Abstract

In the era of data, data generation continues to grow day by day, posing new challenges for processing systems due to the dynamism of its volume, variety, and velocity. To process data in real time, stream processing systems (SPS) serve as the keystone of real-time data analytics systems. However, SPS must operate under strict quality of service (QoS) constraints, which require dynamic adaptation of their internal logic to sustain performance. In this work, we address the problem of automatic text data generation using large language models (LLMs) by employing an evolutionary approach to guide prompt learning. The process enables us to automatically discover prompts by applying a black-box approach to generate synthetic data from a reference dataset. This approach aims to enrich training datasets and enhance the generalization capabilities of AI-driven adaptive SPS models.

1. Introduction

In the era of data, data generation continues to grow day by day, posing new challenges for processing systems due to the dynamism of its volume, variety, and velocity. These are the well-known properties of big data scenarios [1]. In such highly dynamic environments, it is critical to enable systems to make autonomous decisions to meet strict quality-of-service (QoS) requirements. Systems must be elastic to allocate and deallocate resources at runtime to process data with minimal latency while maximizing resource utilization. Stream processing systems process data closer to real time. In recent years, many works have proposed methods to automatically adapt (without human intervention) their processing logic to cope with dynamic scenario behavior [2,3]. In such a scenario, techniques supported by artificial intelligence have shown to provide good results [4,5]; however, their efficiency and their capacity to generalize their application depend on the data available to train their models. Such data must be balanced, unbiased, and sufficient to allow the model to generalize to different behaviors.

With the surge of large language models (LLMs) and their capacity to dynamically generate data, new alternatives arise for creating datasets closer to the real world to train models and enable efficient, autonomous processing. LLMs are powerful Artificial Intelligence (AI) models trained on vast amounts of data. This enables them to understand and to generate human-like data. Their knowledge and capabilities are essentially encoded within their neural network parameters during an extensive pre-training phase. However, despite their knowledge, LLMs are not intelligent in the human sense. They function by predicting the next most probable token (word or sub-word) based on the input they receive. This is where the concepts of prompts and their dependencies become crucial. To provide high-quality information, the LLM must receive context from the end user. The process of crafting effective prompts is known as prompt engineering and plays a critical role in the performance and quality of the model’s output. Manually engineering effective prompts is challenging and requires a costly, time-consuming, trial-and-error process. This highlights the need to automate prompt optimization, especially for black-box LLMs, where access to the model is limited to predictions rather than gradients.

Prompt learning optimizes model performance by tuning the discrete tokens of prompts while keeping model parameters fixed. This contrasts with fine-tuning the entire model; instead, updating only the prompt sequence offers multiple advantages, such as improved cost-effectiveness, reduced overfitting, and enhanced privacy. Most relevantly, prompt optimization aligns with black-box constraints by querying the model to update prompts without relying on the model owner’s infrastructure or risking data leakage. By searching the discrete prompt space through iterative model queries, we can automatically learn improved prompts without fine-tuning.

In this work, we propose a prompt learning process based on an evolutionary model. The process enables us to automatically discover prompts by applying a black-box approach to generate synthetic data from a reference dataset. The model exploits a genetic algorithm to explore and select the most promising prompts. The prompts are evaluated based on the semantics and diversity of the data generated relative to the reference dataset.

The main contribution of this work is a new method to generate textual disaster datasets considering semantics and diversity using a genetic model and a LLM under a black-box model.

Our results demonstrate that the evolutionary process consistently improves prompt quality over time and converges to stable solutions. We identify an optimal configuration that balances convergence quality and computational cost. Using this configuration, the GA robustly adapts to different reference texts and reliably generates synthetic data that preserves the semantic and stylistic structure of the target dataset. These findings validate the effectiveness of evolutionary prompt learning as a viable strategy for automatic, black-box LLM-driven data generation.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature on generating synthetic data and the use of metaheuristics with LLMs. Section 3 describes the problems we plan to tackle, while Section 4 introduces our proposed solution, providing both a theoretical overview and implementation details. Section 5 describes the experimental setup and evaluates performance. Section 6 provide a brief analisys on the results and their relevance. Finally, Section 7 concludes the article and discusses directions for future research.

2. Related Work

The generation of synthetic data has been extensively explored [6,7,8,9,10], most notably through approaches like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [11]. Despite their capacity to produce high-fidelity data in specific domains, GANs are computationally expensive, notoriously unstable to train, and prone to critical issues such as mode collapse [12]. Their effectiveness is critically dependent on a delicate and often non-intuitive parametrization of hyperparameters, making reproducible success a significant challenge. Concurrently, metaheuristic techniques, such as Genetic Algorithms, have also been applied [13]. However, these methods likewise incur high computational costs due to the vast number of fitness evaluations required. Furthermore, they often struggle to converge to solutions that capture the full complexity of a target data distribution, and their performance is highly sensitive to the configuration of the metaheuristic’s own set of hyperparameters (e.g., population size, selection operators), which remains a non-trivial optimization problem [14].

On the other hand, the landscape of Large Language Models (LLMs) has undergone a transformative shift, with prompt engineering emerging as a crucial technique to steer these powerful models towards desired outputs without extensive model fine-tuning. While manual prompt engineering has demonstrated remarkable efficacy, its scalability and adaptability for complex or novel data generation tasks remain significant challenges. This section reviews key developments in automated prompt optimization, particularly focusing on approaches that leverage metaheuristics and their limitations, setting the stage for our proposed research.

2.1. Automated Prompt Optimization

The advent of automated prompt engineering aims to overcome the labor-intensive nature and inherent biases of manual prompt design. Early efforts primarily focused on gradient-based methods or direct search in discrete spaces.

Gradient-Based Prompt Optimization

Our understanding of automated prompt discovery was notably advanced by the introduction of AutoPrompt [15], which demonstrated that effective prompts do not need to be handcrafted through trial and error. Instead, AutoPrompt has shown that it is possible to automatically identify small sets of discrete tokens that, when added to an input, guide masked language models toward producing the desired output. By framing prompt optimization as a gradient-driven search over tokens, AutoPrompt illustrated that meaningful prompts can be discovered systematically rather than relying solely on intuition or manual design. However, this approach depends on access to model gradients, making it suitable only in white-box settings—an assumption that does not hold for many large, proprietary, or API-restricted LLMs. Additionally, because it operates purely at the token level, AutoPrompt is limited in the expressiveness and flexibility it can achieve, leaving more nuanced or stylistically rich prompt structures out of reach.

Expanding on the notion of automated prompt learning, Prefix-Tuning [16] proposed an alternative by optimizing continuous prompt embeddings. Instead of discrete tokens, a small, task-specific sequence of continuous vectors (a “prefix”) is learned and prepended to the input, effectively guiding the LLM’s generation process. Prefix-Tuning introduces trainable continuous vectors that constitute the “prefix”, and these vectors are optimized through backpropagation to precisely steer the LLM’s output for given tasks, including text generation. Similar to AutoPrompt, Prefix-Tuning’s core mechanism is gradient-dependent, rendering it unsuitable for black-box LLM scenarios. While highly effective for fine-tuning generation, the optimized “prompts” are continuous embeddings, which lack human interpretability, meaning they cannot be directly understood, transferred, or manually refined as natural language instructions.

