Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) printing enables accurate implant pre-shaping in orbital reconstruction but is costly and time-consuming. Naked-eye stereoscopic displays (NEDs) enable virtual implant modeling without fabrication. This study aimed to compare the reproducibility and accuracy of NED-based virtual reality (VR) pre-shaping with conventional 3D-printed models. Two surgeons pre-shaped implants for 11 unilateral orbital floor fractures using both 3D-printed and NED-based VR models with identical computed tomography data. The depth, area, and axis dimensions were measured, and reproducibility and agreement were assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), Bland–Altman analysis, and shape similarity metrics—Hausdorff distance (HD) and root mean square error (RMSE). Intra-rater ICCs were ≥0.80 for all parameters except depth in the VR model. The HD and RMSE reveal no significant differences between 3D (2.64 ± 0.85 mm; 1.02 ± 0.42 mm) and VR (3.14 ± 1.18 mm; 1.24 ± 0.53 mm). Inter-rater ICCs were ≥0.80 for the area and axes in both modalities, while depth remained low. Between modalities, no significant differences were found; HD and RMSE were 2.95 ± 0.94 mm and 1.28 ± 0.49 mm. The NED-based VR pre-shaping achieved reproducibility and dimensional agreement comparable to 3D printing, suggesting a feasible cost- and time-efficient alternative for orbital reconstruction. These preliminary findings suggest that NED-based preshaping may be feasible; however, larger studies are required to confirm whether VR can achieve performance comparable to 3D-printed models.

1. Introduction

Orbital floor fractures are among the most common injuries encountered in craniofacial trauma [1]. Patients typically present with swelling, hematoma, ocular motility disturbances, diplopia, enophthalmos, and infraorbital nerve dysfunction, all of which significantly impair both function and aesthetics [2]. As these injuries often affect young individuals, their long-term impact on quality of life can be considerable [3]. Surgical interventions, including insertion of implant on bony defect site, and precise orbital floor reconstruction, are indicated for unstable, markedly displaced, and comminuted fractures. However, achieving anatomical accuracy is technically challenging owing to the complex three-dimensional (3D) architecture of the orbit [4,5,6]. Preoperative preshaping of implants on patient-specific 3D-printed anatomical models has been introduced to address these challenges [7,8,9]. This approach requires the production of 3D models, which entails additional costs, and the time required for their fabrication often necessitates coordination with surgical scheduling [10]. Recently, 3D technologies such as virtual (VR) and augmented (AR) reality have rapidly advanced, with increasing applications in the medical field—particularly for surgical guidance, navigation, and education [11,12]. VR devices enable users to visualize and manipulate 3D computer-generated models in real space, whereas most VR/AR devices are head-mounted displays (HMDs). Although HMD-based VR/AR has been evaluated for clinical use, several drawbacks have been reported, including the need for repeated adjustments of the interpupillary distance (IPD) for each user and the potential visual overlap that can reduce stereoscopic accuracy [13,14,15]. Due to these drawbacks, the use of VR technology with HMD for preshaping orbital floor fractures is not currently common.

To overcome these limitations, a novel naked-eye stereoscopic display (NED) was developed [16]. A NED provides stereoscopic visualization without the need for HMDs, allowing surgeons to maintain a natural posture, work with both hands, and manipulate implant materials while viewing a three-dimensional anatomical image. Moreover, unlike 3D-printed bone models, NEDs can instantaneously generate patient-specific VR models from Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) or stereolithography (STL) data without the need for physical fabrication, eliminating additional costs and production time [17,18,19]. Despite these ergonomic and workflow-related advantages, it remains unclear whether NED-based VR visualization can support implant preshaping with accuracy comparable to that achieved using conventional 3D-printed models. Moreover, no prior study has quantitatively compared implants molded on NED-based VR models with those shaped on 3D-printed anatomical models.

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of using NEDs for preoperative preshaping of implants in orbital floor fracture reconstruction. Rather than direct clinical application, we conducted a preliminary validation in which the same participants performed implant preshaping using both conventional 3D-printed bone models and NED-generated VR models from identical patient data. This design allowed for a direct, controlled comparison of the accuracy and reproducibility between the two modalities. Compared with conventional 3D-printed models, NED may offer a faster and more cost-effective alternative while maintaining the precision required for orbital reconstruction.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at the National Defense Medical College (Saitama, Japan) with approval from the Institutional Review Board and permission from the ethics committee (no. 5076).

2.1. Participants

Two board-certified plastic and reconstructive surgeons, each with >10 years of clinical experience and >10 primary orbital floor fracture surgeries, participated as examiners. Both had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and limited prior experience with AR devices. The study included 11 patients who underwent orbital computed tomography (CT) scanning with a slice thickness of ≤1 mm between January 2021 and April 2024. All patients had unilateral orbital floor fractures. To ensure a homogeneous study population, only patients with isolated unilateral orbital floor fractures requiring surgical reconstruction were included. Patients were excluded if they had concomitant facial bone fractures, a history of facial trauma or prior orbital surgery, CT imaging of insufficient quality for model generation, or minimally displaced fractures for which surgery was not indicated. All patients provide broad consent at the time of hospital admission. In accordance with institutional and national research ethics policies, the study protocol was formally approved by the Institutional Review Board before data analysis, and an opt-out notice along with the right to refuse participation was posted on the institutional website.

