Abstract

To enhance blockchain scalability, sharding technology enables parallel transaction processing, but existing solutions often neglect node heterogeneity, which introduces security risks and performance bottlenecks. This paper proposes a novel dynamic sharding scheme that dynamically allocates validators to shards based on their historical performance scores and computational power, ensuring balanced shard capacity and higher attack resistance. A tailored reward–penalty mechanism further incentivizes participation and discourages malicious behavior. Experimental evaluations demonstrate that our approach significantly outperforms prominent sharding protocols, including Elastico, OmniLedger, and RapidChain, by achieving higher throughput and lower latency. The proposed scheme effectively addresses node heterogeneity and enhances the overall scalability and security of blockchain systems.

1. Introduction

Blockchain scalability pertains to the capability of improving transaction throughput through the expansion of nodes within the blockchain network [1,2,3]. However, some encrypted digital currencies, like Bitcoin, suffer from poor scalability, making it challenging to enhance transaction throughput solely by increasing the quantity of nodes [4,5,6,7]. To address this issue and achieve horizontal scalability, sharding technology has emerged as a promising approach [8,9,10,11,12]. Sharding is a process where the network state is partitioned into smaller subsets. Each of these subsets forms a distinct group that is tasked with handling a specific set of mutually exclusive transactions allocated to it. In other words, transactions are distributed across different slices to enable parallel processing between them. By allocating blockchain nodes to multiple equally-sized node groups, sharding enables these committees to independently process distinct transactions [13]. Consequently, the system can achieve higher scalability, eliminating the impediment that hinders the enhancement of network throughput. Existing fragmentation approaches in blockchain sharding protocols primarily rely on arbitrary fragmentation [14]. Examples include Elastico and OmniLedger, among others. In these sharding systems, the heterogeneity between nodes is not fully considered, leading to random assignment of all nodes to each committee [2,15,16,17,18].

To solve the influence of ignoring the heterogeneity between nodes on both the security and throughput of the blockchain system, this article advocates for a specific blockchain fragmentation scheme based on node heterogeneity and reward and punishment incentive mechanisms [19,20,21]. This sharding scheme balances the total accumulated points of different shards and improves the throughput and security of the blockchain system by sharding the blockchain system based on the accumulated points of all nodes in the sliding window of the first w epochs and the computing power of each node. In conclusion, this article contributes in the following ways:

- Propose a sharding scheme based on node heterogeneity and reward and punishment mechanisms, dynamically allocating shards based on the historical scores of validators, balancing the total scores of each shard to improve attack difficulty and enhance system security.

- Design a new node incentive mechanism for electing administrators within shards, giving new nodes the opportunity to be elected as shard administrators and earn more points, motivating nodes to actively participate in transactions.

- Establish a reward and punishment mechanism that combines differences in computing power, allocates transactions based on node points and differences in computing power, and improves the throughput of sharded systems.

Unlike existing reputation sharding schemes such as RepChain and RepuCoin, which mainly rely on static or slowly updated reputation weights, this scheme introduces dynamic integration as the core coordination variable. This integral reflects the recent performance of nodes in real-time through a sliding window, combined with real-time computing power evaluation. It is not only used to measure contributions but also to actively construct balanced and highly reliable shards and dynamically determine the eligibility of nodes to participate in governance, thus achieving deeper integration between incentive mechanisms and security architecture.

2. Related Work

Recent years have witnessed further diversification in sharding designs, targeting specific scalability bottlenecks and application contexts. Nguyen et al. [22] propose a sharding platform for the metaverse: MetaShard, employing dynamic resource allocation across shards to handle spatially-correlated workloads. However, its primary focus is on data and computation locality rather than on mitigating the security implications of node capability heterogeneity within a shard. BrokerChain [12,18] is a novel cross-shard consensus protocol leveraging broker accounts to atomically bundle transactions, significantly reducing the communication rounds for cross-shard settlement. While innovative in cross-shard communication, its underlying shard formation remains static or reputation-based, not dynamically optimized for balanced intra-shard capability. OverShard [9] is a full-sharding architecture with overlapping networks and virtual accounts to achieve near-linear scalability. Its contribution lies in system-level scalability, yet it does not address the micro-level problem of how to compose individual shards from a heterogeneous pool of nodes to maximize each shard’s inherent security and efficiency. In contrast to these works, our scheme addresses a more foundational layer: the dynamic, performance-aware construction of shards themselves. We treat node heterogeneity not as a secondary factor but as the primary dimension for optimization, aiming to construct shards that are not only parallel processing units but also robust security compartments. This focus on intra-shard compositional security complements the aforementioned advancements in cross-shard protocols and application-specific scalability.

Fragmentation technology is a potent approach for addressing the scalability challenge in blockchain. In recent years, numerous proposals for blockchain architectures aim to boost scalability and tackle performance and security challenges within the blockchain [23,24,25].

Elastico is the first full-fledged realization of blockchain fragmentation technology. By segmenting the nodes of the blockchain into various committees, each responsible for validating distinct transactions, as the quantity of nodes in the blockchain network increases, the blockchain’s transaction verification speed can achieve almost proportional growth [26,27]. Elastico assigns certain nodes to a distinctive DS committee, and the others are made up of all the other nodes. Inside each committee, Elastico uses the PBFT [28] consensus protocol to reach a consensus, which not only improves the system’s transaction throughput, but also alleviates the transaction delay perceived by users.

OmniLedger [1] is the pioneer in a public blockchain framework with horizontal scalability that provides an enduring security guarantee. They use the BFT consensus protocol to implement the transaction atom submission protocol for cross-submission transaction verification to counteract network attacks and enhance blockchain system efficiency. In terms of storage efficiency, OmniLedger alleviates the storage burden and reduces the update overhead of each node in the entire system by introducing state blocks into the blockchain network. This allows each node to locally store partial state information during transaction processing and synchronize the entire system through updated state blocks. OmniLedger introduces a positive verification model to diminish the delay of transactions.

