Abstract

Hypertensive kidney disease (HKD) represents a significant contributor to chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal failure, yet its early detection remains challenging due to nonspecific clinical and imaging findings. The lack of a noninvasive diagnostic tool, preventing the use of biopsy and diagnosis by exclusion, suggests the underdiagnosis of patients and overestimation of HKD as the cause of renal replacement therapy. Ultrasonography, including Doppler assessment and renal resistive index measurements, provides a widely accessible, noninvasive approach to evaluate renal structure and hemodynamics, aiding in the identification of early renal impairment or renal artery stenosis. Shear-wave elastography (SWE) has emerged as a promising modality for noninvasive assessment of renal stiffness, potentially detecting structural changes prior to functional deterioration. Current evidence demonstrates SWE’s diagnostic potential in chronic kidney disease and early hypertensive renal disease; however, limitations such as inter-device variability, heterogeneous patient populations, and short follow-up periods constrain its clinical applicability. Neither ultrasonography nor SWE can yet serve as standalone diagnostic tools for HKD, emphasizing the need for standardization, further validation, and longitudinal studies to clarify their role in patient management and prediction.

1. Introduction

Hypertensive kidney disease (HKD) is a complication resulting from long-term suboptimal blood pressure control. According to the 2022 European Renal Association Registry Report, hypertension accounts for approximately 15.5% of new cases of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) in the European Union, while the etiology of kidney disease remains unknown in about 17% of patients initiating RRT [1]. In the United States, hypertension accounted for nearly 29% of new ESKD cases in 2019 [2].

Diagnostic criteria for HKD rely primarily on the exclusion of other causes of kidney dysfunction [3], which is frequently impossible without histopathologic assessment. Because most patients do not undergo renal biopsy, and some studies indicate a potential overdiagnosis of HKD, the true underlying cause of kidney disease often remains underrecognized [4,5,6].

The pathophysiological mechanisms of HKD extend beyond elevated blood pressure alone and include dysregulation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and both genetic and epigenetic predispositions. These processes lead to progressive renal parenchymal fibrosis and loss of function, which are not always detectable by routine imaging [7]. Accurate diagnosis of HKD is crucial because early detection of renal involvement allows for timely intervention to prevent progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD) and ESKD.

Ultrasonography is widely used in the diagnostic evaluation of both the causes and complications of arterial hypertension. However, the parameters assessed in a standard abdominal ultrasound examination do not allow for the detection of early stages of HKD. Hemodynamic measurements provide a better characterization of the impact of elevated blood pressure on renal function, although they remain nonspecific.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in shear-wave elastography (SWE) as a method for assessing the mechanical properties of tissues; however, the role of SWE specifically in HKD remains insufficiently defined. Recent studies involving patients with CKD have demonstrated its potential to identify structural alterations within the renal parenchyma before advanced clinical or imaging manifestations. Additionally, the latest research in a cohort of hypertensive patients demonstrated that renal cortical stiffness measured by SWE was significantly higher in hypertensive subjects compared with healthy controls and correlated positively with duration of hypertension, suggesting a role for SWE in early detection and monitoring of hypertension-related renal changes. Accordingly, emerging ultrasonographic techniques, such as SWE, may provide sensitive, noninvasive tools to identify early structural and hemodynamic changes that are not detectable with routine clinical or laboratory evaluations of HKD.

In this review, we discuss features of renal ultrasound in the diagnosis of HKD, ranging from standard 2D gray-scale imaging with renal dimensions and echogenicity, through advanced hemodynamic measures—including renal resistive index (RRI) and renal artery blood flow parameters—to SWE, a technique recently applied in renal ultrasound, highlighting its potential benefits, limitations, and current gaps in knowledge.

2. Methods

This narrative review summarizes the literature on the role of ultrasonography, including SWE, in the diagnosis of HKD. Publications were identified through structured searches of PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar using combinations of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) related to ultrasonography, elastography, renal hemodynamics, and HKD. The search was restricted to articles published up to 1 November 2025. Both original research articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses published in English were included.

3. Standard Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasonography is a highly accessible, non-invasive, low-cost, and reproducible imaging method providing valuable clinical information for diagnosis and monitoring. Despite the operator-dependent nature of image interpretation, measurements are comparable across observers and even with CT imaging [8], making ultrasonography a reliable diagnostic modality.

3.1. Two-Dimensional Renal Ultrasound

3.1.1. Examination Technique

No specific patient preparation is required before renal ultrasound. The examination is most performed in the supine position. In cases where bowel gas impairs renal visualization, the patient may be positioned prone or in a lateral decubitus position, and the probe can be slightly shifted dorsally. Because of the higher anatomical location of the left kidney, rib-related artifacts are frequent but can be minimized by scanning during inspiration, which also reduces the respiratory motion of the organ. A convex transducer operating at 3–6 MHz is typically used.

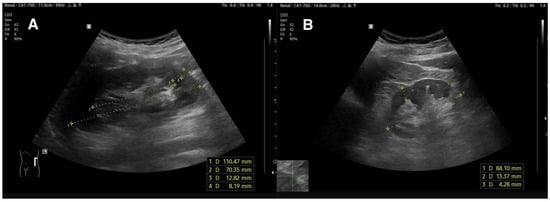

During abdominal ultrasound, renal length and width are measured, cortical thickness and parenchymal width are assessed, and echogenicity is evaluated in comparison with adjacent solid organs [9]. These parameters help identify both renal complications and potential renal causes of arterial hypertension. Differences between normal and abnormal renal ultrasound appearances are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(A)—normal kidney image of 20-year-old hypertensive patient. Atrophic Index is 0.64 which is within normal range (<0.7); (B)—kidney with reduced length, decreased parenchymal and cortical dimensions, and increased echogenicity.

3.1.2. Renal Length

The normal renal length on ultrasound is approximately 11 cm ± 2 cm [10].

Interpretation of renal dimensions should consider several influencing factors. Numerous studies on healthy participants have confirmed that sex, age, height, and body surface area (BSA) significantly affect renal volume and length [11]. Larger kidney size is associated with male sex [12], greater height, body mass, and BSA [10,13].

In a study by El-Reshaid et al. [14] a weak but statistically significant positive correlation between kidney length and body weight was observed, while no significant relationship with height or sex was found. Kidney size reaches its maximum during the second decade of life, remains stable until approximately the sixth decade, and subsequently decreases by about 0.5 cm per decade due to progressive nephron loss [15].

