Abstract

The high temperatures of the spray-drying process can cause thermal inactivation of probiotic bacteria. This study evaluated the effect of chia seed mucilage (CM) on the survival and viability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) encapsulated by spray-drying in cross-linked alginate matrices (CLAM). Two types of microcapsules were used: CLAM without CM (M0-LGG) and with CM (M1-LGG). Viability was assessed under storage conditions (4 °C and 25 °C), heat treatments, and gastrointestinal simulations. The results show that LGG survival improved after spray drying in CLAM (M0-LGG), reaching levels above 92%. Microcapsules containing CM (M1-LGG) maintained high viability, exceeding 8 log CFU/g, under storage at 4 °C for 60 days. CM demonstrated the ability to preserve LGG viability during gastrointestinal digestion (above 6 log CFU/g) and to confer thermal stability under heat stress conditions at 80 °C for 5 min. This study can be a valuable reference for the food industry, as the incorporation of CM as an encapsulating agent for probiotics can improve their viability under adverse processing and storage conditions.

1. Introduction

The global probiotics sector continues to expand and is projected to reach USD 121.99 billion by 2030, highlighting the growing interest in foods and supplements containing beneficial microorganisms [1]. Probiotics are commonly defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” [2]. When incorporated into foods, these microorganisms must remain genetically and physiologically stable, tolerate processing and storage conditions, withstand physicochemical stresses imposed by the food matrix, and survive passage through the gastrointestinal tract [3,4]. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) is one of the most extensively characterized probiotic strains, particularly regarding its tolerance to thermal treatments [5,6]. For a probiotic product to be effective, a viable cell count between 106 and 107 CFU/g at the time of consumption is generally required [7]. However, the loss of viability during processing, storage, and gastrointestinal transit remains a major challenge.

Microencapsulation has emerged as an effective approach to improve probiotic survival, maintain viability over time, and protect biological activity [8]. Among the available techniques, spray drying (SD) is widely adopted in the food industry due to its scalability, low energy demand, rapid operation, and high powder recovery [9]. The resulting powders offer several practical advantages, such as extended shelf stability, ease of transport, and versatility for incorporation into different product formats. Nevertheless, SD exposes cells to simultaneous thermal and dehydration stresses that may damage the cell membrane or intracellular components, leading to substantial viability losses [10]. Strategies to mitigate this include optimizing drying conditions, selecting pre-adaptation steps, and tailoring the encapsulation matrix [8].

Sodium alginate (SA), an anionic polysaccharide composed of β-D-mannuronic (M) and α-L-guluronic (G) residues and extracted from brown algae, is widely used as an encapsulating polymer in food and pharmaceutical systems [11]. When exposed to multivalent cations such as Ca2+, SA forms ionically cross-linked hydrogels capable of mimicking the physical environment of bacterial biofilms and protecting cells under acidic conditions. Cross-linked alginate matrices (CLAM) arise from both calcium-mediated cross-linking and the formation of alginic acid when the pH is lowered, yielding structures that can shield entrapped cells from gastric acid [12]. Earlier work using alginate-based encapsulation often relied on extrusion techniques [13], which generate beads requiring an additional drying step. More recently, an in situ CLAM formation method during spray drying has been developed for the oral delivery of live microorganisms [12,14]. In this process, a suspension containing SA, a base-neutralized acid, and an insoluble calcium salt is spray dried; the base volatilizes during drying, reducing the pH, solubilizing calcium, and triggering CLAM formation inside the evaporating droplets [15]. Although Tan et al. [12] demonstrated the gastroprotective properties of this approach, potential thermoprotective effects were not examined.

Chia seed mucilage (CM) has shown promise as a protective co-encapsulating material. Previous work from our research group demonstrated that CM contributes to thermal protection during spray drying of LGG, yielding high survival (<91%) and excellent viability (>9 log CFU/g) after 45 days of refrigerated storage [16]. Chia mucilage is a high–molecular weight, water-soluble heteropolysaccharide rich in neutral sugars and uronic acids, which confer high water-binding capacity and the ability to form viscous gels [16,17]. These properties may reduce cellular dehydration, stabilize cellular structures, and enhance microcapsule integrity. Its fiber content may also contribute to additional structural stability and gelling behavior, improving encapsulation efficiency [8].

In a previous study, Bustamante et al. [16] evaluated the microencapsulation of several probiotic species—including Bifidobacterium infantis, B. longum, Lactobacillus plantarum, and LGG—using CLAM supplemented with 0.4% (w/v) CM, reporting survival values between 87% and 97%. In that work, the study aimed to further improve LGG survival by modifying specific components of the encapsulation solution. We examined the effect of increasing the concentrations of CM and CaHPO4 on LGG survival and optimized these independent variables through response surface methodology. We further assessed the protective capacity of the optimized matrix under storage, heat treatment, and simulated gastrointestinal conditions.

We hypothesized that higher CM concentrations would enhance LGG survival and viability during SD when incorporated into CLAM-based matrices. To test this, we evaluated LGG survival immediately after SD and its subsequent viability during storage, heat processing, and simulated gastrointestinal digestion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG ATCC 53103 (LGG) was from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). Chia seeds were acquired from the local market. MRS broth (BD, Baltimore, MD, USA), sodium alginate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), succinic acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), NH4OH (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and CaHPO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Extraction of CM

CM was extracted according to the method described by Bustamante et al. [18] with some modifications. Seeds were extracted with hot distilled water at 80 °C and pH 6.0 for 2 h, at a 1:40 (w/v) ratio. The extraction was repeated twice. The extract CM was spread on a tray and dried at 60 °C in an air convection oven, milled, and passed through a 0.425 mm mesh. It was then stored at −20 °C until use.

2.3. Preparation of LGG Suspension

LGG were pre-cultured twice with a 5% (v/v) inoculum in MRS broth (5 mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. For the encapsulation experiments, a 200 mL MRS culture was prepared under the same inoculation conditions and incubated for ~14 h to reach late logarithmic growth. Cells were collected by centrifugation (4100 rpm, 4 °C, 15 min), washed once with sterile distilled water, and recentrifuged. The resulting biomass was resuspended in sterile distilled water and mixed with the prepared encapsulation matrix.

2.4. Preparation of the Encapsulating Solution

The control encapsulation solution was formulated in 120 mL of distilled water, as described by Bustamante et al. [16]; 100 mL were prepared with low viscosity SA 4% (w/v) and succinic acid 2% (w/v). After sterilization (121 °C, 15 min), pH was adjusted to 5.6 ± 0.2 with NH4OH. Then, to activate the calcium alginate cross-linking, a sterile and homogeneous suspension of CaHPO4 (20 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the re-suspended probiotic biomass was added to create the control encapsulation solution. Finally, the bacterial suspensions with total viable counts between 108 and 109 CFU/mL were kept under constant stirring until they were spray-dried.

After determining the optimal concentrations of CaHPO4 and CM to maximize LGG survival, two types of microcapsules were prepared: M0-LGG (control), without CM (0% w/v), with 0.6% w/v CaHPO4, 4% w/v SA and 2% w/v succinic acid; and M1-LGG, supplemented with CM (0.6% w/v), maintaining the same proportions of CaHPO4, SA and succinic acid.

