Featured Application

This study introduces hydraulic safety indices that can be directly applied to evaluate riverfront and floodplain facilities. The indices support identification of high- and low-risk zones in advance, providing a practical tool for facility layout, floodplain management, and maintenance planning. They offer valuable guidance for engineers and planners in sustainable river development.

Abstract

Climate change has intensified torrential rainfall and floods, causing frequent floodplain inundation with erosion and deposition. Large-scale waterfront facilities such as park golf courses are highly vulnerable, requiring systematic hydraulic safety evaluation. We simulated a recent flood in the Musim Stream using a two-dimensional FaSTMECH model to assess floodplain safety. The model showed excellent reproducibility (RMSE = 0.0176 m, NSE = 0.95 for depth; RMSE = 0.016 m/s, NSE = 0.87 for velocity). Flood risk indices—flood intensity (FI) and flood hazard rating (FHR)—and erosion–deposition indices—transient erosion and deposition index (TEDI) and steady erosion and deposition index (SEDI)—were applied. FI values were in the range of 0.3–6.4 (median 2.8) and FHR was in the range 0.7–10.2 (median 3.0), indicating that most floodplain areas exceeded the “high” to “extreme” risk range. TEDI was in the range of 0.004–4.15 (mean = 0.60), while SEDI was in the range of 0.001–5.59 (mean = 2.12). High TEDI values (0.6–0.9) occurred in curved and contracted sections, corresponding to observed erosion zones, whereas high SEDI values (0.8–1.0) were concentrated in the main channel. These results demonstrate that the indices effectively quantify and visualize floodplain risk, providing a practical basis for the design, placement, and maintenance of floodplain facilities.

1. Introduction

A natural river consists of a main channel, where water flows during low-water and non-flood seasons, and floodplains that are inundated from the main channel due to the rise in water level in the event of a flood [1]. Floodplains are typically available during non-flood seasons, enabling the utilization of waterfront areas. In Korea, large-river restoration projects in the late 2000s promoted waterfront space creation projects, resulting in the creation of various structures near rivers, including sports facilities, walking trails, ecological parks, and park golf courses [2,3].

These waterfront facilities have contributed to the leisure activities of urban residents, thereby improving the quality of life, while playing crucial roles in improving ecological connectivity and landscape values in urban areas [4,5]. Particularly, structures that highly utilize space and are close to riverbeds, such as park golf courses, can be seen as representative cases where rivers and human activities coexist at their point of contact. However, such facilities are affected by river flow during the flood season and can face problems, such as structural damage and soil deposition, in the event of disasters if installed without proper hydraulic assessment [6]. In Korea, it is necessary to conduct safety assessments that consider the diverse installation types of waterfront facilities within floodplains. However, outside Korea, studies specifically addressing the evaluation of floodplains with installed waterfront facilities are relatively scarce.

Climate change has increased rainfall intensity, flood frequency, and flood discharge. Sudden increases in flow rates caused by typhoon-induced torrential rainfall in summer have flooded and damaged waterfront facilities installed in floodplains [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. These floods raise flood levels, accelerate erosion and deposition in floodplains and riverbeds, and lead to flood damage, such as instability of structural foundations and functional degradation caused by the movement and deposition of soil [14]. In response, the United States has managed flood damage using the flood risk maps prepared by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for major river systems under the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) [15]. Japan has also performed flood risk predictions and inundation simulations using hydraulic models and systematically produced flood risk maps, including flood depth information, led by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism and the River Disaster Prevention Center [16]. In addition, various hydraulic models have been applied to analyze flood risk, erosion, and inundation characteristics in river and floodplain environments. Representative examples include HEC-RAS, which has been used for 1D–2D coupled simulations to model floodplain inundation characteristics [5], and InfoWorks ICM, which has been applied to analyze inundation patterns and flooding characteristics on river terraces [6]. Nays2D has been employed for unsteady two-dimensional flow analysis to evaluate flow characteristics within floodplains [7], while FaSTMECH has been utilized for two-dimensional flow analysis including floodplain benches to assess inundation and flow velocity characteristics [14]. These approaches play important roles in identifying and managing risk sections in advance based on the inundation characteristics of floodplains and adjacent areas [6].

In general, the erosion and deposition of a riverbed are caused by changes in flow velocity [17,18]. The increased flow velocity during high-flow-rate events accelerates the dislocation of riverbed materials and the suspension of particles by increasing shear stress, thereby causing erosion. Subsequently, when the water level and flow velocity decrease, the shear stress drops below the particle resuspension limit, causing the suspended particles to settle and form deposition [19,20]. These erosion and deposition processes alter the terrain and riverbed characteristics around structures, leading to the functional degradation over the long term, thereby reducing the structural stability of waterfront facilities [21]. To predict and quantitatively evaluate damage to floodplains and waterfront facilities during such flood events, hydraulic impact analysis is required, including flow analysis in compound sections that include floodplains [14]. Since flow patterns in floodplains are significantly different from the flow of the main stream due to the lower water depth and higher resistance to flow, 2D numerical analysis is advantageous [22]. Accordingly, International River Interface Cooperative-Flow and Sediment Transport with Morphological Evolution of Channels (iRIC-FaSTMECH), a dynamic-based model, was developed to perform numerical simulations for flood events. The iRIC model framework uses the finite difference method on a curved grid, upgraded from a multi-dimensional surface water surface modeling system [23,24], that solves the depth and Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations [25]. iRIC-FaSTMECH can provide the maximum flooded area at the peak level and simulate floodwater levels and flow velocity distributions [26,27,28]. Flow velocities and water depths in past flood events have been utilized as factors to evaluate the hydraulic safety of small rivers, incorporating the Einstein–Shields equation for evaluating erosion and deposition [29].

In this study, we aimed to assess the applicability of erosion and deposition indices, which serve as relative indicators to identify the potential and spatial tendency of erosion and deposition rather than quantifying their magnitude, in small urban rivers with various types of waterfront facilities. We simulated non-flood seasons and a flood event for small river floodplains in Korea using FaSTMECH, a two-dimensional unsteady flow analysis model capable of simulating drying and wetting. Based on the water depth and flow velocity derived through this model, Shields-based erosion and deposition indices were applied. In addition, flood risk indices previously employed in levee-protected areas were also evaluated to examine the potential risk to waterfront facilities during flood events, including the likelihood of structural instability and local erosion or deposition. Through this comprehensive approach, we aimed to enhance the understanding of hydraulic safety and maintenance planning for floodplain facilities. The results of this study can be utilized as valuable data in determining the appropriateness of risk area selection and construction layout for all waterfront facilities because they consider the hydraulic stability of structures and the impacts on waterfront environments. They can also serve as essential reference data for establishing long-term river maintenance and disaster prevention plans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. FaSTMECH Model

FaSTMECH is a 2D flow analysis model installed in iRIC, jointly developed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and Japan’s Hokkaido River Disaster Prevention Center (RIC). It can analyze unsteady flow and the simulation of drying and wetting. The governing equations for the s, n, and z directions of the modular curvilinear coordinate system that integrates sediment transport and riverbed fluctuations are given in Equations (1)–(4) [30].

where , , and are the components in the downstream, transverse, and vertical directions, respectively, E is the water surface height, and R is the radius of curvature of the channel centerline. 1 − N = 1 − /R [31] is the downstream distance represented in the curvilinear coordinate system. , , , , , and are expressed in Equation (5) of the deviatoric stress tensors. Viscous stress in natural rivers is generally insignificant and can be negligible compared to Reynolds stress [25].

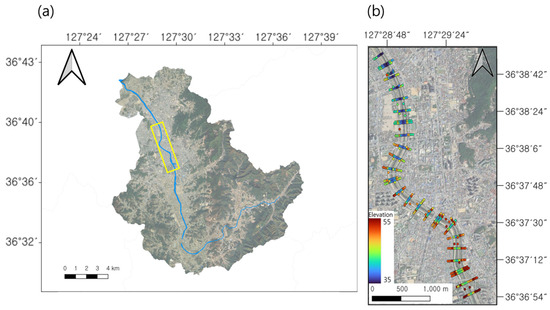

To evaluate the hydraulic safety of floodplains and waterfront facilities under high-flow-rate conditions in the event of a flood, a numerical simulation was performed for the actual basin selected for FaSTMECH analysis. Measurements of water level changes were compared to evaluate the applicability of the FaSTMECH model. The Musim Stream was the target of this study. It is a tributary of the Geum River that flows through the central region of the Korean Peninsula. It originates from the Meogumi hill in Cheongju City, Chungcheongbuk-do, passes through the city, and flows into the Miho River [32]. Its upstream area is the rural area of Cheongwon-gun, while its downstream area is an urban area where the Chungcheongbuk-do Office is located. The Musim Stream basin has a drainage area of 192.67 km2, with a design flood discharge of 1355 m3/s and a design flood level of 5.99 m corresponding to a 100-year return period. In 2024, the average discharge was 4.12 m3/s, and the average water level was 0.85 m. To evaluate the hydraulic safety of floodplains and waterfront facilities in the Musim Stream, a section from the Yongpyeong Bridge water level monitoring network point in the urban area to the Heungdeok Bridge water level monitoring network point was set as the simulation section (Figure 1a). In the section, various waterfront facilities and structures are located, including sports parks, flower gardens, and ground parking lots. To construct the topography of the model, ground elevations were acquired and expressed using RTK-GPS through a field survey on 10 July 2025, in addition to topographic survey points and ground elevations from the 2019 River Master Plan Report for the simulation section (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Target section: (a) target basin and points; (b) topographic data collection results.