Data from different geographic regions indicate that renal dimensions also vary across populations [13], with mean lengths ranging from 9.6 cm [13] to 10.45 cm [16]. In clinical practice, adjustment of renal length or volume for anthropometric parameters—by calculating corrected kidney size—improves diagnostic precision.

The atrophy index, defined as the ratio of the renal medulla length to the total kidney length, provides a more accurate estimate of the proportion of functioning parenchyma by minimizing the effect of renal sinus fat, thus offering a more reliable indicator of preserved parenchymal mass in hypertensive patients [17]. Combined with the RRI, this parameter may help detect early HKD even in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) still within the normal range [17].

Although the left kidney is usually slightly longer than the right [13], a substantial asymmetry in renal length may suggest significant renal artery stenosis (RAS). Current guidelines remain inconsistent regarding the threshold difference, as summarized in Table 1. However, evidence suggests that reducing the traditionally accepted cutoff of 1.2 cm may improve both the sensitivity and specificity for detecting RAS [18].

Kidney long-axis measurement may also help predict the benefit of revascularization [19]. Bommart et al. [20] demonstrated that a combined index of renal length and RRI better predicted improvement in blood pressure control following revascularization, achieving sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 50%, respectively.

3.1.3. Cortical and Parenchymal Thickness

One of the key ultrasound parameters affected in HKD is parenchymal thickness, which progressively decreases with disease progression. The normal cortical thickness is 7–10 mm; however, due to variability in the visibility of corticomedullary differentiation, measuring the entire parenchymal layer is often more reproducible in clinical practice, with a normal range of 1.5–2 cm [21]. Additionally, computed tomography studies have shown that hypertensive patients exhibit cortical thinning despite having renal lengths comparable to normotensive controls [22,23]. These findings suggest that parenchymal thinning occurs earlier than a total renal length reduction, highlighting its greater sensitivity in detecting early stages of HKD.

3.1.4. Echogenicity

Renal echogenicity is assessed by comparing it with that of adjacent solid organs—the liver on the right and the spleen on the left. Increased echogenicity serves as a marker of progressive renal disease and is typically observed in advanced parenchymal damage. Studies have shown that echogenicity correlates more strongly with eGFR than either renal length or cortical thickness in patients with CKD or hypertension [24,25,26,27].

A reduction in renal dimensions (both length and parenchymal thickness) combined with increased echogenicity is characteristic of progressive CKD [27]. Despite this finding was revealed in studies on hypertensive individuals, it remains nonspecific and influenced by multiple factors, which limits the diagnostic utility of these parameters in identifying early stages or distinguishing etiologically distinct forms of renal damage [22,28]. Therefore, interpretation of ultrasound findings should always be contextualized with previous imaging studies, biochemical parameters, blood pressure control and antihypertensive treatment requirements.

Table 1.

Comparison of current guidelines in terms of cut-off levels of RAR, PSV, RRI, and difference in kidney size.

Table 1.

Comparison of current guidelines in terms of cut-off levels of RAR, PSV, RRI, and difference in kidney size.

| Guidelines | RAR | PSV | RRI | Kidney Size Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension, 2019 [29] | >3.5 | >180–200 | - | - |

| Hypertension Canada’s Comprehensive Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults and Children, 2020 [30] | - | - | - | >1.5 |

| AHA/ACC Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults, 2025 [31] | - | - | - | - |

| ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension, 2024 [32] | >3.5 | >200 | >0.05 difference between kidneys | >0.5 |

| ESH Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension, 2023 [33] | - | - | >0.7 | - |

| 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases [34] | - | - | <0.6 and >0.7 | - |

| ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease [35] | >3.5 | >180–200 | >0.15 difference between kidneys | - |

3.2. Renal Flow Parameters

3.2.1. Renal Resistive Index

A useful method for assessing renal function is the RRI, calculated from the ratio of blood flow velocities in intrarenal arteries according to the following formula:

RRI—renal resistive index; PSV—peak systolic velocity; EDV—end-diastolic velocity.

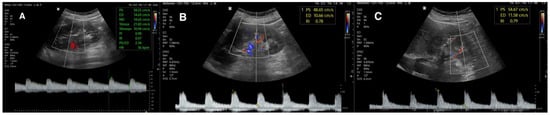

The measurement is performed using pulsed-wave Doppler and Color Doppler at the border between the interlobar and arcuate arteries and should optimally represent the mean of several measurements [36,37]. Since RRI is derived from a velocity ratio, it is independent of the insonation angle, enhancing its reproducibility and clinical utility [37,38]. Furthermore, because renal visualization is generally straightforward, this parameter can be obtained reliably even by operators with limited training, supporting its feasibility and applicability in routine clinical practice [39]. Normal and elevated RRI values are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(A) Normal DUS of intrarenal vasculature; (B,C) increased RRI.

RRI values are influenced by several factors, including sex, age [40] salt intake [41], and both extrarenal (pulse pressure, atherosclerosis, vascular compliance) and intrarenal determinants (interstitial pressure, vascular compliance, arterial stiffness) [42]. Consequently, RRI reflects not only renal vascular status but also the overall vascular condition, making it a potential marker of cardiovascular risk, aiding clinical decisions in the hypertensive population.

In healthy individuals, the mean RRI value is typically <0.7 [36]. Many authors adopt 0.7 [43,44,45,46,47], as the upper reference limit, while others suggest 0.8 [48,49]. However, given the increase in RRI with age and its slightly higher values in women, a universal cutoff is difficult to establish. Ponte et al. [40] reported mean RRI values of 0.62 in men and 0.64 in women, noting that in 10% of women over 60 years old, RRI was ≥0.7, emphasizing the need for demographic adjustments in interpretation.

An elevated RRI reflects increased vascular resistance within the renal arteries, leading to impaired renal perfusion, which may result from glomerular fibrosis or arterial stiffness, including those of hypertensive etiology. This relationship is supported by the correlation between RRI and pulse pressure, though some authors argue that the diastolic-to-systolic pressure ratio may better represent this association [50].

RRI is also valuable for cardiovascular risk stratification in hypertensive patients.

