Abstract

Minimally invasive facial procedures are widely performed in clinical medicine but remain associated with severe complications such as necrosis or blindness, often resulting from insufficient anatomical understanding and limited procedural training. To address these challenges, this study developed an anatomically accurate clinical simulator for facial injection training. A three-dimensional polygonal facial model was constructed using standardized anatomical datasets reflecting skeletal dimensions, soft tissue characteristics and the average arterial distribution of East Asian faces. This model was integrated into simulation software connected to a facial silicone dummy with realistic tissue texture and an optical tracking system providing sub-millimeter precision. Each anatomical structure, including muscles, vessels and nerves, was digitally annotated and linked to interactive visualization tools. During training, the simulator simultaneously reflected the real-time needle trajectory and insertion depth; when the needle tip approached a high-risk structure, such as the supraorbital artery, alerts were automatically triggered. This feedback enabled trainees to recognize unsafe injection zones and adjust their technique accordingly. The system provided a realistic, repeatable and safe environment for improving anatomical comprehension and procedural accuracy. This study proposes an innovative applied simulation system that may enhance medical education and clinical safety in facial injection procedures.

1. Introduction

In contemporary healthcare, improving care quality and ensuring patient safety have emerged as primary goals, yet the risk of clinical errors and adverse effects remains unresolved despite advancements in treatment technologies [1]. Recently, the demand for the field of aesthetics has significantly increased, driven by the improvement of living standards and global beauty trends, accompanied by a parallel increase in post-procedure complications, long-term side effects and related legal disputes [2].

The physiological risks of aesthetic plastic procedures are relatively lower in terms of directly threatening life compared to those in other fields of medicine [3]. However, it has been reported that 86 percent of patients who experience physical complications such as infection, hematoma, nerve injury and pigmentation change develop psychological sequelae of disfigurement leading to a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder [4].

Facial injectable applications are one of the procedures that are continuously growing in the global aesthetic and plastic surgery market, primarily used to improve wrinkles, restore volume in depressed facial areas, and enhance the three-dimensional (3D) contour of specific regions such as the nose and chin [5,6]. Recently, with the growing public understanding of age-related changes in facial appearance and increasing social interest in rejuvenation and aesthetic enhancement, minimally invasive injections into the face that provide immediate results without surgery have gained significant attention [7].

However, insufficient anatomical knowledge or a lack of technical proficiency of the clinicians can lead to serious complications after injection into the face, such as skin necrosis or blindness [8]. Due to concerns and anxiety about procedural failure, clinicians engaged in the field of aesthetic and plastic medicine experience occupational stress [9]. Although beginners require repetitive training to improve the success rate of procedures, adequate training facilities and practical environments remain lacking in the medical fields [10]. Currently, education on injection procedures is provided through various academic conferences and training workshops; however, such programs have limitations in improving technical proficiency for the clinicians [11]. Facial injection requires a personalized approach that considers the facial morphology, skin condition, age and sex for each patient, making it difficult to improve skills through theoretical education or short-term practice [12].

Recently, clinical simulators have been adopted in various educational tools and are recognized as effective instruments for integrating basic and clinical sciences [13]. Rather than replacing learning in real clinical environments, simulators enhance procedural competence by providing learners with opportunities to practice repeatedly beyond time and space, thereby helping them deliver high-quality medical care to patients in actual clinical settings [14]. They also enable multiple users to experience similar situations and exchange immediate feedback, and allow instructors to plan clinical cases independently of patient availability [15]. Increasing attention has been directed toward developing clinical simulators to supplement the limited opportunities for clinical education and training, resulting in expanded research in simulation-based education [16]. The need for a simulator application in facial injection training has also been emphasized [17].

In this study, to address complications and medical accidents caused by unskilled techniques during facial procedures and the lack of opportunities for adequate procedural training, a clinical simulator for injection training was developed and implemented based on anatomical data as an alternative to improve procedural proficiency without temporal or spatial constraints.

2. Materials and Methods

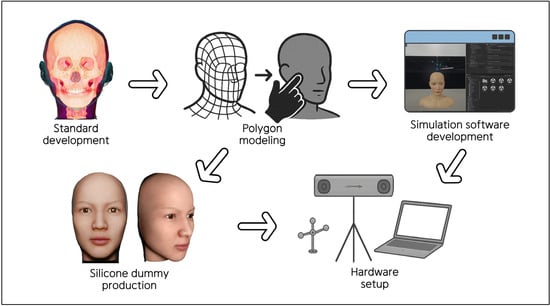

The development and implementation of the interactive clinical simulator for facial injection training comprised five steps: 1. Standard development with facial anatomy data; 2. Polygon modeling; 3. Development of simulation software; 4. Production of a facial silicone dummy; and 5. Hardware setup. Details of each stage are provided below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structured protocol for the development of the clinical simulator.

