Abstract

Tuberculosis is a serious public health issue. It is the most prevalent cause of death from a single infectious agent and globally, it is among the top 10 causes. One of the most crucial strategies to combat the TB pandemic is to administer basic anti-TB treatment for at least six months. However, the long duration of TB therapy raised the issue of non-adherence, which negatively impacted the clinical and public health outcomes of TB treatment. As a result, directly observed therapy has been used as a standard method to encourage adherence to anti-TB medication. However, this strategy has been challenged because of the difficulty, stigma, decreased economic output, and decreased quality of life, all of which might eventually make adherence problems worse. Furthermore, there is disagreement regarding the efficacy of the directly observed treatment (DOT) strategy in enhancing anti-TB adherence. Digital technology might therefore be a key tool to enhance DOT implementation. The World Health Organization Multidimensional Adherence Model (WHO-MAM) may be used with digital technologies to further improve drug adherence and change behavior. Aim: This paper aimed at reviewing the latest evidence on TB drug non-adherence, its contributing factors, the efficacy of DOT and its alternatives, and the use of digital technologies and WHO-MAM to improve medication adherence. This report analyzed linked publications using a narrative review process to address the study goals. Conventional DOT has several drawbacks when it comes to TB therapy. Medication adherence may be enhanced by incorporating WHO-MAM into the creation of digital technologies. To address several challenges associated with DOT implementation, digital technology offers a chance to enhance drug adherence.

1. Introduction

The infectious disease tuberculosis (TB) is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2024) [1] and Daily Maverick [2], about 33% of TB deaths globally occur in Africa. In 2022, the WHO projected that of the 1.3 million people affected with TB globally, 424,000 deaths will take place in Africa [3]. This figure represents more than one-third of all TB-related deaths worldwide. TB is considered a major worldwide public health problem, ranking in the top 10 causes of death and being the leading cause of mortality from a single infectious agent [3]. In 2021, of the global estimate of 10.6 million people, 1.6 million who had TB 187,000 were also HIV-positive [3].

The WHO report of 2022 states that there were 4.5% more TB cases than in 2020 [4]. Litvinjenko et al. (2023) stated that recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses revealed that around 25% of people worldwide may have TB [5]. According to these evaluations, there is a substantial number of infected individuals, constituting a substantial source of active TB transmission. The WHO TB report of 2024 [6] revealed that a typical course of TB treatment would involve six months of therapy, which includes a combination of four antibiotics, namely isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. This therapy is successful in eliminating TB infections and stopping its spread, as recommended by the WHO (2024) [7].

According to Naranya Health (2023) [8], a combination of medicines that either kill or stop the development of bacteria is the recommended standard therapy for TB, which successfully controls the condition. Patients must take their TB medicine as directed for the length of therapy, as stressed by Monique and Ilse (2022) [9]. Drug resistance and treatment failure might result from skipping doses or quitting the medicine too soon [9]. Pietersen et al. (2023) [10] discuss the recommended TB treatment plan being essential due to the bacteria’s environmental adaptability. The same author argues that one missed dosage significantly increases the risk of contracting drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis [10]. Treatment lost to follow-up (TLFU) can result in extended infectiousness, which increases the risk of treatment failure, relapses, and mortality in addition to the development of drug resistance, according to Pietersen et al. (2023) [10]. According to WHO recommendations from 2003 [11], TLFU from TB treatment may result from a wide range of factors that fall into the following five categories: (1) sociodemographic factors, (2) patient-related factors, (3) TB disease and other health-related factors, (4) healthcare and system determinants, and (5) treatment-related factors.

Treatment non-adherence is still prevalent despite the recognition of these TLFU risk factors, especially in poor nations like Ethiopia and Nigeria, where TB TLFU rates in 2021 were reported to be 20.9% (Kimani et al., 2021) [12] and 30.5% (Iweama et al., 2021) [13], respectively. For the course of therapy, patients must take their TB medicine as directed, according to the National Department of Health (NDoH) (2023) [14].

Drug resistance and treatment failure might result from skipping doses or quitting the medicine too soon. According to the NDoH, alternate treatment regimens, such as 6-month regimens combining medications like bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, and moxifloxacin, may be utilized in some circumstances, such as with multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) or rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB) [14]. The 6-month BPaLM regimen is the recommended course of treatment for most patients with MDR/RR-TB, according to a WHO 2024 study [7], based on an analysis of the most recent data.

Implementing directly observed therapy (DOT) posed significant challenges to treatment adherence and outcomes. Although the WHO introduced this strategy to ensure treatment adherence, the approach has been associated with substantial inconvenience to patients and healthcare workers (Gackowski et al., 2024) [15]. Furthermore, Sazali et al. (2022) [16] argue that a review of various studies has found no rigorous, supportive evidence of the effectiveness of DOT in improving adherence and TB treatment outcomes. Hence, applying a patient-centered approach might be improved through global access to the internet and communication technology. This will provide an excellent opportunity to overcome various challenges in TB management. This article aims to update evidence available on the definition of non-adherence to anti-TB medications, factors contributing to medication non-adherence, the effectiveness of DOT and its alternatives, and the application of the World Health Organization Multidimensional Adherence Model (WHO-MAM) to improve medication adherence.

WHO has promoted short-course directly observed treatment (DOTS) as the globally recommended TB control strategy since the mid-1990s. A WHO report from 2024 [7] further emphasizes its importance. DOTS is a comprehensive strategy that includes five key components, including government commitment, case detection through microscopy, standardized treatment with direct observation, a regular drug supply, and a monitoring and reporting system.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

The present literature review was conducted using the narrative review approach. The research was conducted to assess non-adherence to anti-TB medications, factors contributing to medication non-adherence, the effectiveness of DOT and its alternatives, and the application of the World Health Organization-Multidimensional Adherence Model (WHO-MAM) to improve medication adherence.

2.2. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

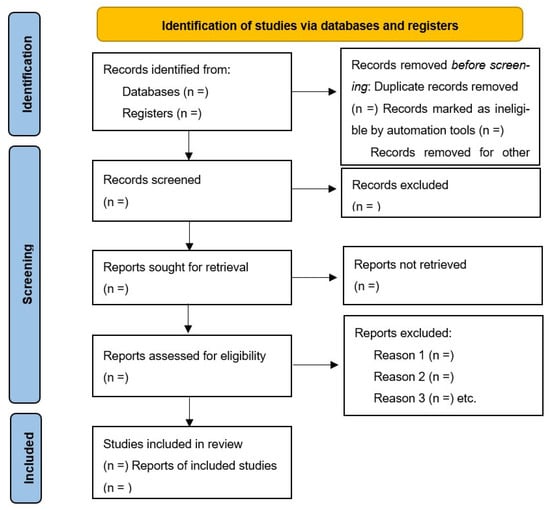

The search was carried out using the recommended Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). According to Page et al. (2021) [17], the PRISMA statement provides a guideline for transparently reporting the methods and findings of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PRISMA includes a 27-item checklist and a flow diagram to help authors report their work. PRISMA aims to improve clarity, transparency, and the quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review.

