1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) enables the fabrication of complex, customized polymer components, yet their low surface hardness limits use in mechanical applications. Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D printing, offering high precision and rapid production, has gained attention for producing polymer structures that can be further strengthened through surface modification. One effective post-processing method is cold gas spraying (CGS), a solid-state technique that accelerates powder particles to supersonic velocities in a high-pressure gas jet [

1]. Unlike thermal spraying, CGS operates at low temperatures, preventing polymer degradation and allowing particle adhesion or embedding through high-kinetic-energy impacts, which enhances surface hardness and wear resistance.

Foundational studies have established the principles of cold spray. Champagne [

2] provided a systematic overview of parameters such as gas pressure, nozzle geometry, and particle velocity; Alkhimov et al. [

3,

4] demonstrated that optimized nozzle design improves coating quality, while Schmidt et al. [

5] proposed the “deposition window” concept relating particle velocity to substrate hardness. Papyrin [

6] advanced the process to industrial use. These works built the theoretical basis for extending CGS to polymers, which, unlike metals, exhibit low strength and high strain-rate sensitivity. In addition, a recent comprehensive review by Assadi et al. [

7] summarized the current advances in cold-spray processing and highlighted the roles of particle velocity, size, and material response in governing impact-driven deposition mechanisms. Recent work by Li et al. [

8] further analyzed impact-induced plastic deformation and bonding mechanisms in cold spray, emphasizing the coupled influence of particle velocity, size, and substrate response on deposition efficiency. Yildirim et al. [

9] compared Lagrangian and Arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian finite-element schemes for high-velocity impacts, providing simulation strategies applicable to polymer systems. Recent studies have further examined particle–substrate interactions in cold spray, with Chen et al. [

10] showing that impact-induced plastic deformation, interfacial stress evolution, and material response significantly influence deposition behavior across a wide range of process conditions.

Research gradually expanded toward polymeric targets. Xu and Hutchings [

11] showed that polyolefin powders can deposit on polyethylene and aluminum substrates without melting, while Shah et al. [

12] and Esteki and Khalkhali [

13] simulated HDPE and PU impacts, identifying strain-rate-dependent deformation that supports mechanical interlocking. King et al. [

14] experimentally confirmed that metallic powders can embed into thermoplastics, enhancing hardness. Ganesan et al. [

15] later compared copper and tin particle impacts on PVC and epoxy, revealing that thermoplastics allow embedding whereas brittle thermosets fracture, limiting adhesion.

Nevertheless, partially cured DLP thermosets may behave differently. During early curing, the polymer retains residual plasticity, enabling local deformation under impact. Li et al. [

16] and Mullins et al. [

17] demonstrated that thermoset stiffness and toughness vary with crosslink density and curing stage; intermediate states can momentarily show ductile or delayed fracture behavior. Uddin et al. [

18] employed the Drucker–Prager model to capture the pressure-sensitive plasticity of DLP-printed resin, while Qiao et al. [

19] validated its predictive ability for brittle–ductile transitions under complex stress conditions.

Together, these studies suggest that when a DLP-printed thermoset is in the early curing stage, it may sustain limited plastic flow, allowing cold-sprayed particles to partially embed rather than rebound. In this study, the initial exposure time in the DLP printing process was intentionally kept short, resulting in a partially cured thermoset with an incompletely crosslinked polymer network. At this intermediate stage, the material remains relatively soft, which facilitates particle embedding during cold gas spraying. After spraying, the printed parts were fully cured through an additional post-curing step to achieve the final hardened state. Such mechanical interlocking offers a pathway to reinforce the surface of 3D-printed polymer components without thermal damage. To explore this mechanism, a coupled simulation framework using ANSYS (2025R1 STUDENT) Fluent (for gas flow and particle acceleration) and ANSYS Explicit Dynamics (for impact and penetration) can predict how gas pressure, particle size, and curing state influence penetration depth. This approach provides both mechanistic insight and a cost-efficient route for optimizing surface hardening of 3D-printed polymer parts.

2. Methodology

In order to investigate the feasibility of particle penetration into DLP-printed thermosetting polymer substrates using cold gas spraying (CGS), a two-step simulation approach was developed. This approach mimics the real physical process, in which particles are first accelerated by a high-speed gas jet and then impact the printed substrate with sufficient kinetic energy to cause potential embedding or penetration.

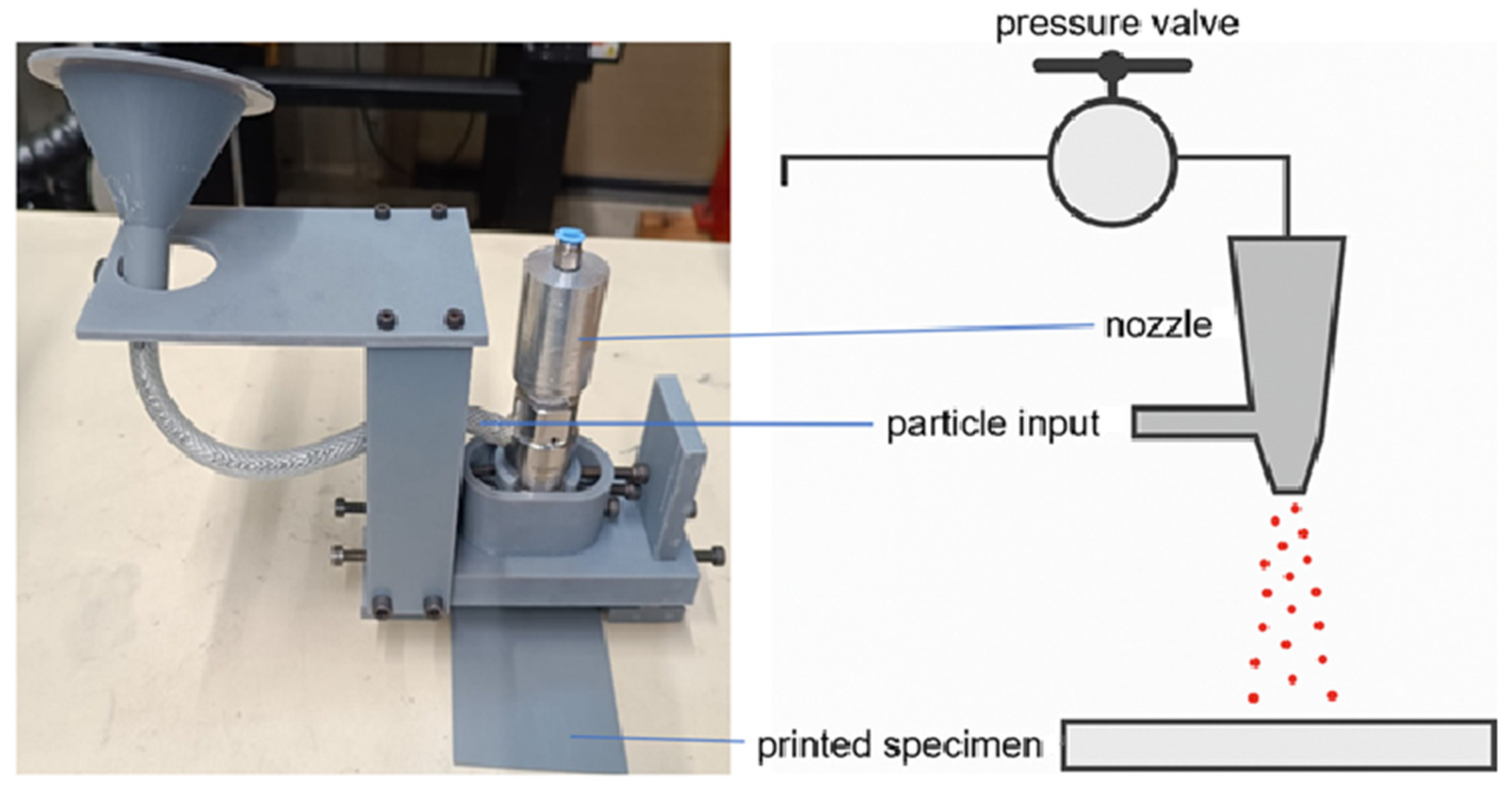

A simplified experimental setup was constructed to replicate the spraying conditions in a controlled laboratory environment. As shown in

Figure 1, the system consists of a pressure-controlled air supply connected to a custom-designed nozzle, with a particle feeder attached near the inlet. The nozzle is positioned vertically above the printed specimen, allowing particles to be accelerated downward under the influence of high-speed gas. The printed substrate is placed on a flat holder and fixed in position during the spraying process.

The test bench is designed to be flexible in terms of pressure control and nozzle-substrate distance, which are essential parameters affecting particle impact behavior. While the current design does not aim to replicate industrial cold spray systems with converging-diverging De Laval nozzles, it effectively provides sufficient particle acceleration for laboratory-scale validation and modeling.

