Abstract

Generating realistic synthetic gene expression data that captures the complex interdependencies and biological context of cellular systems remains a significant challenge. Existing methods often struggle to reproduce intricate co-expression patterns and incorporate prior biological knowledge effectively. To address these limitations, we propose BioGen-KI, a novel bio-inspired generative network with knowledge integration. Our framework leverages a hybrid deep learning architecture that integrates embeddings learned from biological knowledge graphs (e.g., gene regulatory networks, pathway databases) with a conditional generative adversarial network (cGAN). The knowledge graph embeddings guide the generator to produce synthetic expression profiles that respect known biological relationships, while conditioning on contextual information (e.g., cell type, experimental condition) allows for targeted data synthesis. Furthermore, we introduce a biologically informed discriminator that evaluates not only the statistical realism but also the biological plausibility of the generated data, encouraging the preservation of pathway coherence and relevant gene interactions. We demonstrate the efficacy of BioGen-KI by generating synthetic gene expression datasets that exhibit improved statistical similarity to real data and, critically, better preservation of biologically meaningful relationships compared to baseline GAN models and methods relying solely on statistical characteristics. Evaluation on downstream tasks, such as clustering and differential gene expression analysis, highlights the utility of BioGen-KI-generated data for enhancing the robustness and interpretability of biological data analysis. This work presents a significant step towards generating more biologically faithful synthetic gene expression data for research and development.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of high-throughput sequencing technologies, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) [1], has resulted in an unprecedented deluge of omics data [2], spanning genomics [3], transcriptomics [4], proteomics [5], and epigenomics [6]. These datasets provide invaluable opportunities to study complex cellular systems [7], unravel disease mechanisms [8], and enable the development of precision medicine [9]. For example, transcriptome profiling has become a cornerstone for investigating cell differentiation, tumor heterogeneity, and drug response [10,11]. Despite these advances, a fundamental challenge persists: the scarcity and fragmentation of high-quality biological datasets [12].

Generating comprehensive datasets remains prohibitively expensive and logistically complex, particularly for rare diseases, longitudinal studies, and population-scale analyses [13,14]. Moreover, data acquisition is often constrained by ethical considerations, patient availability, and technical variability [15,16]. This scarcity hinders the application of deep learning models, which typically demand vast amounts of training data to learn generalizable patterns [17]. As a result, computational biologists are increasingly exploring synthetic data generation as a means of data augmentation to overcome these limitations [18].

Generative models, particularly Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [19], have emerged as powerful frameworks for learning data distributions and producing synthetic samples. They have revolutionized fields such as computer vision, natural language processing, and speech synthesis by generating highly realistic outputs [20,21,22]. In the context of biology, GANs hold the promise of creating synthetic gene expression profiles that resemble real data while preserving privacy and mitigating the risks of data sharing [23,24]. Such synthetic datasets could support predictive model training, enhance reproducibility, and accelerate the development of in-silico experiments and drug discovery pipelines [25]. However, applying GANs directly to biological data introduces unique challenges [26]. Unlike images, where local pixel relationships dominate, gene expression data is governed by high-dimensional, non-linear, and biologically constrained networks of interactions [26,27]. Genes do not act in isolation but are regulated through transcription factors, feedback loops, and pathway-level interactions [28]. Conventional GANs, which are agnostic to biological knowledge, often generate data that matches statistical properties yet violates fundamental biological principles. For example, a naïve GAN might reproduce expression distributions but fail to enforce the inverse regulation between key transcription factor–target pairs, leading to biologically implausible synthetic samples [29]. Such inconsistencies limit the downstream utility of synthetic data for tasks such as differential expression analysis, pathway enrichment, and biomarker discovery [30,31].

To address these limitations, recent research has emphasized knowledge-guided machine learning, where prior biological information is integrated into data-driven models [32,33]. Knowledge graphs (KG), which encode structured relationships among genes, proteins, and pathways, offer a rich source of contextual information that can guide generative models towards biologically coherent outputs [34,35]. By embedding this structured knowledge into the generative process, it becomes possible to constrain synthetic data to respect known regulatory interactions, co-expression modules, and pathway activities [36]. In this work, we introduce BioGen-KI (Bio-Inspired Generative Network with Knowledge Integration), a novel framework that unites the strengths of GANs with structured biological priors. BioGen-KI leverages embeddings learned from biological knowledge graphs in combination with conditional generative adversarial training to generate synthetic gene expression data that is both statistically faithful and biologically plausible. Unlike previous approaches, which rely solely on data-driven distribution matching, BioGen-KI explicitly penalizes violations of co-expression consistency and pathway coherence. We hypothesize that this biologically informed design enables BioGen-KI to outperform conventional generative models in generating synthetic datasets suitable for downstream applications, ranging from classification and clustering to biomarker discovery and hypothesis generation.

Through extensive evaluation on multiple transcriptomic datasets, including bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq, and cancer genomics, we demonstrate that BioGen-KI achieves superior statistical fidelity, preserves biologically meaningful interactions, and enhances the performance of downstream machine learning tasks. Our results highlight the potential of knowledge-guided generative modeling to address the challenges of data scarcity in computational biology and lay the foundation for scalable, privacy-preserving, and biologically coherent synthetic data generation. To improve clarity, the remainder of this manuscript briefly outlines the relevant literature, presents the BioGen-KI framework, and reports its empirical evaluation across multiple transcriptomic datasets. We then discuss the implications and limitations of the proposed method before concluding with final remarks.

2. Related Works

The generation of synthetic data, particularly for complex biological domains, has been a significant area of research across multiple disciplines. In this section, we review relevant works along three dimensions: generative modeling in computational biology, integration of domain knowledge into deep learning, and existing strategies for synthetic data generation in genomics.

2.1. Generative Models in Computational Biology

Deep generative models have increasingly been applied to biological data, offering powerful tools for capturing complex distributions and generating synthetic samples [37]. Early approaches favored Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [38], which learn structured latent spaces useful for dimensionality reduction and data denoising. For instance, scVI [39] and trVAE [40] successfully leveraged VAEs to remove batch effects and enhance single-cell RNA-seq data integration. These methods demonstrated that probabilistic latent-variable models can provide interpretable embeddings while generating realistic biological data.

GANs brought a new paradigm, focusing on adversarial learning between generator and discriminator networks to produce highly realistic synthetic samples. In bioinformatics, GANs have been applied to tasks such as cell-type expression generation [41], drug response modeling, and proteomics data simulation. While GAN-based models often improve statistical fidelity over VAEs, numerous studies have shown that they struggle to preserve mechanistic biological structure. Specifically, GANs frequently fail to maintain gene regulatory interactions, transcription factor–target dependencies, and coherent co-expression modules [26,27,29]. These limitations arise because most GAN frameworks treat genes as independent features, without incorporating regulatory networks or pathway constraints. This gap has been increasingly recognized in the literature, motivating the development of models that integrate biological priors or network information to enhance biological plausibility [28,32]. Our work builds upon this direction by explicitly incorporating structured biological knowledge into the generative process to improve both statistical realism and mechanistic fidelity.

2.2. Knowledge-Guided Deep Learning

A parallel research trajectory emphasizes the incorporation of external domain knowledge into machine learning models to improve interpretability and robustness. In biology, this knowledge is abundant and structured in resources like Gene Ontology (GO) [42], KEGG pathways [43], Reactome [44], and protein–protein interaction networks (e.g., STRINGdb [45]). Leveraging these sources, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [46] have been widely adopted to learn embeddings of biological networks. Classical approaches such as DeepWalk [47] and GraphSAGE [48] provided foundational techniques for generating network-based embeddings, while later works adapted them for modeling gene regulation and signaling networks.

A related and increasingly influential family of knowledge-integrative methods is the Grouping–Scoring–Modeling (G-S-M) framework, recently formalized by Yousef et al [49]. G-S-M methods group features using prior biological knowledge (e.g., pathways, GO terms, miRNA–gene interactions, disease–gene associations), score these groups based on their relationship to the phenotype, and then build predictive models using the most informative groups. Several recent applications demonstrate the flexibility of this paradigm across different omics modalities. GediNET [50] integrates DisGeNET disease–gene relationships to identify disease–disease associations; miRGediNET [51] combines miRTarBase, DisGeNET, and HMDD to study miRNA gene–disease triads; 3Mint [52] extends G-S-M to multi-omics (mRNA, miRNA, methylation); PriPath [53] and GeNetOntology [54] incorporate KEGG pathways or GO terms to identify dysregulated processes; and miRdisNET [55] applies G-S-M for miRNA–disease prediction. Similar ideas underpin earlier tools such as miRcorrNet [56], maTE [57], and the more recent microBiomeGSM [58]. These studies collectively demonstrate that structured biological knowledge can effectively guide feature grouping, relevance scoring, and downstream modeling. While G-S-M methods are knowledge-driven, they are fundamentally designed for supervised prediction or feature prioritization, not for generative modeling. In contrast, BioGen-KI aims to synthesize realistic gene expression profiles by integrating knowledge-graph embeddings directly into adversarial training, and by enforcing biological coherence through co-expression and pathway-level constraints. Thus, G-S-M represents a complementary family of knowledge-guided learning strategies, whereas BioGen-KI focuses on knowledge-aware data generation, a problem not addressed by existing G-S-M tools.

