Emotion-Enhanced Dual-Agent Recommendation: Understanding and Leveraging Cognitive Conflicts for Better Personalization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- “Cognitive Dissonance” Pattern: This conflict refers to the divergence between users’ ratings and the emotions expressed in their reviews. For example, a user gives a movie a rating of two (out of five), but writes in the review, “I did enjoy the film. The visuals were beautiful as were all the costumes. The actors themselves were fantastic,” reflecting an internal contradiction between rating behavior and emotional experience.

- “Hate-Watching” Pattern: This conflict refers to users continuing to consume similar content after giving low ratings and negative reviews. For example, a user rates Transformers: Age of Extinction with one star and comments “terrible plot,” but still watches Transformers: The Last Knight and The Fate of the Furious months later.

- Focusing solely on rational preference modeling: Mainstream methods [8,9,10] still primarily emphasize users’ rational preferences, treating users as mere preference matchers while neglecting the affective dimension of how users feel. For instance, InteRecAgent [8] only summarizes users’ preferences, and RecMind [9] does not maintain emotional states.

- Overly coarse-grained emotion modeling: Although a few recent studies (e.g., Agent4Rec [11]) have begun to incorporate emotions, they typically rely on simplistic binary or categorical labels such as “satisfied/unsatisfied” or “fatigued/energetic”, ignoring the rich semantics and dynamic evolution of emotions. For instance, “shocking but slightly heavy” versus “mind-bending and exciting”, though both are positive emotions, have subtle differences that are crucial for recommendation decisions.

- Lack of cognitive-level memory separation: Emotional memory differs fundamentally from preference memory, possessing unique characteristics such as semantic richness, temporal sensitivity, and interactive complexity. However, existing systems either lack an emotional memory module altogether (e.g., InteRecAgent, RecMind) or entangle it with preference memory. Although AgentCF [12] introduces separate memories for user and item agents, this separation operates along the user-item dimension rather than the cognitive dimension—it does not distinguish between users’ rational preferences (System 2) and emotional responses (System 1), nor does it detect or leverage conflicts between them.

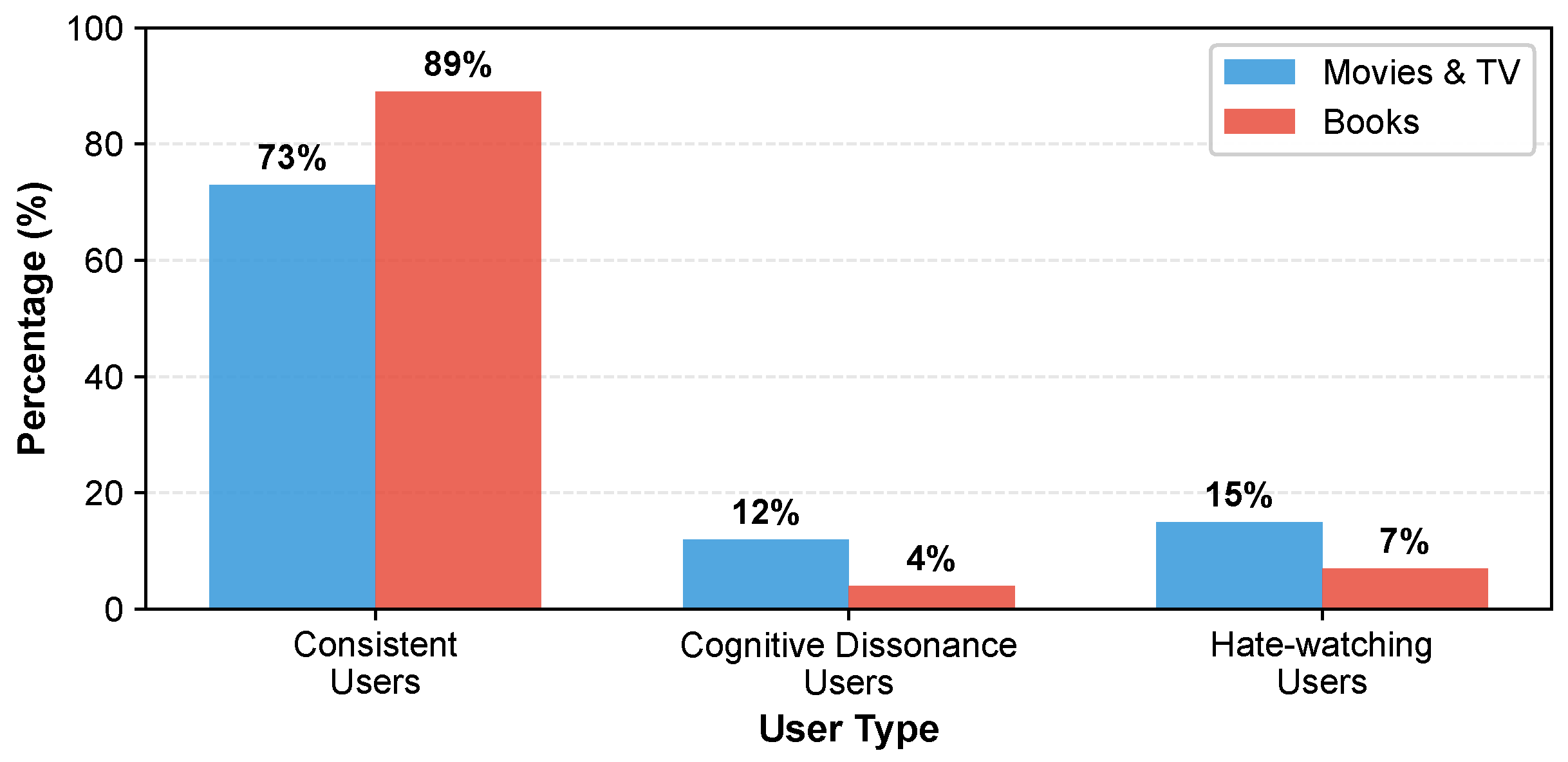

- From a cognitive science perspective, we deeply investigate the emotion–rationality conflict phenomenon in recommendation systems, identifying and quantifying the existence and distribution characteristics of emotion–preference conflicts in large-scale datasets.