ProTeGi [17] represents a significant shift from heuristic engineering to systematic refinement. Addressing the non-differentiable nature of discrete text tokens, ProTeGi circumvents the inability to apply standard backpropagation by introducing the concept of textual gradients natural language feedback signals generated by the LLM that explicitly diagnose the semantic distance between the current output and the ground truth. This feedback acts as a directional vector, guiding the optimizer to perform specific, semantic edits to the prompt. By iteratively criticizing and refining the prompt based on this textual error signal, ProTeGi effectively mimics the trajectory of numerical gradient descent within a discrete semantic space, offering a directed local search alternative to stochastic black-box methods. While ProTeGi attempts to formalize prompt optimization through textual gradients, this approach inherits the classic pitfalls of local search algorithms. First, ProTeGi is highly susceptible to getting trapped in local optima. By iteratively refining a single prompt (or a narrow beam) based on immediate feedback, the method tends to perform hill-climbing in the semantic space, effectively polishing a sub-optimal solution rather than exploring radically different but potentially superior phrasing strategies.

While gradient-based approximations like ProTeGi offer efficiency, evolutionary algorithms remain uniquely advantageous for synthetic data generation tasks. Their ability to maintain a diverse population of prompts prevents mode collapse ensuring the generated synthetic data remains varied, and their black-box nature ensures compatibility with any model architecture without requiring weight access or gradient estimation.

2.2. Metaheuristic-Based Prompt Optimization

In more recent developments, metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as a highly promising avenue for prompt optimization. Their inherent capabilities in black-box optimization and their robustness in exploring complex, non-differentiable search spaces make them particularly well-suited for optimizing prompts for black-box LLMs, where gradient information is unavailable. Relevant works in this area are [18,19,20,21].

A pioneering work directly advocating for the use of metaheuristics in prompt learning is [22]. This research evaluates various metaheuristic algorithms, such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs), Simulated Annealing, and Hill Climbing, for optimizing prompts across diverse applications, including reasoning and text-to-image generation. Plum presents a generalized framework for discrete, black-box, and gradient-free prompt optimization, leveraging a suite of metaheuristic algorithms. It systematically tests several metaheuristics on tasks such as Chain-of-Thought reasoning and text-to-image generation, demonstrating their effectiveness in discovering human-understandable prompts without gradient information. However, while a significant stride, Plum primarily focuses on proving the applicability of various metaheuristics to the general prompt learning problem. The specific strategies required for evolving prompts for data generation, especially concerning nuanced quality metrics, are not deeply explored. A common challenge, particularly evident here, is the substantial computational cost incurred by numerous LLM inferences within the metaheuristic loop, especially when dealing with large populations and many generations. Furthermore, while the interpretability of evolved prompts is mentioned, challenges persist when highly complex prompt structures are generated by the algorithms.

A concrete metaheuristic-driven approach to prompt optimization is demonstrated by [23]. This work directly applies evolutionary algorithms, specifically a Genetic Algorithm, to evolve discrete text prompts, targeting improved performance in few-shot learning scenarios. EvoPrompting conceptualizes prompt tuning as an evolutionary search problem; it initiates a population of prompt candidates and iteratively applies genetic operators, such as mutation and crossover, to generate new prompt variations. The fitness of each prompt is objectively determined by the LLM’s performance on a given few-shot task, thereby guiding the evolutionary process towards more effective prompts. A key limitation is that EvoPrompting’s primary objective is to enhance few-shot learning performance, rather than explicitly focusing on the quality of synthetic data generation. While the fundamental methodology is transferable, adapting the fitness function to comprehensively evaluate the multifaceted aspects of synthetic data (e.g., diversity, realism, domain coverage, bias mitigation) requires careful and non-trivial design. Operationally, the process can be computationally intensive, as each prompt evaluation necessitates at least one LLM inference, often multiple, to assess its utility. The quality of the ultimately generated prompts can also be sensitive to the initial population composition and the specific design of the genetic operators. A similar work is presented in [24] where the authors present a framework designed to improve the accuracy of LLMs on zero-shot NER tasks. The core problem it addresses is the misalignment between an LLM’s internal understanding of an entity type and the precise human-defined label, as well as the model’s tendency to confuse similar entity types.

Furthering the exploration of metaheuristic prompt optimization, GAAPO [25] introduces a hybrid optimization framework. This framework leverages genetic algorithms to evolve prompts by integrating and orchestrating different prompt generation strategies. GAAPO employs a genetic algorithm as a high-level controller, which dynamically manages and combines a portfolio of diverse prompt generation strategies, aiming to synergistically combine the strengths of various techniques, leading to optimal prompt performance through an evolutionary process. Similar to EvoPrompting, GAAPO’s primary application is focused on enhancing task-specific performance rather than explicit data generation. The increased complexity associated with managing multiple prompt generation strategies within a genetic algorithm can introduce significant overhead and reduce the transparency of the optimization process. The high computational cost associated with LLM interactions remains a notable barrier for its widespread practical application.

Promptbreeder [26] is a self-referential evolutionary framework that automatically optimizes LLM prompts without manual intervention. It treats prompt engineering as an evolutionary process, maintaining a population of task prompts and evaluating their fitness on a training set. The innovation is that the mutation and crossover operators are themselves mutation prompts that instruct an LLM on how to modify the task prompts. Critically, these mutation prompts also co-evolve alongside the task prompts, creating a self-referential loop where the system not only improves the solution (the task prompt) but also improves its own method for finding better solutions (the mutation prompt).

For a broader perspective on the integration of these fields, ref. [27] offers a comprehensive overview. This survey discusses how evolutionary computation techniques can enhance various aspects of LLMs, including prompt engineering. This survey provides a thorough review of the synergies between Evolutionary Computation (EC) and LLMs, delving into how EC can be utilized to optimize components of LLMs, such as prompts, hyperparameters, and even architectural designs. Conversely, it also explores how LLMs can enhance EC methodologies, thus offering a valuable, high-level understanding of the reciprocal relationship between these two powerful domains. However, as a survey, its primary role is to provide a broad overview rather than in-depth methodological details or novel contributions to prompt evolution. While it acknowledges the significant potential for prompt optimization, it does not specifically delve into the nuanced challenges and specific considerations unique to evolving prompts for data generation as the core objective.

Despite the compelling advancements in automated prompt optimization utilizing metaheuristics, several critical limitations and persistent research gaps exist, particularly when the ultimate objective is the generation of high-quality synthetic data. The complex fitness function design for data generation is a major hurdle; evaluating the quality of generated data is inherently more intricate than assessing performance on discrete classification or question-answering tasks, as metrics must consider a multitude of factors, including diversity, realism, adherence to specific distributions, privacy preservation, and utility for downstream tasks. Designing a robust, comprehensive, and computationally efficient fitness function that encapsulates these multifaceted aspects for metaheuristic optimization remains a significant challenge. Another substantial concern is the high computational cost of LLM inferences. Metaheuristic algorithms, by their nature, demand numerous evaluations of candidate solutions (prompts), each typically necessitating at least one, and often several, LLM inferences to generate the desired data. This process is computationally expensive and time-consuming, especially when dealing with large-scale LLMs or generating substantial datasets, thereby limiting the practical scalability of such approaches.

Furthermore, navigating the exploration–exploitation trade-off in prompt space presents a significant challenge. The search space for effective prompts is vast, high-dimensional, and frequently non-linear. While metaheuristics are adept at global exploration, they may struggle with premature convergence to local optima. Balancing exploration (to discover novel data characteristics) with exploitation (to refine high-quality data) requires meticulous tuning of metaheuristic operators (e.g., mutation, crossover) to effectively navigate this complex and expansive search space. The interpretability and control of evolved prompts also pose a challenge; even when metaheuristic-evolved prompts are human-readable, the underlying reasoning for why certain prompt structures are effective often remains opaque, hindering human understanding, subsequent manual refinement, and crucial control over the data generation process, which is particularly critical for sensitive or regulated applications.