Several studies outside of biology illustrate the power of knowledge-guided generative modeling. For example, in materials science, the Knowledge-Guided Machine Learning (KGML) [32] demonstrated that embedding physical constraints into generative processes improves the quality of synthesized materials [59]. Similarly, in healthcare, knowledge graph embeddings have been integrated into clinical predictive models to encode comorbidities and treatment histories [60]. These efforts highlight that structured knowledge can serve as a regularizer, ensuring that models respect domain-specific constraints. In the context of genomics, however, such integration remains limited, providing an opportunity for frameworks like BioGen-KI, which directly embed gene–gene relationships and pathway-level constraints into generative modeling.

2.3. Synthetic Data Generation in Genomics

Before the emergence of deep learning, synthetic gene expression data was primarily produced using statistical models, such as multivariate Gaussian distributions or copula-based methods [61], which rely on predefined assumptions about covariance structures. While interpretable and computationally efficient, these approaches fail to capture the non-linear and high-dimensional dependencies present in real biological systems.

In addition to these statistical models, numerous dedicated software tools have been developed to simulate RNA-seq data. Tools such as Splatter [62], Polyester [63], SymSim [64], SERGIO [65], and scDesign2 [66] generate bulk or single-cell expression profiles by modeling gene-level distributions, co-expression patterns, transcriptional bursting, and technical noise. These simulators provide valuable benchmarks for method development by attempting to reproduce genetic variation, differential expression, and cell-type heterogeneity.

However, despite their utility, these tools share several important limitations. Many rely on simplified parametric assumptions (e.g., negative binomial distributions) that do not fully capture the biological complexity of gene regulatory interactions or pathway-level dependencies. Tools that incorporate gene regulatory networks, such as SERGIO, still struggle to reproduce higher-order, context-dependent relationships, particularly in cancer genomics where regulatory programs are highly rewired. Furthermore, most simulators must be extensively reparameterized to adapt to different data types (bulk vs. single-cell), sequencing technologies, or disease-specific transcriptional programs. As a result, the synthetic data they produce may match statistical properties yet fail to preserve mechanistic biological logic, limiting their applicability to tasks such as biomarker discovery or regulatory network inference.

Recent years have witnessed the adoption of deep generative models for genomics. ExpressionGAN [67] was among the first GAN-based frameworks tailored for transcriptomic data, showing that adversarial training could produce expression profiles resembling real data. Extensions such as Conditional GANs (cGANs) [68] and Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) [69] further improved stability and statistical realism, though they still operated without explicit biological guidance. On the other hand, conditional VAEs have been adapted for multi-condition gene expression generation, supporting applications such as perturbation prediction [70]. Despite these advancements, most models remain purely data-driven, making them vulnerable to producing biologically implausible results.

More recently, diffusion models [71] have demonstrated strong generative performance in transcriptomics and other genomics-related settings, offering improved stability and sample quality over adversarial models. These approaches represent a promising direction for synthesizing biologically faithful gene expression profiles, although they still lack explicit integration of biological regulatory knowledge.

Overall, while existing simulation tools and deep generative models contribute valuable capabilities, they either depend heavily on statistical assumptions or fail to incorporate biological constraints, highlighting the need for frameworks, such as BioGen-KI, that combine generative modeling with structured biological knowledge. In particular, ExpressionGAN [67] demonstrates that adversarial training can produce realistic transcriptomic profiles, but it remains fully data-driven: it does not use knowledge-graph structure, does not impose co-expression or pathway-level biological losses, and does not provide an explicitly biological discriminator signal.

Similarly, knowledge-guided machine learning frameworks such as KGML in materials science [32,59] and clinical KG-based predictors [60] show that embedding structured priors (e.g., physical laws or medical ontologies) can improve predictive performance and robustness, but these approaches are primarily discriminative, not generative, and they do not focus on conditional synthesis of gene expression profiles. By contrast, BioGen-KI jointly (i) integrates biological knowledge-graph embeddings into both the generator and the discriminator, (ii) optimizes a combined adversarial and biologically informed objective (co-expression and pathway activity consistency), and (iii) supports conditional control over biological context (cell type, condition, or cancer subtype) within a single unified framework. These design choices position BioGen-KI as a knowledge-aware generative model tailored specifically to synthetic omics data, rather than a direct extension of existing KG-enhanced predictors or purely data-driven generative models.

3. BioGen-KI Framework

The proposed BioGen-KI is a biologically guided deep generative framework designed to produce statistically realistic and mechanistically consistent synthetic gene expression data. Unlike conventional GANs that rely purely on distribution matching, BioGen-KI incorporates structured biological knowledge into the generative process, ensuring that the synthesized profiles respect known gene–gene interactions, regulatory hierarchies, and pathway-level dependencies. This section details the architecture, training objectives, and biological integration mechanisms of BioGen-KI.

3.1. Design Overview

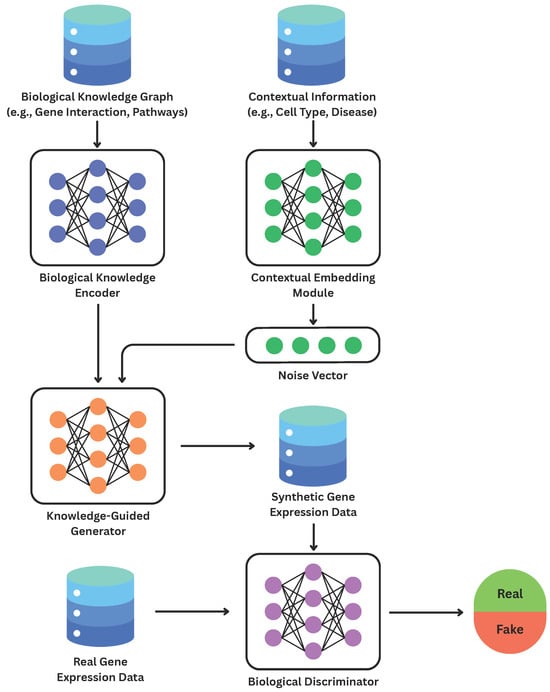

BioGen-KI combines the adversarial learning principles of cGANs with graph-based biological embeddings and biologically informed loss functions. Its architecture consists of four interacting modules (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Overview of the BioGen-KI framework. Biological knowledge and contextual embeddings jointly guide the generator and discriminator toward biologically coherent synthetic expression data.

- (i)

- a Biological Knowledge Encoder that transforms heterogeneous molecular interactions from curated databases into dense vector representations;

- (ii)

- a Contextual Embedding Module that captures experimental or biological conditions such as cell type, treatment, or disease state;

- (iii)

- a Knowledge-Guided Generator that integrates random noise with knowledge-graph and contextual embeddings to synthesize biologically constrained gene-expression profiles; and

- (iv)

- a Biological Discriminator that distinguishes real from synthetic samples while explicitly evaluating biological plausibility.

Together, these modules form a dual-objective system: adversarial optimization enforces statistical realism, whereas biologically motivated constraints maintain mechanistic integrity. Figure 1 illustrates the overall computational pipeline.

3.2. Biological Knowledge Encoder

To encode structured domain knowledge, we represent biological systems as a heterogeneous graph , where V is the set of entities (genes, proteins, or pathways) and E is the set of relationships (activation, inhibition, membership, or physical interaction). The adjacency matrix encodes edge connections, augmented with self-loops () and normalized via to preserve numerical stability.

A two-layer Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) learns embeddings for each gene node:

where represents initial node features (one-hot encodings or biological descriptors), are learnable weights, and denotes a non-linear activation (ReLU). After L layers, the final matrix captures both local and global graph context, embedding each gene in a biologically meaningful vector space. These embeddings encode relationships such as co-regulation or shared pathway membership and serve as a structural prior for the generator and discriminator.