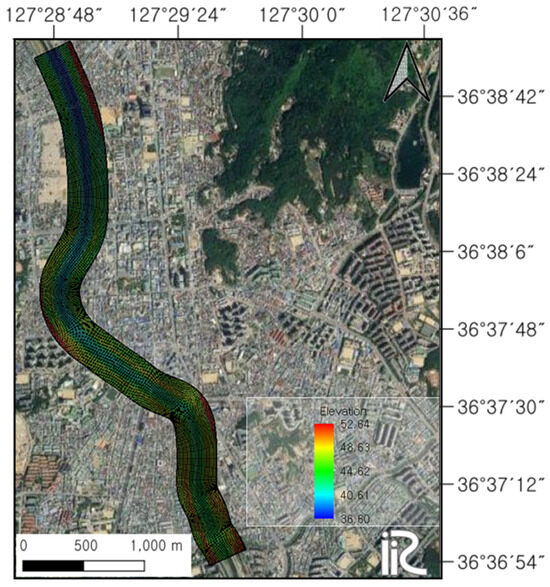

Topographic data were constructed for an approximately 5 km section. Since FaSTMECH performs simulations using only a structured rectangular mesh, the computational grid consisted of 18,537 elements, with grid spacings of approximately 9 m in the longitudinal (I) direction and 8.3 m in the lateral (J) direction (Figure 2). Figure 2 illustrates the bed elevation within the computational grid. Unlike unstructured triangular meshes, the rectangular mesh enhances numerical stability and computational efficiency under quasi-steady-flow conditions and facilitates alignment with the channel geometry. In addition, the use of orthogonal coordinates simplifies the calculation of momentum and turbulence terms, thereby improving model convergence and analytical consistency.

Figure 2.

Computational grid and bed elevation distribution used for the FaSTMECH (Flow and Sediment Transport with Morphological Evolution of Channels) simulation.

The numerical simulation periods of the model were in 2025, from 00:00 on 10 July to 00:00 on 11 July (case 1) and from 00:00 on 15 July to 12:00 on 18 July (case 2). In Case 1, the simulated upstream daily discharge was 2.6 m3/s, representing a low-flow condition used for model calibration and verification. Case 2, corresponding to an extreme flood condition applied for the hydraulic safety evaluation, showed a maximum daily discharge of 178.7 m3/s at the simulated upstream section on 17 July 2025. For both cases, the upstream and downstream boundary conditions were defined using the water level and flow rate data provided by the Geum River Flood Control Center. Specifically, the flow rate at the Yongpyeong Bridge was used as the upstream boundary condition, and the water level at the Heungdeok Bridge was applied as the downstream boundary condition to ensure stable model convergence during the simulations. During the calibration process, the Manning’s roughness coefficients (n) were set to 0.030 for the main channel and 0.040 for the floodplain. In case 1, for the calibration and verification of the model, the water depth and flow velocity at the central point of each measurement line were measured using ADV (FlowTracker 2) through on-site monitoring on 10 July 2025. The field measurements were conducted using the wading method, targeting representative hydraulic sections such as straight segments and areas immediately before, at, and after the meander apex. Although the wading survey limited the spatial resolution of the data and number of verification points, the selected sections were considered appropriate to represent the flow variability within the meandering reach. Using these measurements for model verification, the simulation results appropriately reproduced the observed hydraulic conditions. In case 2, approximately 316.5 mm of precipitation occurred. As the hourly rainfall reached 63.8 mm, the water level increased from 0.60 m (normal season) to 3.77 m. The design flood level of the Musim Stream was 5.99 m. An attempt was made to apply this event to the hydraulic safety evaluation indices to assess the safety of floodplains and waterfront facilities under high-flow conditions.

2.2. Floodplain Safety Evaluation Indices and Validation

Floodplain stability was first assessed using two flood risk indices (FRIs): Flood Intensity (FI) and Flood Hazard Rating (FHR). FI, proposed by Beffa [33], is calculated through the water depth when the flow velocity is less than 1 m/s. This is because the damage caused by flooding is more significant compared to other factors in this case. If the flow velocity is 1 m/s or higher, FI is calculated using the product of the flow velocity and water depth. FHR, proposed by Wallingford [34], is calculated using Equation (6). For FI, limited damage can be determined for a value between 0.0 and 0.5, intermediate damage (can be dangerous) for a value between 0.5 and 2.0, and high damage (dangerous) for a value of 2.0 or higher [33]. In the case of FHR, low risk (caution) can be determined for a value between 0.00 and 0.75, normal (dangerous in some cases) for a value between 0.75 and 1.23, high risk (dangerous in most cases) for a value between 1.25 and 2.00, and extremely high risk (dangerous to everyone) for a value of 2.00 or higher [34].

In addition, for hydraulic safety evaluation, considering erosion and deposition, the Einstein–Krone formula (1962) was used, calculated using Equation (7), to apply the Transient Erosion and Deposition Index (TEDI) developed by Song et al. [29].

where D is the deposition flux [kg/m2/s], ω is the settling velocity of a single particle in tranquil water [m/s], is the probability for settling particles to remain deposited, is the near-bed volumetric sediment concentration [kg/m3], is the local bed shear [N/m2], and is the critical shear stress for deposition [N/m2]

Since , ω, and are generally used as constants for modeling, the factor changed by the model is the local bed shear, which is the shear stress by water. Accordingly, the terms except for were assumed to be constants. In the Einstein–Krone formula, deposition is highly likely to occur when is higher than , and erosion is highly likely to occur when is lower than .

can be calculated using Equation (8) [35]. was assumed to be a constant, as it is the density of water containing sediment. As and V2 are functions of time, they were expressed through a time derivative of as shown in Equation (9).

where is the sediment particle density [kg/m3]; is the friction factor; and is the cross-sectional averaged velocity [m/s].

In Equation (9), the change rate of the friction factor over time is negligible [36]. Therefore, it is expressed as Equation (10) by setting ()/ = 0.

Therefore, differentiating the Einstein–Krone formula with respect to time can yield Equation (11). At a point where is minimal, the deposition rate may reach its peak.

According to the above equation, the change rate of the deposition flux over time is proportional to the flow velocity and acceleration. Va was defined as TEDI [29].

The Steady Erosion and Deposition Index (SEDI) used , which determines the movement of particles on the riverbed. To average a flood wave and predict relative deposition while the flood wave begins and ends in a specific section of a river, Equation (12), which is applied in steady-uniform flow, was used. in an open channel can be expressed as γRS, and it can be expressed as Equation (13) under the assumption of R≈h in a wide river [29].

This equation can be expressed as Equation (13) when the Manning formula is substituted for . It can be seen that is a function of and .

can be obtained using the Shields diagram as shown in Equation (14). Substituting obtained from Equation (13) and obtained from Equation (11) into can yield Equation (15).

A function related to particles was assumed to be a constant, as shown in Equation (15), and was defined as SEDI [29]. TEDI and SEDI cannot present quantitative amounts of erosion and deposition but are expected to predict sections with erosion and deposition that occur in flood channels and result in damage at specific research target points.

