Abstract

This paper proposed implementing a water and air monitoring system using sensor development and a LoRa Network. To transmit data, a self-made PCB board integrates the terminal sensors with Renesas RX64M MCU and LoRa. There are 16 monitoring point stations for the media experiment. The sensors were used to measure the water and air parameters such as PM2.5, CO2, DO concentration, pH level, temperature, and humidity. In addition, the Grafana system was implemented to present the status and variation in the monitoring parameters in the environmental area. To evaluate the monitoring system, we also collected public information provided by the environmental protection department of the Taiwan government at the same monitoring point for comparison.

1. Introduction

For effective process monitoring and enhanced control in wide areas, reliable and accurate real-time measuring is essential. The case study of air pollution and water monitoring was the paper’s main objective to implement the LoRa network. We are all aware that haze is hazardous to one’s health. Domestic thermal power plants and pollutants from the industrial output and dust diffusion contribute to Taiwan’s air pollution [1,2,3]. In this era of the IoT, to understand the status of air pollution, it is necessary to select points and monitor them. LoRa, a low-power, wide-area network modulation technology (LPWAN), refers to long-range data communications. LoRa allows for long-range communications of up to three miles or five kilometers in urban areas and up to ten miles or 15 km in rural areas. The ultra-low power requirements of LoRa-based systems are a crucial feature, allowing for the design of battery-operated devices that can last up to 10 years. A star network based on the open LoRaWAN protocol is suitable for an implementation scheme that needs long-range or deep in-building communication [4].

Numerous scholars worldwide have predicted that Internet of Things (IoT) computing will become a dominant paradigm. The majority of focused research areas are located at the intersections of these three major fields (cloud computing, mobile computing, and the IoT), as well as at the intersections of all three. Several cutting-edge and developing computer concepts are concentrated in such areas. Among these are Mobile Cloud Computing (MCC), cloudlet computing, mobile clouds, fog computing, and edge computing, to name a few [5,6]. LoRaWAN, according to the LoRa Alliance, addresses important Internet of Things (IoT) criteria such as secure bi-directional communication, mobility, and location services. The LoRaWAN standard enables the rollout of IoT applications by providing seamless interoperability among smart items without the need for complicated local installations. Low-power, wide-area networks, according to experts, will account for a large share of the expansion of IoT devices in the next years [7].

In this paper, we adopted two strategies. First, we use a low-power LoRaWAN network (low-power, wide-area network technology), which is capable of long-distance transmission [8,9]. Second, we use solar cell charging equipment to achieve self-contained power without constraints on the power supply issue. In this way, we solve the power supply problem, and the logging data can be transmitted remotely [10,11,12]. In this case, this work sets up six sets of monitoring stations in Tunghai University. In each station, we use PM2.5, CO2 concentration, temperature, and humidity sensors. Every minute after processes logging data, the data were sent back to the database system based on the OSM map (Open Street Map) [13,14]. Therefore, the objectives of this paper are listed as follows:

- Implement the LoRaWAN network in an air quality and water monitoring system;

- Evaluate the performance of the LoRaWAN receiver in terms of sensitivity and throughput.

2. Background Review and Related Works

2.1. LoRa Low Power Consumption Network

LoRa means “remote” and is extended by the LoRa Union remote wireless communication system. This system is designed for equipment powered by batteries with long life spans that are critical to energy consumption [15,16]. The uplink uses a significant amount of data to send the measurement data, while the downlink is primarily used for acknowledgment in many applications [17].

2.2. LoRa Network Architecture

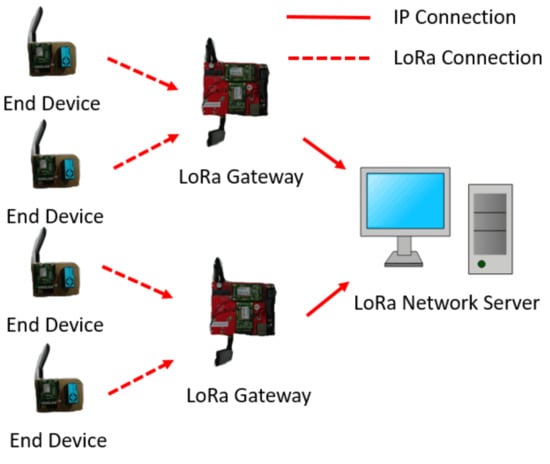

A LoRa network is usually referred to as a “star-like network”, as seen in Figure 1, because it comprises at least three different types of devices. The LoRaWAN network’s basic architecture is as follows: (1) The terminal communicates with the gateway using LoRa and LoRaWAN [18]. The data from the terminal device are sent to the webserver through a high-throughput interface (often 4G, 3G, or Ethernet). (2) The gateway merely serves as a two-way relay or protocol converter, and (3) the network server is in charge of decoding packets received from the terminal and producing packets to be transmitted back to the terminal [19,20].

Figure 1.

LoRa Network Composed of Three Different Types of Equipment.

2.3. Arduino Development (Pre-Development for Rapid Implement)

Arduino’s appearance was due to the fact that students of a teacher at a high-tech design school in Italy often complained that a cheap and easy-to-use microprocessor controller could not be found. The teacher, named Massimo Banzi, worked with another teacher, David Cuartielles, and Spanish chip engineer Discuss to design their own circuit boards, and introduced the student, David Mellis, to the circuit board design and development language; they named this circuit board “Arduino” [21,22].

Arduino is an open hardware platform based on the open source spirit, which uses a signle-chip Atmel AVR (Note 1). Its language is the C/C++ language development environment, similar to Java.

2.4. Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW)

IDW is a deterministic multivariate interpolation method that uses a known distributed set of points. A weighted average of the values available at the known points is used to assign values to unknown points. The range of the interpolated values calculates the specified weight. The concept is an unknown value point that is inversely proportional to the value distance of the known point around it; the further the distance, the lower the degree of impact. The degree of impact between the unknown point and the established point is the force of the distance. The formula is presented as follows:

where is the weight equation, where is i of the value’s first known point, and is i of the distance from the point to the unknown point. The inverse ratio of the power determines the size.