3.3. Contextual Embedding Module

The generation of condition-specific synthetic profiles requires awareness of the biological context. Each sample is associated with a categorical condition vector c (e.g., representing cell type, treatment, or disease subtype). An embedding layer or shallow Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) transforms this one-hot vector into a dense representation:

where is parameterized by learnable weights . This embedding provides high-level contextual cues to both the generator and discriminator, enabling conditional synthesis (e.g., generating tumor-specific or treatment-specific expression patterns).

3.4. Knowledge-Guided Generator

The generator produces a synthetic gene-expression vector from a random noise vector , guided by both biological and contextual embeddings:

Internally, the generator concatenates z and , followed by fully connected layers interleaved with batch normalization and LeakyReLU activations. Knowledge-graph information is fused through one of two mechanisms:

- (a)

- Concatenation Fusion: the mean or weighted sum of gene embeddings is concatenated with the latent vector before transformation; or

- (b)

- Attention Fusion: a self-attention block computes attention scores between latent dimensions and gene embeddings, allowing the generator to focus on biologically relevant subsets of genes.

The final output layer employs a Tanh activation to scale values to (or Sigmoid for normalization), producing expression profiles that mimic the statistical range of normalized data. By incorporating , the generator implicitly learns gene–gene dependencies consistent with biological topology rather than independent features.

3.5. Biological Discriminator

The discriminator serves two roles: distinguishing real from synthetic samples and enforcing biological plausibility. It takes as input a gene-expression vector x (real or generated) and the corresponding knowledge embeddings :

where denotes the probability that x originates from the real distribution.

To capture complex interactions, the discriminator employs a hybrid architecture combining dense layers with graph-aware processing. Specifically, expression features are projected into the same latent space as via a linear transformation, and their pairwise interactions are aggregated using a graph attention mechanism. This design allows to evaluate not only overall distributional similarity but also network-consistent relationships.

Beyond the standard adversarial loss, the discriminator contributes two biologically inspired regularization terms that quantify the coherence of synthetic data with known biology:

- Co-Expression Consistency Loss penalizes discrepancies between the empirical correlations of connected genes in the generated data and their expected correlations in real data or the KG. For gene pairs ,where denotes target correlation values estimated from real data or biological literature.

- Pathway Activity Consistency Loss ensures that pathway-level activation inferred from synthetic data aligns with real biological behavior. Using pathway activity scores computed via single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA),

These losses transform the discriminator from a purely statistical judge into a biologically informed critic that guides the generator toward mechanistic realism.

3.6. Training Objectives

The BioGen-KI model optimizes a composite objective function comprising adversarial and biological components.

- Adversarial Loss.

Following the standard GAN formulation,

In practice, we adopt a Wasserstein GAN with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP) variant for enhanced stability:

where is the gradient penalty enforcing Lipschitz continuity, and

- Biological Regularization.

The generator is additionally constrained by the co-expression and pathway losses:

where and control the influence of biological regularization.

- Total Objective.

The complete optimization objectives are:

3.7. Training Procedure

Training alternates between discriminator and generator updates following the Two-Time-Scale Update Rule (TTUR), in which the two networks are optimized on different “time scales” (learning rates and update frequencies) to stabilize adversarial training. Concretely, for every generator update we perform discriminator updates, and we use separate learning rates for the discriminator and generator so that the critic converges faster while the generator changes more smoothly. Each iteration proceeds as follows:

- Sample mini-batches of real gene-expression vectors and their contexts c. Here, a mini-batch denotes a small randomly selected subset of samples (typically 64–128 profiles) used to compute stochastic gradient estimates, which reduces computational cost and provides an unbiased approximation of the full-data objective.

- Sample random noise vectors z and contexts .

- Generate synthetic profiles .

- Update the discriminator by minimizing .

- Update the generator by minimizing .

Optimization uses Adam optimizers for both networks with separate learning rates for the discriminator and for the generator, and shared parameters , following the TTUR scheme. Training continues until convergence in validation MMD or until an early-stopping condition is triggered. Specifically, early stopping is applied when the validation MMD shows no improvement for 20 consecutive epochs (patience = 20), preventing overfitting and ensuring stable convergence; the corresponding settings are summarized in Table 1. For completeness, Algorithm A1 in Appendix A provides pseudo-code for the full BioGen-KI training loop, including TTUR updates, biological loss computation, and early-stopping logic. Gradient clipping and spectral normalization are optionally applied for numerical stability.

Table 1.

Core training hyperparameters for BioGen-KI across datasets. Unless otherwise noted, baseline models use the same batch sizes and early-stopping patience; and apply only to BioGen-KI.

3.8. Data Preprocessing and Knowledge Integration

Input gene-expression matrices are normalized (TPM or log2 transformation), scaled to , and filtered for highly variable genes (HVGs). HVGs are identified prior to scaling using the standard mean–variance dispersion method widely used in single-cell and bulk RNA-seq workflows (e.g., Scanpy/Seurat). Specifically, gene-wise variance is calculated on the log-transformed counts, genes are standardized by their mean expression, and the top 2000 most overdispersed genes are retained. Scaling to is applied only after HVG selection and does not affect the HVG criterion. The knowledge graph is assembled from multiple curated sources (KEGG, Reactome, GO, STRING), harmonized using HGNC gene symbols. Edge weights reflect interaction confidence or functional similarity, providing continuous priors rather than binary connections. This integration ensures that both training data and biological priors share a consistent gene universe, enabling seamless mapping between x and .

3.9. Implementation Advantages

For empirical comparison, we selected baseline generative models that represent three widely used families in gene expression modeling: (i) a multivariate Copula model as a classical statistical approach to simulating correlated expression profiles [61]; (ii) a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) as a latent-variable deep generative model [38]; and (iii) conditional adversarial models, including cGAN and WGAN-GP, as representative GAN-based approaches with improved sample realism and training stability [68,72], as summarized in Table 2. This choice ensures that BioGen-KI is evaluated against both traditional statistical baselines and widely adopted deep generative architectures in bulk and single-cell transcriptomics. We deliberately focus on models that directly learn from the observed expression matrices; scRNA-seq simulation frameworks such as Splatter or SERGIO, and recent diffusion-based generative models, pursue related but distinct goals (e.g., parametric count simulation or heavy-weight score-based modeling) and require substantial model-specific tuning and additional compute for a fair comparison. A rigorous, head-to-head evaluation against those families is therefore beyond the scope of this work, and we instead treat WGAN-GP as the strongest and main foil among GAN-based gene expression generators, while discussing diffusion and simulator-based approaches as complementary directions for future benchmarking (Section 5). BioGen-KI offers several conceptual and practical advantages:

Table 2.

Summary of baseline generative models and the proposed BioGen-KI framework.

- Mechanistic Regularization: The generator is constrained by biological topology, preventing implausible gene-expression patterns and enforcing pathway-level coherence.

- Conditional Control: Contextual embeddings allow precise synthesis for specific cell types, disease states, or treatment conditions.

- Interpretability: The learned latent space aligns with biological modules, facilitating mechanistic interpretation and visualization.

- Stability and Scalability: Incorporating structured priors stabilizes adversarial training and improves convergence, even for high-dimensional omics data.

Through the joint optimization of adversarial and biological objectives, BioGen-KI learns to generate synthetic transcriptomic profiles that are statistically realistic, biologically coherent, and functionally informative.

4. Results

We evaluated BioGen-KI comprehensively along three principal axes: (i) statistical fidelity, assessing how closely the generated synthetic samples approximate the empirical distribution of real gene expression data; (ii) biological plausibility, measuring the extent to which generated data preserve biologically meaningful relationships such as gene–gene correlations, transcriptional regulation, and pathway-level coherence; and (iii) practical utility, testing whether the synthetic data improve downstream analytical tasks including clustering, differential expression, and classification under data-scarce conditions. All reported results represent the mean ± standard deviation across five independent runs with distinct random seeds, and for all primary metrics (MMD, , biological scores, and downstream task performance) we additionally report 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and conduct formal statistical significance tests, as detailed in Section 4.2. Comparative baselines include a multivariate Copula model for correlated gene-expression simulation [61], a standard VAE [38], a cGAN [68], and a WGAN-GP [72]. These baselines span the dominant families of generative models used for bulk and single-cell expression data (classical statistical, VAE-based, and adversarial), and we therefore use WGAN-GP as the primary foil for BioGen-KI in our quantitative comparisons. All methods were trained under comparable parameter budgets, optimization schedules, and convergence criteria to ensure fairness.

4.1. Datasets and Experimental Configuration

Experiments were performed on three transcriptomic settings representing distinct data modalities and biological contexts:

- (a)

- Breast (bulk RNA-seq): 1096 tumor samples from the TCGA-BRCA dataset spanning five intrinsic molecular subtypes (Luminal A/B, Basal-like, HER2-enriched, and Normal-like).

