Abstract

As urbanization accelerates, children’s safety when crossing urban streets has become an increasingly prominent concern. However, current street designs and visual guidance facilities are largely configured around adult users and tend to overlook children’s distinct cognitive and perceptual characteristics. In this study, we used seven virtual reality (VR) street-crossing scenarios and combined questionnaires, eye tracking, and motion capture to evaluate how five types of visual guidance elements—Footprint (stop) markings and Traffic bollard, Color-Coded Arrows, Look left markings, Tactile Paving Patterns, and Stop line—affect children’s street-crossing behavior. The results show that Footprint (stop) markings and Traffic bollard clearly enhance children’s Stopping–Scanning Awareness, prompting them to slow down and briefly pause within the decision zone. The Look left markings provide only limited cues for Left–Right Scanning in both adults and children. Tactile Paving Patterns and Color-Coded Arrows effectively attract children’s visual attention, but may weaken their judgement of street-crossing risk. The Stop line strengthens the visual boundary and increases environmental monitoring awareness among all participants; however, this study did not observe a clear improvement in Gait variability. By extending theories of children’s traffic behavior, this study also highlights that some facilities labeled as “child-friendly” may be over-designed or cognitively misaligned with children’s actual perceptual and decision-making processes. These findings provide empirical evidence for optimizing street facilities and for developing related technical standards and public policies.

1. Introduction

With the global promotion of the “child-friendly city” agenda, children’s travel safety and spatial rights in urban environments have received sustained attention. Street crossing is the most frequent and critical component of children’s independent travel, and it directly affects both their life safety and everyday quality of life. However, most urban traffic systems and street designs still assume adults as the primary users and pay limited attention to children’s differences in eye height, cognition, reaction speed, and behavioral patterns, thereby exposing children to higher risks when crossing the street. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that road traffic injury has long been the leading cause of death among children and adolescents aged 5–29 years [1]. In China, road segments around schools account for 28% of all traffic crashes involving children [2], revealing inadequate child-adaptiveness in current traffic safety governance.

Existing interventions for children’s traffic safety focus mainly on infrastructure provision and traffic-rule education, but they rarely address the full “perception–decision–action” process of child pedestrians. As a result, some facilities show limited effectiveness and may even introduce new risks by unintentionally guiding unsafe behavior. To improve children’s travel environments, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has proposed the Child Friendly Cities Initiative (CFCI), which advocates child-centered traffic safety design and environmental improvements [3]. In parallel, China has issued policies to promote “smart transportation” and “child-friendly streets” [4], providing an institutional backdrop and application context for the present study.

1.1. Present Study

1.1.1. Risky Pedestrian Behaviors in Children

Children typically exhibit divided attention, insufficient judgment, and impulsive behavior when crossing streets, patterns that are closely tied to their stage of cognitive development [5,6]. Studies indicate that, due to still-maturing cognitive abilities [7], a relatively narrow visual search field [8,9], lagging hazard perception (HP) [10,11], and weaker behavioral control, children face higher risks when navigating road environments. A large body of field observations and experimental work [12,13,14,15] has shown that children frequently engage in high-risk behaviors, such as entering the roadway without sufficient scanning or failing to wait at the curb, with these tendencies being particularly pronounced in younger age groups [6]. At unsignalized intersections or complex traffic nodes, such unsafe behaviors occur more frequently, reflecting marked age-related differences in children’s perception of danger [16].

Executive function theory [17] suggests that children have developmental limitations in cognitive control capacities such as sustained attention and rapid decision-making, making it difficult for them to respond promptly to rapidly changing traffic situations. The hazard perception framework [18] further indicates that children’s limited ability to detect and evaluate risks leads them to overlook latent hazards, thereby increasing the likelihood of crashes [8,9]. In recent years, the application of new technologies such as drone-based video recording [19,20] has shown that children face a high level of traffic conflict risk when crossing near school zones. These studies also suggest that roadway type, lighting conditions, and driver behavior significantly influence crash severity, underscoring the particular vulnerability of children within traffic environments.

1.1.2. Evolution of Experimental Methods and Technological Applications

Research methods for studying children’s street-crossing behavior have evolved from traditional field observations to multi-technology integration. Early work mainly relied on video recordings and on-site observation around school zones or typical intersections to characterize children’s crossing patterns in real traffic environments [21,22,23]. This approach offers high ecological validity but is constrained by observer effects, limited control over environmental conditions, and challenges in data reproducibility. These studies also showed that younger children exhibit systematic biases when observing traffic flow and judging vehicle speed and distance, making them more likely to take high-risk decisions [21,22,23]. Before–after comparisons of zebra crossing redesign further indicate that engineering measures such as speed-reduction markings and Stop line can help reduce vehicle speeds and strengthen yielding behavior at zebra crossings [24].

The introduction of virtual reality (VR) and eye tracking has expanded the methodological toolkit. VR can construct rich yet controllable traffic scenes while eliminating real-world crash risk, thereby balancing ecological validity and experimental control [25]. Existing studies have used immersive VR training to substantially improve the safety performance of 9–11-year-old children in scenarios such as running a red light, running across the street, and judging vehicle gaps [26], or have relied on “virtual school route” platforms to enhance adolescents’ traffic safety knowledge and risk-management skills [27]. Together, these findings suggest that virtual simulation holds considerable potential for safety education and behavioral training [10,28,29,30,31,32,33].

Eye tracking provides critical data for understanding the visual foundations of children’s street-crossing behavior. It can continuously record attention-allocation patterns and reveal fixation hotspots and switching characteristics under both static and dynamic stimuli [34,35]. In recent years, researchers have increasingly integrated embedded eye tracking with VR systems and combined them with motion capture [32,36,37,38], enabling synchronous collection of multi-channel data under more naturalistic conditions and substantially enhancing both ecological validity and explanatory power.

However, much existing work still relies on a single technological pathway and lacks systematic integration of multimodal data. For example, although Baldassa et al. [26] made extensive use of VR for assessment and training, they did not incorporate behavioral indicators such as gait stability. In this study, we integrate VR, eye tracking, motion capture, and questionnaire surveys to refine the characterization of children’s visual attention patterns while simultaneously analyzing their gait and decision responses, thereby providing more comprehensive evidence for optimizing visual guidance facilities.

1.1.3. Visual Elements of Street Crossing Facilities

To improve safety at critical nodes along school travel routes, many cities worldwide have implemented street redesign interventions with visual guidance and warning functions. Common measures include Look left markings, Tactile Paving Patterns, Color-Coded Arrows, and colored stripes (Figure 1). For example, the “Rainbow Corridor” in the Baihua child-friendly street in Shenzhen and the Tactile Paving Patterns zebra crossing in the Jinan child-friendly street not only enhance the recognizability and playfulness of the streetscape, but also serve as important carriers of the child-friendly city concept.

Figure 1.

Real-world Cases of School Route Zebra Crossing Design. Note: The main information in the figure includes: the text on the far left image reads “Look Left,” the second image reads “Look Left,” and the text on the far right image reads “Stop at Red, Go at Green.”

However, related studies indicate that the design of many existing visual elements is largely informed by an “adult perspective” and is not fully aligned with children’s visual cognition and behavioral development. Colored visual elements can exert bidirectional effects on traffic behavior: guidance facilities such as Footprint (stop) markings can enhance children’s Stopping–Scanning Awareness, yet overly complex patterns may fixate their attention on the pavement and weaken monitoring of the surrounding dynamic traffic environment [34]. Research on Tactile Paving Patterns zebra crossings likewise suggests that, although these designs can strengthen drivers’ yielding behavior, their specific effects on child pedestrians remain unclear [24,39,40].

Therefore, it is necessary not only to assess the positive roles of visual elements, but also to systematically identify the unintended behaviors they may induce, in order to support more precise facility optimization. This is particularly relevant for widely deployed “Look left” text markings. Designed according to adult cognitive patterns, they often fail to account for children’s eye height, attention allocation, and spatial judgment characteristics, so their cueing effect may be substantially attenuated in child populations. Targeted improvements in installation height and modes of information presentation are urgently needed.

1.2. Research Goals and Hypotheses

Although behavioral observations and crash analyses on children’s street-crossing safety have accumulated substantial evidence, the mechanisms by which visual elements influence children’s street-crossing behavior remain insufficiently explored. Most existing studies focus on traditional factors such as traffic signals and speed control, while paying limited attention to the effectiveness of visual guidance facilities in different environments and their alignment with children’s cognitive and behavioral development. In practice, design decisions often rely on professional judgment rather than an evidence-based framework. Current traffic safety interventions tend to emphasize hardware provision and rule-based education, but overlook children’s specific perception–decision characteristics, leading to discrepancies between facility design and behavioral responses. Although VR and eye tracking provide new tools for studying children’s street crossing, many studies remain confined to a single-technology approach and lack coordinated analysis of multimodal data.

