1. Introduction

The core components of refereeing a game are accurately perceiving complex situations, quickly processing crucial information, and consistently deriving the correct results [

1]. The specific requirements for a referee are strongly associated with the particular sport; based on these characteristics, one can categorise general referees as interactors, monitors, or reactors [

2]. However, the challenge of quickly and accurately processing visual stimuli is common across referees in all sports [

1]. Thus, the need for referees to possess excellent visual perception and processing skills is universally valid [

3,

4,

5]. Measuring the quality of visual-cognitive abilities can be assessed either in a sport-specific context representing the requirements of a realistic setting (domain-specific) [

6,

7] or by the use of more generic tests with no direct link to the sports setting (domain-generic) [

4]. Following the need for perceptual accuracy in referees, studies have shown that elite referees perform better than amateur referees in various sport-specific visual-cognitive tasks, such as processing relevant stimuli [

8], efficient gaze behaviour [

9], and choice of visual perspective [

10].

However, research has so far lacked empirical consensus on whether the sport-specific expertise is also reflected in a broader superiority of elite referees in domain-generic cognitive tasks [

11]. The current state of research suggests that the difference in performance between elite referees and amateur referees becomes comparatively smaller the more the tasks move away from the specific sports context and towards general non-sport-related tests [

11]. For example, Spitz et al. [

4] compared the performance of elite and amateur referees in four domain-specific (i.e., decision-making performance and recall capacity) and six domain-generic tests (i.e., sustained attention and local information processing). Results showed that elite referees significantly outperformed amateur referees in every domain-specific test but not in the domain-generic tests. Nevertheless, when Spitz et al. [

4] developed a statistical model that predicts the performance of referees in a decision-making task using video clips of foul situations, the best-fitting model included the results of one domain-generic test in addition to the four domain-specific tasks to predict referee performance optimally. Thus, although domain-generic test scores did not significantly differ between elite and amateur referees, the domain-generic tests were partially meaningful in predicting a referee’s performance. These results reflect the current state of research, that is, on the one hand, generating convincing evidence for elite referees having superior domain-specific cognitive abilities compared with amateur referees and, on the other hand, giving more mixed results regarding domain-generic cognitive abilities [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Researchers have proposed various causes for the diverse findings regarding domain-generic abilities in referees [

4,

11,

15,

16]. However, the question remains open as to how much superior general visual abilities contribute to an individual’s ability to become an elite referee. On the one side, researchers have argued—based on the expert performance approach [

17] and the findings summarised by Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers” [

18]—that expertise in most domains, be it music, art, or sports, is primarily acquired by continuous practice (10,000 h of practice to become an expert). On the other side, studies have identified general cognitive abilities that are mainly stable (i.e., abilities that do not naturally change in the course of a life and are robust against attempts to improve their functionality [

19]). However, they have a measurable impact on success for individuals in various domains, such as medicine [

20], economics [

21], and sports [

22]. Although the magnitude of the encoded variance of general cognitive abilities on expertise varies between studies and domains, results of meta-analyses suggest that the impact of general cognitive ability on success is dependent on the complexity, context, and specificity of the performance demands of the task in which individuals want to succeed and develop expertise [

19,

23], meaning that general cognitive abilities become more important as the complexity of the task increases. Following this argumentation, high-quality refereeing should at least be partly related to general cognitive ability because refereeing can be described as highly complex, including various tasks and requiring continuous adaptation of the referees to the changing dynamics of the game [

24].

