Abstract

The development of human-robot interfaces that support daily social interaction requires biomimetic innovation inspired by the sensory receptors of the five human senses (tactile, olfactory, gustatory, auditory, and visual) and employing soft materials to enable natural multimodal sensing. The receptors have a structure formulated by variegated shapes; therefore, the morphological mimicry of the structure is critical. We proposed a spring-like structure which morphologically mimics the roll-type structure of the Meissner corpuscle, whose haptic performance in various dynamic motions has been demonstrated in another study. This study demonstrated the gustatory performance by using the roll-type Meissner corpuscle. The gustatory iontronic mechanism was analyzed using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy with an inductance-capacitance-resistance meter to determine the equivalent electric circuit and current-voltage characteristics with a potentiostat, in relation to the hydrogen concentration (pH) and the oxidation-reduction potential. In addition, thermo-sensitivity and tactile responses to shearing and contact were evaluated, since gustation on the tongue operates under thermal and concave-convex body conditions. Based on the established properties, the roll-type Meissner corpuscle sensor enables the iontronic behavior to provide versatile multimodal sensitivity among the five senses. The different condition of the application of the electric field in the production of two-types of A and B Meissner corpuscle sensors induces distinctive features, which include tactility for the dynamic motions (for type A) or gustation (for type B).

1. Introduction

Bio-inspired sensors based on the biological mimicry of sensory organs in the five senses (tactile, olfactory, gustatory, auditory, and visual) involving cutaneous receptors of the human skin have been a significant theme in recent research because they offer remarkable potential for advancing modern lifestyles through healthcare, human-robot interaction, and related technologies [1,2,3,4,5]. To achieve such advancement, an integrated strategy combining technological and bio-inspired material innovation is critical [6]. In particular, sensitivity to diverse stimuli such as pressure, temperature, light, and gas [7,8] has been actively investigated in the field of flexible electronics, which enables wearable functionality [9], including high-performance haptics realized through e-skin technology [10,11].

Because the critical prerequisites for developing bio-inspired materials are softness and elasticity similar to those of the human body, biomimetic flexible electronics contribute to the development of multifunctional materials. The reason for this is that soft materials can be engineered to exhibit both an iontronic response and electronic behavior [12]. For example, ionic liquids [13] and conductive hydrogels [14] exhibit high sensitivity, particularly toward gustatory and olfactory stimuli, which makes them suitable models for sensory biomimetic systems. However, thus far, these investigations have been dealt with by simulating the paradigm of the iontronic systems and the electrochemical reaction, but not the morphological structure. For example, human cutaneous receptors have a structure formulated by variegated shapes such as a capsule, layered, or ramose configuration. Therefore, investigating the morphological mimicry of the structure is critical so that the novel sensing can developed. We have also proposed a spring-like structure that morphologically mimics the roll-type structure of the Meissner corpuscle in another study. This sensor, which was fabricated from soft rubber as a biomimetic cutaneous mechanoreceptor, has demonstrated strong haptic performance under various dynamic motions such as pressure, shearing, and twisting, and functioned as a self-powered system, as we showed previously [15]. Because the material simultaneously exhibits iontronic behavior, the fabricated sensor is expected to provide versatility for other sensitivities, including gustation, where the tongue integrates gustatory, tactile, and thermal sensations. The multifaceted sensitivity demonstrates the condition under which the palate is perceived during shearing on a thermal surface. In the present study, we investigated the feasibility of a versatile biomimetic roll-type Meissner corpuscle receptor for gustatory responses to shearing, thermal, and ionic stimuli using our proposed rubber-based electrolytic polymerization technique to advance gustatory biomimetics.

Incidentally, the outline of the present study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outline of the present study.

2. Materials and Fabrication

The instruments used for measuring the five tastes—bitterness, sweetness, saltiness, and umami—have traditionally relied on chemical analytic systems equipped with lipid/polymer membranes, commonly referred to as taste sensors [16,17,18], which do not morphologically mimic biological receptors. Thus, the taste sensor is typically a component installed in a bulky instrument. In contrast, for the convenience of wearable applications, various morphologically performing biomimetic sensors for gustation have been developed, including the so-called electronic tongue [19]; taste-receptor systems with micro-electrode arrays [20] or polypyrrole (PPy) arrays [21]; ionic-conductivity taste sensors [22]; and electric cell–substrate impedance sensors (ECISs) [23]. Our proposed morphological gustatory sensor is distinctive enough to demonstrate a different performance from those existing sensors. It offers valuable merits; namely, it can be produced easily without expensive instruments such as MEMS and can be fabricated at reasonable cost using affordable materials.

According to the diagnostic summary of the cutaneous mechanoreceptors inspired by the biomimetic sensor, as we described previously [15], the Meissner corpuscle is the optimum receptor, characterized by high mechanical sensitivity and fast adaptation (FA) behavior. On the other hand, the biomimetic sensor morphologically fabricated from this mechanoreceptor should possess versatility, being responsive to stimuli in both ionic and mechanical interfaces involving tactile and thermal sensations, gustation, olfaction, and other sensory modes. In particular, the iontronic performance plays a key role in gustation, and the gustatory response is likewise influenced by mechanical interactions, since the tongue acts through tactile and shearing contact with palpable objects. To realize this prerequisite, we utilized soft rubber as the base material and adopted a novel, cutting-edge rubber-solidification method by electrolytic polymerization, as described in our previous research. The overall procedure for producing the biomimetic Meissner corpuscle made of soft rubber is summarized as follows.

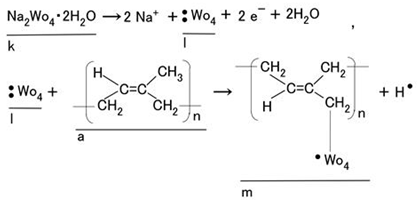

The electrolytic polymerization involves the electrolysis of water. Therefore, to polymerize on the rubber, a water-soluble rubber such as natural rubber (NR) or chloroprene rubber (CR) must be combined with water-insoluble rubbers such as silicone–oil rubber (Q) or urethane rubber (U) by emulsion polymerization using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) as the emulsifier. Simultaneously, magnetic clusters are formed by aggregating metal particles of different sizes—10 nm spherical magnetite (Fe3O4) and 1 μm ordered metals such as Ni or Fe—under a magnetic field applied parallel to the electric field during electrolytic polymerization. Owing to these magnetic clusters, electrical and thermal conductivity along the clusters is enhanced, thereby increasing the sensitivity of the rubber. Therefore, our proposed hybrid fluid (HF), one of the magnetically responsive intelligent fluids containing Fe3O4 and 1 μm ordered Fe particles, was used during fabrication. Simultaneously, the HF also contains a surfactant that plays a crosslinking role among rubber molecules during electrolytic polymerization, as shown in the following equations. In addition to the electrolytic polymerization, we used the metallic hydrate of a metal complex such as Na2WO4∙2H2O to render the rubber ion-permeable, thereby imparting condenser-like (capacitive) properties (as shown in Figure 1), and we adhered the electric wires to the rubber using Na2WO4∙2H2O, which prevented the electric wires from detaching. As the electrolysis of water proceeds, H2 and O2 gases are generated at the cathode and the anode, respectively, during the electrolytic polymerization. The evolution of these gases produces numerous pores within the rubber structure. Through electrolytic polymerization, the mixed particles and ions of the rubber become anionic or cationic, enabling the solidified rubber to possess an intrinsic potential, thereby eliminating the need for an external power supply.

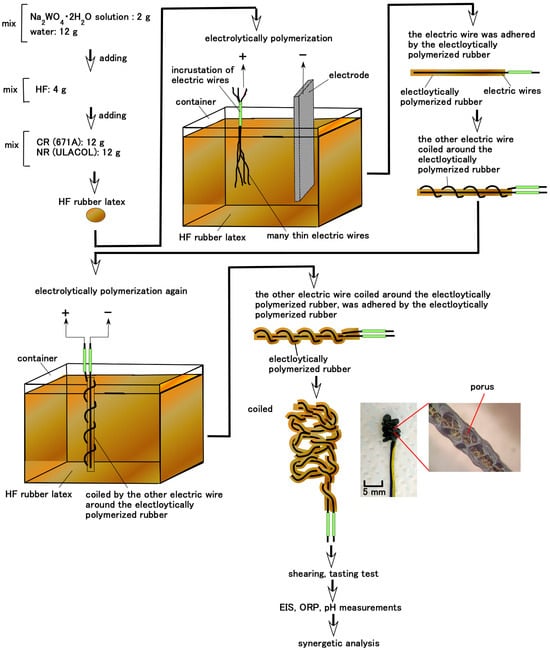

Figure 1.