Given the difficulty of directly observing particle embedding into the printed material—due to the time-consuming nature of sectioning, polishing, and microscopic inspection—a numerical simulation method was adopted to replace most physical validation efforts. The full simulation process consists of two stages: 1. determination of particle impact velocity; 2. simulation of particle penetration.

In the first stage, the particle impact velocity is determined through a fluid-particle interaction model using ANSYS Fluent. The particle is treated as a discrete phase, and parameters such as air inlet pressure, nozzle geometry, and particle size are varied to estimate the final velocity of the particle just before impact. The results from this simulation serve as boundary conditions for the second stage.

In the second stage, the particle impact and penetration process is modeled using ANSYS Explicit Dynamics. A finite element model is constructed, including the particle and a representative volume of the DLP-printed resin substrate. The material properties of both components, including density, elastic modulus, and strain-rate-dependent behavior, are defined. The initial velocity of the particle is set according to the Fluent results. This stage enables the analysis of deformation, energy dissipation, and possible penetration depth, offering a cost-effective alternative to destructive testing.

The two-stage simulation approach provides a holistic view of the CGS particle-substrate interaction, while enabling parametric studies of key variables such as gas pressure, particle diameter, and substrate stiffness. This method not only reflects the real process sequence but also ensures that the results are physically consistent across simulation domains.

2.1. Determination of Particle Impact Velocity

Accurately determining the particle velocity prior to impact is a crucial step in cold spray modeling, as it directly affects the particle’s kinetic energy and consequently its deformation and bonding behavior upon collision. Gilmore et al., 1999 [

20] emphasized the importance of process parameters such as gas temperature, pressure, and powder feed rate on in-flight particle velocity, showing that deposition efficiency could reach up to 95% when particles exceed a material-specific critical velocity. Their experimental observations confirmed that particle velocity is the dominant factor influencing deposition outcomes. Building on this, Alonso et al., 2023 [

21] developed an improved one-dimensional analytical model that incorporates nozzle geometry and stagnation conditions to predict particle velocity for various materials. Their model, validated by CFD and experimental data, provides practical maps for selecting optimal spraying parameters without resorting to complex simulations. Inspired by these findings, the present study employs two complementary approaches to estimate particle impact velocity: a full 3D Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation using ANSYS Fluent, and a simplified one-dimensional (1D) analytical model. Together, these methods provide both physical accuracy and practical flexibility in modeling particle acceleration within the nozzle.

2.1.1. CFD Simulation Method

The gas flow and particle acceleration in the cold gas spraying process were simulated using ANSYS Fluent, owing to its capability in modeling compressible flow and discrete particle tracking under high-speed conditions. The internal cavity of the spraying setup was reverse-modeled as a fluid domain consisting of three main parts: an air inlet, a particle inlet, and a vertical outlet, replicating the geometry of the experimental system.

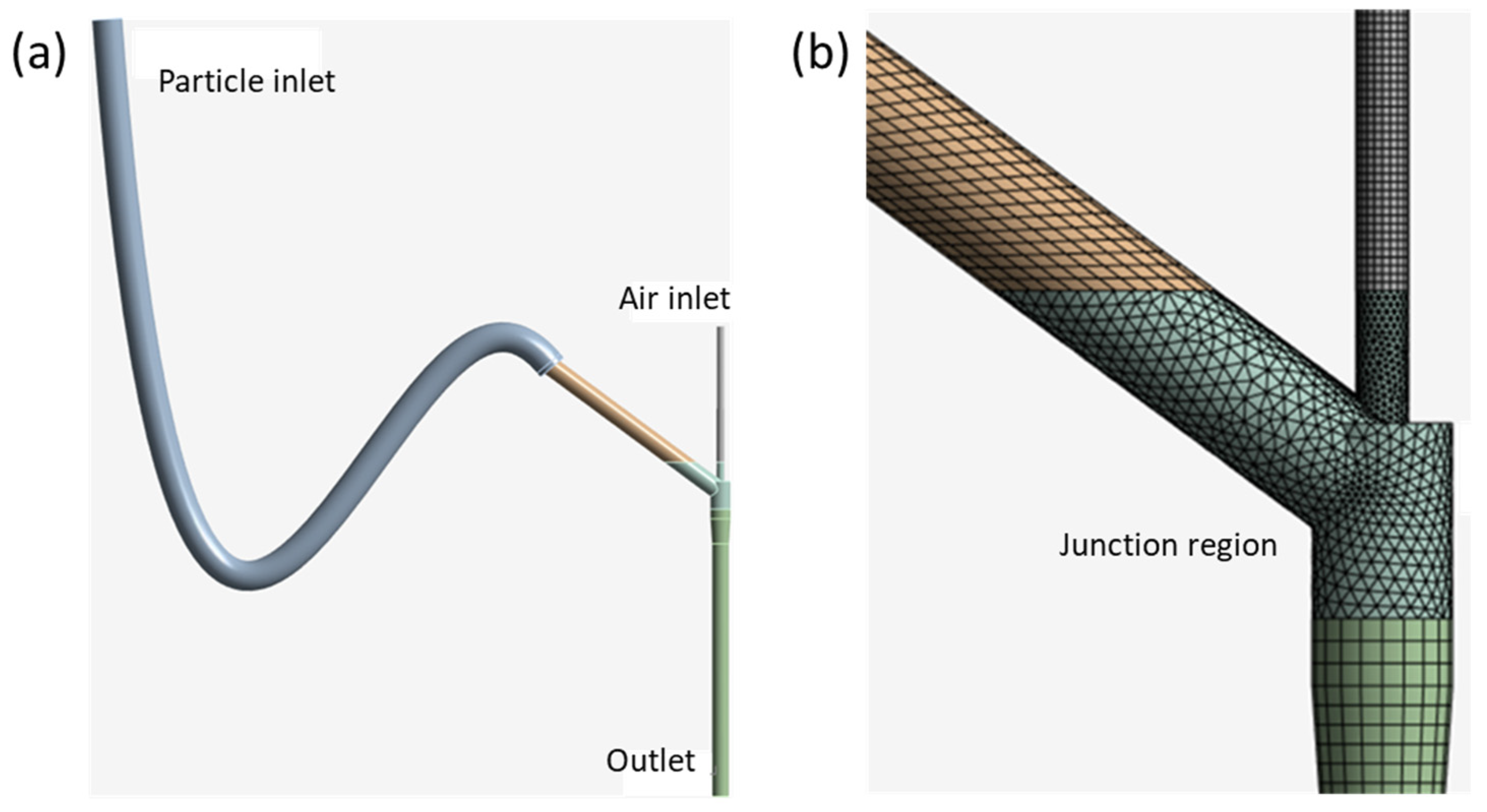

The domain was discretized using a hybrid meshing approach, as shown in

Figure 2a. Regular regions, such as inlet and outlet tubes, employed a structured hexahedral-dominant mesh, while the mixing region with complex curvature was meshed using unstructured tetrahedral elements to ensure sufficient quality, as shown in

Figure 2b. The final grid contained approximately 54,000 elements, and its quality was evaluated using the mesh quality check tool in ANSYS, as shown in

Table 1. The results show that all indicators are displayed in green, meaning they fall within the acceptable range for high-quality meshes. Specifically, the maximum aspect ratio was 7.767, indicating moderate element stretching; the minimum element quality reached 0.273, well above the warning limit of 0.05; the minimum orthogonal quality was 0.221, confirming good face alignment; and the maximum skewness of 0.779 was below the critical value of 0.9. Overall, these green-coded results verify that the mesh maintained good quality and numerical stability throughout the CFD simulation.

A density-based solver was used to capture compressible, potentially supersonic flow (2–5 bar inlet pressure). Simulations were performed under steady-state conditions to reduce computation time, assuming quasi-steady behavior during continuous spraying. Gravity was neglected due to the short particle flight path and dominant aerodynamic forces.

Three physical models were activated:

Energy equation—to account for compressibility and temperature effects in air flow.

k–ω SST turbulence model—providing accurate boundary-layer resolution in internal high-speed flows.

Discrete Phase Model (DPM)—for particle tracking. Silicon carbide (SiC) particles with a diameter of 25 µm and 60 µm were injected from the particle inlet using a surface injection method.

For the DPM, the High Mach Number drag law was applied to include compressibility and shock effects. Boundary conditions were defined as follows: pressure inlets for both air and particles (2–5 bar for air, 0 bar for particles) and a pressure outlet at 0 bar representing atmospheric discharge.

Simulations were iterated until residuals and particle trajectories stabilized. The computed particle exit velocities and gas velocity fields near the outlet were extracted for use in the subsequent structural impact simulations.

2.1.2. One-Dimensional Calculation Method

To complement the CFD simulations, a one-dimensional (1D) analytical model was developed to efficiently estimate particle acceleration in the nozzle. Previous studies have validated the accuracy of 1D gas-dynamic formulations for predicting particle velocities in cold spray processes. Champagne et al. [

22,

23] demonstrated that 1D models provide reliable engineering approximations, typically within 7% of experimental values. Grujicic et al. [

24] further improved the approach by incorporating acceleration, deceleration, and gas expansion effects, while Morsi and Alexander [

25] established a widely adopted drag correlation for particle motion. These studies confirm the suitability of simplified 1D methods for rapid evaluation and parametric analysis where computational efficiency is critical.