RapidChain [2] is the initial public blockchain protocol founded on fragmentation, which can resist one-third of its participants’ Byzantine faults and achieve complete fragmentation of transaction handling, computing, and storage costs. RapidChain employs the best intra-committee consensus algorithm without presupposing any trusted establishment. Through block pipeline technology and a verified reconfiguration mechanism, it attains a considerable level of throughput.

Based on the previous blockchain fragmentation technology, RepChain [3] proposed a dual-chain architecture for the first time, which deals with the transaction chain and the reputation chain, respectively. In terms of consensus protocols, RepChain employs a synchronous Raft [14] consensus protocol modified on the basis of traditional Raft for the transaction chain, and proposes a synchronous BFT [23] consensus protocol CSBFT [27], for the reputation chain [12]. RapChain can achieve consensus on both the transaction chain and the reputation chain in an efficient manner.

RepuCoin [4] is also a reputation-based blockchain fragmentation scheme, in which the reputation of the verifier mainly depends on the PoW contributed by the verifiers, only considering the difference of the verifier’s reputation, without fully considering the heterogeneity between nodes.

Most of the existing fragmentation-based protocols do not fully consider the difference in computing power between nodes. They usually only consider whether the node is an honest node and ignore the heterogeneity between nodes. The heterogeneity between nodes is also an important factor in the fragmentation system and cannot be ignored [29]. In addition, most of the existing fragmentation protocols randomly assign nodes to a certain fragment, which is unfair to those with weak computing power. Therefore, we need to design a more secure scheme to fragment the nodes in the entire blockchain network. In this paper, the blockchain fragmentation scheme based on node heterogeneity and a reward and punishment incentive mechanism fully considers the heterogeneity between nodes. The blockchain system is fragmented, and the corresponding inter-chip administrators are selected through the cumulative points and computing power of nodes. This scheme balances the total cumulative points of different fragments and enhances the throughput and security of the blockchain system [9].

Table 1 shows a comparison of different sharding protocols, compared to Elastico (random sharding), OmniLedger (RandHound sharding), and RepuCoin (static reputation-based sharding), the core conceptual distinction of our scheme is treating nodes as heterogeneous and dynamically evolving entities, rather than homogeneous or statically trusted units. Sharding and election decisions are based on nodes’ sustained contributions within a sliding window and real-time computing power, rather than one-time identities or simple randomness.

Table 1.

Comparison of sharding protocols.

3. System Model

In a complete era from e − 1 to e, the fragmentation of the blockchain and the verifiers and administrators in each fragmentation have changed. The purpose is to prevent some nodes from monopolizing or becoming malicious nodes due to excessive accumulation of points to attack the blockchain network and ensure the security of the blockchain system. At the beginning of each era, the blockchain system will re-segment all nodes in the entire system according to the blockchain segmentation and the on-chip administrator selection algorithm, and then the nodes in each segment will run for the on-chip administrator.

Our system is designed based on the following formal assumptions:

Network Model: Partially synchronous network with bounded message delays.

Adversary Model: The adversary can adaptively corrupt up to f < n/3 nodes, which become Byzantine.

Trust Assumptions: No trusted setup is required; node identities are initially established via public keys, and cryptographic primitives are secure.

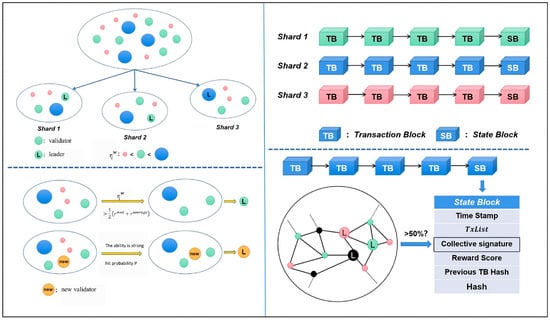

At the end of each era, the administrator of each shard will generate a state block SB based on the transaction block and the collective signature CoSi [6] to end the entire transaction chain. All verifiers can determine whether the collective signature in the other shard state block contains more than half of the verifiers in the shard to confirm the signature, and verify whether the shard transaction block and the bonus score are valid. At the same time, all verifiers will synchronize and update local data based on these state blocks from other fragments, and then the system will automatically start the next era [30]. The details of the model are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

System model diagram.

4. System Design

This section introduces the design principle of the system in detail. Unlike the random or simple reputation-based sharding in protocols like Elastico and OmniLedger, the core innovation of our scheme lies in proposing a dynamic and adaptive sharding framework based on node heterogeneity. Its fundamental novelty is manifested in: (1) Score-Driven Dynamic Balanced Sharding: Shards are formed based on nodes’ historical scores within a sliding window (comprehensively reflecting their processing capability and participation), ensuring long-term capacity balance across shards, as opposed to static or random assignment. (2) Two-Tier Adaptive Election Mechanism: The intra-shard leader election not only considers score ranking but also introduces a dynamic threshold based on the median and average for eligibility filtering, and provides a probabilistic participation channel for new validators with strong computing power. This achieves a balance between incentivizing long-term contribution and fostering new network participation. Conceptually, these designs shift from “equal node identity” to “differentiated role assignment based on contribution and capability,” aiming to systematically address the security and performance imbalance caused by node heterogeneity.

