Abstract

Accumulation-type water vapor transport (hereafter referred to as AT-WVT) and permeation-type water vapor transport (hereafter referred to as PT-WVT) represent two fundamental modes of water vapor diffusion in asphalt mixtures, exerting distinct impacts on asphalt pavement durability. In this study, the diffusion characteristics of AT-WVT and PT-WVT within three core components of asphalt pavement systems—pure asphalt binder, aggregate matrix, and asphalt mixture void structures—were investigated. The corresponding diffusion coefficients for these three materials were determined through a synergistic approach combining laboratory experiments and theoretical modeling. Three typical asphalt materials (50# asphalt, 70# asphalt, SBS-modified asphalt) and two commonly used aggregates (limestone, diabase) were used. The results show that, for all three materials, the water vapor diffusion coefficient for the AT-WVT mechanism is relatively low, whereas the coefficient for the PT-WVT mechanism is approximately four orders of magnitude greater. The tortuosity factor of moisture diffusion paths in asphalt mixtures is substantially elevated during AT-WVT (tortuosity factor > 2000), as water vapor encounters frequent obstacles caused by the complex microstructural architecture (e.g., asphalt–aggregate interfaces and closed pores). In contrast, PT-WVT exhibits a much lower tortuosity factor (12–18), enabling rapid and direct migration through interconnected channels, such as capillary voids and microcracks. Due to its higher transport efficiency, PT-WVT poses a more critical threat to pavement durability by facilitating rapid moisture intrusion and subsequent damage (e.g., stripping, fatigue cracking). This study elucidates the mechanistic differences between AT-WVT and PT-WVT in asphalt binder, aggregate matrix, and asphalt mixtures, providing a foundation for optimizing asphalt mixture design to enhance long-term durability and performance under hygrothermal loading conditions.

1. Introduction

Asphalt mixtures are commonly used in road construction, and their internal moisture migration and distribution have a critical impact on their durability, mechanical properties, and service life [1,2,3,4,5]. While water damage can be caused by many types and sources of water, damage associated with water vapor has attracted growing attention, as its diffusion coefficient is at least two orders of magnitude larger than liquid water’s seepage coefficient [1]. As such, water vapor enters asphalt mixtures faster. Furthermore, water vapor’s intermolecular forces are weaker than those of liquid water, which makes it easier for water vapor to enter asphalt mixtures.

Moisture is widely recognized as a driving factor in the deterioration of asphalt pavements, and it has a significant impact on both newly constructed and in-service asphalt pavements [6]. It degrades the adhesion between asphalt binders and aggregates [7], alters the chemical and rheological properties of asphalt, such as softening or accelerated aging [8], and ultimately induces typical defects, including stripping, fatigue cracking, and rutting. To elucidate the mechanisms of water vapor movement, existing studies have adopted a combination of experimental and numerical approaches. Some have focused on measuring core diffusion parameters, including the diffusion coefficient and the moisture retention capacity via laboratory tests [9,10,11], while others have analyzed the influence of material components, including fine aggregates [12,13] and asphalt binders [14,15], on moisture behavior. Some studies have investigated the impacts of mixtures’ void distribution and moisture diffusion on mixture performance, using void size probability distribution functions obtained via X-ray scanning [16]. Finite element models have also been developed to simulate moisture concentration distribution in asphalt mixtures [9,17], confirming that water vapor significantly impairs the mechanical properties of pavements.

Field observations further validate the critical role of water vapor in pavement damage. For example, pavements in Arizona’s deserts and Utah’s arid/semi-arid regions exhibit severe early-stage water damage [18], despite minimal liquid water infiltration, suggesting that water vapor is the primary cause. Similarly, coring analysis of water-damaged pavements at Osaka Airport [19] revealed that liquid water barely penetrates under pressure, while water vapor diffuses freely, even with an annual average relative humidity (RH) of 58%. These cases highlight the urgency of understanding water vapor diffusion mechanisms to improve pavement durability.

Water vapor diffusion in asphalt mixtures occurs in two distinct modes, which dominate different stages of the pavement lifecycle:

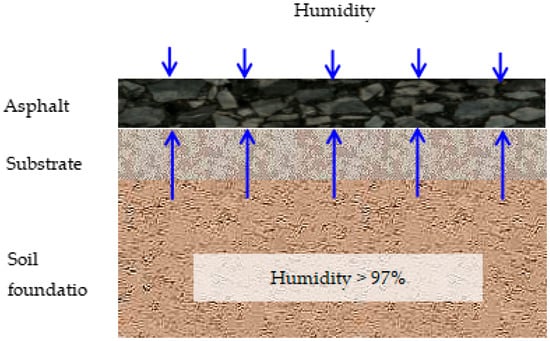

(1) Accumulation-type water vapor transport (AT-WVT): Newly paved asphalt pavements are nearly free of water molecules, as asphalt and aggregates are heated to 150~170 °C during construction. However, the overlying air contains water vapor with time- and location-dependent relative humidity, and the underlying subgrade soil maintains a relative humidity of 97~100%. This humidity level corresponds to a total suction capacitance of 2~4.5 PF [20]. Driven by this humidity gradient, water vapor continuously infiltrates and accumulates in the asphalt mixture, making AT-WVT the dominant mode for newly paved pavements [21,22], as shown in Figure 1. Two test methods are used to study AT-WVT: the mass weighing method [13,21,23], which features simple operations and intuitive data and enables direct parameter derivation via diffusion models, contributing to its wide adoption, and the thermocouple hygrometer suction measurement method [24,25], which requires drilling and may not fully reflect actual moisture behavior, limiting its applicability.

Figure 1.

Accumulating moisture diffusion on an asphalt surface.

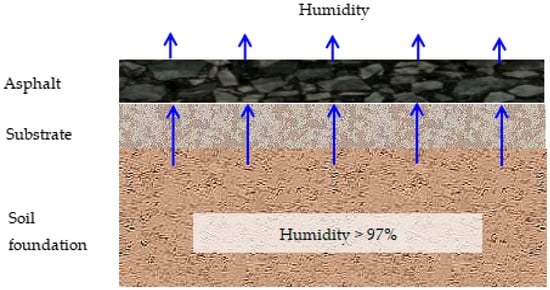

(2) Permeation-type water vapor transport (PT-WVT): With prolonged service, asphalt mixtures gradually absorb and retain moisture due to their porous and semi-permeable nature. Once moisture reaches dynamic equilibrium, PT-WVT becomes the dominant mode; the subgrade (relative humidity > 97%) serves as a continuous moisture source, and water vapor migrates upward through capillary action and interconnected pores between the subgrade and the asphalt layer, as shown in Figure 2. PT-WVT is typically evaluated using the ASTM E96/E96M standard [26], which simulates steady-state moisture permeation.