So far, only a few studies in sport psychology have investigated the relationship between general cognitive abilities and expertise in referees, and those studies that did, reported differing results [

11,

24]. Furthermore, studies investigating referees encounter various challenges that might contribute to the heterogenous results [

11]. Firstly, research in sports psychology is mainly conducted with athletes, and the available data concerning referees is much smaller [

25]. Secondly, in most sports, the pool of professional referees officiating top-level games is small [

26]. Thirdly, Avugos et al. [

11] reported an absence of an adequate control group in most studies investigating cognitive abilities in referees. Lastly, it is essential to accurately determine which areas of general cognitive abilities (for example, attention, concentration, abstraction, perception, etc.) could theoretically enhance performance in tasks; however, in refereeing, there are multiple tasks a referee must fulfil in a game (e.g., making accurate decisions, retaining the game’s flow, and controlling the game) [

24]. Therefore, selecting the proper tests to assess important cognitive abilities for refereeing is challenging.

The current study aims to address these challenges by examining a sufficient sample size (via cooperation with the German basketball federation), adding a control group, and focusing on only one area of general cognitive ability. The area we assessed in this study is visual-cognitive ability because referees’ performance is primarily determined by the accuracy of their decisions, and referees primarily base their in-game decisions on the visual information they receive [

27]. Furthermore, numerous studies have reported significant effects on visual abilities between referees with different expertise and sport-specific tasks (among others, anticipation [

12], gaze behaviour [

9], and recall capacity [

4]). Thus, this study aims to investigate whether similar effects can be found between referees with different expertise for the same abilities but in general cognitive tests. Based on studies that have found significant expertise effects of sport-specific abilities in referees, we assessed the following general visual-cognitive abilities [

3,

4,

8,

16,

28]. All of these constructs involve processing information by the visual system in order to make predictions about the environment and determine behavior [

28].

(1) The capacity of the spatial working memory: The capacity of individuals to store and access perceived stimuli in the spatial working memory is limited and individually varies. In practice, a referee with more capacity would have more information about a situation. Significant effects in sport-specific tasks were reported by Gilis et al. [

8] and Spitz et al. [

4].

(2) Visual orientation: In sports, referees must often evaluate spatially crowded and chaotic situations. Visual orientation, meaning the ability to distinguish single details of different stimuli close to each other, is, thus, critical. Significant effects in sport-specific tasks were reported by Ghasemi et al. [

29].

(3) Perceptual speed: In addition to the accurate perception of stimuli, it is also relevant for referees to process stimuli quickly and maintain the game’s flow [

1]. Significant effects in sport-specific tasks were reported by Ghasemi et al. [

29,

30].

(4) Spatial anticipation: Because sports games consist of multiple simultaneously occurring situations, it is not always obvious where the referees must focus their attention [

31]. Therefore, it is crucial for refereeing to predict upcoming critical situations and focus their attention on them [

8]. Significant effects in sport-specific tasks were reported by Spitz et al. [

4] and van Biemen et al. [

32].

(5) Time anticipation: It is relevant to anticipate the direction and the velocity of movement to predict upcoming critical situations. Significant effects in sport-specific tasks were reported by van Biemen et al. [

32].

Still, there are distinctive considerations when interpreting performance in general cognitive abilities compared with sport-specific testing. For example, general cognitive abilities tend to decrease with age [

33]. Furthermore, other socioeconomic factors, such as educational background, were found to correlate with performance in general cognitive abilities [

33]. Therefore, it is advisable to control for socioeconomic factors, such as age and educational level, when measuring general cognitive abilities in different groups to ensure that significant differences reflect the research question and not only differences in socioeconomic status [

34].

Based on the presented theoretical and empirical background, our study compares the performance of referees with different levels of expertise in several visual-cognitive tests. Additionally, we included a control group composed of individuals with a high educational level and of a relatively young age with little-to-no basketball experience. This group serves as a representative comparison for a non-basketball-related group. Thus, we hypothesised that there are group differences in specific test scores; however, since little research was conducted on this topic, we could not predict the exact direction of effects between groups for each test. Furthermore, we must consider moderating factors, such as age and educational level, that additionally aggravate specific directional hypotheses. Therefore, we only formulated explorative hypotheses and adjusted the multiple tests with the most conservative method in order to minimise the possibility of alpha error cumulation.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is a quasi-experimental between-subject design with one independent variable (referee’s expertise) consisting of 3-factor levels (elite referees, amateur referees, and novices) and five dependent variables (performance in spatial working memory, visual orientation, perceptual speed, spatial anticipation, and time anticipation). A correlation matrix with age, education level, and all dependent variables can be found in

Table S1 of the

Supplementary Materials to control for the influence of other demographic variables. The reliability values in the current study are similar to the results reported in the paper by Ong [

35], who performed a comprehensive analysis of the Vienna Test System in sports.