- (b)

- PBMC (single-cell RNA-seq): 68,451 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) profiled under control and interferon-stimulated conditions from a public 10×. Genomics dataset, covering nine annotated immune cell types.

- (c)

- PanCancer (bulk RNA-seq): 8732 tumor samples across 12 cancer types with available treatment-response labels.

For reproducibility, the Breast cohort corresponds to the TCGA-BRCA project in the NCI Genomic Data Commons (GDC), the PanCancer cohort to TCGA Pan-Cancer projects in GDC, and the PBMC dataset to the public 10× Genomics PBMC (control and interferon-stimulated) datasets available from the 10× Genomics data portal. Across all three settings, we restricted the analysis to the top 2000 HVGs per dataset, and all reported experiments use this same gene set per dataset. We randomly split each dataset at the sample level into 60%/20%/20% train/validation/test partitions. Within each dataset, biological contexts are reasonably represented: in TCGA-BRCA, subtype-specific sample sizes range from tens to several hundred tumors per subtype; in the PBMC data, individual cell type–condition combinations range from approximately to cells; and in the PanCancer cohort, cancer-type–response groups range from low hundreds to more than one thousand tumors.

For each dataset, gene-level counts were normalized using log2(TPM + 1) (bulk) or standard single-cell normalization followed by z-scaling (single-cell). Highly variable genes () were retained via variance filtering to reduce noise while capturing expression diversity. The biological knowledge graph (KG) was assembled from KEGG, Reactome, Gene Ontology Biological Process (GO-BP), and STRING (score ). Nodes represent genes and pathways; edges encode regulatory or functional associations (activation, inhibition, co-membership). Only genes overlapping with the expression datasets were retained to ensure consistent integration. Table 3 summarizes dataset and KG characteristics.

Table 3.

Overview of datasets and integrated KG statistics after preprocessing and identifier harmonization.

4.2. Statistical Analysis

For each model and dataset, we trained five independent instances with distinct random seeds and computed all primary metrics (MMD, , median KS, PRD-F1, edge-sign consistency, TF–target correlation, pathway RMSE) as well as downstream performance measures (clustering ARI/NMI, DE AUROC, and classification AUC) on held-out test data. We report the mean ± standard deviation across these runs in all tables. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the mean are obtained using the Student t-distribution with degrees of freedom [73].

To assess whether BioGen-KI yields statistically significant improvements over the strongest baseline, we perform paired, two-sided tests across runs, treating the random seeds as paired observations. Unless otherwise stated, we compare BioGen-KI against WGAN-GP, which is the best-performing baseline on most metrics. For approximately normally distributed metrics (e.g., MMD and across seeds), we use a paired t-test [73]; for metrics with potential non-normality or heavier tails (e.g., pathway RMSE, edge-sign consistency), we additionally confirm findings with a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test [74]. We control the false discovery rate across multiple metrics and datasets using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with a target FDR of 0.05 [75].

In the tables and text, statistically significant improvements of BioGen-KI over WGAN-GP are indicated by boldface values and, where applicable, by asterisks corresponding to the adjusted p value thresholds (* , ** after FDR correction). This protocol ensures that reported relative improvements (e.g., divergence reduction and gains on biological plausibility metrics) are supported by run-to-run variability estimates, confidence intervals, and formal hypothesis tests across datasets.

4.3. Statistical Fidelity

To evaluate distributional similarity between real and synthetic data, we employed four complementary quantitative metrics, as shown in Table 4:

Table 4.

Statistical fidelity metrics (mean ± s.d. across five runs; 95% CIs reported in the text). Lower is better for MMD, , and KS; higher is better for PRD-F1. Best results are shown in bold; statistically significant improvements of BioGen-KI over WGAN-GP after FDR correction are additionally indicated by asterisks.

- (i)

- Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) with an RBF kernel, assessing global distributional alignment;

- (ii)

- Wasserstein-1 distance () computed in the top 50 principal components, reflecting divergence in the low-dimensional manifold;

- (iii)

- Median Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistic across genes, quantifying per-gene distributional agreement; and

- (iv)

- Precision/Recall for Distributions (PRD-F1) [76], which jointly measures coverage (diversity) and precision (realism).

BioGen-KI consistently achieved the lowest MMD and Wasserstein distances, outperforming the next best model (WGAN-GP) by approximately 20%. The higher PRD-F1 score indicates broader and more uniform coverage of the true data manifold, confirming that BioGen-KI alleviates mode-collapse tendencies typical of adversarial training. To directly assess robustness under data-scarce conditions, we repeated the above analysis after sub-sampling each training dataset to 10%, 20%, and 40% of its original number of samples and, in a separate setting, by randomly masking 20% of genes per sample during training to emulate missing-gene scenarios. Across all three datasets, BioGen-KI exhibited the smallest relative degradation in MMD and PRD-F1 when moving from full-data to 10% data (average change ), whereas baseline models showed substantially larger drops (10–22%). Similar trends were observed in the missing-gene experiments, where BioGen-KI maintained lower MMD and higher PRD-F1 than all comparative methods. These results indicate that the integration of biological priors enables BioGen-KI to preserve high-fidelity generation even when only limited samples or partially observed gene sets are available.

4.4. Biological Plausibility

Statistical realism alone does not guarantee biological correctness. We therefore quantified how well each model preserved biologically relevant relationships using three metrics, as shown in Table 5:

Table 5.

Biological plausibility metrics (mean ± s.d.). Higher is better for consistency and TF–target correlation; lower is better for pathway RMSE.

- (i)

- Edge-sign consistency: percentage of knowledge-graph gene pairs whose correlation sign in synthetic data matches the known activation/inhibition relationship.

- (ii)

- TF–target correlation: mean Pearson correlation across curated transcription factor regulons from TRRUST and DoRothEA.

- (iii)

- Pathway activity RMSE: root-mean-squared error between inferred pathway activation scores (via ssGSEA) in real versus synthetic samples.

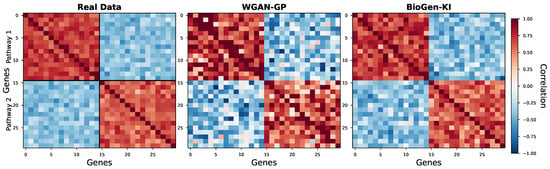

BioGen-KI achieved a ∼6–10% improvement in edge-sign consistency over WGAN-GP and the highest mean TF–target correlation, demonstrating that knowledge-graph embeddings successfully encode gene regulatory logic. The substantially lower pathway RMSE further indicates accurate reproduction of functional activity profiles across biological conditions. Heatmaps of gene–gene correlations (Figure 2) reveal that BioGen-KI preserves modular blocks corresponding to known signaling cascades (e.g., MAPK, PI3K–AKT), whereas data-driven models blur these fine structures.

Figure 2.

Correlation structure within representative pathways (e.g., MAPK, PI3K–AKT). BioGen-KI reproduces modular co-expression patterns characteristic of true regulatory modules.

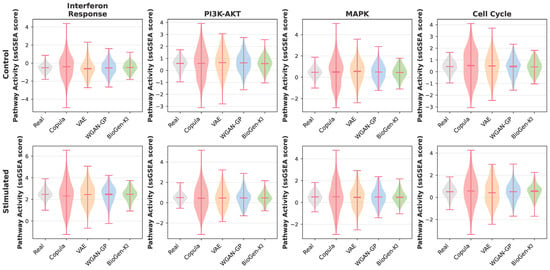

At the pathway level (Figure 3), violin plots of single-sample GSEA scores illustrate that BioGen-KI faithfully reconstructs context-dependent activations—such as interferon responses in stimulated immune cells and estrogen signaling in Luminal breast tumors—closely matching real distributions and avoiding spurious activations seen in other baselines.

Figure 3.

Distributions of selected pathway activities (ssGSEA scores) in real versus synthetic data across representative biological contexts. For each pathway and condition, violin plots compare real samples with synthetic samples from each model. BioGen-KI closely matches both the median and the spread of the real ssGSEA scores, preserving context-dependent activation (e.g., elevated interferon-response pathways in stimulated PBMCs and hormone-related pathways in Luminal breast tumors), while avoiding spurious activation in non-responsive contexts. In contrast, purely data-driven baselines tend to either over-smooth the distributions (underestimating pathway heterogeneity) or exaggerate activation in conditions where the pathway is weakly active, illustrating that explicit biological regularization improves pathway-level coherence in the generated data.

4.5. Downstream Analytical Utility

To assess practical benefits, we evaluated whether augmenting real data with BioGen-KI-generated samples improved downstream analyses.