Geraci et al. [51] demonstrated that RRI values > 0.67 (based on the Framingham risk score) and >0.65 (based on the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease risk scale) were associated with a ≥20% cardiovascular risk. Moreover, RRI correlates with ocular hypertensive complications; values > 0.66 were linked to reduced vascular density in the deep foveal plexus among non-diabetic patients, though the study was limited by small sample size [52]. Therefore, even modest increases below the 0.7 threshold should prompt comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment.

Kotruchin et al. [48] found that RRI ≥ 0.8 in patients receiving intensive antihypertensive therapy was associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular events, suggesting its potential utility in defining blood pressure treatment targets. Berni et al. [47] observed a correlation between RRI and CRP levels in hypertensive patients, further highlighting the relationship between inflammation and renal hemodynamics.

Importantly, RRI elevation occurs earlier than albuminuria, making it a potentially valuable marker for identifying patients who may benefit from early therapeutic intervention and risk factor modification [17]. Miyoshi et al. [45] proposed an RRI cutoff of 0.71, predicting microalbuminuria with 84.4% sensitivity and 52.4% specificity; however, the study was retrospective and included a limited number of patients, including individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Studies reporting associations between RRI and various clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 2.

Several studies have explored the predictive role of RRI < 0.8 for improved blood pressure control after renal artery revascularization [49], though the evidence remains inconsistent.

Comparing RRI between kidneys can also aid in diagnosing unilateral RAS. According to the 2024 ESC Guidelines, a difference of ≥0.05 between kidneys suggests significant stenosis [53], though newer data indicate that a difference of 0.04 may already be clinically meaningful [54]. Nonetheless, not all studies support the diagnostic utility of Doppler parameters alone in determining stenosis significance [55]. While RRI should not be used as the sole criterion for angioplasty qualification, baseline RRI values may help predict revascularization outcomes [56].

In summary, the RRI is a readily available, reproducible, and noninvasive parameter capable of detecting early renal hemodynamic impairment. Its independence from the Doppler insonation angle and the broad accessibility of renal ultrasonography make RRI a valuable diagnostic and monitoring tool in HKD and cardiovascular risk assessment, supporting its use in routine clinical practice.

Table 2.

Factors associated with RRI and proposed values. Not all studies were included in this table.

Table 2.

Factors associated with RRI and proposed values. Not all studies were included in this table.

| Author | Values | Associated Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Carollo C, 2025 [52] | >0.66 | Foveolar vascular density decrease in hypertensive patients |

| Geraci G, 2025 [51] | >0.67 and >0.65 | High risk score in Framingham risk scale and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease risk scale |

| Cianci R, 2023 [56] | > 0.75 | Renal function worsening after percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty |

| Kotruchin P, 2019 [48] | >0.8 | Higher cardiovascular events rate in intensively hypotensive treated patients |

| Miyoshi K, 2017 [45] | >0.71 | Predictor of microalbuminuria |

| Gaipov A, 2016 [57] | - | RRI as independent predictor of decreased renal functional reserve |

| Berni A, 2012 [47] | >= 0.70 | Positive correlation with high-sensitive C-reactive protein in hypertensive patients |

3.2.2. Peak Systolic Velocity and Renal–Aortic Ratio

The evaluation of renal arteries using the renal–aortic ratio (RAR) represents an important diagnostic approach in detecting and quantifying RAS. The ratio is expressed by the following formula:

RAR—renal-to-aortic ratio; PSVRA—renal artery peak systolic velocity; PSVAo—aortic peak systolic velocity

Major scientific societies recommend Doppler ultrasonography (DUS) as the first-line diagnostic method in RAS evaluation, given its high sensitivity (84–98%) and specificity (62–99%) [29], Nevertheless, CT angiography continues to be regarded as the gold standard in the diagnostic confirmation of RAS [33,53].

The limitations of DUS in renal artery assessment primarily stem from aortic pathologies (such as aneurysm or atherosclerosis) or low aortic flow velocities (<40 cm/s) [37]. Furthermore, the procedure is technically demanding, requiring substantial operator experience. Complete visualization of the entire renal artery course may be challenging, particularly in patients with intestinal gas interference or obesity [37,58].

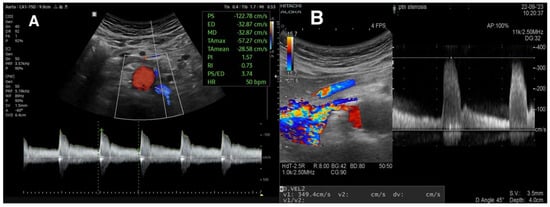

Current guidelines recommend using a peak systolic velocity (PSV) threshold of 200 cm/s in the renal artery [53]. However, some publications do not specify a preferred Doppler criterion for hemodynamically significant stenosis [33]. Recent study suggests that the traditional cut-off values of RAR > 3.5 and PSV > 200 cm/s may be insufficient, supporting revised thresholds of RAR > 4.495 and PSV > 241.5 cm/s [54]. To demonstrate both normal and elevated PSV and RAR values, Doppler measurements are presented in Figure 3. Alternative indices—such as the renal-to-interlobar ratio (RIR), renal-to-segmental ratio (RSR), and renal-to-renal ratio (RRR)—compare flow velocities across different segments of the renal arterial tree. These measures may help overcome the limitations of RAR while maintaining strong diagnostic performance [59,60,61].

Figure 3.

(A) Normal flow spectrum of left renal artery. Considering an aortic PSV of 100 cm/s, RAR is 1.2. (B) Spectrum of right renal artery. PSV is 349 cm/s, which suggests significant RAS.

A meta-analysis by Shivgulam et al. demonstrated that contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) achieves high sensitivity (98%) and good specificity (87.5%) in RAS detection [62]. This technique shows promise for patients with contraindications to angiography, although its widespread clinical use is limited by equipment requirements and the need for operator experience. Methodological inconsistencies and variability in contrast agents among studies underscore the necessity for further research and standardization of this approach.

3.2.3. Acceleration Time and Acceleration Index

Acceleration time (AT) in DUS of the renal arteries represents an indirect hemodynamic parameter of renal perfusion and is used in the diagnosis of RAS. AT is defined as the time interval from the onset of systolic flow to the attainment of PSV, reflecting a delayed systolic upstroke in kidneys affected by significant proximal arterial narrowing and creating “tardus-et-parvus” waveform. Values of AT exceeding 60–70 ms in segmental or interlobar arteries are generally indicative of hemodynamically significant RAS, particularly when accompanied by a decreased acceleration index below 3 m/s2 [35,63,64]. Although there is evidence about diagnostic performance of these parameters [63], majority found them in secondary place in assessing RAS [64,65,66].