Four electronic databases—PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library—were used to identify relevant studies published between 2020 and 2025.

This article review’s objective was to find the most recent data on TB medication non-adherence, its contributing variables, the effectiveness of DOT and its substitutes, the use of digital technologies, and the WHO-MAM in enhancing medication adherence. Consequently, the search term was used to locate articles about the definition of non-adherence, the causes that are linked to it, the effectiveness of DOT and its substitutes, and the use of digital technologies and the WHO-MAM to enhance adherence to TB treatment. The following was the first search string: “medication” AND “tuberculosis” AND “non-adherence” OR “default” OR “loss to follow-up”. “default” OR “loss to follow-up” OR “non-adherence” AND “tuberculosis” AND “factors” OR “predictors” was the search string used to find articles on the factors linked to non-adherence to medicine.

To find publications about the efficacy of DOT and its alternatives, the following search term was used: (“DOT” OR “directly observed therapy” OR “VOT” OR “video observed therapy”) AND (“effectiveness” OR “feasibility” OR “acceptability”). In order to find articles about the use of digital technology, the following criteria were used: (“application”) AND (“digital technology”) AND (“adherence” OR “medication adherence”). The following search technique was employed to find papers that described the WHO-MAM’s ability to predict medication adherence: (“Medication Adherence Model” OR “WHO-MAM”) AND (“adherence” OR “medication adherence”). The relevance of the review’s parts was then assessed by screening each recognized item based solely on its title and abstract.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they were published between 2020 and 2025 and were full-text, peer-reviewed articles. Only studies on TB medication non-adherence, its contributing variables, the effectiveness of DOT and its substitutes, the use of digital technologies, and the WHO-MAM in enhancing medication adherence were considered.

Eligible studies included observational studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or systematic reviews. Additionally, studies had to be published in English and involve human subjects.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Articles written in languages other than English and conference abstracts that were available were excluded, as full-text access was necessary for quality assessment. Letters to the editor, publications without a measurement of the outcome of interest, unpublished papers, and animal experiments were all excluded. Studies were also excluded if articles were outside the scope of non-adherence to TB treatment. Studies that did not focus specifically on the WHO-MAM in enhancing TB medication adherence, duplicate studies, and conference papers were excluded. Additionally, any pilot studies published before 2020 were excluded to maintain consistency with the stated selection criteria.

3. Definition of Anti-TB Medication Adherence

According to Stewart et al. (2022) [18], adherence is defined and evaluated differently in each research study and is often customized to evaluate certain therapies. Panahi et al. (2022) [19] provided support for the idea that there is no universally accepted definition of how well a patient is adhering to their therapy, making comparisons and generalizations challenging. Various definitions of TB medication adherence according to different types of studies are summarized in Table 1 [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Table 1.

Definition of adherence from different studies.

According to Stewart et al. (2022) [18], adherence may also be hampered by limited access to medical services, such as primary care, specialists, and pharmacies. A person’s capacity to obtain essential care and follow treatment recommendations may be hampered by elements such as lack of insurance, restricted appointment availability, and distance to medical facilities. Participants are unlikely to stick to their medicine and care visits when they have trouble receiving medical care and services, as thoroughly explained by Lagu and others (2022) [26].

Some studies define TB drug adherence as a percentage of recommended doses taken (e.g., at least 95% during a 30-day period, or >80%), as noted by Charalambous et al. (2024) [27]. Others define non-adherence as skipping at least one dosage every day, or they concentrate on taking all prescribed prescriptions (“full adherence”). As stated by Religioni et al. (2025) [28] adherence is the degree to which a patient’s past drug use aligns with the recommended course of treatment.

3.1. Percentage of Doses Taken

Chapman and Chan (2025) [29] state that patients are generally categorized as adherent or non-adherent to medication regimens based on a percentage threshold, most commonly 80% or 90%. The above statement was supported by Qiao et al. (2020) [30], who agreed that this percentage, often derived from methods like the proportion of days covered (PDC) or the medication possession ratio (MPR), indicates the proportion of days a patient has access to or takes their medication. A PDC or MPR of 80% or higher generally signifies adherence, while values below this threshold are considered non-adherent.

3.2. Full vs. Non-Adherence

Some studies distinguish between non-adherence (missing at least one daily dosage during a given time frame, such as four or thirty days) and complete adherence (taking all prescribed prescriptions). Prescription adherence, as suggested by Chauke and colleagues (2022) [31], often refers to adherence as whether patients continue to take a given prescription and whether they take it as directed (e.g., twice daily). Clinicians, healthcare systems, and other stakeholders (such as payers) are becoming more concerned about medication non-adherence due to accumulating evidence that it is common and linked to negative outcomes and increased healthcare expenditures.

3.3. WHO Definition

According to the WHO, adherence is the degree to which a patient’s past drug use aligns with the recommended course of treatment. The WHO’s definition of adherence is appropriately reflected in the statement, as attested by Religioni et al. (2025) [28]. In the context of medicine, adherence refers to how closely a patient’s behavior, including taking their medications, follows advice from a healthcare professional. This is a wide notion that includes many treatment-related facets of patient behavior.

3.4. Other Factors

To evaluate adherence, some studies additionally consider variables like missing visits, the application of TB treatment adherence measures, or treatment results. Missing appointments, whether for TB treatment or associated tests, is a strong signal of non-adherence and can have a detrimental influence on treatment outcome, according to Izudie et al. (2024) [32]. According to studies, skipping several sessions, especially during the early phases of therapy, might increase the chance of unfavorable outcomes including death, treatment failure, or being forgotten for follow-up.