The particle motion was described by Newton’s second law considering aerodynamic drag:

where

is the drag coefficient,

the particle projected area,

the gas density, and

and

the gas and particle velocities. Substituting

gives:

The drag coefficient was dynamically updated using the empirical model of Carlson and Hoglund [

26], which accounts for both Reynolds and Mach number effects:

This formulation enables accurate representation of high-speed compressible flow regimes.

The equation was solved in MATLAB (R2024a) using an explicit Euler integration scheme with a constant time step Δt. Instantaneous gas velocity and density, obtained from the CFD results, were used as input for each step. The iteration continued until the total particle travel distance of 63 mm (measured from the test bench) was reached, and the final velocity was recorded as the predicted particle impact velocity.

This simplified 1D approach allows rapid evaluation of particle acceleration under various gas pressures and provides a practical means for sensitivity studies and cross-validation of CFD results.

2.2. Simulation of Particle Penetration

The penetration behavior of silicon carbide (SiC) particles into a DLP-printed thermoset resin substrate was simulated using ANSYS Explicit Dynamics. The substrate material, Loctite IND147 HDT230, was selected for its high stiffness, dimensional stability, and heat deflection temperature of 230 °C, making it representative of high-performance DLP resins. Since IND147 is not included in the ANSYS material library, its mechanical properties were extracted from the manufacturer’s datasheet and manually defined in the Engineering Data module. The simulation used the “green” (uncured) condition to approximate the early stage of the printed resin, which exhibits moderate stiffness and limited ductility.

To capture the pressure-dependent yielding of the thermoset resin under high-strain-rate impact, the Drucker–Prager (DP) strength model was applied. The DP model extends the von Mises yield criterion by incorporating hydrostatic pressure effects, allowing a more realistic representation of brittle, pressure-sensitive polymers. Among the available variants, the Stassi–Drucker–Prager model was selected, as it accounts for different yield strengths under tension and compression and provides a practical balance between accuracy and data availability. The required material parameters (tensile yield stress and compression yield stress) were derived from tensile and compression test results of printed IND147 samples.

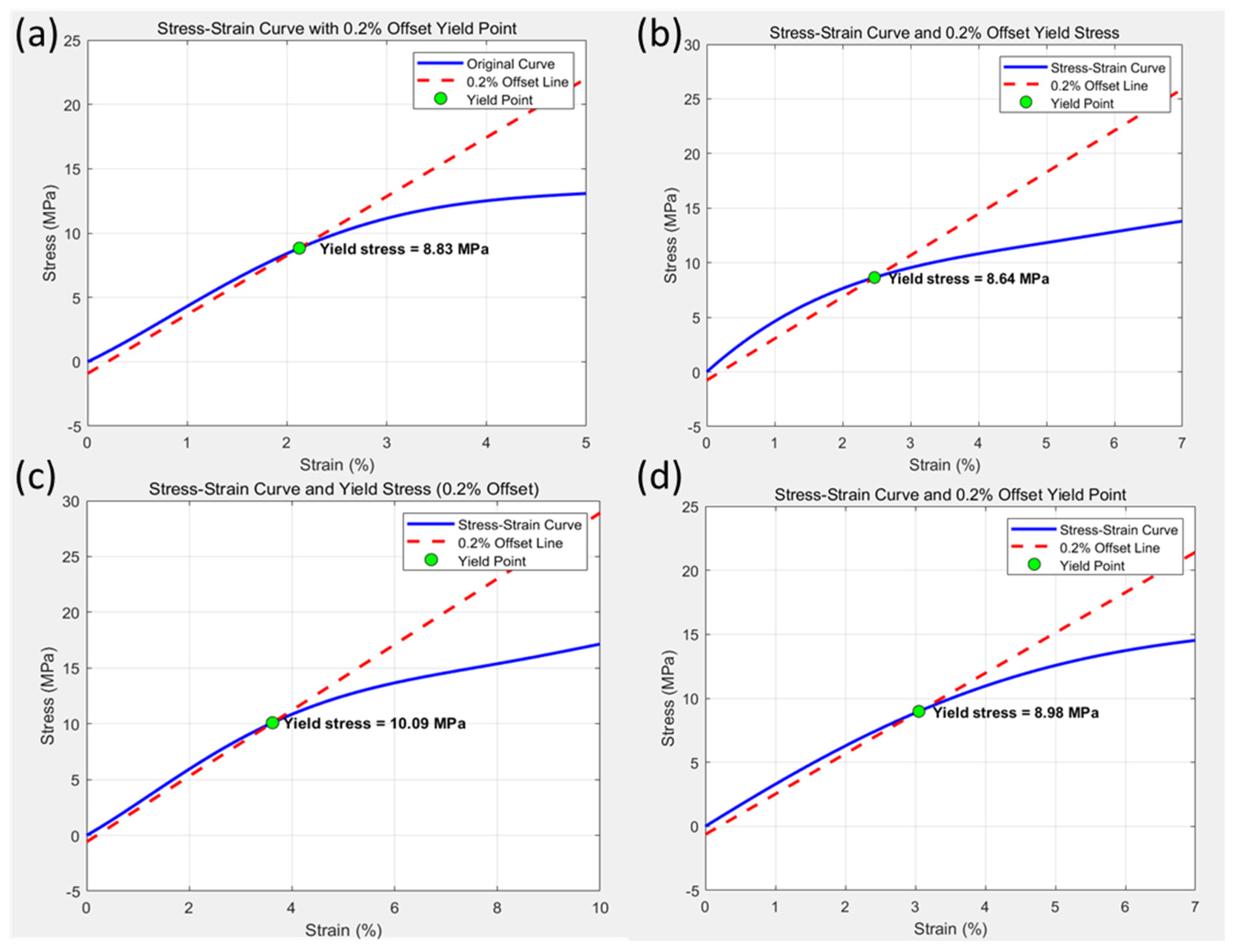

Four sets of tensile specimens were tested, and the engineering stress–strain curves are shown in

Figure 3. The tensile yield strength was determined using the 0.2% offset method, which is commonly applied to polymeric materials lacking a distinct elastic–plastic transition. For each curve, an offset line parallel to the initial elastic slope was constructed, and the intersection point with the measured stress–strain curve was taken as the yield point. The individual yield strengths obtained from the four measurements were averaged to provide the final tensile yield strength used in the material modeling. The average calculated 0.2% offset tensile yield strength is reported in

Table 2.