2.5. Evaluation of LGG Survival After Spray Drying Process

2.5.1. Encapsulation Process by Spray Drying

For the spray drying process, a laboratory spray dryer unit (Büchi B290, Flawil, Switzerland) was used. The process parameters were set as follows: inlet temperature = 130 °C; feed flow rate = 6 mL/min; air flow rate = 45 m3/h; outlet temperature = 72–75 °C. These conditions remained the same and unchanging throughout all experimental trials, as the aim was to improve the encapsulation solution.

An experimental design, based on Response Surface Methodology (RSM), was used to optimize the encapsulating solution for LGG survival. Two independent variables were considered: concentration of CM (%, w/v) and CaHPO4 (%, w/v). The optimal concentrations of these components were determined using a central composite design with a face-centered approach. Each variable had three working levels, with three replicates at the center point; thus, a total of 11 experiments were conducted to build response surface models. The response evaluated was the survival (%) of LGG after the SD microencapsulation process. Design-Expert v.6.0 software was used to fit the experimental data to polynomial model equations.

2.5.2. Membrane Integrity and LGG Growth Capacity

The “cell sorting” method with specific markers was used to distinguish viable from non-viable cells after spray drying encapsulation, with the aim of evaluating the protective effect of CM on LGG against thermal damage. Samples were analyzed using a Flow Cytometer Cell Sorter (FCCS) with Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS ARIA Fusion, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). BD FACS DIVA software, version 8.0.2 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was used for data analysis. Two samples were processed: the LGG were encapsulated through a spray drying process in CLAM with CM (M1-LGG) and without CM (M0-LGG); they were then re-suspended in sterile Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) at a concentration of 106–107 cells/mL. For staining, 1 mL of sample was incubated with SYBR Green (1:10,000) and PI (2 µg/mL). Total cell counts were determined by applying gating based on a bivariate dot plot. The position of the control population of dead cells was used to set gates that separate membrane-compromised cells from intact cells. These gates were applied in the dot plot PE-A (for non-viable cells) vs. FITC-A (for viable cells), both plots set to log scale. Blank controls (filtered PBS) were analyzed at the start of each assay to determine and subtract background noise events. The number of viable cells in the product was expressed as the number of events.

The LGG growth curve was measured (M0-LGG and M1-LGG). The spray-dried samples were added to a sterilized MRS liquid medium, and bacterial growth was monitored for 24 h. The optical density value (OD 600) was measured every 2 h (Genesys 10S, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.6. Characterization of the Physicochemical Properties of LGG Microcapsules

2.6.1. Morphology of Spray Dried Microcapsules

The outer structure of dried particles will be examined using a Scanning Electron Microscope, SEM SU3500 (Hitachi, Japan). For SEM imaging, parameters such as an accelerating voltage (20 kV), a sample-to-objective distance (6.6 mm), a magnification of ×2.5 k, the 3D backscattered electron mode (BSE-3D), and a chamber pressure of 30 Pa will be set. The sample will be dispersed on the sample holder equipped with double-sided carbon tape.

2.6.2. Moisture and Water Activity

The moisture content of the microcapsules was determined gravimetrically by oven-drying at 102 °C until a constant weight was reached. Water activity will be measured using a Decagon Devices Pawkit water activity meter (Pullman, WA, USA). The dried particles will be measured at 25 °C after the spray drying process. The assay will be performed in duplicate.

2.6.3. Determination of Functional Groups Present in Microcapsules by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The identification of functional groups in the microcapsules was performed using FTIR with the Bruker Vector 22 (Bruker Optics GmbH, Inc., Ettlingen, Germany), covering a frequency range of 5000–250 cm−1, with KBr pellets as the matrix. The samples were analyzed in transmittance mode to detect specific functional groups.

2.6.4. Analysis of Thermal Behaviour of Microcapsules

The thermal behaviour of microcapsules was comprehensively analyzed using a Thermogravimetric Analyzer TGA-DSC STA 6000 (PerkinElmer Co., Waltham, MA, USA) to obtain thermograms under a nitrogen atmosphere (40 mL/min). A 20 mg sample was used for each test experiment.

2.7. Evaluation of LGG Viability Under Storage Conditions

This analysis aims to evaluate the stability of LGG microcapsules during storage. The viability of the encapsulated LGG will be assessed during storage at 4 °C and 25 °C over a period of 60 days. The test will be performed in duplicate.

2.8. Evaluation of LGG Viability Under Heat Treatment Conditions

The heat tolerance of LGG will be evaluated according to Malmo et al. [19] with some modifications. The viability was tested against several time-temperature combinations: 40 °C for 5 min, 50 °C for 5 min, 60 °C for 3 min, 70 °C for 3 min, and 80 °C for 2- and 5-min. Microcapsules (0.1 g) were suspended in 4.9 mL of MRS broth contained in a glass tube. Samples were placed in a temperature-controlled dry bath under the conditions mentioned above. Once the incubation time was complete, the glass tubes were rapidly cooled. A viable cell count was determined from samples taken immediately after mixing and at the end of the incubation period. The assay was performed in duplicate.

2.9. Evaluation of the Viability of LGG Under In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion Conditions

To simulate gastrointestinal tract digestion, the INFOGEST protocol proposed by Brodkorb et al. [20] was used. Briefly, the oral phase was prepared by mixing 1 g of the powder sample with 1 mL of simulated salivary fluid (SSF). The final pH of the oral phase was adjusted to 7.0, and the mixture was shaken at 15 rpm at 37 °C for 2 min. Next, the gastric phase was created by adding 4 mL of simulated gastric fluid (SGF) to the oral phase, and the pH was adjusted to 3.0 using the appropriate volume of 1 M HCl. The sample was then stirred at 15 rpm for 2 h at 37 °C. Finally, the intestinal phase involved combining the gastric phase with 8 mL of simulated intestinal fluid (SIF), bile extract (10 mM), and pancreatin (100 U/mL). The final pH was adjusted to 7.0 with the required amount of 1 M NaOH or HCl, and the mixture was incubated under the same conditions as the gastric phase. After each phase, a viability assay was performed as described in Section 2.10.

2.10. Analytical Methodology

Standard plate colony count determined the survival and viability of LGG after drying. Briefly, the sample (0.1 g) was diluted in 4.9 mL of sterile 0.1% (w/v) buffered peptone water. Suitable dilutions of the suspension were seeded on MRS agar and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The percent survival after drying was calculated using the equation proposed by Simpson et al. [21]:

where N is the log CFU/g of the powder immediately after drying, and N0 is the log CFU/g of the dry matter in the suspension fed into the spray dryer.

2.11. Statical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Design Expert 6.0 statistical software (Stat-Ease, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the significance of the effects (p < 0.05). Differences between means were detected using Tukey’s test (p < 0.05) (GraphPad Prism 10.4.0).