In summary, DUS is a valuable diagnostic tool in the evaluation of RAS, but interpretation should not rely on a single parameter. Assessment should incorporate multiple Doppler parameters, and RAR evaluation must be approached with caution. Given the technical challenges in accurate vessel visualization and measurement, this examination should be conducted by experienced ultrasonographers to ensure diagnostic reliability and reproducibility. Table 1 provides a summary of guideline-recommended cut-offs for different DUS parameters.

4. Shear-Wave Elastography

SWE is a noninvasive imaging technique based on the emission of a short ultrasonic pulse that induces tissue deformation, followed by the measurement of the propagation velocity of the resulting shear wave, which is directly related to the stiffness of the assessed tissue [67]. Over the past years, multiple SWE-based technologies have been developed, differing in acquisition methods and technical limitations [68]. Recent studies investigating SWE application in renal imaging have shown promising results. Most of them report good intra- and inter-observer reproducibility [69,70]. The measurements appear to be largely independent of age and sex [71,72,73], although some data remain inconsistent [69,74]. Current research increasingly focuses on the use of SWE in CKD and in evaluating renal transplant function and rejection [67].

Although studies applying SWE in hypertensive patients are still limited, this method offers novel diagnostic opportunities, especially for characterizing renal damage and detecting early stages of HKD. A recent prospective study found that renal cortical stiffness quantified by SWE was significantly higher in patients with essential hypertension compared to age- and sex-matched healthy controls, and that the degree of stiffness correlated positively with the duration of hypertension, suggesting SWE’s potential to detect subclinical renal changes before conventional parameters become abnormal [75].

Currently, renal biopsy remains the only method capable of assessing the degree of renal fibrosis, but it is invasive and carries a risk of complications. SWE thus represents a potentially valuable noninvasive adjunct for more precise characterization of renal structural changes, early HKD detection, and longitudinal monitoring of disease progression.

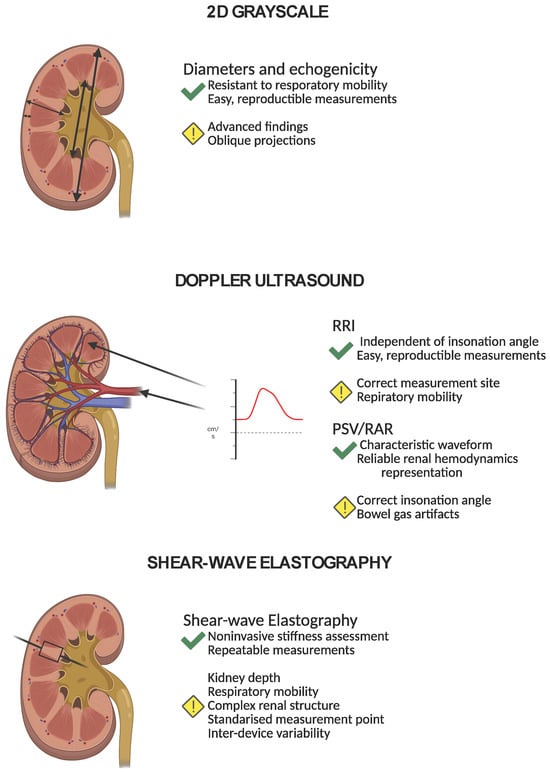

A summarized comparison of grayscale ultrasound, Doppler techniques, and shear-wave elastography is presented in Figure 4 to illustrate the key principles, advantages, and limitations of each method discussed above.

Figure 4.

A summarized comparison of 2D grayscale ultrasound, Doppler techniques, and shear-wave elastography. The figure illustrates the key principles, advantages, and limitations of each method discussed above.

4.1. SWE in CKD

The number of studies evaluating the diagnostic efficacy of SWE in assessing renal fibrosis has been steadily increasing. Most evidence supports its utility in CKD diagnosis [69,70,76,77,78], although study populations and technical approaches to stiffness quantification differ considerably.

A meta-analysis by Mo et al. [78] confirmed the effectiveness of SWE for noninvasive renal fibrosis assessment but emphasized that results should be interpreted individually, given the heterogeneous etiologies of renal failure.

Leong et al. [69] demonstrated that SWE outperforms conventional ultrasonographic parameters, such as kidney length or cortical thickness, in detecting CKD, indicating its value for identifying early parenchymal changes. Similarly, Hu et al. [70] compared SWE findings with conventional ultrasound and histopathology from renal biopsies, showing that shear-wave velocity differed significantly even at mild fibrosis stages, despite no differences in kidney length, cortical thickness, or RRI. They proposed a cutoff value of 2.65 m/s, detecting mild fibrosis with 63.8% sensitivity and 75% specificity, while for advanced fibrosis, a cutoff of 2.33 m/s yielded 96.4% sensitivity and 78.4% specificity. These findings have been confirmed by other studies [77].

Despite these encouraging results, some reports question the consistency and reliability of SWE in renal fibrosis evaluation [79,80], underscoring the need for further multicenter studies and standardization.

4.2. Limitations

4.2.1. Inter-Device Variability

The application of shear-wave elastography (SWE) requires dedicated ultrasound equipment, and differences between devices—including hardware, software algorithms, and calibration settings—can lead to significant inter-device variability. This variability complicates the comparison of quantitative measurements across centers and studies, potentially introducing bias or misinterpretation of results. Standardization of equipment and reporting protocols is therefore critical to improve cross-study reliability.

4.2.2. Depth of Acquisition

SWE accuracy is significantly affected by the depth of assessed tissue. With increasing depth, ultrasound beam attenuation reduces the amplitude and quality of the shear waves, resulting in higher measurement errors [67,73]. This limitation is particularly relevant in obese patients, where deeper renal parenchyma may be less reliably assessed, and the success rate of obtaining reproducible readings decreases. Adjustments in transducer frequency, focus, and acquisition technique can partially mitigate these effects, but deep tissue assessment remains a challenge.