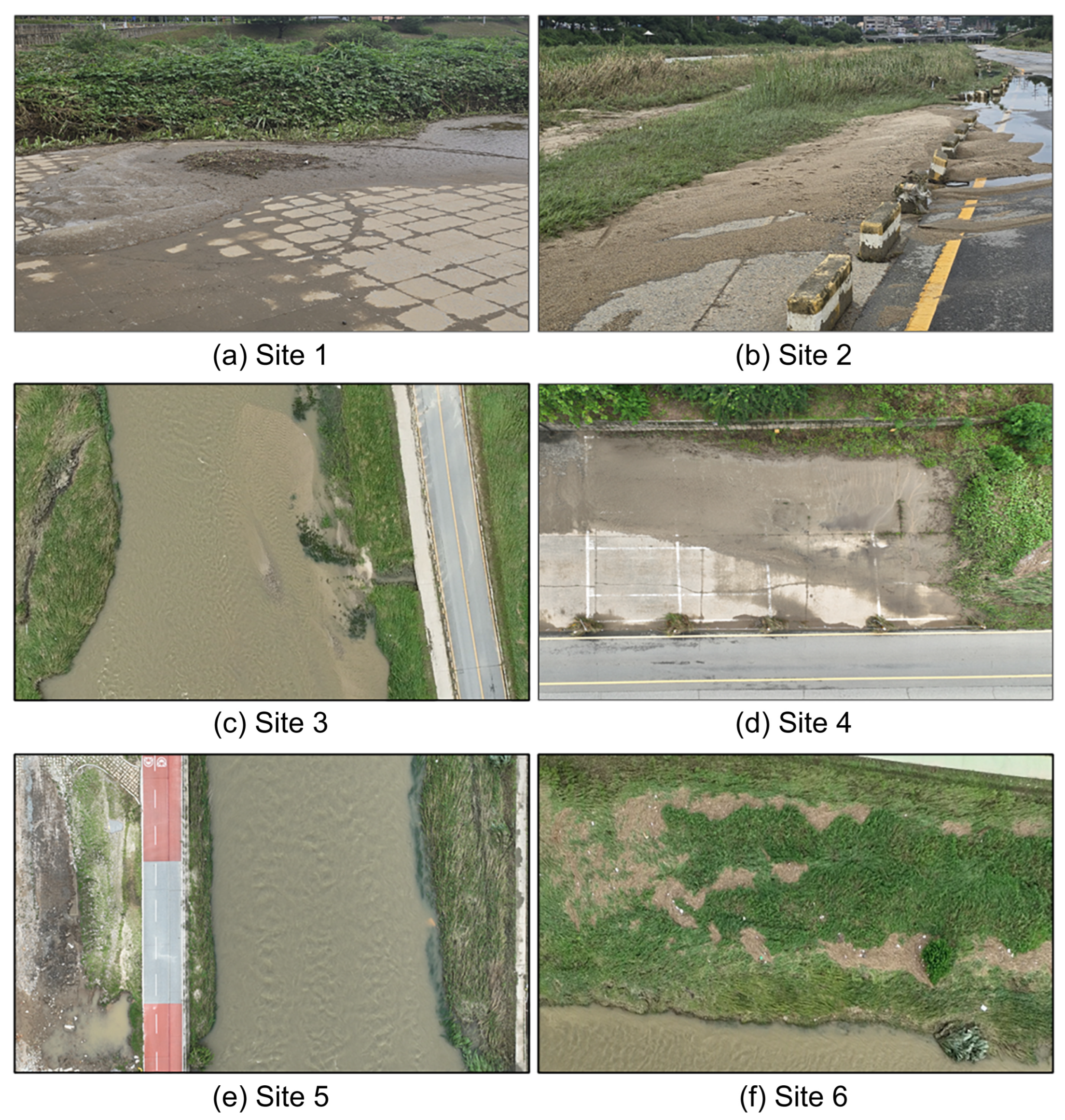

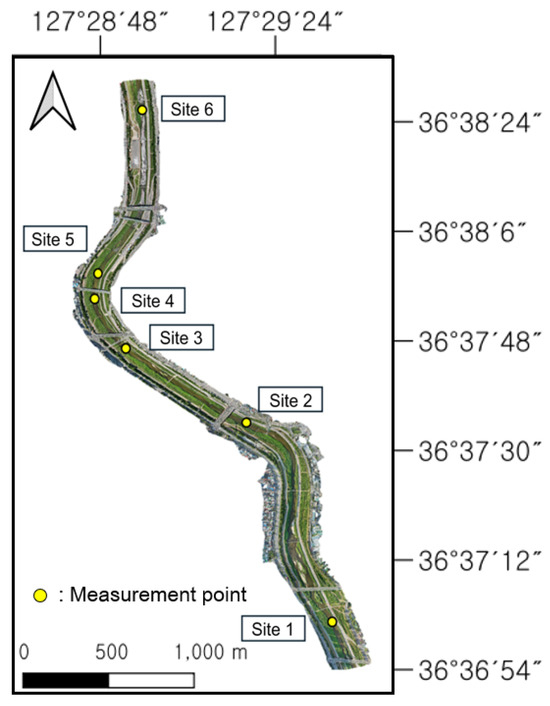

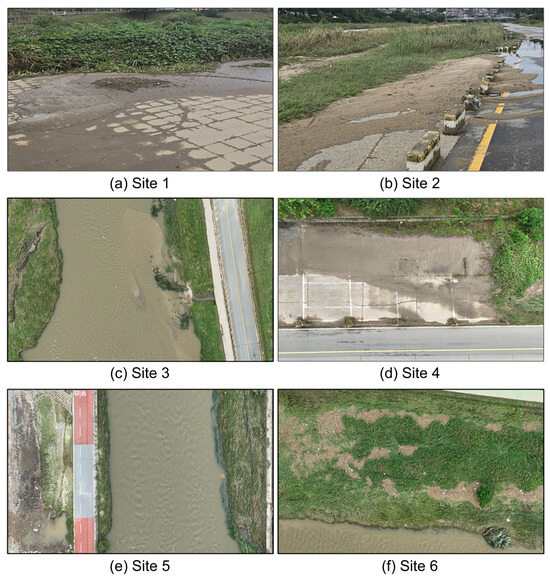

For the verification of the model and indices, on-site monitoring was performed on 10 and 18 July 2025. First, for the verification of the model, the flow velocity and water depth were measured at key points in the river on 10 July before flood occurrence and they were compared with the model results. Measurements were performed at six points using FlowTracker 2 as a measurement sensor. In addition, a drone was used to obtain optical images of the simulation points. The images were matched to create an SFM and represent the current status. In the case of 18 July, the status of points with erosion and deposition was monitored after the occurrence of the flood (Figure 3). This was utilized to examine the applicability of the indices based on the field conditions for areas with concerns over erosion and deposition according to the index application results.

Figure 3.

Field data acquisition points in the Musim Stream.

3. Results

3.1. FaSTMECH Numerical Simulation

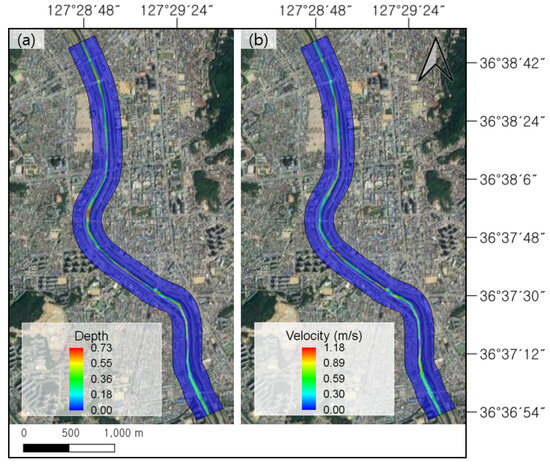

To verify the results of the FaSTMECH model in the Musim Stream watershed, a numerical simulation was performed using flood control center measurement data through case 1. The overall tendencies of the water depth and flow velocity for the simulation results are shown in Figure 4. As a maximum water depth of 0.73 m was observed from Figure 4a and a maximum flow velocity of 1.18 m/s from Figure 4b, it was judged that the flow velocity was partially overestimated compared to the water depth. Flow velocity increase/decrease points and water level ascent/descent sections due to curvature, however, were found to be appropriate.

Figure 4.

FaSTMECH simulation results on 10 July: (a) water depth; (b) flow velocity.

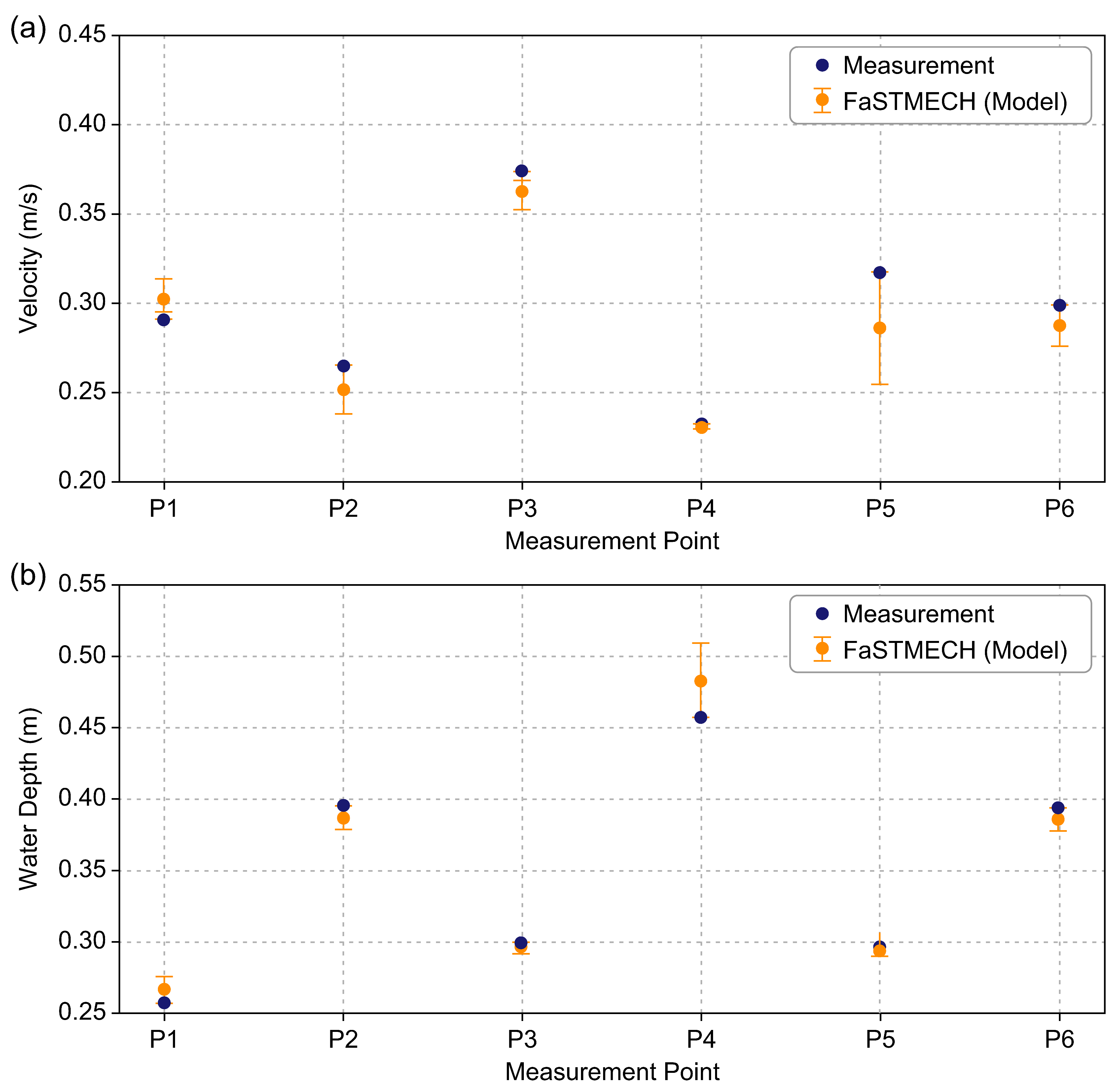

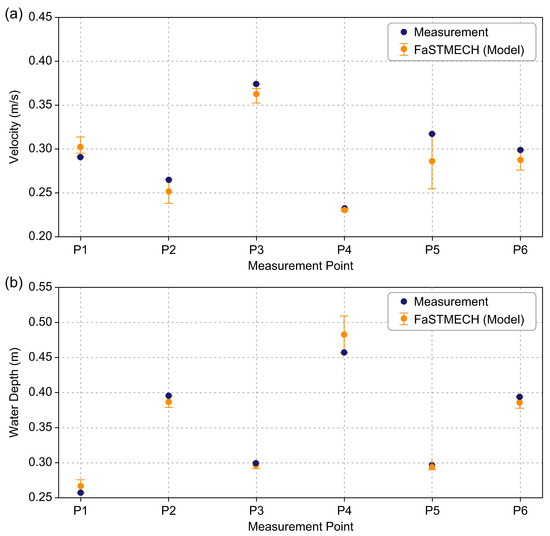

To verify the model results, on-site measurements for the water depth and flow velocity were performed at key points on 10 July for comparison (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of measurement and simulation results at measurement points.

