1. Introduction

Chronic diseases such as diabetes require continuous and comprehensive management strategies that extend beyond pharmacological treatment. Effective care relies on long-term adherence to therapeutic recommendations, including medication intake, dietary habits, physical activity, and sleep hygiene. However, adherence remains a major challenge, with poor compliance contributing to disease progression, complications, and increased healthcare costs [

1]. Recent estimates highlight that up to 50%, on average, of patients with chronic diseases in developed countries fail to adhere to treatment recommendations [

2,

3], underscoring the urgent need for innovative monitoring frameworks.

In parallel, the IoT and advances in sensor miniaturization have enabled the development of ubiquitous monitoring systems that capture multimodal data within patients’ daily environments. These systems leverage wearable devices, ambient sensors, and wireless communication protocols to provide continuous insights into behaviours relevant for adherence assessment. Despite these advances, two significant gaps persist: (i) the absence of standardized methodologies that adapt HAR to clinical adherence monitoring, and (ii) the limited integration of anomaly detection frameworks capable of flagging deviations in daily routines that compromise treatment success.These limitations are compounded by the multifactorial nature of non-adherence, which includes therapy complexity, poor education, and psychosocial barriers [

4,

5,

6].

Research has demonstrated that smart home sensors can reveal digital behaviour markers—such as sleep duration, restlessness, bathroom use, walking speed, and time spent outside the home—that correlate with treatment side effects and disease progression [

7]. By comparing these markers during periods of self-reported illness versus well-being, Cook and colleagues showed that deviations in daily behaviours provide valuable proxies for clinical symptoms. This perspective introduces a powerful paradigm: adherence to treatment is not only measurable through direct observation of medication intake but also through indirect behavioural markers that reflect the patient’s capacity to sustain prescribed routines. Similar findings support that behavioural indicators serve as effective proxies for symptoms and adherence challenges [

8], especially in patients managing multiple chronic conditions.

Building upon this foundation, recent studies have proposed methodologies to formalize adherence monitoring through sensor-based platforms. Díaz-Jiménez et al. [

9] introduced the AI2EPD framework for patients with type 2 diabetes, combining activity recognition, therapeutic contracts, and active patient participation to structure adherence evaluation. Complementarily, Fernández-Basso et al. [

10] applied fuzzy data fusion to discover frequent behavioural patterns in sensorized households of diabetic patients, enhancing interpretability through linguistic labels. In addition, novel approaches integrating large language models (LLMs) with fuzzy summarization methods have shown promise in transforming raw sensor data into interpretable adherence narratives [

11].

These trends reflect the growing consensus that effective adherence monitoring must integrate real-world behaviour data with intelligent, interpretable systems—especially in chronic disease contexts where patients often struggle to maintain complex routines over time [

12]. In clinical trials, real-time IoT-based interventions have been proven to enhance medication adherence, increase physical activity, and reduce sedentary behaviour, particularly among older adults with mild cognitive impairment—a population highly vulnerable to non-adherence [

13]. These findings align with the growing consensus that treatment adherence is not merely a matter of taking medication on time but involves a sustained engagement with multiple health-promoting behaviours—each of which can now be effectively captured, analysed, and visualised through IoT platforms.

Despite these advances, existing approaches rarely integrate behavioural markers with explicit treatment adherence models, nor do they provide systematic anomaly annotation to guide clinical decision making. This gap motivates the present work, which introduces a hybrid methodology for treatment adherence monitoring that combines IoT-based activity recognition, fuzzy logic for uncertainty management, and anomaly detection for deviations in adherence-related behaviours.

The contributions of this work are centred on the integration of IoT-based human activity recognition with fuzzy anomaly detection to evaluate treatment adherence in patients with chronic conditions. First, the study introduces a refined recognition scheme capable of mapping multimodal sensor data—collected from wearable devices, BLE beacons, and ambient sensors—into clinically relevant treatment-related activities. Second, it incorporates a fuzzy logic module that enables the detection and annotation of anomalies in adherence routines, thus addressing the uncertainty and variability inherent in real-world daily behaviours. Third, the proposed methodology builds upon and extends Diane Cook’s notion of digital behaviour markers, embedding them within a structured adherence framework that facilitates both monitoring and visualization. Finally, the work presents a validation scenario that demonstrates how adherence can be assessed not only through explicit actions, such as medication intake, but also through behavioural deviations captured by continuous sensing.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews previous research on treatment adherence, summarizing validated self-report instruments and recent advances in digital monitoring that provide the conceptual basis for the proposed approach.

Section 3 presents the proposed hybrid methodology, detailing the system architecture, activity definition, fuzzy data fusion process, and the integration of behavioural markers with explicit treatment-related activities.

