Abstract

The rapid development of large artificial intelligence (AI) models—large language models (LLMs), multimodel large language models (MLLMs) and vision–language models (VLMs)—has enabled instruction-driven visual understanding, where a single foundation model can recognize and localize arbitrary objects from natural-language prompts. However, predictions from individual models remain inconsistent—LLMs hallucinate nonexistent entities, while VLMs exhibit limited recall and unstable calibration compared to purpose-trained detectors. To address these limitations, a new paradigm termed “multiple large AI model’s consensus” has emerged. In this approach, multiple heterogeneous LLMs, MLLMs or VLMs process a shared visual–textual instruction and generate independent structured outputs (bounding boxes and categories). Next, their results are merged through consensus mechanisms. This cooperative inference improves spatial accuracy and semantic correctness, making it particularly suitable for generating high-quality training datasets for fast real-time object detectors. This survey provides a comprehensive overview of the large multi-AI model’s consensus for object detection. We formalize the concept, review related literature on ensemble reasoning and multimodal perception, and categorize existing methods into four frameworks: prompt-level, reasoning-to-detection, box-level, and hybrid consensus. We further analyze fusion algorithms, evaluation metrics, and benchmark datasets, highlighting their strengths and limitations. Finally, we discuss open challenges—vocabulary alignment, uncertainty calibration, computational efficiency, and bias propagation—and identify emerging trends such as consensus-aware training, structured reasoning, and collaborative perception ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, object detection has undergone a remarkable transformation—from handcrafted feature pipelines to deep convolutional networks, passing through region-based two-stage and one-stage models, anchor-free detectors, and, most recently, transformer-based architectures and open-vocabulary models. In parallel, the semantic scope of detectors evolved, initially limited to closed-vocabulary models; recently, they no longer operate over fixed class lists but can respond to arbitrary natural-language descriptions. The emergence of large language models (LLMs), multimodal large language models (MLLMs), and vision–language models (VLMs) has further blurred the line between perception and reasoning, introducing a new era of instruction-driven visual understanding [1,2,3,4,5].

Models such as GPT-4V (GPT-4 with Vision), LLaVA-Next (Large Language and Vision Assistant—Next), Qwen-VL (Qwen Vision–Language), and InternVL (Intern Vision–Language) demonstrate that a single foundation model can jointly interpret text and images, recognize novel objects, and even produce structured outputs such as bounding boxes or segmentation masks from natural-language prompts. However, despite their versatility, individual models remain imperfect. They are prone to hallucination—reporting non-existent objects—and to omissions, missing small or rare categories [6]. VLMs also exhibit limited recall and unstable calibration compared with dedicated detectors [7]. This variability highlights a persistent challenge in foundation-model perception: the lack of consistency and reliability across diverse visual contexts.

A promising direction to overcome these limitations is to combine multiple large models into a cooperative system that reaches agreement through structured reasoning and data fusion. Instead of relying on a single large AI model, LLM, VLM or MLLM, several models process the same image and prompt in parallel, each producing an independent prediction in a standardized format—typically a list of objects, bounding boxes, and confidence scores. These structured outputs are then merged using consensus algorithms such as Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) [8], Agglomerative Late Fusion Algorithm (ALFA) [9], or probabilistic ensembling (ProbEn) [10]. The result is a unified detection map that aggregates the complementary strengths of individual models while suppressing hallucinated or inconsistent results.

This general paradigm, referred to here as large multi-AI models’ consensus, extends classical ensemble learning into the image domain. It leverages model diversity, differences in architecture, pre-training data, and reasoning style to improve robustness, interpretability, and trustworthiness. Analogous to ensemble methods in traditional machine learning, consensus among independent LLMs can reduce variance, correct individual biases, and increase calibration reliability. Consensus in multimodal settings operates across both linguistic and spatial dimensions: models must agree not only on what objects are present but also on where they are located.

The motivation for this survey is twofold. First, it aims to systematically review the growing body of research that explores how multiple LLMs and VLMs can collaborate to achieve more accurate and semantically grounded object detection. Secondly, its goal is to establish a unified conceptual and methodological framework that bridges reasoning-level agreement and detection-level fusion.

This paper makes the following contributions:

- Conceptual unification. We formalize the notion of Multi-LLM Consensus for object detection and relate it to ensemble and consensus learning traditions in artificial intelligence.

- Comprehensive taxonomy. We categorize existing consensus paradigms into prompt-level, reasoning-to-detection, box-level, and hybrid designs, linking them with representative algorithms such as MoA (Mixture of Agents) [11], LLM-Blender (Ensembling Large Language Models with Pairwise Ranking and Generative Fusion) [12], DetGPT [13], and ContextDET [14].

- Survey of fusion algorithms. We summarize data fusion techniques—including NMS (Non-Maximum Suppression), Soft-NMS, WBF, ALFA, and ProbEn—and discuss how they extend to multimodal, reasoning-guided detection.

- Evaluation framework. We outline appropriate datasets, metrics, and benchmarks for assessing consensus-based systems, emphasizing calibration, hallucination reduction, and inter-agent diversity.

- Challenges and outlook. We identify key open problems: vocabulary alignment, calibration, efficiency, and bias—and highlight emerging research trends such as consensus-aware training and collaborative perception ecosystems.

The comparison of known surveys is presented in Table 1. Compared to the others, our survey is the first systematic survey on multi-LLM/VLM consensus for object detection. It introduces 4-level taxonomy, emphasizes the mapping from the text-domain LLM-ensemble literature to the detection pipeline, and analyzes the combination of fusion, evaluation, and hallucination calibration issues together.

Table 1.

Horizontal comparison of related surveys and ensemble/fusion works. OV: open-vocabulary detection or grounding; Hall.: hallucination in VLMs/MLLMs; Ens.: LLM/VLM ensemble or multi-agent consensus; Box: box-level fusion or detection-specific ensemble evaluation.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the foundations of object detection, ensemble learning, and vision–language modeling. Section 3 examines LLM-driven detection frameworks such as DetGPT and LLMDet (Learning Strong Open-Vocabulary Object Detectors under LLM Supervision). Section 4 introduces the taxonomy of Multi-LLM Consensus approaches, followed by Section 5, which details data fusion algorithms and implementation strategies. Section 6 presents evaluation protocols and benchmarking practices, and Section 7 outlines challenges and future research directions. Finally, Section 8 concludes with a discussion on the broader implications of consensus-based perception for trustworthy multimodal AI.

2. Background of Object Detection

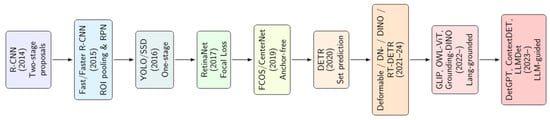

Object detection, the task of locating and classifying objects within an image, has been one of the central challenges of computer vision for over two decades. This field has evolved through several primary stages, each characterized by distinct model architectures and training paradigms. Modern object detection has evolved from region-proposal CNNs to anchor-free and transformer-based methods, and now includes open-vocabulary and language-guided systems. Each stage improved either speed, accuracy, or semantic flexibility. The recent arrival of multimodal foundation models introduces powerful reasoning capabilities but also new challenges in consistency and calibration. Figure 1 summarizes this historical evolution.

Figure 1.

Evolution of deep learning-based object detection.

2.1. Closed Vocabulary Methods

The modern era of deep-learning-based detection began with the Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN) [49]. It decomposes detection into two steps: first, it generates region proposals using a hand-crafted algorithm such as Selective Search, and next, it classifies each proposed region with a CNN. Fast R-CNN [50] introduced Region-of-Interest (ROI) pooling to extract features for all proposals from a shared feature map, dramatically reducing redundancy. Faster R-CNN [51] further unified the pipeline by adding a Region Proposal Network (RPN), which learned to generate candidate regions directly from convolutional features. Later extensions, such as Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN) [52], improved multi-scale reasoning by building hierarchical feature maps, enabling robust detection of both small and large objects.