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of LGG Survival After Spray Drying Process

3.1.1. Spray-Dried LGG Survival

The influence of the encapsulation components on LGG performance after spray drying was investigated using a face-centered response surface methodology (RSM) design implemented in Design-Expert 6.0. This statistical framework facilitated the estimation of optimal factor levels, the identification of interactions, and the evaluation of the main effects of CaHPO4 (X1) and CM (X2) on LGG survival percentage. The design consisted of 11 experimental trials, three of which were replicates at the center point to ensure model reliability. Table 1 summarizes the experimental layout, the measured survival values, and the RSM-predicted responses derived from the fitted model. The survival behavior of LGG was described using a linear model fitted to the experimental data:

Y = 88.02 + 0.73X1 + 2.54X2

Table 1.

Experimental matrix. LGG survival after spray drying and response given by the model derived from the experimental data.

The ANOVA results confirmed that the regression model was significant (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The model F value (10.328) indicated a meaningful linear association between the response variable and the evaluated factors. The model performance parameters showed an acceptable fit, with R2 = 0.721, adjusted R2 = 0.651, and Adeq Precision = 8.73 (Table 3), the latter exceeding the recommended minimum for reliable predictive ability. Overall, the model was statistically significant (p = 0.006). Among the factors, only X2 exhibited a significant influence on LGG survival (p = 0.002), whereas X1 was not significant (p = 0.244). Nevertheless, X1 was retained to preserve the structure of the experimental design and ensure the internal consistency of the model (Table 2).

Table 2.

ANOVA summary for the overall effects of chia seed mucilage (CM) and calcium phosphate (CaHPO4) concentrations in the encapsulating solution on LGG survival after spray drying.

Table 3.

Statistical indicators correspond to the regression model for the survival response after encapsulation by spray drying at 130 °C.

The lack-of-fit test was significant (p = 0.018), suggesting that the linear model does not fully capture all sources of variability inherent to the biological system. Despite this, other diagnostic indicators, including the coefficient of variation (CV < 10%) and the signal-to-noise ratio (>4), were within acceptable ranges for response surface modeling (Table 3). Thus, the model remains valid for describing the primary trends within the tested experimental region.

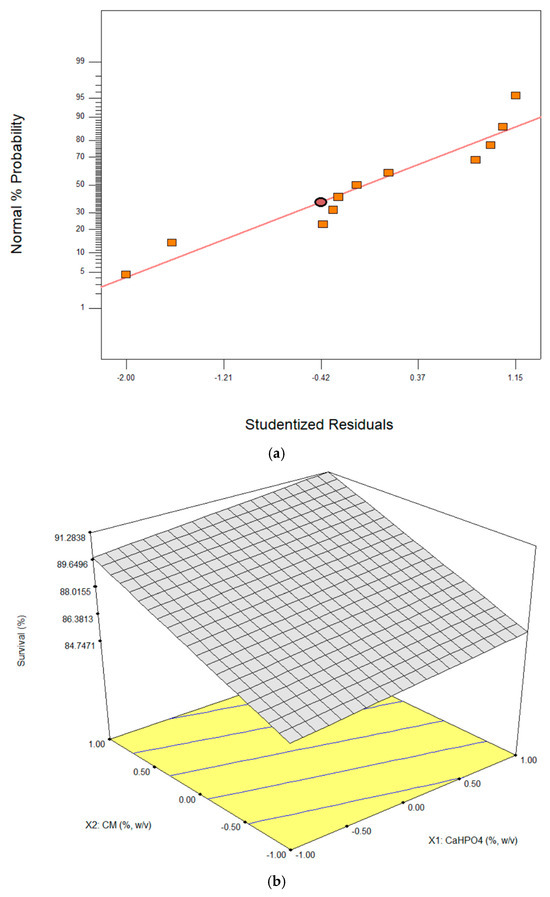

Inspection of the studentized residuals showed values ranging approximately from −2.00 to 1.15, with no evidence of extreme deviations and with relatively uniform dispersion (Figure 1a). This pattern supports that the assumptions of constant variance and independence were reasonably met. Although the lack of fit was significant, the linear model offers a practical and statistically sound representation of the main effects of the variables on LGG survival during spray drying.

Figure 1.

Linear regression model. (a) Normal plot of residuals, (b) 3D graph corresponding to the RSM for the survival of LGG after the spray drying process. Where, X1: CaHPO4 (%, w/v) and X2: CM (%, w/v).

Figure 1b shows that there is no significant interaction between CM and CaHPO4 concentrations, as indicated by the contour lines, which remain linear rather than oval. This pattern confirms the absence of a synergistic region and suggests that both factors act independently without mutual influence. Nevertheless, LGG survival increased progressively as CM and CaHPO4 concentrations rose from 0 to 0.6% (w/v) and 0.2 to 0.6% (w/v), respectively, highlighting the protective contribution of each component. The linear regression model was therefore suitable for determining the optimal conditions, achieving a maximum survival rate of 90.56% at X2: CM (0.6%, w/v). This outcome indicates that CM exerts a dominant effect compared to CaHPO4, likely due to its higher viscosity and ability to form hydrogen-bond networks that stabilize the microcapsule matrix [16]. Consequently, the regression analysis not only identifies optimal concentration but also reinforces the mechanistic role of CM in enhancing probiotic resilience under stress conditions.

3.1.2. Membrane Integrity and LGG Growth Capacity

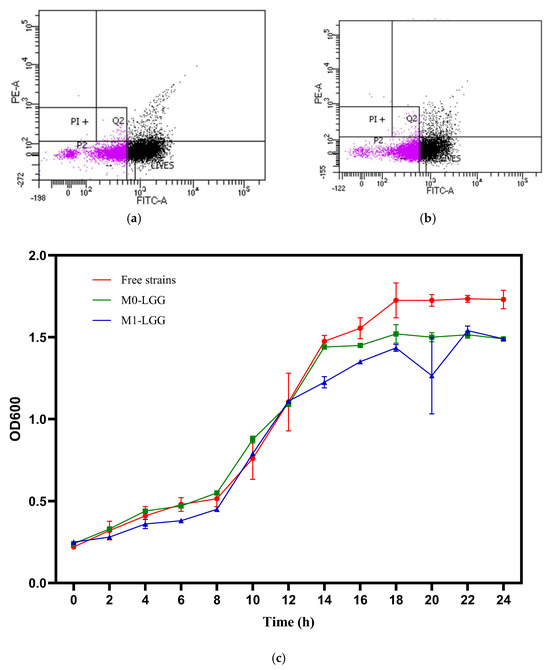

FCCS was applied to assess the viability of LGG entrapped in M0-LGG and M1-LGG microcapsules. SYBR Green–positive cells were detected in the FITC channel, whereas PI-stained cells were recorded in the PE channel. The analysis revealed a markedly higher proportion of viable cells in the M1-LGG formulation. In the P2 subpopulation (Figure 2), viable cells accounted for 87.61% in M1-LGG and 53.57% in M0-LGG. The Q2 quadrant, corresponding to double-stained cells, reached 15.19% in M1-LGG and 9.54% in M0-LGG, reflecting a population of sublethally injured cells likely associated with drying-induced stress [6].

Figure 2.

