Featured Application

CSA cement enhances concrete durability by reducing water absorption, sorptivity, and freeze–thaw damage, making it suitable for demanding infrastructure and precast applications.

Abstract

This study presents a comprehensive experimental evaluation of high-performance concretes incorporating calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) cement as a partial replacement for ordinary Portland cement (OPC). Five CSA replacement levels (0, 15, 30, 45, and 60%) and two water-to-cement ratios (0.40 and 0.45) were examined to assess their effects on mechanical performance and key durability parameters. The experimental program simultaneously investigated compressive strength, tensile splitting strength, water absorption, sorptivity, gas permeability, and freeze–thaw resistance, offering an integrated assessment rarely addressed in previous studies, which typically focus on selected parameters or narrower replacement ranges. The results show that CSA addition enhances microstructural densification, substantially reducing sorptivity and gas permeability and markedly improving freeze–thaw performance even without air entrainment. High CSA contents (45–60%) yielded superior transport-related durability while maintaining competitive 28-day strengths, especially for w/c = 0.40. These findings clarify the interplay between CSA content, transport properties, and frost resistance, highlighting CSA–OPC hybrid binders as a durable and sustainable solution for high-performance concrete applications.

1. Introduction

Concrete durability and performance remain critical challenges for modern infrastructure, driving interest in alternative binders that can enhance mechanical strength while improving long-term resistance to degradation. Calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) cement has gained significant attention in this context. Developed in the mid-20th century as a rapid-hardening cement, CSA differs fundamentally from ordinary Portland cement (OPC) because of its mineralogical composition. Its primary clinker phase, ye’elimite (C4A3Ŝ), reacts rapidly with gypsum and water to form ettringite as the dominant hydration product. This reaction generates early heat release and rapid strength development [1], with CSA concretes often reaching more than 20 MPa within hours and exceeding 50 MPa at 28 days [1]. Moreover, CSA hydration produces minimal autogenous shrinkage and slight expansion, reducing early-age cracking and promoting dimensional stability [2]. These characteristics make CSA suitable for rapid-repair applications, precast production, and high-performance concretes requiring accelerated construction schedules [3]. CSA cement also offers notable sustainability benefits. Its clinker is produced at a lower sintering temperature (~1250 °C compared with ~1450 °C for OPC) and can incorporate industrial by-products such as gypsum and fly ash, reducing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions [2,4]. Life-cycle assessments consistently show that CSA clinker has a significantly lower environmental footprint, particularly in terms of CO2 emissions per ton of cement [5].

Among the key durability indicators of CSA-modified concretes, water absorption and sorptivity are particularly important because they govern fluid ingress and long-term resistance to aggressive environments. Compared with OPC systems, CSA-blended concretes typically show reduced water absorption due to pore-structure refinement and the formation of stable ettringite that blocks capillary porosity [4,6]. Sorptivity, which quantifies capillary suction, is likewise reduced in CSA-modified mixtures, especially when appropriate water–cement ratios are used [7]. Ke et al. [4] demonstrated that CSA clinker decreases pore connectivity, limiting capillary suction and ion transport. Tan et al. [5] similarly found that moderate CSA replacement provides low absorption and sorptivity while maintaining adequate mechanical performance. Marine-exposure studies report 20–35% lower water absorption and slower sorptivity-driven chloride ingress compared with OPC concretes [8]. Ioannou et al. [6] observed sorptivity reductions of 30–45% in ternary CSA–anhydrite–fly ash mixtures, while Acartürk et al. [7] showed improved transport resistance in CSA binders containing supplementary cementitious materials.

Recent advances in mixture design underscore the importance of optimizing CSA–OPC blends to achieve both high mechanical performance and durability. Studies on green CSA-supported OPC cements [9] show that such systems reduce energy demand and CO2 emissions while maintaining high early- and late-age strength and dense microstructures. Time-domain characterization of CSA-modified ultra-high-performance concrete likewise demonstrates substantial pore refinement and matrix densification resulting from partial CSA substitution [10] Additionally, innovative CO2-based foaming methods applied to CSA systems [11] have been shown to optimize pore structure and improve transport properties and microstructural homogeneity.

Numerous studies highlight the strong freeze–thaw resistance of CSA concretes when properly proportioned, often outperforming OPC systems [1,2,8]. Qadri [1] showed that CSA–OPC concretes with internal curing survived more than 300 freeze–thaw cycles (compared with ~160 for OPC), while de Bruyn et al. [2] attributed the superior frost resistance to finer, unimodal pore distributions. CSA systems also exhibit enhanced durability under wet–dry marine exposure, showing lower porosity growth and higher residual strength than OPC concretes [8]. These behaviours are linked to reduced fluid ingress, which limits internal saturation and mitigates frost damage.