2.5. Related Works

The remote and low-power network of the Internet of Things is an important subject of future urban development. In 2016, Augustine et al. [8] studied and evaluated LoRa, providing an overview of the technology and a detailed examination of its functional components. Field testing and simulation were used to assess the performance of the physical and data link layers. On this basis, some prospective enhancement solutions are given.

Juha Petäjäjärvi et al. [23] tested the performance of the LoRa interior in 2016 at the University of Oulu, where there were more than 570 m northeast of East Asia and 320 m west of the main area using 14 dBm of transmit power and 868 MHz ISM band 12. Of the maximum spreading factor, the entire campus area can be covered. The measured packet delivery rate was 96.7%, with no acknowledgment or retransmission.

In 2014, Andrea Zanella et al. [24] produced the Smart City website, a thorough review of urban Internet technologies, protocols, and architectures, as well as technical solutions and best practice guidelines, centered on the City Internet of Things system.

M. Lauridsen et al. [25], published in March 2017, focus on LoRa and SigFox of the Interference in the European 868 MHz ISM Band with five different locations, which is referred to as the LoRa 868 MHz ISM band interference test: point out shopping, commercial parks, hospital complexes, industrial areas, and residential areas, where RFID interrogator signals occupied the 865–868 MHz band and which may prevent LoRa and SigFox deployments. Channels need to be switched to avoid this problem.

Bhardwaj et al. [26] designed and implemented Cloud-WBAN, an experimental framework that not only brings the cloud computing system closer to the WBANs user (edge-of-things computing) but also automatically adjusts the computing resources (at cloudlet) to maintain the WBANs users’ service level agreements (SLAs) based on the volume and type of sensory data. The efficacy of the suggested strategy is assessed, and the experimental findings demonstrate that when compared to other methods, the proposed approach increases resource utilization by at least 26% and reaction time by at least 49%. In addition, Bhardwaj et al. [27] present a new elasticity controller that combines fuzzy logic control with autonomic computing for autonomic resource provisioning. This controller calculates the needed number of processor cores based on the internal workload of the program and the virtual machine’s resource consumption. In comparison to existing methods, the suggested methodology reduces the finishing time by up to 64% and boosts resource usage by up to 36%, according to the test results.

D. M. Hernandez et al. [11] published an energy and coverage study of a LPWANs schemes for Industry 4.0 in May 2017, which mentions that low-power broadband networks (LPWAN) are becoming one of the major components of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). The combination of network topology could cover large urban areas similar to the indoor environment when using energy-efficient transmission.

T. Peter et al. [12] published the performance and analysis of LoRa in September 2016. LoRa technology offers excellent outdoor coverage results in urban or rural areas, with very low frame losses (about 3%) under optimal conditions. Water quality must be continuously monitored before it is released into the environment. Kamidi et al. [28] use an Arduino UNO R3 to capture water quality data. The parameter is then sent through WiFi via the 8266 module. Data were collected and processed with Spark MLlib using a Deep Learning model. If the parameter exceeded a previously determined threshold, an SMS alert was sent. The SMART-WATER infrastructures technology allows for the tracking and control of water consumption via websites [29]. To send logging data, they use a variety of communication protocols. The LoRa and wMBus wireless protocols are used to communicate with terminal devices, and NB-IoT and GSM cellular are used to connect them to the cloud [30], a suggested method for providing real-time data for smart cities based on IoT and Wireless Sensor Network. The current method relies solely on wireless technology, which is limited in range and consumes more power. They switched to LoRaWAN, which allowed them to cover a greater distance than Wi-Fi. Gangwani et al. [31] proposed IOTA, a new distributed ledger system for the Internet of Things. It is based on a directed acyclic graph. IOTA circumvents the blockchain’s present restrictions by providing a data communication protocol called masked authenticated messaging that enables safe data sharing between Internet of Things (IoT) devices.

To make our study different, we implemented LoRaWAN architecture on wide areas in real-time at Tunghai University. We also compared the performance between the LoRa module and WiFi, such as in terms of energy use. For the LoRa’s performance, we evaluated more details on receiver sensitivity data collection in the 915 kHz channel, receiver sensitivity data collection in the 868kHz bands, the actual results of sensitivity receiving, and the average throughput.

3. System Design and Implementation

In this section, we describe the LoRa system’s architecture and implementation in this paper, which established an air pollution and water monitoring system on the Tunghai University campus. The characteristic of this system, just like [32,33], efficiently assess real-time air quality information and display and low power consumption of data transmission. In addition, the system supports historical data query and analysis. Finally, the proposed system has a user-friendly graphical interface.

3.1. System Environment

The system environment includes the hardware and software requirements. About the hardware, the list in Table 1 shows the components needed for the air quality monitoring station.

Table 1.

Monitoring Station Equipment.

For water monitoring, we used three sensors for logging data. In addition to PM2.5, we apply a Multi-parameter Water Quality Sensor for water quality sampling, which including dissolved oxygen, pH, and temperature sensor:s

- Dissolved Oxygen SensorsThere are two methods for measuring dissolved oxygen: the optical method and the amperometry method. The optical method is the more commonly used method [30].

- pH SensorsThe pH value is determined via a pH-sensitive electrode [34]. The activity of hydrogen ions in the solution generates a tiny current, which can be utilized to determine the pH level in the water.

- Temperature SensorsTemperature sensors perform to a certain extent depending on the voltage across the diode. The resistance of the diode changes in a precise proportion to the change in temperature of the device. When the temperature drops, the resistance decreases, and vice versa for the same reason.

The list showed in Table 2 are the components needed on the end of the data displaying station, which included a Citrix IBM AMD Opteron (tm) Processor 6172 × 24 cores, a RAID10/300 GB/SAS * 4 HDD, and 40 GB RAM. In terms of the software, the operating system used Ubuntu 14.04 LTS 64 bit, ELK (Elasticsearch, Logstash, and Kibana), Grafana, Java, and Open Street Map to build up the system.

Table 2.

System Service Equipment.