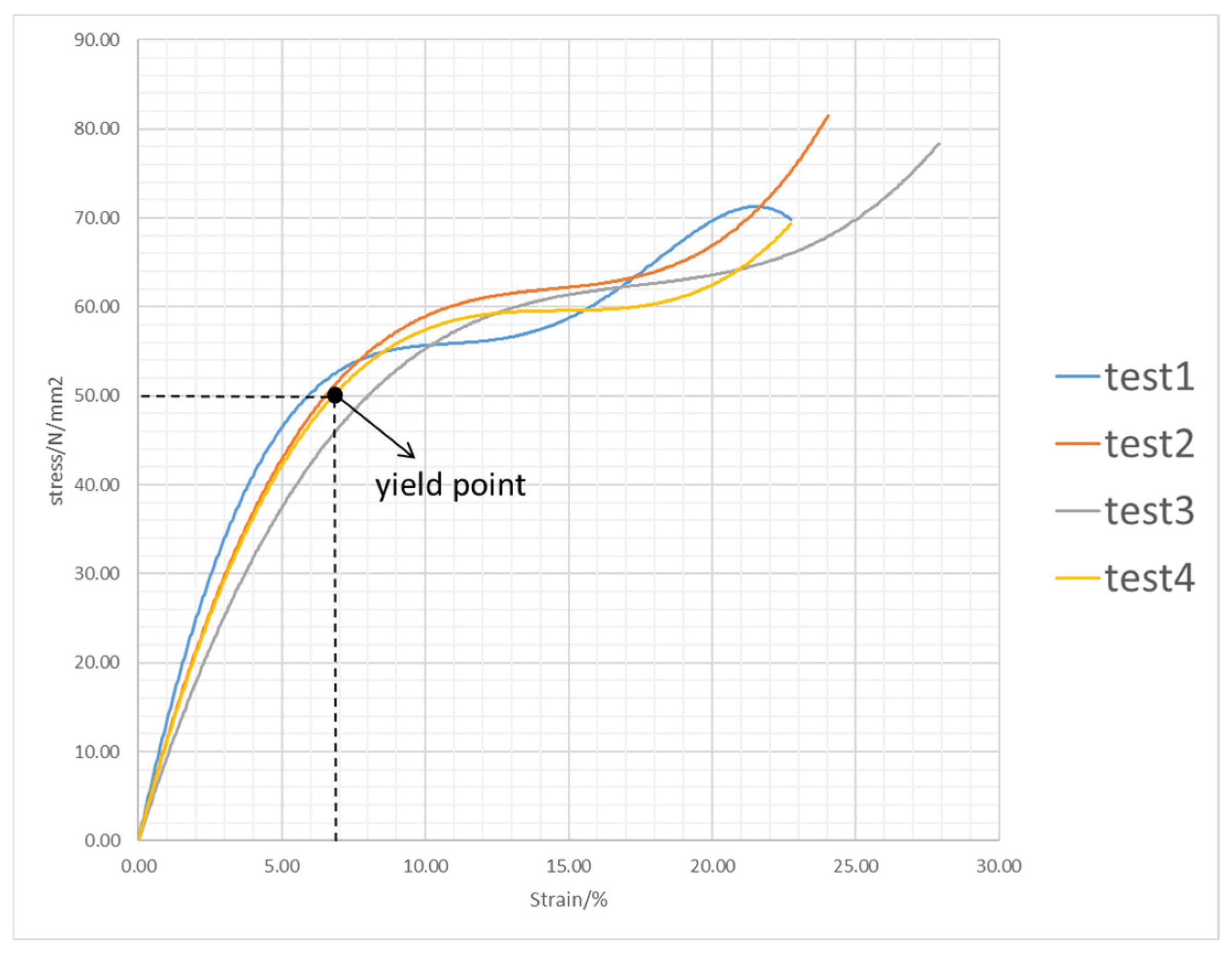

Four compression tests were also conducted to characterize the compressive behavior of the resin. Unlike the tensile curves, the compression stress–strain response of IND147 exhibits a clear and well-defined yield transition, where the curve deviates noticeably from the previously linear region. Owing to the presence of this distinct yield point, the 0.2% offset method was not required. Instead, the compressive yield strength was determined directly from the visible transition point in each stress–strain curve, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The average value of the four measurements is included in

Figure 5, together with the tensile yield strength for comparison.

The geometric model consisted of a single spherical SiC particle (diameter = 25 µm/60 µm) impacting a cylindrical IND147 substrate. A spherical particle was selected for two reasons. First, the particle velocity obtained in the preceding CFD step was calculated using drag coefficient and particle projected area that are defined for spherical particles. Maintaining the same shape in the impact simulation ensures consistency between the gas–particle acceleration model and the subsequent explicit dynamics analysis. Second, most numerical studies on cold-spray particle penetration employ the same modeling strategy—using a single spherical particle and a cylindrical substrate with a quarter-symmetry reduction—which has repeatedly demonstrated reliable predictive capability in the literature.

The particle diameter of 25 µm and 60 µm was chosen because microscopic observations showed that the SiC abrasive used in this work, although irregular in shape, had an average equivalent diameter in the range of approximately 25 µm and 60 µm.

While angular particles may penetrate more easily due to their sharper features, incorporating such geometries into the simulation would require extensive statistical characterization of particle shapes and the development of a representative irregular geometry. Irregular particles also lack geometric symmetry, making it impossible to apply quarter-symmetry and resulting in significantly higher computational cost. Considering that this study aims to establish a preliminary and computationally efficient penetration model, spherical particles were adopted as a practical and widely accepted simplifications.

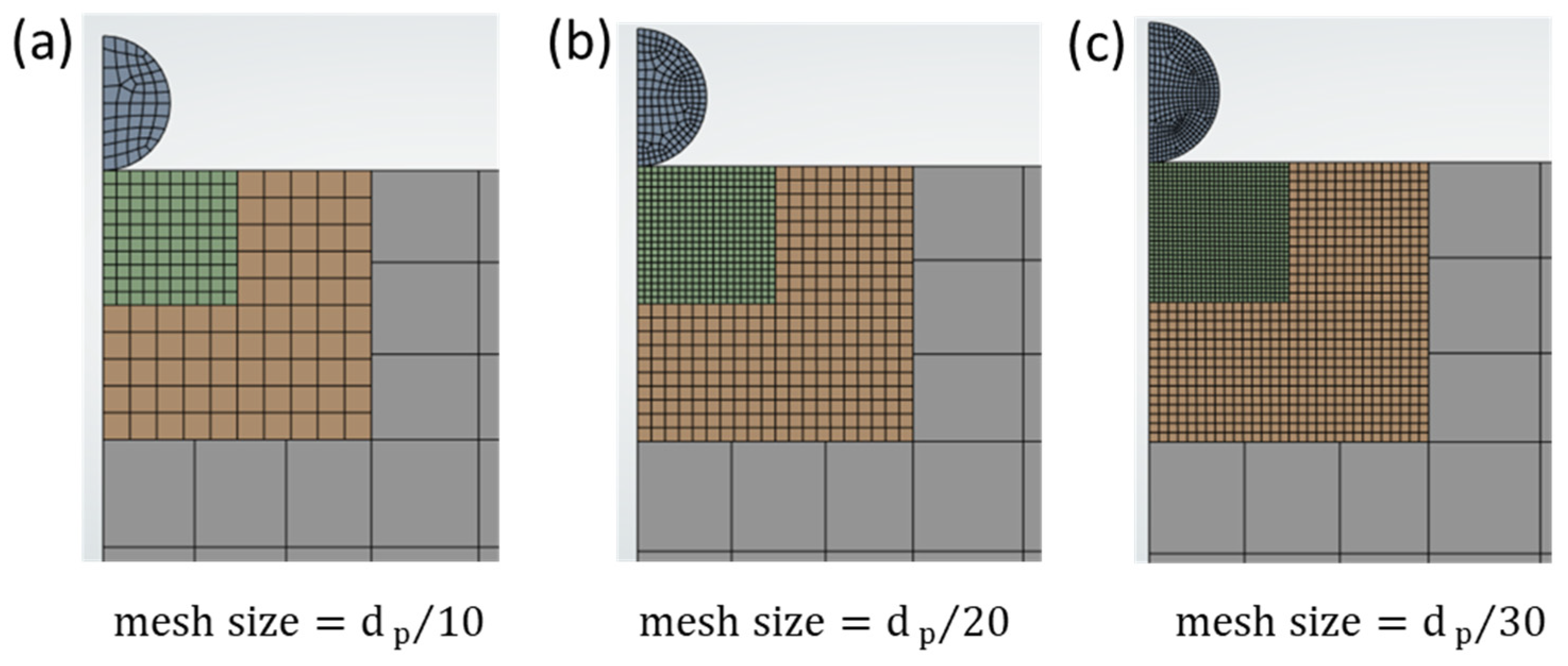

Meshing was performed using the MultiZone method, combining structured hexahedral elements in critical zones with unstructured tetrahedral elements elsewhere. As shown in

Figure 5a–c, three mesh refinements were compared—core element sizes of

,

,

—to evaluate the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. To ensure the reliability of the generated mesh, a comprehensive mesh quality assessment was performed in ANSYS. As shown in

Table 3, key quality metrics such as minimum element quality, aspect ratio, Jacobian ratio, and skewness were evaluated. The minimum element quality of 0.188 and a minimum Jacobian ratio of 0.283 exceeded the recommended thresholds, indicating a well-shaped and stable mesh. Other parameters, including maximum aspect ratio (11.13), skewness (0.885), and warping angle (6.25°), were all within acceptable limits, confirming that the mesh was suitable for high-strain-rate simulations without numerical distortion.

The particle initial velocity, obtained from the CFD analysis described earlier, was applied as the input condition in the explicit dynamics model. The particle was assigned a vertical downward velocity corresponding to inlet pressures ranging from 2 to 5 bar, while the substrate’s bottom surface was fixed. Gravity was neglected due to the microsecond-scale interaction time, consistent with previous cold-spray simulations. The simulation proceeded until the particle reached maximum penetration depth, which was recorded for later comparison with experimental observations.

3. Results

To investigate the influence of key parameters on particle penetration behavior, a series of controlled simulations were conducted using the previously defined geometry and material models. Three main variables were considered: mesh resolution, particle velocity, and air pressure. The mesh size in the refined impact zone was varied across three levels (, , and ), where denotes the particle diameter.