In structural applications, CSA is commonly blended with OPC to form hybrid binders. Partial replacement (15–30%) generally balances CSA’s rapid strength development and shrinkage compensation with the long-term performance of OPC [12]. As reported in the literature [13,14,15,16], incomplete ye’elimite hydration under limited water supply may delay ettringite formation and slow early matrix densification, leading to a temporary loss in early-age strength at moderate CSA dosages. Excessive CSA replacement (≥45–60%) can compromise mechanical stability or increase permeability in some systems [5] if mixture design does not ensure adequate water availability or hydration control. However, when these conditions are optimized, the literature increasingly shows that higher CSA contents (between 40% and 60%) yield the highest overall performance. For example, Huang et al. [13] reported that concretes containing 50% CSA achieved ≈85 MPa compressive strength at 28 days, outperforming lower CSA dosages. Nie et al. [15] found that 45–55% CSA produced the most refined pore structures, with 40–60% reductions in permeability compared with OPC. In durability studies, de Bruyn et al. [2] noted that concretes with ≈40% CSA retained over 95% residual strength after 300 freeze–thaw cycles, while Qadri et al. [1] showed that 45% CSA provided the best frost durability among CSA–OPC mixtures, again surviving more than 300 cycles without deterioration. Taken together, these studies indicate that CSA contents in the range of 40–60% consistently deliver the highest mechanical strength, the lowest permeability, and the greatest freeze–thaw resistance reported in the literature.

The water-to-cement ratio is equally important. CSA hydration requires sufficient water availability (theoretical w/c > 0.6 for complete ye’elimite reaction), whereas excessive water increases porosity [4]. Thus, durability and mechanical performance must be optimized by simultaneously adjusting the CSA content and w/c ratio, but comprehensive studies addressing both parameters remain limited.

To address this gap, the present study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the mechanical and durability properties of CSA–OPC concretes. Five CSA replacement levels (0–60%) were combined with two water–cement ratios (0.40 and 0.45). The study investigated compressive strength (7 and 28 days), tensile splitting strength (28 days), freeze–thaw resistance, gas permeability (Torrent method), water absorption, and capillary sorptivity. By systematically assessing the influence of the CSA dosage and w/c ratio, this research establishes practical guidelines for the design of durable, high-performance CSA-modified concretes and contributes to a deeper understanding of CSA behaviour in hybrid binder systems.

2. Materials and Methods

Concrete mixtures were prepared using siliceous sand (0–2 mm), recycled concrete aggregate (RCA, 2–4 mm), and granite aggregates (4–8 mm and 8–16 mm), incorporated in constant volumetric proportions of 35%, 8%, 17%, and 40%, respectively. Two binders were used: CEM I 42.5N and CSA cement. Portland cement was replaced with CSA at 15%, 30%, 45%, and 60% by mass. Two water-to-cement ratios (w/c = 0.40 and 0.45) were applied. Mixture designations (e.g., C45/40) indicate the percentage of OPC replaced by CSA and the corresponding w/c ratio.

The selection of raw materials and mixture parameters followed established practices for CSA–OPC hybrid systems reported in the recent literature. CEM I 42.5N (density 3.10 g/cm3) and CSA cement (density 3.15 g/cm3) were selected because they represent commonly used binders in studies evaluating the mechanical and durability performance of ye’elimite-rich systems. Although the particle size distribution of the CSA and ordinary Portland cement used in this study was not experimentally measured, according to literature data [17], CSA cements from the same manufacturer as those used here typically exhibit median particle sizes in the range of d50 = 4.7–7.3 μm. The CEM I 42.5N cement used in this study was obtained from a different manufacturer; nevertheless, typical literature values for CEM I 42.5R (d50 ≈ 10–11 μm) are comparable across manufacturers [18,19]. The CSA replacement levels (15–60%) fall within ranges typically investigated to capture both early strength development and durability-related effects. The adopted water-to-cement ratios (0.40 and 0.45) comply with the recommendations for high-performance concrete specified in PN-B-06265 [20] and are consistent with CSA-oriented durability studies. Aggregate grading and volumetric proportions correspond to standard practice for structural concrete.

Specimen geometries were selected according to relevant standards: 100 mm cubes for compressive strength and freeze–thaw testing (PN-EN 12390-3 [21], PN-EN 12390-6 [22], PN-B-06250 [23]) and 150 mm cubes for gas permeability testing, as required by the Torrent method. In terms of the durability tests, water absorption, sorptivity, and air permeability are widely recognized indicators of pore structure and transport performance in CSA–OPC research, ensuring comparability with existing studies and adherence to established testing methodologies. The chemical composition of the CEM I and CSA cement is presented in Table 1, and detailed mix proportions are given in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.