FCCS density plots (a) M1-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM with CM, (b) M0-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM without CM, (c) LGG growth curves.

To further examine cell integrity, the growth capacity of LGG recovered from both microcapsules was evaluated. As shown in Figure 2c, microencapsulated LGG displayed typical growth kinetics, including lag, exponential, and stationary phases [5]. Moreover, growth behavior closely matched that of free LGG, with no detectable delays following microencapsulation [22].

3.2. Physical Properties of Dry LGG Microcapsules

3.2.1. Survival of LGG in Optimal Conditions

Table 4 shows that there are significant differences (p < 0.05) in the survival of encapsulated LGG with CM (M1-LGG) compared to that without CM (M0-LGG).

Table 4.

Survival of LGG after encapsulation by spray-drying at 130 °C.

3.2.2. Moisture and Water Activity

The water activity and moisture content of microparticles M1-LGG and M0-LGG showed significant differences (p < 0.05), with values ranging from 0.51 to 0.24 and 6.54 to 7.89 %, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Water activity and moisture content properties of LGG after encapsulation by spray-drying at 130 °C.

For powdered probiotic formulations, maintaining water activity below 0.50 is generally recommended to ensure physicochemical stability and prevent microbial deterioration [23]. In the present study, the moisture content of the microcapsules remained close to 7%, a range considered optimal for preserving the stability and shelf life of spray-dried LGG powders [23]. Moisture levels and water activity are strongly influenced by the inlet and outlet air temperatures during drying, which directly affect both powder stability and the viability of the entrapped cells.

Comparable observations were reported by Barajas-Álvarez et al. [24], who spray-dried L. rhamnosus HN001 using different wall materials (outlet temperature 60 ± 1 °C) and obtained moisture values between 5.93% and 7.41%, consistent with those of the current study. Although low moisture and water activity favor product stability, values that are excessively low may be detrimental. When powders reach moisture levels <2% and water activity <0.10, damage to cellular structures—including membrane disruption—may occur, leading to reduced metabolic activity and diminished LGG viability [24].

3.2.3. Morphology of Spray-Dried Microcapsules

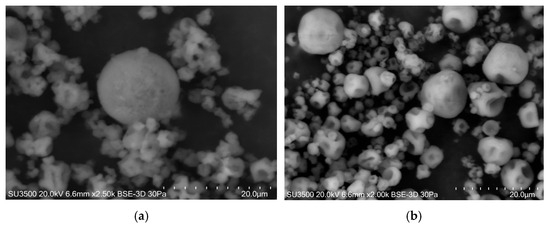

Figure 3 shows the SEM micrographs of the powder particles obtained in the encapsulation process of the LGG strain by the SD process in CLAM: M1-LGG (Figure 3a) and M0-LGG (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of spray-dried microcapsules for LGG (a) M1-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM with CM, (b) M0-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM without CM.

The microcapsules showed the characteristic concave morphology associated with spray drying, a feature generally attributed to particle shrinkage during rapid solvent evaporation [8]. In formulations containing CM (M1-LGG), the particles appeared predominantly spherical and exhibited a higher degree of aggregation compared with the CLAM-only microcapsules (M0-LGG) (Figure 3b). This aggregation is consistent with the greater stickiness expected from materials with a low glass transition temperature, such as CM [25].

No entrapped cells were visible on the particle surfaces, indicating that the cells were efficiently embedded within the matrix. Both formulations displayed smooth outer walls without cracks or surface disruptions, a feature essential for maintaining structural integrity and reducing gas permeability. Notably, M1-LGG particles (Figure 3a) presented a more compact and uniform surface, which may contribute to enhanced physical protection of the encapsulated LGG cells [26].

3.2.4. Determination of Functional Groups Present in Microcapsules by FT-IR

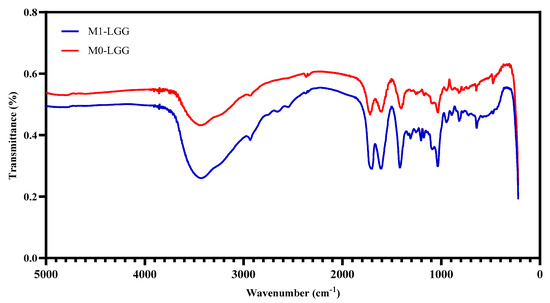

The FTIR spectra of the functional groups are shown in Figure 4. The presence of carboxyl group (-COO−) bands was observed in both microcapsules, indicating the formation of CLAM. When an ionic bond is formed with Ca2+, these carboxyl groups (-COO−) bands shift or change in intensity, indicating interaction with the metal ion. The peaks observed at 1600 and 1400 cm−1 correspond to asymmetric and symmetric stretching, respectively. [16]. The 3484 cm−1 band corresponds to the vibration of bonds in the OH functional groups. The following bands mainly relate to stretching: 2945 cm−1 (CH), 1766 cm−1 (C-O acetyl carbonyls), 1504 cm−1 (CH3 and COO), 1064 cm−1 (C-O-C ether in sugars) [27]. The presence of weak bands near 2700–2800 cm−1, caused by C–H stretching of aldehydes or methyl groups in the spray-dried M1-LGG sample, may suggest molecular interactions between CM and SA [28].

Figure 4.

FTIR of spray-dried microcapsules with LGG: (Blue line) M1-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM with CM; and (Red line) M0-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM without CM.

The M1-LGG spectrum exhibited the vibrational profile characteristic of polysaccharide-based matrices, with a broad set of signals extending across the 3600–1200 cm−1 region. The upper band in this interval reflects the extensive hydrogen-bonding network generated by the hydroxyl-rich structure of CM, a heteropolysaccharide containing numerous –OH groups and comparatively few carboxyl moieties [29]. A distinct feature was also observed near 2931 cm−1, corresponding to aliphatic C–H stretching vibrations. The absorption detected around 1600 cm−1, typically associated with amide-related C=O vibrations, indicates the presence of minor protein fractions in CM; accordingly, this signal was absent in the M0-LGG formulation [30]. The peak observed near 1600 cm−1 corresponds to the amide I band for C=O stretching and indicates the presence of protein portions in galactomannan [29]. In contrast, the band located near 1373 cm−1—attributed to C–N or related deformation modes—was present in both types of microcapsules [30]. Notably, both spectra included a peak in the vicinity of 1700 cm−1. This absorption is consistent with electrostatic interactions between carboxyl-containing groups within the polymeric matrix and divalent Ca2+ ions, supporting the formation of calcium-mediated associations in the encapsulated structures [31].