Production and experimental process of biomimetic Meissner corpuscles for gustation.

The 0.1 mm diameter electric wire was dipped in the HF rubber latex comprising Na2WO4·2H2O (Fujifilm Wako Chemical Co., Osaka, Japan), NR (ULACOL; Rejitex Co., Ltd., Atsugi, Japan), CR (671A; Showa Denko Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and HF, as shown in Figure 1. HF consisted of 3 g Fe3O4 (Fujifilm Wako Chemical), 3 g Fe (M300, about 50-μm particles; Kyowa Pure Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), 3 g water, 3 g kerosene, 3 g silicone oil (KF96 with 1-cSt viscosity with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS); Shin-Etsu Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), 21 g PVA, and 4 g sodium hexadecyl sulfate aqueous solution as a surfactant (C16H33NaO4S, Fujifilm Wako Chemical). One electric wire was fixed to the rubber by electrolytic polymerization at 20 V, 2.7 A, and 10 s, and then another electric wire was helically coiled around the electrolytically polymerized rubber, as shown in the figure. In the present study, we did not compound carbonyl Ni powder (No. 123; Yamaishi Co., Ltd., Noda, Japan) with micron-sized surface bumps, nor TiO2 (anatase type; Fuji-film Wako Chemical), into the rubber—these were materials we used in our previous research to enhance electron transfer.

The specimen was subsequently dipped in the HF rubber latex again, as illustrated in the figure. We examined two types of conditions for the application of the electric field at the electrode, as follows.

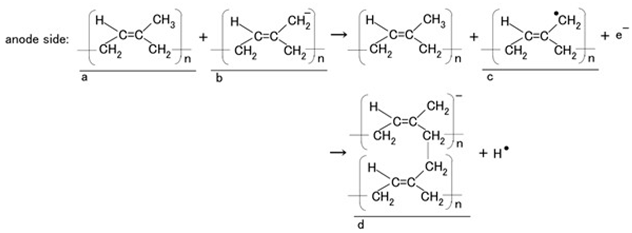

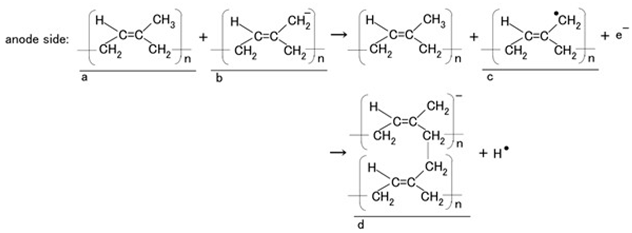

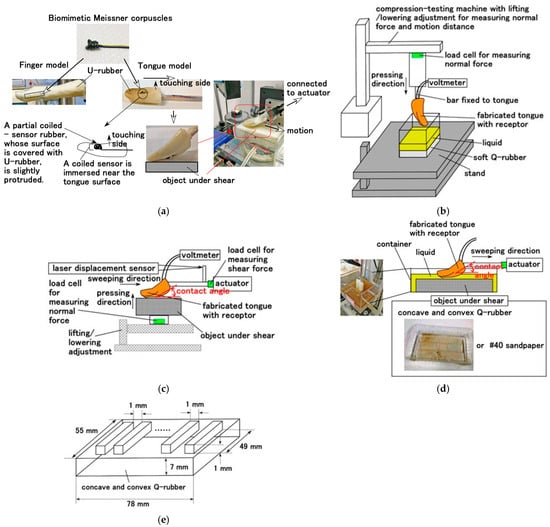

Type A: The electric wire coiled around the electrolytically polymerized rubber served as the anode, and the electrode immersed in the HF rubber latex served as the cathode. The isoprene molecules of CR and NR (a in Equation (1)) were predominantly stable in the anionic state under the initial latex conditions (b in Equation (1)). The anionic isoprene (c in Equation (1)) acted as the initiator of cationic polymerization. The isoprene molecules crosslinked to form anionic polymers (d in Equation (1)) that migrated toward the anode, where cationic polymerization occurred. Consequently, both rubbers polymerized electrolytically on the electric wires underwent cationic reactions.

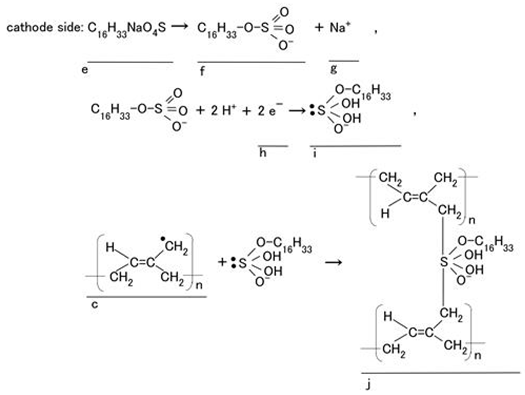

Type B: The electric wire coiled around the electrolytically polymerized rubber served as the anode, and another electric wire that had been polymerized beforehand served as the cathode. The surfactant C16H33NaO4S (e in Equation (2)) readily became anionic (f in Equation (2)) when dissolved in water. The anionic sodium (f in Equation (2)) acted as the initiator of anionic polymerization. On the cathode side, it was converted to a radical species (i in Equation (2)) by electron capture (h in Equation (2)). Next, it polymerized with anionic isoprene (c), forming the product (j) as shown in Equation (2). The cationic sodium (g in Equation (2)) migrated toward the cathode, promoting anionic polymerization at that site. Alternatively, the cationic sodium re-combined with the cationic crosslinked polymer (j in Equation (2)), terminating the reaction. As a result, each rubber that polymerized electrolytically on the electric wires exhibited both cationic and anionic reactions.

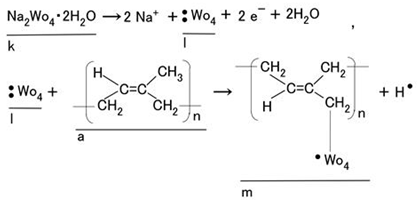

On the other hand, as our previous study showed, Na2WO4∙2H2O (k in Equation (3)) reacted with radical WO4 (l in Equation (3)), and the radical WO4 further reacted with isoprene molecules (a in Equation (3)) to form a crosslinked polymer (m in Equation (3)). This polymer was sufficiently anionic to combine with cationic metal species through ionic bonding. As a result, Na2WO4∙2H2O acted as a coupling agent between the electric wires and the rubber.

Based on the hypothesis that the difference in reaction mechanisms between Types A and B leads to different sensitivity characteristics, we compared their responses using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) with an inductance-capacitance-resistance (LCR) meter.

In the final stage of the fabrication phase, the electrolytically polymerized rubber was coiled as shown in Figure 1.

Incidentally, degradation poses a significant problem when it comes to maintaining sensitivity during long-term practical applications. In order to solve the degradation issue, HF has been developed so that it includes the ingredient compounded by both the diene and non-diene rubber. The key point of the durability of the rubber is compounding both the diene (ex. NR, CR) and non-diene rubber (silicon oil rubber containing PDMS, ex. KF96), which has been already elucidated in the MCF rubber in a study we performed previously. MCF is the precursor to HF because HF has been developed with an easy production technique. Therefore, when HF is mixed with any rubber, its durability can be maintained.