X-ray fluorescence chemical composition and loss on ignition of Portland cement and CSA cement (% by mass).

Table 2.

Composition of concrete mixes with w/c = 0.40 (kg/m3).

Table 3.

Composition of the concrete mix with w/c = 0.45, kg/m3.

Concrete specimens were cast and stored in moulds for 48 h under moist conditions and then cured in water at 20 ± 2 °C until testing. Mechanical testing included compressive strength according to PN-EN 12390-3 [21] on 100 mm cubes after 7 and 28 days, and tensile splitting strength was tested after 28 days following PN-EN 12390-6 [22].

Freeze–thaw resistance was assessed according to PN-B-06250 [23] using fully saturated 100 mm cubes. Specimens were subjected to 120 cycles between –18 ± 2 °C and +20 ± 2 °C. After cycling, mass loss, visible surface damage, and residual compressive strength were evaluated in accordance with standard acceptance criteria.

Durability tests included water absorption, sorptivity, and air permeability. Water absorption was determined using halves of 100 mm cubes previously tested in splitting tension. Specimens were immersed for 5 days and then dried at 110 °C for 14 days, and water absorption was calculated from the change in mass. Sorptivity was measured on the same halves using a simplified mass-gain approach, with the water contact depth limited to 3–5 mm. Mass was recorded for up to 6 h to determine initial sorptivity, using a procedure similar to that described in [24].

Gas permeability was measured using the Torrent method [25], which determines the permeability coefficient kT based on pressure equalization under low vacuum [26]. Tests were performed on 150 mm cubes, and each kT value represents the average of four measurements per specimen.

For compressive strength, three 100 mm cubes were tested at 7 days and six cubes at 28 days. Tensile splitting strength was determined on six specimens. Freeze–thaw resistance was evaluated using five fully saturated 100 mm cubes per mixture, with four additional cubes serving as reference specimens. Water absorption and sorptivity were measured on halves of the six cubes previously tested in splitting tension. Gas permeability was determined on two 150 mm cubes, with four measurement points recorded per specimen.

3. Results

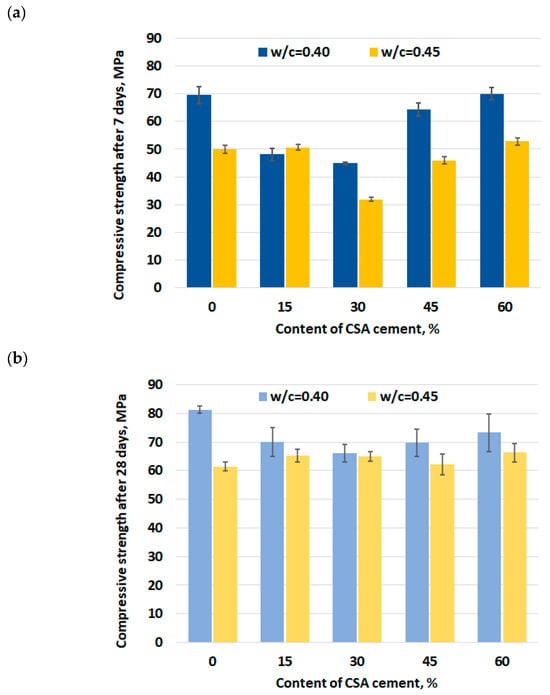

The compressive strength results at 7 and 28 days for mixtures with varying CSA cement contents and water-to-cement ratios are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2. After 7 days, the reference mixture with w/c = 0.40 (C0/40) achieved the highest strength of 69.5 MPa, while the corresponding mixture with w/c = 0.45 reached 50.0 MPa. Partial replacement of Portland cement with CSA cement reduced early-age strength, particularly at 15–30% CSA, where compressive strength decreased to 48.2 MPa and 44.9 MPa for w/c = 0.40 and to 50.7 MPa and 31.9 MPa for w/c = 0.45, respectively. However, at higher CSA replacement levels (45–60%), a clear recovery in early strength was observed. For w/c = 0.40, compressive strength increased to 64.3 MPa at 45% CSA and further to 70.0 MPa at 60% CSA, surpassing the reference mixture. For w/c = 0.45, strengths remained below the control, although a moderate improvement was evident at 60% CSA (52.8 MPa).

Figure 1.

Compressive strength results after (a) 7 days and (b) 28 days of curing for mixtures with varying CSA cement contents and water-to-cement ratios.