3.2.5. Analysis of Thermal Behaviour of Microcapsules

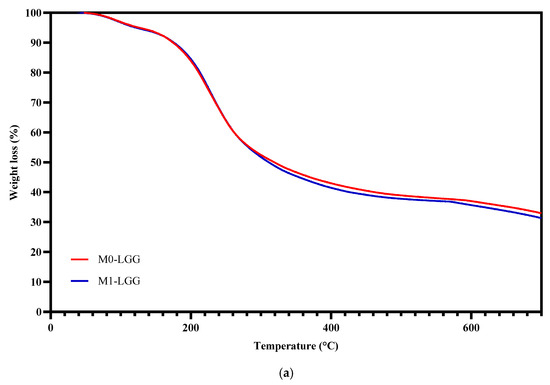

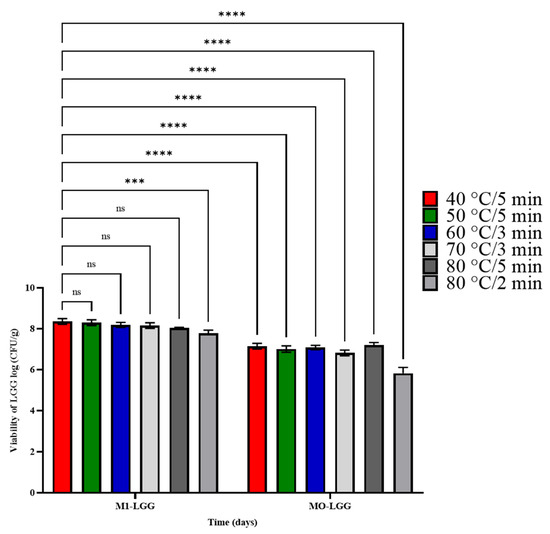

Figure 5 displays the thermogravimetric (TGA) and derived thermogravimetric (DTGA) curves obtained from spray-dried powders, M0-LGG and M1-LGG.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the thermal behaviour of microcapsules. (a) TGA and (b) DTGA. (Blue line) M1-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM with CM; and (Red line) M0-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM without CM.

The thermogravimetric analysis revealed three sequential mass-loss stages. The first event, occurring between 25 °C and 170 °C, corresponded to the release of moisture retained in the microcapsules. The second stage, extending from 170 °C to 320 °C, reflected the degradation of the polysaccharide matrix, including thermal cleavage of saccharide chains and decomposition of their structural fractions [28]. The general resemblance of the TGA/DTGA curves for both microcapsules is explained by their polysaccharide-rich composition, which drives comparable thermal events—dehydration, chain breakdown, and carbonization. Although CM contributes to modifications in microstructure and functional stability, it does not substantially alter the intrinsic degradation profile, resulting in curves that are similar but differ subtly in intensity and final residue [30].

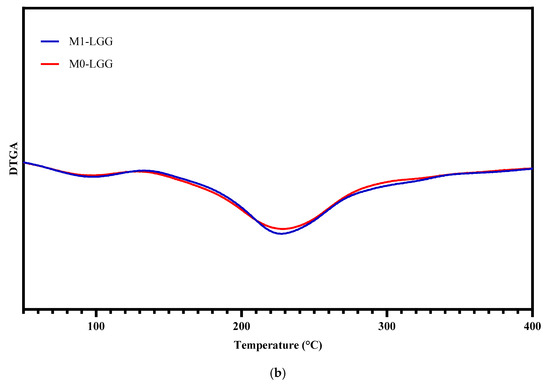

3.3. Evaluation of LGG Viability Under Storage Conditions

The microcapsules were tested for LGG viability under different storage conditions: refrigeration (4 °C) and room temperature (25 °C), at 0, 7, 15, 30, 45, and 60 days. The storage stability of encapsulated LGG in the two microcapsule types (M0-LGG and M1-LGG) is shown in Figure 6. Microcapsules stored at 4 °C maintained LGG viability for 60 days (Figure 6a), with counts above 6 log CFU/g. The M0-LGG and M1-LGG microcapsules differed significantly (p < 0.05), with 8.35 and 6.25 log CFU/g, respectively.

Figure 6.

Viability of LGG under storage conditions: (a) 4 °C and (b) 25 °C. (▲) M1-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM with CM; and (■) M0-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM without CM. Means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Microcapsules stored at 25 °C (Figure 6b) exhibit a significant decline in cell viability over the storage period. After the 15th day, the evaluated microcapsules had cell viability below 6 log CFU/g, falling short of the minimum viable concentration needed for probiotics to provide a therapeutic effect [7]. This result aligns with that of Reyes et al. [32], who evaluated the viability of Lactobacillus acidophilus microencapsulated with a high content of corn starch, maltodextrin, and gum arabic by spray dryer under different storage conditions for 60 days. They found that microparticles stored at 23 °C showed reduced probiotic viability after the 20th day, with counts < 6 log CFU.

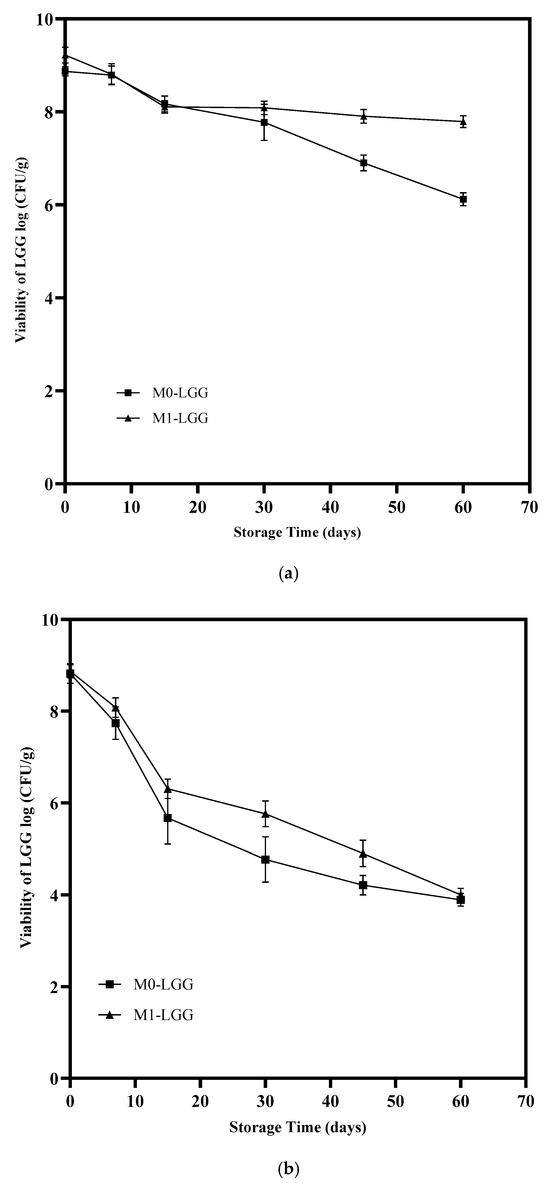

3.4. Evaluation of LGG Viability Under Heat Treatment Conditions

We evaluated whether microcapsules containing LGG could withstand the processing conditions of foods that typically do not contain probiotics, exploring potential commercial applications, such as incorporation into puddings or soufflés. Although these products are processed at high temperatures (180–250 °C), the core reaches between 50 °C and 95 °C for 2–5 min, depending on their composition. In this context, LGG viability was evaluated under different heat conditions, using a combination of six treatments (40 °C for 5 min, 50 °C for 5 min, 60 °C for 3 min, 70 °C for 3 min, 80 °C for 2 min, and 80 °C for 5 min) (Figure 7). This approach simulated the thermal exposure that the bacteria might experience during the processing of various food products.