Six measurement points before, in the middle of, and after the curvature were selected. The measurement and simulation results at the same points were compared for the flow velocity and water depth. For performance evaluation, the root mean square error (RMSE), the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), the Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient (NSE), and the coefficient of determination (R2) were used (Figure 5). Figure 5a shows the verification results for the water depth. RMSE was 0.0176 m, MAPE was 4.28%, and NSE and R2 values were 0.9458, respectively. This means that the model reproduced the measured water depth very accurately at all points, with high consistency and reliability. Figure 5b shows the evaluation results for the flow velocity. RMSE was 0.0160 m/s, MAPE was 4.36%, and NSE and R2 were 0.8681, respectively, showing high consistency with the measurements. Somewhat low accuracy was observed compared to the water depth results, but it is still considered excellent from the viewpoint of hydraulic model performance evaluation. Therefore, the application of the hydraulic safety evaluation indices that utilize the flow velocity and water depth will be appropriate.

Figure 5.

Comparison of FaSTMECH simulation results by measurement point: (a) flow velocity; (b) water depth.

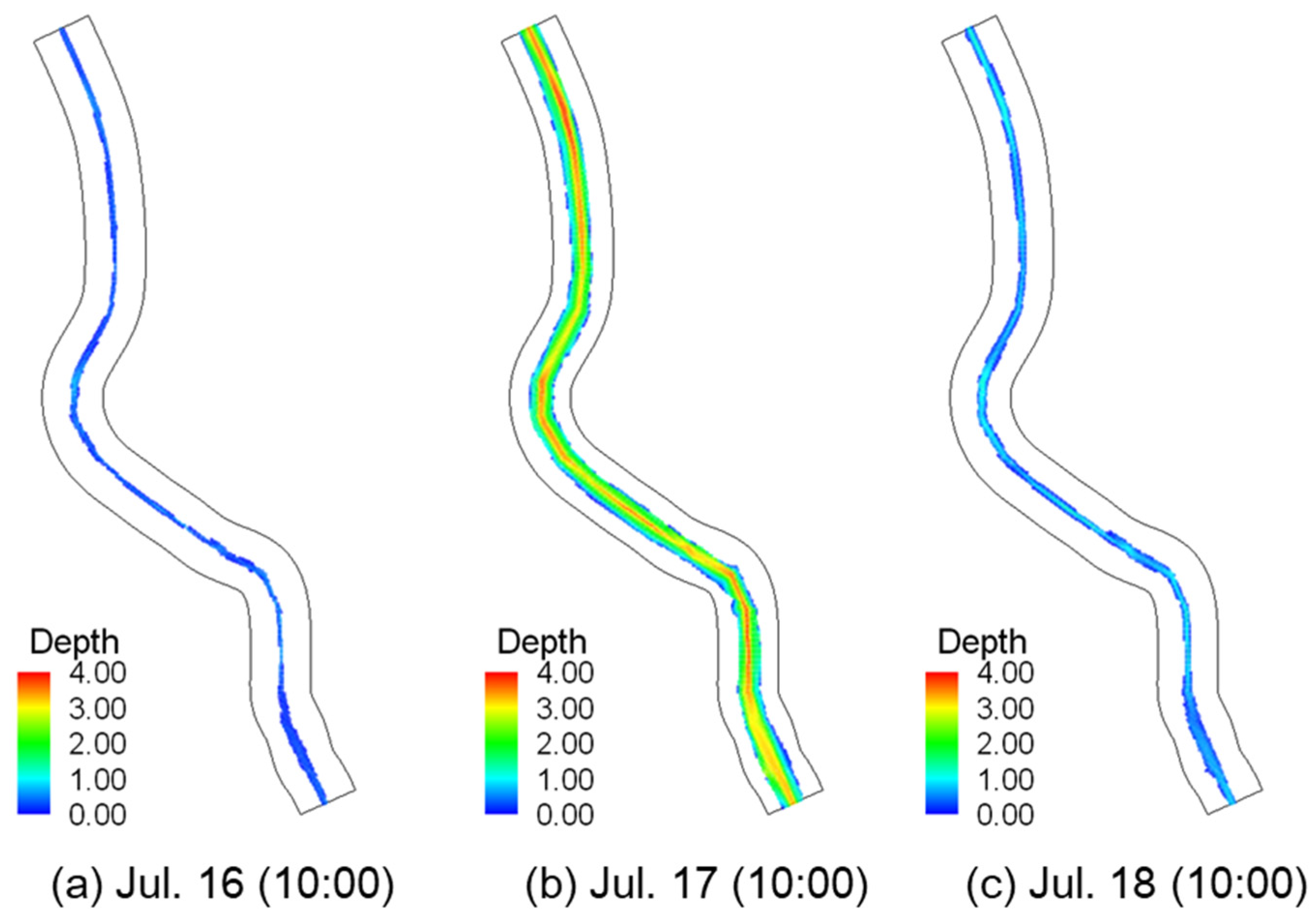

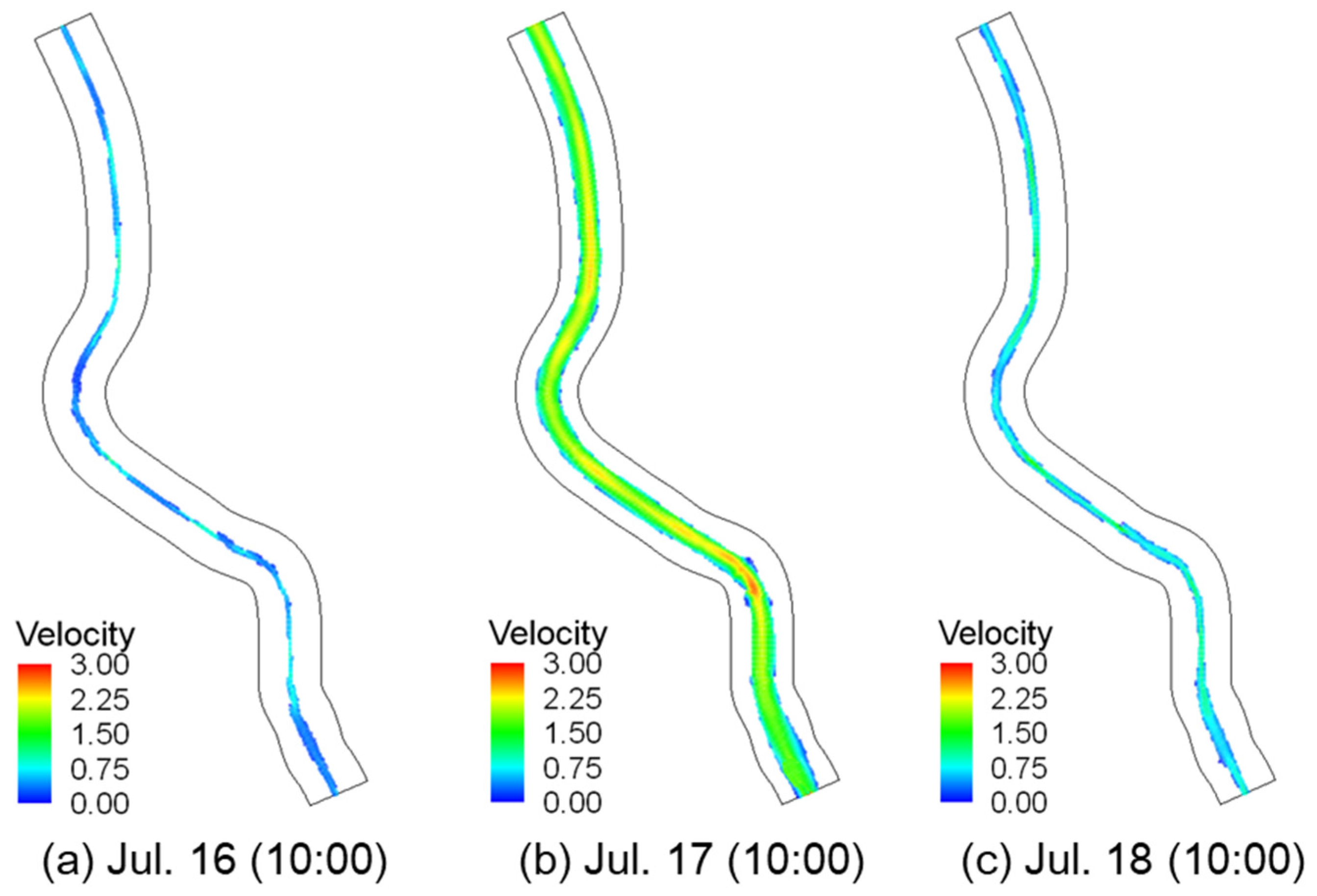

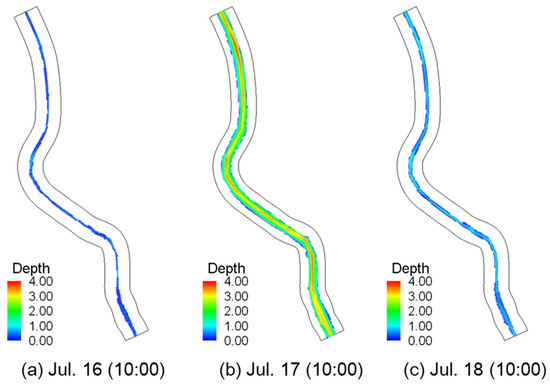

The verified model exhibited simulation results for the water depth and depth-averaged flow velocity during the period between 16 and 18 July 2025, when the flood event occurred, with contours shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the contour results for the water depth and depth-averaged flow velocity at each time point. Figure 6a shows the results before flood occurrence. Overall, low and stable water depths can be seen. Figure 6b shows that the entire floodplain was inundated during the flood peak, and Figure 6c exhibits the return to the original conditions after the flood event. These findings indicate that the model well reproduced the water depth for the main channel and floodplains. Figure 7 shows the flow velocity conditions under the same conditions as Figure 6. As with the water depth, the flow velocity distributions before, in the middle of, and after flood occurrence were appropriately reproduced.

Figure 6.

FaSTMECH water depth results: (a) 16 July (10:00); (b) 17 July (10:00); (c) 18 July (10:00).

Figure 7.

FaSTMECH flow velocity results: (a) 16 July (10:00); (b) 17 July (10:00); (c) 18 July (10:00).