2.2. Data Acquisition

The CT data were exported in DICOM format, and 3D reconstruction was performed using Ziostation2 (Ziosoft, Tokyo, Japan) and converted into STL files.

2.3. Model Preparation

For the 3D-printed models, STL data were processed using a ProJet 660Pro 3D printer (3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC, USA) to fabricate life-size gypsum orbital models. The printer has a layer thickness of 0.1 mm and uses a gypsum-based composite material. After printing, the models were depowdered and infiltrated with a cyanoacrylate solution according to the manufacturer’s recommended post-processing protocol to reinforce material strength. For the VR models, the same STL data were imported into SR View software (Chihiro Enterprise, Tokyo, Japan) and displayed on an actual scale on a Spatial Reality Display (ELF-SR1; Sony, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. Implant Preshaping Procedure

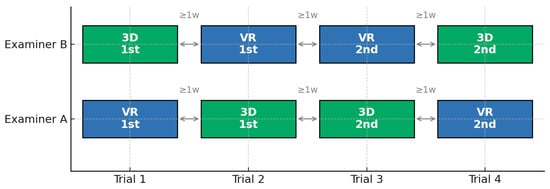

From each model, a patient-specific implant template was created using a 40 mm × 40 mm aluminum plate (thickness, 0.2 mm). During NED pre-shaping, examiners maintained a standardized sitting position at a distance of approximately 30–50 cm from the display to ensure consistent visualization conditions. Both examiners received only a short explanation of the basic NED operations without any formal training session. For the NED-based VR condition, the 3D anatomical image could be freely rotated and tilted on the display to visualize the orbital contour from any direction, as illustrated in Figure 1. Examiners were able to adjust the viewpoint using simple drag-based gestures, and magnification was controlled using standard mouse-scroll input. For the 3D-printed models, the physical model could likewise be freely rotated and repositioned during preshaping. Eleven cases were presented in random order. The time required to shape each implant was recorded using a stopwatch from the moment shaping began until the examiner declared the implant complete. One examiner completed four trials per case in the following sequence: VR model → 3D-printed model → second 3D-printed model trial → second VR model trial. The other examiner performed the reverse sequence, beginning with the 3D-printed model, followed by the VR model, the second VR trial, and finally, the second 3D trial. Each examiner, therefore, produced four templates per case (Figure 2). The presentation order of all cases was randomized using computer-generated random numbers. To minimize recall bias, templates generated in each trial were immediately coded with an anonymous identification number and stored out of the examiner’s view. Examiners were not shown any of their previous templates during any subsequent trial. In addition, an interval of at least one week was imposed between trials of the same case to further reduce potential memory effects.

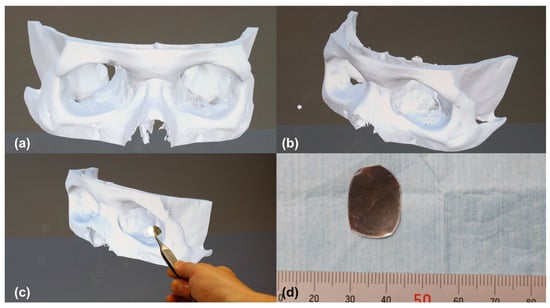

Figure 1.

Preshaping procedure of patient-specific orbital implants using a naked-eye stereoscopic display (NED). (a) Frontal view of the three-dimensional (3D) orbital model projected on the NED. (b) Oblique view of the same model; the 3D image can be freely rotated and tilted on the NED to visualize the orbital contour from any direction. (c) Scene of implant preshaping performed directly against the displayed 3D model using an aluminum plate. (d) Photograph of the completed patient-specific implant shaped with reference to the NED visualization. 3D, three-dimensional; NED, naked-eye stereoscopic display.

Figure 2.

Timeline of implant pre-shaping sequence. One examiner completed four trials per case in the following order: VR model → 3D-printed model → second 3D-printed model trial → second VR model trial. The other examiner performed the reverse sequence, beginning with the 3D-printed model, followed by the VR model, the second VR trial, and finally, the second 3D trial. Each examiner produced four templates per case. To avoid recall bias, an interval of at least 1 week was imposed between each trial. 3D, three-dimensional; VR, virtual reality.

2.5. Outcome Measurements

The flat surface covering the orbital defect was photographed, and contours were extracted using the ImageJ software 1.54 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Photographs were acquired using a Canon EOS R6 camera (Canon, Tokyo, Japan) mounted on a tripod positioned approximately 50 cm above the implant, with the lens oriented orthogonally to the table surface to standardize perspective and minimize distortion. A millimeter scale was placed adjacent to each implant, and ImageJ’s “Set Scale” function was used to convert pixel dimensions to metric units for all measurements. Implant outlines were obtained using ImageJ’s automated thresholding workflow. Images were first smoothed using a Gaussian blur filter (σ = 1.0) to reduce high-frequency noise.

A global threshold (Otsu method) was then applied to generate a binary mask, and the “Analyze Particles” function was used to identify each implant and extract its contour. The major axis length, minor axis length, and contour area were calculated from these contours. Depth was measured using a height gauge. Each preshaped implant was placed on a flat reference surface with the concave side facing downward. The height gauge was positioned vertically, and the maximum vertical distance from the reference plane to the deepest point of the concave surface was recorded as the depth value. Depth was defined as a positive value. Similarly, photographs of the fractured regions of the 3D-printed orbital models were obtained, and the images were processed using ImageJ software to extract the contours, from which the major axis length, minor axis length, and contour area were calculated.