Section 4 describes the validation scenario based on simulated multimodal data from real data, outlining the dataset generation, preprocessing, and evaluation of adherence indicators.

Section 5 analyses the implications of the results, highlights the advantages of the fuzzy integration for chronic disease management, and discusses limitations and future directions, while the final section summarises the main contributions and clinical relevance of the proposed framework.

2. Related Works

Monitoring adherence to treatment is a long-standing challenge in healthcare, especially for chronic diseases requiring sustained behavioural commitment. Numerous validated tools have emerged to quantify adherence, ranging from self-reported scales to real-world data and sensor-based monitoring.

Self-reported instruments remain the most widely used method due to their low cost, scalability, and ease of administration in clinical and research settings. A recent systematic review by Rickles et al. [

14] identified 17 validated, primary care-focused tools to measure medication adherence. These include commonly used scales such as the Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS), Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS), and Self-Efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS). The review highlights that each tool varies significantly in psychometric strength, administration time, and contextual suitability, suggesting that tool selection must be tailored to study objectives and patient characteristics.

Building upon this, Nassar et al. [

15] compared 12 commonly used self-report adherence instruments and emphasized the trade-offs between sensitivity, specificity, and respondent burden. Their review points out that tools like MMAS are useful for screening non-adherence, while others such as SEAMS and BMQ (Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire) offer deeper insights into behavioural and cognitive barriers.

To improve adherence assessment in community pharmacies, Arnet et al. [

16] developed and validated the 15-STARS questionnaire, a novel self-report instrument designed to detect modifiable adherence barriers. Constructed through rigorous psychometric testing, it enables pharmacists to stratify patients based on behavioural risk factors and deliver tailored interventions, demonstrating the utility of structured adherence screening outside clinical settings.

Another innovation is the OMAS-37 scale developed by Larsen et al. [

17], a non-disease-specific survey capturing patient beliefs, barriers, and behavioural consistency across treatment regimens. The tool was validated on over 1000 patients and demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s

), providing cut-off points for clinical interpretation. Its flexibility makes it suitable for primary care and research in multimorbidity contexts.

Traditional self-report instruments often fall short in patients with complex treatment regimens. To address this, Sidorkiewicz et al. [

18] proposed a validated tool that allows assessment of adherence to each individual drug in a patient’s regimen. This granularity is critical in polypharmacy scenarios, where adherence may vary significantly across medications. Their results demonstrated good feasibility and construct validity, reinforcing the need for fine-grained measurement approaches in older adults and multimorbid patients.

Mortelmans et al. [

19] advanced this perspective by conducting a longitudinal study combining pill counts, diaries, and validated questionnaires in older patients with polypharmacy. The study demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of multimethod adherence monitoring in daily life and emphasized the complementary value of combining subjective and objective tools. These findings resonate with IoT-based frameworks aiming to infer adherence indirectly through behaviour.

A critical review by Lavsa et al. [

20] compared major validated scales and concluded that while the MAQ (Medication Adherence Questionnaire) is the most versatile for general use, tools like MARS and SEAMS offer stronger insight into motivation and self-efficacy. The authors argue that no gold standard exists, and recommend multitool triangulation when accuracy is paramount—a concept also applicable to behavioural sensing frameworks.

Although most traditional tools rely on self-report, their core constructs—barriers, beliefs, routines, and behavioural consistency—are increasingly being translated into digital proxies. For example, belief-based barriers such as medication fatigue or perceived side effects may manifest, such as sleep disturbance, reduced activity, or altered bathroom routines—signals that can be captured by ambient or wearable sensors. The validated constructs from these instruments, thus, serve as theoretical scaffolds for designing IoT-based adherence monitoring systems.

Moreover, tools like 15-STARS [

16,

21,

22] and OMAS-37 [

17] suggest that adherence is less about isolated behaviours and more about behavioural patterns embedded in daily routines—supporting recent trends in digital health to fuse behavioural sensing with fuzzy reasoning and anomaly detection, as proposed in this work.

Taken together, these studies underscore that validated adherence tools offer foundational constructs, metrics, and interpretative thresholds that can inform, calibrate, and validate new sensor-driven frameworks for chronic disease monitoring.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodology proposed in this work introduces a hybrid framework for monitoring treatment adherence through sensor-based HAR, fuzzy data fusion, and anomaly detection. The novelty lies in considering adherence not only as the direct observation of prescribed actions (e.g., medication intake) but also as the capacity of the patient to maintain healthy behavioural routines that serve as indirect markers of compliance. This integrated perspective enables a more comprehensive evaluation of treatment adherence in real-world scenarios.