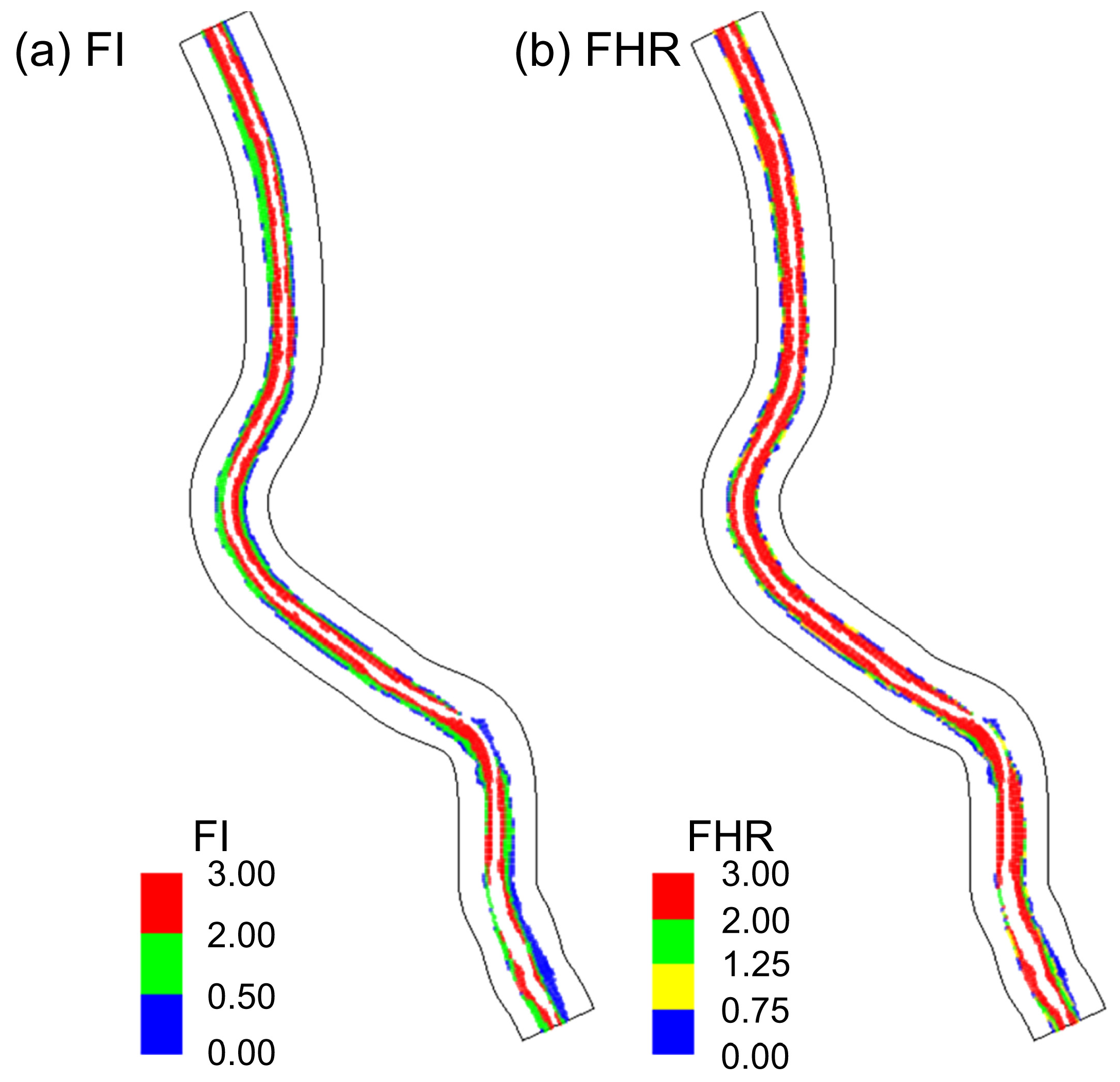

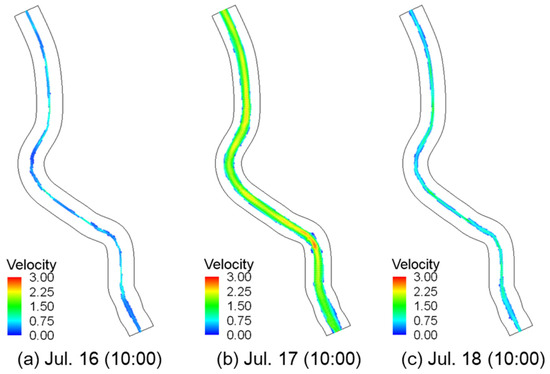

3.2. FRIs

The FRIs were applied to the Musim Stream watershed where floodplains and waterfront facilities were located. Although originally developed as safety evaluation indices for damage to inland buildings and people, they have been applied as floodplain safety evaluation indices [37]. To evaluate the hydraulic safety of waterfront facilities in the Musim Stream watershed in the event of a flood, FI, proposed by Beffa [33], and FHR, proposed by Wallingford [34], were applied based on the flow velocity and water depth modeling results on 17 July 2025, when a flood event occurred. Figure 8a,b show the results of applying FI and FHR, respectively, in contour form. As the indices were significantly affected by the water depth, the main channel section exhibited an extremely dangerous level. Therefore, the main channel section was excluded to evaluate the safety of the waterfront space.

Figure 8.

FRI application results: (a) Flood Intensity (FI); (b) Flood Hazard Rating (FHR).

The results of applying both indices showed similar patterns. FI exhibited relatively large areas with low damage in floodplains, while FHR generally showed extreme risks except for some low-risk and high-risk areas. FI was calculated as the product of the flow velocity and water depth because the flow velocity mostly exceeded 1 m/s during the flood event. FHR was also calculated as the product of flow velocity +0.5 and the water depth, which led to a higher risk index despite similar patterns.