4.2.3. Renal Structure

The complex architecture of the kidney also introduces measurement variability. The fibrous renal capsule can influence shear-wave propagation, and its effects may vary with physiological factors such as blood pressure [81,82] or urine volume within the pelvicalyceal system [82,83]. Moreover, kidney mobility during respiration can impair accurate SWE acquisition, especially in patients unable to perform consistent breath-hold maneuvers. The highly organized parenchymal structure, including cortical and medullary regions, requires that measurements be taken at defined anatomical locations to ensure meaningful and reproducible results [67,81].

4.2.4. Operator Dependence and Standardization

Renal SWE requires both operator expertise and strict adherence to standardized acquisition protocols. Adequate training is essential to reduce intra- and inter-observer variability. To improve measurement reliability, repeated acquisitions with averaging of stiffness values, appropriate patient positioning, and controlled respiratory conditions are recommended. Furthermore, harmonization of SWE acquisition parameters—including ultrasound system settings, transducer selection, region-of-interest placement within the renal parenchyma, and acquisition depth—is critical to ensure reproducibility and enable meaningful comparisons across patients, devices, and studies.

4.2.5. Clinical Implications

While SWE offers a promising approach for quantitative assessment of renal stiffness and may aid in the early detection of renal pathology, its technical limitations should be carefully considered in both research and clinical practice. Interpretation of SWE data requires awareness of potential sources of error, and it is advisable to use SWE alongside conventional ultrasonography and clinical parameters rather than as a standalone diagnostic tool.

5. Gaps in Evidence

Despite the widespread use of ultrasonography and increasing interest in SWE for the evaluation of HKD, several important limitations and gaps remain in the current literature.

5.1. Lack of Disease-Specific Diagnostic Criteria

Conventional renal ultrasound parameters—including kidney size, cortical thickness, and echogenicity—are widely available and easily reproducible but lack disease specificity. Similar morphological alterations can be observed in different renal pathologies, limiting their ability to distinguish HKD from other causes of chronic kidney disease. These limitations provide the rationale for the development of SWE, which aims to offer a quantitative assessment of renal tissue stiffness as a surrogate marker of renal fibrosis and structural remodeling.

5.2. Validation

While SWE represents a promising extension of conventional ultrasonography, its role in HKD has not yet been fully established. Most studies applying renal SWE have included heterogeneous populations or lacked robust reference standards, such as histopathology. Consequently, it remains unclear whether SWE-derived stiffness measurements can reliably identify hypertensive-specific renal injury or differentiate HKD from other chronic renal disorders.

5.3. Variability

Technical variability among devices leads to inconsistent shear-wave velocity measurements and differing diagnostic performance in identifying kidney disease [84]. This highlights the need for further validation, standardization, and the establishment of population-specific reference values.

5.4. Heterogeneity of Study Populations

Most studies evaluating renal ultrasound and SWE have been cross-sectional and conducted in populations with diverse etiologies of kidney disease. This heterogeneity limits the interpretation of findings specifically related to HKD. Moreover, longitudinal data linking SWE measurements with disease progression, renal function decline, or cardiovascular outcomes are scarce, preventing firm conclusions regarding its prognostic value. Finally, most available studies are limited by short follow-up durations, restricting our understanding of how ultrasound and elastographic parameters correlate with disease progression and complications over the long term.

5.5. Clinical Impact

Although renal SWE has shown promise in detecting early structural alterations and increased renal stiffness, current evidence does not yet demonstrate that SWE-guided assessment leads to improved therapeutic decision-making or superior long-term clinical outcomes in patients with HKD.

6. Conclusions

Ultrasonography, including Doppler assessment of intrarenal hemodynamics, remains an important and noninvasive tool in the evaluation of HKD. Parameters such as renal length, cortical thickness, echogenicity, and RRI provide important information on renal structure and early hemodynamic alterations; however, their diagnostic specificity is limited and influenced by a range of physiological and pathological factors. Doppler-derived indices, including RAR, enhance the detection of RAS but require operator expertise and careful interpretation.

SWE represents a promising extension of conventional renal ultrasound, offering a quantitative, noninvasive assessment of renal tissue stiffness as a potential surrogate marker of fibrosis. It may allow detection of early structural changes that precede functional impairment measured by eGFR or albuminuria. Nevertheless, current evidence is constrained by heterogeneous study populations, short follow-up durations, and substantial inter-device variability. Importantly, there is insufficient evidence demonstrating that SWE-guided assessment directly influences therapeutic decision-making or improves long-term clinical outcomes in patients with HKD.

Overall, conventional ultrasonography and SWE provide complementary information that may support early detection and monitoring of hypertensive renal injury. However, neither modality can replace histopathological assessment or serve as a standalone diagnostic criterion. Further standardization, disease-specific validation, and well-designed longitudinal studies are required to define the precise role of renal ultrasound and SWE in the clinical management of HKD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ł.L.; methodology, Ł.L., J.L. and Ł.A.; investigation, Ł.L. and K.S.; resources, Ł.L. and Ł.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Ł.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and Ł.A.; visualization, Ł.L. and Ł.A.; supervision, J.L. and Ł.A.; project administration, Ł.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was supported by the Publication Fund of the Medical University of Warsaw.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge every person who contributed to or supported this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AT | acceleration time |

| CEUS | contrast-enhanced ultrasound |

| CKD | chronic kidney disease |

| DUS | Doppler ultrasound |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ESKD | end-stage kidney disease |