4.1. Blockchain Fragmentation and Administrator Selection

At the start of each era, validators are assigned to shards via Algorithms 1 and 2, balancing total cumulative points across shards to maintain dynamic equilibrium and raise the attack barrier. Each shard then randomly elects one capable administrator, making results unpredictable and preventing targeted attacks. A reward–punishment mechanism awards points for transaction verification. Only validators whose cumulative points over a sliding window of the last w epochs rank high are eligible for administrator election, preventing point monopolization and encouraging participation. The sliding window size w is a trade-off between security and liveness. w = 10 is chosen empirically: the score distribution stabilizes within 10 epochs, which is sufficient to smooth short-term fluctuations and prevent speculative behavior while providing new nodes with a reasonable promotion window. Increasing w enhances security but reduces system responsiveness. We sort the cumulative points of each w validator in the Scores set in descending order. When partitioning the blockchain, we assign the validators to the shards in descending order of the total cumulative points, in order of sort (Scores). It is to allocate verifiers with smaller to shards with smaller cumulative points, to avoid the phenomenon of verifiers with smaller being unable to compete for resources in shards with larger cumulative points. Simultaneously, this sharding approach ensures that the accumulated total scores for each shard are relatively balanced. This prevents malicious nodes from choosing to attack shards with smaller total scores, effectively ensuring the overall security of the entire system. The core design objective of the score is to quantify a node’s reliability and competitiveness, serving as the basis for shard assignment and administrator election. Its property of objectively reflecting historical contributions also naturally yields a proof-based fairness.

| Algorithm 1 Algorithm for Blockchain Sharding |

| Input: A random number and the cumulative Scores = {, , …, } over previous w epochs |

| Output: The shards = {, , …, } |

| Initialize = ∅ for each 1 ≤ ≤ |

| for each in sort(Scores) do Find the shard with the smallest cumulative total number of points |

| if multiple shards with the same cumulative points are found then Randomly select one of the shards based on the random number |

| end if |

| Assign validator to , = ∪{} |

| end for |

After sharding the validators in the blockchain network, some validators in each shard can participate in the administrator’s election [15]. For each shard, we take half of the sum of the median and the mean of the cumulative integrals of all validators in the current shard. In the current sharding, only validators with greater than or equal to are eligible to participate in the administrator’s election. The corresponding value of these validators is the ratio of y (0 ≤ y ≤ 1) and randomly generated by the random number seed . For validators with less than , we will take their value as +∞, which means that these validators will directly lose their eligibility as campaign administrators. Finally, we will choose the validator with the smallest value in each shard to become the administrator of the current shard, which means that the validator with a larger has a greater chance of being elected as an administrator. And on this basis, we introduced an incentive mechanism for validators who have newly joined the blockchain network. When a validator with strong computing power joins the blockchain network, we set a probability P. If this probability P is hit, then the current newly added validator also has a chance to join the administrator election and has a certain chance of being elected as an administrator.

| Algorithm 2 Algorithm for Intra-Shard Administrator Election |

| Input: A random number and the cumulative Scores = {, , …, } over previous w epochs The shards = {, ,…, } |

| Output: The leaders = {, ,…,} |

| Initialize = ∅ for each 1 ≤ ≤ |

| for each shard ∈ do = median number of the subset of Scores in = average number of the subset of Scores in = ( + ) |

| for each validator ∈ do |

| if ≤ then Generate a random floating-point number 0 ≤ ≤ 1 from the random number = / |

| else if is a new validator and ComputePower() > Percentile(CompDist, 75) and hit probability P then Generate a random floating-point number 0 ≤ ≤ 1 from the random number = |

| else = +∞ |

| end if |

| end for |

| = when = min(, , …, ) |

| end for |

ComputePower() is a verifiable proof of computing power (e.g., signature verifications per unit time), and Percentile(CompDist, 75) is the 75th percentile of the global computing power distribution. P is set to a low value (0.05–0.1) to balance allowing high-capability new nodes to participate and resisting Sybil attacks. The design of the score threshold adopts the mean of the median and mean values, which is robust to extreme values. The reward and punishment coefficient is calibrated through simulation experiments. Correct operation reward (0.1) > unknown operation reward (0.01) to encourage participation; false acceptance penalty (−1.0) > false rejection penalty (−0.45) due to higher harm. The system is robust to small variations in these parameters, but extreme values may disrupt incentive balance.

Algorithm 1 (Sharding): Sorting scores has time complexity . Subsequently, find the shard with the smallest total score for each score. If M is the number of shards, using a min-heap to maintain shard totals reduces the cost of each find-and-update operation to . Thus, the overall time complexity is (since typically ). The communication complexity is dominated by broadcasting the sharding result, which is .

Algorithm 2 (Election): For each shard (total ), calculating its median and average takes where is the shard size, and computing the weight for each member takes . Therefore, the total time complexity is , since . Communication complexity is limited to broadcasting election-related data within shards, which is .

4.2. Consensus Protocol

4.2.1. Intra-Shard Consensus

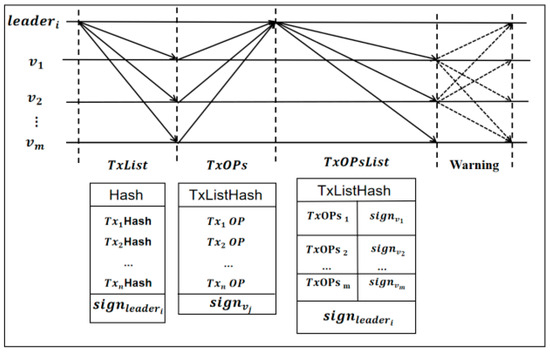

In each shard, administrators utilize the Raft consensus protocol to generate transaction blocks. The related data structures and Raft consensus communication mode are illustrated in the following diagram.

As shown in Figure 2, for the set of TxList transactions sent by the administrator to all validators, each validator needs to perform corresponding transaction operations for each transaction in TxList. We have introduced TxOPs transaction operations here, which can be taken as 0/1/2, corresponding to a valid transaction/invalid transaction/unknown. The purpose of introducing TxOPs and unknown is to prevent some validators in the blockchain network from being unable to process some transactions due to their own computing power limitations. In this case, these validators can return unknown to the corresponding shard administrator to avoid penalties caused by rejecting valid transactions. The administrator will package the collected TxOPs and generate TxOPsList, where the transaction operations in TxOPsListcorrespond one-to-one with the transaction sequence in TxList.

Figure 2.

Communication mode.

