Abstract

Traditional acoustic seabed classification methods, which are often sensitive to survey geometry and environmental conditions, have limitations in reliability and reproducibility. This study presents a novel physics-guided machine learning framework for automated sediment classification that leverages frequency-dependent acoustic reflection spectra. The framework, tested on two representative sediment types of poorly graded sand (SP) and poorly graded gravel (GP) in controlled laboratory conditions across a frequency range of 100–400 kHz, corrects water-column attenuation and isolates intrinsic sediment responses. Unlike earlier studies that focused solely on attenuation modeling or demonstrated spectral separability without statistical validation, this study embeds physics-guided corrections into a machine-learning pipeline, enabling automated, statistically validated sediment discrimination. Reflection spectra were acquired from 200 samples (100 per class) at 31 frequencies, forming a dataset for classifier evaluation. Random Forest (RF) and Logistic Regression (LR) were benchmarked under identical protocols. RF outperformed LR, achieving peak accuracy of 90% in optimal frequency windows (180–220, 310–350, and 330–370 kHz) and 84% across the full spectrum, compared to LR’s maxima of 82% and 80%. Feature importance revealed that discriminative bands align with wavelengths approximating grain sizes, indicating resonance-like mechanisms. The physics-guided approach demonstrated in this study offers reliable discrimination of sediments with similar grain sizes but different gradations, overcoming a limitation of intensity-only methods. The improved accuracy and interpretability of the classification results have significant implications for future marine survey methods, suggesting that the proposed framework could be a valuable tool for enhancing the efficiency and reliability of seabed characterization. Looking ahead, the potential practical applications of this research are significant, including field trials with autonomous sonar platforms and integration into remote sensing workflows. These applications will be essential to validate the robustness of the approach under real-world variability, paving the way for scalable, real-time seabed classification with implications for a wide range of marine research and applications.

1. Introduction

1.1. State of the Art

Acoustic remote sensing techniques have become indispensable for seafloor studies and mapping, providing a non-invasive, efficient alternative to traditional sampling methods such as coring or grab sampling. These methods are now widely employed in various marine applications, including bathymetric mapping of the ocean floor, shallow and deep sub-bottom profiling, identification of buried and exposed underwater infrastructure, and underwater positioning systems. Their versatility and operational efficiency have made them standard in both environmental and geotechnical marine investigations [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. In contrast to traditional techniques, underwater acoustics enable broad-area, in situ characterization of seabed properties without physical disturbance, aligning with the principles of sustainable and green engineering. As part of a global shift toward environmentally responsible marine technologies, the use of acoustic-based non-destructive testing (NDT) methods reflects the growing emphasis on reducing ecological footprints while enhancing data acquisition capabilities [13,14,15].

The application of acoustic methods, especially sonar-based systems, has seen significant advancements in recent decades. Initial implementations relied on single-beam echo sounders, which later evolved into side-scan sonar (SSS) and multibeam echo sounders (MBES), improving spatial resolution and enabling near-continuous seafloor coverage [15,16,17,18,19,20]. These systems generate acoustic reflections from the seabed, which are interpreted to infer the substrate’s composition and structure. For example, it has been demonstrated that variations in backscatter intensity correlate with changes in sediment grain size, allowing for a basic classification of sediment types [10,21,22,23,24].

Despite significant advancements, conventional methods for seabed characterization often fall short because they rely on intensity-based metrics that are sensitive to survey conditions and environmental factors. This sensitivity introduces uncertainty in classification results, particularly in complex or heterogeneous environments [13,14,25,26,27]. Side-scan sonar imagery, although effective for large-scale mapping, typically requires manual interpretation and offers limited capacity to distinguish between materials with similar acoustic textures [4,8,13,15,28]. Similarly, MBES systems, although capable of collecting both bathymetric and backscatter data, face challenges due to the angular dependency of the returned signal. Even with calibration tools like the Geocoder algorithm, it remains challenging to isolate the intrinsic acoustic response of the seabed from external influences [15,16,17,29]. As a result, the current standard in seafloor characterization still lacks a thoroughly reliable, quantitative classification method, particularly for diverse or mixed sediment types such as sand, rock, and clay. Most studies continue to rely on calibrated backscatter intensity as a primary indicator, often with significant site-specific adjustments [10,22,23,27,29,30,31]. Although these approaches can be practical in relatively homogeneous environments, they consistently struggle to maintain accuracy across heterogeneous seabed conditions [15,28]. This persistent limitation underscores the urgent need for a more reliable, quantitative classification method in seabed characterization, which the physics-guided machine learning framework presented in this study aims to address.

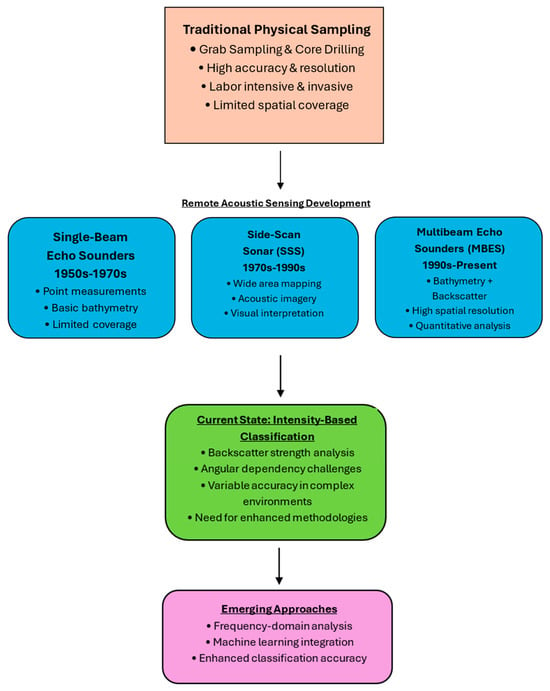

Figure 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the technological evolution in acoustic seabed characterization, summarizing the progression from traditional invasive sampling methods through the development of remote acoustic sensing technologies and illustrating the current state of intensity-based classification methods that form the foundation for identifying existing limitations.

Figure 1.

Evolution of acoustic seabed characterization technologies.

As illustrated in Figure 1, while each technological advancement has significantly improved spatial coverage and operational efficiency over its predecessors, the current reliance on intensity-based backscatter analysis still presents fundamental challenges in classification accuracy and environmental adaptability. These technological limitations, despite decades of development, create the knowledge gaps that this research aims to address.

To address these limitations, a growing body of research suggests that frequency-dependent analysis of acoustic signals, also known as spectral analysis, may offer a more robust alternative. Unlike traditional approaches that focus solely on signal intensity, spectral methods examine how various seabed materials reflect different frequencies of acoustic energy. These frequency-specific acoustic “fingerprints” can provide deeper insights into the substrate’s physical properties, such as porosity, layering, and grain-size distribution [2,6,8,10,13,21,22,32,33]. Recent studies have shown that even materials with similar total backscatter intensities can exhibit distinct spectral profiles, enabling more precise classification [8,13,21]. However, spectral approaches remain underutilized in marine research. Many previous efforts have focused on large-scale side-scan data or have been limited to specific sonar systems and frequency bands, thereby constraining their generalizability. Moreover, there is a lack of statistically validated classifiers that can reliably differentiate between seabed types based on spectral characteristics across varied environmental conditions [1,13,33,34,35].

In particular, multi-frequency MBES work in Remote Sensing demonstrates that the choice of frequency and penetration depth materially changes which portion of the seabed/subsurface is sensed, making spectral information discriminative and physically grounded [36].

Given the limitations of traditional acoustic classification, recent advances in artificial intelligence offer transformative potential for overcoming these challenges, with the integration of AI into acoustic analysis presenting a promising pathway forward. Machine learning algorithms, including support vector machines and deep neural networks, have shown the potential to enhance classification accuracy by identifying complex, nonlinear patterns in multidimensional acoustic datasets [25,32,34,35,37,38]. This study compares ensemble methods (Random Forest) explicitly with traditional statistical approaches (Logistic Regression) to evaluate their relative effectiveness in spectral-based sediment classification. Studies using convolutional neural networks and hybrid architecture have reported classification accuracies exceeding 90% in some cases, particularly when applied to multibeam echo sounder data combined with angular and textural features [25,37,38]. Despite these successes, most approaches still rely heavily on backscatter intensity or require extensive site-specific training data, limiting their broader applicability [16,27,35].

Building on the above review, a central requirement for reliable, scalable seabed characterization is a classifier that (i) is robust to covariate shifts induced by survey geometry and environmental variability; (ii) operates effectively on tabular, frequency-dependent features without large site-specific training sets; and (iii) remains interpretable at the level of frequency bands to preserve a physics-based understanding of sediment discrimination. These constraints motivate a statistics-driven approach, grounded in ensemble learning—specifically, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm—which is well-suited to high-dimensional, noisy acoustic data, while providing band-level importance measures that inform physical interpretation [39,40,41].