| HKD | hypertensive kidney disease |

| KRT | kidney replacement therapy |

| PSV | peak systolic velocity |

| RAR | renal–aortic ratio |

| RSR | renal–segmental ratio |

| RIR | renal–interlobar ratio |

| RRI | renal resistive index |

| RRR | renal to renal ratio |

| SWE | shear-wave elastography |

References

- ERA Registry. ERA Registry Annual Report 2022; European Renal Association: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, N.R.; Koyama, A.; Pavkov, M.E. Reported Cases of End-Stage Kidney Disease—United States, 2000–2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlessinger, S.D.; Tankersley, M.R.; Curtis, J.J. Clinical documentation of end-stage renal disease due to hypertension. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1994, 23, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasz Stompór, A.P.-P. Hypertensive kidney disease: A true epidemic or rare disease? Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2020, 130, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarif, L.; Covic, A.; Iyengar, S.; Sehgal, A.R.; Sedor, J.R.; Schelling, J.R. Inaccuracy of clinical phenotyping parameters for hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2000, 15, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriazo, S.; Perez-Gomez, M.V.; Ortiz, A. Hypertensive nephropathy: A major roadblock hindering the advance of precision nephrology. Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 13, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delure, C.; Speeckaert, M.M. Beyond Blood Pressure: Emerging Pathways and Precision Approaches in Hypertension-Induced Kidney Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janki, S.; Kimenai, H.J.A.N.; Dijkshoorn, M.L.; Looman, C.W.N.; Dwarkasing, R.S.; IJzermans, J.N.M. Validation of Ultrasonographic Kidney Volume Measurements: A Reliable Imaging Modality. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2018, 16, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.L.; Nielsen, M.B.; Ewertsen, C. Ultrasonography of the Kidney: A Pictorial Review. Diagnostics 2015, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamian, S.A.; Nielsen, M.B.; Pedersen, J.F.; Ytte, L. Kidney dimensions at sonography: Correlation with age, sex, and habitus in 665 adult volunteers. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1993, 160, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terreros, P.; Alberton, V.; Heguilen, R.; Lococo, B.; Martinez, J.; Sanchez, M.; Flores, A.; Chidid, I.; Loor, A.; Burna, L.; et al. WCN24-1079 Kidneys Sizen by Ultrasound: Correlation Between Anthropometric, Renal Sclerosis and Glomerular Filtration Rate. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, S257–S258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryaki, S.; Aksu, Y. Ultrasonographic Evaluation of Normal Liver, Spleen, and Kidney Dimensions in a Healthy Turkish Community of over 18 Years Old. Curr. Med. Imaging 2023, 20, e220523217203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Singh, A.; Kaur, R.; D’cRuz, S. Kidney Dimensions and its Correlation with Anthropometric Parameters in Healthy North Indian Adults. Indian J. Nephrol. 2024, 34, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Reshaid, W.; Abdul-Fattah, H. Sonographic assessment of renal size in healthy adults. Med. Princ. Pract. 2014, 23, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, M.; Wasserman, P. Changes in sizes and distensibility of the aging kidney. Br. J. Radiol. 1981, 54, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, N.P.; Abbas, F.; Biyabani, S.R.; Afzal, M.; Javed, Q.; Rizvi, I.; Talati, J. Ultrasonographic renal size in individuals without known renal disease. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2000, 50, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gigante, A.; Perrotta, A.M.; De Marco, O.; Rosato, E.; Lai, S.; Cianci, R. Sonographic evaluation of hypertension: Role of atrophic index and renal resistive index. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2022, 24, 955–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artyszuk, Ł.; Symonides, B.; Gaciong, Z.; Cienszkowska, K.; Ludwiczak, M.; Wrzaszczyk, M.; Szmigielski, C.A. A new threshold for kidney asymmetry improves association with abnormal renal-aortic ratio for diagnosis of renal artery stenosis. Vasc. Med. 2022, 27, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safian, R.D.; Textor, S.C. Renal-artery stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommart, S.; Cliche, A.; Therasse, E.; Giroux, M.-F.; Vidal, V.; Oliva, V.L.; Soulez, G. Renal artery revascularization: Predictive value of kidney length and volume weighted by resistive index. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 194, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, W.C. Renal relevant radiology: Use of ultrasound in kidney disease and nephrology procedures. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 9, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mythreesha, S.K.; Divya, G.A.; Panchami, P. Correlation of Chronic Kidney Disease with USG Features like Cortical Echogenicity and Echotexture in Patients with Hypertension. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 15, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mounier-Vehier, C.; Lions, C.; Devos, P.; Jaboureck, O.; Willoteaux, S.; Carre, A.; Beregi, J.-P. Cortical thickness: An early morphological marker of atherosclerotic renal disease. Kidney Int. 2002, 61, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddappa, J.K.; Singla, S.; Al Ameen, M.; Rakshith, S.; Kumar, N. Correlation of ultrasonographic parameters with serum creatinine in chronic kidney disease. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2013, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Bughio, S.; Hassan, M.; Lal, S.; Ali, M. Role of Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease and its Correlation with Serum Creatinine Level. Cureus 2019, 11, e4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Kunwar, L.; Bc, B.; Gupta, A. Correlation of Ultrasonographic Parameters with Serum Creatinine and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate in Patients with Echogenic Kidneys. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2020, 18, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwafor, N.; Adeyekun, A.; Adenike, O. Sonographic evaluation of renal parameters in individuals with essential hypertension and correlation with normotensives. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, G.; Shem, L.; Abba, M.; Bature, S.; Sidi, M.; Emmanuel, R.I.; Umar, M.; Joseph, D.; Yusuf, A.; Ohagwu, C.; et al. Sonographic Renal Dimension in Patients with Essential Hypertension in Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Teaching Hospital, Bauchi, Nigeria. J. Appl. Health Sci. 2020, 6, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, S.; Arima, H.; Arima, S.; Asayama, K.; Dohi, Y.; Hirooka, Y.; Horio, T.; Hoshide, S.; Ikeda, S.; Ishimitsu, T.; et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens. Res. 2019, 42, 1235–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabi, D.M.; McBrien, K.A.; Sapir-Pichhadze, R.; Nakhla, M.; Ahmed, S.B.; Dumanski, S.M.; Butalia, S.; Leung, A.A.; Harris, K.C.; Cloutier, L.; et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2020 Comprehensive Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults and Children. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 596–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Writing Committee Members; Jones, D.W.; Ferdinand, K.C.; Taler, S.J.; Johnson, H.M.; Shimbo, D.; Abdalla, M.; Altieri, M.M.; Bansal, N.; Bello, N.A.; et al. 2025 AHA/ACC/AANP/AAPA/ABC/ACCP/ACPM/AGS/AMA/ASPC/NMA/PCNA/SGIM Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2025, 82, e212–e316. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M.D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Gerdts, E.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3912–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunström, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E.A.E.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J. Hypertens. 2023, 41, 1874–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Aboyans, V.; Ricco, J.B.; Bartelink, M.E.L.; Bjorck, M.; Brodmann, M.; Cohnert, T.; Collet, J.-P.; Czerny, M.; De Carlo, M.; Debus, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: The European Stroke Organization (ESO)The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 763–816. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, A.T.; Haskal, Z.J.; Hertzer, N.R.; Bakal, C.W.; Creager, M.A.; Halperin, J.L.; Hiratzka, L.F.; Murphy, W.R.C.; Olin, J.W.; Puschett, J.B.; et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): A collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease): Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006, 113, e463–e654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Darabont, R.; Mihalcea, D.; Vinereanu, D. Current Insights into the Significance of the Renal Resistive Index in Kidney and Cardiovascular Disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeller, T.; Bonvini, R.F.; Sixt, S. Color-coded duplex ultrasound for diagnosis of renal artery stenosis and as follow-up examination after revascularization. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2008, 71, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Hentel, K.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, T.; Shih, G.; Mennitt, K.; Min, R. Doppler angle correction in the measurement of intrarenal parameters. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2011, 4, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renberg, M.; Kilhamn, N.; Lund, K.; Hertzberg, D.; Rimes-Stigare, C.; Bell, M. Feasibility of renal resistive index measurements performed by an intermediate and novice sonographer in a volunteer population. Ultrasound J. 2020, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, B.; Pruijm, M.; Ackermann, D.; Vuistiner, P.; Eisenberger, U.; Guessous, I.; Rousson, V.; Mohaupt, M.G.; Alwan, H.; Ehret, G.; et al. Reference values and factors associated with renal resistive index in a family-based population study. Hypertension 2014, 63, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaques, D.A.; Pruijm, M.; Ackermann, D.; Vogt, B.; Guessous, I.; Burnier, M.; Pechere-Bertschi, A.; Bochud, M.; Ponte, B. Sodium Intake Is Associated with Renal Resistive Index in an Adult Population-Based Study. Hypertension 2020, 76, 1898–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikou, I.; Tsioufis, C.; Konstantinidis, D.; Kasiakogias, A.; Dimitriadis, K.; Leontsinis, I.; Andrikou, E.; Sanidas, E.; Kallikazaros, I.; Tousoulis, D. Renal resistive index in hypertensive patients. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2018, 20, 1739–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafori, M.; Rashedi, A.; Montazeri, M.; Amirkhanlou, S. The Relationship Between Renal Arterial Resistive Index (RRI) and Renal Outcomes in Patients with Resistant Hypertension. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 14, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Toledo, C.; Thomas, G.; Schold, J.D.; Arrigain, S.; Gornik, H.L.; Nally, J.V.; Navaneethan, S.D. Renal resistive index and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Hypertension 2015, 66, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, K.; Okura, T.; Tanino, A.; Kukida, M.; Nagao, T.; Higaki, J. Usefulness of the renal resistive index to predict an increase in urinary albumin excretion in patients with essential hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2017, 31, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitsumoto, T. Correlation Between the Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index and Renal Resistive Index in Patients with Essential Hypertension. Cardiol. Res. 2020, 11, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, A.; Ciani, E.; Bernetti, M.; Cecioni, I.; Berardino, S.; Poggesi, L.; Abbate, R.; Boddi, M. Renal resistive index and low-grade inflammation in patients with essential hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2012, 26, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotruchin, P.; Hoshide, S.; Ueno, H.; Komori, T.; Kario, K. Lower Systolic Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Event Risk Stratified by Renal Resistive Index in Hospitalized Cardiovascular Patients: J-VAS Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2019, 32, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radermacher, J.; Chavan, A.; Bleck, J.; Vitzthum, A.; Stoess, B.; Gebel, M.J.; Galanski, M.; Koch, K.M.; Haller, H. Use of Doppler ultrasonography to predict the outcome of therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveceny, J.; Charvat, J.; Hrach, K.; Horackova, M.; Schuck, O. In essential hypertension, a change in the renal resistive index is associated with a change in the ratio of 24-hour diastolic to systolic blood pressure. Physiol. Res. 2022, 71, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraci, G.; Sorce, A.; Zanoli, L.; Calabrese, V.; Cuttone, G.; Mattina, A.; Ferrara, P.; Dominguez, L.J.; Polosa, R.; Mulè, G.; et al. Renal Resistive Index and 10-Year Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Predicted by Framingham Risk Score and Pooled Cohort Equations: An Observational Study in Hypertensive Individuals Without Cardiovascular Disease. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2025, 32, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carollo, C.; Vadalà, M.; Sorce, A.; Sinatra, N.; Orlando, E.; Cirafici, E.; Bennici, M.; Polosa, R.; Bonfiglio, V.M.E.; Mulè, G.; et al. Relationship Between Renal Resistive Index and Retinal Vascular Density in Individuals with Hypertension. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzolai, L.; Teixido-Tura, G.; Lanzi, S.; Boc, V.; Bossone, E.; Brodmann, M.; Bura-Rivière, A.; De Backer, J.; Deglise, S.; Corte, A.D.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3538–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Li, Y.; Duan, X.; Lv, N.; Meng, Y.; Zhou, F.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Assessment of renal artery stenosis using renal fractional flow reserve and correlation with angiography and color Doppler ultrasonography: Data from FAIR-pilot trial. Hypertens. Res. 2025, 48, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadziela, J.; Witkowski, A.; Januszewicz, A.; Cedro, K.; Michałowska, I.; Januszewicz, M.; Kabat, M.; Prejbisz, A.; Kalińczuk, Ł.; Zieleń, P.; et al. Assessment of renal artery stenosis using both resting pressures ratio and fractional flow reserve: Relationship to angiography and ultrasonography. Blood Press. 