3. Experimental Procedure

3.1. Experimental Setup

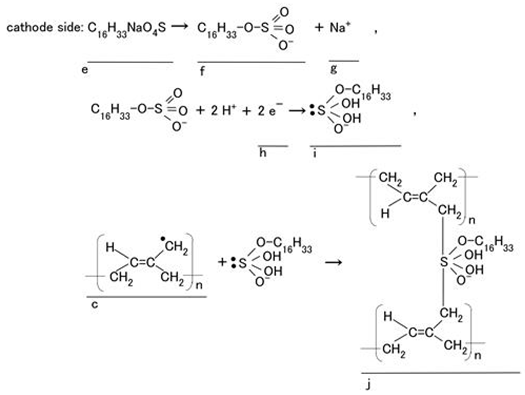

The artificial biomimetic mechanoreceptors of roll-type Meissner corpuscles were embedded in a U-rubber (Human Skin Gel; Exseal Co., Ltd., Gifu, Japan) that mimicked a human tongue in which the roll-Type B Meissner corpuscles were embedded, as shown in Figure 2a. For comparison with the tongue, we also fabricated a finger model in which the roll-Type A Meissner corpuscles were embedded. Because Type B featured gustation, it was installed in a tongue. In contrast, because Type A featured tactility, it was installed in a finger. They were both mounted on a compression-testing machine (SL-6002; IMADA-SS Co., Ltd., Toyohashi, Japan), as shown in Figure 2b, and connected to an actuator to conduct shearing performance tests on various objects either in or without a bath filled with liquid, as shown in Figure 2c,d. For the purpose of demonstrating the differences in the featured gustatory responses of Type A and Type B sensors, the bare artificial biomimetic mechanoreceptors were also tested. The artificial tongue or bare receptor was dipped in a liquid placed on the Q-rubber substrate (KE1300-T (PDMS, Shin-Etsu Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The liquid was diluted threefold with thinner, yielding a compression Young’s modulus of 0.0199 GPa, or was pressed upward against the Q-rubber using the compression-testing machine, as shown in Figure 2b. As for the shearing motion, the fabricated tongue was sheared by the actuator against test objects with controlled surface roughness, including sandpaper (Figure 2c) and a concave-convex Q-rubber specimen (undiluted; compression modulus 0.139 GPa (Figure 2d,e), at controlled sweep speeds and pressing forces while maintaining a constant angle between the tongue and the shear surface. Different-tasting liquids were used to test sweetness (sugar solution in water), saltiness (salt solution in water), sourness (rice vinegar solution in water), bitterness (coffee solution in water), and umami (tuna powder solution in water); all of the samples were prepared at a mass concentration of 18.7 wt%.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of the experimental apparatus: (a) biomimetic Meissner corpuscles and the fabricated tongue and finger; (b) the pressing state under the compression-testing machine; (c) the shearing state driven by the actuator; (d) the tongue dipped in liquid or coming into contact with an object; (e) a concave-convex object.

3.2. Data Acqusition

The voltage from the receptor was recorded with a voltmeter (PC710; Sanwa Electric Instrument Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The relationship between electric current I and voltage V was determined using a potentiostat (HA-151B; Hokuto Denko Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at a scan rate of 50 mHz over a potential range of −0.1 to 0.1 V. It had 0.1% accuracy and 0.05 msec response time. The liquid’s redox potential (ORP) was measured using an ORP meter (YK-23RP-ADV, SatoTech Co., Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan), and the pH was measured using a pH meter (PH-208, SatoTech Co., Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan). The former had 0.8% accuracy and the latter had 0.14% accuracy.

To clarify the sensitivity mechanisms of the fabricated sensor, the AC electrical properties were characterized using an LCR meter (IM3536; Hioki Co., Ltd., Ueda, Japan) to evaluate electronic and ionic behavior within the equivalent electric circuit (EEC) of the sensor. It had 0.05% accuracy, 0.1 msec response time, 1 V excitation amplitude, a 4 Hz–8 MHz frequency response range, and a maximum of 64 repeats. Few studies have analyzed the impedance spectra of biomimetic gustatory sensors [24], and their electrical performance remains unclear.

3.3. Data Analysis

Throughout the measurements, the specimen sizes as shown in Figure 2a were 7 mm diameter and 10 mm length for the bare roll-type Meissner corpuscles; 32 mm width, 47 mm length, and 10 mm thickness for the tongue; and 20 mm diameter and 50 mm length for the finger. Repetitions were performed 10–20 times. The accuracy of the measurement instruments is presented in the next section, and the measurement error is minor. The cause is described in the Results and Discussion Section.

4. Results and Discussion

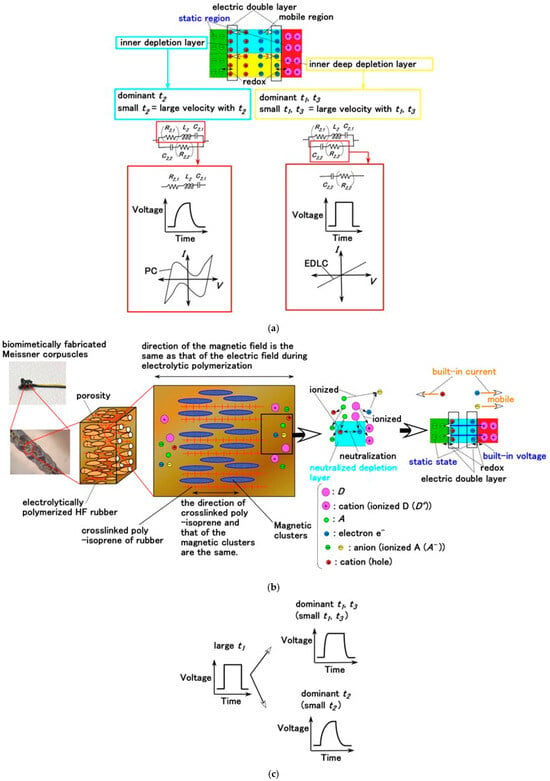

4.1. Optimal Electrolytical Polymerization

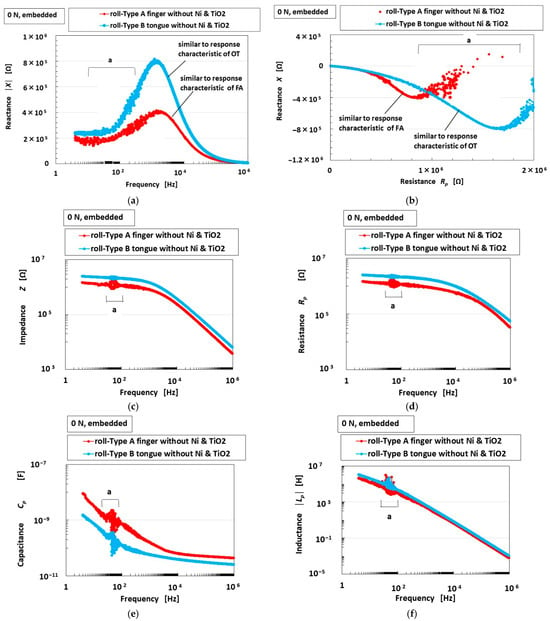

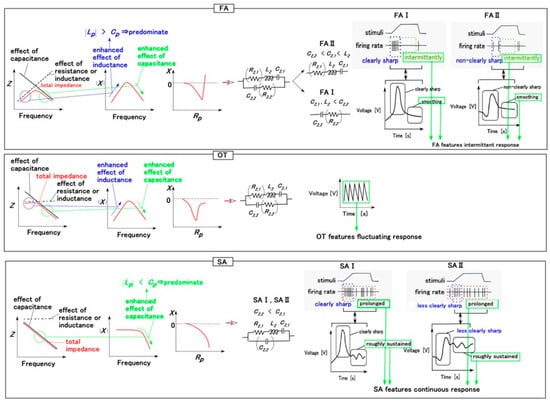

Figure 3 shows the EIS results for the tongues with Type A and B sensors. To clarify the optimal morphology of the roll-type Meissner corpuscles, we evaluated the changes in absolute reactance and the relationship between reactance and resistance, in accordance with the classification elucidated in our previous study [25], in which the firing rate was categorized as slow adaptation (SA: SA I and SA II), fast adaptation (FA: FA I and FA II), or other type (OT) in response to the applied stimuli (Figure 4). Figure 4 summarizes the classification corresponding to the EEC behavior and changes in sensor voltage compared to the results described in [25]. The EEC formulated the electrical double layer (EDL) in the HF rubber as shown in the Figure. It was possible to evaluate this using the Nyquist diagram for EIS. However, the diagram cannot be applied to the HF rubber due to the following factors. As presented in our explanation of the behavior of the ions and particles in the HF rubber, the EDL is not uniformly established with an almost constant distance between the ions in the HF rubber. The outer-sphere electron transfer reaction (OSETR), which is well known as the electron transfer theory in the macromolecular complexes field of the inorganic metal complex, induces a change in the ionic radius that creates the non-uniform distribution of the EDL in the HF rubber. The Nyquist diagram of the HF rubber cannot provide clear profiles. Therefore, the results connote that the HF rubber should belong to the impurity semiconductor, but not the intrinsic semiconductor. And then, as was the case for the HF rubber, we have proposed the classification of the EIS results corresponding to the EEC, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

EIS results for roll-type Meissner corpuscles comparing Types A and B sensors without any compression: (a) absolute reactance; (b) relationship between reactance and resistance; (c) impedance; (d) resistance; (e) capacitance; (f) absolute inductance; (a,b) the redundant data are reduced for easier comprehension.

Figure 4.

Relationships between the impedance, absolute reactance, reactance-resistance correlation obtained by EIS, the EEC, and the voltage response [25].

As presented in another study [15], the optimum ingredients of the roll-type Meissner corpuscles exclude Ni, since the inclusion of Ni promotes magnetic cluster formation, as well as TiO2, which acts as an electron-transfer medium; under these conditions, Type A exhibits FA behavior. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 3, Type B exhibits OT behavior. In the case of Type B, the inductance Lp and resistance Rp are greater, but the capacitance Cp is weaker than that of Type A.