3.4.1. Time to Discontinuation

The time-to-discontinuation approach, which measures how long a patient continues a medication, can be used to assess adherence. Shorter time intervals between starting and stopping a medication generally indicate poorer adherence (Burnier, 2024) [33]. Murali et al. (2022) [34] define the medication possession ratio (MPR) as a dichotomous variable that looks at “the time between prescription refills from the perspective of time gaps (periods of non-adherence) or consumption (medication availability, the days’ supply/days between refills)” and classifies “patients as either compliant or noncompliant based on criteria such as a specified treatment gap”.

3.4.2. Dynamic Measures

According to a study performed by Stewart et al. (2022) [18], adherence may also be dynamically assessed using a variety of techniques, including pill counts, surveys, and punctuality at visits. There are several methods for evaluating adherence. In general, they can be categorized as either direct or indirect. Direct approaches include testing for the presence of medication or a metabolite in blood, urine, or other body fluids. To provide an evaluation of adherence, indirect approaches employ techniques including patient self-reporting, pill counts, prescription reordering, pharmacy refill records, electronic medication monitoring, and therapeutic impact rather than measuring the presence of the medication.

A guideline development group (GDG) [35] is a multidisciplinary team of experts assembled to create, update, or review guidelines in the context of healthcare or public health. The most accessible way to report adherence in a clinical setting is by self-reporting. To suggest how practitioners should use self-reporting, the GDG sought to weigh the benefits and drawbacks of this approach in standard clinical settings. To investigate the benefits and drawbacks of using self-reporting to gauge adherence, an evidence-based review was carried out. The author did not investigate other kinds of adherence metrics.

4. Factors Contributing to Anti-TB Medication Adherence

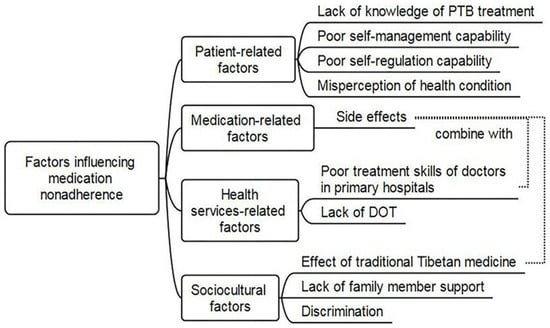

According to Grigoryan et al. (2022) [36], adherence to anti-TB medicine might be influenced by several variables. These include aspects pertaining to the patient, medication, health, therapy, and sociocultural factors, as presented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Factors influencing TB-treatment non-adherence.

4.1. Patient-Related Factors

4.1.1. Knowledge and Beliefs

According to research by Ozaltun and Akin (2024) [37], patients’ propensity to take medication as directed can be greatly impacted by their knowledge about tuberculosis, its treatment, and the significance of adherence. A patient’s propensity to take medicine as prescribed is greatly influenced by their knowledge of tuberculosis, its treatment, and the need to follow the recommended drug schedule. Awareness of the contagiousness of tuberculosis, the possibility of treatment cures, and the repercussions of non-adherence, including medication resistance and prolonged infectiousness, are all part of this comprehension.

4.1.2. Social Support

Shahin et al. (2021) [38] claim that social support such as that from peers, family, and the community can help patients stick to their treatment plans by offering reminders and encouragement. Useful support thereby enables patients to adhere to their treatment regimens more effectively. Therefore, it may be necessary for healthcare practitioners to consider whether patients have the right kind of social support in a setting that will help them follow and benefit from treatment suggestions.

4.1.3. Perceived Barriers

According to Appiah et al. (2023) [39], there are several variables that might lead to non-adherence to TB treatment, including the stigma associated with the disease, pharmaceutical side effects, forgetfulness, and belief that one’s health has improved after the initial intense period. Both separately and in combination, these elements make it difficult for patients to finish their whole prescription regimen. Treatment side effects were identified in this investigation as an additional obstacle to TB treatment compliance. According to Appiah et al. (2023) [39], several patients stopped taking their TB medication due to side effects like the tiredness, hunger and nausea they experienced, according to patient feedback. These side effects were significant enough for some individuals to discontinue treatment without medical advice.

A study conducted in Ghana by Manu et al. (2024) [40] found that unpleasant side effects like tiredness, hunger, and nausea were severe enough for some individuals to stop taking medication without consulting a doctor. These side effects were particularly problematic when they interfered with daily activities and the ability to work. The study, performed at the ART unit of the Volta Regional Hospital in Hohoe, Ghana, highlighted the challenges patients faced due to these side effects.

Manu et al. (2024) [40] reported similar research in Ghana, Bahta et al. (2020) [41] reported in Eritrea, and Pradipta et al. (2021) reported in Indonesia [42]. In this study, the most common adverse effects that discouraged some patients from stopping their therapy were tiredness and excessive appetite. It is recommended that patients be made aware of the typical adverse effects they should expect and what to do if they materialize.

According to Kigozi-Male et al. (2024) [43], psychological discomfort, which includes stress, worry, and depression, is a social component for TB adherence medicine and may have a substantial influence on a patient’s capacity and willingness to follow a treatment plan. Attending appointments, adhering to dietary restrictions, and taking medications on a regular basis may be challenging due to these illnesses. Authors DiMatteo et al. (2000) [44] state that determining the degree to which noncompliance may be a symptom of a treatable illness like depression or anxiety may be a crucial first step in enhancing patient adherence, the therapeutic alliance between doctors and patients, and eventually the results of medical treatment.

4.2. Health System Factors

4.2.1. Organization of Treatment

A qualitative study conducted by Appiah et al. (2023) [39] concluded that the way TB treatment is organized, including the frequency of visits, the complexity of the regimen, and the availability of services, can affect adherence. The organization of TB treatment, encompassing visit frequency, regimen complexity, and service availability, significantly impact adherence. Factors like the burden of daily clinic visits in DOTS, the complexity of medication regimens, and challenges accessing healthcare services can all hinder patient adherence.

A WHO report from 2007 [45] further emphasizes the importance of DOTS as a comprehensive strategy that includes five key components, including government commitment, case detection through microscopy, standardized treatment with direct observation, a regular drug supply, and a monitoring and reporting system.

4.2.2. Accessibility and Affordability

According to Aremu et al. (2022) [46], accessibility and affordability issues can have a significant influence on treatment regimen adherence. These include things like the cost of transportation, medicine, and the distance to medical facilities. These elements may serve as obstacles, making it challenging for people to receive medical treatment and take their drugs as directed. The expense of traveling to the clinic to pick up monthly refills is one such obstacle. Particularly for people who live in rural regions, the cost of transportation in relation to income can be high and must be balanced with other necessities like food, housing, and education.