The administrator generates the corresponding transaction block based on TxOPsList, and then sends the generated transaction block and TxOPsListto all validators on the chip. If the administrator sends an invalid TxList, TxOPsList, or some of the transactions contained in the sent transaction block are not recognized as valid by more than 50% of the validators, then at this time, the honest validators within the shard will send a warning to other validators and administrators. Simultaneously start the rollback program, and then reselect the administrator. At the same time, the accumulated points of malicious administrators have also been cleared [16], posing challenges for their involvement in the administrator election in the next epoch.

If we only determine whether the validator is a node newly added to the blockchain network based on the transaction processing record of each validator, it is inevitable that there will be a misjudgment. After introducing unknown in the transaction operation, if there is a validator who has not processed the transaction or is unable to process a certain transaction, then the validator should return the unknown value to the administrator at this time, so that the transaction processing record of the validator will not be displayed as empty, so that the system can easily distinguish between new and old nodes [22,31,32].

4.2.2. Inter-Shard Transactions

For inter-shard transactions, in this system, we utilize the Atomix protocol, where clients assist in relaying transactions across shards by accepting proofs. In our framework, the administrator generates a state block with the collective signature CoSi by packaging the transaction block along with its associated reward distribution outcomes. The state block comprises the cryptographic hash of the preceding transaction block, the CoSi collective signature, the associated timestamp, the complete set of transactions, and the set of point reward scores obtained by all validators in the current era. Acceptance proofs take the form of collective signatures on the state block SB.

4.3. Incentive and Penalty Mechanism

At the end of each intra-shard consensus in sharding, all validators within the shard will receive a certain amount of score rewards for processing transactions during the current epoch. These score rewards are calculated uniformly by the intra-shard administrator based on the transaction blocks.

Taking into account the variations between transactions, we have designed an incentive mechanism for score rewards that aligns with the value of the transactions processed by each validator. This mechanism ensures that validators receive appropriate score rewards based on the significance of the transactions they handle.

Among them, refers to the total number of point rewards obtained by each verifier through transaction processing within an era, n refers to the number of transactions processed by each verifier within an era, refers to the value of each transaction, and refers to the proportional factor.

At the end of each epoch, during the score reward calculation process for each shard administrator, as this scheme introduces an operation in each transaction corresponding to the transaction operation, the corresponding transaction operation is divided into three types: valid transactions, invalid transactions, and unknown. In this scheme, each of the three transaction operations corresponding to each transaction is associated with different operation factor ratios. In this scheme, we set the ratio factors corresponding to each transaction operation as 0.1 (correct transaction operation), 0.01 (unknown transaction operation), −0.45 (an erroneous transaction operation that should be approved through transaction, but validator decides to reject it), and −1 (an erroneous transaction operation that should have been rejected by the transaction but the validator erroneously chooses to accept). The introduction of ratio factors with a value of 0.01 is aimed at achieving the incentive mechanism for the entire system, encouraging all nodes to actively participate in the processing of each transaction regardless of differences in computational power. This approach ensures that each node contributes to the best of its ability. The ratio factors of −0.45 and −1.0 correspond to validators rejecting correctly transactions and approving incorrectly transactions, respectively.

The parameter values were determined through an iterative process guided by two primary objectives: (1) Security: malicious or highly unreliable nodes should see their scores rapidly decay below the election threshold rthrth; (2) Liveness and Fairness: nodes with genuine but limited computational resources should maintain a non-negative score trajectory by returning unknown for unprocessable transactions, preserving network participation. The reward–penalty coefficients were determined through an iterative design-space exploration guided. The coefficients (0.1, 0.01, −0.45, −1.0) are chosen based on empirical tuning to achieve a balance between incentive and penalty. Correct transaction (0.1): Encourages participation while preventing inflation. Unknown (0.01): Minimal reward for effort, encouraging nodes to attempt processing. Wrong rejection (−0.45): Significant penalty for rejecting valid transactions. Wrong acceptance (−1.0): Severe penalty for accepting invalid transactions.

The specific numerical values were obtained via simulation-based optimization. We searched the parameter space to find a set that minimizes the time for a simulated malicious node (with a 30% error rate) to recover its score after penalties, while ensuring a node with 50% unknown and 50% correct actions maintained a slowly positive score trend. The chosen set represents a Pareto-optimal point balancing security and participation.

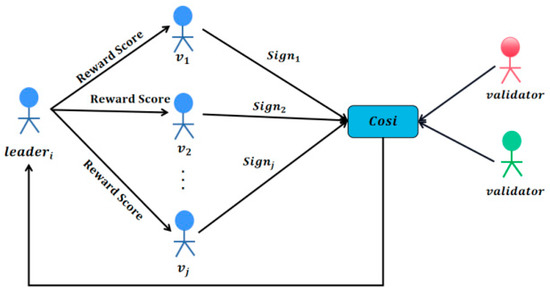

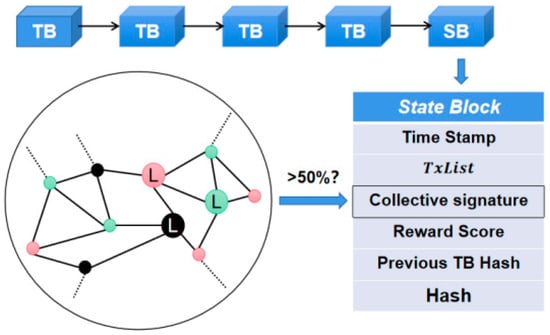

As shown in Figure 3, after the calculation of point reward scores is completed, the administrator will send the Reward Scores set in the form of a broadcast to all verifiers on the film for confirmation. After verifying that there are no errors, the verifiers on the film will return a confirmation signature to the administrator. Finally, the administrator will package and generate a status block SB containing the collective signature CoSi based on the transaction block and corresponding point reward results [33]. As depicted in Figure 4, the state block SB encompasses the hash of the preceding transaction block, the collective signature CoSi, the SB-generated timestamp, the transaction set, and the bonus points accumulated by validators during the current era. Other shards can authenticate the validity of the current transaction block and the bonus score by verifying whether the collective signature in SB is endorsed by a majority of validators.