We refer to [24] to set up six monitoring stations on campus; the locations are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The locations of monitoring stations.

3.2. System Architecture

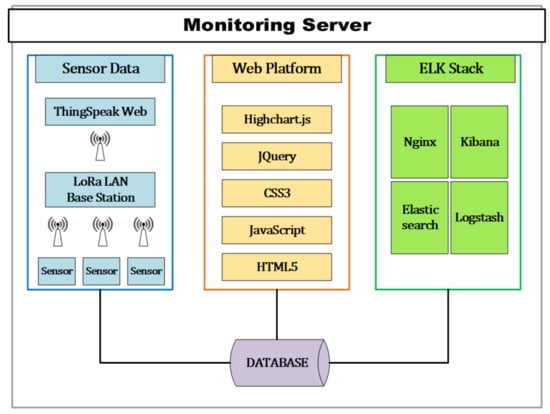

The overall structure is shown in Figure 2. For the issue of health hazards [35], the air quality data are logged and monitored. Moreover, the outdoor monitoring stations are charged by solar cells. There are three parts of monitoring servers in our system: the sensor data, the web platform, and the ELK Stack.

Figure 2.

System architecture.

3.3. Real-Time Data Collection Service

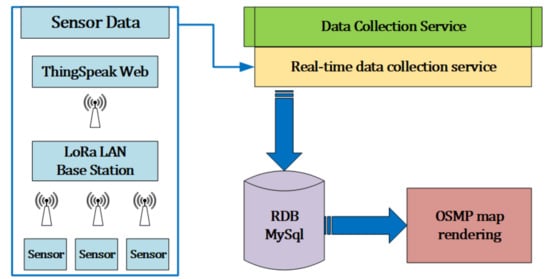

Real-time data are important for the assessment of campus air quality, as shown in Figure 3. We use Java programs to capture these real-time data from the monitoring sensors and then store the data in the MySQL database by the Open street map and ELK Stack [36,37,38].

Figure 3.

Data Collection Service.

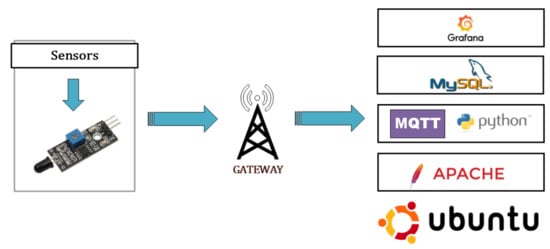

3.4. Web Monitoring System

The architecture of the web monitoring system uses the following software: (1) Ubuntu 18.04 as the operating system; (2) Python 3.6 was used for application programming, while MQTT and MYSQL databases were used for data transmission and access in the data communication section of the website; and (3) Grafana 6.2.5 was used to display the data and establish alert standards to notify when specified anomalous instances occurred, as depicted in Figure 4. To create the system, we installed Open Street Map, Java, and ELK (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana).

Figure 4.

System Architecture Diagram.

3.5. Sensor Deployment

3.5.1. Air Quality Sensor and LoRa Terminal Deployment

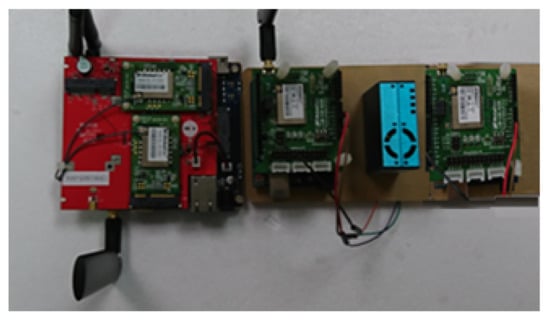

The air quality sensors and LoRa, including the RX64M controller PCB, humidity (PMS5003T) and temperature sensors, solar panel, charge and discharge control board, LoRa module, and Gateway, are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Monitoring Station with LoRa and Gateway.

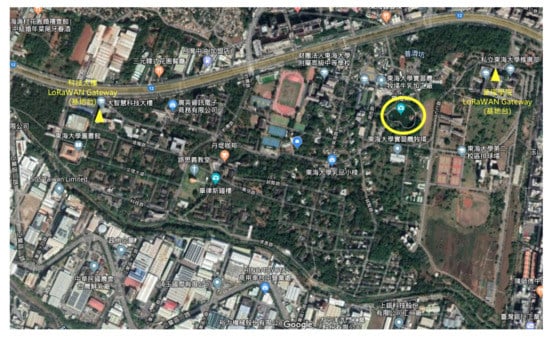

Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the gateway location and LoRa test installation of the deployment station at the campus, respectively.

Figure 6.

LoRa Gateway Installation.

Figure 7.

LoRa Campus Test Chart.