Figure 2.

Permeating moisture diffusion on an asphalt surface.

Despite advances in research, two critical limitations hinder a comprehensive understanding of water vapor diffusion and its engineering applications:

- (1)

- Isolated analysis of single diffusion modes: Most studies focus on either AT-WVT or PT-WVT in isolation. Some studies have investigated PT-WVT by focusing on moisture permeation after dynamic equilibrium in mid-to-late service stages [9,10], while others have examined moisture accumulation in newly paved pavements in AT-WVT [21,22]. This isolated approach neglects pavements’ lifecycle continuity, failing to reveal the temporal evolution relationship (AT-WVT dominance in early stages → PT-WVT dominance in late stages) and intrinsic interaction (e.g., accumulated moisture induces capillary channels to accelerate PT-WVT) between the two modes.

- (2)

- Oversimplified microstructure models: Existing diffusion models idealize asphalt mixtures as homogeneous media [9] or assume uniform spherical pores [25], ignoring actual microstructure characteristics (e.g., staggered distribution of open/closed pores, micro-gaps at asphalt–aggregate interfaces). This simplification leads to deviations between model predictions and real-world diffusion behavior, reducing the accuracy of engineering guidance.

To address these gaps, this study systematically investigates AT-WVT and PT-WVT in asphalt mixtures, with three key innovations compared to previous work:

- (1)

- Unlike isolated studies on a single diffusion mode, this study focuses on the dynamic transition process of two diffusion modes across the entire lifecycle of asphalt pavement and finds that the capillary channels gradually formed during the AT-WVT process can shorten the diffusion path of PT-WVT by about 200 times.

- (2)

- Instead of simplifying pore structures, this study calculates actual pore radii based on asphalt film thickness and links pore connectivity to diffusion efficiency, making diffusion coefficients and tortuosity factors more consistent with real asphalt mixture microstructures.

This study elucidates the fundamental differences and interaction mechanisms between AT-WVT and PT-WVT, providing a scientific basis for optimizing asphalt mixture design and mitigating moisture-induced damage. The findings are expected to improve the long-term service performance of asphalt pavements in diverse climatic conditions.

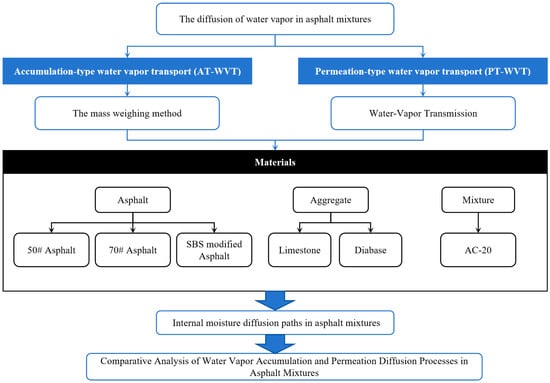

AT-WVT and PT-WVT in asphalt, aggregates, and voids are first quantified through a combination of laboratory tests and theoretical calculations. Subsequently, the internal diffusion paths of these two water vapor transport modes within asphalt mixtures are analyzed with a focus on how microstructural features regulate path tortuosity and migration resistance. Finally, the intrinsic relationship between AT-WVT and PT-WVT is explored, including their dynamic transition across the pavement lifecycle and the influence of AT-WVT-induced capillary channels on PT-WVT efficiency. The paper’s technical roadmap is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The paper’s technical roadmap.(# indicate the penetration grade identification of asphalt, In all subsequent content, any occurrence of the “#” symbol shall refer to the above-mentioned meaning, i.e., it is used to identify the penetration grade of asphalt.).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Method

2.1.1. AT-WVT Diffusion Coefficient

The water vapor diffusion coefficient is a physical parameter reflecting the diffusion rate. The moisture diffusion coefficient can directly affect the distribution of water molecules, as well as the time required to reach moisture balance in asphalt mixtures. Therefore, the water vapor diffusion coefficient is an important parameter.

During the water vapor diffusion process, water vapor continuously migrates from the outside to the inside of the sample and is adsorbed internally. This accumulation of adsorbed water vapor directly leads to a gradual increase in the sample’s overall mass over time. At this time, the moisture concentration in the sample is 0, and the moisture concentration in the air is expressed by the RH:

Here, is the partial pressure of water vapor, Pa, and is the saturated vapor pressure of water, Pa.

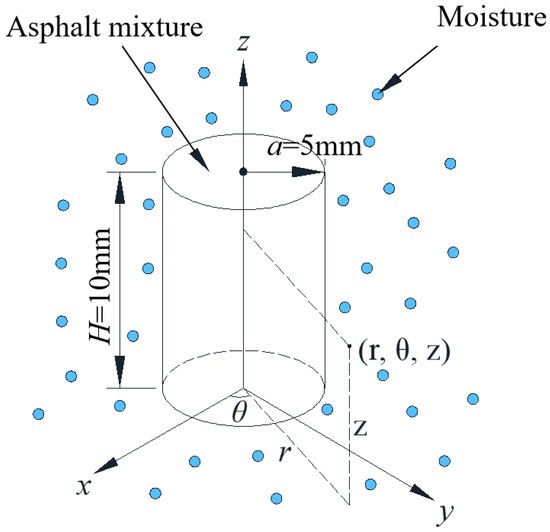

When the testing temperature is constant, vapor pressure is introduced into the environmental box to establish a constant relative humidity outside of the specimen, and the relative humidity inside of the specimen is brought to 0 through drying and curing. At this time, there is a relative difference in humidity between the inside and the outside of the sample, and the water vapor molecules continue to diffuse into the sample under the effect of this relative humidity difference, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of three-dimensional accumulated water and air movement in a cylindrical specimen.

Therefore, the concentration of water and gas molecules in the sample varies with time, which conforms with Fick’s second law:

where is the diffusion coefficient of water vapor accumulated inside of the sample, mm2/h.

By integrating t over time in Equation (2), the relationship between the sample mass increment and time can be obtained. Existing studies have determined a three-dimensional water and air motion model through derivations [23]:

Here, is the moisture mass absorbed by the specimen at time t, g; is the maximum moisture mass the specimen can absorb, g; is the radius of the specimen, mm; is the height of the asphalt mixture, mm; and is the root of the zeroth-order Bessel function. To ensure the model’s goodness of fit, the discrete model’s optimal number of terms is determined to be 36, that is, .

To study accumulation-type water vapor transport (AT-WVT) in asphalt mixtures, a Gravimetric Sorption Analyzer (GSA, Rubolab Technologies, Germering, Germany) was used. A schematic diagram of the equipment is shown in Figure 5. The GSA was equipped with a high-precision magnetic suspension balance, which enables accurate weighing of the mass of test specimens, with the balance accuracy reaching 0.1 mg; the test temperature was set to 20 °C.