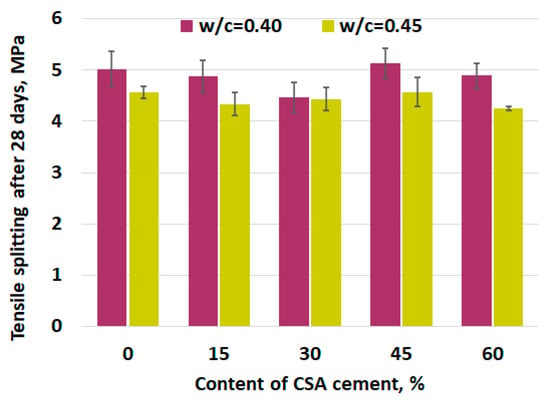

Figure 2.

Tensile splitting strength results after 28 days of curing for mixtures with varying CSA cement contents and water-to-cement ratios.

At 28 days, the reference mixtures again exhibited the highest compressive strengths—81.3 MPa for w/c = 0.40 and 61.5 MPa for w/c = 0.45. CSA replacement generally led to reduced 28-day strength compared with the control; however, the reductions were less pronounced than at early age. For w/c = 0.40, strengths ranged from 66.2 to 73.3 MPa across the 15–60% CSA mixtures, with the highest value at 60% CSA. For w/c = 0.45, the CSA-modified mixtures reached 62.1–66.3 MPa, in several cases slightly exceeding the reference value.

The flexural strength results after 28 days are presented in Figure 2. The tensile splitting strength of the reference concretes was 5.02 MPa for w/c = 0.40 and 4.57 MPa for w/c = 0.45. The incorporation of CSA cement resulted in only minor variations in strength. For mixtures with w/c = 0.40, tensile splitting strength ranged from 4.47 to 5.13 MPa, with the highest value observed at 45% CSA. For w/c = 0.45, values varied between 4.24 and 4.57 MPa, with the lowest strength recorded at 60% CSA. The influence of CSA replacement on tensile splitting strength was limited, and no consistent trend was evident across the tested mixtures.

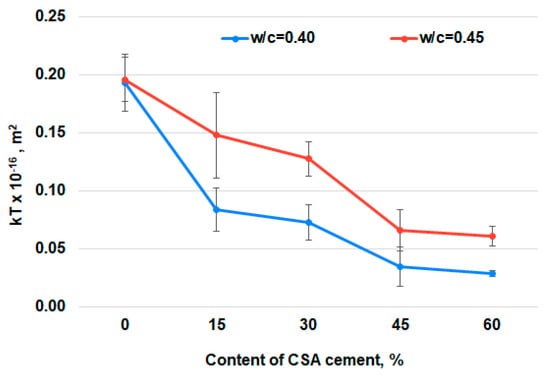

The results of the gas permeability test (Figure 3) show a substantial reduction in kT values with increasing CSA replacement. For w/c = 0.40, kT decreased from 0.193 × 10−16 m2 (reference) to 0.029 × 10−16 m2 at 60% CSA. A similar trend was observed for w/c = 0.45, where kT dropped from 0.196 × 10−16 m2 to 0.061 × 10−16 m2. The most pronounced reduction occurred already at 15% CSA, with further replacement producing gradual additional improvements. The incorporation of CSA clearly enhanced microstructural densification, resulting in markedly lower permeability for both water-to-cement ratios.

Figure 3.

Gas permeability coefficient kT as a function of CSA cement content and water-to-cement ratio, measured using the Torrent method.

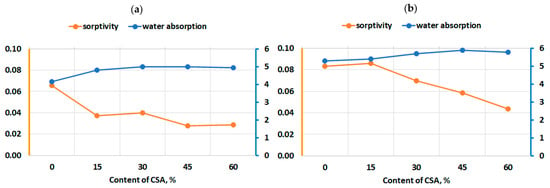

As shown in Figure 4, increasing the CSA cement content led to a clear reduction in sorptivity for both water-to-cement ratios. The effect was more pronounced at w/c = 0.40, where sorptivity decreased by more than 50% at higher CSA replacement levels. In contrast, total water absorption remained relatively stable, exhibiting only minor variations regardless of CSA content. This suggests that CSA cement primarily influences the rate of capillary suction rather than the overall amount of water absorbed.

Figure 4.

Water absorption and sorptivity as a function of CSA cement content for (a) w/c = 0.40 and (b) w/c = 0.45.