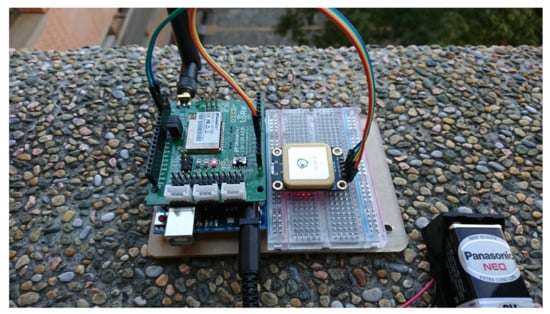

3.5.2. Water Monitoring Sensor and LoRa Deployment

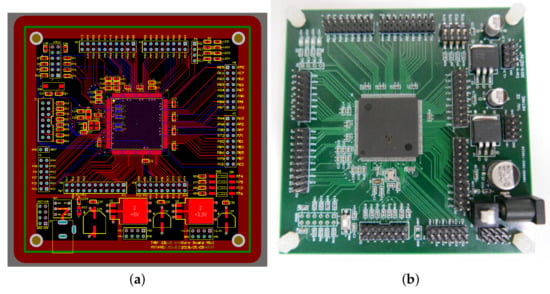

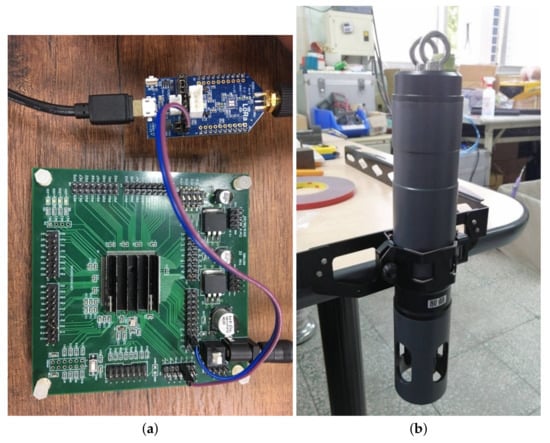

The terminal sensors are integrated and log data by a lab-made PCB board with RENESAS RX64M MCU, using LoRa to transmit the data. The MCU of Renesas RX64M [39] with 170 Pins and 128 I/O Ports is capable of operating at up to 120 MHz and allows for high-speed and low power consumption. The RX64M Group is suitable for network devices, industrial equipment, and other applications that require large-capacity memory, real-time performance, and harsh environments.

According to the development process, we used Renesas chips and constructed and simulated the necessary circuits with ADS (Advanced Design System) software based on the circuit principle. After several integrated tests of interface matching, we achieved success, and then used Altium Designer (PCB Design Software) to draw the PCB Layout diagram shown in Figure 8a. We then constructed it as a real system as shown in Figure 8b and Figure 9a.

Figure 8.

PCB model: (a) The PCB Layout Figure of repaid rapid monitoring station; (b) Complete diagram of all-component welding.

Figure 9.

LoRa and Water Multi-sensor: (a) The total connection diagram of with LoRa module of EK-S76SXB; (b) Multi-parameter Water Quality Sensor.

Modbus [40] is widely used in industrial settings because it is simple to implement and maintain compared to other standards and has minimal constraints. Modbus allows several devices to be connected to the same cable to communicate with each other. A gadget that measures temperature and another that monitors humidity, for example, might be linked to the same cable and transmit measurements to the same computer, just like the water sensor we employed in this paper, as shown in Figure 9b.

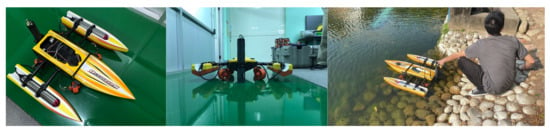

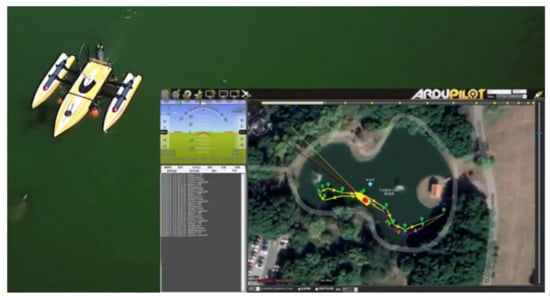

This system collects four parameters: pH, DO Conductivity, and Temperature. The data are broadcast to the network using MQTT. The message is then captured by the MQTT client and saved to the database. We used a mini ship to collect the water parameters from the lake. Figure 10 illustrates the mini ship used in our experiments.

Figure 10.

Mini ship tool.

The data were transmitted with LoRa and broadcasted using an MQTT gateway, as shown in Figure 11. In comparison to the Wi-Fi transmission system, the cost is much lower [41]. Furthermore, the stable remote transmission prevents data loss and allows for more reliable recording and analysis of the data collected. As a result, LoRa is the transmission technology of choice for the majority of people.

Figure 11.

Water Quality Data Collection.

3.6. Packet Loss Rate Transmission

(1) Transmission Packet Loss Rate: For real-time flows, the PLR is a key performance indicator. The number of packets lost or deleted during transmission must be kept low because these data flows are promised certain data speeds for smooth and flawless transmission. The PLR can be calculated as follows in a transmission interval:

where and represent the total number of packets sent and received, respectively. In LTE-Sim, it could be accomplished quickly by collecting all of the real-time packet sizes that are transmitted and received, then calculating the PLR using one of the evaluation tools available in the simulator. We compared two parameters, which are the central frequency and the amount of data sent, based on the same distance between the gateway and the logging points. There are two key points need to emphasize to optimize PLR. The first one is to increase the numbers of gateway or 3 dBi antenna would be actually reduced the PLR. The second one is to reduce the packet size.

Radio frequency (RF) test equipment is frequently prohibitively expensive, and test engineers may lack RF knowledge. This leads to a lack of verification of the RF performance in a device. As a result, devices end up exhibiting poor range characteristics that are not circumvent able as the issue lies in the underlying design. In order to verify the receiving ability, a LoRa’s receiving testing was conducted. The hardware includes the following: (1) a LoRa® Evaluation Board LM-130H1 AEB, which is a built-in switchable protocol (LoRaWAN™/M.O.S.T.) device based on the GlobalSat LM-130H1 module, and (2) a dual channel professional LoRa Gateway (LG-S201H EVB), which can operate independently, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

The Equipment of Packet Loss Rate Test.

4. Experimental Results

This paper introduces the experimental results of the LoRa low-power network of a monitoring system, which is used for monitoring Tunghai University campus’s air and lake water. In this section, the system design architecture is described. Section 4.2 lists the aeronautical data collection services and real-time processing services and data analysis services. Section 4.3 is the presentation of ELK historical data, and the performance evaluation and results presented in the Section 4.4.

4.1. IDW Visualization

The logging data are transmitted, after processing, by LoRa and uploaded to the ThingSpeak website per minute. Our real-time display system uses the OSM map (Open Street Map). It can display a variety of information, as shown in Figure 13a. Figure 13b presents the IDW map values after IDW calculation. It merges into the DataFrame of the map’s grid layer and gives the corresponding density color according to the sensor value of each grid. The color rendering refers to the sensor’s values classification from the source data. Because it is difficult to see the concentration diffusion using StepColorMap, this study uses LinearColorMap with gradient effect to better present the concentration diffusion. Finally, we use the Folium framework to create a Leaflet map and overlay the grid layer files of the map to complete drawing the grid’s map.