Figure 5.

Photo of GSA equipment.

2.1.2. PT-WVT Diffusion Coefficient

The main principle of the test is Fick’s first law, which describes the relationship between diffusion flux and material concentration in a steady state:

Here, J is the diffusion flux, g/s·mm3; Deff is the effective diffusivity, mm2/s; and dC/dy is the concentration gradient, g/mm2. Another way to express the diffusion flux is as follows:

where A is the diffusion area, mm2, and is the mass loss rate of water in the container during the test, g/h. We calculated the rate of change in water vapor permeation with respect to time by periodically weighing the mass of the device.

Equation (6) can be obtained through simultaneous substitution of Equations (4) and (5):

Here, L is the thickness of the specimen, mm, and C1 and C2 represent the mass concentration on both sides of the specimen, g/mm3.

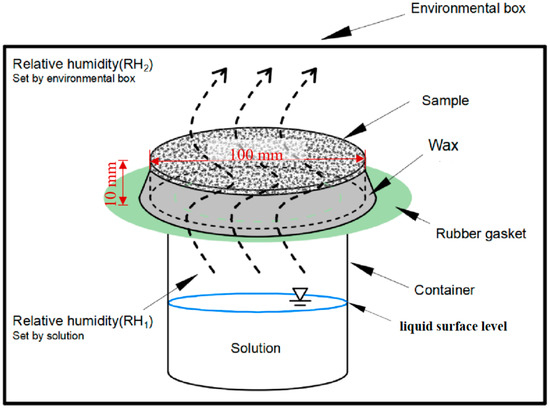

The test equipment includes an environmental box, a hygrometer, and a self-assembled permeating moisture diffusion test device. Figure 6 presents a schematic of the test device.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the permeating water vapor diffusion test device.

A cylindrical glass container with an open top was filled with distilled water to provide constant relative humidity (RH1 = 100%) inside of the container. An annular silicone sheet was affixed to cover the edge of the container to ensure close contact with the specimen. The specimen was then fixed above the container, and the gaps were sealed with wax.

The relative humidity outside of the container (RH2 = 60%) was regulated by an environmental chamber, which ensured constant temperature and humidity. The RH1 inside of the container and the RH2 outside produced the relative humidity gradient required. Driven by this humidity gradient, water vapor accumulated above the liquid surface inside of the container, penetrated the specimen, and gradually diffused into the environmental chamber.

This test device can effectively simulate the penetrating water vapor diffusion process of actual asphalt surface layers driven by the humidity gradient formed between subgrade soil and air.

The asphalt mixture and aggregate can be tested using these methods. However, asphalt cannot be directly used, as its thickness in the asphalt mixture is typically approximately 10 μm and asphalt is prone to deformation and can change the permeation area under the action of gravity.

To solve this problem, we take the aggregate particles coated with the asphalt membrane as the test object. Asphalt mixture is formed by mixing asphalt, aggregates, and other components, followed by compaction. In the compacted mixture, asphalt adheres to and wraps around the surface of aggregates, so using aggregate particles wrapped with asphalt film is highly representative of the internal structure of asphalt mixture.

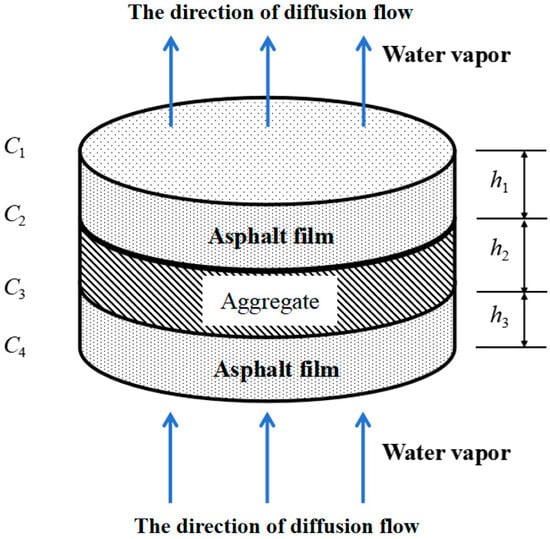

Aggregate particles coated with asphalt membrane can be conceptually divided into a three-layer material combination. As shown in Figure 7, the middle aggregate particles are completely enveloped by the upper and lower asphalt films. Water vapor can permeate from both the top and bottom sides of this composite structure. The concentration gradients C1, C2, C3, and C4 at different positions drive water vapor diffusion through the asphalt films and the aggregate. The thicknesses h1, h2, and h3 of each layer (asphalt film–aggregate–asphalt film) also impact the rate and path of water vapor diffusion, which is of great significance when studying the moisture damage mechanism of asphalt mixture.

Figure 7.

Diagram of permeating moisture diffusion of asphalt-membrane-coated aggregate.

Driven by the relative humidity difference, water vapor passes through the asphalt membrane, the aggregate, and the asphalt membrane. At this time, the diffusion flux J of any horizontal section is the same. Because the cross-sectional areas of the top and bottom of the specimen are the same as those of each layer of material, according to Fick’s first law, the effective diffusion coefficients of asphalt and aggregate are described by the following equations:

where and represent the asphalt film’s thickness, mm; is the aggregate’s thickness, mm; , , , and represent the moisture concentration, g/mm3; is the permeation moisture diffusion coefficient of asphalt, mm2/h; and is the accumulation moisture diffusion coefficient of asphalt, mm2/h.

If the sample is regarded as a whole, the effective diffusion coefficient can be expressed by Equation (9):

The effective diffusion coefficient of the entire sample () and the diffusion coefficient of the aggregate () can be obtained through testing. Meanwhile, the aggregate’s thickness can be measured. The sample’s total thickness is h1 + h2 + h3, because the total thickness of the upper and lower asphalt films can be calculated as ha. Therefore, Equation (9) can be converted into Equation (10), which can be used to calculate the permeation-type water vapor diffusion coefficient of the asphalt membrane.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Asphalt

The asphalt materials used include 50# asphalt, 70# asphalt, and SBS-modified (Styrene Butadiene Styrene triblock copolymer) asphalt. Among them, 50# and 70# asphalt are common base asphalts classified by the penetration index in China (with penetration values of approximately 50 dmm and 70 dmm, respectively), and they are widely used in road engineering. SBS-modified asphalt is a polymer-modified asphalt that can significantly improve the high and low temperature stability and water damage resistance of the mixture. These asphalts are commonly used in engineering, and their basic performance parameters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conventional properties of selected bituminous binders.

2.2.2. Aggregate

Two typical aggregates, limestone and diabase, were used. They are both commonly used in asphalt pavement engineering for expressways. Limestone was classified into 5 particle size fractions: 16–19 mm, 4.75–13.2 mm, 2.36 mm, 0.075–1.18 mm, and Pan (<0.075 mm). Diabase had a single particle size fraction of 13.2–9.5 mm. The physical performance indicators of the two aggregates are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Physical performance indicators of aggregates.