In response, this study develops a multimodal experimental paradigm that integrates VR simulation, eye tracking, and motion capture to systematically evaluate how different visual elements (e.g., Footprint (stop) markings, Traffic bollard, Look left markings, and Color-Coded Arrows) intervene in children’s risky behavior by influencing key indicators such as Stopping–Scanning, Left–Right Scanning, Efficient Crossing, and Gait variability. The goal is to provide empirical support for the refined design of visual facilities and to advance the construction of child-friendly traffic environments.

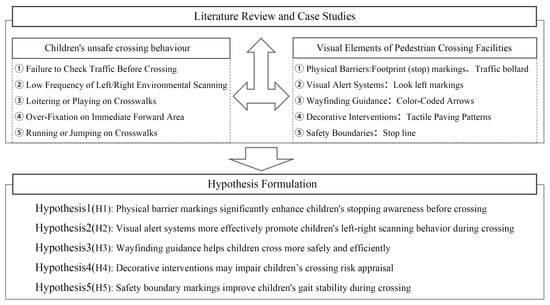

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes five testable hypotheses (Figure 2) and defines corresponding quantitative decision thresholds:

Figure 2.

Hypothesis Derivation.

Hypothesis 1 (H1) (Physical Barriers—Stopping Awareness).

Physical barriers and stopping markers increase children’s stopping and observing behavior before crossing. Compared with SC0, an increase in stopping duration of ≥1 s is considered supportive.

Hypothesis 2 (H2) (Visual Alert Systems—Left–Right Scanning).

Visual alert systems enhance children’s Left–Right Scanning of traffic. An increase of ≥5% in fixation proportion on the left/right zebra crossings AOI relative to SC0 is considered supportive.

Hypothesis 3 (H3) (Wayfinding Guidance—Efficient Crossing).

Wayfinding guidance facilities improve the safety and efficiency of children’s street crossing. An increase of ≥0.25 m/s in mean walking speed compared with SC0 is considered supportive.

Hypothesis 4 (H4) (Decorative Interventions—attention distraction).

Decorative interventions strongly attract children’s attention and may interfere with risk assessment. An increase of ≥5% in fixation proportion on the zebra crossings AOI relative to SC0 is considered supportive.

Hypothesis 5 (H5) (Safety Boundaries—gait stability).

Safety boundary markings improve children’s Gait variability. An increase of ≥0.2 in the corresponding indicators compared with SC0 is considered supportive.

Subsequent statistical analyses will use these thresholds to determine whether each hypothesis is supported under different test conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

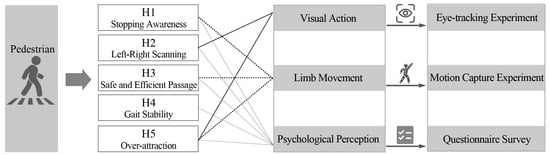

In this study, we adopt a multimodal experimental paradigm and use three data-collection methods—questionnaire surveys, eye tracking, and motion capture—to systematically evaluate the effects of visual guidance elements on children’s street-crossing behavior.

2.1. Experimental Design and Data Collection

Based on the Unity 2019.4.26f1c1 engine and VR plug-ins, we developed a virtual reality platform that reproduces typical urban street-crossing scenarios with a baseline zebra crossing and multiple visual guidance elements [41,42]. Participants completed a series of street-crossing tasks from a first-person perspective, and the overall experimental framework is shown in Figure 3. By combining different visual elements, we defined multiple experimental conditions and adopted a three-modality data-collection protocol (Figure 4): questionnaire surveys captured subjective perception and safety cognition, eye tracking recorded visual attention characteristics, and motion capture measured locomotor parameters, enabling full-process monitoring from cognition to behavioral response.

Figure 3.

Research Framework for Child Pedestrian Safety Experiments.

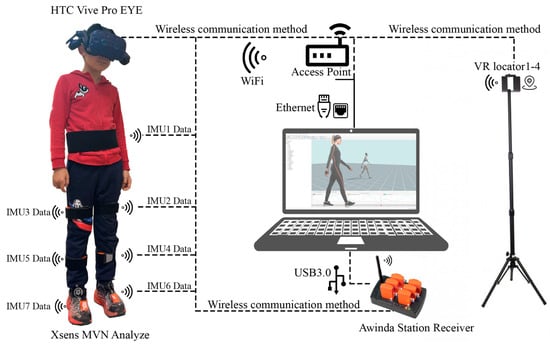

Figure 4.

Experimental Equipment.

Eye-movement data were collected using an HTC Vive Pro Eye headset, sourced from Jinfa Technology Limited Company, located in Beijing, China, at a sampling rate of 120 Hz, which allows real-time recording of fixation locations, fixation durations, and gaze trajectories during street crossing with high spatial accuracy [43,44,45]. Before each experiment, a 5-point calibration was performed (error threshold < 0.5°), and data were processed using the Identification by Velocity-Threshold (I-VT) algorithm. Cases with more than 20% data loss or a calibration error greater than 1.5° were excluded to ensure data quality.

Motion-capture data were acquired using an Xsens MVN Awinda system, a markerless full-body motion-capture system, sourced from Jinfa Technology Limited Company, located in Beijing, China, at a sampling rate of 120 Hz [46]. The raw signals were processed with a 5 Hz low-pass filter and a Kalman filter, and step length, cadence, and gait cycle were extracted. For each indicator, the standard deviation and coefficient of variation (CV) were computed to characterize gait stability and consistency in children and adults during street crossing. By synchronously collecting and cross-validating questionnaire, eye-tracking, and motion-capture data, this study comprehensively documented behavioral responses in VR street-crossing scenarios and examined how visual guidance elements influence street-crossing behavior.

To ensure adequate statistical power, we conducted an a priori power analysis for five primary outcome measures—Zebra crossings AOI, Left/right zebra crossings AOI, Average walking speed, Gait variability (including walking speed, step length, and cadence), and Stopping duration (the time from scene onset to stepping onto the zebra crossing, used to index Stopping–Scanning Awareness). Assuming a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), a significance level of 0.05, and a desired statistical power of at least 0.80, the analysis indicated a minimum required sample size of 32 participants. We ultimately recruited 59 participants, which met the power requirement and provided additional margin for subgroup analyses and extensions of the results.

2.2. Participants

The experiment was conducted at the Xicheng Campus of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture and included 59 participants, divided into a child group and an adult group. The child group comprised 36 children aged 6–10 years (mean age = 8.14 years). Following developmental psychology theory, they were further divided into a lower-grade subgroup (6–8 years) and a middle–upper-grade subgroup (9–10 years). Children aged 6–8 years are still in a phase of rapid development of cognitive and executive functions and have limited ability to cope with traffic situations independently, whereas children aged 9–10 years exhibit relatively more mature hazard perception and judgment, making them suitable for cross-age comparisons. To enhance ecological validity, child participants represented a range of everyday school-commute modes, including parent-accompanied travel, walking with peers, independent walking, and other transport modes.

The adult group consisted of 23 university students, with a mean age of 20.1 years and a mean height of 173.5 cm. Their cognitive and behavioral patterns are relatively stable and thus served as a reference benchmark for the child group.

Participants were recruited via primary school parent groups and university online platforms. All participants (with legal guardians signing on behalf of minors) provided written informed consent before the experiment. Inclusion criteria were: being in good physical health; having no visual or mobility impairments (or corrected-to-normal vision); being able to read and complete the questionnaires independently; and meeting safety requirements for VR experiments. Throughout the sessions, research assistants supervised the procedure, provided only procedural instructions (e.g., duration, privacy, and the right to withdraw), and did not read items aloud or prompt answers. On-site records and verbal feedback indicated no physical discomfort or difficulties in reading or comprehension. The experiment was scheduled during the winter vacation period to minimize academic and other external interferences. Participants’ demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic Information of Participants.

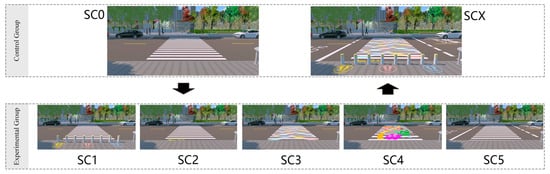

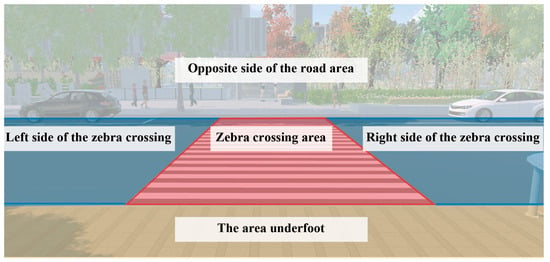

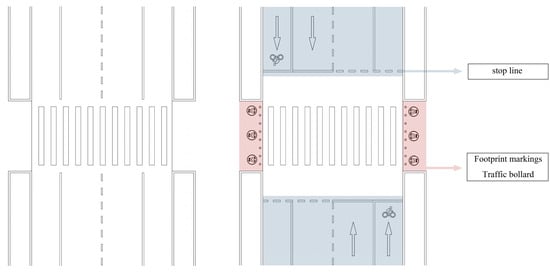

2.3. Experimental Scenario Design

This study focused on the effects of economically feasible, easy-to-implement “soft measures” on street-crossing behavior. Using the Unity3D engine, we constructed seven VR street-crossing scenarios that simulated a typical urban road environment with a zebra crossing, traffic signs, and pavement markings. These scenarios preserved ecological validity while enhancing experimental control and reproducibility. In each scenario, different visual elements were superimposed on the same baseline zebra crossing (Figure 5 and Table 2), and key regions were segmented into multiple Areas of Interest (AOI) to precisely record participants’ fixations on critical locations (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Schematics of Each Experimental Scenario (Including Control and Experimental Scenarios), (For the definitions of SC0–SCX, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Experimental Scenarios and Element Groupings.