Because the number of elite basketball referees in Germany working in the first and second leagues is limited to 60, we did not calculate an a priori power analysis but rather aimed to recruit 30 elite referees and adjusted the sample size of the remaining groups to ensure an equal number of participants for each group. The participants were grouped based on their current level of refereeing performance. The final sample included 26 elite basketball referees (male = 23, female = 3) from the first and second German basketball leagues, 30 amateur basketball referees (male = 27, female = 3) from leagues below the first and second German basketball league and 30 novices (male = 15, female = 15) with no refereeing experience. The age of elite referees ranged between 25 and 47 years (M = 35.9 ± 7.1 years), amateur referees were between 18 and 47 years (M = 29.4 ± 5.6 years), and novices were between 21 and 31 years (M = 24.9 ± 2.4 years) old.

The study was approved by the ethics board of the leading university. Written consent was obtained from all participants before testing. First, the participants completed demographic questions on age, sex, and education level, followed by the general instructions for the Vienna Test System. The Vienna Test System is a computerised system that can analyse different constructs related to cognitive diagnostics and psychology. It was developed by Schuhfried

® GmbH (Moedling, Austria) as a reliable and valid tool for psychological assessment [

35]. The average processing time for the tests was

M = 28.52 min and

SD = 6.11 min. All the participants were allowed to take a break and were not limited in time after each test. The individual tests in the Vienna Test System are described below.

(1) The Corsi block-tapping test (test form: S5) measured the storage capacity of the spatial working memory. The participants had to observe nine irregularly arranged cubes. A cursor touched a certain number of cubes in turns. The participant’s task was to repeat the given sequence in reverse order. The sequence length increased after every third item until the participant committed an error in two of the three items with the same sequence length. Their performance was determined by the number of sequences completed.

(2) The visual pursuit test (test form: S2) measured visual orientation performance and visual perception. The participants were presented with several random and disorderly lines and were asked to visually identify the end of a particular line as quickly and accurately as possible. Two keys on the participants’ panel had to be kept depressed throughout the task to ensure that the lines were not traced with the finger. Their performance was determined by the number of correctly selected line endings and the processing time duration.

(3) The perceptual speed test (test form: S1) measured perceptual speed and peripheral vision. The participants saw two pictures at short intervals, which differed in three details. The participants had to identify the differences between the first and second images. The number of correctly chosen differences determined their performance.

(4) The time and spatial anticipation test (test form: S2) measured two separate constructs, (1) the ability to estimate the direction of movement of an object and (2) the ability to estimate the speed of an object. The participants had to trace the path of a moving ball on the screen. The ball unexpectedly disappeared, and two parallel red lines appeared in its place. One line passed through the point where the ball had just disappeared. The other was the target line. The participants had to press a button when they thought the ball should have reached the target line. Additionally, the participants had to indicate the spatial point where they thought the ball would have crossed the target line. Their performance was determined by the deviation between the participant’s estimate of the ball’s speed and crossing point and the ball’s actual speed and crossing point. All visual-cognitive tests of the Vienna Test System demonstrated an internal consistency over Cronbach’s α > 0.719. The values for the individual tests can be found in

Table S2 of the

Supplementary Materials. Additionally, the criterion validity of the tests for the Vienna Test System was determined by their creators. They reported that all tests showed a correlation coefficient (r) of greater than 0.21 with other measures of the specific cognitive ability being assessed (details of the individual measures can be found in

Table S2).