2.2.3. Mixture

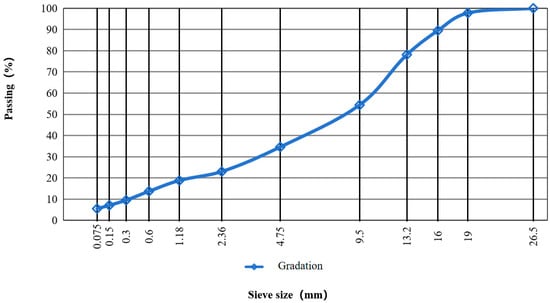

To explore the diffusion characteristics of moisture in asphalt mixtures, we used an AC-20 mixture, which is widely used in the middle surface of asphalt pavements.

All asphalt mixtures were made of the SBS-modified asphalt binder and limestone aggregates, which were identical to those used in the water vapor diffusion tests. The asphalt–aggregate mass ratios of the five mixtures were 3.5%, 4.0%, 4.3%, 4.5%, and 5.0% by aggregate weight, respectively. Notably, the optimal asphalt–aggregate mass ratio is 4.3%. The aggregate gradation of all mixture types was identical, as shown in Figure 8. The volume index test results of asphalt mixture specimens are shown in Table 3.

Figure 8.

Grading curve of asphalt mixture.

Table 3.

The volume index test results of asphalt mixture specimens.

2.3. Test Results

2.3.1. The Diffusion Coefficient of Asphalt

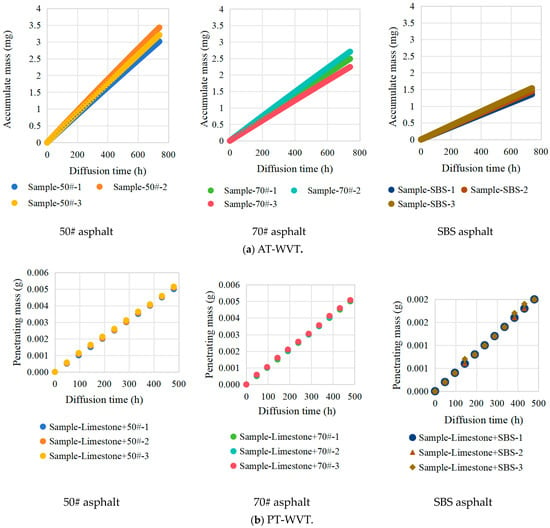

Water vapor diffusion coefficient tests were conducted on three typical asphalt materials: 50# asphalt, 70# asphalt, and SBS-modified asphalt. The temperature was set to 20 °C, and the asphalt sample was placed in a drying oven to complete the drying process. Next, it was transferred to an environmental oven with a relative humidity of 100% for testing. To ensure the reliability of the experimental results, three parallel tests were conducted for each type of asphalt. The relevant experimental data are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Experimental data for asphalt moisture diffusion.

As the diffusion time increases, the cumulative mass (Figure 9a, AT-WVT condition) and the permeating mass (Figure 9b, PT-WVT condition) of all samples exhibit a consistent upward trend. For the same samples, the data from three replicate tests show high consistency, which confirms the repeatability and stability of the experiment. Notably, discrepancies exist in the growth rates across samples.

In Figure 9a, the moisture accumulation rate of SBS-modified asphalt is slower than that of 50# asphalt and 70# asphalt.

In Figure 9b, the permeating mass growth rate of the limestone–SBS-modified asphalt is also lower than that of limestone–50# asphalt and limestone–70#, which aligns with the moisture accumulation pattern in AT-WVT conditions.

To measure the asphalt film’s thickness, limestone aggregates with a particle size > 13.2 mm were selected. The aggregates were first cleaned with distilled water and heated in a 170 °C oven for 4 h to completely evaporate internal moisture. Subsequently, they were polished into smooth, flat particles using a file. The thickness of each aggregate was measured at 5 different positions with a vernier caliper to ensure that the thickness of flat aggregates in the same sample group was essentially consistent, thereby minimizing interference from inherent aggregate thickness variations [11].

Next, 50# and 70# asphalt were heated to 160 °C, and SBS-modified asphalt was heated to 170 °C, with both maintained in a molten state. Tweezers were used to hold the pretreated flat aggregates, which were then vertically immersed in the corresponding molten asphalt and lifted vertically. Gravity facilitated the formation of a smooth, uniform asphalt film on the aggregate surface. After the samples cooled naturally to room temperature, a vernier caliper was employed to measure the total thickness of the asphalt-coated aggregates, and the asphalt films’ thickness was calculated accordingly. Table 4 presents the thicknesses of all samples.

Table 4.

The thickness of aggregate samples.

Using Equation (3), the experimental data were fitted to obtain the AT-WVT coefficient of asphalt. This was performed for all three materials, and the results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The moisture diffusion coefficients of different asphalts.

The comparative test results show that the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient of the asphalt film is about 104 times the AT-WVT. This indicates that the diffusion rate of water vapor in the asphalt film is not a constant value and that the diffusion coefficient is closely related to the type of diffusion. This is because, in the process of accumulation diffusion, water vapor first needs to gradually accumulate inside of the asphalt film to form a sufficient concentration gradient to promote diffusion. Through this process, it is also necessary to overcome the resistance inside of the asphalt film to construct or widen the diffusion channel. In contrast, permeation diffusion utilizes existing or easily formed diffusion channels, allowing water vapor to quickly pass through the asphalt film.

2.3.2. Aggregates’ Diffusion Coefficients

To investigate water vapor diffusion behavior in aggregates, two different types of aggregates (limestone and diabase) were used. Three independent parallel samples were prepared for each type of aggregate, with a particle size distribution of 9.5–13.2 mm. The testing temperature was set at 20 °C, and the relative humidity gradient was set at 60–100%. The water vapor diffusion test results of different aggregates are detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Moisture diffusion coefficients of different aggregates.

For AT-WVT, the average diffusion coefficient of limestone was 1.901 × 10−2 mm2/h, which is 10.0% higher than that of diabase (1.728 × 10−2 mm2/h). For PT-WVT, the average diffusion coefficient of limestone reached 4.053 × 102 mm2/h, a 27.2% increase compared to diabase (3.186 × 102 mm2/h).

These differences confirm that limestone consistently exhibits higher moisture diffusion efficiency than diabase, with the gap being more pronounced in PT-WVT, a trend closely linked to their distinct physical structures and mineralogical compositions.