Figure 13.

LoRa Map and IDW coverage: (a) The location map of monitoring stations; (b) IDW map implementation.

4.2. Historical Data ELK Stack Results

In addition to the real-time map, the data display system provides historical information of PM2.5, temperature, and humidity in recent hours, for analysis, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Hourly time axis to observe the variation in logging data.

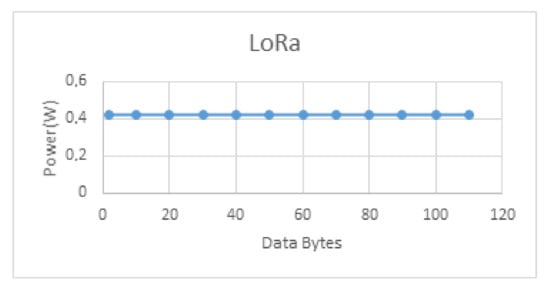

4.3. Energy Consumption Comparison with WiFi Data Transmission

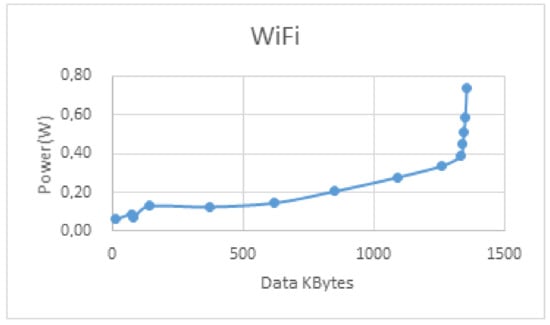

In order to understand the energy consumption when using LoRa module (EK-S76SXB) to transmit data, we conducted the other experiment with a WiFi transmission module for comparison. Except for the different of transmission method, the water sensor and RX64M controller PCB did not change. There is one more thing should be mentioned: the energy consumption comparisons are conducted away from the web-sever of collecting data (a) under a 1.7 km distance with the LoRa module and (b) under a 15 m distance with a WiFi module. It is clearly shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16. Long-distance transmission is indeed LoRa’s advantage. Regardless of the amount of data (as long as it is within the capabilities of LoRa), the energy consumption of LoRa is constant, but the WiFi is not. Moreover, there is no delay phenomenon in the transmission at a distance of 1.5 km.

Figure 15.

The energy consumption comparison charts with the LoRa module under a 1.7 km distance.

Figure 16.

The energy consumption comparison charts with a WiFi module under a 15 m distance.

4.4. Gateway Receiving Sensitivity

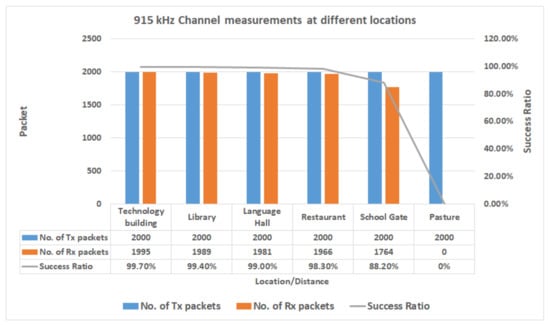

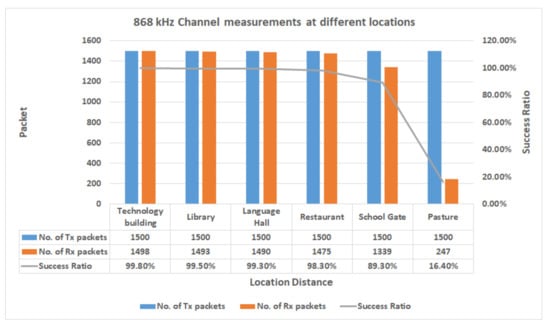

Because there are numerous models and evaluations of radio signal propagation at the frequencies utilized by LoRa in diverse situations, this testing focuses on the decoding performance of LoRa receivers. As shown in Figure 17 and Figure 18, they sent two different types of packets to the gateway, 1500 and 2000, which were then recorded as Received Signal Strength Indicators (RSSI) of received packets from a LoRa device (logging points). All packets were transmitted with a bandwidth of 125 kHz and a coding rate of 4 out of 5 using this configuration.

Figure 17.

Receiver sensitivity data collection in the 915 kHz Channel.

Figure 18.

Receiver sensitivity data collection in the 868 kHz band.

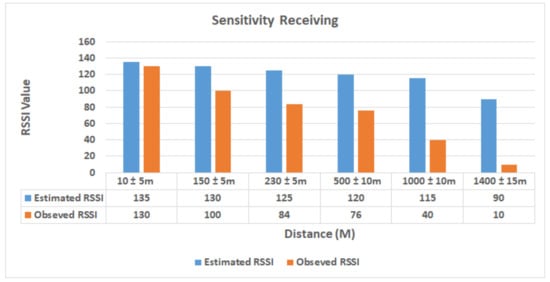

For minimizing the distance covered before reaching low RSSIs, the device’s broadcast power was set to the minimum (2 dBm, with a 3-dBi antenna). The distance between the logging stations and gateway when packets started to be dropped was in the order of 1400 m. Figure 19 illustrates the actual results of sensitivity receiving.

Figure 19.

The Actual Results of Sensitivity Receiving.