This research involves developing a robust, scalable classification framework for seabed characterization grounded in statistical learning theory. Specifically, this study implements the Random Forest (RF) algorithm as the core classification tool. Breiman first introduced Random Forest [40] as a general-purpose machine learning method that combines the predictions of multiple decision trees. Each tree is trained on a bootstrapped subset of data, and random feature subsets are selected at each decision split to introduce decorrelation between trees. This dual-randomization across both samples and features is the foundation of RF’s superior generalization and resilience to overfitting, especially compared to single-tree models or parametric classifiers [42,43,44].

Unlike classical models that rely on predefined distributional assumptions or manual feature engineering, RF can learn complex, nonlinear decision boundaries adaptively, making it well-suited for high-dimensional problems where the underlying data structure is unknown. In the context of seabed classification, where diverse environmental factors influence acoustic responses, RF’s flexibility offers a considerable advantage. It can learn intricate relationships between input features and output classes without requiring domain-specific tuning or prior knowledge of distributional patterns [37,45].

The relevance of statistical learning models for seabed classification has grown in recent years, as demonstrated in the broader literature. Ma et al. [46] applied convolutional neural networks (CNNs), including LeNet, AlexNet, and VGG, to multibeam acoustic backscatter data, achieving a classification accuracy of over 92%. Their use of DCGAN-based data augmentation further improved results, underscoring the importance of statistical feature extraction and model generalization. Similarly, Zhu et al. [47] integrated high-resolution acoustic and magnetic data within a deep neural network framework to classify complex lithologies such as basalt, breccia, and sediment, achieving notable improvements in both accuracy and Cohen’s kappa. These studies highlight the potential of data-driven approaches and reinforce the suitability of Random Forests as a more interpretable, computationally efficient alternative for automated seabed classification.

Another key strength of the Random Forest method lies in its built-in mechanisms for internal validation and model evaluation. Each tree in the forest is trained on approximately two-thirds of the dataset, leaving the remaining one-third, known as the out-of-bag (OOB) data, for unbiased performance estimation. This OOB error provides a reliable and efficient proxy for cross-validation, enabling real-time assessment of the model’s predictive accuracy without the need to hold out separate test sets [40,47,48].

Moreover, Random Forests provide valuable insight into variable importance. By measuring the decrease in classification accuracy when each input feature is permuted, the algorithm ranks features according to their influence on the model’s decisions. This capability enhances interpretability, allowing researchers to identify which acoustic or environmental variables most strongly influence the classification of seabed types [41,48,49].

In addition to its statistical merits, RF also offers a green engineering advantage. Because the model generalizes well from limited training data and tolerates noisy or incomplete inputs, it reduces the need for extensive physical sampling campaigns or large annotated datasets, two resource-intensive components of conventional marine survey workflows. This aligns with the study’s broader commitment to sustainable marine characterization practices, as introduced in Section 1.1 [50]. This computational efficiency also translates to reduced energy consumption during data processing, further supporting the environmental sustainability goals of this research.

Finally, compared to alternative classifiers such as support vector machines or deep neural networks, Random Forests strike a practical balance between accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency. They are less sensitive to hyperparameter tuning, require shorter training times, and perform well even when the input data are partially missing or contain redundant features [44,51]. These properties make RF particularly suitable for integration into automated seabed classification pipelines, where operational robustness and real-time performance are vital.

Current machine learning applications in seabed classification lack integration with physical acoustic models and comprehensive validation frameworks. While ensemble methods, such as Random Forest, offer advantages in interpretability and computational efficiency compared to deep learning approaches, most existing applications still rely on site-specific training data without incorporating physics-based corrections, such as attenuation modeling. The integration of physically meaningful acoustic features with data-driven algorithms represents an underexplored approach that could serve as a scalable and sustainable solution for real-time sediment classification, potentially enabling broader deployment in autonomous marine survey systems [52].

Building on two recent advances—(i) the regression-based correction model for frequency-dependent attenuation [53] and (ii) the demonstration of distinct acoustic spectral signatures for sediments in controlled aquatic environments [54]—this study is the first to operationalize a physics-guided machine learning classifier. Unlike previous works, this study systematically benchmarks RF and LR models, quantifies accuracy across frequency bands, and links model saliency to acoustic mechanisms, thereby bridging the gap between physical modeling and automated classification.

1.2. Knowledge Gaps

Despite decades of progress, several critical gaps prevent reliable, generalizable automation:

- Confounding of intensity-based features: Backscatter intensity remains sensitive to incidence angle, roughness, and water-column variability; even with calibration (e.g., Geocoder), isolating the intrinsic seabed response is difficult, limiting cross-site reproducibility [15,16,17,25,26,27,29].

- Limited physics-guided ML: ML pipelines rarely incorporate attenuation/source normalization or acoustic priors, which reduces their robustness and interpretability. Physics-guided scientific ML is a promising but underutilized approach in this domain [35,37,50,53,54].

- Fine discrimination of similar sediments: There is no statistically validated, automated framework that utilizes frequency-dependent reflection spectra to distinguish sediments with similar representative grain sizes but different grading characteristics under controlled cross-condition validation [21,32,33,54].

Building on our prior works that (i) introduced a regression-based attenuation/source-strength correction for 100–400 kHz acoustics and (ii) documented frequency-dependent reflection behavior in a controlled aquatic setting, this study delivers the first physics-guided machine-learning classifier for seabed sediments using corrected spectral fingerprints. We benchmark Random Forest against Logistic Regression, achieving a peak accuracy of 90%, and identify optimal frequency bands linked to wavelength–grain scale interactions, thereby translating spectral physics into deployable, band-targeted survey strategies. This closes the gap between physical signal correction and automated, interpretable classification.

Looking ahead, these advances lay the foundation for integrating explainable, physics-informed machine learning into scientific sensing domains. The methodology connects physical signal understanding with robust classification logic, positioning ML not just as a black-box predictor but as a knowledge extraction tool. By demonstrating generalizable performance under controlled conditions, this framework contributes to ongoing efforts in interpretable AI, spectral learning, and physics-guided classification, key themes in modern machine learning research. It offers a scalable, transparent approach for the future development of autonomous environmental systems, where explainability, efficiency, and robustness are essential.

1.3. Research Objectives

To address these gaps, this study pursues four objectives:

- Model development and benchmarking: Implement and compare Random Forest (primary) and Logistic Regression (baseline) trained on coherent, frequency-dependent reflection features measured under controlled aquatic conditions.

- Physics-guided feature construction: Integrate attenuation correction and source-strength normalization to stabilize spectral features across acquisition settings; quantify their contribution to accuracy and generalization.

- Band-level interpretability and selection: Identify informative frequency bands via RF importance and ablations; relate discriminative bands to plausible acoustic mechanisms (e.g., grading-linked impedance contrasts).

To summarize, non-invasive acoustic sensing has transformed seabed mapping but remains constrained by intensity-only metrics that are highly sensitive to acquisition conditions. Spectral (frequency-dependent) analysis offers richer, physics-linked descriptors but is underexploited and seldom integrated with physics-guided ML. This work advances the field by constructing a robust, interpretable Random Forest framework over coherent reflection spectra corrected for attenuation and source strength. The framework achieves validated discrimination of similar grain-size sediments with different grading characteristics, representing key steps toward scalable, sustainable, near-real-time seabed classification.

2. Materials and Methods

This study implements a physics-guided machine learning framework for frequency-dependent acoustic classification of seafloor sediments. The methodology builds upon two foundational stages established in previous research: (1) development of a physics-informed regression model for acoustic source strength estimation under frequency-dependent attenuation [53] and (2) controlled laboratory acquisition of spectral reflectance profiles for representative sediment types [54]. This section presents the integrated experimental and computational approach, emphasizing the dataset construction and machine learning implementation that form the core contribution of this work.

2.1. Physics-Guided Acoustic Reflection Modeling

The classification approach employs frequency-dependent acoustic reflection analysis to distinguish between sediment types. The methodology measures how acoustic energy is modified as it interacts with different sediments over a frequency range of 100–400 kHz.

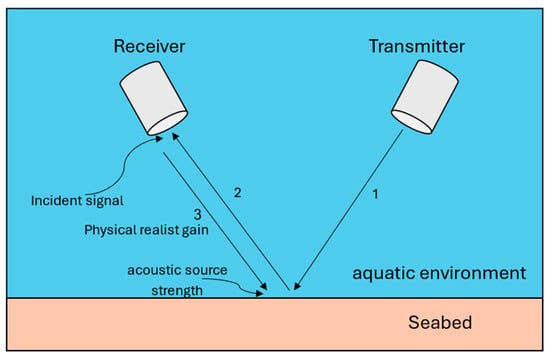

Figure 2 provides a conceptual overview of the acoustic sediment classification principle, illustrating the key energy transformations that occur during the measurement process. The diagram shows the complete energy pathway: (1) acoustic energy transmitted from the source propagates through the aquatic environment; (2) interacts with the seabed surface, where reflection, absorption, and scattering occur based on sediment properties; and (3) returns as a modified signal that has undergone additional water-column attenuation during the return path to the receiver.