The difference between apparent specific density (excluding surface permeable voids) and bulk specific density (including all voids, both permeable and impermeable) in Table 4 further underscores limestone’s greater open pore connectivity. For instance, in the 16–19 mm particle size fraction of limestone, the density difference is 0.02 g/cm3, indicating a larger volume of open, interconnected voids. These voids form continuous pathways for water vapor, which is particularly impactful in PT-WVT (where interconnected channels dominate diffusion). This explains why limestone’s PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is 27.2% higher than that of diabase.

Experimental and calculated results reveal a significant discrepancy between the AT-WVT and PT-WVT diffusion coefficients of aggregates; specifically, the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is approximately four orders of magnitude (104 times) higher than that of AT-WVT. This pattern is consistent with the water vapor diffusion behavior observed in asphalt films, aligning with the earlier findings in Section 2.2.1.

Moreover, compared to asphalt, aggregates exhibit stronger polarity and greater affinity for water molecule adsorption. As such, aggregates’ diffusion coefficients are significantly higher than those of asphalt. For AT-WVT, the order of magnitude of the aggregate diffusion coefficient is 10−2 mm2/h, while that of asphalt is 10−4 mm2/h, representing a two-order-of-magnitude difference (102 times). Similarly, for PT-WVT, the order of magnitude of the aggregate water vapor diffusion coefficient is 102 mm2/h, whereas that of asphalt is 100 mm2/h, which is also a two-order-of-magnitude difference (102 times).

2.3.3. The Diffusion Coefficient of Asphalt Mixtures

Using the experimental data, the coefficient orders of asphalt mixtures under different types of moisture diffusion were summarized (Table 7). These data suggest that, for the same material, the permeation-type diffusion coefficient and the accumulation-type diffusion coefficient are inconsistent, which manifests in the order of magnitude of the permeation-type coefficient, which is always higher than that of the accumulation-type coefficient. Further analysis of the effective moisture diffusion coefficients of asphalt, aggregate, and asphalt mixture shows that the permeation-type coefficient is 104 times higher than the accumulation-type coefficient.

Table 7.

Moisture diffusion coefficients of asphalt mixtures.

The water vapor diffusion coefficients of asphalt, aggregate, and asphalt mixture were investigated. Through calculation and analysis, it was found that the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is always higher than that of AT-WVT. Specifically, the PT-WVT diffusion coefficients of aggregate, asphalt, and asphalt mixture were about 104 times higher than their AT-WVT diffusion coefficients.

For asphalt pavement, AT-WVT mainly occurs in the early stages of pavement construction. At this time, the concentration of moisture molecules in the asphalt mixture is low, and the humidity difference between the asphalt mixture and the outside air (or subgrade) is large. Moisture mainly accumulates in the pavement until it reaches a certain saturation state. When the moisture in the mixture reaches this saturated state due to the difference in humidity, the moisture molecules in the mixture migrate outward. At the same time, the moisture molecules in the subgrade continue to infiltrate the interior of the mixture, forming a continuous moisture permeation movement, that is, PT-WVT. The order of magnitude of the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is usually 104 times higher than that of AT-WVT. This implies that there are significant differences between the two diffusion laws’ mechanisms.

3. Internal Moisture Diffusion Paths in Asphalt Mixtures

3.1. Water Vapor Diffusion in Pores

The moisture diffusion coefficient in asphalt voids is related to the pore radius, temperature, humidity, and pressure. Therefore, if environmental conditions are identical, the moisture diffusion coefficient in the voids of the same asphalt mixture should be identical. The key factor affecting the diffusion coefficient in pores is the pore radius. According to existing research, the pore radius can be expressed as a function of asphalt film’s thickness, as shown in Equation (11).

where t is the thickness of the asphalt film, mm.

α1, α2, and α3 represent the geometric characteristics of the aggregate particles in the asphalt mixture, calculated as follows:

where is the mean diameter of the aggregate particles, mm; is the mean diameter squared, mm2; and is the mean diameter cubed, mm3. A detailed derivation of Equation (11) is documented in [27].

When the water vapor diffusion process occurs mainly in pores, the type of water vapor diffusion inside of the asphalt mixture can be determined by analyzing the relative relationship between the pore radius and the molecular free path. Research shows that transitional diffusion occurs within pores, which can be calculated through Equation (15) [19,28]:

Here, is the diffusivity of the molecular diffusion of water vapor, 9.36 × 104 mm2/h at 20 °C [20], and is the diffusivity of the Knudsen diffusion of water vapor, estimated using Equation (16):

where is the molar mass of water, 18.0153 g/mol. With the determined values shown in Table 6, was calculated for all mixture types at a temperature of 20 °C using Equation (16).

The diffusion coefficient in the pores of asphalt mixtures can be obtained by calculating the thickness of the asphalt oil film. The asphalt film’s thickness can be calculated using the volume index and other basic properties of the mixtures. The settlement results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Average properties of asphalt mixtures.

3.2. PT-WVT Diffusion Path

Based on these results, we can draw the following conclusions. Asphalt’s PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is of an order of approximately 1 mm2/h, the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient of the aggregate is of an order of approximately 10 mm2/h, and the void’s moisture diffusion coefficient is as high as 104 mm2/h. Because water vapor tends to propagate in the medium with the largest diffusion coefficient, voids are the main channels for permeating water vapor diffusion in asphalt mixtures. Although these diffusion paths may be tortuous and complex, water and gas always choose the path with the largest diffusion coefficient and the least resistance. Therefore, moisture diffusion in asphalt mixtures has the following characteristics.

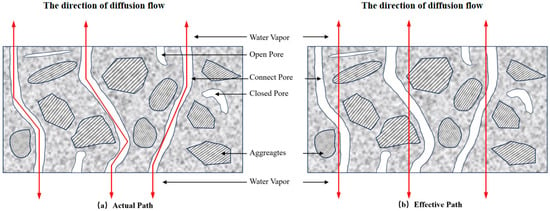

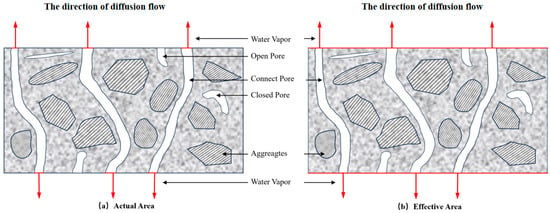

- (1)

- As shown in Figure 10a, within the asphalt mixture, the actual water vapor diffusion path is far from a simple straight line. Instead, it forms a complex curve. This complexity arises because the asphalt mixture has a heterogeneous internal structure composed of aggregates, asphalt, and various types of pores (open pores, connected pores, and closed pores). Water vapor must navigate around the aggregates, penetrate the asphalt-filled regions, and find its way through the interconnected pore networks. The presence of these different components forces the water vapor to take a tortuous route, and the path is influenced by the distribution and size of the aggregates, as well as the connectivity of the pores.

