced by the “segment-based optimal single-method” strategy, this study did not implement joint detection with multiple methods on the same survey line. As a result, the research results lack direct cross-validation, which limits the constraint level of comprehensive interpretation to a certain extent. At the same time, factors such as local grounding conditions and human activity noise also affect data quality. For example, the electrical method has high contact resistance, and the microtremor dispersion energy is not concentrated enough. These issues may introduce uncertainties in the location and burial depth of fracture points. To quantitatively express the credibility of interpretations, this study classifies the reliability of fracture points into three levels: “Class A”, “ Class B”, and “ Class C”. This classification is carried out in accordance with the requirements of the Seismic Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China DB/T 93.3—2024 [53]. It comprehensively considers the fault imaging characteristics on stacked profiles, the systematicness of event dislocation, and the sufficiency of independent evidence such as geology and drilling. In comprehensive interpretation, we distinguish the constraint levels of different fracture points based on this classification.

- (3)

- Integrating the detection results of this study with previous research, the Xiannüshan Fault as a whole shows inherited characteristic of a pre-Quaternary fault. However, local weak reactivation may have occurred in the late stage. In the shallow seismic reflection data of the northern segment, there is no clear evidence that the fault cuts through the base of the Quaternary system. Subaqueous seismic reflection profiles reveal that the fault can offset interfaces such as TQ/TB. Even so, its upper endpoint lies approximately 11 m below the lake bottom and does not reach the Quaternary surface. This indicates that overall late-stage shallow activity of the fault is relatively weak. Previous studies [54,55] used fault gouge dating to determine the fault’s activity history. They proposed that the last relatively strong activity may have occurred during the Early–Middle Pleistocene, with the latest activity age around 150,000 years ago. Additionally, precise earthquake relocation in the reservoir area shows that earthquakes at 4–10 km depth are correlated with the fault structure. This suggests that intermittent responses may still occur in deep or local segments of the fault. Such responses could be triggered by regional stress evolution and reservoir water disturbance. Overall, the activity of the Xiannüshan Fault can be summarized by three key traits: it formed early, shows insignificant shallow activity, and may undergo deep-seated reactivation.

6. Conclusions

This study focuses on the Xiannüshan Fault Zone. We integrate existing geological data and field reconnaissance findings, and adopt targeted geophysical methods for different fault segments based on their specific topographic and environmental conditions. These methods include shallow seismic reflection, marine seismic reflection, microtremor survey, and high-density resistivity method. Through these approaches, we systematically detect and comprehensively interpret the near-surface and shallow-to-medium deep structures of the fault zone. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- By applying multiple geophysical methods segmentally, we obtained 9 detection profiles. We then selected 5 profiles with high imaging quality and reliable interpretation for in-depth analysis. Through this process, we identified multiple concealed fracture points, constrained their spatial locations, burial depth characteristics and geometric patterns, and summarized the relevant results in Table 6.

Table 6. Summary of fault breakpoints identified by different geophysical methods.

Table 6. Summary of fault breakpoints identified by different geophysical methods.

- (2)

- The fault in the northern segment exhibits typical compressional-thrust structural characteristics in shallow seismic reflection profiles. The fault plane terminates near the surface, with no obvious signs of cutting through loose overburden. This study is consistent with previous research and refines the understanding of the shallow structural characteristics of this fault segment.

- (3)

- The fault in the middle segment exhibits relatively complex structural styles in the results of marine seismic surveys and microtremor surveys. It may consist of multiple secondary faults, with local superposition of strike-slip or extensional components. Existing geophysical data provide constraints for understanding the multi-stage tectonic evolution of this fault segment.

- (4)

- In resistivity imaging, the fault in the southern segment generally exhibits a significant electrical contrast between the fault zone-related low-resistance anomalies and the high-resistance surrounding rocks. This indicates that the fault fracture zone still has identifiable structural responses in the near-surface area. Meanwhile, non-tectonic low-resistance anomalies such as karst are widely developed in the profiles. This reflects strong heterogeneity of shallow media in the southern segment, requiring fault identification to be distinguished from anomalies like karst bodies and interpreted comprehensively. From the perspective of electrical structure constraints, this study supplements the shallow structural information of the southern segment, providing further evidence for understanding the geometric characteristics and segmentation of the fault in this segment.