All statistical procedures were performed using IBM SPSS software version 27 [

36]. We performed five separate ANOVAs between the three-factor levels of the independent variable referee’s expertise level for the scores of the dependent variables in spatial working memory, perceptual speed, visual orientation, time anticipation, and spatial anticipation. Due to a technical issue, a part of the data of elite basketball referees for the perceptual speed test was missing (

n = 9; 17 (65.4%) were missing). Since we performed five tests, a Bonferroni correction was conducted, resulting in an adjusted alpha level of 0.01. Additionally, multiple comparisons were conducted for every ANOVA that reported a statistically significant effect. The interpretation of effect sizes was based on current guidelines for effect size clarification in psychological science. An effect size of

η² < 0.06 was considered small at the level of single events (but potentially more consequential in the long run), an effect size

η² > 0.06 < 0.14 was considered medium (some explanatory and practical use in the short run), and an effect size of

η² > 0.14 was considered large (impactful in the short term and potentially powerful in the long term) [

37].

3. Results

Assumptions for normal distribution and homoscedasticity were checked with graphical measures for each group (Q–Q plots) and additional Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests. Results partly reported significant violations of the normal distribution assumption and homoscedasticity assumption. The values of both tests for the five tasks can be found in

Table S2 of the

Supplementary Materials. The preconditions for multiple ANOVAs were not completely fulfilled; however, previous research has shown that ANOVAs are robust against violations of normal distribution [

38]. Nevertheless, we performed additional non-parametric procedures (Kruskal–Wallis test) to confirm the validity of our results. Statistically significant effects between the different groups and the Vienna Test System results do not differ between the ANOVAs and the Kruskal–Wallis tests. In the following section, only the results of the ANOVAs are reported; the results of the Kruskal–Wallis tests can be found in the

Supplementary Materials,

Tables S3 and S4.