Figure 10. Water vapor diffusion paths in an asphalt mixture: actual tortuous pathways through open/connected pores vs. simplified effective path model.

Figure 10. Water vapor diffusion paths in an asphalt mixture: actual tortuous pathways through open/connected pores vs. simplified effective path model. - (2)

- The actual water vapor diffusion area is not the entire cross-sectional area of the sample. Instead, it is the void area on the cross-section, as shown in Figure 11a. The voids in the asphalt mixture, including open pores and connected pores, provide the channels for water vapor movement. Closed pores, on the other hand, do not contribute to diffusion, as they are isolated. The aggregates, which are solid and impermeable to water vapor to a large extent, and the asphalt that coats them, occupy the non-diffusion areas of the cross-section. As such, only the interconnected void spaces that are open to water vapor flow make up the actual diffusion area.

Figure 11. Comparative water vapor diffusion areas in asphalt mixture cross-section: actual pore-based area vs. simplified effective area.

Figure 11. Comparative water vapor diffusion areas in asphalt mixture cross-section: actual pore-based area vs. simplified effective area.

Accordingly, the water vapor diffusion coefficient measured in accordance with the ASTM e96/e96 m-16 Standard [26] Test method is not the real diffusion coefficient but an “effective diffusion coefficient.” In this method, the thickness of the asphalt mixtures is taken as the length of the diffusion path (as shown in Figure 10b), and the entire cross-sectional area is assumed to be the diffusion area (as shown in Figure 11b). Therefore, the effective diffusion coefficient is calculated according to the thickness and the entire cross-sectional area of the asphalt mixtures, as shown in Equation (17):

Here, is the effective diffusion coefficient of moisture in the asphalt mixture sample, mm2/h; is the effective area (the area of the entire cross-section of the specimen), mm2; is the molecular mass of water vapor diffused through the sample, g; is the length of the effective diffusion path (the thickness of the specimen), mm; and is the concentration difference between water and gas, g/mm3.

Generally, the curvature of a diffusion path can be quantified by the tortuosity factor using Equation (18):

where is the actual path length of water vapor diffusion and is the effective path length of water vapor diffusion.

Assuming that the percentage of the actual diffusion area on the cross-section of asphalt mixtures is identical to the voidage of the mixtures, the relationship between the effective and actual diffusion coefficients can be obtained according to the definition of the tortuosity factor, as shown in Equation (19):

The results are summarized in Table 7, which shows that the effective diffusion coefficient of asphalt mixtures increases with the voidage. When the voidage increases from 4.71% to 6.00%, the effective diffusion coefficient increases from 2.07 × 102 mm2/h to 3.33 × 102 mm2/h. Because the tortuosity factor reflects the length of the water vapor diffusion path inside of different asphalt mixtures and the tortuosity factors of asphalt mixtures shown in Table 9 are greater than 10, this indicates that the length of the actual path of water vapor movement inside of the asphalt mixture is over 10 times greater than the thickness of the specimen.

Table 9.

Internal diffusion structure characteristics of permeating asphalt mixtures.

3.3. AT-WVT Diffusion Path

For the same kind of asphalt mixture, when the external conditions are identical, the increment in mass per unit time remains unchanged. Therefore, the relationship between the actual and effective diffusion paths can be established according to the relationship between the accumulated moisture diffusion coefficient of the asphalt mixture and the mass increment in the specimen, as shown in Equation (20):

The tortuosity factor can be obtained through an equation transformation, as shown in Equation (21):

Using Equation (21), the tortuosity factor of asphalt mixtures with different asphalt aggregate ratios can be calculated. The results are listed in Table 10, which shows that the tortuosity factor of the five types of asphalt mixtures is greater than 2000, indicating that the actual diffusion path length is more than 2000 times longer than the effective diffusion path length.

Table 10.

Internal diffusion structure characteristics of aggregate asphalt mixtures.

4. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that porosity is the dominant factor regulating the diffusion coefficient of permeation-type water vapor transport (PT-WVT) in asphalt mixtures. PT-WVT is the primary driver of water damage in pavements during their mid-to-late service stages. When air void content increased from 4.71% (binder content = 5.0%) to 6.42% (binder content = 4.3%), the effective PT-WVT diffusion coefficient rose from 2.07 × 102 mm2/h to 2.60 × 102 mm2/h (a 25.6% increase), while the tortuosity factor only slightly increased from 15.96 to 18.02, an increment offset by the significant expansion of interconnected pore volume.

This correlation stems from the microstructural changes in asphalt mixtures. Greater air void content not only increases total pore volume but also enhances the connectivity of macropores (pore diameter > 7 × 10−3 mm, Table 6). For instance, when air void content increased from 4.71% to 6.00%, the average pore radius increased from 6.295 × 10−3 mm to 6.953 × 10−3 mm (Table 6), facilitating the formation of more interconnected capillary channels. These channels shorten water vapor’s actual diffusion path and reduce migration resistance, resulting in a substantial increase in diffusion efficiency.

The orders of magnitude of moisture diffusion coefficients for different types of asphalt mixture materials are summarized in Table 11. The same material exhibits different diffusion coefficients for different diffusion types, and the order of magnitude of the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is always greater than that of AT-WVT. For the effective moisture diffusion coefficients of asphalt, aggregate, and asphalt mixture, the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is always 104 times greater than that of AT-WVT. The moisture diffusion coefficient in the voids is related to the pore radius, temperature, humidity, and pressure; as such, when the environmental conditions are identical, the moisture diffusion coefficient in the voids of the same asphalt mixture should be the same.

Table 11.

Order of magnitude of the effective water vapor diffusion coefficient of different types of materials (mm2/h).

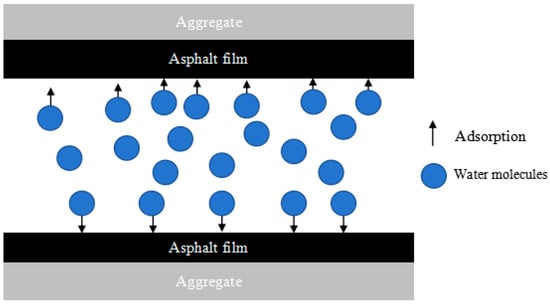

For asphalt pavements, AT-WVT and PT-WVT water vapor diffusion coexist. However, for newly paved asphalt mixtures, their internal relative humidity is almost 0, and water vapor molecules continue to diffuse from the air and subgrade soil into the asphalt mixtures. Thus, at this time, AT-WVT is the primary form of diffusion.

Because the diffusion coefficient of water vapor in the voids is the greatest, water vapor molecules tend to diffuse inside of the voids. Some water molecules move in the gaps, and some water vapor molecules are adsorbed into asphalt molecules under the action of polar components, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

AT-WVT in asphalt mixture.