In summary, the Xiannüshan Fault Zone as a whole exhibits distinct segmented structural characteristics: the northern segment is dominated by compressional-thrust structures, the middle segment has complex structural styles, and the southern segment gradually attenuates. Existing geophysical evidence indicates that the fault zone is dominated by pre-Quaternary structures, with limited late-stage activity in the near-surface area. However, due to limitations in detection resolution and data coverage, the possibility of local deep reactivation cannot be completely ruled out. Overall, this study verifies the feasibility and effectiveness of segmentally selecting multiple geophysical methods to detect concealed faults under complex geological and environmental conditions. It enriches the understanding of the structural characteristics of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone, provides more reliable basic data for regional seismic hazard assessment and subsequent related research, and offers valuable references for future fault detection in similar complex geological environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and J.L.; methodology, S.L. and W.D.; software, C.J.; validation, S.L. and X.D.; formal analysis, C.J. and W.D.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, H.Z.; data curation, J.L., M.C. and Y.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and W.D.; visualization, C.J.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, C.J.; funding acquisition, S.L. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Comprehensive Location and Seismic Hazard Assessment Project of the Xiannüshan Fault Zone, Project No.: YCZ2011-202301-01F; Provincial Science and Technology Innovation Base and Platform Program, Grant Number: ZDJ2024-30; Large Earthquake Hypocenter Exploration Project under the Hubei Provincial Plan for Enhancing Earthquake Disaster Risk Monitoring Capacity, Project No.: HBYF-2025-C07013; Research grants from National Institute of Natural Hazards, Ministry of Emergency Management of China, Grant Number: ZDJ2024-30.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Song Lin, Cong Jin, Miao Cheng, Xiaohu Deng, Yanlin Fu and Hongwei Zhou were employed by the company Wuhan Institute of Earthquake Engineering Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhou, M.L.; Qin, X.L.; Feng, X.C. Several views on Xiannüshan fault zone. Crustal Deform. Earthq. 1984, 4, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.Z. A preliminary study on the segmental characteristics of Xiannüshang fault. Crustal Deform. Earthq. 1991, 11, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.X. Structural deformation analysis of Xiannüshan fault in the front region of Changjiang Three Gorges Engineering. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 1991, 18, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, M.F.; Chu, Q.Z.; Deng, Z.H.; Pan, B.; Zhang, C.H.; Zhou, Q. Tectonic landform and location of the northern end of Xiannüshan fault at the Three Gorges area. Seismol. Geol. 2012, 34, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.F.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, S.Y. Impoundment effect of Three Gorges Reservoir and influence on Xiannüshan fault zone. J. Geod. Geodyn. 2006, 26, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.F.; Wang, S.M.; Zhang, Y.M. Correlations between Xiannüshan active fault, reservoir-induced earthquakes and landslides located at head area of Three Gorges Reservoir. Yangtze River 2018, 49, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.W.; Lu, Y.Q.; Nie, J.; Teng, M.M.; Wang, X.L. Earthquake variation law of Xiannüshan and Jiuwanxi fault zones in Three Gorges Reservoir Area. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2021, 51, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.T.; Xu, C.P.; Li, H.O.; Yuan, J.L.; Xu, X.W.; Zhang, X.D.; Zhang, L.F. Intensive observation of reservoir-induced earthquakes in the Three Gorges of the Yangtze River and preliminary analysis of earthquake genesis. Seismol. Geol. 2010, 32, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.G.; Wu, S.R.; Yin, X.L. Fractal dimensions of fault gouges from the Xiannüshan Fault and its activity. Acta Geosci. Sin. 1999, 20, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, S.J. Fission track age of fault gouge in the Yangtze Three-Gorge Dam site. Chin. J. Geol. 2001, 36, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.C.; Li, P.; Jiang, C.X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X. Advances of the application of urban geophysical exploration methods in China. Prog. Geophys. 2023, 38, 1799–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Improta, L.; Ferranti, L.; De Martini, P.M.; Piscitelli, S.; Bruno, P.P.; Burrato, P.; Civico, R.; Giocoli, A.; Iorio, M.; D’Addezio, G.; et al. Detecting young, slow-slipping active faults by geologic and multidisciplinary high-resolution geophysical investigations: A case study from the Apennine seismic belt, Italy. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115, B11307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, D.; Carrasco, J.; Carrasco, P.; González, P.J. Imaging extensional fault systems using deep electrical resistivity tomography: A case study of the Baza fault, Betic Cordillera, Spain. J. Appl. Geophys. 2022, 202, 104673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.S.; Zhang, G.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ge, K. Application of combined electrical resistivity tomography and seismic reflection method to explore hidden active faults in Pingwu, Sichuan, China. Open Geosci. 2020, 12, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabàs, A.; Macau, A.; Benjumea, B.; Bellmunt, F.; Figueras, S.; Vilà, M. Combination of geophysical methods to support urban geological mapping. Surv. Geophys. 2014, 35, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.; Orlowsky, D.; Misiek, R. Exploration of Tunnel Alignment using Geophysical Methods to Increase Safety for Planning and Minimizing risk. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2010, 43, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F. Multi-geophysical approaches to detect karst channels underground: A case study in Mengzi of Yunnan Province, China. J. Appl. Geophys. 2018, 151, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Choi, J.-R.; Kim, B.; Kim, S.-S.; Lee, S.; Ha, S.; Lee, J.; Son, M. Geophysical investigation of the Quaternary paleo-earthquake evidence using ERT and MASW surveys: A case study along the Yangsan Fault, SE Korea. Eng. Geol. 2025, 359, 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Henk, A.; Buness, H.; Lehné, R.; Tanner, D.C. Multi-scale geophysical imaging of neotectonic fault activity in the northern Upper Rhine Graben, Germany. Near Surf. Geophys. 2025, 23, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, W.; Deng, X.H.; Zha, Y.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, M. Geophysical observation of typical landslides in Three Gorges Reservoir Area and its significance: A case study of Sifangbei landslide in Wanzhou District. Earth Sci. 2019, 44, 3135–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, Y.; Luo, D.G.; Fu, Y.L. Research on the fracture structure and activity of the Qinling Mountains thrust nappe system in western Hubei. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2020, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Lepine, P.; Gorman, A.R.; Prior, D.J.; Lukács, A.; Bowman, M.H.; Fan, S.; Robertson, A.; Lutz, F.; Eccles, J.D.; et al. Shallow seismic reflection imaging of the Alpine Fault through late Quaternary sedimentary units at Whataroa, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 2021, 64, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugin, A.J.M.; Pullan, S.E.; Hunter, J.A.; Oldenborger, G.A. Hydrogeological prospecting using P- and S-wave landstreamer seismic reflection methods. Near Surf. Geophys. 2009, 7, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Y. Mapping bedrock topography and detecting blind faults using the fundamental resonance of microtremor: A case study of the Pohang Basin, southeastern Korea. Geophys. J. Int. 2024, 238, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Xu, P.; Ling, S.; Du, J.; Xu, X.; Pang, Z. Application effectiveness of the microtremor survey method in the exploration of geothermal resources. J. Geophys. Eng. 2017, 14, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, Z.; Tang, M. Application of microtremor survey technology in a coal mine goaf. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Xu, P.; Qian, J.; Cao, L.; Du, Y.; Fu, Q. Frequency-Bessel transform based microtremor survey method and its engineering application. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.F.; Tao, P.F.; Xia, Y.M. Active faults and bedrock detection with super-high-density electrical resistivity imaging. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 5049–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Lin, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, M. Estimation of shallow shear velocity structure in a site with weak interlayer based on microtremor array. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalà, S.; Malehmir, A.; Hong, T.; Juhlin, C.; Lee, J.; Papadopoulou, M.; Brodic, B.; Park, S.; Chung, D.; Kim, B.; et al. Crustal-scale fault systems in the Korean Peninsula unraveled by reflection seismic data. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2022EA002464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.D.; Chen, L. Imaging of upper breakpoints of buried active faults through microtremor survey technology. Earth Planets Space 2024, 76, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.L.; Cao, C.H.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, Y. Study on application of comprehensive geophysical prospecting method in urban geological survey: Taking concealed bedrock detection as an example in Dingcheng District, Changde City, Hunan Province, China. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.J.; Xu, X.Q.; Geng, X.Y.; Liang, S.Q. An integrated geophysical approach for investigating hydro-geological characteristics of a debris landslide in the Wenchuan earthquake area. Eng. Geol. 2017, 219, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.S.; Yuan, J.R.; Gao, S.J. Seismicity anomaly in south Shandong Province and M L5.6 Cangshan earthquake. Crustal Deform. Earthq. 