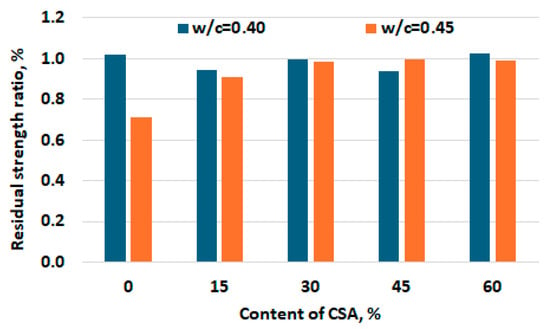

The results of the freeze–thaw resistance tests are presented in Figure 5, which shows the residual compressive strength ratios of concretes containing various amounts of CSA cement after exposure to cyclic freezing and thawing. For mixtures with a lower water-to-cement ratio (w/c = 0.40), the residual strength ratio ranged from 94% to 102%, indicating negligible deterioration after freeze–thaw cycling. In some cases, a slight increase in compressive strength was observed, which can be attributed to continued CSA hydration and microstructural densification during testing. In contrast, mixtures with w/c = 0.45 exhibited greater variability. The reference mixture without CSA showed a pronounced reduction in strength, with a residual strength ratio of approximately 70%, indicating significant frost damage. However, the incorporation of CSA cement markedly improved frost resistance: even at 15% CSA, the residual strength ratio increased to about 90%, and at 30–60% CSA, the values approached 100%, demonstrating excellent resistance to freeze–thaw deterioration.

Figure 5.

Residual compressive strength ratio after freeze–thaw cycling as a function of CSA cement content and water-to-cement ratio.

4. Discussion

The results confirm that the incorporation of CSA cement substantially influences both the mechanical and durability performance of concrete. The variation in compressive strength observed at low (15–30%) and high (45–60%) CSA replacement levels can be explained by the underlying hydration mechanisms of hybrid CSA–OPC binders [13,14]. At early ages, mixtures containing 15–30% CSA exhibited reduced compressive strength compared with the reference concretes. This reduction can be attributed to competitive hydration between OPC and CSA phases, which simultaneously demand available water. Studies [3,15,16] show that limited water leads to incomplete ye’elimite hydration, delayed ettringite formation and early matrix densification, and temporarily reduced early strength at moderate CSA contents.

In contrast, mixtures with higher CSA contents (≥45%) showed a recovery of strength and, in some cases, even strength enhancement, particularly for concretes with w/c = 0.40 [9,15]. This behaviour is consistent with the rapid and extensive formation of ettringite, which promotes early densification of the cementitious matrix and refinement of capillary porosity. The higher volume fraction of CSA clinker accelerates hydration reactions and can offset the reduced later-age contribution of OPC. This effect is most pronounced at lower water-to-cement ratios, where water availability is sufficient to support full ye’elimite hydration and the development of a compact, well-densified microstructure. These mechanisms explain the strength gains observed at higher CSA replacement levels and help reconcile the present findings with studies reporting mechanical instability at high CSA dosages: such reductions typically occur when water availability is inadequate or when mixture design is not properly optimized.

To align with previous research, it must be emphasized that the adverse effects reported for high CSA replacement levels (≥45–60%) commonly arise in mixtures with higher w/c ratios, insufficient water for complete ye’elimite hydration, or suboptimal mixture design. Under such circumstances, incomplete hydration and increased porosity may indeed reduce mechanical stability and increase permeability, as noted in [5]. In the present study, however, the high-CSA mixtures were designed with low w/c ratios, appropriate admixture dosages, and an optimized aggregate structure. These conditions promoted extensive ettringite formation and early microstructural densification. As a result, the mixtures containing 45–60% CSA, particularly those with w/c = 0.40, did not exhibit the deterioration mechanisms described in earlier studies but instead demonstrated enhanced strength, reduced permeability, and excellent freeze–thaw resistance.

Another factor contributing to the favourable performance of the high-CSA mixtures was the use of citric acid as a set retarder, dosed proportionally to the CSA content (0.25% of CSA mass). Citric acid is known to delay the hydration of both OPC and CSA phases by slowing aluminate dissolution and moderating the rate of ettringite formation [16,27]. This controlled retardation reduces the rapid early heat evolution typically associated with CSA hydration [28]. As the CSA content increased, the corresponding increase in retarder dosage likely prolonged hydration, reduced thermal gradients, and lowered the risk of early-age microcracking, an effect previously reported in systems containing highly exothermic aluminate phases [29,30]. Consequently, the high-CSA mixtures may have benefited from a more gradual and thermally stable hydration process, leading to a denser and more uniform microstructure. This mechanism further explains why the 45–60% CSA systems in this study did not exhibit the mechanical instability occasionally reported in mixtures with high CSA contents and insufficient hydration control.