3.1. System Design and Architecture

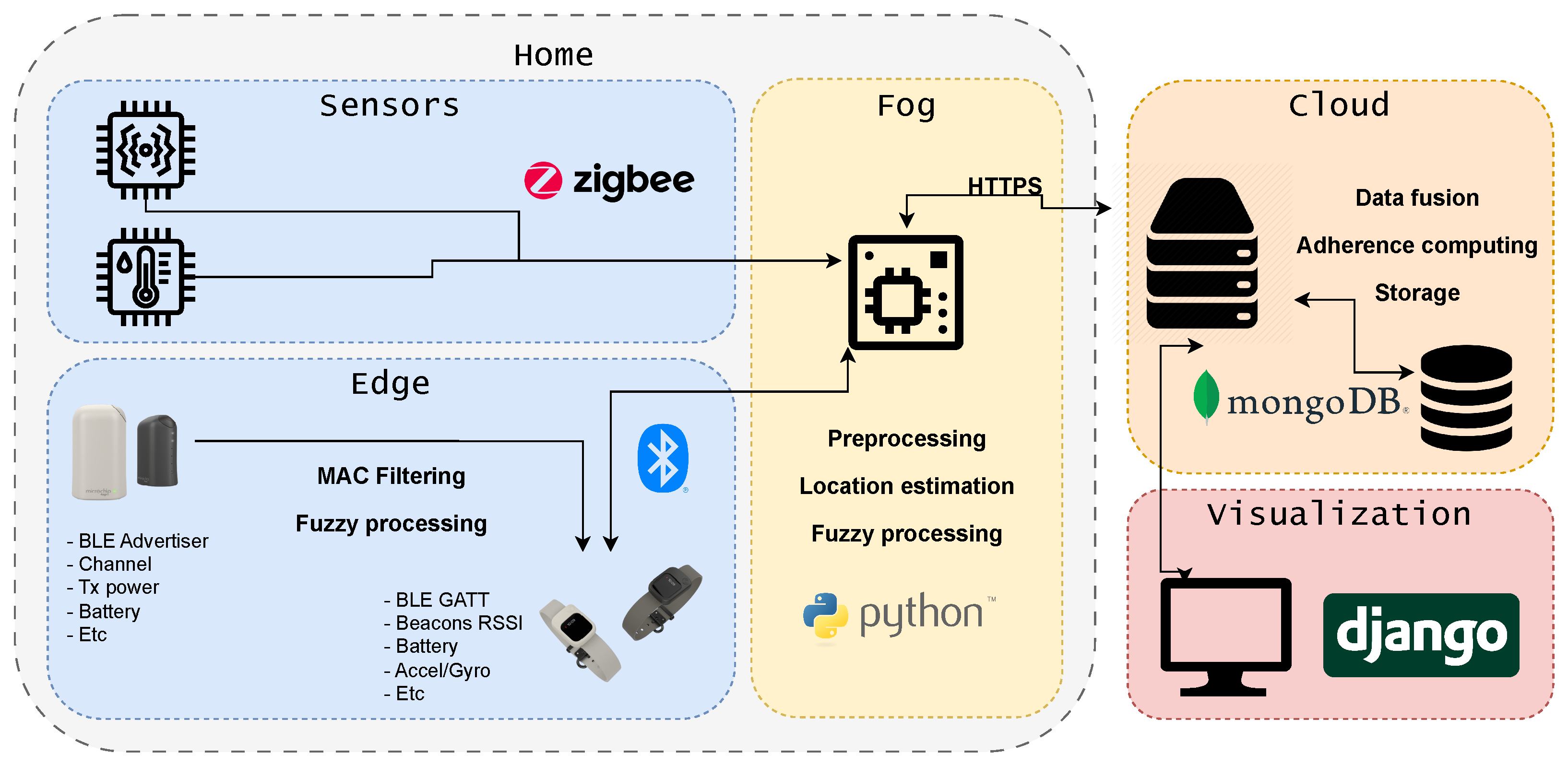

The overall system architecture is organised into four interdependent layers that collectively ensure scalability, interoperability, and operational robustness across the entire sensing–processing pipeline. As illustrated in

Figure 1, these layers establish a continuous flow from multimodal IoT data acquisition to high-level behavioural interpretation and adherence-oriented analytics. Each layer fulfils a specific functional role, yet they operate cohesively to support real-time monitoring, secure data handling, and the generation of indicators. The following subsection describe the structure and responsibilities of each architectural layer.

Sensor Layer: This include ambient sensors (e.g., motion, humidity, temperature, and cabinet-opening detectors). These devices provide heterogeneous but complementary information about patient routines.

Edge-Fog Layer: This performs preprocessing tasks such as noise filtering, RSSI stabilisation for localisation, and basic event detection. Operating close to the data source reduces latency and allows the system to operate even with intermittent network connectivity.