- We propose the Emotion-Enhanced Dual-Agent Collaborative Framework, which independently models users’ emotion memory and preference memory through a separate memory architecture and designs a conflict detection mechanism to identify and leverage cognitive conflict signals.

- We develop adaptive reasoning strategies that can automatically select appropriate reasoning approaches based on detected cognitive conflict states, providing personalized recommendations for users with different cognitive states.

- Extensive experiments validate the effectiveness of our method, significantly outperforming existing state-of-the-art baseline methods across multiple datasets and evaluation metrics, particularly excelling in handling high-cognitive-conflict users.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Recommendation Methods

2.2. LLM-Based Recommendation Systems

2.3. Agent-Based Recommendation Systems

2.4. Affective Recommender Systems

3. Methodology

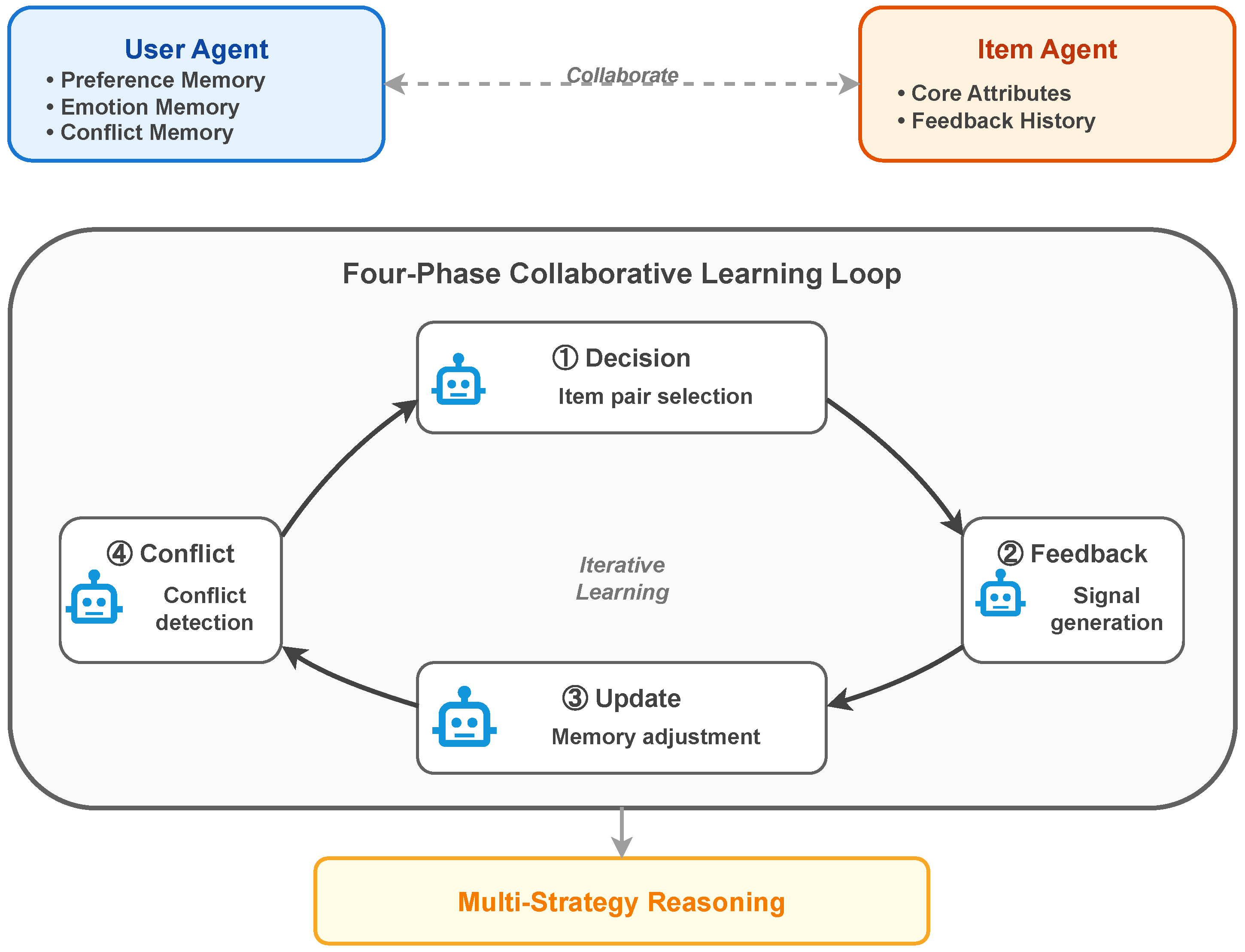

3.1. Problem Reformulation and Framework Overview

3.2. Emotion-Enhanced Dual-Agent Collaborative Framework (EDACF)

3.2.1. Dual-Agent Structure

User Agent

- Preference Memory (System 2): Inductively summarizes the user’s rational preference characteristics, stored in natural language form:where represents the set of items with which user u has historically interacted, denotes the metadata of item j (including structured attributes such as title, category, actors, director, and unstructured text such as plot synopsis), represents user u’s rating, and represents the inductive summarization function based on large language models, which extracts preference patterns from item metadata and user ratings and summarizes them into natural language preference descriptions.In the initial stage (), the system extracts item metadata from the user’s historical interactions and inductively summarizes it to generate initial preference descriptions; in the subsequent collaborative learning process, this memory adopts a conservative update strategy, maintaining the user’s stable interests and tastes through gradual adjustments.