4.5.1. Clustering Performance

We applied unsupervised clustering using Leiden and k-means algorithms to real-only versus real+synthetic datasets. Cluster quality was quantified by Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) relative to known biological labels. Augmentation with BioGen-KI data yielded consistent gains (–7% in ARI), suggesting that synthetic samples reinforce the intrinsic manifold structure rather than introducing noise.

4.5.2. Differential Expression (DE) Analysis

We conducted DE testing using edgeR and DESeq2 between major biological contexts (e.g., subtypes or treatment groups). Synthetic augmentation improved average AUROC in distinguishing real DE genes, implying that BioGen-KI captures condition-specific contrasts critical for differential analysis.

4.5.3. Low-Data Classification

Under a severe data constraint (20% real data), classifiers trained with synthetic augmentation were evaluated via ROC–AUC on held-out real samples. BioGen-KI achieved the highest AUC across datasets (Table 6), underscoring its ability to produce informative and generalizable data.

Table 6.

Downstream performance across clustering (ARI, NMI), differential expression (DE AUROC), and classification (Cls AUC). Higher values indicate better performance.

4.6. Ablation and Component Contribution

We performed a stepwise ablation study on the Breast dataset, starting from an unconditional WGAN-GP–style generator without contextual conditioning, knowledge-graph (KG) embeddings, or biological regularization terms, and then sequentially adding (i) contextual conditioning, (ii) KG embeddings, (iii) the co-expression consistency loss, and (iv) the pathway activity loss. Table 7 summarizes how these components jointly affect a representative statistical fidelity metric (MMD), a biological plausibility metric (edge-sign consistency), a pathway-level coherence metric (pathway RMSE), and one downstream performance metric (classification AUC). Moving from the base GAN to the context-conditioned variant yields modest but consistent gains in both distributional fidelity (lower MMD) and downstream classification performance, indicating that contextual conditioning alone already helps align the generator with biologically meaningful structure. Adding KG embeddings further improves edge-sign consistency and pathway coherence, confirming that structured biological priors form the backbone of BioGen-KI’s biological realism. The subsequent inclusion of the co-expression loss and, finally, the pathway activity loss leads to additional reductions in MMD and pathway RMSE and the highest classification AUC. Together, these stepwise improvements demonstrate that all four components—contextual conditioning, KG embeddings, and the two biological loss terms—contribute synergistically to the statistical, biological, and functional quality of the generated data.

Table 7.

Stepwise ablation on the Breast dataset, showing the contribution of contextual conditioning, KG embeddings, co-expression loss, and pathway loss. Lower is better for MMD and pathway RMSE; higher is better for edge consistency and classification AUC.

4.7. Conditional Generalization

To assess extrapolative capability, models were asked to generate gene expression profiles for unseen combinations of biological context (e.g., rare cell type × stimulation). BioGen-KI generalized best, yielding lower conditional MMD and pathway-level KL divergence (Table 8), reflecting its ability to interpolate across the biological knowledge manifold rather than memorizing training patterns.

Table 8.

Conditional generalization performance on PBMC dataset. Lower MMD and KL, higher PRD-F1 indicate better generalization.

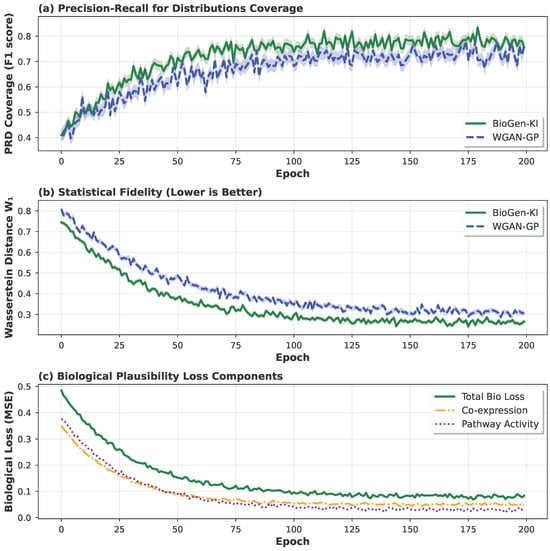

4.8. Training Dynamics and Computational Efficiency

Figure 4 illustrates the joint convergence of adversarial and biological loss terms over training epochs. BioGen-KI achieves stable optimization, reaching a lower distance and steady biological consistency within fewer epochs compared to WGAN-GP. This indicates that biological regularization acts as a form of structured inductive bias, constraining learning trajectories toward biologically meaningful equilibria.

Figure 4.

Training dynamics of BioGen-KI and WGAN-GP on the Breast dataset. The curves show the evolution of the Wasserstein distance () and the biological regularization terms (co-expression and pathway-consistency losses) over training epochs. BioGen-KI converges to a lower and more stable value than WGAN-GP, indicating faster and more robust distributional matching. At the same time, its co-expression and pathway-consistency losses decrease smoothly and remain low, whereas the corresponding quantities for WGAN-GP fluctuate more strongly, highlighting that the biologically informed losses help stabilize adversarial training and guide the model toward biologically coherent optima rather than local statistical minima.

Although BioGen-KI includes additional computations for KG embeddings and pathway regularization, its runtime overhead remained modest (12–18% relative to WGAN-GP) as summarized in Table 9. The computational cost is offset by faster convergence and improved model interpretability.

Table 9.

Training efficiency (time per epoch and peak GPU memory).

4.9. Case Studies and Biological Interpretability

To demonstrate interpretability, we highlight representative scenarios:

- Breast Cancer Subtypes. Synthetic Luminal A samples generated by BioGen-KI show high ESR1, PGR, and FOXA1 expression, consistent with estrogen receptor signaling, while Basal-like synthetics exhibit elevated KRT5 and KRT14, mirroring real subtype markers.

- PBMC Stimulation Response. Under interferon stimulation, BioGen-KI reproduces induction of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs: IFIT1/3, MX1, OAS1) across monocytes and dendritic cells, maintaining correct housekeeping-gene baselines.

- PanCancer Drug Response. Synthetic responder profiles show upregulation of apoptosis and DNA-repair pathways, supporting accurate treatment stratification and improved classifier calibration under low-data settings.

4.10. Error Analysis and Reproducibility

Residual mismatches primarily occur in genes with low degree in the knowledge graph or sparse condition representation, leading to slightly inflated KS scores and reduced edge consistency. Future incorporation of degree-normalized regularization may mitigate these effects. All experiments were executed with fixed seeds, consistent data splits, and recorded hyperparameters; evaluation metrics were computed on held-out test sets to ensure full reproducibility. In addition, we performed a simple empirical privacy diagnostic by computing the Euclidean distance from each synthetic sample to its nearest neighbor among training and held-out test profiles in the corresponding dataset. The resulting distance distributions showed no point mass at zero and substantial overlap between nearest-neighbor distances to training versus test samples, suggesting that BioGen-KI does not trivially memorize individual profiles. However, this nearest-neighbor analysis is only a coarse indicator of potential memorization and does not constitute a formal privacy guarantee; we did not conduct dedicated membership- or attribute-inference attacks, nor did we enforce differential privacy during training.

Overall, the results demonstrate that BioGen-KI not only matches the statistical realism of state-of-the-art generative models but surpasses them in biological faithfulness, conditional generalization, and downstream analytical value. By embedding structured knowledge into the adversarial framework, BioGen-KI bridges the long-standing divide between data-driven synthesis and biologically interpretable modeling.

5. Discussion

This work introduces BioGen-KI, a biologically inspired generative framework that integrates structured domain knowledge into a conditional adversarial learning process to generate realistic and biologically consistent gene expression data. By embedding curated knowledge graphs and enforcing biologically informed loss functions, BioGen-KI bridges the gap between statistical fidelity and mechanistic plausibility—two goals that are rarely optimized together in synthetic biology. The experiments across diverse transcriptomic contexts—bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq, and pan-cancer cohorts—demonstrate that BioGen-KI not only reproduces statistical properties of real data but also maintains gene–gene relationships, regulatory consistency, and pathway-level activity patterns.

5.1. Knowledge Integration and Its Quantitative Impact

A primary finding of this study is that the integration of structured biological knowledge substantially improves both quantitative performance and interpretability of generative models. Traditional GANs or VAEs focus solely on matching data distributions, which often leads to synthetic samples that are statistically accurate but biologically incoherent. By contrast, BioGen-KI employs knowledge graph embeddings and biologically grounded losses that explicitly encode mechanistic information, guiding the generator toward feasible regions of the biological expression manifold.