Figure 6.

AOI Partitioning Diagram.

The scenarios were prototyped from a straight zebra crossing on a city frontage road near a primary school in Beijing. The cross-section consisted of two motor-vehicle lanes (3.5 m per lane) and two non-motorized lanes (2.5 m per lane). The zebra crossing was 4.0 m wide, and the curb-to-curb width was 13.0 m, consistent with Chinese urban road design standards, with no central refuge island or physical separation facilities.

To isolate the net effect of ground-level visual guidance and to meet ethical and safety requirements, the VR environment did not include dynamic traffic flow, driver–pedestrian interactions, or other pedestrian interference. The traffic context was composed solely of static signs and pavement markings, and the soundscape was maintained as constant background noise.

To ensure consistency and comparability across scenarios, we controlled the following aspects:

- (1)

- Geometric dimensions: All seven scenarios shared identical geometry and layout. The total width was fixed at 13.0 m, and the widths of each lane and the zebra crossing remained unchanged.

- (2)

- AOI spatial calibration: Zebra crossings, traffic signs, and other key visual guidance elements were precisely positioned within predefined AOI regions. AOI size and viewing distance were kept constant across scenarios. Viewing distance was dynamically calibrated according to each participant’s height to maintain a consistent viewing angle.

- (3)

- Eye-height adaptation: Based on each participant’s measured height, the VR viewpoint height was set to “height − 10 cm” to approximate eye level in a natural standing posture and reduce the impact of height differences on visual perception.

- (4)

- Lighting parameters: Luminance and contrast were standardized across all scenarios to ensure consistent recognizability of visual elements and to avoid confounding behavioral responses due to differences in ambient lighting.

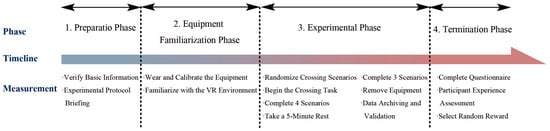

2.4. Experimental Procedure

The experimental procedure is shown in Figure 7. The study was conducted in a quiet, controlled indoor environment to minimize external interference. Participants included 36 children aged 6–10 years and 23 adults. During the preparation phase, researchers collected basic physical information (e.g., height, weight), provided standardized instructions on the experimental procedure and precautions, and completed device fitting. The eye-tracking and motion-capture systems were calibrated by trained staff, and all participants completed a VR familiarization session before the formal experiment to reduce learning effects associated with first-time use.

Figure 7.

Experimental Procedure.

Participants were required to complete seven virtual street-crossing tasks in sequence. A fully randomized presentation design was used: a random permutation of the seven scenarios was generated by computer, without stratification by difficulty or familiarity and without any fixed order. Each participant experienced each scenario only once to ensure independence and coverage of the measurements. To control fatigue effects, the experiment was divided into two blocks: after completing the first four scenarios, participants rested for 5 min before completing the remaining three scenarios.

To examine potential order effects (e.g., cumulative learning or fatigue), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the five primary outcome measures. As shown in Table 3, the order factor did not have a significant effect on any of the primary indicators (all p > 0.05), suggesting that the experimental design effectively limited sequence-related interference.

Table 3.

Analysis of order effects.

The entire experimental procedure strictly complied with ethical guidelines, and participants were free to withdraw at any stage without penalty. Eye-movement trajectories and kinematic data were recorded continuously throughout the experiment, and data quality was checked immediately after each trial so that invalid segments could be removed in a timely manner. After completing all tasks, participants removed the equipment and completed a post-experiment subjective experience questionnaire.

2.5. Data Exclusion and Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Data Exclusion

Some data were missing due to equipment malfunction (e.g., motion-capture sensor shutdown caused by low battery, signal loss, accidental sensor detachment, or failure of eye-tracking calibration and recording) or because a few participants, due to nervousness, did not complete all seven scenarios. Specifically, four datasets were excluded from the child group and four from the adult group for eye-tracking data, and three datasets were excluded from each group for motion-capture data.

These missing data were treated as missing at random (MAR): the probability of missingness was related to observed variables but not to the unobserved values themselves. After rigorous data cleaning, the remaining sample was retained for subsequent statistical analyses. This handling is unlikely to introduce systematic bias into the main findings or to substantially compromise external validity.

2.5.2. Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests were two-sided, with the significance level set at α = 0.05. We report 95% confidence intervals and effect sizes for inferential results. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. All analyses were conducted primarily in MATLAB R205b (Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox).

(1) Questionnaire and Behavioral Rating Data

Subjective ratings such as perceived safety and observation awareness were first summarized using descriptive statistics. Pearson correlation coefficients were then computed for selected variable pairs to characterize linear associations between perceived safety and behavioral awareness across scenarios. Environmental perception voting data (e.g., Stopping Awareness, Left-Right Scanning) were converted to proportions and visualized using radar charts (spider plots) to illustrate perceptual differences between scenarios and groups; these analyses were primarily descriptive.

(2) Linear mixed-effects models for primary outcome measures

For each of the five primary outcome measures, we fitted a separate linear mixed-effects model. Fixed effects included Group (children vs. adults), Scenario (SC0–SCX, with SC0 as the reference), and their interaction Group × Scenario. A subject-level random intercept (Subject_ID) was included to account for within-participant correlation in the repeated measures. Coding used the child group and SC0 as the baseline; thus, Group_Adult represents the difference between adults and children in the baseline scenario, Scenario_SCk represents the change from SC0 to SCk in children, and the interaction term Group_Adult:Scenario_SCk reflects the group difference in the magnitude of change from SC0 to SCk.

For each fixed effect, we report the regression coefficient (Estimate), standard error (SE), t value, degrees of freedom, p value, and 95% confidence interval, together with a standardized effect size. For the subject-level random intercept, we report its variance/standard deviation, and we provide the marginal R2 (proportion of variance explained by the fixed effects alone) and conditional R2 (proportion of variance explained by both fixed and random effects) to assess model explanatory power. To control for multiplicity, all Scenario-related fixed effects within each outcome (Scenario main effects and Group × Scenario interaction terms) were treated as a single family of tests. The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used to control the false discovery rate (FDR, q = 0.05), and inference was based on FDR-adjusted significance levels.

(3) Exploratory comparisons between child age subgroups

Given developmental differences between children aged 6–8 and 9–10 years, we conducted exploratory analyses within the child group. Proportions of fixations for each Scenario–AOI combination were logit-transformed, and Welch’s t tests were used to compare the two age subgroups. Holm adjustment was applied to correct p values for multiple comparisons, and Cohen’s d was reported as the effect size, to assess whether the legibility of different visual elements was comparable across the two age ranges.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Data Analysis

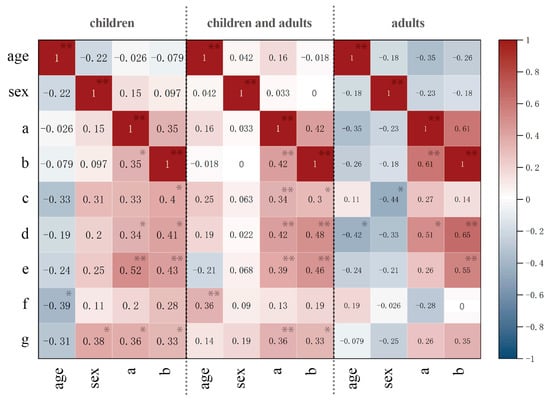

3.1.1. Correlation Analysis of Perception of Basic Scenario and Effectiveness of Visual Elements

Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for perceived safety and Stopping–Scanning Awareness in the baseline scenario SC0, as well as for behavioral awareness ratings in each visual-element scenario; results are shown in Figure 8. The correlation analysis indicated that children’s age was significantly negatively associated with the impact of SC4 (r = −0.39, p < 0.05), meaning younger children were more easily disturbed by complex Tactile Paving Patterns. When all participants were considered together, age was significantly positively associated with the impact of SC4 (r = 0.36, p < 0.05), suggesting that adults were more likely to be drawn to strong visual stimuli. Individuals who reported higher perceived safety and stronger observation behavior in SC0 also showed more adaptive behavioral responses in the auxiliary visual scenarios, suggesting that safety awareness may partially transfer across contexts.