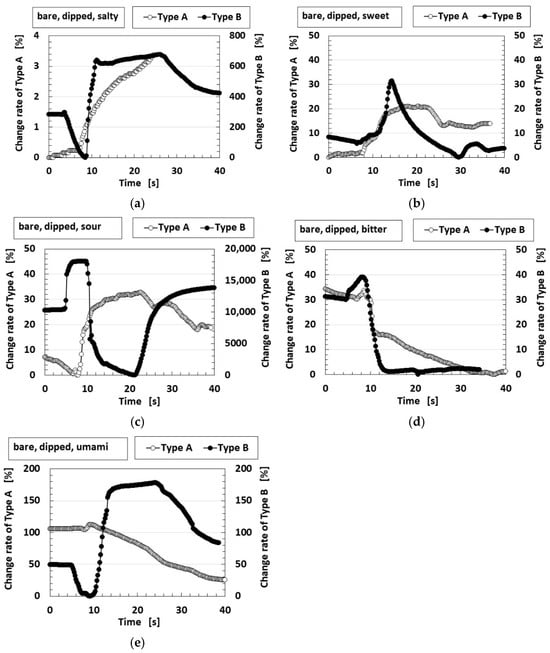

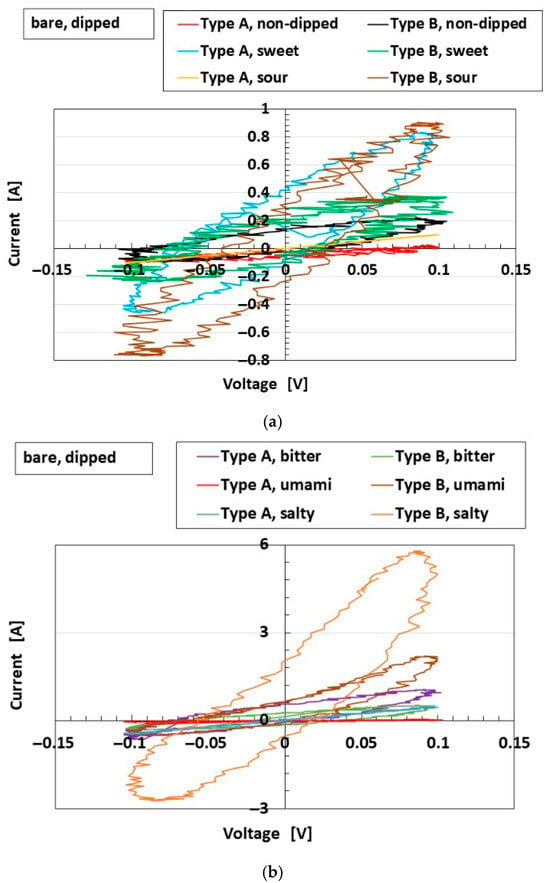

Figure 5 compares the rate of the change in sensor voltage when the bare roll-type Meissner corpuscles, which were not embedded in U-rubber, were dipped in liquid as shown in Figure 2b. All taste stimuli showed that Type B was more sensitive, with a larger enhanced change rate than Type A. Figure 6 shows the C-V profiles obtained with the potentiostat and indicates that Type B exhibits a larger overall loop area than Type A.

Figure 5.

The rate of voltage change in the bare sensor, not embedded in the finger, dipped in each solution. Type A and Type B are compared with regard to the five tastes: (a) saltness; (b) sweetness; (c) sourness; (d) bitterness; and (e) umami.

Figure 6.

C-V profiles of the bare sensor, not embedded in the finger, dipped in liquid. Type A and Type B are compared with regard to the five tastes: (a) non-dipped, sweetness, and sourness; (b) bitterness, umami, and saltiness.

Based on the results provided (Figure 3, Figure 5 and Figure 6), Type B demonstrates higher sensitivity to gustatory stimuli and is therefore considered the more optimal configuration. Consequently, as shown in Figure 7a, the sensor exhibiting OT and SA characteristics, with a larger C-V loop area, is optimal for gustation compared with that exhibiting FA behavior, which shows a linear C-V profile. This phenomenon arises as a result of the behavior of anionic and cationic ions within the HF rubber, as shown in Figure 7b. Figure 7 is summarized based on the elucidated results in [25,26].

Figure 7.

The relationship between the inner structure of the rubber sensor, EIS results, EEC, and the corresponding voltage variations and C-V profiles; (a) comparative results; (b) physical model of the inner structure; (c) voltage curve for t1, t2, and t3 [25,26].

The molecules of HF rubber and water, along with Fe3O4 and Fe particles functioning as dopant D and acceptor A, respectively (Figure 7b), are ionized as D+ (cationic) and A− (anionic). A− tends to be desorbed by holes, whereas D+ remains relatively immobile, thereby generating an intrinsic built-in voltage. The holes, electrons, and A− species that migrate in association with the electronic charge flow are mobile, thereby forming a built-in current. As a result, the HF rubber exhibits piezoresistive behavior. The holes approach negatively aggregated regions formed by A− (desorbed by holes) or, conversely, A− species (absorbed by electrons) migrate toward positively aggregated regions of D+, thereby forming EDL, as illustrated in Figure 7a. A Faradaic reaction occurs at the EDL, and the resulting C-V or I–V profiles exhibit a linear relationship, corresponding to the behavior of an electrical double-layer capacitor (EDLC). When a redox process arises between the static and interfacial D+ and A− species within the EDL, the C-V or I–V profiles become nonlinear, indicating the formation of a pseudocapacitor (PC): the redox regions are between D+ and electrons, and between A− and holes at the circumference of the depletion layer, as shown in Figure 7. The response time t depends on the dynamics of D+, A−, and electrons and can be divided into three components, as expressed in Equation (4): t1, associated with capacitance C and resistance R (approximately equal to 2.2 CR); t2, corresponding to carrier diffusion in deeper regions of the depletion layer; and t3, related to carrier motion within the inner depletion layer [26]. Here, the voltage curve is changed by t1, t2, and t3, as shown in Figure 7c. C arises from the EDLC within the depletion layer, and R is determined by the mobility of D+ and A− across the layer. Thus, the interrelation among the C-V or I–V profiles, EEC, and sensor-voltage variations remain inadequately clarified in current gustation studies (ex. [27]).

Incidentally, the disturbance indicated by region “a” in Figure 3 as well as the perturbation in Figure 6 is mainly attributed to several factors: (1) measurement error; (2) impurities introduced during sensor fabrication; (3) perturbation of HF rubber and water molecules and Fe3O4/Fe particles; and (4) tunneling of mobile electrons through nonconductive components such as rubber and surfactant whose phenomena has been theoretically clarified in our earlier work [26,28].

Regarding (1), the error is dependent on the measurer’s habit, the surroundings, and the error of the instruments. The humidity was controlled at 45–50% and the temperature 23–25 °C was acceptable and did not require any intervention. The instruments’ error was also minimal and was acceptable, as demonstrated by the accuracy which is described in an upcoming section of the paper.

Factors (2) and (3) can be considered to be involved in the complex behavior of the particles and ions in the HF rubber. Dopant D and acceptor A react via electrolytic polymerization, as shown in Equation (5). Subsequently, when the electric wires from the electrolytically polymerized HF rubber are short-circuited, one of the electrons can transfer between the anode and cathode of the sensor via the reaction shown in Equation (6); the anode of the sensor is replaced in the anode side of the electrode during the electrolytic polymerization, and is like that in the cathode as well. The reaction cannot be generated on the other electrons. These phenomena have already been elucidated in our previous research on MCF rubber using the electron transfer theory in the field of macromolecular complexes [29]. The development of this theory as it pertains to HF rubber can be summarized as follows. Previously, MCF was the precursor to HF because HF has been developed with a simple production technique and reasonable ingredients. MCF rubber is characterized by the same quantitative and qualitative properties as HF rubber. Now, as shown in Figure 7b, when it comes to the dispersion of the particles of Fe3O4 and Ni, and molecules of polyisoprene, the interaction between them is varied. When the distance between them is large, the interaction is comparatively weak so that the reaction of Equation (6) cannot occur easily. This is considered to be the OSETR, which means the structural coordination of molecules is not deformed and only the electrons are transferred by the tunneling effect. In this scenario, anionic polyisoprene is the bridging ligand. In contrast, there can be an inter-sphere electron transfer reaction (ISETR) when there is a comparatively strong interaction among them so that the reaction of Equation (6) can occur, which is generated on the basis of the interaction of the reactants and mediation of the bridging ligand of the anionic surfactant and the anionic polyisoprene. OSETR and ISETR are well-known subjects in the field of inorganic metal complexes. Thus, whether OSETR or ISETR occurs depends on the probability of the distance among the particles of Fe3O4 and Ni, and molecules of polyisoprene—OSETR occurs in response to large distances and ISETR for smaller ones. As numerous particles and molecules are dispersed in a solvent, many such OSETRs or ISETRs must be taken into account.