2.1. Standard Development with Facial Anatomy Data

The data used for the facial model of the clinical simulator were constructed to accurately represent the anatomical structures of the face from the most superficial to the deepest layers. These data were based on detailed human morphology information, including the gross features such as the skeletal and soft tissue structures and the courses of the neurovascular structures.

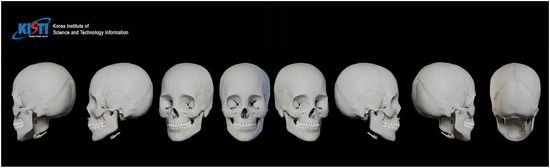

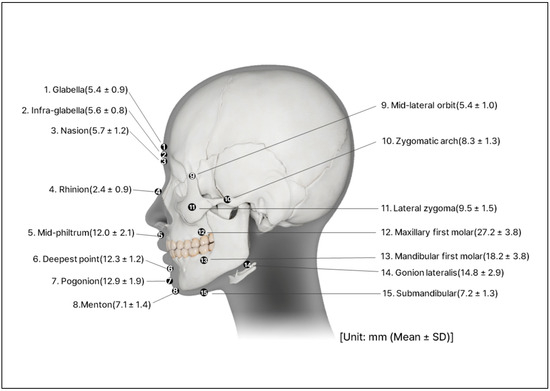

The skeletal framework and morphometric data forming the basic shape and contour of the face were obtained from the Digital Korean Human Model Database of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information [18] (Figure 2). The thickness of the soft tissue was determined from cone-beam computed tomography by measuring the vertical depth at the various facial landmarks (Figure 3) [19].

Figure 2.

Visualization of the standardized female skull model from multiple perspectives.

Figure 3.

Perpendicular soft tissue thickness on the various landmarks of the face.

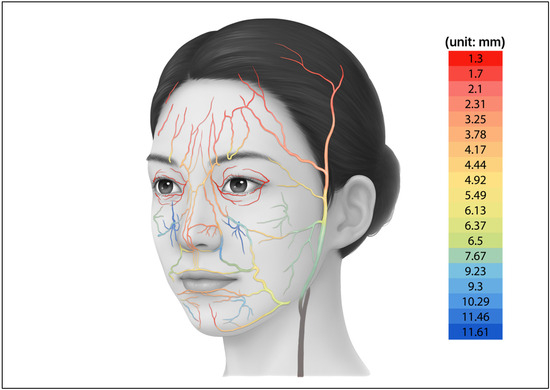

Information on major vascular structures with high risk of complications during the injection of materials, particularly the depth and course of the arteries in the face, was collected from previous anatomical studies [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. To integrate the findings from previous research, all available publications that could be identified through PubMed and Google Scholar using the keywords “face”, “arteries” and “depth” were reviewed. Arterial depth values for individual facial vessels were extracted from each study, and when two or more studies reported measurements for the same artery, the values were averaged to obtain a representative depth for that artery. Based on these data, a two-dimensional illustration was created to visualize the arterial distribution (Figure 4). The arterial dataset was composed by integrating quantitative values reported in multiple population studies, allowing the vascular patterns of the facial model to reproduce anatomy observed in real human specimens.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional illustration of the arteries in the face with depth value.

2.2. Polygon Modeling

Based on the anatomical data of the standardized East Asian face, a 3D polygonal model was designed to reflect the morphology of the real human face. A human subject was selected and facial photographs were taken from multiple directions to capture the contour of the face. These photographs were processed using the 3D reconstruction software (version 2023.1.0; Meshroom, AliceVision, Paris, France) to generate an initial low-polygon model.

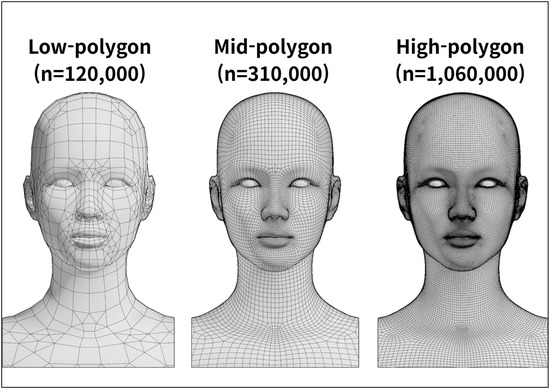

The automatically generated polygonal mesh reflected the general facial contour but remained a simple form. To improve anatomical precision, the mesh density was adjusted using the modeling software (version 3.5.1; Blender, Blender Foundation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) while continuously comparing the model with the standardized East Asian facial dataset (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Low to high polygonal mesh of the three-dimensional facial model.

In the refinement stage, the high-precision modeling software (version 2023.1.1; ZBrush, Pixologic, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used to align the overall facial proportions with those of the standardized East Asian facial ratio, focusing particularly on the position and size of the eyes and nose as well as the contour of the lips. During the texturing and rendering process, skin details such as pores, wrinkles and fine surface irregularities were added to reproduce the natural texture of human skin. Color tone and surface gloss were also applied, resulting in a visually realistic high-polygon facial model.