Figure 8.

Correlation Analysis. Note: * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). a: Participants’ perceived safety in SC0. b: Participants’ Stopping–Scanning Awareness in SC0. c: Participants’ Stopping–Scanning Awareness in SC1 (Footprint (stop) markings, Traffic bollard). d: Participants’ Left-Right Scanning awareness in SC2 (Look left markings). e: Participants’ Efficient Crossing awareness in SC3 (Color-Coded Arrows). f: Degree of distraction caused by SC4 (Tactile Paving Patterns). g: Participants’ perceived safety and stability in SC5 (Stop line).

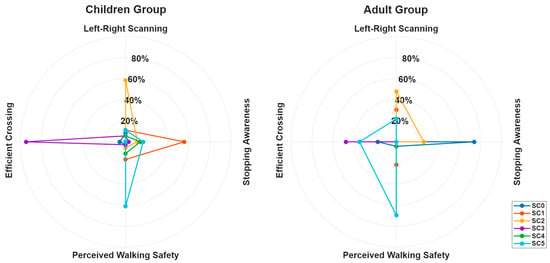

3.1.2. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of the Importance of Environmental Perception Awareness in Different Scenarios

The analysis focused on four dimensions of environmental perception awareness—Stopping Awareness, Left-Right Scanning, Efficient Crossing, and Perceived Walking Safety—and compared voting choices between the child and adult groups. For each scenario, six response options were provided, and the proportion of votes for each option in both groups was recorded and normalized. These standardized proportions were then visualized using radar charts (spider plots) to compare preference patterns across scenarios (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Environmental Perception Behavior Analysis -Spider Plots.

The results showed that adults already exhibited a strong tendency to stop in SC0, so additional visual elements had limited impact on their Stopping behavior. In contrast, children were more sensitive to Footprint (stop) markings and Traffic bollard, and their Stopping Awareness increased markedly in the corresponding scenarios.

For Left-Right Scanning, adults showed enhanced observation behavior in SC1, SC2, and SC5, whereas children exhibited the largest improvement in SC2 (Look left markings). For Efficient Crossing, both SC3 (Colored Pedestrian Guidance Arrows) and SCX (all elements combined) improved crossing efficiency in both groups, with children showing a particularly pronounced increase in Efficient Crossing Awareness in SC3. Regarding Perceived Walking Safety, SC5 (Stop line) received the highest safety ratings in both groups. Overall, visual elements exerted stronger effects on behavioral awareness dimensions in children than in adults, and elements such as Look left markings, Colored Pedestrian Guidance Arrows, and Stop line showed distinct advantages across different awareness dimensions.

3.2. Eye Tracking Analysis of AOIs

Eye-tracking data were processed and statistically analyzed using a VR plug-in and MATLAB. As described in Section 2.5.2, a separate linear mixed-effects model was fitted for each eye-tracking outcome. Fixed effects included Group (children vs. adults), Scenario (SC0–SCX), and their Group × Scenario interaction. Subject_ID was specified as a random intercept.

In the following, we focus on the main fixed effects related to Group and Scenario. The main and interaction effects of Order were small and non-significant (see Appendix A Table A1 and Table A2) and are therefore not discussed further in the main text. This section concentrates on the proportion of fixation duration within the Zebra crossings AOI and the Left/right zebra crossings AOI.

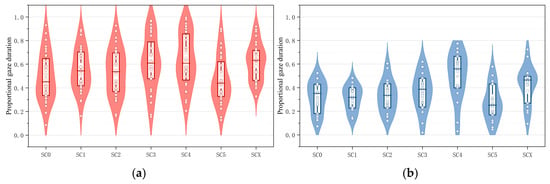

(1) Gaze proportion on Zebra crossings AOI

As shown in Figure 10 and Appendix A Table A1, under the baseline condition (child group, SC0), the mean proportion of fixation time within the Zebra crossings AOI was about 0.49 (Estimate = 0.490, 95% CI [0.428, 0.553]). In the same baseline scenario, adults showed a significantly lower fixation proportion on this AOI than children (Group--Adult: Estimate = −0.171, 95% CI [−0.274, −0.068], p = 0.0012), but the standardized effect size was very small (|effect size| ≈ 0.015), indicating that although the between-group difference in attention to the zebra crossing itself was statistically significant, its practical magnitude was limited.

Figure 10.

Proportional gaze duration on specified AOIs at zebra crossings: Children vs. adults. (a) Children Group; (b) Adult Group.

Using the child group as the reference, most intervention scenarios increased the fixation proportion on the Zebra crossings AOI relative to SC0. The scenario main effects were most pronounced in SC3 (Color-Coded Arrows), SC4 (Tactile Paving Patterns), and SCX (combined scheme) (SC3: Estimate = 0.119, 95% CI [0.059, 0.179], p ≈ 1.1 × 10−4; SC4: Estimate = 0.145, 95% CI [0.086, 0.205], p ≈ 2.5 × 10−6; SCX: Estimate = 0.128, 95% CI [0.069, 0.188], p ≈ 3.0 × 10−5). The corresponding standardized effect sizes were in the small range (effect size ≈ 0.010–0.013), consistently indicating that Color-Coded Arrows and Tactile Paving Patterns further enhanced children’s visual focus on the zebra crossing itself. SC1 and SC2 showed only trend-level or non-significant increases (e.g., SC1: p = 0.056), and the main effect of SC5 (Stop line) was not significant (Estimate = −0.025, 95% CI [−0.085, 0.034], p = 0.40).

The Group × Scenario interaction terms for the Zebra crossings AOI were generally non-significant (all p > 0.12, effect sizes near 0), suggesting that the “pattern of increased fixation proportion relative to SC0” was broadly similar between children and adults, with no clear age-group–specific gains.

Because multiple Scenario-related tests were conducted for the same outcome, all scenario main effects and Group × Scenario interactions were treated as a single family of tests, and the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used to control the false discovery rate (FDR; q = 0.05). After correction, the scenario main effects for SC3, SC4, and SCX remained statistically significant, whereas SC1 shifted from marginally significant to non-significant, indicating that the facilitative effects of Color-Coded Arrows and Tactile Paving Patterns on zebra-crossing fixations were robust under multiple-comparison control. The marginal and conditional R2 of this mixed model were both very close to 1 (R2_marginal ≈ 0.9998, R2_conditional ≈ 0.9999), implying that the fixed effects together with between-subject random variation almost completely accounted for the variance in this outcome. The standard deviation of the Subject_ID random intercept was about 0.13 (95% CI [0.11, 0.17]), indicating some stable individual differences in overall fixation levels on the zebra crossing.

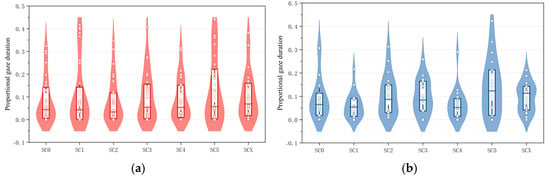

(2) Gaze proportion on left/right zebra crossings AOI

The Left/right zebra crossings AOI primarily reflects participants’ Left-Right Scanning behavior in the areas on both sides of the zebra crossing. As shown in Figure 11 and Appendix A Table A2, under the baseline scenario SC0, the mean fixation proportion on this AOI was close to zero in the child group (Estimate = 0.008, 95% CI [−0.009, 0.025], p = 0.36), indicating that, in the absence of any visual guidance, children allocated relatively little attention to the left and right sides. In contrast, adults showed a significantly higher fixation proportion than children in the baseline scenario (Group-Adult: Estimate = 0.083, 95% CI [0.054, 0.111], p ≈ 2.3 × 10−8), although the standardized effect size was again small (effect size ≈ 0.007). This suggests that adults were generally more inclined to distribute part of their gaze to both sides, but the magnitude of this difference was modest on the present measurement scale.

Figure 11.

Proportional gaze duration on left/right AOIs at zebra crossings: Children versus (vs.) adults. (a) Children Group; (b) Adult Group.

Regarding scenario main effects, SC1–SCX did not significantly change the Left/right AOI fixation proportion in the child group (all 95% CIs crossed zero, p ≥ 0.64), and no stable scenario main effect comparable to that for the Zebra crossings AOI was observed. Among the Group × Scenario interactions, Group--Adult: Scenario_SC5 reached significance before correction (Estimate = 0.044, 95% CI [0.012, 0.076], p = 0.0073), suggesting an additional increase in adults’ fixation allocation to the two sides of the zebra crossing relative to children in the Stop line scenario (SC5). Group-Adult: Scenario_SC1 showed a slight negative interaction (Estimate = −0.033, 95% CI [−0.065, −0.001], p = 0.042), indicating a narrowed group difference in Left-Right Scanning under the Look left markings scenario. However, all of these interaction effects had extremely small standardized magnitudes (|effect size| ≤ 0.004).