Figure 7.

Viability of LGG strain under heat treatment conditions. M1-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM with CM; M0-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM without CM. Statistical comparison was performed using a multiple comparison test (ns: non-significant; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001). Means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed between M0-LGG and M1-LGG, mainly in the treatment at 80 °C for 5 min, where the viability of M0-LGG dropped below the minimum effective concentration (6 log CFU). Heat processing can easily degrade the ordered structures of proteins and nucleic acids in free cells and break the bonds between monomeric units [33]. However, after the spray drying process, lactic acid bacteria, due to heat stress, can develop heat tolerance [6].

3.5. Evaluation of Viability of LGG Under In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion Conditions

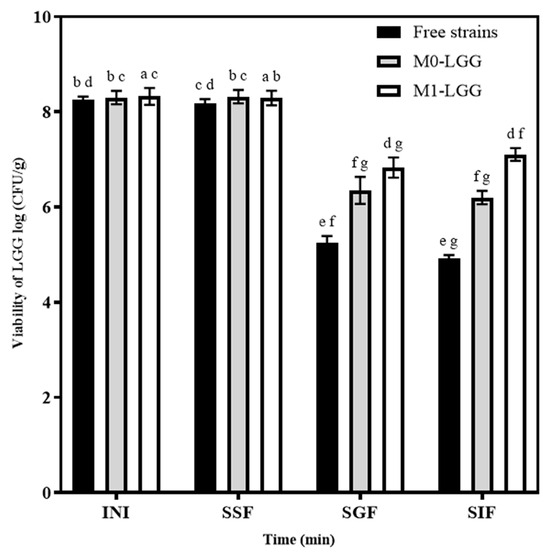

Cell release and viability of LGG were demonstrated through in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Both microcapsules were exposed to simulated fluids—SSF, SGF, and SIF—and compared with free strains (control) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Viability and stability of LGG under in vitro gastrointestinal digestion conditions. M1-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM with CM; and M0-LGG: LGG encapsulated in CLAM without CM. Different superscript letters in the same line indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between the microcapsules of LGG. INI: Concentration Inicial, SSF: Simulated Salivary Fluid, SGF: Simulated Gastric Fluid, SIF: Simulated Intestinal Fluid. Means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

SSF showed no significant differences (p < 0.05) between free cells and M0-LGG and M1-LGG microcapsules, as the exposure time in this phase is too short (2 min). In SGF, with 2 h of exposure in the simulated fluid, there was a significant difference (p < 0.05) between M0-LGG and M1-LGG microparticles compared to free cells, with reductions of less than 6 log CFU, while the microcapsules reduced 1.83 and 1.68 log CFU, respectively. These results are relevant, given that the conditions involved a pH of 3 and the enzymatic action of pepsin [20]. Compared with M1-LGG, the resistance to these conditions was slightly higher in M0-LGG. This evidence suggests that both materials, both CLAM and CM, can protect the conditions afforded by the stomach, allowing controlled release of LGG [11].

LGG was released gradually until it reached the intestinal phase, where optimal conditions for complete release occur, with a pH around 7.0 to 8.0 [34]. SIF (2 h exposure) was essential to maintain LGG viability, as the microorganism must reach this phase in sufficient quantities to achieve a therapeutic effect, i.e., with cell counts > 6 log CFU/g [2].

4. Discussion

This study aimed to improve the survival of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) during spray drying by modifying the encapsulation matrix composition. Previous formulations containing CM (0.4% w/v) and CaHPO4 (0.5% w/v) achieved survival rates of ~88% under constant drying conditions [16]. Here, increasing both CM and CaHPO4 concentrations to 0.6% resulted in a survival rate of 92.21% (M1-LGG), highlighting the mechanistic contribution of each component.

CM is a hydrophilic heteropolysaccharide with high water-binding capacity. Its presence increases solution viscosity, which reduces droplet porosity during atomization [16]. This denser matrix slows water diffusion and evaporation, thereby minimizing dehydration-induced damage to bacterial membranes. Moreover, FTIR spectra revealed broad absorptions between 3500–3200 cm−1, consistent with hydroxyl and amino groups capable of hydrogen bonding [28]. These interactions likely stabilize proteins and ribosomal structures on the bacterial surface, reducing thermal denaturation during convective drying. FCCS confirmed this protective effect, with M1-LGG showing 87.61% viable cells compared to lower values in M0-LGG [6].

Higher CaHPO4 concentrations promoted extensive ionic cross-linking of SA, forming compact CLAM networks. The electrostatic interactions between Ca2+ and deprotonated polyuronates were facilitated by droplet acidification during drying, buffered by succinic acid (pKa ≈ 4.2) [31]. This mechanism ensured that alginate chains remained negatively charged and available for binding, reinforcing the gel structure. The resulting microcapsules exhibited reduced permeability and enhanced mechanical stability, which limited proton diffusion and protected LGG under simulated gastric conditions.

The synergy between CM and SA increased viscosity and reduced matrix porosity, creating a physical barrier against heat transfer and oxidative stress. SEM micrographs supported this interpretation: M1-LGG particles were larger and more textured, consistent with higher solids content and denser encapsulation. This morphology also facilitated more efficient water removal, yielding powders with lower residual moisture. Maintaining residual moisture within 5–10% (aw < 0.6) is critical to prevent microbial growth, hydrolysis, and caking, while avoiding excessively low values that compromise powder reconstitution [24]. Our results align with previous reports that moisture levels below 6% extend probiotic powder stability.

The optimized formulation outperformed other mucilage–alginate systems. For example, encapsulation of Lactobacillus acidophilus with CM (0.6% w/v) yielded ~75% survival [35], while basil seed mucilage systems reported ~62% [36]. These differences emphasize that the mechanistic protection depends not only on the presence of mucilage but also on its molecular composition and interaction with alginate. Related studies have shown that additives such as sucrose mitigate the adverse effects of divalent cations in alginate matrices, reinforcing the importance of tailoring matrix composition to maximize probiotic survival [37].

LGG viability decreased markedly at ambient temperature after 15 days, reflecting the intrinsic sensitivity of this strain to prolonged exposure. The control formulation (M0-LGG) was more vulnerable, whereas CM-supplemented powders (M1-LGG) exhibited greater resilience. This effect can be mechanistically attributed to the complex sugar composition of CM (xylose, galactose, arabinose, glucose, galacturonic, and glucuronic acids), which confers high viscosity and water-binding capacity [16,38]. The decomposition profile of CM (≈320 °C) indicates that its structural integrity persists under moderate storage conditions, delaying matrix collapse and protecting entrapped cells.