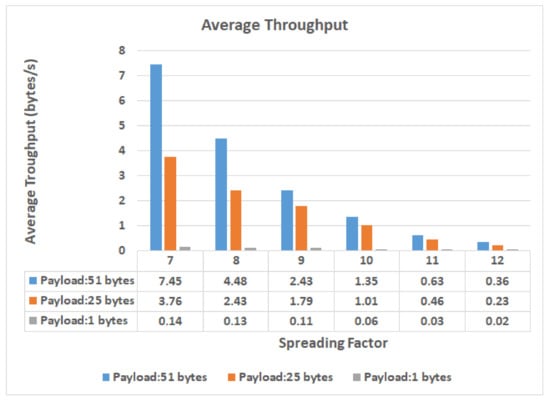

4.5. Single-Device Maximum Throughput

Throughput is defined as the rate at which a successful message is delivered through a communication channel. It is commonly measured in bits per second (bit/s or bps), data packets per second (p/s or pps), or data packets per time slot (data packets per time slot). The throughput of a communication system can be affected by a variety of factors, including the limitations of the underlying analog physical medium, the available computing capacity of system components, and end-user behavior. In the case of WiFi, the ISP and devices upstream of the APs limit the amount of data that may be sent to the Internet. Furthermore, because 802.11 is a shared medium, it is constrained by other wireless devices. The testing here in this paper was to assess the maximum throughput of a single device can be achieved in a RoLa module (just focus on analog physical medium). It is obviously shown in Figure 20 that the results depend on the payload size being sent. Consistent experimental results were found with [39] as well as the same result description.

Figure 20.

Average Throughput.

4.6. Discussion

From the results, we can summarize that the largest information rate (in units of information per unit time) that can be obtained with arbitrarily tiny error probability is defined as the channel capacity. That is the tight upper bound on the rate at which information may be successfully sent across a communication channel. The greatest mutual information between the channel’s input and output determines the channel’s capacity, where the maximization is with respect to the input distribution.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

This paper deploys real-time air and water quality monitoring using the LoRa network. LoRa has many benefits: low power consumption, energy-saving, and long-distance transmission characteristics. In addition, we have made its sensors modularized for quick deployment and low maintenance costs. It was necessary to use Grafana to clearly show the trend of the data from various sources and demonstrate the benefits of this system in these specific fields. For air or water monitoring, the terminal sensors are integrated and logged data by a lab-made PCB board with RENESAS RX64M MCU and LoRa to transmit data. In order to evaluate this campus LORA monitoring system, we also collected public information provided by the environmental protection department of the Taiwan government at the same monitoring point for comparison. Moreover, another effort in this paper is to extend the sensor to dissolved oxygen, pH, and temperature sensors and use the monitoring system to monitor the water quality of Tunghai Lake. In this case, this work showed the characteristics of LoRa energy-saving and long-distance transmission advantage. In addition, we also discussed receive performance, packet loss rate, gateway receiving sensitivity, single device maximum throughput, total capacity, and the channel load of LoRa. Furthermore, data from multiple sensors may be used to train the learning model in the future, and deep learning can be incorporated to further assess and predict water quality. These data will be used to assist in improving the river and water quality. According to the confidence in the experimental data, the LoRa monitoring architecture of this paper can be extended to others in the wide range of areas for applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-T.Y. and H.-Y.M.; methodology, H.F.; software, Y.-S.L. and C.-Y.C.; validation, C.-T.Y. and H.-Y.M.; formal analysis, E.K.; data curation, H.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K., Y.-S.L. and C.-Y.C.; writing—review and editing, C.-T.Y. and H.-Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), Taiwan (R.O.C.), under grants number 110-2622-E-029-012-, 110-2621-M-029-003-, 110-2811-E-029-003-, and 110-2221-E-029-020-MY3.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

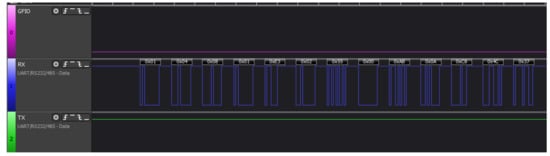

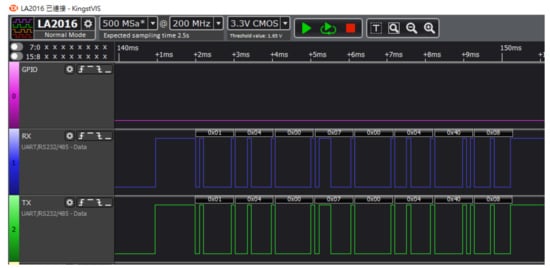

Appendix A. Tests between Rx64M and Sensors

We could obtain pH, Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Conductivity (COND), Temperature (Temp) 4 logging data from water quality sensor in 1 command, synchronously, as shown in Figure A1 and Figure A2. Figure A1 showed the blue line as the command wave form from RX64M to sensor, and the correct evidence obtain from the green wave in the bottom of the Figure A1, which were sent through the TX port of RX64M and are out-and-out the same with the blue one. Then, Water Sensor’s responses as shown in Figure A2, and they conform to the format in the manual of sensor, fully, as shown in Table A1 and Table A2 For now, the function between the RX64M and the water sensor are correct.

Figure A1.

Tests of command sending from Sensor to RX64M.

Figure A2.

Tests of command sending from RX64M to Sensor.

Table A1.

The requirements format sending from Host (RX64M).

Table A1.

The requirements format sending from Host (RX64M).

| Address | Coding | Register High Bit (8 bit) | Register Low Bit (8 bit) | Number of Registered High Bit (8 bit) | Number of Registered Low Bit (8 bit) | CRC High Bit | CRC Low Bit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x01 | 0x04 | 0x00 | 0x07 | 0x00 | 0x05 | 0x81 | 0xC8 |

Table A2.

The data format sending from Water quality Sensor (CWQ-Y4000).

Table A2.

The data format sending from Water quality Sensor (CWQ-Y4000).

| Name | High Byte | Low Byte | Complete Value | Actual Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 0x01 | 0xE4 | 484 | 4.8 |

| DO | 0x02 | 0x4D | 589 | 5.89 |

| COND | 0x00 | 0xAF | 175 | 0.175 |

| Temp | 0x0A | 0x3A | 2618 | 26.18 |

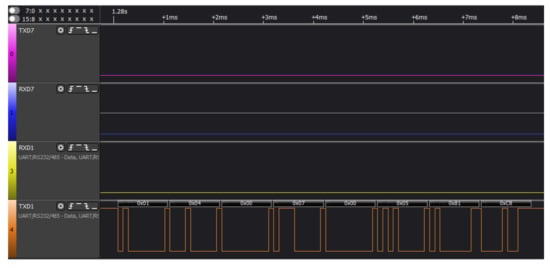

Appendix B. Tests between Rx64M and the LoRa Module of EK-S76SXB

We develop the firmware of RX64M for the function of sending data, which logs from water sensor data using the LoRa Module. The response format is shown in Figure A3 as a signal diagram, which is according to the command format of RX64M in Table A3 and is out-and-out the same format of Table A4 of the RoLa module. That is to say, the function between the RX64M and the RoLa module are correct.