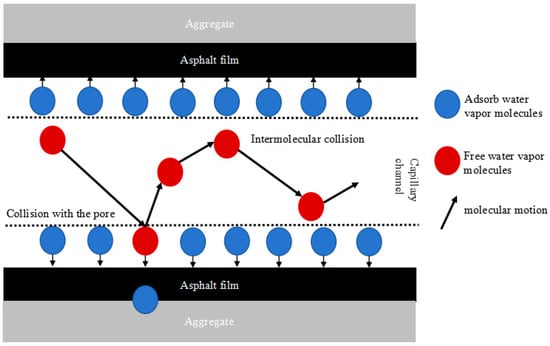

When the moisture molecules inside of the asphalt mixture are saturated, they penetrate the asphalt’s film and continue to diffuse towards the interface between asphalt and the aggregate, resulting in the peeling off of asphalt from the aggregate surface. At the same time, the water vapor molecules adsorbed on the surface of the asphalt membrane form capillary tubes, and the water supply gas passes quickly, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

PT-WVT in asphalt mixture.

After the capillary tubes are formed, free water and gas molecules in the pore channels continue to diffuse under the effects of the relative humidity difference, molecular collisions, and collisions between molecules and pore walls. Finally, they penetrate the asphalt mixture and diffuse into the air. At this time, PT-WVT is the main form of water vapor diffusion.

There are two types of water vapor molecules in asphalt mixtures: the water vapor molecules adsorbed on the surface of the asphalt membrane (adsorbed water vapor molecules) and the water vapor molecules that diffuse into the pores (free water vapor molecules). The mass of free water vapor molecules passing through the asphalt mixture is measured using a PT-WVT diffusion test, while the mass of adsorbed water vapor molecules and free water vapor molecules that persist in the mixture are measured using an AT-WVT diffusion test.

The water vapor molecules adsorbed on the asphalt membrane gradually diffuse to the interface between the asphalt membrane and the aggregate, while the free water vapor molecules continuously provide water vapor molecules to the internal space of the asphalt mixture. Some of these molecules pass through the asphalt mixture, while others fill the spaces of the water vapor molecules that are adsorbed onto the asphalt membrane. Due to the formation of capillary pipes, the diffusion speed of water vapor in the asphalt mixture accelerates, and, finally, the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is much greater than the AT-WVT diffusion coefficient.

Due to the formation of capillary pipes, water vapor tends to diffuse into the capillaries, which greatly shortens the length of the water vapor diffusion path. The results show that for a densely graded asphalt mixture, the length of the AT-WVT diffusion path is about 2000 times greater than the specimen’s thickness, while the length of the PT-WVT diffusion path is about 15 times greater than the specimen’s thickness. This shows that the length of the water vapor diffusion path is shortened by a factor of approximately 150 after the formation of capillary tubes.

Advances in research on water vapor diffusion in asphalt mixtures are limited by simplified theoretical assumptions and one-dimensional paradigms, making it difficult to fully adapt to the complex multiphase media environment in engineering practice. For example, when constructing diffusion models, refs. [9,24] idealized the pore structure of porous materials to reduce computational complexity, either assuming a uniform spherical distribution of pores, ignoring the connectivity differences between pores, or directly treating asphalt mixtures as homogeneous continuous media without considering the heterogeneity of the interface between aggregate particles and asphalt membranes. Although this simplification can achieve basic theoretical derivation, it significantly deviates from the actual structure of “open connected closed staggered distribution of pores, and micro gaps at the interface between aggregate and asphalt film” in asphalt mixtures, and the capacity to guide engineering practice is limited. In contrast, this study quantifies the influence of pore radius on diffusion by calculating the pore size inside of asphalt mixtures. As such, the calculated results are more accurate.

Previous studies are also marked by one-dimensional, isolated analyses of a single diffusion type. For example, refs. [9,10] only focused on PT-WVT and the gradual accumulation of water vapor in the asphalt layer during the initial stage of newly paved asphalt pavement. Although [21] examined AT-WVT, the authors only focused on the law of continuous penetration of water vapor after reaching dynamic equilibrium in the middle and later stages of road service. This model neglects the entire lifecycle of asphalt pavement from construction to aging, ignoring the evolution of two types of diffusion at different stages. As such, AT-WVT’s dynamic transformation mechanisms are not fully explored. In response to this gap, two types of diffusion coefficients were investigated in this study through a differentiated experimental design. On this basis, the core differences between the two types of diffusion were clarified through quantitative comparison. AT-WVT must overcome diffusion channel construction resistance within the asphalt membrane, with a diffusion coefficient only 1/104 of that of PT-WVT (Table 2), and the diffusion path is greatly affected by closed pores and aggregate barriers, resulting in extremely high tortuosity (tortuosity factor > 2000, as shown in Table 8). PT-WVT relies on formed connected pores and capillary channels, significantly improving diffusion efficiency, with a tortuosity factor of only 12–18 (as shown in Table 7). By establishing diffusion type correlations, this study provides a basis for engineering design.

5. Conclusions

In this study, accumulation-type and permeation-type water vapor diffusion were examined. The diffusion coefficients of AT-WVT and PT-WVT were measured using asphalt, aggregates, and asphalt mixture voids. Then, by comparing the relationship between the actual diffusion coefficient and the effective diffusion coefficient, the tortuosity of the two types of water vapor diffusion paths was calculated.

- (1)

- For asphalt, aggregates, and asphalt mixtures, the PT-WVT diffusion coefficient is approximately four orders of magnitude higher than the AT-WVT diffusion coefficient. This indicates that PT-WVT exhibits significantly higher water vapor diffusion efficiency than AT-WVT.

- (2)

- The tortuosity factor for AT-WVT in asphalt mixtures exceeds 2000. As such, the actual diffusion path length is over 2000 times the specimen’s thickness; in contrast, the tortuosity factor for PT-WVT is approximately 15, reflecting a much shorter and more direct migration path. Water vapor channels formed during the AT-WVT stage shorten the PT-WVT diffusion path by roughly 200 times, further enhancing PT-WVT’s diffusion efficiency.

- (3)

- Due to its high diffusion efficiency, PT-WVT accelerates moisture’s intrusion into asphalt mixtures, making it the primary driver of mid-to-late service water damage (e.g., asphalt–aggregate stripping, fatigue cracking) in pavements.

- (4)

- From an engineering perspective, to mitigate PT-WVT-induced damage, it is recommended to prioritize SBS-modified asphalt (which exhibits 30–50% lower AT-WVT/PT-WVT diffusion rates than base asphalts).

This study clarifies the mechanistic differences and evolutionary relationships between AT-WVT and PT-WVT, providing a basis for optimizing asphalt mixture design and improving pavement durability under hygrothermal loading.