When all scenario main effects and Group × Scenario interactions for this outcome were treated as a single family of tests and corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR procedure, none of the scenario-specific effects remained significant; only the main effect of Group stayed significant. This pattern supports a robust conclusion that, across scenarios, adults were generally more likely than children to allocate part of their visual attention to the areas on both sides of the zebra crossing, whereas the additional modulation of this Left-Right Scanning behavior by specific scenarios was relatively limited. The marginal and conditional R2 of the Left/right AOI model were also close to 1 (R2_marginal ≈ 0.99998, R2_conditional ≈ 0.99999), and the standard deviation of the Subject_ID random intercept was about 0.03 (95% CI [0.024, 0.038]), indicating only small stable individual differences on this outcome.

(3) Age subgroup differences among children

To account for potential cognitive differences associated with age, we further compared gaze allocation between the two child subgroups (6–8 years vs. 9–10 years) across Scenario × AOI conditions. For logit-transformed fixation proportions, Welch’s t tests were applied, and Holm adjustment was used to correct for multiple comparisons. As shown in Table 4, all adjusted p values (p_adj) for Scenario × AOI comparisons exceeded 0.05 (minimum p_adj ≈ 0.63), and no statistically significant age-group differences were detected. Most effect sizes fell within the small range (|d| ≈ 0.11–0.36), with a few comparisons showing medium-sized trends (e.g., SCX, AOI = Left/right zebra crossings: Diff = −1.07, d ≈ −0.64), which nevertheless did not reach significance after multiple-comparison correction. Overall, the presentation of key visual elements across scenarios appeared to have broadly similar “legibility” for children in both age ranges. However, “non-significant” does not imply “identical,” and these patterns should be further examined in larger samples.

Table 4.

Gaze allocation differences across Scene × AOI between child subgroups (p_adj and effect size).

3.3. Motion Capture Data Analysis

For the three behavioral outcome measures—Average walking speed, Gait variability, and Stopping duration—we applied the same linear mixed-effects modeling approach as in Section 3.2. Fixed effects included Group, Scenario, and their Group × Scenario interaction, with Order entered as a covariate and Subject_ID specified as a random intercept. Below, we report the estimated fixed effects, p values, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), effect sizes, and the variance of the random intercept together with R2 values; detailed numerical results are provided in Appendix A Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5.

(1) Average walking speed

Under the baseline condition (child group, SC0), Average walking speed was approximately 2.88 m/s (Estimate = 2.88, 95% CI [2.55, 3.21]). In the same baseline scenario, adults walked slightly more slowly than children (Group_Adult: Estimate = −0.31, 95% CI [−0.85, 0.23], p = 0.25). The confidence interval crossed zero, and the standardized effect size was very small (effect size ≈ −0.027), indicating no clear systematic difference in baseline walking speed between children and adults.

Using the child group as the reference, the estimated effects of the intervention scenarios relative to SC0 were generally small. For SC1–SC5 and SCX, the absolute values of the coefficients were all below 0.21 m/s (e.g., SC3: Estimate = 0.21, 95% CI [−0.13, 0.55]), with corresponding standardized effect sizes |effect size| of about 0.01–0.02. All scenario main-effect 95% CIs crossed zero, and all p values were > 0.05. After treating these as a single family of tests and applying Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, none of the scenario main effects reached statistical significance.

For the Group × Scenario interactions, only the interaction in SC3 showed a marginal trend (Group_Adult:Scenario_SC3: Estimate = −0.53, 95% CI [−1.07, 0.02], p ≈ 0.059, effect size ≈ −0.046). All other interaction terms had effect sizes close to zero (|effect size| < 0.03) and p values far above 0.05. The marginal and conditional R2 of the Average walking speed model were 0.993 and 0.997, respectively. The standard deviation of the Subject_ID random intercept was about 0.67, comparable in magnitude to the residual standard deviation (≈0.69). This pattern suggests that there were some stable between-subject differences in overall “preferred walking speed,” but that walking speed remained relatively stable across scenarios and groups, with visual elements exerting only minimal influence on this outcome.

(2) Gait variability

For Gait variability, the baseline mean in the child group was about 0.147 (Estimate = 0.147, 95% CI [0.122, 0.172]). Adults showed a slightly lower value than children in SC0 (Group_Adult: Estimate = −0.021, 95% CI [−0.062, 0.019], p = 0.30), but this difference was not significant and the effect size was essentially zero (≈0.002).

Within the child group, all scenario main effects (Scenario_SC1–SCX) were extremely close to zero (|Estimate| < 0.012). All 95% CIs crossed zero, p values were far above 0.05, and the corresponding standardized effect sizes were very small (|effect size| < 0.002. A similar pattern emerged for the Group × Scenario interactions: all interaction estimates lay within a very narrow range (−0.014 to 0.014), with confidence intervals spanning zero, p values > 0.5, and absolute effect sizes generally < 0.002. In other words, for both children and adults, the impact of the intervention scenarios on gait rhythm was negligible, and multiple-comparison correction does not change this conclusion.

The marginal and conditional R2 for this model were approximately 0.99996 and 0.99998, respectively. The standard deviations of the random intercept and the residuals were both around 0.05, indicating that under the present task demands and spatial scale, Gait variability was extremely stable both within and between individuals. The model was almost entirely explained by “fixed between-subject differences plus small random fluctuations.”

(3) Stopping duration

In contrast to the other two indicators, Stopping duration was highly sensitive to scenario manipulations. Under the baseline condition (child group, SC0), mean stopping time was about 2.26 s (Estimate = 2.26, 95% CI [1.81, 2.71]). In the same baseline scenario, adults showed a slightly longer stopping time than children (Group_Adult: Estimate = 0.21, 95% CI [−0.52, 0.93], p = 0.58), but this difference was not significant, and the effect size was small (≈0.018). Thus, in the absence of visual interventions, children and adults exhibited broadly similar stopping behavior.

Using the child group as the baseline, most intervention scenarios significantly prolonged stopping time:

SC1 (Footprint (stop) markings + Traffic bollard): Estimate = 2.18 s, 95% CI [1.76, 2.60], p ≈ 1.4 × 10−21, effect size ≈ 0.19;

SC2 (Look left markings): Estimate = 1.55 s, 95% CI [1.13, 1.97], p ≈ 2.6 × 10−12, effect size ≈ 0.13;

SC4 (Tactile Paving Patterns): Estimate = 0.72 s, 95% CI [0.30, 1.14], p ≈ 8.7 × 10−4, effect size ≈ 0.06;

SC5 (Stop line): Estimate = 0.49 s, 95% CI [0.07, 0.91], p ≈ 0.021, effect size ≈ 0.04;

SCX (combined intervention): Estimate = 2.64 s, 95% CI [2.22, 3.06], p ≈ 2.3 × 10−29, effect size ≈ 0.23.

For SC1, SC2, SC4, SC5, and SCX, the scenario main effects remained significant after FDR correction across all Scenario-related coefficients, with effect sizes in the small-to-moderate range (≈0.04–0.23). These results indicate that these interventions substantially extend children’s stopping time and strengthen a safer “stop–scan–then cross” behavior pattern.

The Group × Scenario interactions capture group differences in “change relative to SC0.” In SC1, SC2, SC4, and SCX, the Group_Adult:Scenario coefficients were significantly negative. For example:

SC1: Estimate = −1.58 s, 95% CI [−2.25, −0.91], p ≈ 5.1 × 10−6, effect size ≈ −0.14;

SC2: Estimate = −1.26 s, p ≈ 2.6 × 10−4, effect size ≈ −0.11;

SCX: Estimate = −1.80 s, p ≈ 2.2 × 10−7, effect size ≈ −0.16.

These negative interactions indicate that, relative to SC0, the “stopping-time extension effect” of these scenarios was more pronounced in children. Adults also showed some increase in stopping time, but to a clearly smaller degree. In contrast, the interaction terms for SC3 and SC5 were not significant, suggesting that in these two scenarios the relative magnitude of stopping-time extension was more similar between children and adults.

For the Stopping duration model, the marginal and conditional R2 were approximately 0.988 and 0.995, respectively. The standard deviation of the Subject_ID random intercept was about 0.96 s, and the residual standard deviation was about 0.84 s, indicating substantial stable between-subject differences in overall “stopping preference,” while scenario manipulations still accounted for a considerable proportion of the remaining variance.

Taken together, the three behavioral indicators show that Average walking speed and Gait variability were only weakly sensitive to visual elements in the present experimental setting, with very small differences across scenarios. By contrast, Stopping duration was strongly responsive to visual interventions. In particular, scenarios incorporating Footprint (stop) markings, Traffic bollard, Look left markings, and multi-element combinations produced clear, statistically and behaviorally meaningful enhancements in children’s stopping behavior.