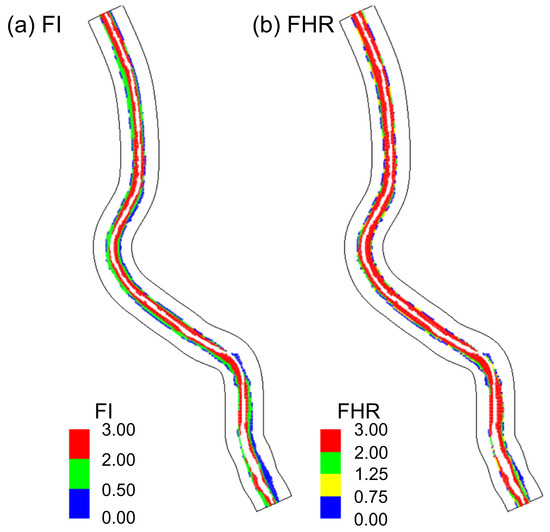

3.3. Application of Erosion/Deposition Indices (TEDI, SEDI)

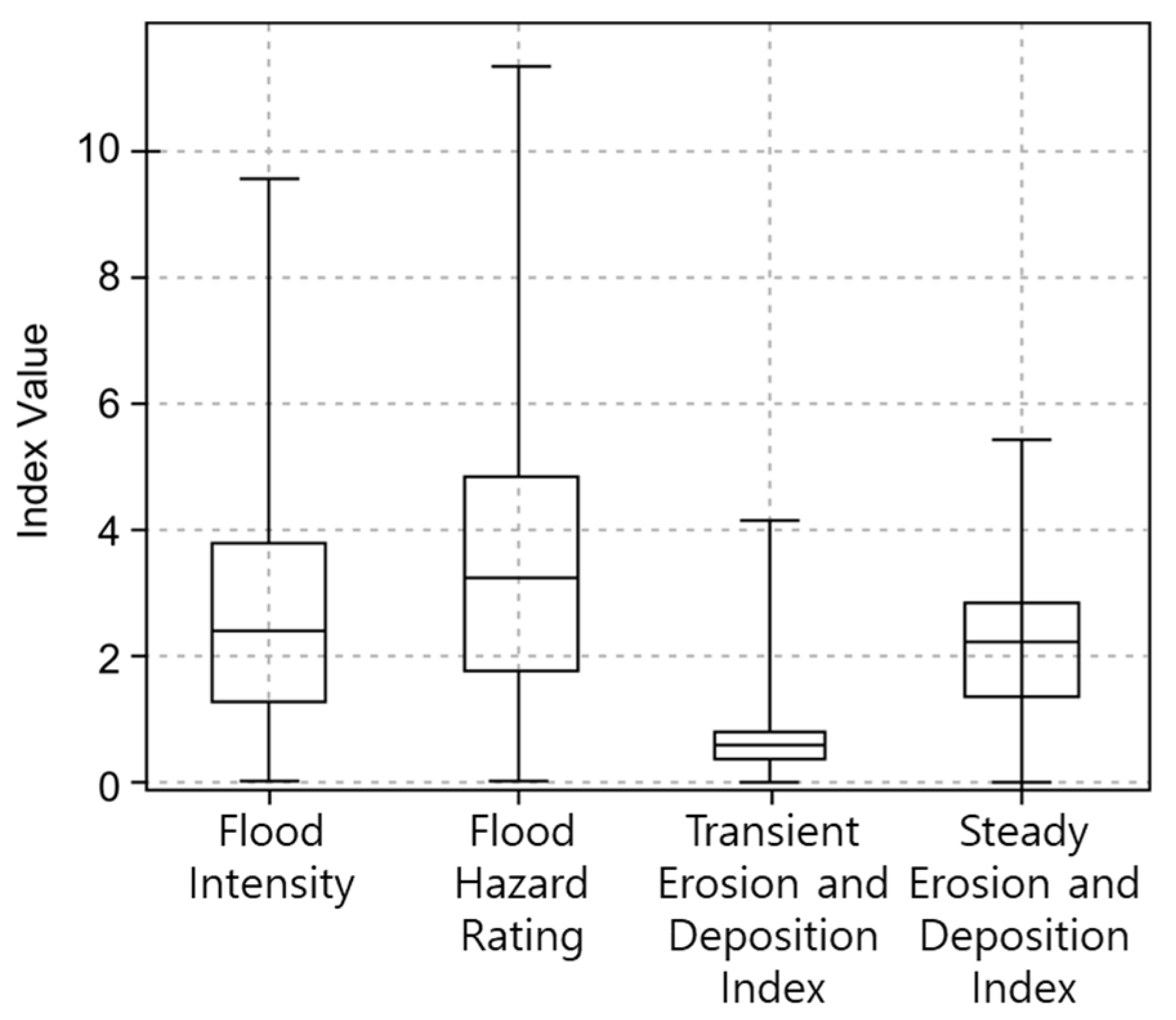

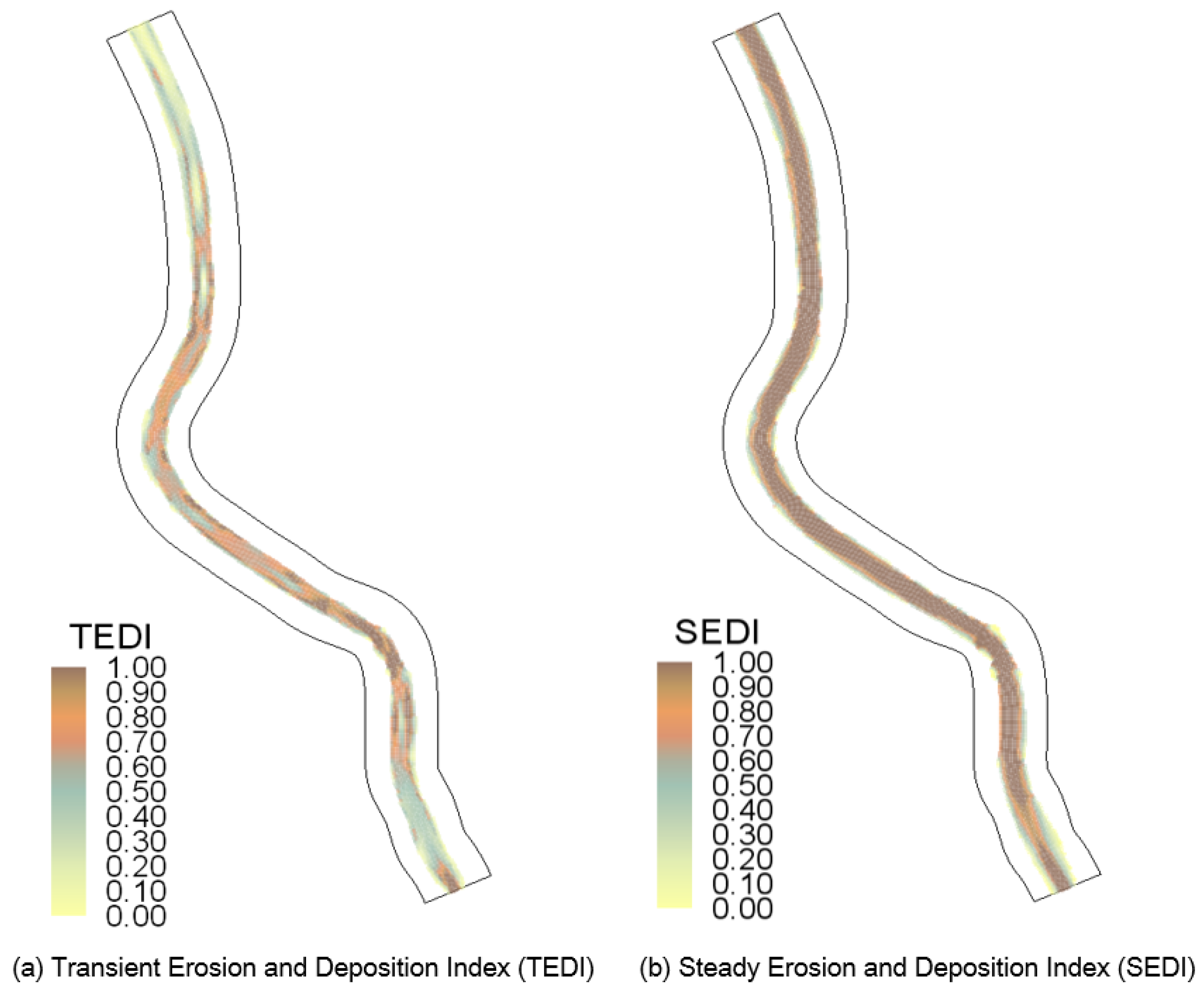

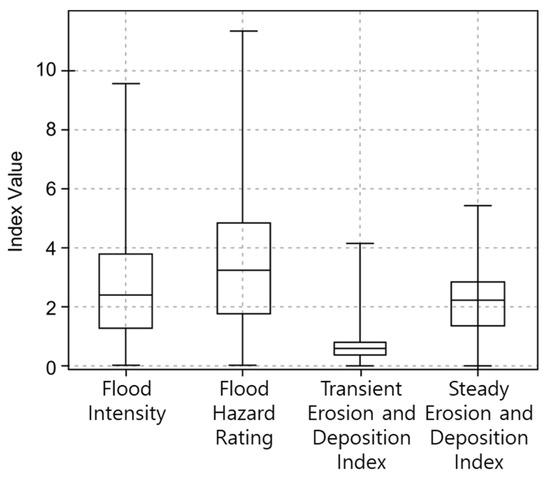

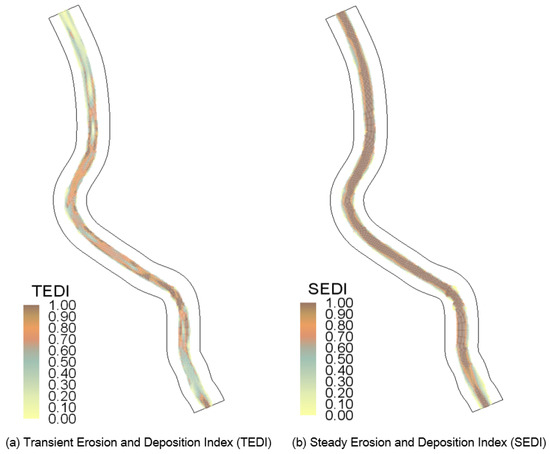

Figure 9 shows the results of calculating TEDI and SEDI for the occurrence of an extreme rainfall event on 16 July. As the generalization process was required for the comparison between the two indices calculated, the percentiles, as well as maximum, minimum, and mean values of the two indices in the Musim Stream, were calculated (Table 2). The spatial distributions of TEDI and SEDI were normalized to a range between 0 and 1 (Figure 10). Each computed value was divided by the mean of its respective index within the simulation domain. Although most values fall within this range, some may exceed 1 in high-risk areas. This normalization was applied to avoid underestimating erosion-prone zones during extreme floods and enable relative spatial comparisons of erosion and deposition intensity.

Figure 9.

Box and whisker plot by index.

Table 2.

Percentiles and statistical values of estimates obtained for the transient and steady erosion and deposition indices of the Musim Stream.

Figure 10.

Erosion/deposition evaluation index application results: (a) Transient Erosion and Deposition Index (TEDI); (b) Steady Erosion and Deposition Index (SEDI).

For both indices, the risk of erosion increases as the value of the index increases, and the occurrence of deposition is expected as it decreases. TEDI (Figure 10a) was calculated using the flow velocity acceleration term (Va), and the time interval dt was set to one hour due to the nature of the hydraulic simulation results used in this study. This allows TEDI to show the tendency of flow velocity changes on a large time scale according to the input/output data and results, rather than reflecting instantaneous acceleration changes in detail.

In the results, TEDI values were relatively high (0.6–0.9) in curved and highly curved sections. By contrast, they were low (below 0.2) in straight sections with mild flow changes. TEDI is particularly sensitive to local acceleration variations under unsteady flow conditions. Therefore, it effectively identifies sections where velocity rapidly increases due to rainfall inflow. SEDI (Figure 10b) was calculated in the form of SEDI = V2/h(1/3) to reflect erosion and deposition effects under average flow conditions. Its value was generally high. This indicates the significant influence of the increased flow rate, as the target was the urban stream of the second tributary with floodplains. Particularly high values (0.8 to 1.0) were continuously distributed in the main channel. In particular, due to the nature of a meandering channel, relatively high flow velocity led to high index values on the inside before meanders and on the outside after meanders. This presents the possibility of erosion in main channel sections and high flow velocity sections, as well as deposition in floodplain sections.

Index distribution is presented for FI, FHR, TEDI, and SEDI through box plots. For both FI and FHR, the range of values was widely distributed. Overall, high values corresponding to the highest risk levels were observed. In particular, FHR exhibited higher values. Its median value was approximately 3, and its maximum value exceeded 10, indicating that it reflects more severe risk levels than FI. In the case of TEDI, the overall distribution covered both erosion and deposition. SEDI, with a median value of approximately 2, exhibited generally higher values than TEDI. This implies that the risk of erosion is high inside the Musim Stream.

The comparison of applying TEDI, SEDI, FI, and FHR (Figure 8 and Figure 10) showed that the erosion occurrence sections of TEDI were similar to the dangerous sections, expected deposition sections, and low-risk sections of FI. Since TEDI is calculated through changes in flow velocity over time, it was generally similar before and after curvature and in straight sections, excluding some low index values in the main channel section. SEDI exhibited results similar to FHR, with the main channel and floodplain sections consistently found to be erosion-prone areas.

When Figure 11 was compared with the index application results in Figure 10, the impact of applying flow velocity and water depth results on erosion was biased towards the main channel for SEDI, thereby slightly reducing its applicability. For TEDI, the index was apparently calculated similarly to on-site erosion and deposition results, as it uses a calculation method that considers temporal changes in flow velocity. For SEDI, the effect of applying flow velocity and water depth results on erosion was biased towards the main channel, and the results were not consistently aligned with the on-site monitoring results. As monitoring was performed immediately after the flood event, there were limitations in accurately monitoring erosion compared to deposition due to the recovery process of the flow rate and water level. As with previous opinions on TEDI and SEDI [29], sections for erosion and deposition can be managed by predicting them.