2.3. Development of Simulation Software

The software program for a clinical simulator (version 2022.3.39.6927; AXNavDermaInjection, Surgical Mind Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) was developed for the procedural guidance of injection. This software development was conducted over a period of 18 months, from July 2023 to December 2024, and was built on the development platform (version 2022.3.39f1; Unity, Unity Technologies, San Francisco, CA, USA). The 3D modeling of the syringe and other instruments used in the procedure was implemented using the modeling software (version 3.5; Blender, Blender Foundation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

The previously constructed high-polygon facial model was optimized to improve computational efficiency by using a normal vector–based compression solution (version 9.0; Adobe Substance 3D Painter, Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), resulting in an 80% reduction in data size to approximately 20% of the original dataset. Curved anatomical structures, such as blood vessels, were simplified from circular cross-sections to hexagonal or octagonal forms, while curvature and texture were maintained using the same refinement method.

The finalized software was designed to synchronize simultaneously with the virtual model by detecting the spatial positions of the physical syringe and silicone dummy through an external optical tracking system.

The implemented main functions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main functions implemented in the simulation software.

2.4. Production of a Facial Silicone Dummy

In this study, a facial silicone dummy was fabricated to serve as a physical model that receives actual needle insertions during facial injection training and operates in synchronization with the simulation software. A master pattern, representing the original form of the silicone dummy, was produced by 3D printing based on the standardized 3D facial polygonal model. The surface details of the pattern, including skin texture, wrinkles and pores, were refined using the modeling program (ZBrush, Pixologic Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA).

A negative mold was then created by applying a mixture of plaster and synthetic resin over the completed pattern using a reverse casting technique. An external supporting frame was fabricated to prevent deformation during the curing process. The mold was cured for 90 min with a final hardness of Shore 70D. After curing, the surface was evenly coated with a release agent (ER-200 Spray, Mann Release Technologies Inc., Macungie, PA, USA) to prevent surface damage, and the mold was manually demolded.

The inner cavity of the completed mold was filled with addition-cure silicone (SJS-1330, Sejin Silicone Inc., Goyang, Republic of Korea) to form the outer structure. The soft tissue was created using platinum-cured silicones (Ecoflex 00-10; and Ecoflex 00-20, Smooth-On Inc., Macungie, PA, USA). Both materials were processed at a 1:1 mixing ratio and cured for approximately 6 h. The platinum-cured silicones were selected because their high elasticity allows the material to expand and retain injected volume, providing a more realistic post-injection response compared with conventional commercial silicones. These materials allow for partial regurgitation of the injectables during needle withdrawal, which reproduces the typical pattern observed in human soft tissue.

To reproduce a natural skin tone, the pigment (Slic Pig, Smooth-On Inc., Macungie, PA, USA) was blended in proportions not exceeding 3% of the total silicone weight. For surface finishing, a mixture of pigment (Psycho Paint; and Novocs, Smooth-On Inc., Macungie, PA, USA) was applied at a 1:1 mixing ratio to achieve a realistic texture and a typical East Asian skin tone. This coating layer had a working time of 45 min and was fully cured within 24 h.

To ensure the structural stability of the silicone dummy during repeated injection training, an internal supporting framework made of a lightweight, high-strength thermoplastic polymer was embedded within the silicone structure. This framework was 3D-printed via additive manufacturing, providing rigidity while maintaining material compatibility with the silicone soft tissue layers.

2.5. Hardware Setup

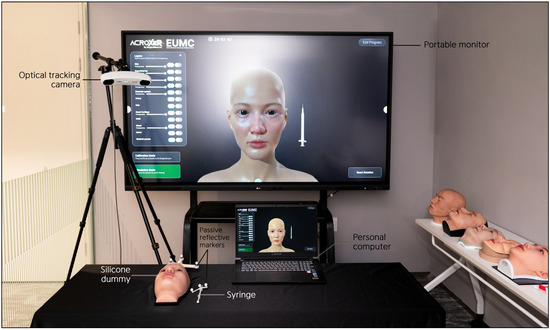

The hardware system for operating the clinical simulator and providing simultaneous feedback was installed in Ewha Medical Academy at Ewha Womans University Medical Center. This facility represents one of the first integrated medical simulation laboratories in Korea, supporting an interactive environment for simulator operation and user feedback.

The system consisted of a computer for running the simulation software, a large monitor for real-time visual feedback, an optical tracking camera for detecting the motion of the user and the position of the silicone dummy and tracking markers attached to the target objects for positional recognition. The recommended specifications for the operating computer included an Intel Core i5-12600K CPU, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU, 16 GB RAM and an NVMe SSD (500 GB with at least 10 GB of free space).