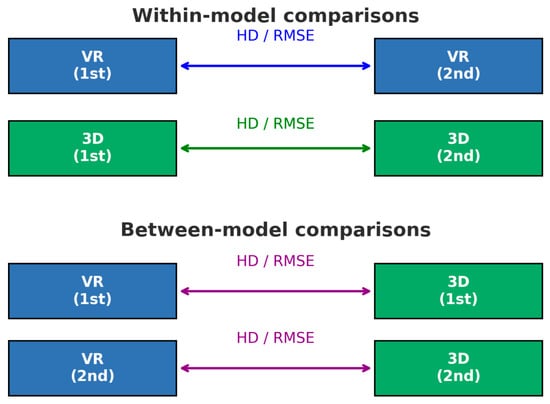

For shape similarity analysis, the Hausdorff distance (HD) and root mean square error (RMSE) were calculated using CloudCompare v2.14 alpha software (EDF R&D, Paris, France). Contours extracted in ImageJ were imported into CloudCompare as point-cloud data. To equalize point density, the contour with the larger number of points was randomly down-sampled using the “Subsample” function. The two contours were then spatially aligned by matching their centroid positions (Registration → Match bounding box centers). After alignment, point-to-point distances between corresponding points were computed using the “Distance” tool. All exported point-to-point distance values were then used to manually calculate HD and RMSE. Intra-examiner comparisons included within-model evaluations (first vs. second VR trials and first vs. second 3D trials) and between-model evaluations (first VR vs. first 3D trials and second VR vs. second 3D trials) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of within-model and between-model shape-similarity comparisons. Hausdorff distance and root mean square error were calculated to assess shape similarity. Within-model comparisons evaluated the reproducibility within each modality for each examiner, that is, virtual reality (VR)-based (1st vs. 2nd) and three-dimensional (3D) printed (1st vs. 2nd). Between-model comparisons were used to assess the agreement between the VR- and 3D-printed implants created in the same trial sequence. VR, virtual reality; 3D, three-dimensional; HD, Hausdorff distance; RMSE, root mean square error.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations. The time required for implant shaping using 3D-printed and VR-based models was compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The Shapiro–Wilk W test was used to assess normality and confirm that the data for the major axis length, minor axis length, area, and depth followed a normal distribution. Intra-examiner reproducibility of the major axis length, minor axis length, area, and depth was evaluated using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). Inter-examiner reproducibility for VR-based and 3D print-based implants was also assessed using the ICC. The HD and RMSE between VR-based and 3D print-based implants were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. For each model, the first and second trials were averaged, and agreement between the two methods was analyzed using Bland–Altman plots, with limits of agreement (LOA) set to mean ± 1.96 standard deviations. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated for the associations of the major axis length, minor axis length, depth, and area between the 3D- and VR-based implants. the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare parameters between the two models. All analyses were performed using SPSS software v30 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The study population comprised 11 patients with unilateral orbital floor fractures. No cases met the exclusion criteria. Patient demographics and defect characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

3.1. Implant Shaping Time

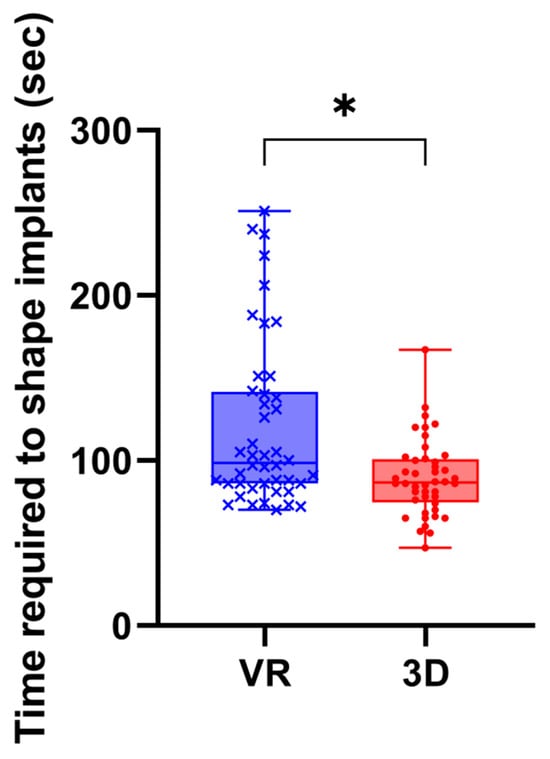

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that implant shaping using 3D-printed models required significantly less time than shaping using VR-based models (89.3 ± 23.1 s vs. 120.3 ± 51.0 s, p < 0.0001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Time required for implant shaping using 3D-printed and VR-based models. Time required to shape implants using 3D-printed and VR-based models. Each point represents a single trial (n = 88). Implant shaping was significantly faster with 3D-printed models than with VR-based models (p < 0.0001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). *, p < 0.0001; VR, virtual reality models; 3D, three-dimentional printed models.

3.2. Evaluation of Intra-Examiner Reliability Between Both Examiners on 3D-Printed and VR Models

The intra-examiner ICCs for both examiners are summarized in Table 2. All parameters showed excellent repeatability for both the 3D-printed and VR models, except for depth in the VR model, which demonstrated a lower agreement.

Table 2.

Intra-rater intraclass correlation coefficients for dimensional measurements.