Figure 11.

Erosion/deposition occurrence points: (a) Site 1; (b) Site 2; (c) Site 3; (d) Site 4; (e) Site 5; (f) Site 6.

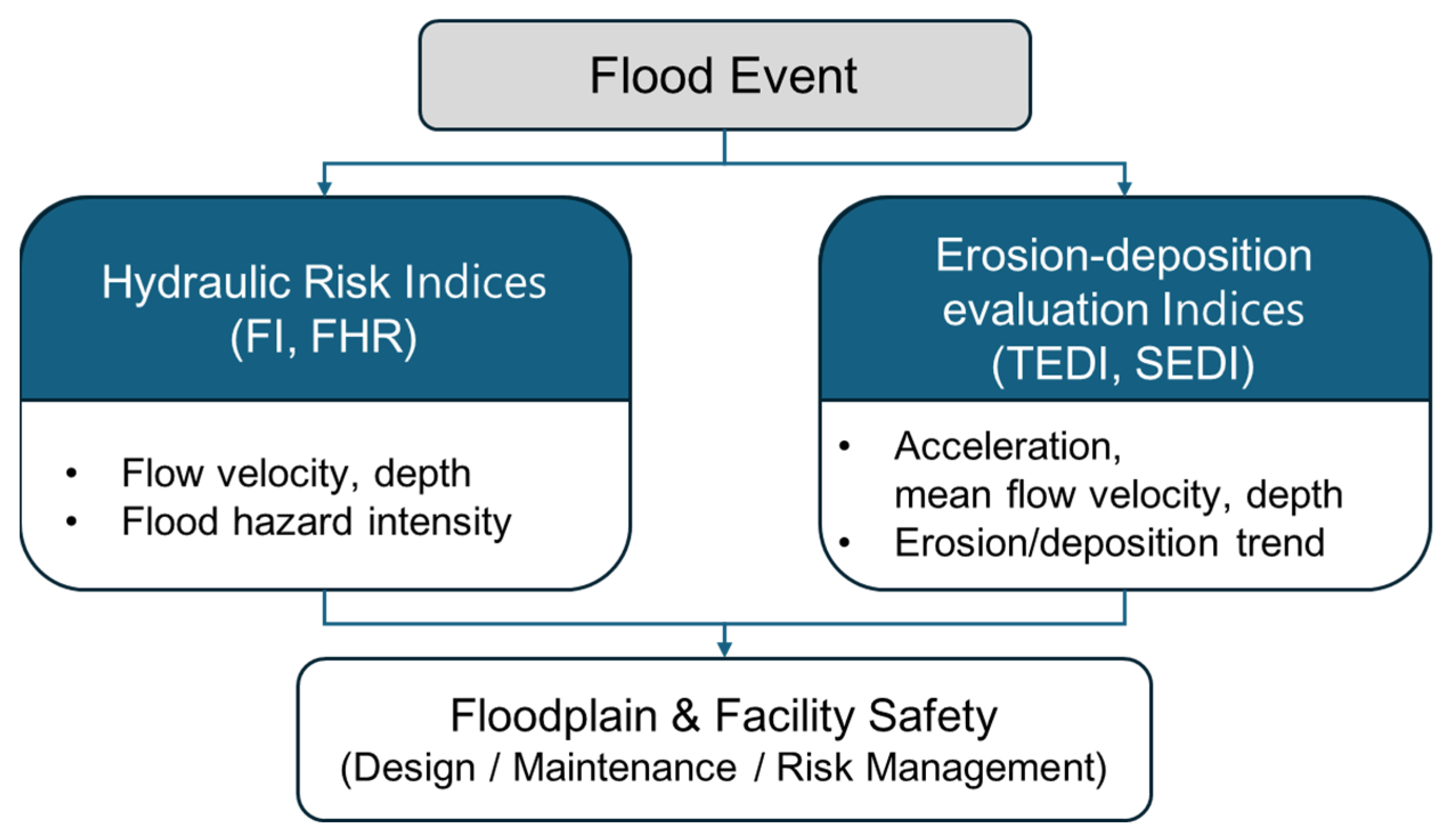

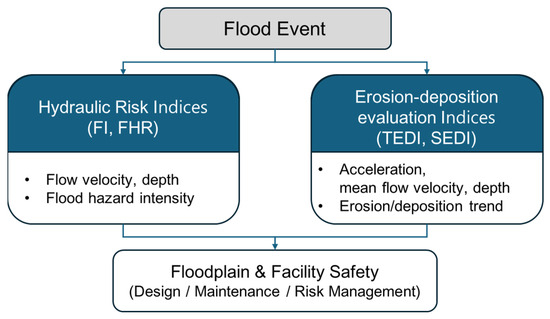

Thus, both the flood hazard indices (FI, FHR) and the erosion–deposition indices (TEDI, SEDI) were calculated using similar hydraulic parameters such as flow velocity and water depth. Each index serves a distinct purpose: the flood hazard indices quantify the hydraulic risks of the channel, whereas the erosion–deposition indices evaluate the potential for erosion and deposition during flood events. By assessing and linking the applicability of these indices across different hydraulic environments, we demonstrate their potential for use in the design and maintenance of waterfront facilities within floodplains. If the measurement of tractive force can be utilized as a factor in the indices, the indices are expected to be applicable in terms of facility installation and maintenance by inferring quantitative amounts of erosion and deposition (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Conceptual diagram illustrating the relationship between hydraulic risk indices (FI, FHR) and erosion–deposition evaluation indices (TEDI, SEDI) for floodplain safety assessment.

4. Discussion

This study quantitatively evaluated hydraulic risks in floodplains and waterfront facilities. The analysis focused on increased rainfall intensity and more frequent floods caused by climate change. The goal was to provide basic data for planning the installation and maintenance of hydraulic structures. To achieve this, both non-flood and extreme flood conditions were simulated using FaSTMECH for the Musim Stream, an urban tributary in Korea. The results were compared with field observations for verification.

To verify the reproducibility of the model, on-site ADV (FlowTracker 2) measurements performed at six points on 10 July 2025 were utilized. For water depth reproducibility, the RMSE was 0.0176 m, MAPE was 4.28%, and NSE and R2 were 0.9458, respectively, showing very high accuracy and consistency. In the case of flow velocity reproducibility, RMSE was 0.0160 m/s, MAPE was 4.36%, and NSE and R2 were 0.8681, respectively, confirming high predictive performance even though it was slightly lower compared to the water depth.

When the FI and FHR indices were applied to the flood event, the results were interpreted according to the classification criteria proposed by Beffa [33] and HR Wallingford [34]. Based on Beffa [33] criteria, the FI values indicated that low- and medium-damage areas were widely distributed. However, in sections where the flow velocity exceeded 1 m/s, FI—which is calculated as the product of velocity and depth—showed an increase in hazard level from medium to high. By contrast, owing to the calculation structure that includes the (velocity + 0.5) term, most floodplain areas corresponded to the “extreme risk (≥2.0)” category according to HR Wallingford [34] classification. Although this may overestimate the potential for human and structural damage during flood events, the FHR results provide a more conservative assessment than FI, which is advantageous for ensuring safety.

To analyze erosion and deposition tendencies, the TEDI and SEDI were applied. The calculated values of each index were normalized by dividing them by their respective mean values, allowing the indices to be evaluated within a range of 0–1. In this normalization, values closer to 1 indicate a higher probability of erosion occurrence, whereas values closer to 0 indicate a greater likelihood of deposition. TEDI was calculated by reflecting changes in flow velocity over time (acceleration term), and it exhibited values higher than 0.9 in the curved sections and in sections with high curvatures. This shows that it effectively identifies sections with rapid changes in flow velocity under unsteady flow conditions. Conversely, SEDI exhibited high values of approximately 0.8 in the main channel and high-flow velocity sections, as it was calculated based on the average flow velocity and water depth. However, SEDI could not sufficiently explain the distribution of erosion and deposition inside floodplains. Furthermore, the SEDI values obtained in this study were relatively higher than those obtained in Song et al. [29]. This can be attributed to the difference in spatial scale, as the previous study was conducted on a large river, whereas the present study focused on a small urban stream, where the scale effect is more pronounced. Therefore, this study suggests that indices should be modified considering the river scale.

In the results of drone-based monitoring performed immediately after the flood, sections with high TEDI values coincided with areas where deposition (mud and sand) or local erosion (revetment damage and lawn area erosion) actually occurred. Conversely, SEDI was effective in predicting the erosion risk for the main channel. However, because it assumes steady and uniform flow conditions, it has limitations in predicting detailed erosion and deposition patterns around floodplains or waterfront facilities. Therefore, a complementary application of TEDI and SEDI that considers actual field conditions is necessary. The results of the flood hazard (FI, FHR) and erosion–deposition indices (TEDI, SEDI) have practical implications for engineering design and river management. From a design perspective, the findings support risk assessment for new facilities and site selection that considers erosion and deposition effects. From a management perspective, the indices help identify erosion- or sedimentation-prone zones, guiding maintenance and monitoring priorities. Together, these applications demonstrate the value of integrating hydraulic safety into both design and management strategies. Nevertheless, although TEDI and SEDI are effective in identifying relative erosion and deposition tendencies, they remain limited in providing quantitative estimates of actual erosion or deposition volumes. To address this limitation, enhancing the efficacy of these indices by incorporating field measurement data—particularly physical parameters such as local bed and critical shear stresses, which are the most direct indicators—will be necessary. This would facilitate the evolution of the proposed indices as quantitative tools for predicting flood-induced damage and, in turn, provide a more scientific basis for long-term river management planning, as well as prioritizing the layout and reinforcement of waterfront facilities in floodplains.