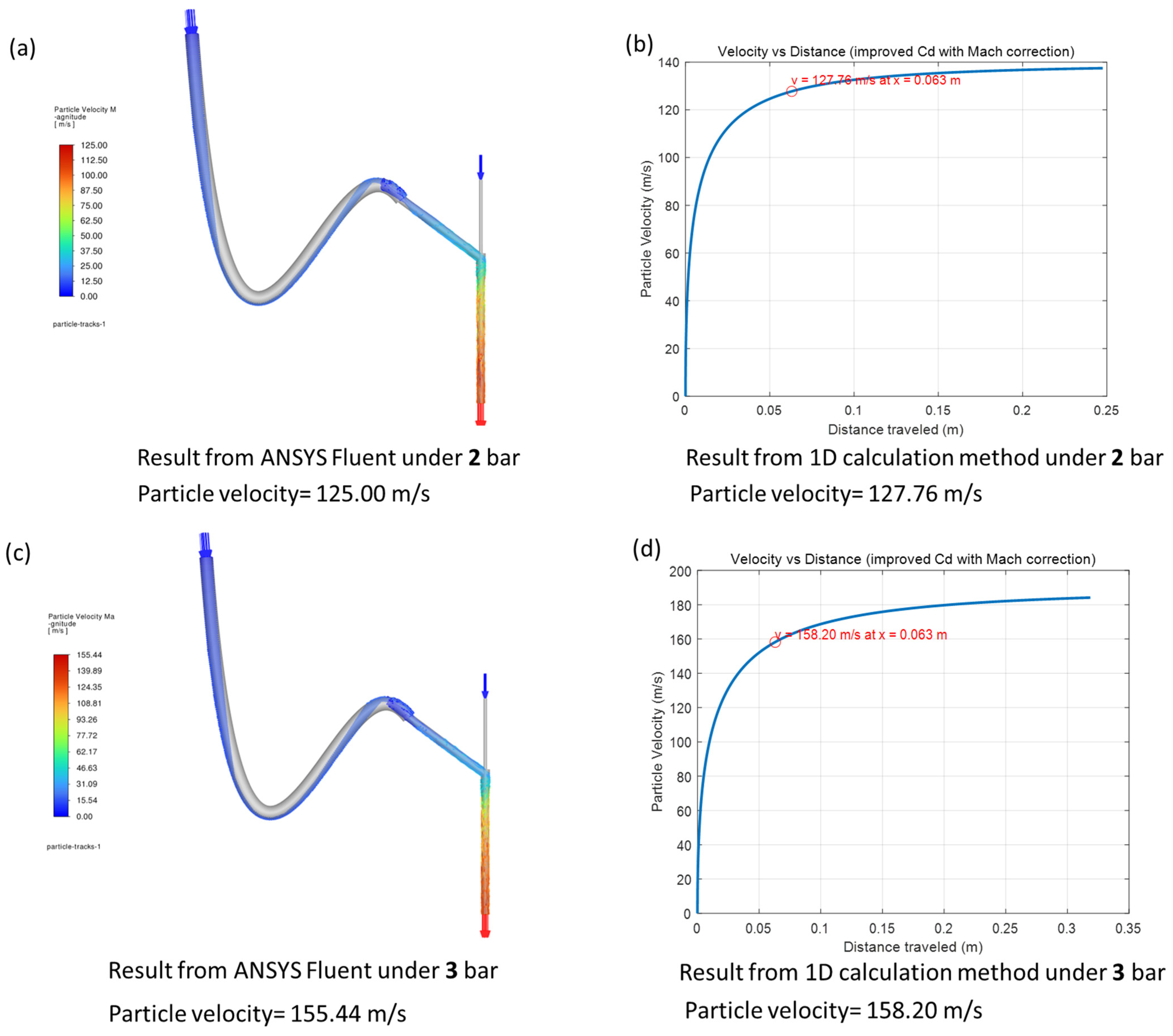

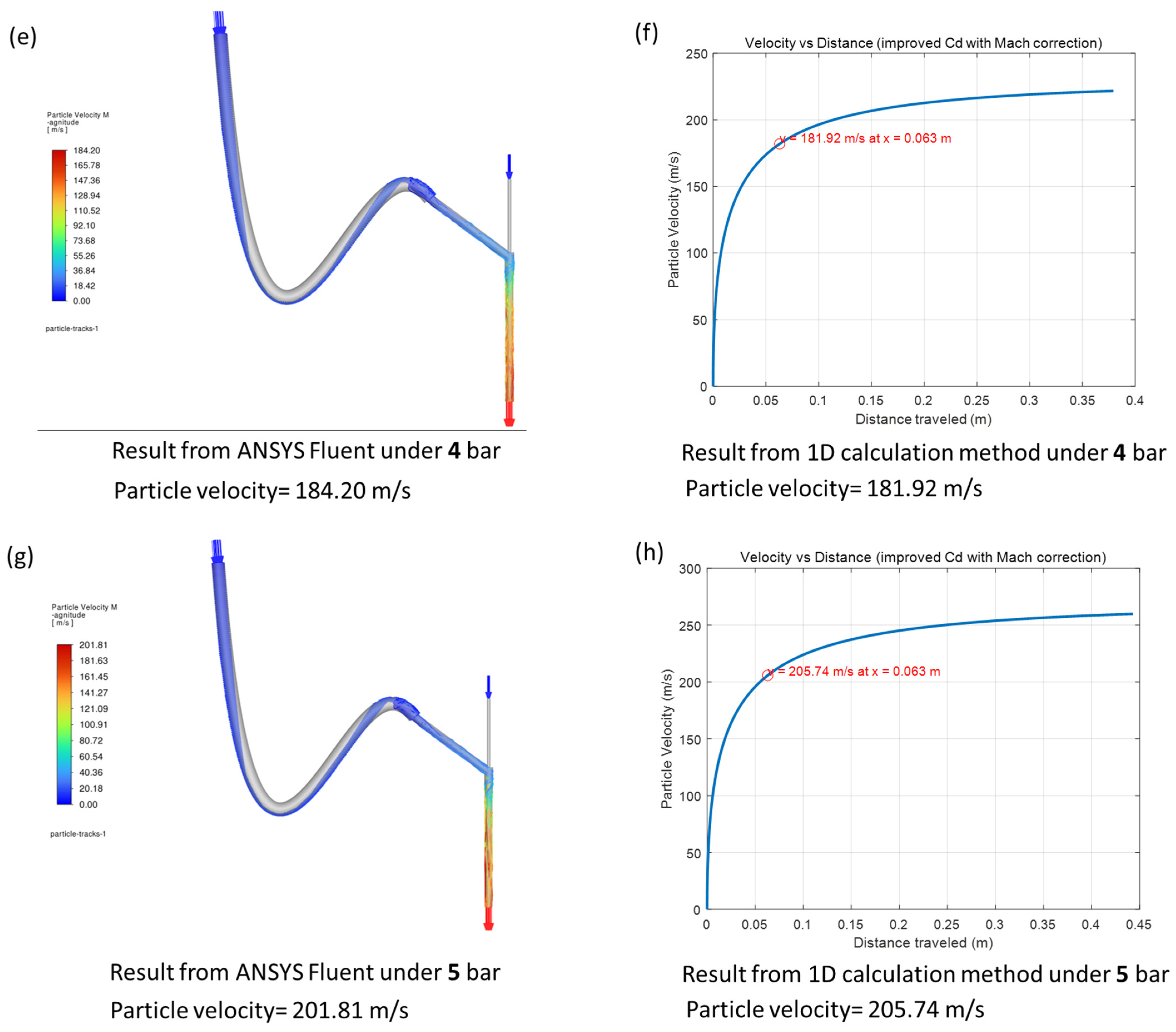

The particle outlet velocities obtained from the CFD simulations and the 1D analytical model were compared under different inlet pressures and two different particle diameters (25 µm and 60 µm). As shown in

Figure 6 and

Table 4, the analysis begins with the 25 µm particles. For 2 bar, the Fluent simulation in

Figure 6a predicted a particle velocity of 125.00 m/s, while the 1D model in

Figure 6b yielded 127.76 m/s. At 3 bar, the Fluent result in

Figure 6c was 155.44 m/s, compared with 158.20 m/s from the 1D calculation in

Figure 6d. For 4 bar,

Figure 6e shows a Fluent-predicted velocity of 184.20 m/s, while the corresponding 1D result in

Figure 6f was 181.92 m/s. Finally, at 5 bar, the Fluent velocity in

Figure 6g reached 201.81 m/s, and the 1D model in

Figure 6h predicted 205.74 m/s.

The close agreement between the two methods across all pressure levels demonstrates that the simplified 1D model successfully validates the CFD simulation results. Therefore, the Fluent-derived outlet velocities were adopted as reliable initial input conditions for the particle impact simulations in ANSYS Explicit Dynamics, ensuring realistic momentum representation in subsequent penetration analysis.