1997, 17, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, M.Z.; He, D.F.; Zhang, Y.Y. Tectonic evolution of Xiannüshan fault and its influence on hydrocarbon traps in Changyang anticline, Western Hubei fold belt. Pet. Exp. Geol. 2018, 40, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.W.; Li, C.A.; Zhou, J.Y. Isotope age determination study on activity of Xiannushan Fault etc in the Primary Three Gorges Reservoir area. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2005, 32, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.R. Study on the microstructures and deformational environment of Xiannushan Fault belt, east of Yangtze River gorges. Chin. J. Geol. 1994, 29, 220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.R.; Liu, Z.Z.; Qin, X.L.; Li, D.L. Study on the deformational structures and dynamic analysis of Xiannushan Fault zone in the Changjiang River Gorge area. Seismol. Geol. 1994, 16, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.H.; Chen, F.; Wan, Z.F.; Liao, W.L.; Wang, D. Focal mechanisms and seismogenic stress field of the earthquakes that occurred in the vicinity of the northern part of the Xiannvshan Fault, Three Gorges Area. Earth Sci. 2022, 47, 2410–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Zhang, L.F.; Wang, Q.L.; He, C.F. Study on seismic activity and static Coulomb stress change in the area near Xiannvshan-Jiuwanxi Fault zone. J. Geod. Geodyn. 2020, 40, 1044–1048+1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjwech, R.; Hongsresawat, S.; Chaisuriya, S.; Rattanawannee, J.; Kanjanapayont, P.; Youngme, W. Identification and Verification of the Movement of the Hidden Active Fault Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography and Excavation. Geosciences 2024, 14, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jin, C.; Luo, D.; Cai, Y.; Lin, S. Comprehensive geophysical measurement in seismic safety evaluation: A case study of East Lake High-Tech Development Zone, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana, H.; Taborik, P.; Valenta, J.; Bhat, F.A.; Flašar, J.; Štěpančíkova, P.; Khwaja, N.A. Detecting active faults in intramountain basins using electrical resistivity tomography: A focus on Kashmir Basin, NW Himalaya. J. Appl. Geophys. 2021, 192, 104395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, K.; Wang, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Li, J. A towed-type shallow high-resolution seismic detection system for coastal tidal flats and its application in Eastern China. J. Geophys. Eng. 2020, 17, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. Research on the application of high resolution 3D seismic reflection exploration in offshore engineering. Prog. Geophys. 2024, 39, 1670–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.W.; Gao, W.; Hu, R.L.; Xu, P.F.; Xia, J.G. Microtremor survey and stability analysis of a soil-rock mixture landslide: A case study in Baidian town, China. Landslides 2018, 15, 1951–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asten, M.W.; Hayashi, K. Application of the spatial auto-correlation method for shear-wave velocity studies using ambient noise. Surv. Geophys. 2018, 39, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.S.; Dai, Q.W.; Xiao, B. Contrast between 2D inversion and 3D inversion based on 2D high-density resistivity data. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2014, 24, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, T. The development of DC resistivity imaging techniques. Comput. Geosci. 2001, 27, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahor, M.G.; Berge, M.A. Integrated geophysical investigations in a fault zone located on southwestern part of İzmir city, Western Anatolia, Turkey. J. Appl. Geophys. 2017, 136, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cai, X.; Yan, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Using the integrated geophysical methods detecting active faults: A case study in Beijing, China. J. Appl. Geophys. 2018, 156, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccardi, L.; D’Alessandro, A.; Vittori, E.; D’Intinosante, V.; Baglione, M. An integrated remote sensing and near-surface geophysical approach to detect and characterize active and capable faults in the urban area of Florence (Italy). Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DB/T 93.3-2024; Active Fault Survey—Requirements of Achievement Reports—Part 3: Special Subject Work Reports. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Yang, F. Influence of Three Gorges Reservoir on Seismic Activity near the Northern Part of the XianNv Mountain Fault. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Seismology, China Earthquake Administration, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.F. Study on Fault Reactivation Feature of Xiannvshan-Jiuwanxi Fault Zone in the Head Area of the Three Gorges. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Seismology, China Earthquake Administration, Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.