Figure 3.

Process of generating collective signatures.

Figure 4.

Verifying transactions between shards.

4.4. System Analysis

- (1)

- The more transactions processed by the validator in each shard, the greater the corresponding transaction value, and the more bonus points obtained.

- (2)

- Only when each validator reaches a consensus on the transactions they are processing, and other validators, can they receive corresponding point rewards.

- (3)

- The points awarded to administrators in each shard should be higher than those of ordinary validators within that shard.

For the first principle, we introduce the computational structure of in the integral reward and punishment mechanism.

is directly proportional to the number of transactions processed by the verifier within an era and the corresponding transaction value, which can achieve the expected effect of motivating each verifier to do their best.

For the second principle, the original intention of our system design is to ensure the fast, safe, and normal operation of the blockchain system [34]. If some validators fail to process transactions or perform correct transaction operations, and our system also rewards them with points, it violates the original intention of the blockchain system design. The system will only reward a certain number of points when the verifier reaches a consensus on the transaction operation made by the transaction and other verifiers.

Based on node heterogeneity and incentive mechanisms, we introduce a new blockchain sharding scheme. Validators earn points for verifying transactions. At each era’s start, they are reassigned to shards with balanced total points, raising the attack difficulty and enhancing security. A novel election mechanism allows new nodes to become shard administrators, motivating participation. An integrated reward–penalty model accounts for differences in node computational power and points, optimizing transaction allocation and increasing system throughput.

5. Experimental Analysis

5.1. Safety Analysis and Threat Mitigation

We analyze the security of our scheme under the models defined in Section 3.

- A.

- Resistance to Shard Takeover Attacks. An adversary aiming to control a specific shard must concentrate a high proportion of its high-score nodes there. Our dynamic sharding algorithm (Algorithm 1) actively balances total scores across shards, making it computationally expensive to target a single shard. The sliding window w further limits the rate at which an adversary can inflate scores, making a takeover require sustained, costly effort.

- B.

- Mitigation of Malicious Administrators. A malicious administrator can propose invalid blocks. Our intra-shard consensus protocol (Section 4.2.1) includes a Warning and rollback mechanism triggered if >50% of validators dispute a block. The malicious administrator’s score is then reset, significantly reducing its chance of re-election in subsequent epochs (Algorithm 2). This defense relies on the honest majority within a shard, which our sharding algorithm is designed to maximize.

- C.

- Sybil Attack Resistance. While an adversary can create many identities, each new identity starts with a score of zero. Gaining score requires processing transactions, which is gated by the current score and capability. This creates a “bootstrapping” barrier. The special pathway for high-power newcomers (with probability P) is guarded by a quantifiable capability threshold, preventing cheap Sybil floods.

- D.

- Adaptive Adversary. An adversary may behave honestly to accumulate a score and then betray. The sliding window w limits the historical value of past good behavior. A single epoch of malicious action (e.g., as an administrator) leads to a score reset, nullifying the long-term investment. The reward–penalty mechanism ensures that the cost of betrayal outweighs the benefits.

- E.

- Cross-Shard Transaction Attacks. We leverage the Atomic protocol with CoSi-signed state blocks. A cross-shard transaction is only finalized if all involved shards produce valid state blocks signed by a majority of their validators. This inherits the security of the intra-shard honest majority.

Formal Security Guarantees. Under the partial synchrony model, with an adversary controlling less than 1/3 of the computational power per shard (and globally), and with our dynamic sharding maintaining balanced, high-honest-concentration shards, our scheme guarantees:

Safety: No two honest nodes will confirm conflicting transactions.

Liveness: Transactions submitted by honest clients will eventually be processed and confirmed, barring persistent network partitions.

When using our heterogeneous sharding and in-chip administrator selection scheme for nodes, the attacking nodes that want to cause damage to the blockchain system must be new nodes with particularly strong computing power, or nodes with high cumulative integral scores that have already made a certain contribution to the blockchain system. However, the probability of the former being elected as an administrator is much lower than the latter. So, in order to prevent nodes with high cumulative integral scores from becoming malicious nodes and causing damage to the system, we adopt a sliding window w cumulative integral computing system. Each w era is a sliding window period [35], and each verifier’s refers to obtaining cumulative integral scores in the first w eras. This can effectively prevent a small number of nodes from becoming “super nodes”, thus controlling and managing the entire system.

5.2. Performance Analysis

We implemented the scheme in Go 1.19 on a cluster of 10 machines (Intel Xeon E5-2680, 64 GB RAM). Network latency was emulated using Linux tc (IBM, New York, NY, USA) with delays uniformly distributed between 50 and 150 ms. The system was deployed in a simulated environment using Docker containers, with each node running in a separate container. We set the epoch duration to 60 s and the sliding window w = 10.

We implement this scheme in the Go language, and for collective signatures, we use code from the Go language encryption library to implement it. For the parameters that need to be used in the experimental process of this scheme, we set the sliding window w to 10, and the number of malicious nodes should not exceed one-third. During points and rewards calculation, the proportion factors of s are 0.1 for correct transaction operations, 0.01 for unknown ones, −0.45 for erroneous operations that should be approved but are rejected by validators, and −1 for those that should be rejected but are mistakenly accepted. To simulate transactions, validators in the sharding system generate their own and share them with others.

In this analysis, we tested the system performance of this scheme under different shard sizes and node numbers. Performance indicators include two parts: throughput and latency.