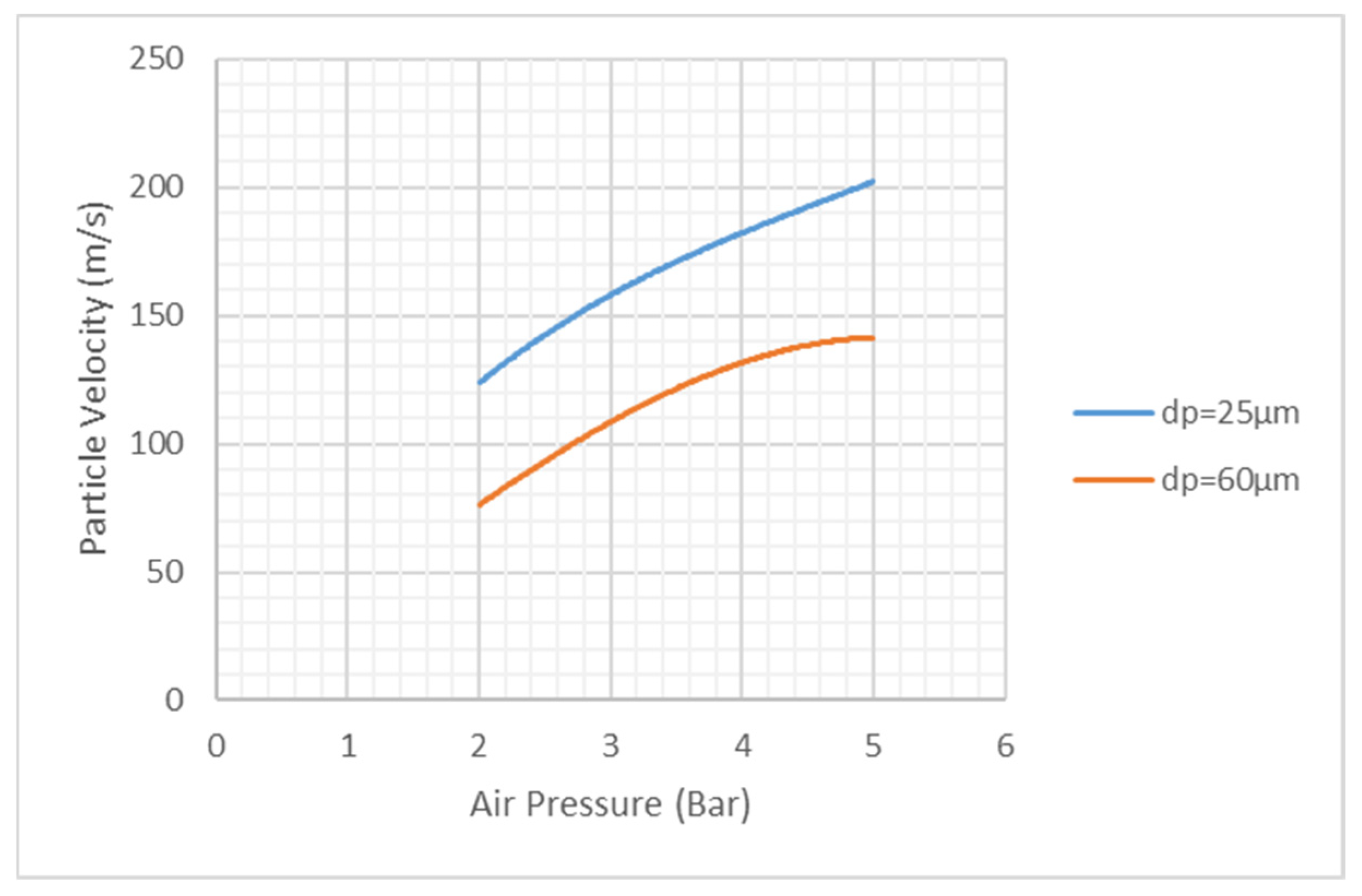

Based on this good agreement, the Fluent-predicted outlet velocities were taken as the input parameters for the subsequent particle penetration simulations, that is, as the particle outlet velocities at the nozzle exit. For the larger 60 µm particles, the outlet velocities were obtained in the same way using the validated CFD model, without an additional comparison to the 1D method.

Table 5 summarizes the Fluent outlet velocities for both particle diameters at all investigated inlet pressures, and

Figure 7 compares the two datasets. As the inlet pressure increases, the particle velocity increases accordingly. At the same pressure, however, the 60 µm particles exhibit lower outlet velocities than the 25 µm particles. This behavior can be explained by their higher mass and inertia: while the aerodynamic drag force grows roughly with the particle cross-sectional area, the particle mass scales with its volume. Consequently, the acceleration of the larger particles is smaller, and they cannot reach the same velocity as the smaller particles within the limited acceleration length of the nozzle.

Given these outlet velocities, the penetration depth was defined as the maximum vertical distance the particle traveled into the substrate, as illustrated in

Figure 8. Two metrics were used for evaluation. First, the penetration depth was normalized by the particle diameter

to allow consistent comparison between the two particle sizes. Second, the absolute penetration depth was also recorded in micrometers to reflect the real embedding distance. Apart from the particle diameter and the inlet pressure, all other parameters, including substrate geometry and boundary conditions, were kept constant across the simulations to isolate the effects of these two variables.

3.1. Influence of Mesh Resolution

To assess the effect of mesh density on the accuracy and stability of the simulation, three mesh configurations were tested in the core impact region using element sizes of

,

, and

, and particle size of

. The material used for all simulations was the IND147 resin defined in

Section 2.2. The refinement focused on the contact zone between the particle and substrate, where high stress gradients and localized plastic deformation occur.

As shown in

Figure 9, the simulation results exhibit clear improvements with increasing mesh refinement. For the coarsest mesh

, the stress and strain contours appear diffused around the particle–substrate interface, and the deformation zone is less distinct. This lower resolution tends to smooth out local stress variations, leading to a slightly underestimated penetration depth.

When the mesh was refined to , both the stress field and the deformation profile became more concentrated and sharply defined. The contact interface was better resolved, enabling a more accurate representation of the localized plastic deformation. The particle penetration depth increased moderately, reflecting the improved sensitivity of the model to local stress concentrations.

Further refining the mesh to resulted in only marginal changes compared with the case. The stress distribution and penetration depth showed near-convergent behavior, suggesting that numerical accuracy was already achieved at . This indicates that the solution becomes mesh-independent beyond this resolution. Therefore, was adopted for all subsequent simulations, providing a balance between computational efficiency and predictive precision.

These findings confirm that excessive mesh refinement offers minimal improvement while significantly increasing computation time and memory requirements. The configuration proved sufficient to capture the essential mechanics of particle embedding with reliable accuracy and acceptable numerical stability.

3.2. Influence of Air Pressure on Penetration Depth

The influence of air pressure on particle embedding in the IND147 resin was investigated using inlet pressures from 2 to 5 bar. Outlet particle velocities were obtained from validated CFD simulations and used as input for the explicit–dynamics penetration model. Two particle sizes, 25 μm and 60 μm, were selected to evaluate the combined effect of air pressure and particle diameter. In terms of factor structure, air pressure acted as a continuous factor with four levels, enabling the identification of clear nonlinear trends, while particle size functioned as a two-level factor represented by two corner points, which allows linear and interaction effects to be resolved but does not support fitting a full quadratic curvature in the size direction.