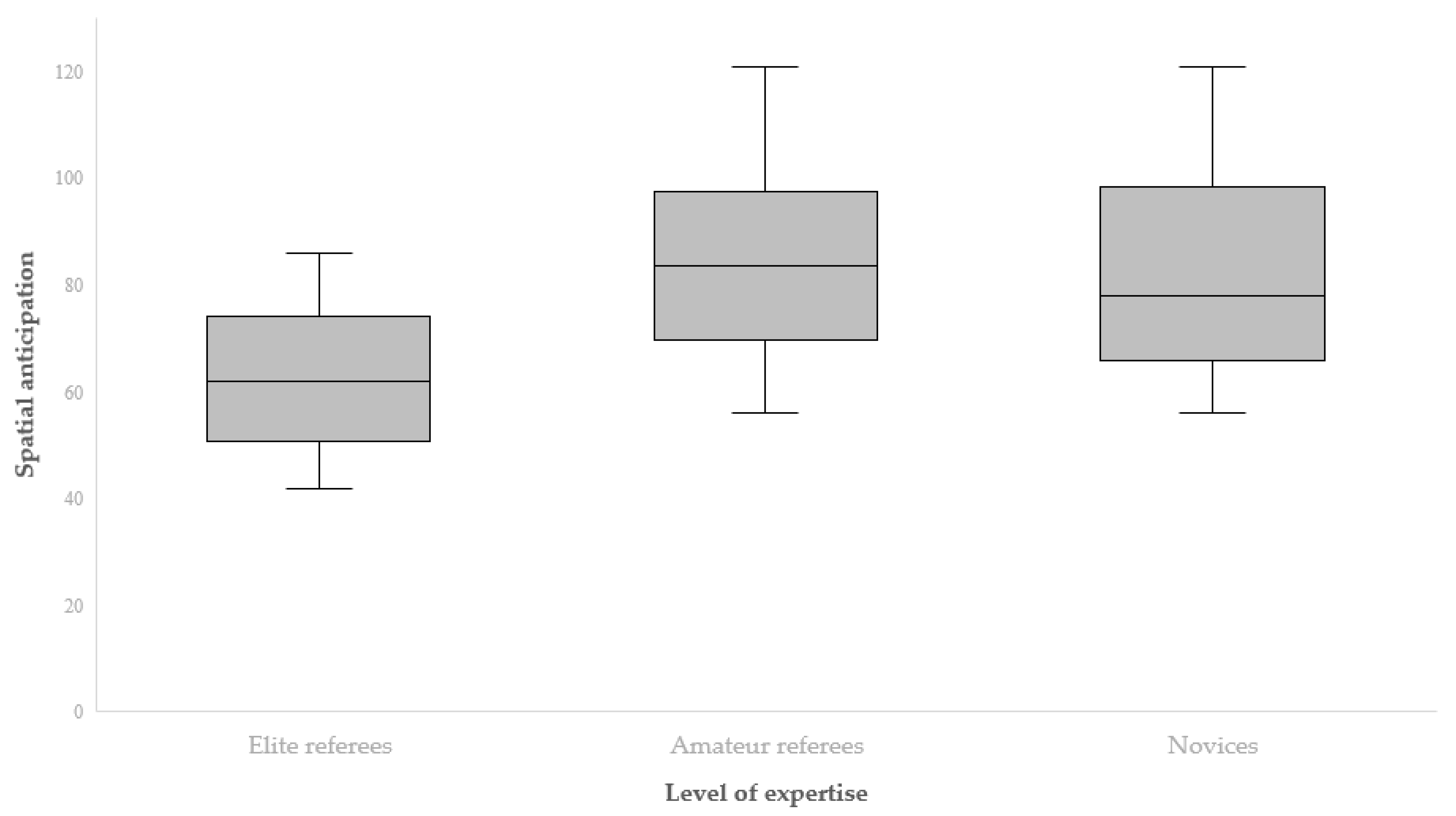

We conducted five separate ANOVAs with one independent variable (3-factor levels: expert referees, amateur referees, and novices) for all five test results. Additionally, we performed Bonferroni-corrected multiple comparisons. Descriptive statistics,

p-values, and effect sizes for the five ANVOAs are reported in

Table 1. Only the difference between test results in spatial anticipation is statistically significant,

F(2, 83) = 14.49,

p < 0.001, partial

η² = 0.259. Multiple comparisons between groups for spatial anticipation scores reveal a significant difference between the elite referees and amateur referees,

p < 0.001 (

Mdiff = −22.79, 95%-CI [−33.96, −11.63]), and elite referees and novices,

p < 0.001 (

Mdiff = −19.99, 95%-CI [−31.16, 8.83]), but not between amateur referees and novices,

p > 0.999 (

Mdiff = −2.80, 95%-CI [−13.56, 7.96]). A graphical representation of the effect is reported in

Figure 1. Thus, the elite referees performed better than the amateur referees and the novices. However, the results of the amateur referees and the novices do not significantly differ.

4. Discussion

The current study investigated the performance of basketball referees with different expertise levels in various general visual-cognitive abilities. Only in spatial anticipation did elite referees perform significantly better than amateurs and novices. Besides that, there were no significant differences in performance between groups on the other tests. However, a trend emerged that in all visual-cognitive skills (descriptively judged by the mean test scores of the groups), novices performed best, elite referees second best, and amateur referees third best (except for spatial anticipation). In general, the results of this study fit into the mixed findings of previous studies that have investigated general cognitive abilities in referees [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Our findings indicate that elite referees do not possess superior visual-cognitive abilities per se. However, the results regarding spatial anticipation suggest that the ability to anticipate movement is a possible exception, which might indicate that spatial anticipation is an essential skill to become an elite referee. We assumed that educational level and younger age would positively correlate with the test scores in all visual tests [

34]. However, the correlations between educational level and test results can be described as low. This can be partly explained by the very high educational level (70.9% had a university degree) of the overall sample and the low age range within the sample.