- Emotion Memory (System 1): Captures the user’s dynamic emotional experiences, retaining records of emotional responses from the most recent k interactions. Each record contains item information, category, rating, review, and timestamp:where represents the most recent k interactions of user u before time t, and represent the item name and category respectively, and represent the user’s rating and review text, and represents the interaction timestamp. Unlike the inductive summarization in preference memory, emotion memory retains specific interaction details, especially the rich emotional expressions contained in reviews, thereby supporting fine-grained emotional pattern recognition and temporal behavior analysis.This memory is initially empty () and is dynamically constructed during collaborative learning: after each interaction, new emotional experience records are appended to the sequence, and when the sequence length exceeds k, the earliest record is removed to maintain a fixed window.

- Conflict Memory : Tracks the user’s emotion–preference conflict history, providing conflict pattern basis for reasoning:where represents the conflict detection result at historical time that raised between preference memory and emotion memory,where uses large language models to determine whether there are significant inconsistencies.Since emotion memory retains detailed information such as item names, categories, ratings, and reviews, the detection process can not only determine whether conflicts exist but also identify specific conflict types. Based on the temporal manifestation of conflicts, we distinguish two types of conflict:

- –

- Cognitive Dissonance (Instantaneous Conflict): Occurs within a single interaction when the rating and review sentiment are inconsistent. For example, a user rates a movie 2 but writes “I did enjoy the film…”. This conflict can be detected from a single interaction without historical data.

- –

- Hate-Watching (Sustained Conflict): Occurs over a sequence of interactions when the user repeatedly gives low ratings and negative reviews for items in a certain series or category but continues consuming them. Detection of this conflict requires analyzing both preference and emotion memory over time.

Each conflict detection result contains three key elements: has_conflict , type , and description. Here, has_conflict indicates whether a conflict exists, type specifies the conflict category, and description provides a natural language summary. Conflict memory is initially empty, . During each collaborative learning round, detected conflicts are appended to the history, gradually accumulating the user’s cognitive conflict patterns.

Item Agent

- Core Attributes : Aggregates the item’s metadata, stored in natural language form:where represents the complete metadata of item i, including structured attributes (title, category, actors, director, release year, etc.) and unstructured text (plot synopsis, content description, etc.). represents the aggregation function based on large language models, which integrates this heterogeneous information into a unified natural language representation. This memory remains relatively stable in the learning process.

- Feedback Memory : Summarizes users’ emotional responses to the item, modeling the item’s affective triggering features:where represents the set of users who have interacted with item i by time t, and represent user u’s review and rating for item i, respectively, and represents the summarization function based on large language models, which extracts the item’s affective triggering features from user feedback. This memory is initially empty () and is dynamically constructed during collaborative learning.

3.2.2. Collaborative Learning Mechanism

Phase 1: Cognitive Decision

Phase 2: Feedback Generation

Phase 3: Memory Update

Phase 4: Conflict Detection

3.2.3. Multi-Strategy Reasoning

Basic Reasoning Strategy

Emotion-Enhanced Reasoning Strategy

Conflict-Aware Reasoning Strategy

| Algorithm 1 Conflict-Aware Adaptive Reasoning for Recommendation |

|

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Datasets

4.1.2. User Cognitive Conflict Distribution

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.1.4. Baseline Methods

- BPR-MF [43]: A classic matrix factorization recommendation method. It learns low-dimensional latent representations of users and items by optimizing the Bayesian Personalized Ranking loss function, and uses inner product for rating prediction.

- SASRec [21]: A sequential recommendation model based on self-attention mechanisms. It uses Transformer encoders to capture sequential dependencies in user interaction history, capable of modeling the dynamic evolution of short-term interests and long-term preferences.

- LLMRank [25]: Directly uses large language models as zero-shot rankers. It constructs user interaction history sequences and textual descriptions of candidate items as prompts, leveraging the language understanding capabilities of LLMs to directly perform ranking recommendations.

- Agent4Rec [11]: An LLM-based user simulation recommendation system. It simulates user behavior by constructing user agents with memory and reflection capabilities, including basic emotional state tracking (satisfaction and fatigue), but does not explicitly model emotion–preference conflicts.

- AgentCF [12]: An LLM-based collaborative filtering recommendation method. It implements recommendations through interactive learning between user agents and item agents, where user agents maintain preference memory and item agents maintain feature memory.