Our proposal is designed to address these identified limitations by developing a novel metaheuristic framework specifically tailored for evolving prompts. This framework will prioritize the generation of high-quality synthetic data through the implementation of robust fitness evaluation strategies and efficient exploration techniques within the prompt space.

3. Problem

We address the problem of automatic text data generation using large language models (LLMs) by employing an evolutionary approach to guide prompt learning. Our focus is on data related to natural disasters, a particularly relevant domain in Chile, where events such as earthquakes, landslides, and wildfires occur frequently and have a significant impact. During such events, timely online data analysis is essential in phases such as mitigation and recovery, as it supports rapid response, planning, and efficient resource allocation, ultimately aiming to reduce the disaster’s impact.

Stream processing systems (SPS) play a central role in enabling real-time data analytics in these scenarios. However, SPS must operate under strict quality of service (QoS) constraints, which demand dynamic adaptation of their internal logic to sustain performance. Several adaptive models have been proposed in the literature [2,3,28,29], including heuristic-based strategies and approaches that leverage artificial intelligence (AI) [4,5]. While AI-based methods generally provide superior results, they often require extensive offline training, during which the quality and diversity of training data are crucial for model performance and generalization across different disaster contexts.

To address this limitation, we propose a prompt learning method that automatically generates synthetic text data using an LLM-agents model, guided by metaheuristics in a black-box optimization setting. This approach aims to enrich training datasets and enhance the generalization capabilities of AI-driven adaptive SPS models.

4. Evolutionary Model

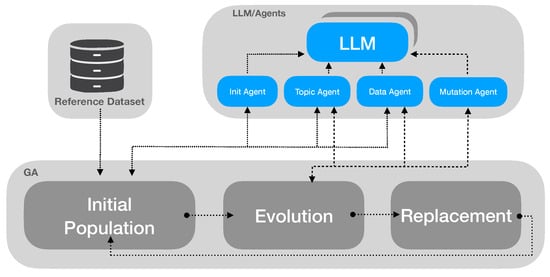

The proposed model connects the use of LLMs with an evolutionary model, following a multi-agent approach, to automate the prompt generation for creating synthetic text datasets. Our approach applies a Genetic Algorithm (GA). Our proposal is presented in Figure 1. It is implemented following a multi-agent approach. We have three main actors: (1) the LLM, (2) the agents, and (3) the genetic algorithm.

Figure 1.

Evolutionary model. This evolutionary model is instantiated as a Genetic Algorithm (GA). We follow a black-box approach with the LLM, and a multi-agent model is applied to decouple the system interactions.

4.1. Large Language Model (LLM)

Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown a notable capacity in natural language processing tasks. Considering the potential of these models, we plan to exploit them to create textual (micro-blogging) data close to a real reference dataset, following a black box approach. In this work, we particularly focus on one model called LLaMA 3 (with 8b parameters) [30,31] however, our approach can be extended to use any other LLM.

We maintain the LLM in its pre-trained, zero-shot configuration throughout the entire process, treating it strictly as a non-differentiable black-box function. This decision is paramount for two reasons: it guarantees the reproducibility and broad applicability of the proposal, and prevents the introduction of methodological bias that could arise from using a specially re-trained or fine-tuned LLM during the prompt optimization process.

4.2. Agents

The integration of a multi-agent system provides a structured, modular, and superior approach to managing the complex interactions between the GA and the LLM for prompt optimization. Instead of a monolithic control loop, the process is decentralized into specialized, cohesive agents. For instance, the Prompt Agent manages the internal representation and formatting of the prompt string for both the GA encoding and the LLM API call; the Data Generation Agent is solely responsible for executing the LLM invocation and handling the output stream to produce the synthetic dataset; the Keywords Agent can provide focused linguistic analysis or constraints extracted from the reference data to bias the initial population; and the Mutation Agent which supports the evolutionary mutation operator (e.g., find semantically similar tokens). This decomposition offers enhanced robustness, debuggability, and flexibility by enforcing a clear separation of concerns. Furthermore, it facilitates future extensions, such as easily integrating dynamic temperature control or LLM selection, without refactoring the core GA logic, thereby transforming a complex, coupled system into a highly maintainable and adaptable evolutionary framework.

4.3. Genetic Algorithm

To systematically optimize the LLM prompts, we employed a traditional Genetic Algorithm, formally structured around a three-stage iterative process: Initial Population, Evolution, and Replacement. This standard evolutionary approach begins by constructing an initial population of prompt candidates. Following initialization, the system enters the evolution stage, where the fitness of each prompt is evaluated by having the LLM generate a dataset and quantifying its statistical fidelity against the reference data. Prompts are then refined through established genetic operators—specifically crossover and mutation—to create a new, potentially superior generation. Finally, the update stage appply selection mechanism to choose individuals for the next iteration, replacing lower-performing individuals with the newly generated offspring, thereby driving the collective population toward prompts that maximize the statistical similarity of the synthetic output. This structured, cyclical process ensures an efficient and measurable search for optimal prompt configurations.

4.3.1. Initial Population

The first stage of our proposed approach involves generating an initial population of individuals for the evolutionary model. The efficacy of a genetic algorithm is highly dependent on the diversity and quality of its initial population. In our methodology, the initial population consists of a set of N distinct prompts (or individuals), each serving as a candidate solution for generating text datasets that mimic the statistical and thematic characteristics of a given reference dataset. The generation of this initial population is a critical step, designed to balance the need for broad exploration of the prompt space with the inclusion of potentially high-performing prompts.

Each individual represents a prompt that will be progressively optimized by the algorithm. Furthermore, each prompt follows a pre-defined and manipulable structure, which facilitates controlled modifications throughout the algorithm’s iterations and its convergence.

To effectively guide the evolutionary process within the genetic algorithm (GA) while maintaining semantic coherence and promoting meaningful diversity, we define a structured representation for each prompt, which we refer to as an “individual” in our population. This structured enables a controlled and semantically meaningful evolution of prompts. Each prompt, , is a structure of semantically categorized components: a role, a topic, and an action.

where:

- represents the role component, defining the persona or perspective the LLM should adopt during text generation (e.g., “As a medical professional…”, “In the style of a journalist…”, “From an academic viewpoint…”). This component aims to influence the tone, vocabulary, and overall framing of the generated text, aligning it with specific stylistic requirements of the reference dataset. The set of possible roles, , is predefined based on an analysis of the reference text characteristics or domain expert input.

- represents the topic component (or keywords), specifying the central subject matter or theme for the text to be generated. This component directly anchors the LLM’s output to the content domains present in the reference dataset. The set of possible topics, , can be dynamically derived from a reference text.

- represents the action component, this represent what the specific role selected is doing. These actions dictate what is the speaker trying to communicate. The set of possible actions, . Actions are also derived from the reference text.

The total prompt is constructed by concatenating these components (e.g., “. Generate text about . .”). This structured design provides a clear framework for genetic operations (mutation and crossover) to act upon specific semantic units rather than arbitrary character sequences, thereby preserving semantic integrity during evolution.

The initial population generation leverages this structured representation to ensure both diversity and relevance to the reference dataset. Each individual prompt in the initial population is generated through the following process:

- Reference Text Selection: A text snippet, , is randomly selected from the reference dataset, . This ensures that the initial prompts are directly grounded in the actual data characteristics we aim to replicate.

- Component Instantiation: For the selected text snippet :

- A Role component () is randomly selected from the predefined set .