Transportation expenses may be a deterrent to long-term antiretroviral therapy, according to a study performed by Gonah et al. (2020) [47]. This study, however, has not looked at the ways that transportation expenses can affect treatment retention and adherence nor how patients manage the additional financial and psychological strain that these expenses place on them.

4.3. Other Factors

4.3.1. Structural Factors

One researcher, Mike (2020) [48], concluded that socioeconomic issues, such as poverty and gender discrimination, are structural elements linked to adherence and can have a substantial influence on a patient’s capacity to stick with treatment. Access to healthcare, medicine, and proper nutrition—all essential for effective treatment—can be hampered by poverty. Unfair access to healthcare can result from gender discrimination, and women may have more difficulty sticking to their treatment plans because of social expectations and family obligations.

4.3.2. Behavioral Factors

Li et al.’s (2024) [49] contribution involved behavioral aspects associated with medication adherence. Adherence to healthy practices, such as preventative measures and medical regimens, can be greatly impacted by substance use (such as drinking and smoking) and other harmful habits. Substance abuse can impair motivation, cognitive function, and decision-making, which makes following advice more difficult.

Furthermore, certain drugs may have direct negative effects on health that make it harder to follow through. This can involve different combinations of drug use, bad eating habits, physical inactivity, and dangerous sexual activities, according to Li et al. (2024) [49]. Because the cumulative impact of several harmful behaviors can increase sensitivity to chronic illnesses, including physical and psychological health concerns, the clustering of HRBs poses serious health hazards during adolescence and later in adulthood.

4.3.3. Individual Variability

It is true that individual differences in desire and readiness to follow suggested health practices are directly related to medication adherence (Sazali et al., 2022) [16]. Whether someone will take their prescription drugs as instructed depends on several important factors, including personal beliefs, the perceived need for medication, and perceived self-efficacy. Medication adherence is a complicated human behavior that can be impacted by several factors, such as socioeconomic-, condition-, therapy-, patient-, and health system-related factors.

5. Effectiveness and Alternatives of DOT

Results from research carried out by Barreto-Duarte (2025) [50] revealed that DOT, particularly DOTS, is very successful in treating TB, with treatment success rates frequently above 90%. This approach involves a trained health worker observing patients taking their medication, ensuring adherence and improving cure rates. DOT, however, may be logistically difficult, especially in environments with limited resources. In certain situations, alternatives such as family-observed DOT and video-observed therapy (VOT) offer treatment completion rates that are comparable to those of DOTS.

5.1. Effectiveness of DOT

5.1.1. High Treatment Success

According to Olowoyo et al. (2025) [51], the DOTS strategy has been shown to significantly improve TB treatment outcomes, with success rates often reaching 90% or higher. Using this approach, TB treatment adherence is ensured to the full course of treatment, and the development of drug-resistant strains is prevented.

5.1.2. Improved Adherence

By ensuring that patients take their medications as directed, DOT lowers the chance of drug resistance and treatment failure. According to Netto et al. (2024) [23], DOT has been widely recognized as the gold standard for supervising TB treatment. Using this approach, a healthcare worker or designated individual directly observes patients as they take their prescribed TB medications. This ensures adherence to the treatment regimen and helps to prevent the development of drug-resistant strains. However, there are logistical issues with the traditional DOT strategy, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), as concluded by Netto et al. (2024) [23], who found that these areas were where most TB infections occur. These issues include significant time and resource commitments from patients and healthcare professionals.

5.1.3. Cost-Effectiveness

According to the WHO (2013) [52], it is accurate that the WHO, World Bank, and GiveWell have recognized the DOTS strategy as highly cost-effective in reducing tuberculosis mortality, particularly in resource-limited settings.

5.1.4. Benefits for Vulnerable Populations

As discussed by Ezelote et al. (2024) [53] in their research, DOTS in which a medical practitioner watches patients take their prescriptions is especially beneficial for those who are at risk of non-adherence, such as those who are homeless or living with HIV. Maintaining high levels of adherence may need extra therapy (for example, mental health or drug use) and social support. ART has been successfully administered by DOT to individuals who are currently abusing drugs but not to members of the general clinic population or in home-based settings with DOT-responsible partners.

The incentives or prizes to promote adherence have been studied by Zhu et al. (2025) [54], who found that they can reduce viral load in one study that requires regular viral load testing and incentives. Adherence was also improved in another study conducted by the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN). Even while financial incentives have limited durability and practicality and behavior modification is usually not sustained after the incentives are eliminated, the HPTN trial did find some sign of durable adherence after nine months.

5.2. Alternatives to DOT

With the development of digital technology, VOT has become a viable substitute that enables medical professionals to remotely watch patients take their prescription drugs (Ridho et al., 2022) [55].

5.2.1. Video-Observed Therapy (VOT)

Netto et al. (2024) [23] state that VOT provides a remote substitute for regular DOT by enabling medical professionals to watch patients take their medications through video chats. Research has indicated that VOT can attain comparable treatment effectiveness and adherence rates to DOTS. VOT can attain similar adherence rates and treatment success outcomes to DOT, according to several studies. VOT has several benefits, such as cutting expenses and travel time and possibly raising patient satisfaction.

Research performed by Chen et al. (2023) [56] revealed that both VOT strategies resulted in high rates of patient acceptance and adherence. VOT reduced travel time for TB program personnel and/or patients while maintaining excellent patient satisfaction, which increased program efficiency as compared to in-person DOT. To find out how VOT influences TB treatment outcomes, such cures and recurrence, more studies with longer follow-up times are required. When using any or both VOT approaches to offer patient-centered care, individual patient, provider, and program concerns should be considered.

5.2.2. Family-Observed DOT

Family members can be trained to watch patients take their medications in settings with limited technology (Mbunge et al. 2022) [57]. Family members can be taught to watch patients take their medications in situations with limited resources when technology for medication adherence assistance is not accessible. Medication errors can be avoided, medication compliance can be enhanced, and patients can receive their recommended dosages thanks to this training.

ScienceDirect.com states that family members can be trained to observe patients taking their medication but also that medication adherence is a key area where digital health technologies can be utilized. A study conducted by Rosu et al. (2023) [58] concluded that family-observed DOT can be as effective as traditional DOT in treating TB, with comparable treatment success rates. This approach involves a family member supervising medication intake, which can reduce the burden on healthcare facilities and stigma associated with daily clinic visits.