On the other hand, the tunneling effect regarding (4) must also be considered as a dominant factor affecting HF rubber: the complex behavior of the particles and ions in MCF rubber can be formulated by the tunnel theory, as presented in our previous studies [26,28], so that a disturbance is created. MCF rubber features the same properties as HF rubber. A theoretical analysis of the tunnel mechanism is presented in Appendix A.1. Owing to the tunnel effect, the electron can abruptly pass through the nonconductive rubber and surfactant so that the electric current changes in a jumping formulation; this phenomena was confirmed by the experiment, as shown in Appendix A.2. The jumping changes also affect the parameters of EIS at a typical frequency as shown in part “a” in Figure 3. And the typical frequency exists at a comparatively low frequency range. The typical frequency is presumed to be due to the kinds of ingredients and concentrations of the HF rubber, the electric conditions of the electrolytic polymerization, etc., which create the natural frequency of the vibration behavior of the particles and ions of HF rubber. However, this mechanism may be in need of further investigation.

Next, we investigate the repeatability of the experimental results and how this contributes to the accuracy. In order to resolve the technical issues associated with measuring EIS, the LCR meter used had the instrument functions to reduce both the floating admittance and the residual impedance in the measuring cable not only by incorporating all correction values at frequency range but by attaching the test fixture between the device under test (DCT) and the LCR meter. The present DCT corresponds to the HF rubber sensor. These results improve the reliability so that the measurement accuracy will be enhanced. Here, the test fixture to which the current accessory is added has the purpose of measuring just the targeted resistance by reducing the used lead wire’s resistance and the contact resistance. It is currently structured using the four-terminal method, in contrast with the two-terminal method. As for the consequent minimal residual impedance of the used LCR meter, for example, the residual resistance at the short circuit is less than 5 mΩ at 100 Hz, and the floating capacitance between the electrodes is less than 2 pF at 5 Mz.

On the other hand, regarding C-V profile, the used potenstiostat had the instrument functions to enable the discrimination of the counter electrode and the working electrode by using the three-electrode structure. The potentiostat characterized three features. It controlled the potential of the working electrode and the reference electrode and measured the electric current passing through the working electrode without passing the electric current to the reference electrode. These features contrast with the two-electrode structure, which cannot easily discriminate between the counter electrode and the working electrode. Therefore, our used potentiostat can provide accurate results.

Consequently, the disturbance that appeared in the results for EIS and the C-V profile was predominantly due to the perturbation of the molecules, particles, ions, and electrons in the HF rubber.

The above-mentioned results show that the optimal electrolytic polymerization for gustation is Type B rather than Type A, and the previous findings demonstrate that Type A is optimal for haptic sensation [15]. This suggests that the cationic reaction at both electric wires on the anode is suitable for tactile sensing, whereas both cationic and anionic reactions, occurring at the anode and cathode, respectively, are suitable for gustation. The former depends on the changes in sensor voltage induced by the iontronic behavior resulting from the rubber’s deformation. The latter depends on the iontronic behavior induced by both types of ionic reactions when the rubber comes into contact with the ionic liquids present in foods and beverages. Therefore, we adopted Type B in the variegated gustatory experiments described in the following sections.

4.2. Roughness Without Liquid

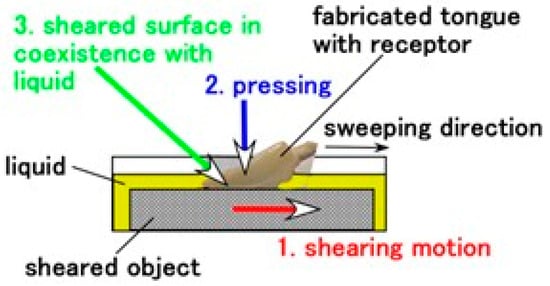

Gustatory sensitivity to various foods and beverages must be classified in response to several conditions: 1. the surface roughness and softness of the sheared object; 2. shearing conditions such as pressing normal force and sweeping velocity; and 3. the coexistence of liquid and solid phases, as delineated in Figure 8. Therefore, we conducted experiments according to these classified conditions.

Figure 8.

Experimental condition categories for gustatory sensitivity.

First, the tongue, as shown in Figure 2a, is sheared on sandpaper as shown in Figure 2c, without any liquid, under the experimental conditions of pressing normal force (Figure 9a), sweeping velocity (Figure 9b), and sandpaper surface roughness (Figure 9c), with a fixed 40° angle between the tongue and the shear surface. The surface roughness was evaluated using the arithmetic average height Ra, root mean square height Rq, and maximum-to-minimum height difference Ry as shown in Equation (7). L is the reference length, measured by a surface roughness-measuring device (SJ-400, Mitutoyo, Co., Ltd., Kawasaki, Japan). The sensor voltage was also evaluated using the same Ra, Rq, and Ry values, denoted as Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E.

Figure 9.

Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E of sensor voltage in the tongue under shearing without liquid: (a) the effect of normal stress; (b) the effect of shear velocity; (c) the effect of surface roughness Ra; (d) the effect of surface roughness Rq; (e) the effect of surface roughness Ry.

At the intermediate normal-stress range, Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E become smaller, as shown in Figure 9a. This may be because Type B exhibits a natural frequency owing to its spring-like structure. On the other hand, the larger the sweeping velocity, the larger Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E gradually become, as shown in Figure 9b. It is supposed that the Type B spring-like structure deforms and tilts in the direction of motion. Moreover, Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E increase exponentially at lower Ra, Rq, and Ry values, then reach saturation at higher roughness levels. This may be because the surface roughness approaches the characteristic dimension of an individual coil segment.

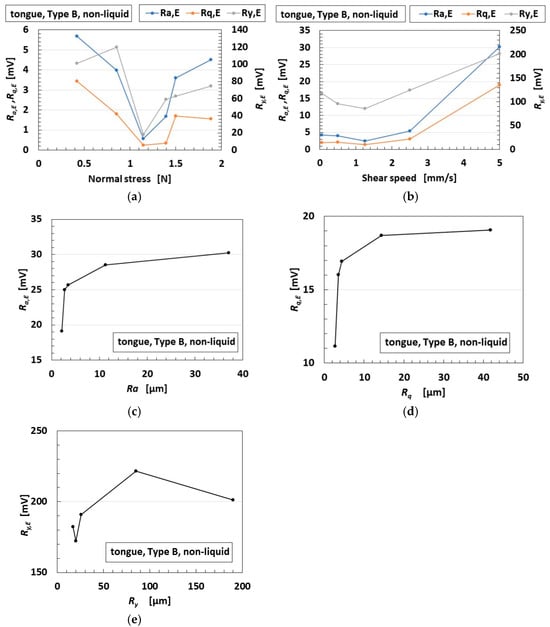

4.3. Synergy of Shearing and Tasting

Secondly, the synergistic sensitivity of the surface roughness and the liquid corresponding to foods representing the five basic tastes is shown in Figure 10, where the tongue shears sandpaper (#40; Ra = 37.07 μm, Rq = 41.8 μm, Ry = 190 μm) in liquids embodying the five tastes (Figure 2d) under a pressing force of 1.884 N, shear velocity of 5 mm/s, with a stable 40° angle between the tongue and the shear surface. Because the sensor voltage initially includes a built-in potential, its change represents sensitivity; therefore, the ratio of the voltage change to the initial voltage is shown in the figure. The change rate differs depending on the taste, as shown in Figure 10a,b. Similar results were obtained for the soft-sheared Q-rubber object shown in Figure 10c,d. These results suggest that the synergistic changes in sensor voltage for different tastes are related to the hardness of the flavored object. We may interpret this behavior using the hydrophilic paradigm of the Hofmeister effect. The Hofmeister effect describes the relationship between tactile and taste sensing in the human tongue [30,31]. The Hofmeister effect indicates that tactile hardness perceived by the tongue correlates with gustatory sensitivity to hydrophilic liquids. We expanded this paradigm using ORP and pH rather than the Hofmeister series because each liquid contained diverse anions and cations, making it difficult to distinguish which kosmotropes or chaotropes affected the hydrophilic response.

Figure 10.