4. Discussion

4.1. Multimodal Findings, Hypothesis Testing, and Design Implications

Drawing on questionnaire, eye-tracking, and motion-capture data, this study systematically evaluated how different visual guidance elements influence children’s and adults’ street-crossing behavior, and tested the five predefined hypotheses. A summary is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hypothesis Testing Results Summary Table (5 Hypotheses).

(1) H1: Physical barrier markings significantly enhance children’s stopping awareness before crossing.

This hypothesis was clearly supported under the present test conditions. Questionnaire and motion-capture results converged in showing that Footprint (stop) markings and Traffic bollard significantly increased children’s perceived safety and Stopping behavior. In SC1, SC2, and SCX, children’s Stopping duration was, on average, extended by about 1–2 s relative to SC0, reaching the preset threshold (Δt ≥ 1 s). This indicates that physical barriers and stopping prompts effectively encourage children to stop and scan the environment before stepping into the conflict zone.

Design implication: On streets around schools and along routes with high child pedestrian volumes, continuous Footprint (stop) markings and low-height separator elements should be installed in front of zebra crossings to create a “slow–stop” buffer zone. This configuration can naturally guide children to decelerate, pause, and observe before entering the conflict area.

(2) H2: Visual alert systems more effectively promote children’s left-right scanning behavior during crossing.

This hypothesis was not supported under the present test conditions. Although children reported stronger Left-Right Scanning intentions in SC2 (Look left markings) on the questionnaire, eye-tracking results showed that their Stopping duration proportion within the left/right zebra crossings AOI did not increase markedly compared with SC0 and did not reach the preset +5% threshold. The adult group likewise did not exhibit a stable objective improvement. Thus, text- or symbol-based visual warnings alone had limited impact on actual scanning behavior.

Design implication: Design should rely less on abstract slogans (e.g., “Look left”) and instead favor concrete, action-oriented pictograms, used in combination with physical facilities rather than as the core intervention.

(3) H3: Wayfinding guidance helps children cross more safely and efficiently.

This hypothesis was not supported under the present test conditions. Color-Coded Arrows provided some sense of “guidance” in subjective reports and walking trajectories, but motion-capture data showed that the increase in children’s Average walking speed was only about 0.21 m/s, below the predefined threshold (≥0.25 m/s), indicating limited gains in efficiency. Eye-tracking results further suggested that Color-Coded Arrows substantially focused children’s gaze in some scenarios without correspondingly increasing attention to critical cues such as the direction of oncoming traffic, implying a risk of attention shift.

Design implication: Color-Coded Arrows should not be used as the main means of “speeding up” crossings. The number of colors and contrast levels should be controlled to avoid highly salient graphics directly in the center of the conflict zone. They are better placed along the upstream segments of the school route rather than directly above vehicle–pedestrian conflict points.

(4) H4: Decorative interventions may impair children’s crossing risk appraisal.

This hypothesis was supported under the present test conditions. Decorative pavements such as Tactile Paving Patterns significantly increased the fixation proportion on the Zebra crossings AOI (by about 14%, exceeding the 5% threshold). However, these fixations were concentrated on the patterns themselves rather than on the direction of approaching vehicles or other traffic cues. This suggests that when children remain in such zones, their monitoring of overall traffic risk may be weakened.

Design implication: Decorative patterns should not be placed at the center of high-conflict zones. Their complexity and salience should be reduced, favoring low-contrast, regular geometric patterns or simple color blocks. More decorative elements should be shifted downstream to safer areas such as waiting zones or planting strips, so as not to overconsume children’s visual resources in the conflict area.

(5) H5: Safety boundary markings (stop lines) improve children’s gait stability during crossing.

This hypothesis was not supported under the present test conditions. Questionnaire findings indicated that Stop line increased children’s perceived safety. However, motion-capture results showed that the effects of Scenario_SC1–SCX on gait-variability indicators were near zero (|Estimate| < 0.012), far below the predefined threshold for improved gait stability (≥0.2). On the other hand, eye-tracking analyses suggested that Stop line encouraged pedestrians to shift part of their gaze away from the zebra crossing surface and allocate more attention to the lateral environment and vehicle boundaries. Overall, Stop line appears to function more as an “attention-allocation” tool than as a device that directly improves gait; its primary value lies in expanding the visual monitoring field and reinforcing perception of safety boundaries.

Design implication: In practice, Stop line should be combined with Footprint (stop) markings and separator elements to form a continuous “stop–look–walk” guidance sequence, rather than being treated as a standalone measure for improving gait stability.

Building on the above hypothesis testing, this study further proposes a zoned and tiered visual guidance framework. The street-crossing space is divided into four continuous segments—the approach zone, buffer zone, decision zone, and crossing zone—and each zone is equipped with corresponding visual elements to hierarchically integrate behavioral demands such as “slow–stop–scan–cross.” As illustrated in Figure 12, this framework uses layered information presentation to align with children’s cognitive development and the continuous safety requirements of the crossing process, providing a systematic design approach for child-friendly crossing environments.

Figure 12.

Conventional Zebra Crossing (left) vs. Combined Pattern Diagram Based on Validation Results (right).

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Behavioral Differences Between Children and Adults

Multimodal analyses revealed systematic differences between children and adults in visual attention, behavioral execution, and risk perception. Eye-tracking data showed that children’s fixations were more concentrated near the center of the roadway, with insufficient scanning toward the direction of oncoming traffic. This pattern is consistent with previous findings that children’s visual field is more centrally biased, whereas adults adopt a broader search strategy [47]. The present study also provides the first quantitative estimate of left–right scanning: on average, children devoted only 26.4% of their fixation time to the two lateral regions, significantly lower than the 45.8% observed in adults.

Questionnaire and behavioral data further indicated that children were more sensitive to visual cues. Younger children were more easily distracted by Tactile Paving Patterns, suggesting that their perceptual control mechanisms are still developing and supporting earlier evidence that older children display safer traffic behavior [6,9,48]. Some adults, by contrast, showed stronger exploratory and sensation-seeking tendencies in the Tactile Paving Patterns scenario, a pattern that aligns with previous findings that young adults exhibit higher levels of sensation seeking [11].

4.3. Literature Validation and Theoretical Supplementation

This study both empirically examined the applicability of existing theories and, from a mechanistic perspective, supplemented and revised several key viewpoints, thereby extending the theoretical boundaries of research on children’s traffic safety behavior to some extent.

(1) Consistency with existing evidence

We found that the SC1 scenario (the combination of Footprint (stop) markings and Traffic bollard) significantly enhanced children’s stopping and observation awareness before crossing. This result is highly consistent with the findings of [34] on the effectiveness of Footprint markings and bollards, and aligns with evidence from [49,50] that physical interventions exert a positive guiding effect on children’s traffic behavior. Together, these results further confirm that placing clear, concrete physical prompts in front of key conflict zones helps strengthen children’s safety-related decision-making.

(2) Extension of prior work

Previous studies [39,40] have mainly adopted a driver-centered perspective, focusing on how colored pavements influence vehicle speed and yielding behavior and generally concluding that “color enhancement supports speed-reduction awareness.” By contrast, the present study, for the first time, examined this issue from the viewpoint of pedestrians—particularly child pedestrians—and found that complex Tactile Paving Patterns, while strongly attention-grabbing, may simultaneously weaken children’s perception of overall traffic risk, thereby increasing crossing risk under certain conditions. This finding not only enriches our understanding of the “double-edged” nature of Tactile Paving Patterns, but also refines the intuitive assumption that “more color automatically translates into higher safety.” At the same time, compared with the conclusion of [24] that Stop line positively guides drivers’ yielding behavior, our pedestrian-side analysis shows that Stop line does not directly improve children’s gait stability, but does have potential value at the levels of visual cognition and psychological cueing by reinforcing visual boundaries and encouraging children to modestly expand their field of observation.

(3) Novel contributions

Our findings further indicate that Color-Coded Arrows zebra crossings, which are widely used in real-world environments, have clear limitations in effectiveness for children. They did not significantly enhance children’s awareness of “safe and efficient crossing”; instead, their strong color stimulation intensified attention to the zebra crossing surface itself and interfered with the processing and judgment of surrounding risk cues. This result raises an important caution for current “child-friendly” design practices that favor highly saturated and overly colorized treatments. In addition, the study found that semantic text prompts such as Look left markings had only limited objective benefits for left–right observation behavior in both children and adults, again suggesting that children in crossing situations rely more heavily on intuitive cues such as concrete, pictorial, and character-based graphics. Accordingly, the design of visual guidance systems for children should shift from “text reminders” to “pictorial guidance,” so that the mode of expression is better aligned with children’s cognitive characteristics and information-processing patterns.