To further improve inference speed, researchers merged the pipeline into a single pass. YOLO (“You Only Look Once”) [53] and SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector) [54] reframed detection as dense regression: a single network simultaneously predicted bounding boxes and class probabilities across a grid of pre-defined anchor boxes (one-stage detectors). While these models achieved real-time performance, their accuracy initially lagged behind two-stage methods. This gap was closed mainly by RetinaNet [55], which introduced the Focal Loss to mitigate the imbalance between foreground and background samples. Methods like CornerNet [56] detected objects by locating paired keypoints (corners), while CenterNet [57] and FCOS [58] predicted object centers and corresponding box sizes directly, without using anchors.

A significant paradigm shift came with DETR (DEtection TRansformer) [59], which redefined detection as a set-prediction problem using a transformer encoder–decoder architecture. Instead of passing through intermediary steps, DETR directly predicted a fixed-size set of object queries and matched them to ground truth. Its followers: Deformable DETR [60] used sparse attention focused on relevant regions; DN-DETR [61] introduced denoising queries for stable training; DINO [62] refined the query design and optimization strategy; and RT-DETR [63,64] achieved real-time inference without sacrificing accuracy.

2.2. Open Vocabulary and Language-Guided Methods

Detectors, mentioned in the previous section, rely on a closed vocabulary of classes defined prior to actual training. They cannot recognize novel objects beyond that fixed label set. This limitation inspired the development of open-vocabulary detection, which allows models to generalize to unseen categories described by natural language.

The breakthrough enabling this transition was the introduction of contrastive vision–language pretraining in CLIP [65]. Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training (CLIP) jointly trained image and text encoders to align visual and linguistic embeddings, creating a shared semantic space in which textual prompts could represent arbitrary object concepts. Subsequent detectors leveraged this principle by integrating textual conditioning into standard detection architectures.

Among the earliest were Grounded Language-Image Pre-training (GLIP) [66], which unified grounding and detection objectives by aligning region proposals with textual phrases, and OWL-ViT (Open-Vocabulary detection with Vision Transformer) [67,68], which used a Vision Transformer backbone for zero-shot open-vocabulary detection. Grounding-DINO [69,70] extended these ideas, combining a strong objectness prior with text embeddings to achieve state-of-the-art grounding accuracy, while YOLO-World [71] adapted the approach for real-time performance. Table 2 summarizes these systems and their characteristics along with classic approaches.

Table 2.

Comparison of representative object detection models.

The fusion of language and vision naturally led to the emergence of Vision–Language Models (VLMs) and later MLLMs, such as GPT-4V [1], LLaVA-Next [3], Qwen-VL [72], and InternVL [4]. These models combine a visual encoder (often derived from CLIP) with an autoregressive language decoder, enabling them to process images and text jointly. They can describe scenes, answer visual questions, or even produce structured outputs such as JSON bounding boxes through appropriate prompting.

However, while MLLMs demonstrate impressive reasoning capabilities, their predictions can be inconsistent or incomplete [24]. They may hallucinate objects, omit subtle details, or vary across prompt phrasing. This inconsistency motivates the exploration of consensus-based approaches, in which multiple models contribute complementary perspectives that are later reconciled into a unified detection result—a topic further discussed in Section 4 and Section 5.

Open-vocabulary and grounding models such as GLIP, OWL-ViT, and Grounding-DINO play a central role in multi-LLM consensus pipelines because they function as the visual executors that translate LLM-generated reasoning, category lists, or task plans into spatial detections. In multi-agent systems, multiple LLMs first negotiate the semantic content (e.g., phrases, attributes), and the OV detector executes the shared instruction. Therefore, these models form the backbone of the spatial component in later consensus-based designs.

3. LLM-Guided and Reasoning-Driven Object Detection

Classic deep object detectors, as they are not driven by large AI models, work without any textual prompt. They identify all objects that they can detect in the image. Open-vocabulary detectors such as GLIP, OWL-ViT, and Grounding-DINO (see Table 2) already link vision and language through textual prompts. However, their reasoning capability remains limited: they match visual regions to text embeddings but do not understand relationships, context, or complex instructions. For example, a user may want to ask, “Find all objects that could be used for cooking, excluding plates.” Such a request requires logical reasoning and contextual interpretation beyond pure vision-language alignment.

This gap has led to the emergence of LLM-guided object detection—a family of approaches where an LLM interprets or generates structured instructions that direct the detector. Instead of replacing visual encoders, the LLM operates as a high-level planner: it parses natural-language input, deduces what needs to be detected, and produces structured queries or semantic categories for a downstream vision module. This hybrid division of labor mirrors the way humans process scenes, where reasoning is followed by perception.

Text-guided object detection significantly increased object detection capabilities, allowing for querying an image without even mentioning the required image categories. For example, one may ask “Find all objects that may be used to prepare a cheesecake”—a targeted prompt and the detector finds within the image all related objects—necessary food products. On the other hand, text-guided detectors retain the capabilities of detecting all objects, as their predecessors did; one simply needs to use a general prompt, e.g., “Find all objects on the image”.

3.1. LLM-Guided Approaches

DetGPT [13] was among the first systems to formalize this paradigm. It couples an instruction-tuned LLM (such as Vicuna or GPT-4) with a visual detector like Grounding-DINO. The process unfolds in the following two stages:

- The LLM receives a natural-language instruction and interprets it to produce a structured plan—a list of target object types or phrases, possibly with attributes (e.g., “detect red cars,” “count people sitting at a table”).

- The plan is executed by an open-vocabulary detector, which performs localization for each text query and returns bounding boxes and confidence scores.

This design effectively transforms the LLM into a semantic controller that orchestrates the visual backend. Because the LLM can reason about context and task intent, DetGPT generalizes across diverse visual instructions, from generic object finding to compositional reasoning (“find the largest animal near the tree”). Furthermore, it allows flexible integration of multiple detectors, an idea that naturally extends to consensus-based pipelines discussed in Section 4.

ContextDET [14] advances the concept of LLM-driven guidance by injecting textual context directly into the visual decoding process. Instead of treating the LLM and the detector as strictly separate modules, ContextDET enables a two-way information exchange: The LLM generates contextual clues (e.g., “objects likely to appear in a kitchen”) that modulate the attention maps of the visual encoder. This joint optimization improves both precision and recall, especially in cluttered scenes or when object boundaries are ambiguous.

ContextDET also illustrates a broader research direction—contextual grounding—in which linguistic priors constrain spatial predictions. By enriching visual tokens with semantic cues from language, the model learns to focus on relevant regions even in the absence of explicit annotations. The method can operate in zero-shot settings, bridging perception and reasoning in a more interpretable manner.

A related approach, LaMI-DETR (Language-Model-Integrated DETR) [73], explores tighter fusion between transformer-based detection and language understanding. Here, the LLM’s output (for example, parsed query tokens or reasoning traces) is directly incorporated into the transformer decoder as conditioning information. Unlike DetGPT, which sequences reasoning and detection, LaMI-DETR blends them at the feature level: textual embeddings guide object queries through cross-attention. This design yields better performance in compositional reasoning tasks and supports instruction-based detection, where the LLM can modify how the detector prioritizes objects depending on task goals.

LLMDet [74] represents another key step: instead of using an LLM only at inference time, it leverages it during training. The LLM generates pseudo-labels, descriptions, or relational constraints for unlabeled images, effectively augmenting the training data with linguistic supervision. This approach turns LLMs into “data generators” that help detectors learn open-vocabulary associations without explicit human annotation. In practice, LLMDet can train competitive open-vocabulary detectors solely from LLM-synthesized captions and class hierarchies, drastically reducing labeling cost.

Table 2 lists key LLM-driven systems and their design differences. DetGPT and ContextDET rely on inference-time reasoning, whereas LLMDet introduces LLM-based supervision during training. LaMI-DETR, in turn, integrates LLM-derived semantics directly into the detector architecture.