Correlation of the sensor voltage with shearing and tasting with the tongue: (a) change rates of the sensor voltage without liquid and in liquids with saltiness and sweetness in response to shearing on #40 sandpaper; (b) change rates of the sensor voltage without liquid and in liquids with sourness, bitterness, and umami in response to shearing on #40 sandpaper; (c) change rates of the sensor voltage without liquid and in liquids with saltiness and sweetness in response to shearing on concave and convex objects; (d) change rates of the sensor voltage without liquid and in liquids with sourness, bitterness, and umami in response to shearing on concave and convex objects; (e) Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E of the sensor voltage for five tastes in response to shearing on #40 sandpaper; (f) Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E of the sensor voltage versus ORP in response to shearing on #40 sandpaper; (g) Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E of the sensor voltage versus pH in response to shearing on #40 sandpaper.

We present detailed results for Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E in Figure 10e. The gustatory sensitivity decreases in the order of saltiness > sweetness > sourness or umami > bitterness. The sensor voltage for sweetness and sourness is larger than that for umami and bitterness. The results can be interpreted as follows: From the relationship shown in Figure 10e for Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E, and in Figure 10f,g for ORP and pH, the ORP for sweetness and sourness is higher than that for umami and bitterness, and the pH for umami and bitterness is higher than that for sweetness and sourness. A larger ORP indicates greater oxidizing ability when the oxidation [Ox] level exceeds the reduction level [Red], as expressed in Equation (8). Then, the cationic ions are combined with the anionic polarity of H2O via hydrogen bonding, making the liquid sufficiently kosmotropic to enhance tactile hardness sensitivity. Here, “kosmotropic” refers to the circumstances created by the substance, such as the presence of ions which stabilize the configuration among the molecules involved in aqueous system through interactions such as hydrogen bonds. On the other hand, the closer the pH is to 7, the larger the amount of cationic hydrogen [H+], as expressed in Equation (8). Consequently, [H+] combines with the anionic polarity of H2O through hydrogen bonding, giving the liquid kosmotropic properties and sensitivity to hardness. In contrast, chaotropes lead to sensitivity to tactile softness. Therefore, sweetness and sourness are harder than umami and bitterness, so that the Ra,E, Rq,E, and Ry,E for sweetness and sourness are greater than those for umami and bitterness.

The above estimation is derived from the ORP and pH of the liquids rather than from the Hofmeister series of the liquids. Although further investigation is needed, the potential to enhance the hydrophilic state can be inferred from the ORP and pH values, and this is supported by the hydrophilic paradigm of the Hofmeister effect. Regarding saltiness, other effects may be involved and should be investigated further.

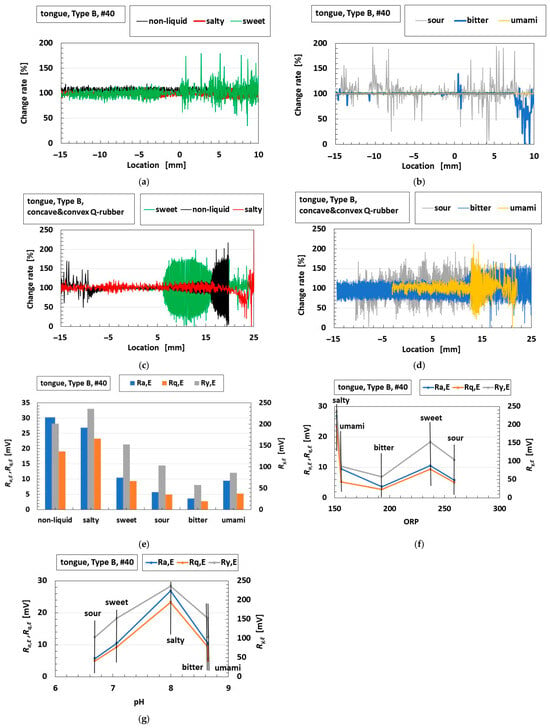

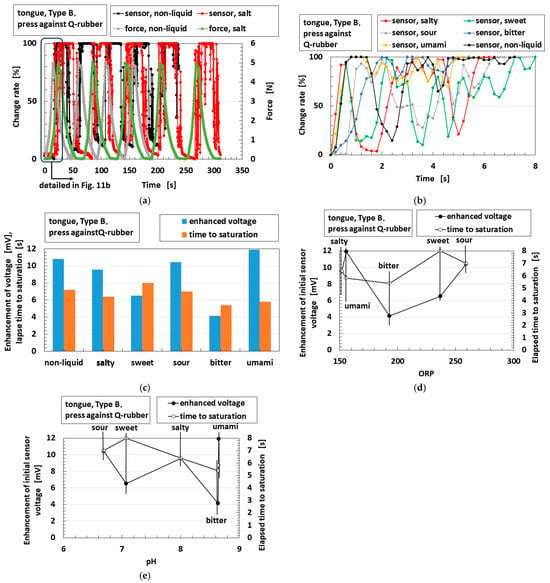

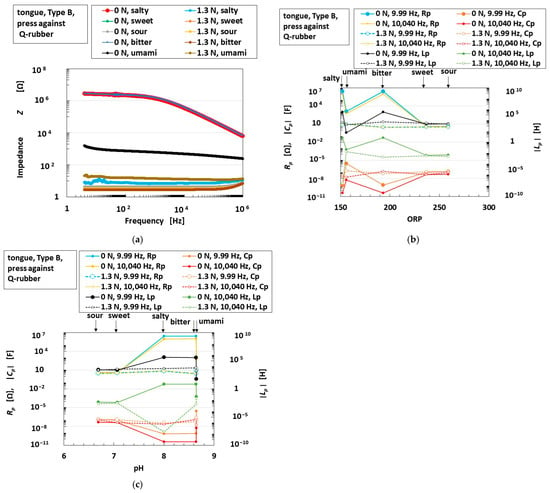

4.4. Synergy of Pressing and Tasting

As another example of synergistic sensitivity, an instance in which an object touches liquid to represent contact with flavored foods is shown in Figure 11a. The tongue presses Q-rubber in liquids with five different tastes, as shown in Figure 2b. For clarity, Figure 11a reports just one taste; the others demonstrate the same qualitative tendency. The detailed change rate in response to the first application of force in Figure 11a is shown in Figure 11b. Further, following on from Figure 11b, the enhancement of the voltage (namely, the voltage change) and the time taken to reach the saturation point of the sensor voltage are shown in Figure 11c. In the cases of sweetness and sourness, these values are larger than those recorded for bitterness. Thus, sweet and sour tastes are presumed to be relevant to hydrophilicity, as shown in Figure 10. However, other tastes have different tendencies. Therefore, based on the impedance measured by EIS, as shown in Figure 12a, we investigated the relationship between the EIS results and ORP or pH, as shown in Figure 12b,c, which present the parameters of Rp, Cp, and Lp at low (9.9 Hz) and high (10,040 Hz) frequencies. These parameters, which are changed by compression, differ according to the kind of taste involved. For bitter, umami, and salty tastes, Rp and Lp decrease under compression, but Cp increases. In contrast, in the cases of sourness and sweetness, the changes under compression are very small. On the other hand, the Rp and Lp for the sour and sweet tastes are smaller than those of the other tastes.

Figure 11.

Correlation of the sensor voltage in response to pressing and tasting with the tongue: (a) the change rate of the sensor voltage over time without liquid and in salty liquids when pressed against soft Q-rubber; (b) the change rate of sensor voltage over time in response to the first press against soft Q-rubber detailed in (a). Correlation of the sensor voltage in response to pressing and tasting: (a) the change rate of the sensor voltage over time without liquid and in salty liquids when pressed against soft Q-rubber; (b) the change rate of the sensor voltage over time in response to the first press against soft Q-rubber detailed in (a); (c) the enhancement of the voltage and the elapsed time until saturation of the voltage without liquid and in liquids with the five tastes when pressed against soft Q-rubber; (d) the effect of ORP on the enhancement of voltage and elapsed time until saturation of the voltage without liquid and in liquids with five tastes when pressed against soft Q-rubber; (e) the effects of pH on the enhancement of voltage and elapsed time until saturation of the voltage without liquid and in liquids with five tastes when pressed against soft Q-rubber.

Figure 12.

Correlation of the sensor voltage in response to pressing and tasting with the tongue: (a) the impedance of the sensor voltage over time without liquid and in salty liquids when pressed against soft Q-rubber; (b) the effects of ORP on Rp, Cp, and Lp without liquid and in liquids embodying the five tastes when pressed against soft Q-rubber; (c) the effects of pH on Rp, Cp, and Lp without liquid and in liquids embodying the five tastes when pressed against soft Q-rubber.