- A Topic component () is extracted or inferred from . This could involve methods such as named entity recognition to identify key entities, topic modeling to identify dominant themes, or simple keyword extraction from . In our model, we provide the topic of reference text. The topic extraction from the reference text is supported by the LLM through an agent. The provided topic is then integrated into the prompt structure.

- An Action component () is extracted from the reference text. The action extraction from the reference text is supported by the LLM through an agent.

- Prompt Refinement: The instantiated components () are then fed into the LLM as an initial seed. The LLM is then prompted to refine this structured input into a coherent, syntactically correct, and semantically richer prompt that incorporates the essence of the selected reference text . This step leverages the LLM’s natural language understanding and generation capabilities to produce a human-readable and effective prompt from the structured components. For instance, if is a news article about climate change, and the components are (As a scientist, Climate change impacts, Explain the implications), the LLM might generate a prompt like: “As a climate scientist, thoroughly explain the long-term implications of climate change as observed in recent research.” This LLM-guided refinement ensures that the initial prompts are not merely concatenated keywords but semantically fluid and actionable instructions for subsequent text generation.

This systematic approach to initial population generation, by coupling structured prompt design with LLM-guided refinement based on reference data samples, allows us to create a diverse yet semantically grounded set of initial candidate prompts. This diversity is crucial for enabling the genetic algorithm to explore a wide array of prompt configurations effectively, while the semantic grounding ensures that the prompts are relevant and capable of eliciting high-quality text generation from the LLM from the outset.

4.3.2. Evolution

The genetic algorithm’s evolutionary phase begins subsequent to initial population generation, proceeding through iterative stages of fitness determination, selection of individuals, and the execution of genetic operations.

Fitness Calculation

The fitness of each individual prompt in the population is quantitatively assessed based on its ability to elicit text from an LLM that closely resembles the characteristics of the reference dataset. This assessment involves two primary steps:

- Text Generation: Each prompt is provided as input to the LLM, which then generates a corresponding text output, denoted as .

- Similarity Measurement: The generated text is then compared against a randomly selected text snippet from the reference dataset . The similarity is quantified using the BERTScore metric [32]. BERTScore leverages contextual embeddings from pre-trained BERT models to compute a robust similarity score between two texts, capturing both semantic and syntactic alignment. The fitness function, , for a given prompt is thus defined asThis allows us to control the semantic coherence of the generated samples throughout the evolutionary process. While coherence is critical, it is equally important that the generated dataset maintains a certain level of diversity.This process is repeated for each individual in the current population to obtain their respective fitness values.

Although the reference snippet is randomly selected, it remains fixed for the entire execution of the GA. This ensures that all individuals in a run are evaluated under the same reference condition, maintaining a stable and noise-free fitness landscape, i.e., . The goal of the fitness function is not to approximate the full dataset distribution with a single sample, but to provide a stable semantic reference allowing the GA to compare individuals relative to the same example. Because the snippet does not change, the evolutionary process can consistently determine which prompts produce outputs that are more semantically related to the reference snippet. Furthermore, BERTscore captures similarity at a semantic level, making the fitness evaluation robust even if the selected snippet reflects only a local portion of the dataset. By using this approach, we preserve stability within each run while allowing different random initializations to explore different regions of the search space across multiple runs.

Genetic Operators

Traditional genetic operators, crossover and mutation, are applied to the selected parents to generate the new generation of individuals. These operators are designed to act on the structured prompt components () to maintain semantic integrity.

The individuals for the next generation are generated by applying genetic operators to parents selected from the current population. Parent selection is performed using a tournament selection. A small subset of individuals (the tournament size) is randomly chosen from the population, and the individual with the highest fitness within this subset is selected as a parent. This method is less susceptible to scaling issues than roulette wheel selection [33,34].

- Crossover: This operator combines genetic material from two parent prompts to create offspring. Two parent individuals, and , are selected using a tournament selection. A crossover point is then randomly determined, and components are interchanged between the parents to produce two offspring. For instance, a single-point crossover could result in offspring like:More complex crossover mechanisms, such as two-point crossover or uniform crossover, can also be applied to exchange multiple components or specific tokens within components. The key is that the exchange occurs at predefined component boundaries or within semantically coherent token sets to preserve the prompt’s overall structure and meaning. Crossover is performed on selected parents individuals, subject to a crossover probability, .

- Mutation: This operator introduces random variations into a single individual to explore new areas of the search space and prevent premature convergence. A single individual is selected using a tournament selection. A random component (e.g., , , or ) and a specific token within a component is chosen for mutation. We implement an LLM-driven semantic mutation operator to introduce novel variations while preserving contextual plausibility. When an individual is selected for mutation, a single token is randomly sampled. This token, along with its surrounding contextual phrase, is transferred to a dedicated Mutation Agent. This agent then formulates a query to the LLM, tasking it to generate a list of semantically similar tokens that are valid and coherent within that specific context. A token from the LLM’s response is then selected to replace the original token, completing the mutation. This approach ensures that mutations constitute intelligent, context-aware explorations of the solution space rather than simple stochastic noise, thereby preventing the introduction of non-viable or nonsensical data artifacts. Mutation is performed on the selected individual, subject to a mutation probability, .

4.4. Replacement/Update

The population update or replacement phase concludes each iteration of the evolutionary loop and is critical for driving the algorithm toward convergence. This phase determines the composition of the population for the subsequent generation. In our classical GA implementation, we utilize a generational replacement strategy combined with elitism. This approach is crucial as it guarantees monotonic improvement in the population’s best-found solution. Specifically, the n offspring, generated via the crossover and mutation operators, replace the n parent from the current population. However, to prevent the stochastic loss of high-performing individuals (i.e., individuals that produced data with high fitness scores), the top k “elite” individuals from the parent generation are identified and copied directly into the new generation, typically replacing the k worst-performing offspring. This mechanism ensures that the GA’s progress is non-regressive while allowing the remainder of the population to be fully replaced by new, exploratory solutions.

5. Experiments

The proposed evolutionary prompt engineering framework was evaluated across a series of experimental scenarios. The system utilizes a local, containerized LLM environment powered by Ollama 0.6.0, specifically employing a model from the 8-billion parameter class (Llama3) known for balancing computational efficiency with strong generative capabilities. The inference environment is a dedicated Linux (Ubuntu) machine configured with 32 GB of RAM and accelerated by dual NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU, ensuring high-throughput data generation essential for the iterative fitness evaluation inherent in the Genetic Algorithm. The target reference distribution for synthetic data generation is the IEEE COVID-19 Tweets Dataset [35], a large-scale, real-world social media corpus concerning the pandemic. Our evaluation used a sample of approximately four million (4M) tweets, making the task a challenging test of the LLM’s ability to accurately capture the statistical nuances and high-dimensional features of public discourse during a global crisis. For the critical process of hyperparameter optimization, we employed a systematic one-factor-at-a-time methodology, which isolates the impact of each GA parameter on the convergence and final prompt fidelity. To guarantee the statistical reliability of the findings and mitigate variance inherent in stochastic search, each distinct experiment was executed five times with different random initial seeds, and the averaged results are presented. The source code of our implementation is available in https://github.com/NewGrumbly/MDPI-EVOLMD accessed on 7 November 2025.

5.1. Number of Generations

The total number of generations (G) is a fundamental hyperparameter that dictates the algorithm’s runtime and its potential for convergence. This parameter directly controls the trade-off between solution quality and computational cost. A G value that is too low risks premature convergence, terminating the evolutionary process before the population has had sufficient time to refine high-fitness solutions. Conversely, an excessively high G value leads to diminishing returns, where the population’s fitness may plateau, and subsequent generations consume significant computational resources (particularly LLM queries) without yielding substantial improvements.