Figure 2.

Conceptual flow chart illustrating acoustic wave propagation during seabed reflection analysis. The diagram depicts (1) transmission of acoustic energy through the aquatic environment; (2) interaction with the seabed and return to the receiver; and (3) application of physics-based gain correction to estimate the true acoustic source strength. This schematic underpins the physics-guided modeling of frequency-dependent reflections, forming the foundation for feature extraction and classification in machine learning frameworks for seabed analysis.

The fundamental challenge illustrated in this diagram is that the measured signal represents the cumulative effect of both sediment interaction and twice-propagated water-column effects, once on the downward path and again on the return journey. This water-column attenuation varies significantly with frequency due to geometric spreading and absorption, masking the sediment’s intrinsic acoustic signature. To address this challenge, a physics-based correction model was developed in previous research [53] to estimate the true energy leaving the sediment surface (step 3 to step 2 reconstruction), thereby isolating the sediment-specific acoustic response from propagation artifacts. This correction framework, detailed in Section 2.2, enables accurate quantification of frequency-dependent reflection characteristics for reliable sediment classification.

2.1.1. Energy Parameters and Physical Principles

Four key energy parameters form the foundation of the spectral analysis:

Incident Energy (): The total acoustic energy propagating through water and reaching the sediment surface at a given frequency, measured in the absence of sediment using direct transmission between transducers.

Received Energy (): The attenuated acoustic energy recorded at the receiver after interaction with the sediment, accounting for both reflection losses and water-column attenuation during propagation.

Source Energy (): The estimated acoustic energy leaving the sediment surface requires reconstruction from the received signal through physics-based corrections that account for geometric spreading and frequency-dependent absorption effects.

Reflection Coefficient (R): The ratio representing the frequency-dependent acoustic reflectivity of the sediment, serving as the primary spectral feature for classification.

2.1.2. Experimental Challenges in Acoustic Measurements

A critical challenge in underwater acoustic measurements is that the recorded signal Iᵢ represents attenuated energy that has propagated through water, not the actual energy I0 leaving the sediment surface. Water-column attenuation varies significantly with frequency due to:

- Geometric spreading: Energy distributed over an increasing spherical wavefront area.

- Absorption effects: Frequency-dependent viscous losses and molecular relaxation.

- Near-field behavior: Deviations from ideal propagation at short distances.

Without correcting for these effects, the measured reflection coefficients would conflate sediment properties with propagation artifacts, compromising classification accuracy. Therefore, a physics-informed model is required to reconstruct I0 from Iᵢ.

2.2. Physics-Guided Attenuation Correction

2.2.1. Theoretical Foundation

The correction methodology was developed in previous work [53] based on acoustic transmission loss theory. The approach employs nonlinear regression to model the relationship between transmitted and received energy, accounting for both geometric and absorption losses in freshwater environments.

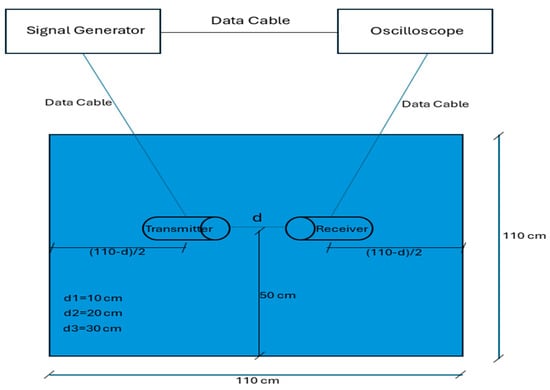

The attenuation model calibration required precise acoustic measurements using specialized ultrasonic equipment. Figure 3 shows the complete experimental apparatus used for data acquisition, including the water tank setup, ultrasonic transducers, signal generator, and digital oscilloscope. The signal generator produces controlled, monochromatic acoustic pulses across the 100–400 kHz frequency range. At the same time, the digital oscilloscope records the received waveforms with the high temporal resolution required for accurate energy calculations.

Figure 3.

Experimental water-tank setup used for calibrating frequency-dependent attenuation. The controlled laboratory geometry enables repeatable acoustic measurements across multiple frequencies and sediment types. This setup supports the extraction of physically meaningful features for training machine learning models under well-defined propagation conditions.

Figure 4 presents the schematic configuration used for calibrating the physics-informed regression model. The diagram illustrates the face-to-face transducer arrangement and measurement geometry that enabled systematic characterization of frequency-dependent attenuation effects across multiple propagation distances. This controlled setup provided the training data needed to develop the correction equations.

Figure 4.

Schematic setup for calibration of the physics-guided regression model. The configuration enables precise control over acoustic propagation paths for multiple transmitter–receiver distances. This controlled setup supports the development and validation of data-driven models that incorporate physical attenuation principles, forming the foundation for robust machine learning feature engineering.

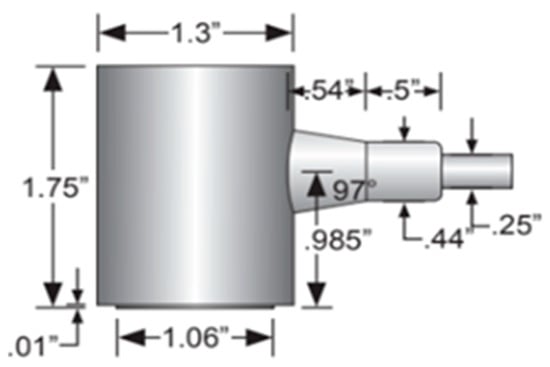

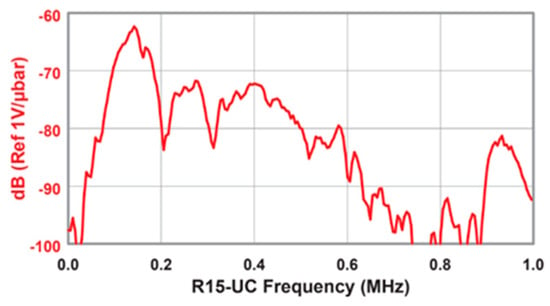

The ultrasonic transducers employed in this study have specific dimensional and performance characteristics that influence the acoustic measurements. Figure 5 shows the detailed transducer specifications, including the 1.06-inch diameter and geometric properties. Additionally, Figure 6 presents the frequency response characteristics of the transducers, demonstrating their sensitivity across the 100–400 kHz operating range. These specifications ensure an adequate signal-to-noise ratio and consistent performance throughout the tested frequency band.

Figure 5.

Dimensions of the ultrasonic transducers (MISTRAS Group, West Windsor Township, NJ, USA).

Figure 6.

Frequency response of the ultrasonic transducers across 100–400 kHz (MISTRAS Group, NJ, USA).

2.2.2. Correction Model Implementation

The corrected source energy I0 is estimated from the received energy Iᵢ using the calibrated relationship:

where

- Ri = propagation distance between transducer and sediment surface;

- = acoustic frequency;

- – = trained coefficients determined through controlled water-tank experiments [53].

The model incorporates terms for geometric spreading (), frequency-squared absorption (), and interaction effects () to capture complex attenuation behavior.

Table 1 lists the calibrated regression coefficients (C1–C7), while Table 2 provides the complete set of normalization parameters required for implementing the correction model.

Table 1.

Trained coefficients for the physics-guided correction model.

Table 2.

Normalization parameters for feature standardization.

All features in Equation (1) are z-score normalized using:

where μ and σ denote the mean and standard deviation computed exclusively from the water-tank calibration dataset used to train the model, these normalization parameters were extracted once during the calibration stage and stored (Table 2). When applying the correction model to the sediment-reflection experiments, the same μ and σ values are used to normalize the input features, ensuring that the sediment data lie within the same standardized feature space as the calibration data.

This guarantees methodological consistency and prevents information leakage from the sediment dataset into the model training stage.

Repeated optimization runs (n = 20) with different random initializations yielded identical coefficient values (±0.0001), indicating strong model robustness and a unique stable minimum.