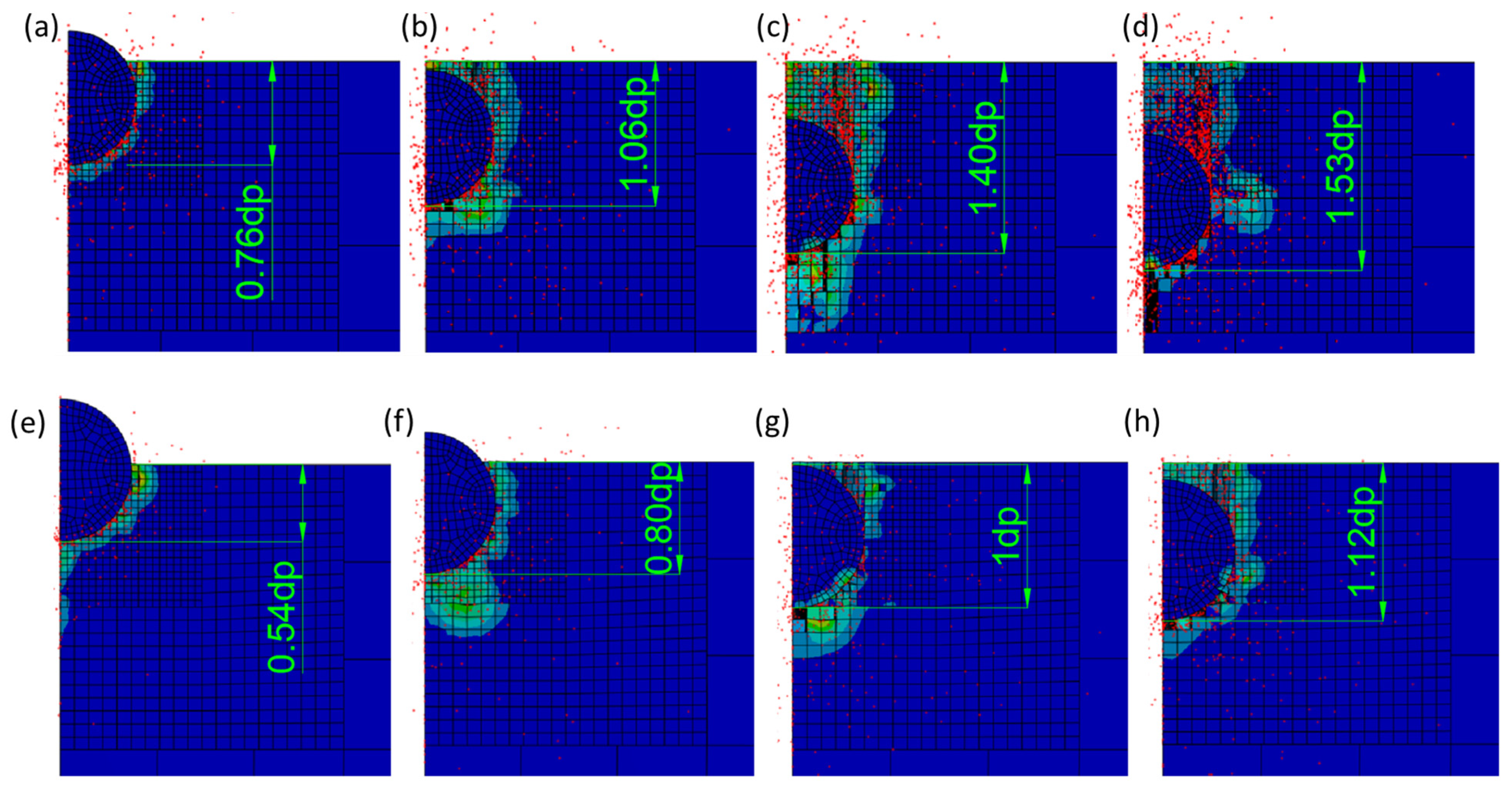

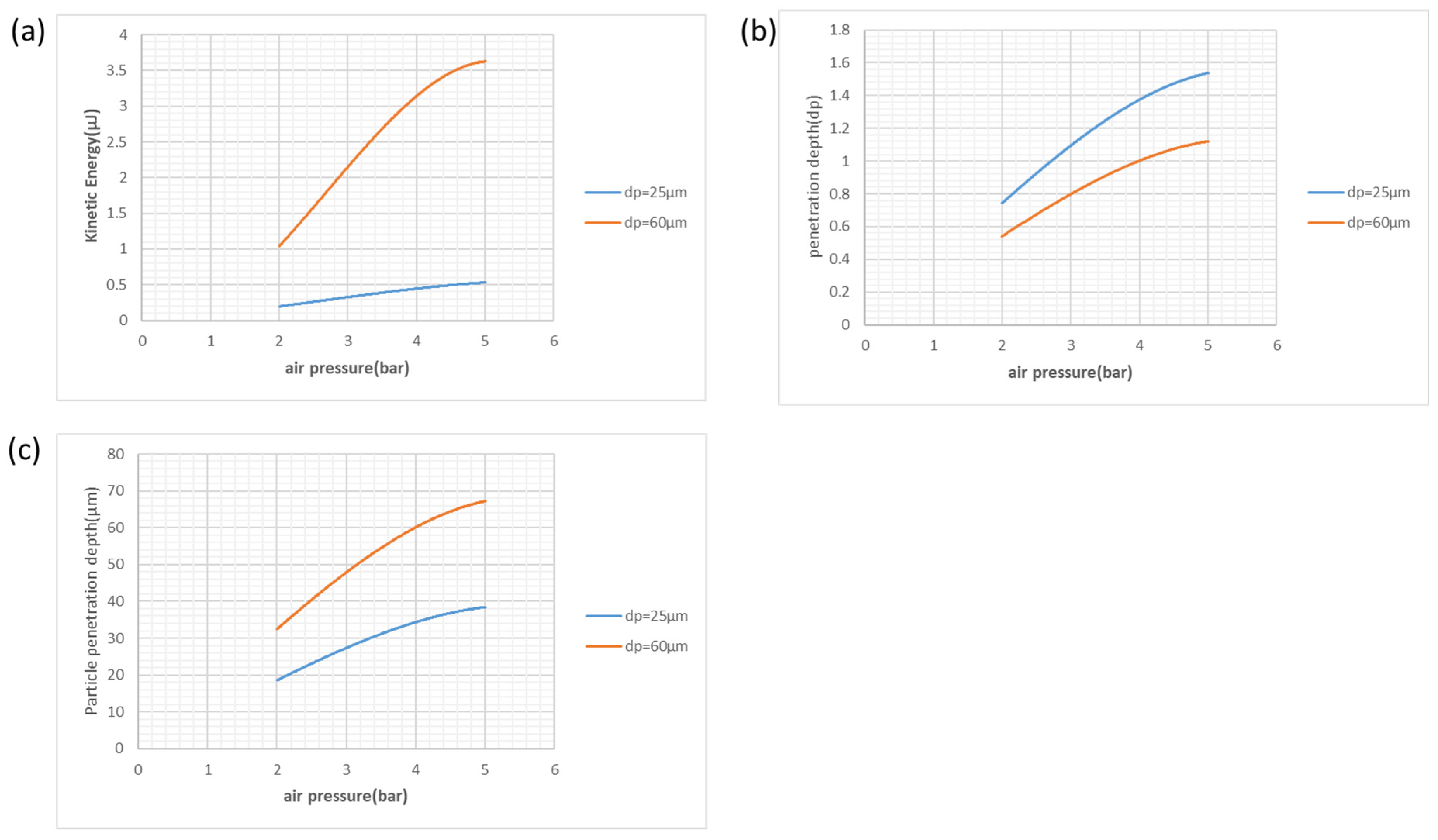

For the 25 μm particles, penetration depth increased monotonically with pressure, as shown in

Figure 10a–d. At 2 bar, partial embedding occurred with a normalized depth of 0.76 d

p (19 μm). Increasing the pressure to 3 bar resulted in nearly full embedding at 1.06 d

p (26.5 μm), followed by deeper penetrations of 1.40 d

p (35 μm) and 1.53 d

p (38.25 μm) at 4 and 5 bar, respectively. The growth rate diminished above 4 bar, suggesting an early saturation behavior. This behavior is consistent with the evolution of kinetic energy, which increased from 0.20 μJ to 0.53 μJ over the same pressure interval, as shown in

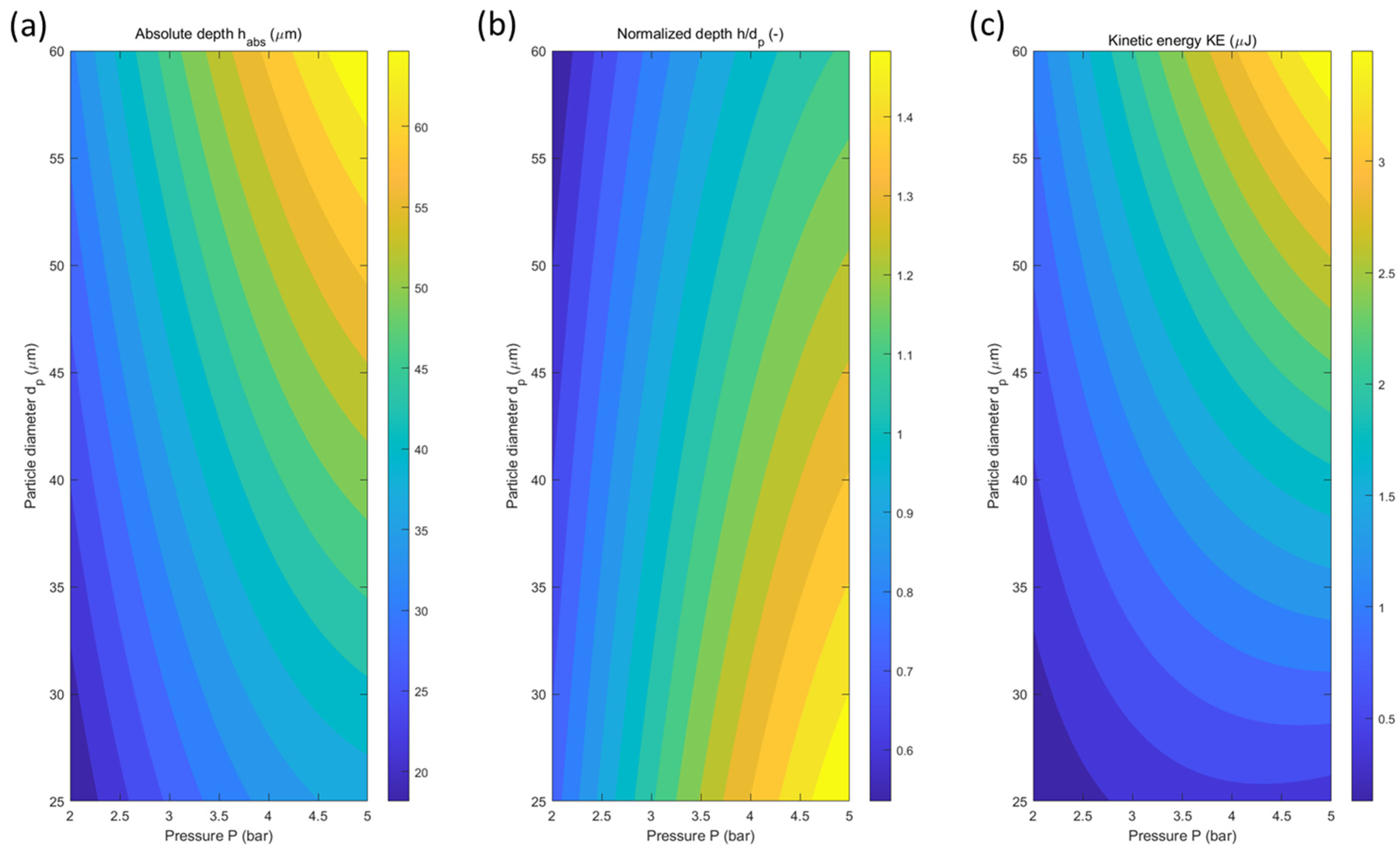

Figure 11a. The response-surface contour for absolute depth (

Figure 12a) exhibits clear curvature along the pressure axis, confirming that pressure introduces a strong quadratic influence, while the particle-size direction remains predominantly linear.