These observations are consistent with recent findings on CSA–OPC systems. Studies by Huang et al. [13] and Nie et al. [15] showed that moderate CSA replacements may temporarily reduce early strength due to competitive hydration and limited water availability, which aligns with the behaviour of the 15–30% CSA mixtures in this study. Conversely, high CSA replacement levels (≥45%) have been shown to restore or enhance strength when mixture design supports complete ye’elimite hydration, as demonstrated by Hossein et al. [9] and confirmed in seawater- and chloride-exposed CSA binders [28,29]. The pronounced reductions in sorptivity and gas permeability observed in this study also align with pore-refinement mechanisms described by Ke et al. [4], Ioannou et al. [6], and Acartürk et al. [7], who reported that CSA hydration reduces capillary connectivity and transport pathways. Recent advances in pore-structure engineering, such as CO2-based foaming [11] and time-domain pore-structure characterization of CSA-modified UHPC [10], further support the microstructural densification trends observed here. The excellent freeze–thaw resistance of CSA-modified concretes in this study is likewise consistent with findings from Qadri et al. [1], de Bruyn et al. [2], and Huang et al. [3], who showed that CSA–OPC binders can withstand severe cyclic freezing without air entrainment due to reduced permeability and limited internal saturation. The correlation between permeability and frost durability observed in the present mixtures, particularly at w/c = 0.45, reinforces the mechanisms identified in the literature.

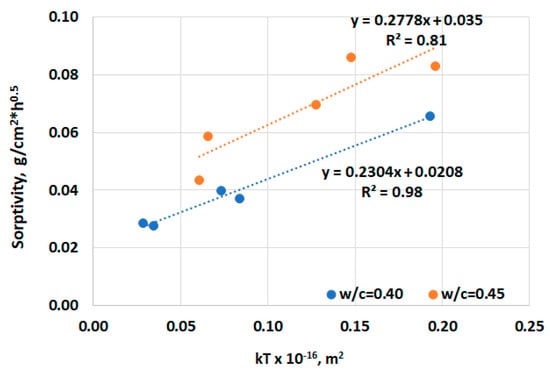

A pronounced reduction in both gas permeability and sorptivity was observed with increasing CSA content, confirming that CSA hydration refines the pore structure and decreases capillary connectivity. As shown in Figure 6, sorptivity exhibited a strong positive correlation with the gas permeability coefficient kT for both w/c ratios. The correlation was particularly strong for w/c = 0.40 (R2 = 0.98), while a slightly weaker but still significant correlation was found for w/c = 0.45 (R2 = 0.81). These findings suggest that both parameters are governed by pore connectivity and microstructural densification. Similar relationships have been reported in the literature, where sorptivity has been shown to scale with gas and liquid permeability due to their shared dependence on pore connectivity and tortuosity [4,6]. Ke et al. [4] reported that CSA-modified pastes exhibit reduced sorptivity and permeability due to capillary pore refinement, while Ioannou et al. [6] observed consistent reductions in transport properties across a range of w/c ratios in CSA- and SCM-containing systems.

Figure 6.

Correlation between sorptivity and the gas permeability coefficient kT for concretes with different water-to-cement ratios (w/c = 0.40 and 0.45).

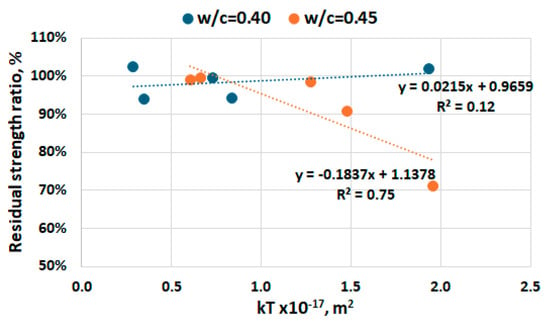

The improvement in freeze–thaw resistance directly reflects the microstructural and transport-related changes induced by CSA incorporation. As shown in Figure 7, concretes with lower gas permeability and sorptivity generally maintained higher residual compressive strength after 120 freeze–thaw cycles. For mixtures with w/c = 0.45, a moderate negative correlation (R2 = 0.75) was observed between the gas permeability coefficient (kT) and the residual strength ratio, indicating that higher permeability is associated with greater frost-induced strength loss. In contrast, for w/c = 0.40, the residual strength remained nearly constant (R2 = 0.12), suggesting that once the microstructure becomes sufficiently dense, permeability no longer governs frost resistance.

Figure 7.

Correlation between the residual compressive strength ratio after 120 freeze–thaw cycles and the gas permeability coefficient kT for concretes with varying water-to-cement ratios.

These observations indicate that the enhanced freeze–thaw durability of CSA-modified concretes arises from pore refinement and the restriction of moisture transport. This interpretation of microstructural improvement is based on the observed correlations and trends and is consistent with mechanisms reported in previous microstructural studies [4,30,31]. Consequently, even non-air-entrained CSA–OPC concretes demonstrated excellent stability after 120 freeze–thaw cycles, retaining almost their full compressive strength compared with unfrozen reference specimens. These findings align with earlier reports [2,5,32,33], showing that CSA-blended concretes exhibit superior freeze–thaw performance even without intentional air entrainment.