Figure A3.

UART Communication(Read Data!) from RoLa module to Host (RX64M).

Table A3.

The requirements format sending from Host (RX64M) to RoLa module.

Table A3.

The requirements format sending from Host (RX64M) to RoLa module.

| Address | Coding (8 bit) | Register High Bit (8 bit) | Register Low Bit (8 bit) | Number of Registered High Bits (8 bit) | Number of Registered Low Bits (8 bit) | CRC High Bit | CRC Low Bit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x01 | 0x06 | 0x00 | 0x02 | 0x00 | 0x05 | 0x29 | 0xCC |

Table A4.

The responses format sending from RoLa module to Host (RX64M).

Table A4.

The responses format sending from RoLa module to Host (RX64M).

| Address | Coding (8 bit) | Register High Bit (8 bit) | Register Low Bit (8 bit) | Number of Registered High Bits (8 bit) | Number of Registered Low Bits (8 bit) | CRC High Bit | CRC Low Bit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x01 | 0x04 | 0x00 | 0x07 | 0x00 | 0x05 | 0x81 | 0xC8 |

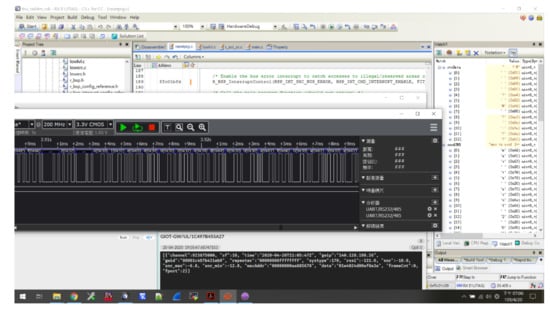

Appendix C. Tests between Water Sensor, Rx64M and LoRa Module of EK-S76SXB

Based on the correct results from (2) and (3). It should to test the combination of logging and sending command, wait and see the signal flow of RX64M, and echo responses from the RoLa module. It should be noted that the results showing of Figure A4. However, with the correct flow control (within the range of accepted by the compiler), the difference is not significant. According to Figure A4, under the arrangement of execution order of RX64M firmware, the logging data from water sensor (the upper right of Figure A4) appear sequentially at the front of the data stack and then are passed to the LoRa module, the evidence is shown the middle of Figure A4. Finally, we obtained a “correct” response from LoRa module, as showed in the bottom of Figure 20. That is to say, the total function between the Water sensor, Rx64M, and LoRa Module are correct.

Figure A4.

The total responses diagram of Water sensor, RX64M and RoLa module.