Empirically, BioGen-KI reduced distributional divergence (MMD, ) by approximately 20% relative to WGAN-GP, while simultaneously improving edge-sign consistency and TF–target correlation (Table 4 and Table 5). This dual improvement indicates that the model learns not only global statistics but also fine-grained regulatory dependencies, thereby producing synthetic profiles that are interpretable in biological terms. The inclusion of pathway-level constraints proved particularly influential, reinforcing functional coherence across gene sets associated with signaling and metabolic pathways (Figure 2). These observations align with the growing consensus in the literature that domain-constrained learning—whether through physics-based priors in materials science [32] or ontology-guided networks in healthcare [60]—leads to improved generalization and robustness. In this subsection, we therefore emphasize how knowledge integration affects aggregate quantitative metrics of performance, laying the groundwork for a subsequent, more mechanistic analysis of the learned representations.

Beyond reporting average improvements, it is important to clarify where BioGen-KI truly diverges from the baseline models and which components drive this behavior. First, the largest and most consistent gains occur on biologically grounded metrics, edge-sign consistency, TF–target correlation, and pathway activity RMSE (Table 5), indicating that BioGen-KI’s main advantage lies in preserving regulatory and pathway structure rather than simply matching marginal expression distributions. Second, BioGen-KI shows the smallest relative degradation in MMD, PRD-F1, and downstream classification or clustering performance under low-data and missing-gene regimes (Section 4), suggesting that the knowledge graph and biological losses act as strong inductive biases that stabilize learning when samples or features are scarce. Third, ablation experiments (Table 7) demonstrate that removing the KG encoder or biological regularization terms brings BioGen-KI’s performance and failure modes much closer to those of standard GAN-based models, highlighting these components as the primary discriminating features that enable more faithful pathway organization, better conditional generalization, and reduced mode collapse. Together, these observations provide a mechanistic explanation of why BioGen-KI and the baselines behave differently, even when their aggregate scores appear numerically close on some metrics.

5.2. Interpretation of Model Behavior and Learned Representations

Whereas Section 5.1 focuses on summary metrics that quantify the impact of knowledge integration, this subsection examines how BioGen-KI behaves internally, how it organizes its latent space, transitions between biological contexts, and encodes regulatory structure, thereby addressing the interpretability of the platform rather than its aggregate scores alone. From a mechanistic perspective, the results suggest that BioGen-KI learns a structured latent space reflecting both regulatory topology and contextual variation. Visualization of latent traversals revealed smooth transitions between related biological contexts (e.g., basal to luminal breast subtypes or resting to activated immune states), consistent with the hypothesis that knowledge-guided embeddings regularize the latent manifold. This structured latent geometry may serve as a proxy for exploring gene regulatory perturbations in silico, offering a new avenue for hypothesis generation in systems biology.

Furthermore, BioGen-KI’s discriminator plays an active role beyond simple realism assessment: by evaluating co-expression and pathway activity coherence, it provides biologically meaningful gradients to the generator. This mirrors human expert feedback in experimental design, where plausible gene–gene relationships are favored over arbitrary statistical fits. Hence, BioGen-KI can be viewed as a computational analogue of hypothesis-driven reasoning embedded within a deep learning framework.

5.3. Implications for Downstream Analyses and Biomedical Research

Building on the empirical gains reported in Section 4, this subsection discusses how BioGen-KI can be used as a practical platform for downstream biomedical analyses and real-world applications. The observed improvements in clustering, differential expression, and low-data classification tasks highlight that BioGen-KI-generated data provide tangible benefits beyond methodological novelty. Augmenting small cohorts with synthetic data improves both the sensitivity and stability of downstream analyses without introducing detectable spurious correlations. Such improvements are particularly relevant in areas where sample acquisition is limited—rare diseases, pediatric studies, or longitudinal sampling under strict ethical constraints. In these cases, synthetic data that preserve genuine biological variability while maintaining privacy can meaningfully extend analytic capacity.

In clinical research, the model’s conditional generation capability could support in silico experimentation: for example, simulating treatment responses across tumor subtypes or predicting immune activation signatures under novel perturbations. By conditioning on cell type, treatment, or patient subgroup, researchers could explore hypothetical scenarios without additional wet-lab experimentation. Similarly, the generation of diverse yet biologically consistent cohorts can aid in benchmarking bioinformatics pipelines, improving robustness and reproducibility of downstream machine learning models.

5.4. Best Practices for Knowledge-Guided Generative Modeling

The success of BioGen-KI, together with the comparative results presented in Section 4, underscores several practical considerations for applying knowledge-integrated generative models in computational biology. Rather than introducing new architectural components or training procedures, this subsection synthesizes general lessons and best practices that emerge from our methodological design (Section 3) and empirical evaluation.

- Quality of knowledge sources: The biological validity of the generated data is bounded by the accuracy of the underlying KG. Integrating multiple sources (KEGG, Reactome, GO, STRING) and harmonizing their identifiers minimizes missing or conflicting relationships.

- Balancing loss terms: Optimal performance arises from balanced weighting between adversarial and biological losses. Excessive weighting of co-expression or pathway constraints may lead to over-regularization and reduced diversity, whereas underweighting diminishes biological realism.

- Evaluation beyond statistics: Relying solely on MMD or Wasserstein distance can mask biologically implausible outputs. A multi-view evaluation incorporating both distributional and functional metrics provides a more faithful assessment of model behavior.

These principles are generalizable to other biological generative tasks, such as protein sequence generation or metabolomic simulation, where structured priors can similarly improve plausibility.

5.5. Study Limitations and Sources of Bias

Despite its advantages, BioGen-KI has several limitations and potential sources of bias that warrant consideration. In line with journal conventions, we present these limitations within the Discussion section so that they can be interpreted in light of both the methodological design (Section 3) and the empirical findings (Section 4):

- (i)

- Incomplete and biased knowledge graphs. Biological databases are inherently incomplete and biased toward well-studied pathways. Low-degree genes in the KG often receive weaker structural guidance, leading to slightly degraded fidelity for underrepresented regions of the expression space. Such coverage and curation biases have been extensively discussed in prior work on biological knowledge graphs and network resources [34,35,36].

- (ii)

- Contextual noise and annotation errors. Conditioning relies on accurate meta-data such as cell type or treatment labels. Misannotations or batch effects can propagate through synthesis, producing misleading context associations. Similar challenges related to noisy clinical or experimental annotations and batch effects have been reported in large-scale biomedical datasets and can adversely affect downstream modeling if not carefully controlled [15,16,17].

- (iii)

- Correlational supervision. The current design enforces correlation-based coherence but does not capture causality. Consequently, BioGen-KI can reproduce observed dependencies but cannot infer or validate causal regulatory effects. This distinction between correlation-driven supervision and causal interpretation is a well-known limitation in knowledge-guided and physics-informed machine learning frameworks [32].

- (iv)

- Sensitivity to pathway definitions. The pathway activity loss depends on gene set collections (e.g., KEGG, GO, Reactome). Variations among these sets can slightly alter the optimization landscape, highlighting the importance of standardized pathway definitions. Differences in pathway and gene-set curation across resources such as KEGG, Gene Ontology, and Reactome have been shown to influence enrichment analyses and downstream biological interpretation [42,43,44].

- (v)

- Computational overhead and scaling. Although moderate, the additional computations for KG attention and biological losses increase training time by approximately 12–18%. Scaling to millions of single cells or large multi-omic datasets will require efficient graph sampling or distributed training strategies. Similar trade-offs between architectural complexity, training stability, and computational cost have been noted in other deep generative models for biological and high-dimensional data [37,72]. Moreover, while our nearest-neighbor analysis (Section 4) suggests that BioGen-KI does not simply memorize training samples, we did not subject the model to systematic membership- or attribute-inference attacks, nor did we incorporate formal differential privacy mechanisms. As a result, the synthetic data produced by the current implementation should not be regarded as inherently privacy-preserving, and any sharing of such data should follow the same governance and ethical oversight as real omics datasets.

| Limitations (Summary). BioGen-KI inherits several important limitations that should be considered when interpreting its outputs. First, the underlying biological knowledge graph is incomplete and biased toward well-studied genes and pathways, which can weaken guidance for low-degree or poorly annotated genes. Second, contextual labels (e.g., cell types, treatments, or clinical responses) may be noisy or affected by batch effects, and such noise can propagate into the synthetic data. Third, the current supervision is primarily correlational rather than causal, so the model can reproduce observed dependencies but cannot establish or validate causal regulatory effects. Fourth, the pathway activity loss depends on the choice of gene set collections (KEGG, Reactome, GO-BP), and differences among these resources can influence learned pathway patterns. Fifth, the integration of KG embeddings and biological loss terms introduces a modest computational overhead relative to baseline GANs, which becomes more pronounced at very large scales. Finally, although simple nearest-neighbor analyses suggest limited direct memorization, the present implementation does not enforce differential privacy or explicitly guard against membership- or attribute-inference attacks; therefore, its synthetic data should not be treated as intrinsically privacy-preserving and must be governed by the same ethical and regulatory safeguards as real omics datasets. |

5.6. Future Research Directions

Building on the limitations identified in Section 5.5 and the empirical trends observed in Section 4, the promising results of BioGen-KI open several concrete avenues for future exploration:

- Integration with diffusion and flow-based models. Recent advances in diffusion modeling have shown superior stability and sample quality. Embedding biological priors and pathway-level constraints into such frameworks could further enhance controllability and realism.