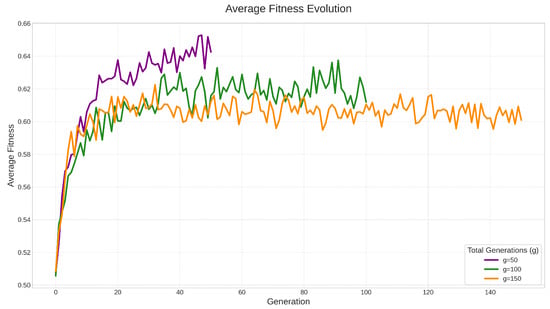

To identify the point of optimal convergence, we evaluated the algorithm’s performance across three distinct experimental runs, setting the termination condition at generations, respectively. This allowed us to map the fitness improvement over time and determine the most resource-efficient setting that reliably produces a high-quality data population.

The results of our generation count analysis revealed a clear relationship between runtime and convergence (Figure 2). The experiment limited to generations was found to be insufficient; the population’s average fitness had not yet plateaued and exhibited unstable behavior, indicating that the evolutionary process was terminated prematurely.

Figure 2.

Evolution of average population fitness for different generation (G) termination conditions. The plot compares three independent experimental runs: (purple), (green), and (orange).

In contrast, both the and scenarios demonstrated stable convergence, with both runs achieving comparable maximum fitness values. Since the run yielded no significant improvement in final data quality over the run, we identified the additional 50 generations as providing diminishing returns. Consequently, we selected as the optimal value for our framework, as it achieves robust convergence while offering a superior computational trade-off by minimizing unnecessary LLM queries. Table 1 presents the average total execution time for our tests.

Table 1.

This table compares the total execution time required to complete the evolutionary process for each evaluated generation count (G).

5.2. Population Size

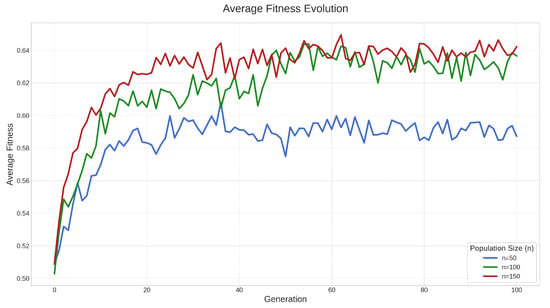

We performed a sensitivity analysis to establish an optimal population size (N), a hyperparameter of critical importance in evolutionary algorithms. The population size directly dictates the genetic diversity of the agent pool and governs the fundamental trade-off between exploration (discovering novel solutions) and exploitation (refining known good solutions). In our framework, this parameter is particularly relevant as each individual evaluation necessitates a query to the LLM, creating a direct scaling relationship between N and the computational cost per generation. A population that is too small () risks premature convergence to a sub-optimal solution due to insufficient diversity. Conversely, an excessively large population () may provide diminishing returns in solution quality while incurring prohibitive computational overhead. To identify the most effective balance for our data generation task, we empirically evaluated three distinct configurations: .

As depicted in Figure 3, the evaluation of population sizes reveals distinct performance trade-offs. The configuration (blue line) demonstrates significantly hindered performance, exhibiting premature convergence. Its average fitness plateaus early, struggling to surpass a value of 0.60, which is considerably lower than the fitness achieved in the other scenarios. In contrast, both the (green line) and (red line) configurations achieve a much higher average fitness, successfully converging to a similar and more desirable plateau (fluctuating roughly between 0.62 and 0.64). Although both runs evidence that they can reach a comparable fitness over time, the run provides no significant advantage over the run. Therefore, we selected as the ideal population size, as it offers a superior computational trade-off, achieving robust fitness results without the additional computational overhead incurred by 150 individuals.

Figure 3.

Evolution of average population fitness over 100 generations. The plot compares the performance of three different population sizes (N): (blue), (green), and (red).

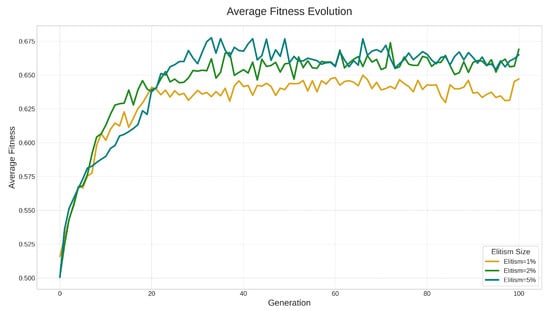

5.3. Elitism

We further analyzed the impact of elitism size on the evolutionary process. Elitism controls the proportion of top-performing individuals that are directly preserved in the next generation, ensuring that high-quality prompt structures are not lost due to stochastic genetic operations. We evaluated elitism sizes of the total population. As shown in Figure 4, all configurations exhibit steady improvement in average fitness, but their convergence patterns differ. The smallest elitism value (1%) leads to lower final fitness, indicating insufficient preservation of high-quality individuals and a tendency toward premature drift. Increasing elitism to 2% improves stability and final fitness but still allows some degradation during later generations. The largest elitism size (5%) consistently achieves the highest and most stable fitness plateau, suggesting that a stronger preservation mechanism benefits convergence by reinforcing advantageous prompt patterns. Therefore, we select an elitism size of 5% of the population as the optimal configuration.

Figure 4.

Evolution of average population fitness over 100 generations. The plot compares the performance of three different elitism size (k): (yellow), (light green), and (dark green).

5.4. Tournament Size

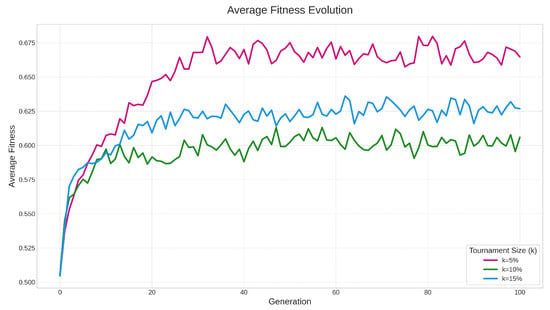

We study the impact of the tournament size (k), a critical hyperparameter that directly modulates selection within the genetic algorithm. The tournament size defines the number of individuals randomly sampled from the population to compete for selection. This parameter governs the trade-off between population diversity and convergence speed. A small tournament size () exerts low selection pressure, as even lower-fitness individuals have a reasonable chance of being selected, which promotes genetic diversity but can slow convergence. Conversely, a large k imposes high selection pressure, rapidly propagating high-fitness individuals but increasing the risk of premature convergence to a local optimum. Given that our fitness evaluation is computationally expensive (requiring LLM queries), finding the optimal balance is essential. We empirically evaluated three tournament size configurations, defined as a percentage of the total population (N): .

The results of our analysis on tournament size (k), presented in Figure 5, demonstrate the relationship between selection pressure (as controlled by k) and final solution quality. The configuration (green line), representing an intermediate selection pressure, exhibited the weakest performance, prematurely converging to the lowest fitness plateau at approximately . This was considerably lower than the other two scenarios. We believe that might be hitting a “sweet spot” that is actually a suboptimal balance for our specific problem providing insufficient exploration and explotation. Both the (blue line) and (pink line) configurations achieved superior results, with the (pink line) run clearly yielding the best performance, stabilizing at the highest average fitness of . A lower selection pressure allows for a much higher chance that individuals with slightly lower fitness still get selected. This is beneficial early in the run because it helps maintain diversity in the population. The algorithm avoids premature convergence and can explore a wider range of the prompt space, potentially finding a globally better, but harder-to-reach, optimum later on. On the other hand, larger tournament size means higher selection pressure. This is very effective at quickly exploiting good solutions. The best individuals are chosen more often, rapidly driving the population towards promising regions of the fitness landscape. It works well if the initial generations already contain some high-quality ’seed’ prompts, allowing the GA to quickly refine them into excellent solutions. Given that the setting provides the best fitness outcome and, critically, also represents the lowest computational cost for the selection operator, it was clearly identified as the optimal value for our framework.