These parameters can be compared to R2,1, C2,1, and L2 in PC, as shown in Figure 7a, because Type B provides OT in Figure 4. From the comparison, we infer that decreasing Rp and Lp, along with increasing Cp, indicates the following: the sensor voltage initially shows a rapid response (which resembles the initial rapid response of FA in Figure 4), but a sustained slow response (which resembles the ultimately long-lasting rough response of SA in Figure 4) is sufficient to correspond to the delayed nature of gustatory sensation. By taking both this inference and the foregoing experimental data into account, we can obtain the typical result as follows.

The enhancement of the voltage and the elapsed time until the saturation of the sensor voltage in the tastes of sourness and sweetness are larger than the corresponding values for bitterness, as shown in Figure 11c. In addition, under compression, the sour and sweet samples exhibit greater voltage enhancement and longer saturation times.

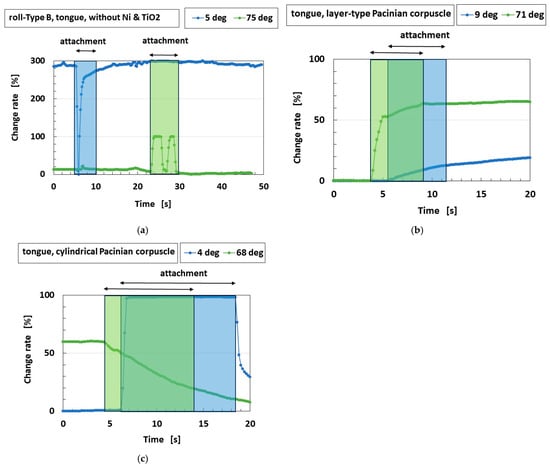

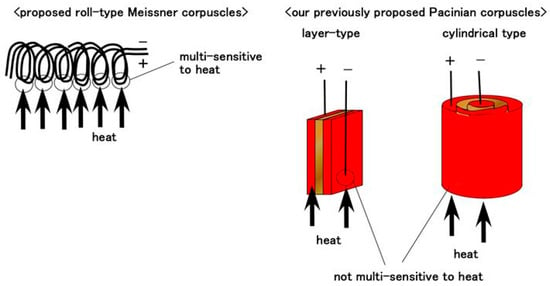

4.5. Thermo Tasting

Gustation also involves thermo-sensitivity, such as that which occurs when drinking a cold or hot beverage. The tongue equipped with Type B receptors was compared with the tongue made with the previously proposed Pacinian corpuscles. The two tongues were dipped in cold water at 4–9 °C or in hot water at 68–75 °C. The experimental apparatus is shown in Figure 2b. Two types of Pacinian corpuscles were used; layer-type and cylindrical ones, which were previously proposed biomimetic sensors without the roll-type configuration and were deemed optimal for thermo-sensitivity [15]. Type B receptors with the roll-type configuration proved sufficiently thermo-sensitive, providing a clear response to the thermal object and showing only small perturbations in the sensor voltage, as shown in Figure 13. In contrast, the sensors without the roll-type configuration only showed a slight enhancement in the change rate upon coming into contact with water and their sensitivities were changed by the temperature of the water. These results can be presumed to be attributed to the physical model, as shown in Figure 14. The roll-type Meissner corpuscles exhibit thermal changes in multiple pairs of built-in voltages created by the spring-like shape in response to multiple thermal stimuli owing to the structure of the coils, whose thermo-performance is greater than that of the sandwiched-layer and cylindrical types used in the previously proposed Pacinian corpuscles.

Figure 13.

The change rate of the sensor voltage when the sensor was dipped in cold or hot water: (a) Type B; (b) the previously proposed layer-type Pacinian corpuscles; (c) the previously proposed cylindrical Pacinian corpuscles; the “attachment” in the figure refers to the period of contact with the cold or hot water.

Figure 14.

A schematic diagram showing the difference in thermo-sensitivity between our proposed roll-type Meissner corpuscles and our previously proposed mechanoreceptors.

5. Conclusions

Soft materials such as rubber possess iontronic characteristics as well as exhibiting electronic behavior, making them feasible for realizing the five senses—tactile, olfactory, gustatory, auditory, and visual sensations. The feasibility is inspired by the versatility of sensation achieved through the biomimetic fabrication of cutaneous mechanoreceptors. The strategic paradigm of biomimetic fabrication is thus crucial for the realization of an artificial sensor. This study demonstrates the gustatory performance of roll-type Meissner corpuscles morphologically mimicked as typical bio-inspired cutaneous receptors, whose haptic performance for variegated dynamic motions was demonstrated previously. The sensor configured with Type B, involving both cationic and anionic reactions, was found to be optimal for gustation, whereas Type A, which involves only cationic reactions, is suited for high-performance tactile and auditory sensing. However, Type B is also capable of multifunctional sensitivity, allowing the tongue to respond to gustatory, tactile, and thermal sensations. The optimum performance and multifunctional potential can be inferred from iontronic characteristics synthesized from reactance and related properties obtained through EIS, C-V profiles, ORP, and pH levels. The synergetic relationship between gustation and tactile sensitivity during shearing or pressing can also be explained by hydrophilic reactions associated with ORP and pH. The experimentally analyzed paradigm integrating EIS, C-V profiles, ORP, and pH levels is crucial, as the performance of the tongue is versatile; it may be used for tasting, experiencing haptic sensation in response to pressing soft or hard objects, shearing across various surface roughnesses, and touching thermal objects.

Thus, the morphology of the biomimetic sensor offers promise for achieving complex sensitivity that accounts for the versatility of the five senses. In addition to the roll-type sensor mimicked by Meissner corpuscles, other sensor configurations involving various shapes, arrays, and materials are expected to be proposed. These developments would further facilitate the advancement of interfaces between human life and robotics. Such interfaces require that several key conditions be considered, including soft materials, wearability, and self-powered systems.

Funding

This work was partially supported by a Suzuki Foundation research grant and by a 25K07676 Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Japan).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author is deeply grateful for the institutional and technical support that made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study. The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

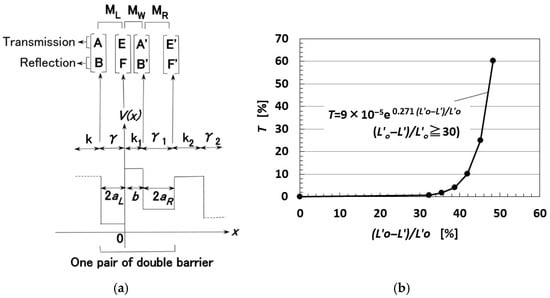

The tunnel theory has been already developed in the analysis of the MCF rubber in our previous study [26,28] as follows. Consider the behavior of electrons transmitted over the potential barrier of rubber as a one-dimensional Schrödinger equation in the x-direction, which is the direction of compression of the MCF rubber. The rubber containing MCF has the same characteristics as the HF rubber. Therefore, the following findings show the same results for HF rubber. The process of transmitting the electric current through a pair of metal regions of γ with a range of 2aL and of γ1 with a range of 2aR, and one rubber region k with a range of b can be considered as a tunnel barrier problem on double barriers, and the diagram of potential energy V is shown in Figure A1a [27,28]. MCF rubber is organized as n pairs of two metal regions and one rubber region. The wave function, Ψ, is presented by Equation (A1), where ħ is the h/2π, h the Planck’s constant, m is the mass of the electron, Vo is the potential energy at regions γ, γ1 or k, and ε is the energy of the electron.

Based on Equation (A1), Ψ is resolved via Equations (A2) and (A3), respectively, for the regions k and γ, where A, B, C, and D are arbitrary constants that can be defined based on the continuity of differential coefficients on the boundary between k and γ (γ1) regions as a well-known ordinary quantum problem, as follows:

where

On the pair of double barriers shown in Figure A1a, the arbitrary constants A and B exist in relation to constants E′ and F′, as shown in Equation (A5).

where

The transmitted probability can be given by Equation (A8).