These different approaches illustrate a spectrum of integration strategies. For instance, modularity is maintained by DetGPT and ContextDET, which makes them easy to pair with different open-vocabulary backbones. In contrast, joint learning in LaMI-DETR blurs the line between reasoning and perception, potentially improving performance but at a higher computational cost. Meanwhile, supervision strategies, like those used in LLMDet, demonstrate that LLMs can generate rich supervision signals, aligning vision models with linguistic concepts.

Together, these methods illustrate a spectrum of integration strategies—from loose coupling (LLM as planner) to tight multimodal fusion (shared latent space).

3.2. Evaluation and Challenges

Evaluating reasoning-guided detection involves both standard detection metrics and reasoning-aware benchmarks. Datasets such as RefCOCO (Referring Expressions COCO), RefCOCOg (Referring Expressions COCOg), and Flickr30K Entities (see Table 3) are particularly suited because they test phrase-level grounding rather than fixed labels. Recent multimodal benchmarks, e.g., Multimodal Benchmark (MMBench) [75] and Multimodal Evaluation (MME) [76], also include instruction-based detection and compositional reasoning tasks, allowing unified evaluation of both reasoning accuracy and spatial localization.

Table 3.

Datasets and benchmarks grouped by thematic category, with applicability to prompt-level (P), reasoning-to-detection (R), and box-level (B) consensus.

For quantitative comparison, mAP is typically reported for detection, while reasoning quality is measured via textual agreement or question–answer accuracy. Qualitative visualization of LLM/VLM reasoning chains helps interpret model behavior, revealing whether bounding boxes correspond to the model’s textual justifications.

Despite promising results, detection based on large AI models faces the following obstacles:

- Latency and cost. Running large models like GPT-4V or InternVL in the detection loop is computationally expensive, especially for real-time applications.

- Stability and determinism. LLM outputs vary with temperature sampling and prompt phrasing; inconsistent reasoning leads to inconsistent detections.

- Grounding accuracy. Many LLMs lack explicit spatial understanding and rely on external detectors for localization; this dependency may propagate detector biases.

- Calibration and confidence. Integrating probabilistic outputs from heterogeneous modules (LLM and detector) remains challenging.

Ongoing research explores techniques to mitigate these limitations: structured prompting, reasoning templates, and cross-model’s consensus (discussed in Section 4) can improve both robustness and interpretability.

LLM-guided detection represents a crucial step toward reasoning-aware perception. By combining the contextual understanding of LLMs with the spatial precision of visual detectors, these hybrid systems enable complex, instruction-driven object detection. They also provide the conceptual foundation for Multi-LLM Consensus, where multiple reasoning agents cooperate to produce more reliable and semantically consistent detections—the topic of the next section.

4. Multi-LLM Consensus and Ensemble Reasoning

While individual large language models, or VLMs, can interpret images and produce structured detections, their outputs are often inconsistent. Differences in training data, tokenization, or reasoning style may lead one model to hallucinate an object that another correctly omits. This observation parallels early findings in classical machine learning: combining multiple imperfect models can yield a system more accurate and robust than any single one.

The large multi-AI models’ consensus paradigm extends this principle to reasoning-based vision systems. Here, several LLMs or VLMs receive the same image and prompt, independently generate structured predictions (e.g., lists of objects and bounding boxes), and a consensus mechanism fuses these outputs into a unified result. The process integrates linguistic reasoning, visual perception, and statistical aggregation—effectively merging ensemble learning with multimodal understanding.

Conceptually, multi-AI models’ consensus can occur at different levels of the detection pipeline as follows:

- Prompt-level consensus: models agree on semantic understanding before detection (shared class or phrase lists).

- Reasoning-to-detection consensus: models produce reasoning chains that inform separate detectors.

- Box-level consensus: final spatial outputs (bounding boxes) are merged geometrically or probabilistically.

- Hybrid consensus: combinations of the above stages in a unified, hierarchical pipeline.

These mechanisms are summarized in Table 4, which compares representative frameworks and their properties.

Table 4.

LLM-level consensus methods and their suitability for object-detection pipelines.

4.1. Prompt-Level Consensus

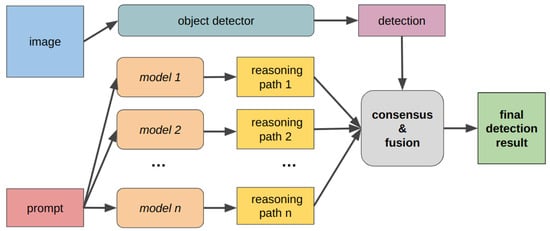

Prompt-level consensus is the most intuitive form: multiple LLMs receive the same task instruction (e.g.,“List and localize all objects on the table” and generate independent textual outputs. The system then reconciles these responses through linguistic aggregation, ensuring semantic consistency before spatial localization that is performed using the classic object detection model. This pipeline can be defined as:

where are image and textual prompt, respectively; stands for the consensus-driven output, —for object detection, and —for n models. The complete pipeline is shown in Figure 2. In this approach, models perform text-only tasks. It implies that they are classic LLMs that do not require training on visual content. They process a textual prompt referring to the content of the image, not images themselves. Each of them outputs the reasoning path that allows us to determine which elements of the image content are important from the perspective of the given prompt. The consensus is performed on such LLMs’ outputs, and the result is combined with object detection that is performed as a separate process.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of prompt-level consensus.

There are several approaches to the consensus and fusion in this case. A simple but effective method, self-consistency [33], generates multiple reasoning paths from the same model and selects the final answer appearing most frequently. Initially designed for textual reasoning, this approach translates naturally to detection: if several reasoning paths predict the same object label or bounding box, that consensus becomes the output. Self-consistency marginalizes stochastic reasoning errors, improving stability with minimal overhead.

The mixture-of-agents (MoA) framework [11] generalizes this idea by involving multiple heterogeneous LLMs (“agents”) instead of multiple samples from one model. Each agent provides a candidate output, and a meta-consensus (often another LLM) integrates them via voting or weighted averaging. This architecture exploits the diversity of models—for instance, pairing GPT-4V (strong reasoning) with InternVL (strong perception) yields richer, complementary predictions.

LLM-Blender [12] takes a generative fusion approach: it first ranks candidate outputs using a separate “Ranker” model and then synthesizes a new answer that combines their strengths. Similarly, the LLM-as-a-Judge paradigm [38] employs a powerful LLM (e.g., GPT-4) to evaluate and score outputs from other models, selecting the most coherent one. Both approaches approximate human-like arbitration, improving factual correctness and readability, though at increased computational cost.

In contrast to static voting, Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) [34,42] allows LLMs to iteratively critique and refine each other’s outputs. Agents engage in dialog, pointing out inconsistencies or omissions until convergence. This process reduces hallucinations and often produces more complete object lists, though it increases latency and requires careful orchestration.

Recent work such as Free-MAD [39] removes explicit coordination, relying on self-organized dialog among agents. LLM-TOPLA [35] instead maximizes diversity among candidate answers before voting, preventing redundant reasoning. Together, these methods demonstrate that reasoning diversity—analogous to ensemble variance—directly correlates with performance gains in consensus systems.

4.2. Reasoning-to-Detection Consensus

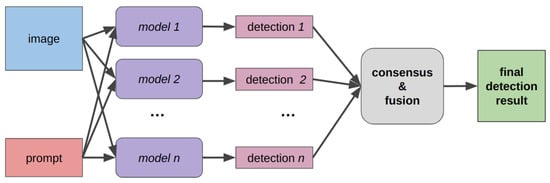

Whereas prompt-level consensus operates in the textual domain, reasoning-to-detection consensus couples linguistic agreement with visual grounding. Here, each large AI model (agent) inputs both the textual prompt and the input image. It performs direct object localization tasks starting from the textual prompt. Finally, fusion of all outputs produces the final detection results (see Figure 3 for the pipeline flowchart). The following equation can formalize the process:

Figure 3.