5. Conclusions

The two-dimensional numerical model (FaSTMECH) was used to estimate flood hazard (FI, FHR) and erosion–deposition (TEDI, SEDI) indices in the Musim Stream floodplain. This integrated hydraulic–morphodynamic approach advances beyond previous water-level-based analyses, allowing a more realistic evaluation of floodplain safety. The analysis revealed that both FI and FHR generally indicated high hazard levels. FHR was predominantly found in the “extreme (dangerous to all)” category, providing a conservative criterion for ensuring the safety of infrastructure and human life within the floodplain. By contrast, FI identified several areas with intermediate hazard levels, which allowed for a more spatially detailed flood risk assessment. This suggests that FI, rather than broadly designating hazardous zones, has practical value in enabling stepwise hazard evaluation.

With respect to the erosion and deposition indices, TEDI reflected local changes in flow acceleration, showing elevated values in curved sections and regions with high curvature, which corresponded well with observed scour and deposition zones after flooding. SEDI, conversely, captured overall high values in the main channel and high-velocity zones by considering mean velocity and depth, but it was less effective in describing fine-scale erosion and deposition patterns within the floodplain. These results indicate that TEDI is sensitive to local variations arising under unsteady flow conditions, whereas SEDI serves as a more stable index based on long-term average conditions. Therefore, the two indices are most effective when used complementarily, enabling the identification of hazardous zones around floodplain structures with higher reliability.

Overall, the FaSTMECH model accurately reproduced the spatial distribution of the flow velocity and water depth in Musim Stream floodplains. FI and FHR were useful for evaluating the overall scale of flood risk ratings, while TEDI and SEDI were useful for evaluating local erosion and deposition tendencies in a complementary manner. Particularly, TEDI exhibited its strength in predicting flood damage locations under unsteady flow conditions due to changes in flow rate caused by flooding.

This study, however, has some limitations. As it applied indices based on a quasi-steady-flow model using only flow velocity and water depth data, the approach has limitations in quantitatively evaluating erosion and deposition processes. The model does not fully represent the effects of transient turbulence or sediment-size variation, which can influence local scour and deposition dynamics.

Future research combining field measurement parameters such as tractive force, critical shear stress, and particle-size-specific suspended sediment concentrations obtained from LISST-200X sensors is expected to contribute to quantitative flood damage prediction and improve the physical reliability of the proposed indices. If on-site measurement data, such as tractive force and critical shear stress, are combined in the future, quantitative damage prediction will be possible. This approach is expected to provide a scientific basis for long-term river maintenance plans, disaster prevention plans, and design/layout optimization for waterfront facilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D.K. and J.K.; methodology, T.G.K. and J.K.; validation, G.O.; formal analysis, T.G.K. and S.L.; investigation, J.K.; data curation, J.K. and G.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.D.K. and J.K.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, Y.D.K.; funding acquisition, Y.D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through Research and Development on the Technology for Securing the Water Resources Stability in Response to Future Change, funded by Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE), grant number RS-2024-00397820.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they include results from an ongoing study and data acquired from areas managed by local governments, which are subject to restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to [ydkim@mju.ac.kr].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FaSTMECH | Flow and Sediment Transport with Morphological Evolution of Channels |

| TEDI | Transient Erosion and Deposition Index |

| SEDI | Steady Erosion and Deposition Index |

| FI | Flood Intensity |

| FHR | Flood Hazard Rating |

References

- Choi, S.Y.; Han, K.Y.; Kim, B.H.; Kim, S.H. Parameter Assessment for the Simulation of Drying/Wetting in Finite Element Analysis in River and Wetland. J. Environ. Impact Assess. 2009, 18, 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.G.; Lee, L.Y.; Lee, C.W.; Kang, N.R.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, H.S. Analysis of Flood Reduction Effect of Washland using Hydraulic Experiment. J. Wetlands Res. 2011, 13, 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.H. A Study on the Change of Water Quality Characteristics Considering Waterfront Activity, Seasonal and Hydraulic Factors in Waterfront Areas. Ph.D. Thesis, Kwangwoon University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; An, J.; Ji, M.-K. A Guide for Environmental Impact Assessment for the Installation of Water-Friendly Facilities in River Zones. Clean Technol. 2023, 29, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdan, M.M.S.; Ahad, M.T.; Kumar, R.; Mehedi, M.A.A. Estimating Flooding at River Spree Floodplain Using HEC-RAS Simulation. J 2022, 5, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Jeon, W.; Ko, H. Analysis of Flooding Patterns in River Terraces. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2022, 22, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.H.; Song, C.-G.; Park, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.D. A Study on the Field Application of Nays2D Model for Evaluation of Riverfront Facility Flood Risk. KSCE J. Civ. Environ. Eng. Res. 2015, 35, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S.; Green, C.; Nicholls, R.J.; Corfee-Morlot, J. Future Flood Losses in Major Coastal Cities. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Mentaschi, L.; Voukouvalas, E.; Bianchi, A.; Dottori, F.; Feyen, L. Climatic and Socioeconomic Controls of Future Coastal Flood Risk in Europe. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, S.B.; Dawson, R.J.; Kilsby, C.; Lewis, E.; Ford, A. Future Heat-waves, Droughts and Floods in 571 European Cities. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 034009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, J.L.; Mailhot, A.; Brissette, F. Global and Regional Projected Changes in 100-yr Subdaily, Daily, and Multiday Precipitation Extremes Estimated from Three Large Ensembles of Climate Simulations. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, M.; Cea, L.; Van Uytven, E.; Willems, P.; Farfán, J.F.; Puertas, J. A Robust Method to Update Local River Inundation Maps Using Global Climate Model Output and Weather Typing Based Statistical Downscaling. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 4345–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulano, R.; Rianna, G.; Costabile, P.; Costanzo, C.; Del Giudice, G.; Mercogliano, P. Propagation of Variability in Climate Projections Within Urban Flood Modelling: A Multi-purpose Impact Analysis. J. Hydrol. 2021, 602, 126756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.H.; Song, C.G.; Kim, Y.D.; Seo, I.W. Analysis of Hydraulic Characteristics of Flood Plain Using Two-Dimensional Unsteady Model. J. Korean Soc. Civ. Eng. KSCE 2013, 33, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.-F.; Munasinghe, D.; Fang, Z.; Tsang, Y.P.; Cohen, S. Comparative Analysis of Inundation Mapping Approaches for the 2016 Flood in the Brazos River, Texas. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. (JAWRA) 2018, 54, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Huang, G. Evaluation of Flood Risk Management in Japan Through a Recent Case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Ji, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, B.; Xue, Z.; Li, Z. An Analytical Study for Predicting Incipient Motion Velocity of Sediments under Ice Cover. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Deposition and Erosion Relief of Riverfront by Vegetation. Ecol. Resil. Infrastuct. 2015, 2, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Julien, P.Y. Erosion and Sedimentation, 2nd ed; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. Computational River Dynamics, 1st ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldefae, A.H.; Al-Khafaji, R.A.; Shamkhi, M.S.; Kumar, H.Q. Erosion, sediment transport and riverbank stability: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 901, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Imamura, F.; Shuto, N. Numerical Simulation of Flooding and Damage to Houses by the Yoshida River due to Typhoon No. 8610. J. Nat. Disaster Sci. 1989, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.R.; Bennett, J.P.; Nelson, J.M. The USGS Multi-dimensional Surface Water Modeling System. In Proceedings of the 7th US Interagency Sedimentation Conference, Reno, NV, USA, 25–29 March 2001; pp. I-161–I-167. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.R.; Nelson, J.M.; Kinzel, P.J.; Conaway, J. Modeling Surface-Water Flow and Sediment Mobility with the Multi-Dimensional Surface Water Modeling System (MD-SWMS). U.S. Geol. Surv. Fact Sheet 2005, 2005–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; Bennett, J.P.; Wiele, S.M. Flow and Sediment-Transport Modeling. Tools Fluv. Geomorphol. 2003, 18, 539–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.H.; Kim, Y.D. Comparison of Two-Dimensional Model for Inundation Analysis in Flood Plain Area. J. Wetlands Res. 2014, 16, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, G.; You, H.; Kim, D. Feasibility Calculation of FaSTMECH for 2D Velocity Distribution Simulation in Meandering Channel. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2014, 34, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kail, J.; Guse, B.; Radinger, J.; Schröder, M.; Kiesel, J.; Kleinhans, M.; Schuurman, F.; Fohrer, N.; Hering, D.; Wolter, C. A Modelling Framework to Assess the Effect of Pressures on River Abiotic Habitat Conditions and Biota. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.G.; Ku, T.G.; Kim, Y.D.; Park, Y.S. Floodplain Stability Indices for Sustainable Waterfront Development by Spatial Identification of Erosion and Deposition. Sustainability 2017, 9, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; McDonald, R.R. Mechanics and Modeling of Flow and Bed Evolution in Lateral Separation Eddies. Rep. to Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center. 1996. Available online: http://www.riversimulator.org/Resources/GCMRC/PhysicalResources/Nelson1996.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Nelson, J.; McDonald, R.R.; Kinzel, P. Morphologic Evolution in the USGS Surface-water Modeling System. In Proceedings of the Eighth Federal Interagency Sedimentation Conference (8thFISC), Reno, NV, USA, 2–6 April 2006; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.J.; Kim, E.S.; Jeon, G.S.; Muhammad, A.; Lee, H.S. The Change of Flood According to Dividing Sub-Basin at Musim River. J. Inst. Constr. Technol. 2015, 34, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Beffa, C. Two-dimensional Modelling of Flood Hazards in Urban Areas. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Hydroscience and Engineering, Berlin, Germany, 31 August–3 September 1988; Brandenbur University of Technology: Cottbus/Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- HR Wallingford; Flood Hazard Research Centre and Risk and Policy Analysts Ltd. Flood Risk to People; Phase 2, FD2321/TR2, Guidance Document; Defra/Environment Agency Flood and Coastal Defence R&D Programme; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2006.

- Fanning, J.T. A Practical Treatise on Hydraulic and Water-Supply Engineering; D. Van Nostrand: New York, NY, USA, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, F.M. Open Channel Flow; Macmillan: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.G.; Ku, Y.H.; Kim, Y.D.; Park, Y.S. Stability Analysis of Riverfront Facility on Inundated Foodplain Based on Fow Characteristics. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, S455–S467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).