One pair of double barriers is expanded to n pairs of double barriers as multi-barriers. Therefore, the matrix shown by Equation (A5) is substituted into the matrix of the neighboring pair of double barriers, and this procedure is repeated to obtain the matrix of n pairs of double barriers, where Equation (A9) can be given because the material of each region of k and γ is the same as that of the other regions. Here, 2a is the thickness of metal particles and b is the thickness of rubber between the metal particles. When eEo is the applied voltage, the voltage eE at the regions of γ and k is given as Equation (A9). Therefore, Equation (A5) is calculated by substituting Vo-ε-eEo for Vo-ε of γ in Equation (A4).

k = k1 = k2 = …,

γ = γ1 = γ2 = …,

aL = aR = a

eE = eEo{(2n − 1)a + 2(n − 1)b}/L′ at region of γ before k

eE = eEo{2na + (2n − 1)b}/L′ at region of γ after k

γ = γ1 = γ2 = …,

aL = aR = a

eE = eEo{(2n − 1)a + 2(n − 1)b}/L′ at region of γ before k

eE = eEo{2na + (2n − 1)b}/L′ at region of γ after k

As the thickness of the MCF rubber is divided into n pairs, the thickness of the MCF rubber L′ can be given by Equation (A10):

L′ = nΔL= 2n(a + b) [m]

T is calculated as shown in Figure A1b, where Lo′ is the initial thickness of the MCF rubber, and L′ is the thickness of the MCF rubber in response to the application of the compression force. As the MCF rubber is compressed, T becomes larger (this occurs nonlinearly).

Figure A1.

Theoretical results of the change in the translated ratio of electric current in relation to the compression ratio of the MCF rubber [26,28]: (a) Model of multi potential barrier of the rubber; (b) probability transmitted by compressing.

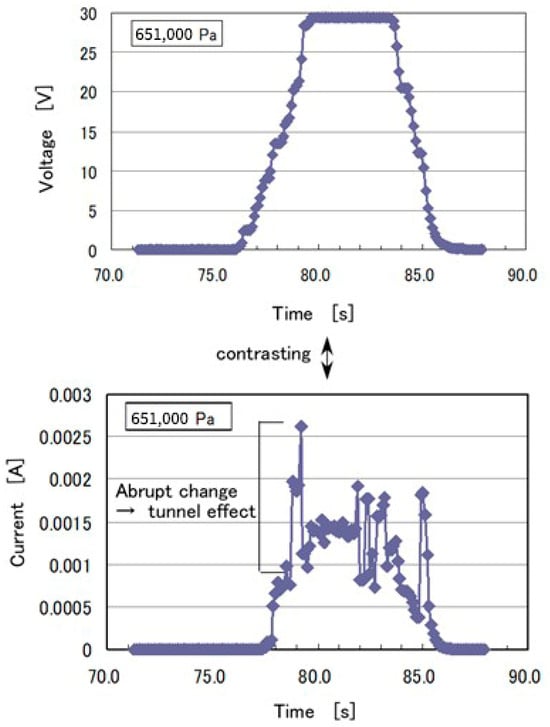

Appendix A.2

The piezo-resistivity was measured via another experiment, in which 30 V voltage was applied to the MCF rubber with about a 15 mm square area and 1 mm thickness. Static pressure was placed on the MCF rubber between the sandwiching electrodes, as shown in Figure A2. The electric current passing through the MCF rubber between the electrodes is shown in the figure. Jumping changes in the current can occasionally be seen in response to high pressing, the addition of a foreign object that is mixed with the MCF rubber during the production process, etc. These jumping changes connote the generated tunneling effect.

Figure A2.

Experimental results of electric current in the case of piezo-resistivity of the MCF rubber.

References

- Song, K.; Shi, D.; Zhao, W.; Gu, Y.; Liu, D.; Chu, P.K. Biomimetic architectures in flexible biosensors: Coordination chemistry-driven design, mechanism, and application. Coordination Chem. Rev. 2026, 548, 217195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Zhai, W. Wearable soft actuation systems for human–machine–environment interactions. Mat. Today 2025, 59, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Wu, H.; Guo, F.; Fu, J.; Li, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhang, M.; Luo, C.; Long, Y. A novel 3D-Printed self-healing, touchless, and tactile multifunctional flexible sensor inspired by cutaneous sensory organs. Compos. Commun. 2025, 54, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yao, K.; Jia, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X. Advances in materials for haptic skin electronics. Matter 2024, 7, 2826–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ahn, J.H. Rational design of high-performance wearable tactile sensors utilizing bioinspired structures/functions, natural biopolymers, andbiomimetic strategies. Mat. Sci. Eng. R 2022, 148, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H.U.; Jahan, I.; Imran, A.B. Bio-inspired nanomaterials for micro/nanodevices: A new era in biomedical applications. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, R.; Gemming, T.; Bachmatiuk, A.; Zhao, H.; Jia, H.; Huang, S.; Zhou, W.; Xu, J.B.; et al. Boosting flexible electronics with integration of two-dimensional materials. InfoMat 2024, 6, e12555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanarse, A.; Osseiran, A.; Rassau, A. An investigation into spike-based neuromorphic approaches for artificial olfactory systems. Sensors 2017, 17, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Hu, J.; Wang, B.; Xia, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.H.; Lu, Y. Biomimetic wearable sensors: Emerging combination of intelligence and electronics. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2303264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zeng, X.; Huang, J.; Wen, Y.; Brugger, J.; Zhang, X. All-printed finger-inspired tactile sensor array for microscale texture detection and 3D reconstruction. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2400479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Li, Z.; Pang, J.; He, P.; Zhang, S. Latest developments and tends in electronic skin devices. Soft Sci. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, D.; Im, G.B.; Lee, Y. A review on soft ionic touch point sensors. Energy Environ. Mater. 2024, 7, e12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, F.; Ding, Z.D.; Yang, X.; Chu, F.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Jin, H.; Dong, S.; Wang, X.; Luo, J. Advanced morphological and material engineering for high-performance interfacial iontronic pressure sensors. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2413141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tan, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Cai, J.; Liu, Y. Design strategies and emerging applications of conductive hydrogels in wearable sensing. Gel 2025, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K. Novel Cutting-edge tactile sensor morphologically configured by biomimetics of roll type Meissner receptor for dynamic performance. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 817, To be printed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toko, K. Research and development of taste sensors as a novel analytical tool. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2023, 99, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuno, T.; Morimoto, S.; Nishikawa, H.; Haraguchi, T.; Kojima, H.; Tsujino, H.; Arisawa, M.; Yamashita, T.; Nishikawa, J.; Yoshida, M.; et al. Bitterness-suppressing effect of umami dipeptides and their constituent amino acids on diphenhydramine: Evaluation by gustatory sensation and taste sensor testing. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanaga, Y.; Mukai, J.; Mukai, T.; Odomi, M.; Uchida, T. Suppression of the bitterness of enteral nutrients using increased particle sizes of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and various flavours: A taste sensor study. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 54, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, A.; Eren, B.A.; Zaukuu, J.L.Z.; Koris, A.; Huszar, K.P.; Szerdahelyi, E.; Kovacs, Z. Detecting the bitterness of milk-protein-derived peptides using an electronic tongue. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhu, P.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Du, L.; Wu, C. A taste bud organoid-based microelectrode array biosensor for taste sensing. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, Q.; Du, A. Self-powered flexible sour sensor for detecting ascorbic acid concentration based on triboelectrification/enzymatic-reaction coupling effect. Sensors 2021, 21, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, F.A. Bioreceptor-inspired soft sensor arrays: Recent progress towards advancing digital healthcare. Soft Sci. 2023, 3, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, M.; Jiang, N.; Zhuang, L.; Huang, L.; Wang, P. A cell co-culture taste sensor using different proportions of Caco-2 and SH-SY5Y cells for bitterness detection. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Tan, H.; Gustavsson, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Q.; Ikkala, O.; Peng, B. Gustation-inspired dual-responsive hydrogels for taste sensing enabled by machine learning. Small 2024, 20, 2305195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K. Elucidation of response and electrochemical mechanisms of bio-inspired rubber sensors with supercapacitor paradigm. Electronics 2023, 12, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K. Elastic MCF rubber with photovoltaics and sensing on Hybrid Skin (H-Skin) for Artificial Skin by Utilizing Natural Rubber: Third report on electric charge and storage under tension and compression. Sensors 2018, 18, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.; Lee, G.; Lee, M.G.; Hwang, H.J.; Lee, K.; Lee, Y. Bio-inspired ionic sensors: Transforming natural mechanisms into sensory technologies. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K. Quantum mechanical investigation of the electric and thermal characteristics of magnetic compound fluid as a semiconductor on metal combined with rubber. ISRN Nanotech. 2011, 2011, 259543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K. Elastic MCF rubber with photovoltaics and sensing for use as artificial or hybrid skin (H-Skin): 1st report on dry-type solar cell rubber with piezoelectricity for compressive sensing. Sensors 2018, 18, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Gao, J.; Yu, Z. Orchestrating mechanics, perception and control: Enabling embodied intelligence in humanoid robots. Info. Process. Manag. 2026, 63, 104363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Tang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Song, S. Hofmeister series: Insights of ion specificity from amphiphilic assembly and interface property. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 6229–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).