Cloud Layer: This executes advanced processes including data fusion, fuzzy reasoning, and computation of adherence indicators. It also manages long-term storage and interoperability with healthcare information systems.

Visualisation Layer: This provides dashboards and linguistic summaries that present adherence levels, detected anomalies, and temporal trends in a format interpretable by clinicians and patients.

This layered design guarantees the modularity required for deployment in heterogeneous clinical contexts.

3.2. Sensor Reliability and Data Quality Mitigation

In practical IoT deployments, sensor data rarely arrives in a clean or fully stable form. Motion, proximity, environmental and wearable devices are all affected—often in different ways—by noise, gradual drift, missing samples, or occasional hardware failures. These imperfections introduce distortions that, if unaddressed, can propagate into the behavioural indicators used to assess adherence. For this reason, the system integrates a set of complementary mechanisms designed to stabilise incoming data before it reaches higher-level processing stages.

Signal preprocessing constitutes the first line of defence and is intentionally more comprehensive than the other components. Raw streams are cleaned and temporally harmonised so that transient artefacts do not dominate the interpretation. Smoothing filters reduce jitter in accelerometer and ambient signals, while outlier detection suppresses extreme values generated by sensor instability or abrupt environmental changes. Controlled resampling helps regularise the temporal structure of the data, preventing irregular acquisition intervals from biasing downstream fusion. This preprocessing stage absorbs much of the volatility inherent in low-cost sensors and mirrors established practices in smart health environments where data quality fluctuates considerably.

Managing missing data and mitigating drift represent a second, more targeted effort. Short gaps—common in wireless sensors affected by interference—are reconstructed using local temporal estimators such as sliding-window interpolation. This ensures continuity without artificially inflating or dampening behavioural patterns. Sensor drift, which often accumulates slowly over long periods, is corrected through periodic baseline comparisons and cross-validation across sensors deployed in the same location, allowing the system to detect when a device has gradually deviated from expected operating ranges.

Multimodal data fusion further strengthens robustness by exploiting redundancy across sensing modalities. Because motion, ambient, proximity, and wearable signals tend to degrade in different ways, combining them provides resilience against isolated faults. Fuzzy fusion strategies adjust the relative influence of each sensor depending on its level of consistency with the global context. A sensor behaving erratically has its weight reduced, while stable signals provide a stronger foundation for activity interpretation. Additionally, rather than treating sensor activations as crisp events, fuzzy membership functions describe gradual transitions, allowing the system to accommodate small fluctuations without misclassifying the underlying behaviour. This soft reasoning prevents minor signal perturbations from generating false events, particularly in periods of reduced activity or during environmental changes that temporarily affect signal strength.

Finally, contextual reasoning filters address artefacts that contradict the broader behavioural pattern. For example, motion detections in rooms where the user is not located, or isolated environmental changes unsupported by complementary sensors, are down-weighted or suppressed.

3.3. Activity Definition and Behavioural Markers

Treatment adherence is addressed in this work as a multidimensional construct that combines two complementary dimensions: explicit treatment-related activities, which correspond to prescribed therapeutic actions, and behavioural markers, which describe contextual routines and lifestyle patterns that influence or condition adherence. This dual approach allows the detection of both direct compliance with medical instructions and subtle deviations that may precede critical health events.

3.3.1. Explicit Treatment-Related Activities

Explicit activities represent actions directly linked to the therapeutic contract. Five core categories were defined, each associated with specific sensors and measurable key treatment indicators (KTIs):

Medication intake: Registered through interaction with dedicated storage areas (e.g., medicine cabinets equipped with opening sensors) and temporally validated against prescription schedules. The main KTI is the proportion of doses taken within the prescribed time windows.

Physical activity: Evaluated through wearable accelerometers, step counters, and BLE-based indoor localisation. KTIs include daily step count, activity duration, and frequency of exercise sessions. Deviations may reflect sedentary behaviours that compromise treatment effectiveness.

Nutrition: Identified through activity in the kitchen environment, such as interaction with refrigerators or cabinets and presence during mealtimes. KTIs comprise the number of main meals per day, regularity of intake, and avoidance of prolonged fasting.

Sleep: Monitored via ambient motion sensors, wearable sleep trackers, and temporal inactivity patterns. KTIs include total sleep duration and sleep onset latency.

Hygiene: Assessed by detecting bathroom routines such as tooth brushing (short, localised motions) and showering (humidity and temperature variations). KTIs are defined in terms of daily frequency and regularity, relevant for preventing infections and maintaining overall health.

3.3.2. Behavioural Markers

Behavioural markers extend adherence evaluation by capturing contextual patterns that, while not strictly prescribed, exert a significant influence on health outcomes and therapeutic compliance. The following markers were incorporated:

Mobility and time outside the home: Estimated from door-opening events combined with localisation data. Adequate mobility indicates social engagement and physical independence, while reduced outings may suggest isolation, depression, or frailty.