For shape similarity, intra-rater comparisons of the first and second trials yielded mean HD and RMSE values of 2.64 ± 0.85 mm and 1.02 ± 0.42 mm for the 3D model, and 3.14 ± 1.18 mm and 1.24 ± 0.53 mm for the VR model, respectively. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed no significant differences between the two models for either the HD (p = 0.192) or RMSE (p = 0.154).

3.3. Evaluation of Inter-Rater Reliability Between Both Models on 3D-Printed and VR Models

The inter-rater ICCs are presented in Table 3. Both models demonstrated ICC values of 0.80 or higher for the area, long axis, and short axis, whereas depth showed markedly lower values.

Table 3.

Inter-rater intraclass correlation coefficients for dimensional measurements.

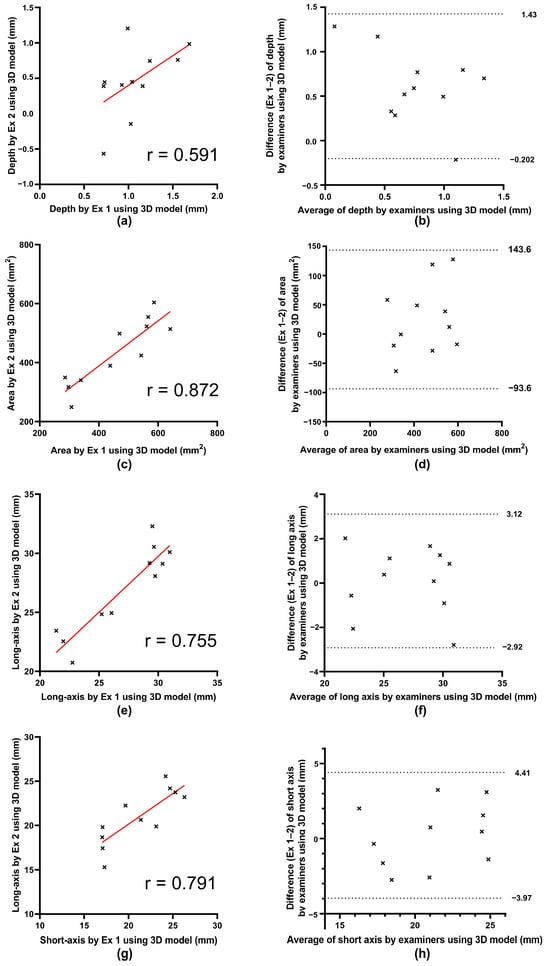

3.4. Evaluation of Inter-Examiner Agreement and Correlation Between Both Examiners on 3D-Printed Models

For the 3D-printed models, the correlation coefficients were 0.550 for depth, 0.888 for area, 0.914 for the long axis, and 0.816 for the short axis. Paired t-tests comparing the mean values obtained by Examiners 1 and 2 showed no significant differences in area, long axis, and short axis, whereas depth demonstrated a significant difference between examiners (Figure 5, Table 4).

Figure 5.

Scatter plots and Bland–Altman plots between both examiners on three-dimensional data of depth, area, long axis, and short axis distance. (a,c,e,g) Scatter plots comparing measurements obtained by Examiner 1 and Examiner 2 using three-dimensional model for depth, area, long axis, and short axis, respectively. The straight red lines represent the regression lines. X-axis: Measurements by Examiner 1. Y-axis: Measurements by Examiner 2. Correlation coefficients (r) are shown for each parameter; all regression coefficients were significant except for depth. (b,d,f,h) Bland–Altman plots for depth, area, long axis, and short axis, respectively. The dotted lines represent the upper and lower limits of agreement, defined as the mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviation. X-axis: Average of the two examiners’ measurements. Y-axis: Difference (Examiner 1–Examiner 2). 3D, three-dimensional; Ex, examiner.

Table 4.

Inter-examiner agreement on three-dimensional printed models.

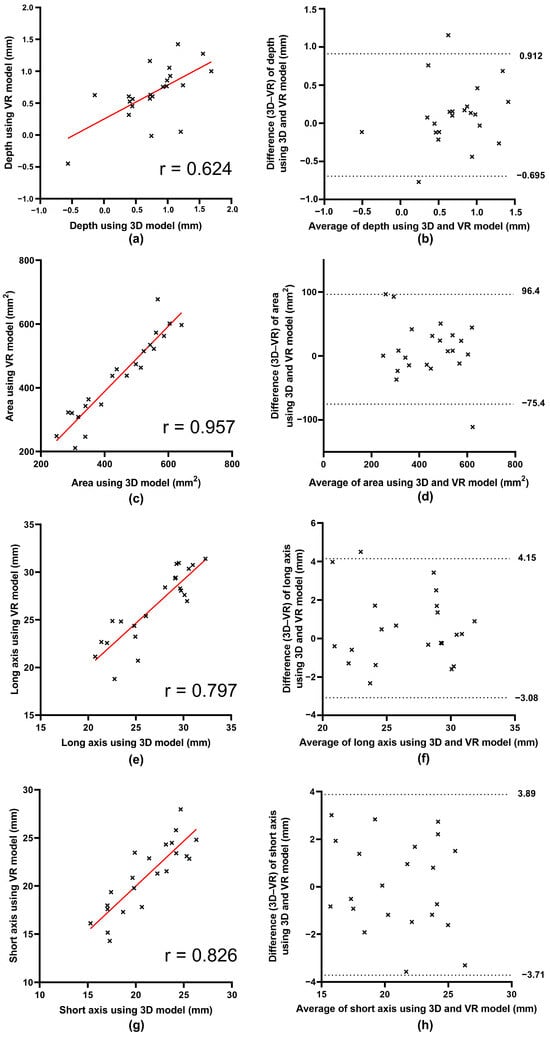

3.5. Evaluation of Agreement and Correlation Between 3D-Printed and VR Models

A comparison of the 3D-printed and VR models showed correlation coefficients of 0.635 for depth, 0.942 for area, 0.876 for the long axis, and 0.852 for the short axis. Paired t-tests comparing the mean values obtained from the two models indicated no significant differences in the depth, area, long axis, or short axis (Figure 6, Table 5).