No significant differences were observed among M1-LGG samples subjected to different heating regimes, suggesting that CM confers thermoprotection independent of exposure time or temperature. Mechanistically, this effect is linked to uronic acids present in both CM and SA, which form non-covalent bridges with proteins and polysaccharides [39]. These interactions stabilize the microcapsule matrix by hydrogen bonding and electrostatic forces. FTIR spectra support this mechanism: shifts in O–H stretching (3200–3600 cm−1) and COO− bands (~1600 and ~1400 cm−1) indicate hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions with positively charged proteins [28]. Such stabilization reduces protein denaturation and delays heat-induced membrane damage. Literature comparisons reinforce this mechanism: protein-based coatings (e.g., SPI, WPI) [22] and bi-layer alginate systems also enhance thermal tolerance by increasing matrix density and reducing water diffusion [26]. In our case, CM likely acts as a physical barrier, slowing heat transfer and delaying direct exposure of LGG to thermal stress.

The thermal profiles of M0-LGG and M1-LGG were similar, dominated by the decomposition stages of sodium alginate: moisture loss (25–170 °C), polysaccharide degradation (170–320 °C), and carbonaceous residue formation (>320 °C). CM, rich in hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, exhibited overlapping degradation behavior (280–360 °C), consistent with previous reports [30,38]. The addition of CM did not alter the fundamental decomposition stages but introduced subtle differences in residual mass, reflecting its role as a barrier rather than a primary structural modifier. Ionic interactions between carboxyl groups and Ca2+ stabilize the CLAM network, while CM contributes additional protection without changing the dominant thermal pathway.

Both microcapsules released LGG effectively in the intestinal phase, outperforming free cells. Alginate’s mechanism of protection involves proton capture and conversion into insoluble alginic acid, buffering gastric pH, and shielding entrapped cells [12,40]. The addition of CM further enhanced viability, as indicated by FTIR spectra showing strong O–H and N–H absorptions (3500–3200 cm−1). Mechanistically, CM-SA complexes delay water penetration and reduce premature release in acidic gastric conditions, while enabling gradual release in the intestine [41]. CM may also provide partial buffering capacity and sequester bile salts, mitigating their inhibitory effects on cell membranes. The galacturonic acid component (pKa ≈ 3.5–4.5) suggests that CM behaves as a weak polyelectrolyte, capable of ionizing under acidic conditions and interacting with cations such as Ca2+ [42]. This property could contribute to gel stability and controlled release. Future mechanistic studies using Raman spectroscopy [43] and NMR [44] could clarify ionic interactions and water distribution within CM-SA matrices, providing deeper insight into the protective role of CM during gastrointestinal transit.

This study focused on a single strain of LGG, so future research should evaluate other probiotic species and develop specific experimental designs for the encapsulation materials used. Additionally, future studies should include in vitro testing of these microcapsules using cell lines. Like previous research, this study also highlights the challenges faced during the gastric phase regarding the viability of encapsulated probiotics. Therefore, future studies should consider modifying the culture medium by adding a compound that provides pH buffering before the SD process of LGG. Additionally, co-encapsulation of LGG with a compound that can neutralize issues related to acidic pH and enzymatic activity should be investigated.

5. Conclusions

The results of this research show that the addition of CM and a higher concentration of CaHPO4 improved the survival rate of LGG after the spray drying process in CLAM.