2011, 20, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, M.; Cianci, R.; Gigante, A.; Perrotta, A.M.; Ronchey, S.; Mangialardi, N.; Schioppa, A.; De Marco, O.; Cianci, E.; Barbati, C.; et al. Renal Stem Cells, Renal Resistive Index, and Neutrophil Gelatinase Associated Lipocalin Changes After Revascularization in Patients with Renovascular Hypertension and Ischemic Nephropathy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaipov, A.; Solak, Y.; Zhampeissov, N.; Dzholdasbekova, A.; Popova, N.; Molnar, M.Z.; Tuganbekova, S.; Iskandirova, E. Renal functional reserve and renal hemodynamics in hypertensive patients. Ren. Fail. 2016, 38, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, U.; Edwards, J.M.; Carter, S.; Goldman, M.L.; Harley, J.D.; Zaccardi, M.J.; Strandness, D.E. Role of duplex scanning for the detection of atherosclerotic renal artery disease. Kidney Int. 1991, 39, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granata, A.; Fiorini, F.; Andrulli, S.; Logias, F.; Gallieni, M.; Romano, G.; Sicurezza, E.; Fiore, C. Doppler ultrasound and renal artery stenosis: An overview. J. Ultrasound 2009, 12, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.C.; Jiang, Y.X.; Zhang, S.Y.; Wang, L.; Ouyang, Y.S.; Qi, Z.H. Evaluation of renal artery stenosis with hemodynamic parameters of Doppler sonography. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 48, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, J. Application of simple ultrasound Doppler hemodynamic parameters in the diagnosis of severe renal artery stenosis in routine clinical practice. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2023, 13, 8042–8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivgulam, M.E.; Liu, H.; Kivell, M.J.; MacLeod, J.R.; O’BRien, M.W. Effectiveness of contrast-enhanced duplex ultrasound for detecting renal artery stenosis: A systematic review. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2024, 52, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdick, L.; Airoldi, F.; Marana, I.; Giussani, M.; Alberti, C.; Cianci, M.; Lovaria, A.; Saccheri, S.; Gazzano, G.; Morganti, A. Superiority of acceleration and acceleration time over pulsatility and resistance indices as screening tests for renal artery stenosis. J. Hypertens. 1996, 14, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, M.K.; Dowling, R.J.; King, P.; Gibson, R.N. Using Doppler sonography to reveal renal artery stenosis: An evaluation of optimal imaging parameters. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1999, 173, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.J.; Macaskill, P.; Chan, S.F.; Karplus, T.E.; Yung, W.; Hodson, E.M.; Craig, J.C. Comparative accuracy of renal duplex sonographic parameters in the diagnosis of renal artery stenosis: Paired and unpaired analysis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007, 188, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatresi, S.; Longari, V.; Airoldi, F.; Benti, R.; Nador, B.; Bencini, C.; Lovaria, A.; Del Vecchio, C.; Nicolini, A.; Voltini, F.; et al. Usefulness and limits of distal echo-Doppler velocimetric indices for assessing renal hemodynamics in stenotic and non-stenotic kidneys. J. Hypertens. 2001, 19, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigrist, R.M.S.; Liau, J.; Kaffas, A.E.; Chammas, M.C.; Willmann, J.K. Ultrasound Elastography: Review of Techniques and Clinical Applications. Theranostics 2017, 7, 1303–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.H.; Wong, J.H.D.; Leong, S.S. Shear wave elastography in chronic kidney disease—The physics and clinical application. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2024, 47, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.S.; Wong, J.H.D.; Shah, M.N.M.; Vijayananthan, A.; Jalalonmuhali, M.; Ng, K.H. Shear wave elastography in the evaluation of renal parenchymal stiffness in patients with chronic kidney disease. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20180235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, X.Y.; He, H.G.; Wei, H.M.; Kang, L.K.; Qin, G.C. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging for non-invasive assessment of renal histopathology in chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kula, S.; Haliloglu, N. Comparison of Shear Wave Elastography Measurements in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients and Healthy Volunteers. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2025, 53, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Ma, Y.; Ju, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. The application of shear wave quantitative ultrasound elastography in chronic kidney disease. Technol. Health Care 2024, 32, 2951–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Panta, O.B.; Khanal, U.; Ghimire, R.K. Renal Cortical Elastography: Normal Values and Variations. J. Med. Ultrasound 2017, 25, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.H.; Xu, H.X.; Fu, H.J.; Peng, A.; Zhang, Y.F.; Liu, L.N. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging for noninvasive evaluation of renal parenchyma elasticity: Preliminary findings. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Wang, L.; Luo, J. Application of shear wave elastography in the assessment of renal cortical elasticity in patients with hypertension. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1624558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Loberant, N.; Abbas, N.; Fadi, H.; Shadia, H.; Khazim, K. Shear wave elastography imaging for assessing the chronic pathologic changes in advanced diabetic kidney disease. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2016, 12, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zang, S.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, M.; Chen, S. Shear-Wave Elastography Improves Diagnostic Accuracy in Chronic Kidney Disease Compared to Conventional Ultrasound. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2025, 53, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, X.L.; Meng, H.Y.; Wu, Y.Y.; Wei, X.Y.; Li, Z.K.; Yang, S.Q. Shear Wave Elastography in the Evaluation of Renal Parenchymal Stiffness in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2022, 14, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xia, P.; Lv, K.; Han, J.; Dai, Q.; Li, X.M.; Chen, L.M.; Jiang, Y.X. Assessment of renal tissue elasticity by acoustic radiation force impulse quantification with histopathological correlation: Preliminary experience in chronic kidney disease. Eur. Radiol. 2014, 24, 1694–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipov, T.; Teutsch, B.; Szabó, A.; Forintos, A.; Ács, J.; Váradi, A.; Hegyi, P.; Szarvas, T.; Ács, N.; Nyirády, P.; et al. Investigating the role of ultrasound-based shear wave elastography in kidney transplanted patients: Correlation between non-invasive fibrosis detection, kidney dysfunction and biopsy results-a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nephrol. 2024, 37, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, K.; Ogata, A.; Tanaka, K.; Ide, Y.; Sankoda, A.; Kawakita, C.; Nishikawa, M.; Ohmori, K.; Kinomura, M.; Shimada, N.; et al. Acoustic radiation force impulse elastography of the kidneys: Is shear wave velocity affected by tissue fibrosis or renal blood flow? J. Ultrasound Med. 2014, 33, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, N.; Xu, T.; Sun, F.; Li, R.; Gao, Q.; Chen, L.; Wen, C. Effect of renal perfusion and structural heterogeneity on shear wave elastography of the kidney: An in vivo and ex vivo study. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, B.; Kim, M.J.; Han, S.W.; Im, Y.J.; Lee, M.J. Shear wave velocity measurements using acoustic radiation force impulse in young children with normal kidneys versus hydronephrotic kidneys. Ultrasonography 2014, 33, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhya; Bansal, L.; Prasad, A.; Mehra, S. Role of 2D shear wave elastography in assessing chronic kidney disease and its correlation with point shear wave elastography and eGFR. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2025, 57, 2697–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.