Figure 6.

Scatter plots and Bland–Altman plots between three dimensions and virtual reality data of depth, area, long axis, and short axis distance. (a,c,e,g) Scatter plots comparing measurements on three-dimensional (3D) printed models and virtual reality (VR) models for depth, area, long axis, and short axis, respectively. The straight red lines represent the regression lines. X-axis: Measurements on 3D-printed models. Y-axis: Measurements on VR models. Correlation coefficients (r) are shown for each parameter, and all were statistically significant. (b,d,f,h) Bland–Altman plots for depth, area, long axis, and short axis, respectively. The dotted lines represent the upper and lower limits of agreement, defined as the mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviation. X-axis: Average of the 3D-printed and VR measurements. Y-axis: Difference (3D-printed–VR). 3D, three-dimensional; VR, virtual reality.

Table 5.

Summary of all dimensional metrics and inter-rater reliability (three-dimensional vs. virtual reality).

Between the 3D-printed and VR models, the mean HD was 2.95 ± 0.94 mm, and the mean RMSE was 1.28 ± 0.49 mm (Table 6).

Table 6.

Summary of Shape Similarity.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that preoperative implant pre-shaping using VR models generated on an NED provided accuracy and reproducibility comparable to conventional 3D-printed anatomical models. With respect to reproducibility, the intra-rater analyses showed high intra-rater ICCs for the area, long axis, and short axis in both modalities, indicating that each examiner was able to reproduce these measurements consistently across repeated trials. Depth also demonstrated a high intra-rater ICC in the 3D model, but lower values in the VR model. Intra-rater reproducibility was further supported by shape similarity analyses. Comparisons between the first and second trials demonstrated mean HD and RMSE, which respectively represent the maximum and average point-to-point deviations between two 3D surfaces, values of 2.64 ± 0.85 mm and 1.02 ± 0.42 mm for the 3D model, and 3.14 ± 1.18 mm and 1.24 ± 0.53 mm for the VR model, with no significant differences between modalities. Inter-rater ICCs also showed strong reproducibility for area and axis measurements in both modalities, whereas depth again demonstrated lower values. These findings indicate that, in addition to depth measurements, both 3D-printed and VR models provide reliable reproducibility across repeated trials and between examiners. In terms of agreement, when the 3D-printed and VR models were directly compared, no significant differences were found in the mean values of the depth, area, long axis, or short axis. The depth showed a relatively low correlation, whereas other parameters showed a high correlation between the two modalities. Shape similarity analyses further supported this agreement: the between-model comparison yielded mean HD and RMSE values of 2.95 ± 0.94 mm and 1.28 ± 0.49 mm, respectively.

Previous studies have shown that using 3D-printed anatomical models to facilitate preoperative implant pre-shaping in orbital floor reconstruction improves orbital volume accuracy and reduces operative time compared to conventional intraoperative freehand shaping [7,8,9]. However, 3D printing requires additional costs and fabrication time, potentially delaying surgical scheduling.

However, few studies have explored the use of VR models in this context, and direct comparisons with 3D-printed models remain limited [20,21]. This study evaluated implant pre-shaping using an NED VR display alongside conventional 3D-printed models, highlighting the feasibility of VR as an alternative pre-shaping tool.

In this study, no formal training session was conducted before the VR-based preshaping task. This was based on previous work using the same NED system, which demonstrated that the device requires only simple drag-based manipulation and enables intuitive stereoscopic visualization without a learning curve [17]. In addition, this report showed that accuracy was maximized when the device was used in a seated position at a viewing distance of approximately 30–50 cm—the same posture adopted in the present study.

In this study, intra-rater ICCs were high for the area, long axis, and short axis in both the 3D-printed and VR models, indicating consistent reproducibility across trials. This finding was supported by the shape similarity analysis, in which intra-rater comparisons of HD and RMSE yielded mean values of 2.64 ± 0.85 mm and 1.02 ± 0.42 mm for the 3D model, and 3.14 ± 1.18 mm and 1.24 ± 0.53 mm for the VR model, with no significant differences between modalities. These results are consistent with the high intra-rater ICCs observed for both modalities, supporting the hypothesis that VR-based pre-shaping provides reproducibility comparable to that of 3D-printed models. In contrast, depth measurements demonstrated a lower intra-rater reliability. Notably, the intra-rater ICC for depth in the VR model was low, and its confidence interval included negative values, indicating poor reliability. This contrasts with the consistently high ICCs observed for area and axis measurements. The instability of depth assessment likely reflects the inherent difficulty in identifying the deepest point of the implant and suggests that depth measurements should be interpreted with caution. One possible explanation for this is that shaping the convexity of an implant relies on tactile feedback. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of tactile perception in evaluating curvature and depth during implant contouring, noting that the absence of haptic feedback can impair the ability to judge subtle convexity [9,22,23]. Moreover, several investigations have reported that depth and surface curvature are inherently more difficult to perceive in virtual environments than in real space, even under stereoscopic viewing conditions [24,25]. While 3D-printed models allow examiners to directly palpate the bony defect and gauge the implant depth, VR models lack this haptic component, which may contribute to reduced reproducibility.