Flowchart of reasoning-to-detection consensus.

Because both textual and image information make the models’ input, the agents need to be, in this case, the VLM or MLLMs. Each agent produces structured reasoning traces—e.g., a list of object hypotheses or attributes—which are executed by open-vocabulary detectors such as Grounding-DINO or OWL-ViT.

For example, one model might reason, “objects include [car, person, bicycle]”, while another proposes [car, truck, pedestrian]. Consensus mechanisms reconcile these hypotheses into a unified list of detection categories, which then guide the detector to perform localization. This process mirrors the architectures of DetGPT [13] and ContextDET [14] (see Section 3), extended to multi-agent reasoning.

Reasoning-to-detection consensus can be achieved through several methods, including weighted voting on predicted object categories or attributes, union-based fusion of all unique object classes to maximize recall, and confidence calibration—assigning trust weights to each model based on historical accuracy or semantic agreement.

By merging independent reasoning traces, the system can recover missed detections, normalize label synonyms, and reduce hallucinations—achieving better semantic coverage than any single agent.

4.3. Box-Level Fusion Consensus

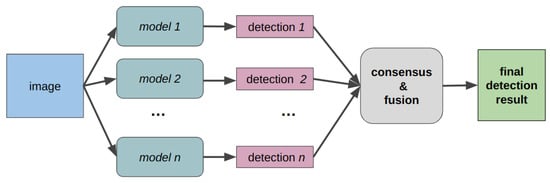

The object detection task is performed either starting from a prompt implying objects that are searched for or without any textual input. In the second case, the model is not targeted towards a particular content—the task is to find ALL image objects. At the final stage of detection, each model outputs bounding boxes with class labels and confidence scores. The models used here are VLMs, with simple prompts like, e.g., “Locate all known objects in an image and represent them in a standardized json format”. Box-level consensus merges these spatial results into a unified detection map, applying well-established ensemble techniques from computer vision. The whole pipeline may be defined as

where the consensus fusion operator refer in this case to bounding-box fusion—see Figure 4 for the flowchart.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of box-level consensus.

On can merge the multiple sets of bounding boxes, obtained by various models in several ways. The simplest method, Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), removes overlapping boxes exceeding a given Intersection-over-Union (IoU) threshold, but it discards valuable information from weaker detections.

More advanced algorithms preserve these details, including WBF [8], which computes a confidence-weighted average of overlapping boxes to produce smoother localization, and ALFA [9], which clusters spatially close boxes and merges them using geometric and semantic similarity. Additionally, Probabilistic Ensembling (ProbEn) [10] models each detection as a spatial probability distribution, merging them through Bayesian inference to estimate uncertainty, while Soft-NMS [47] decays the confidence of overlapping boxes rather than suppressing them entirely.

These techniques, originally designed for ensembling CNN-based detectors, can be directly reused in Multi-LLM Consensus pipelines: once multiple agents produce structured bounding boxes, spatial fusion ensures geometric coherence. This step is especially valuable when different models vary in localization accuracy or calibration.

4.4. Hybrid and Hierarchical Consensus

Real-world consensus frameworks often combine several of the above stages in a hierarchical manner. This process typically starts with prompt-level consensus to align the semantic vocabulary and filter hallucinated classes, followed by reasoning-to-detection consensus, which generates consolidated detection queries. Finally, box-level fusion merges the final spatial predictions from multiple detectors.

Such multi-stage designs have been successfully employed in hybrid architectures that integrate both reasoning diversity and geometric robustness. Recent frameworks like Iterative Consensus Ensemble (ICE) [37] and SkillAggregation [36] extend this idea further: agents iteratively re-ask or cross-validate each other, refining consensus until stable agreement is reached. ICE demonstrates that iterative re-evaluation significantly improves factuality and consistency, while SkillAggregation introduces weighting based on model “skill vectors” learned from prior performance, enabling reference-free trust estimation.

4.5. Scaling and Efficiency

Running multiple large models concurrently introduces substantial cost. Recent studies such as Compound Inference Scaling [40] analyze how performance gains scale with the number of models and calls. They find that improvements follow a diminishing, return pattern—typically saturating beyond 3–5 diverse agents, consistent with classical ensemble theory. Hence, practical systems often limit ensemble size and use parallel inference or adaptive selection strategies to balance accuracy and latency.

Furthermore, the FusionFactory framework [43] proposes unifying multiple LLM capabilities (e.g., reasoning, summarization, planning) by merging their intermediate logs rather than raw outputs. This reduces the need for repeated inference, offering a path toward efficient large-scale consensus.

Scaling the number of agents in multi-LLM/VLM/MLLM systems reveals distinct patterns depending on whether the models are used for complex reasoning and consensus or for late-stage detection fusion. For compound inference systems that aggregate responses from multiple Language Model (LM) calls via voting (Vote) or filtered voting (Filter-Vote), performance as a function of the number of LM calls can exhibit non-monotonic behavior, meaning accuracy may first increase but subsequently decrease [40]. This complexity is theorized to stem from the diversity of query difficulties within a task, where increased calls lead to higher performance on “easy” queries but can lower performance on “hard” ones [40]. To achieve robust performance in multi-agent environments, the emphasis shifts from maximizing the number of agents to optimizing the diversity of their outputs or selecting the best subset, as demonstrated by methods that utilize deep parallel collaboration [44] or multiagent debate [11]. For example, methods like self-consistency aim to select the most consistent answer by sampling a diverse set of reasoning paths, leveraging the intuition that a complex problem typically admits multiple different ways of thinking leading to its unique correct answer [33]. Similarly, the Iterative Consensus Ensemble (ICE) framework operates through a forward-feedback loop, where multiple models exchange explanations and answers until they reach consensus [37].

4.6. Challenges and Research Directions

Large multi-AI models’ consensus represents a natural evolution of ensemble learning, extended into the multimodal domain. By aggregating the reasoning and perception outputs of multiple agents, consensus frameworks achieve greater robustness, semantic coverage, and interpretability. They form the conceptual bridge between LLM-guided detection (Section 3) and data-fusion algorithms (Section 5), establishing the methodological core of collaborative multimodal perception.

While multi-AI models’ consensus improves robustness, it introduces new challenges, most notably vocabulary alignment, where merging outputs with differing lexical forms (e.g., “bike” vs. “bicycle”) requires semantic normalization. Additionally, confidence calibration becomes critical, as combining heterogeneous scores demands robust scaling techniques such as temperature calibration or isotonic regression. Further complexities arise in conflict resolution—specifically the non-trivial task of deciding between mutually exclusive predictions when confidences are uncalibrated—and in efficiency, where high computational costs and synchronization overhead limit deployment in real-time settings.

Addressing these issues may involve consensus-aware training, where models are optimized jointly for agreement rather than isolated accuracy—a direction explored further in Section 7.

5. Data Fusion Algorithms for Detection Consensus

Data fusion algorithms form the computational backbone of large multi-AI model’s consensus frameworks. Their success in object detection ultimately depends on how individual model outputs are combined. Regardless of whether predictions come from classical CNN detectors, transformer-based systems, or LLM-guided reasoning pipelines, all yield structured results—bounding boxes, class labels, and confidence scores—that must be reconciled into a single, coherent detection map. This step is known as data fusion or ensemble fusion. They translate the abstract idea of “agreement among agents” into precise geometric and probabilistic operations. Choosing an appropriate fusion method—balancing accuracy, interpretability, and efficiency—is therefore crucial for deploying reliable consensus-based object detectors.

Historically, the concept originates from ensemble learning in machine learning [83], where multiple predictors are combined to reduce variance and improve generalization. In detection, fusion serves similar goals: (1) increase recall by pooling complementary detections, (2) improve localization by averaging correlated boxes, and (3) enhance calibration by smoothing overconfidence from individual models. Table 4 summarizes major fusion algorithms used in both classical and LLM-based detection.