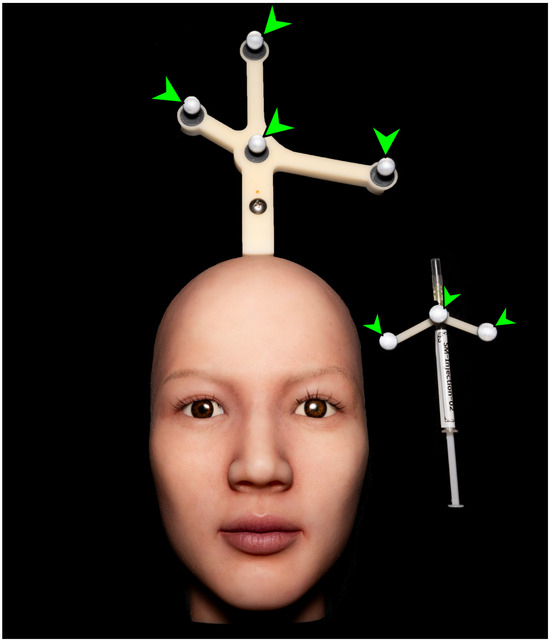

For real-time visualization, a large portable monitor (86TN3FLG, LG Electronics, Seoul, Republic of Korea) was connected to the system. An optical tracking camera (NDI Vega VICRA, Northern Digital Incorporated, Waterloo, ON, Canada) was installed to detect the movement of the syringe and the positional changes of the silicone dummy. To enhance motion-tracking accuracy, passive reflective markers were attached near the vertex region of the silicone dummy and along the body of the syringe, enabling the optical camera to detect reflected signals (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Photograph showing passive reflective markers attached to the silicone dummy and the syringe body. Green arrowheads indicate the spherical ball markers.

The complete hardware setup of the clinical simulator is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Photograph of the hardware setup of the clinical simulator.

3. Results

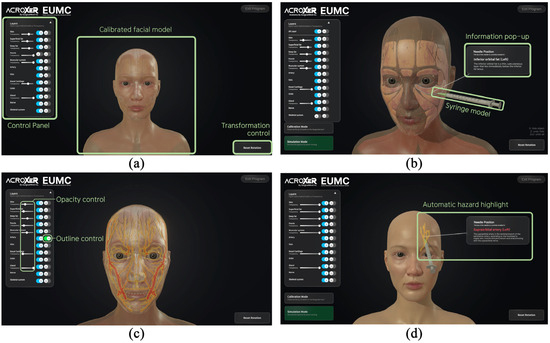

During clinical simulator operation, the volumetric root mean square accuracy was 0.25 mm and the 95 percent confidence interval for volumetric accuracy was 0.50 mm. The maximum frame rate, which represents the measurement update rate, reached 20 Hz. The optical tracking camera, positioned approximately 90 to 100 cm from the silicone dummy, demonstrated a spatial measurement reproducibility of 0.029 to 0.045 mm and a dynamic tracking error of less than one millimeter. When the optical camera detected the passive reflective markers, the system continuously calculated the spatial coordinates of the dummy and syringe in real time and projected their movements onto the monitor screen. The basic user interface design is presented in Figure 8a. The trajectory of the syringe was simultaneously visualized on the screen, and when the needle tip contacted a virtual anatomical structure, the system calculated the coordinate data and displayed the structure name and anatomical description in a pop-up window within approximately 0.05 s (Figure 8b). Through this process, users were able to recognize the anatomical context of each injection site immediately.

Figure 8.

Screenshots of the user interface of the simulation software for injection training: (a) Basic interface layout presenting the calibrated facial model, the control panel for adjusting anatomical structures and the transformation control used for model rotation and orientation; (b) Information pop-up generated when the needle tip contacts a virtual anatomical structure; (c) Transparency and outline control functions for the virtual facial model; (d) Automatic hazard highlight activated when the needle approaches vascular structures with red and yellow glow.

The simulator incorporated visibility control and transparency adjustment functions, allowing users to explore the relative positions and depth distribution of anatomical structures step by step (Figure 8c). When the needle approached critical vascular structures such as the dorsal nasal artery, supraorbital artery and supratrochlear artery, whose branches originate from the ophthalmic artery and form complex anastomotic networks that increase the risk of blindness and necrosis if inadvertently injected, the system issued a visual warning by activating a red and yellow outline glow shader, clearly indicating regions that required anatomical caution (Figure 8d). When a target structure had been highlighted in advance, the highlight disappeared once the needle tip reached the corresponding layer, providing an immediate visual indication of correct placement as defined by the spatial feedback mechanism of the system. This response occurred whenever the needle tip entered the predefined spatial threshold associated with the highlighted structure, regardless of the manner in which the contact was made. The facial model could be rotated and tilted freely, enabling users to observe anatomical relationships from multiple perspectives and to perform repeated procedural training with improved spatial awareness.