5.2.3. DOTS (Medication Monitoring)

Authors Mbunge et al. (2022) [57] state that medication monitoring entails keeping an eye on medication adherence using a variety of technologies, including electronic devices and pill-taking monitors. For doctors to keep track of adherence data, patients submit a free call each time they take their medicine. There are no extra fees for patients because the calls are toll-free. Most patients have access to a mobile phone and can make a call, so DOTS reaches the maximum number of users.

5.2.4. Community-Based DOT

A group of authors led by Wong et al. (2023) [59] suggested CB-DOT as an approach that involves healthcare providers or community health workers delivering DOT in the patient’s community rather than solely at a clinic. CB-DOT is a TB treatment strategy where patients take their medications while being observed by community health workers or volunteers, often at home or in a community setting. It is a person-centered approach that aims to improve adherence to treatment, especially in decentralized or rural areas. CB-DOT may offer increased treatment success and is often more cost-effective than traditional clinic-based DOT.

Poor treatment results and extended infectivity can result from noncompliance with TB treatment. As DOT aims to enhance adherence to TB therapy by monitoring patients as they take their anti-TB medicine, Wong et al. (2023) [59] maintain their position. Despite extensive research and promotion, the efficacy of CB-DOT initiatives has been mixed.

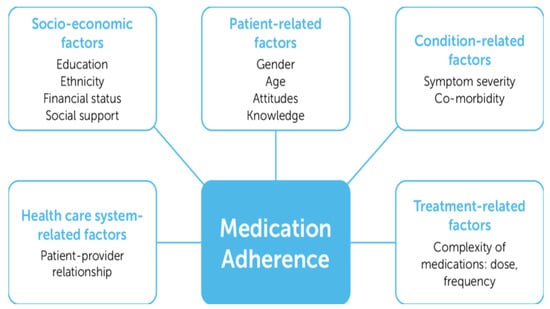

6. Multidimensional Adherence Model of WHO

According to the WHO (2018) [60], anti-TB drug adherence is a complicated and multifaceted problem that calls for a person-centered approach to care. This entails not using a one-size-fits-all strategy but rather understanding the unique requirements and circumstances of every patient. Enhancing TB patients’ drug adherence, particularly considering emerging technology, necessitates a multipronged strategy that considers both patient behavior and the usefulness of digital tools. In their research, Strike et al. (2020) [61] advised using the WHO-MAM, which is relevant to medication adherence.

WHO-MAM to Improve Adherence

A useful framework for comprehending several elements impacting adherence, such as patient perceptions, beliefs, social environment, and the pragmatics of therapy, is the WHO-MAM (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The World Health Organization Multidimensional Adherence Model.

Marin et al. (2024) [62] propose that it is crucial to understand the multidimensional model because the WHO model recognizes that adherence is not solely a matter of patient compliance but also involves factors like perceived benefits and barriers, social support, and the patient’s overall health beliefs.

According to Ukoaka et al. (2024) [63], digital tools like VOT, SMS reminders, and smartphone applications can significantly improve medication adherence by providing real-time monitoring, timely reminders, and personalized support. These technologies help patients stay on track with their medication schedules and can be particularly useful in managing chronic conditions like TB and HIV. Additionally, by tracking medicine consumption, sending out targeted reminders, and promoting contact between patients and healthcare professionals, these digital technologies may be utilized to improve adherence.

Although DOT required someone to physically watch the patient take their medication to monitor adherence, Ukoaka et al. (2024) [63] and the WHO (2019) [64] talk about how the introduction and spread of digital technologies have made a variety of remote support options available. These alternatives could be less expensive and provide the advantages of therapeutic assistance that self-administered therapy (SAT) does not. Automated medicine reminders are one advantage that digital devices can provide over traditional methods, as proposed by Vilyte et al. (2023) [65]. Automated dosage history compilation, improved triage, follow-up identification, and possible cost savings for the TB patient are all reasons for these reminders.

As part of the WHO-MAM, social context and the absence of stigma as stated by Morse et al. (2020) [66] can significantly impact adherence. Digital tools can facilitate access to support networks and address stigma by providing a platform for communication and information sharing. Furthermore, practical considerations of the WHO-MAM model, as suggested by Strike et al. (2020) [61], also consider the practical aspects of treatment, such as the complexity of the regimen, cost, and access to healthcare services. Digital tools can help streamline the treatment process, reduce costs, and improve access to care. The WHO-MAM is an ecological model that examines how various factors, including these practical elements, can impact adherence to treatment recommendations.

According to Schmidt et al. (2020) [67], complexity of drug treatment is known to be a risk factor for administration errors and nonadherence promoting higher healthcare costs, hospital admissions and increased mortality. Bell et al. (2025) [68] emphasized that the number of drugs and dose frequency are parameters often used to assess complexity related to the medication regimen. The WHO-MAM acknowledges that the complexity of the regimen itself can be a barrier to adherence. The Pharmacy Programs Administrator (2024) [69] argues that patients are often identified for referrals for medication reviews based on the complexity of their treatment regimen.

Authors Pattani et al. (2025) [70] confirm that regimen complexity has been associated with non-adherence, hospitalizations, and medication errors. Patients with three or more medical conditions, who experience difficultly self-administering specific formulations (e.g., inhalers, eye drops, transdermal patches) or who have other difficulty self-managing their medication regimen, are thought to benefit from medication review.

The cost of treatment, including medication and transportation to healthcare appointments, is a significant barrier to the WHO-MAM (Malnutrition and Anemia Management) programs, particularly for individuals with low incomes. This financial burden can prevent people from accessing necessary care and adhering to treatment plans, ultimately impacting their health outcomes. Cost is another important aspect of the WHO-MAM, as concluded by Biddell et al. (2023) [71], who stated that the cost of medication, transportation to healthcare appointments, and other expenses associated with treatment can be a significant barrier, particularly for individuals with low incomes. The WHO-MAM recognizes that financial constraints can impact a person’s ability to adhere to treatment.

Anawade et al. (2024) [72] stated that a comprehensive understanding of healthcare access requires considering the interplay between the healthcare system’s structure, individual characteristics, and the processes involved in receiving care. This involves examining factors related to availability, affordability, accessibility, acceptability, and accommodation within the healthcare system, as well as predisposing and enabling factors at the individual level and how these elements influence the actual utilization of services.

7. Potential of Digital Technology in Medication Adherence

Digital technologies offer significant potential to improve medication adherence by providing tools that track adherence, monitor physiological conditions, and offer personalized support. These technologies can be used to enhance traditional approaches, such as pill counts and pharmacy records, and can even include cutting-edge options like smart pills and wearables. As suggested by Adindu et al. (2024) [73], by incorporating digital tools, healthcare systems can improve adherence rates, reduce stigma, and foster more efficient and patient-centered care.