5.1. Classical Fusion Strategies

The simplest and most widely adopted method is NMS [48]. It removes redundant detections by keeping the highest-confidence box in a cluster of overlapping predictions that exceed a given Intersection-over-Union (IoU) threshold. While computationally efficient, NMS discards valuable information from lower-scoring boxes and may underperform when multiple detectors disagree on precise box positions.

To address these limitations, Soft-NMS [47] replaces hard suppression with confidence decay. Instead of discarding overlapping boxes, it decreases their confidence scores proportionally to IoU overlap:

where is the original confidence and controls decay smoothness. This continuous weighting maintains recall and avoids abrupt score discontinuities, making it especially effective in crowded scenes.

The most influential modern technique is WBF [8]. Rather than eliminating overlapping boxes, WBF computes their weighted average:

where are box coordinates and the confidence scores. By averaging coordinates from all detections with significant overlap, WBF achieves more precise localization and higher mAP than traditional NMS. It became the de facto standard for ensembling heterogeneous detectors.

ALFA [9] generalizes WBF by clustering boxes according to geometric and semantic similarity. ALFA iteratively merges clusters with high IoU and class similarity, computing fused boxes via weighted averaging. This hierarchical approach maintains robustness when fusing outputs from models with varying confidence scales or class ontologies, which is typical in Multi-LLM settings.

ProbEn [10] interprets each detection as a spatial probability density function—typically a 2D Gaussian over box coordinates—and performs Bayesian fusion to estimate the posterior distribution of the actual object location. It yields not only a fused box but also an uncertainty estimate, useful for risk-aware applications such as autonomous driving or medical imaging.

The analysis of consensus algorithms at the box-level consensus stage (late fusion) distinguishes between heuristic filtering and true probabilistic fusion. Traditional suppression algorithms, such as NMS, are filtering mechanisms designed to perform Local Maximum Search by selecting the bounding box with the highest confidence score and then suppressing overlapping predictions, often by setting the scores of redundant boxes to zero. Soft-NMS improves upon this by applying a continuous penalty (e.g., using a linear or Gaussian function) to decay the confidence scores of overlapping detections rather than eliminating them, thereby improving object detection. Conversely, WBF is an algorithmic approach that performs geometric consolidation by calculating a weighted average of bounding box coordinates, where the weights are derived from the detection confidence scores. These methods (NMS, Soft-NMS, WBF) are primarily heuristic and do not strictly preserve probability semantics.

In contrast, ProbEn is derived from Bayesian principles (multiplication of posteriors) and is designed to preserve probability semantics. This method achieves optimal fusion by typically operating in the logit space, effectively summing the logit outputs from multiple detectors to derive a consolidated confidence score, thereby boosting certainty when detectors agree. For geometry fusion, ProbEn models bounding box coordinates as a Gaussian distribution. It determines the final coordinate by calculating a weighted average based on the inverse of the variance (uncertainty) of each prediction. Furthermore, since neural networks often produce over-confident scores, proper score calibration (e.g., necessary for ProbEn) is essential to ensure that the confidence scores accurately reflect the actual probability of correctness before they are probabilistically combined, preventing the amplification of estimation errors during the fusion process.

5.2. Fusion of Heterogeneous Outputs

Large multi-AI models’ consensus often combines outputs from models with heterogeneous formats: some produce exact bounding boxes, others polygons, segmentation masks, or textual object lists converted to coordinates. Ensuring consistent fusion therefore requires three key preprocessing steps:

- Coordinate normalization: mapping all spatial outputs to the same image reference frame and resolution.

- Label harmonization: aligning class names using semantic embeddings (e.g., CLIP text space) to unify synonyms and resolve ambiguities (“bike” vs. “bicycle”).

- Confidence calibration: normalizing scores across models through temperature scaling or isotonic regression to avoid bias toward overconfident agents.

Proper standardization at this stage determines how effective later geometric fusion can be.

5.3. Hierarchical and Multi-Stage Fusion

Modern consensus frameworks rarely rely on a single fusion step. Instead, they employ hierarchical pipelines that merge information at multiple semantic and spatial levels. This process typically begins with semantic fusion, which unifies class vocabularies across reasoning agents before spatial processing, followed by geometric fusion, where algorithms such as WBF or ALFA are applied to merge bounding boxes per class. Finally, confidence fusion combines calibrated confidence scores through weighted averaging or Bayesian posterior computation.

This hierarchy ensures that reasoning agreement constrains spatial aggregation, resulting in more interpretable and stable detections. In practice, multi-stage fusion improves both recall and calibration compared with single-stage alternatives.

5.4. Adaptive and Trust-Weighted Fusion

When models differ in reliability, assigning uniform weights to all of them may be suboptimal. Trust-weighted fusion adjusts model contributions based on empirical or contextual reliability. Each model is assigned a trust coefficient proportional to its past accuracy or semantic agreement with peers:

Trust weights can be computed dynamically during inference—for example, by measuring cross-model agreement on overlapping regions. Recent frameworks such as SkillAggregation [36] learn these weights automatically through meta-optimization, resulting in adaptive consensus that improves over static averaging.

5.5. Uncertainty-Aware and Probabilistic Fusion

A limitation of traditional fusion methods is their deterministic nature: they produce single boxes without uncertainty estimates. In contrast, probabilistic approaches explicitly model uncertainty, representing each detection as a probability distribution. Beyond ProbEn [10], recent works propose Gaussian mixture models or Monte-Carlo fusion, where uncertainty is propagated through all stages of consensus. This is particularly valuable when combining reasoning-based outputs from LLMs, which may have high epistemic uncertainty due to prompt variability.

Visualizing uncertainty, e.g., by overlaying variance maps, helps interpret ambiguous predictions and supports downstream decision-making, such as active learning or human-in-the-loop verification.

5.6. Efficiency Considerations

Data fusion introduces computational overhead, especially when combining thousands of detections per image from multiple agents. Efficient implementations vectorize IoU computation and parallelize clustering on GPUs. Recent toolkits, such as FusionFactory [43], automate the merging of heterogeneous outputs from LLMs and VLMs at scale. Additionally, lightweight approximations of WBF using sparse indexing or confidence pruning can reduce complexity without substantial accuracy loss.

In practice, fusion time typically accounts for less than 5–10% of total inference cost, making it a negligible bottleneck compared with running large foundation models.

5.7. Integration in Multi AI Models’ Consensus Pipelines

In full multi AI models’ systems, fusion serves as the final unification step after semantic and reasoning consensus. The process typically begins with multiple models generating independent structured detections, after which semantic fusion merges their textual outputs into a canonical class list. Subsequently, box-level algorithms—such as WBF, ALFA, or ProbEn—fuse spatial predictions, and finally, confidence calibration combined with uncertainty propagation yields the resulting detection map.

This modular design allows for swapping fusion algorithms depending on specific application needs, such as utilizing WBF for fast and accurate ensembling of similar detectors, employing ALFA for robust cross-model integration, or selecting ProbEn for uncertainty-aware applications.

6. Evaluation and Benchmarking of Consensus-Based Detection

Evaluating consensus-based object detection is fundamentally more complex than evaluating a single detector. In traditional setups, one measures how well a model localizes predefined classes. In multi AI models’ consensus systems, however, predictions arise from multiple heterogeneous agents, often with open vocabularies (OV) and uncalibrated confidence scores. Consequently, performance must be assessed along several dimensions, including spatial accuracy (bounding-box localization), semantic correctness (label or text alignment), calibration and uncertainty, as well as inter-model agreement and robustness. A rigorous evaluation framework is therefore essential for ensuring comparability across different consensus strategies.

6.1. Datasets and Benchmarks

Consensus systems are typically evaluated using a mix of closed- and open-vocabulary benchmarks. Traditional datasets such as Common Objects in Context (COCO) and Pascal VOC (PASCAL Visual Object Classes) remain useful for quantitative baselines, but open-vocabulary and grounding datasets provide richer evaluation signals. See Table 3 for concise presentation of datasets grouped by task with assigned consensus-type.