4. Discussion

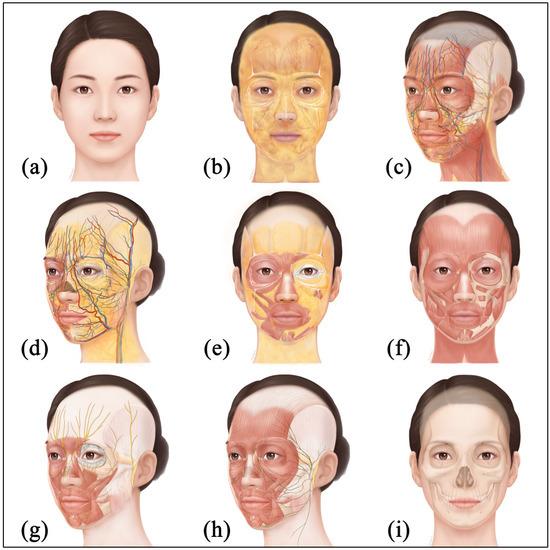

The face is closely related to the social identity of an individual beyond the concept of external image and plays a central role in human social interaction [33]. Facial expression, the eyes and the skin function as primary mediators that convey emotional states to others and serve important roles in social communication [34]. Aesthetic investment is concentrated on the face because it is one of the most visually exposed body regions and the self-image expressed through the face leaves strong impressions and memories in others. For these reasons, the face has become a central area of aesthetic medicine, and the complex anatomy of the face is an important consideration for clinicians. The face has a multilayered structure and vessels and nerves are intricately arranged (Figure 9); therefore, high anatomical precision and fine technical skill for medical procedures are required.

Figure 9.

Illustrations of the face with anatomical structures: (a) Skin layer; (b) Superficial fat layer with ligamentous structures; (c) Superficial musculoaponeurotic system and mimic muscle layer with neurovascular structures; (d) Deep fat layer with neurovascular structures; (e) Deep fat layer with muscle and ligamentous structures; (f) Muscle layer of the face; (g) Trigeminal nerves and facial muscles; (h) Facial nerves and muscles; and (i) Periosteum and craniofacial bone layer.

Demand for education and procedural training in facial anatomy continues to increase in clinical settings, but most training still remains limited to formats such as seminars and symposiums. Education in clinical environments is restricted for patient safety, and although training using donated cadavers is highly effective for understanding human anatomy, widespread adoption is difficult due to a shortage of cadavers, ethical constraints, limitations of educational facilities and a lack of specialized personnel [35,36]. Accordingly, procedural training using simulators has attracted attention as an alternative that can prevent medical accidents and disputes caused by insufficient anatomical knowledge and limited procedural experience [37]. Clinical simulators were originally introduced in anesthesiology and have advanced through the convergence of computer engineering, biomedical engineering and behavioral science [13]. These systems combine life-size dummies with interactive software to reproduce diverse clinical scenarios and enable repetitive, standardized, anatomy-based training [38]. Simulation-based education is evaluated as a cost-effective method that complements the ethical, practical and financial limitations of cadaver-based education by allowing repeated practice in a safe and controlled environment, and offsetting long-term costs relative to the initial setup investment.

Previous studies have reported that simulator-based training improves theoretical and practical knowledge, procedural confidence, teamwork and patient outcomes [39,40]. Not only beginners but also experts with experience in clinical medicine can seek skill enhancement through such training; therefore, clinical simulator learning has a wide scope of application. Above all, the greatest advantage of simulators is the possibility of repetitive training. When vessels are damaged during use or when physical contact is made with neural tissues that should be avoided, users can recognize and verify this through immediate visual feedback. In addition, self-directed learning can be conducted without an instructor and substantial progress in procedural competence can be achieved through the acquisition of greater anatomical knowledge and training. In the clinical simulator developed in this study, a larger set of standard data for East Asian faces was incorporated with the previously developed VR-based injection simulator, which served as the foundational prototype in aesthetic injection training [17]. The expanded dataset enabled the anatomical structures such as muscles, vessels and nerves, to be modeled with greater 3D fidelity and quantitative precision. The use of an optical tracking camera with higher resolution and higher capability allowed syringe motion to be monitored in real time without delay, which resulted in improved procedural training compared with the earlier system. A dummy model with an external appearance and skin texture similar to those of a real human face was developed and linked with the software, thereby further enhancing the realism and educational effect of the simulator. The polygonal model developed in this study was efficiently compressed to a small size without image quality degradation based on vector-quantization compression during application-software implementation, providing the technical advantage that implementation is possible without dependence on high-performance hardware. The differences between the existing and the presently developed simulators for facial injection training are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of current and existing models of the clinical simulator for facial injection training.

Meanwhile, some users of clinical simulators may experience cognitive fatigue due to excessive focus on digital learning, and there is a risk that the simulation experience may blur the distinction from reality [41]. In addition, low-quality simulation content and a shortage of qualified simulator faculty can degrade the quality of learning and hinder educational effectiveness [42]. Initial equipment setup costs, such as software licenses and hardware procurement, costs for technical maintenance and management and requirements for personnel training and programming remain major challenges in implementing simulators [43]. Although the clinical simulator for facial injection training developed in this study reflects improved facial anatomical data compared with existing systems, an ongoing task is to update skeletal and soft tissues with sample datasets from more population groups studied to date [44,45,46], not only East Asian data (Table 3).