Over half of the world’s population is online, according to the Global System for Mobile Association (GSMA) report (2014) [74]. However, the GSMA reports that mobile internet is a major driver of global connectivity, with a large portion of the world’s population now using mobile devices to access the internet. This claim is accurate for mobile internet specifically, even though not all internet users access it through mobile devices.

More precisely, according to GSMA statistics [74], a little over 4 billion people, or more than half of the world’s population, used mobile internet in 2021. With 94% of the population now connected to a mobile broadband network, this number indicates a notable rise in the use of mobile internet. With a significant amount of the global population increasingly utilizing mobile devices to access the internet, the overall trend is that mobile internet connection is increasing, even though the precise proportion may differ slightly depending on the source and the year of the data.

8. Limitations of Video Observed Therapy

The advancement of digital intervention may not only pave the way for changes and new opportunities but could potentially raise several issues, primarily technical and ethical dilemmas.

The use of VOT might not be equally accessible for those who are from a low socioeconomic background. The limitation might range from low smartphone access, low mobile internet subscription, limited internet connection, and low smartphone proficiency. Therefore, socioeconomically disadvantaged people do not have equitable access to the needed intervention.

In terms of technicality, it is assumed that using VOT can subsequently reduce face-to-face contact. Thus, it raises a patient safety issue, whereby the patient condition might be missed if they develop anti-TB drug toxicity. Therefore, developing a strategy to maintain patient safety while adapting to new technology is essential.

Operability and usability are essential considerations in adopting new digital interventions. Operability is a measure of how well a new system works when operating. Meanwhile, acceptability refers to the user’s experience when interacting with a product or system, including websites, software, devices, or applications. Therefore, prior training for the related staff and a pilot study should be conducted before the digital intervention is implemented on a large scale.

9. Conclusions

A key conclusion from this review article is that integrating digital technology and the WHO-MAM can be a powerful strategy for improving medication adherence in TB patients. This approach leverages the benefits of digital tools while addressing complex factors influencing patient behavior and adherence, as outlined in the WHO-MAM.

The WHO-MAM acknowledges that adherence is influenced by various factors, including the patient, health system, and condition-related aspects. Integrating digital technology and the WHO-MAM allows for a more comprehensive approach to addressing these factors, leading to improved adherence. Tuberculosis medication adherence is challenging due to a number of issues with the DOT as it is currently applied. To address a number of challenges associated with DOT implementation, digital technology offers a chance to enhance drug adherence.