Datasets LVIS (Large Vocabulary Instance Segmentation) [78] and ODinW/ELEVATER (Object Detection in the Wild/Evaluating Language-Augmented Visual Models) [79] offer large vocabularies and long-tailed distributions, enabling separate evaluation on seen and unseen categories. These datasets are ideal for measuring recall improvements and vocabulary generalization in consensus pipelines.

Datasets RefCOCO, RefCOCO+, andRefCOCOg [80] test whether models can correctly localize entities described by free-form language (e.g., “the person in a red shirt”). Consensus systems are evaluated by how well their fused detections align with textual descriptions across agents.

Recent datasets such as MMBench [75] and MME [76] provide reasoning-intensive tasks that link detection with contextual understanding. They test whether multiple LLMs can collaboratively reason about spatial relations (“find the largest object left of the dog”) and whether consensus improves factual consistency.

For specialized tasks (medical imaging, aerial imagery), datasets like xView, DeepLesion, or BDD100K assess how well consensus generalizes across domains. The key advantage is that fusion can mitigate single-model biases or overfitting to specific image styles.

6.2. Metrics for Spatial Accuracy

The primary measure of detection quality remains mAP computed at multiple IoU thresholds (e.g., 0.5:0.95). mAP summarizes precision–recall trade-offs and directly quantifies localization accuracy. Beyond this primary measure, additional metrics include Average Recall (AR), which assesses sensitivity to object coverage and is useful for consensus ensembles that prioritize recall. Furthermore, IoU consistency evaluates the mean IoU across fused and individual boxes to demonstrate geometric agreement between agents, while the F1-score becomes particularly relevant when detection decisions are binarized for task-specific evaluation [8,13].

Multi-model consensus in object detection and linguistic reasoning systems yields significant and measurable performance gains, which vary based on the stage of fusion. For detector late fusion (box-level consensus), where the outputs of various independent detectors are combined, performance is primarily measured using mean Average Precision (mAP) and Log-Average Miss Rate (LAMR). The WBF method consistently showed superior geometric consolidation, improving mAP substantially over single models; for instance, combining two different EfficientDet models on MS COCO resulted in an increase to 0.5344 mAP (0.5:0.95), relative to the best single model baseline of 0.521 [8]. Similarly, the ProbEn technique significantly enhanced multimodal detection (RGB-Thermal), reducing the LAMR on the KAIST pedestrian detection dataset [10]. The fusion of three models (ProbEn3) achieved a best result of 5.14% LAMR, representing a relative improvement of over 13% compared to the prior state-of-the-art detector GAFF (6.48% LAMR) [10].

In the domain of LLM/VLM/MLLM reasoning and consensus, increasing the number of collaborating agents leads to robust improvements in accuracy by leveraging diverse reasoning paths. The Iterative Consensus Ensemble (ICE) framework, which uses three models to iteratively exchange reasoning, significantly improved performance across complex multiple-choice question (MCQ) datasets. The overall accuracy score for the combined datasets rose from an initial 60.2% to a final consensus score of 74.03% (a 23% relative gain) [37]. This improvement was particularly remarkable on the challenging GPQA-diamond PhD-level reasoning benchmark, where performance jumped from an initial 46.9% to 68.18% at the final consensus. Furthermore, advanced ensemble methods utilizing weighted fusion proved superior to baselines, achieving 72.77% accuracy on the MMLU dataset, surpassing the best individual base model (Mixtral-8x7b) score of 70.53% [12]. However, a gap remains in the literature, as there is currently a lack of systematic empirical studies that quantify the benefits of multi-agent LLM/VLM consensus using traditional object detection metrics such as mAP on open-vocabulary datasets like LVIS or ODinW.

6.3. Metrics for Semantic and Reasoning Quality

Since consensus often involves linguistic reasoning, semantic evaluation is equally important. When agents use different labels (“bicycle” vs. “bike”), cosine similarity in CLIP or Sentence-BERT embedding space can quantify semantic proximity. A consensus detection is deemed correct if its textual label lies within a similarity threshold to the ground-truth description.

Metrics from image captioning and grounding, BLEU, METEOR, or CIDEr, can measure correspondence between generated textual reasoning and localized regions. For referring expression datasets, Referring Expression Accuracy (RefAcc) measures the fraction of expressions localized correctly.

Some benchmarks (e.g., MMBench [75]) include multiple-choice reasoning questions. Here, consensus is evaluated by majority agreement across agents or by whether the fused reasoning chain leads to the correct answer.

6.4. Calibration and Uncertainty Metrics

When fusing predictions from multiple agents, confidence calibration becomes critical, as uncalibrated scores can distort fusion weights and give excessive influence to overconfident models. To quantify calibration quality, researchers commonly use Expected Calibration Error (ECE), which measures the average absolute difference between predicted confidence and empirical accuracy across bins; the Brier Score, which captures overall probabilistic accuracy with lower values indicating better calibration; and Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL), particularly suitable when probabilistic outputs (as in ProbEn [10]) are available. A well-calibrated consensus should produce confidence values that meaningfully reflect correctness probability, thereby improving interpretability for downstream decision-making.

6.5. Agreement and Diversity Measures

A unique property of consensus frameworks is that multiple models can disagree even when all are “partially correct”. Measuring the diversity among agents provides insight into ensemble effectiveness. One way to do this is by analyzing the pairwise disagreement rate, defined as the fraction of detections where two agents differ in label or localization beyond a threshold. Another indicator is the inter-agent IoU, which captures the geometric overlap between agents’ detections—low values suggest complementary localization behavior. A further perspective is given by the entropy of consensus, reflecting the distributional uncertainty over class votes; lower entropy corresponds to stronger agreement.

Empirically, ensemble benefit correlates with diversity: systems with more varied reasoning traces (e.g., different prompt styles or model families) yield higher mAP gains [11,37].

6.6. Hallucination, Robustness, Efficiency and Cost Evaluation

A major advantage of consensus is its ability to reduce hallucination—false detections unsupported by the image. Recent analyses [7,24] show that hallucination frequency can be quantified as:

Consensus typically decreases hallucination rate by suppressing outlier predictions that appear in only one model’s output. Robustness can also be tested through perturbation benchmarks (e.g., image noise, occlusion) to measure how consistently consensus maintains detection quality.

Because large multi-AI models’ consensus involves multiple heavy models, reporting only accuracy is insufficient. Researchers should also measure inference latency (seconds per image), compute cost (GPU-hours or energy usage), and consensus overhead (time spent on fusion and calibration), as well as scaling efficiency, defined as the improvement in accuracy per additional model. Studies such as [40] show that performance improvements saturate after about five heterogeneous agents, beyond which cost begins to dominate benefit.

6.7. Best Practices for Evaluation

Based on current literature [8,11,13], one may formulate several hints for best practices as follows:

- Standardize prompts and schemas. Use identical instruction templates and JSON structures across agents to ensure comparability.

- Report both spatial and semantic metrics. mAP alone may obscure linguistic or reasoning improvements.

- Visualize qualitative results. Show consensus heatmaps and reasoning traces for interpretability.

- Measure diversity explicitly. Diversity metrics explain why certain ensembles succeed or fail.

- Include efficiency analysis. Present throughput and scaling trends alongside accuracy gains.

Evaluation of consensus-based detection requires a multidimensional perspective; localization accuracy, semantic understanding, calibration, diversity, and efficiency all play crucial roles. By adopting unified metrics and standardized datasets, the community can move toward fair comparison of consensus strategies and clearer insight into how reasoning diversity translates into perceptual reliability.

7. Challenges and Future Research Directions

While large multi-AI models’ consensus has proven effective in improving robustness and semantic coverage, it also exposes several unresolved challenges. These limitations span computational, methodological, and ethical dimensions. Understanding them is crucial for transforming consensus-based detection from an experimental strategy into a practical, scalable paradigm. This section summarizes the main bottlenecks and emerging research directions that may shape the next generation of multimodal consensus systems.