4.1.5. Implementation Details

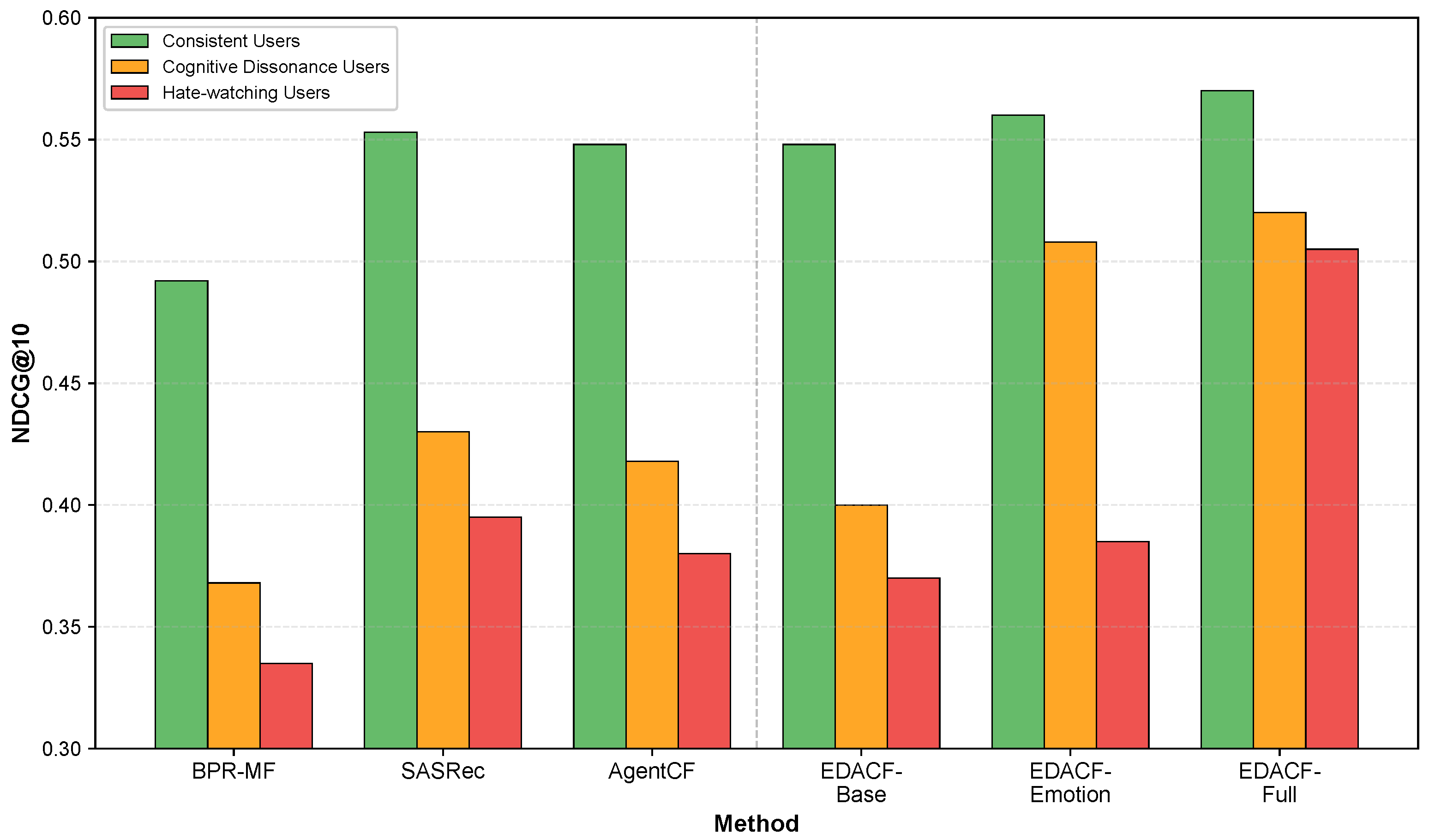

4.2. Overall Performance

4.3. Further Analysis

4.3.1. Ablation Study

4.3.2. User Group Performance Analysis

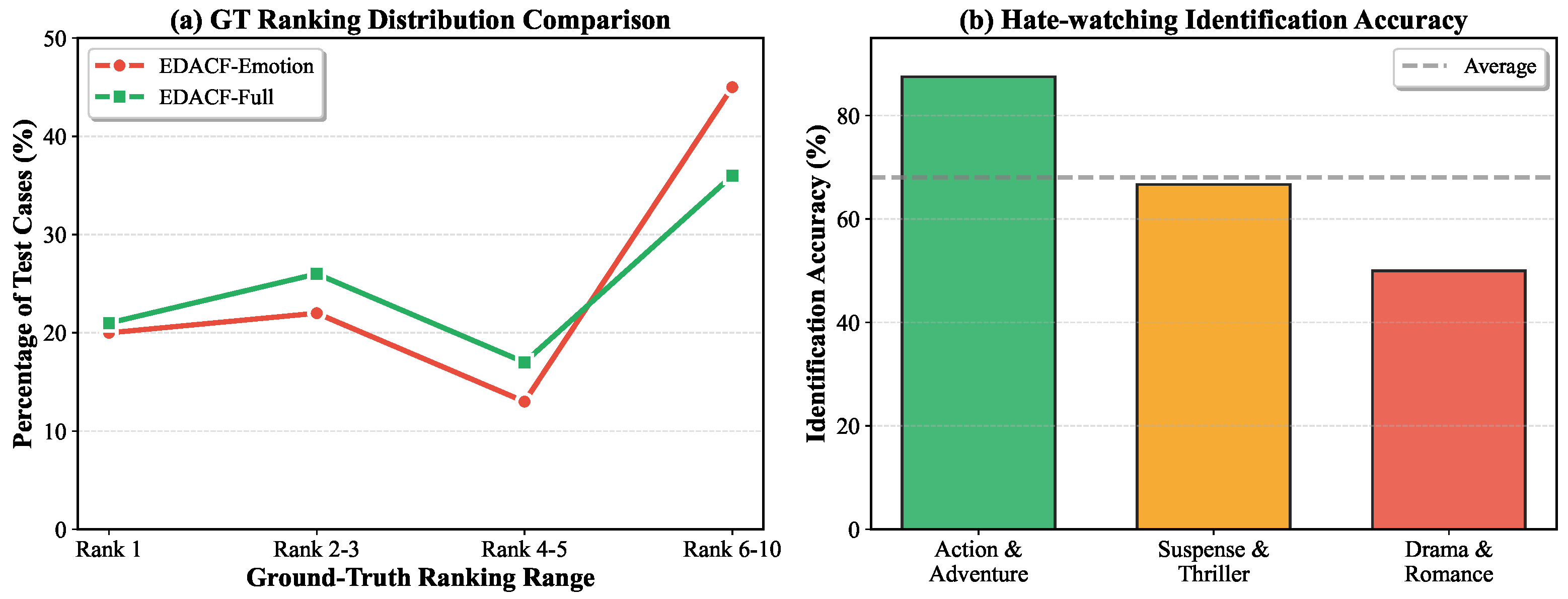

4.3.3. Conflict-Aware Mechanism Analysis

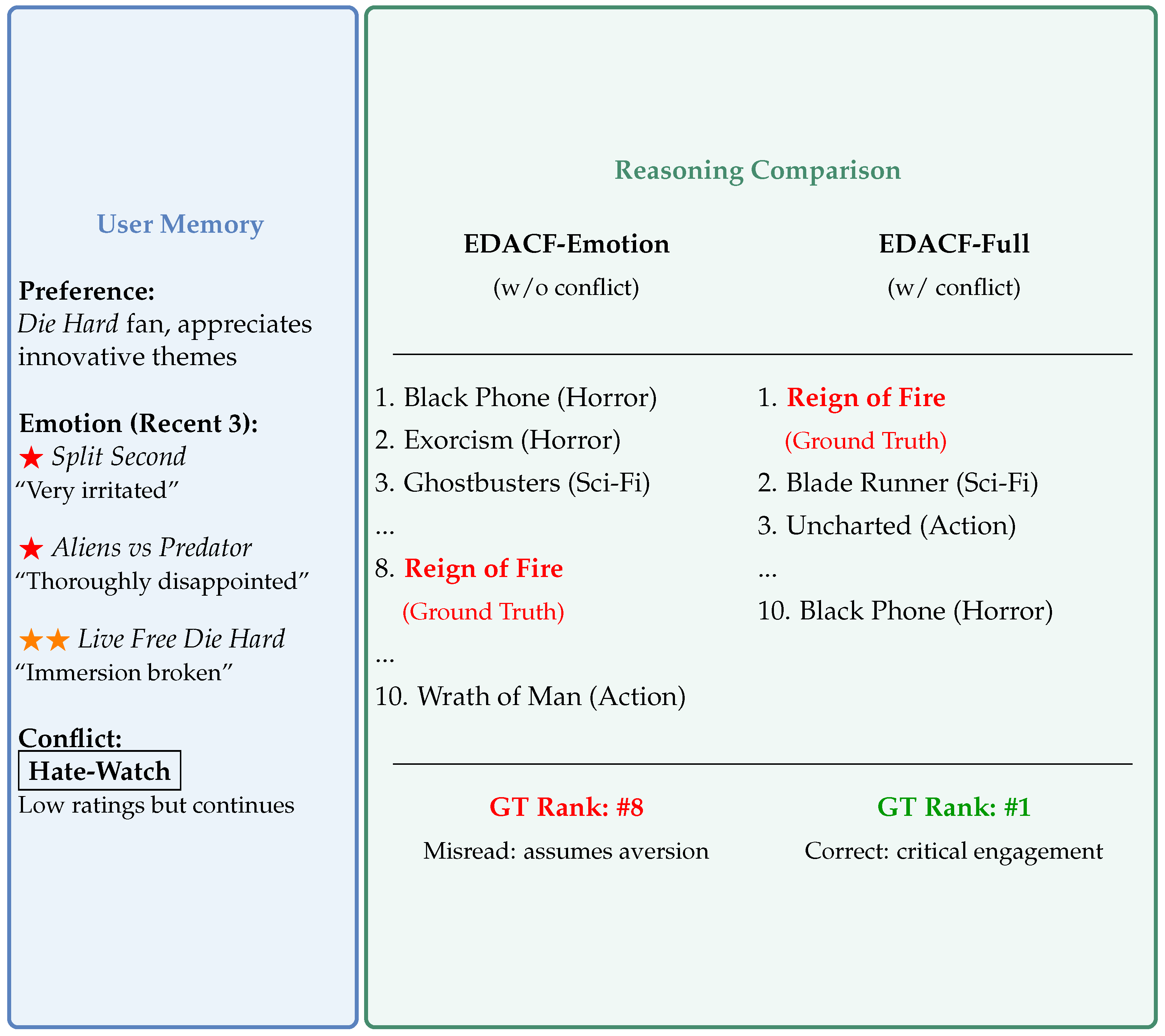

4.3.4. Case Study

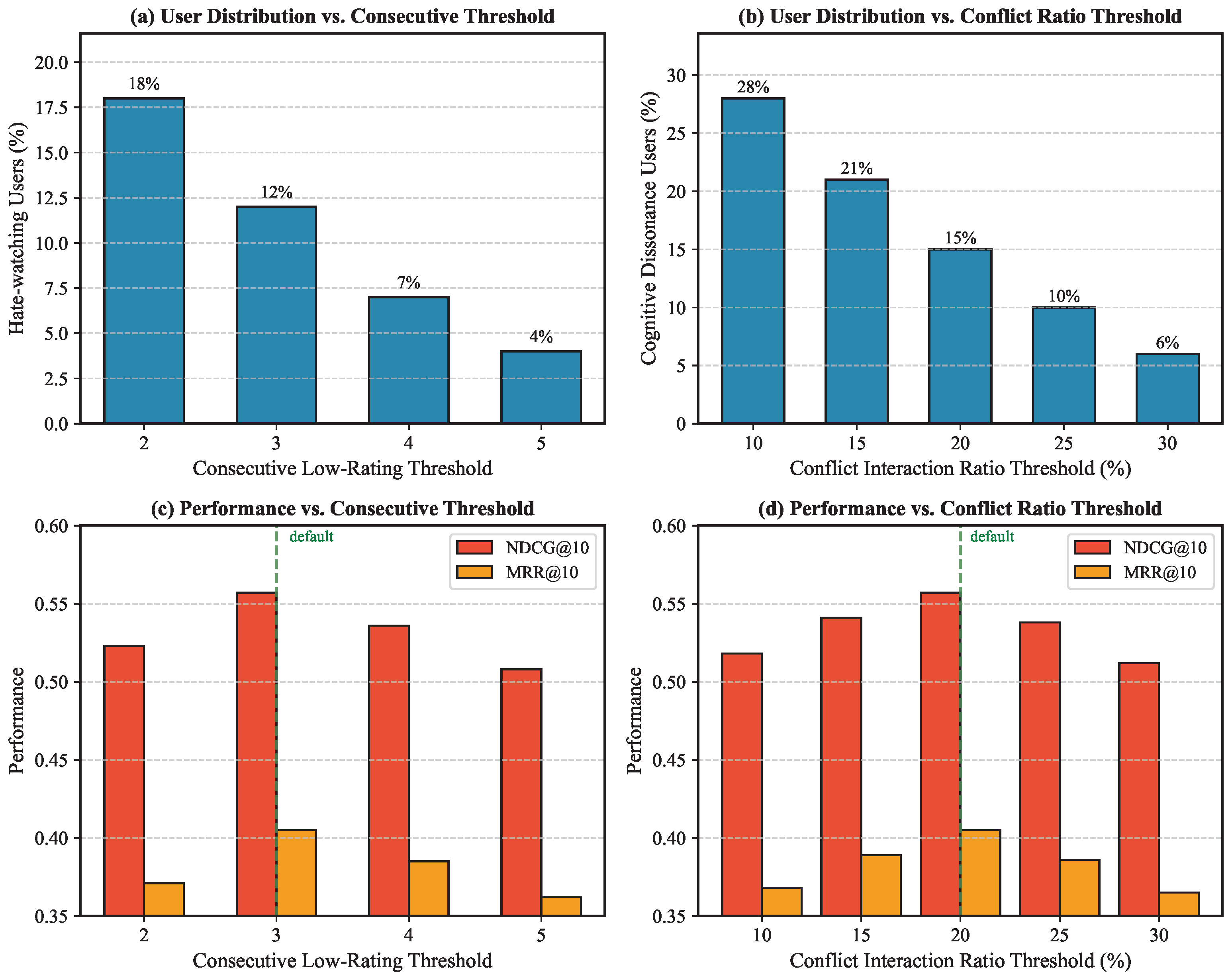

4.3.5. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

4.3.6. Robustness Analysis

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Detailed Analysis of Hate-Watching User Case

Appendix A.1. Case Background

Appendix A.2. Agent Memory

| Memory Type | Content |

|---|---|

| Preference Memory | I am a die-hard fan of the original Die Hard, favoring the solid action films of the 1980s. I am very critical of the production quality of action/sci-fi films—I cannot tolerate clichéd dialogue, absurd plot holes, and perfunctory production. I particularly appreciate films that dare to explore innovative and unconventional themes. |