In contrast, depth showed lower inter-rater reliability. In the 3D-printed models, the intra-rater ICCs for depth were high, indicating that each examiner consistently reproduced their own assessment of implant convexity. However, the inter-rater ICCs for depth were low, suggesting that Examiners 1 and 2 did not necessarily agree on the optimal depth. This pattern implies that reduced inter-rater reliability reflects examiner-dependent variation rather than a limitation of the modality itself. Previous reports have described differing opinions regarding the ideal implant contour; some studies advocate a flatter implant configuration that does not fully reproduce the natural curvature of the orbital floor, while others recommend anatomically precise reconstruction. Commercially available preformed implants based on the flat design concept have also demonstrated favorable outcomes. These inconsistencies in the definition of “appropriate depth” likely contributed to the examiner-dependent variations observed in the present study [26,27]. Moreover, because depth measurements were on a much smaller numerical scale than area or axis parameters, they were more susceptible to the influence of minor measurement deviations. Although a height gauge was used to standardize assessment, slight variations during probe placement may have affected the recorded values. Accordingly, part of the reduced reliability in depth may reflect methodological limitations rather than true differences in implant geometry.

In this study, both examiners were experienced plastic surgeons who performed implant pre-shaping using 3D-printed models that can be regarded as a reference standard. Thus, all 3D-based implants represented the “correct” configurations derived by two qualified experts. When these two sets of reference implants were compared, the Bland–Altman analysis revealed a difference in LOA of 1.63 mm for the depth, 237.22 mm2 for the area, 6.04 mm for the long axis, and 8.46 mm for the short axis. In Bland–Altman analysis, the ΔLOA represents the width between the upper and lower limits of agreement and reflects the expected range within which approximately 95% of repeated measurements will fall. A narrower ΔLOA indicates higher agreement, whereas a wider ΔLOA suggests greater variability between measurements. In the context of this study, these values indicate that even when using 3D-printed models, which represent an established reference standard for orbital floor reconstruction, inter-examiner differences of approximately 1.63 mm in depth, 237.22 mm2 in area, 6.04 mm in long-axis length, and 8.46 mm in short-axis length can naturally occur. Because 3D-printed model-based preshaping is already regarded as a clinically accepted method, this degree of variability reflects the range of contour differences that is generally considered acceptable in real-world implant fabrication. Previous studies have similarly reported that even among experienced surgeons, implant shapes and contours for identical orbital fractures can vary depending on individual perception and intraoperative judgment [4,6,9,22,23,26,27].

When comparing the VR and 3D models, the LOA difference for area (171.7 mm2) and short axis (7.6 mm) was smaller than that of the variability between reference standards, indicating high consistency between methods. In contrast, the difference in the LOA for the long axis (7.2 mm) exceeded that of the 3D inter-examiner analysis, suggesting a slightly lower agreement in this dimension. The agreement for depth could not be reliably interpreted because inter-rater ICCs were low for this parameter in both modalities, suggesting that depth determination is inherently variable regardless of the method used.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that VR-based pre-shaping using an NED provides dimensional agreement with 3D printing for most parameters, particularly for contour-related measures such as area and short axis, although precision in depth determination remains limited. Although no previous studies have directly compared implant pre-shaping between VR and 3D-printed models, several reports have shown that measurable discrepancies are inherently present, even in conventional workflows. During the process of converting CT data into 3D-printed skull models, dimensional errors with an RMSE of up to approximately 1.0 mm have been reported [28]. Moreover, despite the use of advanced registration and tracking techniques, intraoperative navigation systems typically show deviations of approximately 1 mm between the planned and actual insertion points [29,30,31]. These observations indicate that small geometric discrepancies are unavoidably introduced during both the model-creation process and intraoperative execution, and such variation is already tolerated in routine craniofacial reconstruction.

When comparing the two modalities, the difference in LOA for the long axis measured 7.2 mm, which was approximately 1 mm greater than the variability observed between the 3D-based reference standards (6.04 mm). In terms of shape similarity, the implants demonstrated a HD of 2.95 ± 0.94 mm and a RMSE of 1.28 ± 0.49 mm. These values are comparable to the dimensional deviations known to occur during CT-to-model conversion and during intraoperative handling in conventional 3D-guided craniofacial reconstruction, as reported in previous studies [28,29,30,31]. Additionally, given that the bony orbital volume is approximately 25 cm3 in adults and that the thickness of commonly used orbital implants is around 0.5 mm, geometric discrepancies of a few millimeters are unlikely to exert a substantial influence on postoperative orbital volume [32].

Moreover, orbital floor implants do not have a single objectively “correct” shape. Previous reports have shown that implant contouring is inherently surgeon-dependent, with different surgeons selecting different shapes for the same defect [4,6,9,22,23,26,27]. This tendency was also reflected in our own findings: even when working from the same 3D-printed reference model, the two experienced examiners produced implants that differed by an HD of 2.64 ± 0.85 mm and an RMSE of 1.02 ± 0.42 mm. Clinically, orbital implants only need to satisfy two essential requirements: they must be large enough to fully cover the bony defect, and sufficiently small and thin to allow safe insertion without causing impingement. The dimensional differences observed between VR-based and 3D-based implants in this study did not interfere with either of these requirements. Although further clinical validation is warranted, the geometric discrepancies identified here are unlikely to impede the practical applicability of NED-based preshaping in orbital reconstruction.