The 60 μm particles exhibited a similar monotonic relationship, although their normalized depths were consistently lower than those of the smaller particles, as shown in

Figure 10e–h. Penetration depths increased from 0.54 d

p (32.4 μm) at 2 bar to 1.12 d

p (67.2 μm) at 5 bar. Because particle mass scales approximately with d

p3, the larger particles possessed significantly higher kinetic energies—from 1.06 μJ to 3.62 μJ—which enabled much deeper absolute penetration (

Figure 11c) under identical pressure conditions, as presented in

Figure 12a. Nevertheless, their normalized penetration remained smaller because the increase in particle size exceeds the increase in embedded distance, as shown in

Figure 11b. This contrasting trend between absolute depth and normalized depth is clearly reflected in the response surfaces for h_abs, h/d

p, and KE (

Figure 12a–c), which show strong pressure dependence combined with a consistent linear shift induced by particle size.

A comparison of both particle sizes reveals a distinct interaction between pressure and size. At low pressures, the penetration difference between 25 μm and 60 μm particles is moderate, but the disparity becomes more pronounced as pressure increases. The smaller particles gradually approach saturation above 4 bar, whereas the larger particles continue to accumulate kinetic energy and penetrate more deeply. This difference reflects the size–dependent energy conversion efficiency: smaller particles accelerate more easily but carry limited kinetic energy, while larger particles maintain high momentum despite experiencing stronger aerodynamic drag.

This interpretation is consistent with independent findings reported by Wu et al. [

27], who examined PEEQ and deposition behavior in cold-sprayed NiCoCrAlY particles across a range of diameters. Their results showed that larger particles exhibit higher local plastic strain and require a lower critical velocity for deposition, whereas very small particles experience two disadvantages: an increased critical velocity and stronger deceleration due to bow-shock effects. Their analysis further identified a “best particle size window”—a range in which particle velocity exceeds critical velocity by the greatest margin. For particles smaller than this range, velocity drops faster than the reduction in critical velocity; for significantly larger particles, gains in velocity diminish. These mechanisms closely align with the explicit-dynamics trends observed in the present work: although the deformation profiles of different particle sizes appear superficially similar, the larger particles carry more kinetic energy, produce higher PEEQ values, and achieve deeper and more stable embedding.

Overall, the combined results demonstrate that particle embedding is governed simultaneously by inlet pressure and particle size. Air pressure acts as a strong nonlinear driver that controls particle velocity and kinetic energy, while particle diameter modulates inertia, deformation, and the efficiency of energy transfer into the substrate. The two-factor structure of the study therefore reveals that while pressure determines the curvature of the penetration response, particle size introduces a linear shift and a physically meaningful interaction effect. These insights explain the experimentally observed transition from partial to full embedding and clarify why larger particles, despite lower normalized depth, exhibit superior absolute penetration and a greater likelihood of effective deposition.

3.3. Experimental Validation

To verify the reliability of the numerical model and its relevance to real particle embedding behavior, a physical validation experiment was conducted using DLP-printed IND147 thermosetting resin substrates. The aim was to confirm that the simulation accurately captured the essential mechanics of SiC particle penetration under impact

Prior to preparing the cross-sectional specimens, the sprayed resin surfaces were first examined under an digital microscope (VHX-7000, Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan) to obtain an initial qualitative impression of the embedded SiC particles. Representative images for inlet pressures of 3 bar and 5 bar are shown in

Figure 13. As can be seen, the specimen treated at 5 bar exhibits a higher density of visible particles compared to the 3 bar case. However, surface observations alone only reveal exposed fragments; they do not allow the actual penetration depth or the full embedding state of the particles to be determined. Therefore, a more reliable quantitative assessment required preparing cross-sectional samples through mounting and polishing, as described in the following validation procedure.

Based on the simulation results, an inlet pressure of 3 bar was selected for validation, as the predicted penetration depth of 25 μm SiC particles under this condition was approximately one particle diameter (1 dₚ)—a depth suitable for direct optical observation. A real IND147 sample was printed and sprayed with SiC particlesunder identical pressure using the same setup as in the simulation.

After spraying, the specimen was embedded in transparent epoxy resin following a standard mounting process (

Figure 14) to preserve the impact zone. Once cured, the mounted sample was ground and polished carefully to expose the cross section of the embedded particle. The preparation ensured a clear view for microscopic comparison while avoiding particle loss or deformation during polishing.

The polished section was examined under a digital microscope VHX 7000 (Keyence) (

Figure 15). The SiC particle was distinctly visible, with diameter of 25 μm and with its top surface nearly flush with the substrate surface, confirming a penetration depth close to 1 dₚ. The result showed excellent agreement with the simulated outcome, validating the numerical prediction both qualitatively and quantitatively.

To further assess model robustness, an additional simulation was carried out using an angular SiC particle, reflecting the real particle morphology observed under microscopy. The angular particle exhibited a slightly shallower embedding depth (

Figure 16b) compared to the spherical model (

Figure 16a). This difference is attributed to reduced contact uniformity, uneven stress transfer, and higher aerodynamic drag of angular shapes, which collectively limit penetration energy efficiency. Despite these effects, the general deformation pattern remained consistent with the spherical case, confirming that the spherical assumption provides a reliable approximation for average embedding behavior.

The experimental validation showed strong consistency between the simulated and measured penetration behavior. The agreement in penetration depth, deformation pattern, and final particle position confirmed that the model accurately captures the key mechanisms of high-velocity particle embedding in thermosetting DLP resins. Minor differences were mainly caused by unavoidable factors such as particle shape irregularity and local surface variations, but these did not affect the overall trend. The 3 bar validation further demonstrated that the simulation reliably predicts penetration for both particle sizes, even though real particles carry slightly different kinetic energies compared with the idealized spherical ones assumed in the model. Overall, the validated workflow provides a practical and robust basis for extending the approach to different materials, particle sizes, and impact conditions in future cold-spray and additive-manufacturing research.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

This study investigated the penetration behavior of SiC particles into DLP-printed IND147 thermosetting resin under conditions representative of cold-spray impact. By integrating CFD-derived outlet velocities with explicit-dynamics simulations, a realistic description of high-speed particle–substrate interaction was achieved. The developed workflow successfully predicted particle deformation, stress evolution, and final embedding depth, providing insight into the mechanisms governing surface modification in polymer-based materials.

The simulation results demonstrated that mesh refinement strongly influences penetration accuracy, with a mesh size of dp/20 offering an effective balance between precision and computational cost. Penetration depth increased with inlet pressure—from 0.76 dp at 2 bar to 1.53 dp at 5 bar—indicating that higher kinetic energy promotes deeper embedding. Particle size also played an important role: although 60 μm particles exhibited lower normalized penetration due to their larger diameter, their absolute penetration depth was significantly greater because of their higher kinetic energy. These trends were further clarified using response-surface analysis, which showed a strong nonlinear dependence on pressure and a predominantly linear contribution from particle size, reflecting the two-level nature of the size factor in this study.

Experimental validation at 3 bar confirmed the predictive capability of the simulation framework. Despite the irregular shape of real particles and inevitable variations in local surface conditions, the measured penetration depth agreed well with the numerical results, verifying that the model captures the essential deformation and embedding mechanisms of thermoset polymers subjected to high-velocity impact.

Beyond confirming model accuracy, the results highlight the potential of cold-sprayed particle embedding as a surface-hardening strategy for DLP-printed resins. The localized densification and plastic deformation induced by hard SiC particles suggest a pathway for enhancing hardness, wear resistance, and durability without altering the bulk properties of the polymer.

Looking ahead, several meaningful extensions of this work can further deepen the analysis and improve the robustness of the modeling approach. Because particle diameter in the present study was evaluated only at two levels (25 μm and 60 μm), the response in that direction represents a linear trend bracketed by two corner points. Future experiments should include one or more center-point diameters—such as 35–40 μm—to enable full quadratic regression and allow a complete factorial interpretation of particle-size effects. Incorporating additional input variables, such as impact angle, curing degree, or spray distance, within a controlled parametric or factorial-design framework would also help reveal interactions between pressure and particle morphology. Furthermore, extending the numerical model to include angular or irregular particle shapes would provide insight into shape-dependent penetration behavior and enhance the predictive capability of the proposed workflow.