Daily activity regularity: Defined as the temporal stability of activity patterns across consecutive days. A stable distribution of meals, exercise, and rest is associated with higher adherence, while irregular rhythms may indicate behavioural disorganisation or cognitive decline.

Sleep quality and fragmentation: Quantified through sleep duration, and number of nocturnal interruptions. Poor sleep continuity affects both physiological control (e.g., glucose regulation) and adherence to daily routines.

Sedentary behaviour: Measured by prolonged inactivity intervals detected by motion sensors and wearables. Extended sedentary periods are linked to metabolic risk and lower adherence to prescribed physical activity.

Social interaction proxies: Inferred from the frequency and duration of visits (detected by door sensors and environmental activity) or conversations captured by optional voice-activity sensors. Social withdrawal often correlates with non-adherence and worsening health outcomes.

3.4. Fuzzy Data Fusion

Sensor data streams present fluctuations and imprecision, particularly in indoor environments where multipath propagation, interference, and user mobility generate noise in the measurements [

23]. To address this challenge, a fuzzy data fusion methodology is applied, which combines fuzzy proximity values, temporal windows, and aggregation operators. This process allows sensor information to be expressed in linguistic terms and combined into robust adherence indicators.

3.4.1. Fuzzification of Sensor Variables

Each raw measurement

is defined as a tuple:

where

denotes the beacon or sensor,

the observed value (e.g., RSSI, temperature, step count), and

the timestamp. The fuzzification step maps

into a membership degree

for a fuzzy set

A corresponding to a linguistic term.

For example:

Location (RSSI): with trapezoidal membership functions.

Step count: with triangular functions centred on thresholds (e.g., 0–100, 100–1000, >1000 steps/h).

Sleep activity (motion absence): based on PIR sensor inactivity intervals and data from the wristband.

Humidity (bathroom): with trapezoidal functions around clinically relevant values (50–80%).

3.4.2. Fuzzy Temporal Windows

To stabilise fluctuating signals, a fuzzy temporal window

is defined, with membership function

assigning higher weight to recent samples. For each

, the combined proximity degree is

where

denotes the temporal distance to the current instant

.

3.4.3. Aggregation by Activity

Sensor values from the same semantic area are aggregated within each temporal window:

where

is the aggregated membership for area or activity

l. The area (or activity) with the maximum

is selected as the most probable at each instant:

3.4.4. Definition of Adherence Activities

Using this framework, each adherence-related activity is defined with specific fuzzy rules:

The final membership is aggregated over daily doses to compute an adherence score.

The score is calculated as proportion of fulfilled exercise sessions.

Adherence is expressed as number of meals detected vs. expected meals.

Complementary markers include fragmentation (# interruptions/night) and total sleep duration.

Separate fuzzy sets are defined for daily tooth brushing and shower frequency.

3.4.5. Global Adherence Score

The global adherence score for a day is calculated as follows:

where

is the fuzzy membership degree of adherence to activity

and

is its clinical weight (e.g., medication

, physical activity

, nutrition

, sleep

, hygiene

).

Clinical Relevance and Evidence Sources

The clinical relevance weights assigned to each activity are grounded on two primary sources: expert knowledge in diabetes care and international diabetes management guidelines. This ensures that the weighting scheme reflects evidence-based priorities and aligns with established standards of clinical practice.

Expert-Derived Weighting

A multidisciplinary panel of diabetes specialists (endocrinologists, nurses, and clinical researchers) establishes the initial clinical importance of each activity. Their judgments reflect long-standing clinical experience regarding behaviours that most strongly influence glycaemic stability, treatment adherence, and the risk of events such as hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia.

Guideline Validation

The expert-derived weights are cross-validated against diabetes guidelines, which define the behavioural and physiological domains requiring continuous monitoring. These guidelines consistently highlight the relevance of

Sleep quality and regularity;

Physical activity and sedentary patterns;

Meal-related behaviours;

Stress and daily routine changes;

Adherence to prescribed therapy.

Guideline Sources

The following internationally recognized guideline sources support these:

American Diabetes Association (ADA). Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes [

24].

International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD). Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines [

25].

Inter-Individual Variability

Although the weighting scheme is grounded in expert consensus and guideline-based evidence, the relative importance of each activity is not fixed. It can vary from one individual to another depending on the following:

The person’s treatment regimen (e.g., insulin pump);

Comorbidities (e.g., sleep apnoea, neuropathy, cardiovascular disease);

Lifestyle and occupational routine;

Behavioural adherence patterns;

Specific clinical objectives (e.g., reducing nocturnal hypoglycaemia, improving morning stability).