| Emotion Memory (chronological order) | 1. Stargate (Sci-Fi, 2.0, 2021-12-09) “Watching Stargate felt very boring, with no sense of tension, like wandering aimlessly in a garden. The story is filled with clichéd tropes everywhere, I really couldn’t stand it and gave up halfway through.” |

| 2. Cosmoball (Sci-Fi, 5.0, 2021-12-13) “The dystopian Earth concept in Cosmoball felt quite interesting to me. Although the execution wasn’t perfect, I was watching it as a B-movie and didn’t have high expectations, so I actually found it worth watching.” | |

| 3. Split Second (Action, 1.0, 2021-12-22) “Split Second made me feel very irritated—clichéd dialogue, terrible acting, absurd character behavior, crude sets, ridiculous costumes, and that annoying heartbeat sound throughout the film. I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone.” | |

| 4. Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem (Action, 1.0, 2022-01-03) “The concept of Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem was good, but the execution was too poor. I watched the entire film with hope, expecting it to improve, but was thoroughly disappointed. It’s just lazy filmmaking.” | |

| 5. Live Free or Die Hard (Action, 2.0, 2022-02-03) “Don’t get me wrong, I’m a die-hard fan of the original Die Hard, but the action sequences in this one are unbelievably exaggerated, completely breaking my immersion. The plot holes are also significant. Although it’s better than the third installment, it really doesn’t qualify as a good action film.” | |

| Conflict Memory | This user exhibits a typical "hate-watching" pattern toward the action film genre. Despite consistently giving low ratings (1–2 stars) to action films and writing detailed critical reviews (pointing out production flaws, plot holes, clichés, etc.), they continue to watch and complete these films. As a devoted fan of the Die Hard franchise and classic 1980s action films, this user maintains deep engagement with the action genre through critical participation. The negative evaluations reflect high standards and deep engagement rather than genuine lack of interest. |