The results reveal a clear interdependence between strength development, transport properties, and frost resistance. The incorporation of CSA cement simultaneously improves mechanical stability and durability by reducing permeability, sorptivity, and moisture transport. These effects are particularly pronounced at CSA contents above 30% and for w/c ratios below 0.45, confirming that CSA–OPC hybrid binders provide a balanced and durable solution for high-performance concretes exposed to severe environmental conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study provides an integrated evaluation of the mechanical performance and durability of CSA–OPC concretes with varying CSA replacement levels and water-to-cement ratios. The results clearly demonstrate that the incorporation of CSA cement fundamentally influences hydration processes, pore structure formation, and long-term behaviour. The following conclusions can be drawn:

- CSA content strongly affects strength development.

Moderate CSA replacement (15–30%) resulted in slightly reduced early-age compressive strength due to competitive hydration and temporarily limited ye’elimite reaction. However, higher CSA contents (45–60%) promoted extensive ettringite formation and matrix densification, enabling full strength recovery and, in some cases, slight strength enhancement at 28 days. This behaviour was particularly evident in mixtures with w/c = 0.40.

- The water-to-cement ratio is a key factor in achieving optimal CSA hydration.

Mixtures with w/c = 0.40 consistently exhibited higher mechanical strength, reduced capillary porosity, and more refined pore structures compared with those at w/c = 0.45. These findings confirm that controlled water availability enhances CSA hydration efficiency and supports the development of a compact, stable microstructure.

- CSA significantly improves transport-related durability.

Sorptivity and gas permeability decreased markedly with increasing CSA content, particularly beyond 30%. The strong correlation between sorptivity and the permeability coefficient kT indicates that CSA enhances durability primarily by refining the pore structure and reducing capillary connectivity, thereby lowering susceptibility to aggressive environmental exposures.

- CSA-modified concretes exhibit excellent freeze–thaw resistance.

Even without air entrainment, mixtures containing ≥30% CSA retained nearly 100% of their initial compressive strength after 120 freeze–thaw cycles. This performance is attributed to reduced permeability, limited internal saturation, and the formation of a stable pore structure during CSA hydration. For w/c = 0.45, the moderate correlation between kT and the residual strength ratio further confirms the critical role of permeability in frost resistance.

- CSA–OPC hybrid binders provide a durable and sustainable solution for high-performance concrete.

The combined results show that well-designed CSA–OPC mixtures can achieve a favourable balance between mechanical performance and long-term durability. High CSA contents (45–60%) combined with low w/c ratios produced concretes with dense microstructures, low transport coefficients, and excellent resistance to freeze–thaw degradation.

The findings highlight the potential of CSA cement as an effective component in high-performance and durable concretes. Future research should include detailed microstructural characterization using advanced analytical techniques and long-term exposure studies to further elucidate the mechanisms governing pore refinement and durability in CSA–OPC systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J.; methodology, R.J.; validation, R.J., and D.J.-N.; formal analysis, R.J. and D.J.-N.; investigation, R.J. and M.B.; resources, R.J.; data curation, R.J. and D.J.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J. and D.J.-N.; writing—review and editing, R.J., D.J.-N., and M.B.; supervision, R.J.; funding acquisition, R.J. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSA | Calcium sulfoaluminate cement |

| C4A3Ŝ | Ye’elimite |

| OPC | Ordinary Portland cement |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| RCA | Recycled concrete aggregate |