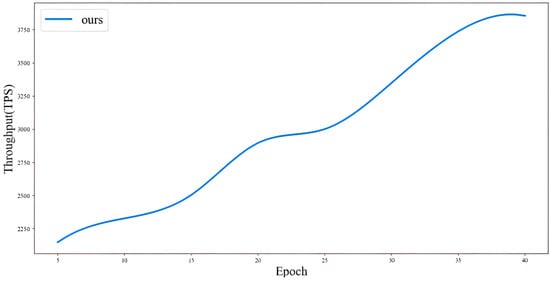

From Figure 5, it can be seen that after introducing node heterogeneity-oriented sharding and administrator selection schemes, the throughput of the entire sharding system gradually increases with the increase of epochs, and eventually stabilizes. Due to the low of nodes in the entire sharding system at the beginning of the epoch, the elected administrators have low abilities, resulting in a lower throughput of shards. As the epoch increases, the . of all nodes gradually accumulates. This way, each shard can elect administrators with higher abilities in the administrator election, and in the subsequent transaction processing process, due to the existence of reward and punishment incentive mechanisms,. This includes incentive mechanisms for newly added nodes in the sharding system, which gradually increase the throughput of the entire system and eventually stabilize it.

Figure 5.

Throughput (transactions per second) evolution over epochs for our scheme, with system parameters: 320 nodes, 10 shards, w = 10. The shaded region represents the 95% confidence interval over 10 runs.

Each experiment was repeated 10 times, and the results show 95% confidence intervals within ±5% of the mean values. The system exhibits stable performance under varying network conditions.

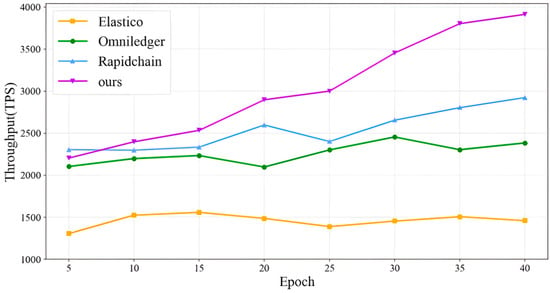

From Figure 6, it can be observed that the throughput of our proposed scheme, as well as the Elastico, OmniLedger, and RapidChain shardings, gradually increases with the growth of epochs. Moreover, the throughput of our proposed scheme is generally higher than that of Elastico, OmniLedger, and RapidChain. With the rise in epochs, the throughput of all four sharding schemes gradually plateaus.

Figure 6.

Comparison of average throughput (TPS) versus epoch number between our scheme and three baseline protocols (Elastico, OmniLedger, RapidChain) under the same network scale (320 nodes). Error bars denote one standard deviation.

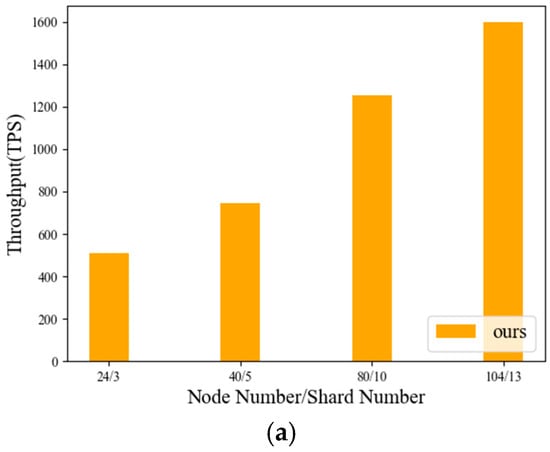

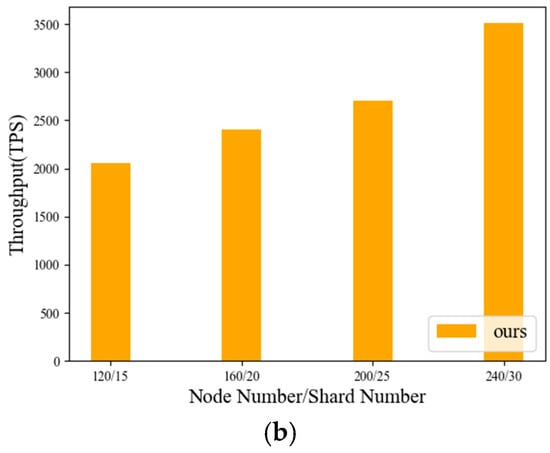

Figure 7 illustrates that this scheme’s transaction throughput improves progressively with higher N/S values. According to theoretical analysis, when shard sizes are fixed, system performance can be boosted by increasing the total number of shards. The experimental data in this work validate this trend, showing throughput growth alongside N/S expansion from 24/3 to 240/30.

Figure 7.

Average throughput of transactions with different sizes of shards and number of nodes.

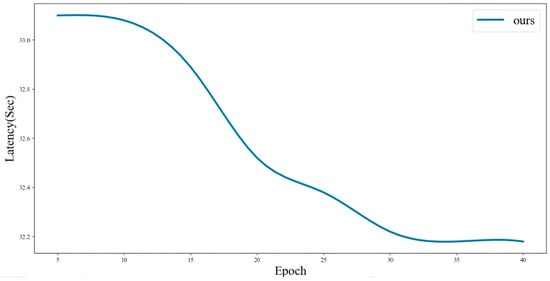

From Figure 8, it can be seen that after introducing a node-heterogeneous sharding scheme in the sharding system and introducing a reward and punishment incentive mechanism on this basis, in an environment of 320 nodes, the processing delay of transactions in the system will fluctuate with the change in epoch. At the beginning of the epoch, the transaction processing delay of the system is the longest. As the transaction processing gradually progresses, due to the existence of reward and punishment incentive mechanisms, all nodes in the sharding system and newly added nodes in the blockchain network are incentivized, so that the transaction processing latency of the entire system gradually decreases.

Figure 8.

Average transaction latency (seconds) per epoch for our scheme in a 320-node network. The latency stabilizes after the initial epochs as node scores and shard compositions reach equilibrium.