Appendix A.3. Reasoning Phase Comparison

| EDACF-Emotion (Without Conflict Memory) | EDACF-Full (With Conflict Memory) |

|---|---|

|

|

References

- Yuan, Z.; Yuan, F.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Fu, J.; Yang, F.; Pan, Y.; Ni, Y. Where to go next for recommender systems? id-vs. modality-based recommender models revisited. In Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–27 July 2023; pp. 2639–2649. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, S.; Yin, D.; Li, Q.; Tang, J.; Guo, R. Embedding in recommender systems: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.18608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; Bunescu, R. A survey of affective recommender systems: Modeling attitudes, emotions, and moods for personalization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.20289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Ko, H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.D. Modeling of recommendation system based on emotional information and collaborative filtering. Sensors 2021, 21, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. The affect heuristic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 177, 1333–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polignano, M.; Narducci, F.; de Gemmis, M.; Semeraro, G. Towards emotion-aware recommender systems: An affective coherence model based on emotion-driven behaviors. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 170, 114382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lian, J.; Lei, Y.; Yao, J.; Lian, D.; Xie, X. Recommender ai agent: Integrating large language models for interactive recommendations. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 43, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Cho, E.; Fan, X.; Lu, Y.; Huang, X.; Yang, Y. Recmind: Large language model powered agent for recommendation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024, Mexico City, Mexico, 16–21 June 2024; pp. 4351–4364. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Ma, W.; Zhang, M. Macrec: A multi-agent collaboration framework for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 2760–2764. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.; Chen, Y.; Sheng, L.; Wang, X.; Chua, T.S. On generative agents in recommendation. In Proceedings of the 47th international ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 1807–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Hou, Y.; Xie, R.; Sun, W.; McAuley, J.; Zhao, W.X.; Lin, L.; Wen, J.R. Agentcf: Collaborative learning with autonomous language agents for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, Singapore, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 3679–3689. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, B.; Karypis, G.; Konstan, J.; Riedl, J. Item-based collaborative filtering recommendation algorithms. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on World Wide Web, Hong Kong, China, 1–5 May 2001; pp. 285–295. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Y. Factorization meets the neighborhood: A multifaceted collaborative filtering model. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 August 2008; pp. 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Y.; Bell, R.; Volinsky, C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 2009, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.T.; Koc, L.; Harmsen, J.; Shaked, T.; Chandra, T.; Aradhye, H.; Anderson, G.; Corrado, G.; Chai, W.; Ispir, M.; et al. Wide & deep learning for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Deep Learning for Recommender Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 15 September 2016; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Nie, L.; Hu, X.; Chua, T.S. Neural collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Tang, R.; Ye, Y.; Li, Z.; He, X. DeepFM: A factorization-machine based neural network for CTR prediction. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.04247. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; He, X.; Wang, M.; Feng, F.; Chua, T.S. Neural graph collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 42nd international ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Paris, France, 21–25 July 2019; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Deng, K.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Lightgcn: Simplifying and powering graph convolution network for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 25–30 July 2020; pp. 639–648. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W.C.; McAuley, J. Self-attentive sequential recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Singapore, 17–20 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Feng, F.; Ng, S.K.; Chua, T.S. Bridging items and language: A transition paradigm for large language model-based recommendation. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 1816–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y.; Liu, W.; Lin, J.; Cai, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, B.; Tang, R.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y. Towards open-world recommendation with knowledge augmentation from large language models. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Bari, Italy, 14–18 October 2024; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Xie, Z.; Jha, R.; Steck, H.; Liang, D.; Feng, Y.; Majumder, B.P.; Kallus, N.; McAuley, J. Large language models as zero-shot conversational recommenders. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Birmingham, UK, 21–25 October 2023; pp. 720–730. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Z.; Lu, H.; Xie, R.; McAuley, J.; Zhao, W.X. Large language models are zero-shot rankers for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Retrieval, Glasgow, UK, 24–28 March 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 364–381. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, F.; He, X. Tallrec: An effective and efficient tuning framework to align large language model with recommendation. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Singapore, 18–22 September 2023; pp. 1007–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, F.; Zhang, J.; Bao, K.; Wang, Q.; He, X. Collm: Integrating collaborative embeddings into large language models for recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Gao, M.; Fan, C.; Yuan, S.; Shi, W.; He, X. Process-supervised llm recommenders via flow-guided tuning. In Proceedings of the 48th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Padua, Italy, 13–18 July 2025; pp. 1934–1943. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Chen, R.; Yuan, S.; Huang, K.; Yu, Y.; He, X. Sprec: Self-play to debias llm-based recommendation. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 5075–5084. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; Song, R.; Zhao, W.X.; Wen, J.R. Recagent: A novel simulation paradigm for recommender systems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.02552. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; Sun, H.; Song, R.; et al. User behavior simulation with large language model-based agents. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 43, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gu, S.; Li, D.; Zhang, G.; Han, M.; Gu, H.; Zhang, P.; Lu, T.; Shang, L.; Gu, N. AgentCF++: Memory-enhanced LLM-based Agents for Popularity-aware Cross-domain Recommendations. In Proceedings of the 48th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Padua, Italy, 13–18 July 2025; pp. 2566–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gu, H.; Zhang, P.; Lu, T.; Li, D.; Gu, N. Rah! recsys–assistant–human: A human-centered recommendation framework with llm agents. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 6759–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, J.; Bao, K.; Gao, C.; Wang, Q.; Feng, F.; He, X. Agentic feedback loop modeling improves recommendation and user simulation. In Proceedings of the 48th International ACM SIGIR conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Padua, Italy, 13–18 July 2025; pp. 2235–2244. [Google Scholar]