In addition to geometric accuracy, workflow efficiency is an important consideration. In this study, implant shaping was significantly faster using 3D-printed models than using NED-based VR models (89.3 ± 23.1 s vs. 120.3 ± 51.0 s, p < 0.0001). Thus, VR-based shaping required approximately 30 s longer per implant, which represents a clear drawback of the VR approach compared with conventional 3D-printed models. In the context of model fabrication time and cost, previous reports have shown that in-house 3D-printed skull models are faster and less expensive to produce than industry-printed models; however, even in-house fabrication typically requires 4.65–7.18 h and costs approximately USD 236 on average [10]. In contrast, VR models generated on an NED can be created instantaneously from CT data at essentially no additional cost. Given these considerations, the negligible fabrication time and cost associated with NED-based modeling help offset the approximately 30-s delay in implant shaping, suggesting that this drawback is unlikely to meaningfully affect the overall workflow.

This study had some limitations. First, although the study demonstrated no statistically significant differences between the VR and 3D-printed models, the current sample size was small, which limits the statistical power, and the study design did not meet the requirements of a formal non-inferiority framework. As such, the results should not be interpreted as evidence that VR performs equivalently to 3D printing. Nevertheless, no significant evidence indicates that 3D printing is superior to VR-based pre-shaping for any of the evaluated parameters. All results should be regarded as preliminary and exploratory, and further validation in larger and more diverse cohorts is required before drawing definitive conclusions. Second, the evaluation focused primarily on geometric accuracy; factors such as operative efficiency, user fatigue, and learning curves associated with NED use were not quantitatively assessed. Moreover, although the order of presentation was randomized and a one-week interval was introduced between trials to reduce recall bias, learning or sequence effects cannot be fully excluded due to the limited sample size and repeated shaping tasks. Third, although the present findings suggest that NED-based pre-shaping may offer a cost- and time-effective alternative to 3D-printed modeling, further studies involving larger cohorts, diverse examiners, and clinical outcome evaluations are warranted to confirm its practical applicability. To this end, we plan to conduct a prospective clinical study applying this method to orbital reconstruction. The present investigation serves as a preliminary step toward this goal.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that virtual implant pre-shaping using an NED achieved geometric reproducibility and dimensional agreement comparable to those of conventional 3D-printed anatomical models. VR-based pre-shaping showed high reliability for contour-related parameters, such as area and axis dimensions, whereas depth determination remained limited, likely due to the absence of tactile feedback. Given its potential to reduce both the preparation time and material costs, NED-based pre-shaping is a promising and practical alternative to conventional 3D printing for preoperative planning in orbital reconstruction. However, because this study was preliminary and included a limited number of cases, further clinical validation is required before NED-based preshaping can be considered a substitute for conventional 3D-printed models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.; methodology, M.T.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, I.Y. and S.T.; data curation, I.Y. and S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, M.T.; visualization, M.T.; supervision, R.A.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant/Award Number: 23K09110).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Defense Medical College on 1 October 2024 (protocol code 5076).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30565574.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficients |

| NED | Naked-eye stereoscopic display |

| LOA | Limits of agreement |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HD | Hausdorff distance |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| STL | Stereolithography |