Table 3.

Representative study populations and reference sources used for cranial and facial soft tissue datasets across studies.

The arterial depth value incorporated into the simulator in this study is derived from studies conducted across multiple population groups, and its variation among populations is relatively small compared with skeletal morphology. However, the basic craniometric and soft tissue structures used in the current system are based on East Asian data, and future development should include multiple simulator versions that reflect population-specific anatomical characteristics to provide models customized to different demographic groups. In this study, the silicone dummy and syringe were produced to be more realistic than those previously developed to improve the user’s training experience, but technical limitations still exist in perfectly reproducing the actual clinical environment. For example, whereas tissues move or change during actual procedures depending on the amount and material properties of the injectables, the simulator has the limitation that it cannot reflect the movement or deformation of anatomical structures in real time. Therefore, advancing simulator to incorporate the dynamic deformation of silicone material remains an important task for development. In addition, although the simulator can analyze user manipulations and provide feedback, its responses are relatively limited. Injection procedures are highly delicate tasks, and during actual procedures, the method must be adjusted according to changes in the face, but current simulators find it difficult to respond perfectly to this. For instance, the training content should differ depending on whether a hypodermic needle or a cannula with a blunted needle tip is used as the procedural instrument, but there is the inconvenience that a single system supports only one type of instrument. In this study, only a straight hypodermic needle was implemented, because the depth estimation of the needle tip became unreliable when a flexible cannula was used. The optical marker for motion tracking was attached to the syringe body, and once the cannula entered the silicone dummy, the tracking camera could detect only the external marker and not the actual position of the tip within the material. As a result, it was not feasible in this version of the system to implement cannula-based procedures with sufficient accuracy. Future clinical simulators to be developed need to add systems that are compatible with multiple procedural instruments and to incorporate tracking methods capable of accurately estimating the position of the cannula tip inside a deformable dummy.

For continuous improvement, it is essential to gather and analyze feedback from diverse users and to regularly inspect the performance of the simulator, including the durability and stability of the hardware components such as the personal computer, the optical tracking system and the silicone dummy. Verification of the operational adaptability across different temperature and humidity conditions should also be conducted to ensure reliable performance in various training environments.

The analytical methodologies proposed in other studies have primarily relied on subjective evaluations such as user satisfaction and confidence, which limits the assessment of the objective reliability and validity of simulators [47]. The evaluation framework requires the use of objective psychometric indices, including inter-rater reliability, to determine the consistency of assessments made by different evaluators. Future research needs to be conducted as large-scale studies carried out under appropriate ethical approval, allowing an objective evaluation of whether simulator-based training is effective and reliable when applied to actual users. Such studies should quantify improvements before and after training, determine the extent to which acquired skills are retained over extended periods, and assess potential limitations such as cognitive fatigue.

An ideal future simulator should include diverse simulation scenarios such as wrinkle improvement, volume correction and line refinement, and should support adjustable levels of difficulty appropriate for users with different levels of experience. It should also incorporate functions for storing individual training records, providing objective summaries of learning progress after each session, and maintaining data security. Although the simulator developed in this study is currently specialized for facial injection training, it has the potential to be extended to other clinical procedural domains such as lumbar puncture, intravenous injection and various ostomy management and care training on the basis of the same technical architecture. Such expansion requires establishing standardized anatomical datasets for each target body region, modularizing the tracking and feedback algorithms so that they can be adapted to different procedural instruments, and developing task-specific interfaces that reflect the workflow of each clinical procedure. The system could thus be advanced into a more comprehensive clinical simulation platform by integrating anatomical datasets for different body regions.

5. Conclusions

This study presented the detailed process for developing and implementing a clinical simulator for facial injection training and proposed an alternative learning tool that can address the limitations of traditional anatomy education.