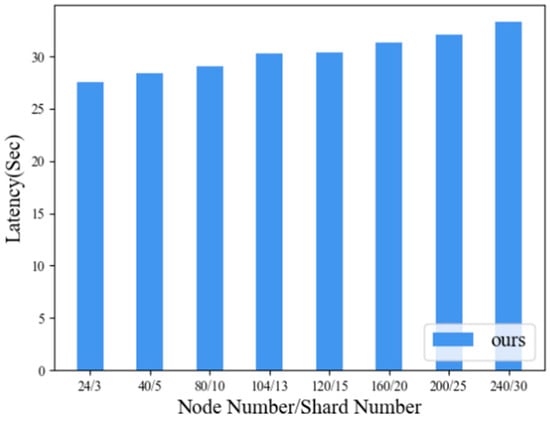

From Figure 9, we can see that as the nodes and shards in the entire sharding system increase, that is, with N/S rising, the transaction processing delay of this scheme will gradually rise and fluctuate between 26 and 33 s within the experimental N/S range.

Figure 9.

Average latency for different sizes of shards and number of nodes.

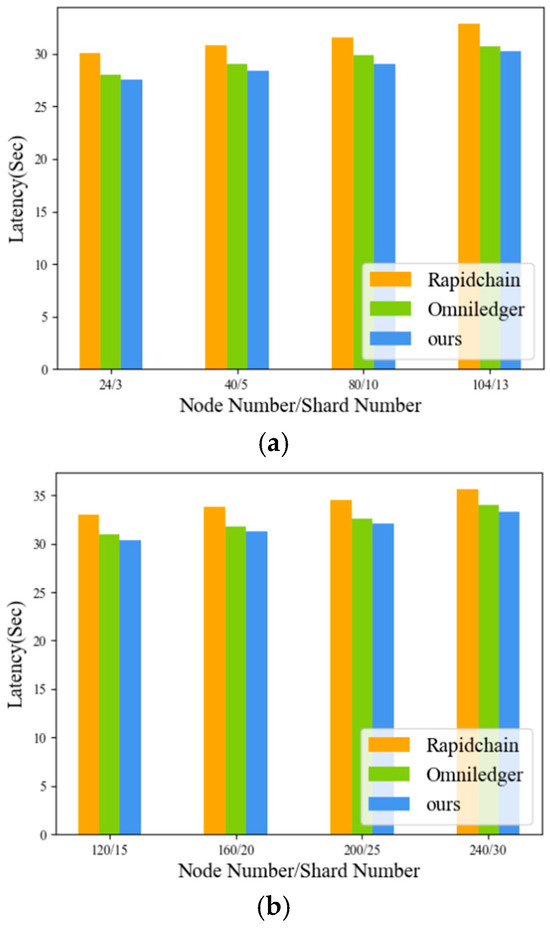

The results in Figure 10 show that higher N/S ratios, achieved by expanding both network nodes and shards, lead to increased transaction delays in the proposed scheme. The transaction processing delay of the OmniLedger and RapidChain sharding models will also increase with the increase of N/S. However, after introducing node heterogeneity-oriented sharding schemes and corresponding on-chip administrator selection schemes into sharding systems, the transaction processing latency of the entire system is significantly lower than the two sharding models, OmniLedger and RapidChain.

Figure 10.

Latency comparison between this scheme and OmniLedger, and RapidChain sharding systems.

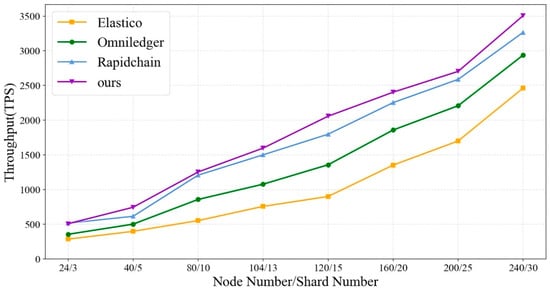

From Figure 11, it is evident that the throughput of our proposed scheme, as well as the Elastico, OmniLedger, and RapidChain sharding solutions, gradually increases with the augmentation of N/S. Moreover, the overall throughput of our proposed scheme surpasses that of Elastico, OmniLedger, and RapidChain.

Figure 11.

Comparison of throughput between this scheme and Elastico, OmniLedger, and RapidChain sharding systems as the number of nodes and shards increases.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we have proposed a novel blockchain sharding scheme that addresses the challenges posed by node heterogeneity. Our scheme dynamically assigns validators to shards based on their historical performance and computational power, ensuring balanced shard capabilities and enhancing system security and throughput. The reward–penalty mechanism introduced in our scheme further incentivizes validators to maintain high performance and adhere to protocol rules. Through extensive experiments, we have demonstrated that our scheme outperforms existing sharding approaches such as Elastico, OmniLedger, and RapidChain in terms of throughput and latency.