While these correlations provide some information about the relationship between visual-cognitive abilities and refereeing, they do not offer much insight into the importance of specific abilities in refereeing. In contrast, the significant effect found in spatial anticipation tasks does provide such information. The significance of anticipation skills in refereeing is not a novelty; numerous studies have reported the relevance of various domain-specific anticipatory skills for good referee performance [

28,

32,

39]. However, our results further indicate a deeper meaning of general spatial anticipation for the success of referees, especially when considering the large effect size. Elite referees anticipated the movement of a target object on average 25% more accurately than amateur referees and novices. We assume that this competence of elite referees in spatial anticipation reflects that referees with better general spatial-anticipatory abilities have a higher chance of becoming elite referees in basketball. Specifically, it might indicate that referees with better spatial anticipatory skills make, on average, more accurate decisions, leveraging their chances to further their careers more quickly. The question of to what extent this improvement in competence translates into practical benefits for basketball referees is a matter of debate. Future research should investigate the possible practical implications of this finding in a deeper understanding. More precisely, we recommend further bridging this study approach to other groups of referees and discussing how the discrepancies in different sports could also be reflected in discrepancies in referees’ skills.

Beyond this practical relevance, our results indicate that the required skill set to perform well as a referee may not be limited to only sport-specific anticipatory skills but should be investigated in a broader approach, thus, considering anticipation skills on a general level. However, the question remains about how the elite referees acquired superior general spatial anticipatory skills. Here, we consider two possibilities: (1) Due to continuous training and experience, referees improve their anticipation of player and object movement for their specific sport; Consequently, this training leads to a universal improvement in spatial anticipation, and (2) only individuals with outstanding anticipatory skills are selected to become elite referees in the first place.

The latter possibility must be considered more probable since research has shown that general visual-cognitive abilities are robust and cannot be easily improved by continuous training or interventions [

34]. Since general visual-cognitive abilities are stable constructs that hardly alter throughout a lifetime (only with a tendency to decrease with increasing age or as a result of injury or disease [

33]), it seems not likely that referees developed better general anticipatory skills in the course of their career. It is more plausible that elite referees already possessed superior general anticipation skills before they started their careers. However, this does not mean that referees are directly selected for higher leagues based on their general anticipation skills; it is conceivable that referees with better general anticipation skills perform better in-game and, as a result, are promoted to higher leagues. Based on the results of this study, it is possible that general spatial anticipation skills are an inherent talent that is necessary for successful refereeing.

While this study provides some insight into referees’ general cognitive skills of visual processing, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Due to its quasi-experimental design, it does not allow the determination of the source of the differences in performance. In addition, it remains unclear to which extent these general cognitive abilities are detrimental to the performance of referees, and future research should further investigate this relationship. However, due to the comparatively large sample and the inclusion of socioeconomic factors that might mediate the relationship between general cognitive abilities and expertise, we consider that the reported results provide a valuable contribution to explaining the requirements expert referees must meet. Nevertheless, this does not mean this study provides direct, compelling evidence that anticipatory abilities predict good referee performances. However, it provides evidence that elite referees have excellent spatial anticipatory abilities compared with less experienced referees and novices. Future research should focus on intervention programs that enhance the anticipatory abilities of participants and investigate whether this increase in anticipatory abilities also enhances referees’ performance in-game. The results of this study indicate that this might be the case. Because only basketball referees were recruited for this study, future research should investigate whether the proficiency of elite referees in general spatial anticipation is limited to basketball or if it applies to referees (especially interactors) across sports. However, it is reasonable to assume that the current findings of basketball referees can be generalisable to other sports referees, as many of the cognitive skills required for successful refereeing are similar across sports [

1,

40]. Referees, regardless of the sport, are responsible for making split-second decisions, monitoring the movement of multiple players and objects, and interpreting complex rules and regulations.