References

- Omura, K.; Nomura, K.; Okushi, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Otori, N. Endoscopic Endonasal Orbital Floor Fracture Repair With Mucosal Preservation to Reinforce the Fractured Bone. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 32, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.C.; Shipchandler, T.Z.; Ting, J.Y.; Nesemeier, B.R.; Geng, J.; Camp, D.A.; Lee, H.B.H. Ocular motility and diplopia measurements following orbital floor fracture repair. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, S.; Yokota, H.; Naito, M.; Vaidya, A.; Kakizaki, H.; Kamei, M.; Takahashi, Y. Pressure Onto the Orbital Walls and Orbital Morphology in Orbital Floor or Medial Wall Fracture: A 3-Dimensional Printer Study. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2023, 34, e608–e612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Kim, Y.; Ngo, Q. Orbital Remodeling and 3-dimensional Printing in Delayed Orbital Floor Fracture Reconstructions. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2025, 13, e6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, L.; Sawicki, N.; Sobti, N.; Swartz, S.; Rao, V.; Woo, A.S. Re-evaluating the Timing of Surgery after Isolated Orbital Floor Fracture. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2023, 11, e4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, A.; Yamanaka, Y.; Rajak, S.N.; Nakayama, T.; Ueda, K.; Sotozono, C. Assessment of a Consecutive Series of Orbital Floor Fracture Repairs With the Hess Area Ratio and the Use of Unsintered Hydroxyapatite Particles/Poly l-Lactide Composite Sheets for Orbital Fracture Reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Elgalal, M.; Piotr, L.; Broniarczyk-Loba, A.; Stefanczyk, L. Treatment with individual orbital wall implants in humans-1-Year ophthalmologic evaluation. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2011, 39, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, R.; Malinska, M.; Kozakiewicz, M. Classical versus custom orbital wall reconstruction: Selected factors regarding surgery and hospitalization. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerer, R.M.; Gellrich, N.C.; von Bulow, S.; Strong, E.B.; Ellis, E., 3rd; Wagner, M.E.H.; Sanchez Aniceto, G.; Schramm, A.; Grant, M.P.; Thiam Chye, L.; et al. Is there more to the clinical outcome in posttraumatic reconstruction of the inferior and medial orbital walls than accuracy of implant placement and implant surface contouring? A prospective multicenter study to identify predictors of clinical outcome. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2018, 46, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lor, L.S.; Massary, D.A.; Chung, S.A.; Brown, P.J.; Runyan, C.M. Cost Analysis for In-house versus Industry-printed Skull Models for Acute Midfacial Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2020, 8, e2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuno, D.; Ueda, K.; Itamiya, T.; Nuri, T.; Otsuki, Y. Intraoperative Evaluation of Body Surface Improvement by an Augmented Reality System That a Clinician Can Modify. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Tosevska, A.; Klager, E.; Eibensteiner, F.; Laxar, D.; Stoyanov, J.; Glisic, M.; Zeiner, S.; Kulnik, S.T.; Crutzen, R.; et al. Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Medicine: Analysis of the Scientific Literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, B.; Bopp, M.; Saß, B.; Pojskic, M.; Voellger, B.; Nimsky, C. Spine Surgery Supported by Augmented Reality. Glob. Spine J. 2020, 10 (Suppl. 2), 41S–55S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condino, S.; Turini, G.; Parchi, P.D.; Viglialoro, R.M.; Piolanti, N.; Gesi, M.; Ferrari, M.; Ferrari, V. How to Build a Patient-Specific Hybrid Simulator for Orthopaedic Open Surgery: Benefits and Limits of Mixed-Reality Using the Microsoft HoloLens. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018, 2018, 5435097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pladere, T.; Luguzis, A.; Zabels, R.; Smukulis, R.; Barkovska, V.; Krauze, L.; Konosonoka, V.; Svede, A.; Krumina, G. When virtual and real worlds coexist: Visualization and visual system affect spatial performance in augmented reality. J. Vis. 2021, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eye-Sensing Light Field Display. Available online: https://www.sony.com/en/SonyInfo/technology/stories/LFD/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Ariwa, M.; Itamiya, T.; Koizumi, S.; Yamaguchi, T. Comparison of the Observation Errors of Augmented and Spatial Reality Systems. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, R.; Nakano, A.; Kawanishi, N.; Hoshi, N.; Itamiya, T.; Kimoto, K. Abutment Tooth Formation Simulator for Naked-Eye Stereoscopy. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukuda, T.; Mutoh, N.; Nakano, A.; Itamiya, T.; Tani-Ishii, N. Study of Root Canal Length Estimations by 3D Spatial Reproduction with Stereoscopic Vision. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubron, K.; Verbist, M.; Jacobs, R.; Olszewski, R.; Shaheen, E.; Willaert, R. Augmented and Virtual Reality for Preoperative Trauma Planning, Focusing on Orbital Reconstructions: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimov, C.R.; Aliyev, D.U.; Rahimov, N.R.; Farzaliyev, I.M. Mixed Reality in the Reconstruction of Orbital Floor: An Experimental and Clinical Evaluative Study. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 12, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamer, L.; Noser, H.; Schramm, A.; Hammer, B. Orbital form analysis: Problems with design and positioning of precontoured orbital implants: A serial study using post-processed clinical CT data in unaffected orbits. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 39, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podolsky, D.J.; Mainprize, J.G.; Edwards, G.P.; Antonyshyn, O.M. Patient-Specific Orbital Implants: Development and Implementation of Technology for More Accurate Orbital Reconstruction. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozzacchi, C.; Volcic, R.; Domini, F. Grasping lacks depth constancy in both virtual and real environments. J. Vis. 2015, 15, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Cho, B.; Masamune, K.; Hashizume, M.; Hong, J. An effective visualization technique for depth perception in augmented reality-based surgical navigation. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2016, 12, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiga, A.; Mitsukawa, N.; Yamaji, Y. Reconstruction using ‘triangular approximation’ of bone grafts for orbital blowout fractures. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoor, P.; Mesimaki, K.; Lindqvist, C.; Kontio, R. The use of anatomically drop-shaped bioactive glass S53P4 implants in the reconstruction of orbital floor fractures—A prospective long-term follow-up study. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusseldorp, J.K.; Stamatakis, H.C.; Ren, Y. Soft tissue coverage on the segmentation accuracy of the 3D surface-rendered model from cone-beam CT. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consorti, G.; Monarchi, G.; Catarzi, L. Presurgical Virtual Planning and Intraoperative Navigation with 3D-Preformed Mesh: A New Protocol for Primary Orbital Fracture Reconstruction. Life 2024, 14, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbist, M.; Dubron, K.; Bila, M.; Jacobs, R.; Shaheen, E.; Willaert, R. Accuracy of surgical navigation for patient-specific reconstructions of orbital fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, C.L.; Shi, Y.L.; Jia, J.Q.; Ding, M.C.; Chang, S.P.; Lu, J.B.; Chen, Y.L.; Tian, L. A retrospective study to compare the treatment outcomes with and without surgical navigation for fracture of the orbital wall. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrades, P.; Cuevas, P.; Hernández, R.; Danilla, S.; Villalobos, R. Characterization of the orbital volume in normal population. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 46, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).