Figure 5.

Evolution of average population fitness over 100 generations. The plot compares the performance of three different tournament sizes (k): (pink), (green), and (blue).

5.5. Crossover and Mutation

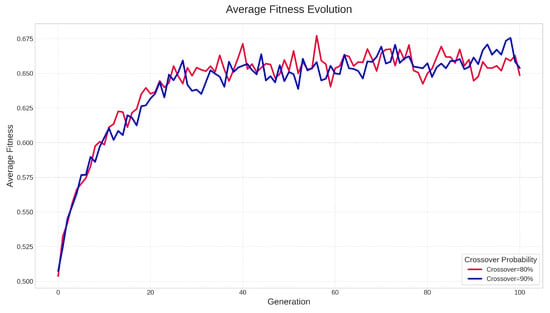

We also performed a sensitivity analysis on the crossover probability (), a key hyperparameter that regulates the balance between exploration and exploitation during reproduction. In this context, controls the proportion of offspring generated by recombining parent prompts versus directly propagating high-performing individuals to the next generation. Higher values of encourage exploration by producing more novel prompt combinations, but may also disrupt well-adapted individuals if excessive.

We evaluated two high-probability settings, and . As shown in Figure 6, both configurations yield stable convergence patterns, but the run with consistently achieves a slightly higher average fitness plateau. This indicates that offers a more effective balance, enabling beneficial prompt structures to persist while still introducing sufficient variability for continued search. Although this configuration results in a marginal 3% increase in computational cost, its superior final fitness justifies the trade-off.

Figure 6.

Evolution of average population fitness over 100 generations. The plot compares the performance of two different crossover probabilities: (red), (blue).

Accordingly, we select as the default crossover probability for our evolutionary model.

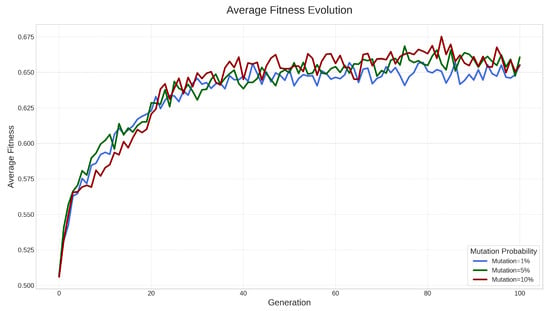

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis on the mutation probability (), a key GA parameter that regulates search-space exploration and helps prevent premature convergence. In our approach, determines how frequently new semantic variations are introduced into candidate prompts. Setting too low limits diversity and may lead the population to stagnate around sub-optimal solutions, whereas overly high values can excessively disrupt well-adapted individuals, hindering the algorithm’s ability to exploit high-quality prompt structures.

We evaluated mutation rates of , , and . As shown in Figure 7, all configurations improve average fitness over generations, but with different convergence profiles. The lowest rate () yields slower improvement and converges to a lower final fitness, indicating insufficient exploration. Conversely, the highest rate () achieves slightly higher peak fitness but also introduces greater fluctuation, reflecting instability in the evolutionary search. The intermediate value () provides the best overall balance, achieving competitive fitness gains while maintaining stable convergence and reduced computational overhead.

Figure 7.

Evolution of average population fitness over 100 generations. The plot compares the performance of two different mutation probabilities: (blue), (green) and. (red).

Therefore, we select as the default mutation probability for our evolutionary process, as it ensures adequate genetic diversity without inducing excessive stochastic perturbation.

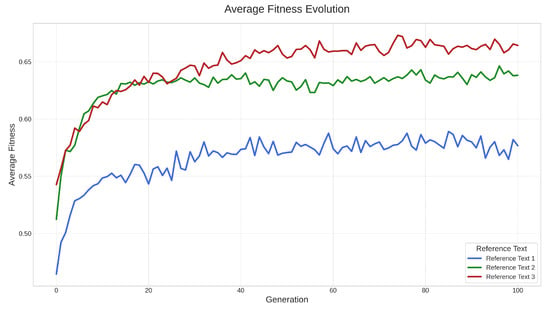

5.6. Optimal Configuration

To evaluate the robustness and generality of the proposed evolutionary prompt optimization method, we applied the GA using the optimal configuration identified in the preceding sensitivity analyzes to three distinct reference texts with different thematic and stylistic characteristics. Reference texts were randomly chosen from the reference dataset. The average fitness evolution for each reference text, shown in Figure 8, demonstrates that the GA consistently improves prompt quality across all scenarios, confirming the adaptability of the approach. However, the magnitude of the final fitness plateau varies across reference texts. Reference 3 (red line) achieves the highest average fitness, indicating that its linguistic and structural patterns are more amenable to recombination and mutation within the prompt search space. Reference 2 (green line) reaches a slightly lower but still stable fitness level, while Reference 1 (blue line) converges to the lowest fitness plateau, suggesting that its stylistic characteristics are more challenging to approximate through prompt-based generation. These results highlight that, although the GA reliably converges in all cases, the achievable quality of synthetic data remains influenced by the inherent complexity and regularity of the target reference text.

Figure 8.

Average fitness evolution over 100 generations for three different reference texts using the optimal GA configuration.

Our results show that the metaheuristic-guided prompt learning process is capable of exploring a meaningful spectrum of text outputs with varying degrees of similarity and diversity relative to the reference text. To illustrate this, we report the reference seed text alongside a representative subset of evolved individuals grouped by fitness ranges: [0.9–0.8], (0.8–0.7], and (0.7–0.6].

- Reference Text 1: “We’re rationing food. Only one store open and it’s chaos”

Generated texts:

- Range [0.9–0.8]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.8696Generated Data (): “We’re rationing PCR tests. Only one testing center open and it’s chaos”

- –

- Fitness: 0.8537Generated Data (): “As leaders, we’re rationing masks. Only one distribution center open and it’s chaos”

- Range (0.8–0.7]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.7952 Generated Data (): “We’re prioritizing medical masks. Only one production facility open and it’s a struggle”

- –

- Fitness: 0.7864Generated Data (): “We’re prioritizing resources. Only three hospitals open and it’s a struggle”

- Range (0.7–0.6]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.6995Generated Data (): “We’re adapting our emergency protocols. Only one distribution center open and it’s chaos, but we’ll ensure a fair share for all”

- –

- Fitness: 0.6806Generated Data (): “We’re struggling to get by. Food is scarce, only one market open, and tensions are running high”

- Reference Text 2: “We’re organizing a cleanup drive in the park at 9 AM”

Generated texts:

- Range [0.9–0.8]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.8672Generated Data (): “We’re organizing a vaccination campaign in the park at 9 AM.”