5. Conclusions

Using three experimental modalities—questionnaire surveys, eye tracking, and motion capture—this study systematically evaluated the intervention effects of typical visual guidance elements on children’s street-crossing behavior across seven VR street-crossing scenarios. The results show that Footprint (stop) markings and Traffic bollard significantly increased children’s likelihood of stopping and their stopping duration, demonstrating a clear behavioral guidance effect. Look left markings produced only limited objective improvements in observation behavior for both children and adults. Complex Tactile Paving Patterns and Color-Coded Arrows attracted attention but may weaken children’s appraisal of street-crossing risk. Stop line showed some potential for dispersing gaze and enhancing perception of environmental information, but no significant improvement in gait stability was observed in this study.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively modest (59 participants in total, including 36 children), and all participants were recruited from a single city and cultural context. This constrains the external validity of the findings and their generalizability across settings. Second, although the VR experiment offered high experimental control and reproducibility, it did not incorporate key contextual elements such as dynamic traffic flow, urban noise, and driver–pedestrian interactions. As a result, the combined influence of multisource information and risk cues in real traffic environments could not be fully reproduced, and causal inferences about real-world risk should be made with caution.

Future research could further enhance the ecological validity of VR scenarios by incorporating dynamic traffic, ambient noise, and driver behavior into the platform. Larger and more diverse samples, including children from different regions and cultural backgrounds, are also needed. In addition, combining VR-based experiments with naturalistic street observations and physical pilot interventions would allow cross-validation of the present findings. Integrating laboratory and field evidence may ultimately support the development of more generalizable principles for visual guidance design.

Overall, this study refines intuitive understandings of “child-friendly” facilities and reveals potential mismatches between the perceived effectiveness of some commonly used visual elements and children’s actual cognitive processing. It provides quantitative evidence and preliminary design recommendations for optimizing visual guidance systems on urban streets. With further validation and extension, these findings may offer methodological and empirical support for translating the concept of child-friendly traffic environments into practical design and policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.P. and S.H.; methodology, S.H. and Q.J.; software, X.Z.; validation, W.P., X.Z. and B.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, W.P.; resources, B.Z.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.P. and X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., B.Z., and S.H.; visualization, W.P. and X.Z.; supervision, Q.J. and S.H.; project administration, B.Z. and S.H.; funding acquisition, W.P. and Q.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Innovation Program of China Architecture Design & Research Group, grant number 1100C080240215: “Research on Child-Friendly Spatial Design Methods and Key Technologies Supported by Multi-Source Data—Taking the Zhongguancun Urban Renewal Projects as a Case Study,” and the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2022YFC3800300, sub-project number 2022YFC3800304: “Integrated Research on Full-Cycle Design Methods and Technologies for Urban Renewal Projects.”

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture (Approval Number: BUCEA202215013).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all participants (and their legal guardians for child participants) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results of this study can be found in the publicly available dataset on Mendeley Data, under the following DOI: https://doi.org/10.17632/cb2vk768w2.1 [51].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the children and their parents who participated in this study for their kind assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Linear mixed-effects model results for gaze proportion on the Zebra crossings AOI.

Table A1.

Linear mixed-effects model results for gaze proportion on the Zebra crossings AOI.

| Name | Estimate | SE | tStat | DF | p-Value | Lower | Upper | Effect Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.49 | 0.032 | 15.338 | 343 | <0.001 | 0.428 | 0.553 | 0.042 |

| Group_Adult | −0.171 | 0.052 | −3.269 | 343 | 0.001 | −0.274 | −0.068 | −0.015 |

| Scenario_SC1 | 0.058 | 0.03 | 1.915 | 343 | 0.056 | −0.002 | 0.118 | 0.005 |

| Scenario_SC2 | 0.043 | 0.03 | 1.409 | 343 | 0.16 | −0.017 | 0.102 | 0.004 |

| Scenario_SC3 | 0.119 | 0.03 | 3.918 | 343 | <0.001 | 0.059 | 0.179 | 0.01 |

| Scenario_SC4 | 0.145 | 0.03 | 4.786 | 343 | <0.001 | 0.086 | 0.205 | 0.013 |

| Scenario_SC5 | −0.025 | 0.03 | −0.837 | 343 | 0.403 | −0.085 | 0.034 | −0.002 |

| Scenario_SCX | 0.128 | 0.03 | 4.227 | 343 | <0.001 | 0.069 | 0.188 | 0.011 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC1 | −0.067 | 0.05 | −1.35 | 343 | 0.178 | −0.165 | 0.031 | −0.006 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC2 | −0.033 | 0.05 | −0.662 | 343 | 0.508 | −0.131 | 0.065 | −0.003 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC3 | −0.076 | 0.05 | −1.534 | 343 | 0.126 | −0.174 | 0.022 | −0.007 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC4 | 0.033 | 0.05 | 0.664 | 343 | 0.507 | −0.065 | 0.131 | 0.003 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC5 | −0.019 | 0.05 | −0.382 | 343 | 0.703 | −0.117 | 0.079 | −0.002 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SCX | −0.024 | 0.05 | −0.483 | 343 | 0.63 | −0.122 | 0.074 | −0.002 |

Random effects variance (random intercept for Subject_ID): 134.5832; Marginal R2: 0.99976; Conditional R2: 0.9999.

Table A2.

Linear mixed-effects model results for gaze proportion on the Left/right zebra crossings AOI.

Table A2.

Linear mixed-effects model results for gaze proportion on the Left/right zebra crossings AOI.

| Name | Estimate | SE | tStat | DF | p-Value | Lower | Upper | Effect Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.923 | 343 | 0.356 | −0.009 | 0.025 | 0.001 |

| Group_Adult | 0.083 | 0.014 | 5.724 | 343 | <0.001 | 0.054 | 0.111 | 0.007 |

| Scenario_SC1 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.268 | 343 | 0.789 | −0.017 | 0.022 | 0 |

| Scenario_SC2 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.025 | 343 | 0.98 | −0.02 | 0.019 | 0 |

| Scenario_SC3 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.146 | 343 | 0.884 | −0.018 | 0.021 | 0 |

| Scenario_SC4 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.053 | 343 | 0.958 | −0.019 | 0.02 | 0 |

| Scenario_SC5 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.466 | 343 | 0.641 | −0.015 | 0.024 | 0 |

| Scenario_SCX | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.203 | 343 | 0.839 | −0.018 | 0.022 | 0 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC1 | −0.033 | 0.016 | −2.044 | 343 | 0.042 | −0.065 | −0.001 | −0.003 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC2 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.809 | 343 | 0.419 | −0.019 | 0.045 | 0.001 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC3 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.448 | 343 | 0.654 | −0.025 | 0.039 | 0.001 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC4 | −0.026 | 0.016 | −1.607 | 343 | 0.109 | −0.058 | 0.006 | −0.002 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC5 | 0.044 | 0.016 | 2.701 | 343 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.076 | 0.004 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SCX | 0.003 | 0.016 | 0.18 | 343 | 0.857 | −0.029 | 0.035 | 0 |

Random effects variance (random intercept for Subject_ID): 134.5832; Marginal R2: 0.99998; Conditional R2: 0.99999.

Table A3.

Linear mixed-effects model results for Average walking speed.

Table A3.

Linear mixed-effects model results for Average walking speed.

| Name | Estimate | SE | tStat | DF | p-Value | Lower | Upper | Effect Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.877 | 0.168 | 17.165 | 357 | <0.001 | 2.547 | 3.206 | 0.248 |

| Group_Adult | −0.311 | 0.273 | −1.141 | 357 | 0.255 | −0.848 | 0.225 | −0.027 |

| Scenario_SC1 | −0.165 | 0.171 | −0.966 | 357 | 0.334 | −0.502 | 0.171 | −0.014 |

| Scenario_SC2 | 0.124 | 0.171 | 0.727 | 357 | 0.468 | −0.212 | 0.461 | 0.011 |

| Scenario_SC3 | 0.209 | 0.171 | 1.225 | 357 | 0.221 | −0.127 | 0.546 | 0.018 |

| Scenario_SC4 | −0.105 | 0.171 | −0.617 | 357 | 0.538 | −0.442 | 0.231 | −0.009 |

| Scenario_SC5 | 0.011 | 0.171 | 0.062 | 357 | 0.95 | −0.326 | 0.347 | 0.001 |

| Scenario_SCX | 0.052 | 0.171 | 0.303 | 357 | 0.762 | −0.285 | 0.388 | 0.004 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC1 | 0.108 | 0.278 | 0.388 | 357 | 0.698 | −0.439 | 0.656 | 0.009 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC2 | 0.035 | 0.278 | 0.125 | 357 | 0.901 | −0.513 | 0.582 | 0.003 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC3 | −0.527 | 0.278 | −1.894 | 357 | 0.059 | −1.075 | 0.02 | −0.045 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC4 | −0.116 | 0.278 | −0.417 | 357 | 0.677 | −0.664 | 0.431 | −0.01 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC5 | −0.364 | 0.278 | −1.307 | 357 | 0.192 | −0.911 | 0.184 | −0.031 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SCX | −0.081 | 0.278 | −0.291 | 357 | 0.771 | −0.629 | 0.466 | −0.007 |

Random effects variance (random intercept for Subject_ID): 134.5832; Marginal R2: 0.99312; Conditional R2: 0.99686.