This simulator, based on precise anatomical knowledge, provides an accurate and realistic learning environment and is anticipated to enhance the anatomical understanding and procedural skills of clinicians in aesthetic medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-Y.S., S.-C.C. and S.-H.H.; methodology, J.-Y.S. and S.-H.H.; software, H.-S.C., I.K. and D.Y.; validation, J.-Y.S., I.K. and S.-H.H.; formal analysis, J.-Y.S. and D.Y.; investigation, J.-Y.S., H.-S.C. and B.-H.K.; resources, S.-C.C. and B.-H.K.; data curation, J.-Y.S. and D.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-Y.S. and S.-C.C.; writing—review and editing, J.-Y.S. and S.-H.H.; visualization, J.-Y.S., H.-S.C. and I.K.; supervision, S.-H.H.; project administration, J.-Y.S., S.-C.C. and B.-H.K.; funding acquisition, S.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (RS-2023-KH134708), and by Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI) (No. K25L3M1C2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access will be considered for academic or research purposes following review and approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Ewha Medical Academy at Ewha Womans University Medical Center for providing research facilities and technical assistance during the development of the clinical simulator. The authors also express their appreciation to Suhyun Chae for creating the two-dimensional illustration of the facial anatomy used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Il Kim was employed by the company Surgical Mind Inc., and author Byeong-Ha Kim was employed by BH 3D Art Center. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; Philippart, F.; Bruel, C.; Max, A.; Lau, N.; Misset, B. Overview of medical errors and adverse events. Ann. Intensive Care 2012, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kang, S.R.; Hong, S.E. A Legal Analysis of the Precedents of Medical Disputes in the Cosmetic Surgery Field. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2016, 43, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montrief, T.; Bornstein, K.; Ramzy, M.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B.J. Plastic Surgery Complications: A Review for Emergency Clinicians. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borah, G.; Rankin, M.; Wey, P. Psychological complications in 281 plastic surgery practices. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999, 104, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagien, S.; Klein, A.W. A brief overview and history of temporary fillers: Evolution, advantages, and limitations. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 120, 8S–16S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorini, M.; Liew, S.; Sundaram, H.; De Boulle, K.L.; Goodman, G.J.; Monheit, G.; Wu, Y.; Trindade de Almeida, A.R.; Swift, A.; Vieira Braz, A. Global Aesthetics Consensus: Avoidance and Management of Complications from Hyaluronic Acid Fillers-Evidence- and Opinion-Based Review and Consensus Recommendations. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 961e–971e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, T.M.; Antunes, M.B.; Yellin, S.A. Injectable fillers for volume replacement in the aging face. Facial Plast. Surg. 2012, 28, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sito, G.; Manzoni, V.; Sommariva, R. Vascular Complications after Facial Filler Injection: A Literature Review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2019, 12, E65–E72. [Google Scholar]