2.3. Sediment Materials and Characterization

Sediment Selection and Properties

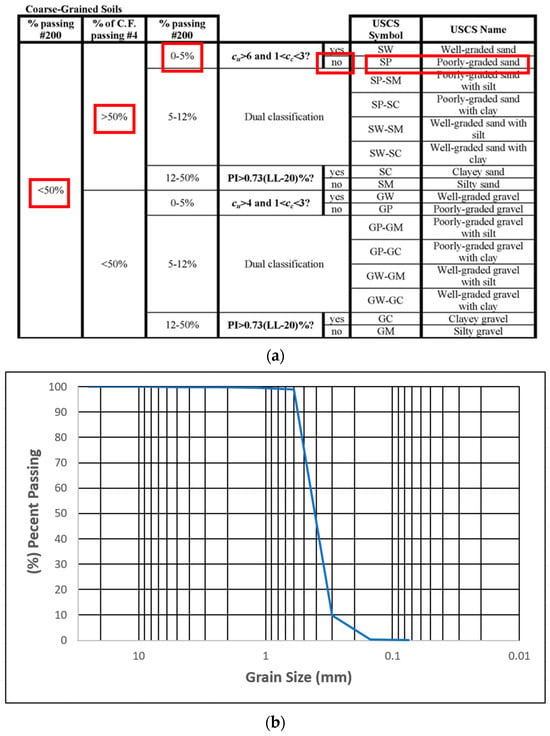

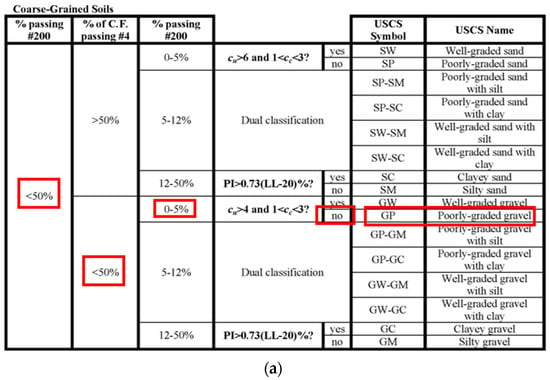

Two representative sediment types were selected based on their acoustic contrast and marine relevance: poorly graded sand (SP) and poorly graded gravel (GP). Comprehensive geotechnical characterization was performed in previous work [Greenberg et al. [53,54], 2025b] using standard sieve analysis, as per the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS).

Poorly Graded Sand (SP): Quartz-based, sub-angular particles with D10 = 0.30 mm, D50 = 0.40 mm, and D60 = 0.45 mm. The uniformity coefficient Cᵤ = 1.50 and coefficient of curvature Cc = 0.91 confirm the USCS classification as SP.

Poorly Graded Gravel (GP): Sub-rounded limestone fragments with D10 = 2.8 mm, D50 = 5.4 mm, and D60 = 6.0 mm. The uniformity coefficient Cᵤ = 2.14 and coefficient of curvature Cc = 0.95 confirm the USCS classification as GP.

The grain-size distribution curves in Figure 7 and Figure 8 demonstrate the distinct gradation characteristics of the two sediment types. These curves show the percentage of material passing through different sieve sizes, clearly illustrating the finer, more uniform distribution of the SP compared to the coarser, more varied particle sizes of the GP. The accompanying tables provide detailed sieve analysis results that quantify the gradation parameters used for USCS classification.

Figure 7.

(a) Grain size distribution curve for SP soil and (b) acceptance result table.

Figure 8.

(a) Grain size distribution curve for GP soil and (b) acceptance result table.

The distinct gradation characteristics and material compositions of these sediments provide the physical basis for acoustic discrimination through frequency-dependent reflection properties.

2.4. Spectral Data Acquisition and Dataset Construction

2.4.1. Experimental Setup

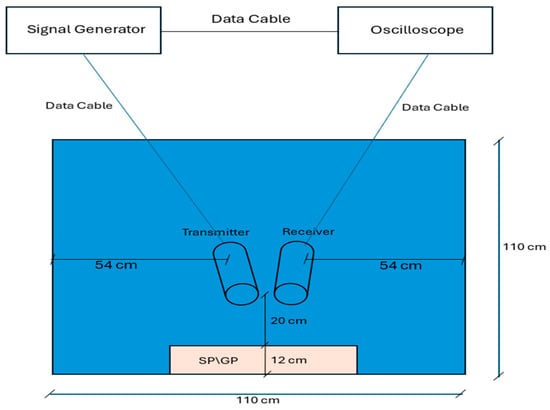

Spectral measurements were obtained using an ultrasonic transmission–reflection system with two transducers (MISTRAS Group, West Windsor Township, NJ, USA, 1.06-inch diameter) positioned 20 cm above sediment samples in a controlled water tank.

Figure 9 illustrates the experimental configuration for sediment acoustic measurements, depicting both transducers oriented downward toward the sediment surface, which is placed at the tank bottom. This setup differs from the face-to-face arrangement used for attenuation calibration, as it is specifically designed to capture reflected acoustic signals from the sediment–water interface while maintaining consistent geometry and far-field acoustic conditions.

Figure 9.

The experimental setup for performing acoustic readings for SP and GP soils.

This configuration ensured far-field acoustic conditions while maintaining temporal separation between direct arrivals and boundary reflections. The 20 cm standoff distance corresponds to far-field operation for all tested frequencies (100–400 kHz).

2.4.2. Data Collection Protocol

For each sediment type, acoustic measurements were acquired at 100 distinct spatial locations within continuous sediment layers, providing realistic spatial variability. At each measurement point, 31 monochromatic signals were transmitted at center frequencies ranging from 100 to 400 kHz in 10 kHz increments, yielding 3100 individual acoustic readings per sediment type (100 locations × 31 frequencies).

The measurement protocol involved:

- Incident energy measurement: I1(f) determined through direct transmission experiments in water without sediment.

- Reflected signal recording: Ii(f) measured after acoustic interaction with sediment surface.

- Source energy reconstruction: I0(f) calculated using Equation (1).

- Reflection coefficient computation:

2.4.3. Dataset Structure

The compiled dataset consists of 200 samples (100 per sediment type) forming the design matrix:

where each entry represents the reflection coefficient for sample i at frequency . Each row constitutes a complete spectral fingerprint capturing the frequency-dependent acoustic response. The corresponding label vector:

encodes ground truth classification (yi = 0 for SP, yi = 1 for GP).

In total, the dataset comprises 200 labeled spectral samples, 100 per sediment type. Each is constructed directly from 31 physically measured acoustic frequencies. These samples originate from 6200 independent laboratory-acquired waveforms (3100 per sediment type), with no synthetic augmentation, replication, or artificial expansion applied at any stage. This ensures that all training and evaluation procedures rely solely on real, experimentally measured data. The sample-to-feature ratio (n ≫ p) satisfies statistical learning requirements, and the dataset represents a substantial increase over prior spectral studies that typically analyzed fewer than 50 experimental runs [21,32], enabling a more rigorous and statistically grounded classification analysis.

2.5. Machine Learning Implementation

This section outlines the machine learning framework used to classify the sediment types (SP, GP) based on their frequency-dependent reflection spectra. The workflow integrates physics-based feature construction, fold-wise preprocessing, and a statistically robust validation strategy, ensuring reproducibility and methodological transparency.

2.5.1. Classification Algorithms

Two supervised classifiers were implemented to evaluate the discriminative power of the spectral reflection matrix:

Logistic Regression (LR): Used as a baseline due to its interpretability and linear decision boundary assumptions. LR is sensitive to feature scaling and, therefore, requires standardized inputs.

Random Forest (RF): Employed as the primary classifier. RF leverages bootstrap aggregation, nonlinear decision boundaries, and built-in feature-frequency importance estimation, making it well-suited to tabular spectral data and reducing the risk of overfitting.

2.5.2. Feature Scaling Considerations for Spectral Features

Unlike the physical variables used in the attenuation–correction model, the spectral features employed in the classification stage (I0/I1) are dimensionless ratios that share a consistent physical scale across frequencies.

As such, no additional normalization is required to equalize feature magnitudes, since all spectral components inherently reside within a comparable numerical range and represent physically meaningful quantities.

This distinction ensures that the spectral matrix retains its physical interpretability while still enabling effective learning by models such as RF.

Although the spectral features themselves do not require normalization from a physical standpoint, Logistic Regression does require feature scaling for numerical stability; this preprocessing is therefore applied separately and described in Section 2.5.3.

2.5.3. Feature Normalization for Logistic Regression

Logistic Regression requires feature scaling to ensure numerical stability, proper gradient descent convergence, and balanced coefficient magnitudes.

Therefore, all spectral features were standardized using z-score normalization (as in Equation (2)). To prevent information leakage, preprocessing was conducted within each fold of the cross-validation scheme:

- μ and σ were computed exclusively from the training subset;

- The same μ and σ were applied to the fold’s validation subset;

- No information from the validation portion was used during normalization or model fitting.

This fold-wise scaling procedure ensures a fully reproducible and unbiased evaluation.

2.5.4. Cross-Validation Strategy (Primary Evaluation Framework)

To obtain a statistically robust estimate of classifier generalization, all classification experiments were conducted using 10-fold stratified cross-validation, which preserves the SP/GP class balance within each fold.

For every fold:

- The dataset was split into 90% training and 10% validation.

- Fold-wise feature normalization (required only for LR) was applied.

- The model was trained on the training portion.

- Accuracy was computed on the fold’s validation portion.

For every evaluated frequency window, the following metrics were computed:

- Mean cross-validation accuracy;

- Standard deviation across folds;

- Fold-wise accuracy distribution (visualized using boxplots);

- Mean–variance scatter analysis to assess stability.

This cross-validation scheme serves as the primary and most reliable evaluation method, replacing reliance on a single split and enabling variance-aware interpretation of classifier performance.