- –

- Fitness: 0.8432Generated Data (): “We’re organizing a mandatory cleaning and inoculation event at 9 AM, ensuring a thorough cleanup drive in the park outside”

- Range (0.8–0.7]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.7986Generated Data (): “As a responsible organization, we’re organizing a morning cleanup drive in the park at 9 AM, ensuring public safety during our neighborhood lockdown efforts”

- –

- Fitness: 0.72048Generated Data (): “As part of our efforts to boost community resilience during lockdowns, we’re organizing a morning cleanup drive in the park at 9 AM to promote unity among residents and maintain public safety”

- Range (0.7–0.6]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.6980Generated Data (): “Join us as we come together to boost resilience in our residential district during the shutdown. We’re organizing a community park cleanup drive at 9 AM to promote public safety and community pride”

- –

- Fitness: 0.6674Generated Data (): “As a responsible organization, we’re mobilizing a community cleanup drive in our residential district’s central park at 9 AM to promote public safety, foster neighborhood connections, and enhance overall resilience amid the pandemic”

- Reference Text 3: “Please conserve water as our treatment facilities are still offline”

Generated texts:

- Range [0.9–0.8]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.8084Generated Data (): “Please follow water conservation measures as our treatment facilities remain offline until further notice”

- Range (0.8–0.7]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.7636Generated Data (): “Please follow our visual guidelines and conserve water as our treatment facilities are still offline, ensuring a safe journey during this COVID-19 incident.”

- –

- Fitness: 0.7484Generated Data (): “Please prioritize water conservation as our facilities are still offline, vital updates on essential services will be shared regularly”

- Range (0.7–0.6]:

- –

- Fitness: 0.6996Generated Data (): “Conserve water during this critical quarantine period as our treatment facilities remain offline. Essential protocols for tracing and communication are in place”

- –

- Fitness: 0.6599Generated Data (): “As a responsible organization, we urge you to conserve water amid the ongoing pandemic crisis and lockdown. Our treatment facilities are still offline, and every drop counts in maintaining essential response efforts”

We observe that individuals with higher fitness scores tend to closely approximate the semantics and phrasing of the reference, but at the expense of lexical and structural diversity. In contrast, individuals in the lower (yet still acceptable) fitness range—particularly those above maintain a stronger balance between semantic fidelity and generative variation, resulting in outputs that preserve the core meaning while exhibiting greater expressive richness. This pattern supports the premise that intermediate fitness regions are the most suitable for generating high-quality synthetic text datasets that retain conceptual alignment without introducing excessive redundancy.

6. Discussion

Our experimental results show the efficacy of the proposed evolutionary framework for automated prompt optimization in generating synthetic text data, particularly in balancing semantic fidelity and generative diversity. This discussion focuses on the strategic parameter values selected through sensitivity analysis and provides a quantitative interpretation of the output text quality.

6.1. Parameter Selection and Influence on Convergence

Based on the sensitivity analysis presented in our experiments, the selection of optimal hyperparameter values was a strategic necessity to manage the trade-off between solution quality and computational cost and to guide the Genetic Algorithm (GA) to robust convergence. We strategically chose generations and a population size as the optimal compromise, effectively avoiding the premature convergence observed with sub-optimal settings (e.g., ) while simultaneously circumventing the diminishing returns and excessive LLM query costs associated with larger configurations (e.g., ). A high elitism size of was critical, ensuring that high-performing prompt structures were persistently carried over to subsequent generations, thereby achieving the highest and most stable fitness plateau by reinforcing advantageous prompt patterns. Crucially, a low tournament size of provided the best fitness outcome by reducing selection pressure, which in turn maintained essential genetic diversity and allowed the algorithm to explore a wider, globally better range of the prompt space, preventing rapid convergence to sub-optimal local optima. Finally, the reproductive operators were tuned to an effective intermediate balance with a crossover probability and a mutation probability , which, coupled with the LLM-driven semantic mutation operator, ensured that exploration introduced semantically plausible variations without excessively destabilizing high-quality prompt individuals.

6.2. Quantitative Analysis: Diversity and Semantics

The quality of the generated output text is quantitatively assessed through a critical trade-off between semantic fidelity and lexical diversity, employing two widely recognized metrics: Jaccard Similarity for measuring text diversity and TF-IDF Cosine Similarity for evaluating semantic preservation. The Jaccard Similarity [36] measures the overlap of unique words (tokens) between the generated text and the reference text. A score of means the word sets are identical. On the other hand, TF-IDF Cosine Similarity [37] measures the angular distance between the vector representations of the texts, where words are weighted by their Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF). It gives higher weight to words that are rare across the entire set of texts, making it a more semantically nuanced measure than simple Jaccard.

For our analysis we considered the text references and the generated texts presented in the previous section:

- Reference text 1: “We’re rationing food. Only one store open and it’s chaos”Table 2 presents the diversity and similarity results among reference text 1 and the generated ones. Here we can observe, based on both metrics, that generated text can preserve semantics while creating diverse texts.

Table 2. Similarity Metrics of Generated Texts relative to Reference Text 1.For example, text retains the “rationing” and “chaos” concepts and the core structure, but adds a new introductory phrase, “As leaders” which slightly lowers the similarity compared to .

Table 2. Similarity Metrics of Generated Texts relative to Reference Text 1.For example, text retains the “rationing” and “chaos” concepts and the core structure, but adds a new introductory phrase, “As leaders” which slightly lowers the similarity compared to .

- Reference text 2: “We’re organizing a cleanup drive in the park at 9 AM”Table 3 presents the diversity and similarity results among reference text 2 and the generated ones. Here we can observe a more stable behavior in terms of both metric: semantics are better preserved compared to the initial case of reference text 1, however diversity is limited for and . For this scenario, presents a better balance between the metrics. preserves the core action “cleanup drive” but frames it within a new “public safety/lockdown” context. The meaning of the action is kept, but the surrounding purpose is shifted.

Table 3. Similarity Metrics of generated texts relative to Reference Text 2.

Table 3. Similarity Metrics of generated texts relative to Reference Text 2.

- Reference text 3: “Please conserve water as our treatment facilities are still offline”Table 4 presents the diversity and similarity results among reference text 3 and the generated ones. Here we can observe a similar behavior compared to reference text 1 where and present a good balance between the metrics. exhibits the best semantic preservation. It retains the precise cause-and-effect relationship established in the reference text: “conserve water as our treatment facilities are still offline” and adds context introducing visual guidelines and COVID-19 without disrupt the primary instruction.

Table 4. Similarity Metrics of generated texts relative to Reference Text 3.

Table 4. Similarity Metrics of generated texts relative to Reference Text 3.

From the previous results we observed consistent trends regarding the diversity and semantic preservation of the texts generated by the evolutionary approach, based on the Jaccard Similarity and TF-IDF Cosine Similarity metrics.

In general, for generated text and we can reach a good balance between diversity and semantic preservation.

7. Conclusions

This work presents an evolutionary framework for automated prompt optimization aimed at generating synthetic text datasets using Large Language Models under a black-box setting. By structuring prompts into semantically meaningful components and applying a Genetic Algorithm to evolve them over successive generations, our approach enables the discovery of effective prompts without relying on model fine-tuning or manual engineering. The integration of semantic mutation and modular agents allowed us to explore the prompt search space efficiently while preserving linguistic coherence.

Through a systematic sensitivity analysis, we identified an optimal configuration for the evolutionary process, balancing convergence quality and computational cost. The results demonstrated that the proposed method consistently improves the semantic similarity between generated and reference data, while also highlighting that the achievable quality of synthetic data depends on the structural complexity of the target text. These findings confirm that evolutionary prompt learning is a viable approach for synthetic data generation, particularly in scenarios where access to LLM internal parameters is restricted.

Overall, this work contributes a reproducible, modular, and generalizable framework for synthetic dataset generation, supporting downstream applications such as adaptive stream processing, where data quality and variability play a critical role. The approach opens new pathways for leveraging LLMs beyond direct text generation, positioning prompt evolution as a powerful tool for data-centric model development.