Our results demonstrated that the interactions between the components of the encapsulation matrix and CM produced a probiotic powder with suitable physicochemical properties, including water activity and moisture content, which support the viability of LGG during 60 days of storage at 4 °C. The addition of CM as a supplement (M1-LGG) enhanced thermal stability and resistance to in vitro gastrointestinal conditions compared to the control microcapsules (M0-LGG). These findings can serve as a reference for the food industry, as incorporating chia seed mucilage as an encapsulating agent for probiotic cells via spray drying offers a strategy to overcome challenges related to probiotic viability during food processing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B. and M.B.; methodology, V.B.; software, V.B.; validation, V.B., O.R. and M.B.; formal analysis, V.B.; investigation, V.B.; resources, M.B. and C.S.; data curation, V.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B.; visualization, O.R.; supervision, M.B.; project administration, M.B.; funding acquisition, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by ANID (Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo, Chile) for their support through FONDECYT-REGULAR project No. 1211211, Doctoral Grant folio N°21212055, Project ANID/FONDAP/15130015 and ANID/FONDAP/1523A0001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge ANID for their support through FONDECYT-REGULAR project No. 1211211, Doctoral Grant folio N°21212055, Project ANID/FONDAP/15130015 and ANID/FONDAP/1523A0001. We also extended our gratitude to the BIOREN-UFRO for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mordor Intelligence. Probiotics Market Size—Industry Report on Share, Growth Trends & Forecasts Analysis (2025–2030). 2024. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/probiotics-market (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- FAO. Probiotics in food Health and nutritional properties and guidelines for evaluation. In Proceedings of the Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food, London, ON, Canada, 30 April–1 May 2002; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Samedi, L.; Charles, A.L. Isolation and Characterization of Potential Probiotic Lactobacilli from Leaves of Food Plants for Possible Additives in Pellet Feeding. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2019, 64, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.K.; Giri, S.K. Probiotic Functional Foods: Survival of Probiotics during Processing and Storage. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 9, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.Y.; Geng, W.; Peterson, B.W.; Van Der Mei, H.C.; Busscher, H.J. Escherichia Coli Colonization of Intestinal Epithelial Layers in vitro in the Presence of Encapsulated Bifidobacterium breve for Its Protection against Gastrointestinal Fluids and Antibiotics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 15973–15982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, M.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, F.; Saqib, M.N.; Chiou, B.S.; Zhong, F. The Dual Effect of Shellac on Survival of Spray-Dried Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Microcapsules. Food Chem. 2022, 389, 132999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahire, J.J.; Rohilla, A.; Kumar, V.; Tiwari, A. Quality Management of Probiotics: Ensuring Safety and Maximizing Health Benefits. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Laurie-Martínez, L.; Vergara, D.; Campos-Vega, R.; Rubilar, M.; Shene, C. Effect of Three Polysaccharides (Inulin, and Mucilage from Chia and Flax Seeds) on the Survival of Probiotic Bacteria Encapsulated by Spray Drying. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgain, J.; Gaiani, C.; Linder, M.; Scher, J. Encapsulation of Probiotic Living Cells: From Laboratory Scale to Industrial Applications. J. Food Eng. 2011, 104, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anal, A.K.; Singh, H. Recent Advances in Microencapsulation of Probiotics for Industrial Applications and Targeted Delivery. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.; Janfaza, S.; Tasnim, N.; Gibson, D.L.; Hoorfar, M. Microencapsulating Polymers for Probiotics Delivery Systems: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.L.; Mahotra, M.; Chan, S.Y.; Loo, S.C.J. In Situ Alginate Crosslinking during Spray-Drying of Lactobacilli Probiotics Promotes Gastrointestinal-Targeted Delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 286, 119279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Shao, L.; Chen, D.; Wang, J. Extending Viability of Bifidobacterium longum in Chitosan-Coated Alginate Microcapsules Using Emulsification and Internal Gelation Encapsulation Technology. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, S.A.; Hudnall, K.; Arbaugh, B.; Cunniffe, J.C.; Scher, H.B.; Jeoh, T. Stability of Fish Oil in Calcium Alginate Microcapsules Cross-Linked by in situ Internal Gelation During Spray Drying. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, S.A.; Scher, H.B.; Nitin, N.; Jeoh, T. In Situ Cross-Linking of Alginate during Spray-Drying to Microencapsulate Lipids in Powder. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 58, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Oomah, B.D.; Burgos-Díaz, C.; Vergara, D.; Flores, L.; Shene, C. Viability of Microencapsulated Probiotics in Cross-Linked Alginate Matrices and Chia Seed or Flaxseed Mucilage During Spray-Drying and Storage. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, E.O.; Oludipe, E.O.; Gebremeskal, Y.H.; Nadtochii, L.A.; Baranenko, D. Evaluation of Extraction Techniques for Chia Seed Mucilage; A Review on the Structural Composition, Physicochemical Properties and Applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 153, 110051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Villarroel, M.; Rubilar, M.; Shene, C. Lactobacillus acidophilus La-05 Encapsulated by Spray Drying: Effect of Mucilage and Protein from Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmo, C.; Giordano, I.; Mauriello, G. Effect of Microencapsulation on Survival at Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions and Heat Treatment of a Non Probiotic Strain, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 48m, and the Probiotic Strain Limosilactobacillus reuteri Dsm 17938. Foods 2021, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static in vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, P.J.; Stanton, C.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P. Intrinsic Tolerance of Bifidobacterium Species to Heat and Oxygen and Survival Following Spray Drying and Storage. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Xu, Y.; Dong, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H. The Effects of Microcapsules with Different Protein Matrixes on the Viability of Probiotics during Spray Drying, Gastrointestinal Digestion, Thermal Treatment, and Storage. eFood 2023, 4, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysan, U.; Elmas, F.; Koç, M. The Effect of Spray Drying Conditions on Physicochemical Properties of Encapsulated Propolis Powder. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Álvarez, P.; González-Ávila, M.; Espinosa-Andrews, H. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 by Spray Drying and Its Evaluation under Gastrointestinal and Storage Conditions. LWT 2022, 153, 112485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukoulis, C.; Cambier, S.; Serchi, T.; Tsevdou, M.; Gaiani, C.; Ferrer, P.; Taoukis, P.S.; Hoffmann, L. Rheological and Structural Characterisation of Whey Protein Acid Gels Co-Structured with Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) or Flax Seed (Linum usitatissimum L.) Mucilage. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 89, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, S.A.; Akhter, R.; Masoodi, F.A.; Gani, A.; Wani, S.M. Effect of Double Alginate Microencapsulation on in vitro Digestibility and Thermal Tolerance of Lactobacillus plantarum NCDC201 and L. casei NCDC297. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 83, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.H.; Neves, I.C.O.; Oliveira, N.L.; de Oliveira, A.C.F.; Lago, A.M.T.; de Oliveira Giarola, T.M.; de Resende, J.V. Extraction Processes and Characterization of the Mucilage Obtained from Green Fruits of Pereskia Aculeata Miller. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceja-Medina, L.I.; Ortiz-Basurto, R.I.; Medina-Torres, L.; Calderas, F.; Bernad-Bernad, M.J.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A.; Calderón-Santoyo, M.; González-ávila, M.; Andrade-González, I.; et al. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum by Spray Drying with Mixtures of Aloe Vera Mucilage and Agave Fructans as Wall Materials. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S.; Noshad, M.; Rastegarzadeh, S.; Hojjati, M.; Fazlara, A. Electrospun Chia Seed Mucilage/PVA Encapsulated with Green Cardamonmum Essential Oils: Antioxidant and Antibacterial Property. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, F.S.; de Figueirêdo, R.M.F.; de Melo Queiroz, A.J.; Paiva, Y.F.; de Araújo, A.C.; de Lima, T.L.B.; de Brito Araújo Carvalho, A.J.; dos Santos Lima, M.; de Macedo, A.D.B.; Campos, A.R.N. Physical, Chemical, and Thermal Properties of Chia and Okra Mucilages. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 7463–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeoh, T.; Wong, D.E.; Strobel, S.A.; Hudnall, K.; Pereira, N.R.; Williams, K.A.; Arbaugh, B.M.; Cunniffe, J.C.; Scher, H.B. How Alginate Properties Influence in situ Internal Gelation in Crosslinked Alginate Microcapsules (CLAMs) Formed by Spray Drying. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, V.; Chotiko, A.; Chouljenko, A.; Sathivel, S. Viability of Lactobacillus acidophilus NRRL B-4495 Encapsulated with High Maize Starch, Maltodextrin, and Gum Arabic. LWT 2018, 96, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.; Castro, H.; Kirby, R. Evidence of Membrane Lipid Oxidation of Spray-dried Lactobacillus bulgaricus during Storage. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 22, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Richa; Choudhury, A.R. Enhanced Encapsulation Efficiency and Controlled Release of Co-Encapsulated Bacillus coagulans Spores and Vitamin B9 in Gellan/κ-Carrageenan/Chitosan Tri-Composite Hydrogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 227, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Oomah, B.D.; Rubilar, M.; Shene, C. Effective Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium infantis Encapsulation with Chia Seed (Salvia hispanica L.) and Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) Mucilage and Soluble Protein by Spray Drying. Food Chem. 2017, 216, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nami, Y.; Kiani, A.; Elieh-Ali-Komi, D.; Jafari, M.; Haghshenas, B. Impacts of Alginate–Basil Seed Mucilage–Prebiotic Microencapsulation on the Survival Rate of the Potential Probiotic Leuconostoc mesenteroides ABRIINW.N18 in Yogurt. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2023, 76, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Scher, H.B.; Jeoh, T. Industrially Scalable Complex Coacervation Process to Microencapsulate Food Ingredients. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 59, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Adhikari, R.; Kasapis, S.; Adhikari, B. Molecular and Functional Characteristics of Purified Gum from Australian Chia Seeds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Cao, W.; Li, L.; Ren, G.; Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Duan, X. Research Progress in Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds in Protein–Polysaccharide Non-Covalent and Covalent Complexes. Shipin Kexue 2023, 44, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, E.; Schiffman, J.D. Targeted Release of Live Probiotics from Alginate-Based Nanofibers in a Simulated Gastrointestinal Tract. RSC Appl. Polym. 2024, 2, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.; Niakousari, M.; Eskandari, M.H.; Shekarforoush, S.S.; Majdinasab, M. Microencapsulation of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG ATCC 53103 by Freeze-Drying: Evaluation of Storage Stability and Survival in Simulated Infant Gastrointestinal Digestion. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 5211–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Ze, X.; Deng, C.; Xu, S.; Ye, F. Multispecies Probiotics Complex Improves Bile Acids and Gut Microbiota Metabolism Status in an In Vitro Fermentation Model. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1314528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadri, R.; Bresson, S.; Aussenac, T. Effect of Alginate Proportion in Glycerol-Reinforced Alginate–Starch Biofilms on Hydrogen Bonds by Raman Spectroscopy. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, H. A pH-Sensitive Curcumin-Loaded Microemulsion-Filled Alginate and Porous Starch Composite Gel: Characterization, In Vitro Release Kinetics and Biological Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).