2.5.5. Complementary Hold-Out Evaluation (Sanity Check Only)

A stratified 75/25 hold-out split was performed as an initial consistency check before establishing the full cross-validation pipeline.

This evaluation was used only to verify that both classifiers behave as expected on an unseen subset and not as the primary metric reported in the Results section.

Final model performance reported in this paper is based exclusively on the 10-fold cross-validation results detailed in Section 3.

2.5.6. Model Interpretability and Frequency Importance

To enhance interpretability, particularly for operational remote-sensing settings, the Random Forest classifier was analyzed to identify the most influential frequency components.

Feature importance values were extracted from the trained RF model and aggregated across cross-validation folds.

These analyses reveal:

- Which frequency bands (e.g., 250–330 kHz) contribute most strongly to sediment discrimination;

- How important distributions are in relation to known physical characteristics of SP and GP sediments;

- The role of high-frequency components in amplifying differences arising from scattering, porosity, and micro-geometry.

The importance profiles also complement the spectral observations in Section 3 by linking physical acoustic behavior to classifier decision mechanisms.

While these essential patterns provide meaningful insight into model behavior, they represent statistical associations rather than direct physical causation and should therefore be interpreted with appropriate caution.

2.5.7. Summary of Methodological Improvements

The revisions introduced in this section enhance the methodological clarity and robustness of the proposed framework.

By distinguishing between normalization stages, applying rigorous fold-wise preprocessing, and establishing a comprehensive cross-validation pipeline, the classification results now reflect a statistically reliable, fully reproducible evaluation protocol.

3. Results

This section presents the classification results obtained from applying machine learning algorithms to frequency-dependent acoustic reflection spectra of seafloor sediments. The analysis progresses from the visualization of spectral characteristics that distinguish the two sediment types to a quantitative evaluation of classification performance using Logistic Regression and Random Forest models.

3.1. Spectral Signature Analysis

3.1.1. Comparative Spectral Characteristics

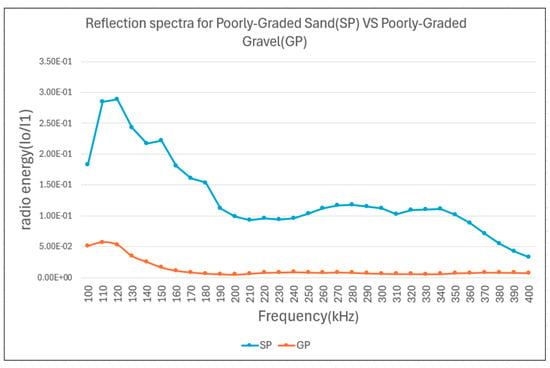

The physics-corrected reflection spectra reveal distinct acoustic signatures between the two sediment types. Figure 10 provides a direct comparison between SP and GP sediments, overlaying their spectral responses across the 100–400 kHz frequency range.

Figure 10.

Reflection spectra for poorly graded gravel (GP) and sand (SP) across 100–400 kHz. The observed frequency-dependent differences represent unique acoustic fingerprints shaped by sediment properties. These spectral features form the basis for physics-guided feature engineering in the machine learning classification pipeline. The x-axis represents the measured frequency range, while the y-axis shows the ratio of reflected (I0) to incident (I1) acoustic energy.

The non-normalized comparison shows systematic differences in reflection magnitude and frequency response between the materials. SP exhibits higher reflectance values across most frequency bands, while GP shows lower reflection coefficients with frequency-dependent variations.

3.1.2. Normalized Spectral Analysis

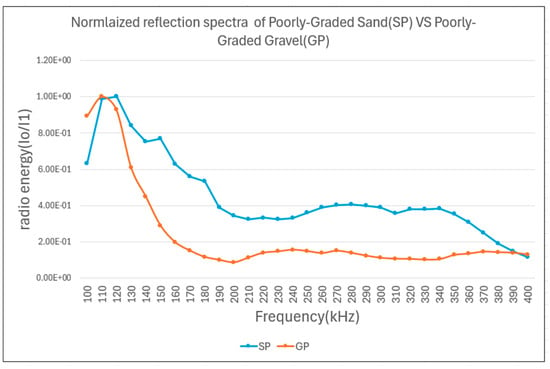

Figure 11 presents the normalized comparison of SP and GP reflection spectra, illustrating the relative spectral patterns that are independent of absolute magnitude variations.

Figure 11.

Normalized reflection spectra for poorly graded gravel (GP) and sand (SP). The normalization process suppresses magnitude-related variability, emphasizing the intrinsic spectral shape differences between sediment types. These normalized features contribute to the robustness of the machine learning model by improving generalization across varying acoustic acquisition conditions. The x-axis represents frequency (kHz), while the y-axis denotes the ratio of reflected (I0) to incident (I1) energy.

The normalized analysis reveals frequency-dependent shape differences between sediment types, particularly in the higher-frequency range (300–400 kHz), where the materials exhibit distinct acoustic behavior.

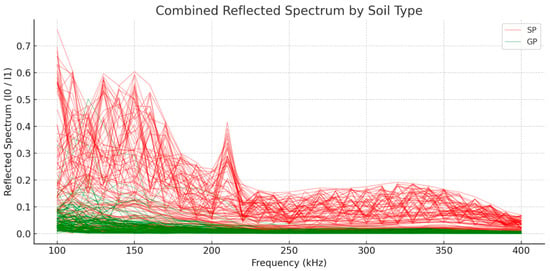

3.1.3. Complete Dataset Overview

Figure 12 presents all 200 individual sample spectra (100 SP in red and 100 GP in green), illustrating the separation between sediment classes and the variability within each group.

Figure 12.

Combined reflected spectrum (I0/I1) of 200 soil samples (100 SP in red, 100 GP in green) across the 100–400 kHz range. The plot illustrates consistent spectral separation between poorly graded sand (SP) and gravel (GP), with SP exhibiting higher and more variable reflectance across frequencies. These spectral patterns form the basis for constructing discriminative features in physics-guided machine learning models, enabling robust classification based on multi-frequency acoustic signatures. The x-axis represents frequency (kHz), and the y-axis shows the reflected energy ratio.

The spectral clusters exhibit separable groupings with overlapping regions, which represent the classification challenge for machine learning algorithms.

3.2. Classification Performance Comparison

This section evaluates the ability of machine-learning models to discriminate between SP and GP sediments using frequency-dependent reflection spectra. The analysis includes:

- Classification accuracy across sliding frequency windows.

- Model-stability assessment using 10-fold stratified cross-validation.

- A detailed comparison between Logistic Regression (LR) and Random Forest (RF).

- Visualization of fold-wise performance, variance, and mean–variance trade-offs.

3.2.1. Cross-Validation Framework and Evaluation Modes

All classification experiments were conducted using a 10-fold stratified cross-validation scheme, ensuring that both sediment classes were proportionally represented within each fold.

Two evaluation modes were used:

- Full-spectrum classification using all 31 frequency components (100–400 kHz).

- Sliding 5-frequency windows with 10 kHz increments across the spectrum, enabling frequency-band-specific performance assessment.

For Logistic Regression, fold-wise z-score normalization was applied to ensure numerical stability. Random Forest was trained directly on the physical spectral ratios (I0/I1), which share a consistent physical scale.

The following subsections present the results for each classifier.

3.2.2. Logistic Regression: Cross-Validation Results

Logistic Regression (LR) serves as a linear baseline classifier.

Table 3 reports the LR accuracy across all frequency windows.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Accuracy Across Frequency Ranges.

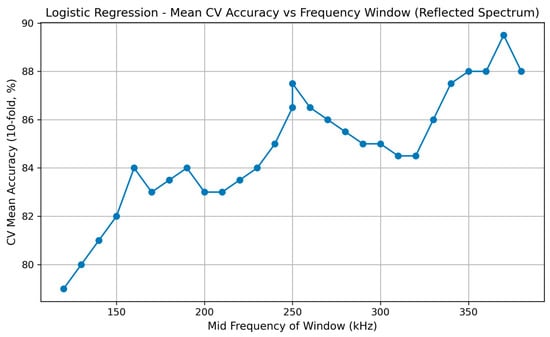

Four complementary visualizations summarize the performance of Logistic Regression across the acoustic spectrum:

1. Mean Accuracy Across Frequency Windows:

Figure 13 shows the mean 10-fold cross-validation accuracy as a function of the mid-frequency of each sliding window. Logistic Regression exhibits moderate performance across the spectrum, with the highest accuracies occurring in the 300–390 kHz range.

Figure 13.

Mean 10-fold cross-validation accuracy for Logistic Regression across sliding 5-frequency windows. The x-axis represents the mid-frequency of each window; the y-axis reports the mean accuracy.