Personalisation of Relevance Weights

The system allows the clinical-relevance weights to be personalized and adjusted to each user’s specific profile and evolving therapeutic needs. This patient-centred adaptation is essential in diabetes management and other chronic diseases, where inter-individual variability in behavioural patterns and glycaemic responses is well documented in the clinical literature.

3.4.6. Worked Example

Suppose at 08:15 a cabinet opening event is detected in the kitchen with RSSI = −55 dBm, and the prescribed morning dose window is 08:00–09:00. After fuzzification:

The fuzzy rule for medication intake gives

With

, this contributes

to the daily score. Analogous calculations are performed for meals, exercise, sleep, and hygiene, yielding the final adherence profile.

3.5. Integration of Activities and Markers

The proposed framework integrates explicit treatment-related activities and behavioural markers into a unified evaluation model. Each explicit activity is assessed with respect to its associated KTIs, while behavioural markers provide contextual evidence about lifestyle stability and health maintenance. This dual perspective enables both a quantitative assessment of adherence and a qualitative interpretation of deviations.

3.5.1. Evaluation of Explicit Activities

For each activity , a membership degree is calculated based on the degree of compliance with its KTI. For example, in the case of medication intake, is proportional to the number of doses taken within the prescribed time window. For physical activity, reflects the proportion of daily activity goals achieved. These measures ensure that each activity is anchored to clinical prescriptions.

3.5.2. Evaluation of Behavioural Markers

Behavioural markers capture contextual regularities such as daily rhythm, mobility, circadian consistency, and social interaction. Each marker is quantified by a fuzzy membership degree describing its alignment with healthy routines. For instance, sleep fragmentation is evaluated by mapping the number of nocturnal interruptions into the fuzzy sets . Similarly, mobility is assessed by the proportion of time spent outside the home compared with a baseline reference.

3.5.3. Fusion of Activities and Markers

The integration is achieved through a fuzzy multicriteria aggregation process. The overall adherence score at day

d is defined as follows:

where

and

represent clinical relevance weights for each activity and marker, respectively. Medication intake typically receives the highest weight, while behavioural markers are moderating factors.

3.5.4. Detection of Compound Deviations

Adherence is formalized as the alignment between observed activities and the therapeutic contract established by healthcare professionals. The system computes adherence scores on a daily basis, considering both frequency and timing of the detected activities.

3.5.5. Anomaly Categorisation

Detected deviations are annotated as anomalies and classified into three categories:

Temporal anomalies: Activities performed outside the prescribed time windows (e.g., delayed medication intake).

Frequency anomalies: Activities missed or repeated abnormally (e.g., skipped exercise session or excessive napping).

Behavioural anomalies: Deviations in contextual routines (e.g., reduced mobility, prolonged sedentary periods, irregular sleep).

3.5.6. Integration of Multidomain Deviations

With this base, the integration allows the system to detect complex scenarios. For example,

High adherence to medication () but low regularity in sleep () suggests partial adherence with potential metabolic risk.

Adequate nutrition and sleep, combined with sedentary behaviour (), indicate long-term risk of deterioration despite short-term stability.

Declines in social interaction and mobility, even when explicit KTIs are fulfilled, may represent early warning signs of cognitive or motivational decline.

3.5.7. From Binary to Multidimensional Profiles

Unlike traditional binary classification (adherent/non-adherent), this model produces a multidimensional adherence profile, represented as a vector:

which characterises daily adherence across all explicit activities and behavioural markers. Longitudinal analysis of

across multiple days enables the detection of trends, anomalies, and progressive deviations. In this way, adherence is no longer a static label but a dynamic state that reflects the patient’s daily life and health condition.

3.6. Deep-Learning-Based Activity Detection and Temporal Membership Functions

When activities are recognized by a deep learning model, each event is represented as

where

is the detected activity and

denotes the temporal interval of execution. These activities are compared against the prescribed therapeutic windows

defined for each adherence dimension

.

3.6.1. Temporal Membership Function

To quantify adherence, we define a fuzzy temporal membership degree:

where

is the detected interval;

is the temporal tolerance added to the prescribed window;

is the maximum acceptable shift between detected and prescribed start times.

The first term measures the proportion of overlap between the prescribed and observed durations, while the second term penalizes deviations in start time.

3.6.2. Activity-Specific Examples

3.6.3. Global Adherence Score

Finally, the global adherence score is computed by weighted aggregation:

where

are clinician-defined importance weights for each adherence dimension.