7.1. Current Challenges

Current large multi-AI models’ consensus pipelines face several open challenges. First, vocabulary alignment and label consistency remain difficult, as different LLMs or VLMs may use incompatible tokenizers, naming conventions, or semantically equivalent but divergent labels (e.g., “bike” vs. “bicycle”), causing fusion mechanisms to interpret genuine agreement as conflict. Second, confidence calibration and uncertainty estimation are still unresolved: each model’s confidence distribution reflects its own training dynamics, meaning that overconfident but inaccurate agents may overpower more reliable ones, and existing techniques such as temperature scaling or isotonic regression [84] only partially mitigate the issue. Third, the computational cost and scalability of running multiple foundation models is substantial, with latency scaling roughly linearly in the number of agents and diminishing returns observed beyond 3–5 heterogeneous models [40], motivating research into lightweight consensus, pruning, and adaptive routing. Fourth, evaluation standardization is still lacking: unlike classical detection, there is no widely accepted benchmark protocol or dataset configuration for fair comparison, which hinders reproducibility and consensus on best practices. Furthermore, bias propagation and fairness remain critical concerns, as ensembling similar models can amplify shared prejudices rather than cancel them, while accountability becomes diffused across agents. Finally, interpretability and traceability degrade with increasing pipeline complexity, making it difficult to reconstruct how a final decision was produced unless explicit reasoning graphs, provenance chains, or audit trails are exposed.

7.2. Emerging Research Trends

The trajectory of research indicates a shift from static ensemble fusion toward dynamic, collaborative intelligence. Consensus frameworks may evolve into foundational infrastructures that jointly maintain situational awareness through multiple reasoning and perception models. By combining interpretability, calibration, and cooperation, they could provide the backbone for trustworthy multimodal AI-capable of not only seeing but also reasoning and verifying what it sees. Large multi-AI model consensus approaches are currently tested in various domains. One of them is medical diagnostics. In this area, successful attempts have been made to combine multiple large AI models to support diagnostics, i.e., in dermatology [85,86].

There are several new trends emerging in this field. Most current systems perform consensus only at inference time. A natural next step is to incorporate consensus into training objectives. Consensus-aware training optimizes models for agreement or uncertainty reduction, enabling them to cooperate more effectively post hoc. Potential methods include multi-agent co-training with shared agreement losses, reinforcement learning with group-level rewards, and distillation of consensus outputs into smaller student models. Early explorations, such as SkillAggregation [36], already move in this direction.

Structured and verifiable reasoning. To make LLM/VLM-based detection auditable, reasoning should be expressed in structured, machine-verifiable formats rather than free text. Possible representations include symbolic scene graphs, pseudo-code, or executable reasoning traces that map directly to detection actions. Such an explicit structure would enable formal verification, reduce hallucination, and make consensus derivations traceable.

Hierarchical and adaptive consensus. Future systems will likely employ multi-layered architectures in which agents specialize and communicate. A lightweight model could handle generic detection, while larger models refine uncertain cases or reason about complex relations. Hierarchical consensus has already shown promise in hybrid designs; integrating adaptive agent selection and trust-weighted fusion could further balance cost and accuracy.

Multimodal uncertainty modeling. Robust perception requires quantifying both epistemic (model-based) and aleatoric (data-based) uncertainty. Combining probabilistic box fusion with reasoning uncertainty from LLMs/VLMs could yield full-scene uncertainty maps. These estimates would support risk-aware decision-making and improve safety-critical applications such as autonomous driving.

Collaborative perception ecosystems. The long-term vision for multi-large AI models’ consensus extends beyond individual detectors toward collaborative perception ecosystems. In such systems, multiple agents—text-based, vision-based, or multimodal—share information dynamically across tasks, scenes, and time. Each agent contributes complementary reasoning or sensory capabilities, and consensus serves as the coordination mechanism ensuring global coherence. Developing communication protocols, trust governance, and distributed training for such ecosystems is an open frontier.

8. Conclusions

The convergence of large-scale language and vision–language modeling with classical ensemble principles has opened a new frontier in visual perception research. This survey has examined the emerging paradigm of multi-large AI models’ consensus for object detection—an approach that unites the reasoning diversity of multiple LLMs/VLMs/MLLMs with the spatial precision of visual detectors to achieve more reliable, interpretable, and semantically rich perception.

We began by tracing the evolution of object detection from region-based CNNs through transformer architectures and open-vocabulary systems, highlighting how language supervision has progressively expanded the perceptual scope of detectors. Next, we reviewed the integration of large AI models as reasoning engines in hybrid frameworks such as DetGPT, ContextDET, and LLMDet, where language models guide or supervise the detection process. building upon these foundations, we introduced a taxonomy of Multi-LLM Consensus strategies, ranging from prompt-level linguistic agreement to reasoning-to-detection fusion and spatial box-level ensembling. We analyzed representative algorithms, including self-consistency, mixture-of-agents, LLM-Blender, and Weighted Boxes Fusion.

We further discussed data fusion methodologies that operationalize consensus, covering techniques such as WBF, ALFA, ProbEn, and trust-weighted fusion. Evaluation practices were reviewed comprehensively, encompassing not only spatial accuracy (mAP, AR) but also semantic consistency, calibration, inter-model diversity, and hallucination reduction. Empirical evidence across multiple studies indicates that consensus ensembles consistently improve recall, calibration, and robustness compared with single-model baselines—particularly for rare, ambiguous, or open-vocabulary categories.

Nevertheless, challenges remain. Vocabulary alignment, score calibration, and computational scalability continue to limit practical deployment. The absence of standardized benchmarks impedes fair comparison, while bias propagation and lack of interpretability raise ethical and transparency concerns. Addressing these issues will require advances in consensus-aware training, structured reasoning representations, probabilistic fusion, and collaborative multimodal ecosystems where diverse agents cooperate dynamically.

Looking forward, multi-large AI models’ consensus represents a conceptual shift toward collective intelligence in artificial perception. By integrating reasoning, grounding, and agreement among autonomous agents, consensus frameworks can transform object detection from a static pattern-recognition task into an adaptive process of shared understanding. As foundation models become increasingly multimodal and interconnected, consensus mechanisms are likely to play a central role in ensuring reliability, transparency, and trust in next-generation AI perception systems. Together, these insights outline a path toward more reliable, interpretable, and trustworthy multimodal AI systems that integrate reasoning and perception through consensus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.; methodology, M.I.; investigation, M.I. and M.G.; resources, M.I. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.I.; visualization, M.I.; supervision, M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT 5 for the purposes of preliminary paper search and summaries, partial descriptions, and language corrections. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ALFA | Agglomerative Late Fusion Algorithm |

| AP | Average Precision |

| AR | Average Recall |

| CLIP | Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training |

| COCO | Common Objects in Context |

| CVinW | Computer Vision in the Wild |

| DETR | DEtection TRansformer |

| ECE | Expected Calibration Error |

| ELEVATER | Evaluating Language-Augmented Visual Models (benchmark/toolkit) |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| GLIP | Grounded Language-Image Pre-training |

| GPT-4V | GPT-4 with Vision |

| ICinW | Image Classification in the Wild |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| LaMI-DETR | Language Model Instruction DETR |

| LLaVA | Large Language and Vision Assistant |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LLM-Blender | Ensembling Large Language Models with Pairwise Ranking and Generative Fusion |

| LLMDet | Learning Strong Open-Vocabulary Object Detectors under LLM Supervision |

| LVIS | Large Vocabulary Instance Segmentation |

| MAD | Multi-Agent Debate |

| MMBench | Multimodal Benchmark |

| MME | Multimodal Evaluation |

| MLLM | Multimodal Large Language Model |

| MoA | Mixture of Agents |

| NMS | Non-Maximum Suppression |

| ODinW | Object Detection in the Wild |

| OV | Open-Vocabulary |

| OVOD | Open-Vocabulary Object Detection |

| OWL-ViT | Open-Vocabulary detection with Vision Transformer |

| POPE | Hallucination evaluation benchmark for VLMs |

| ProbEn | Probabilistic Ensembling |

| RefCOCO | Referring Expressions COCO |

| RefCOCO+ | Referring Expressions COCO+ |

| RefCOCOg | Referring Expressions COCOg |

| VLM | Vision–Language Model |

| VOC | PASCAL Visual Object Classes |

| VQA | Visual Question Answering |

| WBF | Weighted Boxes Fusion |

| YOLO-World | You Only Look Once (YOLO)—World (open-vocabulary variant) |

| Qwen-VL | Qwen Vision–Language |

| InternVL | Intern Vision–Language |

References

- OpenAI. GPT-4V(ision) System Card. 2023. Available online: https://openai.com/index/gpt-4v-system-card/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved Baselines with Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2310.03744. [Google Scholar]