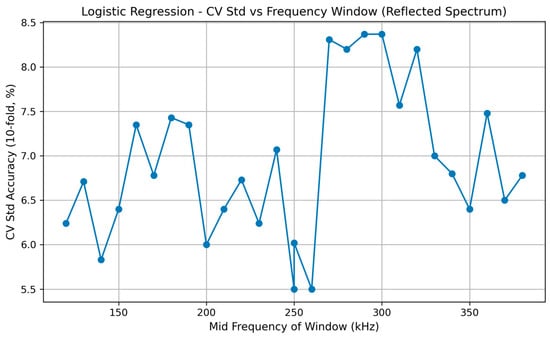

2. Standard Deviation Across Frequency Windows:

Figure 14 depicts the standard deviation of the cross-validation accuracy for each window. Lower variance indicates greater model stability. Logistic Regression demonstrates moderate variability, with reduced variance in the 240–280 kHz range.

Figure 14.

Standard deviation of 10-fold CV accuracy for Logistic Regression across all frequency windows.

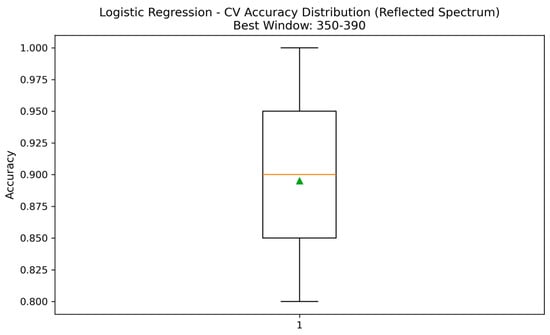

3. Accuracy distribution for the best-performing window:

Figure 15 presents a box plot of 10 accuracy folds for the strongest LR window. This visualization highlights the distribution, median, and fold-level variability.

Figure 15.

Boxplot of fold-wise accuracies for Logistic Regression in its best-performing frequency window.

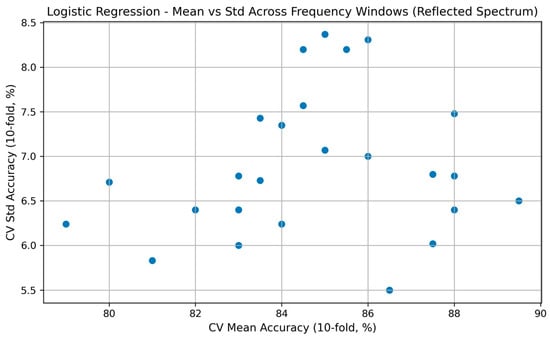

4. Mean–variance relationship.

Figure 16 shows the relationship between mean accuracy and standard deviation across all windows. This visualization helps identify windows that balance high accuracy with high stability.

Figure 16.

Scatter plot showing the mean–variance relationship across all Logistic Regression windows.

3.2.3. Random Forest: Cross-Validation Results

Random Forest (RF) serves as the primary nonlinear classifier in this study.

Its ensemble-based structure enables the capture of complex, frequency-dependent patterns that may not be linearly separable.

Table 4 reports RF performance across all sliding 5-frequency windows, showing consistently strong accuracy with several windows reaching 90%.

Table 4.

Random Forest Accuracy Across Frequency Ranges.

Across most frequency windows, Random Forest achieved higher mean cross-validated accuracies compared to Logistic Regression. These results are presented here in a purely descriptive manner, while their interpretation is deferred to Section 4. Four complementary visualizations summarize the cross-validation behavior of the Random Forest classifier across the acoustic spectrum:

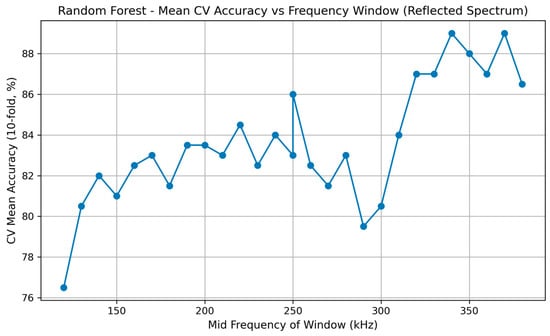

(1) Mean Accuracy Across Frequency Windows:

To visualize how RF performance varies across the acoustic spectrum, Figure 17 presents the Mean 10-fold cross-validation accuracy for each sliding window.

Figure 17.

Mean 10-fold cross-validation accuracy for Random Forest across sliding 5-frequency windows. The x-axis shows the mid-frequency of each window, and the y-axis shows the mean accuracy. RF consistently outperforms Logistic Regression, with multiple windows reaching 90%.

Compared to Logistic Regression, RF demonstrates higher overall performance and a clearer concentration of high-accuracy regions.

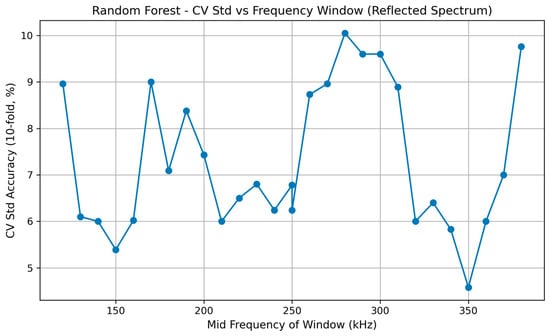

(2) Standard Deviation Across Frequency Windows:

Figure 18 illustrates the fold-wise variability of RF accuracy across the spectrum. A lower standard deviation reflects a more stable classifier. RF demonstrates moderate variance, with relatively stable behavior in high-performance frequency bands.

Figure 18.

Standard deviation of 10-fold cross-validation accuracy for Random Forest across all frequency windows, showing moderate variability and improved stability in the best-performing bands.

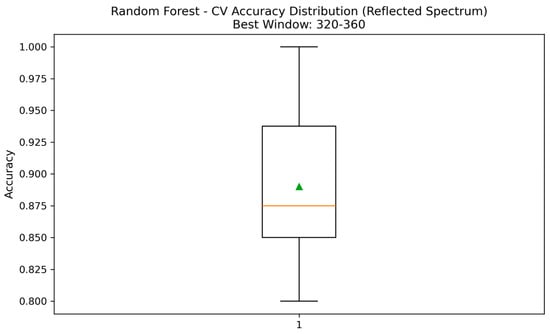

(3) Accuracy distribution for the best-performing window:

To analyze fold-wise variability within the strongest-performing RF window, Figure 19 presents a boxplot showing the distribution, median, and range of accuracies across the ten folds.

Figure 19.

Boxplot of fold-wise accuracies for Random Forest in its best-performing frequency window (180–220 kHz).

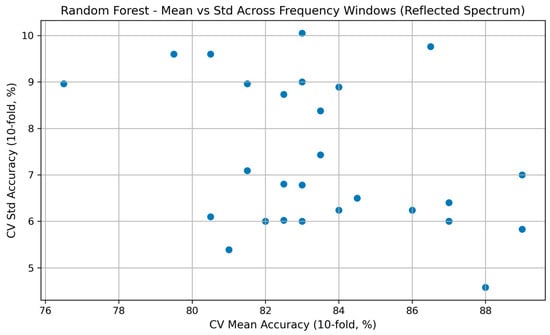

(4) Mean–variance relationship.

The joint relationship between mean accuracy and variability is shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Scatter plot showing the mean–variance relationship for Random Forest across all sliding windows. Windows in the upper-left quadrant correspond to optimal performance (high accuracy, low variance).

3.2.4. Full-Spectrum Classification Using 10-Fold Cross-Validation

To complement the sliding-window analysis presented earlier, both classifiers were evaluated using a full-spectrum 10-fold stratified cross-validation procedure. In this analysis, all 31 frequency components (100–400 kHz) were used simultaneously, allowing a direct comparison of the overall predictive capabilities of each model.

(1) Logistic Regression (LR): Full-Spectrum CV Results:

Logistic Regression displayed stable performance, with fold-wise accuracies ranging from 80% to 96%.

The mean 10-fold accuracy was 86.8%, with a standard deviation of 5.9%, indicating moderate variability.

Table 5 summarizes the total number of correct and incorrect predictions made by Logistic Regression across all 10 cross-validation folds. Rows correspond to true labels, and columns to predicted labels, allowing assessment of per-class behavior.

Table 5.

Cumulative Confusion Matrix for Logistic Regression (10-fold CV).

Classification Report (LR):

- SP (0): precision = 0.91, recall = 0.80, F1 = 0.85

- GP (1): precision = 0.82, recall = 0.92, F1 = 0.87

- Overall accuracy: 0.87

(2) Random Forest (RF): Full-Spectrum CV Results

Random Forest achieved higher performance than LR across all metrics.

Fold-wise accuracies ranged from 82% to 100%, with a mean 10-fold accuracy of 89.2% and a standard deviation of 5.1%, reflecting both higher precision and improved stability.

Table 6 presents the aggregated confusion matrix for the Random Forest classifier across all 10 cross-validation folds. It provides a detailed view of how well the model distinguishes between SP and GP samples over all validation partitions.

Table 6.

Cumulative Confusion Matrix for Random Forest (10-fold CV).