For future work we will prioritize enhancing the framework’s computational efficiency and refining the quality of the generated data: First, we plan to investigate novel fitness functions designed explicitly to reduce the high computational overhead of LLM queries. These functions will be engineered to strike a more sophisticated balance between semantic plausibility and population diversity. Second, we will explore shifting the granularity of the evaluation; by assessing fitness at the sentence level rather than on a per-token basis, we hypothesize that we can significantly decrease the number of evaluative computations. Finally, we intend to move beyond traditional selection mechanisms by integrating Reinforcement Learning (RL). An RL agent could be trained to learn a dynamic selection policy, learning to select individuals based not only on their current high fitness (exploitation) but also on their potential to contribute to long-term population diversity and novel solution discovery (exploration), thereby enabling a more intelligent and adaptive evolutionary search.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.H., V.R., N.M. and P.S.; methodology, E.R. and N.H.; software, N.M. and P.S.; validation, N.H., V.R. and N.M.; formal analysis, N.H., V.R. and E.R.; investigation, N.H., E.R. and V.R.; resources, P.S.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.H.; writing—review and editing, N.H.; visualization, N.H.; supervision, N.H.; project administration, N.H. and V.R.; funding acquisition, N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the STIC-AmSud ITERATION-D project number 24-STIC-13, and Proyecto Enlace UDP 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- García, S.; Ramírez-Gallego, S.; Luengo, J.; Benítez, J.M.; Herrera, F. Big data preprocessing: Methods and prospects. Big Data Anal. 2016, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo Russo, G.; Cardellini, V.; Lo Presti, F. Hierarchical auto-scaling policies for data stream processing on heterogeneous resources. ACM Trans. Auton. Adapt. Syst. 2023, 18, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, N.; Wladdimiro, D.; Rosas, E. Self-adaptive processing graph with operator fission for elastic stream processing. J. Syst. Softw. 2017, 127, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.R.; D’Alessandro, E.; Cardellini, V.; Presti, F.L. Towards a Multi-Armed Bandit Approach for Adaptive Load Balancing in Function-as-a-Service Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing and Self-Organizing Systems Companion (ACSOS-C), Aarhus, Denmark, 16–20 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wladdimiro, D.; Arantes, L.; Sens, P.; Hidalgo, N. PA-SPS: A predictive adaptive approach for an elastic stream processing system. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2024, 192, 104940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, M.A.; Rezagholizadeh, M. Textkd-gan: Text generation using knowledge distillation and generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Artificial Intelligence: 32nd Canadian Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Canadian AI 2019, Kingston, ON, Canada, 28–31 May 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Gan, Z.; Fan, K.; Chen, Z.; Henao, R.; Shen, D.; Carin, L. Adversarial feature matching for text generation. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning PMLR, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 4006–4015. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, W.; Narodytska, N.; Patel, A. Relgan: Relational generative adversarial networks for text generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. Seqgan: Sequence generative adversarial nets with policy gradient. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Ren, X.; Lin, J.; Sun, X. Dp-gan: Diversity-promoting generative adversarial network for generating informative and diversified text. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.01345. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27 (NIPS 2014), Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Salimans, T.; Goodfellow, I.; Zaremba, W.; Cheung, V.; Radford, A.; Chen, X. Improved techniques for training gans. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 29 (NIPS 2016), Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; pp. 2234–2242. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, M.H.F.; Akhtar, N.; Ahmad, M.; Naeem, U.; Shafique, M.; Kim, J. A review on metaheuristic-based synthetic data generation methods. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 47514–47533. [Google Scholar]

- Eiben, A.E.; Hinterding, R.; Michalewicz, Z. Parameter setting in evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1999, 3, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.; Razeghi, Y.; Logan, R.L., IV; Wallace, E.; Singh, S. AutoPrompt: Eliciting Knowledge from Language Models with Automatically Generated Prompts. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 4222–4235. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Online, 1–6 August 2021; Volume 1, pp. 4582–4597. [Google Scholar]

- Pryzant, R.; Iter, D.; Li, J.; Lee, Y.T.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M. Automatic prompt optimization with “gradient descent” and beam search. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Ding, Z.; Wei, W. EvoPrompt: Evolving Prompts for Enhanced Zero-Shot Named Entity Recognition with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 19–24 January 2025; pp. 5136–5153. [Google Scholar]

- Saletta, M.; Ferretti, C. Exploring the prompt space of large language models through evolutionary sampling. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 1345–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K.D.; Bui, D.V.; Luong, N.H. Evolving Prompts for Synthetic Image Generation with Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Multimedia Analysis and Pattern Recognition (MAPR), Quy Nhon, Vietnam, 5–6 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.; Ong, Y.S.; Gupta, A.; Bali, K.K.; Chen, C. Prompt Evolution for Generative AI: A Classifier-Guided Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 5–6 June 2023; pp. 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Lu, H.; Gao, T.; Shen, M.; Zhang, W.; Lin, Z.; Cao, L.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Z.; Wen, M.; et al. Plum: Prompt Learning using Metaheuristics. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.08585. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Z.; Hu, M.; Deng, Y.; Cai, S. EvoPrompting: Language Model Based Prompt Tuning for Few-Shot Learning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2024; pp. 301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Dohan, D.; So, D. Evoprompting: Language models for code-level neural architecture search. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 7787–7817. [Google Scholar]

- Sécheresse, X.; Guilbert-Ly, J.Y.; de Torcy, A.V. GAAPO: Genetic Algorithmic Applied to Prompt Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.07157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, C.; Banarse, D.; Michalewski, H.; Osindero, S.; Rocktäschel, T. Promptbreeder: Self-referential self-improvement via prompt evolution. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16797. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Gholami, A.; Gu, B.; Mao, Y.; Ma, X.; Zou, T.; Yu, R.; Lu, X.; Chen, P.; Shi, H.; et al. Evolutionary Computation and Large Language Models: A Survey of Methods, Synergies, and Applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2407.03073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wladdimiro, D.; Arantes, L.; Sens, P.; Hidalgo, N. A multi-metric adaptive stream processing system. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications (NCA), Boston, MA, USA, 23–26 November 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wladdimiro, D.; Pagliari, A.; Brum, R.C. Toward Stream Processing Efficiency Leveraging Cloud Burstable Instances. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering (IC2E), Rennes, France, 23–26 September 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollama. Ollama: Run LLMs Locally. 2024. Available online: https://ollama.com/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. BERTScore: Evaluating Text Generation with BERT. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, A.; Pandey, H.M.; Mehrotra, D. Comparative review of selection techniques in genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Futuristic Trends on Computational ANALYSIS and Knowledge Management (ABLAZE), Greater Noida, India, 25–27 February 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- Razali, N.M.; Geraghty, J. Genetic algorithm performance with different selection strategies in solving TSP. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, Hong Kong, China, 6–8 July 2011; International Association of Engineers: Hong Kong, China, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lamsal, R. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Tweets Dataset, IEEE Dataport. 2020. Available online: https://ieee-dataport.org/open-access/coronavirus-covid-19-tweets-dataset (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Niwattanakul, S.; Singthongchai, J.; Naenudorn, E.; Wanapu, S. Using of Jaccard coefficient for keywords similarity. In Proceedings of the International Multiconference of Engineers and Computer Scientists, Hong Kong, 13–15 March 2013; Volume 1, pp. 380–384. [Google Scholar]

- Tata, S.; Patel, J.M. Estimating the selectivity of tf-idf based cosine similarity predicates. ACM Sigmod Rec. 2007, 36, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).