In future work, we will focus on several promising directions. First, we plan to explore more sophisticated incentive mechanisms that can better adapt to dynamic network conditions and varying node capabilities. Second, we aim to enhance the robustness of our scheme against more advanced attack vectors, such as sybil attacks and eclipse attacks. Third, we will investigate the integration of our sharding scheme with other blockchain scalability solutions, such as state channels and DAG-based ledgers, to further improve overall system performance.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: G.X. and Y.Z.; data collection: Y.Z.; analysis and interpretation of results: Y.Z.; draft manuscript preparation: G.X. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFB2703802); in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62272120, 62572133); in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2024A1515011426); in part by the Jointly Funded Projects of Universities, Institutes and Enterprises under the Basic Research Program of Guangzhou (Grant No. 2024A03J0325); in part by the Science and Technology Innovation Key R&D Program of Chongqing(Grant No. CSTB2023TIAD-STX0031); in part by the Major Key Project of PCL (Grant No. PCL2024A05); in part by the Project of Guangdong Key Laboratory of Industrial Control System Security (Grant No. 2024B1212020010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the teachers and students in the laboratory for your help and valuable suggestions during the research process. The cooperation and discussion with you greatly promoted the progress of the research, and thank you for your efforts and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kogias, E.K.; Jovanovic, P.; Gasser, L.; Gailly, N.; Syta, E.; Ford, B. Omniledger: A secure scale-out decentralized ledger via sharding. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 583–598. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani, M.; Movahedi, M.; Raykova, M. Rapidchain: Scaling blockchain via full sharding. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–19 October 2018; pp. 931–948. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W.; Guan, X. Repchain: A reputation based secure fast and high incentive blockchain system via sharding. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 4291–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Kozhaya, D.; Decouchant, J.; Verissimo, P. RepuCoin: Your reputation is your power. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2019, 68, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apoorv, L.; Zhu, J.; You, F. From mining to mitigation: How Bitcoin can support renewable energy development and climate action. ACS Sustain. Chem. 2023, 11, 16330–16340. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Tiwari, S.; Khaled, D.; Mahendru, M.; Shahzad, U. Forecasting Bitcoin prices using artificial intelligence: Combination of ML, SARIMA, and Facebook Prophet models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2024, 198, 122938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Dinh, T.T.A.; Loghin, D.; Chang, E.-C.; Lin, Q.; Ooi, B.C. Towards scaling blockchain systems via sharding. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Management of Data, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 30 June–5 July 2019; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Shi, Z.J.; Nixon, M.; Han, S. Sok: Sharding on blockchain. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Conference on Advances in Financial Technologies, Zurich, Switzerland, 21–23 October 2019; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, T.; Sheng, N.; Li, X.; Xu, J. OverShard: Scaling blockchain by full sharding with overlapping network and virtual accounts. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2023, 220, 103748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiza, H.; Shuaib, K.; Zaki, N. Sharding for scalable blockchain networks. SN. Comput. Sci. 2022, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Z.; Wang, X.; Lin, H.; Garg, S.; Kumar, P.; Hossain, M.S. A dynamic state sharding blockchain architecture for scalable and secure crowdsourcing systems. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 222, 103785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yin, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, J.; Luo, X.; Ye, G.; Peng, X.; Zheng, Z.; Guo, S. BrokerChain: A Blockchain Sharding Protocol by Exploiting Broker Accounts. IEEE Trans. Netw. 2025, 22, 1930–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Lu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Shi, L.; Tan, C.W.; Wei, Z. Throughput-Scalable Shard Reorganization Tailored to Node Relations in Sharding Blockchain Networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Social. Syst. 2024, 11, 7271–7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H. Monoxide: Scale out blockchains with synchronous consensus zones. In Proceedings of the 16th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation, Boston, MA, USA, 26–28 February 2019; pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Asheralieva, A.; Niyato, D. Reputation-Based Coalition Formation for Secure Self-Organized and Scalable Sharding in IoT Blockchains With Mobile-Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 11830–11850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alka, M.; Dwivedi, R.K. Enhancing Scalability in Sharding Blockchain via Interoperability Protocol. In International Conference on Trends in Computational and Cognitive Engineering; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 345–358. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Zhou, Z.; Song, X.; Huang, Y. Research on transaction allocation strategy in blockchain state sharding. FCGS 2025, 168, 107756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Peng, X.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Guo, S. Brokerchain: A cross-shard blockchain protocol for account/balance-based state sharding. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2022-IEEE Conference on computer Communications, London, UK, 2–5 May 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1968–1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hesam, H.; Fischer, M. The application of blockchain-based crypto assets for integrating the physical and financial supply chains in the construction & engineering industry. Automat. Constr. 2021, 127, 103711. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Huang, H.; Li, C.; Zheng, Z.; Guo, S. Revisiting double spending attacks on the bitcoin blockchain: New findings. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQoS), Tokyo, Japan, 25–28 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gueta, G.G.; Abraham, I.; Grossman, S.; Malkhi, D.; Pinkas, B.; Reiter, M.; Seredinschi, D.-A.; Tamir, O.; Tomescu, A. SBFT: A scalable and decentralized frust infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN), Portland, OR, USA, 24–27 June 2019; pp. 568–580. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Hoang, D.T.; Nguyen, D.N.; Xiao, Y.; Niyato, D.; Dutkiewicz, E. MetaShard: A novel sharding blockchain platform for metaverse applications. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 23, 4348–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Malkhi, D.; Reiter, M.K.; Gueta, G.G.; Abraham, I. HotStuff: BFT consensus with linearity and responsiveness. In Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 29 July–2 August 2019; pp. 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, M.; Cook, V.; Nguyen, L.; Thai, M.T.; Mohaisen, A. Partitioning attacks on bitcoin: Colliding space, time, and logic. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Dallas, TX, USA, 7–10 July 2019; pp. 1175–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Belchior, R.; Vasconcelos, A.; Guerreiro, S.; Correia, M. A survey on blockchain interoperability: Past, present, and future trends. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Xu, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, H. Meepo: Sharded consortium blockchain. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Chania, Greece, 19–22 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Xing, X.; Cheng, H.; Li, D.; Guan, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, Q. A flexible sharding blockchain protocol based on cross-shard byzantine fault tolerance. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensic Secur. 2023, 18, 2276–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Xu, T.; Peng, J.; Gan, N. TP-PBFT: A scalable PBFT based on threshold proxy signature for IoT-blockchain applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 15434–15449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, X.; Wang, C.; Jia, X. A survey of blockchain consensus protocols. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah, B. A taxonomy of blockchain consensus protocols: A survey and classification framework. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Onireti, O.; Imran, M.A.; Cao, B. How much communication resource is needed to run a wireless blockchain network? IEEE Net. 2021, 36, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xie, H.; Yan, Z.; Liang, X. A survey on blockchain sharding. ISA Trans. 2023, 141, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Salles, M.A.V.; Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Hu, B.; Henglein, F.; Lu, R. Building blocks of sharding blockchain systems: Concepts, approaches, and open problems. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2022, 46, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaung, S.S.; Park, G.S. Service-aware dynamic sharding approach for scalable blockchain. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2022, 16, 2954–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotan, M.; Pignolet, Y.A.; Schmid, S.; Tochner, S.; Zohar, A. Survey on blockchain networking: Context, state-of-the-art, challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.