3.7. Novelty of the Methodology

The originality of this proposal lies in unifying three dimensions that have traditionally been studied separately: (i) explicit treatment-related activities, (ii) implicit behavioural markers inspired by smart home research, and (iii) anomaly annotation based on fuzzy reasoning. By combining these elements into a standardized methodology, the proposed framework advances adherence monitoring beyond isolated metrics, offering a robust, interpretable, and clinically relevant tool.

5. Discussion

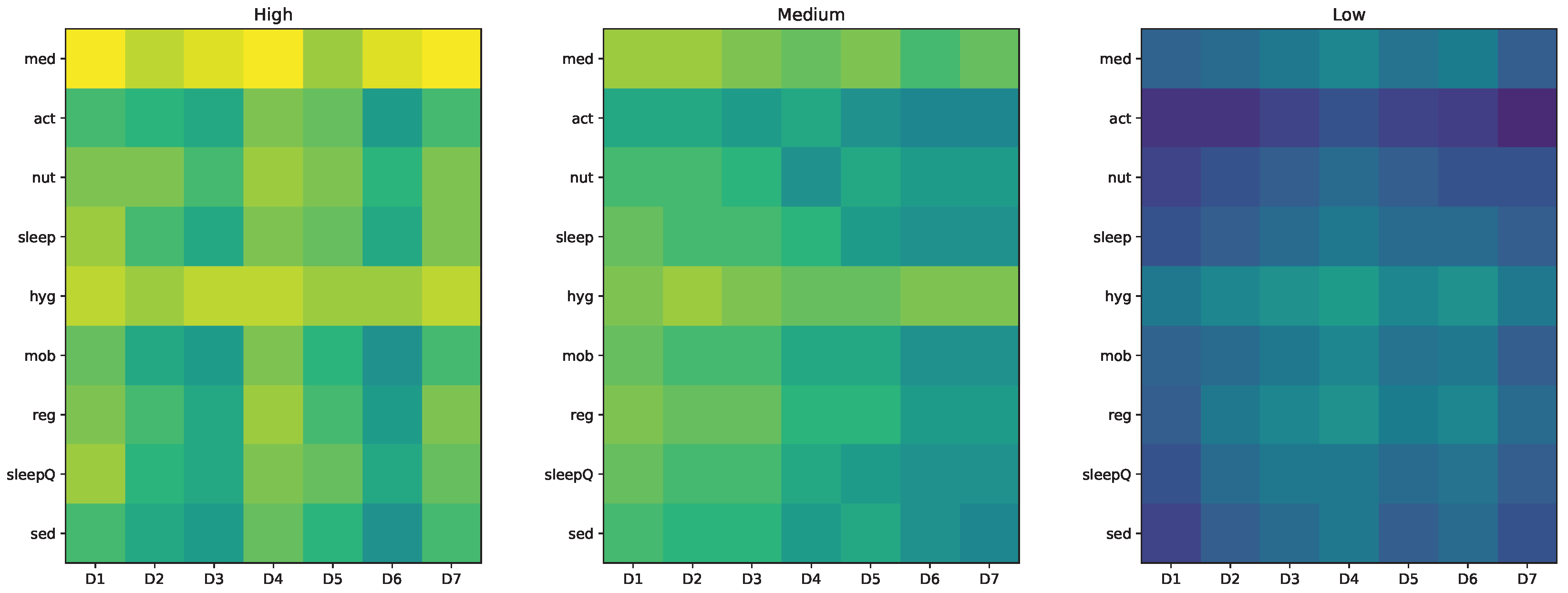

The present work introduces a unified framework for daily adherence assessment that brings together three dimensions traditionally analysed in isolation: (i) explicit treatment-related activities, (ii) implicit behavioural markers derived from smart home sensing, and (iii) anomaly characterisation through fuzzy reasoning. This integration constitutes the central contribution of the proposal, as it enables a more complete understanding of how patients manage their routines in real home environments. Although the evaluation is conducted using simulated data, the underlying patterns were modelled from real sensor deployments, ensuring realistic temporal dynamics and allowing the construction of three clearly differentiated adherence profiles.

5.1. A Unified View of Daily Adherence

The distinction between explicit and contextual components provides a structured basis for analysing adherence as a daily behavioural construct rather than a single binary event. The explicit component () captures how consistently patients follow treatment-related tasks such as medication intake or maintaining a regular sleep schedule. The contextual component () reflects how stable their behavioural environment is, measured through mobility, activity, sleep quality, and sedentarism.

The inclusion of a fuzzy anomaly layer adds an additional interpretative dimension. By identifying days in which behavioural deviations exceed normal variability, the model can recognise patterns that could precede disengagement or metabolic imbalance. This multilayered design aligns with emerging evidence showing that adherence is shaped not only by intentional self-care actions but also by the broader organisation of everyday life and the disruptions that occur within it.