Using the WHO-MAM might offer a deeper knowledge of patients’ general health views. In essence, the review article suggests that combining the power of digital technology with a framework like the WHO’s multidimensional model can be a crucial step in combating TB and achieving better patient outcomes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data to declare for this was a review article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. World TB Day: Key Facts. WHO, 2024. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/tuberculosis-tb (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Daily Maverick. South Africa’s TB Crisis: Progress and Challenges Highlighted in Latest WHO Report. WHO, 2024. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2024-10-31-sa-records-56000-tb-deaths-in-2023-says-who (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020 [Internet]; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013131 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Pan American Health Organization-World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Deaths and Disease Increase During the COVID-19 Pandemic. PANO-WHO 2022. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/27-10-2022-tuberculosis-deaths-and-disease-increase-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Litvinjenko, S.; Magwood, O.; Wu, S.; Wei, X.; Wei, X. Burden of tuberculosis among vulnerable populations worldwide: An overview of systemic reviews. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Treatment. TB Alert. WHO Tuberculosis Report 2024. Available online: https://www.tbalert.org/about-tb/what-is-tb/treatment (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis: Multidrug-Resistant (MDR-TB) or Rifampicin-Resistant TB (RR-TB) Multidrug-Resistant-Tuberculosis-(mdr-tb). WHO 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/tuberculosis (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Narayana Health. Tuberculosis of the Kidney: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options. Narayana Health 2023. Available online: https://www.narayanahealth.org/blog/tuberculosis-of-the-kidney-symptoms-diagnosis-and-treatment-options (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Monique, O.; Du Preez, I. Factors contributing to pulmonary TB treatment lost to follow-up in developing countries: An overview. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 1, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietersen, E.; Anderson, K.; Cox, H.; Dheda, K.; Aihua Bian, A.; Shepherd, B.E. Variation in missed doses and reasons for discontinuation of anti-tuberculosis drugs during hospital treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2023, 8, e0281097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment. WHO 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240007048 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Kimani, E.; Muhula, S.; Kiptai, T.; Orwa, J.; Odero, T.; Gachuno, O. Factors influencing TB treatment interruption and treatment outcomes among patients in Kiambu County, 2016–2019. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweama, C.N.; Agbaje, O.S.; Umoke, P.C.I.; Igbokwe, C.C.; Ozoemena, E.L.; Omaka-Amari, N.L.; Idache, B.M. Nonadherence to tuberculosis treatment and associated factors among patients using directly observed treatment short-course in north-west Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Department of Health. Clinical Management of Rifampicin-Resistant Tuberculosis. National Department of Health 2023. Available online: https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Updated-RR-TB-Clinical-Guidelines-September-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Gackowski, M.; Jasińska-Stroschein, M.; Osmałek, T.; Waszyk-Nowaczyk, M. Innovative Approaches to Enhance and Measure Medication Adherence in Chronic Disease Management: A Review. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e944605-1–e944605-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazali, M.F.; Rahim, S.S.S.A.; Mohammad, A.H.; Kadir, F.; Payus, A.O.; Richard Avoi, R.; Jeffree, M.S.; Omar, A.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Atil, A.; et al. Improving Tuberculosis Medication Adherence: The Potential of Integrating Digital Technology and Health Belief Model. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2022, 86, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.J.F.; Moon, Z.; Horne, R. Medication nonadherence: Health impact, prevalence, correlations and interventions. Psychol. Health 2022, 38, 726–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panahi, S.; Rathi, N.; Hurley, J.; Sundrud, J.; Lucero, M.; Kamimura, A. Patient Adherence to Health Care Provider Recommendations and Medication among Free Clinic Patients. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221077523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asriwati; Yeti, E.; Niakurniawati; Usman, A.N. Risk factors analysis of non-compliance of Tuberculosis (TB) patients taking medicine in Puskesmas Polonia, Medan, 2021. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35, S227–S230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrbashov, B.; Kulzhabaeva, A.; Kadyrov, A.; Toktogonova, A.; Timire, C.; Satyanarayana, S.; Istamov, K. Time to Treatment and Risk Factors for Unsuccessful Treatment Outcomes among People Who Started Second-Line Treatment for Rifampicin-Resistant or Multi-Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2021. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.B.B.; Carvalho de Meneze, R.; Pereira, M.A.; Rolla, V.C. Effects of missed anti-tuberculosis therapy doses on treatment outcome: A multi-center cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health 2025, 48, 101162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netto, T.A.L.; Diniz, B.D.; Odutola, P.; Dantas, C.R.; Caldeira de Freitas, M.C.F.L.; Hefford, P.M. Video-observed therapy (VOT) vs. directly observed therapy (DOT) for tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review on adherence, cost of treatment observation, time spent observing treatment and patient satisfaction. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahra, S.; Bronze, M.S. Tuberculosis (TB) Treatment & Management. Infect. Dis. 2024. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/230802-treatment (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Stagg, H.R.; Lewis, J.J. Data. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 7, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagu, T.; Haywood, C.; Reimold, K.; DeJong, C.; Sterling, R.W.; Lisa, I.; Iezzoni, L.I. I Am Not The Doctor For You’: Physicians’ Attitudes About Caring For People With Disabilities. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, S.; Maraba, N.; Jennings, L.; Rabothata, I.; Cogill, D.; Mukora, R.; Hippner, P.; Naidoo, P.; Xaba, N.; Mchunu, L.; et al. Treatment adherence and clinical outcomes amongst in people with drug-susceptible tuberculosis using medication monitor and differentiated care approach compared with standard of care in South Africa: A cluster randomized trial. Lancet 2024, 75, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Religioni, U.; Rocío Barrios-Rodríguez, R.; Requena, P.; Borowska, M.B.; Ostrowski, J. Enhancing Therapy Adherence: Impact on Clinical Outcomes, Healthcare Costs, and Patient Quality of Life. Medicina 2025, 61, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.C.E.; Chan, A.H.Y. Medication nonadherence—Definition, measurement, prevalence, and causes: Reflecting on the past 20 years and looking forwards. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1465059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.Y.; Tsang, C.C.S.; Hohmeier, K.C.; Dougherty, S.; Hines, L.; Chiyaka, E.T.; Wang, J.; Qiao, A. Association Between Medication Adherence and Healthcare Costs Among Patients Receiving the Low-Income Subsidy. Value Health 2020, 23, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauke, D.; Nakwafila, O.; Chibi, B.; Sartorius, B.; Mashamba-Thompson, T. Factors influencing poor medication adherence amongst patients with chronic disease in low-and-middle-income countries: A systematic scoping review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izudi, J.; Tamwesigire, I.K.; Bajunirwe, F. Effect of missed clinic visits on treatment outcomes among people with tuberculosis: A quasi-experimental study utilizing instrumental variable analysis. IJID Reg. 2024, 13, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M. The role of adherence in patients with chronic diseases. The role of adherence in patients with chronic diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 119, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali, K.M.; Mullan, J.; Roodenrys, S.; Cheikh Hassan, H.I.; Lonergan, M.A. Exploring the Agreement Between Self-Reported Medication Adherence and Pharmacy Refill-Based Measures in Patients with Kidney Disease. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 3465–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GPG National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (UK). Medicines Adherence: Involving Patients in Decisions About Prescribed Medicines and Supporting Adherence [Internet]. Assessment Adherence. London: Royal College of General Practitioners (UK); 2009 Jan. NICE Clin. Guidel. 2009, 76, 7. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55447/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Grigoryan, Z.; McPherson, R.; Harutyunyan, T.; Truzyan, N.; Sahakyan, S. Factors Influencing Treatment Adherence Among Drug-Sensitive Tuberculosis (DS-TB) Patients in Armenia: A Qualitative Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 2399–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaltun, C.S.; Akin, L. An Evaluation of Medication Adherence in New Tuberculosis Cases in Ankara: A Prospective Cohort Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, W.; Kennedy, G.A.; Stupans, I. The association between social support and medication adherence in patients with hypertension: A systematic review. Pharm Pr. 2021, 2, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, M.A.; Arthur, J.A.; Gborgblorvor, D.; Asampong, E.; Kye-Duodu, G.; Kamau, E.M.; Dako-Gyeke, P. Barriers to tuberculosis treatment adherence in high-burden tuberculosis settings in Ashanti region, Ghana: A qualitative study from patient’s perspective. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, E.; Sumankuuro, J.; Douglas, M.; Aku, F.Y.; Adoma, P.O.; Kye-Duodu, G. Client-reported challenges and opportunities for improved antiretroviral therapy services uptake at a secondary health facility in Ghana. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahta, M.; Berhe, T.; Russom, M.; Tesfamariam, E.H.; Ogbaghebriel, A. Magnitude, Nature, and Risk Factors of Adverse Drug Reactions Associated with First Generation Antipsychotics in Outpatients with Schizophrenia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2020, 9, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradipta, I.S.; Idrus, L.R.; Probandari, A.; Lestari, B.W.; Diantini, A.; Alffenaar, J.-W.C.; Hak, E. Barriers and strategies to successful tuberculosis treatment in a high-burden tuberculosis setting: A qualitative study from the patient’s perspective. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigozi-Male, G.; Heunis, C.; Engelbrecht, M.; Tweheyo, R. Possible depression in new tuberculosis patients in the Free State province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 39, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMatteo, M.R.; Lepper, H.S.; Croghan, T.W. Depression Is a Risk Factor for Noncompliance with Medical Treatment: Meta-analysis of the Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Patient Adherence. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 2101–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control Surveillance, Planning, Financing. Key Findings. WHO REPORT 2007. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43629/9789241563141_eng.pdf? (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Aremu, T.O.; Oluwole, O.E.; Adeyinka, K.O.; Schommer, J.O. Medication Adherence and Compliance: Recipe for Improving Patient Outcomes. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonah, L.; Moodley, I.; Hlongwana, K. Effects of HIV and non-communicable disease comorbidity on healthcare costs and health experiences in people living with HIV in Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. HIV Med. 2020, 21, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mike, J.H.M. Access to essential medicines to guarantee women’s rights to health: The pharmaceutical patents connection. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2020, 23, 473–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dessie, Y.; Mwanyika-Sando, M.; Assefa, N.; Millogo, O.; Manu, A. Co-occurrence of and factors associated with health risk behaviors among adolescents: A multi-center study in sub-Saharan Africa, China, and India. Co-occurrence of and factors associated with health risk behaviors among adolescents: A multi-center study in sub-Saharan Africa, China, and India. Eclinical Med. 2024, 70, 102525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto-Duarte, B.; Villalva-Serra, K.; Croda, J.; Arcêncio, R.A.; Maciel, E.L.N.; Andrade, B.B. Directly observed treatment for tuberculosis care and social support: Essential lifeline or outdated burden? Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2025, 43, 101015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowoyo, K.S.; Esan, D.T.; Olowoyo, P.; Oyinloye, B.E.; Fawole, I.O.; Aderibigb, S. Treatment Adherence and Outcomes in Patients with Tuberculosis Treated with Telemedicine: A Scoping Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Quality Assurance of Sputum Microscopy in DOTS Programmed: Regional Guidelines in Countries in Western Pacific. Overview. WHO 2013. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9290610565# (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ezelote, C.J.; Nwoke, E.A.; Ibe, S.N.; Nworuh, B.O.; Iwuoha, G.N.; Iwuala, C.C.; Udujih, O.G.; Osuoji, J.N.; Inah, A.S.; Okaba, A.E.; et al. Brief communication: Effect of mobile health intervention on medication time adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS receiving care at selected hospitals in Owerri, Imo State Nigeria. AIDS Res. Ther. 2024, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Guo, L.; Yang, M.; Cheng, J. The effectiveness of monetary incentives in improving viral suppression, treatment adherence, and retention in care among the general population of people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Res. Ther. 2025, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridho, A.; Alfian, S.D.; van Boven, J.F.M.; Levita, J.; Yalcin, E.A.; Le, L.; Alffenaar, J.W. Digital Health Technologies to Improve Medication Adherence and Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Tuberculosis: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e33062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.C.; Owaisi, R.; Goldschmidtc, L.; Maimets, I.; Daftary, A. Patient perceptions of video directly observed therapy for tuberculosis: A systematic review. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2023, 35, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbunge, E.; Batani, J.; Gaobotse, G.; Muchemwa, B. Virtual healthcare services and digital health technologies deployed during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in South Africa: A systematic review. Glob. Health J. 2022, 2, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosu, L.; Madan, J.; Bronson, G.; Nidoi, J.; Tefera, M.G.; Malaisamy, M.; Squire, B.S.; Worrall, E. Cost of digital technologies and family-observed DOT for a shorter MDR-TB regimen: A modelling study in Ethiopia, India and Uganda. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.J.; Thum, C.C.; Ng, K.Y.; Lee, S.W.H. Engaging community pharmacists in tuberculosis-directly observed treatment: A mixed-methods study. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2023, 24, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A Patient-Centered Approach to TB Care Centered Approach to TB Care. WHO 2018. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/272467/WHO-CDS-TB-2018.13-eng.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Strike, K.; Chan, A.; Iorio, A.; Maly, M.R.; Stratford, P.W.; Solomon, P. Predictors of treatment adherence in patients with chronic disease using the Multidimensional Adherence Model: Unique considerations for patients with hemophilia. J. Haem. Pr. 2020, 7, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, P.M.; Munyeme, M.; Kankya, C.; Jubara, A.S.; Matovu, E.; Waiswa, P.; Romano, J.S.; Mutebi, F.; Onafruo, D.; Kitale, E.; et al. Medication nonadherence and associated factors in patients with tuberculosis in Wau, South Sudan: A cross- sectional study using the world health organization multidimensional adherence model. Arch. Public Health 2024, 82, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukoaka, B.M.; Ugwuanyi, E.A.; Ukueku, K.O.; Ajah, K.U.; Udam, N.G.; Daniel, F.M.; Tajuddeen Adam Wali, T.A.; Gbuchie, M.A. Digital tools for improving antiretroviral adherence among people living with HIV in Africa. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening. WHO 2019. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/311941/9789241550505-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Vilyte, G.; Fox, T.; Rohwer, A.C.; Volmink, J.; McCaul, M. Digital devices for Tuberculosis treatment adherence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023, CD015709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, R.M.; Myburgh, H.; Reubi, D.; Archey, A.E.; Busakwe, L.; Garcia-Prats, A.J.; Hesseling, A.C.; Jacobs, S.; Mbaba, S.; Meyerson, K.; et al. Opportunities for Mobile App–Based Adherence Support for Children with Tuberculosis in South Africa. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e19154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.T.; Wurmbach, V.S.; Lampert, A.; Bernard, S.; HIOPP-6 Consortium; Haefeli, W.E.; Seidling, H.M.; Thürmann, P.A. Individual factors increasing complexity of drug treatment—A narrative review. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 6, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.S.; Chen, E.Y.H. Is the medication regimen complexity often overlooked, and what can we do about it? J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2025, 55, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacy Programs Administrator. Program Rules: Home Medicines Review. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. 2024. Available online: https://www.ppaonline.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/HMR-Program-Rules.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Pattani, D.; Shirin, S.; Safa Basheer, S.; Kasim, V.A. Adherence and Impact of Medication Regimen Complexity among Geriatric Patients: A Review. Indian J. Pharm. Pract. 2025, 18, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddell, C.B.; Waters, A.R.; Angove, R.S.M.; Gallagher, K.D.; Rosenstein, D.L.; Lisa, L.P.; Kent, E.E.; Planey, A.M.; Wheeler, S.B. Facing financial barriers to healthcare: Patient-informed adaptation of a conceptual framework for adults with a history of cancer. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1178517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anawade, P.; Sharma, D.; Gahane, S. A Comprehensive Review on Exploring the Impact of Telemedicine on Healthcare Accessibility. Cureus 2024, 16, e55996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adindu, K.N.; Osinusi, I.; Adenle, A.M.L.; Onakoya, A.O.; Okeke, J.N.; Ugochukwu, C.C. Integrated Care Models in Primary Care: A Mainstay in Curbing the Burgeoning Menace of Mental Health Issues. J. Neurol. Sci. Res. 2024, 4, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global System for Mobile A. Half of the World’s Population Connected to the Mobile Internet by 2020, According to New GSMA Figures. GSMA Publishes Digital Inclusion Report Highlighting Efforts to Connect ‘Offline’ Populations. GSMA 2014. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/newsroom/press-release/half-worlds-population-connected-mobile-internet-2020-according-gsma (accessed on 29 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).