6. Limitations and Future Work

Current diffusion models for asphalt mixtures assume an isotropic pore structure. However, asphalt mixtures exhibit significant anisotropy. Pore characteristics, including elongated voids formed during compaction, orientation aligned with pavement rolling directions, and connectivity, vary with construction processes and service conditions. This oversimplification can lead to deviations between model predictions and real-world diffusion behaviors, especially for pavements with directional compaction or recycled asphalt mixtures.

All AT-WVT&PT-WVT tests in this study were conducted at 20 °C with fixed relative humidity (RH) gradients (AT-WVT: 100% external RH vs. 0% internal RH; PT-WVT: 100% internal RH vs. 60% external RH). While this setup ensures reproducibility, it oversimplifies the environmental variability encountered in field scenarios.

To address these gaps, future research will encompass temperature gradient tests (10–50 °C) and dynamic RH experiments to simulate real environmental fluctuations. Additionally, building on the water vapor diffusion mechanisms elucidated in this study, we will focus on the high porosity and interconnected macropore features of OGFC. We will (1) employ GSA and ASTM E96/E96M tests to quantify AT-WVT/PT-WVT diffusion coefficients and OGFC pore tortuosity factors at different service stages; (2) optimize OGFC gradation and SBS-modified asphalt content and incorporate fiber reinforcement to enhance skeleton stability, thus balancing drainage performance with connected pore control to reduce PT-WVT diffusion efficiency; and (3) establish an OGFC-specific water vapor diffusion model based on laboratory data and conduct tests across different climates to monitor the evolution of moisture-induced damage, providing technical support for OGFC’s anti-moisture damage design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T. and H.Z.; methodology, C.T.; validation, C.T. and X.H.; formal analysis, C.T.; investigation, C.T. and X.H.; resources, C.T. and H.Z.; data curation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T.; writing—review and editing, C.T.; visualization, C.T.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 52308354) Guangdong Provincial Characteristic Innovation Projects for Ordinary Universities (Grant No. 2025KTSCX161); the Doctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Wuyi University (grant nos. BSQD2404 and BSQD2307); and the Jiangmen Science and Technology Project (grant no. 2024800100260007657 and 2024760000400010334). This work was made possible by their generous contributions. And The APC was funded by the Doctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Wuyi University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cheng, D.X.; Little, D.N.; Lytton, R.L.; Holste, J.C. Moisture damage evaluation of asphalt mixtures by considering both moisture diffusion and repeated-load conditions. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2003, 1832, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Hu, D.; Zhang, J.; Pei, J. Investigation of fracture failure and water damage behavior of asphalt mixtures and their correlation with asphalt-aggregate bonding performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Kim, Y.R.; Underwood, B.S.; Guddati, M. Modeling damage caused by combined thermal and traffic loading using viscoelastic continuum damage theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 418, 135425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, W.N.H.M.; Allias, N.F.; Yaacob, H.; Al-Saffar, Z.H.; Hashim, M.H. Utilisation of Sawdust and Charcoal Ash as Sustainable Modified Bitumen. Smart Green Mater. 2024, 1, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, Z.; Sani, W.N.H.M.; Azmi, N.N.D.N.; Pangestika, S.H.; Hashim, M.H. Effect of Kaolin on Asphalt Concrete Properties Under Aging Conditions. Smart Green Mater. 2024, 1, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Xi, L.; Luo, R.; Huang, T.; Luo, J. Effect of water vapor concentration on adhesion between asphalt and aggregate. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, T.; Wen, X.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z. Experimental investigation of water vapor concentration on fracture properties of asphalt concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arambula, E.; Caro, S.; Masad, E. Experimental Measurement and Numerical Simulation of Water Vapor Diffusion through Asphalt Pavement Materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2010, 22, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Liu, Z.; Huang, T.; Tu, C. Water vapor passing through asphalt mixtures under different relative humidity differentials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 165, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Tu, C. Actual diffusivities and diffusion paths of water vapor in asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 207, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Luo, R. Investigation of effect of temperature on water vapor diffusing into asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 1204–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Huang, T.T. Development of a three-dimensional diffusion model for water vapor diffusing into asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 179, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arambula, E.; Masad, E.; Bulut, R.; Lytton, R. Measurements of moisture suction and diffusion coefficient in hot-mix asphalt and their relationships to moisture damage. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2006, 1970, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, K.L.; Bhasin, A.; Little, D.N.; Lytton, R.L. Experimental Measurement of Water Diffusion through Fine Aggregate Mixtures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2011, 23, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Luo, R.; Lytton, R.L. Modeling water vapor diffusion in pavement and its influence on fatigue crack growth of fine aggregate mixture. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, K.L.; Bhasin, A.; Little, D.N. Measurement of Water Diffusion in Asphalt Binders Using Fourier Transform Infrared–Attenuated Total Reflectance. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2179, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Tarefder, R.A. Behavior of asphalt mastic films under laboratory controlled humidity conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 78, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Luo, R.; Huang, T. Numerical Simulation of Moisture Diffusion in the Microstructure of Asphalt Mixtures. Materials 2023, 16, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, R.G. Moisture damage in asphalt concrete. Nchrp Synth. Highw. Pract. 1991, 175, 70–101, Report No. PB-92-143502/XAB. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, I.; Moriyoshi, A.; Hachiya, Y.; Nagaoka, N. New test method for moisture permeation in bituminous mixtures. J. Jpn. Pet. Inst. 2006, 49, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Aubeny, C.P.; Bulut, R.; Lytton, R.L. Two-dimensional moisture flow–soil deformation model for application to pavement design. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2006, 1967, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, E.; Masad, E.; Lytton, R.; Bulut, R. Measurements of the moisture diffusion coefficient of asphalt mixtures and its relationship to mixture composition. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2009, 10, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E96/E96M16; Standard Test Methods for Water-Vapor Transmission of Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Radovskiy, B. Analytical Formulas for Film Thickness in Compacted Asphalt Mixture. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003, 1829, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, S. Diffusion and dispersion in porous media. AIChE J. 1967, 13, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Luo, R. Development of Two-Phase Diffusion Model Consisting of Free and Bound Water Molecules for Water Vapor Diffusing into Asphalt Mixtures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04021450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, S.; Masad, E.; Bhasin, A.; Little, D.; Sanchez-Silva, M. Probabilistic Modeling of the Effect of Air Voids on the Mechanical Performance of Asphalt Mixtures Subjected to Moisture Diffusion. J. Assoc. Asph. Paving Technol. 2010, 79, 221. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Duan, W.; Guo, Z.; Dong, R. A comprehensive review on the diffusion and blending states of aged and virgin asphalt in recycled asphalt mixtures: Mechanism, model and characterization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 433, 136689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).