| SSD | Saturated-surface-dry |

| w/c | Water/cement ratio |

References

- Qadri, F.; Nikumbh, R.K.; Jones, C. Freeze–Thaw Durability and Shrinkage of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Concrete with Internal Curing. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruyn, K.; Bescher, E.; Ramseyer, C.; Hong, S.; Kang, T.H.-K. Pore Structure of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Paste and Durability of Concrete in Freeze–Thaw Environment. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2017, 11, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Pudasainee, D.; Gupta, R.; Liu, W.V. The Performance of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement for Preventing Early-Age Frost Damage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 254, 119322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Xie, S. Pore Characteristics of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Paste with Impact of Supplementary Cementitious Materials and Water to Binder Ratio. Powder Technol. 2021, 387, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Okoronkwo, M.U.; Kumar, A.; Ma, H. Durability of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Concrete. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2020, 21, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, S.; Paine, K.; Reig, L.; Quillin, K. Performance Characteristics of Concrete Based on a Ternary Calcium Sulfoaluminate–Anhydrite–Fly Ash Cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 55, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarturk, B.C.; Sandalci, I.; Hull, N.M.; Basaran Bundur, Z.; Burris, L.E. Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement and Supplementary Cementitious Materials-Containing Binders in Self-Healing Systems. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 141, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhan, S.; Xu, Q.; He, K. Mechanical Performance and Chloride Penetration of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Concrete in Marine Tidal Zone. Materials 2023, 16, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein, H.A.; Nabawy, B.S.; Sanad, S.A.; El-Alfi, E.A. Manufacturing of High-Quality Green CSA-Supported OPC Cement with Optimum Physical and Mechanical Properties. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, M.H.; Lee, N. Time-Domain Characterization of the Pore Structure in Ultra-High Performance Concrete with Partial Substitution of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2026, 165, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Niu, J. Improvement of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Foamed Concrete by Carbon Dioxide Foam: Hydration Activation and Pore Structure Optimization. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 163, 106162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. The Role of Polymer in Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement-Based Materials. In Concrete-Polymer Composites in Circular Economy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Pudasainee, D.; Gupta, R.; Liu, W.V. Extending Blending Proportions of Ordinary Portland Cement and Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Blends: Its Effects on Setting, Workability, and Strength Development. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2021, 15, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachtar, J. Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement as Binder for Structural Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, S.; Zhang, Q.; Lan, M.; Zhou, J.; Xu, M.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Fundamental Design of Low-Carbon Ordinary Portland Cement-Calcium Sulfoaluminate Clinker-Anhydrite Blended System. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 139, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, R.; Govin, A.; Grosseau, P. Influence of Polycarboxylate Superplasticizer, Citric Acid and Their Combination on the Hydration and Workability of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 147, 106513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Halee, B.; Suraneni, P. Effect of calcium sulfoaluminate cement prehydration on hydration and strength gain of calcium sulfoaluminate cement-ordinary portland cement mixtures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 112, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, A.; Carević, V.; Marinković, S. Impact of the water-curing time on the carbonation initiation period of high-volume limestone powder concrete. Građevinski Materijali i Konstrukcije 2025, 68, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinárik, L.; Kopecskó, K.; Borosnyói, A. Properties of cement mortars in fresh and hardened condition influenced by combined application of SCMs. Építőanyag. J. Silic. Based Compos. Mater. 2016, 68, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-B-06265:2022-08; Concrete—Requirements, Properties, Production and Conformity—National Supplement to PN-EN 206+A2:2021-08. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warszawa, Poland, 2022.

- PN-EN 12390-3:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- PN-EN 12390-6:2024-04; Testing of Concrete—Part 6: Tensile Splitting Strength of Test Specimens. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warszawa, Poland, 2024.

- PN-B-06250:1988; Ordinary Concrete—Technical Requirements and Testing. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warszawa, Poland, 1988.

- Kubissa, W.; Jaskulski, R. Measuring and Time Variability of The Sorptivity of Concrete. Procedia Eng. 2013, 57, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrent, R.; Frenzer, G. A Method for the Rapid Determination of the Coefficient of Permeability of the “covercrete”. In Proceedings of the International Symposium Non-Destructive Testing in Civil Engineering (NDT-CE), Berlin, Germany, 26–28 September 1995; Schickert, W.G., Wiggenhauser, H., Eds.; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Zerstörungsfreie Prüfung (DGZfP): Berlin, Germany, 1995; pp. 985–992. [Google Scholar]

- Jóźwiak-Niedźwiedzka, D.; Choinska Colombel, M.; Brachaczek, A.; Dąbrowski, M.; Ośko, J.; Kuć, M. Gas Permeability and Gamma Ray Shielding Properties of Concrete for Nuclear Applications. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 429, 113616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, M.; Skocek, J.; Bullerjahn, F.; Haha, M.B. Effect of Retarders on the Early Hydration of Calcium-Sulpho-Aluminate (CSA) Type Cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 84, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, K.; Xu, L.; Duan, Z.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Z. Interaction of Carbonated Recycled Concrete Powder with Calcium Sulfoaluminate-Belite Cement: Early Hydration Kinetics and Microstructure Evolution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 493, 143223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Dong, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, X.; Yu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Guo, X. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Aluminate Cement Paste with Blast Furnace Slag at High Temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 228, 116747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Jing, S.; Pang, B.; Wang, P.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Song, X.; Liu, L. Sustainable Infrastructure Repair Materials: Self-Emulsifying Waterborne Epoxy Enhanced CSA Cement with Superior Shrinkage Mitigation Properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xie, N.; Ou, J.; Zhou, G. A Review of the Calcium Sulphoaluminate Cement Mixed with Seawater: Hydration Process, Microstructure, and Durability. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, T.; Ma, Y.; Qian, H. Hydration and Mechanical Properties of Calcium Sulphoaluminate Cement Containing Calcium Carbonate and Gypsum under NaCl Solutions. Materials 2022, 15, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Gao, X.; Wang, K.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Li, W. Hydration Mechanism and Early Frost Resistance of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 239, 117862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).