- LLaVA-NeXT: Improved Reasoning, OCR, and World Knowledge. 2024. Available online: https://llava-vl.github.io/blog/2024-01-30-llava-next/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Su, W.; Chen, G.; Xing, S.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Lu, L.; et al. InternVL: Scaling up Vision Foundation Models and Aligning for Generic Visual-Linguistic Tasks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.14238. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, S.; Fu, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, K.; Sun, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, E. A Survey on Multimodal Large Language Models. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Xue, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K.; Hou, L.; Li, R.; Peng, W. A Survey on Hallucination in Large Vision-Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.00253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Chen, L. A Survey on Open-Vocabulary Detection and Segmentation: Past, Present, and Future. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 8954–8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, R.; Wang, W.; Gabruseva, T. Weighted Boxes Fusion: Ensembling Boxes from Different Object Detection Models. Image Vis. Comput. 2021, 107, 104117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razinkov, E.; Saveleva, I.; Matas, J. ALFA: Agglomerative Late Fusion Algorithm for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Beijing, China, 20–24 August 2018; pp. 2594–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; Shi, J.; Ye, Z.; Mertz, C.; Ramanan, D.; Kong, S. Multimodal Object Detection via Probabilistic Ensembling. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Athiwaratkun, B.; Zhang, C.; Zou, J. Mixture-of-Agents Enhances Large Language Model Capabilities. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.04692. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Ren, X.; Lin, B.Y. LLM-Blender: Ensembling Large Language Models with Pairwise Ranking and Generative Fusion. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, R.; Gao, J.; Diao, S.; Pan, R.; Dong, H.; Zhang, J.; Yao, L.; Han, J.; Xu, H.; Kong, L.; et al. DetGPT: Detect What You Need via Reasoning. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Li, W.; Han, J.; Zhou, K.; Loy, C.C. Contextual Object Detection with Multimodal Large Language Models. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2025, 133, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, X.; Fieguth, P.W.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Pietikäinen, M. Deep Learning for Generic Object Detection: A Survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 261–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object Detection in 20 Years: A Survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in Vision: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 200:1–200:41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, X.; Xu, S.; Yuan, H.; Ding, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Y.; Jiang, X.; et al. Towards Open Vocabulary Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 5092–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.; Huang, Y.; Jia, T.; Song, X.; Sun, S.; Wei, H.; Han, X.F.; Huang, S.; Strisciuglio, N.; Li, S. Visual Grounding in 2D and 3D: A Unified Perspective and Survey. Inf. Fusion 2026, 126, 103625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, D.; Han, M.; Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Xu, S.; Xu, B. VLP: A Survey on Vision-Language Pre-training. Mach. Intell. Res. 2023, 20, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Jin, S.; Lu, S. Vision-Language Models for Vision Tasks: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 5625–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gan, W.; Chen, Z.; Wan, S.; Yu, P.S. Multimodal Large Language Models: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Sorrento, Italy, 15–18 December 2023; pp. 2247–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffagni, D.; Cocchi, F.; Barsellotti, L.; Moratelli, N.; Sarto, S.; Baraldi, L.; Cornia, M.; Cucchiara, R. The Revolution of Multimodal Large Language Models: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 13590–13618. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.; Wang, P.; Xiao, T.; He, T.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shou, M.Z. Hallucination of Multimodal Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2404.18930. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wang, J.; Zhao, W.X.; Wen, J.R. Evaluating Object Hallucination in Large Vision-Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, P.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Dukler, Y.; Swaminathan, A.; Taylor, C.J.; Soatto, S. THRONE: An Object-Based Hallucination Benchmark for the Free-Form Generations of Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 27218–27228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Liu, F.; Wu, X.; Xian, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Huang, F.; Yacoob, Y.; et al. HallusionBench: An Advanced Diagnostic Suite for Entangled Language Hallucination and Visual Illusion in Large Vision-Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2310.14566. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, N.; Schott, M. H-POPE: Hierarchical Polling-based Probing Evaluation of Hallucinations in Large Vision-Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.04077. [Google Scholar]

- Seth, A.; Manocha, D.; Agarwal, C. Towards a Systematic Evaluation of Hallucinations in Large-Vision Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2412.20622. [Google Scholar]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G. Ensemble Large Language Models: A Survey. Information 2025, 16, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, P.; Li, Z.; Sun, K.; Luo, Y.; Mao, Q.; Li, M.; Xiao, L.; Yang, D.; et al. Harnessing Multiple Large Language Models: A Survey on LLM Ensemble. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.18036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiga, M.; Jie, W.; Wu, F.; Voskanyan, V.; Dinmohammadi, F.; Brookes, P.; Gong, J.; Wang, Z. Ensemble Learning for Large Language Models in Text and Code Generation: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13505. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Le, Q.; Chi, E.; Narang, S.; Chowdhery, A.; Zhou, D. Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2203.11171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, S.; Torralba, A.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Mordatch, I. Improving Factuality and Reasoning in Language Models through Multiagent Debate. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.14325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, S.F.; Ilhan, F.; Huang, T.; Hu, S.; Liu, L. LLM-TOPLA: Efficient LLM Ensemble by Maximising Diversity. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 11951–11966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Kagrecha, A.; Manakul, P.; Woodland, P.; Gales, M. SkillAggregation: Reference-free LLM-Dependent Aggregation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.10215. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, M.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Klang, E. Refining LLMs outputs with iterative consensus ensemble (ICE). Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 196, 110731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Chiang, W.L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Xing, E.P.; et al. Judging LLM-as-a-Judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.05685. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Zuo, C. Free-MAD: Consensus-Free Multi-Agent Debate. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.11035. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Davis, J.Q.; Hanin, B.; Bailis, P.; Stoica, I.; Zaharia, M.; Zou, J. Are More LLM Calls All You Need? Towards Scaling Laws of Compound Inference Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.02419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair-Kanneganti, A.; Chan, T.J.; Goldfinger, S.; Mackay, E.; Anthony, B.; Pouch, A. Increasing LLM response trustworthiness using voting ensembles. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.04048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.K.; Zhu, X.; Li, S. Debate or Vote: Which Yields Better Decisions in Multi-Agent Large Language Models? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.17536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Zhang, H.; Lei, Z.; Han, P.; Patwary, M.; Shoeybi, M.; Catanzaro, B.; You, J. FusionFactory: Fusing LLM Capabilities with Multi-LLM Log Data. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.10540. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, D.; Xie, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z. Ensemble Learning in Vision-Language Models: Challenges and Opportunities. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2024, 181, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Chen, X.; Hossain, R. Object Detection Ensemble Methods: A Comparative Study. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 88256–88270. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.; Li, K.; Wu, L.; Chen, K. A Survey of Ensemble Learning for Object Detection. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2023, 178, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodla, N.; Singh, B.; Chellappa, R.; Davis, L.S. Soft-NMS—Improving Object Detection with One Line of Code. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 5561–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubeck, A.; Van Gool, L. Efficient Non-Maximum Suppression. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Hong Kong, China, 20–24 August 2006; Volume 3, pp. 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]