- Pepitone, A. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, D.; Park, C.; Yang, M.C.; Song, I.; Lee, J.T.; Yu, H. Review sentiment-guided scalable deep recommender system. In Proceedings of the 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 8–12 July 2018; pp. 965–968. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Wu, W.; Guo, W.; Hu, W.; Chen, J.; Zheng, W.; He, L. SENGR: Sentiment-enhanced neural graph recommender. Inf. Sci. 2022, 589, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Qian, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Chen, E. Sifn: A sentiment-aware interactive fusion network for review-based item recommendation. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 3627–3631. [Google Scholar]

- Revathy, V.; Pillai, A.S.; Daneshfar, F. LyEmoBERT: Classification of lyrics’ emotion and recommendation using a pre-trained model. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 218, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darraz, N.; Karabila, I.; El-Ansari, A.; Alami, N.; El Mallahi, M. Integrated sentiment analysis with BERT for enhanced hybrid recommendation systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 261, 125533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, X. Affective video recommender systems: A survey. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 984404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Li, J.; He, Z.; Yan, A.; Chen, X.; McAuley, J. Bridging Language and Items for Retrieval and Recommendation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.03952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendle, S.; Freudenthaler, C.; Gantner, Z.; Schmidt-Thieme, L. BPR: Bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1205.2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | #Users | #Items | #Int. | Sparsity | Avg. Int. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Movies & TV (full) | 2865 | 1876 | 22,902 | 99.57% | 7.99 |

| -Sampled | 100 | 712 | 848 | 98.81% | 8.48 |

| Books (full) | 2622 | 2161 | 23,134 | 99.59% | 8.82 |

| -Sampled | 100 | 689 | 804 | 98.84% | 8.04 |

| Amazon Movies & TV | Amazon Books | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | N@5 | N@10 | MRR@10 | N@5 | N@10 | MRR@10 |

| Traditional Recommendation Methods | ||||||

| BPR-MF | 0.403 | 0.458 | 0.305 | 0.388 | 0.441 | 0.298 |

| SASRec | 0.453 | 0.515 | 0.368 | 0.438 | 0.498 | 0.355 |

| LLM-based Recommendation Methods | ||||||

| LLMRank | 0.412 | 0.468 | 0.325 | 0.398 | 0.452 | 0.312 |

| Agent4Rec | 0.433 | 0.492 | 0.342 | 0.418 | 0.475 | 0.330 |

| AgentCF | 0.446 | 0.507 | 0.358 | 0.431 | 0.489 | 0.346 |

| Our Methods | ||||||

| EDACF-Base | 0.443 | 0.503 | 0.354 | 0.427 | 0.485 | 0.342 |

| EDACF-Emotion | 0.468 | 0.532 | 0.381 | 0.453 | 0.514 | 0.367 |

| EDACF-Full | 0.490 * | 0.557 * | 0.405 * | 0.474 * | 0.538 * | 0.391 * |

| Variant | NDCG@5 | NDCG@10 | MRR@10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDACF-Full | 0.490 | 0.557 | 0.405 |

| w/o Emotion memory | 0.426 | 0.484 | 0.344 |

| w/o Conflict memory | 0.468 | 0.532 | 0.381 |

| w/o Item agent | 0.438 | 0.498 | 0.358 |

| w/o Adaptive reasoning | 0.475 | 0.540 | 0.388 |

| LLM Model | NDCG@10 | MRR@10 |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o-mini | 0.557 | 0.405 |

| GPT-4o | 0.573 (+2.9%) | 0.417 (+3.0%) |

| DeepSeek-V3 | 0.554 (−0.5%) | 0.402 (−0.7%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Zeng, D. Emotion-Enhanced Dual-Agent Recommendation: Understanding and Leveraging Cognitive Conflicts for Better Personalization. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010253

Yang Y, Wang Z, Li L, Zeng D. Emotion-Enhanced Dual-Agent Recommendation: Understanding and Leveraging Cognitive Conflicts for Better Personalization. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010253

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yulin, Zikang Wang, Linjing Li, and Daniel Zeng. 2026. "Emotion-Enhanced Dual-Agent Recommendation: Understanding and Leveraging Cognitive Conflicts for Better Personalization" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010253

APA StyleYang, Y., Wang, Z., Li, L., & Zeng, D. (2026). Emotion-Enhanced Dual-Agent Recommendation: Understanding and Leveraging Cognitive Conflicts for Better Personalization. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010253