References

- Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhan, D.; Li, J. The impact of anthropogenic emissions and meteorological conditions on the spatial variation of ambient SO2 concentrations: A panel study of 113 Chinese cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristiani, E.; Kuo, T.Y.; Yang, C.T.; Pai, K.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Nguyen, K.L.P. PM2.5 Forecasting Model Using a Combination of Deep Learning and Statistical Feature Selection. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 68573–68582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiani, E.; Chen, Y.A.; Yang, C.T.; Huang, C.Y.; Tsan, Y.T.; Chan, W.C. Using deep ensemble for influenza-like illness consultation rate prediction. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 117, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.T.; Chen, H.W.; Chang, E.J.; Kristiani, E.; Nguyen, K.L.P.; Chang, J.S. Current Advances and Future Challenges of AIoT Applications in Particulate Matters (PM) Monitoring and Control. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 126442, 126442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, T.; Reyes, C.; Upadhyay, H.; Sharma, S.C.; Lagos, L. Cloudlet-enabled wireless body area networks (WBANs): A systematic review, architecture, and research directions for QoS improvement. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, T.; Sharma, S.C. An autonomic resource provisioning framework for efficient data collection in cloudlet-enabled wireless body area networks: A fuzzy-based proactive approach. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 10361–10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance, L. LoRaWAN Coverage. Available online: https://lora-alliance.org/lorawan-coverage/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Augustin, A.; Yi, J.; Clausen, T.; Townsley, W.M. A Study of LoRa: Long Range & Low Power Networks for the Internet of Things. Sensors 2016, 16, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiani, E.; Yang, C.T.; Huang, C.Y.; Ko, P.C.; Fathoni, H. On Construction of Sensors, Edge, and Cloud (iSEC) Framework for Smart System Integration and Applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov, K.; Petaejaejaervi, J.; Haenninen, T. Analysis of capacity and scalability of the LoRa low power wide area network technology. In Proceedings of the European Wireless 2016, 22th European Wireless Conference, Oulu, Finland, 18–20 May 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, D.; Peralta, G.; Manero, L.; Gomez, R.; Bilbao, J.; Zubia, C. Energy and coverage study of LPWAN schemes for Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Workshop of Electronics, Control, Measurement, Signals and Their Application to Mechatronics (ECMSM), Donostia, Spain, 24–26 May 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Petrić, T.; Goessens, M.; Nuaymi, L.; Toutain, L.; Pelov, A. Measurements, performance and analysis of LoRa FABIAN, a real-world implementation of LPWAN. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 27th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor, and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC), Valencia, Spain, 4–8 September 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, K.; Zhao, S.; Yang, Z.; Xiong, X.; Xiang, W. Design and implementation of LPWA-based air quality monitoring system. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 3238–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokul, V.; Tadepalli, S. Implementation of a WiFi based plug and sense device for dedicated air pollution monitoring using IoT. In Proceedings of the 2016 Online International Conference on Green Engineering and Technologies (IC-GET), Coimbatore, India, 19 November 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Lim, J.Y.; Kim, J.D. Low-power, long-range, high-data transmission using Wi-Fi and LoRa. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th International Conference on IT Convergence and Security (ICITCS), Prague, Czech Republic, 26–29 September 2016; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, K.H.; Liang, Q.W.; Zeng, G.J.; Lin, J.H.; Lee, H.C. Demo abstract: A LoRa wireless mesh networking module for campus-scale monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2017 16th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 18–21 April 2017; pp. 259–260. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, P.; Montavont, J.; Noel, T. Indoor deployment of low-power wide area networks (LPWAN): A LoRaWAN case study. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 12th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob), New York, NY, USA, 17–19 October 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, G.S.; Yang, F.; Lawrence, P.; Michiels, S.; Joosen, W.; Hughes, D. μPnP-WAN: Experiences with LoRa and its deployment in DR Congo. In Proceedings of the 2017 9th International Conference on Communication Systems and Networks (COMSNETS), Bengaluru, India, 4–8 January 2017; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Werme, M.; Eriksson, T.; Righard, T. Maintenance concept optimization—A new approach to LORA. In Proceedings of the 2017 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Orlando, FL, USA, 23–26 January 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gregora, L.; Vojtech, L.; Neruda, M. Indoor signal propagation of LoRa technology. In Proceedings of the 2016 17th International Conference on Mechatronics–Mechatronika (ME), Prague, Czech Republic, 7–9 December 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bonetto, R.; Bui, N.; Lakkundi, V.; Olivereau, A.; Serbanati, A.; Rossi, M. Secure communication for smart IoT objects: Protocol stacks, use cases and practical examples. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–28 June 2012; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bressan, N.; Bazzaco, L.; Bui, N.; Casari, P.; Vangelista, L.; Zorzi, M. The deployment of a smart monitoring system using wireless sensor and actuator networks. In Proceedings of the 2010 First IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 4–6 October 2010; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Petäjäjärvi, J.; Mikhaylov, K.; Hämäläinen, M.; Iinatti, J. Evaluation of LoRa LPWAN technology for remote health and wellbeing monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th International Symposium on Medical Information and Communication Technology (ISMICT), Worcester, MA, USA, 20–23 March 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Bui, N.; Castellani, A.; Vangelista, L.; Zorzi, M. Internet of Things for Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, M.; Vejlgaard, B.; Kovács, I.Z.; Nguyen, H.; Mogensen, P. Interference measurements in the European 868 MHz ISM band with focus on LoRa and SigFox. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 19–22 March 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, T.; Sharma, S.C. Cloud-WBAN: An experimental framework for cloud-enabled wireless body area network with efficient virtual resource utilization. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2018, 20, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, T.; Sharma, S.C. Fuzzy logic-based elasticity controller for autonomic resource provisioning in parallel scientific applications: A cloud computing perspective. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 70, 1049–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukta, M.; Islam, S.; Barman, S.D.; Reza, A.W.; Khan, M.S.H. Iot based Smart Water Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS), Singapore, 23–25 February 2019; pp. 669–673. [Google Scholar]

- Simitha, K.; Raj, S. IoT and WSN based water quality monitoring system. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, India, 12–14 June 2019; pp. 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Lugo, A.G.; McLernon, D.C.; Lara, M.; Zaidi, S.A.R.; González, B.J.; Illescas, O.; Pérez-Macías, C.I.; Nájera-Bello, V.; Balderas, J.A.; Pizano-Escalante, J.L.; et al. Monitoring of water quality in a shrimp farm using a FANET. Internet Things 2020, 18, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwani, P.; Perez-Pons, A.; Bhardwaj, T.; Upadhyay, H.; Joshi, S.; Lagos, L. Securing Environmental IoT Data Using Masked Authentication Messaging Protocol in a DAG-Based Blockchain: IOTA Tangle. Future Internet 2021, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yoon, D.; Ghosh, A. Intelligent parking lot application using wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Symposium on Collaborative Technologies and Systems, Irvine, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2008; pp. 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffers, H.; Komninos, N.; Pallot, M.; Trousse, B.; Nilsson, M.; Oliveira, A. Smart cities and the future internet: Towards cooperation frameworks for open innovation. In Future Internet Assembly; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- Sumaray, A.; Makki, S.K. A comparison of data serialization formats for optimal efficiency on a mobile platform. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication, Seoul, Korea, 3–5 January 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pitarma, R.; Marques, G.; Ferreira, B.R. Monitoring Indoor Air Quality for Enhanced Occupational Health. J. Med. Syst. 2017, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.T.; Chen, S.T.; Liu, J.C.; Sun, P.L.; Yen, N.Y. On construction of the air pollution monitoring service with a hybrid database converter. Soft Comput. 2019, 24, 7955–7975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.T.; Chen, S.T.; Den, W.; Wang, Y.T.; Kristiani, E. Implementation of an intelligent indoor environmental monitoring and management system in cloud. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 96, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.T.; Chen, C.J.; Tsan, Y.T.; Liu, P.Y.; Chan, Y.W.; Chan, W.C. An implementation of real-time air quality and influenza-like illness data storage and processing platform. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 100, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renesas. High Performance 32-bit Microcontrollers Achieving 4.55CoreMark/MHz (546CoreMark) with RXv2 Core Employed. 2020. Available online: https://www.renesas.com/eu/en/products/microcontrollers-microprocessors/rx-32-bit-performance-efficiency-mcus/rx64m-high-performance-32-bit-microcontrollers-achieving-455/coremarkmhz-546coremark-rxv2-core-employed (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Knovel. Control Techniques Drives and Controls Handbook (2nd Edition). 2020. Available online: https://app.knovel.com/web/toc.v/cid:kpCTDCHE08/viewerType:toc/root_slug:control-techniques-drives/url_slug:control-techniques-drives/? (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Klimiashvili, G.; Tapparello, C.; Heinzelman, W. LoRa vs WiFi Ad Hoc: A Performance Analysis and Comparison. In In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Big Island, HI, USA, 17–20 February 2020; pp. 654–660. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).