- Vitous, C.A.; Byrnes, M.E.; De Roo, A.; Jafri, S.M.; Suwanabol, P.A. Exploring Emotional Responses After Postoperative Complications: A Qualitative Study of Practicing Surgeons. Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, e124–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, S.; Blenkinsopp, E.; Hall, A.; Walton, G. Effective e-learning for health professionals and students--barriers and their solutions. A systematic review of the literature--findings from the HeXL project. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2005, 22, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.P.; Toyoda, Y.; Christopher, A.N.; Broach, R.B.; Percec, I. A Systematic Review of Aesthetic Surgery Training Within Plastic Surgery Training Programs in the USA: An In-Depth Analysis and Practical Reference. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2022, 46, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Rahman, E.; Adds, P.J. An effective and novel method for teaching applied facial anatomy and related procedural skills to esthetic physicians. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, 9, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ypinazar, V.A.; Margolis, S.A. Clinical simulators: Applications and implications for rural medical education. Rural Remote Health 2006, 6, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, N.J.; Glavin, R.J. Low- to high-fidelity simulation—A continuum of medical education? Med. Educ. 2003, 37, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, M.M.; Nuthalapaty, F.S.; Goepfert, A.R.; Casey, P.M.; Emmons, S.; Espey, E.L.; Kaczmarczyk, J.M.; Katz, N.T.; Neutens, J.J.; Peskin, E.G. To the point: Medical education review of the role of simulators in surgical training. Am. J. Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamé, G.; Dixon-Woods, M. Using clinical simulation to study how to improve quality and safety in healthcare. BMJ Simul. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2020, 6, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Han, S.; Lee, W.; Kim, I.; Hong, G.; Oh, W.; Moon, H. Changmin Seo Development and Usability of a Virtual Reality-Based Filler Injection Training System. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2020, 44, 1833–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Korean Human Information System for Better Project. Available online: https://dk.kisti.re.kr/ (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Hwang, H.S.; Choe, S.Y.; Hwang, J.S.; Moon, D.-N.; Hou, Y.; Lee, W.-J.; Wilkinson, C. Reproducibility of Facial Soft Tissue Thickness Measurements Using Cone-Beam CT Images According to the Measurement Methods. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfertshofer, M.G.; Frank, K.; Moellhoff, N.; Helm, S.; Freytag, L.; Mercado-Perez, A.; Hargiss, J.B.; Dumbrava, M.; Green, J.B.; Cotofana, S. Ultrasound Anatomy of the Dorsal Nasal Artery as it Relates to Liquid Rhinoplasty Procedures. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 30, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Cong, L.Y.; Kong, X.X.; Zhao, W.R.; Hong, W.J.; Luo, C.E.; Luo, S.K. Three-Dimensional Computed Tomography Scanning of Temporal Vessels to Assess the Safety of Filler Injections. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2021, 41, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.H.; Eom, J.R.; Lee, J.W.; Yang, J.D.; Chung, H.Y.; Cho, B.C.; Choi, K.Y. Zygomatico-orbital artery: The largest artery in the temporal area. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2018, 71, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.Y.; Liao, Z.F.; Zhang, Y.S.; Li, D.N.; Luo, S.K. Three-Dimensional Arterial Distribution Over the Midline of the Nasal Bone. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2022, 42, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagistan, S.; Miloǧlu, Ö.; Altun, O.; Umar, E.K. Retrospective morphometric analysis of the infraorbital foramen with cone beam computed tomography. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2017, 20, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.H.; Kim, S.W.; Park, C.S.; Kim, S.W.; Cho, J.H.; Kang, J.M. Morphometric analysis of the infraorbital groove, canal, and foramen on three-dimensional reconstruction of computed tomography scans. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2013, 35, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasanizadeh, F.; Delazar, S.; Gheidari, O.; Daneshpazhooh, M.; Balighi, K.; Ehsani, A.H.; Emadi, S.N.; Sadeghinia, A.; Mahmoudi, H. Anatomic evaluation of the normal variants of the arteries of face using color Doppler ultrasonography: Implications for facial aesthetic procedures. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 1844–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.L.; Lee, H.J.; Youn, K.H.; Kim, H.J. Positional relationship of superior and inferior labial artery by ultrasonography image analysis for safe lip augmentation procedures. Clin. Anat. 2020, 33, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Money, S.M.; Wall, W.B.; Davis, L.S.; Edmondson, A.C. Lumen Diameter and Associated Anatomy of the Superior Labial Artery with a Clinical Application to Dermal Filler Injection. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumyoo, T.; Jiirasutat, N.; Jitaree, B.; Rungsawang, C.; Uruwan, S.; Tansatit, T. Anatomical and Ultrasonography-Based Investigation to Localize the Arteries on the Central Forehead Region During the Glabellar Augmentation Procedure. Clin. Anat. 2020, 33, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansatit, T.; Phumyoo, T.; Sawatwong, W.; McCabe, H.; Jitaree, B. Implication of Location of the Ascending Mental Artery at the Chin Injection Point. Plast. Reconst.r Surg. 2020, 145, 51e–57e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten, B.; Kara, T.; Kaya, T.İ.; Yılmaz, M.A.; Temel, G.; Balcı, Y.; Türsen, Ü.; Esen, K. Evaluation of facial artery course variations and depth by Doppler ultrasonography. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; He, R.; Chen, T.; Haining, W.; Goossens, R.; Huysmans, T. Soft tissue thickness estimation for head, face, and neck from CT data for product design purposes. Ergon. Des. 2022, 47, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargiela-Chiappini, F.; Haugh, M. Face Communication and Social Interaction; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009; pp. 1–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kret, M.E. Emotional expressions beyond facial muscle actions. A call for studying autonomic signals and their impact on social perception. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azer, S.A.; Eizenberg, N. Do we need dissection in an integrated problem-based learning medical course? Perceptions of first- and second-year students. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2007, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, D.S.; Sultana, B. Potential health hazards for students exposed to formaldehyde in the gross anatomy laboratory. J. Environ. Health 2012, 74, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, E.A.; Nelson, K.L.; Shilkofski, N.A. Simulation in medicine: Addressing patient safety and improving the interface between healthcare providers and medical technology. Biomed. Instrum. Technol. 2006, 40, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, M.; Fukutomi, M.; Nagamune, M.; Fujimoto, A.; Tsuji, A.; Ishida, K.; Iwata, T. Simulation-based medical education in clinical skills laboratory. J. Med. Investig. 2012, 59, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.; Curry, N. Simulation training improves clinical knowledge of major haemorrhage management in foundation year doctors. Transfus. Med. 2014, 24, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, Y.; Bryson, E.O.; DeMaria, S., Jr.; Jacobson, L.; Quinones, J.; Shen, B.; Levine, A.I. The utility of simulation in medical education: What is the evidence? Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2009, 76, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larue, C.; Pepin, J.; Allard, E. Simulation in preparation or substitution for clinical placement: A systematic review of the literature. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2015, 5, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.L.; Østergaard, D.; LeBlanc, V.; Ottesen, B.; Konge, L.; Van der Vleuten, C. Design of simulation-based medical education and advantages and disadvantages of in situ simulation versus off-site simulation. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussi, E.; Furferi, R.; Volpe, Y.; Facchini, F.; McGreevy, K.S.; Uccheddu, F. Ear Reconstruction Simulation: From Handcrafting to 3D Printing. Bioengineering 2019, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogman, W.M. The Human Skeleton in Forensic Medicine, 2nd ed.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1986; pp. 268–280. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, H.; Tanijiri, T.; Kouchi, M.; Hanihara, T.; Friess, M.; Moiseyev, V.; Stringer, C. Global patterns of the cranial form of modern human populations described by analysis of a 3D surface homologous model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, C.N.; Simpson, E.K. Facial soft tissue depths in craniofacial identification (part I): An analytical review of the published adult data. J. Forensic Sci. 2008, 53, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, D.G.; Keloth, A.V.; Ubedulla, S. Pros and cons of simulation in medical education: A review. Education 2017, 3, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).