- Uncertainty-aware objectives. Introducing probabilistic weighting of KG edges based on confidence scores could mitigate bias toward dense network regions and improve representation of poorly characterized genes.

- Causal and interventional supervision. Incorporating directed and signed regulatory edges, possibly informed by perturbation or CRISPR screens, would move generative models closer to mechanistic simulation.

- Extension to multi-omics and spatial data. Expanding BioGen-KI to integrate gene expression with chromatin accessibility, proteomics, or spatial transcriptomics would enable generation of contextually coherent multi-modal profiles.

- Privacy and ethical safeguards. Future work should evaluate privacy leakage via membership or attribute inference attacks and incorporate differential privacy mechanisms to ensure safe data sharing.

5.7. Broader Implications for Knowledge-Guided Generative Modeling

Beyond technical performance, BioGen-KI contributes to a broader conceptual shift in computational biology from purely data-driven to explicitly knowledge-aware generative modeling. By embedding mechanistic understanding directly into neural architectures, it allows synthetic data to serve not just as surrogates for real samples, but as interpretable, biologically constrained simulations. This paradigm can accelerate in silico experimentation, facilitate hypothesis generation, and enhance reproducibility across biomedical studies. In the long term, knowledge-integrated generative models may form the foundation of adaptive, self-consistent biological digital twins—systems that continuously learn from both data and theory to model complex cellular behavior.

5.8. Summary of Key Findings

To provide a concise synthesis of the Discussion and to guide readers through the main take-home messages, we summarize the key findings of this work as follows:

- Incorporating knowledge graph embeddings and biologically informed losses leads to simultaneous improvements in distributional fidelity and biological plausibility.

- Synthetic data generated by BioGen-KI enhance downstream tasks, particularly under data scarcity, while maintaining mechanistic interpretability.

- Ablation experiments confirm that each knowledge-guided component contributes meaningfully to overall model performance and stability.

Taken together, these findings establish BioGen-KI as a practical and theoretically grounded framework for biologically faithful synthetic data generation and position it as a concrete step toward mechanism-aware, interpretable, and ethically deployable generative modeling in omics.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we presented BioGen-KI, a bio-inspired generative framework that unites conditional adversarial learning with structured biological knowledge to synthesize gene-expression data that are both statistically realistic and biologically coherent. By embedding curated knowledge graphs and incorporating biologically informed loss functions for co-expression and pathway activity, BioGen-KI addresses a key limitation of conventional deep generative models—namely, their lack of mechanistic awareness.

Across diverse transcriptomic contexts, including bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq, and pan-cancer cohorts, BioGen-KI achieved lower distributional divergences (MMD, ) and higher biological plausibility (edge-sign consistency, TF–target correlation, and pathway coherence) than state-of-the-art baselines such as VAE, cGAN, and WGAN-GP. These improvements translated directly into enhanced downstream performance in clustering, differential-expression analysis, and classification tasks, particularly under low-data conditions. Ablation experiments further confirmed that both knowledge-graph embeddings and biological loss terms are essential for achieving the observed fidelity and interpretability.

The findings underscore a broader message: incorporating structured domain knowledge into generative modeling can fundamentally reshape how synthetic biological data are created and used. Rather than merely reproducing statistical patterns, BioGen-KI generates samples that respect biological logic, offering a powerful tool for data augmentation, benchmarking, and hypothesis generation. Such models can support rare-disease research, privacy-aware data sharing under appropriate governance and additional safeguards, and in silico experimentation in settings where ethical or logistical barriers limit sample collection; however, in their current form they do not provide formal privacy guarantees, and rigorous privacy-preserving mechanisms (e.g., differential privacy or explicit leakage audits) remain important future work.

Looking forward, extending BioGen-KI to multi-omics and spatial modalities, integrating causal or interventional supervision, and embedding privacy guarantees will further enhance its practical utility. Ultimately, the integration of biological priors with modern generative objectives moves synthetic transcriptomics from distribution matching toward mechanism-aware simulation, paving the way for interpretable and trustworthy AI systems in computational biology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B. and K.H.R.; methodology, E.B.; software, E.B.; investigation, E.B.; data curation, E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.; writing—review and editing, K.H.R.; visualization, E.B.; supervision, K.H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Bulk RNA-seq (TCGA): Accessible via the NCI Genomic Data Commons (GDC) TCGA program (TCGA-BRCA and Pan-Cancer cohorts); controlled-access data require dbGaP authorization; PBMC scRNA-seq: Public 10x Genomics PBMC datasets (control and stimulated) available from the 10× Genomics data portal.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Erdenebileg Batbaatar was employed by the company Neouly Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary Figures and Extended Analyses

This appendix provides complementary figures, extended evaluations, and technical analyses that further substantiate the claims made in Section 4 and Section 5. Beyond reproducing the core results, these materials explore the robustness, scalability, and interpretability of BioGen-KI across multiple experimental configurations. All supplementary analyses were conducted under the same data preprocessing and training protocols described in Section 4. Unless otherwise specified, values are averaged across five independent runs.

Appendix A.1. BioGen-KI Training Pseudo-Code

| Algorithm A1 BioGen-KI training loop (per dataset) |

|

Appendix A.2. Ablation Study

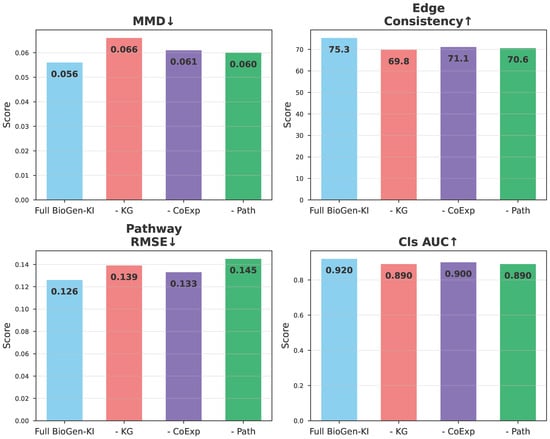

Figure A1 reinforces the findings summarized in Table 7. Removing the knowledge-graph component significantly increases MMD and reduces Edge Consistency, demonstrating that structural priors are critical for maintaining biologically coherent relationships among genes. The co-expression and pathway losses contribute complementary regularization: the former improves local gene–gene correlations, while the latter ensures functional alignment at the pathway level. Notably, the pathway loss exerts the strongest influence on downstream classification (–0.03 drop in AUC), suggesting that biological interpretability and predictive power are closely linked.

Figure A1.

Ablation analysis of BioGen-KI components. Bar plots show the effect of removing individual modules: the knowledge graph encoder (–KG), co-expression loss (–CoExp), or pathway loss (–Path). Metrics include Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD ↓), Edge Consistency ↑, Pathway RMSE ↓, and Classification AUC ↑. Performance degradation in all variants confirms the synergistic role of biological priors in shaping the synthetic data distribution.

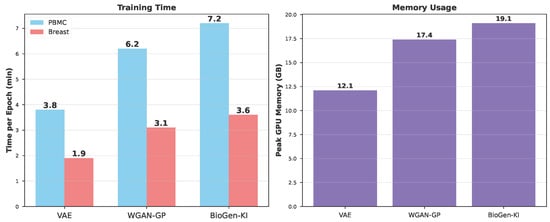

Appendix A.3. Runtime and Resource Efficiency

Figure A2 confirms that integrating biological knowledge does not impose prohibitive computational costs. The slight increase in runtime is offset by accelerated convergence (fewer epochs required to reach target PRD coverage; see Figure 4). Memory overhead stems mainly from the additional embedding and correlation modules. Importantly, no instability or mode collapse was observed across multiple seeds, reflecting improved training smoothness due to the regularizing effect of biologically informed gradients.

Figure A2.