Classification Report (RF):

- SP (0): precision = 0.94, recall = 0.88, F1 = 0.91

- GP (1): precision = 0.89, recall = 0.94, F1 = 0.92

- Overall accuracy: 0.89

Although Random Forests enable out-of-bag (OOB) error estimation, OOB was not used in this study because the sliding-window approach (28 overlapping feature subsets) breaks the bootstrap independence assumption required for reliable OOB evaluation. Instead, uncertainty was quantified using 10-fold stratified cross-validation, cumulative confusion matrices, and 95% confidence intervals for the full-spectrum accuracy.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spectral Discrimination Mechanisms

The spectral analysis reveals significant acoustic differences between poorly graded sand (SP) and poorly graded gravel (GP), enabling reliable automated classification. The higher reflection coefficients observed for SP in our experimental conditions across most frequency bands stem from fundamental differences in acoustic impedance contrasts at the sediment–water interface. The finer, more uniform grain structure of SP creates a more coherent reflecting surface compared to the heterogeneous, coarser GP material.

The frequency-dependent variations observed in both sediment types reflect the complex interplay between particle size distribution, porosity, and acoustic wavelength. For SP sediments, the relatively uniform particle sizes (D50 = 0.40 mm) create consistent scattering patterns across the tested frequency range. In contrast, GP sediments with larger particle sizes (D50 = 5.4 mm) and greater size variability exhibit more complex frequency-dependent responses due to varying scattering regimes within the measured bandwidth.

The normalized spectral analysis (Figure 10) revealed shape differences independent of magnitude variations, indicating that both absolute reflection levels and spectral patterns contain discriminative information. This dual-signature approach provides robust classification features that remain stable across varying environmental conditions, thereby addressing a key limitation of traditional intensity-only methods.

Importantly, the discriminative signal captured by the classifier does not arise from single dominant spectral peaks but from subtle and distributed variations across frequency bands. These nuances are embedded in the energy ratio computations that form the corrected reflection spectrum, which serves as the core feature space. While human interpretation may struggle to detect consistent separability in such complex multi-frequency signals, the Random Forest algorithm excels at identifying and leveraging nonlinear feature combinations across many dimensions. This is achieved by randomly constructing multiple decision trees, each trained on distinct feature subsets and data. In doing so, the model can uncover complex decision boundaries driven by subtle patterns in spectral fingerprints that may not be explicitly interpretable but remain statistically robust. Thus, the RF model functions not only as a classifier but also as a tool for detecting hidden structures in acoustic data where human reasoning reaches its limits.

4.2. Machine Learning Performance Analysis

4.2.1. Comparison Between Classifiers

The results show that Random Forest (RF) achieves slightly higher accuracy and greater stability than Logistic Regression (LR) across both full-spectrum analysis and several informative frequency windows. Although the performance gap is moderate, the improvement is meaningful given the complexity of the acoustic signatures and the subtlety of the spectral differences between SP and GP.

RF benefits from nonlinear decision boundaries that can combine weak but complementary spectral cues across frequencies. LR performs consistently and captures the dominant linear trends but cannot fully exploit the nonlinear interactions embedded in the spectral data. This explains the narrow yet consistent advantage of RF.

Importantly, the modest gap also reinforces a central insight of this study:

The discriminative strength primarily stems from physics-guided spectral feature construction, rather than from reliance on complex model architectures.

Within small-sample, tabular data regimes such as this, tree-based models tend to offer the best balance between accuracy, robustness, and interpretability.

4.2.2. Informative Frequency Bands

Analysis of sliding 5-frequency windows highlights several frequency regions, most notably around 180–220 kHz and 310–370 kHz, where classification performance peaks. These bands appear to coincide with acoustic wavelengths that interact sensitively with the textural attributes of the tested sediments. While the physical interpretation is not definitive, the empirical stability of these high-performing bands suggests that these regions may be promising candidates for targeted sonar-based classification systems.

From a practical standpoint, identifying such informative frequency clusters enables more efficient system design, supporting both focused high-resolution surveys and bandwidth-constrained acquisition modes.

4.3. Influence of Physics-Guided Feature Engineering

The attenuation-corrected spectral ratio , forms the backbone of the classification framework. By separating sediment-dependent reflection from propagation-dependent energy loss, the corrected spectrum provides a physically meaningful representation that enhances cross-condition comparability.

In the controlled freshwater tank used here, the practical impact of the correction on classification accuracy is modest, consistent with the short propagation range and minimal water-column variability. However, the conceptual importance is substantial. In real marine environments, attenuation varies with salinity, temperature, suspended particulates, depth, and other oceanographic factors. Physically grounded correction, therefore, provides a crucial foundation for future field-scale generalization.

This study demonstrates that incorporating physical insight into the preprocessing stage not only improves interpretability but also ensures that machine learning operates on features that represent the underlying sediment physics rather than confounding environmental effects.

4.4. Interpretability Through Frequency Importance

Permutation-based feature importance shows that the frequency bands with the highest contribution to RF classification decisions are the same bands that exhibit the strongest empirical separation between SP and GP in our spectral analysis.

This alignment between model-driven importance and physically observable patterns increases confidence that the classifier relies on meaningful acoustic mechanisms rather than on statistical artifacts.

In addition, using permutation importance avoids the known biases of impurity-based importance (MDI), which tends to overemphasize correlated or low-variance feature properties common in spectral data.

Because permutation importance measures accuracy loss after shuffling each frequency independently, it provides a more reliable and interpretable link between the model’s decisions and underlying acoustic behavior.

4.5. Data Structure, Independence, and Transparency

All 6200 acoustic waveforms used in this study were physically collected in the laboratory, with no synthetic augmentation or replication. The 200 final samples represent independent spatial measurements, each derived from raw recorded signals. This fully empirical dataset ensures that all conclusions reflect actual acoustic behavior rather than artifacts introduced by artificial data expansion.

4.6. Environmental and Operational Considerations

While the controlled environment used here allows for isolation of sediment-specific effects, natural marine conditions introduce additional complexity. Variability in seafloor roughness, layering, biological activity, suspended sediments, thermohaline structure, and multi-path reflections can all modify spectral responses.

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

This study represents a focused feasibility demonstration. Although the laboratory results are encouraging, the controlled freshwater environment does not allow a complete assessment of the advantages of the spectral-ratio features (I0/I1) over raw intensity (Iᵢ).

In the tank, water-column variability is minimal, and therefore, the benefit of attenuation-corrected spectral features cannot be meaningfully quantified.

Operational deployment will require evaluation under real oceanographic conditions—where salinity, temperature, depth, grazing angle, multipath, and boundary roughness strongly affect the received signal. Only in such environments can the spectral-based method be rigorously compared against intensity-only approaches and its practical value fully assessed.

Accordingly, several developments are needed before operational use:

- Broader sediment coverage, including cohesive and mixed materials.

- Field-scale validation under varying ocean conditions.

- Integration into multibeam/broadband sonar or AUV platforms.

- Controlled grain-size experiments to test the resonance-like hypothesis.

- Larger datasets enabling evaluation of additional ML models.

- Angle-dependent and multi-depth in sonification experiments.

These steps will bridge the gap between laboratory feasibility and real-world applicability, ensuring that the spectral-based approach is evaluated under conditions where its advantages can emerge.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that frequency-dependent reflection spectra provide a physically meaningful and discriminative basis for classifying poorly graded marine sediments. By integrating an attenuation-corrected spectral representation with machine-learning classifiers, the method successfully distinguishes between SP and GP under controlled laboratory conditions using entirely physical measurements.

Random Forest offers a modest but consistent improvement over Logistic Regression, particularly within specific frequency windows that exhibit stable, sediment-dependent spectral patterns. The effectiveness of these physics-guided features highlights the importance of combining domain knowledge with data-driven methods.

The findings establish a foundation for extending the approach to real-world marine environments. Future work will focus on field-scale acoustic surveys, expanded sediment classes, and integration with autonomous platforms to evaluate the method’s robustness under realistic operational variability. This progression represents a path toward scalable, interpretable, and environmentally sustainable seabed classification.