5.2. Interpretation of the Three Patient Profiles

The simulated scenarios—constructed from realistic sensor traces—demonstrate the discriminative capacity of the framework. Profile A exhibits strong alignment between treatment routines and contextual organisation, producing consistently high adherence. Profile B captures moderate irregularity, with fluctuations that do not fully disrupt daily structure. Profile C represents behavioural fragility, characterised by reduced activity, fragmented sleep, and limited stability.

These differences emerge naturally from the model and confirm that both explicit tasks and behavioural structure jointly determine adherence. The daily vectors illustrate how adherence varies along multiple dimensions, offering a granular view that cannot be captured through classical single-metric approaches.

6. Conclusions

The proposed framework offers several advantages that extend beyond traditional adherence assessment methods and reinforce its applicability to real home environments. Its main strength lies in unifying three dimensions that are usually examined independently: (i) explicit treatment-related activities, (ii) contextual behavioural markers extracted from smart home evidence, and (iii) anomaly annotation through fuzzy reasoning. Bringing these elements together provides a coherent and structured view of daily adherence, allowing routines to be interpreted as a continuous behavioural process rather than as isolated events.

A second advantage is the flexibility provided by fuzzy modelling. By operating with graded membership values instead of rigid thresholds, the system represents adherence as a gradual spectrum, capturing partial compliance and small deviations that are common in everyday life. This makes the model resilient to noise, missing data and day-to-day variability—conditions that are inherent to IoT deployments in domestic environments. Furthermore, the use of linguistic labels and transparent rule sets strengthens interpretability, allowing clinicians to understand how sensor evidence leads to a given adherence outcome.

A third contribution of this work is the inclusion of a practical mechanism to evaluate activities obtained from deep learning models for human activity recognition. Detected events—such as meals, bouts of physical activity, or sleep intervals—can be aligned with the expected therapeutic routines using temporal tolerances and overlap criteria. This provides a consistent way to incorporate algorithmically inferred behaviour into the adherence computation, ensuring that the framework remains compatible with modern recognition pipelines without compromising interpretability. As a result, the system can integrate heterogeneous sources of evidence in a unified and clinically meaningful manner.

Finally, the multimodal structure of the daily adherence vectors facilitates longitudinal analysis, comparison across days and profiles, and early identification of behavioural drift. This enriches the monitoring capabilities of smart health systems and supports more proactive and personalised interventions in chronic disease management.

6.1. Limitations and Directions for Future Work

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this work. First, although the simulated profiles are grounded in patterns extracted from real home deployments, full validation of the framework requires long-term monitoring in diverse real-world settings. Differences in dwelling layout, sensor density, household composition, or cultural routines may influence behavioural markers, and these factors need to be assessed empirically to confirm the model’s generalisability. Second, the weighting scheme used for both treatment-related activities and behavioural markers is fixed and not personalised. Future developments should explore adaptive or patient-specific weighting strategies that better reflect individual clinical priorities, lifestyle characteristics, and disease progression. A third limitation relates to the sensing modality. While the current system relies on ambient sensors and wearable indicators, these sources may not fully capture socially relevant aspects of daily life. In particular, loneliness and reduced social interaction are known to affect adherence and overall health, yet they remain difficult to observe using motion or environmental sensors alone. Incorporating a complementary acoustic module based on low-level microphone activity rather than speech content could help identify prolonged silence, conversational patterns, or changes in daily sound environments. This addition would preserve privacy while providing a more complete view of the patient’s social context. Finally, although the evaluation framework is centred on Type 2 diabetes, where medication schedules, meal timing, physical activity, and sleep are central to disease management, its direct applicability to other chronic conditions requires adaptation. Different diseases emphasise distinct routines and behavioural markers, for example, respiratory events in COPD, mobility fluctuations in heart failure, or cognitive markers in neurodegenerative conditions. Extending the model beyond diabetes will, therefore, require identification of the relevant activities and contextual indicators for each condition, as well as validation of the fuzzy interpretation rules accordingly.

Future work will also examine how adherence vectors correlate with clinical metrics such as glucose variability, HbA1c, or time-in-range. Demonstrating such relationships could reinforce the clinical relevance of the approach and inform the development of predictive or early warning models. Additionally, integration of the framework with LLM-based summarisation systems may facilitate natural-language communication of complex behavioural patterns.

6.2. Overall Contribution

The originality of this work lies in unifying explicit activities, contextual behavioural markers, and fuzzy anomaly annotation into a single, standardised methodology. By doing so, the framework advances adherence monitoring beyond traditional isolated metrics and moves toward a comprehensive, interpretable, and clinically meaningful representation of daily behaviour. The results indicate that this integrated model forms a solid foundation for future real-world deployments and for the development of intelligent decision-support tools in chronic disease management.