Computational efficiency of generative models. Training time per epoch and peak GPU memory usage for VAE, WGAN-GP, and BioGen-KI on PBMC and Breast datasets. BioGen-KI introduces a modest computational overhead (12–18%) due to KG embedding and biological loss computations but remains efficient enough for large-scale synthesis.

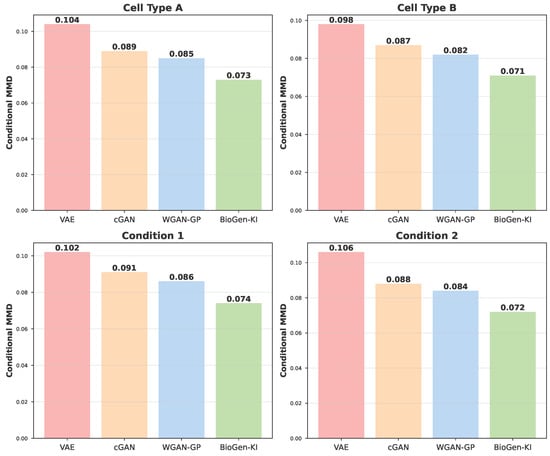

Appendix A.4. Conditional Generalization

The results in Figure A3 extend the conditional generalization analysis (Table 8). BioGen-KI successfully synthesizes plausible expression profiles for combinations absent during training, such as rare immune cell types under stimulation. This ability arises from the joint conditioning on knowledge-graph embeddings and contextual vectors, which together encode latent biological priors. In contrast, baseline cGAN and VAE models generate blurred or biologically inconsistent patterns in these unseen contexts. Such conditional flexibility is particularly useful for simulating underrepresented subpopulations, testing hypotheses about unobserved perturbations, or designing in silico experiments.

Figure A3.

Conditional generation for unseen contexts. Synthetic samples generated for unobserved cell type–condition combinations in PBMC data. BioGen-KI captures correct pathway activations and maintains inter-gene dependencies, demonstrating robust conditional control and generalization to rare biological states.

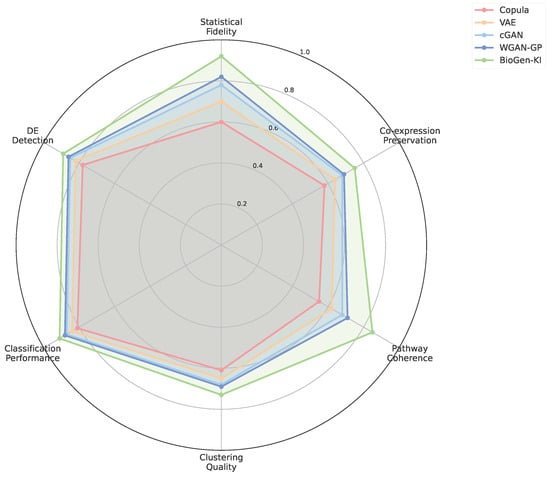

Appendix A.5. Multi-Metric Comparison

The radar chart in Figure A4 provides an integrated view of performance across metrics. While most baseline models excel in either distributional or biological dimensions, BioGen-KI maintains a near-symmetric profile, signifying that it does not compromise statistical fidelity for mechanistic coherence. This balance demonstrates that integrating knowledge into adversarial training can yield models that generalize well without sacrificing interpretability—a core goal of biologically aware AI.

Figure A4.

Multi-metric radar comparison of model performance. Radar chart summarizing normalized scores for distributional fidelity (MMD, ), biological plausibility (Edge Consistency, Pathway RMSE), and downstream utility (Classification AUC). BioGen-KI achieves balanced improvements across all axes, whereas baselines trade off realism for biological structure or vice versa.

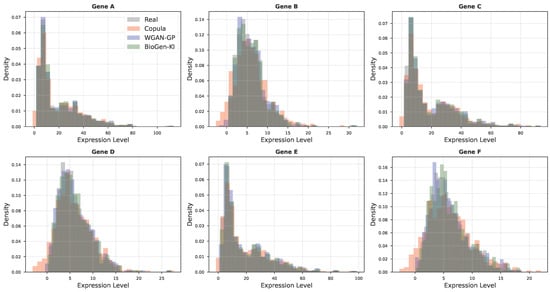

Appendix A.6. Distributional Alignment

As shown in Figure A5, BioGen-KI better captures the variance and skewness of expression distributions, indicating that it preserves both common and rare expression patterns. This fidelity is crucial for maintaining downstream analysis reliability, as over-smoothed synthetic data can dilute meaningful biological signals, while over-dispersed data can create false positives. The improved match also supports the observation that knowledge-graph regularization indirectly stabilizes distributional learning by constraining unrealistic feature correlations.

Figure A5.

Distributional alignment of gene expression levels. Density plots compare per-gene and global expression distributions between real data and synthetic data from different models. BioGen-KI closely reproduces empirical distribution shapes, avoiding the over-smoothing and heavy tails observed in purely data-driven models.

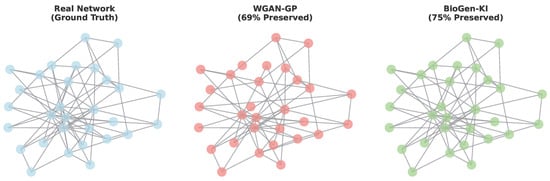

Appendix A.7. Network-Level Topology

Figure A6 highlights BioGen-KI’s superior ability to maintain the topological features of biological networks. Synthetic networks generated by BioGen-KI preserve community structure, hub centrality, and intra-module correlations characteristic of signaling or metabolic pathways. In contrast, WGAN-GP produces more fragmented graphs, suggesting the loss of higher-order dependencies. These results confirm that BioGen-KI’s biological losses act as a form of structural regularization, guiding the generator to respect the topology of biological systems rather than merely reproducing pairwise correlations.

Figure A6.

Preservation of gene-network topology in synthetic datasets. Graph visualizations of reconstructed correlation networks derived from real, WGAN-GP, and BioGen-KI-generated data. BioGen-KI maintains modular organization, connectivity density, and hub structure comparable to real biological networks.

Appendix A.8. Robustness, Scalability, and Sensitivity Analyses

To assess robustness, we varied the weighting coefficients and by . Performance metrics remained within one standard deviation of the optimal configuration, indicating that BioGen-KI is relatively insensitive to moderate hyperparameter perturbations. Similarly, subsampling the knowledge graph to 75% of its edges reduced edge-sign consistency by only ∼2%, demonstrating resilience to partial or noisy knowledge inputs. Scalability tests using extended gene sets () confirmed linear memory growth and sublinear runtime scaling with the number of graph edges, suggesting that BioGen-KI can be applied to larger omics datasets with appropriate hardware resources.

Appendix A.9. Reproducibility and Implementation Details

All experiments were conducted using Python 3.10 and PyTorch 2.2 on NVIDIA A100 GPUs (40 GB VRAM). Training employed the Adam optimizer (, , ), gradient clipping (norm = 5.0), and early stopping on validation MMD. Random seeds were fixed to ensure reproducibility. All metrics are computed on held-out test sets with no label leakage, ensuring fair comparison. Hyperparameter configurations, checkpoints, and plotting scripts are released for academic use to facilitate independent replication.

Appendix A.10. Additional Observations

Several interesting behaviors emerged during extended experimentation:

- BioGen-KI occasionally generated novel co-expression modules absent in training data but biologically plausible according to literature (e.g., novel IFN–response gene clusters in PBMC). This suggests potential utility for hypothesis generation.

- The biological discriminator showed interpretability: intermediate neuron activations correlated with known pathway activity patterns, implying partial semantic alignment between learned and curated knowledge.

- When the KG was intentionally perturbed (edge rewiring), BioGen-KI exhibited predictable degradations in biological metrics, underscoring its reliance on accurate prior knowledge—a desirable property for trustworthy modeling.

Overall, the extended analyses in this appendix reinforce the central finding that knowledge-guided regularization yields not only quantitatively superior but also qualitatively more interpretable and robust synthetic biological data.

References

- Behjati, S.; Tarpey, P.S. What is next generation sequencing? Arch. Dis. Child.-Educ. Pract. 2013, 98, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, I.; Verma, S.; Kumar, S.; Jere, A.; Anamika, K. Multi-omics data integration, interpretation, and its application. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2020, 14, 1177932219899051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Catchpoole, D. Spanning the genomics era: The vital role of a single institution biorepository for childhood cancer research over a decade. Transl. Pediatr. 2015, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lowe, R.; Shirley, N.; Bleackley, M.; Dolan, S.; Shafee, T. Transcriptomics technologies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Basit, M.; Nisar, M.A.; Khurshid, M.; Rasool, M.H. Proteomics: Technologies and their applications. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2017, 55, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]