This direction aligns with recent trends in geosciences, where machine learning models have been successfully applied to complex environmental monitoring tasks such as soil contamination, coastal erosion, and marine pollution, underscoring the potential of scalable AI frameworks in operational field settings [55].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and V.F.; methodology, M.G. and V.F.; software, M.G.; validation, V.F.; formal analysis, M.G. and V.F.; investigation, M.G. and V.F.; resources, V.F.; data curation, V.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and V.F.; writing—review and editing, M.G. and V.F.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, V.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M.G. is highly thankful to SCE for the Master’s fellowship. V.F. acknowledges support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie RISE project EffectFact, grant agreement No. 101008140. Both authors express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Uri Kushnir for his insightful suggestions, which significantly improved the quality of the research and the paper, and to Mr. Gennady Boronin for his dedicated and invaluable assistance in conducting the laboratory measurements.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Shtienberg, G.; Dix, J.; Waldmann, N.; Makovsky, Y.; Golan, A.; Sivan, D. Late-Pleistocene evolution of the continental shelf of central Israel, a case study from Hadera. Geomorphology 2016, 261, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergent, G.; Monnier, B.; Clabaut, P.; Gascon, G.; Pergent-Martini, C.; Valette-Sansevin, A. Innovative method for optimizing Side-Scan Sonar mapping: The blind band unveiled. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 194, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswarva, K.; Butters, A.; Fox, C.J.; Howe, J.A.; Narayanaswamy, B. Improving marine habitat mapping using high-resolution acoustic data, a predictive habitat map for the Firth of Lorn, Scotland. Cont. Shelf Res. 2018, 168, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaijel, R.; Kanari, M.; Glover, J.B.; Rissolo, D.; Beddows, P.A.; Ben-Avraham, Z.; Goodman-Tchernov, B.N. Shallow geophysical exploration at the ancient maritime Maya site of Vista Alegre, Yucatan Mexico. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 19, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innangi, S.; Tonielli, R.; Romagnoli, C.; Budillon, F.; Di Martino, G.; Innangi, M.; Laterza, R.; Le Bas, T.; Iacono, C.L. Seabed mapping in the Pelagie Islands Marine Protected Area (Sicily Channel, southern Mediterranean) using Remote Sensing Object Based Image Analysis 2 (RSOBIA). Mar. Geophys. Res. 2019, 40, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, I.; Stumpf, R.P. Retrieval of nearshore bathymetry from Sentinel-2A and 2B satellites in South Florida coastal waters. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 226, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, S.E.; Fratantonio, F.D.; Hart, P.E.; Foster, D.S.; O’Brien, T.F.; Labak, S. Measurement of Sounds Emitted by Certain High-Resolution Geophysical Survey Systems. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 44, 796–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayber, Z.; Meilijson, A.; Ben-Avraham, Z.; Makovsky, Y. Methane hydrate stability and potential resource in the Levant Basin, southeastern Mediterranean Sea. Geosciences 2019, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Cui, W.; Chen, C. Review of underwater sensing technologies and applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z. Comparative study on seismic response of pile group foundation in coral sand and Fujian sand. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chang, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Q. Seismic-Geological Integrated Study on Sedimentary Evolution and Peat Accumulation Regularity of the Shanxi Formation in Xinjing Mining Area, Qinshui Basin. Energies 2022, 15, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modenesi, M.C.; Santamarina, J.C. Hydrothermal metalliferous sediments in Red Sea deeps: Formation, characterization and properties. Eng. Geol. 2022, 305, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, L.; Baussard, A.; Le Chenadec, G.; Quidu, I. Seafloor characterization for ATR applications using the monogenic signal and the intrinsic dimensionality. In Proceedings of the OCEANS Conference, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divinsky, B.V.; Kosyan, R.D. Spectral structure of surface waves and its influence on sediment dynamics. Oceanologia 2019, 61, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.E.; Calder, B.R. Geocoder: An Efficient Backscatter Map Constructor; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2005; Available online: https://scholars.unh.edu/ccom/339/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Tamsett, D. Sea-Bed Characterization and Classification from the Power Spectra of Side-Scan Sonar Data. Mar. Geophys. Res. 1993, 15, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizos, E.; Snellen, M.; Simons, D.; Siemes, K.; Greinert, J. Multi-angle backscatter classification and sub-bottom profiling for improved seafloor characterization. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2018, 39, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Siwabessy, J.; Cheng, H.; Nichol, S. Using Multibeam Backscatter Data to Investigate Sediment-Acoustic Relationships. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2018, 123, 4649–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, L.; Smith, P.J.P.; Bates, C.R. Wavelet analysis of bathymetric sidescan sonar data for the classification of seafloor sediments in Hopvågen Bay-Norway. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2002, 23, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.; Mayer, L. Remote estimation of surficial seafloor properties through the application of Angular Range Analysis to multibeam sonar data. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2007, 28, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, U.; Frid, V. Spectral Acoustic Fingerprints of Sand and Sandstone Sea Bottoms. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.T.; Van Holliday, D.; Kloser, R.; Reid, D.G.; Simard, Y. Acoustic seabed classification: Current practice and future directions. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2008, 65, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fezzani, R.; Berger, L. Analysis of calibrated seafloor backscatter for habitat classification methodology and case study of 158 spots in the Bay of Biscay and Celtic Sea. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2018, 39, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, Y.; Naithani, S.; Anu, R. Seafloor sediment classification from single beam echo sounder data using LVQ network. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2007, 28, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Komen, D.F.; Neilsen, T.B.; Knobles, D.P.; Badiey, M. A feedforward neural network for source range and ocean seabed classification using time-domain features. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Ultrasonics, 2019; ASA: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 38, p. 070003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Petillot, Y.; Bell, J. An automatic approach to the detection and extraction of mine features in sidescan sonar. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2003, 28, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuman, M.; Berndt, C.; Jacobs, C.; Best, A. Seabed characterization through a range of high-resolution acoustic systems—A case study offshore Oman. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2006, 27, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, F.; Knauer, C.; Jans, W.; Ebert, A. Side Scan Sonar Image Resolution and Automatic Object Detection, Classification and Identification. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2009—Europe Conference, Bremen, Germany, 11–14 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, L.; Brown, C.; Calder, B.; Mayer, L.; Rzhanov, Y. Angular range analysis of acoustic themes from Stanton Banks Ireland: A link between visual interpretation and multibeam echosounder angular signatures. Appl. Acoust. 2009, 70, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.M. Integrated method for the detection and location of underwater pipelines. Appl. Acoust. 2008, 69, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nait-Chabane, A.; Zerr, B.; Le Chenadec, G. Sidescan sonar imagery segmentation with a combination of texture and spectral analysis. In Proceedings of the OCEANS-Bergen Conference, Bergen, Norway, 10–14 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir, U.; Frid, V. Spectrum-based logistic regression modeling for the sea bottom soil categorization. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.J.; Parnum, I. Acoustic seabed segmentation from direct statistical clustering of entire multibeam sonar backscatter curves. Cont. Shelf Res. 2011, 31, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Ai, B.; Luo, Y.; Ma, D. Deep learning model for seabed sediment classification based on fuzzy ranking feature optimization. Mar. Geol. 2021, 432, 106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, C.; Villar, S.; Michalopoulou, Z.-H. Seabed classification using physics-based modeling and machine learning. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 148, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaida, T.C.; Mohammadloo, T.H.; Snellen, M.; Simons, D.G. Mapping the seabed and shallow subsurface with multi-frequency multibeam echosounders. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Cui, X.; Zhang, K.; Ai, B.; Shi, B.; Yang, F. DNN-based seabed classification using differently weighted MBES multifeatures. Mar. Geol. 2021, 438, 106519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Kodagali, V.; Baracho, J. Sea-floor classification using multibeam echo-sounding angular backscatter data: A real-time approach employing hybrid neural network architecture. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2003, 28, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, G.; Scornet, E. A random forest guided tour. Test 2016, 25, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuer, R.; Poggi, J.M.; Tuleau-Malot, C. Variable selection using random forests. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31, 2225–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, P.; Ernst, D.; Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 2006, 63, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scornet, E.; Biau, G.; Vert, J.P. Consistency of random forests. Ann. Stat. 2015, 43, 1716–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, G.; Devroye, L.; Lugosi, G. Consistency of random forests and other averaging classifiers. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2015–2033. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C., Jr.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Lai, X.; Hu, T.; Fu, X.; Zhang, X.; Song, S. Seafloor sediment classification using small-sample multi-beam data based on convolutional neural networks. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Tao, C.; Wu, T.; von Deimling, J.S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G. Seafloor classification by fusing AUV acoustic and magnetic data: Toward complex deep-sea environments. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4203215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, K.J.; Kimes, R.V. Empirical characterization of random forest variable importance measures. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 52, 2249–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, C.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; Zeileis, A.; Hothorn, T. Bias in random forest variable importance measures: Illustrations, sources and a solution. BMC Bioinform. 2007, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehtaj, N.; Banerjee, S. Scientific machine learning for elastic and acoustic wave propagation: Neural operator and physics-guided neural network. Sensors 2025, 25, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louppe, G. Understanding Random Forests: From Theory to Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, G.E.; Mortenson, M.C.; Neilsen, T.B.; Van Komen, D.F.; Hodgkiss, W.S.; Knobles, D.P. Ensemble approach to deep learning seabed classification using multichannel ship noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 157, 2127–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.; Kushnir, U.; Frid, V. Innovative regression model for frequency-dependent acoustic source strength in the aquatic environment: Bridging scientific insight and practical applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.; Kushnir, U.; Frid, V. Frequency-dependent acoustic reflection for soil classification in a controlled aquatic environment. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binetti, M.S.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. Machine Learning in Geosciences: A Review of Complex Environmental Monitoring Applications. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).