Table A4.

Linear mixed-effects model results for Gait variability.

Table A4.

Linear mixed-effects model results for Gait variability.

| Name | Estimate | SE | tStat | DF | p-Value | Lower | Upper | Effect Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.147 | 0.013 | 11.659 | 357 | <0.001 | 0.122 | 0.172 | 0.013 |

| Group_Adult | −0.021 | 0.021 | −1.044 | 357 | 0.297 | −0.062 | 0.019 | −0.002 |

| Scenario_SC1 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.166 | 357 | 0.868 | −0.023 | 0.027 | 0 |

| Scenario_SC2 | 0.01 | 0.013 | 0.82 | 357 | 0.413 | −0.014 | 0.035 | 0.001 |

| Scenario_SC3 | −0.012 | 0.013 | −0.96 | 357 | 0.338 | −0.037 | 0.013 | −0.001 |

| Scenario_SC4 | −0.003 | 0.013 | −0.232 | 357 | 0.817 | −0.028 | 0.022 | 0 |

| Scenario_SC5 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.085 | 357 | 0.932 | −0.024 | 0.026 | 0 |

| Scenario_SCX | −0.005 | 0.013 | −0.391 | 357 | 0.696 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC1 | −0.008 | 0.02 | −0.391 | 357 | 0.696 | −0.048 | 0.032 | −0.001 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC2 | 0.012 | 0.02 | 0.562 | 357 | 0.575 | −0.029 | 0.052 | 0.001 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC3 | 0.008 | 0.02 | 0.376 | 357 | 0.707 | −0.033 | 0.048 | 0.001 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC4 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.041 | 357 | 0.967 | −0.039 | 0.041 | 0 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC5 | −0.006 | 0.02 | −0.315 | 357 | 0.753 | −0.047 | 0.034 | −0.001 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SCX | 0.014 | 0.02 | 0.672 | 357 | 0.502 | −0.026 | 0.054 | 0.001 |

Random effects variance (random intercept for Subject_ID): 134.5832; Marginal R2: 0.99996; Conditional R2: 0.99998.

Table A5.

Linear mixed-effects model results for Stopping duration.

Table A5.

Linear mixed-effects model results for Stopping duration.

| Name | Estimate | SE | tStat | DF | p-Value | Lower | Upper | Effect Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.264 | 0.229 | 9.87 | 343 | <0.001 | 1.813 | 2.715 | 0.195 |

| Group_Adult | 0.205 | 0.366 | 0.56 | 343 | 0.576 | −0.515 | 0.925 | 0.018 |

| Scenario_SC1 | 2.182 | 0.213 | 10.222 | 343 | <0.001 | 1.762 | 2.602 | 0.188 |

| Scenario_SC2 | 1.549 | 0.213 | 7.26 | 343 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.969 | 0.134 |

| Scenario_SC3 | 0.324 | 0.213 | 1.516 | 343 | 0.13 | −0.096 | 0.743 | 0.028 |

| Scenario_SC4 | 0.717 | 0.213 | 3.358 | 343 | 0.001 | 0.297 | 1.137 | 0.062 |

| Scenario_SC5 | 0.495 | 0.213 | 2.318 | 343 | 0.021 | 0.075 | 0.914 | 0.043 |

| Scenario_SCX | 2.642 | 0.213 | 12.381 | 343 | <0.001 | 2.223 | 3.062 | 0.228 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC1 | −1.579 | 0.341 | −4.634 | 343 | <0.001 | −2.25 | −0.909 | −0.136 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC2 | −1.259 | 0.341 | −3.695 | 343 | <0.001 | −1.93 | −0.589 | −0.109 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC3 | −0.237 | 0.341 | −0.697 | 343 | 0.487 | −0.908 | 0.433 | −0.02 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC4 | −0.849 | 0.341 | −2.49 | 343 | 0.013 | −1.519 | −0.178 | −0.073 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SC5 | −0.483 | 0.341 | −1.418 | 343 | 0.157 | −1.154 | 0.187 | −0.042 |

| Group_Adult:Scenario_SCX | −1.803 | 0.341 | −5.29 | 343 | <0.001 | −2.473 | −1.133 | −0.155 |

Random effects variance (random intercept for Subject_ID): 134.5832; Marginal R2: 0.9879; R2: 0.99544.

References

- WHO. World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Public Security Traffic Management Bureau. Annual Report on Traffic Safety; Public Security Bureau: Beijing, China, 2023.

- UNICEF. The Child Friendly Cities Initiative. Available online: https://www.childfriendlycities.org/reports/child-friendly-cities-initiative (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- National Development and Reform Commission Office; The State Council Working Committee on Women and Children Affairs Office; Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development Office. Notice on the Issuance of Experience and Measures for the Construction of Child-Friendly Cities (Document No. FBGY [2025] 209); The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2025. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/202503/t20250321_1396752.html (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Tabibi, Z.; Pfeffer, K. Choosing a safe place to cross the road: The relationship between attention and identification of safe and dangerous road-crossing sites. Child Care Health Dev. 2003, 29, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meir, A.; Oron-Gilad, T.; Parmet, Y. Are child-pedestrians able to identify hazardous traffic situations? Measuring their abilities in a virtual reality environment. Saf. Sci. 2015, 80, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Sagberg, F.; Torquato, R. Traffic hazard perception among children. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2014, 26, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Sze, N.N.; Yu, Z.; Cui, J. Exploring the crossing behaviours and visual attention allocation of children in primary school in an outdoor road environment. Cogn. Technol. Work 2021, 23, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapiro, H.; Oron-Gilad, T.; Parmet, Y. The effect of environmental distractions on child pedestrian’s crossing behavior. Saf. Sci. 2018, 106, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M.; McGuckian, T.B.; Healy, N.; Lam, N.; Lucas, R.; Palmer, K.; Crowther, R.G.; Greene, D.A.; Wilson, P.; Duckworth, J. Development of a virtual reality pedestrian street-crossing task: The examination of hazard perception and gap acceptance. Saf. Sci. 2025, 181, 106706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, A.; Su, F.; Schwebel, D.C. The effect of age and sensation seeking on pedestrian crossing safety in a virtual reality street. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 88, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biassoni, F.; Bina, M.; Confalonieri, F.; Ciceri, R. Visual exploration of pedestrian crossings by adults and children: Comparison of strategies. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 56, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, N.C.; Rokade, S.; Bivina, G.R. Towards safer streets: A review of child pedestrian behavior and safety worldwide. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 103, 638–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, D.A.; Cardona, S.; Hernández-Pulgarín, G. Risky pedestrian behaviour and its relationship with road infrastructure and age group: An observational analysis. Saf. Sci. 2021, 143, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deluka-Tibljaš, A.; Šurdonja, S.; Otković, I.I.; Campisi, T. Child-pedestrian traffic safety at crosswalks—Literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Yang, T.; Kwon, S.; Zuo, M.; Li, W.; Choi, I. Using virtual reality to identify and modify risky pedestrian behaviors amongst Chinese children. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2020, 21, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D. The development of conscious control in childhood. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004, 8, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horswill, M.S.; Waylen, A.E.; Tofield, M.I. Drivers’ Ratings of Different Components of Their Own Driving Skill: A Greater Illusion of Superiority for Skills That Relate to Accident Involvement 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, A.; Novačko, L.; Babojelić, K.; Kožul, N. Analysis of child traffic safety near primary school areas using UAV technology. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountas, G.; Olowosegun, A.; Basbas, S. Assessing school travel safety in Scotland: An empirical analysis of injury severities for accidents in the school commute. Safety 2022, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelman, V.; Levi, S.; Carmel, R.; Korchatov, A.; Hakkert, S. Exploring patterns of child pedestrian behaviors at urban intersections. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 122, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Ling, F.; Feng, Z.; Ma, C.; Kumfer, W.; Shao, C.; Wang, K. Effects of mobile phone distraction on pedestrians’ crossing behavior and visual attention allocation at a signalized intersection: An outdoor experimental study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 115, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, J.B.; Schwebel, D.C. Supervision of young children in parking lots: Impact on child pedestrian safety. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 70, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechteep, P.; Luathep, P.; Jaensirisak, S.; Kronprasert, N. Analysis of factors influencing driver yielding behavior at midblock crosswalks on urban arterial roads in Thailand. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergan, S.; Zou, Z.; Bernardes, S.D.; Zuo, F.; Ozbay, K. Developing an integrated platform to enable hardware-in-the-loop for synchronous VR, traffic simulation and sensor interactions. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassa, A.; Orsini, F.; Gastaldi, M.; Rossi, R. Teaching children to cross safely: A full-immersive virtual reality training method for young pedestrians. Saf. Sci. 2025, 187, 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, I.; Cuenen, A.; Wets, G.; Paul, R.; Janssens, D. Advancing Online Road Safety Education: A Gamified Approach for Secondary School Students in Belgium. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]